Abstract

Background & objectives:

Artificial corneal endothelium equivalents can not only be used as in vitro model for biomedical research including toxicological screening of drugs and investigation of pathological corneal endothelium conditions, but also as potential sources of grafts for corneal keratoplasty. This study was aimed to demonstrate the feasibility of constructing human corneal endothelium equivalents using human corneal endothelial cells and acellular porcine corneal matrix.

Methods:

Porcine corneas were decellularized with sodium dodecyl sulphate (SDS) solution. Human corneal endothelial cells B4G12 were cultured with leaching liquid extracted from the acellular porcine corneal matrix, and then cell proliferative ability was evaluated by MTT assay. B4G12 cells were transplanted to a rat corneal endothelial deficiency model to analyze their in vivo bio-safety and pump function, and then seeded and cultured on acellular porcine corneal matrix for two wk. Corneal endothelium equivalents were analyzed using HE staining, trypan blue and alizarin red S co-staining, immunofluorescence and corneal swelling assay.

Results:

The leaching liquid from acellular porcine corneal matrix had little influence on the proliferation ability of B4G12 cells. Animal transplantation of B4G12 cells showed that these cells had similar function to the native cells without causing a detectable immunological reaction and neoplasm in vivo. These formed a monolayer covering the surface of the acellular porcine corneal matrix. Trypan blue and alizarin red S co-staining showed that B4G12 cells were alive after two wk in organ culture and cell boundaries were clearly delineated. Proper localizations of ZO-1 and Na+/K+ ATPase were detected by immunofluorescence assay. Functional experiments were conducted to show that the Na+/K+ ATPase inhibitor ouabain could block the ionic-pumping function of this protein, leading to persistent swelling of 51.7 per cent as compared to the control.

Interpretation & conclusions:

Our findings showed that B4G12 cells served as a good model for native corneal endothelial cells in vivo. Corneal endothelium equivalents had properties similar to those of native corneal endothelium and could serve as a good model for in vitro study of human corneal endothelium.

Keywords: Biomaterial, corneal endothelium, decellularized carrier, organ culture

Of the three major cell layers of course, the innermost monolayer of specialized endothelial cells maintains corneal transparency by its barrier function and pump-leak mechanism. Endothelial cells maintain stroma dehydration at 78% by transporting ions and fluid across the cell membranes. Since this is an active and energy-consuming process, it is described as “pump function”. And the protein Na+/K+ ATPase mainly involved in this process is called the “pump protein”. The number of adult human corneal endothelial cells (CECs) decreases with age due to the limited proliferative capacity of these cells. CECs loss and dysfunction, resulting from inflammation, accidental damage during cataract surgery or as an inherited condition, can lead to progressive corneal swelling and formation of epithelial bullea, causing severe pain and even blindness.

Numerous in vitro and in vivo studies concerning corneal endothelium protection and proliferation have recently been conducted1–3. However, the improvement of strategies to overcome the corneal epithelial barrier and blood-aqueous humor barrier for targeted drug delivery to the corneal endothelium remains a major challenge. Corneal endothelium equivalents now offer a good opportunity for toxicological screening of drugs and investigation of pathological corneal endothelium conditions. Also, corneal endothelium equivalents could be substitutes for experiment animals for in vivo studies. These could also be a potential source of grafts for corneal endothelial keratoplasty and might solve the problem of supply shortage of donor corneas4.

The construction of corneal endothelium equivalents requires recruitment of active CECs and a scaffold. Bioengineered corneal endothelium still faces many difficulties, including the lack of source of CECs and the failure of scaffolds to meet clinical demands such as biocompatibility, transparency, and mechanical strength.

Limited accessibility and proliferative ability of primary human CECs make in vitro studies of these cells difficult. Human corneal endothelial cell line could be steadily passaged in vitro5. B4G12 cells, one of the two clonal subpopulations, showed good similarities to their natural counterparts, and thus could be a promising substitute candidate for human CEC5. But application of B4G12 cells in corneal endothelium equivalent construction still requires further analysis regarding bio-safety and pump function in vivo.

At present all the scaffolds can be classified into natural and synthetic materials. Natural membranes such as amniotic membranes6,7 or Descemet's membranes8,9 are too thin to handle, while synthetic polymers may have poor graft-host integration and biocompatibility10. Due to its unique extracellular matrix organization, the cornea itself came to be an ideal candidate. The porcine cornea appears to be particularly attractive because of its anatomic similarity to the human cornea11. Different methods have been tried to acquire decellularized porcine corneal scaffold over many years. Although methods of tissue decellularisation have been used in a variety of applications, such as adipose, skeleton muscle, urinary bladder and cardiovascular tissue engineering and regeneration12–16, but there are not many reports of their use to produce an acellular corneal scaffold. Fu et al17 acquired an acellular porcine corneal matrix scaffold using Triton X-100, but they did not achieve complete cell clearance by this protocol. Choi et al18 created decellularized human corneal stroma scaffolds using Triton X-100, which was cell-free and similar to natural cornea in structure, mechanical toughness and optical characters. But the bioengineered corneal endothelium still has to rely on human donor corneas, which are not easily available. An acellular porcine corneal matrix (APCM) was recently created using sodium dodecyl sulphate (SDS) according to the protocol developed in our laboratory19–21. The mechanical, ultrastructural and biological properties of this scaffold were studied in detail, and APCM proved to be a suitable scaffold for corneal equivalent construction19–24.

In this study, the bio-safety and pump function of BG12 cells were tested in vivo through a rat corneal endothelial deficiency model. B4G12 and APCM were used to show the possibility of constructing a corneal endothelium equivalent under serum-free condition for in vitro study.

Material & Methods

This study was conducted in the Key Laboratory of Cardiovascular Remodeling and Function Research, Qilu Hospital, Shandong University.

Adult porcine eyes were obtained from a local slaughterhouse (Jinan Welcome Food Co., Ltd, Jinan, PR China) within 3 h post-mortem, and subjected to decellularization procedure within 1 h of acquisition.

The chemicals used were SDS, human recombinant bFGF, chondroitin-6 sulphate, laminin, trypsin-EDTA, alizarin red S, goat serum, and DAPI (Sigma, USA), human endothelial SFM, proteinase inhibitor and rabbit anti-human ZO-1 Mab (Invitrogen, USA), carboxyfluorescein diacetate, succinimidyl ester (Beyotime, China), mouse anti-human Na+/K+ ATPase (Santa Cruz, USA), optimal cutting temperature compound, goat anti-rabbit IgG conjugated with FITC and goat anti-mouse IgG conjugated with FITC (Beijing Zhongshan, China). Microplate reader was purchased from InTec Reader (USA), slit lamp microscope and inverted light microscope from Zeiss (Germany), and fluorescence microscope was purchased from Olympus (Japan). In vitro specular microscope was purchased from Alcon (USA).

Animals: Twenty Sprague Dawley (SD) rats (Center for New Drugs Evaluation of Shandong University, Jinan, PR China) weighing 250-350 g were used for animal transplantation. The research protocol was approved by the ethical committee for animal experiments of Qilu hospital, Shandong University, and all animals were treated according to the national and international rules of animal welfare, including the ARVO Statement for the Use of Animals in Ophthalmic and Vision Research.

Decellularization of porcine corneas: Fresh porcine eyes were washed with 1 per cent penicillin-streptomycin in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.2-7.4) and the corneas were dissected under sterile condition. Briefly, a single cornea was cut into a 10 mm diameter button with a trephine. Corneal buttons were then immersed in 0.5 per cent (wt./vol.) SDS solution with a solvent/tissue mass ratio of 20:1 (vol. /wt.). They were placed on an orbital shaker for 24 h at 4 °C and rinsed 8 times in sterile PBS for 16 h. Finally, APCMs were washed 3 times in sterile PBS supplemented with 200 U/ml penicillin and 200 U/ml streptomycin for 3 h, freeze-dried at -20 °C for 12 h, air-dried at room temperature for 3 h in a biological safety cabinet, and stored at –20 °C before use. All steps were conducted under sterile conditions.

Cell culture: The human corneal endothelial cell line was first created in 2000, and detailed information about two cell subpopulations was also investigated22. B4G12 cells (generously provided by Monika Valtink as a gift) were cultured according to the previous protocol22,23. Briefly, B4G12 cells were cultured in human endothelial-SFM supplemented with 10 ng/ml human recombinant bFGF in T25 culture flasks coated with 1 mg chondroitin-6 sulphate and 10 μg laminin. Cells were passaged using 0.05 per cent trypsin-0.02 per cent EDTA at 37 °C for 1 min. Enzyme activity was quenched by proteinase inhibitor.

Cytotoxicity of extractable materials: Each scaffold was extracted using 5 ml B4G12 culture medium at 37 °C for 48 h. A cell suspension of B4G12 was added to 96-well plates at a density of 8×103/well and cultured with the leaching liquid (the experimental group, n=6) or the normal medium (control group, n=6) respectively. Cells were cultured at 37 °C and 5% CO2. After 1, 3, 5, and 7 days, the proliferation activity of the cells was quantitatively determined by MTT assay19. The optical density (OD) of absorbance at 490nm was measured by a microplate reader. Differences in the OD value between experimental and control groups were statistically analyzed using one-way ANOVA.

Anterior chamber injection of B4G12 cells in the rat model of corneal endothelium deficiency: The SD rat model of corneal endothelium deficiency was used for B4G12 cell transplantation to determine their bio-safety and pump function in vivo. The procedure was conducted according to the previous method24,25. Briefly, SD rats were anaesthetized with intraperitoneal injection of 10 per cent chloral hydrate (0.3 ml/100 g). The cornea of the right eye was treated for 15 sec by immediately placing a brass dowel that had been cooled in liquid nitrogen on the surface. This procedure was repeated twice, each time allowing the eyeball to thaw by saline irrigation prior to refreezing. The anterior chamber was carefully washed three times with saline through a 0.5 mm width paracentesis. B4G12 cells were labelled with a kind of fluorescent dye called carboxyfluorescein diacetate, succinimidyl ester (CFDA SE). Then 8.5×104 cells (for a rat cornea of 6mm in diameter corresponding to a seeding density 3000 cells/mm2, n=8) were injected into the anterior chamber of each right eye, and cryoinjury only served as the control group (n=8). Both test and control groups of rats were kept in the eye-down position for 24 h under deep anaesthesia. Each surgical eye was checked and photographed with a slit lamp microscope three times a week for one month. Post-operative rat eyes were removed and the corneas were viewed as whole-mounts under a fluorescence microscope to examine the CFDA SE fluorescence. Then the corneas were fixed in formaldehyde and processed for paraffin embedding. Sections of 5 μm were subjected to haematoxylin eosin (HE) staining and observed under a light microscope.

Construction of human corneal endothelium equivalents in vitro: One mm thick, 8 mm diameter APCM lamellae containing Descemet's membrane were prepared and soaked in culture medium at 37 °C for 24 h before cell seeding. They were then placed in a 24-well plate, with the denuded Descemet's membrane facing up. B4G12 cells in 100 μl culture medium were gently seeded at a density of 1.5×105 cells per cm2 for each scaffold and allowed to adhere for 4 h before being completely immerged in B4G12 culture medium. These were then cultured for 2 wk.

Morphological and histological analysis of corneal endothelium equivalents: The density of the corneal endothelium equivalent was calculated in ten samples after two weeks of organ culture. The surface of corneal endothelium equivalents was stained with trypan blue and alizarin red S. The endothelial side was observed under an inverted microscope. Cell density was determined by counting individual cells in a 0.01 mm2 area. Three different fields were randomly chosen for each sample. Cell density was expressed as the mean number of cells per mm2±SD.

For histological observation, the constructed corneal endothelium equivalents were fixed in 4 per cent paraformaldehyde and processed for paraffin embedding. Five micrometers sections were cut and stained with HE.

Immunofluorescent staining: Fresh corneal endothelium equivalents were embedded in Optimal Cutting Temperature Compound, frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at -70 °C. Primary antibodies were rabbit anti-human ZO-1 Mab (1:20) and mouse anti-human Na+/K+ ATPase (1:50). Secondary antibodies were goat anti-rabbit IgG conjugated with FITC (1:100) and goat anti-mouse IgG conjugated with FITC (1:100). Samples were incubated with 10 per cent (wt/wt) goat serum in PBS for 30 min at room temperature before being exposed to primary and secondary antibodies. Samples were incubated with primary antibodies at 4 °C overnight and secondary antibodies at 37 °C for 30 min. A negligible background was observed for controls (primary antibodies omitted). Cell nuclei were counterstained with DAPI. Fluorescence was observed using an Olympus fluorescence microscope.

Pump function analysis of corneal endothelium equivalents: The pump function of endothelium equivalents was analyzed by corneal swelling assays27. Briefly, the equivalents were mounted in pairs in an in vitro specular microscope. These were perfused with glutathione bicarbonated Ringer's (GBR) solution (6.521 g/l NaCl, 0.358 g/l KCl, 0.115 g/l CaCl2, 0.159 g/l MgCl2, 0.103 g/l NaH2PO4, 2.454 g/l NaHCO3, 0.9 g/l glucose, and 0.92 g/l reduced glutathione). Temperature and pressure were maintained at 37 °C and 15 mmHg. After perfusion with GBR for 15 min, the equivalents were switched to calcium-free GBR for 1 h, to disrupt cell junctions and induce corneal swelling. After 1 h, the equivalents were switched back to either GBR alone for controls or to GBR containing Na+/K+ ATPase inhibitor ouabain. Changes in corneal thickness were then measured at various time points with an ultrasound pachymeter. Corneal swelling was reported as the change in equivalents’ thickness relative to the initial value for each at the time that ouabain was added. Reported values represent the average of six independent experiments with probabilities calculated using SPSS 17.0 (USA), P<0.05 was considered significant. Fresh porcine corneas and APCM alone were used as normal controls and blank controls, respectively.

Results

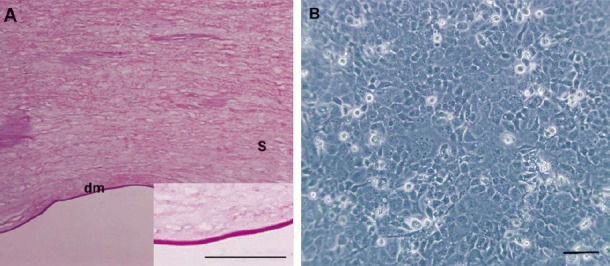

Morphology of APCM and B4G12 cells: Histological cross-section confirmed that the major immunogenic porcine corneal keratocytes and endothelial cells were completely removed from the stroma and the Descemet's membrane, and the matrix architecture was well preserved (Fig. 1A).

Fig. 1.

Microscopic images of APCM and B4G12 cells. (A) HE staining showed that the acellular porcine corneal matrix was cell-free and the collagen structure was preserved. A high magnification image of APCM is shown in the lower right corner. (B) Monolayer of B4G12 cells formed after 72 h of sub-cultivation. Scale bars: A=50 μm, B=100 μm. dm= Descemet's membrane; s= stroma.

After 72 h of sub-cultivation, B4G12 cells had formed a dense monolayer of tightly packed cells with polygonal morphology (Fig. 1B), which was similar to native corneal endothelial cells.

MTT assay: MTT assay was used to test the cytotoxicity of APCM. The results showed that the mean OD values of the experimental group on day 1, 3, 5, 7 were 0.646, 1.114, 1.215, 1.258, respectively, having no statistical differences (P>0.05) with those of the control group at each corresponding point 0.66, 1.122, 1.221 and 1.295. This meant that there was little residual toxic SDS in thoroughly-washed APCMs and the proliferation of B4G12 cells was not influenced (data not shown).

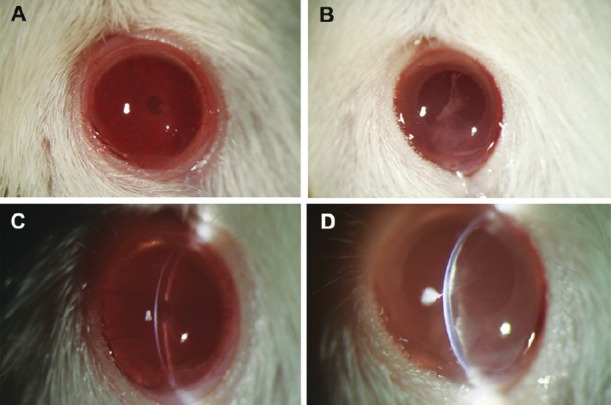

Bio-safety and function analysis of B4G12 cells in vivo: B4G12 cells were labelled with CFDA SE according to the manufacture's instruction before the surgery. Representative photographs of the anterior segment showed that corneas in B4G12 cells-injection group were clear with the anterior chamber clearly visible, while in the cryoinjury only group the corneas were opaque with stromal edema (Fig. 2A and B). The slit images showed clearly that the corneas in the cryoinjury only group were about twice the thickness of those in B4G12 cells-injection group one month after surgery (Fig. 2C and D).

Fig. 2.

Representative corneal photos after the surgery. (A) Cornea in the B4G12 cell-injection group was clear, the anterior chamber and the iris were clearly visible. (B) In contrast, cornea in the cryoinjury only group was opaque. (C) The slit image of the cornea in the B4G12 cell-injection group showed that the cornea was at normal thickness, and the endothelium surface was smooth. (D) The slit image of the cornea in the cryoinjury only group showed that the cornea was swollen and there was lamellar keratic precipitate on Descemet's membrane.

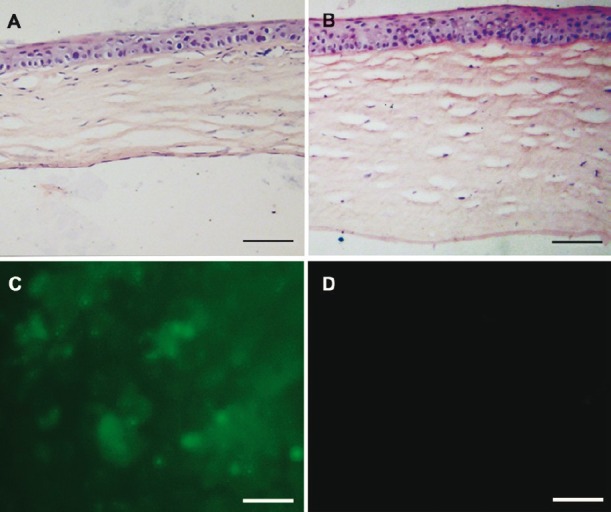

HE staining showed a monolayer of cells on Descemet's membrane in the B4G12 cell-injection group, whereas no cells could be seen on Descemet's membrane in the cryoinjury only group (Fig. 3A and B). A florescence signal was detected in corneal flat mounts in the B4G12 cell-injection group, indicating that their origin was from B4G12 cells not host corneal endothelial cells (Fig. 3C). There was no evidence of mononuclear cell accumulation or neoplasm from B4G12 cells around Descemet's membrane, suggesting no immunological reaction or oncogenicity of B4G12 cells in this model.

Fig. 3.

Histological examination of the corneas after the surgery. (A) HE-stained cross-section showed that Descemet's membrane was covered by cell monolayer in the B4G12 cell-injection group. (B) No cells were present on Descemet's membrane in the cryoinjury only group. Note that the corneal stroma was much thicker than that in the B4G12 cell-injection group. (C) Fluorescence microscopy confirmed that cells covering the Descemet's membrane in the B4G12 cell-injection group were CFDA SE-positive. (D) No signal was detected from the corneas of the cryoinjury only group. Scale bars: 100 μm.

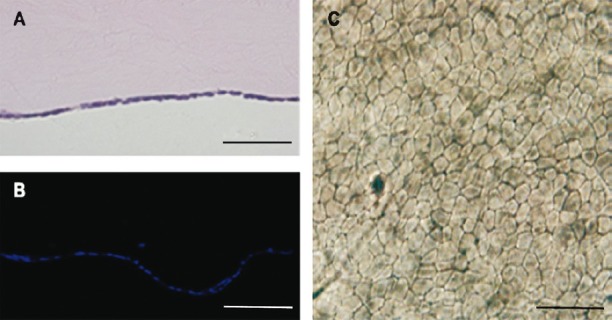

Characterization of constructed corneal endothelium equivalents: The human corneal endothelium equivalents were efficiently constructed with B4G12 cells and APCM. The initial seeding density (1.5×105 cells/cm2) assured that the cells formed a monolayer which had covered the Descemet's membrane of APCM after 2 wk (Fig. 4A). Staining of cell nuclei (DAPI staining) also indicated that cells were only present on Descemet's membrane and that the scaffold was free of keratocytes in the stroma (Fig. 4B).

Fig. 4.

Histological analysis of the corneal endothelium equivalents. (A) HE staining showed there was a monolayer of cells covering the Descemet's membrane of the APCM. (B) DAPI staining confirmed the cell coverage of the Descemet's membrane of the APCM. (C) Trypan blue and alizarin red S co-staining showed the B4G12 cells were alive and clearly delineated the cell boundaries. Scale bars: 50 μm.

Dual staining of corneal endothelium with trypan blue and alizarin red S is widely used for delineation of living corneal endothelial cells. As shown in Fig. 4C, the result revealed complete cell coverage. Most B4G12 cells stayed alive after being cultured on APCM and the dye-lake reaction showed a clear outline of the margins of B4G12 cells. The mean cell density of 10 corneal endothelium equivalents was 2061±344 cells/mm2 (range 1389 to 2689 cells/mm2, n=30)

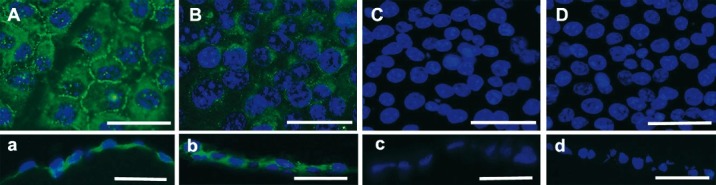

Immunofluorescent localization of ZO-1, a tight-junction associated protein, was used to check whether the cells formed a closed monolayer. The result revealed that this protein accumulated at cell boundaries, suggesting that B4G12 cells could form a closed monolayer on APCM (Fig. 5A and a). The primary role of corneal endothelium is to keep the relative dehydration state of cornea stroma, so the presence of Na+/K+ ATPase, a protein complex responsible for the pumping function was also detected. A positive signal was detected between cell nuclei (Fig. 5B and b). These two proteins were expressed in a similar pattern to native B4G12 cells on their natural substrate.

Fig. 5.

Immunofluorescent determination for ZO-1 and Na+/K+ ATPase. (A and a) ZO-1 was mainly expressed at the cell borders of corneal endothelium equivalents. (B and b) Na+/K+ ATPase was detected in the cell plasma and membrane of corneal endothelium equivalents. (C and c) Negative control in which the primary antibody was omitted for ZO-1. (D and d) Negative control in which the primary antibody was omitted for Na+/K+ ATPase. A, B, C and D are plane views of corneal endothelium equivalents and a, b, c and d are corresponding cross-section views. Scale bars: 50 μm.

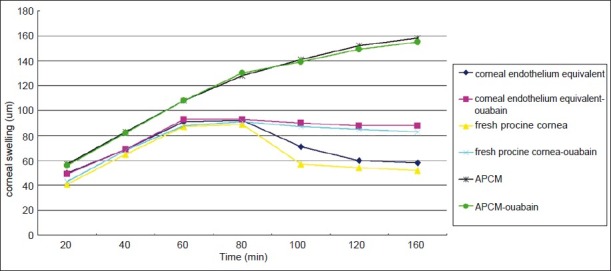

Having confirmed expression of Na+/K+ ATPase in constructed human corneal endothelium equivalents, corneal swelling assay was performed to determine the pump function. Changes of corneal thickness were compared with fresh porcine corneas denuded of epithelium. Calcium-free GBR solution transiently caused corneal swelling and then it was switched back to GBR with or without Na+/K+ ATPase inhibitor ouabain. As shown in Fig. 6, calcium-free GBR solution initialized corneal swelling after 20 min perfusion. The corneal equivalents continued to swell after GBR solution was switched back for both of equivalent group and equivalent-ouabain group, but the corneas swelled to a much greater degree in the latter group. The average increase of the corneal thickness in the equivalent group after 100 min was 63 versus 89 μm for that of the equivalent-ouabain group, and the difference was statistically significant (P<0.05). The result showed that treatment with ouabain dramatically affected corneal thickness of the equivalents that were constructed. This changing pattern was similar to that of fresh porcine corneas denuded of epithelium. In contrast, APCM alone kept swelling when incubated in GBR solution both in the presence of calcium or ouabain. These findings indicated that the B4G12 cells formed a monolayer having CEC-like pump function on APCM with adequate transport activity.

Fig. 6.

Pump function analysis of corneal endothelium equivalents by corneal swelling assay. Changes of corneal thickness were compared with fresh porcine corneas denuded of epithelium and APCM itself. Each value is the mean change of corneal thickness ± SD. Calcium free GBR solution could induce corneal swelling in fresh cornea group, APCM group and corneal endothelium equivalent group. When it was switched back to normal GBR solution, the corneal swelling regressed in both of fresh cornea and corneal endothelium equivalent group, but not in APCM group. Addition of ouabain to GBR solution dramatically inhibited the regression of corneal swelling in fresh cornea and corneal endothelium equivalent group by interfering with the pump-function of Na+/K+ ATPase.

Discussion

Corneal organ culture serves as a useful model that allows research to be done under conditions that are relatively similar to the in vivo state without being interfered with by the ocular surface barrier and the blood-aqueous humour barrier. But due to the lack of donor corneas and limited proliferative capacity of CECs, corneal organ culture is mostly limited to corneal epithelial research.

Tissue-engineering technology now provides a new opportunity by constructing artificial corneal endothelium equivalents for ex vivo studies and potential clinical use. The construction of tissue-engineered corneal endothelium involves two major elements: seed cells and scaffold. The great advantage of human corneal endothelial cell line is the easy accessibility compared to primary CECs. Human CECs are in the post-mitotic state in vivo, which makes studies of cultured endothelial cells in vitro a big challenge. The human corneal endothelial cell line was first constructed in 20005, and two clonal cell lines B4G12 and H9C1 were separated from this cell population in 200822. This B4G12 cell line was chosen as a substitute for primary human CECs because it was found to have the features very close to primary human CECs and could serve as a good model22,23. Another merit of this cell line is that it is cultured in a serum-free medium. The cornea is an avascular organ, which is not physically in contact with serum. But according to the common protocol, primary CECs need to be cultured under a serum-containing condition28. The impact of serum on cell morphology or even cell physiology is hard to predict, which may affect the reliability of the results, especially for toxicological screening of drugs and investigation of pathological corneal endothelium conditions. Thus, a serum-free system is necessary for corneal endothelium organ culture29,30.

The similarity in function to native cells and bio-safety have always been critical in choosing candidate seed cells for artificial organ construction. Thus in vivo B4G12 cells transplantation was conducted to see if these were appropriate candidate cells. Our results demonstrated that B4G12 cells behaved well without causing an immunological reaction or showing their oncogenicity in our rat model.

Various tissue-engineered corneal endothelia have been constructed using different scaffolds. The APCM scaffold used in this study proved to be free of native cell components and similar to natural corneal stroma regarding transparency, biocompatibility and mechanical strength as shown in our previous reports19–21. In this study, it was shown that APCM could support the growth of B4G12 cells and expression of the tight junction protein ZO-1 and functional pump protein Na+/K+ ATPase. It was noticed that some sections of the constructed corneal endothelium equivalents were multilayered, which was probably due to cell clumps generated during the seeding procedure. Filters with the proper size could help to get rid of the clumps in order to get a strictly monolayer endothelium. A few groups have conducted vital pump function detection of their tissue-engineered corneal endothelia18,31–33. The results of the corneal swelling assay in this study not only demonstrated that the constructed corneal endothelium equivalents had the pump function in vitro, but also further proved that the collagen structure of the APCM was preserved after the decellularization process and the hydration was reversible, just as in the natural cornea.

In conclusion, our study demonstrated that APCM combined with B4G12 could make corneal endothelium equivalents similar to native corneal endothelium in both morphology and function, which might serve as good models of corneal endothelium organ culture for ex vivo studies.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Monika Valtink for generously providing the B4G12 cell line and cell culture assistance, Dr Edward C. Mignot, formerly of Shandong University, for linguistic advice.

References

- 1.Ben-Eliahu S, Tal K, Milstein A, Levin-Harrus T, Ezov N, Kleinmann G. Protective effect of different ophthalmic viscosurgical devices on corneal endothelium during severe phacoemulsification model in rabbits. Ophthalmic Surg Lasers Imaging. 2011;42:152–6. doi: 10.3928/15428877-20110125-01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jee DH, Kim HS. The effect of CF gas on corneal endothelial cells in rabbits. Jpn J Ophthalmol. 2010;54:602–8. doi: 10.1007/s10384-010-0884-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Landry H, Aminian A, Hoffart L, Nada O, Bensaoula T, Proulx S, et al. Corneal endothelial toxicity of air and SF6. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2011;52:2279–86. doi: 10.1167/iovs.10-6187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eye Banking Statistical Report. Washington, DC: Eye Bank Association of America; 1999. Eye Bank Association of America. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bednarz J, Teifel M, Friedl P, Engelmann K. Immortalization of human corneal endothelial cells using electroporation protocol optimized for human corneal endothelial and human retinal pigment epithelial cells. Acta Ophthalmol Scand. 2000;78:130–6. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0420.2000.078002130.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wencan W, Mao Y, Wentao Y, Fan L, Jia Q, Qinmei W, et al. Using basement membrane of human amniotic membrane as a cell carrier for cultivated cat corneal endothelial cell transplantation. Curr Eye Res. 2007;32:199–215. doi: 10.1080/02713680601174165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ishino Y, Sano Y, Nakamura T, Connon CJ, Rigby H, Fullwood NJ, et al. Amniotic membrane as a carrier for cultivated human corneal endothelial cell transplantation. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2004;45:800–6. doi: 10.1167/iovs.03-0016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shimmura S, Miyashita H, Konomi K, Shinozaki N, Taguchi T, Kobayashi H, et al. Transplantation of corneal endothelium with Descemet's membrane using a hyroxyethyl methacrylate polymer as a carrier. Br J Ophthalmol. 2005;89:134–7. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2004.050591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lange TM, Wood TO, McLaughlin BJ. Corneal endothelial cell transplantation using Descemet's membrane as a carrier. J Cataract Refract Surg. 1993;19:232–5. doi: 10.1016/s0886-3350(13)80947-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Koizumi N, Sakamoto Y, Okumura N, Okahara N, Tsuchiya H, Torii R, et al. Cultivated corneal endothelial cell sheet transplantation in a primate model. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2007;48:4519–26. doi: 10.1167/iovs.07-0567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kampmeier J, Radt B, Birngruber R, Brinkmann R. Thermal and biomechanical parameters of porcine cornea. Cornea. 2000;19:355–63. doi: 10.1097/00003226-200005000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bhrany AD, Beckstead BL, Lang TC, Farwell DG, Giachelli CM, Ratner BD. Development of an esophagus acellular matrix tissue scaffold. Tissue Eng. 2006;12:319–30. doi: 10.1089/ten.2006.12.319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Daniel J, Abe K, McFetridge PS. Development of the human umbilical vein scaffold for cardiovascular tissue engineering applications. ASAIO J. 2005;51:252–61. doi: 10.1097/01.mat.0000160872.41871.7e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Flynn L, Semple JL, Woodhouse KA. Decellularized placental matrices for adipose tissue engineering. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2006;79:359–69. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.30762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McFetridge PS, Bodamyali T, Horrocks M, Chaudhuri JB. Endothelial and smooth muscle cell seeding onto processed ex vivo arterial scaffolds using 3D vascular bioreactors. ASAIO J. 2004;50:591–600. doi: 10.1097/01.mat.0000144365.22025.9b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bolland F, Korossis S, Wilshaw SP, Ingham E, Fisher J, Kearney JN, et al. Development and characterisation of a full-thickness acellular porcine bladder matrix for tissue engineering. Biomaterials. 2007;28:1061–70. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2006.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fu Y, Fan X, Chen P, Shao C, Lu W. Reconstruction of a tissue-engineered cornea with porcine corneal acellular matrix as the scaffold. Cells Tissues Organs. 2010;191:193–202. doi: 10.1159/000235680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Choi JS, Williams JK, Greven M, Walter KA, Laber PW, Khang G, et al. Bioengineering endothelialized neo-corneas using donor-derived corneal endothelial cells and decellularized corneal stroma. Biomaterials. 2010;31:6738–45. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pang K, Du L, Wu X. A rabbit anterior cornea replacement derived from acellular porcine cornea matrix, epithelial cells and keratocytes. Biomaterials. 2010;31:7257–65. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.05.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Du L, Wu X. Development and characterization of a full-thickness acellular porcine cornea matrix for tissue engineering. Artif Organs. 2011;35:691–705. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1594.2010.01174.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Du L, Wu X, Pang K, Yang Y. Histological evaluation and biomechanical characterisation of an acellular porcine cornea scaffold. Br J Ophthalmol. 2011;95:410–4. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2008.142539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Valtink M, Gruschwitz R, Funk RH, Engelmann K. Two clonal cell lines of immortalized human corneal endothelial cells show either differentiated or precursor cell characteristics. Cells Tissues Organs. 2008;187:286–94. doi: 10.1159/000113406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gotze T, Valtink M, Nitschke M, Gramm S, Hanke T, Engelmann K, et al. Cultivation of an immortalized human corneal endothelial cell population and two distinct clonal subpopulations on thermo-responsive carriers. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2008;246:1575–83. doi: 10.1007/s00417-008-0904-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Minkowski JS, Bartels SP, Delori FC, Lee SR, Kenyon KR, Neufeld AH. Corneal endothelial function and structure following cryo-injury in the rabbit. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1984;25:1416–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Van Horn DL, Sendele DD, Seideman S, Buco PJ. Regenerative capacity of the corneal endothelium in rabbit and cat. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1977;16:597–613. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Taylor MJ, Hunt CJ. Dual staining of corneal endothelium with trypan blue and alizarin red S: importance of pH for the dye-lake reaction. Br J Ophthalmol. 1981;65:815–9. doi: 10.1136/bjo.65.12.815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stern ME, Edelhauser HF, Pederson HJ, Staatz WD. Effects of ionophores X537a and A23187 and calcium-free medium on corneal endothelial morphology. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1981;20:497–508. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhu C, Joyce NC. Proliferative response of corneal endothelial cells from young and older donors. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2004;45:1743–51. doi: 10.1167/iovs.03-0814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hempel B, Bednarz J, Engelmann K. Use of a serum-free medium for long-term storage of human corneas. Influence on endothelial cell density and corneal metabolism. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2001;239:801–5. doi: 10.1007/s004170100364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bednarz J, Doubilei V, Wollnik PC, Engelmann K. Effect of three different media on serum free culture of donor corneas and isolated human corneal endothelial cells. Br J Ophthalmol. 2001;85:1416–20. doi: 10.1136/bjo.85.12.1416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Madden PW, Lai JN, George KA, Giovenco T, Harkin DG, Chirila TV. Human corneal endothelial cell growth on a silk fibroin membrane. Biomaterials. 2011;32:4076–84. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.12.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Proulx S, Audet C, Uwamaliya J, Deschambeault A, Carrier P, Giasson CJ, et al. Tissue engineering of feline corneal endothelium using a devitalized human cornea as carrier. Tissue Eng Part A. 2009;15:1709–18. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2008.0208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gao X, Liu W, Han B, Wei X, Yang C. Preparation and properties of a chitosan-based carrier of corneal endothelial cells. J Mater Sci Mater Med. 2008;19:3611–9. doi: 10.1007/s10856-008-3508-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]