Abstract

Cryptotanshinone (CPT), a natural compound isolated from the plant Salvia miltiorrhiza Bunge, is a potential anticancer agent. However, the underlying mechanism is not well understood. Here, we show that CPT induced caspase-independent cell death in human tumor cells (Rh30, DU145, and MCF-7). Besides downregulating antiapoptotic protein expression of survivin and Mcl-1, CPT increased phosphorylation of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) and c-jun N-terminal kinase (JNK), and inhibited phosphorylation of extracellular signal–regulated kinases 1/2 (Erk1/2). Inhibition of p38 with SB202190 or JNK with SP600125 attenuated CPT-induced cell death. Similarly, silencing p38 or c-Jun also in part prevented CPT-induced cell death. In contrast, expression of constitutively active mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase 1 (MKK1) conferred resistance to CPT inhibition of Erk1/2 phosphorylation and induction of cell death. Furthermore, we found that all of these were attributed to CPT induction of reactive oxygen species (ROS). This is evidenced by the findings that CPT induced ROS in a concentration- and time-dependent manner; CPT induction of ROS was inhibited by N-acetyl-l-cysteine (NAC), a ROS scavenger; and NAC attenuated CPT activation of p38/JNK, inhibition of Erk1/2, and induction of cell death. The results suggested that CPT induction of ROS activates p38/JNK and inhibits Erk1/2, leading to caspase-independent cell death in tumor cells.

Introduction

Cryptotanshinone (CPT) is one of the major tanshinones isolated from Salvia miltiorrhiza Bunge (Danshen), which has been used in traditional Chinese medicine for treatment of a variety of diseases including coronary artery disease (1), hyperlipidemia (2), acute ischemic stroke (2), and chronic renal failure (3), chronic hepatitis (4), and Alzheimer disease (5). Recent studies have further shown that Danshen also exhibits anticancer activity, which is attributed to the cytostatic and cytotoxic effects of the tanshinones including tanshinone I, tanshinone IIA, dihydrotanshinone, and CPT isolated from the herb (6-8). Most recently, we have shown that CPT is the most potent anticancer agent among the tanshinones, by inhibiting proliferation of cancer cells (9). CPT inhibition of cell proliferation is related to inhibition of cyclin D1 expression, which results in decreased phosphorylation of retinoblastoma (Rb) protein, leading to cell-cycle arrest in G1 phase (9). Our further studies also indicate that CPT induces cell death of cancer cells. However, the underlying mechanism is not clear.

Increasing evidence indicates that members of the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) family are involved in the regulation of cell survival or death (10, 11). In mammalian cells, there exist at least 3 distinct groups of MAPKs, including extracellular signal–regulated kinases 1/2 (Erk1/2), c-jun N-terminal kinase (JNK), and p38 MAPK (10). JNK and p38 are known as stress-activated protein kinases (11). In response to extracellular stress stimuli, such as oxidative stress, heat and osmotic shock, chemotherapeutic drugs, UV irradiation, and inflammatory cytokines, JNK/p38 are generally activated (11-15), which may upregulate proapoptotic genes through the activation of specific transcription factors or directly modulate the activities of mitochondrial pro- and antiapoptotic proteins through distinct phosphorylation events, resulting in stress stimulus-initiated extrinsic and mitochondrial intrinsic apoptosis (11-15). In response to growth factors, cytokines, virus infection, ligands for heterotrimeric guanine nucleotide-binding protein (G protein)-coupled receptors, transforming agents, and carcinogens, Erk1/2 could be activated (10, 16, 17). Activation of Erk1/2 generally promotes cell proliferation, differentiation, and survival (10, 16, 17).

Here, we show that CPT induced caspase-independent cell death in human rhabdomyosarcoma (Rh30), prostate (DU145), and breast (MCF-7) cancer cells. Mechanistically, CPT induced reactive oxygen species (ROS), which activate JNK/p38 and inhibit Erk1/2, triggering cell death.

Materials and Methods

Materials

CPT [≥98% purity by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC)] was purchased from Xi’an Hao-Xuan Bio-Tech Co., Ltd. CPT was dissolved in 100% ethanol to prepare the stock solutions (20 mmol/L), aliquoted and stored at −20°C. RPMI-1640 and Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (DMEM) were provided by Mediatech. FBS was from Hyclone, and 0.05% trypsin-EDTA was from Invitrogen. CellTiter 96 AQueous One Solution Cell Proliferation Assay kit was from Promega. Annexin V-FITC Apoptosis Detection Kit I was from BD Biosciences. CM-H2DCFDA was from Invitrogen and N-acetyl-L-cysteine (NAC) from Sigma. Caspase-3/7 Assay Kit (catalog no. 71118) was purchased from AnaSpec, Inc. Enhanced chemiluminescence solution was from Perkin-Elmer Life Science. Z-VAD-FMK was purchased from Alexis Biochemicals. SB202190 and SP600125 were obtained from LC Laboratories and were dissolved in DMSO to prepare stock solutions (10 and 20 mmol/L, respectively, stored at −20°C).

Cell lines and culture

Human rhabdomyosarcoma (Rh30; a gift from Dr. Peter J. Houghton, Nationwide Children’s Hospital, Columbus, OH) and prostate carcinoma (DU145) cells (American Type Culture Collection) were grown in antibiotic-free RPMI-1640 medium supplemented with 10% FBS. Human breast carcinoma (MCF-7) cells (American Type Culture Collection) were grown in antibiotic-free DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS. No authentication was done by the authors. All cells were cultured in a humid incubator (37°C, 5% CO2).

Cell viability assay

Cells were seeded at a density of 1 × 104 cells per well in a flat-bottomed 96-well plate. Next day, the cells were treated with CPT (0–40 μmol/L) for 48 hours. Subsequently, each well was added 20 μL of one solution reagent (Promega) and incubated for 3 hours. Cell viability was determined by measuring the optical density (OD) at 490 nm using a Wallac 1420 Multilabel Counter (Perkin-Elmer Life Sciences).

Cell apoptosis analysis

Apoptosis assay was conducted as described previously (18). Briefly, cells were seeded in 100-mm dishes at a density of 2 × 106 cells per dish in the growth medium and grown overnight at 37°C in a humidified incubator with 5% CO2. Cells were treated with CPT (0–40 μmol/L) for 72 hours or with 10 μmol/L CPT for 0 to 72 hours, followed by apoptosis assay by the Annexin V-FITC Apoptosis Detection Kit I (BD Biosciences). Cells treated with vehicle alone (100% ethanol) were used as a control.

Cell morphologic analysis

Rh30 or DU145 cells were seeded in 6-well plates at a density of 5 × 104 cells per well (in triplicate). Next day, the cells were exposed to CPT (0–40 μmol/L). After incubation for 5 days, the images were taken with an Olympus inverted phase-contrast microscope (Olympus Optical Co.; × 200) equipped with the Quick Imaging system.

Caspase-3/7 activity assay

Caspase-3/7 activity was measured as described (19), by the Sensolyte Homogeneous AMC caspase-3/7 assay kit (AnaSpec, Inc.). Briefly, cells grown in a 96-well black-wall and clear-bottom plate were treated with CPT (0–40 μmol/L) for 24 hours. Subsequently, caspase-3/7 substrate solution (50 μL/well) was added, followed by gently shaking and incubation at room temperature for 1 hour. Finally, the fluorescence intensity was recorded by excitation at 354 nm and emission at 442 nm using a Wallac 1420 Multilabel Counter (Perkin-Elmer Life Sciences).

ROS detection

ROS detection was conducted as described previously (20). Briefly, cells were seeded at a density of 1 × 104 cells per well in a flat-bottomed 96-well plate. Next day, the cells were incubated with CPT (0–40 μmol/L) for 24 hours or 10 μmol/L CPT for 0 to 24 hours, with 6 replicates of each treatment, followed by loading with 10 μmol/L CM-H2DCFDA following the manufacturer’s protocol. In some cases, cells were pretreated with NAC (5 mmol/L) for 1 hour, and then treated with/without CPT (10 and 20 μmol/L) for 24 hours, followed by loading with 10 μmol/L CM-H2DCFDA for 2 hours. The fluorescent intensity was recorded by excitation at 485 nm and emission at 535 nm using a Wallac 1420 Multilabel Counter (PerkinElmer Life Sciences).

Lentiviral shRNA cloning, production, and infection of cells

Lentiviral shRNAs to p38 MAPK and c-Jun were generated, as described previously (21). Lentiviral shRNA to GFP (21) were used as a control. For use, monolayer cells, grown to about 70% confluence, were infected with above lentivirus-containing supernatant in the presence of 8 μg/mL polybrene for 12 hours twice at an interval of 6 hours. Uninfected cells were eliminated by exposure to 2 μg/mL puromycin. In 5 days, cells were used for experiments.

Recombinant adenoviral construction and infection of cells

The recombinant adenovirus expressing Flag-tagged constitutively active MKK1 (Ad-MKK1-ca) was generated as described previously (22). The virus was amplified and titrated as described (23). For experiments, cells grown in 6-well plates in the growth medium were infected with Ad-MKK1-ca for 24 hours at the multiplicity of infection of 5. Subsequently, the cells were treated with CPT (10 or 20 μmol/L) for 8 hours. Ad-GFP encoding GFP (23) served as a control. Expression of Flag-tagged constitutively active MEK1 was confirmed by Western blotting with antibodies against Flag.

Western blot analysis

Western blotting was carried out as described previously (9). Briefly, treated cells were washed twice with cold PBS and then lysed in the lysis buffer [50 mmol/L Tris, pH 7.2; 150 mmol/L NaCl; 1% sodium deoxycholate; 0.1% SDS; 1% Triton X-100; 10 mmol/L NaF; 1 mmol/L Na3VO4; protease inhibitor cocktail (1:1,000, Sigma)]. Lysates were sonicated for 10 seconds and centrifuged at 13,000 × g for 10 minutes at 4°C. Protein concentration was determined by BCA Protein Assay Kit (Pierce). The following primary antibodies were used: JNK, phospho-JNK (Thr183/Tyr185), c-Jun, phospho-c-Jun (Ser63), Erk2, p38, phospho-p38 (Thr180/Tyr182), PARP, apoptosis-inducing factor (AIF), Bcl-2, survivin, Mcl-1, Flag (all from Santa Cruz Biotechnology), Bcl-xL, BAK, BAX (Biomeda), BAD, phospho-Erk1/2 (Thr202/Tyr204; Cell Signaling), and β-tubulin (Sigma). Goat anti-mouse IgG–horseradish peroxidase (HRP), goat anti-mouse IgM-HRP, and goat anti-rabbit IgG-HRP were purchased from Pierce.

Immunohistochemistry for AIF

Cells were seeded at a density of 3 × 105 cells per well in a 6-well plate containing a sterilized poly-d-lysine–coated coverslip per well. After treatment with CPT (0–20 μmol/L) for 24 hours, cells were rinsed with PBS and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 2 hours at 4°C. The coverslips were then heated in antigen retrieval buffer (0.01 mmol/L sodium citrate buffer, pH 6.0) in a water bath at 95°C for 10 minutes. After rinsing 3 times in PBS, the cells were permeabilized in 0.1% Triton X-100 for 10 minutes at room temperature and incubated with 10% normal goat serum (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) for 20 minutes to block nonspecific binding. Subsequently, the cells were immunostained by incubating with mouse monoclonal antibody against AIF (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) overnight at 4°C and fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) for 2 hours at room temperature. The cells were further counterstained with 1 μg/mL 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole dihydrochloride (DAPI; Sigma) for 2 minutes at room temperature. After a brief rinsing with PBS, the coverslips were mounted on the slides in glycerol/PBS (1:1, v/v). Finally, FITC (green) and DAPI (blue) staining were visualized and photographed with a Nikon Eclipse TE300 fluorescence microscope (Nikon Instruments Inc.; × 600) equipped with a digital camera.

Statistical analysis

Results were expressed as mean values ± standard error (mean ± SE). These data were analyzed by one-way ANOVA followed by posthoc Dunnett t test for multiple comparisons. A level of P < 0.05 was considered to be significant.

Results

CPT induces death in cancer cells

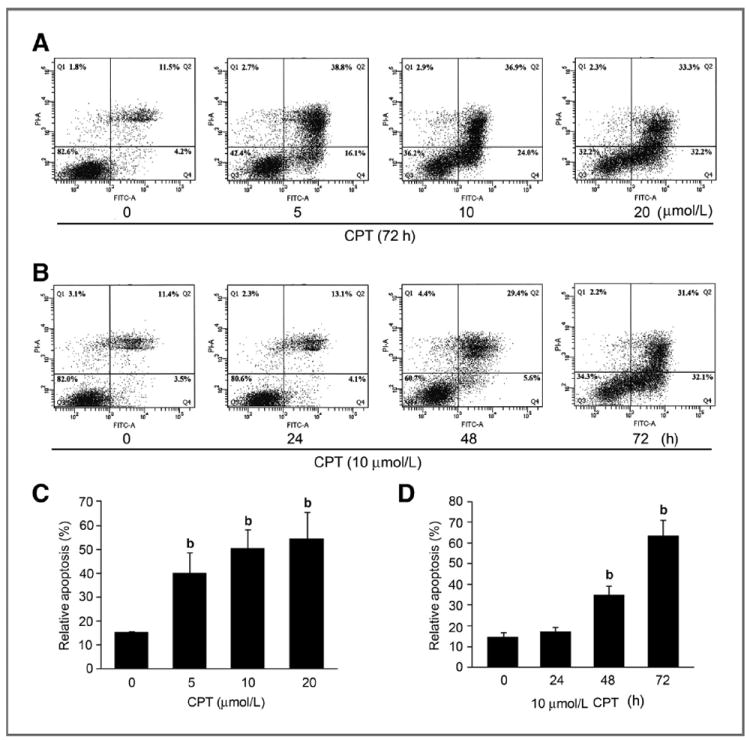

Recently, we have shown that CPT inhibits proliferation of rhabdomyosarcoma (Rh30), prostate (DU145), and breast (MCF-7) cancer cells (9). To further unveil the anticancer mechanism of CPT, we investigated whether CPT induces programmed cell death or apoptosis in these cancer cells. As Annexin V and propidium iodide (PI) staining is routinely used for detection of apoptosis, Annexin V-FITC Apoptosis Detection Kit I (BD Biosciences) was used. We found that CPT induced death in Rh30 cells in a concentration-dependent manner (Fig. 1A and C). Approximately 3- to 4-fold increase of cell death was observed, when the cells were exposed to CPT (5–20 μmol/L) for 72 hours, in comparison with the control (CPT = 0 μmol/L; Fig. 1A and C). In addition, CPT also induced death of Rh30 cells in a time-dependent manner (Fig. 1B and D). Exposure to CPT (20 μmol/L) for 24 hours only induced a marginal but not significant cell death. However, treatment for 48 and 72 hours significantly increased the cell death, by 2.3- and 4.3-fold, respectively (Fig. 1B and D). Similar results were also observed in DU145 and MCF-7 cells (Supplementary Fig. S1A and S1B), indicating that CPT-induced cell death is independent of cell type. By morphologic analysis, we found that CPT also induced cell shrinkage and rounding (Supplementary Fig. S1C), suggesting apoptosis.

Figure 1.

CPT induces apoptotic cell death in tumor cells. Rh30 cells grown in 100-mm dishes (2 × 106 cells per dish) were treated with indicated concentrations of CPT (0–20 μmol/L) for 72 hours (A), or with 10 μmol/L CPT for indicated time (B), and then stained with Annexin V-FITC and PI, followed by flow cytometric analysis. Results (A and B) are presented as mean ± SE (n = 3). b, P < 0.01, difference versus control group.

CPT-induced cell death is caspase independent

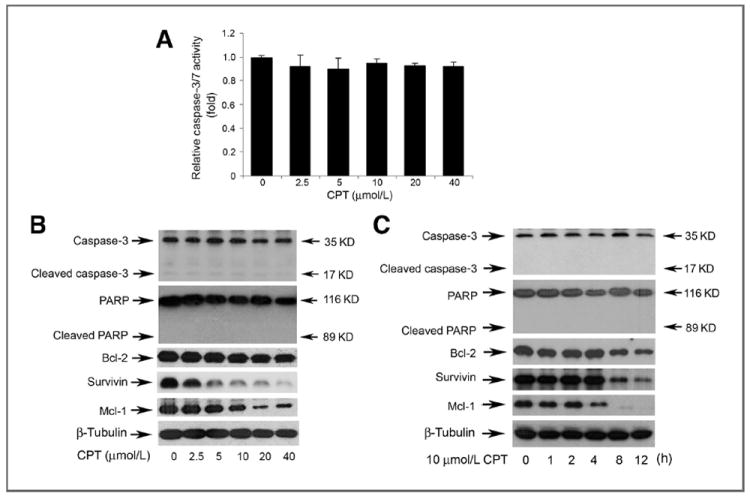

Programmed cell death can be triggered by caspase-dependent and -independent mechanisms (24). With regard to caspase-dependent mechanism, activation of other caspases (e.g., caspase-8, caspase-9) finally results in activation of caspase-3/7, leading to apoptosis (24). To determine whether CPT-induced cell death is through activating caspase pathway, DU145 cells were exposed to CPT (0–40 μmol/L) for 24 hours, followed by caspase-3/7 activity assay. As shown in Fig. 2A, treatment with CPT (2.5–40 μmol/L) for 24 hours did not significantly alter the activities of caspase-3/7 in the DU145 cells, comparing with the control, indicating that CPT did not activate caspase pathway. This is further supported by the findings that CPT did not increase cleavage (89 kDa) of PARP (Fig. 2B), a well-known substrate of activated caspases. In addition, we found that pretreatment for 1 hour with 10 μmol/L Z-VAD-FMK, a cell-permeant pan-caspase inhibitor, failed to attenuate CPT-induced cell death significantly (Supplementary Fig. S2). The results support the notion that CPT-induced cell death is through caspase-independent mechanism.

Figure 2.

CPT induces caspase-independent cell death in tumor cells. A, DU145 cells grown in a black wall 96-well plate were treated with CPT (0–40 μmol/L) for 24 hours, followed by adding caspase-3/7 substrate solution (50 μL/well). After incubation at room temperature for 1 hour, the fluorescence intensity was recorded by excitation at 354 nm and emission at 442 nm using a Wallac 1420 Multilabel Counter. Results are presented as mean ± SE (n = 6). Note: CPT did not significantly alter the activities of caspase-3/7. DU145 cells were grown in 6-well plates and treated with CPT at indicated concentrations for 8 hours (B), or with CPT (10 μmol/L) for indicated time (C), followed by Western blot analysis with indicated antibodies.

As AIF and Bcl-2 family members are involved in caspase-independent apoptosis (25, 26), we next investigated whether CPT-induced cell death is by targeting these proteins. In this study, we found that treatment with CPT neither altered the cellular protein level of AIF (Supplementary Fig. S3, top), nor induced a translocation of AIF from mitochondria to nucleus in Rh30 cells (Supplementary Fig. S3, bottom). However, CPT downregulated expression of antiapoptotic proteins, such as Bcl-2, survivin, and Mcl-1, in DU145 (Fig. 2B) and Rh30 cells (Supplementary Fig. S4) in a concentration-dependent manner. Apparently, CPT failed to affect expression of proapoptotic proteins, including BAD, BAK, and BAX (Supplementary Fig. S4). Therefore, CPT-induced caspase-independent cell death is correlated to decreased expression of antiapoptotic proteins (Bcl-2, Mcl-1, and survivin).

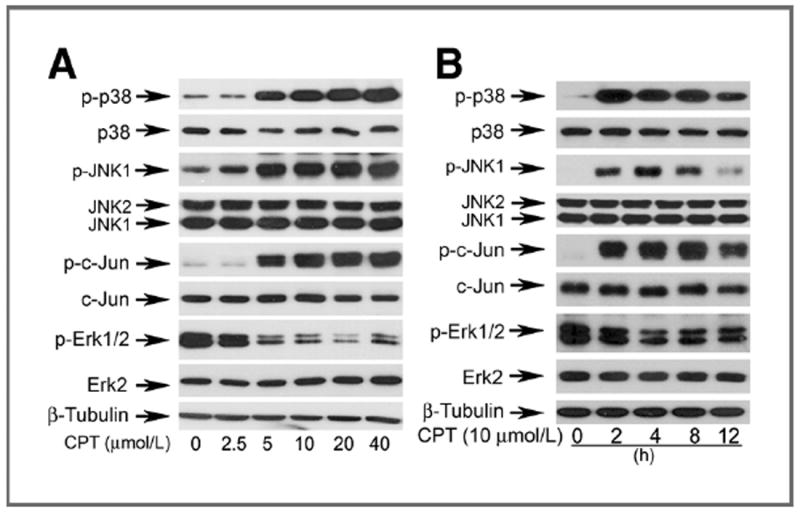

CPT activates p38/JNK and inhibits Erk1/2, leading to cell death

As MAPKs are also involved in caspase-independent cell death (27, 28), we hypothesized that CPT induces death of cancer cells by targeting JNK, p38, and Erk1/2 pathways. For this, DU145 cells were exposed to CPT (0–40 μmol/L) for 8 hours, or CPT (10 μmol/L) for 0 to 12 hours, followed by Western blot analysis. As shown in Fig. 3A, CPT did not obviously alter total cellular protein expression of JNK, c-Jun, p38, and Erk1/2, but induced phosphorylation of JNK, c-Jun (a substrate of JNK), and p38, and inhibited phosphorylation of Erk1/2 in a concentration-dependent manner. Remarkable increase of phospho-JNK/c-Jun/p38 and decrease of phospho-Erk1/2 were detectable at 5 μmol/L. CPT also activated JNK/p38 and inhibited Erk1/2 in a time-dependent manner. It should be noted that CPT activation of JNK/p38 was rapid and sustained. Within 2-hour treatment, CPT was able to induce robust phosphorylation of JNK, c-Jun, and p38; and the hyperphosphorylation of JNK, c-Jun, and p38 persisted for at least 8 hours. After 12 hours treatment, phosphorylation of c-Jun and p38 gradually declined, but still remained much higher than the basal levels (Fig. 3B).

Figure 3.

CPT activates p38/JNK and inhibits Erk1/2 in a concentration-and time-dependent manner. DU145 cells grown in 6-well plates were treated with CPT at indicated concentrations for 8 hours (A), or 10 μmol/L CPT for indicated time (B), followed by Western blot analysis with indicated antibodies.

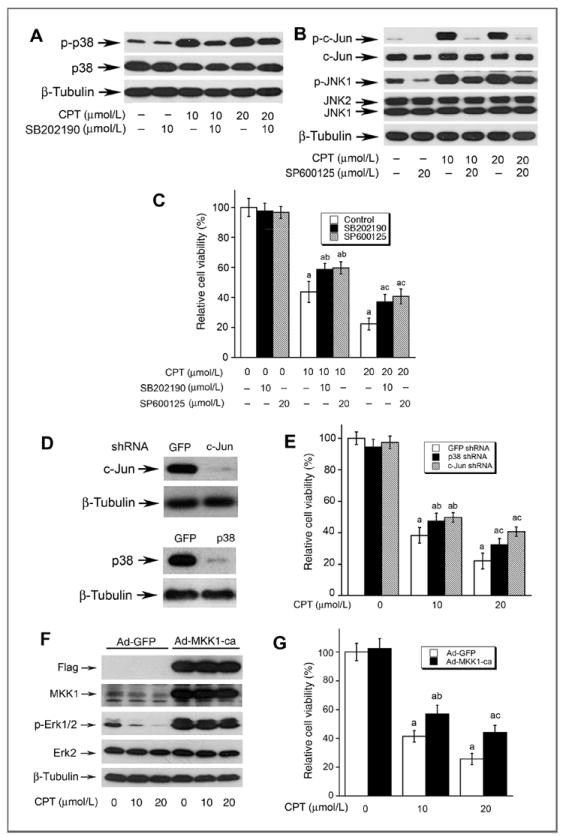

To determine whether activation of JNK/p38 correlates to CPT-induced cell death, SP600125 and SB202190 were used to block JNK and p38, respectively. Pretreatment of DU145 cells with SP600125 (20 μmol/L) or SB202190 (10 μmol/L) markedly prevented CPT-induced phosphorylation of c-Jun or p38, respectively (Fig. 4A and B). Of interest, inhibition of JNK and p38 with the inhibitors significantly attenuated CPT-induced death in DU145 cells (Fig. 4C), suggesting that CPT induced death of the cancer cells in part by activation of JNK/p38. This is further supported by the observations that silencing c-Jun or p38 also partially prevented CPT-induced death in Rh30 cells (Fig. 4D and E).

Figure 4.

CPT-induced cell death is in part by activation of p38/JNK and inhibition Erk1/2. A–C, DU145 cells, grown in 6-well plates (A and B) or 96-well plates (C), were pretreated with or without SB202190 (10 μmol/L) or SP600125 (20 μmol/L) for 30 minutes, and then exposed to CPT (0, 10, 20 μmol/L) for 8 hours (for Western blotting), or for 48 hours (for cell viability), followed by Western blot analysis using indicated antibodies (A and B), or cell viability assay using one solution reagent (C). D, Rh30 cells grown in 6-well plates were infected with lentiviral shRNAs to p38, c-Jun, and GFP, respectively. In 5 days, whole-cell lysates were subjected to Western blotting using indicated antibodies. Note: Lentiviral shRNA to p38 or c-Jun, but GFP, downregulated cellular protein expression of p38 or c-Jun by approximately 90%. E, Rh30 cells grown 96-well plates, infected with lentiviral shRNA to p38, c-Jun, and GFP, respectively, were exposed to CPT at indicated concentrations for 48 hours, followed by cell viability assay using one solution reagent. Results are presented as mean ± SE (n = 3). a, P < 0.05, difference versus GFP shRNA group; b, P < 0.05, difference versus 10 μmol/L SB202190 group; c, P < 0.05, difference versus 20 μmol/L SP600125 group. F, Rh30 cells grown in 6-well plates were infected with recombinant adenoviruses expressing Flag-tagged constitutively active MKK1 (Ad-MMK1-ca) and GFP (Ad-GFP, control), respectively. In 24 hours, whole-cell lysates were subjected to Western blotting using indicated antibodies. Note: Ad-MKK1-ca, but Ad-GFP, increased expression of MKK1 by 5-fold in Rh30 cells. G, Rh30 cells grown in 96-well plates, infected with Ad-MKK1 and Ad-GFP respectively, were exposed to CPT at indicated concentrations for 48 hours, followed by cell viability assay using one solution reagent. Results are presented as mean ± SE (n = 3). a, P < 0.05, difference versus 0 μmol/L CPT group; b, P < 0.05, difference versus 10 μmol/L CPT group; c, P < 0.05, difference versus 20 μmol/L CPT group.

In addition, we also investigated whether inhibition of Erk1/2 is associated with CPT-induced cell death. Mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase 1 (MKK1) is the upstream kinase of Erk, which directly phosphorylates Erk to transduce the signal induced by different stimuli (29). As expected, infection of Rh30 cells with a recombinant adenoviral vector expressing Flag-tagged constitutively active MKK1 (Ad-MKK1-ca), but not GFP (Ad-GFP), increased cellular protein expression of MKK1 by 5-fold. Ectopic expression of constitutively active MKK1, but not GFP, induced a robust phosphorylation of Erk1/2 (Fig. 4F). Importantly, expression of constitutively active MKK1 conferred high resistance to CPT inhibition of Erk1/2 phosphorylation (Fig. 4F), as well as CPT inhibition of cell viability (Fig. 4G). The results imply that CPT induces death of the cancer cells also partially by inhibiting Erk1/2 activity. Taken together, our findings suggest that CPT activates p38/JNK and inhibits Erk1/2, leading to death of cancer cells.

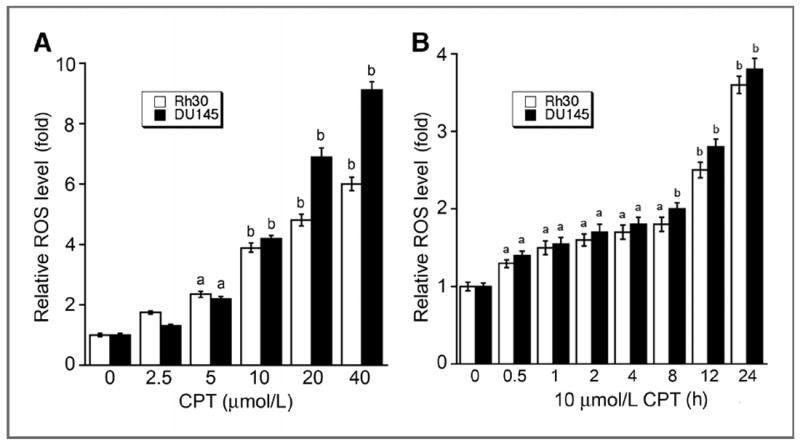

CPT-induced cell death is attributed to induction of ROS

Because ROS can induce caspase-independent cell death (30), we speculated that CPT-induced cell death links to ROS induction. To this end, first we tested whether CPT induces ROS in cancer cells. CM-H2DCFDA, a stable nonfluorescent molecule, which can be oxidized by oxygen radicals to form fluorescent molecule excitated by specific wavelength lights, was used to measure the levels of ROS in Rh30 and DU145 cells treated with CPT. As illustrated in Fig. 5, CPT induced ROS in the cells in a concentration-and time-dependent manner. Treatment with CPT for 24 hours at 10 to 20 μmol/L increased the ROS levels by 4- to 7-fold (Fig. 5A), and treatment with CPT at 10 μmol/L for 12 to 24 hours elevated the ROS levels by 2.5- to 4-fold (Fig. 5B). Moreover, CPT induced ROS rapidly. Within 1 hour treatment, CPT (10 μmol/L) was able to significantly elevate the ROS level in Rh30 and DU145 cells (Fig. 5B).

Figure 5.

CPT increases ROS levels in tumor cells in a concentration-and time-dependent manner. Rh30 and DU145 cells grown in 96-well plates were treated with CPT at indicated concentrations for 24 hours (A), or with 10 μmol/L CPT for indicated time (B), followed by ROS detection using CM-H2DCFDA. Fluorescent intensity was recorded by excitation at 485 nm and emission at 535 nm using a Wallac 1420 Multilabel Counter. Results are presented as mean ± SE (n = 6). a, P < 0.05; b, P < 0.01, difference versus 0 μmol/L CPT group (A) or 0 hour CPT group (B).

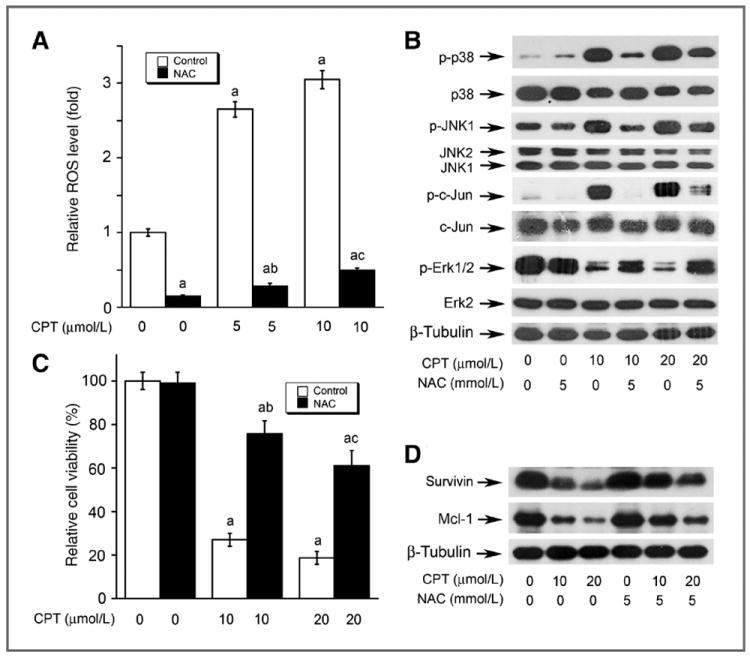

Next, we examined whether CPT induction of ROS is really responsible for cell death. As expected, pretreatment with NAC (5 mmol/L), a powerful antioxidant and ROS scavenger, almost completely blocked CPT-induced ROS in DU145 cells (Fig. 6A). NAC profoundly attenuated CPT-induced phosphorylation of JNK, c-Jun, and p38, and CPT-inhibited phosphorylation of Erk1/2 as well as protein expression of survivin and Mcl-1 (Fig. 6B). Of most importance, pretreatment with NAC significantly prevented CPT-induced cell death (Fig. 6C). Similar results were observed in Rh30 cells (data not shown). Collectively, the results suggest that CPT induction of ROS activates stress kinases (JNK/p38) and inhibits prosurvival molecules (Erk1/2, survivin, and Mcl-1), causing cell death.

Figure 6.

The effects of CPT on MAPKs are attributed to induction of ROS. DU145 cells, grown in 96-well plates (A and C) or 6-well plates (B and D), were pretreated with or without 5 mmol/L NAC for 30 minutes and then exposed to CPT at indicated concentrations for 24 (for ROS detection and Western blotting) or 48 hours (for cell viability assay), followed by ROS detection using CM-H2DCFDA (A), Western blot analysis (B and D) using indicated antibodies, or cell viability assay using one solution reagent (C). Results are presented in (A) and (C) as mean ± SE (n = 6). a, P < 0.05, difference versus 0 μmol/L CPT group; b, P < 0.05, difference versus 5 μmol/L (A) or 10 μmol/L (C) CPT group; c, P < 0.05, difference versus 10 μmol/L (A) or 20 μmol/L (C) CPT group.

Discussion

Recently, we have shown that CPT inhibits cancer cell proliferation by arresting cells in G1 phase, which is related to inhibition of cyclin D1 expression and Rb phosphorylation (9). Here, we further show that CPT induces death of cancer cells derived from rhabodamyosarcoma (Rh30), breast carcinoma (MCF-7), and prostate carcinoma (DU145), suggesting that CPT is a potential anticancer agent. However, in the present study, we noticed that CPT did not induce cell death until at quite high concentrations (>5 μmol/L) in the cancer cells. Achievable maximal plasma concentrations of CPT were only 14.7 to 55.8 ng/mL (i.e., 0.05–0.18 μmol/L) in rats and 3.1 to 227.4 ng/mL (i.e., 0.01–0.77 μmol/L) in dogs after oral administration of a single dose (30–180 mg/kg for rats; 17.8–1,080 mg/kg for dogs) of CPT (31). Thus, it is essential to develop a new formula (such as nanoparticles) of CPT to increase its bioavailability or more potent CPT analogs for cancer prevention and treatment. A recent study have shown that CPT at 50 μmol/L did not exhibit significant cytotoxicity in normal cells (32), further highlighting that CPT may be explored for tumor selective treatment.

It has been implicated that programmed cell death can be triggered through caspase-dependent and/or -independent mechanisms (24). In this study, we found that CPT-induced death of cancer cells was independent of activation of caspase cascade. This is evidenced by the findings that CPT treatment did not increase the activities of caspase-3/7; CPT failed to induce cleavage of PARP, a hallmark of activation of caspases; and Z-VAD-FMK, a cell-permeant pan-caspase inhibitor, was not able to prevent CPT-induced cell death significantly.

To gain insight into the mechanism of caspase-independent cell death, we initially focused on AIF, as AIF is ubiquitously expressed in normal cells and tumor cells, and plays a critical role in caspase-independent cell death (25). It has been described that in response to apoptotic stimuli, AIF is released from the mitochondria and migrates into the nucleus, binds to DNA and triggers the destruction of the DNA and cell death (25). Unfortunately, in this study we failed to detect translocation of AIF from mitochondria to nucleus in Rh30 cells (Supplementary Fig. S3), suggesting that CPT-induced cell death is independent of AIF. This is further supported by our observation that CPT did not induce DNA fragmentation by DNA laddering in Rh30 and DU145 cells (data not shown).

By pharmacologic inhibition and genetic manipulation, we finally identified that CPT activated p38/JNK and inhibited Erk1/2, leading to caspase-independent cell death in the cancer cells. Previous studies have shown that CPT inhibited complement 5a (C5a)-induced phosphorylation of Akt and Erk1/2, but not p38/JNK, thereby inhibiting chemotactic migration of RAW264.7 cells, a murine macrophage-like cell line (33). CPT also inhibited lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced phosphorylation of JNK, p38, and Erk1/2 in RAW264.7 cells, thus reducing production of proinflammatory mediators (TNF-α and interleukin-6; ref. 34). The discrepancy between these findings may be due to different cell types or stimuli used.

Our results indicate that the cytotoxic effect of CPT was attributed to induction of oxidative stress. This is strongly supported by the observations that CPT induced ROS in a concentration-dependent manner; pretreatment with NAC, a ROS scavenger, completely blocked CPT (5 and 10 μmol/L) induction of ROS, and partially attenuated CPT activation of p38/JNK and inhibition of Erk1/2, as well as induction of cell death. However, other reports suggest that CPT may function as an antioxidant as well (34, 35). For example, CPT (10 μg/ml, corresponding to 3.37 μmol/L) protects primary rat hepatocytes from bile acid–induced apoptosis by inhibiting JNK phosphorylation (35). Also, CPT (1 μmol/L) directly inhibits hydrogen peroxide–induced NF-κB luciferase activity in human umbilical vein endothelial cells (36). In this study, CPT did not significantly increase ROS level in Rh30 and DU145 cells until 5 μmol/L. Therefore, it is possible that at low concentrations (<4 μmol/L), CPT acts as an antioxidant whereas at high concentrations (>5 μmol/L) as an oxidant. From publications, it appears very common that a natural product may act as an antioxidant or oxidant, depending on concentrations and environmental conditions (37). Best examples include curcumin (38-40), resveratrol (41, 42), and (-)-epigallocatechin-3-gallate (EGCG, refs. 43, 44), which determine cell fate by redox mechanism.

Recently, we have shown that CPT inhibits cell proliferation by downregulating expression of cyclin D1 expression (9). Consistent with our previous finding (9), treatment with CPT (10 μmol/L) for 24 hours remarkably reduced cyclin D1 level (Supplementary Fig. S5). However, pretreatment with NAC (5 mmol/L) failed to attenuate CPT downregulation of cyclin D1 level (Supplementary Fig. S5). Given the fact that NAC prevents CPT-reduced cell viability dramatically (Fig. 6C), we think that CPT-induced cell death is probably not related to decreased expression of cyclin D1.

However, in the present study, we noticed that CPT strikingly downregulated expression of antiapoptotic proteins survivin and Mcl-1, which was, to some extent, related to ROS induction. Pretreatment with NAC only partially blocked the inhibitory effect of CPT on expression of these proteins (Fig. 6D), implicating other mechanisms involved. Currently, we do not know how CPT-induced ROS affect the levels of the two proteins. Recent studies have shown that CPT directly binds to Stat3 and blocks its dimerization, thereby inhibiting Stat3 phosphorylation (Y705) and function in DU145 cells (8). Mcl-1 and survivin are positively regulated by Stat3 (45, 46). In addition, most recent studies have revealed that CPT also inhibits the mTOR, a master regulator of translation initiation (9). Therefore, it will be interesting to elucidate whether CPT downregulation of expression of survivin and Mcl-1 is associated with inhibition of Stat3 and/or mTOR.

It is known that serine/threonine protein phosphatase 5 (PP5) and 2A (PP2A) are negative regulators of apoptosis signal–regulating kinase 1 (ASK1) and Erk1/2, respectively (47, 48). ASK1 lies upstream of MKK4/7 and MKK3/6, which phosphorylate JNK and p38, respectively (11). Studies have also shown that mTOR positively regulates PP5 (49) and negatively regulates PP2A (22, 50). As CPT inhibits mTOR (9), it remains to be determined whether CPT activates p38/JNK and inhibits Erk1/2 is a consequence of inhibition of mTOR signaling.

In summary, we have shown that CPT induced death of cancer cells, which was not via activation of caspase cascade, but through activation of p38/JNK and inhibition of Erk1/2 pathways, as well as downregulation of antiapoptotic proteins survivin and Mcl-1. The cytotoxic effect of CPT was associated with induction of ROS.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Peter J. Houghton for providing Rh30 cells.

Grant Support

This work was supported in part by NIH (CA115414, to S. Huang), American Cancer Society (RSG-08-135-01-CNE, to S. Huang), National Natural Science Foundation of China (81173174, to Y. Lu; 30801545, to W. Chen), and the 11th Five-Year Plan of China (2008BAI51B02, to Y. Lu).

Footnotes

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Note: Supplementary data for this article are available at Cancer Prevention Research Online (http://cancerprevres.aacrjournals.org/).

References

- 1.Cheng TO. Cardiovascular effects of Danshen. Int J Cardiol. 2007;121:9–22. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2007.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhou L, Zuo Z, Chow MS. Danshen: an overview of its chemistry, pharmacology, pharmacokinetics, and clinical use. J Clin Pharmacol. 2005;45:1345–59. doi: 10.1177/0091270005282630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wojcikowski K, Johnson DW, Gobe G. Herbs or natural substances as complementary therapies for chronic kidney disease: ideas for future studies. J Lab Clin Med. 2006;147:160–6. doi: 10.1016/j.lab.2005.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang BE. Treatment of chronic liver diseases with traditional Chinese medicine. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2000;15(Suppl):E67–70. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1746.2000.02100.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yu XY, Lin SG, Chen X, Zhou ZW, Liang J, Duan W, et al. Transport of cryptotanshinone, a major active triterpenoid in Salvia miltiorrhiza Bunge widely used in the treatment of stroke and Alzheimer’s disease, across the blood-brain barrier. Curr Drug Metab. 2007;8:365–78. doi: 10.2174/138920007780655441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liu J, Shen HM, Ong CN. Salvia miltiorrhiza inhibits cell growth and induces apoptosis in human hepatoma HepG(2) cells. Cancer Lett. 2000;153:85–93. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3835(00)00391-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hung HH, Chen YL, Lin SJ, Yang SP, Shih CC, Shiao MS, et al. A salvianolic acid B-rich fraction of Salvia miltiorrhiza induces neointimal cell apoptosis in rabbit angioplasty model. Histol Histopathol. 2001;16:175–83. doi: 10.14670/HH-16.175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shin DS, Kim HN, Shin KD, Yoon YJ, Kim SJ, Han DC, et al. Cryptotanshinone inhibits constitutive signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 function through blocking the dimerization in DU145 prostate cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2009;69:193–202. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-2575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen W, Luo Y, Liu L, Zhou H, Xu B, Han X, et al. Cryptotanshinone inhibits cancer cell proliferation by suppressing mammalian target of rapamycin-mediated cyclin D1 expression and Rb phosphorylation. Cancer Prev Res. 2010;3:1015–25. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-10-0020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim EK, Choi EJ. Pathological roles of MAPK signaling pathways in human diseases. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2010;1802:396–405. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2009.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wagner EF, Nebreda AR. Signal integration by JNK and p38 MAPK pathways in cancer development. Nat Rev Cancer. 2009;9:537–49. doi: 10.1038/nrc2694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mansouri A, Ridgway LD, Korapati AL, Zhang Q, Tian L, Wang Y, et al. Sustained activation of JNK/p38 MAPK pathways in response to cisplatin leads to Fas ligand induction and cell death in ovarian carcinoma cells. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:19245–56. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M208134200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Park MT, Choi JA, Kim MJ, Um HD, Bae S, Kang CM, et al. Suppression of extracellular signal-related kinase and activation of p38 MAPK are two critical events leading to caspase-8- and mitochondria-mediated cell death in phytosphingosine-treated human cancer cells. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:50624–34. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M309011200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Saldeen J, Lee JC, Welsh N. Role of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (p38 MAPK) in cytokine-induced rat islet cell apoptosis. Biochem Pharmacol. 2001;61:1561–9. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(01)00605-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kumar P, Miller AI, Polverini PJ. p38 MAPK mediates gamma-irradiation-induced endothelial cell apoptosis, and vascular endothelial growth factor protects endothelial cells through the phosphoinositide 3-kinase-Akt-Bcl-2 pathway. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:43352–60. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M405777200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Morrison DK, Davis RJ. Regulation of MAP kinase signaling modules by scaffold proteins in mammals. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2003;19:91–118. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.19.111401.091942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Katz M, Amit I, Yarden Y. Regulation of MAPKs by growth factors and receptor tyrosine kinases. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2007;1773:1161–76. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2007.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Beevers CS, Li F, Liu L, Huang S. Curcumin inhibits the mammalian target of rapamycin-mediated signaling pathways in cancer cells. Int J Cancer. 2006;119:757–64. doi: 10.1002/ijc.21932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhou H, Shen T, Luo Y, Liu L, Chen W, Xu B, et al. The antitumor activity of the fungicide ciclopirox. Int J Cancer. 2010;127:2467–77. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen L, Liu L, Yin J, Luo Y, Huang S. Hydrogen peroxide-induced neuronal apoptosis is associated with inhibition of protein phosphatase 2A and 5, leading to activation of MAPK pathway. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2009;41:1284–95. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2008.10.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chen L, Liu L, Luo Y, Huang S. MAPK and mTOR pathways are involved in cadmium-induced neuronal apoptosis. J Neurochem. 2008;105:251–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2007.05133.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liu L, Chen L, Luo Y, Chen W, Zhou H, Xu B, et al. Rapamycin inhibits IGF-1 stimulated cell motility through PP2A pathway. PLoS One. 2010;5:e10578. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0010578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu L, Chen L, Chung J, Huang S. Rapamycin inhibits F-actin reorganization and phosphorylation of focal adhesion proteins. Oncogene. 2008;27:4998–5010. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pradelli LA, Bénéteau M, Ricci JE. Mitochondrial control of caspase-dependent and -independent cell death. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2010;67:1589–97. doi: 10.1007/s00018-010-0285-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Susin SA, Lorenzo HK, Zamzami N, Marzo I, Snow BE, Brothers GM, et al. Molecular characterization of mitochondrial apoptosis-inducing factor. Nature. 1999;397:441–6. doi: 10.1038/17135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Perfettini JL, Reed JC, Israël N, Martinou JC, Dautry-Varsat A, Ojcius DM. Role of Bcl-2 family members in caspase-independent apoptosis during Chlamydia infection. Infect Immun. 2002;70:55–61. doi: 10.1128/IAI.70.1.55-61.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gabai VL, Yaglom JA, Volloch V, Meriin AB, Force T, Koutroumanis M, et al. Hsp72-mediated suppression of c-Jun N-terminal kinase is implicated in development of tolerance to caspase-independent cell death. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:6826–36. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.18.6826-6836.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liu Y, Templeton DM. Initiation of caspase-independent death in mouse mesangial cells by Cd2+: involvement of p38 kinase and CaMK-II. J Cell Physiol. 2008;217:307–18. doi: 10.1002/jcp.21499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mansour SJ, Matten WT, Hermann AS, Candia JM, Rong S, Fukasawa K, et al. Transformation of mammalian cells by constitutively active MAP kinase kinase. Science. 1994;265:966–70. doi: 10.1126/science.8052857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McCubrey JA, Lahair MM, Franklin RA. Reactive oxygen species-induced activation of the MAP kinase signaling pathways. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2006;8:1775–89. doi: 10.1089/ars.2006.8.1775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pan Y, Bi HC, Zhong GP, Chen X, Zuo Z, Zhao LZ, et al. Pharmaco-kinetic characterization of hydroxylpropyl-beta-cyclodextrin-included complex of cryptotanshinone, an investigational cardiovascular drug purified from Danshen (Salvia miltiorrhiza) Xenobiotica. 2008;38:382–98. doi: 10.1080/00498250701827685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gong Y, Li Y, Lu Y, Li L, Abdolmaleky H, Blackburn GL, et al. Bioactive tanshinones in Salvia miltiorrhiza inhibit the growth of prostate cancer cells in vitro and in mice. Int J Cancer. 2011;129:1042–52. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Don MJ, Liao JF, Lin LY, Chiou WF. Cryptotanshinone inhibits chemotactic migration in macrophages through negative regulation of the PI3K signaling pathway. Br J Pharmacol. 2007;151:638–46. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0707271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tang S, Shen XY, Huang HQ, Xu SW, Yu Y, Zhou CH, et al. Cryptotanshinone suppressed inflammatory cytokines secretion in RAW264.7 macrophages through inhibition of the NF-κB and MAPK signaling pathways. Inflammation. 2011;34:111–8. doi: 10.1007/s10753-010-9214-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Park EJ, Zhao YZ, Kim YC, Sohn DH. PF2401-SF, standardized fraction of Salvia miltiorrhiza and its constituents, tanshinone I, tanshinone IIA, and cryptotanshinone, protect primary cultured rat hepatocytes from bile acid-induced apoptosis by inhibiting JNK phosphorylation. Food Chem Toxicol. 2007;45:1891–8. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2007.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jin YC, Kim CW, Kim YM, Nizamutdinova IT, Ha YM, Kim HJ, et al. Cryptotanshinone, a lipophilic compound of Salvia miltiorrriza root, inhibits TNF-alpha-induced expression of adhesion molecules in HUVEC and attenuates rat myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury in vivo. Eur J Pharmacol. 2009;614:91–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2009.04.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Korkina LG, De Luca C, Kostyuk VA, Pastore S. Plant polyphenols and tumors: from mechanisms to therapies, prevention, and protection against toxicity of anti-cancer treatments. Curr Med Chem. 2009;16:3943–65. doi: 10.2174/092986709789352312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Thayyullathil F, Chathoth S, Hago A, Patel M, Galadari S. Rapid reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation induced by curcumin leads to caspase-dependent and -independent apoptosis in L929 cells. Free Radic Biol Med. 2008;45:1403–12. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2008.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chen Q, Wang Y, Xu K, Lu G, Ying Z, Wu L, et al. Curcumin induces apoptosis in human lung adenocarcinoma A549 cells through a reactive oxygen species-dependent mitochondrial signaling pathway. Oncol Rep. 2010;23:397–403. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chan WH, Wu HJ, Hsuuw YD. Curcumin inhibits ROS formation and apoptosis in methylglyoxal-treated human hepatoma G2 cells. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2005;1042:372–8. doi: 10.1196/annals.1338.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Filomeni G, Graziani I, Rotilio G, Ciriolo MR. Trans-resveratrol induces apoptosis in human breast cancer cells MCF-7 by the activation of MAP kinases pathways. Genes Nutr. 2007;2:295–305. doi: 10.1007/s12263-007-0059-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shin SM, Cho IJ, Kim SG. Resveratrol protects mitochondria against oxidative stress through AMP-activated protein kinase-mediated glycogen synthase kinase-3beta inhibition downstream of poly (ADP-ribose)polymerase-LKB1 pathway. Mol Pharmacol. 2009;76:884–95. doi: 10.1124/mol.109.058479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Choi YJ, Jeong YJ, Lee YJ, Kwon HM, Kang YH. (-)Epigallocatechin gallate and quercetin enhance survival signaling in response to oxidant-induced human endothelial apoptosis. J Nutr. 2005;135:707–13. doi: 10.1093/jn/135.4.707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Coyle CH, Philips BJ, Morrisroe SN, Chancellor MB, Yoshimura N. Antioxidant effects of green tea and its polyphenols on bladder cells. Life Sci. 2008;83:12–8. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2008.04.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Epling-Burnette PK, Liu JH, Catlett-Falcone R, Turkson J, Oshiro M, Kothapalli R, et al. Inhibition of STAT3 signaling leads to apoptosis of leukemic large granular lymphocytes and decreased Mcl-1 expression. J Clin Invest. 2001;107:351–62. doi: 10.1172/JCI9940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Aoki Y, Feldman GM, Tosato G. Inhibition of STAT3 signaling induces apoptosis and decreases survivin expression in primary effusion lymphoma. Blood. 2003;101:1535–42. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-07-2130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Morita K, Saitoh M, Tobiume K, Matsuura H, Enomoto S, Nishitoh H, et al. Negative feedback regulation of ASK1 by protein phosphatase 5 (PP5) in response to oxidative stress. EMBO J. 2001;20:6028–36. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.21.6028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kins S, Kurosinski P, Nitsch RM, Götz J. Activation of the ERK and JNK signaling pathways caused by neuron-specific inhibition of PP2A in transgenic mice. Am J Pathol. 2003;163:833–43. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63444-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Huang S, Shu L, Easton J, Harwood FC, Germain GS, Ichijo H, et al. Inhibition of mammalian target of rapamycin activates apoptosis signal-regulating kinase 1 signaling by suppressing protein phosphatase 5 activity. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:36490–6. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M401208200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Harwood FC, Shu L, Houghton PJ. mTORC1 signaling can regulate growth factor activation of p44/42 mitogen-activated protein kinases through protein phosphatase 2A. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:2575–85. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M706173200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.