Abstract

Major depressive disorder (MDD) is common and costly. Primary care remains a major access point for depression treatment, yet the successful clinical resolution of depression in primary care is uncommon. The clinical response to depression suffers from a “treatment cascade”: the affected individual must access health care, be recognized clinically, initiate treatment, receive adequate treatment, and respond to treatment. Major gaps currently exist in primary care at each step along this treatment continuum. We estimate that 12.5% of primary care patients have had MDD in the past year; of those with MDD, 47% are recognized clinically, 24% receive any treatment, 9% receive adequate treatment, and 6% achieve remission. Simulations suggest that only by targeting multiple steps along the depression treatment continuum (e.g. routine screening combined with collaborative care models to support initiation and maintenance of evidence-based depression treatment) can overall remission rates for primary care patients be substantially improved.

Keywords: Major depressive disorder, Depression treatment cascade, Recognition, Treatment, Remission, Primary care, Public health

Introduction

Major depressive disorder (MDD) is common and costly. Over the course of a year, between 13.1 and 14.2 million people will experience MDD.[1] By 2030, depression itself is projected to be the single leading cause of overall disease burden in high-income countries. Worldwide, depression makes a large contribution to the burden of disease, ranking third worldwide, eighth in low-income countries, and first in middle- and high-income countries.[2] In 2000, the U.S. economic burden of depressive disorders was estimated to be $83.1 billion; nearly 1/3 of these costs are attributable to direct medical expenses.[3] Projected depression-related workforce productivity losses are $24 billion annually.[4]

Primary care remains a major access point for depression treatment. Primary care practitioners manage approximately one third to one half of non-elderly adults[1,5] and nearly two thirds of older adults[6] who receive treatment for MDD. The severity of depressive symptoms in patients receiving treatment in primary care is equivalent to that of patients treated in psychiatric settings.[7,8] Indeed, the World Health Organization has identified the “urgent importance” of integrating mental health into primary care as the most salient means of addressing the global burden of mental health conditions.[9]

Yet, despite advances in depression management that are directly relevant to primary care, including the availability of a wider range of antidepressants with greater tolerability than earlier medications[10] and the effectiveness and feasibility of evidence-based collaborative[11] and measurement-based care strategies[12] in primary care settings, the successful clinical resolution of depression in primary care practice is uncommon. As with other chronic illnesses,[13] the clinical response to depression suffers from a “treatment cascade”: for a depressive disorder to be successfully treated clinically, the affected individual must enter the health care system, be recognized clinically, initiate treatment, receive adequate treatment, and respond to treatment. Major gaps currently exist in primary care at each step along this treatment continuum, with the result that at the population level, the vast majority of patients with depressive disorders remain untreated or ineffectively treated.

Our purpose in this paper is to quantify the “depression treatment cascade” – the cumulative shortfalls in clinical recognition, initiation of treatment, adequacy of treatment, and treatment response for depressed patients in primary care. We will examine key current debates relevant to the depression treatment cascade and review options for improving the population-level treatment of depression in primary care.

The Depression Treatment Cascade

The steps required for successful depression treatment lie along a treatment continuum or cascade (Figure 1). Here we review the literature regarding the prevalence of depression in the general population, the proportion of prevalent cases in primary care that are recognized clinically, the proportion of clinically recognized cases that are treated, the proportion of treated cases that receive adequate treatment, and the proportion of adequately treated cases that achieve depression remission.

Figure 1.

The depression treatment continuum.

Prevalence

Estimates of the prevalence of depression vary depending on population, measure, and time frame. A 2005 study using data from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions, in which face-to-face surveys of >43,000 US adults (age 18+) were conducted, estimated the 12-month prevalence of major depressive disorder (MDD) as 5.3% and the lifetime prevalence as 13.2%, using the Alcohol Use Disorder and Associated Disabilities Interview Schedule–DSM-IV Version (AUDADIS-IV) from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism to identify MDD.[14]The Joint Canada/United States Survey of Health, which conducted >5,000 telephone interviews of US adults in 2007, reported a slightly higher 12-month MDD prevalence estimate of 8.7% based on the criteria of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV).[15]The National Co-morbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R), which used the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI) depression screener during face-to-face household surveys conducted from 2001-2002, estimated a 12-month MDD prevalence of 6.6% and lifetime prevalence of 16.2%.[1] However, not all patients with major depression in the general population will seek medical care. A meta-analysis of 8 US studies of depression in primary care reported a pooled estimate for current MDD of 12.5% (95% CI: 7.4-18.7%) based on structured gold-standard assessments.[16]

Clinical recognition

While depression is common among the general population, its clinical recognition is less common. A recent meta-analysis of 118 studies including over 50,000 patients estimated that general practitioners correctly identify depression 47% of the time.[17]

Initiation of treatment

When depression is recognized clinically, it often goes untreated indefinitely or for a prolonged period of time after diagnosis. Data from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R) that included >9,000 participants, found that the vast majority of lifetime major depression cases eventually initiate treatment, but that delays in treatment initiation can be excessive.[18] They projected that 88% of those with lifetime major depressive episodes (MDE) initiated treatment at some point after onset, but that only 37% did so within a year of depression onset; median duration of delay was eight years. In a separate 2005 study using the same NCS-R data, 57% of those with a major depressive episode (MDE) in the past year used any mental health services during that year.[19]

Adequacy of treatment

Of those receiving “any” mental health treatment, only a subset are likely receiving adequate treatment. Adequate treatment for psychotherapeutic treatments generally requires at least 8 sessions.[1] For pharmacological management of depression, a core principle involves regular evaluation of depressive symptom response and side effects, combined with increasing antidepressant doses if response has not been achieved.[20,21] Further, an adequate medication trial implies a reasonable dose and duration for the treatment, often described as at least a moderate dose for at least 6-8 weeks.[22]

Based on NCS-R data for the US general population, 64% of those being treated in the specialty mental health sector and 41% of those being treated in the general medical sector receive “adequate” depression treatment. This study defined “adequate depression treatment” as receiving at least 8 psychotherapy visits or at least 4 medication monitoring visits in the prior year.[1] This definition is likely to produce a generous estimate of adequacy of pharmacological treatment, since number of appointments does not indicate whether doses were adjusted based on the patient’s response to treatment. In the study mentioned in the previous section, Wang, et al found that of those with past-year MDE who utilized any services in the past year, the median number of visits was 5.5. They determined that 38% were receiving “minimally adequate treatment,” which they defined as pharmacotherapy for at least 2 months plus more than 4 visits to any physician; or at least 8 psychotherapy visits of 30 minutes or more to any provider.[19]

Treatment response

Even among those receiving adequate and closely monitored treatment with psychotherapy or antidepressants, not all patients achieve full treatment response. In depression treatment, full response, or remission, is defined as complete resolution of depressive symptoms and a full return of functioning,[23] usually defined as achieving a score <8 on the standardized Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HRSD). In STAR*D, a study of over 4,000 patients that defined the relative benefit of different depression treatment strategies for a “real world” clinical population with multiple medical and psychiatric comorbidities, approximately one-third of participants achieved remission after 12 weeks of treatment with a first antidepressant and approximately two-thirds achieved remission after up to three depression treatment strategies.[22]

Summary

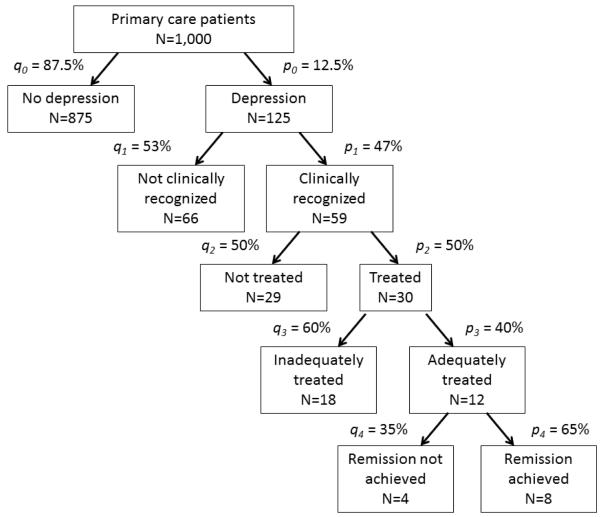

Based on the above review, we posit the following summary estimates, with 95% Bayesian credible intervals (BCI),[24] to define the depression treatment cascade (Figure 2). Based on the heterogeneity of the source data, these summary estimates and BCIs are not formal meta-analytic pooled estimates but represent our qualitative summary of the central tendency and uncertainty for each parameter.

Figure 2. Recognition, treatment, and remission of depression in primary care.

This figure estimates, in a hypothetical population of 1,000 primary care patients, the estimated number with depression, with clinically recognized depression, with treated depression, with adequately treated depression, and with remitted depression.

For the prevalence of past-year MDD (p0), weighting most heavily the Mitchell et al. meta-analysis, we propose a summary estimate of 12.5% with a 95% BCI of 7-19%.

For the proportion with a clinically recognized diagnosis among all those with a diagnosis (p1), relying on the large meta-analysis, we propose a summary estimate of 47% with a relatively narrow 95% BCI of 42-53%.

For the proportion receiving any treatment among those with a recognized diagnosis (p2), we propose a summary estimate of 50% with a broader 95% BCI of 33-67%, noting the wider divergence between the reviewed estimates.

For the proportion receiving adequate treatment among those receiving any treatment (p3), we propose a summary estimate of 40% with a 95% BCI of 30-50%, reflecting estimates from general medical settings in the NCS-R, noting that this is likely to be a generous estimate of adequacy.

For the proportion achieving remission among those receiving adequate treatment (p4), we propose a summary estimate of 65% with a 95% BCI of 50-80%, reflecting the results of the STAR*D trial.

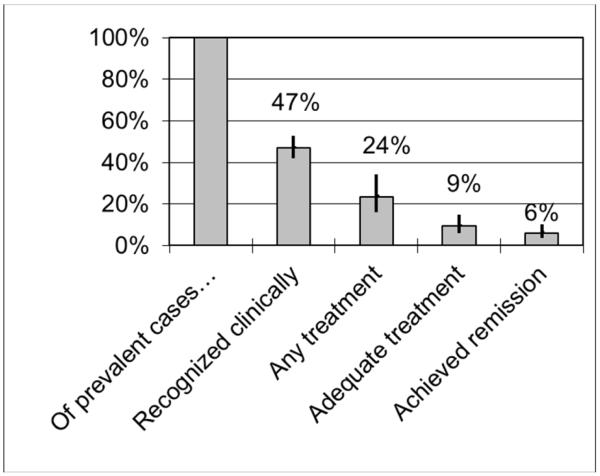

Combining these estimates, we estimate that of all primary care patients with past-year MDD, 47% (95% BCI: 42-53%) are recognized clinically, 24% (16-34%) are receiving any treatment, 9% (6-15%) are receiving adequate treatment, and 6% (4-10%) have achieved remission (Figure 3). In other words, we estimate that 76% of primary care patients with depression are not receiving any treatment, 91% are not receiving adequate treatment, and 94% have not achieved remission. The methodology of constructing the summary BCIs is presented in Figure 4.

Figure 3. The Depression Treatment Cascade.

The figure depicts, of all primary care patients with a major depressive episode in the past year, the estimated proportion recognized clinically, receiving any treatment, receiving adequate treatment, and achieving remission. The bars represent point estimates and the vertical lines indicate 95% Bayesian credible intervals (Figure 4).[24]

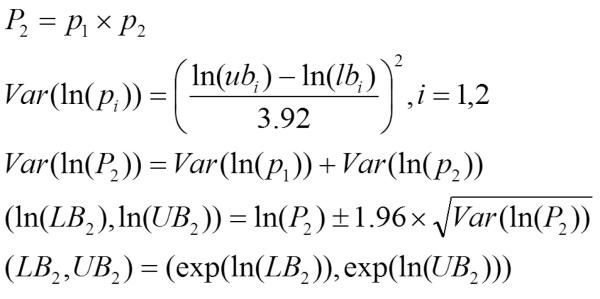

Figure 4. Calculation of 95% Bayesian Credible Intervals for estimates in the depression treatment cascade.

To place cumulative 95% Bayesian credible intervals (BCI)[24] around the cascade estimates shown in Figure 3, we transformed each individual estimate (p1–p4) and BCI onto the log scale, calculated the implied variance of each transformed estimate from its transformed BCI, calculated the variance of each cumulative estimate on the log scale as the sum of the variances for each component individual transformed estimate, used this variance to calculate a 95% BCI on the log scale of the cumulative estimate, and exponentiated the result to translate the BCI back onto the original percentage scale. For example, in the formulas above, let p1 be the proportion of those with a depressive disorder that are recognized clinically, and p2 be the proportion of those recognized clinically receiving any treatment (Figure 2). Let (lb1, ub1) and (lb2, ub2) be the 95% BCIs around p1 and p2 respectively. Finally, let P2 = the proportion of those with a depressive disorder receiving any treatment, and (LB2, UB2) be its 95% BCI.

Improving Population-Level Remission

Figure 3 demonstrates that multiple large gaps impede the effective clinical resolution of depression in primary care patients. With the combination of low clinical recognition of depression, failure to initiate depression treatment, inadequate depression treatment, and depression treatment failure, 15 out of 16 primary care patients with depression continue to have unresolved depressive symptoms.

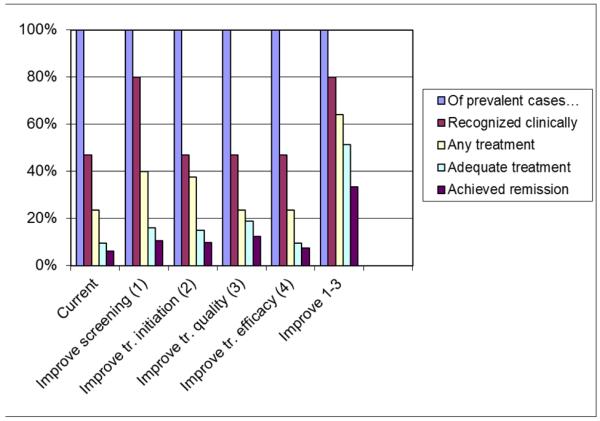

Figure 5 illustrates the hypothetical impact of different types of interventions to try to improve population-level depression remission rates. Interventions singly focused on increasing clinical recognition through screening (1), increasing treatment initiation (2), and improving adequacy of treatment (3), with each achieving a hypothetical 80% success rate in its target indicator, would all modestly increase overall remission rates. Based on the model, improving adequacy of treatment to 80% would have the largest single impact, doubling remission rates to 12%. Given that our model reflects a fairly generous definition of adequacy, this is likely to be an underestimate of the actual gains achievable by focusing on improving adequacy. Efforts to develop more efficacious treatments (4) would have marginal impact on remission rates. However, substantial gains in depression remission rates could only be achieved by targeting multiple gaps. An intervention that increased clinical recognition, treatment initiation, and treatment adequacy (1-3) all to 80% would increase remission rates from 6% to 33%.

Figure 5. The hypothetical impact of various strategies to increase depression remission rates.

The first set of bars reflects current conditions. The next four sets of bars each reflect the impact of a single change to current conditions. In (1), improvements in screening increase clinical recognition rates to 80%. In (2), depression treatment is initiated in 80% of those recognized. In (3), treatment quality is improved, with 80% of those initiating treatment now receiving best-practices treatment. In (4), new treatments are developed with 80% efficacy. The final set of bars shows the impact of achieving (1), (2), and (3) simultaneously.

Achieving such an improvement on multiple fronts would likely require service delivery changes in primary care. Such an effort might include routine screening for depression linked to confirmatory assessments for those with positive depression screens and collaborative care approaches to ensuring timely initiation and adequacy of depression treatment. Such collaborative care and algorithmic decision support approaches for delivering high-quality depression treatment in non-psychiatric settings, including primary and chronic medical care, have proven both efficacious and effective.[22,25-27]

To screen or not to screen

The preceding analysis suggests that clinical under-recognition of depression presents a major barrier to improving depression remission rates at the population level. Indeed, systematic review evidence[28] led the United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) in 2009 to recommend screening adults for depression in practices with systems to ensure accurate diagnosis, effective treatment, and appropriate follow-up.[29] However, others have argued that there is no evidence that screening per se improves mental health outcomes for patients and that depression screening programs carry risks that are not justified by the uncertain benefits.[30] Here we review the arguments that have been put forward in favor of and against routine depression screening programs in general-population primary care practices.

In favor

Support for routine depression screening is mainly based on evidence that such screening, when combined with the proper follow-up care, can improve depression outcomes. O’Connor, et al addressed the question of whether or not to screen for depression in primary care by examining evidence for the guidelines used by the USPSTF in making its screening recommendation.[28] They assessed 1) whether there was evidence that screening reduces morbidity and/or mortality; 2) the effect of clinician feedback of screening test results on depression response and remission; and 3) adverse effects of antidepressant treatment for depression. Several studies have reported that screening programs combined with staff support in depression care achieve important improvements in depressive symptoms relative to usual care.[31-38] Antidepressants were found to be tolerated by most patients.[39-46] O’Connor and colleagues identified no evidence of harm from screening programs, and concluded that screening programs are effective when staff members other than primary care providers provide some of the depression care, or when patients are enrolled in specialty mental health care. They noted, however, that evidence does not show any benefit from screening programs not linked to treatment.

Against

The majority of arguments against routine screening posit that the benefits gained through screening do not outweigh its potential harms.[30] For example, Gilbody, et al[47] conducted a meta-analysis of 11 studies and found no reduction in depression prevalence or improvement of depressive symptoms due to depression screening. Thombs and colleagues[30] noted that while the four studies upon which the USPSTF recommendation was based all found improved outcomes among depressed patients after staff-assisted depression management programs, none of them actually evaluated depression screening. Thombs and colleagues also cited rising rates of antidepressant prescriptions as evidence that depression is already being adequately diagnosed. Potential disadvantages to screening include large numbers of false positives,[48,49] with the potential “nocebo” effect of causing a patient to develop depressive symptoms by labeling him with a false diagnosis, and the lower efficacy of depression treatment for patients with less severe depression.[50,51] Thombs and colleagues conclude that there is no clearly demonstrated evidence of benefit from the resource-intensive process of depression screening, and given the potential unintended negative effects of screening, it should not be recommended in primary care.

Implications of unresolved depression for chronic medical conditions

The public health importance of improved strategies to successfully treat depression derives not only from the burden of depression itself, but also from the intersection of depression with many of the chronic medical conditions of major public health importance. Depression is over-represented in most chronically ill populations relative to the general population, including patients with diabetes, cardiovascular disease, chronic kidney disease, and HIV infection.[52-55] Across these conditions, as with the general primary care patient population, depression is consistently under-diagnosed and under-treated.[56,57] Also across these conditions, depression is consistently associated with poorer engagement in chronic medical care, poorer adherence to chronic medical treatment regimens, and worse clinical outcomes.[27,58-63] While collaborative care approaches that link mental health and medical treatment teams have demonstrated some success in improving depressive and medical outcomes in primary care and comorbid patients,[22,25,27] such approaches are not yet widespread.

Conclusion

MDD remains an important but challenging management issue in primary care. Reasonably effective treatments exist, but shortfalls at multiple steps along the treatment delivery pathway suggest that only 9% of depressed primary care patients receive adequate treatment, and only 6% reach remission. This public health perspective helps highlight priorities that can usefully guide both research and policy choices. For example, if one wanted to focus on making the single system-level change that would produce the largest improvement in attainment of remission rates, one would put efforts into improving the adequacy of depression treatment, which could double remission rates to 12% (i.e., successfully treating 1 of 8 patients). However, the model suggests that meaningful gains can likely only be reached by targeting multiple steps along the spectrum of depression diagnosis and care —by improving depression recognition, treatment initiation, and treatment adequacy, remission rates could increase from an estimated 6% to 33% (i.e., successfully treating 1 of 3 patients).

The public health perspective provides a framework for addressing the challenge of effective depression treatment in primary care. From a policy viewpoint, the approach suggests that comprehensive, feasible approaches, like collaborative care[27] and measurement based-care,[64]which support care systems in initiating and maintaining high-quality evidence-based depression treatment, could help guide primary care physicians to more proactively and vigorously manage depression in primary care. An individual clinic might adopt as a first step a policy of periodically screening all patients to help define the prevalence of depression in the patient population. Alternatively, a clinic that is already comfortable with its ability to identify and initiate treatment for depression might focus efforts on improving the quality of treatment through a closer monitoring and management approach. Ultimately, a combination of system-level enhancements to the identification and treatment of depression is likely to be necessary to meaningfully improve depression outcomes and quality of life among primary care patients.

Acknowledgments

BWP and BNG’s contribution to this paper was supported by grant R01MH086362 of the National Institute of Mental Health, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA. BWP is an investigator with the Implementation Research Institute (IRI), at the George Warren Brown School of Social Work, Washington University in St. Louis; through an award from the National Institute of Mental Health (R25 MH080916-01A2) and the Department of Veterans Affairs, Health Services Research & Development Service, Quality Enhancement Research Initiative (QUERI). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIMH or the NIH.

Footnotes

Disclosure Dr. Pence has received research support from National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) and received honoraria and research support from National Institutes of Health (NIH).

Dr. O’Donnell reported no potential conflicts of interest relevant to this article.

Dr. Gaynes has received research support from Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRC), NIMH, and NIH; has served as a consultant for Bristol-Myers Squibb; and has received payment for development of educational presentations from MedScape.

References

Recently published papers of particular interest have been highlighted as:

• Of importance

- 1.Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, et al. The epidemiology of major depressive disorder: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R) JAMA. 2003 Jun 18;289(23):3095–3105. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.23.3095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization [Accessed October 25, 2010];The global burden of disease: 2004 update. 2004 http://www.who.int/healthinfo/global_burden_disease/2004_report_update/en/index.html.

- 3.Greenberg PE, Kessler RC, Birnbaum HG, et al. The economic burden of depression in the United States: how did it change between 1990 and 2000? J Clin Psychiatry. 2003 Dec;64(12):1465–1475. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v64n1211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Birnbaum HG, Ben-Hamadi R, Greenberg PE, et al. Determinants of direct cost differences among US employees with major depressive disorders using antidepressants. PharmacoEconomics. 2009;27(6):507–517. doi: 10.2165/00019053-200927060-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pincus H, Tanielian T, Marcus S, et al. Prescribing trends in psychotropic medications: primary care, psychiatry, and other medical specialities. JAMA. 1998;279(7):526–531. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.7.526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Harman JS, Veazie PJ, Lyness JM. Primary care physician office visits for depression by older Americans. Journal of general internal medicine. 2006 Sep;21(9):926–930. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00497.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gaynes BN, Rush AJ, Trivedi M, et al. A direct comparison of presenting characteristics of depressed outpatients from primary vs. specialty care settings: preliminary findings from the STAR*D clinical trial. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2005;27(2):87–96. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2004.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gaynes BN, Rush AJ, Trivedi MH, et al. Major Depression Symptoms in Primary Care and Psychiatric Care Settings: A Cross-Sectional Analysis. Ann Fam Med. 2007;5(2):126–134. doi: 10.1370/afm.641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.World Health Organization The global burden of disease: 2004 update. 2004 http://www.who.int/healthinfo/global_burden_disease/2004_report_update/en/index.html.

- 10.Gartlehner G, Hansen RA, Morgan LC, et al. Comparative benefits and harms of second-generation antidepressants for treating major depressive disorder: an updated meta-analysis. Annals of internal medicine. 2011 Dec 6;155(11):772–785. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-155-11-201112060-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11•.Katon WJ, Lin EH, Von Korff M, et al. Collaborative care for patients with depression and chronic illnesses. N Engl J Med. 2011 Dec 30;363(27):2611–2620. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1003955. This randomized controlled trial of a collaborative care treatment model for depression and chronic medical conditions demonstrated improvements in clinical indicators of cardiovascular disease and diabetes in the intervention arm relative to usual care.

- 12.Trivedi MH, Rush AJ, Gaynes BN, et al. Maximizing the Adequacy of Medication Treatment in Controlled Trials and Clinical Practice: STAR*D Measurement-Based Care. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2007;32:2479–2489. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mugavero MJ. Guidelines for improving HIV treatment “adherence”: The big picture. 6th International Conference on HIV Treatment and Prevention Adherence; Miami, FL. 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hasin DS, Goodwin RD, Stinson FS, Grant BF. Epidemiology of major depressive disorder: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcoholism and Related Conditions. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005 Oct;62(10):1097–1106. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.10.1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vasiliadis HM, Lesage A, Adair C, et al. Do Canada and the United States differ in prevalence of depression and utilization of services? Psychiatr Serv. 2007 Jan;58(1):63–71. doi: 10.1176/ps.2007.58.1.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16•.Mitchell AJ, Rao S, Vaze A. International comparison of clinicians’ ability to identify depression in primary care: meta-analysis and meta-regression of predictors. Br J Gen Pract. 2011;61(583):e72–80. doi: 10.3399/bjgp11X556227. This meta-analysis compares the prevalence of depression in primary care practices across countries as well as primary care providers’ ability to identify depression.

- 17.Mitchell AJ, Vaze A, Rao S. Clinical diagnosis of depression in primary care: a meta-analysis. Lancet. 2009 Aug 22;374(9690):609–619. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60879-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang PS, Berglund P, Olfson M, et al. Failure and delay in initial treatment contact after first onset of mental disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005 Jun;62(6):603–613. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang PS, Lane M, Olfson M, et al. Twelve-month use of mental health services in the United States: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005 Jun;62(6):629–640. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.American Psychiatric Association . Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients With Major Depressive Disorder. Third Ed American Psychiatric Association Press; Washington, DC: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Agency for Health Care Policy and Research . Depression in Primary Care: Vol 2: Treatment of Major Depression. US Dept of Health and Human Services; Rockville, MD: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gaynes BN, Warden D, Trivedi MH, et al. What did STAR*D teach us? Results from a large-scale, practical, clinical trial for patients with depression. Psychiatr Serv. 2009 Nov;60(11):1439–1445. doi: 10.1176/ps.2009.60.11.1439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rush AJ, Kraemer HC, Sackeim HA, et al. Report by the ACNP Task Force on response and remission in major depressive disorder. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2006 Sep;31(9):1841–1853. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Carlin BP, Louis TA. Bayesian Methods for Data Analysis. 3rd ed Chapman and Hall/CRC Press; Boca Raton: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Katon WJ, Von Korff M, Lin EH, et al. The Pathways Study: a randomized trial of collaborative care in patients with diabetes and depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004;61(10):1042–1049. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.10.1042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26•.Pyne JM, Fortney JC, Curran GM, et al. Effectiveness of collaborative care for depression in human immunodeficiency virus clinics. Arch Intern Med. 2011 Jan 10;171(1):23–31. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2010.395. This randomized controlled trial of a collaborative care treatment model for depression and HIV in VA facilities (the HITIDES intervention) demonstrated improvements in depression and HIV-related symptomatology but not HIV medication adherence.

- 27.Katon WJ, Lin EH, Von Korff M, et al. Collaborative care for patients with depression and chronic illnesses. N Engl J Med. 2010 Dec 30;363(27):2611–2620. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1003955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28•.O’Connor EA, Whitlock EP, Beil TL, Gaynes BN. Screening for depression in adult patients in primary care settings: a systematic evidence review. Ann Intern Med. 2009 Dec 1;151(11):793–803. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-151-11-200912010-00007. This review argues in favor of routine screening for depression in primary care settings.

- 29.Screening for depression in adults: U.S. preventive services task force recommendation statement. Annals of internal medicine. 2009 Dec 1;151(11):784–792. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-151-11-200912010-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30•.Thombs BD, Coyne JC, Cuijpers P, et al. Rethinking recommendations for screening for depression in primary care. Cmaj. 2009 Sep 19; doi: 10.1503/cmaj.111035. This review identifies concerns with routine screening for depression in primary care.

- 31.Rost K, Nutting P, Smith J, et al. Improving depression outcomes in community primary care practice: a randomized trial of the quEST intervention. Quality Enhancement by Strategic Teaming. J Gen Intern Med. 2001 Mar;16(3):143–149. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2001.00537.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wells KB, Sherbourne C, Schoenbaum M, et al. Impact of disseminating quality improvement programs for depression in managed primary care: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2000 Jan 12;283(2):212–220. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.2.212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Whooley MA, Stone B, Soghikian K. Randomized trial of case-finding for depression in elderly primary care patients. J Gen Intern Med. 2000 May;15(5):293–300. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2000.04319.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Callahan CM, Hendrie HC, Dittus RS, et al. Improving treatment of late life depression in primary care: a randomized clinical trial. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1994 Aug;42(8):839–846. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1994.tb06555.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bergus GR, Hartz AJ, Noyes R, Jr., et al. The limited effect of screening for depressive symptoms with the PHQ-9 in rural family practices. J Rural Health. 2005 Fall;21(4):303–309. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-0361.2005.tb00099.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jarjoura D, Polen A, Baum E, et al. Effectiveness of screening and treatment for depression in ambulatory indigent patients. J Gen Intern Med. 2004 Jan;19(1):78–84. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2004.21249.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bosmans J, de Bruijne M, van Hout H, et al. Cost-effectiveness of a disease management program for major depression in elderly primary care patients. J Gen Intern Med. 2006 Oct;21(10):1020–1026. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00555.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rubenstein LZ, Alessi CA, Josephson KR, et al. A randomized trial of a screening, case finding, and referral system for older veterans in primary care. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007 Feb;55(2):166–174. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01044.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Anderson IM. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors versus tricyclic antidepressants: a meta-analysis of efficacy and tolerability. Journal of affective disorders. 2000 Apr;58(1):19–36. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(99)00092-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Arroll B, Macgillivray S, Ogston S, et al. Efficacy and tolerability of tricyclic antidepressants and SSRIs compared with placebo for treatment of depression in primary care: a meta-analysis. Ann Fam Med. 2005 Sep-Oct;3(5):449–456. doi: 10.1370/afm.349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Beasley CM, Jr., Nilsson ME, Koke SC, Gonzales JS. Efficacy, adverse events, and treatment discontinuations in fluoxetine clinical studies of major depression: a meta-analysis of the 20-mg/day dose. J Clin Psychiatry. 2000 Oct;61(10):722–728. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v61n1003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gartlehner G, Hansen RA, Thieda P, et al. Comparative Effectiveness of Second-Generation Antidepressants in the Pharmacologic Treatment of Adult Depression. Rockville (MD): 2007. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.MacGillivray S, Arroll B, Hatcher S, et al. Efficacy and tolerability of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors compared with tricyclic antidepressants in depression treated in primary care: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2003 May 10;326(7397):1014. doi: 10.1136/bmj.326.7397.1014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mottram P, Wilson K, Strobl J. Antidepressants for depressed elderly. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;(1) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003491.pub2. CD003491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mulrow CD, Williams JW, Jr., Chiquette E, et al. Efficacy of newer medications for treating depression in primary care patients. Am J Med. 2000 Jan;108(1):54–64. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(99)00316-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Williams JW, Jr., Mulrow CD, Chiquette E, et al. A systematic review of newer pharmacotherapies for depression in adults: evidence report summary. Annals of internal medicine. 2000 May 2;132(9):743–756. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-132-9-200005020-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gilbody S, Bower P, Fletcher J, et al. Collaborative care for depression: a cumulative meta-analysis and review of longer-term outcomes. Arch Intern Med. 2006 Nov 27;166(21):2314–2321. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.21.2314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mitchell AJ. Clinical utility of screening for clinical depression and bipolar disorder. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2012 Jan;25(1):24–31. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0b013e32834de45b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Williams JW, Jr., Pignone M, Ramirez G, Stellato C Perez. Identifying depression in primary care: a literature synthesis of case-finding instruments. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2002 Jul-Aug;24(4):225–237. doi: 10.1016/s0163-8343(02)00195-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Benedetti F, Lanotte M, Lopiano L, Colloca L. When words are painful: unraveling the mechanisms of the nocebo effect. Neuroscience. 2007 Jun 29;147(2):260–271. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2007.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mora MS, Nestoriuc Y, Rief W. Lessons learned from placebo groups in antidepressant trials. Philosophical transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological sciences. 2011 Jun 27;366(1572):1879–1888. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2010.0394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bing EG, Burnam MA, Longshore D, et al. Psychiatric disorders and drug use among human immunodeficiency virus-infected adults in the United States. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2001 Aug;58(8):721–728. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.58.8.721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Anderson RJ, Freedland KE, Clouse RE, Lustman PJ. The prevalence of comorbid depression in adults with diabetes: a meta-analysis. Diabetes care. 2001 Jun;24(6):1069–1078. doi: 10.2337/diacare.24.6.1069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hedayati SS, Minhajuddin AT, Toto RD, et al. Prevalence of major depressive episode in CKD. Am J Kidney Dis. 2009 Sep;54(3):424–432. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2009.03.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lippi G, Montagnana M, Favaloro EJ, Franchini M. Mental depression and cardiovascular disease: a multifaceted, bidirectional association. Semin Thromb Hemost. 2009 Apr;35(3):325–336. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1222611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Asch SM, Kilbourne AM, Gifford AL, et al. Underdiagnosis of depression in HIV: who are we missing? J Gen Intern Med. 2003 Jun;18(6):450–460. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2003.20938.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Katon WJ, Simon G, Russo J, et al. Quality of depression care in a population-based sample of patients with diabetes and major depression. Medical care. 2004 Dec;42(12):1222–1229. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200412000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hedayati SS, Minhajuddin AT, Afshar M, et al. Association between major depressive episodes in patients with chronic kidney disease and initiation of dialysis, hospitalization, or death. JAMA. 2010 May 19;303(19):1946–1953. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Mugavero M, Ostermann J, Whetten K, et al. Barriers to antiretroviral adherence: the importance of depression, abuse, and other traumatic events. AIDS patient care and STDs. 2006 Jun;20(6):418–428. doi: 10.1089/apc.2006.20.418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Leserman J. Role of depression, stress, and trauma in HIV disease progression. Psychosom Med. 2008 Jun;70(5):539–545. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3181777a5f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.de Groot M, Anderson R, Freedland KE, et al. Association of depression and diabetes complications: a meta-analysis. Psychosom Med. 2001 Jul-Aug;63(4):619–630. doi: 10.1097/00006842-200107000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lustman PJ, Anderson RJ, Freedland KE, et al. Depression and poor glycemic control: a meta-analytic review of the literature. Diabetes care. 2000 Jul;23(7):934–942. doi: 10.2337/diacare.23.7.934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Bush DE, Ziegelstein RC, Patel UV, et al. Post-myocardial infarction depression. Evid Rep Technol Assess (Summ) 2005 May;(123):1–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Gaynes BN, Rush AJ, Trivedi MH, et al. Primary versus specialty care outcomes for depressed outpatients managed with measurement-based care: results from STAR*D. J Gen Intern Med. 2008 May;23(5):551–560. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0522-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]