Abstract

Esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC) is one of the most aggressive forms of squamous cell carcinomas. Common genetic lesions in ESCC include p53 mutations and EGFR overexpression, both of which have been implicated in negative regulation of Notch signaling. In addition, cyclin D1 is overexpressed in ESCC and can be activated via EGFR, Notch and Wnt signaling. To elucidate how these genetic lesions may interact during the development and progression of ESCC, we tested a panel of genetically engineered human esophageal cells (keratinocytes) in organotypic 3D culture (OTC), a form of human tissue engineering. Notch signaling was suppressed in culture and mice by dominant negative Mastermind-like1 (DNMAML1), a genetic pan-Notch inhibitor. DNMAML1 mice were subjected to 4-Nitroquinoline 1-oxide-induced oral-esophageal carcinogenesis. Highly invasive characteristics of primary human ESCC were recapitulated in OTC as well as DNMAML1 mice. In OTC, cyclin D1 overexpression induced squamous hyperplasia. Concurrent EGFR overexpression and mutant p53 resulted in transformation and invasive growth. Interestingly, cell proliferation appeared to be regulated differentially between those committed to squamous-cell differentiation and those invading into the stroma. Invasive cells exhibited Notch-independent activation of cyclin D1 and Wnt signaling. Within the oral-esophageal squamous epithelia, Notch signaling regulated squamous-cell differentiation to maintain epithelial integrity, and thus may act as a tumor suppressor by preventing the development of a tumor-promoting inflammatory microenvironment.

Keywords: Esophageal squamous cell carcinoma, organotypic 3D culture, EGFR, P53, cyclin D1, Wnt, Notch, squamous-cell differentiation, invasion, 4-Nitroquinoline 1-oxide

Introduction

Esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC) is one of the most aggressive forms of squamous cell carcinomas (SCCs) [1,2] and defined as a malignant epithelial tumor with variable squamous-cell differentiation [3]. Common genetic lesions in ESCC include inactivation of the p53, p16INK4A and p120catenin tumor suppressor genes and overexpression of the cyclin D1 and EGFR oncogenes [4,5]. EGFR and cyclin D1 are upregulated and p53 mutations are also found in premalignant ESCC lesions, including squamous dysplasia [6-9]. In addition to mouse models, genetically engineered human esophageal cells (keratinocytes) have served as a platform to investigate esophageal tumor biology [10-12]. In particular, organotypic 3D culture (OTC) is a powerful type of human tissue engineering that facilitates esophageal epithelia reconstitution in vitro with recapitulation of human pathology [13], revealing, for example, highly invasive characteristics of transformed human esophageal cells associated with epithelial mesenchymal transition (EMT) [11,12,14,15].

Cell proliferation and differentiation within the stratified squamous epithelia are regulated by Notch signaling [16-18]. Notch ligands stimulate Notch receptor molecules on adjacent signaling receiving cells through cell-cell contact. Ligand binding triggers a series of enzymatic cleavages of the Notch receptor, leading to generation and nuclear translocation of the intracellular domain of Notch (ICN). ICN forms a transcriptional activation complex containing a transcription factor CSL-CBF-1/RBP-jκ, Su(H), Lag-1-and the coactivator Mastermind-like (MAML) [19]. Notch target genes include the HES/HEY family of transcription factors.

In the normal esophagus, Notch regulates squamous-cell differentiation [18]. Downregulation of Notch signaling may lead to attenuation of squamous-cell differentiation and enhancement of an invasive subset of ESCC cells [20]. In genetically engineered mouse models, loss of Notch receptor family members or expression of dominant negative MAML1 (DNMAML1), a genetic pan-Notch inhibitor, promotes cutaneous SCC [21-24]. Loss-of-function somatic mutations of Notch receptor paralogs have recently been found in primary SCCs [25-27]. Thus, Notch may act as a tumor suppressor in SCCs.

Functional interplay between Notch and various oncogenes and tumor suppressor genes is implicated in a variety of cancers. In particular, the p53 tumor suppressor protein transactivates Notch1 directly, and thus, p53 dysfunction may lead to the inactivation of Notch signaling [22,28]. EGFR may suppress p53-mediated transcription of Notch1 [29] in epidermal keratinocytes and SCC cells. By contrast, EGFR activation in cutaneous SCC is induced by loss of Notch signaling in mice [30,31]. Both EGFR and Notch signaling may activate the transcription of cyclin D1 gene [32-34].

Herein, we carried out functional studies in OTC with a panel of genetically engineered human esophageal cells in the presence or absence of DNMAML1. Additionally, mice carrying DNMAML1 targeted to oral, esophageal and forestomach squamous epithelia were exposed to 4-Nitroquinoline 1-oxide (4-NQO), a chemical carcinogen. These model systems reveal activation of Wnt signaling and cyclin D1 upregulation in invasive cells through functional interplay between EGFR and mutant p53. Furthermore, there is evidence for a tumor suppressor role for canonical Notch signaling in regard to maintenance of squamous-cell differentiation and epithelial integrity, providing novel mechanistic insights into the pathogenesis of ESCC.

Materials and methods

Tissue samples

Primary ESCC and adjacent normal tissues were procured via surgery from informed-consent patients in accordance with Institutional Review Board standards and guidelines as described previously [35].

Cell cultures and treatment

EPC2-hTERT, established by immortalizing primary normal human esophageal epithelial cells, and derivatives were grown and subjected to OTC as described [10-12,15,18,36,37] ([38] for detailed protocols). In brief, 0.5 x 106 of epithelial cells were seeded on top of the collagen/Matrigel matrices containing FEF3 human fetal esophageal fibroblasts, and grown in submerged conditions for 4 days. Cultures were then raised to the air-liquid interface for additional 4 days and harvested for morphological assessment. Each OTC experiment was performed in triplicate. Cells were treated with 10 μM IWR-endo (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA), a pharmacological Wnt inhibitor and 10 μM IWR-exo (Santa Cruz), an inactive control agent [39]. Doxycycline (Dox) was used at 2 μg/ml in the tetracycline-regulatable (Tet-Off) system.

Retrovirus-mediated gene transfer

Retroviral vectors expressing EGFR (pFB-Neo), p53R175H (pBABE-puro or pBABE-zeoloxP), cyclin D1 (pBABE-bla or pBPSTR-D1 [40]), DNMAML1 (MigRI) were stably transduced into EPC2-hTERT cells. Cells were treated with 300 μg/ml of G418 (Invitrogen), 1 μg/ml of Puromycin (Invitrogen), 5 μg/ml Blasticidin S (Invitrogen) or 0.5 μg/ml zeocin (Invitrogen) for selection as described [11,12,18,36,38]. Cells transduced with MigRI were subjected to flow sorting to collect cells expressing the brightest level (top 20%) of green fluorescent protein (GFP) as described [18,37].

Real-time reverse-transcription polymerase chain reactions (RT-PCR)

Real-time RT-PCR assays were done using TaqMan® Gene Expression Assay (Applied Biosystems) for cyc l in D1 (CCND1, Hs00765553_m1) as described [11,18].

Western blotting

Western blotting for EGFR, p53, cyclin D1, GFP (for DNMAML1 expressed as a GFP-fusion protein) and β-actin (loading control) was done as described [11,18,37].

K14Cre;DNMAML1 Mice and 4-NQO treatment

K14Cre;DNMAML1 mice were described previously [18]. In brief, mice carrying Lox-STOP-Lox DNMAML1 [41] were intercrossed with K14Cre transgenic mice [42], targeting DNMAML1 into the basal cell layer of the stratified squamous epithelia. 4-7 month-old K14Cre;DNMAML1 and control littermates were treated with 100 μg/ml 4-NQO (Sigma Aldrich) or 2% propylene glycol (MP Biomedicals, Solon, OH)(vehicle control) in drinking water for up to 18 days and followed up for 8 weeks after 4-NQO withdrawal. All experiments were done under approved protocols from the University of Pennsylvania Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and NIH guidelines.

Histology, immunohistochemistry (IHC) and immunofluorescence (IF)

Hematoxylin and Eosin (H&E) staining, IHC and IF were performed as described [18,35-37]. Sections were incubated with anti-Ki-67 polyclonal antibody (1:1,500; Novocastra, Bannockburn, IL), anti-cyclin D1 monoclonal antibody (1:700; Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL), anti-cytokeratin 14 (CK14) polyclonal antibody (1:5000; Covance, Princeton, NJ), anti-Involucrin (IVL) monoclonal antibody (Sigma, St Louis, MO) or anti β-catenin polyclonal antibody (1:300; Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA) overnight at 4°C. For IHC, sections were further incubated with biotinylated secondary IgG and subjected to signal development using the DAB peroxidase substrate with the VECTASTAIN® ABC kit (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA). For IF, sections were incubated with an appropriate Cy2- or Cy3-conjugated secondary antibody (1:400; Jackson ImmunoResearch, West Grove, PA) for 30 min at room temperature. Nuclei were counterstained by 4’, 6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) (1:10,000; Invitrogen). Stained slides were examined with a Nikon Microphot microscope and imaged with a digital camera at specific magnifications. Labeling indices (LI) for Ki-67 and cyclin D1 were determined by counting at least 600 cells per x200 microscopic field. For OTC, five to seven pictures were taken for each sample to determine average epithelial thickness. Cell invasion was assessed by counting all invasive nests per slide on at least 5 sections.

Statistical analysis

Data from real-time RT-PCR assays and morphological assessment of OTC including epithelial thickness, invasiveness, Ki-67 and cyclin D1 LI were presented as mean ± SE and were analyzed by two-tailed Student’s t test. Fisher's exact test was done to assess whether inflammation and dysplasia were associated with genotype and/or phenotype in mice by location. P <0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Results

Generation of a panel of genetically engineered human esophageal epithelial cells

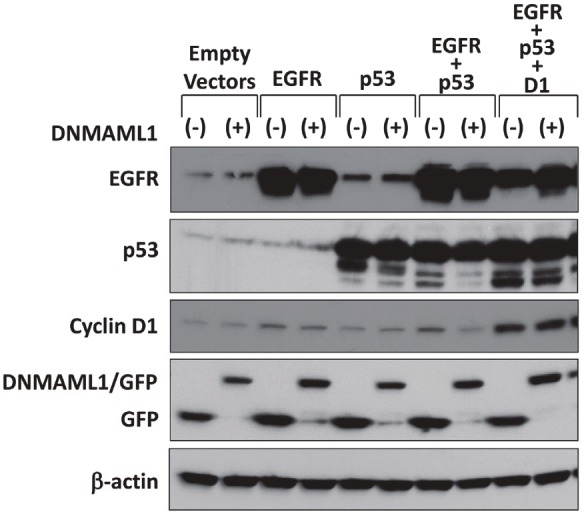

We have demonstrated previously that both EGFR and p53R175H are necessary and sufficient for malignant transformation of human esophageal cells EPC2-hTERT [12] and for enrichment of EMT-competent cells capable of invasive growth [11,15]. DNMAML1-mediated inhibition of Notch signaling sharply suppressed squamous-cell differentiation in EPC2-hTERT and its transformed derivative EPC2T which carries cyclin D1, EGFR and p53R175H transgenes concurrently [18,37]. Moreover, DNMAML1 facilitated EMT and invasive growth of EPC2T cells [37]. To better define the individual contribution of these genetic factors to esophageal carcinogenesis, we created a panel of genetically engineered EPC2-hTERT derivatives carrying cyclin D1, EGFR and p53R175H, either alone or in combinations, both in the presence and absence of DNMAML1 (Figure 1 and data not shown). EPC2-hTERT and EPC2T cells with or without DNMAML1 [18,37] served as controls.

Figure 1.

Generation of a panel of genetically engineered human esophageal epithelial cell lines with or without DNMAML1. Derivatives of EPC2-hTERT [10] expressing empty vectors only (parental), EGFR only (EGFR), p53R175H only (p53), EGFR and p53R175H (EGFR + p53) have been described [11]. These cell lines were stably transduced with either GFP (control) or DNMAML1 as previously described to generate EPC2-T cells (EGFR + p53 + D1) expressing either GFP or DNMAML1 [18,37]. Western blotting documented indicated molecules with β-actin as a loading control. Empty vectors, parental EPC2-hTERT cells with empty vectors only; EGFR, EGFR overexpression; p53, p53R175H; and D1, cyclin D1 overexpression.

Cyclin D1 overexpression induces squamous hyperplasia in OTC

In OTC, we first evaluated reconstituted epithelia formed in the absence of DNMAML1 expression. Cyclin D1 overexpression alone resulted in squamous hyperplasia with increased epithelial thickness (Figure 2A and 2B) and cell proliferation as indicated by an increase in overall and basal cell-specific Ki-67 LI (Figure 3A-C). We determined basal cell-specific Ki-67 LI since Ki-67 positive cells were typically localized within the basal cell layer (Figure 3A), suggesting that the total number of Ki-67 negative cells may reduce the overall Ki-67 LI in the epithelia demonstrating greater stratification due to increased suprabasal cell layers. Unlike cyclin D1, neither EGFR alone nor p53R175H alone increased epithelial thickness (Figure 2A and 2B) or basal cell-specific Ki-67 LI (Figure 3C). Moreover, addition of either EGFR or p53R175H into the cells overexpressing cyclin D1 did not increase epithelial thickness (Figure 2A and 2B) and basal cell-specific Ki-67 LI (Figure 3C), suggesting that cyclin D1 may have a central role in stimulating basal cell proliferation. Such a premise was corroborated in the tetracycline regulatable (Tet-off) system where repression of cyclin D1 transgene resulted in a decrease in the epithelial thickness as well as in the number of cyclin D1 and Ki-67 positive cells (Figure 4). In addition, cyclin D1 overexpression increased cell layers expressing CK14, a marker of basal keratinocytes (Figures 4B and Figure 5). These data suggest that cyclin D1 stimulates basal cell proliferation and delays terminal differentiation in the squamous epithelium.

Figure 2.

Morphology of OTC with genetically engineered human esophageal epithelial cell lines with or without DNMAML1. Cell lines with indicated genotypes expressing either DNMAML1 or GFP (control) were grown in OTC to reconstitute stratified squamous epithelia. Sections from the paraffin embedded end products were subjected to H&E staining (A) to assess epithelial thickness (B) and cell invasion (C). Note that DNMAML1 suppressed epithelial thickness and stimulated cell invasion into the stroma, in particular in the cells carrying EGFR and p53R175H concurrently. Parental, EPC2-hTERT with empty vectors only; EGFR, EGFR overexpression; p53, p53R175H; and D1, cyclin D1 overexpression. Epi, epithelium; Str, stroma; Scale bar, 100 μm. #, P< 0.05 vs. GFP, n=5. *, P< 0.05 vs. Parental + GFP, n=5. **, P< 0.01 vs. Parental + DNMAML1, n=5.

Figure 3.

Assessment of cell proliferation in OTC with genetically engineered human esophageal epithelial cell lines with or without DNMAML1. Cell lines with indicated genotypes expressing either DNMAML1 or GFP (control) were grown in OTC to reconstitute stratified squamous epithelia. Serial sections from the paraffin embedded end products from Figure 2A were subjected to IHC for Ki-67 (A), to determine overall Ki-67 LI (B), basal cell-specific Ki-67 LI (C) and compartment-specific Ki-67 LI (D). Parental, EPC2-hTERT with empty vectors only; EGFR, EGFR overexpression; p53, p53R175H; and D1, cyclin D1 overexpression. Epi, epithelium; Str, stroma; Scale bar, 50 μm. #, P< 0.05 vs. GFP (B, C); n=5. #, P< 0.05 vs. epithelial compartment (D); n=5. *, P< 0.05 vs. Parental + GFP, n=5. **, P< 0.01 vs. Parental+DNMAML1, n=5.

Figure 4.

Cyclin D1 induces squamous hyperplasia in OTC. EPC2-hTERT cells with tetracycline-regulatable (Tet-Off) cyclin D1 were grown in the absence [Dox (-)] or presence of 2 μg/ml Doxycycline [Dox (+)] in monolayer culture or OTC. In (A), cyclin D1 was determined by real-time RT-PCR (left) with β-actin as an internal control and Western blotting with β-actin as a loading control (right). *, P< 0.01, vs. Dox (-); n=3. In (B), serial sections from the paraffin embedded end products of OTC were subjected to H&E staining, IHC for cyclin D1 and Ki-67, and IF for CK14 (red) and IVL (green) with DAPI (blue) to assess morphology, cyclin D1 expression, proliferation and differentiation markers, respectively in the reconstituted stratified squamous epithelia. Epi, epithelium; Str, stroma; Scale bar, 50 μm. In (C), epithelial thickness and overall Ki-67 LI were determined using the H&E and Ki-67 stained samples from (B). *, P< 0.05 vs. Dox (-); n=5

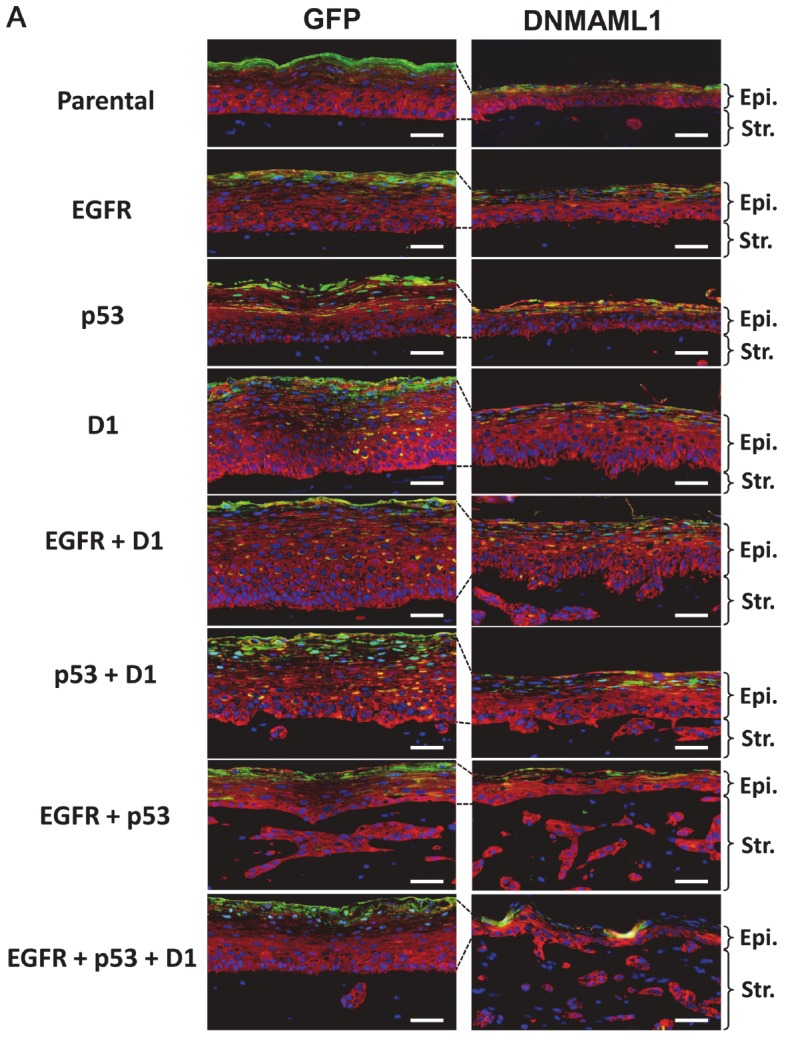

Figure 5.

Assessment of squamous-cell differentiation in OTC with genetically engineered human esophageal epithelial cell lines with or without DNMAML1. Cell lines with indicated genotypes expressing either DNMAML1 or GFP (control) were grown in OTC to reconstitute stratified squamous epithelia. Serial sections from the paraffin embedded end products from Figure 2A were subjected to IF for CK14 (red) and IVL (green) with DAPI (blue). Parental, EPC2-hTERT with empty vectors only; EGFR, EGFR overexpression; p53, p53R175H; and D1, cyclin D1 overexpression. Epi, epithelium; Str, stroma; Scale bar, 50 μm.

Transformed cells with concurrent EGFR overexpression and p53 mutation display invasive growth without requiring ectopically expressed cyclin D1

When OTC was performed with transformed cells carrying EGFR and p53R175H concurrently, epithelial thickness was suppressed greatly (Figure 2A and 2B). Instead, cell invasion into the stromal compartment was enhanced (Figure 2A and 2C) as described previously [12,15]. Addition of ectopic cyclin D1 transgene to this genotype increased epithelial thickness and basal-cell specific Ki-67 LI only modestly (Figure 2A and 2B; Figure 3A and 3C). Interestingly, overall Ki-67 LI was found to be greatest in cells carrying both EGFR and p53R175H transgenes, with or without cyclin D1 transgene (Figure 3B). We suspected that cell proliferation may be augmented in the invasive cells within the stromal compartment. When we assessed Ki-67 LI in a compartment-specific manner (Figure 3D), cells invading into underlying stroma exhibited significantly higher Ki-67 LI than those within the epithelial compartment. Moreover, ectopically expressed cyclin D1 influenced Ki-67 LI only minimally in the stromal compartment. These findings suggest that transformed esophageal cells may contain a subset of cells that is more committed to downward invasive growth and capable of proliferating actively without requiring ectopically expressed cyclin D1.

Notch inhibition impairs epithelial stratification and facilitates invasive growth in transformed cells with concurrent EGFR overexpression and p53 mutation

Activation of Notch signaling occurs at the onset of squamous-cell differentiation in normal esophageal epithelial cells [18]. We next determined the impact of genetic pan-Notch inhibition on reconstituted epithelium. DNMAML1 suppressed epithelial stratification in all genotypes (Figure 2A). This was partially antagonized by ectopically expressed cyclin D1 in non-transformed cells (Figure 2A and 2B, see “D1”, “EGFR+D1” and “p53+D1” under the column for DNMAML1 in A) with increased CK14-positive basal and parabasal cell layers in the presence of DNMAML1 (Figure 5). Thus, cyclin D1 overexpression may increase a pool of basal keratinocytes that cannot undergo terminal differentiation due to Notch inhibition by DNMAML1; however, basal and parabasal cell layers were not extended when DNMAML1 was expressed in transformed cells carrying transgenic EGFR and p53R175H and cyclin D1 (i.e. EPC2T) (Figure 2A, see “EGFR+p53+D1” under the column for DNMAML1 in A). Therefore, cyclin D1 may fail to expand basal and parabasal cell layers once cells are fully transformed to gain invasive characteristics.

DNMAML1 greatly augmented invasive growth of cells transformed by EGFR and p53R175H, but did not require ectopic cyclin D1 expression (Figure 2A and 2C). Given the possibility of negative and positive regulation of Notch1 by EGFR [29] and wild-type p53 [22,28], respectively, EGFR overexpression and p53 dysfunction may lead to impaired squamous-cell differentiation without DNMAML1; however, neither EGFR or p53R175H alone nor combination of the two, inhibited squamous-cell differentiation significantly compared with DNMAML1 (Figure 5). In all genotypes tested, DNMAML1 affected basal cell-specific Ki-67 LI only minimally, if at all, when compared to GFP only-expressing controls (Figure 3C); however, DNMAML1 increased the overall Ki-67LI in the presence of both EGFR and p53R175H (Figure 3B). This was accounted for by a significantly increased Ki-67 LI found specifically within invasive cells (Figure 3D) as DNMAML1 enhanced cell invasion greatly (Figure 2A and 2C).

These findings indicate that squamous-cell differentiation requires canonical Notch signaling. Once Notch signaling is disrupted, cells fail to undergo squamous-cell differentiation. Under such conditions, ectopically overexpressed cyclin D1 may increase proliferative basal keratinocytes in non-transformed cells; however, Notch inhibition in transformed cells facilitates invasive growth in which cell proliferation may be increased without requiring ectopic cyclin D1.

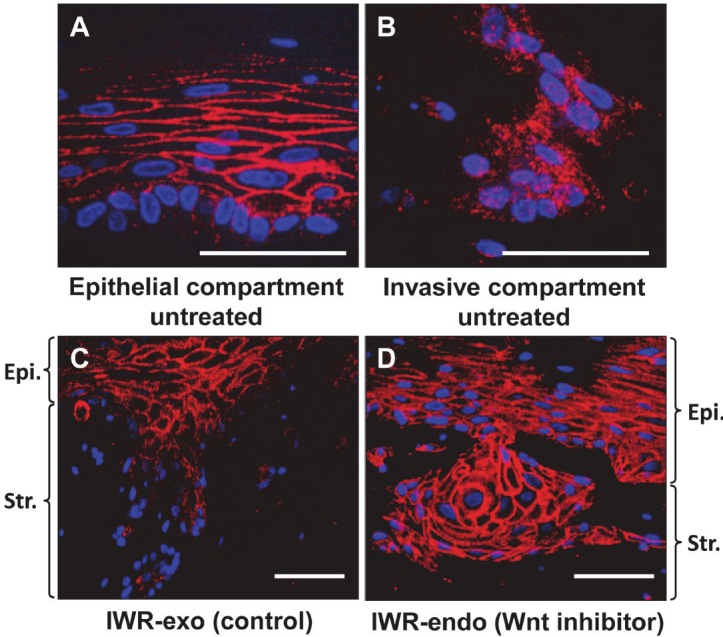

Wnt signaling may regulate proliferation and invasion within the invasive compartment

We explored further how cell proliferation may be stimulated in the invasive cells with concurrent EGFR and p53R175H. Cyclin D1 is a Notch target gene [33]; however, Notch1-mediated cyclin D1 induction was impaired by DNMAML1 in EPC2-hTERT cells (data not shown) along with other Notch target genes as described previously [18]. Thus, it is unlikely that canonical Notch signaling stimulates cell proliferation via cyclin D1 expression in the presence of DNMAML1. We hypothesized that the Wnt pathway may be activated to induce cyclin D1 in invasive cells. When we examined EPC2-hTERT cells expressing EGFR and p53R175H concurrently, β-catenin was localized to the cell membrane within the epithelial compartment (Figure 6A). By contrast, β-catenin was mainly localized to the cytoplasm of invasive cells within the stromal compartment (Figure 6B), suggesting activation of Wnt signaling. A similar pattern of β-catenin expression was observed in transformed cells with DNMAML1 (data not shown). These findings were further corroborated by restoration of β-catenin localization to the cell membrane when OTC was carried out in the presence of IWR-1-endo, a pharmacological Wnt inhibitor, but not with IWR-exo, an inactive control agent (Figure 6C and 6D). Wnt inhibition reduced cell invasion and proliferation, albeit to a modest extent (Figures 7 and 8). Cyclin D1 was found to be upregulated in invasive cells with concurrent EGFR and p53R175H with or without DNMAML1 (Figure 9A and 9C). Wnt signaling may transcriptionally activate cyclin D1; however, IWR-1-endo did not reduce cyclin D1 expression (Figure 9B and 9D). Therefore, cyclin D1 expression in the invasive cells may be regulated via differential mechanisms.

Figure 6.

OTC reveals Wnt activation in the invasive fronts. EPC2-hTERT-EGFR-p53R175H cells [11,12] with GFP (EGFR + p53/GFP) (see Figure 1 for expression) were grown in OTC in the presence or absence (untreated) of either 10 μM IWR-endo (Wnt inhibitor) or 10 μM IWR-exo (control agent) and subjected to IF for β-catenin (red) with DAPI (blue) in (A-D). (A), epithelial compartment (untreated); (B), invas ive compartment (untreated); and (C), IWRexo; (D), IWR-endo. Scale bar, 50 μm.

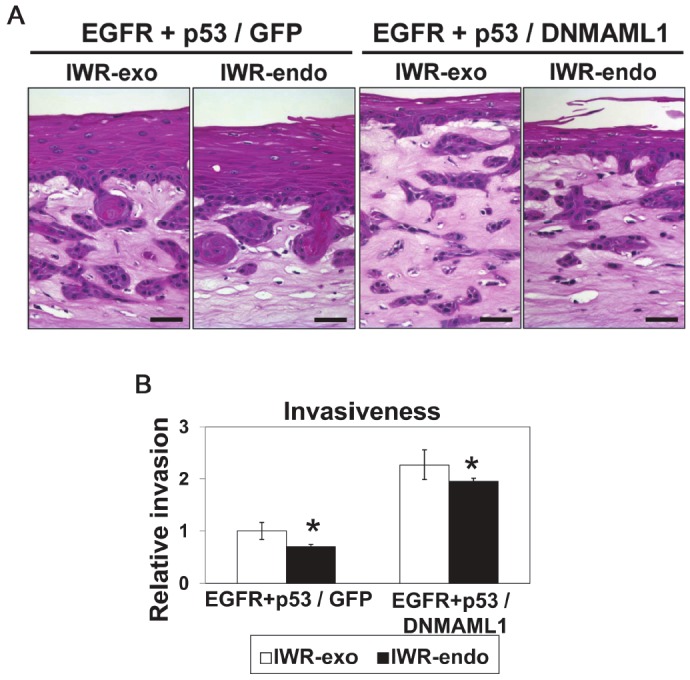

Figure 7.

Wnt inhibition reduces invasion in OTC. EPC2-hTERTEGFR-p53R175H cells [11,12] with GFP (EGFR + p53/GFP) or DNMAML1 (EGFR + p53/DNMAML1) (see Figure 1 for expression) were grown in OTC in the presence or absence (untreated) of either 10 μM IWR -endo (Wnt inhibitor) or 10 μM IWR-exo (control agent) and subjected to H&E staining (A) to assess invasiveness as quantitated in (B). EGFR, EGFR overexpression; p53, p53R175H. Scale bar, 50 μm. *, P< 0.05 vs. IWR-exo; n=6.

Figure 8.

Wnt inhibition reduces cell proliferation in the invasive fronts. EPC2-hTERT-EGFR-p53R175H cells [11,12] with GFP (EGFR + p53/GFP) or DNMAML1 (EGFR + p53/DNMAML1) (see Figure 1 for expression) were grown in OTC in the presence of either 10 μM IWR-endo (Wnt inhibitor) or 10 μM IWR-exo (control agent). Serial sections from the paraffin embedded end products from Figure 7A were subjected to IHC for Ki-67 (A) to determine Ki-67 LI in the invasive nests (B). EGFR, EGFR overexpression; p53, p53R175H. Scale bar, 50 μm. *, P< 0.05 vs. IWR-exo (control agent), n=6. Arrow heads indicate Ki-67 positive cells.

Figure 9.

Wnt inhibition does not affect cyclin D1 expression in the invasive fronts. Cell lines with indicated genotypes expressing DNMAML1 or GFP (control) were grown in OTC in the presence or absence (untreated) of either 10 μM IWR-endo (Wnt inhibitor) or 10 μM IWR-exo (control agent) and subjected to IHC for cyclin D1 (A and B) to determine compartment-specific cyclin D1 LI (C) as well as the impact of Wnt inhibition upon cyclin D1 LI within the invasive nests (D). EGFR, EGFR overexpression; p53, p53R175H. Scale bar, 50 μm. *, P< 0.01 vs. epithelial compartment, n=6; ns, vs. IWR-exo (control agent), n=6. D1, cyclin D1. Arrow heads indicate cyclin D1 positive cells.

4-NQO induces invasive ESCC with Wnt activation in mice carrying DNMAML1 targeted to the squamous epithelia

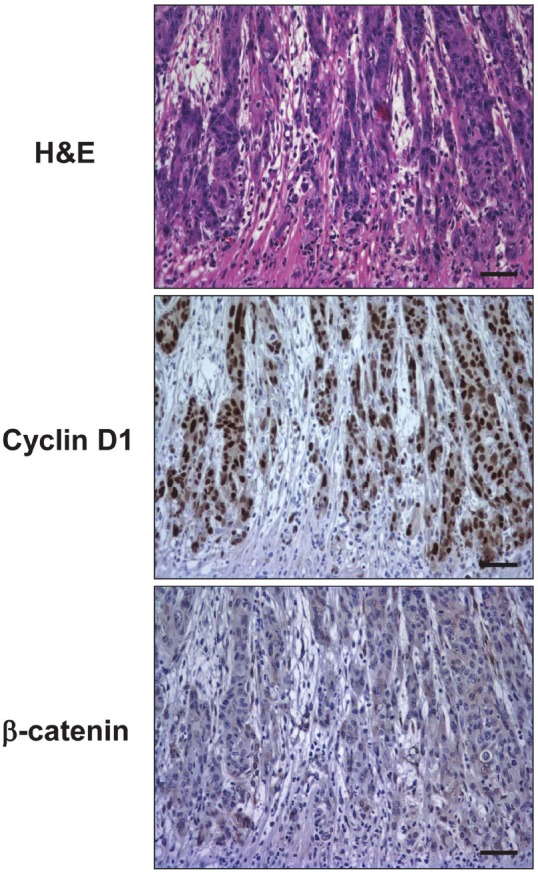

To delineate how Notch inhibition may impact upon carcinogenesis in mice, DNMAML1 was targeted to the oral and esophageal squamous epithelia as described previously [18]. Mice expressing DNMAML1 and control littermates were subjected to 4-NQO administration, which was initially planned for 8 weeks as done in wild-type mice [43]. All control mice tolerated 4-NQO treatment well. Unexpectedly, 4-NQO-treated DNMAML1 mice suffered from weight loss and severe dehydration, which may be associated with inflammation observed in the tongue (Table 1 and data not shown), preventing mice from drinking. 4-NQO treatment was suspended at day 18 for all mice since 8 out of 9 (89%) 4-NQO-treated DNMAML1 mice were found dead or euthanized during 4-NQO administration or within a week after 4-NQO withdrawal. Histology was available for 4 euthanized mice, all of which (100%) displayed squamous dysplasia in the tongue despite a short period of 4-NQO administration (Table 2 and data not shown). Three out of four 4-NQO-treated DNMAML1 mice (75%) exhibited esophageal squamous dysplasia. One of the 4-NQO-treated DNMAML1 mice recovered from dehydration after 4-NQO withdrawal and was sacrificed 8 weeks later along with control littermates. Histology of this mouse revealed highly invasive ESCC containing spindle-shaped tumor cells reminiscent of EMT (Figure 10), in addition to dysplasia in the tongue and esophagus. IHC documented cyclin D1 overexpression and β-catenin cytoplasmic localization in the invasive fronts of ESCC lesions (Figure 10). Amongst 4-NQO-treated control mice (without DNMAML1), four out of 34 (12%) developed squamous dysplasia in the tongue (n=1) or the esophagus (n=3), but not cancer. These results suggest that Notch inhibition by DNMAML1 promoted 4-NQO-mediated oral and esophageal carcinogenesis. Moreover, Notch-independent cyclin D1 upregulation and Wnt activation may contribute to invasive growth of ESCC in mice.

Table 1.

4-NQO and DNMAML1 induce inflammation in mice.

| genotype | 4NQO treatment | n | inflammation | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| skin | tongue | esophagus | forestomach | |||

| DNMAML1 (-) | (-) | 4 | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| (+) | 12 | 1 (8.3%) | 3 (25%) | 4 (33%) | 1 (8.3%) | |

|

| ||||||

| DNMAML1 (+) | (-) | 5 | 5 (100%)* | 0 (0%) | 1 (20%) | 0 (0%) |

| (+) | 5a | 5 (100%)* | 4 (80%)** | 1 (20%) | 1 (20%) | |

Histology was available for 5 euthanized mice only due to early death in 8 mice out of 9.

Note that DNMAML1 caused skin inflammation in mice with or without 4-NQO treatment [*, P< 0.01 vs. DNMAML1 (-)]. 4-NQO induced tongue inflammation significantly more in the presence of DNMAML1 [**, P< 0.05 vs. DNMAML (+) and 4-NQO (-)].

P< 0.01 vs. DNMAML1 (-)

P< 0.05 vs. DNMAML (+) and 4-NQO (-)

Table 2.

4-NQO and DNMAML1 induce dysplasia in mice

| genotype | 4NQO treatment | n | dysplasia | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| skin | tongue | esophagus | forestomach | |||

| DNMAML1 (-) | (-) | 4 | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| (+) | 12 | 1 (8.3%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (17%) | 0 (0%) | |

|

| ||||||

| DNMAML1 (+) | (-) | 5 | 4 (80%)* | 2 (40%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| (+) | 5a | 3 (60%)* | 5 (100%)# | 3 (60%)b | 0 (0%) | |

Histology was available for 5 euthanized mice only due to early death in 8 mice out of 9;

One of 3 mice with esophageal dysplasia had ESCC in the lower esophagus.

Note that DNMAML1 caused skin dysplasia in mice with or without 4-NQO treatment [*, P< 0.01 vs. DNMAML1 (-)]. 4-NQO induced tongue dysplasia significantly more in the presence of DNMAML1 [#, P< 0.05 vs. DNMAML (+) and 4-NQO (-)]

P< 0.01 vs. DNMAML1 (-)

P< 0.05 vs. DNMAML (+) and 4-NQO (-)

Figure 10.

Cyclin D1 overexpression and Wnt activation in the invasive fronts of primary ESCC developed in a DNMAML1 mouse. Primary ESCC developed in the lower esophagus of a 4-NQO-treated DNMAML1 mouse was subjected to H&E staining, IHC for cyclin D1 and β-catenin.

Cyclin D1 is overexpressed in invasive lesions of primary ESCC with cytoplasmic stabilization of β-catenin

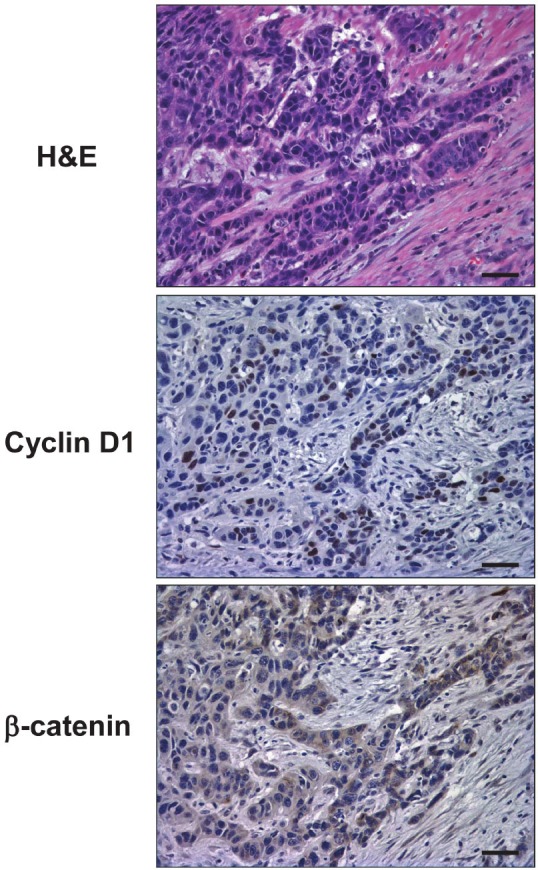

Finally, we performed IHC for cyclin D1 and β-catenin on primary ESCC tissue samples (n=12). Cyclin D1 was overexpressed in 9 out of 12 human ESCC samples (75%) in agreement with our previous observations [44]. Cyclin D1 was not expressed constitutively as cyclin D1 positive tumor cells were typically found in the invasive fronts (Figure 11) where tumors cells spindle-are often poorly-differentiated, displaying shaped morphology reminiscent of EMT [37]. β-catenin was expressed on the cell membrane of well-differentiated ESCC cells and normal keratinocytes within the adjacent squamous epithelia (data not shown). By contrast, in 10 out of 12 cases (83%), invasive ESCC cells expressed β-catenin in the cytoplasm (Figure 11) with occasional nuclear localization (data not shown), suggesting activation of the Wnt pathway in the invasive fronts. These findings implicate the roles of the tumor microenvironment in regulation of cyclin D1 expression and Wnt signaling.

Figure 11.

Cyclin D1 overexpression and Wnt activation in the invasive fronts of primary ESCC in human. Serial sections from a representative primary ESCC tumor were subjected to H&E staining, IHC for cyclin D1 as well as β-catenin.

Discussion

Notch inhibition reveals differential regulation of proliferation and differentiation between squamous epithelial cells and invasive cells within the stroma

This study aimed at analyzing the complex interplay between cyclin D1, EGFR and mutant p53 during the development and progression of ESCC. In OTC, the Notch and Wnt pathways were interrogated using genetic and pharmacological inhibitors, respectively. Our foremost novel finding is that cell proliferation may be regulated differentially between the squamous-epithelial compartment and the underlying stroma. Within the squamous epithelium, non-transformed and transformed esophageal cells were found to depend upon canonical Notch signaling to undergo squamous-cell differentiation (Figure 5). By contrast, transformed cells exhibited invasive growth in a Notch-independent manner that is enhanced by DNMAML1 (Figures 2 and 3), and involves cyclin D1 and Wnt signaling (Figures 6, 7, 8 and 9). Aberrant expression of cyclin D1 and β-catenin stabilization were observed in the invasive fronts of primary human ESCC (Figure 11) as well as mouse ESCC induced by 4-NQO in the presence of DNMAML1 (Figure 10), recapitulating the findings in the OTC model (Figure 1-5).

Our data also showed that cyclin D1 overexpression stimulates cell proliferation within the squamous epithelium (Figures 2, 3 and 4). As a mitogenic sensor and a regulator in cell cycle control [45], cyclin D1 is often overexpressed in ESCC via gene amplification or EGFR-mediated transcriptional activation [32,44] and is associated with lymphatic invasion and lymph node metastasis [46], culminating in poor prognosis [47]. Although Notch may transcriptionally activate cyclin D1 [33,34], our data with DNMAML1 indicate that canonical Notch signaling may be dispensable for cyclin D1 induction in invasive ESCC cells.

Notch inhibition by DNMAML1 may impair epithelial integrity to facilitate oral-esophageal squamous-cell carcinogenesis

We confirmed that Notch inhibition by DNMAML1 is not sufficient for non-transformed cells (e.g. EGFR overexpression alone and p53R175H alone) to undergo robust invasion. Moreover, potential Notch inhibitory effects by EGFR overexpression [29] or impaired p53-mediated transactivation of Notch1 [22,28] did not appear to have a significant negative impact upon squamous-cell differentiation in the absence of DNMAML1 (Figure 5). By contrast, malignant transformation by concurrent EGFR and p53R175H expression appeared to be necessary and sufficient for invasive growth, although DNMAML1 enhanced both cell proliferation and invasion in this context. This agrees with our previous observations that transformed esophageal cells underwent EMT during invasive growth when Notch-dependent squamous-cell differentiation was suppressed [15,37].

We demonstrated for the first time that Notch inhibition promotes oral and esophageal carcinogenesis in a genetically engineered mouse model. Notch may act as a tumor suppressor in the skin by maintaining the skin-barrier functions to prevent emergence of a tumorpromoting inflammatory microenvironment [22-24,30,48,49]. Consistent with such a premise, we observed induction of severe dehydration and early death in response to 4-NQO administration in most mice expressing DNMAML1 under CK14 promoter-driven Cre, causing substantive inflammation in the skin and the tongue (Table 1). Given the fact that 4-NQO is an ultraviolet mimetic agent [50] and that DNMAML1 affects esophageal squamous cell differentiation [18], 4-NQO and DNMAML1 may cooperate to promote oral-esophageal carcinogenesis by impairing epithelial barrier functions to generate an inflammatory microenvironment. Since cutaneous inflammation may have contributed to 4-NQO-induced dehydration, preventing us to complete scheduled 4-NQO administration, future studies should aim at targeting DNMAML1 specifically to the oral-esophageal squamous epithelia [51] to minimize skin-related phenotypes.

Wnt signaling and cyclin D1 may be activated in the invasive fronts of ESCC

Our data suggest that Wnt signaling may facilitate ESCC progression. IWR-endo antagonizes Wnt signaling by stabilizing Axin [39] and decreasing the cytoplasmic pool of β-catenin as well as cell proliferation and invasion (Figures 6, 7 and 8). Although somatic mutations have not been found in the Wnt pathway, Wnt activation has been implicated in a small subset (8-15%) of primary ESCC [52,53]. Axin is downregulated during invasive growth of primary ESCC and inversely correlated with depth of invasion, lymphatic invasion and lymph node metastasis [54]. Wnt inhibitory factor 1 is frequently silenced epigenetically in ESCC [55]. Wnt1 can activate the Wnt pathway in ESCC cells [56]. Cancer-associated fibroblasts also secrete Wnt2 to promote esophageal cancer progression [57].

Cyclin D1 is an essential direct target gene for the Wnt pathway [58,59]. Moreover, Wnt1 and Wnt5a can transactivate EGFR to induce cyclin D1 expression [60]. Wnt activation and cyclin D1 overexpression were observed in SCC developed in the mouse epidermis with DNMAML1 targeted by the SM22α promoter at midgestation [24]; however, Wnt inhibition did not reduce cyclin D1 expression (Figure 9), implying additional regulatory mechanisms for cyclin D1 expression. Amongst possible explanations are the non-soluble factors such as collagen and fibronectin in the extracellular matrix that are known to activate cyclin D1 via focal adhesion kinase-mediated pathway [61].

In sum, we have validated OTC as an excellent in vitro model system that can recapitulate many pathological characteristics of ESCC observed in both genetic mouse models and human patients. Notch inhibition in OTC and a genetic mouse model not only vindicated the tumor suppressor roles of Notch signaling, but also revealed Notch-independent induction of cyclin D1 and activation of Wnt signaling in the invasive fronts where the tumor microenvironment may influence the gene expression and cell signaling in transformed human esophageal cells.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported in part by P01CA098101 (HN, SN, KW, MN, SK, HK, SO, MH, JAD, PAG, AJK), NIH Grants R01DK077005 (to HN), K26 RR032714 (to HN), University of Pennsylvania, Abramson Cancer Center Pilot Project Grant (to HN), University of Pennsylvania University Research Foundation Award (to HN), P30-DK050306 (to SC and HS), AGA-Stuart Brotman Student Research Fellowship Award (to SC), Japan Society for the Promotion of Science Grant-in-Aid for Young Scientists B-21790382 (to SN), and the NIH/NIDDK Center for Molecular Studies in Digestive and Liver Diseases ( P30-DK050306) and its core facilities (Molecular Pathology and Imaging, Cell Culture, Molecular Biology/Gene Expression). We are appreciative of discussions with Dr. Motomi Enomoto-Iwamoto (Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia) and the lab of Dr. Anil K Rustgi and his editorial help.

References

- 1.Enzinger PC, Mayer RJ. Esophageal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:2241–2252. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra035010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kleinberg L, Gibson MK, Forastiere AA. Chemoradiotherapy for localized esophageal cancer: regimen selection and molecular mechanisms of radiosensitization. Nat Clin Pract Oncol. 2007;4:282–294. doi: 10.1038/ncponc0796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Montgomery E, Field JK, Boffetta P, Daigo Y, Shimizu M, Shimoda T. Squamous cell carcinoma of the oesophagus. In: Bosman FT, Carneiro F, Hruban RH, Theise ND, editors. WHO Classification of Tumours of the Digestive System. Lyon: IARC Press; 2010. pp. 9–30. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nakagawa H, Katzka D, Rustgi AK. Biology of esophageal cancer. In: Rustgi AK, editor. Gastrointestinal Cancers. London: Elsevier; 2003. pp. 241–251. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stairs DB, Bayne LJ, Rhoades B, Vega ME, Waldron TJ, Kalabis J, Klein-Szanto A, Lee JS, Katz JP, Diehl JA, Reynolds AB, Vonderheide RH, Rustgi AK. Deletion of p120-catenin results in a tumor microenvironment with inflammation and cancer that establishes it as a tumor suppressor gene. Cancer Cell. 2011;19:470–483. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2011.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Itakura Y, Sasano H, Shiga C, Furukawa Y, Shiga K, Mori S, Nagura H. Epidermal growth factor receptor overexpression in esophageal carcinoma. An immunohistochemical study correlated with clinicopathologic findings and DNA amplification. Cancer. 1994;74:795–804. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19940801)74:3<795::aid-cncr2820740303>3.0.co;2-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Volant A, Nousbaum JB, Giroux MA, Roue-Quintin I, Metges JP, Ferec C, Gouerou H, Robaszkiewicz M. p53 protein accumulation in oesophageal squamous cell carcinomas and precancerous lesions. J Clin Pathol. 1995;48:531–534. doi: 10.1136/jcp.48.6.531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jaskiewicz K, De Groot KM. p53 gene mutants expression, cellular proliferation and differentiation in oesophageal carcinoma and non-cancerous epithelium. Anticancer Res. 1994;14:137–140. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shamma A, Doki Y, Shiozaki H, Tsujinaka T, Yamamoto M, Inoue M, Yano M, Monden M. Cyclin D1 overexpression in esophageal dysplasia: a possible biomarker for carcinogenesis of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Int J Oncol. 2000;16:261–266. doi: 10.3892/ijo.16.2.261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Harada H, Nakagawa H, Oyama K, Takaoka M, Andl CD, Jacobmeier B, von Werder A, Enders GH, Opitz OG, Rustgi AK. Telomerase induces immortalization of human esophageal keratinocytes without p16INK4a inactivation. Mol Cancer Res. 2003;1:729–738. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ohashi S, Natsuizaka M, Wong GS, Michaylira CZ, Grugan KD, Stairs DB, Kalabis J, Vega ME, Kalman RA, Nakagawa M, Klein-Szanto AJ, Herlyn M, Diehl JA, Rustgi AK, Nakagawa H. Epidermal growth factor receptor and mutant p53 expand an esophageal cellular subpopulation capable of epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition through ZEB transcription factors. Cancer Res. 2010;70:4174–4184. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-4614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Okawa T, Michaylira CZ, Kalabis J, Stairs DB, Nakagawa H, Andl CD, Johnstone CN, Klein-Szanto AJ, El-Deiry WS, Cukierman E, Herlyn M, Rustgi AK. The functional interplay between EGFR overexpression, hTERT activation, and p53 mutation in esophageal epithelial cells with activation of stromal fibroblasts induces tumor development, invasion, and differentiation. Genes Dev. 2007;21:2788–2803. doi: 10.1101/gad.1544507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kalabis J, Wong GS, Vega ME, Natsuizaka M, Robertson ES, Herlyn M, Nakagawa H, Rustgi A. Isolation and characterization of mouse and human esophageal epithelial cells in 3D organotypic culture. Nature Protocol. 2012;7:235–246. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2011.437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Michaylira CZ, Wong GS, Miller CG, Gutierrez CM, Nakagawa H, Hammond R, Klein-Szanto AJ, Lee JS, Kim SB, Herlyn M, Diehl JA, Gimotty P, Rustgi AK. Periostin, a cell adhesion molecule, facilitates invasion in the tumor microenvironment and annotates a novel tumor-invasive signature in esophageal cancer. Cancer Res. 2010;70:5281–5292. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-0704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Natsuizaka M, Ohashi S, Wong GS, Ahmadi A, Kalman RA, Budo D, Klein-Szanto AJ, Herlyn M, Diehl JA, Nakagawa H. Insulin-like growth factor-binding protein-3 promotes transforming growth factor-{beta}1-mediated epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition and motility in transformed human esophageal cells. Carcinogenesis. 2010;31:1344–1353. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgq108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rangarajan A, Talora C, Okuyama R, Nicolas M, Mammucari C, Oh H, Aster JC, Krishna S, Metzger D, Chambon P, Miele L, Aguet M, Radtke F, Dotto GP. Notch signaling is a direct determinant of keratinocyte growth arrest and entry into differentiation. EMBO J. 2001;20:3427–3436. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.13.3427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Blanpain C, Lowry WE, Pasolli HA, Fuchs E. Canonical notch signaling functions as a commitment switch in the epidermal lineage. Genes Dev. 2006;20:3022–3035. doi: 10.1101/gad.1477606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ohashi S, Natsuizaka M, Yashiro-Ohtani Y, Kalman RA, Nakagawa M, Wu L, Klein-Szanto AJ, Herlyn M, Diehl JA, Katz JP, Pear WS, Seykora JT, Nakagawa H. NOTCH1 and NOTCH3 coordinate esophageal squamous differentiation through a CSL-dependent transcriptional network. Gastroenterology. 2010;139:2113–2123. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.08.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McElhinny AS, Li JL, Wu L. Mastermind-like transcriptional co-activators: emerging roles in regulating cross talk among multiple signaling pathways. Oncogene. 2008;27:5138–5147. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ohashi S, Natsuizaka M, Naganuma S, Kimura S, Itoh H, Kalman RA, Nakagawa M, Darling DS, Basu D, Gimotty PA, Klein-Szanto AJ, Diehl JA, Herlyn M, Nakagawa H. A NOTCH3-mediated squamous cell differentiation program limits expansion of EMT competent cells that express the ZEB transcription factors. Cancer Res. 2011;71:6836–6847. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-0846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Demehri S, Turkoz A, Kopan R. Epidermal Notch1 loss promotes skin tumorigenesis by impacting the stromal microenvironment. Cancer Cell. 2009;16:55–66. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.05.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lefort K, Mandinova A, Ostano P, Kolev V, Calpini V, Kolfschoten I, Devgan V, Lieb J, Raffoul W, Hohl D, Neel V, Garlick J, Chiorino G, Dotto GP. Notch1 is a p53 target gene involved in human keratinocyte tumor suppression through negative regulation of ROCK1/2 and MRCKalpha kinases. Genes Dev. 2007;21:562–577. doi: 10.1101/gad.1484707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nicolas M, Wolfer A, Raj K, Kummer JA, Mill P, van Noort M, Hui CC, Clevers H, Dotto GP, Radtke F. Notch1 functions as a tumor suppressor in mouse skin. Nat Genet. 2003;33:416–421. doi: 10.1038/ng1099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Proweller A, Tu L, Lepore JJ, Cheng L, Lu MM, Seykora J, Millar SE, Pear WS, Parmacek MS. Impaired notch signaling promotes de novo squamous cell carcinoma formation. Cancer Res. 2006;66:7438–7444. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-0793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Agrawal N, Frederick MJ, Pickering CR, Bettegowda C, Chang K, Li RJ, Fakhry C, Xie TX, Zhang J, Wang J, Zhang N, El-Naggar AK, Jasser SA, Weinstein JN, Trevino L, Drummond JA, Muzny DM, Wu Y, Wood LD, Hruban RH, Westra WH, Koch WM, Califano JA, Gibbs RA, Sidransky D, Vogelstein B, Velculescu VE, Papadopoulos N, Wheeler DA, Kinzler KW, Myers JN. Exome sequencing of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma reveals inactivating mutations in NOTCH1. Science. 2011;333:1154–1157. doi: 10.1126/science.1206923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stransky N, Egloff AM, Tward AD, Kostic AD, Cibulskis K, Sivachenko A, Kryukov GV, Lawrence MS, Sougnez C, McKenna A, Shefler E, Ramos AH, Stojanov P, Carter SL, Voet D, Cortes ML, Auclair D, Berger MF, Saksena G, Guiducci C, Onofrio RC, Parkin M, Romkes M, Weissfeld JL, Seethala RR, Wang L, Rangel-Escareno C, Fernandez-Lopez JC, Hidalgo-Miranda A, Melendez-Zajgla J, Winckler W, Ardlie K, Gabriel SB, Meyerson M, Lander ES, Getz G, Golub TR, Garraway LA, Grandis JR. The mutational landscape of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Science. 2011;333:1157–1160. doi: 10.1126/science.1208130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang NJ, Sanborn Z, Arnett KL, Bayston LJ, Liao W, Proby CM, Leigh IM, Collisson EA, Gordon PB, Jakkula L, Pennypacker S, Zou Y, Sharma M, North JP, Vemula SS, Mauro TM, Neuhaus IM, Leboit PE, Hur JS, Park K, Huh N, Kwok PY, Arron ST, Massion PP, Bale AE, Haussler D, Cleaver JE, Gray JW, Spellman PT, South AP, Aster JC, Blacklow SC, Cho RJ. Loss-of-function mutations in Notch receptors in cutaneous and lung squamous cell carcinoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:17761–17766. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1114669108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yugawa T, Handa K, Narisawa-Saito M, Ohno S, Fujita M, Kiyono T. Regulation of Notch1 gene expression by p53 in epithelial cells. Molecular and cellular biology. 2007;27:3732–3742. doi: 10.1128/MCB.02119-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kolev V, Mandinova A, Guinea-Viniegra J, Hu B, Lefort K, Lambertini C, Neel V, Dummer R, Wagner EF, Dotto GP. EGFR signalling as a negative regulator of Notch1 gene transcription and function in proliferating keratinocytes and cancer. Nat Cell Biol. 2008;10:902–911. doi: 10.1038/ncb1750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang YW, Wang R, Liu Q, Zhang H, Liao FF, Xu H. Presenilin/gamma-secretase-dependent processing of beta-amyloid precursor protein regulates EGF receptor expression. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:10613–10618. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0703903104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li T, Wen H, Brayton C, Das P, Smithson LA, Fauq A, Fan X, Crain BJ, Price DL, Golde TE, Eberhart CG, Wong PC. Epidermal growth factor receptor and notch pathways participate in the tumor suppressor function of gamma-secretase. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2007;282:32264–32273. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M703649200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yan YX, Nakagawa H, Lee MH, Rustgi AK. Transforming growth factor-alpha enhances cyclin D1 transcription through the binding of early growth response protein to a cis-regulatory element in the cyclin D1 promoter. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:33181–33190. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.52.33181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ronchini C, Capobianco AJ. Induction of cyclin D1 transcription and CDK2 activity by Notch(ic): implication for cell cycle disruption in transformation by Notch(ic) Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21:5925–5934. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.17.5925-5934.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cohen B, Shimizu M, Izrailit J, Ng NF, Buchman Y, Pan JG, Dering J, Reedijk M. Cyclin D1 is a direct target of JAG1-mediated Notch signaling in breast cancer. Breast cancer research and treatment. 2010;123:113–124. doi: 10.1007/s10549-009-0621-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lee JJ, Natsuizaka M, Ohashi S, Wong GS, Takaoka M, Michaylira CZ, Budo D, Tobias JW, Kanai M, Shirakawa Y, Naomoto Y, Klein-Szanto AJ, Haase VH, Nakagawa H. Hypoxia activates the cyclooxygenase-2-prostaglandin E synthase axis. Carcinogenesis. 2010;31:427–434. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgp326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Andl CD, Mizushima T, Nakagawa H, Oyama K, Harada H, Chruma K, Herlyn M, Rustgi AK. Epidermal growth factor receptor mediates increased cell proliferation, migration, and aggregation in esophageal keratinocytes in vitro and in vivo. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:1824–1830. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M209148200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ohashi S, Natsuizaka M, Naganuma S, Kagawa S, Kimura S, Itoh H, Kalman RA, Nakagawa M, Darling DS, Basu D, Gimotty PA, Klein-Szanto AJ, Diehl JA, Herlyn M, Nakagawa H. A NOTCH3-mediated squamous cell differentiation program limits expansion of EMT-competent cells that express the ZEB transcription factors. Cancer Research. 2011;71:6836–6847. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-0846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kalabis J, Wong GS, Vega ME, Natsuizaka M, Robertson ES, Herlyn M, Nakagawa H, Rustgi AK. Isolation and characterization of mouse and human esophageal epithelial cells in 3D organotypic culture. Nature protocols. 2012;7:235–246. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2011.437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chen B, Dodge ME, Tang W, Lu J, Ma Z, Fan CW, Wei S, Hao W, Kilgore J, Williams NS, Roth MG, Amatruda JF, Chen C, Lum L. Small molecule-mediated disruption of Wnt-dependent signaling in tissue regeneration and cancer. Nature chemical biology. 2009;5:100–107. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hiyama H, Iavarone A, LaBaer J, Reeves SA. Regulated ectopic expression of cyclin D1 induces transcriptional activation of the cdk inhibitor p21 gene without altering cell cycle progression. Oncogene. 1997;14:2533–2542. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1201080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tu L, Fang TC, Artis D, Shestova O, Pross SE, Maillard I, Pear WS. Notch signaling is an important regulator of type 2 immunity. J Exp Med. 2005;202:1037–1042. doi: 10.1084/jem.20050923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vasioukhin V, Degenstein L, Wise B, Fuchs E. The magical touch: genome targeting in epidermal stem cells induced by tamoxifen application to mouse skin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:8551–8556. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.15.8551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tang XH, Knudsen B, Bemis D, Tickoo S, Gudas LJ. Oral cavity and esophageal carcinogenesis modeled in carcinogen-treated mice. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:301–313. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-0999-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nakagawa H, Zukerberg L, Togawa K, Meltzer SJ, Nishihara T, Rustgi AK. Human cyclin D1 oncogene and esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer. 1995;76:541–549. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19950815)76:4<541::aid-cncr2820760402>3.0.co;2-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kim JK, Diehl JA. Nuclear cyclin D1: an oncogenic driver in human cancer. Journal of cellular physiology. 2009;220:292–296. doi: 10.1002/jcp.21791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nagasawa S, Onda M, Sasajima K, Makino H, Yamashita K, Takubo K, Miyashita M. Cyclin D1 overexpression as a prognostic factor in patients with esophageal carcinoma. Journal of surgical oncology. 2001;78:208–214. doi: 10.1002/jso.1152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhao J, Li L, Wei S, Gao Y, Chen Y, Wang G, Wu Z. Clinicopathological and prognostic role of cyclin D1 in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma: a meta-analysis. Diseases of the esophagus: official journal of the International Society for Diseases of the Esophagus. I.S.D.E. 2011 doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2050.2011.01278.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Li T, Wen H, Brayton C, Laird FM, Ma G, Peng S, Placanica L, Wu TC, Crain BJ, Price DL, Eberhart CG, Wong PC. Moderate reduction of gamma-secretase attenuates amyloid burden and limits mechanism-based liabilities. J Neurosci. 2007;27:10849–10859. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2152-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pan Y, Lin MH, Tian X, Cheng HT, Gridley T, Shen J, Kopan R. gamma-secretase functions through Notch signaling to maintain skin appendages but is not required for their patterning or initial morphogenesis. Dev Cell. 2004;7:731–743. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2004.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Snyderwine EG, Bohr VA. Gene- and strand-specific damage and repair in Chinese hamster ovary cells treated with 4-nitroquinoline 1-oxide. Cancer Research. 1992;52:4183–4189. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Nakagawa H, Inomoto T, Rustgi AK. A CACCC box-like cis-regulatory element of the Epstein-Barr virus ED-L2 promoter interacts with a novel transcriptional factor in tissue-specific squamous epithelia. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:16688–16699. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.26.16688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kudo J, Nishiwaki T, Haruki N, Ishiguro H, Shibata Y, Terashita Y, Sugiura H, Shinoda N, Kimura M, Kuwabara Y, Fujii Y. Aberrant nuclear localization of beta-catenin without genetic alterations in beta-catenin or Axin genes in esophageal cancer. World journal of surgical oncology. 2007;5:21. doi: 10.1186/1477-7819-5-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Salahshor S, Naidoo R, Serra S, Shih W, Tsao MS, Chetty R, Woodgett JR. Frequent accumulation of nuclear E-cadherin and alterations in the Wnt signaling pathway in esophageal squamous cell carcinomas. Modern pathology: an official journal of the United States and Canadian Academy of Pathology Inc. 2008;21:271–281. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3800990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Nakajima M, Fukuchi M, Miyazaki T, Masuda N, Kato H, Kuwano H. Reduced expression of Axin correlates with tumour progression of oesophageal squamous cell carcinoma. British journal of cancer. 2003;88:1734–1739. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6600941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chan SL, Cui Y, van Hasselt A, Li H, Srivastava G, Jin H, Ng KM, Wang Y, Lee KY, Tsao GS, Zhong S, Robertson KD, Rha SY, Chan AT, Tao Q. The tumor suppressor Wnt inhibitory factor 1 is frequently methylated in nasopharyngeal and esophageal carcinomas. Laboratory investigation; a journal of technical methods and pathology. 2007;87:644–650. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3700547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mizushima T, Nakagawa H, Kamberov YG, Wilder EL, Klein PS, Rustgi AK. Wnt-1 but not epidermal growth factor induces beta-catenin/T-cell factor-dependent transcription in esophageal cancer cells. Cancer Research. 2002;62:277–282. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Fu L, Zhang C, Zhang LY, Dong SS, Lu LH, Chen J, Dai Y, Li Y, Kong KL, Kwong DL, Guan XY. Wnt2 secreted by tumour fibroblasts promotes tumour progression in oesophageal cancer by activation of the Wnt/beta-catenin signalling pathway. Gut. 2011;60:1635–1643. doi: 10.1136/gut.2011.241638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Shtutman M, Zhurinsky J, Simcha I, Albanese C, D'Amico M, Pestell R, Ben-Ze'ev A. The cyclin D1 gene is a target of the beta-catenin/LEF-1 pathway. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1999;96:5522–5527. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.10.5522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Tetsu O, McCormick F. Beta-catenin regulates expression of cyclin D1 in colon carcinoma cells. Nature. 1999;398:422–426. doi: 10.1038/18884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Civenni G, Holbro T, Hynes NE. Wnt1 and Wnt5a induce cyclin D1 expression through ErbB1 transactivation in HC11 mammary epithelial cells. EMBO reports. 2003;4:166–171. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.embor735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Klein EA, Assoian RK. Transcriptional regulation of the cyclin D1 gene at a glance. Journal of cell science. 2008;121:3853–3857. doi: 10.1242/jcs.039131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]