Abstract

Background

Cognitive impairment without dementia (CIND) and acute myocardial infarction (AMI) are prevalent in older adults; however, the association of CIND with outcomes after AMI is unknown.

Methods

We used a multicenter registry to study 772 patients ≥65 years with AMI, enrolled between April 2005 and December 2008, who underwent cognitive function assessment with the Telephone Interview for Cognitive Status-modified (TICS-m) 1 month after AMI. Patients were categorized by cognitive status to describe characteristics and in-hospital treatment, including quality of life and survival 1 year after AMI.

Results

Mean age was 73.2±6.3 years; 58.5% were males and 78.2% were white. Normal cognitive function (TICS-m>22) was present in 44.4%; mild CIND (TICS-m 19–22) in 29.8% and moderate/severe CIND (TICS-m <19) in 25.8% of patients. Rates of hypertension (72.6%, 77.4%, 81.9%), cerebrovascular accidents (3.5%, 7.0%, 9.0%), and myocardial infarction (20.1%, 22.2%, 29.6%) were higher in those with lower TICS-m scores (p<0.05 for comparisons). AMI medications were similar by cognitive status; however, CIND was associated with lower cardiac catheterization rates (p=0.002) and cardiac rehabilitation referrals (p<0.001). Patients with moderate/severe CIND had higher risk-adjusted 1 year mortality that was non-statistically significant (adjusted HR 1.97; 95% CI 0.99 – 3.94; p=0.054; referent normal, TICS-m >22). Quality of life across cognitive status was similar at 1 year.

Conclusions

Most older patients surviving AMI have measurable CIND. CIND was associated with less invasive care, less referral and participation in cardiac rehabilitation, and worse risk-adjusted 1 year survival in those with moderate/severe CIND, making it an important condition to consider in optimizing AMI care.

Older adults comprise a substantial and growing proportion of acute myocardial infarction (AMI) patients1. Despite a higher risk of mortality after AMI as compared to younger patients, elderly AMI survivors have been shown to have reduced anginal symptoms and better quality of life in follow-up2. Older adults are also more likely to have age-associated non-cardiac comorbid conditions. Cognitive impairment without dementia (CIND) is one of these common comorbidities estimated to affect one-fifth of older adults,3 with a higher prevalence among those with vascular disease4. CIND is an important source of functional decline and increased health care utilization5. While previous studies have noted worse outcomes in AMI patients with dementia as compared to not having dementia, these findings were difficult to interpret given marked baseline differences, preferences and levels of aggressiveness in medical care between groups6, 7. Unlike dementia, CIND is often subclinical and therefore requires assessement to understand its prevalence and assocition with AMI treatment patterns and outcomes. CIND, even if not immediately obvious to the physician, may impact AMI care, medication adherence, clinical follow-up, and quality of life.

Therefore, in order to understand the relationship of CIND with AMI care and outcomes, we used the Translational Research Investigating Underlying disparities in acute Myocardial infarction Patients’ Health Status (TRIUMPH) prospective registry and its unique age-related substudy (TRIUMPH aging assessment) that provided objective assessment of cognitive function using the Telephone Interview for Cognitive Status-Modified (TICS-m). We used the 1 month post-AMI TICS-m score to evaluate AMI care, as well as quality of life, hospitalizations, and 1 year post-AMI survival.

Methods

Study Protocol and Patients

The TRIUMPH registry is a prospective observational registry of patients with AMI enrolled from 24 US hospitals between April 2005 and December 2008. To be eligible for inclusion, patients were required to have biomarker evidence of myocardial injury and additional evidence supporting the clinical diagnosis of AMI, including prolonged ischemic signs/symptoms (≥20 minutes) and/or electrocardiographic evidence of ST-segment elevation or depression in 2 or more contiguous leads during the initial 24 hours of admission. Patients not presenting initially to an enrolling institution were eligible only if transferred within the first 24 hours of presentation. Exclusion criteria included any of the following: overt dementia precluding consent for participation, prior enrollment in TRIUMPH, inability to communicate in English or Spanish, prisoners, palliative/hospice care, hearing difficulty that would impair telephone contact for follow-up, discharge or death prior to contact with the site study coordinator, or lack of willingness to participate. Patients with AMI in TRIUMPH had medical and procedural therapies performed at the discretion of the treating physician. Institutional Review Board approval was obtained at each participating hospital and informed consent was obtained from all patients for baseline and follow-up assessments. The Translational Research Investigating Underlying Disparities in Acute Mycardial Infarction Pateints’ Health Status (TRIUMPH) study was supported by grant P50 HL077113 from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Specialized Center of Clinically Oriented Research in Cardiac Dysfunction and Disease. The authors are solely responsible for the design and conduct of this study, all study analyses, the drafting and editing of the paper and its final contents.

TRIUMPH Age Substudy (participating patients ≥65 years old)

Data collection was performed by trained personnel through chart abstraction and standardized in-depth interviews, which were conducted at baseline (hospitalization), 1, 6, and 12 months after hospital discharge. Data on medication use was abstracted from the chart and rates of use were representative of the eligible population (i.e., those without contraindications) except for statins and clopidogrel, for which information regarding contraindications was not available. Patients undergoing an in-person assessment at either the 1 month or 6 month interviews had them performed either in-home or in-office by Examination Management Services, Inc (EMSI, Dallas, TX) which also included anthropomorphic measurements and specimen collections for laboratory analysis.

Cognitive assessment was performed using the TICS-m, a 13-item questionnaire that provides an assessment of global cognitive function and may be administered in-person or by telephone8. The TICS-m was modeled after the Mini-Mental State Examination9, 10, and correlation between tests has been reportedly strong (r = 0.94), including good test-retest reliability with the TICS-m8. Scores range from 0–39, with scores <23 indicating cognitive impairment, further subclassified as mild CIND (score of 19–22) or moderate/severe CIND (score of <19)11, 12, the latter correlating well with a Mini-Mental State Examination score ≤2412. Raw scores were adjusted based on level of educational achievement (5 points added for <8 years of education, 2 points added for ≥8–10 years of education, no adjustment of score for 11–12 years of education, and 2 points subtracted for >13 years of education), as previously reported13. The TICS-m was administered in-person or via telephone interview at each follow-up assessment. In this study, we used the 1 month TICS-m score because it likely provided a more accurate reflection of chronic cognitive status. There were 1265 potentially eligible patients ≥65 years old from TRIUMPH that met our eligibility criteria after excluding those who left the hospital against medical advice (n = 4), were discharged to a nursing home (n = 45), were referred to hospice (n = 4), or expired prior to the 1 month follow-up (n = 15).

Outcomes

Hospitalization was self-reported by patients during scheduled in-person or telephone follow-up by TRIUMPH study coordinators at 1 month, 6 month, and 1 year after the index AMI. At each interim follow-up, patients were asked to report on all interval events, which included inpatient hospitalization. Patients reporting a hospitalization had their records requested to confirm the hospitalization. All-cause mortality at 1 year after AMI was assessed through a combination of follow-up interviews and a query of the Social Security Death Masterfile, which was complete in 96.4% of patients. Quality of life was assessed at each follow-up time point using the Medical Outcomes Study short form 12 (SF-12), a 12-item self-administered survey that provides summary scales for overall physical component (PCS) and mental component (MCS) health and well-being14. The PCS and MCS summary scores were created using norm-based methods that standardize the scores to a mean of 50 and a standard deviation of 10, as benchmarked against a 1998 sample of the US population14. Lower scores indicate worse self-perceived health status and have been associated with increased risk of cardiovascular hospitalizations and mortality15–17. Disease-specific quality of life was assessed using the Seattle Angina Questionnaire (SAQ), a reliable and valid self-administered instrument comprised of 5 domains pertaining to how patients pereive their CAD to impact their function, symptoms and quality of life18. Scores range from 0 to 100, with higher scores indicating better quality of life18. The SAQ has previously been established to be valid, reliable, sensitive to changes in clincal status and to be associated with subsequent mortality, acute coronary syndrome hospitalizations and costs of care19–21.

Statistical Analysis

Patient demographics, clinical characteristics, and in-hospital treatments were compared across cognitive status (normal cognitive function, mild CIND, moderate/severe CIND) using ANOVA for continuous variables and chi-square for categorical variables. Multivariable hierarchical linear regression with site as a random effect to account for clustering of patients within hospitals was performed to assess the independent association of cognitive status with MCS, PCS, and SAQ quality of life at 1 year post-AMI. Health status models were adjusted for baseline characteristics, including baseline health status, age, gender, race, coronary artery disease history, hypertension, diabetes, chronic renal disease, congestive heart failure, smoking status, and type of incident myocardial infarction (ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) vs non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI)).

Survival estimates were performed using the Kaplan Meier method and comparisons across groups were assessed using the log rank test. The independent association of cognitive status with 1 year mortality was assessed using multivariable proportional hazards regression stratified by site, adjusting for the same covariates as in the health status models. We tested for non-linear relationship of cognitive score and outcomes using restricted cubic splines with three knots22. For all analyses, tests for statistical significance were two-tailed with an alpha level of 0.05. Analyses were conducted using SAS software, release 9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina) and R version 2.10.123.

Missing Data

Missing covariate data was minimal (missing for 44 (5.6%) patients); most commonly the baseline health status assessment (n=40, 5.2%), assumed to be missing at random, and imputed using a single imputation dataset. Multiple imputation was not warranted in this instance because missing rates were so low. The imputation model consisted of all variables used in the multivariable model in addition to variables useful in imputing missing values, e.g. 1 month and 6 month SF-12 scores were used to impute missing baseline SF-12 scores24. Among patients who completed the 1 month TICS-m and survived to 1 year, follow-up quality of life assessments and information regarding rehospitalization at 1 year were unavailable in 25.0%. To estimate the impact of those patients lost to follow-up, we created a propensity-to-be-missing multivariable logistic regression model to predict the likelihood of partipating in the 1 year health status assessments. We then inversely weighted the propensity to participate in follow-up so that we preferentially weighted the responses of those most like the patients who did not participate in follow-up25.

Results

Cognitive function was objectively assessed using the TICS-m in 772 patients (61% of the potentially eligible cohort). The cognitive screening test was administered in-person to 394 (51.0%) patients and via telephone to 378 (49.0%) patients. The mean age was 73.2 ± 6.3 years (range 65 to 98 years old); 41.5% were women, 78.2% were Caucasian, and 51.8% had an educational level beyond high school. The mean left ventricular ejection fraction was 48.5%±12.7%; 90.5% underwent cardiac catheterization for the index AMI event and 70.3% underwent in-hospital revascularization.

Baseline characteristics, stratified by cognitive status, are presented in Table 1. TICS-m scores were normally distributed with a mean education-adjusted score of 21.8±5.6 (Supplementary Figure 1). There were 343 (44.4%) patients with normal cognitive function, 230 (29.8%) patients with mild CIND and 199 (25.8%) patients with moderate/severe CIND. Age and frailty status were similar across groups, as were measures of 1 month health status. Rates of hypertension (72.6%, 77.4%, 81.9%), cerebrovascular accidents (3.5%, 7.0%, 9.0%), and myocardial infarction (20.1%, 22.2%, 29.6%) were higher in patients with lower TICS-m scores (p<0.05 for comparisons across groups).

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics by Cognitive Status

| Patient Characteristics | Normal (TICS-m >22) | Mild CIND (TICS-m 19–22) | Moderate/Severe CIND (TICS-m <19) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n=343 | n=230 | n=199 | ||

|

Demographics

| ||||

| Age (yrs) | 72.8±6.1 | 73.1±6.5 | 73.9±6.6 | 0.136 |

| Women (%) | 39.1 | 37.8 | 49.7 | 0.021 |

| Caucasian (%) | 84.0 | 80.9 | 65.3 | <0.001 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 28.5±5.1 | 28.5±6.0 | 27.8±6.0 | 0.355 |

| Living alone (%) | 23.0 | 28.4 | 33.8 | 0.023 |

| Education beyond high school (%) | 50.4 | 59.1 | 45.7 | 0.017 |

| Depression index* | 3.8±4.2 | 4.6±5.2 | 4.6±4.7 | 0.062 |

| Gait speed frailty (%)§ | 35.4 | 40.7 | 44.6 | 0.405 |

| SF-12 PCS QOL | 42.3±12.0 | 40.7±12.1 | 40.5±11.7 | 0.165 |

| SF-12 MCS QOL | 53.9±9.2 | 52.5±10.0 | 51.8±10.4 | 0.056 |

| SAQ QOL | 69.1±22.8 | 67.0±22.2 | 67.3±23.5 | 0.491 |

|

| ||||

|

Past Medical History

| ||||

| Hypertension (%) | 72.6 | 77.4 | 81.9 | 0.044 |

| Diabetes (%) | 30.0 | 32.2 | 39.2 | 0.087 |

| Dyslipidemia (%) | 60.1 | 58.7 | 57.8 | 0.866 |

| Peripheral vascular disease (%) | 7.3 | 7.8 | 9.0 | 0.765 |

| Chronic kidney disease (%) | 7.3 | 8.7 | 11.6 | 0.239 |

| Cerebrovascular accident (%) | 3.5 | 7.0 | 9.0 | 0.024 |

| Angina† (%) | 42.1 | 43.5 | 40.7 | 0.845 |

| Myocardial infarction (%) | 20.1 | 22.2 | 29.6 | 0.037 |

| PCI (%) | 20.4 | 20.0 | 26.6 | 0.170 |

| CABG (%) | 17.5 | 20.4 | 20.1 | 0.616 |

| Heart failure (%) | 8.5 | 8.7 | 13.1 | 0.179 |

| Left ventricular ejection fraction (%) | 48.8±12.2 | 48.1±12.1 | 48.6±14.2 | 0.844 |

|

| ||||

|

Presentation Features

| ||||

| Arrival Killip class II-IV (%) | 8.8 | 15.4 | 13.8 | 0.043 |

| Chest pain/discomfort (%) | 68.9 | 71.4 | 69.0 | 0.815 |

| Heart rate ≥100 bpm (%) | 16.9 | 20.4 | 16.7 | 0.487 |

| MI by subtype: | 0.034 | |||

| STEMI (%) | 42.3 | 40.0 | 31.2 | |

| NSTEMI (%) | 57.7 | 60.0 | 68.8 | |

as assessed using the patient health questionnaire (PHQ-9)

defined as walking speed <0.65 m/sec measured 1 month after AMI

obtained from the Seattle Angina Questionnaire at baseline

Abbreviations: CIND, cognitive impairment without dementia; TICS-m, Telephone Interview for Cognitive Status-modified; BMI, body mass index; SF-12, short-form 12; PCS, physical component score; MCS, mental component score; SAQ, Seattle Angina Questionnaire; QOL, quality of life; CVA, cerebrovascular accident; MI, myocardial infarction; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; CABG, coronary artery bypass grafting; bpm, beats per minute; STEMI, ST-elevation myocardial infarction; NSTEMI, Non ST-elevation myocardial infarction

Table 2 lists the rates of use of acute and discharge medical therapies by cognitive status. There were no significant differences in use of these therapies, either acutely or at discharge, by cognitive function. In contrast to the similar use of medications, invasive therapies were used less often in those with CIND, despite presenting with higher Killip class. Rates of cardiac catheterizations were lower in patients with mild CIND (88.3%) and moderate/severe CIND (85.4%) as compared with those with normal cognitive function (95.0%) (p<0.001) (Table 3). There were also significant differences in rates of percutaneous coronary intervention and coronary artery bypass grafting across cogntive status.

Table 2.

Rates of Use of Medications In-hospital and at Discharge by Cognitive Status

| Normal (TICS-m >22) | Mild CIND (TICS-m 19–22) | Moderate/Severe CIND (TICS-m <19) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n=343 | n=230 | n=199 | ||||

|

Medications

| ||||||

| Acute | Discharge | Acute | Discharge | Acute | Discharge | |

| Aspirin (%) | 98.2 | 95.3 | 95.5 | 96.0 | 97.9 | 92.3 |

| Beta blocker (%) | 85.9 | 93.5 | 89.8 | 94.6 | 90.4 | 91.6 |

| ACE inhibitor/ARB (%) | N/A | 77.6 | N/A | 82.5 | N/A | 87.2 |

| Statins*† (%) | 41.7 | 88.6 | 47.0 | 84.8 | 43.7 | 88.4 |

| Clopidogrel* (%) | 67.9 | 77.6 | 63.9 | 68.3 | 58.8 | 74.9 |

No significant differences in medication rates were observed between acute or discharge therapies across groups of cognitive function. ACE inhibitor/ARB is a quality measure at discharge only for patients with left ventricular ejection fraction ≤40%.

does not exclude patients with contraindications

on arrival

Abbreviations: CIND, cognitive impairment without dementia; ACE, angiotensin converting-enzyme; ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker

Table 3.

In-hospital Procedures by Cognitive Status

| Normal (TICS-m >22) | Mild CIND (TICS-m 19–22) | Moderate/Severe CIND (TICS-m <19) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n=343 | n=230 | n=199 | ||

|

In-hospital procedures

| ||||

| Cardiac Catheterization (%) | 95.0 | 88.3 | 85.4 | <0.001 |

| PCI (%) | 66.5 | 59.6 | 54.3 | 0.016 |

| CABG (%) | 9.0 | 14.3 | 7.5 | 0.042 |

| Any revascularization (%) | 75.2 | 70.9 | 61.3 | 0.003 |

Abbreviations: CIND, cognitive impairment wihout dementia; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; CABG, coronary artery bypass grafting

At hospital discharge, there were no differences in referral rates to primary care providers and cardiologists by cognitive status (Table 4). However, patients with CIND were significantly less likely to be referred to or to participate in cardiac rehabilitation after AMI (p <0.001). Patient-reported use of evidence-based medical therapies were similar across cognitive status at 6 and 1 year after AMI.

Table 4.

Discharge and Post-discharge Factors by Cognitive Status

| Normal (TICS-m >22) | Mild CIND (TICS-m 19–22) | Moderate/Severe CIND (TICS-m <19) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n=343 | n=230 | n=199 | ||

| Follow-up appointment with: | ||||

| cardiologist (%) | 84.0 | 80.9 | 81.4 | 0.581 |

| primary care provider† (%) | 33.2 | 33.0 | 35.2 | 0.873 |

|

| ||||

| Use of ≥3 evidence based therapies at 6 months (%)* | 89.2 | 87.3 | 87.0 | 0.748 |

| Use of ≥3 evidence based therapies at 1 year (%)* | 86.9 | 83.2 | 88.3 | 0.464 |

|

| ||||

| Cardiac rehabilitation: | ||||

| Encouraged at 1 month (%) | 62.2 | 60.3 | 40.6 | <0.001 |

| Participation by 6 months (%) | 46.8 | 42.0 | 23.3 | <0.001 |

includes internist, family practitioner, or nurse practitioner.

antiplatelet agent (aspirin or clopidogrel), beta-blocker, statin, angiotensin converting-enzyme inhibitor or angiotensin receptor blocker.

Abbreviations: CIND, cognitive impairment without dementia

Patient Outcomes

After adjustment for multiple sociodemographic and clinical characteristics, there were no statistically significant associations between cognitive status and MCS, PCS or disease-specific quality of life at 1 year (Table 5). These results remained similar in all three sets of sensitivity analyses performed: 1) after accounting for bias from lost to follow-up using a weighted propensity model, 2) after excluding patients that had undergone CABG, or 3) when frailty was included as a model covariate.

Table 5.

Outcomes at 1 year for Mental, Physical, and Disease-Specific Quality of Life and Mortality by Cognitive Status

| SF-12 MCS | SF-12 PCS | Disease-Specific SAQ-QOL | 1 year Mortality Hazard Ratio (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| β estimate (95% CI) | β estimate (95% CI) | β estimate (95% CI) | ||

| Unadjusted (baseline adjusted) | ||||

| Mild Cognitive Impairment | 0.21 (−1.21, 1.64) | −1.84 (−3.72, 0.05) | −1.42 (−4.07, 1.23) | 0.93 (0.40 to 2.16) |

| Moderate/Severe Cognitive Impairment | −1.05 (−2.67, 0.57) | −0.66 (−2.81, 1.49) | 0.22 (−2.70, 3.15) | 2.69 (1.37 to 5.25)† |

| Adjusted model* | ||||

| Mild Cognitive Impairment | 0.19 (−1.26, 1.63) | −1.76 (−3.61, 0.08) | −1.28 (−3.83, 1.28) | 0.81 (0.34 to 1.90) |

| Moderate/Severe Cognitive Impairment | −1.01 (−2.68, 0.67) | 0.21 (−1.93, 2.36) | 0.59 (−2.27, 3.46) | 1.97 (0.99 to 3.94) |

Adjusted for baseline health status, age, gender, race, coronary artery disease history, hypertension, diabetes, chronic renal disease, congestive heart failure, smoking status, and type of incident myocardial infarction (ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) vs non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI)).

Abbreviations: MCS, mental component score; PCS, physical component score; SAQ, Seattle Angina Questionnaire; QOL, quality of life

p<0.05

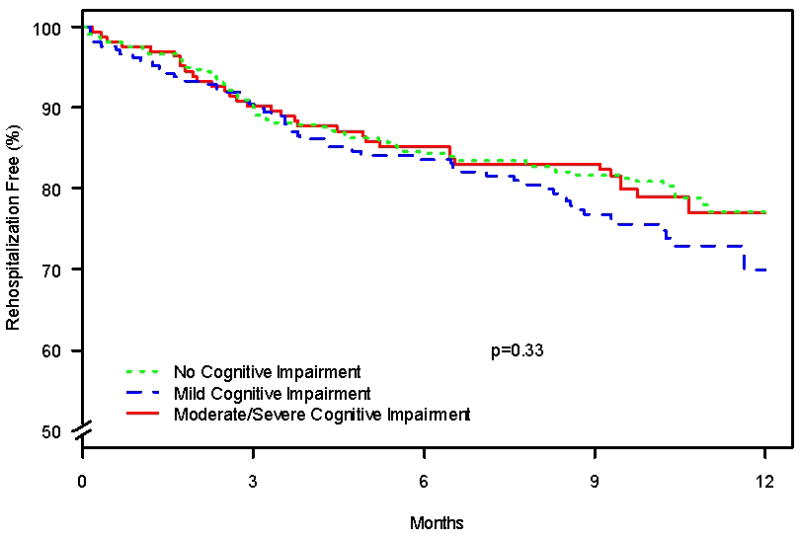

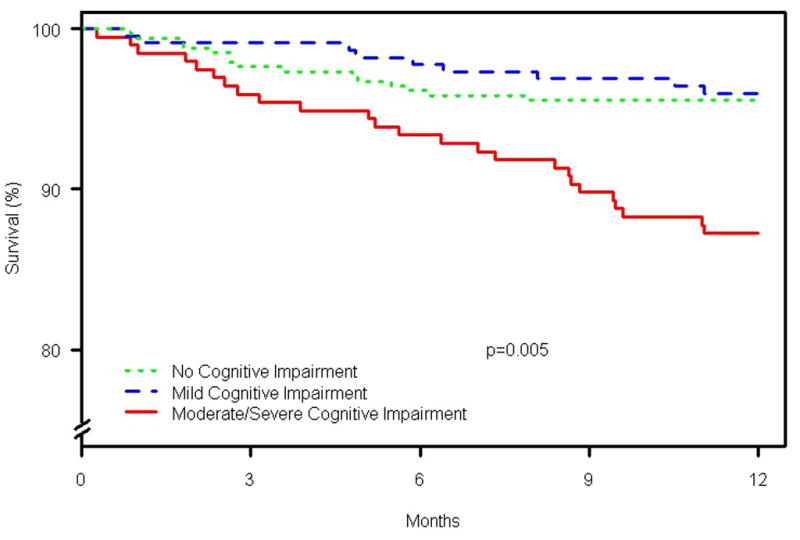

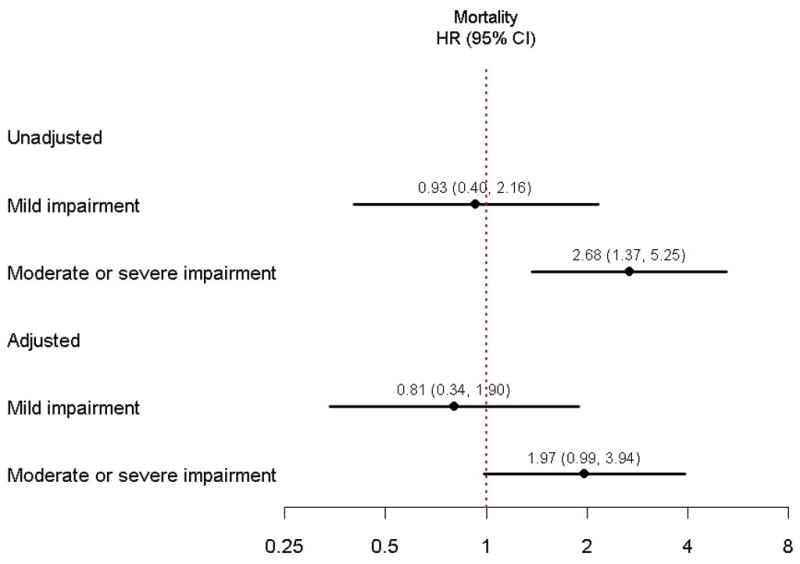

There were 259 hospitalizations after the index AMI. By cognitive status category, the number of patients hospitalized during the study period was 115, 87, and 57 for normal, mild CIND, and moderate/severe CIND, respectively. The all-cause rehospitalization rate as estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method at 1 year after AMI was 25.2%; 23.0% for patients with normal cognitive function, 30.0% in mild CIND, and 23.0% in moderate/severe CIND (p=0.33) (Figure 1). However, when the analysis was restricted to the subgroup of patients that were living alone (n = 210), estimated 1 year rehospitalization rates were 2.7% in patients with normal cognitive function, 9.4% in patients with mild CIND, and 26.2% in patients with moderate/severe CIND (p = <0.001). There were 80 deaths over the study period. By cognitive status category, the number of patients who died was 28, 14, and 38 for normal, mild CIND, and moderate/severe CIND, respectively. Figure 2 shows 1 year survival by cognitive status using Kaplan-Meier estimates. Patients with moderate/severe CIND had a 1 year mortality rate of 12.8%, while those with mild CIND and normal cognitive function had 1 year mortality rates of 4.0% and 4.5%, respectively (p=0.005 by log-rank). Mild CIND was not associated with an increased risk of 1 year mortality in either unadjusted or adjusted analyses. In an unadjusted analysis, as compared to patients with normal cognition, patients with moderate/severe CIND had a 2.7 greater hazard of death (95% confidence interval (CI) 1.37 to 5.25; p=0.004), although lost statistical significance after multivariable adjustment (adjusted HR 1.97; 95% CI 0.99 to 3.94; p=0.054) (Table 5 and Figure 3). Each covariate in the model was tested individually to determine which one may have attenuated the association between moderate/severe CIND and the hazard of mortality. Using this procedure, no specific covariate was responsible, but rather the attenuation was related to the multivariable nature of potential confounders. There was no evidence of non-linearity for cognitive score and mortality (restricted cubic spline p-value = 0.64). Sensitivity analysis excluding patients who underwent CABG did not materially alter findings (adjusted HR for mortality 1.49 for moderate/severe CIND vs. normal cognition; 95% CI 0.73 to 3.06). There was no difference in the association between the method of TICS-m administration (in-person vs. via telephone) and health outcomes.

Figure 1.

Kaplan-Meier estimates of time to any rehospitalization by cognitive status

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier estimates of 1 year survival by cognitive status

Figure 3.

Adjusted hazard ratio of 1 year mortality by cognitive status

Discussion

In this multicenter prospective registry of AMI patients, we observed that more than half of patients age ≥65 years old had measurable CIND and one-quarter had moderate/severe CIND when cognitive status was assessed 1 month after AMI. We observed that patients with CIND received high rates of appropriate discharge medical therapy which were similar to that seen in patients with normal cognitive function; however, CIND patients were less likely to be treated invasively or be referred for cardiac rehabilitation. In addition, although not meeting criteria for statistical significance, our data suggests that moderate/severe CIND is associated with a clinically important increase risk-adjusted mortality at 1 year after AMI. Among those who reported living alone at baseline, moderate/severe CIND patients were also at greater risk of rehospitalization after AMI. Patients with moderate/severe CIND probably represent a group of patients that require greater assistance with medication management, have limitations in performing instrumental activities of daily living, and are at risk for loss of independence.

To our knowledge, this study also represents the first investigation of the prevalence of cognitive impairment, assessed objectively, early after AMI. The prevalence of moderate/severe CIND in our cohort is consistent with prior studies that have estimates ranging from 22% in a community-based cohort to 35% in patients scheduled for surgical coronary revascularization3, 4. Differences in prevalence may be related to the definition of cognitive impairment or the characteristics of the study cohorts, as coronary artery disease and vascular risk factors may be associated with the non-amnestic subtype of CIND26. Our use of the TICS-m as the sole screening test for cognitive function has been used similarly by other investigators27, and our cut-point for moderate/severe CIND has previously demonstrated good correlation with an MMSE score ≤24 and with good interrater agreement (kappa 0.66)12. In addition, TRIUMPH excluded patients with overt dementia and our analysis excluded patients who died prior to the 1 month follow-up assessment. Thus, our finding that one quarter of older adults post-AMI have moderate/severe CIND may underestimate the true prevalence of important CIND in the elderly post-AMI population.

Cognitive Impairment Post AMI

Sloan et al6 examined the impact of dementia, as defined by chart review, on care patterns and outcomes in AMI patients, observing that dementia patients, as compared with those not having a history of dementia, had similar use of in-hospital medications (aspirin and beta blockers) but lower use of cardiac catheterization and revascularization6. Dementia was associated with higher 1 year mortality (relative risk 1.18, 95% CI 1.13 to 1.23), but the association was no longer significant after excluding patients with a do-not-resuscitate order (relative risk 1.01, 95% CI 0.96 to 1.06). That study used data from a time period (1994–1995) preceding the use of primary percutaneous coronary intervention and stenting for AMI and marked differences in baseline characteristics between patients with and without dementia likely influenced decisions regarding invasive management6. Other investigators have shown that nonspecific documentation of cognitive impairment from medical records can provide incremental prediction of mortality in heart failure patients28. Cognitive impairment is often subclinical and infrequently identified in the patient’s medical history29. In our study, baseline characteristics and delivery of acute and chronic medical therapy were generally similar in patients by cogntive status and, therefore, would be less likely to explain the treatment gaps. In addition, in-hospital revascularization rates in our study were 70.3%, including in-hospital rates of percutaneous coronary intervention of 61.3%, reflecting a contemporary cohort of patients with AMI. Thus, our study expands these prior observations by measuring cognition objectively and in describing the association of cognitive function with AMI treatments and outcomes in the modern era of AMI care.

Although cognitively impaired patients may comprise a larger proportion of patients conservatively managed after AMI, prior studies have not evaluated for this association because cognitive status is not routinely collected or measured30. We observed that CIND was associated with lower rates of invasive therapies; however, it seemed paradoxical that patients with CIND had lower rates of referral to and participation in cardiac rehabilitation, as this could particularly benefit those needing additional support. Cardiac rehabilitation improves physical function among revascularized patients and promotes positive behavioral and lifestyle changes31. Beyond improvements in physical function, exercise may be beneficial from a cognitive perspective32, and there is evidence that cardiac rehabilitation may improve outcomes among patients with mild CIND33. Given its potential for both cognitive and functional benefits, post-AMI patients with CIND could derive substantial benefit from cardiac rehabilitation34, 35 and additional studies to test this hypothesis are needed.

Interestingly, cognitive status did not influence quality of life at 1 year. This may be due to differences in perception of expected quality of life or a greater equalization of expected and actual quality of life by patients with moderate/severe CIND. The assessment of quality of life through self-report may be less reliable in patients with cognitive impairment; however, this may be more of a factor in patients with advanced cognitive dysfunction rather than in any individual with cognitive impairment per se36. It is also possible that our study was under-powered to detect these effects or subject to residual confounding. The importance of reduced quality of life and cardiovascular mortality19 underscores continued efforts to examine relationships between cognition, self-perceived quality of life, and outcomes following AMI.

Limitations

The findings of our study should be interpreted within the context of several potential limitations. CIND was assessed 1 month after hospital discharge and may not reflect the state of cognitive faculties at the time of hospitalization for AMI. However, acute illness poses challenges in performing objective assessments of cognitive function, as the specificity of cognitive batteries is reduced and may be confounded by acute confusional states or delirium. Supporting our selection of the 1 month cognitive assessment as a useful measure of cognitive function is the observation that TICS-m scores remained similar between 1 month and 6 month assessments (Supplementary Figure 2). Although neuropsychological testing was not performed to internally validate results from the TICS-m, our study used an objective and clinically relevant means of assessing cognitive status rather than methods relying on chart identified diagnoses of cognitive impairment or dementia. Due to attrition at the 1 month follow-up, we may have lacked power to detect a significant risk of mortality in patients with moderate/severe CIND as compared to patients with normal cognitive status. We estimated that our study had 80% power to detect a minimum of a 6% difference in the mortality rate between the referent group (normal cognitive function) and the moderate/severe CIND group but we actually observed an 8% difference in mortality between these groups; however, these estimates were based on the unadjusted results. The association between cognitive impairment and outcomes may have been influenced by unmeasured confounders, such as socioeconomic factors, medication effects, or co-existing affective disorders. Selection bias may have been a potentially important limitation in our study as 39% of AMI patients ≥65 years did not have the TICS-m performed 1 month after AMI. Of the 493 patients that did not have the TICS-m assessment, 345 were excluded for the following reasons: 64 were too ill (18.6%), 20 had died (0.6%), 77 refused (22.3%), and 184 were lost to follow up (53.3%). The remaining 148 patients started but did not complete the interview to assess cognitive function. As compared to the analysis cohort, patients excluded from the analysis (n = 493) due to lack of cognitive assessment 1 month after AMI were slightly older (74.1 ± 6.9 years), were as likely to be women (41.6%), were less often Caucasian (66.1%), and less likely to have had education beyond high school (37.7%). These characterstics are associated with CIND and suggest that the findings of the association between CIND and outcomes in our study are probably conservative. However, non-participants also had similar mean left ventricular ejection fraction (47.5 ± 13.4), rates of in-hospital cardiac catheterization (88.0%), and baseline health status on the SAQ quality of life (66.6±24.0) as patients in the analysis. Finally, it is not known to what degree patient preference for conservative (non-invasive) management played a role in the differential rates of cardiac catheterization, as we do not have information regarding the reasons why catheterization was not performed.

Conclusion

CIND is highly prevalent among older adults 1 month after an AMI, with one in four patients exhibiting moderate/severe CIND. Patients with moderate/severe CIND were less likely to be referred for cardiac catheterization, revascularization, or cardiac rehabilitation, but received similar medications at discharge. A clinically important 2 fold hazard in risk-adjusted mortality in moderate/severe CIND patients was observed, though quality of life was similar. Further studies are needed to understand the relationships between cognitive function as a comorbidity and risk factor and clinical outcomes in the growing population of older patients with AMI.

Supplementary Material

Distribution of the education-adjusted Telephone Interview for Cognitive Status-modified (TICS-m) in patients ≥65 years old 1 month after acute myocardial infarction.

Change scores for the 1 and 6 month Telephone Interview for Cognitive Status-modified (TICS-m).

Acknowledgments

Others Funding Sources and Affiliations

Dr. Gharacholou is a participant in the NIH clinical research loan repayment program (1L30 AG034828-01) and is currently at the University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health, Division of Cardiology, Madison, WI 53792.

Footnotes

Disclosures

Dr. Spertus developed and owns the copyrights for the Seattle Angina Questionnaire. Dr. Rich reports research grants from Astellas Pharma US (<$10,000) and consulting fees from Sanofi-Aventis (>$10,000). The remaining authors report no disclosures (S.M.G, K.J.R., S.V.A., P.A.P., M.S., T.H., H.M.K., E.D.P, K.P.A).

References

- 1.Floyd KC, Yarzebski J, Spencer FA, et al. A 30-year perspective (1975–2005) into the changing landscape of patients hospitalized with initial acute myocardial infarction: Worcester Heart Attack Study. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2009;2(2):88–95. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.108.811828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ho MP, Eng MH, Rumsfeld JS, et al. The influence of age on health status outcomes after acute myocardial infarction. Am Heart J. 2008;155:855–61. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2007.11.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Plassman BL, Langa KM, Fisher GG, et al. Prevalence of cognitive impairment without dementia in the United States. Ann Intern Med. 2008;148(6):427–434. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-148-6-200803180-00005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Silbert BS, Scott DA, Evered LA, et al. Preexisting cognitive impairment in patients scheduled for elective coronary artery bypass graft surgery. Anesth Analg. 2007;104(5):1023–1028. doi: 10.1213/01.ane.0000263285.03361.3a. tables of contents. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tabert MH, Albert SM, Borukhova-Milov L, et al. Functional deficits in patients with mild cognitive impairment: prediction of AD. Neurology. 2002;58(5):758–764. doi: 10.1212/wnl.58.5.758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sloan FA, Trogdon JG, Curtis LH, et al. The effect of dementia on outcomes and process of care for Medicare beneficiaries admitted with acute myocardial infarction. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52(2):173–181. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52052.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hovanesyan A, Rich MW. Outcomes of acute myocardial infarction in nonagenarians. Am J Cardiol. 2008;101(10):1379–1383. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2008.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brandt J, Spencer M, Folstein M. The telephone interview for cognitive status. Neuropsychiatry Neuropsychol Behav Neurol. 1988;1:111–117. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brandt J, Welsh KA, Breitner JC, et al. Hereditary influences on cognitive functioning in older men. A study of 4000 twin pairs. Arch Neurol. 1993;50(6):599–603. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1993.00540060039014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dal Forno G, Chiovenda P, Bressi F, et al. Use of an Italian version of the telephone interview for cognitive status in Alzheimer’s disease. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2006;21(2):126–133. doi: 10.1002/gps.1435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.de Jager CA, Budge MM, Clarke R. Utility of TICS-M for the assessment of cognitive function in older adults. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2003;18(4):318–324. doi: 10.1002/gps.830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moylan T, Das K, Gibb A, et al. Assessment of cognitive function in older hospital inpatients: is the Telephone Interview for Cognitive Status (TICS-M) a useful alternative to the Mini Mental State Examination? Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2004;19(10):1008–1009. doi: 10.1002/gps.1181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Breitner JC, Welsh KA, Gau BA, et al. Alzheimer’s disease in the National Academy of Sciences-National Research Council Registry of Aging Twin Veterans. III. Detection of cases, longitudinal results, and observations on twin concordance. Arch Neurol. 1995;52(8):763–771. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1995.00540320035011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ware J, Jr, Kosinski M, Keller SD. A 12-Item Short-Form Health Survey: construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Med Care. 1996;34(3):220–233. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199603000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Piotrowicz K, Noyes K, Lyness JM, et al. Physical functioning and mental well-being in association with health outcome in patients enrolled in the Multicenter Automatic Defibrillator Implantation Trial II. Eur Heart J. 2007;28(5):601–607. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehl485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rumsfeld JS, MaWhinney S, McCarthy M, Jr, et al. Health-related quality of life as a predictor of mortality following coronary artery bypass graft surgery. Participants of the Department of Veterans Affairs Cooperative Study Group on Processes, Structures, and Outcomes of Care in Cardiac Surgery. JAMA. 1999;281(14):1298–1303. doi: 10.1001/jama.281.14.1298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dorr DA, Jones SS, Burns L, et al. Use of health-related, quality-of-life metrics to predict mortality and hospitalizations in community-dwelling seniors. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006;54(4):667–673. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2006.00681.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Spertus JA, Winder JA, Dewhurst TA, et al. Monitoring the quality of life in patients with coronary artery disease. Am J Cardiol. 1994;74(12):1240–1244. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(94)90555-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Spertus JA, Jones P, McDonell M, et al. Health status predicts long-term outcome in outpatients with coronary disease. Circulation. 2002;106(1):43–49. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000020688.24874.90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mozaffarian D, Bryson CL, Spertus JS, et al. Anginal symptoms consistently predict total mortality among outpatients with coronary artery disease. Am Heart J. 2003;146:1015–22. doi: 10.1016/S0002-8703(03)00436-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Arnold SV, Morrow DA, Lei Y, et al. Economic impact of angina after an acute coronary syndrome: insights from the MERLIN-TIMI 36 trial. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2009;2:344–53. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.108.829523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Harrell FE. Logistic Regression and Survival Analysis. New York: Springer-Verlag; 2001. Regression modeling strategies with applications to linear models. [Google Scholar]

- 23.R version 2.10.1. R Development Core Team. R: a language and environment for statistical computing. R foundation for statistical computing; Vienna, Austria: 2006. URL http://www.R-project.org. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Raghunathan TE, Solenberger PW, Van Hoewyk J. Survey research center. Institute for social research. University of Michigan; 2002. IVEware: imputation and variance estimation software - user guide. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rosenbaum PR. Model-Based Direct Adjustment. J Am Stat Assoc. 1987;82:387–394. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Roberts RO, Knopman DS, Geda YE, et al. Coronary heart disease is associated with non-amnestic mild cognitive impairment. Neurobiol Aging. 2010;31(11):1894–902. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2008.10.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Khatri M, Nickolas T, Moon YP, et al. CKD associates with cognitive decline. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;20(11):2427–32. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2008101090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chaudhry SI, Wang Y, Gill TM, et al. Geriatric conditions and subsequent mortality in older patients with heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;55(4):309–316. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.07.066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chodosh J, Petitti DB, Elliott M, et al. Physician recognition of cognitive impairment: evaluating the need for improvement. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52(7):1051–1059. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52301.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chan MY, Mahaffey KW, Sun LJ, et al. Prevalence, predictors, and impact of conservative medical management for patients with non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndromes who have angiographically documented significant coronary disease. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2008;1(4):369–378. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2008.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pasquali SK, Alexander KP, Coombs LP, et al. Effect of cardiac rehabilitation on functional outcomes after coronary revascularization. Am Heart J. 2003;145(3):445–451. doi: 10.1067/mhj.2003.172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Landi F, Russo A, Barillaro C, et al. Physical activity and risk of cognitive impairment among older persons living in the community. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2007;19(5):410–416. doi: 10.1007/BF03324723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Baker LD, Frank LL, Foster-Schubert K, et al. Effects of aerobic exercise on mild cognitive impairment: a controlled trial. Arch Neurol. 67(1):71–79. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2009.307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Suaya JA, Stason WB, Ades PA, et al. Cardiac rehabilitation and survival in older coronary patients. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;54(1):25–33. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.01.078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hammill BG, Curtis LH, Schulman KA, et al. Relationship between cardiac rehabilitation and long-term risks of death and myocardial infarction among elderly Medicare beneficiaries. Circulation. 2010;121(1):63–70. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.876383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Logsdon RG, Gibbons LE, McCurry SM, et al. Assessing quality of life in older adults with cognitive impairment. Psychosom Med. 2002;64:510–9. doi: 10.1097/00006842-200205000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Distribution of the education-adjusted Telephone Interview for Cognitive Status-modified (TICS-m) in patients ≥65 years old 1 month after acute myocardial infarction.

Change scores for the 1 and 6 month Telephone Interview for Cognitive Status-modified (TICS-m).