Abstract

Understanding the post-treatment physical and mental function of older adults from ethnic/racial minority backgrounds with cancer is a critical step to determine the services required to serve this growing population. The double jeopardy hypothesis suggests being a minority and old could have compounding effects on health. This population-based study examined the physical and mental function of older adults by age (mean age = 75.7, SD = 6.1), ethnicity/race, and cancer (breast, prostate, colorectal, and gynecologic) as well as interaction effects between age, ethnicity/race and HRQOL. There was evidence of a significant age by ethnicity/race interaction in physical function for breast, prostate and all sites combined, but the interaction became non-significant (for breast and all sites combined) when comorbidity was entered into the model. The interaction persisted in the prostate cancer group after controlling for comorbidity, such that African Americans and Asian Americans in the 75–79 age group report lower physical health than non-Hispanic Whites and Hispanic Whites in this age group. The presence of double jeopardy in the breast and all sites combined group can be explained by a differential comorbid burden among the older (75–79) minority group, but the interaction found in prostate cancer survivors does not reflect this differential comorbid burden.

1. Introduction

By 2030, nearly one in five US residents will be >65 years of age and this group is projected to reach 72 million by that year, a doubling of the number in 2008 [1]. During this period, it is estimated that the percentage of all cancers diagnosed in older adults and ethnic/racial minorities will increase from 61% to 70% and from 21% to 28%, respectively [2]. Historically, older adults and minorities have been underrepresented in cancer clinical trials which can ultimately lead to disparities in treatment and outcomes. An important outcome that has received little attention is the posttreatment health-related quality of life (HRQOL) of older adults with cancer from minority backgrounds. The double jeopardy hypothesis suggests that being a minority and old could have additive negative effects on health outcomes [3–5]. Understanding the post-treatment burden of older adults and minorities with cancer is a critical step to determine the services and resources required to serve this rapidly growing population.

While the long-term surveillance of older adults and minorities with cancer is limited, evidence suggests physical and social functioning are the most common HRQOL domains affected by cancer and its treatment, with mixed findings for mental health for this group of survivors [6–12]. A population-based study of 703 adult breast cancer survivors found significant ethnic differences in HRQOL, with Latinos reporting greater role limitations and lower emotional well-being than Caucasians, African Americans, and Asian Americans [11]. Another study, focused on disparities in older cancer survivors and non-cancer-managed care enrollees, found physical and mental function were lower in Hispanic cancer survivors compared with Caucasian and African Americans [8]. Deimling and colleagues found older, African American cancer survivors experience poorer functional health and higher levels of comorbidity and decreased physical functioning after cancer compared with older Caucasian cancer survivors [7]. Most recently, a prospective study of 1,432 older cancer survivors and 7,160 matched controls found significant declines in physical function and mental health across several cancer sites relative to the mean change of the control group [13]. Despite the contribution of these few studies to our understanding of HRQOL in older adults from minority backgrounds, they are mostly confined to survivors of prostate or breast cancer or are restricted to short-term (i.e., less than 5 years) survivors. Importantly, studies that have examined the effect of age and race have done so in isolation without attention to possible interaction effects between these important, yet understudied correlates of HRQOL. Other factors found to be related to quality of life in cancer survivors, including optimism, perceived control, and social support were also examined to control for these effects on HRQOL outcomes [9, 11].

To examine the relationship between age and race/ethnicity with HRQOL among cancer survivors, we conducted one of the largest population-based studies of long-term, ethnically diverse, adult cancer survivors in the United States. The overall goal of the study was to obtain information regarding medical follow-up care and late health effects, including HRQOL during the extended survivorship years to facilitate the development of standards or best practices for such care. The specific objectives of these analyses were: (1) to examine the HRQOL of older long-term cancer survivors by cancer type (breast, prostate, colorectal, and gynecologic cancer), ethnicity/race (non-Hispanic White, Hispanic White, African American and Asian American) and age group (65–74, 75–84 and 85 plus) and (2) to examine potential interaction effects between age and ethnicity/race as well as other demographic, health, and psychosocial correlates of HRQOL in older long-term cancer survivors. We hypothesized that there would be a significant interaction effect between minority status and age, with ethnic/racial minority disparities in HRQOL increasing with age.

2. Methods

2.1. Participants and Procedures

Study subjects were men and women who participated in the Follow-Up Care Use of Cancer Survivors (FOCUS) Study, a population-based, cross-sectional study of ethnically diverse adult survivors of breast, prostate, colorectal, ovarian, and endometrial cancers from northern and southern California funded by the National Cancer Institute. Selected patients were mailed a detailed questionnaire to complete on their own and return in a postage paid envelope. Extensive telephone followup was conducted and additional questionnaire mailings were sent in efforts to reach patients and increase response rates. The study was approved by the institutional review boards at the Cancer Prevention Institute of California (CPIC, formerly known as the Northern California Cancer Center (NCCC)) and the University of Southern California (USC), Los Angeles, in accord with an assurance filed and approved by the US Department of Health and Human Services.

The cancer patients were selected from the CPIC and the Los Angeles County Cancer Surveillance Program, cancer registries that are members of the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) program. To be eligible, patients had to be English speaking, adults at least 21 years of age at diagnosis, have a primary diagnosis of breast, prostate, colorectal, ovarian, or endometrial cancer and have completed treatment. Case selection was stratified by cancer site, time since diagnosis, age group, and race/ethnicity to provide sufficient sample size in each subgroup for analyses. Specifically, time since diagnosis was dichotomized between an average of 6 (4 to 8) and 12 (10–15) years after initial cancer diagnosis. Age group included those <65 and 65+, while race/ethnicity was stratified by ethnicity/race: non-Hispanic White, African American, Hispanic White, and Asian American.

Of the 6,391 selected cases (not known to be deceased at the time of sample selection), 4,981 (78%) were eligible after we eliminated those who were found to be deceased after attempts to contact (n = 415), unable to understand English (n = 477), too ill to participate (n = 289), said they never had cancer (n = 142), whose physician did not provide consent (n = 42), or were otherwise ineligible (n = 45; e.g., in active treatment, out of the country). Of the 4,981 eligible, an additional 2,004 (40%) could not be located after multiple efforts were made to trace and locate them, (using web-based tracing services such as “reach411”, “Intelius,” “Masterfiles,” and “Acxiom”,) yielding a total of 2,977 eligible cases who were reached. Of these, 1,666 (56%) completed the mailed survey for the FOCUS study. Upon review of the surveys, a further 84 cases where the respondent indicated he/she was not in treatment were removed from all analyses leaving a final sample of 1,582 cases.

Multivariable logistic regression was used to determine factors related to participant response. Among the 4,981 eligible selected cases, those 65 and older, those with colorectal cancer, and those diagnosed longer ago were less likely to participate. Lastly, as this paper focused on outcomes for older adults (≥65 years of age), those in the sample younger than 65 (N = 511; 32%) were excluded resulting in an analytic sample that included 1,071 study respondents.

Eligible study participants were mailed a self-report study questionnaire containing a number of standardized measures to assess psychosocial and HRQOL variables along with questions assessing late health effects and follow-up care patterns specific to the larger FOCUS project. Included in the mailing was an introductory letter describing the purpose of the study and a prepaid return envelope. If the survey had not been returned after three weeks, the survivors were called to make sure they had received the questionnaire, answer any questions, and encourage them to send in the questionnaire. Upon return of the completed questionnaire, study participants received either a $20 (LA County Cancer Surveillance Program) or $25 (CPIC) check and a thank you letter.

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Demographic and Disease Characteristics

Self-reported socio-demographic information included age, sex, ethnicity/race, marital status, education, and health insurance. While household income was collected, the percent (11%) of missing data from this variable was significantly higher than the percent missing for education (1.4%); thus the decision was made to use education as a proxy for SES as opposed to both education and income. Additionally, income and education were highly correlated in this sample. Health-related characteristics, including type of treatment, cancer history, and disease stage were collected via SEER registry data. Based on SEER historic staging information, stage of disease was characterized as local, regional, and distant for breast, colorectal and gynecologic, whereas prostate cancer stage was differentiated as local and regional or distant. Times since diagnosis and comorbid medical conditions (checklist of 39 medical conditions, including irregular heartbeat, heart failure, cardiomyopathy, heart attack, angina, hypertension, pericarditis, leaking heart valves, blood clots, stroke, epilepsy, seizures, neuropathy, chronic lung disease, asthma, pleurisy, lung fibrosis, pneumonia, abnormal liver function, liver disease, inflammatory bowel disease, gallbladder problems, kidney stones, kidney or bladder infections, hyperthyroid, hypothyroid, diabetes, osteoporosis, avascular necrosis, partial or complete deafness, cataracts, problems with retina, arthritis, lymphedema, anemia, shingles, sciatica, and fertility issues) were collected via self-report. The comorbidity checklist was adapted from previous studies on cancer [14, 15].

2.2.2. Health-Related Quality of Life

Two summary scores from the Short Form–12 were used to measure HRQOL [16, 17]. These included the physical component summary (PCS) score and mental component summary (MCS) score constructed on the basis of the 1999 US population norms with a mean value of 50 that represented the US population norms and a standard deviation of 10.

2.2.3. Psychosocial Factors

The Life Orientation Test-Revised (LOT-R) was used to measure optimism [18]. The LOT-R is a 6-item scale including items such as “In uncertain times, I usually expect the best.” The scale has exhibited good reliability and validity in use with chronically ill populations, including cancer patients [9, 19]. Cronbach's alpha for the six items in the current study was .93. The 12-item short form of the MOS Social Support scale was used to assess social support [20, 21]. For each item, the respondent was asked to indicate how often social support was available to him or her if needed. Response options ranged from “none of the time” to “all of the time.” Items were summed and transformed into a scale of 0 to 100. Cronbach's alpha for the Social Support scale in the current study was .95. Perceived control was measured using a 4-item scale used in an earlier study. [14] Respondents were asked to indicate the extent of control they have over aspects of cancer, including “emotional responses to your cancer”, “physical side effects of your cancer and its treatment”, “the course of your cancer (i.e., whether cancer will come back or get worse)”, and “the kind of follow-up care you receive for your cancer.” Response options ranged from “no control at all” to “complete control”. The four items were summed and transformed into a scale of 0 to 100. Cronbach's alpha for these four items was .88.

2.3. Analytic Plan

Descriptive statistics were used to describe the demographic, health, and psychosocial characteristics of the sample. Separate general linear models (GLMS) were run for all cancer sites combined as well as for each specific cancer site to test the main effects of independent variables (age, ethnicity/race, education, medical comorbidities, optimism, and social support) and the interaction effects of age and ethnicity/race on physical and mental health. Variables included in these multivariable models were significantly associated (P < .05) with HRQOL at the bivariate level using χ2 tests for categorical variables and t tests for continuous variables. The following variables not associated with HRQOL in bivariate analyses were not included in the final model: gender, cancer stage, health insurance coverage, time since diagnosis, SEER site and type of cancer treatment received, and perceived control. Blocks of variables were entered into the models sequentially to examine the impact of each category of factors (demographic, health, and psychosocial) on HRQOL. Adjusted means and standard errors of outcome measures by categorical demographic and health characteristics were calculated using general linear modeling (GLM) and beta coefficients and standard errors of outcomes were generated for continuous variables. Tukey's post hoc tests were used to detect significant differences. Estimated marginal means were used to plot the effects of age and race on HRQOL. Analyses were conducted using SPSS version 16.

3. Results

3.1. Sample Characteristics

The analytic sample consisted of 1,071 men and women aged 65 years or older (Mean = 75.7, SD = 6.1) diagnosed with confirmed cases of breast, prostate, colorectal, or gynecologic cancer. The gynecologic cancer group included both endometrial and ovarian cancers due to insufficient sample sizes to permit separate analyses for each group. Table 1 displays other characteristics of the sample. Average time since diagnosis was 9 years (SD = 3.2). Two-thirds of the sample was represented by ethnic/racial minority groups providing sufficient sample size for testing age/race interaction effects on HRQOL. The sample consisted of slightly more (P < .05) females (61%) than males. Table 2 shows the mean scores and standard deviation for the psychosocial and HRQOL scales. Physical and mental HRQOL scores across all cancer sites were marginally lower than general US population norms for individuals aged 65 years or older [16].

Table 1.

Sample characteristics (%).

| Total | Breast | Prostate | Colorectal | Gyn. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = 1071 | N = 247 | N = 314 | N = 274 | N = 236 | |

| Current age | |||||

| 65–74 | 43.4 | 36.4 | 40.5 | 43.4 | 41.5 |

| 75–84 | 26.0 | 27.5 | 25.5 | 22.6 | 29.2 |

| 85+ | 30.6 | 36.0 | 23.9 | 33.9 | 29.2 |

| Race/ethnicity | |||||

| Non-Hispanic, White | 33.6 | 31.5 | 25.7 | 33.1 | 42.3 |

| Hispanic, White | 19.6 | 19.8 | 24.4 | 17.3 | 16.9 |

| African American | 24.3 | 24.6 | 26.0 | 26.5 | 21.1 |

| Asian American | 22.4 | 24.1 | 23.9 | 23.2 | 19.7 |

| Gender | |||||

| Male | 38.4 | — | 100 | 50.6 | — |

| Female | 61.6 | 100 | — | 49.4 | 100 |

| Education | |||||

| <High school | 9.9 | 7.3 | 12.4 | 10.9 | 8.8 |

| High school/GED | 17.0 | 18.9 | 14.9 | 16.3 | 18.0 |

| Some college/technical school | 36.2 | 33.5 | 30.2 | 41.5 | 40.1 |

| College graduate (or more) | 36.9 | 39.6 | 42.5 | 31.3 | 33.1 |

| Health insurance | |||||

| Yes | 97.1 | 97.2 | 97.8 | 97.0 | 96.4 |

| No | 2.9 | 2.8 | 2.2 | 3.0 | 3.6 |

| Stage (SEER) | |||||

| Localized | 45.6 | 74.4 | — | 48.3 | 62.9 |

| Regional | 21.3 | 23.9 | — | 49.1 | 14.2 |

| Distant | 6.8 | 1.5 | 1.3 | 1.5 | 20.6∗ |

| Localized/regional (prostate only) | — | — | 95.7 | — | — |

| Unstaged | 1.8 | 0.3 | 3.1 | 1.0 | 2.2 |

| Comorbid medical conditions | |||||

| Mean (std) | 5.4 ± 3.7 | 5.7 ± 4.0 | 4.8 ± 3.3 | 5.3 ± 3.6 | 5.6 ± 3.5 |

| Current symptoms | |||||

| Mean (std) | 6.3 ± 4.7 | 6.7 ± 4.4 | 5.2 ± 4.4 | 5.8 ± 4.7 | 7.2 ± 4.9 |

∗The high rate of distant disease in the gynecologic group reflects higher rates of distant disease in African American women with endometrial cancer, which is comparable to rates in the US population.

Table 2.

Unadjusted mean scores and standard deviations for psychosocial/HRQOL scales.

| Total | Breast | Prostate | Colorectal | Gynecologic | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Optimism∗ | 16.2 (3.8) | 16.2 (3.7) | 16.3 (3.7) | 15.9 (3.8) | 16.2 (3.8) |

| Social support† | 80.4 (17.7) | 79.1 (17.8) | 82.6 (17.7) | 80.5 (17.9) | 78.8 (17.7) |

| Physical function‡ | 42.5 (11.4) | 41.2 (11.4) | 44.5 (11.2) | 42.4 (11.6) | 41.1 (11.4) |

| Mental function‡ | 52.1 (9.0) | 51.4 (9.3) | 52.8 (8.9) | 51.9 (9.0) | 52.1 (8.9) |

∗Scored on a 0–24 scale (higher scores reflect higher optimism).

†Scored on a 0–100 scale (higher scores reflect more social support).

‡Constructed on the basis of the 1999 US population norms with a mean value of 50 that represented the US population norms and a standard deviation of 10. Higher scores reflect better function.

3.2. Correlates of HRQOL in Ethnically Diverse Older Adults with Cancer

Using the GLM procedure, adjusted mean scores were calculated to examine the association between demographic, health related, and psychosocial factors with physical and mental health (Table 3). The following section describes the results of the GLM procedure overall (all sites combined) and across the different cancer sites.

Table 3.

Adjusted mean HRQOL scores† by demographic, health, and psychosocial characteristics.

| Overall | Breast | Prostate | Colorectal | Gynecologic | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MCS | PCS | MCS | PCS | MCS | PCS | MCS | PCS | MCS | PCS | |

| Demographic | ||||||||||

| Age | ||||||||||

| 65−74 | 50.9 (0.5) b | 43.6 (0.5) b | 49.3 (1.1) b | 41.8 (1.2) b | 51.5 (0.8) | 46.8 (0.9) b | 51.6 (0.9) | 42.7 (1.1) b | 50.1 (1.0) | 42.1 (1.1) b |

| 75−84 | 52.4 (0.5) a | 41.9 (0.7) a | 51.3 (1.2) a | 40.4 (1.3) b, c | 52.2 (1.1) | 42.5 (1.2) a | 53.9 (1.1) | 41.4 (1.6) a | 52.1 (1.1) | 41.3 (1.3) b |

| 85+ | 52.2 (0.5) a | 39.6 (0.7) a | 52.4 (1.1) a | 36.6 (1.2) a | 52.1 (1.1) | 41.5 (1.3) a | 52.1 (1.1) | 39.2 (1.3) a | 51.6 (1.4) | 37.9 (1.5) a |

| Race/ethnicity‡ | ||||||||||

| NHW | 52.6 (0.5) | 42.6 (0.6) b | 53.6 (1.1) b | 40.4 (1.3) b | 53.7 (1.1) b | 40.4 (1.3) b | 51.3 (1.1) a | 42.9 (1.2) b | 52.8 (0.9) | 42.2 (1.1) |

| HW | 51.7 (0.7) | 43.4 (0.8) b | 48.0 (1.4) a | 41.9 (1.6) b | 48.0 (1.4) a | 41.9 (1.6) b | 55.1 (1.5) b | 40.6 (1.8) a | 51.7 (1.5) | 42.1 (1.7) |

| AA | 51.6 (0.6) | 40.2 (0.7) a | 52.7 (1.3) b | 38.1 (1.5) a | 52.7 (1.3) b | 38.1 (1.5) a | 51.7 (1.4) a | 39.9 (1.6) a | 48.3 (1.4) | 38.5 (1.6) |

| Asian American | 51.4 (0.7) | 40.6 (0.8) a | 49.9 (1.4) a | 37.9 (1.5) a | 49.9 (1.4) a | 37.9 (1.5) a | 52.1 (1.4) a | 41.1 (1.6) a | 52.2 (1.5) | 38.8 (1.7) |

| Education | ||||||||||

| <HS | 49.8 (0.8) b | 40.4 (0.9) a | 49.8 (1.9) | 32.1 (2.1) a | 49.8 (1.9) | 32.1 (2.1) b | 49.4 (1.6) | 40.8 (1.9) b | 50.2 (1.8) | 40.7 (2.1) a |

| HS/GED | 51.8 (0.7) a | 40.2 (0.7) a | 51.6 (1.3) | 42.3 (1.5) b | 51.6 (1.3) | 42.3 (1.5) a | 54.2 (1.4) | 36.8 (1.7) a | 51.3 (1.3) | 37.7 (1.4) b, c |

| Some C/T | 52.8 (0.5) a | 41.8 (0.6) b | 52.3 (1.0) | 41.9 (1.2) b | 52.3 (1.0) | 41.9 (1.2) a | 52.6 (0.9) | 43.0 (1.2) b, c | 52.1 (1.1) | 40.6 (1.2) a |

| College grad | 52.8 (0.5) a | 44.4 (0.6) a | 50.6 (1.2) | 41.9 (1.3) b | 50.6 (1.2) | 41.9 (1.3) a | 53.9 (1.2) | 43.9 (1.4) b, c | 51.7 (1.2) | 42.6 (1.3) b |

|

| ||||||||||

| Health | ||||||||||

| Beta coef (SE) | ||||||||||

| Comorbidity | −0.5 (0.1) | −1.4 (0.1) | −0.5 (0.2) | −1.2 (0.2) | −0.5 (0.2) | −1.2 (0.2) | −0.4 (0.2) | −1.5 (0.2) | −0.4 (0.2) | −1.8 (0.2) |

|

| ||||||||||

| Psychosocial | ||||||||||

| Beta Coef. (SE) | ||||||||||

| Social support | 0.1 (0.1) | 0.1 (0.1) | 0.2 (0.1) | 0.1 (0.1) | 0.2 (0.1) | 0.1 (0.1) | 0.2 (0.1) | 0.1 (0.1) | 0.2 (0.1) | 0.1 (0.3) |

| Optimism | 0.8 (0.1) | 0.6 (0.1) | 0.9 (0.1) | 0.2 (0.2) | 0.7 (0.2) | 0.5 (0.2) | 0.9 (0.1) | 0.8 (0.2) | 0.7 (0.2) | 0.7 (0.2) |

|

| ||||||||||

| Model Adj R2 | 22.1 | 29.0 | 24.9 | 36.2 | 15.9 | 36.1 | 20.9 | 33.2 | 20.9 | 37.0 |

†Adjusted for all other variables in the model.

‡NHW: non-Hispanic White; HW: Hispanic White; AA: African American.

Note: values in bold indicate P value <.05 from overall F-test.

Different letters denote statistically significant differences using Tukey's post hoc tests.

3.3. Physical HRQOL

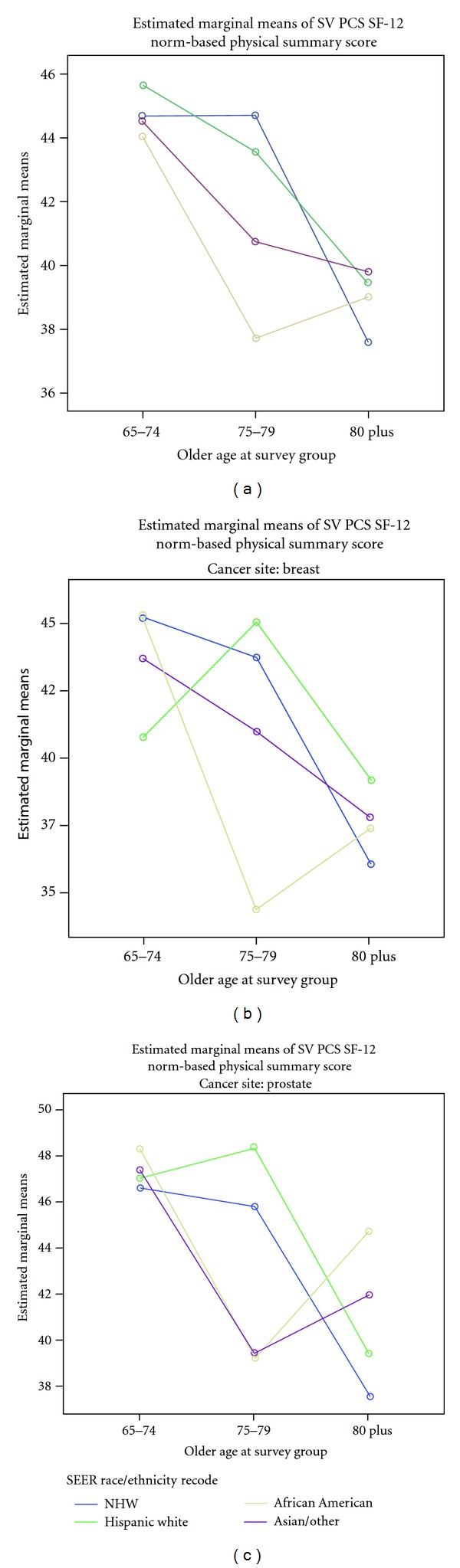

The combined variables in the overall model accounted for 29% (adjusted R2) of the variance in physical HRQOL with demographics accounting for 6%, comorbidity accounting for 19%, and psychosocial factors accounting for 5%. In the overall model, as well as the breast and prostate cancer group, the interaction effect between age and race was significant when entered into the models with the demographic factors, but the effect became nonsignificant in the overall model and breast cancer model once comorbidity was entered into the models. In the overall model, the pattern of interaction was such that African Americans in the 75–79 age group reported lower physical health than non-Hispanic Whites and Hispanic Whites in this age group (see Figure 1). This same pattern existed in the breast cancer group, but these data also showed that Hispanic Whites in the 75–79 age group reported higher physical health scores compared to African American and Asian Americans in this age group. The comorbid burden among all cancer sites combined, as well as the breast cancer group, is significantly (P < .05) greater than the comorbid burden in the prostate cancer group (Table 1). To explore this pattern further, analysis of variance was conducted to see if there was a differential comorbid pattern in African Americans in the 75–79 age group compared to other ethnic/racial groups in this age range. Results indicated that African American breast cancer survivors in this age group reported, on average, 9.6 comorbid conditions (SD = 5.5) compared with 5.3 for non-Hispanic Whites (SD = 3.7), 6.3 for Hispanic Whites (SD = 2.4), and 5.8 for Asian Americans (SD = 3.4) (all P's < .05). This pattern was similar in the overall model.

Figure 1.

Age by race/ethnicity interaction plots (PCS).

With respect to prostate cancer, the significant interaction persisted after entering comorbidity and other psychosocial variables into the model (β = 9.16, SE = 4.5, P < .01). African Americans and Asian Americans in the 75-79 age group reported lower PCS scores than non-Hispanic Whites and Hispanic Whites. These scores were greater in the oldest age group, (80 plus) for African Americans and Asian Americans with a significant difference between African Americans' scores and non-Hispanic Whites' scores on physical HRQOL (Figure 1).

Other findings of interest (see Table 3) include older age significantly associated with lower PCS scores, overall (P < .01) and in the breast and colorectal groups (all Ps < .05). PCS scores for African Americans and Asian Americans in the breast, prostate and “all sites combined” models were significantly lower than non-Hispanic Whites and Hispanic Whites (P < .01). Across all cancer sites, education was significantly associated (Cohen's d effect size = .3) with PCS in that those with a college degree and/or graduate degree had higher PCS scores than all those groups with lower educational attainment (all Ps < .05). A more pronounced relationship between low education and PCS was found in the breast and prostate groups where those survivors without a high school diploma or GED reported PCS scores nine points lower than the survivors with the same education in the colorectal and gynecologic groups. More comorbid conditions were significantly associated with worse PCS (P < .01), overall and across the four cancer sites. Social support was not related to PCS, but higher optimism was significantly associated with better PCS (P < .01) overall and across three of the four sites (i.e., breast cancer, nonsignificant).

3.4. Mental HRQOL

Investigation of MCS scores showed that the variance explained by the set of independent variables in the overall model was 22% (adjusted R2). Unlike PCS scores, the psychosocial variables explained the majority of the variance in mental HRQOL with optimism = 11% and social support = 4%. The remaining variance was explained by demographics (4%) and health factors (3%). In contrast to PCS results, the age-race/ethnicity interaction effect was not significant in the overall model or site-specific models regardless of when it was entered into the model. Overall and in the breast cancer group older age was associated with higher MCS score (all Ps < .05). Additionally, having a college degree or having some college experience was significantly associated with higher scores on MCS compared with graduating from high school or obtaining a GED (Ps < .01) in the colorectal group and in all sites combined. Those with more comorbid conditions reported worse MCS (P < .01), overall and across the four cancer sites. The overall model as well as the site-specific models show higher scores on social support and optimism was significantly associated with higher scores on MCS (Ps < .05).

4. Discussion

This population-based study examined the HRQOL of older long-term cancer survivors by cancer type, ethnicity/race and age as well as potential interaction effects between age, ethnicity/race, and HRQOL. We found that the double jeopardy effect of being an ethnicity/racial minority and older persisted for the overall sample (all sites combined) and the breast cancer group when entered into the model with demographic variables, but the effect went away after controlling for comorbidity. Double jeopardy persisted in the prostate cancer group even after controlling for comorbidity. Different predictors accounted for differing amounts of variance in PCS and MCS scores. In general psychosocial factors were more strongly associated with MCS, while medical comorbidities were more strongly associated with PCS.

The presence of double jeopardy in the overall model (likely driven by the breast cancer group) as well as the breast cancer model could potentially be explained by the higher comorbid burden among African American cancer patients in the middle age group compared to this group in the other cancer sites. The importance of monitoring for comorbidities, especially in older minority breast cancer survivor populations, and ensuring adequate control of these conditions should be of particular concern and is becoming a growing focus of attention in the oncology community [22, 23].

There was evidence to support the existence of double jeopardy in our sample of prostate cancer survivors even after controlling for comorbid conditions. Future research should further explore this interaction as prostate cancer is the most prevalent cancer in older men and African American men are at greater risk compared to white men. Additionally, African American men generally have more advanced disease when diagnosed [24]—perhaps due to delay in diagnosis because of poorer screening rates and access to care. However, stage of disease was not significantly related to HRQOL thus likely did not account for the presence of double jeopardy in this group. It is important to note that our prostate cancer group was quite homogeneous with respect to stage (95% local/regional), so there was little variability to adequately test the association of stage of disease on HRQOL in that group. Figure 1 suggests a higher score in physical function in the oldest age group for African American and Asian Americans compared to non-Hispanic Whites perhaps suggesting a resiliency effect. It is conceivable that the oldest age group reflects a more adaptive and healthy cohort or the younger race-specific cohorts were exposed to events or treatments with long-term impacts on physical function. A healthy survivor bias may also explain this effect. Although there is a 6.2-year reduction in life expectancy at birth for African American males compared to White males, this narrows to 2.2 years at age 65 and only .7 years at age 75 (CDC, Health, United States, 2008). This suggests, that for those African American men who survive to age 75, black-white differences in health may not be as pronounced.

A few additional findings warrant special note. Consistent with other studies [8, 12], these data suggest that race/ethnicity influences physical functioning above and beyond socioeconomic status. African American and Asian American cancer survivors (all sites combined) reported significantly lower PCS scores compared with White and Hispanics, even after controlling for education. This effect also persisted after controlling for noncancer medical comorbidities. These data suggest that clinicians should potentially anticipate differences in older adults from some minority backgrounds, as they may be at risk for greater decrements in physical function as a result of their cancer and treatment. Level of education was found to positively influence not only survivors' reports of physical health (PCS) but also mental health (MCS). A buffering effect of education on illness outcomes has been shown by others [7, 8, 12] and may be a function of the association between more education and increased coping skills, better access to optimal healthcare, including preventive services (contributing to a stronger feeling of control over health care) and greater investment in positive health behaviors. To the extent that racial disparities continue to persist in access to education, this has implications for the future health of these populations.

Not surprisingly, the presence of competing comorbid conditions was found to adversely affect both mental and physical health outcomes. On average, the survivors in this study reported more than five non-cancer comorbidities. In some cases, with cancer survivors now living longer, co-morbid condition may include the diagnosis of a second or third malignancy [25]. Careful assessment of comorbid conditions prior to cancer treatment and across the cancer survivorship trajectory is warranted in all populations of survivors.

Strengths of this study are its population-based stratified sampling method, inclusion of large numbers of older survivors, attention to long-term (5–14 years after diagnosis) survivors' function, and well-being, examination of the four cancer sites for which we have the most prevalent populations of survivors, as well as recruitment of sufficient numbers of minority groups to enable examination of race/ethnicity by age interaction effects on survivors' HRQOL outcomes. However, there are a number of limitations to these data. As noted earlier, those who were sicker, whether due to cancer or other comorbid conditions, non-English speaking, longer-term survivors, and those who were hard to reach (potentially because they had moved to locations where care is delivered by extended family or in assisted living or nursing home facility), did not participate in this survey. Thus, it is not clear how generalizable the present findings are to the broader population of older cancer survivors. This differential pattern of response (or dropout) could account for the unexpected observation that older (80 plus) prostate cancer survivors of Asian and African American background reported better physical HRQOL than their younger (75–79) counterparts. Although this is a cross-sectional study, it was nonetheless interesting to note that, while PCS scores for prostate cancer survivors were similar across ethnic/racial groups in the 65–74 age category, there was considerable divergence on this variable among those in the oldest age category. A further limitation to this study is that, while likely to be a rare occurrence, there is no way of knowing whether a caregiver or family member may have completed the surveys on the survivor's behalf.

Understanding the impact of cancer on HRQOL of older adults from minority backgrounds is of great importance. With the aging of Americans and demographic changes in the ethnic/racial composition of the US population, clinicians need to better anticipate, predict, and treat the physical and mental consequences of cancer and its treatment in specific segments of the population. The current study provides information regarding the physical and mental functioning of older adults from minority backgrounds as well as correlates that can be used to target clinical assessments and interventions. Our study suggests double jeopardy exists in the overall sample and breast cancer survivors, but is explained by differential burden of comorbid conditions in the middle age group for African Americans. Examining the reasons why double jeopardy persists in men with prostate cancer, after controlling for comorbidity warrants further attention. To what extent the compounding effect of age and race on physical function in the middle age group are the result of poorer access to care or delays in screening, and diagnosis in this group is not known, but worthy of future study.

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and The Merck Company Foundation. The State of Aging and Health. Whitehouse Station, NJ, USA: America in Foundation TMC; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Smith BD, Smith GL, Hurria A, Hortobagyi GN, Buchholz TA. Future of cancer incidence in the United States: burdens upon an aging, changing nation. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2009;27(17):2758–2765. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.8983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Clark DO, Maddox GL. Racial and social correlates of age-related changes in functioning. Journals of Gerontology. 1992;47(5):S222–S232. doi: 10.1093/geronj/47.5.s222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ferraro KF, Farmer MM. Double jeopardy to health hypothesis for African Americans: analysis and critique. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1996;37(1):27–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dannefer D. Cumulative advantage/disadvantage and the life course: cross-fertilizing age and social science theory. Journals of Gerontology. 2003;58(6):S327–S337. doi: 10.1093/geronb/58.6.s327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Keating NL, Nørredam M, Landrum MB, Huskamp HA, Meara E. Physical and mental health status of older long-term cancer survivors. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2005;53(12):2145–2152. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.00507.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Deimling GT, Schaefer ML, Kahana B, Bowman KF, Reardon J. Racial differences in the health of older-adult long-term cancer survivors. Journal of Psychosocial Oncology. 2002;20(4):71–94. doi: 10.1300/J077v20n04_05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Clauser SB, Arora NK, Bellizzi KM, Haffer SC, Topor M, Hays RD. Disparities in HRQOL of cancer survivors and non-cancer managed care enrollees. Health Care Financing Review. 2008;29(4):23–40. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Blank TO, Bellizzi KM. After prostate cancer: predictors of well-being among long-term prostate cancer survivors. Cancer. 2006;106(10):2128–2135. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bellizzi KM, Rowland JH. Role of comorbidity, symptoms and age in the health of older survivors following treatment for cancer. Aging Health. 2007;3(5):625–635. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ashing-Giwa KT, Tejero JS, Kim J, Padilla GV, Hellemann G. Examining predictive models of HRQOL in a population-based, multiethnic sample of women with breast carcinoma. Quality of Life Research. 2007;16(3):413–428. doi: 10.1007/s11136-006-9138-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bowen DJ, Alfano CM, McGregor BA, et al. Possible socioeconomic and ethnic disparities in quality of life in a cohort of breast cancer survivors. Breast Cancer Research and Treatment. 2007;106(1):85–95. doi: 10.1007/s10549-006-9479-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Reeve BB, Potosky AL, Smith AW, et al. Impact of cancer on health-related quality of life of older americans. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2009;101(12):860–868. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djp123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Arora NK, Hamilton AS, Potosky AL, et al. Population-based survivorship research using cancer registries: a study of non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma survivors. Journal of Cancer Survivorship. 2007;1(1):49–63. doi: 10.1007/s11764-007-0004-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Potosky AL, Harlan LC, Stanford JL, et al. Prostate cancer practice patterns and quality of life: the Prostate Cancer Outcomes Study. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 1999;91(20):1719–1724. doi: 10.1093/jnci/91.20.1719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ware JE, Kosinski M, Turner-Bowker DM, et al. How to Score Version 2 of he SF-12 Health Survey (With a Supplement Documenting Version 1) Lincoln, RI, USA: Incorporated Q; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ware JE, Kosinski M, Keller SD. A 12-Item Short-Form Health Survey: construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Medical Care. 1996;34(3):220–233. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199603000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Scheier MF, Carver CS, Bridges MW. Distinguishing optimism from neuroticism (and trait anxiety, self-mastery, and self esteem): a reevaluation of the life orientation test. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1994;67(6):1063–1078. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.67.6.1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schou I, Ekeberg O, Ruland CM, Sandvik L, Kåresen R. Pessimism as a predictor of emotional morbidity one year following breast cancer surgery. Psycho-Oncology. 2004;13(5):309–320. doi: 10.1002/pon.747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ganz PA, Desmond KA, Leedham B, Rowland JH, Meyerowitz BE, Belin TR. Quality of life in long-term, disease-free survivors of breast cancer: a follow-up study. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2002;94(1):39–49. doi: 10.1093/jnci/94.1.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sherbourne CD, Stewart AL. The MOS social support survey. Social Science and Medicine. 1991;32(6):705–714. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(91)90150-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rowland JH, Bellizzi KM. Cancer survivors and survivorship research: a reflection on today's successes and tomorrow's challenges. Hematology/Oncology Clinics of North America. 2008;22(2):181–200. doi: 10.1016/j.hoc.2008.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ganz PA. A teachable moment for oncologists: cancer survivors, 10 million strong and growing! Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2005;23(24):5458–5460. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.04.916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Paquette EL, Connelly RR, Sesterhenn IA, et al. Improvements in pathologic staging for African-American men undergoing radical retropubic prostatectomy during the prostate specific antigen era: implications for screening a high-risk group for prostate carcinoma. Cancer. 2001;92(10):2673–2679. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20011115)92:10<2673::aid-cncr1621>3.0.co;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mariotto AB, Rowland JH, Ries LAG, Scoppa S, Feuer EJ. Multiple cancer prevalence: a growing challenge in long-term survivorship. Cancer Epidemiology Biomarkers and Prevention. 2007;16(3):566–571. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-06-0782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]