Abstract

Fragile X associated tremor/ataxia syndrome (FXTAS) is a neurodegenerative disorder that is the result of a CGG trinucleotide repeat expansion in the range of 55-200 in the 5’ UTR of the FMR1 gene. To better understand the progression of this disorder, a knock-in (CGG KI) mouse was developed by substituting the mouse CGG8 trinucleotide repeat with an expanded CGG98 repeat from human origin. It has been shown that this mouse shows deficits on the water maze at 52 weeks of age. In the present study, this CGG KI mouse model of FXTAS was tested on behavioral tasks that emphasize spatial information processing. The results demonstrate that at 12 and 24 weeks of age, CGG KI mice were unable to detect a change in the distance between two objects (metric task), but showed intact detection of a transposition of the objects (topological task). At 48 weeks of age, CGG KI mice were unable to detect either change in object location. These data indicate that hippocampal-dependent impairments in spatial processing may occur prior to parietal cortex-dependent impairments in FXTAS.

Keywords: Fragile X Premutation, Spatial Processing, Spatial Pattern Separation, Metric, Topological

Introduction

Fragile X associated tremor/ataxia (FXTAS) is a progressive neurodegenerative disorder with intention tremor and ataxia (Hagerman & Hagerman, 2004). Neuropathology include white matter disease, white matter hyperintensities in the middle cerebellar peduncle on T2 weighted MRI images, subtle brain atrophy, and the presence of intranuclear inclusions in neurons and astrocytes throughout the brain, with a high percentage being located in the hippocampus (Greco, et al., 2002, 2006; Tassone, et al, 2004). The cognitive sequelae of the fragile X premutation that underlie FXTAS include deficits for working memory, executive processing, and reduced hippocampal activation during episodic retrieval tasks (Cornish, et al., 2007; Koldewyn, et al., 2008; Sevin, et al, in press).

Both fragile X syndrome (FXS) and fragile X-associated tremor/ataxia (FXTAS) are the result of a tandem CGG trinucleotide repeat in the 5’ untranslated region (UTR) of the FMR1 gene. In unaffected individuals there are between 5-40 CGG repeats, in FXTAS there are between 55-200 CGG repeats, and in full FXS there are >200 CGG repeats (40-55 is defined as a grey zone between unaffected and premutation status). The mutation affecting individuals with FXS results in gene hyper-methylation, almost complete gene silencing (lack of FMR1 transcription); and an absence of the FMR1 gene product, FMRP (fragile X mental retardation protein). In contrast, the CGG repeat expansion underlying FXTAS results in increased FMR1 transcription, elevated FMR1 mRNA but, paradoxically, slightly decreased levels of FMRP (Brouwer et al., 2008a,c; Hagerman & Hagerman, 2004; Oostra & Willemsen, 2009). Because the mutation affecting FXTAS carriers was once thought to be without a phenotype it is commonly referred to as a premutation, in comparison with the FMR1 full mutation which results in FXS (Brouwer, et al., 2008c; Hagerman & Hagerman, 2004).

A knock-in (KI) mouse model of the fragile X premutation has been generated in which the mouse endogenous CGG8 trinucleotide repeat was replaced via homologous recombination with a human CGG98 trinucleotide repeat (Bontekoe, et al., 1997; Brouwer, et al., 2008a,b; Willemsen, et al., 2003). Similar to the human cases of FXTAS, the brains of these CGG KI mice show intranuclear inclusions that stain for ubiquitin in a number of brain regions, including the dentate gyrus in the hippocampus (Brouwer et al., 2008a; Willemsen, et al., 2003). Further, it has been reported that at 52 weeks of age these CGG KI mice have a deficit on the hidden platform version of the water maze, as well as motor deficits on the rotarod at 70 weeks of age (Van Dam, et al., 2005).

Humans with the fragile X premutation underlying FXTAS have intranuclear inclusions in neurons in the hippocampus and neocortex. In humans, it is still unknown at what age inclusions form due to the nature of the disorder and the advanced age at which FXTAS is diagnosed, but it has been shown that inclusions can form after as few as eight days in vitro after an expanded CGG repeat with an eGFP reporter is introduced into primary neural progenitor cells and established cell lines (Arocena, et al., 2005). In CGG KI mice, inclusions are common at 50-100 weeks of age, but their presence has been reported in the literature as early as 20 weeks of age (Brouwer, et al., 2008a,b; Willemsen, et al., 2003). It is not yet known if the inclusions contribute directly to the neuropathology seen in FXTAS. It has been suggested that intranuclear inclusions may not be pathological of themselves, but may reflect pathology such as mRNA toxicity due to the increased gene transcription resulting from the premutation or perhaps due to the presence of the mutant mRNA itself (Brouwer, et al., 2008a,c; Hagerman & Hagerman, 2004; Willemsen, et al., 2003).

It has recently been proposed for a number of neurodevelopmental disorders that decreased resolution or sensitivity of spatial and temporal processing, referred to as “hypergranularity”, may contribute to cognitive deficits (Simon, 2008). This hypergranularity or poor resolution in the processing of spatial and temporal information leads to inefficient sensory integration and cognitive function. Since individuals with FXTAS show generalized brain atrophy, white matter disease, as well as intranuclear inclusions that may contribute to altered neural function, it follows that hypergranular spatial and temporal information processing may underlie a subset of the cognitive deficits seen in individuals with FXTAS. Furthermore, although FXTAS is currently characterized as a neurodegenerative disorder, the fragile X premutation is already present in utero, so there is reason to believe that there may be some cognitive and/or behavioral deficits early in life, suggesting that one can also view FXTAS, or at least the fragile X premutation, as a neurodevelopmental disorder (Cornish, et al., 2007; Hagerman & Hagerman, 2004). There are also recent reports of relatively early cognitive phenotypes in individuals with the fragile X premutation (Farzin, et al., 2006; Goodin-Jones, et al., 2004; Hagerman, 2006; Hessl, et al., 2005).

Additionally, it has been reported that the hippocampus of individuals with the fragile X premutation (without concomitant FXTAS) have slightly reduced hippocampal volumes relative to age and IQ matched controls, and that this volume reduction correlates strongly with impaired performance on standardized tests of memory (Jakala, et al., 1997; cf Sevin, et al., in press). Koldewyn et al. (2008) further demonstrated that asymptomatic carriers of the fragile X premutation show decreased hippocampal activation during an episodic retrieval task, a task dependent upon hippocampal function. These results suggest that reductions in hippocampal volume in tandem with functional abnormalities in the hippocampus may contribute to the neuropsychiatric symptoms and cognitive decline seen in FXTAS. What remains unknown is whether normal posterior parietal cortex functions are intact in carriers of the fragile X premutation, both with and without FXTAS symptomology. What is known is that in FXTAS there is cortical atrophy and white matter disease throughout the subcortical white matter (Brunberg, et al., 2002; Greco, et al., 2006).

The rodent hippocampus has been shown to subserve a process called spatial pattern separation (Gilbert, Kesner, & Lee, 2001; Goodrich-Hunsaker, Hunsaker, & Kesner, 2005, 2008b; Hunsaker, Rosenberg, & Kesner, 2008; Kesner, Gilbert, & Wallenstein, 2000; Kesner, Lee, & Gilbert, 2003; Rolls & Kesner, 2006). Spatial pattern separation can be described as the ability to discriminate between very small changes in the spatial relationships between stimuli. As such, spatial pattern separation is the mechanism underlying the precision of spatial resolution required to form fine spatial memory. This concept of pattern separation as an important cognitive function has also been formalized into a computational model in rodents and primates by Rolls and Kesner (2006) among many others (cf. Marr, 1971; McNaughton & Morris, 1987).

It has further been proposed that one form of spatial pattern separation called “metric spatial processing” is involved in determining the precise angles and exact distances that separate objects in the environment, without regard to the identity of the objects (Gallistel, 1993; Goodrich-Hunsaker, et al., 2005, 2008b). This form of spatial processing has been localized in rodents to a neural network involving the dentate gyrus. In this sense, objects in a configuration can be transposed and maintain their metric structure, so long as the same spatial locations remain occupied by objects.

In “topological spatial processing”, which is functionally separate from metric processing, it is the overall configuration of the objects and their general relationships to each other that is important, with the precise angles and distances between objects of less importance (Goodrich-Hunsaker, et al., 2005, 2008a,b). In this sense, for topological processing the location of each object relative to the others is critical (i.e. in front of, to the left of, between, etc), but the precision of the relationship is less so (e.g. it does not matter if the objects are 10 cm apart, 20 cm, or greater, as long as the general relationship between the objects remains the same). This means that all objects in a configuration could be moved further apart or closer together, so long as the configuration of the objects remains otherwise unaltered (i.e. the configuration of objects remain the same, while distances between objects may change). Topological processing has been localized to a neural network involving the parietal cortex (Goodrich-Hunsaker, et al., 2005).

Kesner and colleagues (Goodrich-Hunsaker, et al., 2005, 2008b; Hunsaker, et al., 2008) have developed two behavioral tasks to test the contributions of the hippocampus and the parietal cortex for metric and topological spatial information processing, respectively. In the original Goodrich-Hunsaker et al. (2005) study, rats with lesions restricted to either the dorsal hippocampus or parietal cortex were presented with objects on an open field and allowed to explore. After exploration, the relationships between these objects were changed, either being moved closer together or further apart (metric changes), or by transposing the objects (topological changes). Animals with parietal lesions were unable to detect the transposition, but were capable of noticing and exploring the objects after they had been moved closer together or further apart. Animals with hippocampal ablations were unable to detect the change in the distance between the objects after, but were capable of detecting transposition of the objects. These lesion studies in rats suggest that the hippocampus subserves metric spatial processing and that the parietal cortex subserves topological spatial processing (i.e., a double dissociation was demonstrated; Goodrich-Hunsaker, et al., 2005). These findings were further expanded in subsequent lesion studies to implicate the dentate gyrus, and not CA3 or CA1, in metric processing (Goodrich-Hunsaker, et al., 2008b). The topological task has also been used to identify alterations to parietal cortex function in transgenic mouse models (cf. Lee et al., 2009).

To directly test the whether the CGG KI mice show spatial deficits in the metric or topological tasks, or both, and at what developmental age, CGG KI mice and wildtype littermates were evaluated on tests emphasizing either metric or topological spatial processing at one of three ages: 12, 24 or 48 weeks of age. As previous work with this CGG KI mouse has shown deficits during the water maze, it is proposed that tests of metric and topological spatial information processing may provide a sensitive tool to help identify subtle cognitive processing deficits in CGG KI mice that may be missed by other learning and memory tasks (cf. Lee, et al., 2009), and may better reflect similar spatial processing deficits in humans with FXTAS.

Materials and Methods

Animals

The generation of an expanded CGG trinucleotide repeat knock-in (CGG KI) mouse model of the fragile X premutation has been described previously (Bontekoe, et al., 1997; Willemsen, et al., 2003). Briefly, the endogenous CGG8 trinucleotide repeat in the 5’ UTR of the mouse Fmr1 gene was replaced by a human CGG98 trinucleotide repeat via homologous recombination. Across breedings, the CGG repeats was mildly unstable, both expanding and contracting in length within the fragile X premutation range defined as ~55-200 CGG repeat (Brouwer, et al., 2009; Willemsen, et al., 2003).

The CGG KI mice were originally on a on a mixed FVB/N × C57BL/6J background, and were backcrossed with C57BL/6J mice from Jackson Labs (Bar Harbor, ME) until greater than 98% C57BL/6J by microsatellite analysis. Only male mice were used in the present study.

The CGG KI mice used in the present study had between CGG80 and CGG180 repeats. Animals were housed in same sex, mixed genotype groups of up to four littermates per cage with food and water ad libitum, under conditions of constant temperature and a 12 / 12 h light-dark cycle. Behavioral testing was always conducted during the light portion of the light cycle (between 0900-1500 pacific standard time). A previous study (Van Dam, et al., 2005) studied spatial memory on the water maze with the CGG KI mice on the mixed FVB/N × C57BL/6J background. To evaluate spatial memory in the present study, CGG KI mice on a congenic C57BL/6J background were used. At 12 weeks of age, 8 male wildtype mice 8 male CGG KI mice were used for behavioral experimentation. At 24 weeks of age, 8 different male wildtype animals and 10 different male CGG KI mice were used for behavioral experimentation. At 48 weeks of age, 10 different male wildtype and 8 different male premutation mice were used for behavioral experimentation. All wildtype mice were littermates with at least one CGG KI mouse used in the present study. For this initial investigation of metric and topological spatial processing in the CGG KI mouse, mice were not retested on any experiments to avoid any complications with repeated testing. All experimental protocols conformed to University of California, Davis IACUC protocols.

Genotyping

DNA was extracted from mouse tails by incubating with 10mg/ml Proteinase K (Roche Diagnostics) in 300μl lysis buffer containing 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 10 mM EDTA, 150 mM NaCl, 1% SDS overnight at 55°C. One hundred μl saturated NaCl was then added and the suspension was centrifuged. One volume of 100% ethanol was added, gently mixed, and the DNA was pelleted by centrifugation and the supernatant discarded. The DNA was washed and centrifuged in 500 μl 70% ethanol. The DNA was then dissolved in 100μl milliQ-H20. CGG repeat lengths were determined by PCR using the Expanded High Fidelity Plus PCR System (Roche Diagnostics). Briefly, approximately 500-700 ng of DNA was added to 50 μl of PCR mixture containing 2.0 μM of each primer, 250 μM of each dNTP (Invitrogen), 2% DMSO (Sigma), 2.5 M Betaine (Sigma), 5 U Expand HF buffer with Mg (7.5 μM). The forward primer was 5’-GCTCAGCTCCGTTTCGGTTTCACTTCCGGT-3’ and the reverse primer was 5’-AGCCCCGCACTTCCACCACCAGCTCCTCCA-3’. PCR steps were 10 min denaturation at 95°C, followed by 34 cycles of 1 min denaturation at 95°C, annealing for 1 min at 65°C, and elongation for 5 min at 75°C to end each cycle. PCR ends with a final elongation step of 10 min at 75°C. DNA CGG band sizes were determined by running DNA samples on a 2.5% agarose gel and staining DNA with ethidium bromide.

Behavioral Apparatus

For the metric and topological spatial processing tasks, a circular table measuring 1 m in diameter was covered with a clean, white, plastic cover. Four objects measuring between 2.5-5 cm at the base and between 5 and 15 cm tall were used as stimuli in these tasks (a small bottle filled with green liquid, an overturned coffee mug, a large pipette bulb, and an unused spray paint can). These objects were chosen to be texturally and visually unique and easily distinguishable for the mice. The table was surrounded on two sides by walls (at a distance of ~1 m) with discrete distal cues available at the same level as the table surface affixed to the walls. Between the habituation and test sessions, the mice were placed in a small, opaque holding cup with a single paper towel placed inside. The circular table was wiped down with 70% ethanol after testing of each mouse to remove olfactory cues that could influence object exploration by later tested mice. These spatial processing tasks were developed for use in rats, but have been modified for use with transgenic mice. The topological spatial processing task has been used in transgenic mice in an earlier study (Lee et al., 2009), but to our knowledge this is the first time the metric task has been used in mice.

Behavioral Methods

Metric Spatial Processing Task

The arrangement of objects for the metric spatial processing tasks is shown in Figure 1 (Goodrich-Hunsaker, et al., 2005, 2008b). The mouse was placed on the maze as shown in Figure 1 facing two objects placed 45 cm apart (the animal was placed ~ 30-40 cm from the objects). The mouse was allowed 15 min to freely explore the tabletop, stimulus objects on the table, and distal environmental cues. Exploration of the objects decreases over the 15 min period as animals habituate. After the 15 min habituation session, the mouse was removed to the small holding cup for 5 min. During this intersession interval the objects were moved 15 cm closer to each other so that the objects were 30 cm apart. The mouse was then again placed on the tabletop as described above and given 5 min to re-explore the objects during this test session.

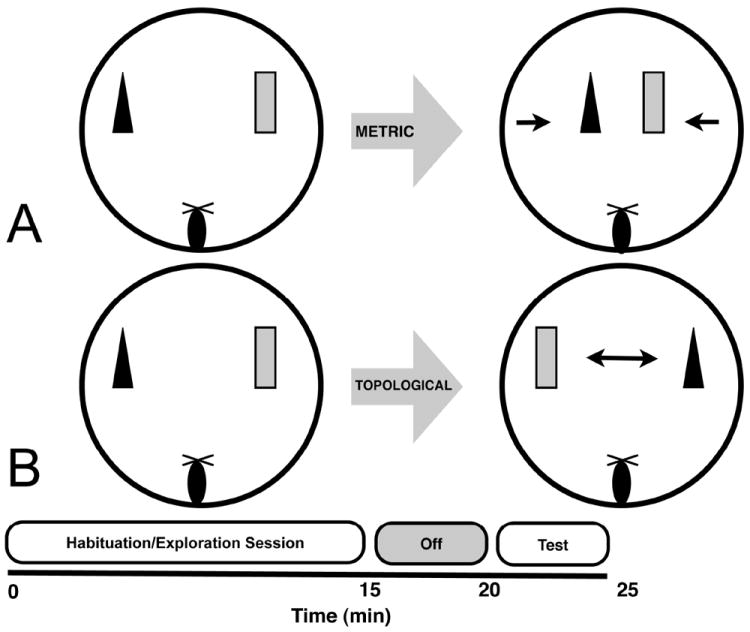

Figure 1.

A. Diagram and timeline for the metric spatial processing task. B. Diagram and timeline for the topological spatial processing task. Notice that the habituation sessions are identical between the tasks, with only the object manipulation differing between the habituation and test sessions.

Topological Spatial Processing Task

For the topological spatial processing task (Figure 1; paradigm slightly modified from Goodrich-Hunsaker, et al., 2005, 2008b; Lee, et al., 2009), two novel objects, different from those used in the metric task, were used as stimuli. Mice were placed on the table and allowed to habituate to the objects exactly as in the metric task, and then removed from the table for 5 min. During the 5 min between the habituation and test sessions, the objects were transposed, so the left object was now on the right and vice versa. Therefore, objects occupied the same spatial locations as during the habituation session, but their positions were exchanged.

The order of the metric and topological spatial processing tasks was randomized so that half of the wildtype and half the CGG KI mice received each task first. The object pairs presented during each task were randomized between mice.

Dependent Measures

For both the metric and topological tasks, the time spent exploring each object was recorded as the dependent variable. This exploratory activity was recorded in 0.5 sec increments (i.e. a 0.25 sec bout of exploration was recorded as 0.5 sec and a 0.75 sec bout of exploration was recorded as 1 sec). Exploration was defined as the mouse actively sniffing or touching the object with its nose, vibrissa or forepaws. An animal simply located near the objects without actively interacting with them was not scored as exploration. Object exploration data were summarized in 5 min epochs during the 15 min habituation period to facilitate comparison with the 5 min test session, as previously described (Goodrich-Hunsaker, et al., 2005, 2008b; Hunsaker, et al., 2008). Mice habituate to the objects during the 15 min habituation phase, and show relatively low levels of exploration during the last 5 min. However, during the 5 min test session when mice are put back on the table, mice that remember the object distance (metric) or object position (topological) show increased exploration.

Immunocytochemistry for Intranuclear Inclusions

Immunocytochemistry was carried out on subsets of wildtype and CGG KI mice at 12, 24 and 48 weeks of age to document the presence of characteristic intranuclear inclusion in CGG KI mice and absence of such inclusions in wildtype mice. Two animals per age per genotype (n=2 wildtype, n=2 CGG KI at 12 weeks; n=2 wildtype, n=2 CGG KI at 24 weeks; n=2 wildtype, n=2 CGG KI at 48 weeks) that were not used in behavioral experiments were deeply anesthetized with sodium pentobarbital and, once unresponsive, intracardially perfused with 10 mL lightly chilled Ringer’s solution with heparin followed by 60 mL of lightly chilled, fresh 4% (w/v) paraformaldehyde (PFA) in 0.1 M phosphate buffer (PB) at pH 7.4 over 20 min (3 ml/min via gravity flow). The brain was removed and placed into 4% PFA for 1 hr postfixation at 4°C, rinsed and transferred into 10% (w/v) sucrose in 0.1 M PB, pH 7.4 for 1 hr at 4°C, and then transferred into 30% (w/v) sucrose for 24 hr at 4°C for cryoprotection. The brains were then frozen on dry ice for 60 min prior to storage at -80°C.

The left hemisphere was sectioned in the parasaggital plane on a freezing stage microtome at 30 μm and sections were collected into series of every fifth section directly into 30% sucrose (i.e. 5 section sets). One set of sections was immediately mounted onto 1% gelatin coated slides from PB and set aside for hematoxylin and eosin staining for evaluation of overall structural morphology and the presence of intranuclear inclusions, a characteristic feature of CGG KI mice and FXTAS individuals (Greco, et al., 2002, 2006; Willemsen et al., 2003). The other four sets of sections in sucrose as well as the right hemisphere were flash frozen on dry ice and stored at -80°C.

For immunocytochemistry for ubiquitin to visualize intranuclear inclusions, free-floating sections from one of the remaining four sets of frozen sections were rinsed of 30% sucrose with 10% sucrose followed by 0.1 M PB (pH 7.4). After treatment with 0.1% (w/v) sodium borohydride (10 min), sections had endogenous peroxidases quenched with hydrogen peroxide (0.5% and 2%). After transfer from 0.1 M PB to a 0.1 M PB saline solution (PBS, pH 7.4), tissue was blocked and permeabilized with a solution of 3% (w/v) bovine serum albumin (BSA), 3% (v/v) swine serum, and 0.3% (v/v) triton-X for 1 hr at room temperature with agitation. Rabbit polyclonal antibodies against ubiquitin (Dako, Inc.; Carpinteria, CA) were diluted 1:2000 in 1% swine serum, 2% BSA, and 0.3% triton-X. Sections were placed into the primary antibody solution for 72 hrs on a shaker at 4°C. After primary antibody incubation and rinsing, a biotinylated swine anti-rabbit immunoglobulin secondary antibody (Dako), diluted 1:500 in the same diluent as the primary antibody was incubated with the tissue for 24 hours on a shaker at 4°C. After thorough rinsing, the tissue was incubated in an avidin-biotin complex (ABC; Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) for 24 hr. The ubiquitin immunostaining was visualized using 0.05% diaminobenzidine with a blue/grey chromogen (Vector SG) in PBS. After mounting, the tissue was dehydrated, cleared, counterstained with neutral red, and coverslipped with Permount (Fisher Scientific). Presence of intranuclear inclusions was verified at 1000x magnification on a light microscope.

Statistical Analyses

For the 15 min habituation session, total object exploration time (sec) was calculated individually for the first, middle and last 5 min epochs to facilitate comparison between the last 5 min of the habituation session and the 5 min test session. A 2 (genotype) × 3 (session) repeated measures ANOVA was performed on these exploration data for both metric and topological spatial processing tasks. To facilitate the comparison between the test session and the last 5 min of the habituation session, an exploration ratio was calculated as described by Kesner and colleagues (Goodrich-Hunsaker, et al., 2005). Briefly, the ratio was calculated as: [(exploration time during the 5 min test session) / (exploration time during the 5 min test session + exploration during the last 5 min of the habituation session)]. This constrained all the values between 0 and 1. With this ratio, increased exploration during the 5 min test session compared to the last 5 min of the habituation session is reflected as a ratio >0.5, while decreased exploration (or continued habituation) is reflected as a ratio <0.5. Prior to comparing CGG KI mice and wildtype mice for the ratio scores, it was verified via a one-tailed t test that the ratio score for the wildtype mice was >0.5, suggesting heightened exploration of the objects during the test session compared to the final 5 min of the habituation session. To compare ratios between CGG KI mice and wildtype mice, one way ANOVA with genotype as the grouping variable were performed for both metric and topological tasks. All statistical analyses were performed with the open source statistical package, “R” (Free Software Foundation’s GNU Public License, http://www.r-project.org), and all data are reported as means and standard errors of the mean. All effects were considered statistically significant at p<0.05.

Results

Prior to statistical comparison of the ratio scores between CGG KI and wildtype mice, it was verified that, as expected, the wildtype mice showed heightened exploration of the objects after the metric or topological shifts. To do this, a one-tailed t test was used to assess whether the wildtype control group mean ratio scores were >0.5. In all cases presented below, the wildtype animals showed heightened exploration of the metric or topological changes (p<0.05).

Metric spatial processing task

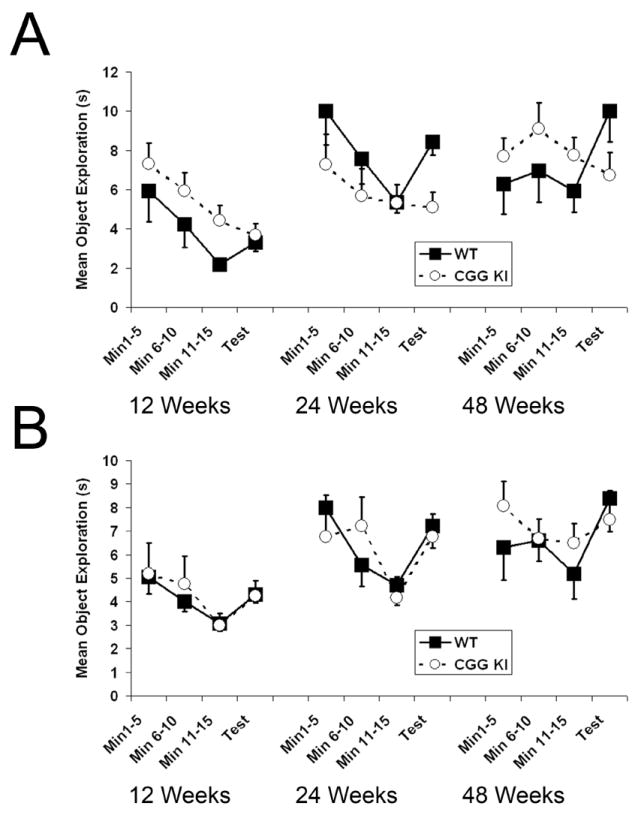

In the metric spatial processing task the distance between the objects was decreased between the habituation and test periods. Performance in the metric task at 12, 24 and 48 weeks of age is shown in Figure 2A. For the 15 min habituation of object exploration, time spent exploring the object (in sec) was analyzed with two way repeated measures ANOVA with genotype as the between group factor and exploration during the three 5 min time blocks as the repeated within group factor. There was no main effect of group at 12 (F1,44 = 3.70, p=0.06), 24 (F1,50 = 1.14, p=0.2) or 48 weeks (F1,50=2.23, p=0.15). As expected, object exploration time decreased significantly over the three time blocks for all groups at each age (p<0.05) reflecting decreased object exploration (i.e., habituation) over the 15 min habituation period. Although it appears that the 48 week old animals showed increased exploration during min 6-10, these animals showed reduced exploration during min 11-15 similar to the other ages. The interaction between the two factors was not statistically significant at 12, 24, or 48 weeks of age. These data indicate that the CGG KI and wildtype mice showed similar habituation of object exploration across the three ages during the initial 15 min habituation period. However, during the 5 min test after reposition of the objects, wildtype mice, but not CGG KI mice, showed an increase in object exploration.

Figure 2. Habituation of Object Exploration.

A. Plots showing habituation of object exploration for the metric spatial processing task. At each age the CGG KI group showed a decrease in exploration during the test compared to the last 5 min of the habituation session, whereas the wildtype group showed a marked increase in exploration during the test. B. Habituation of object exploration for the topological spatial processing task. At 12 weeks and 24 weeks both group showed similar increases in object exploration during the test session. However, at 48 weeks of age the CGG KI group showed similar levels of re-exploration during the test session compared to the last 5 min of the habituation session, while the wildtype group showed a large increase in exploration. The data for MIN 11-15 and the 5 min TEST sessions were used to generate the Mean Ratio Scores reported in figures 3A and 3B.

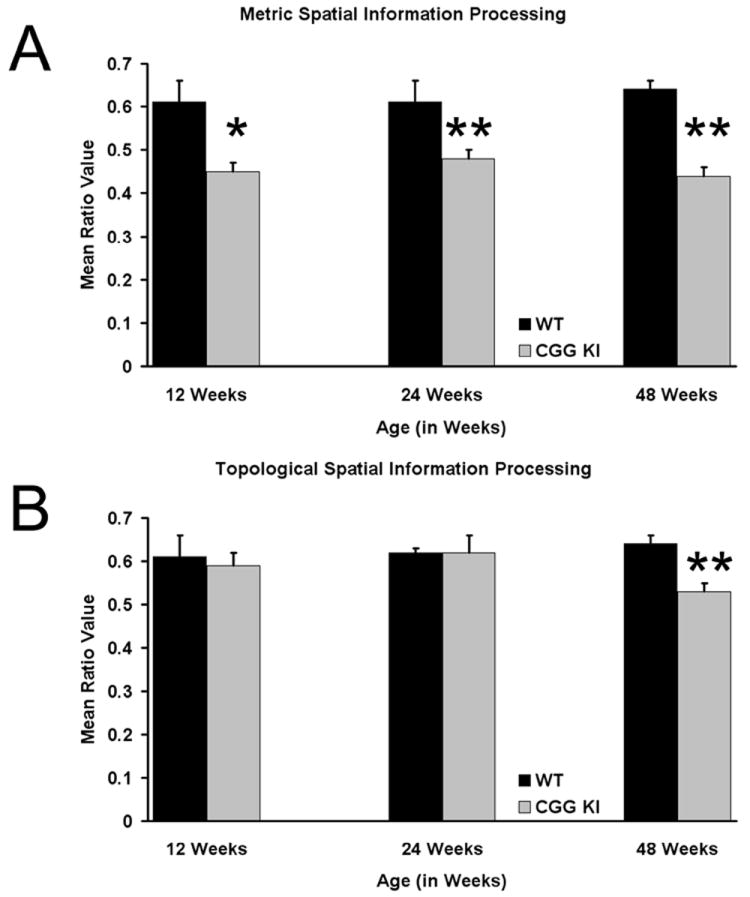

As described in METHODS, changes in object exploration between the 5 min test session and the final 5 min of habituation were expressed as exploration ratio scores and then analyzed by one way ANOVAs with genotype as the grouping factor. As shown in Figure 3A, when the distance between objects was decreased in the metric task, the CGG KI group showed significantly lower mean ratio scores compared to the wildtype group at 12 weeks (F1,14=8.56, p<0.05), 24 weeks (F1,16=8.48, p<0.05) and 48 weeks of age (F1,16=46.31, p<0.01). These results demonstrate that compared to wildtype mice, CGG KI mice did not increase their exploration of the objects after the metric shift at 12 weeks (mean ratio ± SEM = 0.45±0.05 CGG KI vs. 0.61±0.03 wildtype), 24 weeks (mean ratio = 0.48±0.04 CGG KI vs. 0.61±0.01 wildtype) or 48 weeks of age (mean ratio = 0.44±0.02 CGG KI vs. 0.64±0.02 wildtype)

Figure 3. Metric and Topological Spatial Processing.

A. Mean Ratio Scores for wildtype and CGG KI mice at different ages for the metric task B. Mean Ratio Scores for the topological task. (12 weeks of age CGG KI n=8, wildtype=8; 24 weeks of age CGG KI n=10, wildtype=8; 48 weeks of age CGG KI n=8, wildtype=10). * p<0,05, ** p<0.01.

Topological spatial processing task

In the topological spatial processing task the positions of the two novel objects were reversed between the habituation and test periods. Performance in the topological task at 12, 24 and 48 weeks of age is shown in Figure 2B. For the 15 min habituation of object exploration, time spent exploring the object (in sec) was analyzed with two way repeated measures ANOVA with genotype as the between group factor and exploration during the three 5 min time blocks as the repeated within group factor. There was no main effect of group at 12 weeks (F1,44=0.003, p=0.96), 24 weeks (F1,50=0.04 p=0.85) or 48 weeks of age (F1,50=0.1.73, p=0.19). As expected, object exploration time decreased significantly over the three time blocks for all groups at each age (p≤.05) reflecting habituation to the objects over the 15 min habituation period. As in the metric task, wildtype 48 week old mice showed a small increase in exploration during min 6-10, but exploration decreased during the final min 11-15, similar to that seen at the other ages. The interaction between the two factors was not statistically significant at 12, 24, or 48 weeks of age. These data indicate that the CGG KI and wildtype mice showed similar habituation of object exploration across the three ages during the initial 15 min habituation period. After exchanging object location during the 5 min test, wildtype and CGG KI mice showed increased exploration at 12 and 24 weeks of age. However, at 48 weeks of age the CGG KI mice showed little if any reexploration of the objects, while wildtype mice showed marked reexploration compared to the last 5 min of the habituation period.

As was done for the metric task above, changes in object exploration in the topological task were expressed as exploration ratio scores which were then analyzed by one way ANOVAs with genotype as the grouping factor. As shown in Figure 3B, when the positions of the two objects were reversed in the topological task, the CGG KI group did not differ significantly from wildtype mice in exploration of the objects at 12 weeks (F1,14 = 0.09, p=0.78; mean ratio 0.61±0.05 CGG KI vs. 0.59±0.02 wildtype) or 24 weeks of age (F1,16=0.005, p=0.95; mean ratio 0.62±0.05 CGG KI vs. 0.62±0.02 wildtype). However, the object exploration ratio at 48 weeks of age did differ significantly between CGG KI and wildtype mice (F1,16 = 19.40, p<0.01; mean ratio 0.53±0.02 CGG KI vs. 0.64±0.02 wildtype). These data demonstrate an age-dependent impairment in processing of topological spatial information in CGG KI mice compared to wildtype mice, with an impairment observed at 48, but not 12 and 24 weeks of age.

Histology

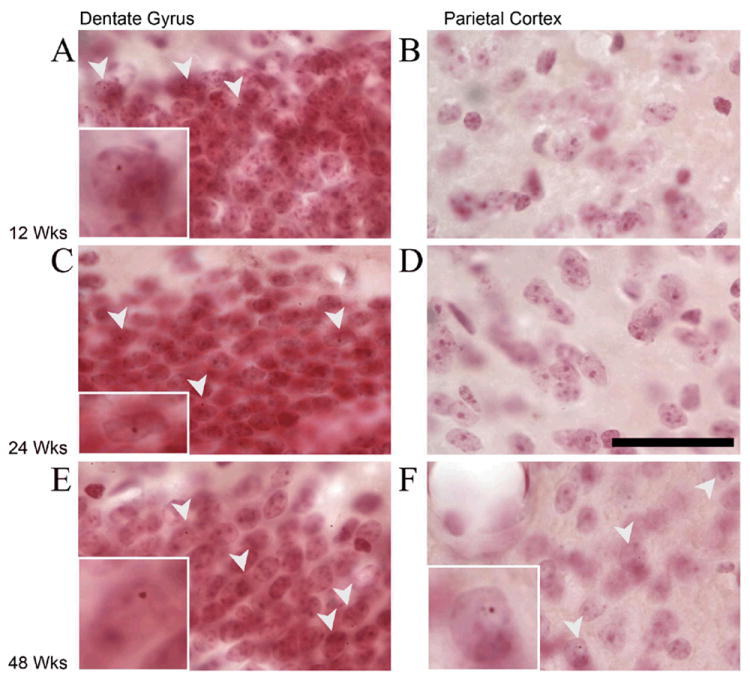

Intranuclear inclusions in the dentate gyrus of the hippocampus and in the overlying parietal cortex were identified by immunocytochemistry for ubiquitin, with neutral red counterstaining (Figure 4). The inclusions appear as dark grey/black round/spherical bodies clearly within the nucleus of neurons. These intranuclear inclusions are easily differentiated from the nucleoli, which are only weakly stained by neutral red (nucleoli are more strongly stained by light cresyl violet or hematoxylin counterstaining, but are still easily differentiated from the inclusions—data not shown) and maintains an irregularly shaped appearance in contrast to the round appearance of inclusions in neurons in CGG KI mice. These inclusions could also be identified by hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining as well, but immunocytochemistry was run to verify the presence of inclusions, as inclusions in the CGG KI mouse model have not been previously visualized with H&E staining (cf. Brouwer, et al., 2008a,b; Willemsen, et al., 2003).

Figure 4. Intranuclear Inclusions in 12, 24, and 48 Week Old Animals Stained for Ubiquitin and Countertained with Neutral Red.

A. 12 Week old animals have inclusions in the dentate gyrus granule cells, but (B) not in the parietal cortex C. 24 Week old animals have inclusions in the dentate gyrus granule cells, but (D) not in the parietal cortex. cortex. E. 48 week old animals have inclusions in the granule cells in the dentate gyrus, and, (F) in the parietal cortex. Arrowheads point to neurons with ubituitin stained intranuclear inclusions. Insets show a representative cell enlarged to show inclusions. Scale bar in D is 50 μM and applies to all plates, but not to inserts.

As early as 12 weeks of age, the CGG KI mice showed the presence of intranuclear inclusions in the dentate gyrus granule cells in the hippocampus as well as some interneurons in the inner molecular layer and hilus. At this age, no inclusions were found in the parietal cortex. At 24 weeks of age, there were a greater number of inclusions in the dentate gyrus, a few in the pyramidal cell layer and stratum radiatum in the hippocampus (esp. CA1), but only rarely in the parietal cortex. At 48 weeks, the CGG KI mice showed the presence of intranuclear inclusions both in the dentate gyrus and pyramidal cell layers of the hippocampus as well as intranuclear inclusions in the parietal cortex. Additionally, these inclusions appeared to be larger in the older mice in the dentate gyrus and the inclusions in the cortex were larger on average than those in the dentate gyrus.

Intranuclear inclusions were also present in the 12 week old CGG KI mice in a very limited number of granule cells in the cerebellum as well as in periglomerular granule cells of the olfactory bulb, as well as rarely present in large neurons in the brainstem (data not shown). The presence of inclusions in these regions was also identified in older mice (24 and 48 week old CGG KI mice). At 24 weeks of age, there were never any inclusions in the neocortex, but the inclusions in the hippocampus were more numerous and slightly larger than those at 12 weeks. In the 48 week old CGG KI mice, inclusions became prevalent in the limbic system, specifically the lateral entorhinal cortex as well as the retrosplenial/anterior cingulate cortices. Furthermore, at 48 weeks of age intranuclear inclusions appeared in the neocortex, specifically the parietal cortex, rostral cortex, and occipital cortex. As reported previously, there also were intranuclear inclusions in the amygdala and periamygdalar cortices (Brouwer, et al., 2008b; Willemsen, et al., 2003). There was also a clear developmental trajectory in the size of inclusions, with intranuclear inclusions being qualitatively larger in each age group (e.g. inclusion size at 12 week old < 24 week old < 48 week old). In no cases were inclusions ever present in littermate wildtype mice run in parallel with CGG KI mice (data not shown).

Discussion

Previous studies have shown that CGG KI mice carrying an expanded CGG trinucleotide repeat in the 5’-untranslated region of the Fmr1 gene develop several of the neuropathological characteristics of fragile X associated tremor/ataxia (FXTAS) in humans (Brouwer, et al., 2008a,b,c; Willemsen, et al., 2003). It has been more difficult, however, to characterize cogntive deficits in this CGG KI mouse. To date, only a single study has attempted to characterize learning and memory performance in these CGG KI mice. In the study by Van Dam et al., one year-old CGG KI mice showed relatively subtle spatial learning deficits on the water maze (Van Dam, et al., 2005). It should be mentioned that the mice used in the Van Dam et al. (2005) study were on a mixed FVB/N × C57BL/6J background, whereas those used in the present study were on a C57BL/6J background.

The present experiments were conducted in similar mice carrying CGG repeat expansions ranging from CGG80 to CGG180 in order to extend the findings from the water maze to a spatial task that explored metric and topological spatial information processing. Our results reveal that these CGG KI mice show age-related deficits in spatial processing for both the metric and topological tasks. At both 12 and 24 weeks of age, the CGG KI mice showed a marked failure to detect changes in the distance between a pair of objects (e.g. metric changes). However, these same animals were fully capable of detecting a change when the objects were transposed (e.g. topological changes). At 48 weeks of age, the CGG KI mice failed to detect either metric or topological changes in object position. FXTAS has been described as a late developing neurodegenerative disease that manifests around the 6th decade of life in affected carriers (Hagerman & Hagerman, 2004). These results in CGG KI mice showing cognitive impairment in the metric task as early as 12 weeks of age suggest that there may also be cognitive impairments in FXTAS at earlier ages than previous thought (cf. Cornish, et al., 2007; Farzin, et al., 2006; Goodin-Jones, et al., 2004; Hagerman, 2006; Hessl, et al., 2005; Jakala, et al., 1997; Koldewyn, et al., 2008; Sevin, et al., in press; for examples of cogntive deficits in young carriers of the fragile X premutation). Further experiments are currently underway to more thoroughly characterize spatial and temporal processing in the CGG KI mouse model of the fragile X premutation using more traditional assays (e.g. water maze, elevated plus maze, associative learning tasks, etc) to more thoroughly characterize any alterations in memory processes, potential ataxia or tremors in these mice, as well as to more fully characterize any potential anxiety/depressive symptoms that have been reported in carriers of the fragile X premutation (Bourgeois, et al., 2009).

These results in mice are consistent with several theories that propose that poor spatial resolution contributes to the overall cognitive deficits that are present in some neurodevelopmental and neurodegenerative diseases (Simon, 2008; cf. Rolls & Kesner, 2006). These theories suggest that a fundamental “hypergranularity” (Simon, 2008), or lack of precision in spatial and/or temporal processing (Rolls & Kesner, 2006) interferes with the formation of memory by reducing the efficiency of how sensory stimuli are processed. Similar models have been proposed for rodents that emphasizes the precise nature of information processing over performance on learning and memory tasks (Kesner, 1991; Kesner, et al., 2003; Rolls & Kesner, 2006). Under these models, fine spatial resolution (or metric processing) is associated with functions attributed to the hippocampus (esp. dentate gyrus), whereas the processing of topological information is associated with functions attributed to the parietal cortex (Goodrich-Hunsaker, et al., 2005; Goodrich-Hunsaker, et al., 2008a; cf. Lee, et al., 2009).

Considered within these theories focusing on spatial processing, the present data suggest that early deficits (at 12 and 24 weeks) in spatial information processing in CGG KI mice fall within the domain of deficits in metric information processing and may therefore be related to similar studies in rats that associate metric impairments with dysfunction to the dentate gyrus (Goodrich-Hunsaker, et al., 2005, 2008b; Hunsaker et al., 2008). The additional spatial deficits that appear later in development (at 48 weeks) in the CGG KI mice appear to fall within the topological domain and, based on similar studies in rats, suggest dysfunction in the parietal cortex leading to poor processing of topological information (Goodrich-Hunsaker, et al., 2005, 2008a; Lee, et al., 2009). The present behavioral data showing more complex deficits in spatial processing are also consistent with the progressive neuropathology that has been reported previously in this CGG KI mouse model of FXTAS. Specifically, intranuclear inclusions have been shown to become increasingly prominent in the hippocampus and neocortex, including the parietal cortex, at more advanced ages (Willemsen, et al., 2003). These neuropathological findings concerning intranuclear inclusions were essentially replicated in the present study. That is, development of inclusions was progressive, with inclusions present in the brain as early as 12 weeks of age, appearing at earlier ages in the dentate gyrus in the hippocampus and then later in the overlying parietal cortex. Furthermore, if these intranuclear inclusions truly reflect some type of damaging neuronal pathology, then it is reasonable to consider the possibility that poor metric processing in CGG KI mice may be related to abnormalities in dentate gyrus granule cell function. It is important to note that at 12 and 24 weeks of age, the parietal cortex was almost completely devoid of inclusions. At 48 weeks of age, there were inclusions in both the dentate gyrus and pyramidal cell layers of the hippocampus (perhaps deleteriously affecting metric spatial information processing) as well as the parietal cortex, which could potentially contribute to poor topological spatial information processing in the CGG KI mouse at 48 weeks of age but not at earlier ages.

In summary, the present experiment provides evidence for a spatial processing deficits in early adulthood in CGG KI mice used to model clinical FXTAS. These mice at relatively young ages (12 and 24 weeks) showed deficits for processing metric relationships between objects, a process associated with functions of the dentate gyrus in the hippocampus. Later in development (at 48 weeks of age) mice showed deficits for both metric as well as topological spatial processing, the latter of which may be subserved by the parietal cortex. The nature of the cognitive deficits may also relate to the development of the intranuclear pathology in the hippocampus and parietal cortex during development. Considered together these data demonstrate a progressive development of complex spatial information processing deficits in CGG KI mice that appear to be related to presence of intranuclear inclusions in hippocampus and parietal cortex. The present data also demonstrate the usefulness of behavioral paradigms, such as those used in the present studies, that are designed to assess specific types of spatial processing (e.g., metric and topological). Such tests may provide a valuable tool for identifying early cognitive deficits in mouse models of neurological disorders as well as providing a behavioral outcome measure for potential pharmacological interventions (cf. Rolls & Kesner, 2006; Simon, 2008).

Acknowledgments

The authors with to thank Drs. Tony J. Simon, Susan M. Rivera, and Paul J. Hagerman for helpful discussions concerning portions of this experiment. This research was supported by grants NINDS RL1 NS 062411 and NID CR UL1 RR024922 to RFB.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: The following manuscript is the final accepted manuscript. It has not been subjected to the final copyediting, fact-checking, and proofreading required for formal publication. It is not the definitive, publisher-authenticated version. The American Psychological Association and its Council of Editors disclaim any responsibility or liabilities for errors or omissions of this manuscript version, any version derived from this manuscript by NIH, or other third parties. The published version is available at www.apa.org/pubs/journals/bne

References

- Arocena DG, Iwahashi CK, Won N, Beilina A, Ludwig AL, Tassone F, et al. Induction of inclusion formation and disruption of lamin A/C structure by premutation CGG-repeat RNA in human cultured neural cells. Human Molecular Genetics. 2005;14(23):3661–3671. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bontekoe CJ, de Graaff E, Nieuwenhuizen IM, Willemsen R, Oostra BA. FMR1 premutation allele (CGG)81 is stable in mice. European Journal of Human Genetics. 1997;5(5):293–298. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourgeois JA, Coffey SM, Rivera SM, Hessl D, Gane LW, Tassone F, et al. A review of fragile X premutation disorders: expanding the psychiatric perspective. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2009;70(6):852–862. doi: 10.4088/JCP.08m04476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brouwer JR, Huizer K, Severijnen LA, Hukema RK, Berman RF, Oostra BA, et al. CGG-repeat length and neuropathological and molecular correlates in a mouse model for fragile X-associated tremor/ataxia syndrome. Journal of Neurochemistry. 2008a;107(6):1671–1682. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2008.05747.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brouwer JR, Severijnen E, de Jong FH, Hessl D, Hagerman RJ, Oostra BA, Willemsen R. Altered hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal gland axis regulation in the expanded CGG repeat mouse model for fragile X-associated tremor/ataxia syndrome. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2008b;33(6):863–873. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2008.03.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brouwer JR, Willemsen R, Oostra B. The FMR1 gene and fragile X-associated tremor/ataxia syndrome. American Journal of Medical Genetics Part B, Neuropsychiatric Genetics. 2008c doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.30910. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunberg JA, Jacquemont S, Hagerman RJ, Berry-Kravis EM, Grigsby J, Leehey MA, Tassone F, Brown WT, Greco CM, Hagerman PJ. Fragile X premutation carriers: characteristic MR imaging findings of adult male individuals with progressive cerebellar and cognitive dysfunction. American Journal of Neuroradiology. 2002;23(10):1757–1766. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornish K, Li L, Kogan C, Jacquemont S, Turk J, Dalton A, et al. Age-dependent cognitive changes in carriers of the fragile X syndrome. Cortex. 2007;44(6):628–436. doi: 10.1016/j.cortex.2006.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farzin F, Perry H, Hessl D, Loesch D, Cohen J, Bacalman S, et al. Autism spectrum disorders and attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder in boys with the fragile X premutation. Journal of Developmental & Behavioral Pediatrics. 2004;27:S137–144. doi: 10.1097/00004703-200604002-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallistel CR. The organization of learning. MIT Press; Cambridge: MA: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert PE, Kesner RP, Lee I. Dissociating hippocampal subregions: double dissociation between dentate gyrus and CA1. Hippocampus. 2001;11(6):626–636. doi: 10.1002/hipo.1077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodin-Jones BL, Tassone F, Gane LW, Hagerman RJ. Autism spectrum disorder and the fragile X premutation. Journal of Developmental & Behavioral Pediatrics. 2004;25:392–398. doi: 10.1097/00004703-200412000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodrich-Hunsaker NJ, Hunsaker M, Kesner RP. Dissociating the role of the parietal cortex and dorsal hippocampus for spatial information processing. Behavioral Neuroscience. 2005;119(5):1307–1315. doi: 10.1037/0735-7044.119.5.1307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodrich-Hunsaker NJ, Howard BP, Hunsaker MR, Kesner RP. Human topological task adapted for rats: spatial information processes of the parietal cortex. Neurobiology of Learning and Memory. 2008a;90(2):389–394. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2008.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodrich-Hunsaker NJ, Hunsaker M, Kesner RP. The interactions and dissociations of the dorsal hippocampus subregions: How the dentate gyrus, CA3, and CA1 process spatial information. Behavioral Neuroscience. 2008b;122(1):16–26. doi: 10.1037/0735-7044.122.1.16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greco CM, Berman RF, Martin RM, Tassone F, Schwartz PH, Chang A, et al. Neuropathology of fragile X-associated tremor/ataxia syndrome (FXTAS) Brain. 2006;129(Pt 1):243–255. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greco CM, Tassone F, Chudley AE, Del Bigio MR, Jacquemont S, Leehey M, et al. Neuronal intranuclear inclusions in a new cerebellar tremor/ataxia syndrome among fragile X carriers. Brain. 2002;125(Pt 8):1760–1771. doi: 10.1093/brain/awf184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagerman PJ, Hagerman RJ. The Fragile-X Premutation: A Maturing Perspective. American Journal of Human Genetics. 2004;74(5):805–816. doi: 10.1086/386296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagerman RJ. Lessons from fragile X regarding neurobiology, autism, and neurodegeneration. Journal of Developmental & Behavioral Pediatrics. 2006;27:63–74. doi: 10.1097/00004703-200602000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hessl D, Tassone F, Loesch DZ, Berry-Kravis E, Leehey MA, Gane LW, et al. Abnormal elevation of FMR1 mRNA is associated with psychological symptoms in individuals with the fragile X premutation. American Journal of Medical Genetics, B Neuropsychiatric Genetics. 2005;139B:115–121. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.30241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunsaker M, Rosenberg J, Kesner RP. The role of the dentate gyrus, CA3a,b, and CA3c for detecting spatial and environmental novelty. Hippocampus. 2008;18(10):1064–1073. doi: 10.1002/hipo.20464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jakala P, Hanninen T, Ryynanen M, Laakso M, Partanen K, Mannermaa A, Soininen H. Fragile-X: Neuropsychological test performance, CGG triplet repeat lengths, and hippocampal volumes. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 1997;100(2):331–338. doi: 10.1172/JCI119538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kesner RP. The role of the hippocampus within an attribute model of memory. Hippocampus. 1991;1(3):279–282. doi: 10.1002/hipo.450010316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kesner RP, Gilbert PE, Wallenstein GV. Testing neural network models of memory with behavioral experiments. Current Opinion in Neurobiology. 2000;10(2):260–265. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(00)00067-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kesner RP, Lee I, Gilbert P. A behavioral assessment of hippocampal function based on a subregional analysis. Reviews in the Neurosciences. 2003;15(5):333–351. doi: 10.1515/revneuro.2004.15.5.333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koldewyn K, Hessl D, Adams J, Tassone F, Hagerman RJ, Hagerman PJ, et al. Reduced hippocampal activation during recall is associated with elevated fmr1 mRNA and psychiatric symptoms in men with the fragile-x premutation. Brain Imaging and Behavior. 2008;2:105–116. doi: 10.1007/s11682-008-9020-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JY, Huerta PT, Zhang J, Kowal C, Bertini E, Volpe BT, Diamond B. Neurotoxic autoantibodies mediate congenital cortical impairments of offspring in maternal lupus. Nature Medicine. 2009;15(1):91–96. doi: 10.1038/nm.1892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marr D. Simple memory: a theory for archicortex. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London B Biological Sciences. 1971;262(841):23–81. doi: 10.1098/rstb.1971.0078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNaughton BL, Morris RGM. Hippocampal synaptic enhancement and information storage within a distributed memory system. Trends in Neuroscience. 1987;10:408–415. [Google Scholar]

- Oostra BA, Willemsen R. FMR1: A gene with three faces. Biochimica at Biopysica Acta. 2009;1790(6):467–477. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2009.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rolls E, Kesner RP. A computational theory of hippocampal function, and empirical tests of the theory. Progress in Neurobiology. 2006;79(1):1–48. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2006.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sevin M, Kutalik Z, Bergmann S, Vercelletto M, Renou P, Lamy E, Vingerhoets F, Di-Virgilio G, Boisseau P, Bezieau S, Pasquier L, Rival J-M, Beckmann J, Damier P, Jacquemont S. The penetrance of marked cognitive impairment in older maile carriers of the FMR1 gene premutation. Journal of Medical Genetics. 2009 doi: 10.1136/jmg.2008.065953. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon TJ. A new account of the neurocognitive foundations of impairments in space, time and number processing in children with chromosome 22q11.2 deletion syndrome. Developmental Disabilities Research Reviews. 2008;14(1):48–58. doi: 10.1002/ddrr.8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tassone F, Garcia-Arocena D, Khandjian EW, Greco CM, Hagerman PJ. Intranuclear inclusions in neural cells with premutation alleles in fragile X associated tremor/ataxia syndrome. Journal of Medical Genetics. 2004;41(4):e43. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2003.012518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Dam D, Errijgers V, Kooy RF, Willemsen R, Mientjes E, Oostra BA, et al. Cognitive decline, neuromotor and behavioural disturbances in a mouse model for fragile-X-associated tremor/ataxia syndrome (FXTAS) Behavioural Brain Research. 2005;162(2):233–239. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2005.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willemsen R, Hoogeveen-Westerveld M, Reis S, Holstege J, Severijnen LA, Nieuwenhuizen IM, et al. The FMR1 CGG repeat mouse displays ubiquitin-positive intranuclear neuronal inclusions; implications for the cerebellar tremor/ataxia syndrome. Human Molecular Genetics. 2003;12(9):949–959. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddg114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]