Abstract

Objectives

To describe: a. the prevalence and individual and network characteristics of group sex events (GSE) and GSE attendees; and b. HIV/STI discordance among respondents who said they went to a GSE together.

Methods and Design

In a sociometric network study of risk partners (defined as sexual partners, persons with whom respondents attended a GSE, or drug-injection partners) in Brooklyn, NY, we recruited a high-risk sample of 465 adults. Respondents reported on GSE attendance, the characteristics of GSEs, and their own and others’ behaviors at GSEs. Sera and urines were collected and STI prevalence was assayed.

Results

Of the 465 participants, 36% had attended a GSE in the last year, 26% had sex during the most recent of these GSEs, and 13% had unprotected sex there. Certain subgroups (hard drug users, men who have sex with men, women who have sex with women, and sex workers) were more likely to attend and more likely to engage in risk behaviors at these events. Among 90 GSE dyads in which at least one partner named the other as someone with whom they attended a GSE in the previous three months, STI/HIV discordance was common (HSV-2: 45% of dyads, HIV: 12% of dyads, Chlamydia: 21% of dyads). Many GSEs had 10 or more participants, and multiple partnerships at GSEs were common. High attendance rates at GSEs among members of large networks may increase community vulnerability to STI/HIV, particularly since network data show that almost all members of a large sociometric risk network either had sex with a GSE attendee or had sex with someone who had sex with a GSE attended.

Conclusions

Self-reported GSE attendance and participation was common among this high-risk sample. STI/HIV discordance among GSE attendees was high, highlighting the potential transmission risk associated with GSEs. Research on sexual behaviors should incorporate measures of GSE behaviors as standard research protocol. Interventions should be developed to reduce transmission at GSEs.

Keywords: group sex, HIV, sexually transmitted infections, discordant couples, sexual networks, social networks

INTRODUCTION

Although group sex events (GSE) among men who have sex with men (MSM) in gay sex venues have been a public health concern since the early 1980s,[1–6] much less attention has been paid to GSE among other populations. Most public health research on group sex activity among non-MSM is targeted at early or middle adolescents[7–10], limited to asking one or two questions about group sex participation among sexually transmitted infection (STI) and family planning clinic patients[11; 12] or involves ethnographic information from relatively small samples.[10; 13]

GSE range from large, events at semi-publicly advertised locations to spontaneous events among small groups of friends or acquaintances. They potentially carry great epidemiologic significance for the community’s STI/HIV infection rate and the epidemic levels reached. GSEs where high rates of sexual partnership exchange occur may catalyze STI/HIV transmission. In particular, introduction of primary (acute) HIV infection into the sexual partnership pool at a GSE may result in efficient transmission to multiple individuals within a short period of time, given the heightened transmission probability at this stage of HIV infection. [14–16] GSEs also may amplify population-level STI/HIV transmission rates if GSE participants have short sexual/injection network paths to large numbers of other people. Co-infection with other STI pathogens [19–23]and high-risk sexual partnership patterns—including concurrent partnerships or rapid partner change[24–30]—may further increase HIV transmission within sexual networks of GSE attendees. [16]

We used data collected during an HIV risk network study in an impoverished neighborhood in Brookyn, NY affected by high levels of STI/HIV to describe the prevalence and characteristics of GSE and to assess potential for STI/HIV transmission risk at GSE.[31] We thus describe the prevalence of and respondent factors associated with group sex event (GSE) attendance and participation; GSE-level characteristics; sexually transmitted infection (STI) and HIV discordance among GSE attendees; and the graphical distribution GSE attendees within their sexual and drug use networks.

METHODS

Sample

During a sociometric study of risk network patterns of young adults, injection drug users (IDUs) and other populations in Bushwick, 465 respondents 18 years of age or older were recruited, between 2002 and 2004. Bushwick is a primarily-Latino section of Brooklyn, NY. Since overall study aims included interest in sexual linkage distances between young adults and IDUs in the community, index cases (“seeds”) were recruited in one of several ways: 66 from a population-representative sample of 18 to 30 year old Bushwick youth recruited door-to-door within randomly-selected face blocks; a convenience sample of 38 IDU seeds who had injected drugs within the prior 3 months and either had visible track marks and/or provided other evidence, during detailed verbal questioning, of having injected during the prior 3 months; and 8 seeds who were recruited as participants in a gay sex party subculture. All seeds resided in Bushwick. We also recruited 353 respondents who were risk partners of one or more of the 112 seeds or were risk partners of such partners or of their partners. Risk partners were defined as sexual partners, persons with whom respondents attended a GSE—but did not necessarily have sex, or persons with whom they injected drugs (but did not necessarily share syringes/equipment) in the last three months. Each index respondent was asked to name and, later in the interview, to provide locator information for up to 10 people with whom they had had sex in the last 3 months; up to 2 with whom they had attended a group sex event during the same time period; and, if the index respondent injected drugs, up to five people with whom they had injected drugs in the last 3 months. (When we started recruiting attendees at gay group sex parties and their networks late in the project, the maximum number of group sex nominees was increased to 8). Network sampling consisted of recruiting named partners. These partners were interviewed as well, and we attempted to interview their partners and their partners’ partners; thus, three “generations” of contacts were recruited. Minor adjustments to these rules are described elsewhere.[31]

This sample is thus not a probability sample. It shares one characteristic with respondent-driven samples and with most other community risk network samples—people with more partners are more likely to be selected. Since recruitment chains were short, and the 35 IDU seeds were not a probability sample, it was not possible to adjust the data statistically for this bias.

Ethical approval for all procedures was obtained by the Institutional Review Board of the National Development and Research Institutes, Inc.

Measures

Face-to-face structured interviews were conducted in confidential settings after obtaining informed consent. The interview contained sections on sociodemographics, sexual and drug behaviors, and whom respondents had had sex with, attended a GSE with, or injected drug with in the last three months. In addition, respondents reported whether they had attended a GSE in the past 12 months. Those who had attended a GSE were asked a limited number of questions about their sexual partnerships and condom use during sex at the last GSE they attended. Unprotected sexual activity at GSEs was defined as reporting any sex without a condom at the last GSE attended.

Characteristics of GSEs were also obtained. Based on results from preliminary fieldwork, we asked about three types of GSEs: a party with a back room, where some party attendees may go to have sex with one or more persons; a threesome, foursome, or larger gathering in which participants get together for the express purpose of having sex; and a party with a professional sex worker, where one or more people are paid to have sex with the guests. At each GSE type, some or all attendees engaged in sexual activity. The three GSE types were not mutually exclusive, thus attendees may have attended more than one type of event in the last year. During analysis, respondents were categorized into three mutually exclusive groups based on which of these three types of GSE they had most recently attended. In this analysis, “other GSE” was defined as parties with professional sex workers or parties where multiple events occurred (e.g., parties with both a back room and a professional sex worker).

Respondents were asked to describe how many people were present at the last GSE they attended as well as the apparent racial/ethnic and gender distributions of these attendees. They were also asked about how many attendees used alcohol and drugs at this event, about sexual partnerships among other attendees, and about condom availability and use at the event.

Assays

After obtaining separate informed consent, 10 ml of blood and 10 ml of urine were collected. Blood was tested at Bio- Reference Laboratories using standard methods (Elmwood Park, NJ) for HIV (EIA/WB) and anti-HSV-2 (type specific FOCUS EIA). Urine was tested for Chlamydia (BDProbeTec Amplified DNA assay). See Friedman, et al[31] for details.

Data Analysis

We used SAS to perform statistical analyses (SAS Institute, Version 9.1.3, Cary, NC). We calculated frequencies of respondent demographic, behavioural, and STI indicators. In bivariable analyses, we examined respondent characteristics by GSE variables including attendance, sexual activity, and unsafe sexual activity at GSEs; respondent sexual behaviour at the event by GSE type; and GSE characteristics by GSE type and sex/gender. As mentioned above, statistical adjustment for sampling procedures was not feasible.

Ninety dyads were identified in which both respondents were interviewed and in which at least one respondent named the other as someone with whom they attended a group sex event in the previous three months (though they may not have had sex with each other at this event or, indeed, ever). A dyad was defined as being discordant for a given STI (HIV, HSV-2 or chlamydia) if one and only one member of the dyad tested positive.

We used UCINET (Analytic Technologies, Version V for Windows, Natick, MA) to construct diagrams of the sexual and drug use risk interaction among study respondents, and used these to describe the distribution of GSE attendees within the network structure and the implications of this for community vulnerability.

RESULTS

Sample Characteristics

Greater than half the sample was male (57%) (Table 1). Specifically, the sample was composed of men who have ever had sex with men (MSM) (15%), other men (43%), women who have ever had sex with women (WSW) (18%) and other women (25%). The mean age was 31 years. A majority of the 465 participants was Latino (71%), 20% were black, and 10% were of other race/ethnicity.

Table 1.

Sample Characteristics and Group Sex Activities by Select Participant Characteristics

| %s in columns III and IV are %s of the total sample | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| I. Total | II. Attended | III. Had Sex | IV. Had Unsafe Sex | |||||

| N | % | % | p-value | % | p-value | % | p-value | |

| Total | 465 | 100 | 36% of 465 | 26% of 465 | 13% of 465 | |||

| Age | ||||||||

| 18–24 | 156 | 34 | 38 | .2115 | 24 | .5437 | 11 | .4134 |

| 25–30 | 100 | 22 | 39 | 25 | 10 | |||

| 31–40 | 115 | 25 | 37 | 31 | 16 | |||

| 41 or older | 94 | 20 | 27 | 26 | 16 | |||

| Race/Ethnicity | ||||||||

| Latina/o | 328 | 71 | 34 | .2184 | 24 | .0324 | 11 | .0128 |

| Black | 92 | 20 | 43 | 37 | 22 | |||

| Other | 45 | 10 | 31 | 22 | 7 | |||

| Hardest drug ever used | ||||||||

| None/Marijuana | 114 | 25 | 25 | .0032 | 12 | .0004 | 4 | .0025 |

| Non-injected heroin/cocaine | 82 | 18 | 48 | 28 | 12 | |||

| Crack | 69 | 15 | 45 | 39 | 23 | |||

| IDU | 200 | 43 | 35 | 29 | 15 | |||

| Sex | ||||||||

| Women | 199 | 43 | 28 | 0.003 | 21 | 0.030 | 11 | 0.3040 |

| Men | 266 | 57 | 42 | 30 | 14 | |||

| Gender/Sexuality | ||||||||

| WSW** | 82 | 18 | 51 | <.0001 | 45 | <.0001 | 26 | <.0001 |

| Other Female | 117 | 25 | 12 | 4 | 1 | |||

| MSM** | 68 | 15 | 71 | 63 | 31 | |||

| Other Male | 198 | 43 | 32 | 19 | 9 | |||

| Traded Sex for Money Last 12 Months | ||||||||

| No | 345 | 74 | 26 | <.0001 | 14 | <.0001 | 8 | <.0001 |

| Yes | 120 | 26 | 66 | 60 | 28 | |||

| Gay Group Sex Subculture Sample | ||||||||

| No | 436 | 94 | 33 | <.0001 | 22 | <.0001 | 11 | <.0001 |

| Yes | 29 | 6 | 83 | 83 | 48 | |||

| HIV | ||||||||

| Positive | 44 | 10 | 39 | .6505 | 36 | .0973 | 12 | .4752 |

| Negative | 395 | 90 | 35 | 25 | 16 | |||

| HSV-2 | ||||||||

| Positive | 221 | 49 | 37 | .5678 | 29 | .2245 | 14 | .4240 |

| Negative | 226 | 51 | 35 | 24 | 12 | |||

| Chlamydia | ||||||||

| Positive | 30 | 7 | 57 | .0190 | 43 | .0336 | 27 | .0433* |

| Negative | 411 | 93 | 35 | 26 | 12 | |||

| Tested positive on at least one of the above 3 infections | ||||||||

| Yes | 253 | 58 | 38 | .3430 | 30 | .1450 | 14 | .4370 |

| No | 180 | 42 | 34 | 23 | 12 | |||

Note: p-values reported from chi-square tests of independence unless otherwise noted.

• Fisher’s Exact Test

• ** Same sex partnership history used in the analysis was based on behavior, not self-reported sexual orientation. Hence, WSW are women who reported ever having sex with a woman. MSM are men who reported ever having sex with a man. The vast majority of WSW and a large majority of MSMs also had partners of the opposite sex. Among WSW, only 8 (9.9%) reported no male sexual partners in the past 3 months, and only 1 had NEVER had sex with a man in her life). Among MSM, 36% reported NO female sex partners in the past three months and only 1 had never had sex with a woman. Women who have sex with women and perhaps with men.

Using a “drug hardness scale” previously described[32], the hardest drug usages reported were IDU (43%), non-injected heroine/cocaine (18%) and crack (15%) (Table 1). Over one-quarter of the sample had traded sex for drugs/money in the last year (including 60% of WSW and 59% of MSM). The prevalence of HIV, HSV-2, Chlamydia and any one of the above three infections was 10%, 49%, 7%, and 58%, respectively. The 10% HIV prevalence reflects the high proportions of IDU and MSM in the sample.

Prevalence of GSE Attendance and Participation

Overall, 36% of the sample attended at least one GSE in the 12 months prior to their interview. Among all participants, substantial minorities had attended a GSE in the last year and participated in sexual partnership (26%) and unsafe sexual partnership (13%) during the most recent GSE attended. Percentages of GSE attendance and sexual activity and unsafe sex during the last GSE were only slightly lower (33%, 22%, and 11%, respectively) among respondents for whom the seed responsible for their being recruited was part of the population-representative youth sample or an IDU, and did not differ by which of these samples the seed was from.

Associations between Individual-level Factors and GSE Attendance and Participation

GSE behaviors were similar across age groups, race/ethnicity, and across serostatus on HIV and HSV-2. Attendance, sex, and unsafe sex at GSEs, however, were significantly higher among hard drug users (including IDUs), MSM, WSW, respondents who had traded sex for money or drugs in the last 3 months, gay GSE subculture recruits, and respondents testing positive for Chlamydia.

Few women other than WSW reported that they had sex at GSE events.

Unsafe sex at a GSE was high among IDUs (82%) and other hard drug users (61%).

Respondent risk behaviors differed by GSE type, with unsafe sex most likely among respondents who last attended a threesome, foursome or larger sex gathering and least likely among respondents who last attended a party with a back room (Table 2).

Table 2.

Sexual Activity among Participants at the last GSE they attended, by the type of GSE they last attended

| N | % of N who had sexa | p-value | N | % of those who had sex who had unsafe sexb | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 167 | 73 | 122 | 49 | ||

| Type Last GSE | ||||||

| • Party with a back room | 76 | 58 | <.0001 | 44 | 34 | .0133 |

| • Threesome, foursome or larger gathering where some or all participants have sex | 65 | 94 | 61 | 62 | ||

| • Other | 26 | 65 | 17 | 41 |

Note: p-values reported from chi-square tests of independence.

Among the 167 who attended a GSE in the past year.

Among the 122 who reported sexual activity at a GSE in the past year.

Characteristics of GSE

GSE characteristics differed by GSE type (see Table 3). The mean number of attendees was greater at parties with a back room (34 persons) and other GSEs (25) than at threesomes, foursomes or larger sex gatherings (10) (p<0.001); the respective median values were 30, 3, and 20. Threesomes, foursomes or larger sex gatherings were relatively intimate groups where most participants engaged in sex; respondents who attended such a GSE reported lower percentages of people they did not know at the event and higher percentages of attendees who engaged in sex, compared with respondents who attended other GSE types. Regardless of GSE type, respondents reported that the majority of attendees at GSEs were high on drugs/alcohol, a minority injected drugs, and the majority engaged in sexual activity: The mean number of sex partners that participants had at the last GSE they attended was 1.5 at parties with a back room, 2.2 at threesomes, foursomes or larger gatherings, and 2.3 at other GSE events. Condoms were available for use at approximately 70% of GSEs.

Table 3.

Characteristics of Last GSE Attended by GSE Type and by Sex

| GSE Type | Sex | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Party with a back room | Threesome, foursome or larger sex gathering | Other | p-value | Male | Female | p-value | |

| Total N | 76 | 65 | 26 | 111 | 56 | ||

| Mean (median) number of sex partners at last GSE | 1.47 (1.00) | 2.18 (2.00) | 2.27 (1.00) | 0.060 | 1.71 (2.00) | 2.20 (2.00) | 0.140 |

| # other people at last GSE | |||||||

| mean (sd) | 34 (25) | 10 (17) | 25 (25) | <.0001 | 24 (24) | 19 (25) | .3038 |

| median (range) | 30 (4–100) | 3 (2–90) | 20 (4–100) | 15 (2–100) | 8 (2–100) | ||

| % attendees you did not know | |||||||

| mean (sd) | 49 (35) | 32 (38) | 52 (35) | .0125 | 41 (36) | 46 (39) | .4555 |

| median (range) | 50 (0–100) | 15 (0–100) | 50 (0–100) | 33 (0–100) | 50 (0–100) | ||

| % other attendees high on drugs/alcohol | |||||||

| mean (sd) | 93 (18) | 88 (29) | 88 (24) | .4014 | 92 (21) | 88 (28) | .2974 |

| median (range) | 100 (0–100) | 100 (0–100) | 100 (15–100) | 100 (0–100) | 100 (0–100) | ||

| % other attendees injecting drugs | |||||||

| mean (sd) | 13 (26) | 14 (38) | 6 (13) | .4542 | 12 (25) | 12 (27) | .9863 |

| median (range) | 0 (0–100) | 0 (0–100) | 0 (0–55) | 0 (0–100) | 0 (0–100) | ||

| % other attendees engaged in sex1 | |||||||

| mean (sd) | 68 (32) | 90 (20) | 73 (28) | <.0001 | 75 (30) | 83 (26) | .1018 |

| median (range) | 82 (8–100) | 100 (10–100) | 82 (7–100) | 90 (7–100) | 100 (10–100) | ||

| % men engaged in sex with men | |||||||

| mean (sd) | 9 (20) | 15 (32) | 17 (35) | .2748 | 17 (32) | 5 (15) | .0040 |

| median (range) | 0 (0–100) | 0 (0–100)) | 0 (0–100) | 0 (0–100) | 0 (0–100) | ||

| % women engaged in sex with women | |||||||

| mean (sd) | 16 (21) | 32 (35) | 10 (15) | .0002 | 21 (30) | 23 (23) | .6427 |

| median (range) | 5 (0–88) | 28 (0–100) | 3 (0–57) | 4 (0–100) | 25 (0–75) | ||

| Condoms available if anyone wanted them | 67 | 78 | 63 | .2112 | 69 | 75 | .3867 |

Note: p-values reported from F-test of mean difference using SAS GLM procedure unless otherwise noted.

Chi-square test of independence

Lower bound computed using whichever is highest, percent others engaged in heterosexual sex or in homosexual sex.

The characteristics of GSEs attended by men and by women were similar with one exception: compared to women, men attended events where a higher proportion of men had sex with men.

The events attended by participants who had ever injected drugs were similar to those attended by never injectors, with two exceptions (data not presented in tables). First, a greater proportion (26%) of attendees at the events attended by ever-injectors injected drugs there than at events attended by never-injectors (2%; p < .0001). In addition, a greater proportion (29%) of women attendees at the events attended by ever-injectors had sex with other women there than at events attended by never-injectors (17%; p .0114).

Twenty-four respondents who attended GSE were either recruited as attendees at gay group sex parties or were recruited by chain-link from them to their partners and beyond. We compared the characteristics of group sex events these 24 participants attended with those attended by the 143 other respondents who attended GSEs (data not presented in tables). They were similar on most variables. However, a greater mean percentage of attendees (88%) had sex at the GSE attended by these 24 respondents than at those attended by the others (76%; p .0075); and a higher percentage of the men at these events engaged in sex with men (48%) than at the events attended by the other 143 (7%; p < .0001).

STIs among GSE Attendees

Sixty-one percent of attendees for whom we have STI data tested positive on at least one of three infections; 11% tested positive for HIV, 51% HSV-2, and 10% Chlamydia (data not shown). Thirty-seven percent of attendees who tested positive on at least one of these three infections and 34% who tested negative on all three infections had unsafe sex at the last event.

STI/HIV Discordance

Among respondents with valid STI results, 12% of 90 dyads were HIV-discordant; 45% HSV-2-discordant, and 21% Chlamydia-discordant). Too few dyads reported having sex with each other at a given GSE to confidently calculate discordancy among sex partners at a GSE.

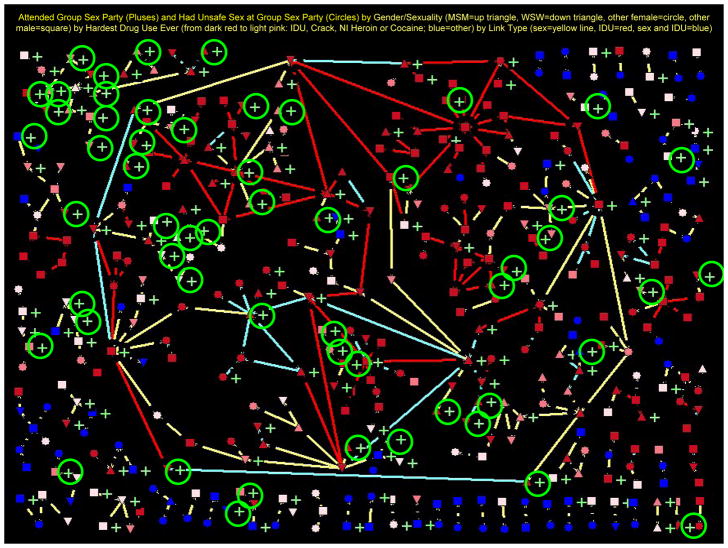

Attendance and unsafe sex at group sex events in the sociometric risk network

Figure 1 graphically displays the locations of respondents who attended GSEs in the sociometric risk network. Participants who engaged in unsafe sex at their last GSE event are circled. The large connected component in the center of the figure contains a large number of people who attended such events. Many of the component members who did not attend a GSE reported having had sex with someone who did have sex at such an event, and almost all members of this large component are within a network distance (geodesic distance) of two of someone who attended. By way of contrast, many of the smaller components have few or no members who attended a group sex event. The clear exceptions are the components in the upper left of Figure 1, which consist of respondents recruited for their linkages with the gay sex party scene. Unsafe sex at a GSE is reported relatively rarely, although it is reported by a majority of these same upper-left components and also by a cluster of similarly-recruited members who appear towards the left side of the large component.

Figure 1.

DISCUSSION

Over one-third of respondents in this high-risk sample had attended a group sex event in the past 12 months; even among those who were not recruited as part of the gay group sex subculture sample, 33% had attended a GSE in the last year.

GSEs are high-risk environments. There is widespread use of drugs and alcohol at these events, and both sex and unprotected sex are common. Although GSEs vary widely in their number of attendees, many involve ten or more people having sex at the event. Since respondents averaged more than one sex partner at the last event they attended, this suggests that STI transmission to multiple partners at once is possible. Since many respondents reported they did not know many attendees at the GSE they last attended, this suggests the possibility that GSEs may lead to transmission across the boundaries of friendship networks. Thus, GSEs may play an important role in STI/HIV transmission among this high-risk community. These findings point to a need for further research on GSEs among other populations and in population-representative samples. Zule et al similarly found that 46% of 41 participants in his ethnographic study of drug users, MSM, and others “knowledgeable about drug use and/or male-to-male sexual activity” in a rural North Carolina county had engaged in group sex.[13]

As was the case in research on gay sex venues, risky sexual practices differed by GSE type[4–6]. Threesomes, foursomes or larger sex gatherings are reported to have the fewest attendees and unknown others and to have the highest percent of attendees reporting condom use– which may give the appearance that this type of gathering is relatively safe. However, this safety is limited: the mean proportion of attendees at these relatively small GSEs who actually have sex is very high (94%), and, within each risk group, participants who attend this kind of event are thus most likely to have unprotected sex despite using condoms for a higher proportion of sex acts if they have sex (data not shown).

The data demonstrate STI-discordancy among GSE attendees. Substantial percentages of both positive and negative attendees engage in sex and in unprotected sex. As such, there is a serious risk of HIV and other STI transmission at these events.

The potential risk of GSE-induced transmission of HIV or other STIs is not limited to gay men. Diverse groups, including MSM, WSW, other men, a limited number of other women, drug users and non-drug users, attend GSE, sometimes the same event, and engage in unprotected sex at these events.

As shown in Figure 1, sociometric sexual networks afford considerable opportunity for onward transmission of infections acquired at GSEs. The high proportion of GSE attendees in the large connected component suggests considerable vulnerability to epidemic outbreaks within such networks.

A number of limitations should be noted. First, this sample is a high-risk sample, hence we were unable to measure the prevalence and frequency of GSEs or describe characteristics of GSE attendees among the general population, preventing an assessment of the population-level importance of GSEs to STI/HIV-transmission. As is usual in network studies of this type, only a minority of named contacts were reached. In addition, behavioral data are based on respondent recall, not observation, and thus group sex and other behaviors may have been under-reported.

As discussed before, GSE are risk situations that bring together heightened levels of behavioral and biomedical HIV risk. At these events, concurrency maximizes behavioral risk, with a possibility that recently-acquired HIV infection together with infection by other STIs will amplify biomedical risk. Although population prevalence of GSE is still unknown, the high potential risk and frequency of GSE events in this sample in both non-MSM and MSM participants are worrisome. Researchers should incorporate questions about group sex attendance and sexual behaviors into general sexual behavior surveys and, more generally, in epidemiologic and prevention research. Participants in existing interventions should have the risks of group sex events pointed out to them, and should be counseled both in terms of avoiding attendance, safety if they should attend, and protecting partners. Interventions should be developed to reduce STI and HIV among attendees at GSEs. Given the lack of experience and research on such interventions, particularly in non-MSM populations, this may require substantial social research.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the NIDA grant Networks, Norms and HIV/STI Risk Among Youth (Samuel Friedman, PI, R01DA013128) and by the postdoctoral Behavioral Sciences Training in Drug Abuse Research program, sponsored by Public Health Solutions and the National Development and Research Institutes, Inc. with funding from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (5T32 DA07233). The authors would like to acknowledge the assistance of the participants in this study.

Reference List

- 1.McKusick L, Horstman W, Coates TJ. AIDS and sexual behavior reported by gay men in San Francisco. Am J Public Health. 1985;75:493–6. doi: 10.2105/ajph.75.5.493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Clatts MC, Goldsamt LA, Yi H. An emerging HIV risk environment: a preliminary epidemiological profile of an MSM POZ Party in New York City. Sex Transm Infect. 2005;81:373–6. doi: 10.1136/sti.2005.014894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Frankis J, Flowers P. Men who have sex with men (MSM) in public sex environments (Pses): a systematic review of quantitative literature. AIDS Care. 2005;17:273–88. doi: 10.1080/09540120412331299799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Binson D, Woods WJ, Pollack L, Paul J, Stall R, Catania JA. Differential HIV risk in bathhouses and public cruising areas. Am J Public Health. 2001;91:1482–6. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.9.1482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.de Wit JB, de Vroome EM, Sandfort TG, van Griensven GJ. Homosexual encounters in different venues. Int J STD AIDS. 1997;8:130–4. doi: 10.1258/0956462971919552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Parsons JT, Halkitis PN. Sexual and drug-using practices of HIV-positive men who frequent public and commercial sex environments. AIDS Care. 2002;14:815–26. doi: 10.1080/0954012021000031886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dietrich LC. Chicana adolescents: Bitches, ‘ho’s, and schoolgirls. Westport, CT: Praeger; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Freudenberg N, Roberts L, Richie BE, Taylor RT, McGillicuddy K, Greene MB. Coming up in the Boogie Down: Lives of adolescents in the South Bronx. Health Education and Behavior. 1999;26(6):788–805. doi: 10.1177/109019819902600604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Krauss B, O’Day J, Godfrey C, Rente K, Freidin L, Bratt E, Minian N, Knibb K, Welch C, Kaplan R, Saxena G, McGinniss S, Gilroy J, Nwakeze P, Curtain S. Who wins in the status games? Violence, sexual violence and an emerging single standard among adolescent women. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2006 Nov;1087:56–73. doi: 10.1196/annals.1385.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rothenberg RB, Sterk C, Toomey KE, Potterat JJ, Johnson D, Schrader M, et al. Using social network and ethnographic tools to evaluate syphilis transmission. Sex Transm Dis. 1998;25:154–60. doi: 10.1097/00007435-199803000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nilsson U, Hellberg D, Shoubnikova M, Nilsson S, Mardh PA. Sexual behavior risk factors associated with bacterial vaginosis and Chlamydia trachomatis infection. Sex Transm Dis. 1997;24:241–6. doi: 10.1097/00007435-199705000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Elshibly S, Kallings I, Hellberg D, Mardh PA. Sexual risk behaviour in women carriers of Mycoplasma hominis. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1996;103:1124–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1996.tb09595.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zule WA, Costenbader E, Coomes CM, Meyer WJ, Jr, Riehman K, Poehlman J, Wechsberg WM. Stimulant Use and Sexual Risk Behaviors for HIV in Rural North Carolina. J Rural Health. 2007;23 (Supplement):73–78. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-0361.2007.00127.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pilcher CD, Chuan Tien H, Eron JJ, Jr, Vernazza PL, Leu S-Y, Stewart PW, Goh L-E, Cohen MS for the Quest Study and the Duke-UNC-Emory Acute HIV Consortium. Brief but Efficient: Acute HIV Infection and the Sexual Transmission of HIV. The Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2004;189(10):1785–1792. doi: 10.1086/386333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jacquez JA, Koopman JS, Simon CP, Longini IM., Jr Role of the primary infection in epidemics of HIV infection in gay cohorts. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 1994;7:1169–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Koopman JS, Jacquez JA, Welch GW, Simon CP, Foxman B, Pollock SM, et al. The role of early HIV infection in the spread of HIV through populations. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr Hum Retrovirol. 1997;14:249–58. doi: 10.1097/00042560-199703010-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wawer MJ, Gray RH, Sewankambo NK, Serwadda D, Li X, Laeyendecker O, et al. Rates of HIV-1 transmission per coital act, by stage of HIV-1 infection, in Rakai, Uganda. J Infect Dis. 2005;191:1403–9. doi: 10.1086/429411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Friedman S, Jose B, Neaigus A, Curtis R, Vermund S, Des Jarlais D. Network-related mechanisms may help explain long-term HIV-1-seroprevalence levels that remain high but do not approach population-group saturation. Am J Epidemiol. 2000;152:913–922. doi: 10.1093/aje/152.10.913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fleming DT, Wasserheit JN. From epidemiological synergy to public health policy and practice: the contribution of other sexually transmitted diseases to sexual transmission of HIV infection. Sex Transm Infect. 1999;75:3–17. doi: 10.1136/sti.75.1.3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pilcher CD, Price MA, Hoffman IF, Galvin S, Martinson FE, Kazembe PN, et al. Frequent detection of acute primary HIV infection in men in Malawi. AIDS. 2004;18:517–24. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200402200-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Celum CL, Robinson NJ, Cohen MS. Potential effect of HIV type 1 antiretroviral and herpes simplex virus type 2 antiviral therapy on transmission and acquisition of HIV type 1 infection. J Infect Dis. 2005;191 (Suppl 1):S107–14. doi: 10.1086/425272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Freeman EE, Weiss HA, Glynn JR, Cross PL, Whitworth JA, Hayes RJ. Herpes simplex virus 2 infection increases HIV acquisition in men and women: systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. AIDS. 2006;20:73–83. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000198081.09337.a7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wald A, Link K. Risk of human immunodeficiency virus infection in herpes simplex virus type 2-seropositive persons: a meta-analysis. J Infect Dis. 2002;185:45–52. doi: 10.1086/338231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hudson CP. Concurrent partnerships could cause AIDS epidemics. Int J STD AIDS. 1993;4:249–53. doi: 10.1177/095646249300400501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kraut-Becher JR, Aral SO. Gap length: an important factor in sexually transmitted disease transmission. Sex Transm Dis. 2003;30:221–5. doi: 10.1097/00007435-200303000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Manhart LE, Aral SO, Holmes KK, Foxman B. Sex partner concurrency: measurement, prevalence, and correlates among urban 18–39-year-olds. Sex Transm Dis. 2002;29:133–43. doi: 10.1097/00007435-200203000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Morris M, Kretzschmar M. Concurrent partnerships and transmission dynamics in networks. Soc Net. 1995;17:299–318. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Morris M, Kretzschmar M. Concurrent partnerships and the spread of HIV. AIDS. 1997;11:641–8. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199705000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rosenberg M, Gurvey J, Adler N, Dunlop M, Ellen J. Concurrent sex partners and risk for sexually transmitted diseases among adolescents. Sex Transm Dis. 1999;26:208–212. doi: 10.1097/00007435-199904000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Watts CH, May RM. The influence of concurrent partnerships on the dynamics of HIV/AIDS. Math Biosci. 1992;108:89–104. doi: 10.1016/0025-5564(92)90006-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Friedman SR, Bolyard M, Mateu-Gelabert P, Goltzman P, Pawlowicz MP, Singh DZ, et al. Some data-driven reflections on priorities in AIDS network research. AIDS Behav. 2007;11:641–51. doi: 10.1007/s10461-006-9166-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Flom P, Friedman S, Jose B, Curtis R, Sandoval M. Peer norms regarding drug use and drug selling among household youth in a low income “drug supermarket” urban neighborhood. Drugs Educ Prev Pol. 2001;8:219–232. [Google Scholar]