Abstract

This case report illustrates determination of prognosis and immediate resection carried out, before completing the endodontic therapy, during the surgery employed for managing a nonperiodontal problem. This case showed external pressure resorption in the distobuccal root of maxillary second molar caused by the impingement of impacted third molar. Extraction of third molar was decided when healing was not seen, despite initiating endodontic therapy in second molar. Following elevation of flap and extraction of third molar, the poor prognosis due to severe bone loss around the resorbed root was evident. But due to strategic value of second molar, it was found beneficial to employ resection. Therefore, immediate resection was carried out in the same surgical field before the completion of endodontic therapy. This prevented the need for another surgical entry with its associated trauma to carry out resection separately later. Resection followed by the completion of endodontic therapy and full crown assisted in salvaging the remaining functional portion of the tooth and prevented the occurrence of distal extension with its potential drawbacks.

Keywords: Distobuccal root, external root resorption, root resection

INTRODUCTION

Root resection therapy is said to be a treatment option for molars with periodontal, endodontic, restorative, or prosthetic problems. It is mentioned that commonly sighted indications for root resection are periodontal based, such as severe bone loss, class II or class III furcation involvement, severe recession, or dehiscence. Endodontic indications include the inability to fill a canal, root fracture, root perforation, root resorption, and root decay. Prosthetic indications include severe root proximity and root trunk fracture or decay. In a maxillary molar, root respective therapy can be used when attachment loss, caries, or a fracture involves a furcation area.[1–3] Furthermore, it is stated that root resection can be an alternative treatment in a molar tooth having endodontic–periodontal problem, such as true combined lesion where root resection may allow changing the root configuration of the part of the root to be saved.[4]

External root resorption, a condition originating in the periodontal ligament and associated with loss of cementum and/or dentin from the roots of teeth, can occur due to several causes. Pressure root resorption, due to impingement of an adjacent cyst, granuloma, neoplasm, juxtaposed roots, and impacted tooth, could be one of them.[5] Endodontic therapy is not suggested in a tooth having extensive external root resorption and extraction is often the treatment of choice.[1] However, it is suggested that root resection could be a viable treatment option to salvage and retain a part of the multirooted or molar tooth, especially of one having strategic importance.[1,6]

This case report illustrates root resection carried out before the completion of endodontic therapy and immediately during surgery, employed for eliminating the cause for external pressure resorption, to salvage the remaining portion of a strategically important tooth.

CASE REPORT

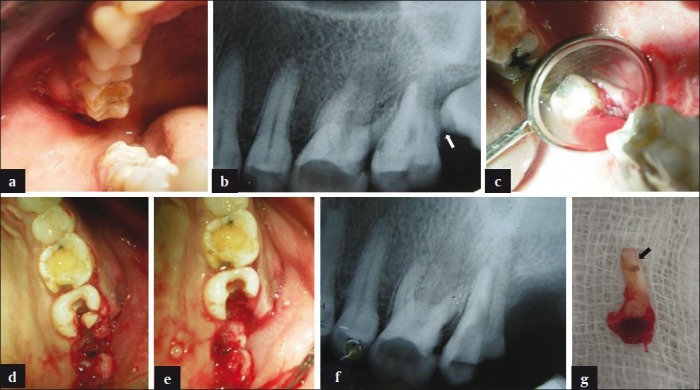

A 31-year-old female patient reported with a complaint of pain and pus discharge in the upper right second molar region, that is, 17 since 1 week. Her medical history was noncontributory. Clinical examination revealed an intraoral swelling on the buccal aspect of 17 and 18, with a sinus opening [Figure 1a]. Clinically, 17 appeared intact, whereas 18 was partially impacted; 17 was tender on percussion and gave no response to thermal and electric pulp testing. Periodontal findings were within normal limits, except for an 8 mm periodontal pocket on the distal aspect of 17. Intraoral periapical radiograph showed resorption of distobuccal root of 17 due to impingement of mesioangularly impacted 18 [Figure 1b.] Sinus opening was traced using gutta-percha point, which pointed toward the root apex of 17.

Figure 1.

(a) Clinical view of intraoral swelling in relation to 17 and 18. (b) Radiographic view showing resorption in distobuccal root of 17 (white arrow) due to impingement of 18. (c) Surgical view, following extraction of 18, revealing bone loss around distobuccal root of 17. (d) Clinical view of 17 following vertical cuts and separation of its distobuccal root. (e) Surgical view following extraction of 18 and resection of distobuccal root of 17. (f) Radiographic view following resection and extraction of distobuccal root of 17. (g) Extracted distobuccal root of 17 showing resorption (black arrow)

Following diagnosis of external pressure resorption of distobuccal root and pulpal necrosis in 17, root canal therapy was suggested. Access was opened followed by canal location and working length determination under rubber dam isolation. Root canal cleaning and shaping was carried out using K-files (Maillefer Dentsply, Baillaigues, Switzerland) and step back technique to conserve coronal radicular dentin. Canals were irrigated with 2.5% sodium hypochlorite and 0.2% chlorhexidine. Calcium hydroxide (Calcicur, Voco, Cuxhaven, Germany) was placed as an intracanal medicament.

However, sinus opening showed no healing despite changing intracanal medicament over multiple visits and the patient was suggested to undergo extraction of 18. Extraction was carried out following flap elevation under local anesthesia. Inspection of the socket revealed the exposure of resorbed distobuccal root of 17 and the poor prognosis due to extensive bone loss around the root was evident [Figure 1c]. However, 17 was a strategically important tooth due to its distal most position in the arch. Therefore, decision to resect distobuccal root was taken to salvage the remaining portion of 17. Following extraction of 18, access to the root was readily available under the reflected flap. Hence, decision to immediately resect the root in the same surgical field was taken.

Resection of distobuccal root was carried out using the vertical-cut method.[1] Two vertical cuts were initiated in the furcation and along the crown using a long shank thin, tapering diamond point. First cut was initiated on the buccal aspect, whereas the second cut was made on the distal aspect of 17. Both the vertical cuts were carried through the furcation toward the center of the tooth and connected with each other to separate the distobuccal root [Figure 1d]. Following complete separation, the root along with a portion of the crown was removed out and radiographically verified [Figure 1e and f]. The resected distobuccal root showed extensive external resorption [Figure 1g]. The remaining furcation area of 17 was smoothened using diamond points. The flap was repositioned, sutured, and postoperative instructions were given to the patient.

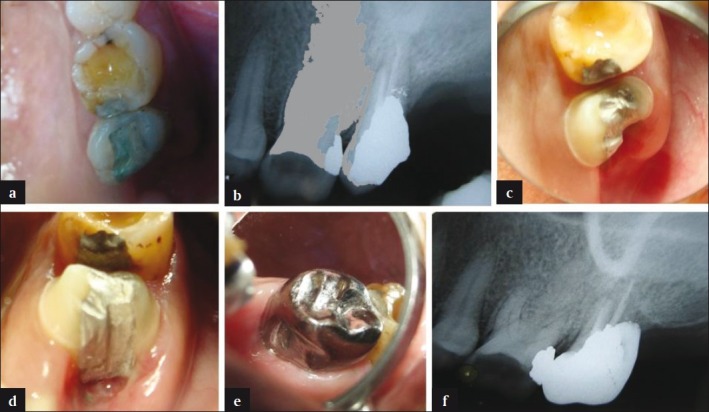

After 1 week, the sutures were removed. In the followup visit, sinus opening along with site of extraction and resection showed normal healing. Following this, remaining root canals of 17 were obturated with gutta percha (Dentsply Maillefer, Ballaigues, Switzerland), sealer (AH Plus, Dentsply Maillefer, Ballaigues, Switzerland) using lateral compaction technique. The access along with resected portion of the crown was restored with silver amalgam (Dispersalloy, Dentsply-Caulk, Milford, PA, USA) [Figure 2a and b]. In the subsequent visit, tooth preparation was done on 17 for full crown with a fluted design and knife edge finish line in the resected area [Figure 2c and 2d]. Full metal crown was fabricated with a concave contour at the resected area and cemented on 17 [Figure 2e]. At 1 year recall visit, resected 17 was found clinically asymptomatic with normal radiographic findings [Figure 2f].

Figure 2.

(a) Clinical view of amalgam foundation in 17. (b) Radiographic view following completion of endodontic therapy and amalgam foundation in 17. (c) Occlusal view showing fluted preparation in the resected area of 17. (d) Distal view showing fluted preparation in the resected area of 17. (e) Full metal crown, having concave contour at the resected area, cemented on 17. (f) One year radiographic followup view of 17

DISCUSSION

Root resections suggested for periodontal reasons are presurgically evaluated and carried out as a part of pocket elimination surgery following elevation of flap.[3,7] However, in certain situations, when the presurgical identification for resection is impossible, the need to resect the root arises at the time of surgery and if decided, root sectioning is performed during surgery.[2]

In the present case similar situation, but due to a nonperiodontal cause, occurred when poor prognosis of resorbed root was determined at the time of surgery and immediate resection was carried out. Extraction of 18 was carried out as the sinus opening showed no healing, probably due to severe bone loss between 17 and 18. Flap elevation and extraction of 18 confirmed the bone loss and poor prognosis associated with 17. However, extraction of 17 would have led to the occurrence of distal extension. Therefore, resection of strategically important 17 was found beneficial to remove its resorbed distobuccal root and to salvage its remaining portion to prevent distal extension with associated drawbacks.[8] Resection was a suitable option due to the presence of nonfused roots with intact bone support around the remaining roots of 17. Since the endodontic prognosis without resection was unpredictable and due to the convenience of already available surgical access to the resorbed root, resection was carried out immediately in the same surgical field following extraction of 18. This prevented the need for another surgical entry and its associated trauma, in case the resection would have been carried out separately later.

Since resection was accomplished in the same surgical field, it was carried out before the completion of endodontic therapy in 17. Generally, endodontic therapy is completed before root resection procedure and this has many advantages.[9,10] However, it is said that endodontic therapy should be delayed in cases in which the indication for root resection is not conclusively established. It may be completed postsurgically, as soon as possible, if prognosis appears to be favorable.[2,11]

Following root resection, maxillary molars are said to have more failures due to periodontal reasons.[12] Furthermore, radiographic identification of residual ledges or lips is difficult in maxillary molar resections.[13] Hence, a smooth resected surface without ledges or furcal lips is desirable. Vertical cut method of resection employed in this case, apart from reducing occlusal forces, allows smoothening of furcation due to good visibility and provides a desirable angle for resection.[1]

Apart from endodontic component, a successful root resection therapy requires a comprehensive evaluation of reconstructive components too.[2] Root fracture is a significant cause of failure in resected teeth. Therefore, the use of a post should be generally avoided in such cases. It is shown that placement of a post decreases the fracture resistance of a tooth.[14] However, a foundation restoration and crown are indicated following resection.[15] A foundation is required to replace the missing portion of the tooth following resection. It is suggested that foundation restoration be performed prior to resection. Foundation build up becomes increasingly difficult and technically complex if it is carried out after resection. However, in this case, foundation restoration was done after resection, as the endodontic therapy was not completed before resection. Various foundation materials, such as composite resin, amalgam, and others, have been suggested. However, it is said that the differences are of little clinical significance because full coverage crowns negate these differences and afford some protection to these foundations.[2]

In this case, amalgam was used to seal the access opening and serve as a foundation. Although amalgam has the drawbacks of causing soft tissue pigmentation (amalgam tattoo) and affecting healing,[2,16] these were of minimal concern as it was used following healing of the resected site. Amalgam has better physical properties, resist microleakage at the interface of the tooth, and less technique sensitive than composites.[17]

As a final restoration, full coverage crown was given. It is said that crown helps prevent fracture and allows the clinician to control the occlusion.[15] It is recommended that tooth preparation for a crown on resected maxillary molars should follow contour of the root trunk. Combined preparation and preparation resembling a figure 8 shape by obtaining a “barreled in” or “fluted” preparation with chamfered margins in the remaining furcation are suggested.[2,18] In the present case, the resected tooth was prepared with knife-edge finish line as it is suggested that such margins, given the limited width of the residual roots, are frequently required to avoid excessive removal of residual tooth structure. This is particularly significant in cervical area where obtaining ferrule effect is crucial.[19]

The final crown was designed to have an occlusal configuration similar to a maxillary molar. It was contoured in the remaining furcation to reduce the occlusal forces over the resection area and to follow the root contour. This resulted in a concave depression on the crown at the site of resection. Although such a contour may not offer an ideal surface for oral hygiene procedures, it is suggested that concave shape would prevent overcontouring of the crown and minimize gingival irritation.[19]

CONCLUSION

This case report highlights that to achieve favorable endodontic prognosis in a tooth showing pressure resorption, caused by impingement of an impacted tooth, may require the extraction of impacted tooth before the completion of endodontic therapy. In such a case, flap elevated for extraction may assist in ascertaining the prognosis of resorbing tooth. Furthermore, resection of resorbing root may be decided and carried out immediately in the same surgical field, like periodontal related resection, to prevent the need for a separate surgical entry later.

In a similar situation, when the impacted tooth is a maxillary third molar, root resection in adjacent strategically important tooth may aid in salvaging the remaining portion of the tooth to avoid distal extension.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Weine FS. Endodontic Therapy. 6th ed. St Louis: Mosby; 2004. pp. 1–23. (423-51). [Google Scholar]

- 2.DeSanctis M, Murphy K. The role of resective periodontal surgery in the treatment of furcation defects. Periodontol 2000. 2000;22:154–68. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0757.2000.2220110.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hempton T, Leone C. A review of root respective therapy as a treatment option for maxillary molars. J Am Dent Assoc. 1997;128:449–55. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.1997.0229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Raja VS, Emmadi P, Namasivayam A, Thyegarajan R, Rajaraman V. The periodontal - endodontic continuum: A review. J Conserv Dent. 2008;11:54–62. doi: 10.4103/0972-0707.44046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Benenati FW. Root resorption: Types and treatment. Gen Dent. 1997;45:42–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Minsk L, Polson AM. The role of root resection in the age of dental implants. Compend Contin Educ Dent. 2006;27:384–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Majzoub Z, Kon S. Tooth morphology following root resection procedures in maxillary first molars. J Periodontol. 1992;63:290–6. doi: 10.1902/jop.1992.63.4.290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stewart KL, Rudd KD, Kuebker WA. Clinical Removable Partial Prosthodontics. 2nd. St. Louis, Tokyo: Ishiyaku EuroAmerica, Inc. Publishers; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Van Swol RL, Whitsett BD. Root amputation as a predictable procedure. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1977;43:452–9. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(77)90332-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Smukler H, Tagger M. Vital root amputation- a clinical and histological study. J Periodontol. 1976;47:324–30. doi: 10.1902/jop.1976.47.6.324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schmitt S, Brown FH. Management of root-amputated maxillary molar teeth: Periodontal and prosthetic considerations. J Prosthet Dent. 1989;61:648–52. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3913(89)80034-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Park SY, Shin SY, Kye SB. Factors influencing the outcome of root-resection therapy in molars: A 10 year retrospective study. J Periodontol. 2009;80:32–40. doi: 10.1902/jop.2009.080316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Newell DH. The role of the prosthodontist in restoring root-resected molars; a study of 70 molar root resections. J Prosthet Dent. 1991;65:7–15. doi: 10.1016/0022-3913(91)90039-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guzy GE, Nichols JI. Invitro comparison of intact endodontically treated teeth with and without endo-post reinforcement. J Prosthet Dent. 1979;42:39–42. doi: 10.1016/0022-3913(79)90328-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Green E. Hemisection and root amputation. J Am Dent Assoc. 1986;112:511–8. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.1986.0050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kost WJ, Stakiw JE. Root amputation and hemisection. J Can Dent Assoc. 1991;57:42–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Phillips RW, Isler SL. Dental amalgam: An update. Compend Contin Educ Dent. 1983;44:397–402. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Appleton IE. Restoration of root-resected teeth. J Prosthet Dent. 1980;44:150–3. doi: 10.1016/0022-3913(80)90127-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sorensen JA, Martinoff JT. Intracoronal reinforcement and coronal coverage: A study of endodontically treated teeth. J Prosthet Dent. 1984;51:780–4. doi: 10.1016/0022-3913(84)90376-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]