Abstract

Anaplastic thyroid carcinoma is the least common but most lethal of thyroid cancers. All patients are classified as stage IV, with the primary lesion restricted to the thyroid gland in stage IVA; locoregional lymph nodes may exist in IVA/IVB; and IVC disease is defined by distant metastases. Prognosis is highly dependent on disease extent at presentation, and staging and establishing a plan of care must be accomplished quickly. Although almost all studies are biased due to their retrospective nature, the most important factors associated with longer survival are completeness of surgical resection (achievable in only a minority of patients) and high-dose (>40 Gy) external beam radiotherapy (preferably intensity modulated radiation therapy). Recent reports suggest that a multimodal approach (surgery, radiation, and chemotherapy) is beneficial. Given the high lethality even with apparent local disease, combination systemic therapy (cytotoxics and/or targeted agents) may improve outcomes in stage IVA/IVB patients. Newer, more effective drug combinations are urgently needed for IVC patients who want aggressive therapy. A candid discussion of the prognosis and management options, including palliative care/hospice, should be held with the patient and caregiver as soon as possible after diagnosis to clarify the patient's preference and expectations. Prospective multicenter clinical trials, incorporating molecular analyses of tumors, are required if we are to improve survival in anaplastic thyroid carcinoma.

Accreditation and Credit Designation Statements.

The Endocrine Society is accredited by the Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education to provide continuing medical education for physicians. The Endocrine Society has achieved Accreditation with Commendation.

The Endocrine Society designates this Journal-based CME activity for a maximum of 1 AMA PRA Category 1 Credit™. Physicians should claim only the credit commensurate with the extent of their participation in the activity.

Learning Objectives

Upon completion of this educational activity, participants should be able to:

List 5 tumors in the differential diagnosis of anaplastic thyroid carcinoma.

Identify genes and proteins commonly mutated, overexpressed or underexpressed in anaplastic thyroid cancer.

Summarize the optimal management approach for each stage of anaplastic thyroid cancer.

Use tumor stage and median survival times in discussing therapeutic goals with patients.

Target Audience

This Journal-based CME activity should be of substantial interest to endocrinologists.

Disclosure Policy

Authors, editors, and Endocrine Society staff involved in planning this CME activity are required to disclose to The Endocrine Society and to learners any relevant financial relationship(s) of the individual or spouse/partner that have occurred within the last 12 months with any commercial interest(s) whose products or services are discussed in the CME content. The Endocrine Society has reviewed all disclosures and resolved or managed all identified conflicts of interest, as applicable. Disclosures for JCEM Editors are found at http://www.endo-society.org/journals/Other/faculty_jcem.cfm.

Robert Smallridge, M.D., and the Editor-in-Chief, Leonard Wartofsky, M.D., reported no relevant financial relationships.

Endocrine Society staff associated with the development of content for this activity reported no relevant financial relationships.

Acknowledgement of Commercial Support

This activity is not supported by grants, other funds, or in-kind contributions from commercial supporters.

Privacy and Confidentiality Statement

The Endocrine Society will record learner's personal information as provided on CME evaluations to allow for issuance and tracking of CME certificates. No individual performance data or any other personal information collected from evaluations will be shared with third parties.

Method of Participation

This Journal-based CME activity is available in print and online as full text HTML and as a PDF that can be viewed and/or printed using Adobe Acrobat Reader. To receive a maximum of 1 AMA PRA Category 1 Credit™ participants should review the learning objectives and disclosure information; read the article and reflect on its content; then go to http://jcem.endojournals.org and find the article, click on CME for Readers, and follow the instructions to access and complete the post-activity test questions and evaluation achieving a minimum score of 70%.. If learners do not achieve a passing score of 70%, they have the option to change their answers and make additional attempts to achieve a passing score. Learners also have the option to clear all answers and start over.

To complete this activity, participants must:

Have access to a computer with an internet connection.

Use a major web browser, such as Internet Explorer 7+, Firefox 2+, Safari, Opera, or Google Chrome; in addition, cookies and Javascript must be enabled in the browser's options.

The estimated time to complete this activity, including review of material, is 1 hour. If you have questions about this CME activity, please direct them to education@endo-society.org.

Activity release date: August 2012

Activity expiration date: August 2014

The Case

A 61-yr-old woman had recent onset of a painful neck mass, hoarseness, and dysphagia. A thyroid ultrasound showed a 5.6 × 4.1 × 4-cm right thyroid mass and a 1.0-cm left thyroid nodule; fine-needle aspiration revealed a few markedly atypical cells. She underwent a right neck exploration, biopsy, and tracheostomy. A “rock hard” mass was adherent to the trachea, invaded the jugular vein, and involved the prevertebral fascia, and abnormal lymph nodes were present. Pathology showed a spindle cell pattern, immunostains were positive for keratin and negative for thyroglobulin, and serum thyroglobulin and thyroid peroxidase antibodies were negative.

Anaplastic thyroid carcinoma (ATC) was diagnosed, and 2 wk later the patient began intensity modulated radiation therapy (IMRT) twice daily, 5 d/wk (7200 cGy). She had weight loss but did not require a feeding tube, and her Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status was 1. Her tumor tissue stained positive for the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), and her oncologist started cetuximab (an EGFR monoclonal antibody) therapy. She was referred for a second opinion, and available clinical trials were discussed.

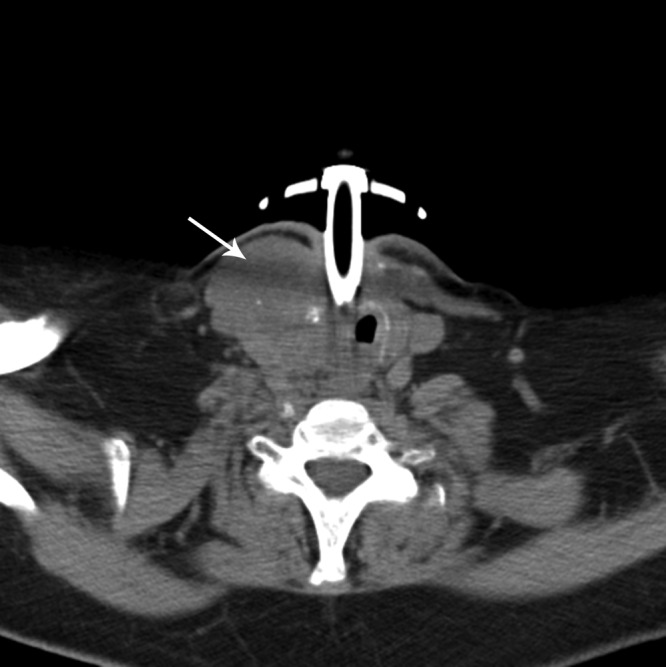

A positron emission tomography (PET)/computed tomography (CT) scan that was performed 3.5 wk after IMRT was started showed a hypermetabolic right neck mass [standardized uptake value (SUV) = 15.1], and a follow-up 3 months later showed that the mass had decreased to 3.4 cm and the SUV to 5.0. Two months later, the SUV was 3.8, and after another 3 months the SUV was 6 and the mass was 3.2 cm. However, 1 yr after IMRT was started, the mass had enlarged slightly to 3.7 cm, and the SUV was 9.8. No distant metastases were evident. Her oncologist discontinued cetuximab and started erlotinib. This therapy was stopped 3 months later due to local progression. Seventeen months after surgery, CT imaging showed that the mass was 4 cm with possible invasion (Fig. 1) but no systemic metastases. The patient was referred again for consideration of other options and was followed by the palliative care service. She enrolled in a clinical trial but developed acute respiratory complications and died of respiratory failure before its initiation.

Fig. 1.

Residual ATC in a 63-yr-old woman. The cervical mass was inseparable from the strap muscles, tracheal wall, and carotid sheath. Arrow indicates residual tumor mass.

Background

Frequency

Thyroid cancer has several histological types, each with its own characteristics, and includes differentiated forms (papillary, follicular, Hürthle cell), medullary, poorly differentiated, and ATC. Thyroid cancer in general is increasing in incidence and is now the fifth most common cause of cancer in women in the United States (1), the second most common in women in several Gulf Cooperation Council countries (Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, Qatar, United Arab Emirates) (2), and the most common in women in Korea (3). Fortunately, ATC is a rare cause of thyroid cancer and ranges from 0.6 to 9.8% (median, 3.8%) of all thyroid cancers across the world (4).

Presentation

ATC most commonly presents later in life and is more common in women (4–7). A recent review of 2822 cases found that 65.8% were female; the median and mean ages were 69 and 66.5 yr, respectively (range, 15–98 yr) (4). The median tumor size was 6.8 cm (range, 0.5–25 cm). ATC was associated with differentiated thyroid carcinoma (DTC) in 25% of cases (range: 3–52%) and presented with distant metastases in 41% (11–90%) (4).

The onset of locoregional symptoms was rapid and included an enlarging neck mass in 86% (range: 46–100%), hoarseness/dysphonia in 33% (16–58%), dysphagia in 38% (1–58%), dyspnea in 27% (4–44%), pain in 16% (9–32%), cough and hemoptysis each in 10%, and superior vena cava syndrome in 8% (5–12%) (4). Distant metastases (median percentage) were seen in lung (37.2%), mediastinum (25%), liver (10.1%), bone (6.4%), kidneys (5.3%), heart and adrenals (5.2%), and brain (4.4%) (4).

Causes of death were reported due to distant metastases in 51.5% (range: 12–68%), local complications in 23.7% (5–37%), or both 26.2% (25–51%) (4). In most studies, distant metastases strongly predicted mortality, whereas greater extent of surgery and higher dose radiotherapy predicted longer survival; less predictive factors included patient age, gender, and combination therapy (although recent studies using aggressive multimodal therapy hold some promise) (8).

Diagnosis and Therapeutic Strategies

Pathology

A diagnosis is urgently required to develop a treatment plan for this rapidly progressive tumor. Fine-needle aspiration may be unsuccessful due to extensive necrosis, in which case a core biopsy is necessary. The histotypes of ATC include giant cell, spindle cell, squamoid, and paucicellular variants, and the differential diagnosis should consider poorly differentiated and medullary thyroid cancers, lymphoma, sarcoma, metastatic lesions, and squamous cell carcinoma (either primary thyroid, or head/neck primary), and Riedel's thyroiditis. Immunohistochemistry may help because pancytokeratin and P53 are usually positive, whereas calcitonin and thyroglobulin are negative.

At the molecular level, ATC is highly pleiotropic, with multiple mutations of oncogenes and tumor suppressor genes (Table 1) as well as copy gains, aberrant microRNA expression, and epigenetic changes (5). A large number of proteins involved in numerous critical cellular functions are either over- or underexpressed (Table 2). Many of these genes and proteins are potential therapeutic targets for which drugs are in clinical trials for other malignancies. Pertinent to our case is the high frequency of EGFR overexpression, noted in 58–87% of anaplastic thyroid tumors (9–12). The EGFR antagonist, gefitinib, inhibited ATC tumor growth in vivo in a xenograft model (13, 14), whereas cetuximab decreased VEGF secretion but not cell proliferation in vitro (15). Three ATC cell lines with mutant BRAF (V 600E) also overexpressed EGFR and p-EGFR. BRAF inhibition alone had little effect, whereas the combination of a BRAF and EGFR inhibitor (cetuximab or gefitinib) synergistically inhibited cell proliferation (16).

Table 1.

| Gene | Frequency (no. of studies) |

|---|---|

| Axin | 82% (1) |

| TP53 | 55% (4) |

| Catenin β 1 | 38% (2) |

| BRAF | 26% (11) |

| Ras | 22% (6) |

| PIK3CA | 17% (3) |

| PTEN | 12% (2) |

| ALK | 11% (1) |

| APC | 9% (1) |

PIK3CA, Phosphoinositide-3-kinase, catalytic α; PTEN, phosphatase and tensin homolog; ALK, anaplastic lymphoma kinase; APC, adenomatous polyposis coli.

Table 2.

Over- and underexpressed proteins involved in critical cellular functions

| Function | Protein expression |

|

|---|---|---|

| Overexpressed | Underexpressed | |

| Transcription | PPAR-γ, HNF-1α, Id1, YBX1, HMG1(Y), Fra1, c-myc | NKX2–1, FOXE1, Pax8, CBX7 |

| Signaling | EGFR, CXR4, pAKt1, pERK, JAK/STAT | SOCS 1, 3, 5 |

| Mitosis | Aurora kinases, kα1 tubulin, topoisomerase-11 | TACC3 |

| Proliferation | MKI67, OEATC-1, RBBP4, SPAG9 | |

| Cell cycle | Cyclins D1, D3, E | p21, p27 |

| Apoptosis | IAPs, DJ-1, NF-κΒ, LCN2 | Bcl2, αB-crystallin |

| Adhesion | Β-catenin, ILK1, FAK | E-cadherin |

| Tumor suppressor | p53 | Rb, p16, PTEN |

[Reprinted from R. C. Smallridge and J. A. Copland: Anaplastic thyroid carcinoma: pathogenesis and emerging therapies. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol) 22:486–497, 2010 (6), with permission. © The Royal College of Radiologists.]

Imaging

Unlike patients with DTC, who have limited preoperative imaging, extensive imaging is imperative for patients with ATC to determine whether the tumor is resectable and whether distant metastases (e.g. lung, mediastinum, liver, bone, kidneys, heart, adrenal glands, and brain) are evident. PET/CT scans are recommended (17–19), but neck ultrasound and magnetic resonance imaging (brain, neck, and upper mediastinum) may also be helpful.

Staging

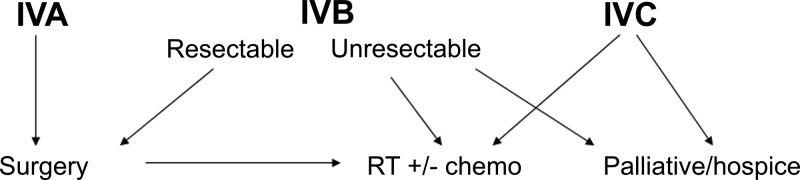

All ATCs are classified as stage IV, with the primary lesion limited to the thyroid in IVA disease and extrathyroidal extension in IVB lesions; locoregional nodal involvement may exist in IVA/IVB patients, but distant metastases define stage IVC disease. In eight series (19–26), the median (range) percentages of patients presenting with stage IVA, IVB, and IVC disease were 10.2% (0–19), 40.2% (15.8–70), and 45.8% (20–73.7), respectively. Median survival rates were 7.3, 3.9, and 1.7 months in the report by McIver et al. (22), and 1-yr survivals of 72.7, 24.8, and 8.2% were reported by Akaishi et al. (20). In the Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) database, median survival was 9 months if the tumor was confined, 6 months if adjacent structures were involved, and 3 months with further extension or distant metastases, whereas 1-yr survivals were 50, 27.6, and 7.4%, respectively (27). Therapeutic decisions and prognostic expectations both are improved by accurate staging and provide the medical team with the information necessary to explain all options to the patient (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Algorithm for recommended initial treatment of patients with ATC. RT, External beam radiotherapy (preferably IMRT); chemo (chemotherapy), cytotoxics and/or targeted agents.

Therapies

Surgery

Table 3 illustrates the effect of the extent of resection on survival. R0 (negative surgical margin), R1 (gross resection, positive microscopic margin), or “complete” resections resulted in substantially improved median and 1- to 3-yr survivals. All studies are biased because they are retrospective and not randomized to control for extent of disease, method/dose of radiotherapy, or chemotherapy (use/regimen). Nevertheless, extent of surgery consistently is a statistically favorable risk factor in 81% of 21 series reviewed (8). Ito et al. (21) found improved survival with IVB-a disease (most patients had at least an R2 resection) compared with IVB-b disease (most had no resection). Neoadjuvant therapy has also allowed some patients to convert from unresectable to resectable disease (28) and should be considered in selected patients.

Table 3.

Extent of surgical resection and outcomes in ATC

| First author (Ref.) | Outcome |

|---|---|

| Passler (23) | 3-yr survival = 50% vs. 4% (R0 vs. R1/R2 resection) |

| Haigh (47) | 2-yr survival = 75% vs. 6% (R0/R1 vs. less surgery) |

| Pierie (35) | 1-yr survival = 92% (complete resection), 35% (incomplete), 4% (none) |

| Kihara (48) | 1-yr survival = 75% (complete), 17% (incomplete), 0% (none) |

| Swaak-Kragten (24) | 1-yr survival = 32% (complete) vs. 9% (overall) |

| Ito (21) | Median survival = 9.6 vs. 4.0 months (IVB-aa vs. IVB-bb extent) |

| Akaishi (20) | 2-yr survival = 42.6% (R0, complete), 3.9% (incomplete), 0% (none) |

IVB-a = tumor involves soft tissue, larynx, trachea, esophagus, recurrent laryngeal nerve.

IVB-b = invasion of prevertebral fascia, encases carotid artery or mediastinal vessels.

Radiotherapy

Radiotherapy has been shown to reduce morbidity and mortality from locoregional complications and should be employed regardless of surgical resectability. Hyperfractionated and accelerated regimens have been used due to the rapid growth of ATC (28) but may increase toxicity (29, 30). IMRT is preferred if available (31, 32). Survival was statistically improved by radiotherapy in 71% of 18 studies reviewed (8). Results were best when doses of at least 40 Gy were employed. As examples, Wang et al. (33) saw survival improved from 3.2 to 11.1 months if more than 40 Gy was used, and Tan et al. (34) achieved more complete and partial responses. Pierie et al. (35) reported an improved 1-yr survival (54 vs. 17%) if more than 45 Gy was used, whereas median survival was increased from 1.7 to 5.4 months in another study if patients received more than 40 Gy (24). Palliative doses should also be considered to improve quality of life in patients with poor performance status or widespread disease.

Systemic therapy

Chemotherapy includes cytotoxic drugs and novel targeted agents. An early study showed that doxorubicin ± cisplatin was more effective than doxorubicin alone (36). Taxanes have shown biological activity against ATC in several studies (37–39). Foote et al. (40) have also demonstrated improved long-term survival for stage IVA/IVB patients with IMRT plus combination cytotoxic chemotherapy.

Several recent targeted agents have been tried in ATC, with some evidence of activity. Fosbretabulin, a microtubule-disrupting agent, produced stable disease in seven of 26 patients (41). Imatinib, an inhibitor of C-kit, platelet-derived growth factor receptor, and Bcr-Abl tyrosine kinases given to eight patients with ATC produced partial remissions of 120 and 694 d in two patients and stable disease in four (42). Several individual patients have had tumor reductions while taking erlotinib, an EGFR antagonist (43, 44), whereas one patient in a phase 1 trial of gefitinib and docetaxel had a partial response of skin metastases (45), and in a phase 2 study, one of five ATC patients on gefitinib had stable disease for at least 12 months (46).

Controversies/Areas of Uncertainty

Management of ATC is rife with uncertainties, and unresolved questions include: 1) should adjuvant radio- and/or chemotherapy be used in patients who have a small focus of ATC discovered after surgery for benign disease or DTC; 2) is radio-sensitizing dose/agent of chemotherapy beneficial during radiotherapy; 3) should adjuvant chemotherapy be used after an R0 or R1 resection plus radiotherapy; 4) if adjuvant therapy is employed, which agent(s) and for how long; 5) which chemotherapy regimens should be recommended in stage IVB unresectable (R2) disease; 6) is there a role for neoadjuvant radio- and/or chemotherapy in stage IVB unresectable disease to render patients resectable, and if so, are there criteria to predict who would be the best candidates; 7) what is the optimal frequency of imaging after initial therapy in patients with remission and in those with persistent disease; 8) what systemic therapies should be considered for stage IVC patients; and 9) what predictive factors will help patients in their decision making to pursue aggressive therapy vs. palliative/hospice care.

Barriers to Ideal Practice

Multiple features of ATC render it one of the most difficult malignancies to treat. First is the dramatic number of molecular derangements that activate multiple oncogenes and oncogenic pathways, silence tumor suppressor genes, and result in rapid proliferation time. The rarity of the tumor (approximately 0.4% of all cancers) renders it difficult to conduct clinical trials, and so knowledge of what regimens to use, and when, is rudimentary. Recent preclinical studies have identified some promising drug combinations (involving cytotoxics with targeted agents). Now that multicenter clinical trials for differentiated and medullary thyroid cancers have been successful, hopefully there will be a similar effort to conduct more trials in ATC. It will be important that patients are stratified into stages IVA, IVB, and IVC using similar imaging modalities to minimize bias, which exists in all published reports.

ATC is felt to evolve from DTC, at least in some patients, but which patients with DTC may later develop ATC is unknown. Perhaps as more comprehensive full genome analyses of tumors become readily available, a molecular signature predictive of increased risk of ATC will emerge. Such information may eventually direct the initial therapy and follow-up of the much larger population of DTC patients and reduce the risk of subsequent development of ATC.

Numerous other barriers exist, as discussed in the previous sections, and include unanswered questions regarding surgery, radiotherapy, and chemotherapy.

Returning to the Patient

Our patient's presentation was typical—a woman in her 60s with prominent locoregional symptoms. Her staging and initial surgery indicated that she had unresectable stage IVB disease, and she appropriately was offered and received high-dose IMRT to the head and neck. Her tumor tissue stained positively for EGFR, and she also received cetuximab, an EGFR monoclonal antibody used for recurrent or metastatic squamous cell head and neck cancer. There are no evidence-based trials to support one particular drug (or combination) for first- or second-line therapy for ATC, but there are preclinical data and limited case reports suggesting a biological effect of EGFR antagonists (9–14, 43–46) and synergy with a BRAF inhibitor in BRAF (V600E) mutant ATC cell lines (16).

The patient had a response, with progressive decrease in tumor size and SUV on PET/CT scans. Her response lasted for 12 months, considerably above the 6-month median survival and 27.6% 1-yr survival in the SEER database for 241 patients with adjacent structures invaded but no distant metastases (27). The role of cetuximab in addition to the IMRT in our patient is uncertain.

Unfortunately, as happens to most patients with ATC, our patient had progression of her locoregional disease and died from local complications. Options for additional treatment regimens, if desired by the patient, would have included a clinical trial (she was accepted for one) or an aggressive cytotoxic combination regimen as reported by Foote et al. (40). There is currently Radiation Therapy Oncology Group trial available for patients with her stage of disease, but this trial was unavailable 3 yr ago.

Summary

At present, most evidence-based literature for management of ATC is low-quality, although support is stronger for surgery followed by IMRT (± chemotherapy) in patients in whom an R0/R1 resection can be performed and who wish aggressive treatment. In patients with stage IVA/IVB disease (including R2 resections), selected patients may also benefit from aggressive combination chemotherapy after IMRT (40). Adjuvant chemotherapy will likely improve outcomes because even most patients with initial responses will eventually succumb to their disease. However, what drug combinations to use, their doses, and timing of therapy are unknown, and prospective clinical trials are urgently needed.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Mayo Clinic, National Institutes of Health Grant R01 CA136665-1, and a generous gift from Alfred D. and Audrey M. Petersen.

Disclosure Summary: The author has nothing to disclose.

Footnotes

- ATC

- Anaplastic thyroid carcinoma

- CT

- computed tomography

- DTC

- differentiated thyroid carcinoma

- EGFR

- epidermal growth factor receptor

- IMRT

- intensity modulated radiation therapy

- PET

- positron emission tomography

- SUV

- standardized uptake value.

References

- 1. Siegel R, Ward E, Brawley O, Jemal A. 2011. Cancer statistics, 2011: the impact of eliminating socioeconomic and racial disparities on premature cancer deaths. CA Cancer J Clin 61:212–236 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Al-Hamdan N, Ravichandran K, Al-Sayyad J, Al-Lawati J, Khazal Z, Al-Khateeb F, Abdulwahab A, Al-Asfour A. 2009. Incidence of cancer in Gulf Cooperation Council countries, 1998–2001. East Mediterr Health J 15:600–611 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Jung KW, Park S, Kong HJ, Won YJ, Boo YK, Shin HR, Park EC, Lee JS. 2010. Cancer statistics in Korea: incidence, mortality and survival in 2006–2007. J Korean Med Sci 25:1113–1121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Smallridge RC, Abate E, Anaplastic thyroid carcinoma: clinical aspects. In: Wartofsky L, Van Nostrand D, eds. Thyroid cancer: a comprehensive guide to clinical management. 3rd ed (in press) New York: Springer [Google Scholar]

- 5. Smallridge RC, Marlow LA, Copland JA. 2009. Anaplastic thyroid cancer: molecular pathogenesis and emerging therapies. Endocr Relat Cancer 16:17–44 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Smallridge RC, Copland JA. 2010. Anaplastic thyroid carcinoma: pathogenesis and emerging therapies. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol) 22:486–497 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Abate EG, Smallridge RC. 2011. Managing anaplastic thyroid carcinoma. Expert Rev Endocrinol Metab 6:793–809 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Smallridge RC, Abate E, Anaplastic thyroid carcinoma: prognosis. In: Wartofsky L, Van Nostrand D, eds. Thyroid cancer: a comprehensive guide to clinical management. 3rd ed (in press) New York: Springer [Google Scholar]

- 9. Elliott DD, Sherman SI, Busaidy NL, Williams MD, Santarpia L, Clayman GL, El-Naggar AK. 2008. Growth factor receptors expression in anaplastic thyroid carcinoma: potential markers for therapeutic stratification. Hum Pathol 39:15–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ensinger C, Spizzo G, Moser P, Tschoerner I, Prommegger R, Gabriel M, Mikuz G, Schmid KW. 2004. Epidermal growth factor receptor as a novel therapeutic target in anaplastic thyroid carcinomas. Ann NY Acad Sci 1030:69–77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Schiff BA, McMurphy AB, Jasser SA, Younes MN, Doan D, Yigitbasi OG, Kim S, Zhou G, Mandal M, Bekele BN, Holsinger FC, Sherman SI, Yeung SC, El-Naggar AK, Myers JN. 2004. Epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) is overexpressed in anaplastic thyroid cancer, and the EGFR inhibitor gefitinib inhibits the growth of anaplastic thyroid cancer. Clin Cancer Res 10:8594–8602 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Wiseman SM, Masoudi H, Niblock P, Turbin D, Rajput A, Hay J, Bugis S, Filipenko D, Huntsman D, Gilks B. 2007. Anaplastic thyroid carcinoma: expression profile of targets for therapy offers new insights for disease treatment. Ann Surg Oncol 14:719–729 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kurebayashi J, Okubo S, Yamamoto Y, Ikeda M, Tanaka K, Otsuki T, Sonoo H. 2006. Additive antitumor effects of gefitinib and imatinib on anaplastic thyroid cancer cells. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 58:460–470 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Nobuhara Y, Onoda N, Yamashita Y, Yamasaki M, Ogisawa K, Takashima T, Ishikawa T, Hirakawa K. 2005. Efficacy of epidermal growth factor receptor-targeted molecular therapy in anaplastic thyroid cancer cell lines. Br J Cancer 92:1110–1116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hoffmann S, Burchert A, Wunderlich A, Wang Y, Lingelbach S, Hofbauer LC, Rothmund M, Zielke A. 2007. Differential effects of cetuximab and AEE 788 on epidermal growth factor receptor (EGF-R) and vascular endothelial growth factor receptor (VEGF-R) in thyroid cancer cell lines. Endocrine 31:105–113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Prahallad A, Sun C, Huang S, Di Nicolantonio F, Salazar R, Zecchin D, Beijersbergen RL, Bardelli A, Bernards R. 2012. Unresponsiveness of colon cancer to BRAF(V600E) inhibition through feedback activation of EGFR. Nature 483:100–103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Nguyen BD, Ram PC. 2007. PET/CT staging and posttherapeutic monitoring of anaplastic thyroid carcinoma. Clin Nucl Med 32:145–149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Bogsrud TV, Karantanis D, Nathan MA, Mullan BP, Wiseman GA, Kasperbauer JL, Reading CC, Hay ID, Lowe VJ. 2008. 18F-FDG PET in the management of patients with anaplastic thyroid carcinoma. Thyroid 18:713–719 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Poisson T, Deandreis D, Leboulleux S, Bidault F, Bonniaud G, Baillot S, Aupérin A, Al Ghuzlan A, Travagli JP, Lumbroso J, Baudin E, Schlumberger M. 2010. 18F-Fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography and computed tomography in anaplastic thyroid cancer. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 37:2277–2285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Akaishi J, Sugino K, Kitagawa W, Nagahama M, Kameyama K, Shimizu K, Ito K, Ito K. 2011. Prognostic factors and treatment outcomes of 100 cases of anaplastic thyroid carcinoma. Thyroid 21:1183–1189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ito K, Hanamura T, Murayama K, Okada T, Watanabe T, Harada M, Ito T, Koyama H, Kanai T, Maeno K, Mochizuki Y, Amano J. 2012. Multimodality therapeutic outcomes in anaplastic thyroid carcinoma: improved survival in subgroups of patients with localized primary tumors. Head Neck 34:230–237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. McIver B, Hay ID, Giuffrida DF, Dvorak CE, Grant CS, Thompson GB, van Heerden JA, Goellner JR. 2001. Anaplastic thyroid carcinoma: a 50-year experience at a single institution. Surgery 130:1028–1034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Passler C, Scheuba C, Prager G, Kaserer K, Flores JA, Vierhapper H, Niederle B. 1999. Anaplastic (undifferentiated) thyroid carcinoma (ATC). A retrospective analysis. Langenbecks Arch Surg 384:284–293 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Swaak-Kragten AT, de Wilt JH, Schmitz PI, Bontenbal M, Levendag PC. 2009. Multimodality treatment for anaplastic thyroid carcinoma—treatment outcome in 75 patients. Radiother Oncol 92:100–104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. De Crevoisier R, Baudin E, Bachelot A, Leboulleux S, Travagli JP, Caillou B, Schlumberger M. 2004. Combined treatment of anaplastic thyroid carcinoma with surgery, chemotherapy, and hyperfractionated accelerated external radiotherapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 60:1137–1143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kebebew E, Greenspan FS, Clark OH, Woeber KA, McMillan A. 2005. Anaplastic thyroid carcinoma. Treatment outcome and prognostic factors. Cancer 103:1330–1335 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Chen J, Tward JD, Shrieve DC, Hitchcock YJ. 2008. Surgery and radiotherapy improves survival in patients with anaplastic thyroid carcinoma: analysis of the surveillance, epidemiology, and end results 1983–2002. Am J Clin Oncol 31:460–464 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Tennvall J, Lundell G, Wahlberg P, Bergenfelz A, Grimelius L, Akerman M, Hjelm Skog AL, Wallin G. 2002. Anaplastic thyroid carcinoma: three protocols combining doxorubicin, hyperfractionated radiotherapy and surgery. Br J Cancer 86:1848–1853 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Dandekar P, Harmer C, Barbachano Y, Rhys-Evans P, Harrington K, Nutting C, Newbold K. 2009. Hyperfractionated accelerated radiotherapy (HART) for anaplastic thyroid carcinoma: toxicity and survival analysis. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 74:518–521 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Wong CS, Van Dyk J, Simpson WJ. 1991. Myelopathy following hyperfractionated accelerated radiotherapy for anaplastic thyroid carcinoma. Radiother Oncol 20:3–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Bhatia A, Rao A, Ang KK, Garden AS, Morrison WH, Rosenthal DI, Evans DB, Clayman G, Sherman SI, Schwartz DL. 2010. Anaplastic thyroid cancer: clinical outcomes with conformal radiotherapy. Head Neck 32:829–836 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Nutting CM, Convery DJ, Cosgrove VP, Rowbottom C, Vini L, Harmer C, Dearnaley DP, Webb S. 2001. Improvements in target coverage and reduced spinal cord irradiation using intensity-modulated radiotherapy (IMRT) in patients with carcinoma of the thyroid gland. Radiother Oncol 60:173–180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Wang Y, Tsang R, Asa S, Dickson B, Arenovich T, Brierley J. 2006. Clinical outcome of anaplastic thyroid carcinoma treated with radiotherapy of once- and twice-daily fractionation regimens. Cancer 107:1786–1792 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Tan RK, Finley RK, 3rd, Driscoll D, Bakamjian V, Hicks WL, Jr, Shedd DP. 1995. Anaplastic carcinoma of the thyroid: a 24-year experience. Head Neck 17:41–47; discussion 47–48 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Pierie JP, Muzikansky A, Gaz RD, Faquin WC, Ott MJ. 2002. The effect of surgery and radiotherapy on outcome of anaplastic thyroid carcinoma. Ann Surg Oncol 9:57–64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Shimaoka K, Schoenfeld DA, DeWys WD, Creech RH, DeConti R. 1985. A randomized trial of doxorubicin versus doxorubicin plus cisplatin in patients with advanced thyroid carcinoma. Cancer 56:2155–2160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Ain KB, Egorin MJ, DeSimone PA. 2000. Treatment of anaplastic thyroid carcinoma with paclitaxel: phase 2 trial using ninety-six-hour infusion. Collaborative anaplastic thyroid cancer health intervention trials (CATCHIT) group. Thyroid 10:587–594 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Higashiyama T, Ito Y, Hirokawa M, Fukushima M, Uruno T, Miya A, Matsuzuka F, Miyauchi A. 2010. Induction chemotherapy with weekly paclitaxel administration for anaplastic thyroid carcinoma. Thyroid 20:7–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Troch M, Koperek O, Scheuba C, Dieckmann K, Hoffmann M, Niederle B, Raderer M. 2010. High efficacy of concomitant treatment of undifferentiated (anaplastic) thyroid cancer with radiation and docetaxel. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 95:E54–E57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Foote RL, Molina JR, Kasperbauer JL, Lloyd RV, McIver B, Morris JC, Grant CS, Thompson GB, Richards ML, Hay ID, Smallridge RC, Bible KC. 2011. Enhanced survival in locoregionally confined anaplastic thyroid carcinoma: a single-institution experience using aggressive multimodal therapy. Thyroid 21:25–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Mooney CJ, Nagaiah G, Fu P, Wasman JK, Cooney MM, Savvides PS, Bokar JA, Dowlati A, Wang D, Agarwala SS, Flick SM, Hartman PH, Ortiz JD, Lavertu PN, Remick SC. 2009. A phase II trial of fosbretabulin in advanced anaplastic thyroid carcinoma and correlation of baseline serum-soluble intracellular adhesion molecule-1 with outcome. Thyroid 19:233–240 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Ha HT, Lee JS, Urba S, Koenig RJ, Sisson J, Giordano T, Worden FP. 2010. A phase II study of imatinib in patients with advanced anaplastic thyroid cancer. Thyroid 20:975–980 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Hogan T, Jing Jie Yu, Williams HJ, Altaha R, Xiaobing Liang, Qi He. 2009. Oncocytic, focally anaplastic, thyroid cancer responding to erlotinib. J Oncol Pharm Pract 15:111–117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Masago K, Miura M, Toyama Y, Togashi Y, Mishima M. 2011. Good clinical response to erlotinib in a patient with anaplastic thyroid carcinoma harboring an epidermal growth factor somatic Mutation, L858R, in exon 21. J Clin Oncol 29:e465–e467 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Fury MG, Solit DB, Su YB, Rosen N, Sirotnak FM, Smith RP, Azzoli CG, Gomez JE, Miller VA, Kris MG, Pizzo BA, Henry R, Pfister DG, Rizvi NA. 2007. A phase I trial of intermittent high-dose gefitinib and fixed-dose docetaxel in patients with advanced solid tumors. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 59:467–475 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Pennell NA, Daniels GH, Haddad RI, Ross DS, Evans T, Wirth LJ, Fidias PH, Temel JS, Gurubhagavatula S, Heist RS, Clark JR, Lynch TJ. 2008. A phase II study of gefitinib in patients with advanced thyroid cancer. Thyroid 18:317–323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Haigh PI, Ituarte PH, Wu HS, Treseler PA, Posner MD, Quivey JM, Duh QY, Clark OH. 2001. Completely resected anaplastic thyroid carcinoma combined with adjuvant chemotherapy and irradiation is associated with prolonged survival. Cancer 91:2335–2342 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Kihara M, Miyauchi A, Yamauchi A, Yokomise H. 2004. Prognostic factors of anaplastic thyroid carcinoma. Surg Today 34:394–398 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.