Abstract

Background:

A stethoscope, an essential tool of the medical profession, can become a source of nosocomial infection.

Objective:

To determine the frequency of bacterial contamination of stethoscopes as well as the practices used for cleaning them.

Methods:

Cultures were taken from 100 stethoscopes used by different medical personnel in different hospital services. The stethoscopes were collected while the staff filled in a questionnaire.

Results:

Thirty (30%) out of the 100 stethoscopes surveyed were contaminated with microorganisms. The majority of organisms isolated were gram-positive bacteria (gram positive bacilli 12%, gram-negative bacteria 9%, gram-positive cocci 9%). None of the stethoscopes grew methicillin-resistant staphylococcus aureus. Overall, 21% of the health personnel cleaned their stethoscopes daily, 47% weekly, and 32% yearly. None of the health care workers cleaned their stethoscopes after every patient. Nurses cleaned their stethoscopes more often than physicians and medical students.

Conclusion:

Stethoscopes may be important in the spread of infectious agents. Their regular disinfection after use on each patient should be considered, particularly in such areas of the hospital, as the critical care units, and oncology units which house many patients with antibiotic-resistant organisms.

Keywords: Stethoscope, Contamination, Saudi Arabia

INTRODUCTION

Nosocomial infection has been recognized for over a century as both a critical problem affecting the quality of health care and a leading cause of morbidity, mortality and increased health care cost.1 Stethoscopes are essential tools of the medical profession and because of their universal use might be a source of microorganisms that cause nosocomial infections. Stethoscopes come in direct contact with numerous patients daily and their disinfection after each use is not an established practice.

Several studies in medical literature have demonstrated that many physicians’ stethoscopes are contaminated with pathogenic bacteria and could serve as a mode for transmission of infection.2–4 This phenomenon may be a particular problem in areas where the outbreak of multidrug resistant bacteria, such as, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), occurs or where patients with increased susceptibility to infection are to be found. We evaluated the problem by surveying the current practice of stethoscope hygiene among health care professionals and screened their stethoscopes for microorganisms during an outbreak of MRSA.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

King Fahd Hospital of the University is a 440-bed, primary–through-tertiary care hospital located in the Eastern Province of Saudi Arabia. During a campaign to educate health care workers on the sources of MRSA, swabs were randomly taken from 100 stethoscopes used by different medical personnel in different hospital services. Stethoscopes were collected while the staff completed a simple self explanatory questionnaire which explored the category of the health personnel, and the frequency of cleaning their stethoscopes (never, once a year, once a week, daily or after each patient). Cultures from stethoscopes were obtained by swabbing the diaphragm and the bell of the stethoscope with a sterile swab moistened with saline. These swabs were immediately streaked onto blood agar plates and incubated in air at 37°C for 48 hours. Cultures were identified by colony morphologic characteristics, Gram stain characteristics, and standardized microbiological biochemical tests.

RESULTS

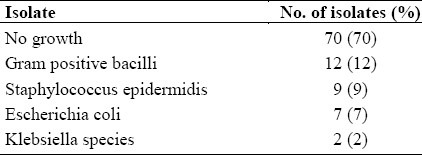

A total of 100 stethoscopes were examined. The types of bacteria isolated from the stethoscopes are summarized in Table 1. There was, as expected, a predominance of microorganisms commonly found as cutaneous flora. Several other potentially pathogenic microorganisms were also isolated. These include Escherichia coli and Klebsiella species. No methicillin-resistant staphylococci were isolated.

Table 1.

Results of cultures from 100 stethoscopes

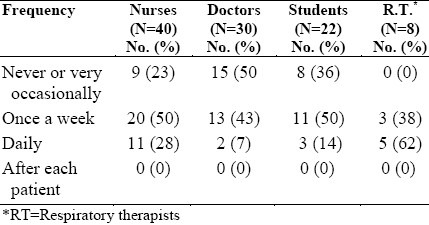

The frequency of cleaning of stethoscope by the staff is shown in Table 2. Nurses and respiratory therapists cleaned their stethoscopes more often than doctors or medical students. None of the health personnel cleaned their stethoscopes after each patient.

Table 2.

Frequency of cleaning stethoscopes among 100 health care personnel

DISCUSSION

Health care workers are a potential source of nosocomial infections. Many endemic pathogens are transmitted through hand carriage, and since the time of Semmelweis, hand washing has been repeatedly shown to reduce the risk of nosocomial infections.5,6 However, transmission of infection through medical devices is also well documented. Outbreaks of nosocomial infections attributed to electronic thermometers,7 blood pressure cuffs,8 and latex gloves9 have been reported. Several studies have investigated the presence of pathogenic bacteria on stethoscopes as a source of infection.2–4

The results of our study demonstrate that stethoscopes that are utilized in clinical practice on a daily basis carry potentially pathogenic microorganisms. Since normal skin flora consists primarily of gram-positive bacteria, it is not surprising that fewer gram-negative bacteria were isolated. The frequency of contamination of stethoscopes observed in this study is lower than the 70% to 100% reported in the literature.2–4

Coagulase negative staphylococcus is a microorganism which frequently causes severe systemic infections, including catheter-associated and device-associated sepsis. Intact skin is an efficient barrier against most infective agents. However, small skin lesions are frequent and this route of exposure should not be underestimated. This is extremely important when treating patients with wounds or burns, or patients with catheters or tracheostomies.

In our study, only 21% of the respondents regularly cleaned their stethoscopes. Nurses cleaned their stethoscopes more frequently than physicians and medical students. None of the health care workers cleaned their stethoscopes after use in every patient. Isopropyl alcohol has been shown to reduce bacterial colony counts when applied to the stethoscope diaphragm.3 Regular disinfection of stethoscopes or disposable cover should be used to minimize the possibility of spreading infectious agents in hospitalized patients. This is especially important today, since hospitals now care for more immunocompromised patients than in previous times and also there is increased resistance of bacteria to available antibiotics.10

REFERENCES

- 1.Emori TG, Gaynes RP. An overview of nosocomial infections, including the role of microbiology laboratory. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1993;6:428–42. doi: 10.1128/cmr.6.4.428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jones JS, Hoerle D, Riekse R. Stethoscope: a potential vector of infection. Ann Emerg Med. 1995;26(3):296–9. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(95)70075-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Marinella MA, Pierson C, Chenoweth C. The stethoscope. A potential source of nosocomial infection? Arch Intern Med. 1997;157:86–90. doi: 10.1001/archinte.157.7.786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Smith MA, Mathewson JJ, Ulert IA, et al. Contaminated stethoscopes revisited. Arch Intern Med. 1996;156:82–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Parry MF, Hutchinson JH, Brown NA, et al. Gram-negative sepsis in neonates: a nursery outbreak due to hand carriage of Citrobacter diversus. Pediatrics. 1980;65(6):1105–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Steere A, Mallison GF. Handwashing practices for the prevention of nosocomial infections. Ann Intern Med. 1975;83:683–90. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-83-5-683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Livornese LL, Dias S, Samel C, et al. Hospital-acquired infection with vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus faecium transmitted by electronic thermometers. Ann Intern Med. 1992;117:112–6. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-117-2-112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Layton MC, Perez M, Heald P, et al. An out-break of mupirocin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus on a dermatology ward with an environmental reservoirs. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 1993;14:369–75. doi: 10.1086/646764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Patterson JE, Vecchio J, Patelick EL, et al. Association of contaminated gloves with transmission of Acinetobacter calcoaceticus var.anitratus in an intensive care unit. Am J Med. 1991;91:479–483. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(91)90183-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bernard L, Kereveur A, Durand D, et al. Bacterial contamination of hospital physicians’ stethoscopes. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 1999;20:626–8. doi: 10.1086/501686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]