Abstract

Purpose

Addressing psychosocial needs, including key components of psychologic distress, physical symptoms, and health promotion, is vital to cancer follow-up care. Yet little is known about who provides psychosocial care. This study examined physician-reported practices regarding care of post-treatment cancer survivors. We sought to characterize physicians who reported broad involvement in (ie, across key components of care) and shared responsibility for psychosocial care.

Methods

A nationally representative sample of medical oncologists (n = 1,130) and primary care physicians (PCPs; n = 1,021) were surveyed regarding follow-up care of breast and colon cancer survivors.

Results

Approximately half of oncologists and PCPs (52%) reported broad involvement in psychosocial care. Oncologist and PCP confidence, beliefs about who is able to provide psychosocial support, and preferences for shared responsibility for care predicted broad involvement. However, oncologists' and PCPs' perceptions of who provides specific aspects of psychosocial care differed (P < .001); both groups saw themselves as the main providers. Oncologists' confidence, PCPs' beliefs about who is able to provide psychosocial support, and oncologist and PCP preference for models other than shared care were inversely associated with a shared approach to care.

Conclusion

Findings that some providers are not broadly involved in psychosocial care and that oncologists and PCPs differ in their beliefs regarding who provides specific aspects of care underscore the need for better care coordination, informed by the respective skills and desires of physicians, to ensure needs are met. Interventions targeting physician confidence, beliefs about who is able to provide psychosocial support, and preferred models for survivorship care may improve psychosocial care delivery.

INTRODUCTION

Growth in the number of cancer survivors and their prolonged survival after diagnosis1,2 has called increased attention to the ongoing medical and psychosocial needs of this population.3,4 Post-treatment cancer care in the United States is poorly coordinated across multiple providers, with no clear delineation of responsibility5 and no formal transition from oncologists to primary care physicians (PCPs).3,6 Given the high prevalence of unmet psychosocial needs in post-treatment cancer survivors,7–9 lack of coordination may be particularly true of psychosocial care, an integral part of quality care after cancer.3,4

Psychosocial care, as defined by Jacobsen,10 encompasses multiple key components related to psychologic, behavioral, and social functioning, including treatment of psychologic distress, promotion of healthy behaviors, and management of physical symptoms (eg, fatigue) that respond to psychosocial interventions. Although unmet psychosocial needs are adversely associated with quality of life,3,4,7–13 adherence to medical treatments,4,14 and survival,15–21 physicians often fail to recognize or treat these issues3,22–33 or to refer to appropriate specialists. Fewer than half of oncologists and PCPs are confident in their knowledge about psychosocial problems after cancer, and providers disagree about the ability of PCPs to provide psychosocial support after cancer.34 Meeting the psychosocial needs of cancer survivors requires a coordinated approach for delivering psychosocial services. Understanding who is broadly involved in (ie, involved across key components) assessing psychosocial health and treating or providing treatment referral, as well as providers' approach to this care (ie, whether they perceive sole responsibility or responsibility shared with other providers) and the implications for coordinating care, would illuminate gaps to address in the future to improve psychosocial care.

To inform a new approach to psychosocial survivorship care, the current study aimed to characterize physicians who report broad involvement in psychosocial care, examine differences in physician-reported practices for specific aspects of psychosocial care delivery by provider group (oncologists v PCPs), and characterize physicians who perceived themselves as having shared responsibility for most aspects of psychosocial care. Although examining broad involvement speaks to the breadth of physician involvement in psychosocial care, examining perceptions of shared responsibility speaks to providers' approach to psychosocial care.

METHODS

Sample and Data Collection

The Survey of Physician Attitudes Regarding the Care of Cancer Survivors (SPARCCS) assessed physician-perceived practices, knowledge, and attitudes regarding post-treatment follow-up care of early-stage breast and colon cancer survivors (surveys can be requested at http://healthservices.cancer.gov/surveys/sparccs/). SPARCCS focused on these cancers because of the high prevalence of survivors and their long survivorship periods.34 Methods for SPARCCS have been reported elsewhere.34 Study approval was obtained from the National Cancer Institute Institutional Review Board and the US Office of Management and Budget. Questionnaires were mailed in 2009 to a nationally representative sample of medical oncologists and PCPs generated from the American Medical Association Physician MasterFile using stratified sampling to achieve even coverage across specialty, census region, Metropolitan Statistical Area (MSA), age, sex, and mail undeliverable status.

The SPARCCS sample consisted of 1,130 oncologists and 1,072 PCPs (overall weighted response rate, 57.7%). Nonrespondents and respondents were similar on all variables examined (age, sex, board status, specialty, region, and US v foreign training). The current analytic sample excluded PCPs who reported having never seen a breast or colon cancer survivor in clinical practice (n = 51). Excluded PCPs were more likely to be male, nonwhite, not board certified, from the south or west census region, and foreign trained (P < .05).

Measures

Most survey items were adapted from previous physician surveys.5,35–37 The item assessing confidence in knowledge was developed by SPARCCS investigators.34 Relevant survey items are available in the Data Supplement.

Demographic and practice characteristics.

Physicians provided their race/ethnicity, percent of time spent on patient care, number of patients seen per week, number of patients ever diagnosed with breast or colon cancer seen per week (oncologists) or per year (PCPs), percentage of patients uninsured or insured by Medicaid, and salary recovery.36,37 Age, sex, specialty, census region, and MSA were obtained from the American Medical Association MasterFile.

Provision of psychosocial follow-up care.

Seven components of psychosocial care were evaluated: two for psychologic care (evaluating patients for adverse psychologic events related to cancer or its treatment, treating depression or anxiety), two for health promotion (counseling on diet/physical activity, counseling on smoking cessation), and three for symptom management (treating fatigue, sexual dysfunction, and pain related to cancer). Most questions referred to care for survivors within 5 years of completing treatment for breast or colon cancer. Evaluation of patients for adverse psychologic events was assessed separately regarding breast and colon cancer survivors. Because of similarity of responses, only the items related to breast cancer are presented.

Physicians indicated their usual role in providing each aspect of psychosocial care36,37 as follows: “I order or provide this service myself”; “the PCP (for oncologists) or the oncologist (for PCPs) orders or provides this service”; “the PCP/oncologist and I share responsibility for ordering or providing this service”; “another specialist orders or provides this service”; and “I am not involved in this care.” Responses were recoded into categories of physician role: sole provider (“I order…myself”), PCP provides (for oncologists) or oncologist provides (for PCPs), shared provision (“the PCP/oncologist and I share responsibility… ”), and not involved (“another specialist orders… ” and “I am not involved… ”).

Broad involvement.

To examine the breadth of physician involvement in psychosocial care, we classified physicians as having broad involvement (yes or no) separately for each psychosocial care domain (psychologic, health promotion, symptom management). Broad involvement was defined by reporting any responsibility (sole or shared provision) for all items within each domain. Next, we created an indicator of broad involvement in overall psychosocial care (responsibility for all seven items described).

Perceptions of shared and sole responsibility for care.

To examine providers' approach to psychosocial care (shared v sole) among those involved in psychosocial care, we characterized physicians as having primarily shared provision (yes or no) separately for each care domain if they reported shared responsibility for all items within each domain. We also created an overall indicator of shared involvement defined by shared provision for ≥ five of seven psychosocial items (ie, generally shared approach to care reflected by ≥ half of the seven items and ≥ one item from each domain). Similarly, we classified physicians as having primarily sole provision for each care domain and overall psychosocial care. Some physicians reporting a mixed approach did not meet criteria for having either a shared or sole approach.

Confidence in knowledge.

Physicians reported their confidence regarding their knowledge of potential adverse psychosocial outcomes of cancer or its treatment for breast and colon cancers (separately).34 One two-level variable was created: very confident (responded very confident for breast and colon cancer) versus less confident (all others).

Beliefs about PCPs.

Physicians indicated agreement with the statement that “PCPs are better able than oncologists to provide psychosocial support for survivors of cancer” (strongly agree to strongly disagree) for breast and colon cancers (separately).35 One three-level variable was created: agree (somewhat or strongly agree for both cancers), neither agree nor disagree, and disagree (somewhat or strongly disagree for both cancers).

Preferred model of follow-up care.

Physicians indicated their preferred model of survivorship care (not specific to psychosocial care): primary responsibility assigned to oncologists, PCPs, or specialized survivorship clinics or shared responsibility between oncologists and PCPs.5 Responses were recoded according to the respondent's role: primary responsibility, shared responsibility, or someone else has primary responsibility.

Statistical Analysis

SAS (version 9.2; SAS Institute, Cary, NC) survey procedures were used to incorporate sampling weights into analyses. Estimates represent the entire population of practicing medical oncologists and PCPs and account for survey design and nonresponse.38 χ2 tests evaluated differences by physician group in broad involvement, provision of specific aspects of psychosocial care, and primarily sole provision and primarily shared provision. Within each of these three research questions, a Bonferroni correction controlled the family-wise error rate (α = 0.0125; α = 0.007; α = 0.006).

Multiple logistic regression (stratified by physician group) was used to predict broad involvement for overall psychosocial care. To balance parsimony and inclusiveness, predictors (demographics, practice characteristics, confidence in knowledge, beliefs about PCPs, preferred model of survivorship care) were included in the adjusted model if they were associated with broad involvement in bivariate tests (P < .2). Similar methods were used to predict primarily shared provision of psychosocial care; however, these models were limited to physicians classified as either having primarily shared provision or primarily sole provision.

Item nonresponse was low and was accounted for by including a missing category in frequency distributions and χ2 tests (output suppressed). For multiple logistic regression models, respondents with missing values were deleted listwise. Oncologists excluded because of missingness were older and less likely to be board certified; excluded PCPs were more likely to be foreign trained. Among both groups, those excluded were more likely to be nonwhite or of unknown race/ethnicity (all P < .05).

RESULTS

Physician characteristics are listed in Table 1. Oncologists were more likely to be male, Asian, from the northwest, and from a large MSA and to prefer primary responsibility for follow-up, see a greater proportion of uninsured patients or patients insured by Medicaid, and see ≤ 50 total patients per week, but they were less likely to be paid by salary dependent on satisfaction surveys and/or measures of quality (all P < .05). However, oncologists saw approximately 35 breast or colon cancer survivors per week, whereas PCPs saw approximately 38 survivors per year.

Table 1.

Physician Characteristics

| Characteristic | Oncologists |

PCPs |

P* | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | %† | No. | %† | ||

| Total No. | 1,130 | 1,021 | |||

| Race/ethnicity | < .001 | ||||

| Non-Hispanic white | 726 | 62.7 | 711 | 70.7 | |

| Hispanic white | 36 | 3.2 | 37 | 4.1 | |

| Non-Hispanic black | 25 | 2.2 | 46 | 4.9 | |

| Asian | 299 | 28.2 | 174 | 15.1 | |

| Other/multiple | 13 | 1.1 | 11 | 1.1 | |

| Sex | < .001 | ||||

| Male | 837 | 72.9 | 679 | 64.1 | |

| Female | 293 | 27.1 | 342 | 35.9 | |

| Region | .016 | ||||

| Northeast | 284 | 25.1 | 216 | 20.7 | |

| Midwest | 243 | 21.5 | 257 | 23.6 | |

| South | 385 | 33.9 | 327 | 34.4 | |

| West | 218 | 19.5 | 221 | 21.3 | |

| MSA | .012 | ||||

| Population ≥ 1 million | 728 | 65.6 | 623 | 61.5 | |

| All other MSAs | 402 | 34.4 | 398 | 38.5 | |

| Primary specialty | — | ||||

| Medical oncology | 553 | 47.8 | — | — | |

| Other (hematology, radiation oncology, surgical oncology) | 11 | 1.0 | |||

| Hematology/oncology | 566 | 51.3 | — | — | |

| General internal medicine | — | — | 480 | 37.8 | |

| Family medicine | — | — | 458 | 43.4 | |

| Obstetrics gynecology | — | — | 82 | 18.7 | |

| Other | — | — | 1 | 0.1 | |

| No. of patients seen per week | < .001 | ||||

| ≤ 50 | 320 | 28.9 | 140 | 13.6 | |

| 51-100 | 606 | 53.4 | 541 | 53.0 | |

| ≥ 101 | 193 | 16.4 | 321 | 31.7 | |

| No. of breast or colon cancer survivors seen per week (tertiles) | — | ||||

| Low (0–21) | 358 | 32.9 | |||

| Medium (22–39) | 362 | 31.7 | — | — | |

| High (≥ 40) | 404 | 35.4 | — | — | |

| No. of breast or colon cancer survivors seen per year (tertiles) | — | ||||

| Low (0–14) | — | — | 309 | 32.4 | |

| Medium (15–34) | — | — | 327 | 33.5 | |

| High (≥ 35) | — | — | 355 | 34.2 | |

| Percent of time spent on patient care (median split) | — | ||||

| Low (20–89) | 554 | 48.7 | — | — | |

| High (90–100) | 576 | 51.3 | — | — | |

| Low (20–93) | — | — | 494 | 49.9 | |

| High (94–100) | — | — | 527 | 50.1 | |

| Percent of patients uninsured or insured by Medicaid | < .001 | ||||

| ≤ 5 | 101 | 8.7 | 166 | 17.2 | |

| 6-10 | 260 | 22.3 | 217 | 19.9 | |

| 11-20 | 361 | 31.8 | 312 | 30.9 | |

| ≥ 21 | 338 | 30.0 | 294 | 29.2 | |

| Salary based on productivity | .019 | ||||

| Yes | 387 | 34.0 | 355 | 33.4 | |

| No/do not know | 666 | 59.2 | 636 | 63.8 | |

| Salary dependent on satisfaction surveys and/or measures of quality | < .001 | ||||

| Yes | 121 | 11.1 | 202 | 18.4 | |

| No/do not know | 981 | 86.4 | 802 | 80.2 | |

| Preferred model for overall survivorship care delivery | < .001 | ||||

| Oncologists and PCPs share responsibility | 182 | 16.0 | 407 | 37.3 | |

| I have sole primary responsibility | 643 | 56.5 | 103 | 9.3 | |

| Someone else (eg, oncologists, PCPs, or specialized survivorship clinics) has primary responsibility | 264 | 24.0 | 446 | 47.2 | |

| Age, years | .003 | ||||

| Mean | 47.2 | 48.3 | |||

| SE | 0.2 | 0.3 | |||

Abbreviations: MSA, Metropolitan Statistical Area; PCP, primary care physician.

Differences by specialty evaluated by χ2 or t tests.

Percentages do not always sum to 100 within oncologists and PCPs because of missing data.

Broad Physician Involvement in Psychosocial Follow-Up Care

Most oncologists and PCPs reported broad involvement (either sole or shared responsibility for all items) within the psychologic care, health promotion, and physical symptoms domains, and approximately half of oncologists and PCPs indicated broad involvement across all seven aspects of care (Table 2). A greater percentage of PCPs indicated broad involvement in health promotion (P < .001).

Table 2.

ONCs (n = 1,130) and PCPs (n = 1,021) Reporting Broad Involvement, Sole Provision, and Shared Provision in Psychosocial Care

| Domain of Care | Broad Involvement* |

Primarily Sole Provision† |

Primarily Shared Provision‡ |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ONCs (%) | PCPs (%) | χ2§ | P∥ | ONCs (%) | PCPs (%) | χ2 | P∥ | ONCs (%) | PCPs (%) | χ2 | P∥ | |

| Psychologic care (two items) | 78.5 | 80.3 | 1.80 | .1832 | 23.2 | 27.7 | 3.00 | .054 | 31.2 | 22.0 | 11.12 | < .001 |

| Health promotion (two items) | 79.3 | 87.2 | 25.48 | < .001 | 31.2 | 51.2 | 46.99 | < .001 | 36.6 | 22.7 | 19.93 | < .001 |

| Symptom management (three items) | 64.0 | 61.1 | 2.15 | .1454 | 20.0 | 18.7 | 0.31 | .734 | 7.5 | 12.6 | 8.96 | < .001 |

| All components (seven items) | 52.3 | 53.5 | 0.68 | .4108 | 28.0 | 37.7 | 14.03 | < .001 | 31.4 | 19.9 | 17.79 | < .001 |

Abbreviations: ONC, oncologist; PCP, primary care physician.

Broad involvement was defined by reporting either sole or shared provision of all items assessed within a specific domain (psychologic care, health promotion, or symptom management) or across all seven psychosocial items.

Sole provision was defined by reporting sole responsibility for treatment or referral for all items assessed within a specific domain (psychologic care, health promotion, or symptom management) and for ≥ five of seven psychosocial items.

Shared provision was defined by reporting shared responsibility for treatment or referral for all items assessed within a specific domain (psychologic care, health promotion, or symptom management) and for ≥ five of seven psychosocial items.

χ2 tests of differences by specialty.

P values in bold are below the Bonferroni-adjusted significance criteria of P < .0125 for broad involvement or P < .006 for sole and shared provision.

Over and above demographic and practice variables, in stratified multivariable models, oncologists and PCPs who were very confident in their knowledge were more likely to indicate broad involvement across all seven aspects of psychosocial care (all P < .01; Table 3). Oncologists who disagree, and PCPs who agree, that PCPs are better able to provide psychosocial support were more likely to report broad involvement. Finally, PCPs who preferred a shared care model were more likely to report broad involvement (all P < .05).

Table 3.

Logistic Regression Models for Broad Involvement Across Seven Components of Psychosocial Care

| Characteristic | Oncologists (n = 973) |

PCPs (n = 872) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | Wald f | OR | 95% CI | Wald f | |

| Age | 0.98* | 0.97 to 0.99 | ||||

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | Ref | |||||

| Female | 0.74 | 0.53 to 1.03 | ||||

| Race | 1.75 | |||||

| Non-Hispanic white | Ref | |||||

| Asian | 1.39 | 0.88 to 2.19 | ||||

| Other/multiple | 0.78 | 0.42 to 1.44 | ||||

| Region | 2.73† | 2.80† | ||||

| Northeast | Ref | Ref | ||||

| Midwest | 0.89 | 0.59 to 1.36 | 1.66† | 1.00 to 2.75 | ||

| South | 1.44 | 0.98 to 2.12 | 1.11 | 0.71 to 1.71 | ||

| West | 1.08 | 0.75 to 1.56 | 1.8† | 1.10 to 2.95 | ||

| MSA | ||||||

| Population > 1 million | Ref | |||||

| All other MSAs | 1.35 | 0.98 to 1.86 | ||||

| No. of patients with breast or colon cancer seen per week/year | 1.01 | 0.87 | ||||

| Low | Ref | Ref | ||||

| Medium | 1.30 | 0.90 to 1.86 | 0.91 | 0.63 to 1.32 | ||

| High | 1.13 | 0.80 to 1.60 | 1.18 | 0.80 to 1.75 | ||

| No. of patients seen per week | 3.08† | |||||

| ≤ 50 | Ref | |||||

| 51-100 | 1.36 | 0.97 to 1.89 | ||||

| ≥ 101 | 1.65* | 1.09 to 2.50 | ||||

| Percentage of patients uninsured or insured by Medicaid | 1.49 | |||||

| ≥ 21 | Ref | |||||

| 11-20 | 1.28 | 0.84 to 1.96 | ||||

| 6-10 | 1.46 | 0.96 to 2.22 | ||||

| ≥ 5 | 0.94 | 0.60 to 1.48 | ||||

| Salary dependent on productivity | ||||||

| No/unknown | Ref | |||||

| Yes | 1.18 | 0.89 to 1.56 | ||||

| Salary dependent on satisfaction surveys and/or measures of quality | ||||||

| No/unknown | Ref | |||||

| Yes | 1.25 | 0.79 to 1.98 | ||||

| Confidence in knowledge | ||||||

| Less confident | Ref | Ref | ||||

| Very confident | 1.73‡ | 1.33 to 2.25 | 2.02‡ | 1.37 to 2.99 | ||

| PCPs are better able than oncologists to provide psychosocial support | 4.18† | 13.58‡ | ||||

| Disagree | Ref | Ref | ||||

| Neither agree nor disagree | 0.73* | 0.53 to 0.99 | 1.44 | 0.85 to 2.46 | ||

| Agree | 0.43‡ | 0.23 to 0.80 | 3.05‡ | 1.94 to 4.80 | ||

| Preferred model of care delivery | 1.07 | 15.89‡ | ||||

| Oncologists and PCPs share responsibility | Ref | Ref | ||||

| I have sole primary responsibility | 0.94 | 0.63 to 1.40 | 1.51 | 0.76 to 2.98 | ||

| Someone else has primary responsibility | 0.75 | 0.48 to 1.16 | 0.40‡ | 0.27 to 0.57 | ||

NOTE. Multivariable models include all variables associated with broad involvement in bivariate models at P < .2.

Abbreviations: MSA, Metropolitan Statistical Area; OR, odds ratio; PCP, primary care physician; Ref, reference group.

P < .01.

P < .05.

P < .001.

Provision of Specific Aspects of Psychosocial Care

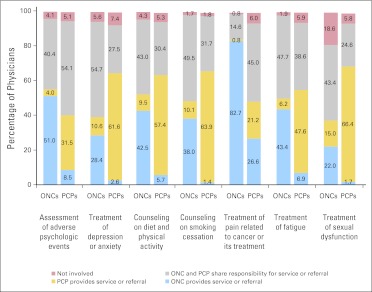

Oncologists' and PCPs' reports of psychosocial care provision differed (P < .001) for all seven items (Fig 1). Notably, oncologists overwhelmingly reported sole provision for treating pain related to cancer (82.7%), whereas they reported a relative lack of involvement in treating sexual dysfunction (22.2% sole provision, 42.4% shared provision, 15.0% PCP, 18.6% no involvement). Over 60% of PCPs indicated sole provision for treating depression or anxiety, counseling for smoking cessation, and treating sexual dysfunction.

Fig 1.

Physician-reported practices for delivery of psychosocial follow care. Percentages do not always sum to 100 within oncologists (ONCs) and primary care physicians (PCPs) because of missing data. For treatment of sexual dysfunction, 18.6% of oncologists said they were not involved, such that 14.2% of oncologists reported “another specialist orders or provides this care” and 4.2% reported “I am not involved in this care.” There were significant differences by physician group in reported provision of care for all seven items assessed (P < .001): assessment of adverse psychologic events: χ2 = 22.2; treatment of anxiety or depression: χ2 = 72.0; counseling on diet and physical activity: χ2 = 14.0; counseling on smoking cessation: χ2 = 48.1; treatment of pain related to cancer or its treatment: χ2 = 227.4; treatment of fatigue: χ2 = 6.3; treatment of sexual dysfunction: χ2 = 120.7.

Perceptions of Shared Responsibility for Psychosocial Follow-Up Care

Oncologists were more likely than PCPs to report shared provision for psychologic care, health promotion, and psychosocial care overall, whereas PCPs were more likely to report shared provision for management of physical symptoms and sole provision for health promotion and psychosocial care overall (all P < .001; Table 2).

Over and above demographic and practice variables, in stratified multivariable models, oncologists who were confident in knowledge, neither agreed nor disagreed that PCPs were better able to provide psychosocial support, and preferred care models other than shared care were less likely to be classified as having primarily shared provision (all P < .01; Table 4). PCPs who agreed they were better able to provide psychosocial support and preferred primary responsibility for overall survivorship care were also less likely to be classified as having primarily shared provision (all P < .01).

Table 4.

Logistic Regression Models for Primarily Shared Compared With Primarily Sole Provision Across Seven Components of Psychosocial Care

| Characteristic | Oncologists (n = 676) |

PCPs (n = 623) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | Wald f | OR | 95% CI | Wald f | |

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | Ref | Ref | ||||

| Female | 0.83 | 0.55 to 1.25 | 1.43 | 0.88 to 2.34 | ||

| Race | 3.07 | 1.80 | ||||

| Non-Hispanic white | Ref | Ref | ||||

| Asian | 0.59 | 0.37 to 0.95 | 0.68 | 0.38 to 1.22 | ||

| Other/multiple | 0.52 | 0.20 to 1.36 | 0.54 | 0.24 to 1.22 | ||

| Region | 1.31 | |||||

| Northeast | Ref | |||||

| Midwest | 0.61 | 0.33 to 1.10 | ||||

| South | 0.66 | 0.41 to 1.06 | ||||

| West | 0.76 | 0.42 to 1.36 | ||||

| MSA | ||||||

| Population > 1 million | Ref | |||||

| All other MSAs | 1.18 | 0.82 to 1.70 | ||||

| No. of patients with breast or colon cancer seen per week/year | 1.21 | |||||

| Low | Ref | |||||

| Medium | 1.37 | 0.86 to 2.17 | ||||

| High | 1.03 | 0.63 to 1.67 | ||||

| No. of patients seen per week | 1.89 | 2.49 | ||||

| ≤ 50 | Ref | Ref | ||||

| 51-100 | 1.17 | 0.74 to 1.85 | 1.85 | 0.93 to 3.69 | ||

| ≥ 101 | 0.73 | 0.41 to 1.32 | 1.17 | 0.56 to 3.24 | ||

| Percent time spent on patient care | ||||||

| High | Ref | Ref | ||||

| Low | 0.99 | 0.69 to 1.42 | 0.73 | 0.49 to 1.08 | ||

| Salary dependent on productivity | ||||||

| No/unknown | Ref | |||||

| Yes | 1.30 | 0.89 to 1.91 | ||||

| Confidence in knowledge | ||||||

| Less confident | Ref | Ref | ||||

| Very confident | 0.58* | 0.40 to 0.86 | 0.67 | 0.42 to 1.06 | ||

| PCPs are better able than oncologists to provide psychosocial support | ||||||

| Disagree | Ref | 4.75† | Ref | 13.44* | ||

| Neither agree nor disagree | 1.97‡ | 1.24 to 3.12 | 0.92 | 0.49 to 1.75 | ||

| Agree | 2.01 | 0.94 to 4.32 | 0.32* | 0.18 to 0.58 | ||

| Preferred model of care delivery | 7.75* | 5.46‡ | ||||

| Oncologists and PCPs share responsibility | Ref | Ref | ||||

| I have sole primary responsibility | 0.43* | 0.27 to 0.67 | 0.28‡ | 0.12 to 0.65 | ||

| Someone else has primary responsibility | 0.46* | 0.28 to 0.75 | 1.11 | 0.67 to 1.83 | ||

NOTE. Multivariable models include all variables associated with shared provision involvement in bivariate models at P < .2.

Abbreviations: MSA, Metropolitan Statistical Area; OR, odds ratio; PCP, primary care physician; Ref, reference group.

P < .001.

P < .05.

P < .01.

DISCUSSION

This study presents current physician-perceived involvement in delivering psychosocial care, defined broadly,10 to post-treatment cancer survivors. Approximately half of oncologists and PCPs reported broadly treating psychosocial needs. In light of the recognition of psychosocial care by the Institute of Medicine as integral to quality survivorship care,3,4 these perceptions of involvement are mixed news. The robust association between confidence and broad involvement suggests that additional training might increase the depth and breadth of involvement in psychosocial care for PCPs and oncologists. However, expecting a single provider to be solely responsible for all survivors' psychosocial needs may not be feasible in today's health care system. Survivors can receive comprehensive care from multiple providers if care is well coordinated, with clear delineation of responsibility for care.

These results suggest that oncologists' and PCPs' perceptions of who delivers specific aspects of care differ substantially; each frequently endorsed his or her own provider group as involved in this care and rarely endorsed the other as usual providers. Similar to previous work5,39 demonstrating that both oncologists and PCPs perceived themselves as the prominent providers of surveillance and general preventive health care, the overlap between oncologist- and PCP-reported psychosocial care provision seems, at first glance, to reflect duplication of services. However, that is inconsistent with research documenting inadequate provision of psychosocial interventions and survivors' perceptions of unmet needs.3,7,9,11,23,26,40–42 Although providers feel responsible for providing psychosocial treatment, they may not regularly inquire about or recognize survivors' psychosocial needs.29,31,32 These results also may indicate a lack of clear delineation of responsibility among providers or lack of explicit transfer of responsibility for survivors' health care from oncology to primary care after cancer treatment because of a lack of clinical guidelines for post-treatment psychosocial care.10 Apparent overlap in perceived responsibility might also reflect involvement at different times (eg, perhaps oncologists responded regarding involvement within the first year of treatment, whereas PCPs responded regarding involvement closer to 5 years post-treatment).

Physician perceptions of the current delineation of responsibility for care inform efforts to delineate who should provide which components of care. PCPs were more likely than oncologists to report broad involvement in health promotion and to perceive such care as their sole responsibility. Thus, health promotion may be an area that could be primarily transferred to primary care rather than maintained in oncology. Alternatively, perceptions of managing physical symptoms were dependent on the symptom assessed and revealed the lowest proportions of broad involvement. Oncologists overwhelmingly identified themselves as the sole providers for cancer-related pain. Conversely, two thirds of PCPs reported sole provision for treating sexual dysfunction, whereas oncologists more readily endorsed PCPs or other specialists as the providers for sexual dysfunction, despite the fact that sexual dysfunction is a concern for many survivors.43 Delineation of responsibility for treatment of numerous diverse physical symptoms after cancer (eg, cognitive complaints, lymphedema) is complex and requires further investigation.

Current shared approaches to care were predicted by physician attitudes about the abilities of other providers and preferences for models of survivorship care other than those assigning primary responsibility to oncologists. Efforts may be needed to address concerns of physicians with relatively independent approaches to survivorship care if shared approaches are to be more readily accepted by the medical community. Other unmeasured physician preferences (eg, oncologists' desire to maintain a balance of in-treatment and post-treatment patients in their practice44) should also be considered as new approaches to survivorship care are developed.

The current findings have implications for several movements in survivorship care. Calls have been made for a shared-care model of cancer-related follow-up that includes both primary care and cancer specialists,3,6 for risk-stratified care in which the provider and frequency of care depend on patient needs and preferences,6,45,46 and for the use of written survivorship care plans (SCPs) to aid communication among providers and designate which components of care should be provided by whom.3,27 Approaches to survivorship care planning and coordination that emphasize the respective skills and desires of physicians, the needs of survivors, and communication among all parties (survivors, oncologists, PCPs, and other clinicians) should be considered. Confusion among providers, as well as between providers and survivors, regarding provision of psychosocial care may negatively affect care quality3 and likely contribute to persistent psychosocial needs. The take-home message is that understanding current practices and factors associated with different approaches to psychosocial care will inform discussions about how this vital aspect of survivors' post-treatment care should be addressed.

Several limitations of this study should be considered. Actual physician behavior may differ from self-reported behavior. Actual physician involvement in psychosocial care is likely lower than reported. Furthermore, the survey addressed usual practice habits; we cannot assess care in the context of any specific patient. It is also unclear whether physician responses reflect only their behavior or also that of additional staff (eg, nurses), when in the 5 years after completion of cancer treatment they perceive responsibility, and whether they responded regarding breast cancer, colon cancer, or both. This study did not directly assess communication among providers, the frequency or quality of care delivered, or whether care appropriately matched patient need. Furthermore, results cannot be generalized to survivors of cancers that are rarer, have fewer long-term survivors, or are associated with greater psychosocial needs. Finally, this study characterized physicians who perceived shared responsibility for specific aspects of care (eg, both physician groups treat depression and fatigue). Although there are other ways to define shared care (eg, one provider treats depression and the other treats fatigue), understanding characteristics associated with the current definition of a shared approach informs efforts to improve psychosocial care delivery.

This study is a first step in understanding who provides psychosocial care and the implications for coordination of comprehensive follow-up care. Future studies should measure actual physician behavior (eg, direct observation, record review), including testing methods to increase communication among providers (eg, determining the optimal method of developing SCPs). Although PCPs feel more prepared for survivorship care after receiving a SCP,47 our results suggest that input from both oncologists and PCPs regarding their respective skills and desires may improve the coordination and delivery of post-treatment psychosocial care. The effect of different models of survivorship care on patient outcome, physician burden, and cost should also be examined. Finally, more research is needed on patient preferences related to delivery of psychosocial care (eg, confidence in PCPs' ability to manage physical symptoms).

Ultimately, a new approach to survivorship care that emphasizes the comprehensive assessment and treatment of psychosocial needs in addition to other more commonly recognized aspects of survivorship care (eg, surveillance, preventive health) is needed. Psychosocial survivorship care is complex, and the expertise of oncologists, PCPs, and other professionals is needed at different points along the cancer continuum. This article identifies potentially modifiable physician factors (confidence, beliefs about who is able to provide psychosocial support, and preferred models for survivorship care) to target for promotion of improved comprehensiveness, continuity, and quality of survivorship care.

Supplementary Material

Appendix

Acknowledgment

We thank Timothy S. McNeel (Information Management Services, Rockville, MD) for his assistance with the statistical analyses.

Footnotes

Supported by Contract No. HHSN261200700068C from the National Cancer Institute and by intramural research funds from the American Cancer Society Behavioral Research Center.

Presented in part at the 32nd Annual Scientific Sessions of the Society of Behavioral Medicine, Washington, DC, April 27-30, 2011.

The views expressed in the report do not necessarily represent the views of the US federal government or the American Cancer Society.

Authors' disclosures of potential conflicts of interest and author contributions are found at the end of this article.

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The author(s) indicated no potential conflicts of interest.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: All authors

Collection and assembly of data: Julia H. Rowland

Data analysis and interpretation: All authors

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

REFERENCES

- 1.Jemal A, Clegg LX, Ward E, et al. Annual report to the nation on the status of cancer, 1975-2001, with a special feature regarding survival. Cancer. 2004;101:3–27. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Howlader N, Noone AM, Krapcho M, et al. SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975-2008. http://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2008/ [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hewitt M, Greenfield S, Stovall E, editors. From Cancer Patient to Cancer Survivor: Lost in Transition. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Adler NE, Page AEK, editors. Cancer Care for the Whole Patient: Meeting Psychosocial Healthcare Needs. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2008. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cheung WY, Neville BA, Cameron DB, et al. Comparisons of patient and physician expectations for cancer survivorship care. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:2489–2495. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.3232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Oeffinger KC, McCabe MS. Models for delivering survivorship care. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:5117–5124. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.07.0474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lobb EA, Joske D, Butow P, et al. When the safety net of treatment has been removed: Patients' unmet needs at the completion of treatment for haematological malignancies. Patient Educ Couns. 2009;77:103–108. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2009.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McDowell ME, Occhipinti S, Ferguson M, et al. Predictors of change in unmet supportive care needs in cancer. Psychooncology. 2010;19:508–516. doi: 10.1002/pon.1604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Armes J, Crowe M, Colbourne L, et al. Patients' supportive care needs beyond the end of cancer treatment: A prospective, longitudinal survey. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:6172–6179. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.22.5151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jacobsen PB. Clinical practice guidelines for the psychosocial care of cancer survivors: Current status and future prospects. Cancer. 2009;115:4419–4429. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Recklitis CJ, Sanchez-Varela V, Bober S. Addressing psychological challenges after cancer: A guide for clinical practice. Oncology (Williston Park) 2008;22:11–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Holland J, Weiss T. The new standard of quality cancer care: Integrating the psychosocial aspects in routine cancer from diagnosis through survivorship. Cancer J. 2008;14:425–428. doi: 10.1097/PPO.0b013e31818d8934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stark D, Kiely M, Smith A, et al. Anxiety disorders in cancer patients: Their nature, associations, and relation to quality of life. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:3137–3148. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.08.549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ell K, Sanchez K, Vourlekis B, et al. Depression, correlates of depression, and receipt of depression care among low-income women with breast or gynecologic cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:3052–3060. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.08.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ruden E, Reardon DA, Coan AD, et al. Exercise behavior, functional capacity, and survival in adults with malignant recurrent glioma. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:2918–2923. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.34.9852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Giese-Davis J, Collie K, Rancourt KM, et al. Decrease in depression symptoms is associated with longer survival in patients with metastatic breast cancer: A secondary analysis. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:413–420. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.28.4455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pinquart M, Duberstein PR. Depression and cancer mortality: A meta-analysis. Psychol Med. 2010;40:1797–1810. doi: 10.1017/S0033291709992285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Satin JR, Linden W, Phillips MJ. Depression as a predictor of disease progression and mortality in cancer patients: A meta-analysis. Cancer. 2009;115:5349–5361. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chen AM, Chen LM, Vaughan A, et al. Tobacco smoking during radiation therapy for head-and-neck cancer is associated with unfavorable outcome. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2011;79:414–419. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2009.10.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen X, Lu W, Zheng W, et al. Exercise after diagnosis of breast cancer in association with survival. Cancer Prev Res (Phila) 2011;4:1409–1418. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-10-0355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kenfield SA, Stampfer MJ, Chan JM, et al. Smoking and prostate cancer survival and recurrence. JAMA. 2011;305:2548–2555. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Arora NK, Reeve BB, Hays RD, et al. Assessment of quality of cancer-related follow-up care from the cancer survivor's perspective. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:1280–1289. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.32.1554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bober SL, Recklitis CJ, Campbell EG, et al. Caring for cancer survivors: A survey of primary care physicians. Cancer. 2009;115:4409–4418. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Maly RC, Umezawa Y, Leake B, et al. Mental health outcomes in older women with breast cancer: Impact of perceived family support and adjustment. Psychooncology. 2005;14:535–545. doi: 10.1002/pon.869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Reuben SH. Living beyond cancer: Finding new balance—President's Cancer Panel 2003-2004 annual report. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, Department of Health and Human Services; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jacobsen PB, Shibata D, Siegel EM, et al. Evaluating the quality of psychosocial care in outpatient medical oncology settings using performance indicators. Psychooncology. 2010;20:1221–1227. doi: 10.1002/pon.1849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hewitt M, Ganz PA. Implementing Cancer Survivorship Care Planning. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jacobsen PB, Ransom S. Implementation of NCCN distress management guidelines by member institutions. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2007;5:99–103. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2007.0010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Passik SD, Dugan W, McDonald MV, et al. Oncologists' recognition of depression in their patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16:1594–1600. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1998.16.4.1594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Eakin EG, Strycker LA. Awareness and barriers to use of cancer support and information resources by HMO patients with breast, prostate, or colon cancer: Patient and provider perspectives. Psychooncology. 2001;10:103–113. doi: 10.1002/pon.500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Merckaert I, Libert Y, Delvaux N, et al. Factors that influence physicians' detection of distress in patients with cancer: Can a communication skills training program improve physicians' detection? Cancer. 2005;104:411–421. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Werner A, Stenner C, Schüz J. Patient versus clinician symptom reporting: How accurate is the detection of distress in the oncologic after-care? Psychooncology. doi: 10.1002/pon.1975. [epub ahead of print on May 4, 2011] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sabatino SA, Coates RJ, Uhler RJ, et al. Provider counseling about health behaviors among cancer survivors in the United States. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:2100–2106. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.6340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Potosky AL, Han PK, Rowland J, et al. Differences between primary care physicians' and oncologists' knowledge, attitudes and practices regarding the care of cancer survivors. J Gen Intern Med. 2011;26:1403–1410. doi: 10.1007/s11606-011-1808-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Del Giudice ME, Grunfeld E, Harvey BJ, et al. Primary care physicians' views of routine follow-up care of cancer survivors. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:3338–3345. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.4883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ayanian JZ, Zaslavsky AM, Arora NK, et al. Patients' experiences with care for lung cancer and colorectal cancer: Findings from the Cancer Care Outcomes Research and Surveillance Consortium. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:4154–4161. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.27.3268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Malin JL, Ko C, Ayanian JZ, et al. Understanding cancer patients' experience and outcomes: Development and pilot study of the Cancer Care Outcomes Research and Surveillance patient survey. Support Care Cancer. 2006;14:837–848. doi: 10.1007/s00520-005-0902-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Thomas DR, Rao JNK. Small-sample comparisons of level and power for simple goodness-of-fit statistics under cluster sampling. J Am Stat Assoc. 1987;82:630–636. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ganz PA, Kwan L, Somerfield MR, et al. The role of prevention in oncology practice: Results from a 2004 survey of American Society of Clinical Oncology members. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:2948–2957. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.05.8321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.McDowell ME, Occhipinti S, Ferguson M, et al. Predictors of change in unmet supportive care needs in cancer. Psychooncology. 2010;19:508–516. doi: 10.1002/pon.1604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lewis RA, Neal RD, Hendry M, et al. Patients' and healthcare professionals' views of cancer follow-up: Systematic review. Br J Gen Pract. 2009;59:248–259. doi: 10.3399/bjgp09X453576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hewitt ME, Bamundo A, Day R, et al. Perspectives on post-treatment cancer care: Qualitative research with survivors, nurses, and physicians. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:2270–2273. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.10.0826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Baker F, Denniston M, Smith T, et al. Adult cancer survivors: How are they faring? Cancer. 2005;104:2565–2576. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wood ML, McWilliam CL. Cancer in remission: Challenge in collaboration for family physicians and oncologists. Can Fam Physician. 1996;42:899–904. 907-910. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Magee CE, Hillan JA, Badger SA, et al. Risk stratification as a means of reducing the burden of follow-up after completion of initial treatment for breast cancer. Surgeon. 2011;9:61–64. doi: 10.1016/j.surge.2010.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wallace WH, Blacklay A, Eiser C, et al. Developing strategies for long term follow up of survivors of childhood cancer. BMJ. 2001;323:271–274. doi: 10.1136/bmj.323.7307.271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hausman J, Ganz PA, Sellers TP, et al. Journey forward: The new face of cancer survivorship care. J Oncol Pract. 2011;7:e50s–e56s. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2011.000306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.