Abstract

Accreditation is usually a voluntary program, in which authorized external peer reviewers evaluate the compliance of a health care organization with pre-established performance standards. The aim of this study was to systematically review the literature of the attitude of health care professionals towards professional accreditation. A systematic search of four databases including Medline, Embase, Healthstar, and Cinhal presented seventeen studies that had evaluated the attitudes of health care professionals towards accreditation. Health care professionals had a skeptical attitude towards accreditation. Owners of hospitals indicated that accreditation had the potential of being used as a marketing tool. Health care professionals viewed accreditation programs as bureaucratic and demanding. There was consistent concern, especially in developing countries, about the cost of accreditation programs and their impact on the quality of health care services.

Keywords: Accreditation, attitude, systematic review

INTRODUCTION

Accreditation is usually a voluntary program, sponsored by a non-governmental agency (NGO), in which trained external peer reviewers evaluate the compliance of a health care organization with pre-established performance standards.[1] Quality standards for hospitals and other health care facilities developed by the American College of Surgeons, were first introduced in the United States in the “Minimum Standard for Hospitals” in 1917. After World War II, increased world trade in manufactured goods led to the creation of the International Standards Organization (ISO) in 1947.[2] Accreditation formally started in the United States with the formulation of Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations (JCAHO) in 1951. This model was exported to Canada and Australia in the 1960s and 1970s and reached Europe in the 1980s. Accreditation programs spread all over the world in the 1990s.[3] Other forms of systems including Certification and Licensure are used worldwide to regulate, improve and market health care providers and organizations. Certification involves the formal recognition of compliance with set standards (e.g. ISO 9000 standards) validated by external evaluation by an authorized auditor. Licensure involves a process by which a government authority grants permission, usually following inspection against minimal standards, to an individual practitioner or healthcare organization to operate in an occupation or profession. Although the terms, accreditation and certification are often used interchangeably, accreditation usually applies only to organizations, while certification may apply to individuals, as well as to organizations.[2]

Aim

To review theliterature on the attitude of health care professionals towards accreditation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design

This was a systematic qualitative review of the literature of the attitude of health care professionals towards accreditation. A comprehensive updated search of four electronic bibliographic databases including Medline from 1996-January 2011, Cinhal, from 1982-January 2011, Embase from 1980-January 2011, and HealthStar from 1980-January 2011 was done. Several keywords in different combinations including ‘accreditation’, “Health Services”, ‘quality’, ‘quality indicators’, ‘quality of health care’, ‘attitude’, and ‘impact’ were utilized. We included studies that had evaluated the attitude of health care professionals (physicians, nurses and allied health personnel) towards accreditation. An analysis of abstracts of the citations was conducted to identify substantial studies relevant to the accreditation of health services. The bibliographies of all selected articles and relevant review articles were scrutinized to identify additional studies. Experts in the area of accreditation were contacted to identify relevant studies. No language restrictions were applied.

RESULTS

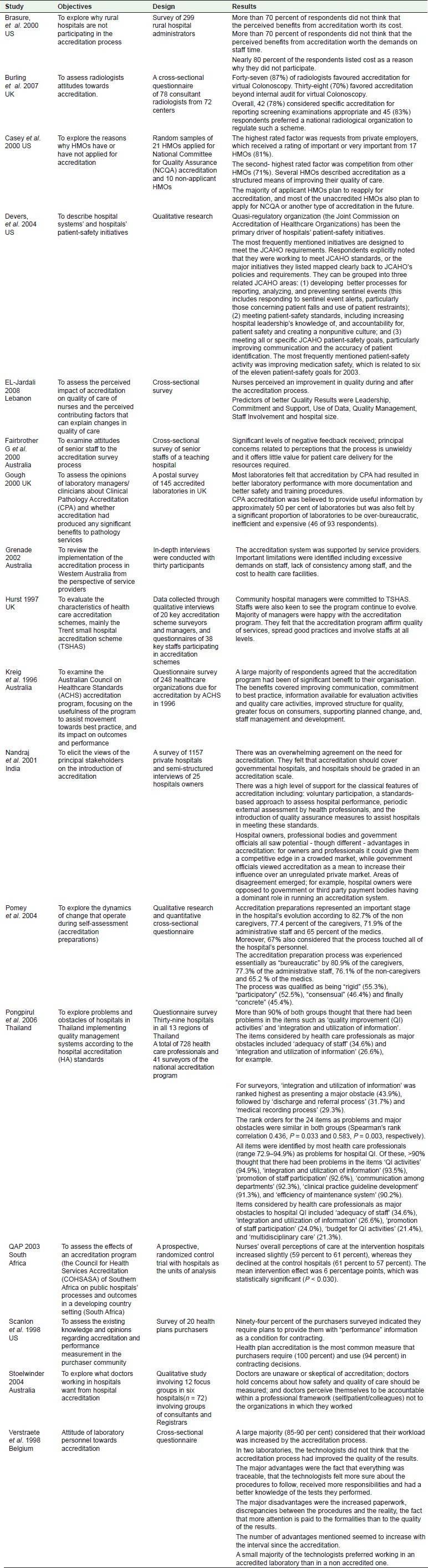

Seventeen studies evaluating the attitude of health care professionals towards accreditation were identified [Table 1].

Table 1.

Description and results of included studies

Health professionals’ attitude towards accreditation

Four studies included a mixed group of staff. There were five studies of leaders of health organizations including senior staff, managers and owners. Two of the studies were of purchasers of health services, two of physicians, two of nurses and a final two studies of laboratory personnel.

Attitude of mixed group of health care professionals

In a qualitative and cross-sectional study which involved interviewing senior staff (n = 67) and surveying hospital staffs (n = 1693) of a French teaching hospital, 77% of participants viewed accreditation preparation as an important stage in the hospital's evolution. Of the participants, 67% believed that the process touched all of the hospital's personnel and believed that irreversible changes occurred at the level of the hospital. However, 81% believed that the accreditation preparation process was experienced essentially as bureaucratic and prescriptive.[4] A large Australian study that surveyed health care providers in 248 health care organizations (n = 663) indicated that 72% of the participants believed that accreditation had been of significant benefit to their organization.[5] In a large cross-sectional survey conducted in Thailand (n = 769), more than 90% of the health care professionals thought that there had been problems with accreditation on such items as ‘quality improvement (QI) activities’ and ‘integration and utilization of information’.[6] In a qualitative study of providers of residential care for the aged, conducted in Australia (n = 30) participants’ perception of accreditation was positive. For example, it ensured high standards of care for residents, and improved management. However, mention was also made of important limitations, including excessive demands on staff, lack of consistency amongst assessors and the cost to facilities.[7]

Attitude of leaders of health organizations

In a survey of 299 rural administrators of non-JCAHO accredited hospitals, 70% of the respondents did not think that the perceived benefits from accreditation were worth its cost or worth the demands on staff's time.[8] In a survey of hospital owners in India (n = 94) which also used semi-structured interviews, there was an overwhelming agreement on the need for accreditation. All participants indicated that accreditation should be independent and not for profit. They felt that accreditation has the potential of being used as a marketing tool. The biggest obstacle to the introduction of accreditation in poorly resourced settings, such as India, was financial.[9] In a survey conducted in an Australian teaching hospital (n = 88), the attitudes of senior staff towards the accreditation survey process were negative. The concerns were mainly related to participants’ belief that in terms of patient care delivery and the significant amount of human resources it consumed, accreditation was of little value.[10] A large qualitative study conducted in the United States involving twelve communities suggested that a regulatory body (such as JACHO), not market forces, had the strongest impact on hospitals’ efforts to improve patient safety.[11] A qualitative study involving interviews of 20 key accreditation surveyors and managers, and the survey of 38 key staffs found that hospital managers were committed to accreditation. A majority of managers felt that accreditation programs affirmed the quality of services, promoted good practices and involved staff at all levels.[12]

Attitude of purchasers of health services

In a survey of purchasers of health plans in the United States (n = 20), most respondents indicated that the value of accreditation was worth its cost (94%); however, 83% did not feel that accreditation alone determined an acceptable health plan.[13] In a qualitative study involving representatives of 31 HMOs, 71% of HMOs found the standards of the National Committee for Quality Assurance (NCQA) reasonable and planned to re-apply for NCQA accreditation.[14]

Attitude of physicians

In a qualitative Australian study (n = 72) doctors were generally unaware of accreditation and skeptical of it. Their concern was on how quality of care was to be measured. Doctors felt accountable within a professional framework, to themselves, the patient and family, their peers and to their profession; but not to accreditation bodies.[15] In a cross-sectional questionnaire of consultant radiologists, 87% of radiologists favored accreditation for virtual colonoscopy.[16]

Attitude of nurses

In the large randomized controlled trial, the (QAP) nurses’ overall perceptions of care (n = 1048), at the accredited hospitals increased significantly (59% to 61%), compared to the control hospitals (declined from 61% to 57%).[17] In a large rigorous survey conducted in Lebanon (n = 1048), nurses perceived a significant improvement of results in quality in hospitals as an outcome of accreditation.[18]

Attitude of laboratory personnel

A survey of laboratory personnel in three laboratories in Belgium and Netherland (n = 77) showed conflicting results. Of the lab personnel in two laboratories, 87% did not think that the accreditation process improved the quality of the laboratory results; however, the majority of laboratory personnel felt more confident about the procedures to follow, were given more responsibilities and had better knowledge of the tests they performed. Laboratory personnel preferred working in an accredited laboratory than in a non- accredited one.[19] In a survey of Clinical Pathology laboratories (n = 93), 75% laboratories felt that accreditation resulted in an improvement of laboratory services by introducing more documentation and better health and safety training procedures. Half of the participants viewed accreditation as being over bureaucratic, inefficient and expensive.[20]

DISCUSSION

In general, the attitude of the health care professionals in the seventeen studies that had evaluated attitudes of health care professionals towards accreditation was supportive. In a few studies, the attitude to accreditation was negative because the participants did not believe that accreditation had a significant impact on the quality of health care services and also because of the significant additional cost involved.

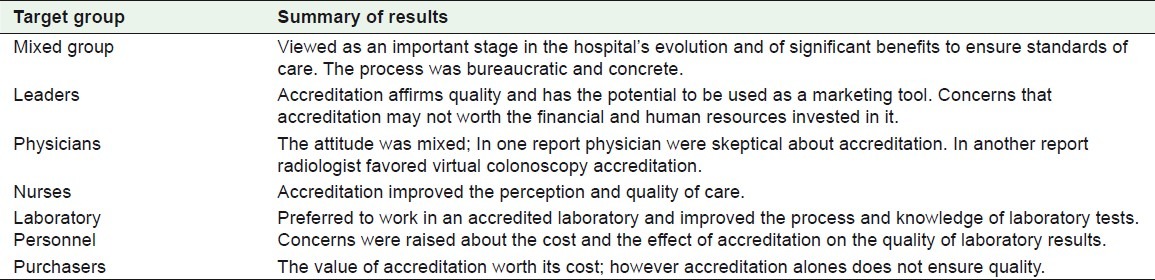

The attitude of senior staffs, managers and owners towards accreditation was conflicting. In some studies, the attitude revealed was positive since to the participants, accreditation improved quality and could potentially be used as a marketing tool. In other studies, the attitude of hospital leaders was negative, for they thought that accreditation was neither worth its cost nor the demands on staff efforts and time. One explanation of these conflicting findings from leaders of health organizations was that the benefits of accreditation were not well-established. In general, the attitude of purchasers of health services was positive, which confirms the view of the owners of hospitals that accreditation could be used as a marketing tool. Studies involving a mixed group of health care professionals revealed a favorable attitude towards accreditation as they thought it produced beneficial changes at all levels of health organization. However, there were several concerns including the bureaucratic, prescriptive nature of the accreditation process, as well as the financial burden it imposed on health care facilities. The perception of nurses towards accreditation was generally favorable; however, physicians were skeptical of accreditation and raised concerns on how the quality indicators were measured. In contrast, radiologists were in favor of the accreditation. Physicians are known to resist clinical governance schemes. This resistance can be minimized when evidence is cited to prove that these schemes can improve the quality of health services.[21,22] Two studies have shown that the attitude of laboratory personnel towards accreditation was positive as it increased the confidence of laboratory personnel with the procedures they follow. However, the majority thought that accreditation did not improve quality and viewed it as inefficient and expensive [Table 2].

Table 2.

Summary of the results of the attitude towards accreditation

The cost of accreditation was a persistent concern of health care organizations especially in developing and low income countries. The concern of leaders of health care organizations was also that the benefits of accreditation might not be worth the cost and the effort involved in the process. These concerns can only be addressed by means of a rigorous cost-benefit analysis.[23]

CONCLUSIONS

Several studies have shown that health care professionals were skeptical about accreditation because of concerns about its impact on the quality of health care services. Concerns raised about the cost of accreditation programs by health care professionals especially in developing countries were consistent. Healthcare professionals (especially physicians) have to be educated on the potential benefits of accreditation. It is also necessary to conduct a rigorous, independent evaluation of the cost-benefit analysis of accreditation of health services.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This Research was conducted as a partial requirement for the Master degree program in Health Systems and Quality Management, King Saud bin Abdulaziz University for Health Sciences in collaboration with Liverpool University. We would like to thank Prof. David Haran, University of Liverpool, Dr. Vanja Berggren, University of Liverpool, Prof. Zillyham Rojas Universidad de Costa Rica, Prof M. Magzoub King Saud bin Abdulaziz University for Health Sciences for their valuable feed-back during thesis defense process.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: Nil

REFERENCES

- 1.Shaw CD. Toolkit for accreditation programs. Australia: The International Society for Quality in Health Care; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Montagu D. London: Department for International Development Health Systems Resource Centre; [Last cited on 2003]. Accreditation and other external quality assessment systems for healthcare: Review of experience and lessons learned. Available from: http://www.dfidhealthrc.org/publications/health_service_delivery/Accreditation.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shaw CD. External quality mechanisms for health care: Summary of the ExPeRT project on visitatie, accreditation, EFQM and ISO assessment in European union countries. External peer review techniques. European foundation for quality management. International Organization for Standardization. Int J Qual Health Care. 2000;12:169–75. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/12.3.169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pomey M-P, Contandriopoulos A-P, François P, Bertrand D. Accreditation as a tool for organisational change. Int J Health Care Qual Assur. 2004;17:113–24. doi: 10.1108/09526860410532757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kreig T. An Evaluation of the ACHS accreditation program: Its effects on the achievement of best practice. Sydney: University of Technology; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pongpirul K, Sriratanaban J, Asavaroengchai S, Thammatach-Aree J, Laoitthi P. Comparison of health care professionals’ and surveyors’ opinions on problems and obstacles in implementing quality management system in Thailand: A national survey. Int J Qual Health Care. 2006;18:346–51. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzl031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Grenade L, Boldy D. The accreditation experience: Views of residential aged care providers. Geriaction. 2002;20:5–9. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brasure M, Stensland J, Wellever A. Quality oversight: Why are rural hospitals less likely to be JCAHO accredited? J Rural Health. 2000;16:324–36. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-0361.2000.tb00483.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nandraj S, Khot A, Menon S, Brugha R. A stakeholder approach towards hospital accreditation in India. Health Policy Plan. 2001;16(suppl_2):70–9. doi: 10.1093/heapol/16.suppl_2.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fairbrother G, Gleeson M. EQuIP accreditation: Feedback from a Sydney teaching hospital. Aust Health Rev. 2000;23:153–62. doi: 10.1071/ah000153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Devers K, Pham H, Liu G. What is driving hospitals’ patient-safety efforts? Health Aff. 2007;23:103–15. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.23.2.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hurst K. The nature and value of small and community hospital accreditation. Int J Health Care Qual Assur. 1997;10:94–106. doi: 10.1108/09526869710167012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Scanlon D, Hendrix T. Health plan accreditation: NCQA, JCAHO, or both? Manag Care Q. 1998;6:52–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Casey M, Klingner J. HMOs serving rural areas: Experiences with HMO accreditation and HEDIS reporting. Manag Care Q. 2000;8:48–59. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stoelwinder J. A study of doctors’ views on how hospital accreditation can assist them provide quality and safe care to consumers. Melbourne, Australia: Monash University, Department of Epidemiology and Preventive Medicine; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Burling D, Moore A, Taylor S, SLa Porte S, Marshall M. Virtual colonoscopy training and accreditation: A national survey of radiologist experience and attitudes in the UK. Clin Radiol. 2007;62:651–9. doi: 10.1016/j.crad.2007.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Salmon J, Heavens J, Lombard C, Tavrow P. The impact of accreditation on the quality of hospital care. KwaZulu-Natal province republic of South Africa: Published for the U.S. agency for international development (USAID) by the quality assurance project, University Research Co; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 18.El-jardali F, Jamal D, Dimassi H, Ammar W, Tchaghchaghian V. The impact of hospital accreditation on quality of care: Perception of Lebanese nurses. Int J Qual Health Care. 2008:1–9. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzn023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Verstraete A, Van Boeckel E, Thys M, Engelen F. Attitude of laboratory personnel towards accreditation. Int J Health Care Qual Assur. 1998;11:27–30. doi: 10.1108/09526869810199629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gough L, Reynolds T. Is clinical pathology accreditation worth it.A survey of CPA-accredited laboratories? Clin Perform Qual Health Care. 2000;8:195–201. doi: 10.1108/14664100010361746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Campbell SM, Sheaff R, Sibbald B. Implementing clinical governance in English primary care groups/trusts: Reconciling quality improvement and quality assurance. Qual Saf Health Care. 2002;11:9–14. doi: 10.1136/qhc.11.1.9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gollop R, Whitby E, Buchanan D, Ketley D. Influencing skeptical staff to become supporters of service improvement: A qualitative study of doctors’ and managers’ views. Qual Saf Health Care. 2004;13:108–14. doi: 10.1136/qshc.2003.007450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Øvretveit J. Quality evaluation and indicator comparison in health care. Int J Health Plann Manage. 2001;16:229–41. doi: 10.1002/hpm.629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]