Abstract

Aim:

The current in vitro study evaluated Vickers hardness (VK) and depth of cure (hardness ratio) of six resin composites, polymerized with a light-emitting diode (LED) curing unit by different polymerization modes: Standard 20 s, Standard 40 s, Soft-start 40 s.

Materials and Methods:

Six resin composites were selected for the present study: three microhybrid (Esthet.X HD, Amaris, Filtek Silorane), two nanohybrid (Grandio, Ceram.X mono) and one nanofilled (Filtek Supreme XT). The VK of the surface was determined with a microhardness tester using a Vickers diamond indenter and a 200 g load applied for 15 seconds. The mean VK and hardness ratio of the specimens were calculated using the formula: hardness ratio = VK of bottom surface / VK of top surface.

Results:

For all the materials tested and with all the polymerization modes, hardness ratio was higher than the minimum value indicated in literature in order to consider the bottom surface as adequately cured (0.80). Curing time did not affect hardness ratio values for Filtek Silorane, Grandio and Filtek Supreme XT.

Conclusion:

The effectiveness of cure at the top and bottom surface was not affected by Soft-start polymerization mode.

Keywords: Resin composites, standard polymerization, soft-start polymerization, Vickers hardnes

INTRODUCTION

Resin-based composites are used worldwide in dentistry, mainly because of their aesthetic quality and good physical properties. Since resin composites were first developed, many efforts have been made to improve the clinical behaviour of this restorative material.[1] Several studies have demonstrated that the degree of polymerization of light-cured resin composites depends on many parameters, such as, the specific formulation (i.e. type and relative amount of monomer, filler and initiator/catalyst), the wavelength distribution, the intensity of the incident light and the irradiation time.[2,3] Although both organic and inorganic phases might influence the material behaviour, the filler particles features’ and rate of curing are the most important factors related to an improvement in the mechanical properties of the resin composites.[4] The intended areas of usage of resin composites have traditionally included a trade-off between composites polish ability and strength, based on filler size and loading. Recently, resin composites have been classified according to their filler particle size as hybrid (0,5-3 μm), microhybrid (0,4-1 μm) and microfilled (0,04-0,4 μm). More recently, however, with the introduction of nanotechnology in dentistry, a new class of resin composite, the nanofilled composite resin, is available to clinicians, in an endeavour to provide a material presenting high initial polishing ability combined with superior polish and gloss retention.

The degree of cure of visible light activated dental resins was recognized as important to the clinical success of these materials soon after these materials were introduced.[5,6] A curing light intensity output depends on many factors (light guide, condition of the bulb, battery life) and the total energy determines the mechanical properties of the resin composites. Also, the distance of the light from the the resin composite is a crucial factor.[7] In the last few years, curing light technology has advanced with the introduction of high intensity halogen lights, plasma arc lights and light emitting diode units (LEDs), with the aim of fast curing of resin composites and generating less heat. LED curing lights have recently become very popular since they have a number of advantages over conventional halogen units. Different light polymerization modes can affect the control on resin composite polymerization reaction. Traditional modes use high initial irradiance and provide a higher degree of conversion (DC); on the other hand, a higher shrinkage stress may be induced during polymerization reaction. Gradual polymerization modes have been introduced in order to minimize polymerization shrinkage and consequent marginal gap formation.[8]

Physical properties of composite resin are also dependent on the DC of the resin matrix. A positive correlation has been demonstrated between increasing hardness and increasing DC; however, it was concluded that an absolute hardness number could not be used to predict DC when different resin composites are compared. A previously published study showed a significant correlation between the degree of conversion and hardness, modulus of elasticity and flexural strength of dental restorative resins.[9] The effectiveness of the composite cure may be assessed directly or indirectly.[10] Direct methods that assess the degree of conversion, such as infrared spectroscopy and laser Raman spectroscopy, have not been accepted for routine use as they are complex, expensive and time consuming. Indirect methods have included visual, scraping and hardness testing. Incremental surface hardness has been shown to be an indicator of the degree of conversion and a good correlation between Knoops hardness and infrared spectroscopy has also been reported.

Hardness is defined as the resistance of a material to indentation or penetration. It has been used to predict the wear resistance of a material and its ability to abrade or be abraded by opposing tooth structures.[11]

To define depth of cure based on top and bottom hardness measurements, it is common to calculate the ratio of bottom/top hardness, and give an arbitrary minimum value for this ratio. In order to consider the bottom surface as adequately cured, values of 0.80 and 0.85 have often been used.[12] The current in vitro study evaluated Vickers hardness (VK) and depth of cure (hardness ratio) of three microhybrid, two nanohybrid and one nanofilled resin composites, polymerized with a LED curing unit by three different polymerization modes.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

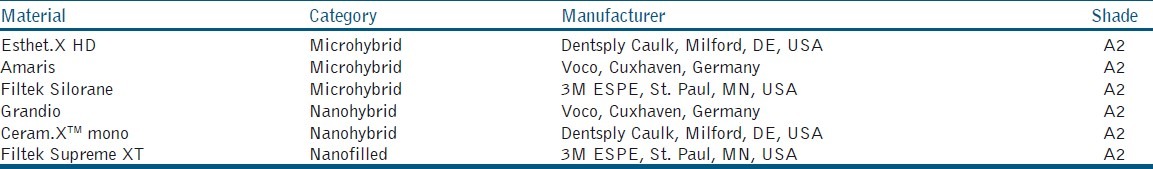

Six resin composites were selected for the present study and were chosen in accordance with their type of filler particles: three microhybrid (Esthet.X HD, Amaris, Filtek Silorane), two nanohybrid (Grandio, Ceram.X mono) and one nanofilled (Filtek Supreme XT). The materials evaluated and their manufacturers are shown in Table 1. During the whole experimentation, the resin composites were light cured with a LED unit, Celalux II (Voco, Cuxhaven, Germany). Three light polymerization modes were used for each material: standard 20 s: 1000 mW/cm2 for 20 seconds; standard 40 s: 1000 mW/cm2 for 40 seconds; soft-start 40 s: 0 to 1000 mW/cm2 for 5 seconds + 1000 mW/cm2 for 35 seconds. The hardness testing methodology used to assess the effectiveness of cure was based upon that used by Yap et al.[13] Samples of the respective materials were prepared by placing the material into a stainless steel mold (Ø 7 mm, h 2 mm), and were placed on a dark opaque paper background covered with a polyester matrix strip. This arrangement minimized the possibility of obtaining artificially higher hardness in that area.[14] The mold was filled with the resin composite and a second polyester matrix strip was placed on the top of the filled mold. A glass slide was pressed against the upper polyester film to extrude the excess resin composite and to form a flat surface. The distal end of the light guide was placed against the surface of the matrix strip and positioned concentrically with the mold; and, the material was then light-cured from the top.

Table 1.

Materials used in the study and their manufacturers

The cordless curing unit was maintained at full charge before use, and irradiance was checked with a radiometer (LED Radiometer, Kerr, Orange, CA, USA). Six samples for each material and for each polymerization mode were prepared. After polymerization, the samples were stored for 48 hours in complete darkness at 37°C and 100% humidity before the Vickers hardness test (VK). The Vickers hardness (VK) of the surface was determined with a microhardness tester (durometer ZHU 0,2 Zwick-Roell, Ulm, Germany) using a Vickers diamond indenter and a 200 g load applied for 15 seconds. Five VK readings were recorded for each sample surface (top and bottom); and the measurements were made in a sequential pattern, starting with the bottom surface of all specimens, and in 1 mm increments from the specimen centre and extending 2 mm in both x (east-west [E-W]) and y (north-south [N-S]) axes. Hardness measurements were not taken at more than 4 mm from the specimen centre to avoid any possible effect of the mold on polymerization.[14] For a given specimen, the five hardness values for each surface were averaged and reported as a single value. The mean Vickers hardness and hardness ratio of the specimens were calculated and tabulated using the formula: hardness ratio = VK of bottom surface / VK of top surface.

RESULTS

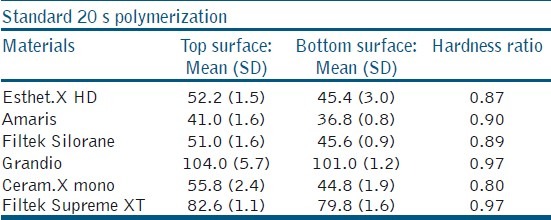

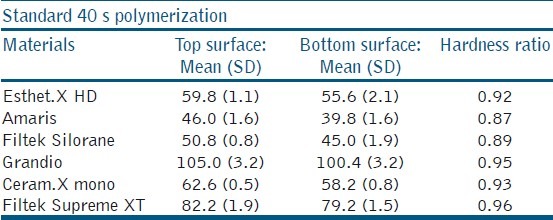

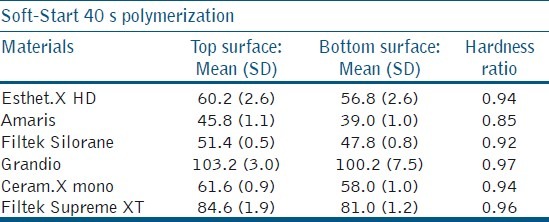

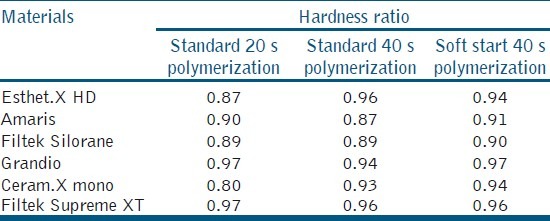

The mean Vickers hardness of top and bottom surfaces and hardness ratio associated with the Standard 20 s polymerization mode is shown in Table 2. The mean Vickers hardness of top and bottom surfaces and hardness ratio associated with the Standard 40 s polymerization mode is shown in Table 3. The mean VK of top and bottom surfaces and hardness ratio associated with the Soft-Start 40 s polymerization mode is shown in Table 4. Hardness ratio values for the three polymerization modes are reported in Table 5. The influence of three curing modes (Standard 20 s and 40 s and Soft-Start 40 s) on hardness ratio of six composite resins was compared. According to statistical analysis (t Student test), it was observed that for all the materials there was no statistical difference (P > 0.5) in hardness values recorded on top surfaces. A statistical significant difference (P < 0.01) was recorded on the bottom surfaces for all the materials tested; and this is due to the reduced energy reaching the lower layers, thus affecting the final hardness.

Table 2.

Mean Vickers hardness of top and bottom surfaces and hardness ratio recorded with the Standard 20 s polymerization mode as seen in the study

Table 3.

Mean Vickers hardness of top and bottom surfaces and hardness ratio recorded with the Standard 40 s polymerization mode as seen in the study

Table 4.

Mean Vickers hardness of top and bottom surfaces and hardness ratio recorded with the Soft-Start 40 s polymerization mode as seen in the study

Table 5.

Hardness ratio values for the different polymerization modes as seen in the study

Despite this drastic difference between the values recorded on the top and bottom surfaces for all the materials, hardness ratio was higher than the minimum value indicated in literature in order to consider the bottom surface as adequately cured (0.80). A statistically significant difference (P < 0.01) was recorded comparing Standard 20 s polymerization mode with both Standard 40 s and Soft-start 40 s polymerization modes for Esthet.X HD, Amaris and Ceram.X mono. No statistical difference was recorded for Filtek Silorane, Grandio and Filtek Supreme XT. Comparing Standard 40 s and Soft-start 40 s polymerization mode, there was no statistical difference between hardness values recorded on top and bottom surfaces.

DISCUSSION

Resin composites are widely used in restorative dentistry and specifically in posterior restorations, putting the material under constant masticatory stresses. Resin composites with better mechanical properties have been developed over these years. One of the most important parameters deciding the resin composites’ resistance to stress is the depth of cure. The effectiveness of cure depends on the filler particle type, size, quantity and on the parameters (intensity, time and polymerization modes) of the light source.[15] Effective cure of light-activated composites is also important to prevent cytotoxicity of inadequately polymerized material.[16] The optimal degree of curing throughout the bulk of a visible light-activated dental resin composite is acknowledged to be important to the clinical success of a resin composite restoration. Unfortunately, the dentist has no means of monitoring the cure of the resin surfaces not directly exposed to the curing light.[17]

Moore et al.[12] stated that one brand of composite in flowable, hybrid and packable formulations did not achieve a 2 mm depth of cure with 20 s light exposure. De Jong et al.[18] demonstrated that with high intensity light-curing units, exposure times of 10s/2 mm increment can be sufficient to obtain under in vitro conditions a high degree of conversion. These data suggest that a 2 mm buildup layering technique may not result in adequate curing of the bottom layer for such a wide range of materials and that manufacturers need to provide quantitative information about the degree of conversion at specific activation times and light intensities for their entire range of resin materials and shades so that the dentist can devise a placement technique that will ensure adequate cure of the bulk of a restoration. These findings where in disagreement with some studies that have shown that 2-mm increments were well polymerized.[7,19]

Ferracane[2] demonstrated good correlation between increasing hardness and increasing degree of conversion. Bouschlicher et al.[20] concluded that the bottom-to-top surface microhardness ratios of a composite resin proved to be an accurate reflection of bottom-to-top degree of conversion; bottom-to-top microhardness; and, degree of conversion were independent of composite composition. The development of new technologies and polymerization modes for photo-activation of restorative composite resins has also caused a great interest among researchers. However, the real advantages of these techniques are not yet totally known.[21] In the present study, 2-mm thick composite specimens were used as it ensured uniform and maximum polymerization.[11] A2 shade was selected to minimize the effects of colorants on light polymerization.[22]

The degree to which light-activated composites polymerize is proportional to the amount of light to which they are exposed.[23] Ideally, the degree of polymerization of the composite should be the same throughout its depth and the hardness ratio should be very close or equal to one. As light passes through the composite, the light intensity is greatly reduced due to light scattering, thus decreasing the effectiveness of cure at the bottom surface.[24] It was suggested that the hardness ratio should be greater than 0.8% for light activated composites to be adequately polymerized.[25] In the present study, the hardness ratio for all the tested materials was over 0.8% for Standard 20 s and 40 s and Soft-start 40 s polymerization. Denehy et al.[26] found that the top surface hardness of composites was less dependent on light intensity than the bottom surface. The top surface is actually receiving the maximum energy from the curing light.

A statistically significant difference (P < 0.01) was recorded comparing Standard 20 s polymerization mode with both, Standard 40 s and Soft-start 40 s polymerization modes, at top and bottom surfaces, for Esthet.X HD, Amaris and Ceram.X mono. No statistical difference was recorded for Filtek Silorane, Grandio and Filtek Supreme XT. These results depend on the total amount of energy reaching the composite layer and on chemical composition of the composites. At the the top surface, it has also been established that even relatively low intensity lights can cure the resin matrix to an extent almost equal to when high intensity lights are used.[27] The general lack of significance between Standard 40 s and Soft-start 40 s curing modes in top Vickers hardness found in this study corroborate the mentioned studies. At the top surface, sufficient light energy reaches the photoinitiator, thus starting the polymerization reaction.

At the bottom surfaces, a significant difference in VK was observed for all the materials, but no statistical difference was observed between Standard 40 s and Soft-start 40 s polymerization modes. This may be due to the very fast increase (5 s) of light intensity in Soft-start polymerization, while total light exposure was very similar between the two polymerization modes.

About the properties of the composite resins, the results were generally dependent on the material evaluated, especially with regard to filler features. Moraes et al. suggested that no trend towards the size or shape of fillers affected hardness; and all materials generally presented different results in comparison with one another. Grandio, for instance, presented the highest values, probably because of its large particles and the highest filler content. Nanofilled Filtek Supreme XT showed significantly higher hardness values than Esthet.X HD, Filtek Silorane and Ceram.X mono, which were all conceived for posterior restorations. In this study, only one physical property was tested on a limited number of composite resins polymerized with one type of unit. More research involving the use of other materials and multiple combinations of polymerization modes is warranted.

CONCLUSION

Curing time did not affect hardness ratio values for Filtek Silorane, Grandio and Filtek Supreme XT. The effectiveness of cure at the top and bottom surface was not affected by Soft-start polymerization mode.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Eliades GC, Vougiouklakis GJ, Caputo AA. Degree of double bond conversion in light- cured composites. Dent Mater. 1987;3:19–25. doi: 10.1016/s0109-5641(87)80055-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ferracane JL. Correlation between hardness and degree of conversion during the setting reaction of unfilled dental restorative resins. Dent Mater. 1985;1:11–4. doi: 10.1016/S0109-5641(85)80058-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Soh MS, Yap AU. Influence of curing modes on crosslink density in polymer structures. J Dent. 2004;32:321–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jdent.2004.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.da Silva EM, Poskus LT, Guimarães JG. Influence of light-polymerization modes on the degree of conversion and mechanical properties of resin composites: A comparative analysis between a hybrid and a nanofilled composite. Oper Dent. 2008;33:287–93. doi: 10.2341/07-81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Asmussen E. Restorative resins: Hardness and strength vs.Quantity of remaining double bonds. Scand J Dent Res. 1982;90:484–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0722.1982.tb00766.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ferracane JL, Greener EH. The effect of resin formulation on the degree of conversion and mechanical properties of dental restorative resins. J Biomed Mater Res. 1986;20:121–31. doi: 10.1002/jbm.820200111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aravamudhan K, Rakowski D, Fan PL. Variation of depth of cure and intensity with distance using LED curing lights. Dent Mater. 2006;22:988–4. doi: 10.1016/j.dental.2005.11.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.da Silva EM, Poskus LT, Guimarães JG, de Araújo Lima Barcellos A, Fellows CE. Influence of light polymerization modes on degree of conversion and crosslink density of dental composites. J Mater Sci Mater Med. 2008;19:1027–32. doi: 10.1007/s10856-007-3220-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Price RB, Felix CA, Andreou P. Evaluation of a dual peak third generation LED curing light. Compend Contin Educ Dent. 2005;26:331–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mobarak E, Elsayad I, Ibrahim M, El-Badrawy W. Effect of LED light-curing on the relative hardness of tooth-colored restorative materials. Oper Dent. 2009;34:65–71. doi: 10.2341/08-38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yap AU. Effectiveness of polymerization in composite restoratives claiming bulk placement: Impact of cavity depth and exposure time. Oper Dent. 2000;25:113–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moore BK, Platt JA, Borges G, Chu TM, Katsilieri I. Depth of cure of dental resin composites: ISO 4049 depth and microhardness of types of materials and shades. Oper Dent. 2008;33:408–12. doi: 10.2341/07-104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yap AU, Seneviratne C. Influence of light energy density on effectiveness of composite cure. Oper Dent. 2001;26:460–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rode KM, Kawano Y, Turbino ML. Evaluation of curing light distance on resin composite microhardness and polymerization. Oper Dent. 2007;32:571–8. doi: 10.2341/06-163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yap AU, Soh MS. Curing efficacy of a new generation high-power LED lamp. Oper Dent. 2005;30:758–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Caughman WF, Caughman GB, Shiflett RA, Rueggeberg F, Schuster GS. Correlation of cytotoxicity, filler loading and curing time of dental composites. Biomaterials. 1991;12:737–40. doi: 10.1016/0142-9612(91)90022-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Koupis NS, Martens LC, Verbeeck RM. Relative curing degree of polyacid-modified and conventional resin composites determined by surface Knoop hardness. Dent Mater. 2006;22:1045–50. doi: 10.1016/j.dental.2005.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.de Jong LC, Opdam NJ, Bronkhorst EM, Roeters JJ, Wolke JG, Geitenbeek B. The effectiveness of different polymerization protocols for class II composite resin restorations. J Dent. 2007;35:513–20. doi: 10.1016/j.jdent.2007.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Aravamudhan K, Floyd CJ, Rakowski D, Flaim G, Dickens SH, Eichmiller FC, et al. Light-emitting diode curing light irradiance and polymerization of resin-based composite. J Am Dent Assoc. 2006;137:213–23. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2006.0147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bouschlicher MR, Rueggeberg FA, Wilson BM. Correlation of bottom-to-top surface microhardness and conversion ratios for a variety of resin composite compositions. Oper Dent. 2004;29:698–704. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.de Moraes RR, Gonçalves Lde S, Lancellotti AC, Consani S, Correr-Sobrinho L, Sinhoreti MA. Nanohybrid resin composites: Nanofiller loaded materials or traditional microhybrid resins? Oper Dent. 2009;34:551–7. doi: 10.2341/08-043-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yap AU, Soh MS, Siow KS. Effectiveness of composite cure with pulse activation and soft-start polymerization. Oper Dent. 2002;27:44–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rueggeberg FA. Determination of resin cure using infrared analysis without an internal standard. Dent Mater. 1994;10:282–6. doi: 10.1016/0109-5641(94)90076-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ruyter IE, Oysaed H. Conversion in different depths of ultraviolet and visible light activated composite materials. Acta Odontol Scand. 1982;40:179–92. doi: 10.3109/00016358209012726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pilo R, Cardash HS. Post-irradiation polymerization of different anterior and posterior visible light-activated resin composites. Dent Mater. 1992;8:299–304. doi: 10.1016/0109-5641(92)90104-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pires JA, Cvitko E, Denehy GE, Swift EJ., Jr Effects of curing tip distance on light intensity and composite resin microhardness. Quintessence Int. 1993;24:517–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rueggeberg FA, Jordan DM. Effect of light-tip distance on polymerization of resin composite. Int J Prosthodont. 1993;6:364–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]