Abstract

Background:

The appointment system in primary care is widely used in developed countries, but there seems to be a problem with its use in Saudi Arabia.

Objectives:

(1) To explore opinions and satisfaction of consumers and providers of care in Primary Health Care regarding walk-in and the introduction of the appointment system. (2) To examine factors which may affect commitment to an appointment system in PHC.

Subject and method:

Two hundred sixty (260) consumers above the age of 15 years as well as seventy (70) members of staff were randomly selected from 10 Primary Health Care Clinics in the National Guard Housing Area, Riyadh and asked to complete a structured questionnaire designed to meet the study's objectives.

Results:

The majority of consumers and providers of care were in favour of introducing appointments despite their satisfaction with the existing walk-in sysem. Respondents saw many advantages in the appointment system in PHC such as time saving, reduction of crowds in the clinics and guarantee of a time slot. The main perceived disadvantage was the limitation of accessibility to patients especially with acute conditions. The main organizational advantages and disadvantages perceived by providers were related to follow-ups of chronic patients, no shows and late arrivals. The majority of the patients preferred appointments in the afternoon and the possibility of obtaining an appointment over the telephone.

Conclusion:

In this study, both consumers and providers supportted the idea of introducing the appointment mixed system in primary care, but further study is required

Keywords: Appointment System, Primary Health Care, Consumers/Providers′ Opinion, and Consultation.

INTRODUCTION

The appointment system is common practice in Primary Health Care (PHC) clinics in the United Kingdom, and other Western countries.1,2 Its value in general practice is obviuos particularly in the planning of the daily work schedule. Needless to say, an efficient appointment system encourages more organized attendance and better care for chronic and other cases where follow-up is important.3,4 The appointment system in the PHC setting is perceived as an indicator of good quality service by providers and consumers.5,6 The system contributes positively to the appointment of the in improving accessibility of patient and consequently their satisfaction.7 Locally, the importance of an appointment system in PHC has been recognized not only for administrative and organizational advantages, but also as a means of improving the quality of patient care.8

However, patients attending primary health care in Saudi Arabia are seen on a walk-in basis: first come first served. To implement an appointment system effectively it is necessary to understand of the views of patients and service providers.

There is little, if any, published data on the opinions and satisfaction of consumers and providers using ‘Walk-In’ and how they perceive the idea of introducing the appointment system in PHC. This study explores this uncharted field.

METHODOLOGY

Setting and Study Population

This study was carried out in King Abdulaziz Military City at Khashmalaan, Riyadh belonging to Saudi National Guard. Ten primary health care clinics serve a population of more than 50,000. The sample of the study includes providers of care, physicians, nurses and clerks and a randomly selected sample of consumers above 15 years of age.

Questionnaires

Two separate questionnaires were used in this study. The first was a self administered questionnaire completed by providers to explore their satisfaction with the existing walk-in system and their views on the idea of introducing an appointment system. Also, the questions sought providers’ view on which group of patients they thought would benefit most from an appointment system and the advantages of ‘walk-in’ and appointments systems. A sample of consumers were interviewed by physicians using a structured questionnaire which included: demographic information, satisfaction with the present walk-in system, whether they would support the idea of a mixed system (i.e. walk-in and appointments) and their comments on the anticipated advantages and disadvantages of an appointment system. The questionnaire also included questions about patients’ behavior during consultations and some administrative and organizational issues.

Satisfaction of consumers was cross-tabulated with different variables to look for any possible significant association. Association was tested by Chi-Square Test and P value less than 0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

Consumers’ Views

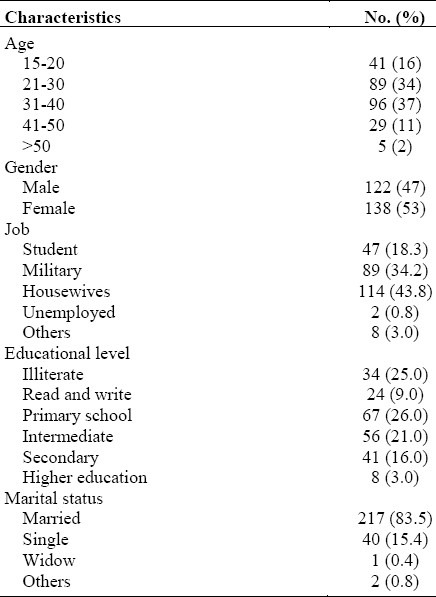

Table 1 shows demographics characteristics of consumer sample. Two Hundred and sixty consumers (above the age of 15 years) with a mean age of 31 years ± 9.5 were involved in this. Males constituting 47% and up to 75% of the sample had varying levels of education, ranging from just able to read and write to a high level of education. The majority of the sample (83%) were married and majority of the participating females (114) forming 44% of the total sample were housewives. However, 34% worked with the military, 17% were students, and 20% of the participants indicated that they had chronic illnesses.

Table 1.

Demographics characteristics of consumer sample

The majority (60%) were satisfied, 30% somewhat satisfied, 9.2% were not satisfied and 0.8% had no opinion. About 87% of the patients were in favour of the introduction of an appointment system to run concurrently with the existing walk-in system (mixed system). Only 9% disagreed and 4% of the samples were undecided.

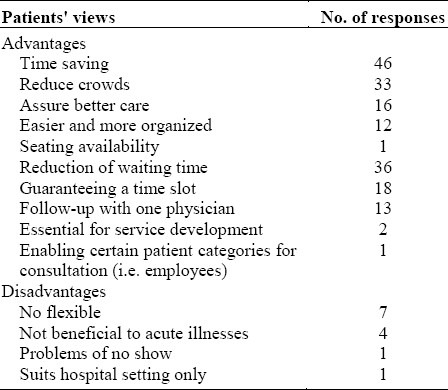

More women (91%) than men (84%) and patients with chronic illnesses (82%) supported the idea of a mixed system. However, the difference was not statistically significant (X2=7.49, P=0.11) m, (X2=6.88,P=0.14) respectively. Other variables including educational level, marital status, job etc. did not reveal any significant effect on patients' views. Patients were asked about the advantages of an appointment system using an open-ended questionnaire (178 responses were obtained) and categorized as shown in the table. Sixty-three (63%) percent of the patients preferred afternoon appointments and 65% wanted to make the appointments by telephone. Patients thought that appointments would be beneficial to all patients, especially those with chronic illnesses and at certain risk (pregnant women and children) as well as employees. Up to 27% of the sample said they had nowhere to sit in the waiting area while waiting to see the doctor. Fifty-four patients (21%) indicated that the doctor seemed rushed.

Providers’ views

Seventy staff members participated in the survey (35 physicians, 28 nurses and seven clerks). As regard the present walk-in system, 53% was satisfied, 20% were not satisfied and the remaining 27% were undecided. The majority were in favour of introducing an appointment system (79%). Providers see availability and accessibility as the advantages of walk-in but they acknowledge the following disadvantages: overcrowding; long waiting time, special difficulties for “follow-up,” especially patients with chronic illnesses.

Providers identify the following advantages for an appointment system: better organization of time for staff and patients; better follow-up for regular patients with chronic illnesses; less waiting time. The disadvantages were as follows: less availability particularly for urgent cases; problem of no shows and problem of late arrivals(Table 2). However, the staff felt that the appointment system would enhance the efficiency of care especially for chronic diseases and would offer flexibility to meet preferred timing for some patients.

Table 2.

Patients’ views on advantages/disadvantages of appointment system

DISCUSSION

The appointment system in PHC is well established in developed countries and has proved beneficial for both consumers and providers.1–4 In Saudi Arabia, though there is a feeling that an appointment system in PHC may not be acceptable for consumers, there is no scientific evidence to support or refuse this. The present study shows that consumers support the idea of introducing an appointment system in a PHC setting at King Abdulaziz Housing City (Iskan). This is supported by the findings of different published studies.9,10 Women and chronic patients in particular formed the majority of those in favour of the appointment system in PHC. The views of the two groups of patients are important and must be taken seriously. Women's health can affect the entire community and chronic diseases have significant social and economic impact on the community. Proper care for these groups of patients at PHC would save a lot of money, raise satisfaction and improve quality of care in the community.

The study population identified a number of advantages for the appointment system in PHC: more time for patients and doctors to deal with presented health problems; more organized environment; better planning of services; and better care. These are similar to published data.1,4,9–11 It is clear that the majority of both consumers and providers of PHC in this survey support the idea of introducing appointment system in PHC. However, both consumers and providers acknowledge the possible disadvantages of a rigid appointment system in PHC such as, less accessibility and less availability for acute cases. Thus, to avoid these perceived disadvantages an appointment system should initially be flexible and ‘mixed’ (walk-in and appointment).12,13

Interestingly enough 21% of the patients indicated that doctors seemed rushed during consultation, which indicated patients’ awareness of the pressure on the doctors during consultation. This is partly due to the unpredictable workload of the “Walk-In System” as well as other factors such as the increase in population size, a rise in chronic illnesses and the ever-increasing consumer expectations.14 This result is similar to that found in another study.11 This problem can be solved through the effective time management with the appointmen system and other activities.

These findings need to be considered seriously. However the authors acknowledge the following: Data presented hre may not be representative of the entire population since PHCs belong to the Ministry of Health. Further studies are therefore, needed. Secondly, there should be flexibility in the introduction of an appointment system in PHC. Thirdly, a successful appointment system in PHC must be financed and supported properly with information technology and good communication system.

The present study concludes that both consumers and providers are in favour of an appointment system in Primary Care system in Saudi Arabia.

REFERENCES

- 1.Cardew B. An appointment System Service for General Practitioners: Its Growth and Present Usage. BMJ. 1967;4:542–3. doi: 10.1136/bmj.4.5578.542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Appointment System in General Practice. BMJ. 1967;4:500–1. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Appointment System in General Practice. The Lancet. 1967;2(527):1190. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arbers, Sawyer L. Do Appointment System Work. BMJ. 1982;284:478–80. doi: 10.1136/bmj.284.6314.478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Engels Y, Campbell S, Dautzenberg M. Developing a framework of, and Quality Indicators for, General Practice Management in Europe. Family Practice. 2005;22:215–22. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmi002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Al-Dogaither A, Saeed A. Consumer's Satisfaction with Primary Health Services in the City of Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. Saudi Med J. 2000;21(S):447–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Al-Omar B. Patients’ expectations, Satisfaction and Future Behavior in Hospitals in Riyadh City. Saudi Med J. 2000;21(7):655–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tawfik K. Appointment System and Computer Use in Primary Care Centers. 1994 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Allen D, Marks B. Patient Access and Appointment Systems. The Practitioner. 1988;232:1380–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Aeber S. What is a good GP. BMJ. 1987;294:2887–8. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fallon C. Introduction of an Appointment System In General Practice: Surveys of Patient and Staff. Health Bulletin. 1990;48(5):232–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Starfield B. First Primary Care Essential. The Lancet. 1994;344:1129–33. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(94)90634-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jung H, Wensign M, Grol R. What makes a Good General Practitioner: Do Patients and Doctor Have Different Views? British Journal of General Practice. 1997;47:805–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gillam S, Pencheon D. Managing Demand in General Practice. BMJ. 1998;316:1895–8. doi: 10.1136/bmj.316.7148.1895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]