Abstract

Paraneoplastic acanthosis nigricans (pan) is an infrequently encountered cutaneous manifestation of internal malignancy. Here, we describe a case of pan in the setting of a known breast ductal carcinoma in situ, which, to our knowledge, had not been described in association with pan. As a result, thorough investigation was undertaken to search for another concurrent neoplasm that would better explain the development of pan. In so doing, we identified a coexisting metastatic cholangiocarcinoma. We thus conclude that when pan is observed in an uncommon association with a known malignancy, further investigation should be undertaken to explore whether a more likely occult culprit exists.

Keywords: Acanthosis nigricans, paraneoplastic acanthosis nigricans, cholangiocarcinoma, ductal carcinoma in situ

1. CASE DESCRIPTION

A 51-year-old woman was seen in consultation in the dermatology clinic for progressive pruritic skin changes affecting the axilla, groin, and neck. She had been referred by her oncologist, who was managing her recently diagnosed breast cancer. Definitive treatment had been initiated and consisted of left breast lumpectomy, sentinel node biopsy, and adjuvant radiation therapy. Final pathology had demonstrated a microinvasive ductal carcinoma in situ with a negative sentinel lymph node.

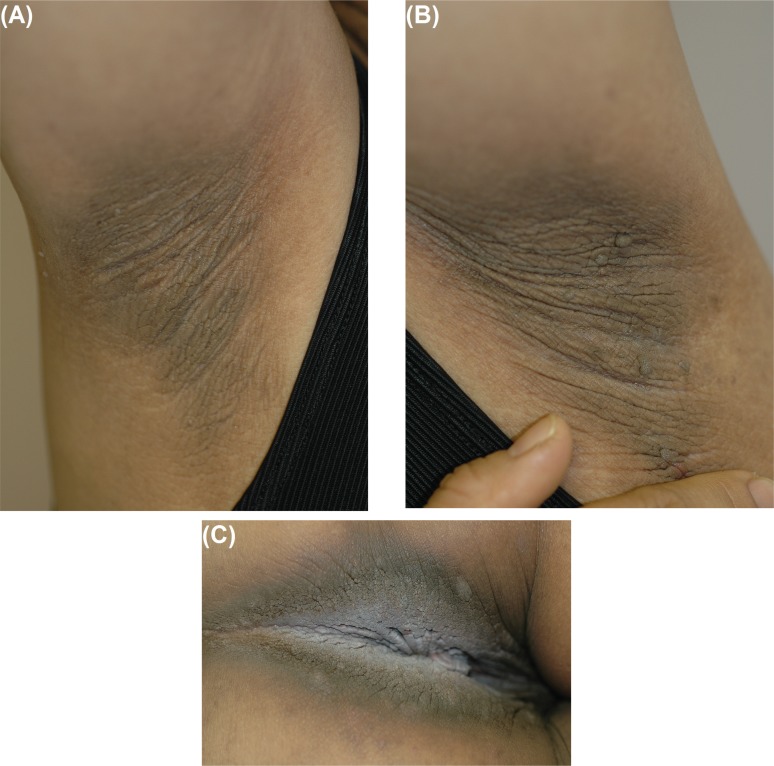

On clinical assessment, the patient was asymptomatic with respect to her breast cancer, and she had recovered completely from surgery. She had no symptoms apart from the pruritus associated with the cutaneous findings. Physical examination revealed velvety dark rugose changes in the axillae bilaterally [Figure 1(A–B)], the perineum (Figure 2), and neck, although no lymphadenopathy was evident. The features of this exanthem were consistent with a diagnosis of acanthosis nigricans.

FIGURE 1.

Acanthosis nigricans: characteristic hyperpigmented rugose changes involving the (A) right and (B) left axilla, and the more prominent changes in (C) the skin of the perineum.

Given the patient’s absence of metabolic risk factors and the rapidity of onset of the cutaneous findings, paraneoplastic acanthosis nigricans (pan) was considered. To our knowledge, pan is most often associated with gastrointestinal tract malignancies and has not been reported in the setting of a ductal carcinoma in situ. Investigations were therefore undertaken to rule out a second occult malignancy that might be a better explanation for the findings.

Chest computed tomography (ct) imaging, esophagogastroduodenoscopy, and colonoscopy were all normal, but carbohydrate antigen 19-9 (a tumour marker for pancreatic adenocarcinoma and colorectal cancer) was elevated at 209 kU/L. Abdominal ct revealed a large dilated cystic structure in the gallbladder fossa in which lobulated soft tissue was noted; large masses in the pancreatic bed and porta hepatis were also observed. Marked retroperitoneal adenopathy consistent with metastatic cancer was also noted in the para-aortic region bilaterally.

A ct-guided biopsy of the retroperitoneal lymph nodes demonstrated carcinoma of an undetermined primary. On staining, tumour cells were positive for epithelial membrane antigen and carcinoembryonic antigen, but negative for cytokeratins 7 and 20, estrogen receptor, thyroid transcription factor 1, and calretinin. This staining pattern pointed toward tumours of biliary, pancreatic, and gastric origin, and was not consistent with metastatic breast cancer.

The local Tumour Board reviewed the patient’s case and concluded that the intra-abdominal findings were most consistent with metastatic cholangiocarcinoma arising from the choledochal cyst. The patient was deemed to have non-curable disease and was offered treatment with palliative chemotherapy.

2. DISCUSSION

Acanthosis nigricans is characterized by hyperpigmented velvety plaques affecting intertriginous areas, including the neck, axilla, and inframammary and inguinal regions1,2. These clinical findings alone are adequate for making a diagnosis of acanthosis nigricans, but biopsy demonstrates the histology findings of mild acanthosis with hyperkeratosis and dermal papillomatosis2. Acanthosis nigricans is observed most often in association with insulin-resistant states3 and endocrine disorders4, in which it represents a benign but cosmetically problematic finding. However, acanthosis nigricans can occasionally portend the presence of an internal malignancy. In this context, it is called malignant acanthosis nigricans or pan.

Unlike typical acanthosis nigricans, pan tends to affect middle-age or older patients and can be rapidly progressive with extensive mucocutaneous involvement. This major feature distinguishes it from benign acanthosis nigricans, in which the symmetrically distributed lesions tend to appear at a younger age and do not evolve with time. In addition to systemic features such as weight loss and cachexia, pan may also be seen along with other cutaneous manifestations of internal malignancy, including florid cutaneous papillomatosis5, tripe palms6, and the sign of Leser–Trélat2,7,8. These features, when present, also aid in differentiating between benign acanthosis nigricans and pan.

Among the neoplastic associations with pan, abdominal carcinomas are the most frequent (the preponderance being gastric adenocarcinomas2,9,10), although a broad spectrum of cancers have been documented, including (but not limited to) neoplasia of the urinary bladder11, esophagus12, adrenals13, lung5, liver14, gall bladder15, ovaries7, and endometrium6,16. In the context of breast carcinoma, pan is rare10. It has, however, been reported in the setting of cholangiocarcinoma17.

The pathophysiology of pan is poorly understood, but several theories have been posited. The role of insulin-like growth factors, either produced directly by cancerous cells or released in response to stimulatory factors secreted by cancer cells, has been surmised. Alternatively, conjecture has implicated transforming growth factor α and its action on epidermal growth factor receptors18–20. The fact that pan regresses after surgical debulking (which correlates with depressed levels of transforming growth factor α) further supports the latter hypothesis18. As suggested by Yeh et al.9, a more all-encompassing explanation is a “three-hit” model, which proposes that a combination of the presence of malignancy, secretion of growth factors, and cellular susceptibility all contribute to the pathogenesis of pan.

Paraneoplastic acanthosis nigricans may precede or follow diagnosis of the causative malignancy, and it usually parallels the underlying cancer in progression10. Patients may complain of pruritus, though acanthosis nigricans is usually asymptomatic1,2. Topical therapies can aid in symptom management, but interventions targeting the underlying malignancy are most definitive. Despite disease-modifying measures such as surgical resection, chemotherapy, and radiation, the prognosis for patients with pan is poor because of the aggressive nature of the underlying malignancy.

3. CONCLUSIONS

We present a unique case of pan in the setting of two primary malignancies. Rather than attributing the pan to the patient’s known diagnosis of ductal carcinoma in situ, this case illustrates the importance of investigating the more common associations of rare phenomena rather than accepting seemingly convenient explanations that are less plausible.

4. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

No funding source was utilized in the preparation of this manuscript.

5. CONFLICT OF INTEREST DISCLOSURES

The authors have no financial conflicts of interest to declare.

6. REFERENCES

- 1.Rogers DL. Acanthosis nigricans. Semin Dermatol. 1991;10:160–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schwartz RA. Acanthosis nigricans. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;31:1–19. doi: 10.1016/S0190-9622(94)70128-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rendon MI, Cruz PD, Jr, Sontheimer RD, Bergstresser PR. Acanthosis nigricans: a cutaneous marker of tissue resistance to insulin. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1989;21:461–9. doi: 10.1016/S0190-9622(89)70208-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Matsuoka LY, Wortsman J, Gavin JR, Goldman J. Spectrum of endocrine abnormalities associated with acanthosis nigricans. Am J Med. 1987;83:719–25. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(87)90903-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gheeraert P, Goens J, Schwartz RA, Lambert WC, Schroeder F, Debusscher L. Florid cutaneous papillomatosis, malignant acanthosis nigricans, and pulmonary squamous cell carcinoma. Int J Dermatol. 1991;30:193–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4362.1991.tb03850.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gorisek B, Krajnc I, Rems D, Kuhelj J. Malignant acanthosis nigricans and tripe palms in a patient with endometrial adenocarcinoma—a case report and review of literature. Gynecol Oncol. 1997;65:539–42. doi: 10.1006/gyno.1997.4674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kebria MM, Belinson J, Kim R, Mekhail TM. Malignant acanthosis nigricans, tripe palms and the sign of Leser– Trélat, a hint to the diagnosis of early stage ovarian cancer: a case report and review of the literature. Gynecol Oncol. 2006;101:353–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2005.12.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pentenero M, Carrozzo M, Pagano M, Gandolfo S. Oral acanthosis nigricans, tripe palms and sign of Leser–Trélat in a patient with gastric adenocarcinoma. Int J Dermatol. 2004;43:530–2. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2004.02159.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yeh JS, Munn SE, Plunkett TA, Harper PG, Hopster DJ, du Vivier AW. Coexistence of acanthosis nigricans and the sign of Leser–Trélat in a patient with gastric adenocarcinoma: a case report and literature review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;42:357–62. doi: 10.1016/S0190-9622(00)90112-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Curth HO. Cancer associated with acanthosis nigricans. Review of literature and report of a case of acanthosis nigricans with cancer of the breast. Arch Surg. 1943;47:517–52. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1943.01220180003001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Möhrenschlager M, Vocks E, Wessner DB, Nährig J, Ring J. Tripe palms and malignant acanthosis nigricans: cutaneous signs of imminent metastasis in bladder cancer? J Urol. 2001;165:1629–30. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(05)66369-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Amjad M, Arfan-ul-Bari, Shah AA. Malignant acanthosis nigricans: an early diagnostic clue. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak. 2010;20:127–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hiranandani M, Kaur I, Singhi SC, Bhoria U. Malignant acanthosis nigricans in adrenal carcinoma. Indian Pediatr. 1995;32:920–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kamińska–Winciorek G, Brzezińska–Wcisło L, Lis–Swiety A, Krauze E. Paraneoplastic type of acanthosis nigricans in patient with hepatocellular carcinoma. Adv Med Sci. 2007;52:254–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ramirez–Amador V, Esquivel–Pedraza L, Caballero–Mendoza E, Berumen–Campos J, Orozco–Topete R, Angeles–Angeles A. Oral manifestations as a hallmark of malignant acanthosis nigricans. J Oral Pathol Med. 1999;28:278–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.1999.tb02039.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mekhail TM, Markman M. Acanthosis nigricans with endometrial carcinoma: case report and review of the literature. Gynecol Oncol. 2002;84:332–4. doi: 10.1006/gyno.2001.6472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Scully C, Barrett WA, Gilkes J, Rees M, Sarner M, Southcott RJ. Oral acanthosis nigricans, the sign of Leser–Trélat and cholangiocarcinoma. Br J Dermatol. 2001;145:506–7. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.2001.04393.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Koyama S, Ikeda K, Sato M, et al. Transforming growth factoralpha (tgf alpha)–producing gastric carcinoma with acanthosis nigricans: an endocrine effect of tgf alpha in the pathogenesis of cutaneous paraneoplastic syndrome and epithelial hyperplasia of the esophagus. J Gastroenterol. 1997;32:71–7. doi: 10.1007/BF01213299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ellis DL, Kafka SP, Chow JC, et al. Melanoma, growth factors, acanthosis nigricans, the sign of Leser–Trélat, and multiple acrochordons. A possible role for alpha-transforming growth factor in cutaneous paraneoplastic syndromes. N Engl J Med. 1987;317:1582–7. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198712173172506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Haase I, Hunzelmann N. Activation of epidermal growth factor receptor/Erk signaling correlates with suppressed differentiation in malignant acanthosis nigricans. J Invest Dermatol. 2002;118:891–3. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.2002.17631.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]