Abstract

Background

Approximately 10% of new breast cancer patients will present with overt synchronous metastatic disease. The optimal local management of those patients is controversial. Several series suggest that removal of the primary tumour is associated with a survival benefit, but the retrospective nature of those studies raises considerable methodologic challenges. We evaluated our clinical experience with the management of such patients and, more specifically, the impact of surgery in patients with synchronous metastasis.

Methods

We reviewed patients with primary breast cancer and concurrent distant metastases seen at our centre between 2005 and 2007. Demographic and treatment data were collected. Study endpoints included overall survival and symptomatic local progression rates.

Results

The 111 patients identified had a median follow-up of 40 months (range: 0.6–71 months). We allocated the patients to one ot two groups: a nonsurgical group (those who did not have breast surgery, n = 63) and a surgical group (those who did have surgery, n = 48, 29 of whom had surgery before the metastatic diagnosis). When compared with patients in the nonsurgical group, patients in the surgical group were less likely to present with T4 tumours (23% vs. 35%), N3 nodal disease (8% vs. 19%), and visceral metastasis (67% vs. 73%). Patients in the surgical group experienced longer overall survival (49 months vs. 33 months, p = 0.01) and lower rates of symptomatic local progression (14% vs. 44%, p < 0.001).

Conclusions

In our study, improved overall survival and symptomatic local control were demonstrated in the surgically treated patients; however, this group had less aggressive disease at presentation. The optimal local management of patients with metastatic breast cancer remains unknown. An ongoing phase iii trial, E2108, has been designed to assess the effect of breast surgery in metastatic patients responding to first-line systemic therapy. If excision of the primary tumour is associated with a survival benefit, then the preselected subgroup of patients who have responded to initial systemic therapy is the desired population in which to put this hypothesis to the test.

Keywords: Metastatic breast cancer, surgery, local excision

1. INTRODUCTION

About 3.5%–10% of patients with newly diagnosed breast cancer present with concurrent metastatic disease1. Given that the 5-year survival for this group of patients is approximately 20%, management has tended to focus on palliative systemic therapy2,3. Locoregional treatments to the breast and axilla have usually been reserved for palliating symptomatic local disease, because the perception has been that survival depends on the metastatic disease burden and not on local therapy2,3.

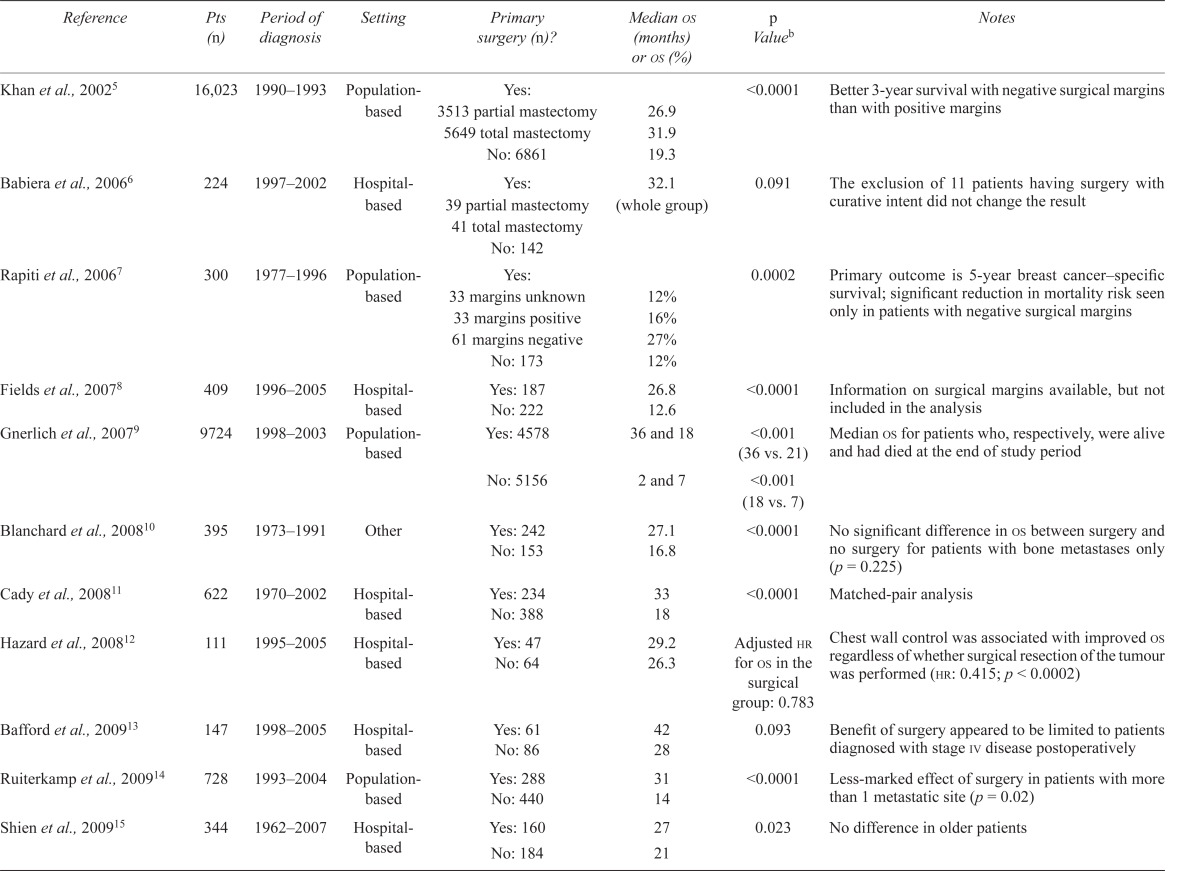

Multiple case studies and several meta-analyses have reviewed the association of local therapy with improved overall survival. Those studies (Table i) have suggested that combined multimodality therapy—surgery, radiotherapy, and systemic therapy—may provide a survival advantage in this patient population5–16,20,23,25,26, but the strength of the studies has been hampered by their retrospective nature. Confounding factors in these trials include timing of the primary surgery (before or after the radiologic staging that showed metastatic disease), hormone and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (her2) status, metastatic burden, type and timing of systemic therapy, sites of metastases (visceral or bone only), and performance status. In most series, it appears that surgical removal of the primary breast tumour was performed mainly in patients with oligometastases, who responded to systemic therapy, and who had a good performance status with no visceral metastases6,7,10,12,15. Even in the absence of an overall survival benefit, breast surgery may reduce the incidence of uncontrolled local disease12,25, which can include skin ulceration, discharge, pain, discomfort, and bleeding.

TABLE I.

Univariate analyses of the association between surgical removal of a primary tumour and median survival in patients with stage iv breast cancera

| Reference | Pts (n) | Period of diagnosis | Setting | Primary surgery (n)? | Median os (months) or os (%) | p Valueb | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Khan et al., 20025 | 16,023 | 1990–1993 | Population-based | Yes: | <0.0001 | Better 3-year survival with negative surgical margins than with positive margins | |

| 3513 partial mastectomy | 26.9 | ||||||

| 5649 total mastectomy | 31.9 | ||||||

| No: 6861 | 19.3 | ||||||

| Babiera et al., 20066 | 224 | 1997–2002 | Hospital-based | Yes: 39 partial mastectomy 41 total mastectomy No: 142 |

32.1 (whole group) | 0.091 | The exclusion of 11 patients having surgery with curative intent did not change the result |

| Rapiti et al., 20067 | 300 | 1977–1996 | Population-based | Yes: | 0.0002 | Primary outcome is 5-year breast cancer–specific survival; significant reduction in mortality risk seen only in patients with negative surgical margins | |

| 33 margins unknown | 12% | ||||||

| 33 margins positive | 16% | ||||||

| 61 margins negative | 27% | ||||||

| No: 173 | 12% | ||||||

| Fields et al., 20078 | 409 | 1996–2005 | Hospital-based | Yes: 187 | 26.8 | <0.0001 | Information on surgical margins available, but not included in the analysis |

| No: 222 | 12.6 | ||||||

| Gnerlich et al., 20079 | 9724 | 1998–2003 | Population-based | Yes: 4578 | 36 and 18 | <0.001 (36 vs. 21) | Median os for patients who, respectively, were alive and had died at the end of study period |

| No: 5156 | 2 and 7 | <0.001 (18 vs. 7) | |||||

| Blanchard et al., 200810 | 395 | 1973–1991 | Other | Yes: 242 | 27.1 | <0.0001 | No significant difference in os between surgery and no surgery for patients with bone metastases only (p = 0.225) |

| No: 153 | 16.8 | ||||||

| Cady et al., 200811 | 622 | 1970–2002 | Hospital-based | Yes: 234 | 33 | <0.0001 | Matched-pair analysis |

| No: 388 | 18 | ||||||

| Hazard et al., 200812 | 111 | 1995–2005 | Hospital-based | Yes: 47 | 29.2 | Adjusted hr for os in the surgical group: 0.783 | Chest wall control was associated with improved os regardless of whether surgical resection of the tumour was performed (hr: 0.415; p < 0.0002) |

| No: 64 | 26.3 | ||||||

| Bafford et al., 200913 | 147 | 1998–2005 | Hospital-based | Yes: 61 | 42 | 0.093 | Benefit of surgery appeared to be limited to patients diagnosed with stage iv disease postoperatively |

| No: 86 | 28 | ||||||

| Ruiterkamp et al., 200914 | 728 | 1993–2004 | Population-based | Yes: 288 | 31 | <0.0001 | Less-marked effect of surgery in patients with more than 1 metastatic site (p = 0.02) |

| No: 440 | 14 | ||||||

| Shien et al., 200915 | 344 | 1962–2007 | Hospital-based | Yes: 160 | 27 | 0.023 | No difference in older patients |

| No: 184 | 21 | ||||||

| Leung et al., 201016 | 157 | 1990–2000 | Hospital-based | Yes: 52 | 25 | 0.06 (log-rank) | Small patient series |

| No: 105 | 13 | 0.004 (Wilcoxon) | |||||

| Ly et al., 201017 | 8761 | 1988–2003 | Population-based | No: 3905 | 14 | <0.0001 | Assessment of role of radiation; radiation was beneficial in all three groups |

| Yes: 2070 bcs | 23 | ||||||

| 2786 mastectomy | 28 | ||||||

| Dominici et al., 201118 | 551 | 1997–2007 | Population-based (nccn) | Yes: 236 | 40.8 | 0.34 (ns) | Cases were matched in the two groups |

| No: 54 | 42 | ||||||

| Pathy et al., 201119 | 375 | 1993–2008 | Hospital-based | Yes: 139 | 21.2 | hr: 0.72 95% ci: 0.56 to 0.94 | Numbers are for 2-year survival; study from Malaysia; tumour diameter at diagnosis is generally larger than in other studies, and so a high proportion have locally advanced tumours and multiple metastases; propensity score method was used and surgery remained significantly associated with better survival |

| No: 236 | 46.3 | ||||||

| Pérez–Fidalgo et al., 201120 | 208 | 1982–2005 | Hospital-based | Yes: 123 | 40.4 | 0.001 | Study from Spain; significant benefit of surgery mainly in patients with visceral disease (p = 0.005); no statistical differences in those with bone disease (p = 0.79) |

| No: 85 | 24.3 | ||||||

| Rosche et al., 201121 (abstract) | 61 | 1986–2007 | Hospital-based | Yes: 35 | Not mentioned | na | Small number of patients; abstract available in English; no difference in os and progression-free survival between the groups |

| No: 26 | |||||||

| Shibasaki et al., 201122 (abstract) | 92 | Not mentioned | Hospital-based | Yes: 36 | 25 | 0.352 (ns) | Study from Japan; no difference in os; all tumours larger than 5 cm; better symptom control with surgery |

| No: 54 | 24.8 | ||||||

| Sofi et al., 201123 | 186 | 2000–2004 | Institution-based | Yes: 69 | 40 | 0.004 | Significant only in non-triple-negative patients |

| No: 117 | 33 | ||||||

| Rashaan et al., 201224 | 171 | 1989–2009 | Hospital-based | Yes: 59 | hr: 0.6; 95% ci: 0.4 to 0.9 | 0.02 | In 21 patients of the surgical group, the surgery occurred before detection of metastasis; not statistically significant in multivariate analysis (hr: 0.9; 95% ci: 0.6 to 1.4; p = 0.5).; in multivariate analyses, younger patients and patients without comorbidity that underwent surgery experienced increased survival |

| No: 112 |

Adapted and updated from Ruiterkamp et al.4, with permission.

Surgery versus no surgery.

Pts = patients; os = overall survival; hr = hazard ratio; bcs = breast-conserving surgery; nccn = National Comprehensive Cancer Network; ci = confidence interval; na = not available; ns = nonsignificant.

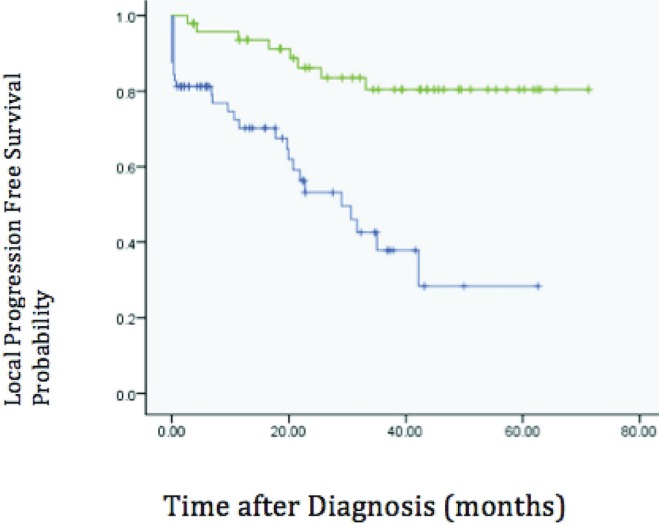

Two retrospective studies (Table ii) correlated surgery and prevention of uncontrolled chest wall disease in metastatic breast cancer. Carmichael et al.25 reviewed 20 patients with metastatic breast cancer who all underwent resection of the primary tumour. Only 3 patients developed local disease progression. In 111 patients, Hazard et al. reported a significant difference in local control of disease associated with surgical resection of the primary tumour (82% in the surgical group vs. 34% in the nonsurgical group; hazard ratio: 0.415; p < 0.0002)12.

TABLE II.

Reviews of the association between surgical removal of a primary tumour and local control in metastatic breast cancer

| Reference | Pts (n) | Period of diagnosis | Setting | Primary surgery (n)? | pfs | p Valueb | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hazard et al., 200812 | 111 | 1995–2005 | Hospital-based | Yes: 47 | 34% | 0.002 | Chest wall control was associated with improved os regardless of whether surgical resection of the tumour was performed (hr: 0.415; p < 0.0002) |

| No: 64 | 82% | ||||||

| Carmichael et al., 200325 | 20 | 1993–1999 | Hospital-based | 20 | 85% at last follow-up | na | Single arm; retrospective; median follow-up: 20 months |

Pts = patients; pfs = progression-free survival; os = overall survival; hr = hazard ratio; na = not available.

To date, very few prospective trials have addressed the role of surgery in metastatic breast cancer (Table iii). Recently, the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group initiated a prospective randomized trial (E2108) of surgery in patients presenting with stage iv breast cancer. Patients responding to initial systemic therapy are being randomized to either continuing systemic therapy (with surgery or radiotherapy, or both, for locoregional complications) or to local surgery and radiotherapy. The primary endpoint of the study is survival; a large number of secondary clinical and biologic endpoints are also being evaluated.

TABLE III.

Current ongoing prospective trials assessing the role of surgery in stage iv breast cancer

| Trial ID at ClinicalTrials.gov | Name of trial | Centre | Start date | Expected end date | Type | Arms |

Outcomes

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary | Secondary | |||||||

| NCT00941759 | Analysis of Surgery in Patients Presenting with Stage IV Breast Cancer | Memorial Sloan–Kettering Cancer Center | Jul 2009 | Jul 2012 | Prospective | Single-arm | Response to first line therapy | Incidence of uncontrolled local disease Circulating tumour cells Correlations between molecular characteristics of the primary tumour and conventional prognostic factors and survival |

| NCT01242800 | Early Surgery or Standard Palliative Therapy in Treating Patients with Stage IV Breast Cancer | Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group | Feb 2011 | Feb 2014 | Prospective randomized trial | Conventional palliative surgery or radiation vs. therapeutic surgery and radiation | Survival | Local control Quality of life Circulating tumour cells and overall survival Biologic interactions between the primary tumour and metastatic lesions |

| NCT00193778 | Assessing Impact of Loco-regional Treatment on Survival in Metastatic Breast Cancer at Presentation | Tata Memorial University | Feb 2005 | Jun 2012 | Prospective randomized trial | Primary surgery or no local surgery after chemotherapy | Time to progression and death | Vascular endothelial growth factor and basic fibroblast growth factor as potential markers responsive to primary control |

| NCT00557986 | Local Surgery for Metastatic Breast Cancer | Istanbul University | Nov 2007 | Jun 2012 | Prospective randomized trial | Surgery vs. no surgery | Mortality | Quality of life |

Given that local control in metastatic breast cancer remains an important unanswered question, we evaluated our clinical experience in managing such patients, and more specifically, we determined the impact of surgery on overall survival and symptomatic local progression rates in patients with synchronous metastasis.

2. METHODS

Our retrospective study investigated the role of surgical resection in the treatment of patients presenting with metastatic breast cancer. After ethics approval by the Institutional Review Board, the Ottawa Cancer Centre database (Metriq) was queried for women presenting with metastasis at the time of diagnosis at the Centre between 2005 and 2007. Medical records were reviewed for age at diagnosis, laterality, histology of the tumour, clinical and pathologic size of the primary tumour, lymph node status, hormone receptor status, her2 overexpression, location and number of metastases, mode and date of surgical treatment, margin status, use of radiotherapy, systemic therapy, time to local progression, and local disease status at the time of diagnosis, the time of death, or the time of last contact.

The patients were divided into two groups. Those who did not undergo surgical resection of the primary tumour were allocated to the nonsurgical group, and those who underwent resection of the primary tumour at some time after diagnosis were allocated to the surgical group. Metastases in these patients were detected either before surgery or after surgery during routine postoperative radiologic staging.

“Local progression” (also called “absence of local control”) was defined as follows:

Any asymptomatic primary tumour, breast, axilla, or chest wall that at some point in time became symptomatic (redness, pain, discomfort, skin dimpling, ulceration, and so on)

Any symptomatic primary tumour, breast, axilla, or chest wall that was controlled by therapy (systemic or local) but that later progressed

Any symptomatic primary tumour, breast, axilla, or chest wall that was never controlled by any therapy (systemic, local) and that kept progressing

The date of local progression was the first date at which the physician observed and documented the local disease.

2.1. Statistical Analysis

The SPSS software application (SPSS, Chicago, IL, U.S.A.) was used for all statistical analyses. Baseline characteristics were not matched between the two groups. We therefore used the Pearson chi-square test to compare the previously noted prognostic factors in overall survival and local progression (including hormone receptor and her2 status and tumour and nodal stage) between the groups. Cox proportional hazards models were used to evaluate the associations of surgery with the overall survival and time to local progressive disease outcomes. Kaplan–Meier plots were used to demonstrate the differences in time to local progression and survival stratified by surgical treatment status. The endpoints in data analysis were also stratified by surgical treatment status. The endpoint for overall survival was death, and for local disease progression, it was local disease progression–free survival. Because of their previously noted association with survival, potentially confounding factors, including resectability at presentation, hormone receptor and her2 status, and presence of visceral metastasis, were compared between the groups in the multivariate analyses27,28.

3. RESULTS

Between 2005 and 2007, 111 women (average age: 63 years) presented with either stage iv disease or with metastatic disease at the time of postoperative staging (nonsurgical group: 63 patients, average age 64 years; surgical group: 48 patients, average age 61 years). The median follow-up in the entire population was 40 months (range: 0.6–71 months). Table iv shows the clinical characteristics of the patients.

TABLE IV.

Baseline patient characteristics

| Characteristic |

Group

|

p Valuea | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nonsurgical | Surgical | Overall | ||

| Patients (n) | 63 | 48 | 111 | |

| Age at diagnosis (years) | ||||

| Mean | 64 | 61 | 63 | 0.196 |

| Range | 28–89 | 35–88 | 28–89 | |

| Tumour stage [% (n)] | ||||

| T4b | 35 (22) | 23 (11) | 29 (32) | 0.15 |

| T3b | 19 (12) | 29 (14) | 23 (26) | 0.42 |

| TX, 1 and 2b | 44 (28) | 52 (25) | 48 (53) | 0.69 |

| Nodal status [% (n)] | ||||

| N3b | 19 (12) | 8 (4) | 14 (16) | 0.123 |

| N2 | 14 (9) | 21 (10) | 17 (19) | 0.51 |

| N1 | 22 (14) | 29 (14) | 25 (28) | 0.54 |

| N0 | 38 (24) | 40 (19) | 39 (43) | 0.90 |

| hr-positive | 76 (48) | 73 (35) | 75 (83) | 0.26 |

| her2-positive | 13 (8) | 29 (14) | 20 (22) | 0.06 |

| Triple-negative | 9 (6) | 10 (5) | 10 (11) | 0.67 |

| Metastasis [% (n)] | ||||

| Visceral | 73 (46) | 67 (32) | 70 (78) | 0.46 |

| Bone only | 24 (15) | 29 (14) | 26 (29) | 0.52 |

| Brain | 13 (8) | 8 (4) | 11 (12) | 0.46 |

Nonsurgical group compared with surgical group.

Clinical T or N.

hr = hormone receptor; her2 = human epidermal growth factor receptor 2.

All but 6 patients (5 in the nonsurgical group, 1 in the surgical group) received systemic therapy in form of either hormonal therapy or chemotherapy. In the nonsurgical group, 17.4% of patients received 3 or more regimens of chemotherapy; in the surgical group, 40.7% received 3 or more regimens. In the nonsurgical group, 23% of patients received more than 2 lines of endocrine therapy; in the surgical group, 25% received such therapy.

Of the 48 patients in the surgical group, 29 underwent their surgery before the diagnosis of metastasis—that is, disease was discovered during postoperative radiologic staging. Patients in the nonsurgical group were more likely to have larger tumours with skin involvement and visceral metastasis. The proportion of patients who presented with T4 tumours was 35% (22 of 63) in the nonsurgical group and 23% (11 of 48) in the surgical group. N3 disease was found in 12 patients (19%) in the nonsurgical group and in 4 patients (8%) in the surgical group. The pattern of metastases was found to be different in the two groups. Visceral metastases were diagnosed in 73% of patients (46 of 63) in the nonsurgical group and in 67% of patients (32 of 48) in the surgical group. The percentage of patients who had brain metastasis at the time of diagnosis was 13% (8 of 63 nonsurgical patients) and 8% (4 of 48 surgical patients). Using the Pearson chi-square test, none of the differences was statistically significant, a result that probably reflects the small sample size.

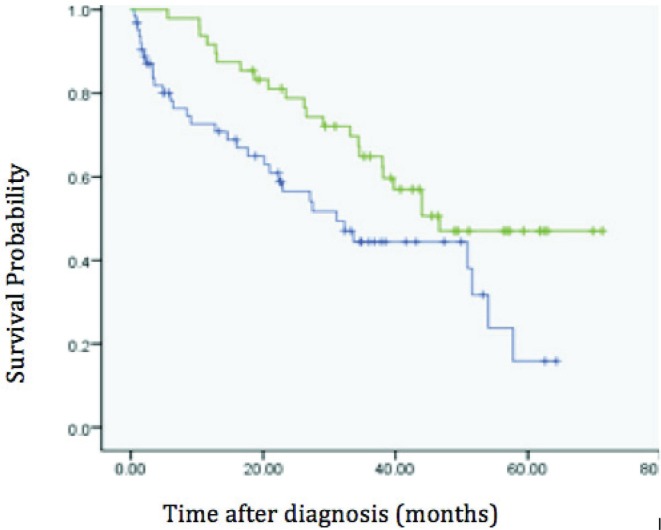

The mean overall survival was 33 months (95% confidence interval: 26–39 months) in the nonsurgical group and 49 months (95% confidence interval: 41–55 months) in the surgical group (p = 0.016, Figure 1). Local progression occurred in 44% of patients (28 of 63) in the nonsurgical group and in 14% of patients (7 of 48) in the surgical group (p < 0.001, Figure 2). When the primary tumour progressed locally, systemic therapy was able to control local disease in only 2 cases.

FIGURE 1.

Kaplan–Meier curves of overall survival in the surgery (green) and no-surgery (blue) groups.

FIGURE 2.

Kaplan–Meier curves of progression-free survival in the surgery (green) and no-surgery (blue) groups.

To control other covariates for overall survival, a multivariate analysis using the Cox proportional hazards model was applied. Hormone receptor and her2 status and the presence of visceral metastasis were prognostic factors included in the equation to compare overall survival between two groups. After correcting for those factors, the surgery group had a statistically significantly better survival. Positive hormone receptor status and surgical resection were both associated with better survival, p < 0.001 and p = 0.041 respectively.

To control for locally advanced tumour stage at diagnosis (T4) and for progression of local disease, a multivariate analysis using the Cox proportional hazards model was applied. In the multivariate equation, surgery and a potentially resectable tumour at presentation were both associated with significantly better local progression–free survival, p < 0.001 and p < 0.001 respectively. In patients who underwent surgical treatment for the primary tumour, mean overall survival was not different between the groups that had surgery before and after the diagnosis of metastasis (mean survival: 50 months vs. 42.5 months, p = 0.47)

4. DISCUSSION

The optimal management of stage iv breast cancer is unknown, and thus there is no consensus about the value of surgery in the management of this population. A clinician and a patient may consider surgical resection of the primary tumour in this setting for multiple reasons29.

The effect of resection of the primary tumour in metastatic breast cancer patients can be divided into two main areas: the effect of surgery on overall survival and its effect on local disease control.

There is some evidence that surgery may be associated with improved overall survival6–16,20,23,25,26. However little is known about the effect of surgery and uncontrolled local disease in metastatic breast cancer. Hazard et al.12 showed that surgery was associated with better local control and that chest wall control was associated with improved overall survival regardless of whether surgical resection of the tumour was performed (hazard ratio: 0.415; p < 0.0002). Carmichael and colleagues25 reviewed 20 selected patients with metastatic breast cancer who underwent surgical resection of a primary tumour. After 20 months of follow-up, only 3 patients had developed local disease progression. The foregoing studies concluded that local surgery has a role in controlling local disease in selected patients with metastatic breast cancer.

The biologic perspective and evidence regarding interactions between the primary tumour and foci of metastasis are extensive and complex. The literature suggests that complex and bi-directional interactions occur between the primary tumour and metastatic foci. A comprehensive review of those interactions is outside of scope of the present study, but some publications suggest that resection of the primary tumour might enhance the growth of metastatic disease30,31 because of induction of angiogenesis in dormant distant micrometastatic foci as a result of the surgical resection32. The theory is that removal of the primary induces growth factor production because the primary tumour was producing angiogenesis inhibitors33–38. Alternatively, other hypotheses suggest that resection of the primary tumour may reduce the risk of metastasis growth. In theory, the primary tumour acts as a “seed source” for the development of new metastases, and its resection could potentially lower the chances of further progression5,29,39. Another hypothesis is that resection of primary tumour reduces the burden of disease and potentially makes chemotherapy more effective29. There is also a counterargument that removing a primary tumour can promote cancer cell proliferation by suppressing cell-mediated immunity40. Self-seeding is another new concept that explains the active role of primary tumour not only in a unidirectional system as a source of metastasis, but also as a location from which metastatic cells might seed back and regrow (reviewed in Comen et al.41). Based on the latter theory, circulating metastatic cells also contribute to primary tumour growth42. The idea is that cellular seeds might spread from the tumour, forming a metastatic site, but might also be capable of returning to the primary and inducing new metastases42.

Our study compared the rates of local disease progression in patients who underwent surgical resection of the primary tumour and in those who did not. Local progression occurred in 44% of patients in the nonsurgical group and in 14% of patients in the surgical group (p < 0.001). However, characteristics of patients in the two groups were not homogenous. Locally advanced tumours (T4 or N3) were more common in the nonsurgical group than in the surgical one (T4: 35% vs. 23%; N3: 19% vs. 8%). Our results suggest that surgery might have a role in prevention of local disease progression in a selected group of patients. That hypothesis needs to be further validated and defined by a prospective randomized study.

Any correlation between resection of the primary tumour and overall survival in metastatic breast cancer patients remains unclear. Multiple retrospective studies from single institutions and population-based series have demonstrated improved survival in women diagnosed with metastatic breast cancer who undergo surgery for an intact primary tumour (Table i)6–16,20,23,25,26.

Our study also showed that survival was improved in the surgical group compared with the non-surgical group (49 months vs. 33 months, p = 0.01). However, two studies also showed no survival benefit in this population18,19,21,22. From the series showing a survival benefit associated with surgery, the patients selected by physicians for surgical removal of the primary tumour are observed usually to have a lower burden of systemic disease, a lesser likelihood of visceral metastasis, or smaller tumours6,12. In one study, 74% of the patients in the surgical group had only 1 site of metastasis, but only 53% of the patients in the nonsurgical group had just 1 site12. The observed association between surgery and improved survival may be reflective of an inherent bias of surgeons to operate on patients with less-extensive disease and better performance status. However, that assumption is not always the case. In a recent retrospective review from Malaysia, Pathy et al. observed a beneficial effect of surgical resection of the primary tumour in a cohort of patients who predominantly had locally advanced disease19. About 80% of all the patients presented with T4 disease in that study (81.8% in the non-surgery group and 77% in the surgery group)19.

In another retrospective population-based study, Ly et al. studied the effect of local therapy (surgery and radiation) on survival in 8761 patients. They found a significant survival benefit with surgical treatment or radiotherapy, or both, to the primary site. However, their report showed that some poor tumour characteristics such as hormone receptor negativity and high histologic grade were more frequent in the surgical patients (estrogen receptor– negative and histologic grades 3 and 4: 18% and 37% in the nonsurgical group, 21% and 46% in the breast-conserving surgery group, and 23% and 52% in the mastectomy group)17. This variability between studies is important and can only be resolved by a randomized prospective study.

Parmar et al. reported interim results of a prospective randomized study (NCT00193778)43. This in-progress prospective randomized controlled trial is one of those (Table iii) addressing the effect of surgical resection of primary tumour in stage iv breast cancer. At the time of publication, 125 women had been recruited. The authors reported no statistically significant differences between the surgery and the observation groups in either progression-free survival or overall survival. Indeed, they reported that survival was worse in the surgical group (42.9% vs. 58.5%, p = 0.97). Importantly, however, to detect even a 10% advantage in 3-year survival in patients undergoing surgical resection of the primary tumour, a study involving about 700 patients would be required44. Among the ongoing prospective trials, only the E2108 trial may be powered to detect such a small level of improvement; the target population size in that study is 800 patients.

In the present study, 29 of 48 patients who underwent surgery were diagnosed with metastatic disease just after surgery during postoperative staging. In that group (that is, more than half the entire surgical group), the bias might favour surgery being performed on those who present with nonsymptomatic metastatic disease, with potentially curative intent. However, our review shows no statistically significant difference in overall survival between the patients who had surgery before and after a diagnosis of metastasis.

Also in the present study, the mean overall survival was significantly lower in the nonsurgical group than in the surgical one (33 months vs. 49 months, p = 0.01). After controlling for prognostic factors such as hormone status and visceral metastasis, overall survival was still significantly different between the groups. The inherent bias of a retrospective study may not be completely overcome by a multivariate analysis. Without a prospective randomized clinical trial, the role of surgery in stage iv patients cannot be fully evaluated, demonstrating the importance of supporting randomized controlled trials such as E2108.

5. CONCLUSIONS

The optimal management of local disease in patients with metastatic breast cancer remains unknown. In the present study, improved overall survival and improved symptomatic local control were observed in a group of patients who underwent surgery. However, that group also appeared to present with less-aggressive disease. Given the considerable limitations of retrospective studies (ours and others), it is imperative that support be given to prospective studies such as the ongoing phase iii clinical trial E2108. If excision of the primary tumour is associated with a survival benefit, then the preselected subgroup of patients who have responded to initial systemic therapy may be exactly the desired population to put the hypothesis to the test.

6. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful for donations from the patrons of The Fall River Restaurant and funds raised in loving memory of Camilla D’Amours that permitted our study to be performed.

7. CONFLICT OF INTEREST DISCLOSURES

The authors have no financial conflicts of interest to declare.

8. REFERENCES

- 1.Sant M, Allemani C, Berrino F, et al. Breast carcinoma survival in Europe and the United States. Cancer. 2004;100:715–22. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ellis MJ, Hayes DF, Lippman ME. Treatment of metastatic breast cancer. In: Harris JR, Lippman ME, Morrow M, Osborne K, editors. Diseases of the Breast. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2000. pp. 749–97. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wood WC, Muss HB, Solin LJ, Olopade OI. Malignant tumours of the breast. In: DeVita VT Jr, Hellman S, Rosenberg SA, editors. Cancer Principles and Practice of Oncology. 7th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2005. pp. 1415–78. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ruiterkamp J, Voogd AC, Bosscha K, Tjan–Heijnen VC, Ernst MF. Impact of breast surgery on survival in patients with distant metastases at initial presentation: a systematic review of the literature. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2010;120:9–16. doi: 10.1007/s10549-009-0670-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Khan SA, Stewart AK, Morrow M. Does aggressive local therapy improve survival in metastatic breast cancer. Surgery. 2002;132:620–6. doi: 10.1067/msy.2002.127544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Babiera GV, Rao R, Feng L, et al. Effect of primary tumour extirpation in breast cancer patients who present with stage iv disease and an intact primary tumour. Ann Surg Oncol. 2006;13:776–82. doi: 10.1245/ASO.2006.03.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rapiti E, Verkooijen HM, Vlastos G, et al. Complete surgical excision of primary breast tumour improves survival of patients with metastatic breast cancer at diagnosis. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:2743–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.04.2226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fields RC, Jeffe DB, Trinkaus K, et al. Surgical resection of the primary tumour is associated with increased long-term survival in patients with stage iv breast cancer after controlling for site of metastasis. Ann Surg Oncol. 2007;14:3345–51. doi: 10.1245/s10434-007-9527-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gnerlich J, Jeffe DB, Deshpande AD, Beers C, Zander C, Margenthaler JA. Surgical removal of the primary tumour increases overall survival in patients with metastatic breast cancer: analysis of the 1988–2003 seer data. Ann Surg Oncol. 2007;14:2187–94. doi: 10.1245/s10434-007-9438-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Blanchard DK, Shetty PB, Hilsenbeck SG, Elledge RM. Association of surgery with improved survival in stage iv breast cancer patients. Ann Surg. 2008;247:732–8. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181656d32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cady B, Nathan NR, Michaelson JS, Golshan M, Smith BL. Matched pair analyses of stage iv breast cancer with or without resection of primary breast site. Ann Surg Oncol. 2008;15:3384–95. doi: 10.1245/s10434-008-0085-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hazard HW, Gorla SR, Scholtens D, Kiel K, Gradishar WJ, Khan SA. Surgical resection of the primary tumour, chest wall control, and survival in women with metastatic breast cancer. Cancer. 2008;113:2011–19. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bafford AC, Burstein HJ, Barkley CR, et al. Breast surgery in stage iv breast cancer: impact of staging and patient selection on overall survival. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2009;115:7–12. doi: 10.1007/s10549-008-0101-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ruiterkamp J, Ernst MF, van de Poll–Franse LV, Bosscha K, Tjan–Heijnen VC, Voogd AC. Surgical resection of the primary tumour is associated with improved survival in patients with distant metastatic breast cancer at diagnosis. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2009;35:1146–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2009.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shien T, Kinoshita T, Shimizu C, et al. Primary tumor resection improves the survival of younger patients with metastatic breast cancer. Oncol Rep. 2009;21:827–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Leung AM, Vu HN, Nguyen KA, Thacker LR, Bear HD. Effects of surgical excision on survival of patients with stage iv breast cancer. J Surg Res. 2010;161:83–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2008.12.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ly BH, Vlastos G, Rapiti E, Vinh–Hung V, Nguyen NP. Local–regional radiotherapy and surgery is associated with a significant survival advantage in metastatic breast cancer patients. Tumori. 2010;96:947–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dominici L, Najita J, Hughes M, et al. Surgery of the primary tumor does not improve survival in stage iv breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2011;129:459–65. doi: 10.1007/s10549-011-1648-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pathy NB, Verkooijen HM, Taib NA, Hartman M, Yip CH. Impact of breast surgery on survival in women presenting with metastatic breast cancer. Br J Surg. 2011;98:1566–72. doi: 10.1002/bjs.7650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pérez–Fidalgo JA, Pimentel P, Caballero A, et al. Removal of primary tumor improves survival in metastatic breast cancer. Does timing of surgery influence outcomes? Breast. 2011;20:548–54. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2011.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rosche M, Regierer AC, Schwarzlose–Schwarck S, et al. Primary tumor excision in stage iv breast cancer at diagnosis without influence on survival: a retrospective analysis and review of the literature. Onkologie. 2011;34:607–12. doi: 10.1159/000334061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shibasaki S, Jotoku H, Watanabe K, Takahashi M. Does primary tumor resection improve outcomes for patients with incurable advanced breast cancer? Breast. 2011;20:543–7. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2011.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sofi AA, Mohamed I, Koumaya M, Kamaluddin Z. Local therapy in metastatic breast cancer is associated with improved survival. Am J Ther. 2011. [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Rashaan ZM, Bastiaannet E, Portielje JE, et al. Surgery in metastatic breast cancer: patients with a favorable profile seem to have the most benefit from surgery. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2012;38:52–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2011.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Carmichael AR, Anderson ED, Chetty U, Dixon JM. Does local surgery have a role in the management of stage iv breast cancer? Eur J Surg Oncol. 2003;29:17–19. doi: 10.1053/ejso.2002.1339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Neuman HB, Morrogh M, Gonen M, Van Zee KJ, Morrow M, King TA. Stage iv breast cancer in the era of targeted therapy: does surgery of the primary tumor matter? Cancer. 2010;116:1226–33. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Falkson G, Holcroft C, Gelman RS, Tormey DC, Wolter JM, Cummings FJ. Ten-year follow-up study of premenopausal women with metastatic breast cancer: an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group study. J Clin Oncol. 1995;13:1453–8. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1995.13.6.1453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rao R, Feng L, Kuerer HM, et al. Timing of surgical intervention for the intact primary in stage iv breast cancer patients. Ann Surg Oncol. 2008;15:1696–702. doi: 10.1245/s10434-008-9830-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pockaj BA, Wasif N, Dueck AC, et al. Metastasectomy and surgical resection of the primary tumor in patients with stage iv breast cancer: time for a second look? Ann Surg Oncol. 2010;17:2419–26. doi: 10.1245/s10434-010-1016-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gunduz N, Fisher B, Saffer EA. Effect of surgical removal on the growth and kinetics of residual tumor. Cancer Res. 1979;39:3861–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fisher B, Gunduz N, Saffer EA. Influence of the interval between primary tumor removal and chemotherapy on kinetics and growth of metastases. Cancer Res. 1983;43:1488–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Retsky M, Bonadonna G, Demicheli R, Folkman J, Hrushesky W, Valagussa P. Hypothesis: induced angiogenesis after surgery in premenopausal node-positive breast cancer patients is a major underlying reason why adjuvant chemotherapy works particularly well for those patients. Breast Cancer Res. 2004;6:R372–4. doi: 10.1186/bcr804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.O’Reilly MS, Holmgren L, Shing Y, et al. Angiostatin: a novel angiogenesis inhibitor that mediates the suppression of metastases by a Lewis lung carcinoma. Cell. 1994;79:315–28. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90200-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hofer SO, Molema G, Hermens RA, Wanebo HJ, Reichner JS, Hoekstra HJ. The effect of surgical wounding on tumour development. Eur J Surg Oncol. 1999;25:231–43. doi: 10.1053/ejso.1998.0634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Retsky MW, Demicheli R, Hrushesky WJ, Baum M, Gukas ID. Dormancy and surgery-driven escape from dormancy help explain some clinical features of breast cancer. APMIS. 2008;116:730–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0463.2008.00990.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Demicheli R, Retsky MW, Hrushesky WJ, Baum M. Tumor dormancy and surgery-driven interruption of dormancy in breast cancer: learning from failures. Nat Clin Pract Oncol. 2007;4:699–710. doi: 10.1038/ncponc0999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Brackstone M, Townson JL, Chambers AF. Tumour dormancy in breast cancer: an update. Breast Cancer Res. 2007;9:208. doi: 10.1186/bcr1677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Baum M, Demicheli R, Hrushesky W, Retsky M. Does surgery unfavourably perturb the “natural history” of early breast cancer by accelerating the appearance of distant metastases? Eur J Cancer. 2005;41:508–15. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2004.09.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Perez CB, Khan SA. Local therapy for the primary breast tumor in women with metastatic disease. Clin Adv Hematol Oncol. 2011;9:112–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Goldstein MR, Mascitelli L. Surgery and cancer promotion: are we trading beauty for cancer? QJM. 2011;104:811–15. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/hcr039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Comen E, Norton L, Massagué J. Clinical implications of cancer self-seeding. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2011;8:369–77. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2011.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Norton L, Massagué J. Is cancer a disease of self-seeding? Nat Med. 2006;12:875–8. doi: 10.1038/nm0806-875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Parmar V, Hawaldar RW, Pandey N, Siddique S, Nadkarni MS, Badwe RA. Surgical removal of primary tumor in women with metastatic breast cancer—is it really justified? [abstract 323] Am Soc Clin Oncol Breast Cancer Symp. 2009. [Available online at: http://www.asco.org/ASCOv2/Meetings/Abstracts?&vmview=abst_detail_view&confID=70&abstractID=40419; cited May 28, 2012]

- 44.Khan SA. Primary tumor resection in stage iv breast cancer: consistent benefit, or consistent bias? Ann Surg Oncol. 2007;14:3285–7. doi: 10.1245/s10434-007-9547-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]