Abstract

Airway management in patients with faciomaxillary injuries is challenging due to disruption of components of upper airway. The anesthesiologist has to share the airway with the surgeons. Oral and nasal routes for intubation are often not feasible. Most patients have associated nasal fractures, which precludes use of nasal route of intubation. Intermittent intraoperative dental occlusion is needed to check alignment of the fracture fragments, which contraindicates the use of orotracheal intubation. Tracheostomy in such situations is conventional and time-tested; however, it has life-threatening complications, it needs special postoperative care, lengthens hospital stay, and adds to expenses. Retromolar intubation may be an option, But the retromolar space may not be adequate in all adult patients. Submental intubation provides intraoperative airway control, avoids use of oral and nasal route, with minimal complications. Submental intubation allows intraoperative dental occlusion and is an acceptable option, especially when long-term postoperative ventilation is not planned. This technique has minimal complications and has better patients’ and surgeons’ acceptability. There have been several modifications of this technique with an expectation of an improved outcome. The limitations are longer time for preparation, inability to maintain long-term postoperative ventilation and unfamiliarity of the technique itself. The technique is an acceptable alternative to tracheostomy for the good per-operative airway access.

Keywords: Adult, intubation, intratracheal methods, maxillofacial injuries/surgery, oral/methods, surgery

Introduction

Due to prominent anatomical location, maxillofacial injuries and fractures are nearly always associated with moderate-to-severe road traffic accidents (RTA). Mandible and zygomatic arch are commonest sites of fracture.[1] About 21.8% of all the maxillofacial injuries need open reduction and internal fixation.[2] Panfacial or maxillofacial injuries may lead to derangement of the architecture and disruption of different components (soft tissue, bony, and cartilaginous) of the upper airway, often with little external evidence of the deformity. In many such situations, neither oral nor nasal route for intubation is appropriate during the surgical repair. Recent advancements in the discipline of oral and maxillofacial surgery and availability of new techniques and technologies have made rigid fixation with mini and microplate osteosynthesis possible in almost all facial fractures.

Delivery of anesthesia for maxillofacial surgeries is a challenge because the anesthesiologist has to share the upper airway field with the surgeon. Conventional orotracheal intubation is inappropriate as it interferes with the surgical access. Temporary intraoperative occlusion of teeth (intramaxillary and maxillomandibular fixation) is needed to check the alignment of the fracture fragments, making orotracheal intubation unsuitable. Most importantly, presence of altered airway anatomy and airway edema may compromise the airway. Options in airway management in these patients include tracheostomy, nasotracheal intubation, retromolar intubation, and submentotracheal intubation.

Nasotracheal intubation is not recommended in presence of panfacial fracture, cervical spine injury, skull base fracture with or without cerebrospinal fluid rhinorrhea, systemic coagulation disorders, distorted nasal anatomy and when nasal packing is indicated. Fiberoptic-guided nasotracheal intubation, though controversial, can be tried in selected patients.[3] Nasotracheal intubation may be impossible as deformity or fracture of nasal bones, cribriform plate of ethmoid or nasoorbital ethmoid complex are often associated. Efficacy of topical anesthesia over traumatized and inflamed mucosa is uncertain. Moreover, even a small bleed in presence of altered anatomy may lead to complete loss of vision through a fiberscope and may lead to an emergent situation. Potential complications of nasotracheal intubation are mucosal dissection, injury to adenoids, meningitis, sepsis, sinusitis, epistaxis, dislodgement of bony fragments, and obstruction of the tube by the distorted airway anatomy or rarely intracranial intubation. In patients requiring simultaneous nasal or nasoorbital ethmoid reconstruction after the rigid fixation of mandible and/or maxilla, intraoperative switching over of the endotracheal tube (ETT) from nasal to oral route is required which may compromise the surgical field sterility and may increase the possibility of pulmonary aspiration. Possible difficulty in airway management, disruption of surgical repair, and obstruction to the operative field are additional limitations.[4]

Elective short-term tracheostomy is the conventional and time-tested method for airway access in these patients. However, it may be associated with immediate and late complications. The procedure is difficult in obese patients, children, and patients with thyroid swelling.[5] The incidence of immediate complications is 6–8% and they include hemorrhage, surgical emphysema, pneumothorax, pneumomediastinum, and recurrent laryngeal nerve palsy. The incidence of delayed complications is 60% and they include stomal and respiratory tract infections, blockage of the tube, dysphagia, difficulty with decannulation, tracheal stenosis, tracheoesophageal fistula, and suboptimal visible scar.[6] Compared to tracheostomy, submental intubation is associated with lesser postoperative complications and requires minimal postoperative care resulting in shorter duration of hospitalization. This procedure can be carried out even in a set up with limited resources.[7]

In 1983, Bonfils first documented the use of retromolar space for endotracheal intubation. Retromolar space is a space between the back of the last molar and anterior component of ascending ramus of the mandible, where it crosses the alveolar margin. The space may not be identical bilaterally due to the dissimilarities in development of the third molars and either of the side may provide space to rest the ETT.[8] Patients with Le Fort II fracture, having both occlusive change and disruption of nasal architecture, are potential candidates for retromolar intubation. Facial trauma related trismus is not uncommon and even with complete dental occlusion this space can be used for suctioning the oropharynx or repositioning the ETT. Both Bonfils intubating fiberscope and flexible fiberscope have been used through this space in patients with difficult airway such as limited mouth opening, limited neck mobility, or cervical spine injury.[9] Mertinez-Lage et al. reported retromolar route for endotracheal intubation in 39 patients requiring craniofacial and orthognathic surgeries, as a substitute for surgical airways in 1998. With this simple, atraumatic, and rapid technique, intraoperative dental occlusion is possible and monitoring patency of the ETT is also not so difficult. Successful maxillofacial surgeries have been reported in good number of patients using this technique.[10–12] Tooth loss is not infrequent in Le Fort II fractures and this gap can also be utilized to safely harbor the ETT secured on the maxillary side.

The primary requirement for a successful retromolar intubation is availability of adequate space in the retromolar area. The adequacy of retromolar space is judged by putting index finger of patient in the space and instructing him to occlude teeth slowly. After confirmation of adequate dental occlusion preoperatively and successful orotracheal intubation, the ETT is moved to the contralateral maxillary side of the retromolar space or missing tooth space and secured with silk sutures. This space is usually spacious enough to anchor an ETT of 7.0-mm ID in adult males. Suctioning of the oropharynx can be done through the opposite retromolar space. After the surgery, the retromolar intubation is dealt as a conventional orotracheal intubation. Monitoring peak airway pressure is of paramount importance, particularly during temporary dental occlusion. Retromolar intubation, a comparatively less invasive and time-efficient technique, may be an acceptable approach to the patient as it essentially serves the very same purpose of submental intubation. If the space is inadequate, the chance of accidental extubation is more. Retromolar space is usually adequate to accommodate the ETT in children. As a child grows, larger tube size is needed and this space tends to become smaller with age and with eruption of molars. There are large individual variations in the retromolar space in adults especially when the third molars are impacted or completely erupted.[13]

If the retromolar space is not adequate, extraction of the third molar with a semilunar osteotomy in the area was suggested by Mertinez-Lage et al. to create enough space for resting the tube.[14] The creation of retromolar space with an osteotomy was used to take almost 25 min in average.[14] The technique was however more invasive, destructive, and time consuming and thus no longer practiced. Osteotomy-related permanent bone loss, just to create a space for temporary accommodation of an ETT, seems impractical. Retromolar intubation without osteotomy took 4 min 33 s in average from induction to ventilator switch on in 84 patients for retromolar intubation with tooth fixation[11] compared to mean procedural time of 9.9 min in 746 patients for submental intubation.[15] In a series of 15 patients, Malhotra found inadequate retromolar space in 3 patients who subsequently required submental intubation.[16] Kruger et al. evaluated 2857 third molars of patients between 18 and 26 years of age and reported that nearly 42% third molars of maxillary side remained unerupted at 26 years of age and that approximately one-third of fully erupted impacted third molars had been uprooted.[17]

Preoperative submental intubation in craniofacial injuries was first proposed by a Spanish faciomaxillary surgeon, Francisco Hernandez Altemir in 1986.[18] He proposed it as an alternative to short-term elective tracheostomy, where both oral and nasal route for endotracheal intubation were not feasible. This technique is applicable where anatomy is likely to become normal after the surgery and long-term postoperative ventilation or protection of airway is not anticipated. Indications for submental intubation are maxillofacial injuries with associated fractures of nasal bone and skull base[19] or use of temporary intermaxillary fixation in patients where nasotracheal intubation is not possible. The scope of this technique has extended far beyond the realm of faciomaxillary surgeries and it has been successfully used in orthognathic surgeries and elective aesthetic face surgeries as there is minimal distortion of the nasolabial soft tissue. It is also used in surgeries where both nasal and oral passages are used by the surgeons (e.g., repair of postcancrum oris defects [Figure 1],[20] oronasal fistula, selected cleft lip, and palate surgeries). Repair of congenital malformations, skull base surgery, multiple or complex facial osteotomies, transfacial oncologic procedures of the cranial base, and pediculated craniofacial surgeries are current indications for submental intubation.

Figure 1.

Postcancrum oris defect

The contraindications of submental intubation are patients’ refusal, bleeding diathesis, laryngotracheal disruption, infection at the proposed site, gunshot injuries in the maxillofacial region,[21] long-term airway maintenance,[22] tumor ablation in maxillofacial region, and history of keloid formation.

A comparison of different techniques of airway access in complex maxillofacial injury is tabulated as Table 1.

Table 1.

Comparison of different techniques of airway access in complex maxillofacial injury

Anatomical relevance

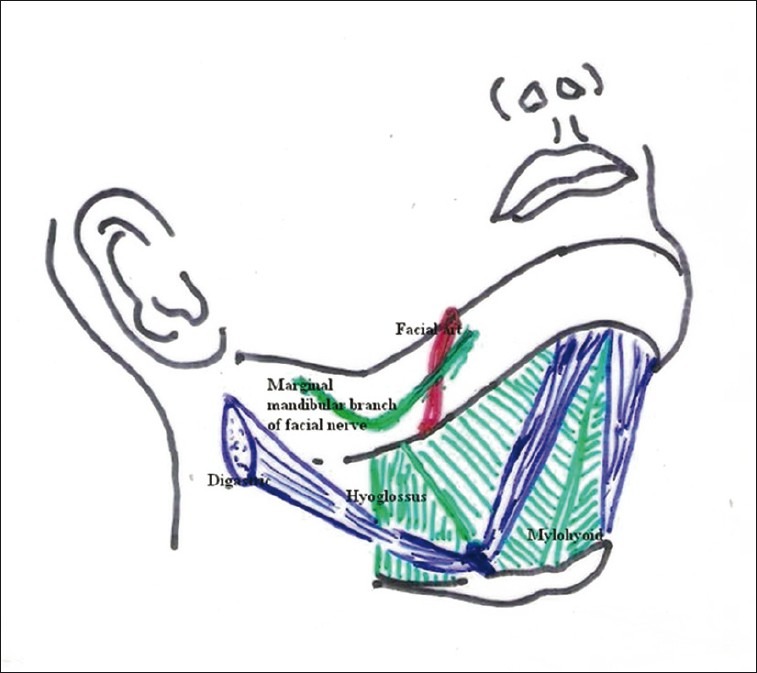

The submental area, situated just below the chin, is demarcated by the anterior bellies of digastric muscles of both sides, chin at the apex, body of the hyoid bone at the base with the mylohyoid muscles flooring it [Figures 2 and 3]. Usually superficial to mylohyoid, it contains a few anatomical structures like lymph nodes and thin vessels.[23]

Figure 2.

Surface anatomy of submental and submandibular region

Figure 3.

Submental and submandibular area after dissection

The submandibular region, just below the body and the ramus of the mandible, is bounded anteroinferiorly by the anterior belly of digastric, posteroinferiorly by the posterior belly of digastric muscles, and superiorly the inferior border of the mandible including the imaginary line projected to the mastoid process, being floored by mylohyoid and hyoglossus. Superficial to mylohyoid and hyoglossus there lie the submandibular gland, hypoglossal nerve, and a few arteries [Figure 4].[23]

Figure 4.

Submental and submandibular area after dissection

Both the routes (anterior-submandibular and posterior-submandibular, depending on the incision chosen) approach the floor of the mouth laterally to hyoglossus, an extrinsic quadrilateral muscle of tongue having origin at hyoid bone and insertion on the sides of the tongue. Laterally, it relates to the lingual nerve with submandibular ganglion coursing downwards and forwards, submandibular gland (deep part) with its duct hooked by the lingual nerve, and the hypoglossal nerve coursing upwards and forwards to supply the tongue.[24] In the posterior part of the submandibular area, not only the lingual and hypoglossal nerves are wide apart but also the submandibular gland exists instead of its duct. In the anterior part, those two nerves get closely approximated in convergence manner with sharing some fibers of hypoglossal and lingual nerve.[24,25]

In the anterior submandibular approach, there is immense chance of facing the two main nerves of tongue and the submandibular duct along with the sublingual gland is in close proximity to one another, which can get damaged unintentionally. If we approach at a posterior plane at the level of third molar (posterior submandibular approach), there is less chance of such damage. Only possible hindrance could be by the submandibular gland itself, which can be easily retracted without any anatomical or functional damage [Figure 5].

Figure 5.

Intubations through anterior part of digastric triangle (right red arrow) may damage the closely approximated lingual nerve, hypoglossal nerve and sublingual duct, whereas in the retromolar space (left red arrow) there are lesser chances of damaging them as they are far apart.

The submental intubation

The conventional submental intubation technique essentially involves creation of an orocutaneous tunnel and diverting the proximal end of the armoured ETT through anterior floor of the mouth.

Appropriate broad spectrum antibiotic, preferably amoxicillin and clavulanic acid, is given intravenously 1 h prior to the procedure. In patients allergic to penicillin, usually first-generation cephalosporin is prescribed. Antisialogogue and aspiration prophylaxis should be considered. Tight seal of the appropriate-sized flexometallic ETTs is made easily detachable from the universal connector. Measures to tackle any emergent situation (e.g., cricothyrotomy and transtracheal jet ventilation) are kept ready, especially for those patients who cannot withstand brief period of cessation of ventilation. There are certain modifications of the classic technique that allow ventilation during tube transfer. Refinements such as double tube method or airway exchanger technique reduce the time between detachment of the circuit and reattachment. General anesthesia and orotracheal intubation with appropriate-sized armoured ETT are done in conventional way. Area around proposed site of incision is prepped with 10% povidone iodine solution and is draped with sterile dressings. After local infiltration of skin and soft tissue of the proposed site with 2% lignocaine with adrenaline, a skin incision is made in the right submental region parallel to the inferior border of the corresponding mandible [Figure 6].

Figure 6.

Incision made in the midline in submental region

Approximately 1.5 cm incision is good enough for easy passage of ETT up to 7.5 mm size and 2 cm incision is required for ETT of larger diameter. Right-sided incision is always advantageous as it permits better visualization of the intraoral part of the ETT by left handed laryngoscopy. However, selection of the side is usually done so as to avoid the site of injury and mandibular fracture. Blunt dissection is carried out with a medium-sized curved artery forceps or Kelly clamp along the lingual surface of the mandible through subcutaneous tissue, platysma, investing layer of deep cervical fascia, mylohyoid muscle in between the two heads of digastrics muscles to sublingual mucosa [Figure 7].

Figure 7.

Blunt dissection using artery forceps

A paramedian oral incision is made over the tented mucosa created by the tip of the artery forceps. Tongue is retracted on the other side for better visualization. Adequate exposure of the oral cavity is maintained with a gag. The tunnel created is widened by separating two blades of the artery forceps. Use of two artery forceps facilitates exposure better than a single one. The patient is ventilated with 100% oxygen and 1% isoflurane for 5 min, before replacing the tube through the incision, to tolerate the period of ventilatory pause. After denitrogenation, breathing circuit is disconnected and universal connector is detached from the tube. The tip of the pilot balloon cuff is pulled through the submental incision first [Figure 8].

Figure 8.

Pilot balloon exteriorized through the orocutaneous tunnel

Then the tip of the artery forceps is again introduced through the incision to take out the distal end of the ETT in similar fashion and the ETT is placed in the sulcus between the tongue and the mandible in the floor of the mouth. While pulling, the intraoral part of the flexometallic ETT is kept steady with a Magill's forceps or the index finger of an assistant. The connector is reattached and the ETT reconnected with the breathing circuit. The position of the tube is confirmed by direct laryngoscopy, chest auscultation, and capnography. The skin exit point of the ETT is marked with permanent ink. The ETT is secured to the skin using stay suture with 2-0 heavy silk. Additional fixation by placing a tie suture between the ETT and the universal connector can be applied for further safety. Transparent adhesive dressing is applied over the skin to avoid displacement while manipulating the mandible as well as to visualize the ink mark [Figures 9 and 10].

Figure 9.

Endotracheal tube rerouted through submental space and fixed to the skin

Figure 10.

Transparent dressing applied to observe tube dislodgement

A throat pack is applied if necessary. Capnography has specific importance for alerting the anesthesiologist about tube compression, accidental extubation, or endobronchial intubation with jaw movement during surgery. Airway pressure is monitored peroperatively to detect inadvertent tube compression or deviation. If regular tube is used, assisted manual ventilation during surgery can pick up early evidence of tube compression or kinking. At the end of the surgery, the stay sutures are removed, followed by throat pack. Tracheal extubation is done in the operation theatre or in the postoperative recovery room through the submental route, when the standard criteria of extubation are fulfilled and patient is awake and maintaining airway reflexes. Guedel's airway may be used in cases of submental extubation. As airway and soft-tissue edema can compromise airway in the immediate postoperative period, all patients should be dealt as difficult extubation cases. In situation when there is need for long-term airway maintenance or ventilatory support, the submentotracheal intubation is converted back to orotracheal intubation by pulling the proximal end of the ETT and pilot balloon through the incision. After local infiltration of the wound with 2% lignocaine and adrenaline, the platysma is closed with an absorbable suture and skin closed with monofilament suture. The skin suture applied should be not too tight to allow drainage of tissue fluid. The mucosal wound is left to heal by secondary intention. During the postoperative period, good hydration status is maintained which is of paramount importance regarding wound healing. Care of the intraoral wound is done by maintenance of oral hygiene using 0.12 % chlorhexidine mouth wash six hourly. The broad spectrum antibiotics are continued postoperatively.[26] In case of wound infection or suppuration, cutting one or two stitches usually resolves the complication. Skin stitches are removed after 5–7 days. As some of the complications of the submental intubation may appear late, the patients are followed up till discharge, and after 1, 3, and 6 months postoperatively.

Modifications over the last 25 years

Since first-published report of Altemir, several modifications of submental/submandibular endotracheal intubation have been tried with an expectation of improved outcome. All modifications of submentotracheal intubations are essentially transmylohyoid. Gadre and Waknis[27] considered transmylohyoid as more appropriate terminology, as in this technique the ETT can pass through the mylohyoid muscle anywhere between the first mandibular molars of either side anterior to the massetor muscle, instead of limiting to the submental triangle. In patients with compound comminuted fracture of symphysis and parasymphysis, the conventional submental technique may result in significant stripping of lingual periosteum that can jeopardize blood supply. Most authors are of the opinion that subperiosteal tube placement, as proposed by Altemir in his first report, is not essential.[14,28] The placement of ETT in the anterior part of the submandibular region and “submento-submandibular” intubation seem more appropriate nomenclatures.[29] In strict midline approach, (both mylohyoid muscles meet in the midline in an avascular plane) the chance of bleeding is less.[30] Moreover, transfer of ETT is easier as structures are less cramped. Use of two ETT (one anterograde and the other retrograde) is claimed to be superior because there is less chance of hypoxia if there is difficulty in retrieval and no need of detaching the connector.[28] After conventional orotracheal intubation with a regular ETT, another reinforced ETT is introduced through the submental incision from exterior to the oral cavity and negotiated in the oropharynx with a McGill forceps. The regular orotracheal tube is then exchanged with the submentally introduced armoured tube. This idea is supported by other authors as well.[31,32] Hanamoto et al. used sterile polypropylene cylinder of 10-ml syringe, through the submental incision into the oral cavity. The distal end of the orotracheal tube was connected with the proximal end of the second tube passed through the submental tunnel. Ventilation was possible during re-routing the orotracheal tube through the submental path.[33]

One serious drawback of retrograde technique is that it may result in introduction of infection to lower airways. Risk of sepsis can be due to the contaminated pilot balloon passing through the incision wound during extubation. Cutting the end of the ETT and replacement with another universal connector has also been advocated.[21] Conversion of the orotracheal to submento-tracheal intubation can be done faster with use of a tube exchanger.[34] Drolet et al. suggested the use of a tube exchanger to exchange a damaged ETT through the submental route. It facilitates exchanging the tube without loss of airway in difficult airway situations even with a steeper angle than oral or nasal route. During the procedure the patient can be ventilated through the port into the airway exchanger minimizing the chances of desaturation. Injury to the pilot balloon while retrieving through the tunnel can be averted by inserting the deflated pilot balloon into the ETT.[27] The ETT is further cleared of any blood or secretion after it is taken out.

“Rule of 2-2-2” – 2 cm long incision, 2 cm away from the midline, 2 cm medial and parallel to the mandibular margin has been suggested by Nyarady et al.[35] Nylon guiding tube for exteriorizing the ETT has less chance of injury to the associated structures.[35] Dilators of percutaneous dilatation sets can be used to create mucocutaneous fistula as an alternative to blunt dissection and are claimed to produce minimal scar and minimal bleeding.[36] A 100% silicon wire reinforced tube primarily intended for intubation through intubating laryngeal mask airway (ILMA) is a better option as it has an easily removable universal connector.[37] A 1.5-cm skin incision, 1 in. below and 0.5 in. anterior to the angle of the mandible is found to be more advantageous as posterior placement of the tube assures unobstructed surgical field.[4]

Mahmood and Lello[38] performed submental intubation using preformed Sheridan tube. The preformed curvature helps in positioning of the tube as it conforms to the anatomy of the region. Lima et al.[39] in their study utilized surgical glove finger to cover the proximal end of the ETT, which helped in preventing the entry of blood and soft tissue during its passage through orocutaneous tunnel. Similarly, Adeyemo et al.[40] used nylon tube sac to cover the open end of the tube during transfer through the tunnel. The submental route has also been used for the LMA with reinforced tube in specific situations such as laryngotracheal disruption, voice professionals refusing endotracheal intubation, and patients with unstable cervical fractures posted for faciomaxillary surgery. However, movement of patient's head should be very gentle and great care is needed to prevent dislodgement of the LMA.[41]

The use of Combitube SA (Tyco-Kendall, Mansfield, MA) through the wide submental incision or the external injury site makes provision for adequate dental occlusion, unimpeded surgical access, and ease of ventilation in severe maxillofacial injuries. Moreover, the inflated proximal balloon helps to allay pain and minimizes bleeding by spontaneous reduction of fracture fragments.[42]

There are risks of accidental extubation and increased chance of aspiration. These problems are more in the pediatric population. Bleeding from the incision site usually responds to pressure. Compression and deviation of the tube result in increased airway pressure during surgical maneuver. There is difficulty in passing the tube through submental incision[43] and chance of hypoxia if retrieval of tube and reestablishing connection is delayed. There is intraoperative difficulty in passing nasogastric tube.[19] There are incidences of superficial infection, abscess, sepsis, damage to the lingual nerve, hypertrophic scar, orocutaneous fistula, and mucocele.[44] Superficial infection of the submental incision site is documented as the most common complication, whereas airway compromise is stated to be most important potential complication. Fortunately, most of the reported superficial infections responded to local measures and minimal intervention like partial removal of stitches.[45] Trauma to submandibular and sublingual gland and ducts and salivary fistula have also been described.[18,46,47] Suctioning is difficult through the tube and can be done after extension of the neck with well-lubricated suction catheter. The postoperative period may be complicated by airway edema, obstruction, hematoma, and reexploration. Yoon et al.[48] reported of accidental detachment of a deflated pilot balloon while manipulating the balloon during converting the submental intubation back to orotracheal. It was managed by cutting a pilot balloon from a new ETT and by connecting it to the first tube by a 20G needle connector. Submento-tracheal intubation is generally better tolerated by the awake patient than orotracheal intubation [Figure 11]. Chance of biting the ETT by the patient with disruption of the surgical repair is always a threat in oral extubation.[4]

Figure 11.

Awake patient tolerating the tube well (permission obtained from the patient)

Though adequate mouth opening is an essential part of conventional submental intubation, successful retrograde submental intubation (combination of retrograde intubation and submental intubation) is also reported in a patient with faciomaxillary trauma with restricted mouth opening due to bilateral temporomandibular joint dislocation.[22] Adequate retromolar space is an essential prerequisite to introduce the suction catheter and necessary arrangements must be ready to cope with any emergency situation.

There is a trend of rising attention on this useful, but underutilized mode of airway access over the last 25 years. Nearly 90% of the publications on this topic have been reported in PubMed in the last decade. A brief summary of review of literature on the submental intubation in PubMed is tabulated as Table 2. A recent literature review comprising 842 patients and 41 articles cites the success rate of this technique as 100%[15] with duration of the procedure varying between less than 4 min to 30 min. This study also reports of development of a hypertrophic scar in 3 patients out of 842 patients. As aesthetic acceptance of the scar is highly unpredictable, nasal route of airway access, if possible, is always a better choice. The utility of submental intubation is guarded in elective midfacial osteotomy, although there are reports of successful submental intubation in no less than 100 patients. Further research work in larger scale is needed to compare submental intubation with tracheostomy.

Table 2.

Brief summary of review of literature in PubMed over the last 25 years

Conclusion

Submental intubation seems to be an attractive and adaptive option for intraoperative airway control in selected complex craniofacial injuries. This enjoys the advantages of both orotracheal and nasotracheal intubation at the same time. Though it demands some surgical skill, the technique is simple, rapid, and easy to learn. Better cosmesis, minimal complication and lesser expenses are added advantages. The overall increase in operating period by about 20 min is one of its limitations. There is still no consensus regarding superiority of one technique over another as a mode of securing airway in complex craniofacial injury repair. Paucity of published literature (case reports and case series) and quality of evidence limit definite recommendation on its use. Patient's ability to cooperate with the procedure, liaison between the surgeons and the anesthesiologists, experience of airway managers to deal with the situation, and benefits of single versus multiple surgical interventions are important considerations. Prolonged period of time is required for the adequate planning, preparation of the patient, personnel and procedure, which limits the utility of this technique in emergency situations.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Venugopal MG, Singha R, Menon PS, Chattopadhyay PK, Roychowdhury SK. Fractures in the maxillofacial region: A four year retrospective study. Medical Journal Armed Forces India. 2010;66:14–7. doi: 10.1016/S0377-1237(10)80084-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chandra Shekar BR, Reddy CV. A five-year retrospective statistical analysis of maxillofacial injuries in patients admitted and treated at two hospitals of Mysore city. Indian J Dent Res. 2008;19:304–8. doi: 10.4103/0970-9290.44532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arrowsmith JE, Robertshaw HJ, Boyd JD. Nasotracheal intubation in the presence of frontobasal skull fracture. Can J Anaesth. 1998;45:71–5. doi: 10.1007/BF03011998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Anwer HM, Zeitoum IM, Shehata EA. Submandibular approach for tracheal intubation in patients with panfacial fractures. Br J Anaesth. 2007;98:835–40. doi: 10.1093/bja/aem094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Durbin CG., Jr Early complications of tracheostomy. Respir Care. 2005;50:511–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Caron G, Paquin R, Lessard MR, Trepanier CA, Landry PE. Submental endotracheal intubation: An alternative to tracheotomy in patients with midfacial and panfacial fractures. J Trauma Inj Infect Crit Care. 2000;48:235–40. doi: 10.1097/00005373-200002000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kar C, Mukherjee S. Submental intubation: An alternative and cost-effective technique for complex maxillofacial surgeries. J Maxillofac Oral Surg. 2010;9:266–9. doi: 10.1007/s12663-010-0084-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Xue FS, He N, Liao X, Xu XZ, Liu JH. Further observations on retromolar fibreoptic orotracheal intubation in patients with severe trismus. Can J Anaesth. 2011;58:868–9. doi: 10.1007/s12630-011-9535-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Truong A, Truong DT. Retromolar fibreoptic orotracheal intubation in a patient with severe trismus undergoing nasal surgery. Can J Anaesth. 2011;58:460–3. doi: 10.1007/s12630-011-9474-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dutta A, Kumar V, Saha SS, Sood J, Khazanchi RK. Retromolar tracheal tube positioning for patients undergoing faciomaxillary surgery. Can J Anaesth. 2005;52:341. doi: 10.1007/BF03016082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee SS, Huang SH, Wu SH, Sun IF, Chu KS, Lai CS, et al. A review of intraoperative airway management for midface facial bone fracture patients. Ann Plast Surg. 2009;63:162–6. doi: 10.1097/SAP.0b013e3181855156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rungta N. Technique of retromolar and submental intubation in facio-maxillary trauma patients. Ind J Trauma Anaesth Crit Care. 2007;8:573–5. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Arora S, Rattan V, Bharadwaj N. An evaluation of the retromolar space for oral tracheal tube placement for maxillofacial surgery in children. Anesth Analg. 2006;103:1122–6. doi: 10.1213/01.ane.0000247852.09732.ec. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Biglioli F, Mortini P, Goisis M, Bardazzi A, Boari N. Submental orotracheal intubation: An alternative to tracheostomy in transfacial cranial base surgery. Skull Base. 2003;13:189–95. doi: 10.1055/s-2004-817694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jundt JS, Cattano D, Hagberg CA, Wilson JW. Submental intubation: A literature review. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2012;41:46–54. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2011.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Malhotra N. Retromolar intubation-a simple alternative to submental intubation. Anaesthesia. 2006;61:515–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.2006.04635.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kruger E, Thomson WM, Konthasinghe P. Third molar outcomes from age 18 to 26: Findings from a population-based New Zealand longitudinal study. Oral Surg Oral Med Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2001;92:150–5. doi: 10.1067/moe.2001.115461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Altemir FH. The submental route for endotracheal intubation: A new technique. J Maxillofac Surg. 1986;14:64–5. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0503(86)80261-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Meyer C, Valfrey J, Kjartansdorttir T, Wilk A, Barriere P. Indication for and technical refinements of submental intubation in oral and maxillofacial surgery. J Cranio-Maxillofac Surg. 2003;31:383–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jcms.2003.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Eipe N, Neuhoefer E, Rosee GL, Choudhrie R, Samman N, Kreusch T. Submental intubation for cancrum oris: A case report. Pediatr Anesth. 2005;15:1009–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9592.2005.01573.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chandu A, Smith AC, Gebert R. Submental Intubation: An alternative to Short-Term Tracheostomy. Anaesth Intensive Care. 2000;28:193–5. doi: 10.1177/0310057X0002800212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Arya VK, Kumar A, Makkar SS, Sharma RK. Retrograde submental intubation by pharyngeal loop technique in a patient with faciomaxillary trauma and restricted mouth opening. Anesth Analg. 2005;100:534–7. doi: 10.1213/01.ANE.0000142126.86492.7D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Berkovitz Barry KB, Standring S., editors. Gray's Anatomy. The Anatomical basis of Clinical Practice. 39th ed. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone-Elsevier; 2005. Triangles of neck. Neck. Chapter 31; p. 553. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Berry MM, Standring S, Bannister LH, Banister LH, Mertin MM, editors. Gray's Anatomy. 38th ed. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone; 1995. Hypoglossal nerve, Figure no. 8.357. Nervous system (section 8) p. 1257. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Berry MM, Standring S, Bannister LH, Banister LH, Mertin MM, editors. Gray's Anatomy. 38th ed. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone; 1995. Lingual nerve. Nervous system (section 8) p. 1239. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ramsay CA, Dhaliwal SK. Retrograde and submental intubation. Atlas Oral Maxillary Surg Clin N Am. 2010;18:61–8. doi: 10.1016/j.cxom.2009.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gadre KS, Waknis PP. Transmylohyoid/Submental intubation: Review, analysis, and refinements. J Craniofac Surg. 2010;21:516–9. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0b013e3181d023d3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Green JD, Moore UJ. A modification of sub-mental intubation. Br J Anaesth. 1996;77:789–91. doi: 10.1093/bja/77.6.789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Scafati CT, Maio G, Alberti F, Scafati ST, Grimaldi PL. Submento-submandibular intubation: Is the subperiosteal passage essential? Experience in 107 consecutive cases. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2006;44:12–4. doi: 10.1016/j.bjoms.2005.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.MacInnis E, Baig M. A modified submental approach to oral endotracheal intubation. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1999;28:269–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Paetkau D, Strand M, Onc B. Submental orotracheal intubation for maxillofacial surgery. Anaesthesiology. 2000;92:912–4. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200003000-00063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mak PH, Ooi RG. Submental intubation in a patient with beta-thalassaemia major undergoing elective maxillary and mandibular osteotomies. Br J Anaesth. 2002;88:288–91. doi: 10.1093/bja/88.2.288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hanamoto H, Morimoto Y, Niwa H, Iida S, Aikawa T. A new modification for safer submental orotracheal intubation. J Anesth. 2011;25:781–3. doi: 10.1007/s00540-011-1204-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Drolet P, Girard M, Poirier J, Grenier Y. Facilitating submental endotracheal intubation with an endotracheal tube exchanger. Anesth Analg. 2000;90:222. doi: 10.1097/00000539-200001000-00044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nyarady Z, Sari F, Olasz L, Nyarady J. Submental endotracheal intubation in concurrent orthognathic surgery: A technical note. J Cranio-Maxillofac Surg. 2006;34:362–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jcms.2006.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Biswas BK, Joshi S, Bhattacharyya P, Gupta PK, Baniwal S. Percutaneous dialational tracheostomy kit: An aid to submental intubation. Anesth Analg. 2006;103:1055. doi: 10.1213/01.ane.0000239041.31044.c9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Amin M, Dill-Russell P, Mainsali M, Lee R, Sinton I. Facial fracture and submental tracheal intubation. Anaesthesia. 2002;57:1195–212. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2044.2002.02624_1.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mahmood S, Lello GE. Oral endotracheal intubation: Median submental (retrogenial) approach. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2002;60:473–4. doi: 10.1053/joms.2002.31244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lima SM, Jr, Asprino L, Moreira RW, de Moraes M. A retrospective analysis of submental intubation in maxillofacial trauma patients. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2011;69:2001–5. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2010.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Adeyemo WL, Ogunlewe MO, Desalu I, Akanmu ON, Ladeinde AL. Submental / Transmylohyoid intubation in maxillofacial surgery: Report of two cases. Niger J Clin Pract. 2011;14:98–101. doi: 10.4103/1119-3077.79266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Altemir FH, Montero SH. The submental route revisited using the laryngeal mask airway: A technical note. J Cranio-Maxillofac Surg. 2000;28:343–4. doi: 10.1054/jcms.2000.0175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hernández Altemir F, Hernández Montero S, Moros Peña M. Combitube SA through submental route. A technical innovation. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2003;31:257–9. doi: 10.1016/s1010-5182(03)00026-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Malhotra N, Bhardwaj N, Chari P. Submental endotracheal intubation: A useful alternative to tracheostomy. Indian J Anaesth. 2002;46:400–2. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Stranc MF, Skoracki R. A complicationsubmandibular intubation in a panfacial fracture patients. J Cranio-Maxillofac Surg. 2001;29:174–6. doi: 10.1054/jcms.2001.0201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Adelson RT. Submental intubation to facilitate the management of maxillofacial trauma. Ear Nose Throat J. 2011;90:412–4. doi: 10.1177/014556131109000905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gordon NC, Tolstunov L. Submental approach to oroendotracheal intubation in patients with midfacial fractures. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1995;79:269–72. doi: 10.1016/s1079-2104(05)80218-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Labbe D, Kaluzinski E, Badie-Modiri B, Rakotonirina N, Berenger C. Intubation sous-mentale en traumatologie cranio-maxilo-facial Note technique. Ann Chir Plast Esthet. 1998;43:248–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yoon KB, Choi BH, Chang HS, Lim HK. Management of detachment of pilot balloon during intraoral repositioning of the submental endotracheal tube. Yonsei Med J. 2004;45:748–50. doi: 10.3349/ymj.2004.45.4.748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Manganello-Souza LC, Tenorio-Cabezas N, Piccinini Filho L. Submental method for orotracheal intubation in treating facial trauma. Sao Paulo Med J. 1998;116:1829–32. doi: 10.1590/s1516-31801998000500010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nwoku AL, Al-Balawi SA, Al-Zahrani SA. A modified method of submental oroendotracheal intubation. Saudi Med J. 2002;23:73–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ball DR, Clark M, Jefferson P, Stewart T. Improved submental intubation. Anaesthesia. 2003;58:189. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lim HK, Kim IK, Han JU, Kim TJ, Lee CS, Song JH, et al. Modified submental orotracheal intubation using the blue cap on the end of the thoracic catheter. Yonsei Med J. 2003;44:919–22. doi: 10.3349/ymj.2003.44.5.919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Nyárády Z, Sári F, Olasz L, Nyárády J. Modified submental endotracheal intubation in concurrent orthognathic surgery. Mund Kiefer Gesichtschir. 2004;8:387–9. doi: 10.1007/s10006-004-0570-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kim KF, Doriot R, Morse MA, Al-Attar A, Dufresne CR. Alternative to tracheostomy: submental intubation in craniomaxillofacial trauma. J Craniofac Surg. 2005;16:498–500. doi: 10.1097/01.scs.0000148184.27454.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kim KJ, Lee JS, Kim HJ, Ha JY, Park H, Han DW. Submental intubation with reinforced tube for intubating laryngeal mask airway. Yonsei Med J. 2005;46:571–4. doi: 10.3349/ymj.2005.46.4.571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Caubi AF, Vasconcelos BC, Vasconcellos RJ, de Morais HH, Rocha NS. Submental intubation in oral maxillofacial surgery: Review of the literature and analysis of 13 cases. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2008;13:E197–200. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Schütz P, Hamed HH. Submental intubation versus tracheostomy in maxillofacial trauma patients. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2008;66:1404–9. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2007.12.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Chandu A, Witherow H, Stewart A. Submental intubation in orthognathic surgery: Initial experience. Br J Oral Maxillofacial Surg. 2008;46:561–3. doi: 10.1016/j.bjoms.2008.02.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Babu I, Sagtani A, Jain N, Bawa SN. Submental tracheal intubation in a case of panfacial trauma. Kathmandu Univ Med J (KUMJ) 2008;6:102–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sharma RK, Tuli P, Cyriac C, Parashar A, Makkar S. Submental tracheal intubation in oromaxillofacial surgery. Indian J Plast Surg. 2008;41:15–9. doi: 10.4103/0970-0358.41105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Elizar’eva NL, Rovina AK, Levin OB, Kolosov AN. [Submental tracheal intubation is an alternative to tracheostomy in oral surgery] Anesteziol Reanimatol. 2008;3:22–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Langford R. Complication of submental intubation. Anaesth Intensive Care. 2009;37:325–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Uma G, Viswanathan PN, Nagaraja PS. Submandibular approach for tracheal intubation-A Case Report. Indian J Anaesth. 2009;53:84–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Garg M, Rastogi B, Jain M, Chauhan H, Bansal V. Submental intubation in panfacial injuries: our experience. Dent Traumatol. 2010;26:90–3. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-9657.2009.00850.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Navaneetham A, Thangaswamy VS, Rao N. J Maxillofac Oral Surg. 2010;9:64–7. doi: 10.1007/s12663-010-0018-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Agrawal M, Kang LS. Midline submental orotracheal intubation in maxillofacial injuries: A substitute to tracheostomy where postoperative mechanical ventilation is not required. J Anaesthesiol Clin Pharmacol. 2010;26:498–502. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Shetty PM, Yadav SK, Upadya M. Submental intubation in patients with panfacial fractures: A prospective study. Indian J Anaesth. 2011;55:299–304. doi: 10.4103/0019-5049.82685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]