Abstract

Background:

Amongst various modalities of post operative rehabilitation in a total knee replacement (TKR) surgery, this study focuses on evaluating the effect of additional yoga therapy on functional outcome of TKR patients.

Materials and Methods:

A comparative study was done to compare the effects of conventional physiotherapy and additional yoga asanas, on 56 patients undergoing total knee arthroplasty due to osteoarthritis. After obtaining written informed consent, the patients were alternately assigned to two groups: Conventional and experimental. Baseline WOMAC scores for pain and stiffness were taken on third post operative day. The subjects in conventional group received physiotherapy rehabilitation program of Sancheti Institute where the study was conducted, the experimental group received additional modified yoga asanas once daily by the therapist. After discharge from the hospital, patients were provided with written instructions and photographs of the asanas, two sets of WOMAC questionnaire with stamped and addressed envelopes and were instructed to perform yoga asanas 3 days/week. Subjects filled the questionnaire after 6 weeks and 3 months from the day of surgery and mailed back. The primary outcome measure was WOMAC questionnaire which consists of 24 questions, each corresponding to a visual analog scale, designed to measure patient's perception of pain, stiffness and function.

Results:

The results suggest that there was a significant change (P<0.05) for all the groups for pain, stiffness and function subscales of WOMAC scale. The pain and stiffness was found to be less in experimental group receiving additional yoga therapy than in conventional group on 3rd post operative day, 6 weeks and 3 months after the surgery.

Conclusion:

A combination of physiotherapy and yoga asana protocol works better than only physiotherapy protocol. Larger and blinded study is needed.

Keywords: Knee osteoarthritis, total knee replacement, western Ontario and Mcmaster universities scale, yoga asanas

INTRODUCTION

Osteoarthritis is the most common joint disorder leading to disability and related health conditions.[1,2] This disease results in morphological and molecular changes of cells and matrix, leading to loss of articular cartilage, sclerosis, abnormal remodeling and attrition of the subchondral bone, osteophytes.[3]

Conservative management consists of pharmacological management, rest, gradual progressive exercises, joint protection strategies and alternative therapies. Surgical management consists of surgical bone resurfacing, osteotomy, repositioning of bones, synovectomy, patellectomy, arthroscopic evaluation and excision of loose bodies, arthrodesis and total knee replacement (TKR). TKR continues to be the best option for improving knee pain and function, with the ability to correct varus or valgus articular deformity in end-stage OA. It is the treatment of choice in patients over age 55 with progressive and painful OA in whom nonsurgical and less-invasive treatments have failed.[4] The commonly used prosthesis is RPF (rotating platform). INDUS prosthesis is a indigenously manufactured monoblock posterior stabilized design. This design requires minimal resection of bone and also offers high flexion so that the patient can squat. Use of the INDUS knee prosthesis has a favorable short-term outcome, with a mean range of 135° flexion and excellent knee scores.[5]

Yoga asanas are a series of scientifically developed, slow, rhythmic and graceful movements of various joints and muscles of the body aimed at attaining a definite posture,[6] for a brief period of time progressing to static state of holding and again returning to the starting postures. Post operative rehabilitation is one of the most important components of TKR surgery. Various customized protocols are available based on the standard physiotherapy principles to improve range of motion and reduce pain.[7] Asanas encourage different groups of muscles to assume a state of stable equilibrium by introducing shifts in the line of gravity. Asanas involve stretching by which one can actively affect the functioning of the locomotor system. Changes in the length of muscle and tendons subsequently cause anatomical, bio-chemical and physiological changes, which will affect both the biomechanical function of joints and metabolism of soft tissues.[8] Clinical evidence also suggests that intramuscular connective tissue may account for a significant amount of limitation of the joint motion with ageing.[9] Asanas develop awareness, stability through co-contraction during holding the pose. There is an involvement of multiple joints; hence, stretching of soft tissues and muscles is possible.[10,11] Shavasana practice helps in relaxation and psychological well being.[7] This may assist in recovery post TKR. No adverse effects would occur, if correct technique is practiced.[8] Lingrad et al.,[12] report that patients have increased psychological distress due to surgery and post operative period. This possibly can be reduced by yoga asanas.

The purpose of our study was to know if yoga asanas have any added advantage as demonstrated in conservative management of knee osteoarthritis with conventional therapy for treating patients with total knee replacement. Yoga asanas were selected in consultation from yoga teachers, operating surgeon and the first author. The first author is also a certified yoga trainer.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

A prospective cohort study was conducted at a super specialty orthopedic hospital on 51 patients undergoing total knee replacement due to osteoarthritis. Approval was obtained from ethical committee at Sancheti institute for Orthopaedics and Rehabilitation, where the study was conducted. Patients undergoing revision arthroplasty, or having post operative infections or requiring extended immobilization were excluded. Patients with any neuro-vascular deficit or compromise were excluded.

Patients were explained about the study and a written consent was taken. Subjects operated with total knee replacement were recruited into two groups: Conventional and experimental alternately for allocation. The subjects in conventional group received routine protocol of the center mentioned later. Subjects in experimental group received routine conventional treatment and additional modified yoga asanas, where the asanas were modified in terms of the terminal range suitable for post TKR patients. Baseline WOMAC scores for pain and stiffness were evaluated on third post operative day, the function subscale in WOMAC questionnaire could not be measured on third post operative day. Experimental group received yoga asanas at least once daily by the evaluation therapist during hospital stay. After discharge from the hospital, subjects were provided with written instructions of the asanas and the photographs of attaining asanas. They were also provided with two sets of WOMAC questionnaire with stamped and addressed envelopes. Subjects were asked to fill the questionnaire after 6 weeks and 3 months from the day of surgery. The filled WOMAC questionnaire was mailed back; a reminder call was made to fill the form. A diary was given to the subjects to note down the daily record of exercises. Frequency of yoga asanas was 3 days/week after discharge from the hospital.

Medical management for unilateral TKR: Day 1 - Surgery analgesia via epidural, Day 2 - Antibiotics and analgesia via IV drip, Day 3 onwards oral antibiotics, analgesics and injections for management of other medical conditions as per the prescription of the physician.

Hospital protocol for conventional group post TKR: Day 1- Circulatory exercises for lower limbs, breathing exercises and isometric quadriceps and hamstrings, Day 2- Knee range movement in bed/bed-side sitting. Day 3- Standing with walking frame weight bearing as per tolerance. Day 4- Stair climbing with assistance and cryotherapy- cold pack applications 3/4 times as needed. After 6 weeks- The above exercises and Wall slides, forward lunges, and step-ups, step down and progress to stationary bicycling, independent ambulation, proprioception and strength training.

Additional Yoga asanas for group 3-5: POD-Shavasana, Tadasana and Paschimottanasana. After one weekAdd: Pavanamuktanasana, Baddha-konasana, post stitch removal- Add: Ardha shalabasana. At six weeks- Add: Virbhadrasana, Utkatasana.

Statistical analysis

Microsoft Excel 2007 and SPSS 10 version were used for data analysis. Nonparametric tests were used. Relative differences were calculated between the time duration of each group and Mann- Whitney ‘U’ test was used to compare between groups. Wilcoxonsign ranked test was used to evaluate differences within paired scores. Spearman's correlation co-efficient was used for comparison and Mann- Whitney ‘U’ test to check the difference between males and females in functional scores . Level of significance set for each test was P<;0.05.

RESULTS

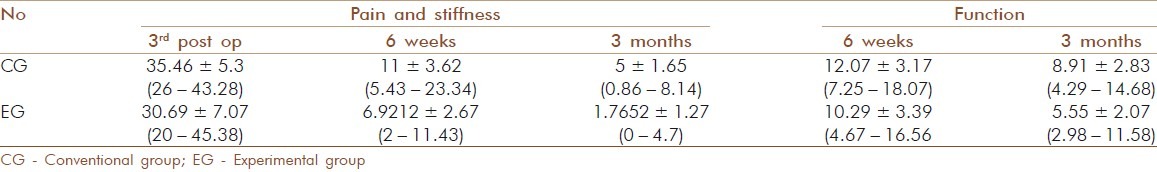

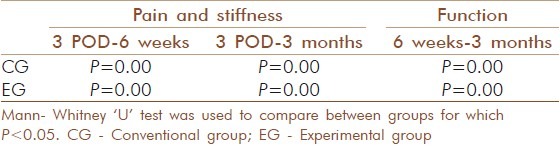

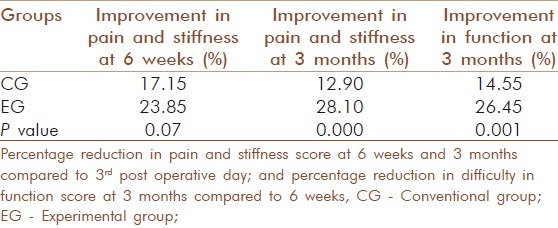

There were two groups: Conventional group with 26 subjects and experimental group with 25 subjects with mean age who completed the study being 62.5 ± 7.12 (51-77) and 60.9 ± 9.01 (38-78) respectively. There were 36 female (18 in each group) and 15 male (8 and 7) subjects. Forty four were having bilateral arthritis and eight were having unilateral knee arthritis. The mean BMI for all the subjects was 31.84 ± 5.35 (21.3-42.9). Forms for 3 subjects (2 females, 1 male) in conventional group and 1 male in experimental group could not be traced. Hence they were considered lost to follow-up and not considered for analysis. The mean values of WOMAC pain and stiffness and the function score at 3rd post operative day (POD), at 6 weeks and 3 months are documented [Table 1]. The absolute values of the variables were found to be lower in the experimental group than in the conventional group. We also considered the readings at post operative day 3 as the baseline and compared it with the 6 weeks and 3 months reading. There was significant improvement in all scores at 6 weeks and 3 months as compared to post operative day 3 reading in both the groups [Table 2]. Comparing the percentage improvement in both groups [Table 3], it was noted that there was significant improvement on pain, stiffness and functional scores in the experimental group as compared to the conventional group at all intervals.

Table 1.

Pain, stiffness and function subscale of WOMAC scale in conventional and experimental group at 3rd post operative day, 6 weeks and 3 months

Table 2.

Pain, stiffness and function subscale of WOMAC scale within group

Table 3.

Percentage reduction in pain, stiffness and function subscale of WOMAC scale in conventional and experimental group

DISCUSSION

The aim of this study has been to analyze the effects of additional yoga asanas combined with conventional treatment for functional outcome of patients after total knee replacement. We found that patients practicing yoga had better pain relief, less stiffness and better function. There were no adverse effects reported by subjects in either group. This suggests that practice of yoga asanas post TKR was safe as previous studies are done in conservative management. There was significant improvement in pain in both the groups. This can be attributed to the surgical procedure, that is removal of pain producing structures, ligamentous balancing to correct the deformity and by reducing the stresses on the periarticular structures. Additionally they also received gait training, closed kinetic chain exercises, open kinetic chain exercises and stretching as conventional treatment to reduce pain, and improve function. Isometric exercises promote muscle relaxation and increase in circulation to wash out the chemical irritants. As strength training requires higher force progressively, there is increased synchronization and improvement in the rate of motor unit firing. This leads to decrease in the inhibitory function of the central nervous system; hence, muscle strength increases. Increase in muscle strength may have contributed in improving the overall functional status of the patient.

In experimental Yoga group, the pain relief was better than the conventional therapy group. Pain relief secondary to yoga practice in patients with knee OA is documented by Kolasinski et al.,[10] and Bukowski et al.[11] Studies on the effects of yogasanas on osteoarthritis of hand by Garfinkel et al.,[13] and carpal tunnel syndrome by Garfinkel et al.,[14] reveal that yogasanas are beneficial in management of OA for reduction of pain while improving function. We believe that the reduction in pain can be attributed to Shavasana. When the activity of a facilitatory upper motor neuron is diminished in cerebral cortex, it will send fewer nerve impulses per second to lower motor neurons; this in turn will help in relaxation of the skeletal muscles. Conscious relaxation in Shavasana also helps in stimulation of inhibitory pathways, if such a neuron starts firing more nerve impulses per second than usual to the lower motor neurons, it would help silence the motor neuron independently causing muscle relaxation and pain relief in turn.[8] Thus the experimental group not only had muscle strengthening but also relaxation of the muscles allowing for faster recovery from pain. Bera et al.,[15] have found Shavasana as very effective to normalize effects of stress. Malathi et al.,[16] demonstrated positive effects of yogic practices on subjective well being on 48 volunteers in a period of 4 months. Chaudhary et al.,[17] demonstrated positive effects of Shavasana. In a study by Streeter et al.,[18] there was a 27% increase in GABA levels in the yoga practitioner group after the yoga session (0.20 mmol/kg) on 8 yoga practitioners. These findings demonstrate that in experienced yoga practitioners, brain GABA levels increase after a session of yoga.

The hip and knee flexor muscles usually develop tightness because of the inactivity caused due to osteoarthritis. Gait difficulties and problems of daily inertia may relate directly to tight knee and hip flexors, because of the strength needed to overcome the tightness. As mentioned above, physiotherapy protocol has various modalities of reducing muscle stiffness and in our series too there was significant improvement in both the groups. In addition, yoga asanas are designed by adding many components of the body parts, keeping in mind the functional tasks like ambulation, ascending, descending stairs, the muscle work for performing the activities of daily living and flexibility components in the older adults. Asanas like Ardha-shalabhasana, Virabhadrasana, Badhakonasana, Pawanamuktasana, and Utkatasana involve isometric contraction of agonists and stretching of antagonists. Holding poses leads to increase in joint stability, lengthening of tight muscles improving their excursion on joints, thus overall improvement in function and reduction of pain. Golgi tendon organs (GTO) are sensory organs located near muscle tendon junction of extrafusal muscle fibers. They monitor changes in tension of muscle tendon units and transmit sensory information via Ib fibers with passive stretch or active muscle contraction during normal movement. When tension develops in a muscle, the GTO fires and inhibits alpha motor neuron activity, and decreases tension in the muscle-tendon unit being stretched. During the practice of yoga, a slow stretch force is applied to muscle, the GTO fires and inhibits tension in the muscle, allowing the parallel elastic component, the sarcomere of the muscle to remain relaxed and lengthened.[7]

The yoga asanas are functional postures. Tadasana is standing pose progressing to standing and balancing on toes. There is awareness of standing with equal weight bearing, neutral spine and retraction and depression of scapula in ease. Paschimottanasan is long sitting, attempting to touch toes. This stretches posterior structures- thoraco-lumbar fascia, hamstrings and gastrosoleus. Ardha shalabhasana is assisted/active hip extension. Pavan-muktasana is assisted/active alternate hip knee flexion, then bilateral hip knee flexion and posterior pelvic tilt. Baddhakonasana is a complex pose of unilateral progressing to bilateral hip flexion, external rotation, abduction and knee flexion. This stretches multiple muscles and soft tissues. Virbhadrasana is similar to forward lunges and Utkatasana is mini squat and rise.

In a study by Carlson et al,[19] stretching displayed reduction in sadness; EMG activity at the muscles stretched and self-reported muscle tension. Thus, indicating promotion of relaxation and well-being. These may be reasons of better function and less stiffness in both groups. A small but significant cause of improved function may be effect of Ardha Shalabhasana on hip flexors. A lack of full hip extension in the elderly is relatively prevalent and may be predisposed by periods of prolonged sitting. The forward placement of the pelvis and trunk may shift the force line of gravity slightly anterior to the hip. Therefore, the hip extensors should produce greater torque in order to overcome the tightness of hip flexors. In Ardha Shalabhasana, the hip flexors are stretched and the hip extensors are strengthened, which helps to overcome the tightness and improving function and gait.

An integrated approach of yoga therapy has demonstrated improvement in knee disability and quality of life in patients with OA knees; due to its stress reducing effect since yoga is meant to bring about better emotional stability.[20] Psychological factors have been reported to have an adverse impact on outcomes following lower extremity arthroplasty. Lingard et al.,[12] reported that many patients with psychological distress demonstrate a substantial decrease in improvement following surgery. Patients who are distressed have slightly worse pain preoperatively and for up to two years following knee arthroplasty as compared with patients with no psychological distress.[12] As yoga helps to relax and reduce psychological distress, this may induce pain relief and functional improvement.

Limitations of the study were the following: Blinding was not possible for the study and preoperative evaluation of pain and function was not made. Evaluation of spine and hip mobility and tightness was not done. The sample size is relatively small. Further scope is to compare conventional protocol with yogasanas.

CONCLUSION

This study showed significant improvements in the experimental yoga group for the subscales of the WOMAC scale when compared to a conventional therapy group. A larger sample blinded study will be required to further validate the results. Yogasanas can enhance pain management and improve function post TKR when used in conjunction with physiotherapy.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

Authors will like to acknowledge Indian Orthopaedic Research Group for help in Preparation of Manuscript.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared

REFERENCES

- 1.Felson D, Zhang Y, Hannan MT, Naimark A, Weissman BN, Aliabadi P, et al. The incidence and natural history of knee OA in the elderly: The Framingham OA Study. Arthritis Rheum. 1995;38:1500–5. doi: 10.1002/art.1780381017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Felson DR, Naimark A, Anderson J, Kazis L, Castelli W, Meenan RF. The prevalence of kneeosteoarthritis in the elderly: The Framingham OA study. Arthritis Rheum. 1987;30:914–8. doi: 10.1002/art.1780300811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Porter SB. Osteoarthritis. Tidy's Physiotherapy. (13th ed) 2003;9:195–206. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rosneck J, Hiquera CA, Tadross N, Krebs V, Barsoum WK. Managing knee osteoarthritis before and after arthroplasty. Cleve Clin J Med. 2007;74:663–71. doi: 10.3949/ccjm.74.9.663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sancheti KH, Laud NS, Bhende H, Reddy G, Pramod N, Mani JN. The INDUS knee prosthesis - Prospective multicentric trial of a posteriorly stabilized high-flex design: 2 years follow-up. Indian J Orthop. 2009;43:367–74. doi: 10.4103/0019-5413.55976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Joshi J, Kotwal P. 2nd ed. Noida: Elsevier India private limited; 2011. Yoga asanas and physiotherapy, Essentials of Orthopaedics and applied Physiotherapy; pp. 565–74. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kisner C, Colby LA. 4th ed. (The knee)India, Delhi: Jaypeepublications; 2002. Therapeutic exercise; foundations and techniques; pp. 157–9. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Coulter D. 1st ed. Jawahar Nagar, Delhi, India: Motilal Banarasidas Publishers; 2002. Anatomy of Hatha Yoga, A manual for students, Teachers, and Practitioners; pp. 541–9. Chap 1.10. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Neumann DA, Guccione AA. Geriatric Physical therapy. 2nd ed. Maryland Heights, Missouri: Mosby publishers; 2000. Arthrokinesiological considerations in aged adults; pp. 66–9. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kolasinski SL, Garfinkel M, Tsai AG, Matz W, Van Dyke A, Schumacher HR. Iyengar yoga for treating symptoms of osteoarthritis of the knees: A pilot study. J Altern Complement Med. 2005;11:689–93. doi: 10.1089/acm.2005.11.689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bukowski EL, Conway A, Glentz LA, Kurland K, Galantino ML. Effectof Iyengaf yoga and strengthening exercises for people living with osteoarthritis of knee: A case series. Int Q Community Health Educ. 2006;26:287–305. doi: 10.2190/IQ.26.3.f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lingard EA, Riddle DL. Impact of psychological distress on pain and function following knee arthroplasty. J BoneJoint Surg Am. 2007;89:1161–9. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.F.00914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Garfinkel MS, Schumacher HR, Jr, Husain A, Levy M, Reshetar RA. Evaluation of ayoga based regimen for treatment of osteoarthritis of the hands. J Rheumatol. 1994;21:2341–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Garfinkel MS, Singhal A, Katz WA, Allan DA, Reshetar RA, Schumacher HR., Jr Yoga-based intervention for carpal tunnel syndrome: A randomized trial. JAMA. 1998;280:1601–03. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.18.1601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bera TK, Gore MM, Oak JP. Recovery from stress in two different postures and in Shavasana-a yogic relaxation posture. Indian J Physiol Pharmacol. 1998;42:473–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Malathi A, Damodaran A, Shah N, Patil N, Maratha S. Effect of yogic practices on subjective well being. Indian J Physiol Pharmacol. 2000;44:202–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chaudhary AK, Bhatnagar HN, Bhatnagar LK, Chaudhary K. Comparative study of the effect of drugs and relaxation exercise (yoga shavasana) in hypertension. J Assoc Physicians India. 1988;36:721–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Streeter CC, Jensen JE, Perlmutter RM, Cabral HJ, Tian H, Terhune DB, et al. Yoga Asana sessions increase brain GABA levels: A pilot study. J Altern Complement Med. 2007;13:419–26. doi: 10.1089/acm.2007.6338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Carlson CR, Collins FL, Nitz AJ, Sturgis ET, Rogers JL. Muscle stretching as an alternative relaxation training procedure. J Behav Ther Exp Psychiatry. 1990;21:29–38. doi: 10.1016/0005-7916(90)90046-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ebnezar J, Nagarathna R, Bali Y, Nagendra HR. Effect of an integrated approach of yoga therapy on quality of life in osteoarthritis of the knee joint: A randomized control study. Int J Yoga. 2011;4:55–63. doi: 10.4103/0973-6131.85486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]