1. Introduction

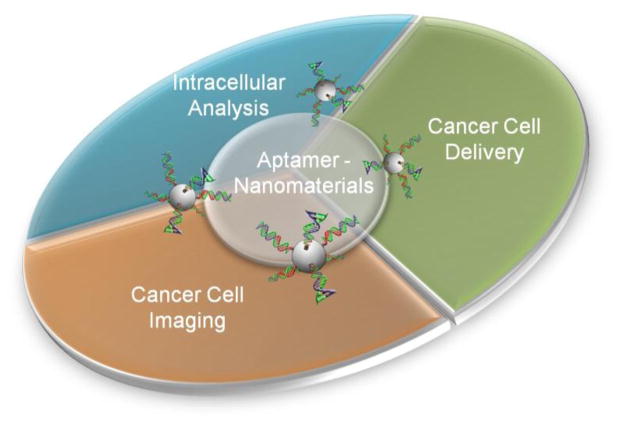

The advance in studying inter- and intra-cellular biochemical processes has made important contributions to our understanding of biology in the past several decades. Such fundamental advancement also has significant impact on cell imaging and drug delivery. Technologies such as fluorescent resonant energy transfer (FRET), single molecular imaging, and gene regulation have allowed unparalleled insights into cellular functions and mechanisms in drug delivery. An exciting development in this area is the combination of unique optical or magnetic properties of nanomaterials with high selectivity of DNA/RNA aptamers. Together these aptamer-functionalized nanomaterials have enabled novel analytical techniques that advance our understanding and treatment of disease, aging, and cancer [1–3]. This review highlights recent work on using DNA aptamer-nanomaterial hybrid platforms for the applications in cellular analysis, imaging and targeted drug delivery (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

A general illustration of the three cellular analysis and therapeutic applications of aptamer-functionalized nanoparticles.

2. Overview of Nanomaterials and Aptamers

2.1 Nanomaterials for Cellular Applications

Metal nanoparticles have been used widely for the studies of cellular uptake and analysis due to their simple synthesis, easy modifications, and biocompatibility. For applications in cellular analysis, gold and silver nanoparticles have been especially common owing to their excellent plasmonic properties, which have enabled significant advances in localized surface plasmon resonance (LSPR) for applications such as surface enhanced Raman spectroscopy [4]. When in close proximity to the surface of a plasmonic metal, the Raman signal can achieve 1014 enhancements, due to electromagnetic enhancements from plasmonic “hot spots”. Nanoparticles [5], nanoshells [6], nanoflowers [7], nanorods [8], and many other nanostructures [9] have all been recently been explored for their plasmonic properties in cell imaging, uptake mechanisms, and detection of various analytes [10]. The reader is directed to other recent reviews that focus on SERS/plasmonic applications of nanoparticles for cellular analysis [11*].

Other types of nanomaterials such as silica nanoparticles, quantum dots (QDs), and carbon based nanomaterials have also been applied in cellular applications [12–14]. Nanosized silica is widely known for excellent compatibility and has been used extensively in cellular studies [15]. More recently, mesoporous structures dramatically increased the surface area of silica nanoparticles and enabled high loading of cargo for cellular imaging and delivery [16]. Another material of interests is semiconducting QDs. Because of their fluorescence stability, board absorption and narrow emission band, they are uniquely suited for high resolution [17] and multiplex imaging of cells [18*]. Carbon based nanomaterials such as carbon nanotubes, fullerenes, and most recently graphene and graphene oxide are also promising nanomaterials for cellular applications, including the use of stabilized graphene oxide in cellular imaging and drug delivery [19–21].

2.2 Aptamers

The above nanomaterials are promising in cellular applications as efficient reporters and carriers However, the applications of non-functionalized nanomaterials have remained scarce due to limited functionality, lack of target specificity, and low intracellular stability. Aptamers are short single stranded DNA or RNA sequences that are selected and refined for highly specific binding to a target of interest by in vitro selection or systematic evolution of ligands by exponential enrichment (SELEX) [22–24]. In the past two decades, the technology has evolved quickly and has since found particular interest in environmental sensing, cancer imaging/diagnosis, and disease therapy [25–32]. Due to its automated synthesis, high stability, and well established selection process, DNA aptamers have become one of the most promising techniques for introducing target specificity to nanomaterials for intracellular imaging, diagnosis, and therapy [33**,34]. This review highlights recent work on using aptamer-nanomaterial hybrid platforms for the applications in cellular analysis, imaging and targeted drug delivery.

3. Aptamer-Modified Nanomaterials for Analysis of intracellular components and metabolites

Nanomaterials with good cell uptake, such as gold and carbon-based nanocomposites, can be modified by aptamers for the analysis of intracellular components and metabolites.

3.1 AuNP-aptamer Hybrid

Gold nanoparticles (AuNPs) are the most characterized nanomaterials for intracellular analysis. AuNPs exhibit high stability, good biocompatibility, excellent optical and electronic properties, and diverse surface functionalizations. In addition to cellular applications shown below, aptamer-modified AuNPs have also been extensively applied for detecting metal ion and biomolecular targets [35,36].

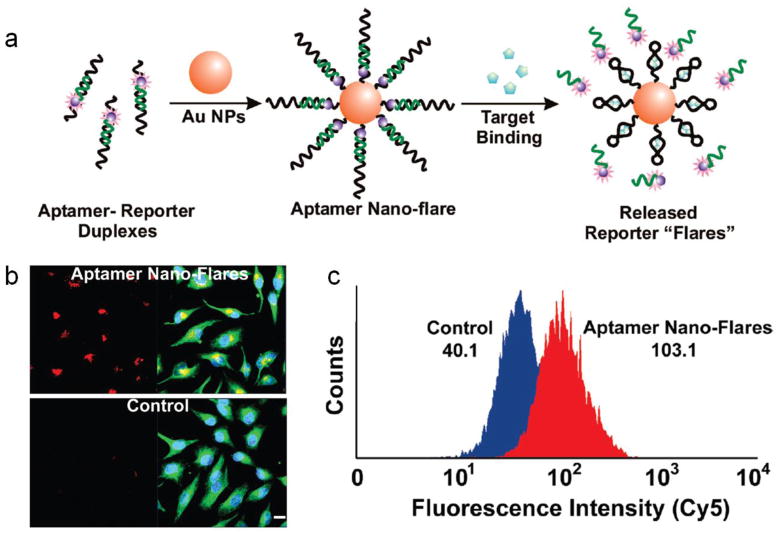

Mirkin and co-workers developed an aptamer-AuNP hybrid with fluorescent reporters, termed as “nanoflare”, which can quantitatively detect analytes inside living cells [37**]. The aptamer modified nanoflares are highly stable, readily taken by cells, and were used to detect intracellular ATP concentrations at 1~2 mM (Figure 2) [38]. Similar methodology have been be applied to detect gene expression, message RNA in living cells by using antisense DNA strand or molecular beacon constructs [39,40].

Figure 2.

(a). Schematic view of the basic design and stimuli-responsive mechanism of aptamer nano-flare. (b). Fluorescence microscopy images of HeLa cells incubated with aptamer nano-flares and control particles. (c). Flow cytometry results of fluorescent intensity (Cy5) of cells treated with aptamer nano-flares and control particles. Adapted from [38].

3.2 SWCNTs and Graphene

Carbon-based materials, such as single-walled carbon nanotubes (SWCNTs) and graphene have attracted considerable interest due to their high surface area, mechanical strength, high electrical conductivity, and photoluminescence. These unique properties offer SWCNTs and graphene good opportunities for biosensing and bioimaging applications. For example, DNA strands can be adsorbed onto SWCNT/graphene through strong pi-stacking interactions and released through hybridization or structure switching [41]. By taking advantage of the high quenching efficiency of carbon structures, Cha et al. was able to develop an intracellular insulin sensor with wide detection range from 10 μM to 2 mM [42].

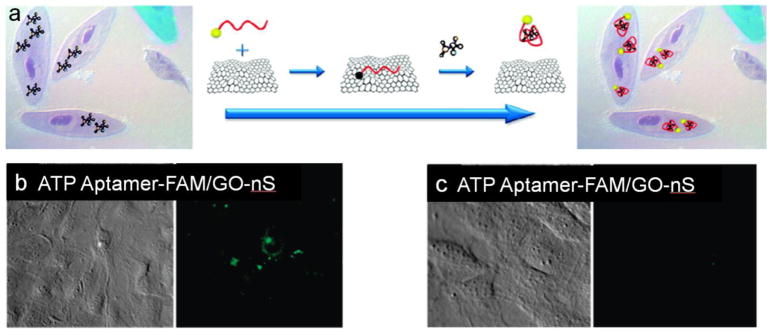

Graphene derivatives featuring excellent optical and electrical properties recently emerged as another promising carbon-based nanomaterial for in situ analysis of small molecules in living cells. For example, Wang et al. reported the usage of graphene oxide nanosheet as quenchers for aptamer-based intracellular APT detection [43**]. They synthesized a nanocomplex with carboxyfluorescein (FAM) modified ATP aptamer strands absorbed on graphene oxide nanosheets (GO-nS) resulting in significant quenching of fluorescent intensity. They further demonstrated the effective uptake of aptamer-FAM/GO-nS nanocomplex into JB6 cells and fluorescence recovery after adding ATP molecules (Figure 3). They reported in situ intracellular ATP detection with a detection limit as low as 10 μM.

Figure 3.

(a). Schematic illustration of in situ molecular probing in living cells by using aptamer/GO-nS nanocomplex. (b). JB6 cells specific uptake of ATP aptamer-FAM/GO-nS samples (b) and random DNA-FAM/GO-nS samples (c). Images were taken under differential interference contrast and wide-field fluorescence. Adapted from [43**].

4. Aptamer-Functionalized Nanomaterials for Cell-Specific Imaging and Drug Delivery

In addition to intracellular analysis, another exciting application of aptamer functionalized nanomaterials is toward cancer cell imaging and targeted drug delivery.

4.1 Cancer Cell Targeting and Imaging

Aptamers, as molecular probes with high specificity and selectivity, can readily distinguish between cancerous and healthy cells at molecular level. The combination of aptamers with nanomaterials as signal reporting groups therefore represents a powerful diagnostic tool for the detection of cancer and diseases in early stage.

Yin et al. reported a one-step method for the synthesis of DNA-aptamer templated fluorescent silver nanoclusters (AgNCs) [44]. The Sgc8c aptamer strands were immobilized onto AgNCs through cytosine-rich sequence, and the resulting Sgc8c-modified AgNCs showed specific targeting and fluorescent labeling capabilities to CCRF-CEM cancer cell over control cells. In addition to the fluorescence properties, the tunable LSPR properties of AgNPs were also utilized for cellular imaging. Chen et al. reported that the prion protein (PrPc) aptamer modified AgNPs could be used as targeted contrast imaging agents for both dark-field light scattering and TEM imaging of SK-N-SH cells. They further observed that PrPc-AgNPs could be internalized into plasma membrane, lysosome and endocytic structure through aptamer-mediated endocytosis [45].

Aptamer modified AgNPs were also used to specifically target and image the sub-compartments of live cells. In 2011, Sun and co-workers reported that by artificially adding tandem cytocines Sgc8c aptamer, they were able to generate an Ag cluster that targeted the nucleus of CCRP-CEM cells [46].

Kim and co-workers reported a cancer-specific multimodal imaging probe consisting of cobalt–ferrite nanoparticle protected by a silica shell and coated by fluorescent rhodamine. They demonstrated that the AS1411 aptamer-multimodal nanoparticle system not only enabled the targeted fluorescence imaging of nucleolin-expressing C6 cells, but also allowed radionuclide and MRI imaging in vivo and in vitro [47]. In addition, Colin et al. combined fluorophore-doped silica and silica-coated magnetic nanoparticles modified with highly selective aptamers to detect and extract CCRF-CEM targeted cells in a variety of mixtures [48**]. They also systematically studied the effect of nanoparticle size, conjugation chemistry, and aptamer sequences on the selectivity and sensitivity of the dual-particle assays.

Besides aptamer modified metal and silica nanoparticles, an extracellular supramolecular reticular DNA-QD sheath was reported by Zhang and co-worker in high-intensity fluorescence imaging [49]. At physiological temperature, the DNA-QD sheath readily recognized and bound to Ramos cells in a cell-specific manner, and was used to accurately quantify the Ramos cells within the range of 10 to 1000 cells. In addition, electrochemical sensors [50] and electro chemiluminescence methods [51**] have also been reported as detection methods for aptamer-QDs based cancer cell detection.

4.2 Cell-Specific Drug Delivery

Compared to conventional passive anticancer drug delivery system, targeted delivery attracts more attention and can be achieved by disease-specific recognition of tumor cells. Aptamer-functionalized nanoparticles have also been widely used for cancer cell specific drug delivery.

In 2011, Gao et al. reported the application of thrombin aptamer-functionalized TBA-tethered lipid-coated mesoporous silica nanoparticles (TBA-lipid-MSN) and demonstrated effective recognition of thrombin and suppression of Hela cell growth by extracellularly disturbing PAR-1 receptor signaling. Moreover, the efficient delivery of anticancer drug Dtxl also contributed to the effective cytotoxicity in the cytoplasm [52].

In collaboration with Wong and Cheng groups, our group recently reported cell-specific drug delivery system based on aptamer modified liposomes. Liposomes encapsulated with anticancer drug cisplatin were conjugated with AS1411 DNA aptamers that specifically bound to nucleolin overexpressed on the cancer cell membrane. We demonstrated that the aptamer-liposomes-cisplatin composite could be delivered into the target MCF-7 cancer cells but not into LNCaP cells as control. Moreover, the release of cisplatin was successfully controlled by introducing a complementary DNA strand of the aptamer as an antidote [53**]. Another type of biological vesicle, micelle, was also reported for aptamer-mediated targeted drug delivery by Wu et al., and the TDO5 aptamer modified micelle was found to exhibit specificity to Ramos cells [54**].

Aptamer-modified polymer nanoparticle is also a promising delivery system. For example, Jiang et al. developed a polymer nanoparticle based drug delivery system by conjugating AS1411 aptamers targeting the cancer cells and endothelia cells in angiogenic blood vessels to the surface of PEG-PLGA nanoparticles. In the tested C6 glioma cells, aptamer-nucleolin specific binding resulted in the cellular association of nanoparticles and thereby enhanced the cytotoxicity of the paclitaxel (PTX) delivery. They suggested the promise of utilizing Ap-PTX-NP as therapeutic drug delivery platform for gliomas treatment [55].

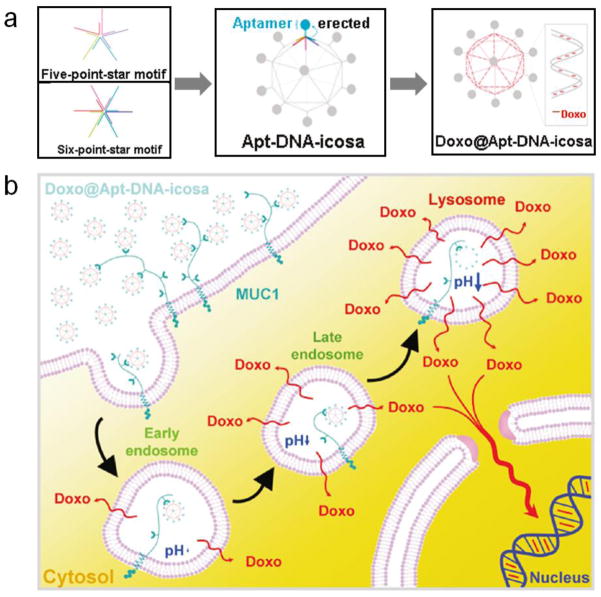

Moreover, novel nanostructures have also been explored as potential targeted drug delivery systems. Huang and co-workers reported using 3D DNA Icosahedral as a carrier for doxorubicin. MUC 1 aptamers were conjugated to distinct five-point-star and six-point-star motifs through DNA hybridization before the formation of DNA polyhedra. They demonstrated that aptamer-conjugated doxorubicin-intercalated DNA icosahedra showed a specific and efficient therapeutic effect for epithelial cancer cells [56**].

5. Perspective

The emerging demands for more in depth study of cellular mechanism and therapy has emphasized the importance of methodologies for cellular analysis and delivery. The recent development of nanotechnology has brought about many nanomaterials as signal reporters and delivery carriers that are more efficient than classic materials for cellular applications. Along with the advantages of nanomaterials, the functionalization of nucleic acid aptamers as recognizing and targeting molecules onto these nanomaterials has successfully realized highly selective and efficient cellular analysis, imaging and targeted delivery. Within the past two years, a number of works shown above have revealed the promise of aptamer-functionalized nanomaterials in cellular analysis and delivery. These nanoconjugates will continuously play more and more important roles in cellular and many other applications.

Future exploration of other new nanomaterials with better cellular compatibility, optical property, and delivery efficiency is anticipated to advance this research field. Silica-based nanoparticles, quantum dots and mesoporous nanomaterials have been found to exhibit excellent biocompatibility, optical property and drug load, respectively. The combination of these materials into hybrid nanomaterials can yield ideal nanocomposites with all the desired properties. In addition, nanomaterials with multiple functions and controlled spatial distributions, such as Janus nanoparticles, can further expand their functions and cooperativity for potential cellular application [57,58].

On the other hand, the selection and evolution of new nucleic acid aptamers for more cellular targets are the basis to extend the applications of aptamer-functionalized nanomaterials in cellular analysis and delivery for studying more types of cells and their cellular processes. Beside in vitro selection from random nucleic acid pools, the introduction of unnatural nucleotides into the nucleic acid pools to improve the diversity of functional groups may further enhance the chance to obtain aptamers for more cellular targets [59].

Finally, to make even bigger impact on human health, the advance of these studies in cells needs to be translated into analysis, imaging and targeted delivery in animals or even human clinical trials. To achieve the goals, even more selective aptamer, more effective nanomaterials and better combination of the two are required and the safety of these nanomaterials in vivo needs to be carefully evaluated.

Figure 4.

(a). Schematic view of self-assembly of aptamer modified, doxorubicin-loaded DNA icosahedra (Doxo@Apt-DNA-icosa). (b). Proposed MUC1 aptamer-mediated endocytosis mechanism of Doxo@Apt-DNA-icosa. Adapted from [56**].

Highlights.

DNA Aptamer-nanomaterials combine unique optical or magnetic properties of nanomaterials with high selectivity of aptamers.

Together they have enabled novel analytical techniques that advance our understanding of health and treatment of diseases.

Recent work on using DNA aptamer-nanomaterials for analysis of intracellular components and metabolites are reviewed.

Their recent applications in targeting and imaging of cancer cells and in cell-specific drug delivery are also highlighted.

Acknowledgments

We thank the US National Institute of Health (ES016865) and the National Science Foundation (DMR-0117792, CTS-0120978 and DMI-0328162) for financial support.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Cheng J, Teply BA, Sherifi I, Sung J, Luther G, Gu FX, Levy-Nissenbaum E, Radovic-Moreno AF, Langer R, Farokhzad OC. Formulation of functionalized PLGA-PEG nanoparticles for in vivo targeted drug delivery. Biomaterials. 2007;28:869–876. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2006.09.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kolishetti N, Dhar S, Valencia PM, Lin LQ, Karnik R, Lippard SJ, Langer R, Farokhzad OC. Engineering of self-assembled nanoparticle platform for precisely controlled combination drug therapy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:17939–17944. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1011368107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dhar S, Kolishetti N, Lippard SJ, Farokhzad OC. Targeted delivery of a cisplatin prodrug for safer and more effective prostate cancer therapy in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:1850–1855. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1011379108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sathuluri RR, Yoshikawa H, Shimizu E, Saito M, Tamiya E. Gold Nanoparticle-Based Surface-Enhanced Raman Scattering for Noninvasive Molecular Probing of Embryonic Stem Cell Differentiation. PLoS One. 2011:6. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0022802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ando J, Fujita K, Smith NI, Kawata S. Dynamic SERS Imaging of Cellular Transport Pathways with Endocytosed Gold Nanoparticles. Nano Lett. 2011;11:5344–5348. doi: 10.1021/nl202877r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Garrett N, Whiteman M, Moger J. Imaging the uptake of gold nanoshells in live cells using plasmon resonance enhanced four wave mixing microscopy. Opt Express. 2011;19:17563–17574. doi: 10.1364/OE.19.017563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang ZD, Zhang JQ, Ekman JM, Kenis PJA, Lu Y. DNA-Mediated Control of Metal Nanoparticle Shape: One-Pot Synthesis and Cellular Uptake of Highly Stable and Functional Gold Nanoflowers. Nano Lett. 2010;10:1886–1891. doi: 10.1021/nl100675p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jung Y, Reif R, Zeng YG, Wang RK. Three-Dimensional High-Resolution Imaging of Gold Nanorods Uptake in Sentinel Lymph Nodes. Nano Lett. 2011;11:2938–2943. doi: 10.1021/nl2014394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bartczak D, Muskens OL, Nitti S, Sanchez-Elsner T, Millar TM, Kanaras AG. Interactions of Human Endothelial Cells with Gold Nanoparticles of Different Morphologies. Small. 2012;8:122–130. doi: 10.1002/smll.201101422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ding CF, Qian SW, Wang ZF, Qu B. Electrochemical cytosensor based on gold nanoparticles for the determination of carbohydrate on cell surface. Anal Biochem. 2011;414:84–87. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2011.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11*.Bantz KC, Meyer AF, Wittenberg NJ, Im H, Kurtulus O, Lee SH, Lindquist NC, Oh SH, Haynes CL. Recent progress in SERS biosensing. Phys Chem Chem Phys. 2011;13:11551–11567. doi: 10.1039/c0cp01841d. A perspective on the recent developments in surface-enhanced Raman scattering (SERS) for biosensing. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ma N, Yang J, Stewart KM, Kelley SO. DNA-passivated CdS nanocrystals: Luminescence, bioimaging, and toxicity profiles. Langmuir. 2007;23:12783–12787. doi: 10.1021/la7017727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ma N, Tikhomirov G, Kelley SO. Nucleic Acid-Passivated Semiconductor Nanocrystals: Biomolecular Templating of Form and Function. Acc Chem Res. 2010;43:173–180. doi: 10.1021/ar900046n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Park HS, Kim C, Lee HJ, Choi JH, Lee SG, Yun YP, Kwon IC, Lee SJ, Jeong SY, Lee SC. A mesoporous silica nanoparticle with charge-convertible pore walls for efficient intracellular protein delivery. Nanotechnology. 2010:21. doi: 10.1088/0957-4484/21/22/225101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cai ZW, Ye ZM, Yang XW, Chang YL, Wang HF, Liu YF, Cao AN. Encapsulated enhanced green fluorescence protein in silica nanoparticle for cellular imaging. Nanoscale. 2011;3:1974–1976. doi: 10.1039/c0nr00956c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liu YT, Mi Y, Zhao J, Feng SS. Multifunctional silica nanoparticles for targeted delivery of hydrophobic imaging and therapeutic agents. Int J Pharm. 2011;421:370–378. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2011.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pinaud F, Clarke S, Sittner A, Dahan M. Probing cellular events, one quantum dot at a time. Nat Methods. 2010;7:275–285. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18*.Stasiuk GJ, Tamang S, Imbert D, Poillot C, Giardiello M, Tisseyre C, Barbier EL, Fries PH, de Waard M, Reiss P, et al. Cell-Permeable Ln(III) Chelate-Functionalized InP Quantum Dots As Multimodal Imaging Agents. ACS Nano. 2011;5:8193–8201. doi: 10.1021/nn202839w. A review about recent advances of using semiconductor quantum dot probes for monitoring the behavior of single molecules in living cells. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Peng C, Hu WB, Zhou YT, Fan CH, Huang Q. Intracellular Imaging with a Graphene-Based Fluorescent Probe. Small. 2010;6:1686–1692. doi: 10.1002/smll.201000560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liu KP, Zhang JJ, Cheng FF, Zheng TT, Wang CM, Zhu JJ. Green and facile synthesis of highly biocompatible graphene nanosheets and its application for cellular imaging and drug delivery. J Mater Chem. 2011;21:12034–12040. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hong BJ, Compton OC, An Z, Eryazici I, Nguyen ST. Successful Stabilization of Graphene Oxide in Electrolyte Solutions: Enhancement of Biofunctionalization and Cellular Uptake. ACS Nano. 2012;6:63–73. doi: 10.1021/nn202355p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ellington AD, Szostak JW. Invitro Selection of Rna Molecules That Bind Specific Ligands. Nature. 1990;346:818–822. doi: 10.1038/346818a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tuerk C, Gold L. Systematic Evolution of Ligands by Exponential Enrichment - Rna Ligands to Bacteriophage-T4 DNA-Polymerase. Science. 1990;249:505–510. doi: 10.1126/science.2200121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Beaudry AA, Joyce GF. Directed Evolution of an Rna Enzyme. Science. 1992;257:635–641. doi: 10.1126/science.1496376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lu Y, Liu JW. Smart nanomaterials inspired by biology: Dynamic assembly of error-free nanomaterials in response to multiple chemical and biological stimuli. Acc Chem Res. 2007;40:315–323. doi: 10.1021/ar600053g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Willner I, Zayats M. Electronic aptamer-based sensors. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2007;46:6408–6418. doi: 10.1002/anie.200604524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhao W, Ali MM, Brook MA, Li Y. Rolling circle amplification: Applications in nanotechnology and biodetection with functional nucleic acids. Angewandte Chemie-International Edition. 2008;47:6330–6337. doi: 10.1002/anie.200705982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cho EJ, Lee JW, Ellington AD. Applications of Aptamers as Sensors. Annu Rev Anal Chem. 2009;2:241–264. doi: 10.1146/annurev.anchem.1.031207.112851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fang XH, Tan WH. Aptamers Generated from Cell-SELEX for Molecular Medicine: A Chemical Biology Approach. Acc Chem Res. 2010;43:48–57. doi: 10.1021/ar900101s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li D, Song S, Fan C. Target-Responsive Structural Switching for Nucleic Acid-Based Sensors. Acc Chem Res. 2010;43:631–641. doi: 10.1021/ar900245u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lubin AA, Plaxco KW. Folding-based electrochemical biosensors: The case for responsive nucleic acid architectures. Acc Chem Res. 2010;43:496–505. doi: 10.1021/ar900165x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Oh SS, Plakos K, Lou XH, Xiao Y, Soh HT. In vitro selection of structure-switching, self-reporting aptamers. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:14053–14058. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1009172107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33**.Liu JW, Cao ZH, Lu Y. Functional Nucleic Acid Sensors. Chem Rev. 2009;109:1948–1998. doi: 10.1021/cr030183i. A comprehensive review on three different types of functial nucleic acid sensors: nucleic acid enzyme, aptamer, and aptazyme -based sensors. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang ZD, Lu Y. Functional DNA directed assembly of nanomaterials for biosensing. J Mater Chem. 2009;19:1788–1798. doi: 10.1039/B813939C. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang ZD, Lee JH, Lu Y. Label-free colorimetric detection of lead ions with a nanomolar detection limit and tunable dynamic range by using gold nanoparticles and DNAzyme. Adv Mater. 2008;20:3263–3267. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mazumdar D, Liu JW, Lu G, Zhou JZ, Lu Y. Easy-to-use dipstick tests for detection of lead in paints using non-cross-linked gold nanoparticle-DNAzyme conjugates. Chem Commun. 2010;46:1416–1418. doi: 10.1039/b917772h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37**.Seferos DS, Giljohann DA, Hill HD, Prigodich AE, Mirkin CA. Nano-flares: Probes for transfection and mRNA detection in living cells. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:15477–15479. doi: 10.1021/ja0776529. First demonstration of using oligonucleotide-modified gold nanoparticle as transfection, recognition and signaling agents for detecting mRNA in living cells. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zheng D, Seferos DS, Giljohann DA, Patel PC, Mirkin CA. Aptamer Nano-flares for Molecular Detection in Living Cells. Nano Lett. 2009;9:3258–3261. doi: 10.1021/nl901517b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jayagopal A, Halfpenny KC, Perez JW, Wright DW. Hairpin DNA-Functionalized Gold Colloids for the Imaging of mRNA in Live Cells. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:9789–9796. doi: 10.1021/ja102585v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Prigodich AE, Randeria PS, Briley WE, Kim NJ, Daniel WL, Giljohann DA, Mirkin CA. Multiplexed Nanoflares: mRNA Detection in Live Cells. Anal Chem. 2012;84:2062–2066. doi: 10.1021/ac202648w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lu CH, Yang HH, Zhu CL, Chen X, Chen GN. A Graphene Platform for Sensing Biomolecules. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2009;48:4785–4787. doi: 10.1002/anie.200901479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cha TG, Baker BA, Sauffer MD, Salgado J, Jaroch D, Rickus JL, Porterfield DM, Choi JH. Optical Nanosensor Architecture for Cell-Signaling Molecules Using DNA Aptamer-Coated Carbon Nanotubes. ACS Nano. 2011;5:4236–4244. doi: 10.1021/nn201323h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43**.Wang Y, Li ZH, Hu DH, Lin CT, Li JH, Lin YH. Aptamer/Graphene Oxide Nanocomplex for in Situ Molecular Probing in Living Cells. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:9274–9276. doi: 10.1021/ja103169v. First demonstration of aptamer-graphene oxide complex for detection of DNA and proteins in living cells. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yin JJ, He XX, Wang KM, Qing ZH, Wu X, Shi H, Yang XH. One-step engineering of silver nanoclusters-aptamer assemblies as luminescent labels to target tumor cells. Nanoscale. 2012;4:110–112. doi: 10.1039/c1nr11265a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chen LQ, Xiao SJ, Peng L, Wu T, Ling J, Li YF, Huang CZ. Aptamer-Based Silver Nanoparticles Used for Intracellular Protein Imaging and Single Nanoparticle Spectral Analysis. J Phys Chem B. 2010;114:3655–3659. doi: 10.1021/jp9104618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sun ZP, Wang YL, Wei YT, Liu R, Zhu HR, Cui YY, Zhao YL, Gao XY. Ag cluster-aptamer hybrid: specifically marking the nucleus of live cells. Chem Commun. 2011;47:11960–11962. doi: 10.1039/c1cc14652a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hwang DW, Ko HY, Lee JH, Kang H, Ryu SH, Song IC, Lee DS, Kim S. A Nucleolin-Targeted Multimodal Nanoparticle Imaging Probe for Tracking Cancer Cells Using an Aptamer. J Nucl Med. 2010;51:98–105. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.109.069880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48*.Medley CD, Bamrungsap S, Tan WH, Smith JE. Aptamer-Conjugated Nanoparticles for Cancer Cell Detection. Anal Chem. 2011;83:727–734. doi: 10.1021/ac102263v. Detailed discussion of the factors affecting the conjugation of aptamers to nanoparticles, including particle size,coupling chemistry, and aptamer sequences. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhong H, Zhang QL, Zhang SS. High-Intensity Fluorescence Imaging and Sensitive Electrochemical Detection of Cancer Cells by using an Extracellular Supramolecular Reticular DNA-Quantum Dot Sheath. Chem Eur J. 2011;17:8388–8394. doi: 10.1002/chem.201003585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Li JJ, Xu M, Huang HP, Zhou JJ, Abdel-Halim ES, Zhang JR, Zhu JJ. Aptamer-quantum dots conjugates-based ultrasensitive competitive electrochemical cytosensor for the detection of tumor cell. Talanta. 2011;85:2113–2120. doi: 10.1016/j.talanta.2011.07.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51*.Jie GF, Wang L, Yuan JX, Zhang SS. Versatile Electrochemiluminescence Assays for Cancer Cells Based on Dendrimer/CdSe-ZnS-Quantum Dot Nanoclusters. Anal Chem. 2011;83:3873–3880. doi: 10.1021/ac200383z. Fabrication of the dendrimer/quantum dot nanocluster and the usage of it as an electrochemiluminescence probe for versatile assays of cancer cells. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gao L, Cui Y, He Q, Yang Y, Fei JB, Li JB. Selective Recognition of Co-assembled Thrombin Aptamer and Docetaxel on Mesoporous Silica Nanoparticles against Tumor Cell Proliferation. Chem Eur J. 2011;17:13170–13174. doi: 10.1002/chem.201101658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53**.Cao ZH, Tong R, Mishra A, Xu WC, Wong GCL, Cheng JJ, Lu Y. Reversible Cell-Specific Drug Delivery with Aptamer-Functionalized Liposomes. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2009;48:6494–6498. doi: 10.1002/anie.200901452. Demonstration of targeted delivery of cisplatin to MCF-7 breast cancer cells through nucleolin aptamer functionalized liposomes. A complementary DNA of the aptamer was used as an antidote. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54**.Wu YR, Sefah K, Liu HP, Wang RW, Tan WH. DNA aptamer-micelle as an efficient detection/delivery vehicle toward cancer cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:5–10. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0909611107. A novel aptamer obtained from in vitro selection combined with micelle was found to exhibit specificity to Ramos cells. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yu CC, Hu Y, Duan JH, Yuan W, Wang C, Xu HY, Yang XD. Novel Aptamer-Nanoparticle Bioconjugates Enhances Delivery of Anticancer Drug to MUC1-Positive Cancer Cells In Vitro. PLoS One. 2011:6. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0024077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56**.Chang M, Yang CS, Huang DM. Aptamer-Conjugated DNA Icosahedral Nanoparticles As a Carrier of Doxorubicin for Cancer Therapy. ACS Nano. 2011;5:6156–6163. doi: 10.1021/nn200693a. Demonstration of aptamer-conjugated 3D DNA icosahedra for doxorubicin encasulation and specific intracellular delivery to epithelial cancer cells. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hu SH, Gao XH. Nanocomposites with Spatially Separated Functionalities for Combined Imaging and Magnetolytic Therapy. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:7234–7237. doi: 10.1021/ja102489q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Xing H, Wang Z, Xu Z, Wong NY, Xiang Y, Liu GL, Lu Y. DNA-Directed Assembly of Asymmetric Nanoclusters Using Janus Nanoparticles. ACS Nano. 2011;6:802–809. doi: 10.1021/nn2042797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Jaschke A. Artificial ribozymes and deoxyribozymes. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2001;11:321–326. doi: 10.1016/s0959-440x(00)00208-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]