Abstract

The Caenorhabditis elegans left and right AWC olfactory neurons communicate to establish stochastic asymmetric identities, AWCON and AWCOFF, by inhibiting a calcium-mediated signaling pathway in the future AWCON cell. NSY-4/claudin-like protein and NSY-5/innexin gap junction protein are the two parallel signals that antagonize the calcium signaling pathway to induce the AWCON fate. However, it is not known how the calcium signaling pathway is downregulated by nsy-4 and nsy-5 in the AWCON cell. Here we identify a microRNA, mir-71, that represses the TIR-1/Sarm1 adaptor protein in the calcium signaling pathway to promote the AWCON identity. Similar to tir-1 loss-of-function mutants, overexpression of mir-71 generates two AWCON neurons. tir-1 expression is downregulated through its 3′ UTR in AWCON, in which mir-71 is expressed at a higher level than in AWCOFF. In addition, mir-71 is sufficient to inhibit tir-1 expression in AWC through the mir-71 complementary site in the tir-1 3′ UTR. Our genetic studies suggest that mir-71 acts downstream of nsy-4 and nsy-5 to promote the AWCON identity in a cell autonomous manner. Furthermore, the stability of mature mir-71 is dependent on nsy-4 and nsy-5. Together, these results provide insight into the mechanism by which nsy-4 and nsy-5 inhibit calcium signaling to establish stochastic asymmetric AWC differentiation.

Author Summary

Cell identity determination requires a competition between the induction of cell type–specific genes and the suppression of genes that promote an alternative cell type. In the nematode C. elegans, a specific sensory neuron pair communicates to establish stochastic asymmetric identities by inhibiting a calcium signaling pathway in the neuron that becomes an induced identity. However, it is not understood how cell–cell communication inhibits the calcium signaling pathway in the induced neuronal identity. In this study, we identify a microRNA that represses the expression of a key molecule in the calcium signaling pathway to promote the induced neuronal identity. Overexpression of the microRNA causes both neurons of the pair to become the induced identity, similar to the mutants that lose function in the calcium signaling pathway. In addition, the stability of the mature microRNA is dependent on a claudin-like protein and a gap junction protein, the two parallel signals that mediate communication of the neuron pair to promote the induced neuronal identity. Our results provide insight into the mechanism by which cell–cell communication inhibits calcium signaling to establish stochastic asymmetric neuronal differentiation.

Introduction

Cell fate determination during development requires both the induction of cell type specific genes and the suppression of genes that promote an alternative cell fate [1]–[4]. For example, both inductive signaling, mediated by an EGFR-Ras-MAPK pathway, and lateral inhibition, mediated by LIN-12/Notch activity and microRNA (miRNA), are required for six multipotential vulval precursor cells to adopt an invariant pattern of fates in C. elegans [5]. Notch signaling-mediated lateral inhibition also plays a crucial role in the neuronal/glial lineage decisions of neural stem cells; as well as the B/T, alphabeta/gammadelta, and CD4/CD8 lineage choices during lymphocyte development [6], [7]. In the Drosophila eye, the kinase Warts and PH-domain containing Melted repress each other's transcription in a bistable feedback loop to regulate the two alternative R8 photoreceptor subtypes expressing Rhodopsin Rh5 or Rh6 [2]. In the C. elegans sensory system, two sets of transcription factors and miRNAs reciprocally repress each other to achieve and stabilize one of the two mutually exclusive ASEL and ASER taste neuronal fates [8]–[10]. Notch signaling acts upstream of the miRNA-controlled bistable feedback loop to regulate ASE asymmetry through a lineage-based mechanism in early embryos [11].

The C. elegans left and right sides of Amphid Wing Cell C (AWC) olfactory neurons specify asymmetric subtypes through a novel mechanism independent of the Notch pathway in late embryogenesis [12]. Like ASE neurons, the two AWC neurons are morphologically symmetrical but take on asymmetric fates, such that the AWCON neuron expresses the chemoreceptor gene str-2 and the contralateral AWCOFF neuron does not [12]–[14]. Asymmetric differentiation of AWC neurons allows the worm to discriminate between different odors [15]. In contrast to reproducible ASE asymmetry, AWC asymmetry is stochastic: 50% of animals express str-2 on the left and the other 50% express it on the right. Ablation of either AWC neuron causes the remaining AWC neuron to become AWCOFF, suggesting that AWCOFF is the default state and the induction of AWCON requires an interaction or competition between the AWC neurons [12]. The axons of the two AWC neurons form chemical synapses with each other; AWC asymmetry is established near the time of AWC synapse formation [16], [17]. In addition, axon guidance mutants are defective in inducing the AWCON state. These results suggest that the synapses could mediate the AWC interaction for asymmetry [12].

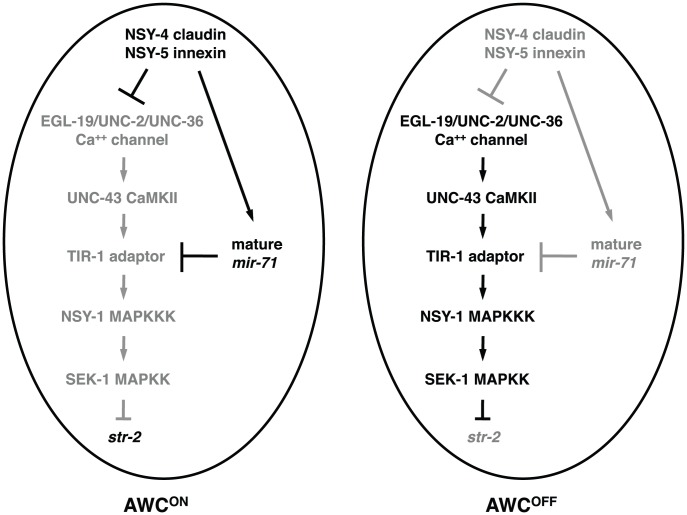

nsy-4, encoding a claudin-like tight junction protein, and nsy-5, encoding an innexin gap junction protein, act in parallel to downregulate the calcium-mediated UNC-43 (CaMKII)/TIR-1 (Sarm1)/NSY-1 (MAPKKK) signaling pathway in the future AWCON cell [18], [19]. Both AWCs and non-AWC neurons in the NSY-5 gap junction dependent cell network communicate to participate in signaling that coordinates left-right AWC asymmetry. In addition, non-AWC neurons in the NSY-5 gap junction network are required for the feedback signal that ensures precise AWC asymmetry [18]. Once AWC asymmetry is established in late embryogenesis, both the AWCON and AWCOFF identities are maintained by cGMP signaling, dauer pheromone signaling, and transcriptional repressors [12], [20], [21]. unc-43(CaMKII), tir-1 (Sarm1), and nsy-1 (MAPKKK) are also implicated in the maintenance of AWC asymmetry in the first larval (L1) stage [22]. Although multiple genes were identified to be involved in the establishment and the maintenance of AWC asymmetry (for a review, see [23]), it is still unknown how the calcium-regulated signaling pathway is inhibited by nsy-4 and nsy-5 in the AWCON cell.

The TIR-1/Sarm1 adaptor protein assembles a calcium-signaling complex, UNC-43 (CaMKII)/TIR-1/NSY-1 (ASK1 MAPKKK), at AWC synapses to regulate the default AWCOFF identity [16], thus downregulation of tir-1 expression may represent an efficient mechanism to inhibit calcium signaling in the cell becoming AWCON. In support of this idea, a prior large scale examination of potential miRNA targets indicated that tir-1 and unc-43 may be downregulated by this class of RNAs [24]. Here, we analyze the function of the miRNA mir-71 in stochastic AWC asymmetry by characterizing its role in downregulation of the calcium signaling pathway in the AWCON cell. We show that mir-71 acts downstream of nsy-4/claudin and nsy-5/innexin to promote AWCON in a cell autonomous manner through inhibiting tir-1 expression, in parallel with other processes. We also show that nsy-4 and nsy-5 are required for the stability of mature mir-71. Our results suggest a mechanism for genetic control of AWC asymmetry by nsy-4 and nsy-5 through mir-71-mediated downregulation of calcium signaling.

Results

Identification of miRNAs with predicted target genes in the AWC calcium signaling pathway

The calcium-regulated UNC-43 (CaMKII)/TIR-1 (Sarm1)/NSY-1 (ASK1 MAPKKK) signaling pathway suppresses expression of the AWCON gene str-2 in the default AWCOFF cell [12], [16], [25], [26]. To establish AWC asymmetry, the calcium-mediated signaling pathway is suppressed in the future AWCON cell. miRNAs are small non-coding RNAs that are robust in mediating post-transcriptional and/or translational downregulation of target genes [27]. In C. elegans, miRNAs are processed from premature form into mature form by alg-1/alg-2 (encoding the Argonaute proteins) and dcr-1 (encoding the ribonuclease III enzyme Dicer) [28]. Gene expression profiling revealed increased levels of unc-43 and tir-1 in dcr-1 mutants [24], suggesting that unc-43 and tir-1 may be downregulated by miRNAs. Thus, we hypothesized that miRNAs may play a role in downregulation of the UNC-43/TIR-1/NSY-1 signaling pathway in the cell becoming AWCON.

To test this hypothesis, we took a computational approach to identify miRNAs predicted to target the 3′ UTRs of known genes, including unc-2, unc-36, egl-19, unc-43, tir-1, nsy-1, and sek-1, in the AWC calcium signaling pathway. Only the miRNAs that fit the following criteria were selected for further analysis: 1) At least 6 nucleotides in the seed region (position 1–7 or 2–8 at the 5′ end) of a miRNA is perfectly matched to the target 3′ UTR; 2) The seed match between a miRNA and its target 3′ UTR is conserved between C. elegans and a closely related nematode species C. briggsae, since evolutionary conservation between C. elegans and C. briggsae genomes is useful in identifying functionally relevant DNA sequences such as regulatory regions [29], [30]; and 3) A miRNA is predicted by both MicroCosm Targets (formerly miRBase Targets; http://www.ebi.ac.uk/enright-srv/microcosm/htdocs/targets/v5/) [31]–[33] and TargetScan (http://www.targetscan.org/worm_12/) [34]. Based on these criteria, we identified six potential miRNAs (mir-71, mir-72, mir-74, mir-228, mir-248, mir-255) predicted to target unc-2, unc-43, tir-1, nsy-1, and sek-1 (Figure S1A). A subset of these identified miRNA-target pairs were also predicted by other miRNA target prediction programs, including PicTar (http://pictar.mdc-berlin.de/) [35] and mirWIP (http://146.189.76.171/query.php) [36].

Since most miRNAs are not individually essential and have functional redundancy [37]–[40], loss-of-function mutations in a single miRNA may not show a defect in AWC asymmetry. To circumvent potential problems that may be posed by functional redundancy, we took an overexpression approach to determine the role of these six miRNAs in AWC asymmetry. We generated transgenic strains overexpressing individual miRNAs in both AWCs using an odr-3 promoter, expressed strongly in AWC neuron pair and weakly in AWB neuron pair [41]. Wild-type animals have str-2p::GFP (AWCON marker) expression in only one of the two AWC neurons (Figure 1A and 1E). Since loss-of-function mutations in the AWC calcium signaling genes (unc-2, unc-36, unc-43, tir-1, nsy-1, and sek-1) led to str-2p::GFP expression in both AWC neurons (2AWCON phenotype) (Figure 1B and 1E) [12], [16], [25], [26], we proposed that overexpression of the miRNA downregulating one of these calcium signaling genes would also cause a 2AWCON phenotype. We found that mir-71(OE) animals overexpressing mir-71, predicted to target tir-1 and nsy-1, had a strong 2AWCON phenotype (Figure 1C, 1E, and Figure S1B). This result suggests that mir-71 may downregulate the expression of tir-1 and nsy-1 to control the AWCON fate and that mir-71 is sufficient to promote AWCON when overexpressed. However, overexpression of the other five miRNAs individually caused a mixed weak phenotype of 2AWCON and 2AWCOFF (Figure S1B). Since the activity of the nsy-1 3′ UTR in AWC was independent of mir-71(OE) (Figure S2B), we focused on the investigation of the potential role of mir-71 in promoting AWCON through negatively regulating tir-1 expression.

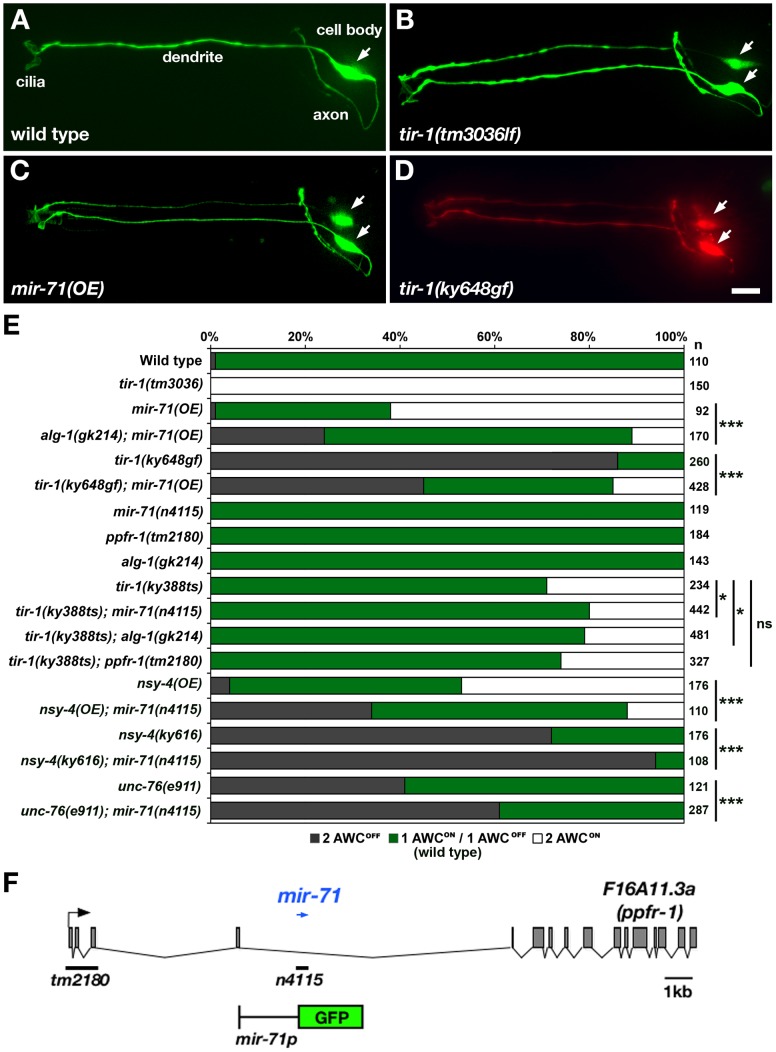

Figure 1. mir-71 promotes the AWCON identity.

(A–D) Expression of a stable transgene str-2p::GFP (AWCON marker) in wild type (A), tir-1(tm3036) loss-of-function (lf) mutants (B), mir-71(OE) animals overexpressing the transgene odr-3p::mir-71 in AWCs (C), and tir-1(ky648gf) mutants (D). tir-1(ky648gf) mutants also carry the transgene odr-1p::DsRed (expressed in both AWCON and AWCOFF) to show that the absence of str-2p::GFP expression is not due to loss of AWC neurons. (E) str-2p::GFP expression phenotypes in wild type, single mutants, and double mutants. nsy-4(OE) animals overexpress the transgene odr-3p::nsy-4 in AWCs. (F) Genetic map of mir-71. mir-71 (blue arrow) is located in an intron of F16A11.3a encoding the ppfr-1 gene. Black bars indicate the location of deletions in ppfr-1(tm2180) and mir-71(n4115) mutants. A schematic of the GFP reporter gene driven by a 2.4 kb region upstream of mir-71 transcript is shown. Arrows, AWC cell body. Scale bar, 10 µm. Statistical analysis was performed using the Z-test for two proportions: *p<0.05; ***p<0.001; ns, not significant.

mir-71 antagonizes the calcium signaling pathway to promote the AWCON identity

The genetic interaction between mir-71 and tir-1 was characterized by double mutants (Figure 1E). tir-1(ky648) gain-of-function (gf) mutants had two AWCOFF neurons (2AWCOFF phenotype) (Figure 1D and 1E) [22]. We found the tir-1(ky648gf) 2AWCOFF phenotype was significantly reduced in the tir-1(ky648gf); mir-71(OE) double mutants (p<0.001) (Figure 1E). These results support the hypothesis that mir-71 downregulates tir-1 to control the AWCON fate.

To further determine the requirement of mir-71 in AWC asymmetry, we analyzed str-2p::GFP expression in the mir-71(n4115) deletion null allele [40]. mir-71(n4115) mutants displayed wild-type AWC asymmetry (Figure 1E), suggesting that mir-71 may function redundantly with other miRNAs or non-miRNA genes to regulate calcium signaling in AWC asymmetry. In addition to mir-71, mir-248 was also predicted to target tir-1 by three programs (Figure S1A). mir-71 and mir-248 have different predicted target sites in the tir-1 3′ UTR. Since mir-248 mutants are not available, we analyzed the effect of mir-248 overexpression on AWC asymmetry. Unlike the highly penetrant 2AWCON phenotype caused by mir-71 overexpression, mir-248 overexpression generated a mixed weak phenotype of 2AWCON and 2AWCOFF (Figure S1B). To test whether mir-71 and mir-248 have a synergistic effect on AWC symmetry, we made transgenic animals overexpressing both mir-71 and mir-248 in AWCs. The 2AWCON phenotype was not significantly higher in mir-71(OE); mir-248(OE) animals than in mir-71(OE) (data not shown). These results suggest that mir-71 may not act redundantly with mir-248 to regulate tir-1 expression in AWC asymmetry. To knockdown mir-248 expression, we made an anti-mir248 transgene expressing short hairpin RNA (shRNA), consisting of both sense and antisense sequences of mir-248, in AWC. The anti-mir-248 transgene caused an AWC phenotype similar to mir-248(OE) (data not shown), suggesting that the effect of the anti-mir-248 transgene on AWC asymmetry is not through knockdown of mir-248 but mainly due to overexpression of sense mir-248 in the shRNA construct.

Functional redundancy of miRNAs and other regulatory pathways has been suggested by a previous study in the Drosophila eye [42]. To overcome functional redundancy of mir-71, we crossed mir-71(n4115) into sensitized backgrounds including tir-1(ky388), nsy-4(ky616), and unc-76(e911) mutants. tir-1(ky388) is a temperature-sensitive (ts) allele that caused a 2AWCON phenotype in 29% of animals at 15°C (Figure 1E) [16]. The 2AWCON phenotype of tir-1(ky388ts) mutants was significantly suppressed by mir-71(n4115), such that 20% of mir-71(n4115); tir-1(ky388ts) double mutants had a 2AWCON phenotype (p<0.05; Figure 1E). These results further support the hypothesis that mir-71 antagonizes the function of tir-1 in the calcium signaling pathway to promote the AWCON fate.

mir-71 is located within a large intron of the F16A11.3a (ppfr-1) gene, encoding a protein phosphatase 2A regulatory subunit (Figure 1F). It is possible that the 181 bp deletion mutation within the intron of ppfr-1 in mir-71(n4115) mutants may affect ppfr-1 activity leading to suppression of the tir-1(ky388ts) 2AWCON phenotype. To test this possibility, we analyzed AWC phenotypes in ppfr-1(tm2180); tir-1(ky388ts) double mutants. ppfr-1(tm2180) has a 1027 bp deletion removing the first three exons and therefore is a potential null allele (Figure 1F) [43]. The 2AWCON phenotype of ppfr-1(tm2180); tir-1(ky388ts) double mutants was not significantly different from that of tir-1(ky388ts) single mutants (Figure 1E). This result suggest that ppfr-1 is not required for AWC asymmetry and that suppression of the tir-1(ky388ts) 2AWCON phenotype was most likely caused by loss of mir-71 activity in mir-71(n4115) mutants.

The nsy-4 claudin-like gene and the unc-76 axon guidance pathway gene induce the AWCON state by inhibiting the downstream calcium-signaling pathway. Loss-of-function mutations in nsy-4 and unc-76 cause a partially penetrant 2AWCOFF phenotype (Figure 1E) [12], [19]. mir-71(n4115) mutations significantly enhanced the 2AWCOFF phenotype of nsy-4(ky616) and unc-76(e911) mutants (p<0.001). On the other hand, the 2 AWCON phenotype of nsy-4(OE) trasnsgenic animals overexpressing nsy-4 in AWCs was significantly suppressed in nsy-4(OE); mir-71(n4115) double mutants (p<0.001; Figure 1E). These results are consistent with a role of mir-71 function in promoting the AWCON fate, and suggest that mir-71 may act in parallel with other regulatory molecules to antagonize the calcium-regulated signaling pathway to generate the AWCON identity.

mir-71 inhibits tir-1 expression through its 3′ UTR

The predicted mir-71 target site in the tir-1 3′ UTR is 96 bp downstream of the stop codon; the prediction is strongly supported by four different programs, including MicroCosm Targets, TargetScan, PicTar, and mirWIP (Figure S1A). The nucleotides at position 1–8 in the seed region of mir-71 perfectly match the target site of the tir-1 3′ UTR; the seed match is conserved between C. elegans and C. briggsae (Figure 2A).

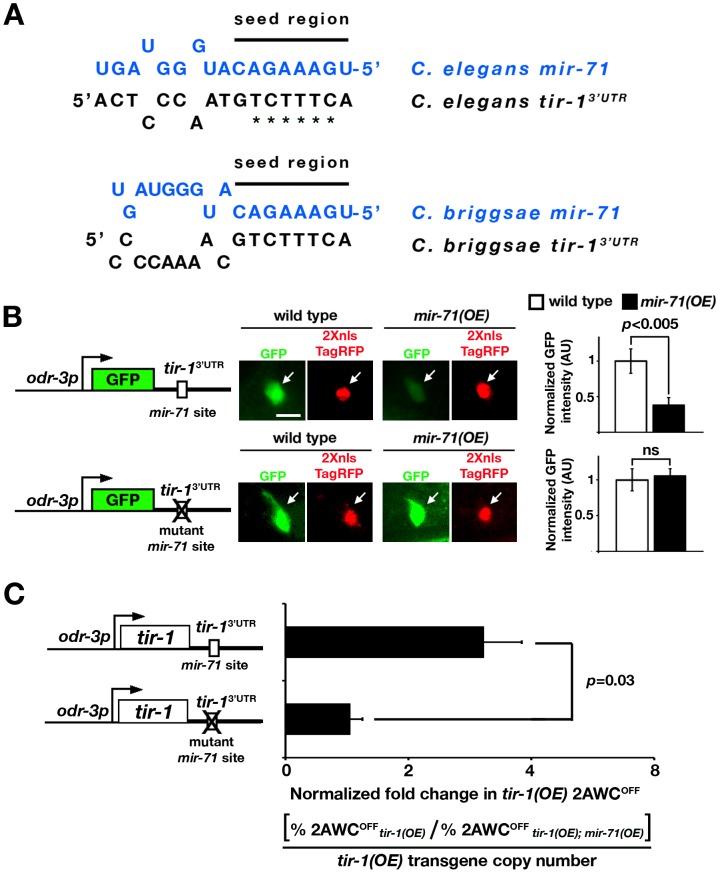

Figure 2. mir-71 downregulates gene expression through the tir-1 3′ UTR.

(A) Complementarity between the mir-71 seed region and the tir-1 3′ UTR in C. elegans and C. briggsae. Asterisks denote nucleotides mutated in the predicted mir-71 target site of the tir-1 3′ UTR in (B). (B) Left: GFP sensor constructs, driven by the odr-3 promoter, with the tir-1 3′ UTR or the tir-1 3′ UTR mutated in the predicted mir-71 target site. Middle: Images of GFP expression from GFP sensor constructs and nucleus-localized TagRFP expression from the internal control transgene odr-3p::2Xnls-TagRFP::unc-54 3′ UTR in the AWC cell body of wild type and mir-71(OE) animals. All images were taken from animals in the first larval stage. Scale bar, 5 µm. Arrows, AWC cell body. Right: The average normalized GFP intensity of each sensor construct in the AWC cell body. The GFP intensity of an individual cell was normalized to the TagRFP intensity of the same cell. For each sensor construct line, the normalized GFP intensity in wild type was set as 1 arbitrary unit (AU) and the normalized GFP intensity in mir-71(OE) was calibrated to that in wild type. Student's t-test was used for statistical analysis. n = 16–21 for each transgenic line in wild type and mir-71(OE) animals. Error bars, standard error of the mean. ns, not significant. (C) Left: tir-1 overexpression constructs, driven by the odr-3 promoter, with the tir-1 3′ UTR or the tir-1 3′ UTR mutated in the predicted mir-71 target site. Right: Normalized fold change in tir-1(OE) 2AWCOFF phenotype. The fold change in tir-1(OE) 2AWCOFF phenotype was determined by dividing the 2AWCOFF percentage of tir-1(OE) with the 2AWCOFF percentage of tir-1(OE); mir-71(OE), which was then normalized to the relative tir-1(OE) transgene copy number. Two to three independent lines were analyzed for each tir-1 overexpression construct. Student's t-test was used to calculate statistical significance. Error bars represent standard error of the mean.

To determine whether mir-71 acts directly through the predicted binding site in the tir-1 3′ UTR, we made GFP sensor constructs with the AWC odr-3 promoter and different 3′ UTRs: wild-type tir-1 3′ UTR or the tir-1 3′ UTRmut with mutated mir-71 target site (Figure 2B). Transgenic animals expressing each sensor construct were crossed to mir-71(OE) animals. The GFP intensity of each sensor construct in an individual AWC neuron was normalized to the nucleus-localized TagRFP intensity of the transgene odr-3p::2Xnls-TagRFP::unc-54 3′ UTR in the same cell. The unc-54 3′ UTR does not contain any strongly predicted mir-71 sites. The normalized GFP intensity of each sensor construct was compared between mir-71(OE) animals and their siblings losing the mir-71(OE) transgene in the L1 stage, during which tir-1 is functional for the maintenance of AWC asymmetry [22]. We found that mir-71(OE) animals, compared with wild type, had a significantly reduced normalized expression level of GFP from the tir-1 3′ UTR sensor construct (p<0.005; Figure 2B upper panels). However, the normalized expression level of GFP from the tir-1 3′ UTRmut was not significantly different between wild-type and mir-71(OE) animals (Figure 2B bottom panels). These results suggest that mir-71 directly inhibits gene expression through the predicted target site in the tir-1 3′ UTR. However, we did not observe a significant difference in the GFP expression level from the tir-1 3′ UTR between wild-type animals and mir-71(n4115lf) mutants (Figure S2A). This result suggests potential functional redundancy of mir-71 in the regulation of tir-1 expression.

Interactions between the 5′ and 3′ UTRs have been shown to regulate translation in mammalian cells [44], bacteria [45], and RNA viruses [46]. To determine if the tir-1 5′ UTR plays a role in regulating the inhibitory effect of mir-71 on the tir-1 3′ UTR, we included the tir-1 5′ UTR in the GFP sensor constructs (Figure S3). Similar to the tir-1 3′ UTR sensor constructs without the tir-1 5′ UTR (Figure 2B), the normalized expression level of GFP from the tir-1 5′ UTR/tir-1 3′ UTR sensor construct was significantly decreased in mir-71(OE) animals compared with wild type (p<0.04; Figure S3A). However, the normalized expression level of GFP from the tir-1 5′ UTR/tir-1 3′ UTRmut sensor construct was not significantly different between wild-type and mir-71(OE) animals (Figure S3B). These results suggest that the tir-1 5′ UTR does not affect mir-71(OE)-mediated suppression of gene expression through the tir-1 3′ UTR.

The nsy-1 3′ UTR was also predicted to contain a mir-71 binding site by the four programs used in this study (Figure S1A), but the GFP expression level from the nsy-1 3′ UTR was not significantly different between wild-type and mir-71(OE) animals (Figure S2B). This result suggests that the predicted mir-71 site in the nsy-1 3′ UTR may not be functional in AWC cells, therefore we did not further investigate the regulation of nsy-1 expression by mir-71.

tir-1(OE) animals overexpressing tir-1 in AWC had a 2AWCOFF phenotype [16]. We used the tir-1(OE) 2AWCOFF phenotype as readout to determine if mir-71 acts through the tir-1 3′ UTR to suppress the AWCOFF fate. We made tir-1(OE) sensor constructs by replacing GFP in the GFP sensor constructs (Figure 2B) with tir-1 and crossed transgenic animals expressing each tir-1(OE) sensor construct into mir-71(OE) animals (Figure 2C). The fold change in tir-1(OE) 2AWCOFF phenotype was determined by dividing the 2AWCOFF percentage of tir-1(OE) animals with the 2AWCOFF percentage of their tir-1(OE); mir-71(OE) siblings, which was then normalized to the relative tir-1(OE) transgene copy number determined by qPCR. The higher normalized fold change in tir-1(OE) 2AWCOFF indicates more suppression of 2AWCOFF phenotype by mir-71(OE) in tir-1(OE); mir-71(OE) animals. The normalized fold change in tir-1(OE) 2AWCOFF of tir-1 3′ UTR was significantly higher than that of the tir-1 3′ UTRmut (p = 0.03; Figure 2C). These results suggest that mir-71 suppresses the AWCOFF fate by downregulating tir-1 expression through its 3′ UTR.

mir-71 is expressed at a higher level in the AWCON cell than in the AWCOFF cell

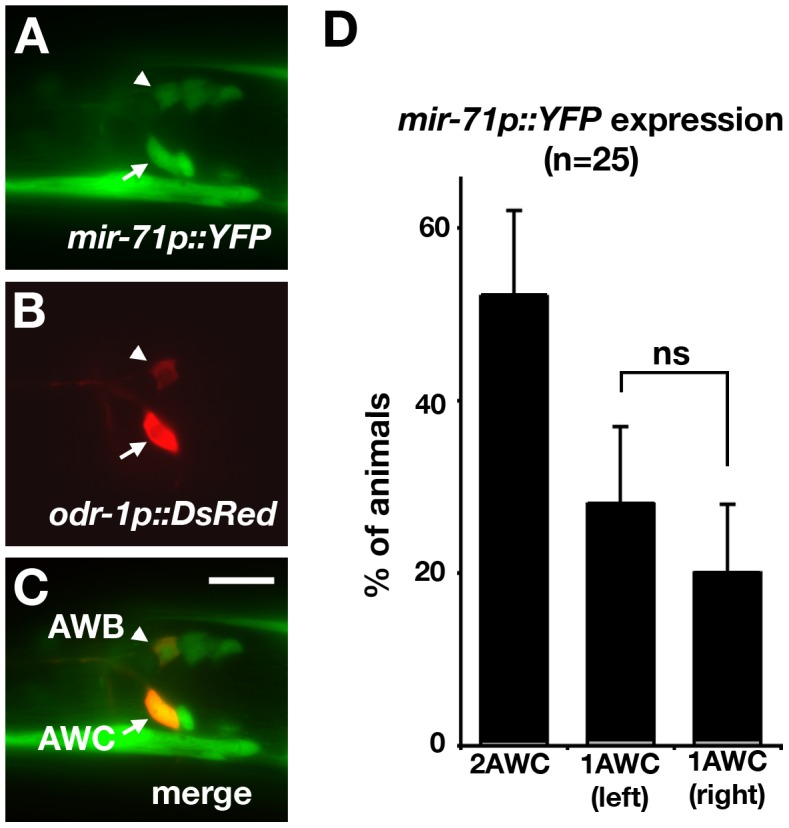

To determine if mir-71 is expressed in AWC neurons, we generated transgenic animals expressing YFP under the control of a 2.4 kb promoter upstream of the mir-71 transcript (Figure 1F). The expression of YFP was detected in several head neurons and the body wall muscle in L1 (Figure 3A), which is consistent with previously reported expression pattern of mir-71 [47]–[49]. The mir-71p::YFP transgenic animals were crossed into an odr-1p::DsRed strain, expressing DsRed primarily in AWC and AWB neurons (Figure 3B). YFP was coexpressed with DsRed in AWC and AWB neurons (Figure 3C), suggesting that mir-71 is expressed in these neurons. We found that 52% of animals had visible mir-71p::YFP in both AWC cells, 28% had visible YFP in only AWC left (AWCL), and 20% had visible YFP in only AWC right (AWCR) (Figure 3D). These results suggest that the expression of mir-71, when detected in one of the two AWC neurons, does not have a side bias towards AWCL or AWCR, which is consistent with stochastic choice of the AWCON fate.

Figure 3. mir-71 is expressed in AWC.

(A, B) Images of a first stage larva expressing the transgenes mir-71p::YFP (A) and odr-1p::DsRed, a marker for AWB and AWC neurons (B). (C) Merged image showing co-expression of YFP and DsRed in AWC and AWB neurons. (D) Quantification of the number of AWC neurons with visible expression of the mir-71p::YFP reporter gene at the first larval stage. Z-test was used to calculate statistical significance. Error bar represents the standard error of proportion. ns, not significant. Arrowhead, AWB cell body; arrow, AWC cell body. Scale bar, 10 µm.

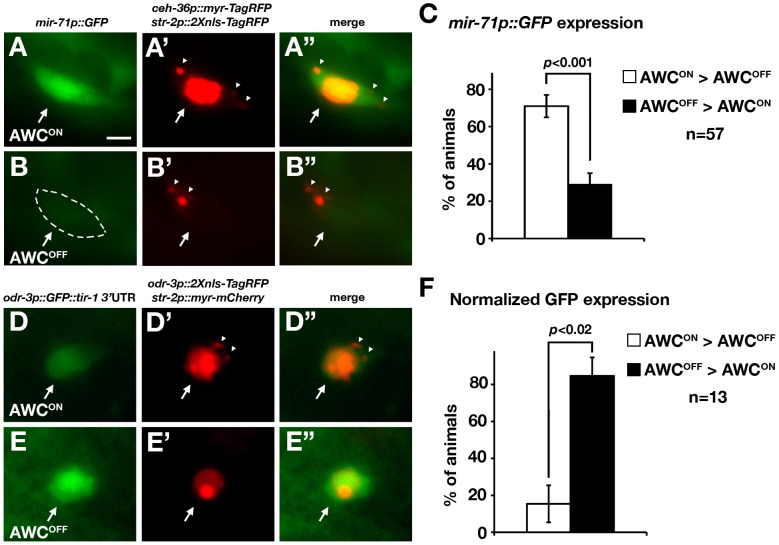

We then investigated whether mir-71, when detected in both AWC neurons, has differential expression levels between AWCON and AWCOFF. Transgenic animals expressing mir-71p::GFP, ceh-36p::myr-TagRFP (myristoylated TagRFP marker of AWCON and AWCOFF), and str-2p::2Xnls-TagRFP (nucleus-localized TagRFP marker of AWCON) were generated and analyzed in the L1 stage (Figure 4A, 4A′, 4A″, 4B, 4B′, and 4B″). The ceh-36 promoter is expressed in AWCL, AWCR, ASEL, and ASER [50], [51]. mir-71p::GFP expression was significantly higher in the AWCON cell than in the AWCOFF cell in 71% of the animals (p<0.001; Figure 4C). To confirm this result, we generated transgenic animals expressing mir-71p::NZGFP, odr-3p::CZGFP, and str-2p::2Xnls-TagRFP in which reconstituted GFP (recGFP) [52] expression from two split GFP polypeptides, NZGFP and CZGFP, was restricted mainly in the two AWC cells. Consistent with the mir-71p::GFP result, recGFP expression was significantly higher in the AWCON cell than in the AWCOFF cell in 81% of the animals (p<0.001; Figure S4). Together, these results suggest that mir-71 is expressed at a higher level in the AWCON than in the AWCOFF cell. The higher expression of mir-71 in the AWCON cell is consistent with the role of mir-71 in promoting the AWCON fate.

Figure 4. mir-71 expression and the tir-1 3′ UTR are differentially regulated in AWCON and AWCOFF neurons.

(A, B) Images of mir-71p::GFP. The AWCOFF cell body is outlined by dashed lines, which was done when the GFP intensity was temporarily enhanced with the Photoshop levels tool. (A′, B′) Images of ceh-36p::myr-TagRFP and str-2p::2Xnls-TagRFP. AWCON was identified as str-2p::2Xnls-TagRFP positive and ceh-36p::myr-TagRFP positive (A′). AWCOFF was identified as str-2p::2Xnls-TagRFP negative and ceh-36p::myr-TagRFP positive (B′). (A″) Merge of A and A′ images from the same cell. (B″) Merge of B and B′ images from the same cell. (C) Quantification of mir-71p::GFP expression in AWCON and AWCOFF cells. (D, E) Images of odr-3p::GFP::tir-1 3′ UTR. (D′, E′) Images of odr-3p::2Xnls-TagRFP::unc-54 3′ UTR and str-2p::myr-mCherry. The AWCON cell was identified as str-2p::myr-mCherry positive and odr-3p::2XTagRFP positive (D′). The AWCOFF cell was defined as str-2p::myr-mCherry negative and odr-3p::2Xnls-TagRFP positive (E′). (D″) Merge of D and D′ images from the same cell. (E″) Merge of E and E′ images from the same cell. (F) Quantification of normalized GFP expression in AWCON and AWCOFF cells. Normalized GFP expression was determined by calibrating GFP intensity with 2Xnls-TagRFP intensity of the same cell. All constructs, except for odr-3p::GFP::tir-1 3′ UTR, contain the unc-54 3′ UTR. All images were taken from first stage larvae. The single focal plane with the brightest fluorescence in each AWC was selected from the acquired image stack and measured for fluorescence intensity. Each animal was categorized into one of three categories: AWCON = AWCOFF, AWCON>AWCOFF, and AWCOFF>AWCON based on the comparison of GFP intensities between AWCON and AWCOFF cells of the same animal. We did not observe any animals that fell into the “AWCON = AWCOFF” category from our GFP intensity analysis. Total number of animals for each category was tabulated and analyzed as described [86]. p-values were calculated using X 2 test. Error bars represent standard error of proportion. Arrows indicate the AWC cell bodies. Arrowheads represent myr-TagRFP or myr-mCherry signal. Scale bar, 2 µm.

tir-1 expression is downregulated through its 3′ UTR in the AWCON cell

The suppression of gene expression by mir-71 through the tir-1 3′ UTR (Figure 2B and 2C) and the role of mir-71 in promoting the AWCON fate (Figure 1C and 1E) suggest that gene expression through the tir-1 3′ UTR may be downregulated in the AWCON cell. To investigate this possibility, transgenic animals expressing odr-3p::GFP::tir-1 3′ UTR (GFP reporter of the tir-1 3′ UTR regulation in both AWCs), odr-3p::2Xnls-TagRFP::unc-54 3′ UTR (nucleus-localized TagRFP marker of both AWCON and AWCOFF), and str-2p::myr-mCherry (myristoylated mCherry marker of AWCON) were generated and analyzed in the L1 stage (Figure 4D, 4D′, 4D″, 4E, 4E′, and 4E″). The GFP intensity was normalized to the nucleus-localized TagRFP intensity measured in the same AWC cell to account for variation in focal plane and promoter activity. Normalized GFP intensity was significantly lower in the AWCON cell than in the AWCOFF cell in more than 85% of the animals (p<0.02; Figure 4F). These results suggest that the expression of tir-1 is downregulated in the AWCON cell, consistent with a higher expression level of mir-71 in AWCON and downregulation of tir-1 expression by mir-71.

mir-71 acts cell-autonomously to promote the AWCON identity

To determine the site of mir-71 action, mosaic animals in which the two AWC neurons have differential mir-71 activity were used to ask whether mir-71 acts in the future AWCON cell or the future AWCOFF cell. Mosaic animals were generated by random and spontaneous mitotic loss of an unstable transgene expressing the mir-71(OE) construct odr-3p::mir-71 and a mosaic marker odr-1p::DsRed that showed which AWC cells retained the transgene. We specifically looked for the mosaic animals in which only one of the two AWC neurons expressed the mir-71(OE) transgene; this cell was identified by expression of the DsRed marker.

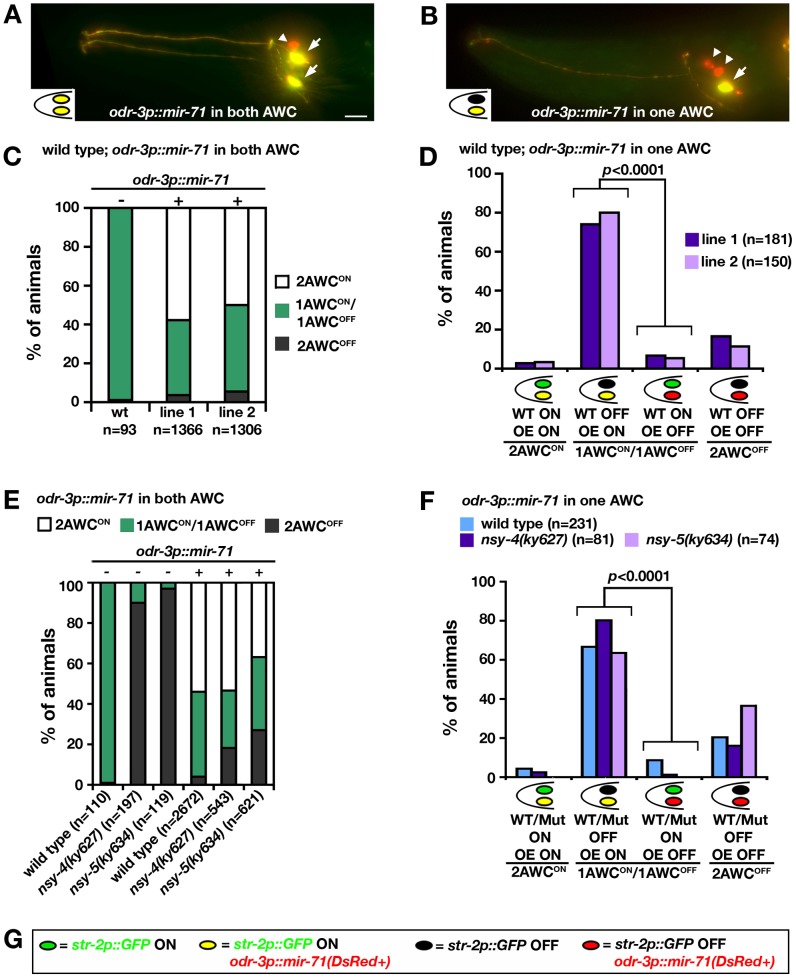

Mosaic analysis was first performed in transgenic lines expressing the mir-71(OE) transgene in a wild-type background. Expression of the mir-71(OE) transgene in both AWC neurons resulted in a 2AWCON phenotype (Figure 5A and 5C). When the mir-71(OE) transgene was retained in only one of the two AWC neurons, the mir-71(OE) AWC neuron became AWCON and wild-type AWC neuron became AWCOFF in the majority of these mosaic animals (p<0.0001; Figure 5B and 5D). This result is consistent with a significant cell-autonomous requirement for mir-71 in the AWCON cell to regulate its identity, which is opposite to the cell autonomous function of tir-1 in regulation of the AWCOFF identity. This result suggests that the AWC cell with higher mir-71 activity can prevent the contralateral AWC cell from becoming AWCON and that mir-71 may play a role in a negative-feedback signal sent from pre-AWCON to pre-AWCOFF. Similar results were obtained from previous mosaic analysis of nsy-4 and nsy-5 [18], [19].

Figure 5. mir-71 acts cell-autonomously to promote AWCON.

(A, B) Projections of wild-type animals expressing an integrated str-2p::GFP transgene (green) and an unstable transgenic array containing odr-3p::mir-71 and odr-1p::DsRed (red). AWC neurons with co-expression of GFP and DsRed appear yellow. Arrows, AWC cell body; arrowheads, AWB cell body; scale bar, 10 µm. (C, E) AWC phenotypes of wild type (C), nsy-4(ky627), and nsy-5(ky634) mutants (E) expressing the transgene odr-3p::mir-71; odr-1p::DsRed in both AWC neurons. + and − indicate the presence and absence of the transgene odr-3p::mir-71, respectively. (D, F) AWC phenotypes of wild-type (D) and mutant (F) mosaic animals expressing the transgene odr-3p::mir-71; odr-1p::DsRed in one AWC neuron. Two independent transgenic lines were analyzed in wild type, nsy-4(ky627), and nsy-5(ky634) mutants in (C–F). Results from two independent lines were similar and thus were combined in (E, F). Z-test was used to calculate p values. (G) Color codes for AWC neurons in (A), (B), (D), and (F).

NSY-4 claudin-like protein and NSY-5 gap junction protein are the two parallel signaling systems that antagonize the calcium signaling pathway to specify the AWCON identity [18], [19]. To determine whether mir-71 acts downstream of nsy-4 and nsy-5 to promote AWCON, mosaic analysis was performed with the mir-71(OE) transgene in nsy-4(ky627) and nsy-5(ky634) mutants. Loss-of-function mutations in nsy-4 and nsy-5 caused a 2AWCOFF phenotype (Figure 5E) [18], [19], opposite to the mir-71(OE) 2AWCON phenotype. Overexpression of mir-71 in both AWC neurons significantly suppressed the 2AWCOFF phenotype of nsy-4(ky627) and nsy-5(ky634) mutants. In addition, nsy-4(ky627); mir-71(OE) and nsy-5(ky634); mir-71(OE) animals resembled the mir-71(OE) parent more closely than the nsy-4(ky627) or nsy-5(ky634) parent, but mixed phenotypes were observed (Figure 5E). These results suggest that mir-71 mainly acts at a step downstream of nsy-4 and nsy-5 to promote AWCON. In the majority of the mosaic animals retaining the mir-71(OE) transgene in only one of the two AWC neurons, the mir-71(OE) AWC neuron expressed str-2p::GFP and the other AWC neuron did not (Figure 5F). This significant cell-autonomous requirement for mir-71 in the future AWCON neuron in nsy-4(ky627) and nsy-5(ky634) mutants is the same as in the wild-type background. These results suggest that mir-71 acts cell autonomously downstream of nsy-4 and nsy-5 to promote the AWCON identity.

The stability of mature mir-71 is dependent on nsy-4 and nsy-5

alg-1 mutants had overaccumulation of premature mir-71 and underaccumulation of mature mir-71, indicating that ALG-1/Argonaute-like protein is required for processing of mir-71 from premature form into the mature form [53]. alg-1(gk214) single mutants had wild-type str-2p::GFP expression. However, alg-1(gk214) significantly suppressed the 2AWCON phenotype of mir-71(OE) and caused a weak 2AWCOFF phenotype in alg-1(gk214);mir-71(OE) animals (p<0.001; Figure 1E). In addition, alg-1(gk214), like mir-71(n4115) mutants, also significantly suppressed the 2AWCON phenotype of tir-1(ky388ts) mutants (p<0.05; Figure 1E). These results suggest that alg-1 is required for mir-71 function in the AWCON cell.

Consistent with previous northern blot analysis [53], we found a significantly reduced level of mature mir-71 in alg-1(gk214) mutants (p<0.001; Figure S5A) using a stem-loop RT-PCR technique designed for specific quantification of mature miRNAs [54]. In addition, mature mir-71 was not detected in mir-71(n4115) mutants (Figure S5B), suggesting that mir-71(n4115) is a null allele. Since mir-71 is expressed broadly in the animal [48], [49] (Figure 3A), we introduced the AWC-expressing transgene odr-3p::mir-71 in mir-71(n4115) mutants and used stem-loop RT-PCR to assay the level of mature mir-71 mainly in AWC cells (Figure S5B).

To determine if the maturation and/or the stability of mir-71 in AWCs is regulated by the signaling molecules that act upstream of tir-1, we assayed the level of mature mir-71 in mir-71(n4115); nsy-4(ky627) double mutants, mir-71(n4115); nsy-5(ky634) double mutants, and mir-71(n4115); unc-36(e251) double mutants containing the AWC mir-71(OE) transgene using stem-loop RT-PCR (Text S1). The level of mature mir-71 was significantly reduced in nsy-4(ky627) (p = 0.015) and nsy-5(ky634) (p<0.0001) mutants compared with control, but was not significantly different between control and unc-36(e251) mutants (Figure S5B). The decreased level of mature mir-71 was not due to reduced transmission rates of the odr-3p::mir-71 transgene (Figure S6A) or downregulation of the odr-3 promoter in nsy-4(ky627) and nsy-5(ky634) mutants (Figure S6B). These results suggest that nsy-4 and nsy-5 are required for the generation and/or the stability of mature mir-71.

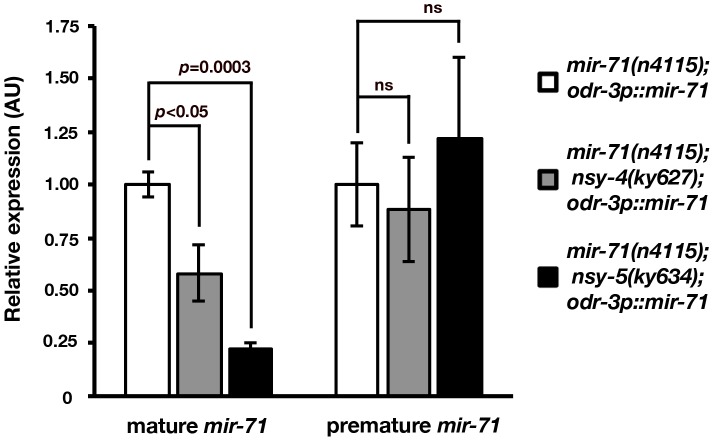

To further determine whether nsy-4 and nsy-5 regulate the formation and/or the stability of mature mir-71, we performed stem-loop RT-qPCR to quantify the level of premature and mature mir-71 in mir-71(n4115) mutants, mir-71(n4115); nsy-4(ky627) double mutants, and mir-71(n4115); nsy-5(ky634) double mutants containing the AWC mir-71(OE) transgene. Consistent with stem-loop RT-PCR results (Figure S5B), the abundance of mature mir-71 was significantly decreased in nsy-4(ky627) (p<0.05) and nsy-5(ky634) (p = 0.0003) mutants (Figure 6). However, the level of premature mir-71 was not significantly different between control and nsy-4(ky627) as well as nsy-5(ky634) mutants (Figure 6). These results suggest that the stability, but not the generation, of mature mir-71 is reduced in nsy-4(ky627) and nsy-5(ky634) mutants, and are consistent with a model in which nsy-4 and nsy-5 promotes the stability of mature mir-71 for downregulation of tir-1 in the future AWCON cell (Figure 7).

Figure 6. Mature mir-71 level is decreased in nsy-4 and nsy-5 mutants.

Stem-loop RT-qPCR analysis of mature and premature mir-71 expression in mir-71(n4115), mir-71(n4115); nsy-5(ky634), and mir-71(n4115); nsy-4(ky627) mutants expressing the odr-3p::mir-71 transgene in AWC. The expression levels of both premature and mature mir-71 were normalized to those of the actin-related gene, arx-1. AU, arbitrary unit. Relative expression was set to one for mir-71(n4115); odr3p::mir-71 and was normalized accordingly for other samples. p values were calculated using Student's t-test. ns, not significant (p = 0.6–0.7). Error bars represent standard error of the mean.

Figure 7. Model for mir-71 function in AWC asymmetry.

In the default AWCOFF cell, tir-1 acts in a calcium-regulated kinase signaling pathway to represses the expression of the AWCON marker str-2. Both nsy-4 and nsy-5 act to increase the level of mature mir-71, which results in downregulation of tir-1 expression and subsequent de-repression of str-2 gene expression in the cell that becomes AWCON. Gray is used to indicate the gene product is less active or inactive.

mir-71 is expressed at a higher level in the AWCON cell than in the AWCOFF cell (Figure 4A–4C), suggesting that mir-71 is differentially regulated at the transcriptional level in the two AWC cells. To determine if nsy-4 and nsy-5 also regulate differential expression levels of mir-71 between the two AWC cells, we crossed the transgene (Figure 4A–4C) containing mir-71p::GFP, ceh-36p::myr-TagRFP, and str-2p::2Xnls-TagRFP into nsy-4(ky627) and nsy-5(ky634) mutants. Since the AWCON marker str-2 is not expressed in nsy-4(ky627) or nsy-5(ky634) mutants, we analyzed and compared the expression levels of mir-71p::GFP between the two AWC cells in the mutants, instead of comparing the expression level between AWCON and AWCOFF (Figure 4A–4C). We found that mir-71 was also differentially expressed between the two AWC cells in nsy-4(ky627) and nsy-5(ky634) mutants (Figure S7), like in wild-type animals. These results suggest that differential regulation of mir-71 transcription in the two AWC cells is not dependent on nsy-4 or nsy-5.

Discussion

Stochastic cell fate acquisition in the nervous system is a conserved but poorly understood phenomenon [1]. Here, we report that the miRNA mir-71 is part of the pathway that controls stochastic left-right asymmetric differentiation of the C. elegans AWC olfactory neurons through downregulating the expression of tir-1, encoding the TIR-1/Sarm1 adaptor protein in a calcium signaling pathway. In addition, we have linked NSY-4/claudin- and NSY-5/innexin-dependent stability of mature mir-71 to downregulation of calcium signaling in stochastic AWC neuronal asymmetry. Previous studies have identified the role of miRNAs in reproducible, lineage-based asymmetry of the C. elegans ASE taste neuron pair, in which the miRNA expression pattern is largely fixed along the left-right axis [8], [9], [55]. This study provides one of the first insights into miRNA function in stochastic left-right asymmetric neuronal differentiation, in which the miRNA expression pattern is not fixed and is likely regulated by the stochastic signaling event driving random asymmetry.

The seed match between mir-71 and the tir-1 3′ UTR is conserved between C. elegans and C. briggsae. However, the str-2 promoters share little sequence similarity between C. elegans and C. briggsae. The C. elegans str-2 promoter GFP reporter, when expressed in C. briggsae, does not show detectable GFP expression in AWC neurons in embryos, first stage larvae, or adults (data not shown). This result suggests that the transcriptional regulation of str-2 has diverged in C. briggsae.

mir-71 has been implicated in various cell biological and developmental processes including promotion of longevity, resistance to heat and oxidative stress, DNA damage response, control of developmental timing, dauer formation, and recovery from dauer [47], [56]–[60]. However, it is largely unknown how mir-71 functions to regulate these biological processes. RNA interference (RNAi) of tir-1 did not affect C. elegans longevity [61], suggesting that mir-71 may regulate distinct target genes for different functions.

miRNAs are important post-transcriptional and translational regulators of gene expression during development and disease. Several miRNA target prediction algorithms such as MicroCosm Targets, TargetScan, PicTar, and mirWIP provide useful tools with which to identify potential target genes of miRNAs [62]. However, many miRNAs have redundant functions and therefore give subtle or no phenotypes when mutated [37]–[40]. Overexpression approach or phenotypic analysis of miRNA mutants in sensitized genetic backgrounds have been successful in elucidating the role of miRNAs for which null mutants are not available or functional redundancy is a potential problem [5], [8], [38]–[40], [42], [63]–[65]. Using miRNA target prediction programs, we identified mir-71 and five other miRNAs as potential regulators of the calcium-regulated UNC-43 (CaMKII)/TIR-1/NSY-1 (MAPKKK) signaling pathway. Through an overexpression approach and functional analysis of mir-71(n4115) mutants in sensitized genetic backgrounds, we revealed the role of mir-71 in genetic control of the AWCON identity.

miRNAs that share the same sequence identity in their seed regions and could be potentially capable of downregulating the same set of target genes are grouped as members of a family [66]–[69]. Some miRNA family members have been shown to function redundantly and work together to regulate specific developmental processes [37], [38], [70]–[74]. However, many families of miRNAs did not show synthetic phenotypes, indicating that most miRNA families act redundantly with other miRNAs, miRNA families, or non-miRNA genes [38]. Since there is only one mir-71 family member identified, the absence of an AWC phenotype in mir-71(n4115) single mutants suggests that mir-71 may act redundantly with other miRNA family members or non-miRNA genes to regulate calcium signaling in AWC asymmetry. dcr-1, encoding the ribonuclease III enzyme Dicer, is required for processing of premature miRNAs to mature miRNAs [28]. dcr-1(ok247) null mutants had wild-type AWC asymmetry (data not shown). This result suggests that the dcr-1 mutation may cause simultaneous knockdown of several miRNAs (including mir-71) with opposite functions in AWC asymmetry, thereby masking the role of mir-71 and its redundant miRNAs in AWC asymmetry.

The UNC-76 axon guidance molecule and NSY-4 claudin-like protein act to antagonize the calcium-regulated signaling pathway to generate the AWCON identity [12], [19]. We found that mir-71(n4115) mutants significantly suppressed the 2AWCON phenotype of nsy-4(OE) and enhanced the 2AWCOFF phenotype of nsy-4(ky627) and unc-76(e911) mutants. These results suggest an alternative mechanism for functional redundancy of mir-71 in AWC asymmetry. mir-71 may act in parallel with other regulatory pathways downstream of unc-76 and nsy-4 to downregulate the calcium signaling pathway in the AWCON cell. Functional redundancy of miRNAs and other regulatory pathways has been demonstrated by a previous study suggesting that Drosophila miR-7 may act in parallel with a protein-turnover mechanism to downregulate the transcriptional repressor Yan in the fly eye [42].

Our results suggest that mir-71 is regulated at transcriptional and post-transcriptional levels in AWC. At the transcriptional level, mir-71 is expressed at a higher level in the AWCON cell than in the AWCOFF cell. This transcriptional bias of mir-71 is not dependent on NSY-4 claudin-like protein or NSY-5 innexin gap junction protein. The mechanisms that regulate differential expression of mir-71 in the two AWC cells are yet to be elucidated. At the post-transcriptional level, the stability of mature mir-71 is dependent on nsy-4 and nsy-5. It is possible that nsy-4 and nsy-5 may antagonize the miRNA turnover pathway to increase the level of mature mir-71. The C. elegans 5′→3′ exoribonuclease XRN-2 has been implicated in degradation of mature miRNAs released from Argonaute [75]. However, xrn-2(RNAi) animals did not show AWC phenotypes (data not shown), suggesting that the stability of mature mir-71 may be independent of xrn-2.

The TIR-1/Sarm1 adaptor protein assembles a calcium-regulated signaling complex at synaptic regions to regulate the default AWCOFF identity [16]. Downregulation of the TIR-1 adaptor protein by mir-71 and other parallel pathways may represent an efficient mechanism to inhibit calcium signaling in the cell becoming AWCON. Calcium signaling is one of the most common and conserved systems that control a wide range of processes including fertilization, embryonic pattern formation, cell proliferation, cell differentiation, learning and memory, and cell death during development and in adult life [76]. In addition, calcium signaling is implicated in left-right patterning in several tissues of different organisms [77]. It has been shown that negative regulation of calcium signaling by miRNAs is important for normal development and health [78]–[81]. In summary, our study and the studies from other labs demonstrate that downregulation of calcium signaling by miRNAs is one of the important mechanisms for cellular and developmental processes.

Materials and Methods

Strains

Wild-type strains were C. elegans variety Bristol, strain N2. Worm strains were generated and maintained by standard methods [82]. Mutations and integrated transgenes used are as follows: kyIs140 [str-2p::GFP; lin-15(+)] I [12], kyIs323 [str-2p::GFP; ofm-1p::GFP] II [22], oyIs44 [odr-1p::DsRed] V [51], kyIs136 [str-2p::GFP; lin-15(+)] X [12], mir-71(n4115) I [40], nsy-5(ky634) I [18], ppfr-1(tm2180) unc-29(e1072) I (gift from P. Mains, University of Calgary, Canada) [43], rol-6(e187) II, tir-1(ky388ts) III [16], tir-1(ky648gf) III, tir-1(tm3036) III [22], unc-36(e251) III, dcr-1(ok247) III; nsy-4(ky616) IV, nsy-4(ky627) IV [19], unc-43(n498gf) IV, eri-1(mg366 IV), unc-76(e911) V, lin-15b(n744) X, and alg-1(gk214) X.

Transgenes maintained as extrachromosomal arrays include kyEx1127 [odr-3p::nsy-4; myo-3p::DsRed] [18], vyEx149 [odr-3p::mir-71 (25 ng/µl); ofm-1p::DsRed (20 ng/µl)], vyEx187 [mir-71p::YFP (50 ng/µl); elt-2p::CFP (5 ng/µl)], vyEx527, 528 [odr-3p::mir-71 (50 ng/µl); odr-1p::DsRed (12 ng/µl); ofm-1p::DsRed (30 ng/µl)], vyEx605, 606 [odr-3p::GFP::tir-1 3′ UTR (7.5 ng/µl); elt-2p::CFP (7.5 ng/µl)], vyEx611, 615 [odr-3p::GFP::unc-54 3′ UTR (7.5 ng/µl); elt-2p::CFP (7.5 ng/µl)], vyEx647 [odr-3p::GFP::nsy-1 3′ UTR (7.5 ng/µl); elt-2p::CFP (7.5 ng/µl)], vyEx649, 651 [odr-3p::GFP::tir-1 3′ UTRmut (7.5 ng/µl); elt-2p::CFP (7.5 ng/µl)], vyEx835, 836, 838 [odr-3p::tir-1::tir-1 3′ UTRmut (70 ng/µl); elt-2p::CFP (7.5 ng/µl)], vyEx703, 720 [odr-3p::tir-1::tir-1 3′ UTR (70 ng/µl); elt-2p::CFP (7.5 ng/µl)], vyEx905, 907 [odr-3p::mir-74 (50 ng/µl); ofm-1p::DsRed (30 ng/µl)], vyEx914, 917 [odr-3p::mir-248 (50 ng/µl); ofm-1p::DsRed (30 ng/µl)], vyEx915, 918 [odr-3p::mir-72 (50 ng/µl); ofm-1::DsRed (30 ng/µl)], vyEx916, 920, 921 [odr-3p::mir-228 (50 ng/µl); ofm-1p::DsRed (30 ng/µl)], vyEx922, 923, 924 [odr-3p::mir-255 (50 ng/µl); ofm-1::DsRed (30 ng/µl)], vyEx927, 931 [mir-71p::GFP (10 ng/µl); ceh-36p::myr-TagRFP (5 ng/µl); str-2p::2Xnls-TagRFP (25 ng/µl); ofm-1p::DsRed (30 ng/µl)], vyEx1316, 1317 [mir-71p::NZGFP (30 ng/µl); odr-3p::CZGFP (15 ng/µl); str-2p::2Xnls-TagRFP (25 ng/µl); ofm-1p::DsRed (30 ng/µl)), vyEx1318, 1319 [nsy-5p::mir-248IR (100 ng/µl); odr-1p::DsRed (15 ng/µl); ofm-1p::DsRed (30 ng/µl)], vyEx1065 [str-2p::myr-mCherry (100 ng/µl); ofm-1p::DsRed (30 ng/µl)], vyEx1097 [odr-3p::2Xnls-TagRFP (40 ng/µl); pRF4(rol-6(su1006) (50 ng/µl)], vyEx1351, 1352 [odr-3p::tir-1 5′ UTR::GFP::tir-1 3′ UTR (15 ng/µl); odr 3p::TagRFP::unc-54 3′UTR (15 ng/µl); elt-2p::CFP (7.5 ng/µl)], and vyEx1353, 1375 [odr-3p::tir-1 5′UTR::GFP::tir-1 3′ UTRmut (15 ng/µl); odr 3p::TagRFP::unc-54 3′ UTR (15 ng/µl); elt-2p::CFP (7.5 ng/µl)].

Plasmid construction and germ line transformation

A 2476 bp PCR fragment of mir-71 promoter was subcloned to make mir-71p::YFP and mir-71p::GFP. mir-71p::NZGFP was made by replacing GFP in mir-71p::GFP with a NZGFP fragment from TU#710 (Addgene) [52]. odr-3p::CZGFP was made by cloning a CZGFP fragment from TU#711 (Addgene) [52] into an odr-3p vector. ceh-36p::myr-TagRFP, in which the 1852 bp ceh-36 promoter drives expression of myristoylated TagRFP, was generated by replacing TagRFP in ceh-36p::TagRFP [83] with myr-TagRFP. odr-3p::2Xnls-TagRFP was made by replacing the str-2 promoter in str-2p::2Xnls-TagRFP [22] with the odr-3 promoter [41]. str-2p::myr-mCherry was generated by replacing GFP in str-2p::GFP [12] with a myr-mCherry fragment. A 94 bp mir-71 PCR fragment was subcloned to make odr-3p::mir-71. A 561 bp PCR fragment of the tir-1 3′ UTR, which represents the average length of the 3′ UTR in the majority of identified tir-1 cDNA clones such as yk1473h08 (www.wormbase.org), was subcloned to make odr-3p::tir-1::tir-1 3′ UTR and odr-3p::GFP::tir-1 3′ UTR. miRNA target prediction algorithms including MicroCosm Targets, PicTar, and mirWIP use 300–590 bp of tir-1 3′ UTR for analysis. The predicted mir-71 binding site, TCTTTC, in the tir-1 3′ UTR was mutated into CAGGCA using QuikChange II XL Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit (Stratagene) to make odr-3p::GFP::tir-1 3′ UTRmut. tir-1a splice form was used for all tir-1 constructs. odr-3p::tir-1 5′ UTR::GFP::tir-1 3′ UTR was made by cloning a 150 bp PCR fragment of tir-1 5′ UTR, amplified from wild-type embryo cDNA, into the odr-3p::GFP::tir-1 3′ UTR. odr-3p::tir-1 5′ UTR::GFP::tir-1 3′ UTRmut was made by replacing GFP::tir-1 3′ UTR in the odr-3p::tir-1 5′ UTR::GFP::tir-1 3′ UTR with GFP::tir-1 3′ UTRmut. To make shRNA anti-mir-248 (mir-248IR), the sense and antisense oligos, each consisting of mir-248 sense (24 nt) and antisense (24 nt) sequences that flank a 12 nt linker (loop) sequence, were designed (SBI System Biosciences) and annealed (IDT) as described. This hairpin construct was subcloned to make nsy-5p::mir-248IR. To generate transgenic strains, DNA constructs were injected into the syncytial gonad of adult worms as previously described [84].

Quantification of fluorescence intensity

Z-stack images of transgenic animals expressing fluorescent markers were acquired using a Zeiss Axio Imager Z1 microscope equipped with a motorized focus drive and a Zeiss AxioCam MRm CCD digital camera. All animals of each set of experiments had the same exposure time for comparison of fluorescence intensity. The single focal plane with the brightest fluorescence in each AWC cell was selected from the acquired image stack and measured for fluorescence intensity. To measure fluorescence intensity, the outline spline tool in the Zeiss AxioVision Rel 4.7 image analysis software was used to draw around the AWC cell body (Figure 2B; Figure 4A, 4B, 4D, 4E; Figure S4A, S4B; and Figure S6B) or nucleus (Figure 2B, Figure 4D′ and 4E′) from captured images. To measure fluorescence intensity in dim GFP-expressing cells (Figure 4B and Figure S4B), the display contrast and brightness were adjusted to visualize and outline the cells. For each category of animals, images from a minimum of 10 animals were collected and analyzed.

Genetic mosaic analysis

Mosaic analysis was performed as previously described [13], [18], [19], [25]. Transgenic lines expressing the odr-3p::mir-71; odr-1p::DsRed transgene were passed for minimum of six generations before scoring for mosaic animals. The same transgenic lines were crossed into nsy-4(ky627) and nsy-5(ky634) mutants for the analysis.

qPCR for determining the relative transgene copy number

Three adult hermaphrodites from each tir-1(OE) transgene line were collected in 25 µl of worm lysis buffer (50 mM KCl, 0.01% gelatin, 10 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.3, 0.45% Tween 20, 0.45% NP-40, 2.5 mM MgCl2, 100 µg/ml Proteinase K). Collected worms were then incubated at −80°C for minimum of one hour, 65°C for one hour, and 95°C for 15 minutes. 5 µl of the worm lysate was used for subsequent qPCR with Fast SYBR Green Master Mix (Invitrogen). qPCR reactions were run in triplicate at 95°C for 3 minutes, followed by 45 cycles of 95°C for 30 seconds, 57°C for 30 seconds, and 72°C for 30 seconds on the CFX96 Real-Time PCR Detection System (Bio-Rad). PCR product was scanned for fluorescent signal at the end of each cycle and the C(T) values were obtained using the CFX Manager Software (Bio-Rad). The relative tir-1(OE) transgene copy number was determined using the 2[−Delta Delta C(T)] method as previously described [85] with the actin-related gene, arx-1, as internal control.

Stem-loop RT–qPCR of premature and mature mir-71

Stem-loop RT-qPCR was performed as described [54] to detect and quantify relative expression levels of premature and mature mir-71. The odr-3p::mir-71 transgenes used in genetic mosaic analysis were crossed into various genetic backgrounds. Total RNA samples were isolated from first stage larvae using RNeasy Mini kit (QIAGEN). Reverse transcription (RT) reactions were performed with 1 µg of total RNA, SuperScript III reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen), and RT primer (oligo d(T)18, premature mir-71 stem-loop RT primer, or mature mir-71 stem-loop RT primer). 1 µl of 1∶35 diluted reverse transcription product was used as template for subsequent qPCR reactions with Fast SYBR Green Master Mix (Invitrogen). All PCR reactions were run in triplicate at 95°C for 3 minutes, followed by 45 cycles of 95°C for 30 seconds, 51°C for 30 seconds, and 72°C for 30 seconds on the CFX96 Real-Time PCR Detection System (Bio-Rad). PCR product was scanned for fluorescent signal at the end of each cycle and the C(T) values were obtained using the CFX Manager Software (Bio-Rad). The actin-related gene, arx-1, was used as internal control to normalize variation between samples. Relative expression of premature and mature mir-71 was analyzed using the 2[−Delta Delta C(T)] method as previously described [85]. Relative expression was set to one for mir-71(n4115); odr3p::mir-71 and was normalized accordingly for other samples. Student's t-test was used to calculate statistical significance.

Supporting Information

miRNAs predicted to target genes in the AWC calcium-mediated signaling pathway. (A) A list of miRNAs and target genes identified by four miRNA target prediction programs. Only the prediction that fits the two indicated criteria is listed. (B) AWC phenotypes caused by overexpression of candidate miRNAs listed in (A).

(TIF)

The effect of mir-71 on GFP sensor constructs with the tir-1 3′ UTR or the nsy-1 3′ UTR. (A) Normalized GFP intensity in wild type and mir-71(n4115) mutants carrying the transgene of GFP sensor constructs with the tir-1 3′ UTR or the unc-54 3′ UTR (as negative control). (B) Normalized GFP intensity in wild type and mir-71(OE) animals expressing the transgene of a GFP sensor construct with the nsy-1 3′ UTR.

(TIF)

The tir-1 5′ UTR does not affect mir-71(OE)-mediated downregulation of gene expression through the tir-1 3′ UTR. (A, B) The average normalized GFP intensity in the AWC cell body of sensor constructs, driven by the odr-3 promoter and the tir-1 5′ UTR, with the tir-1 3′ UTR (A) or the tir-1 3′ UTR mutated in the predicted mir-71 target site (B), in wild type and mir-71(OE) animals. The GFP intensity of an individual cell was normalized to the TagRFP intensity of the internal control transgene odr-3p::2Xnls-TagRFP::unc-54 3′ UTR in the same cell in the first larval stage. For each sensor construct, the normalized GFP intensity in wild type was set as 1 arbitrary unit (AU) and the normalized GFP intensity in mir-71(OE) was calibrated to that in wild type. Two independent lines were analyzed for each sensor construct. Student's t-test was used for statistical analysis. Error bars, standard error of the mean. ns, not significant.

(TIF)

The expression level of mir-71 is higher in the AWCON cell than in the AWCOFF cell. (A, B) Images of recGFP expressed from mir-71p::NZGFP and odr-3p::CZGFP. (A′, B′) Images of str-2p::2Xnls-TagRFP. AWCON was identified as str-2p::2Xnls-TagRFP positive (A′). AWCOFF was identified as str-2p::2Xnls-TagRFP negative (B′). (A″) Merge of A and A′ images from the same cell. (B″) Merge of B and B′ images from the same cell. (C) Quantification of recGFP expression in AWCON and AWCOFF cells. All images were taken from first stage larvae. The single focal plane with the brightest fluorescence in each AWC was selected from the acquired image stack and measured for fluorescence intensity. Each animal was categorized into one of three categories: AWCON = AWCOFF, AWCON>AWCOFF, and AWCOFF>AWCON based on the comparison of recGFP intensities between AWCON and AWCOFF cells of the same animal. We did not observe any animals that fell into the “AWCON = AWCOFF” category from our recGFP intensity analysis. Total number of animals for each category was tabulated and analyzed as described [86]. p-values were calculated using X 2 test. Error bars represent standard error of proportion. Scale bar, 2 µm.

(TIF)

Stem-loop RT-PCR analysis of mature mir-71 levels. (A, B) Representative images of stem-loop RT-PCR product of total RNA samples from adult worms (A) or enriched first stage larvae (B) in different genetic backgrounds. + and − indicate the presence and absence of the transgene odr-3p::mir-71, respectively. The actin-related gene arx-1 was used as internal control to normalize the abundance of mature mir-71. All PCR reactions were run in triplicate. p values were calculated using Student's t-test. ns, not significant. Error bars represent standard error of the mean.

(TIF)

Control experiments to demonstrate that a decreased level of mature mir-71 in nsy-4(ky627) and nsy-5(ky634) mutants is not caused by a reduced transmission rate of the odr-3p::mir-71 extrachromosomal array or reduced activity of the odr-3 promoter. (A) Transmission rates of the odr-3p::mir-71 extrachromosomal array in mir-71(n4115), mir-71(n4115);nsy-4(ky627), and mir-71(n4115);nsy-5(ky634) mutants. Error bars represent the standard error of proportion. (B) Top: Representative images of odr-3p::GFP expression in AWC neurons of wild type, nsy-4(ky627), and nsy-5(ky634) mutants at the first larval stage. Bottom: The average intensity of GFP in AWC neurons. Results from two independent odr-3p::GFP transgenic lines are shown. Error bars represent standard error of the mean. Scale bar, 10 µm.

(TIF)

Differential expression of mir-71 in the two AWC cells is not dependent on nsy-4 or nsy-5. The GFP intensity of mir-71p::GFP was compared between the two AWC cells of the same animal in wild-type, nsy-4(ky627), and nsy-5(ky634) mutants. The percentage difference of mir-71p::GFP expression between the two AWC cells was determined by dividing the higher GFP intensity with the lower GFP intensity. Error bars represent the standard error of proportion.

(TIF)

Supplemental Methods: Quantification of mature mir-71 by stem-loop RT–PCR.

(DOCX)

Acknowledgments

We thank members of the Chuang and Chang labs for valuable discussions; Felicia Ciamacco, Brittany Bayne, and Kalyn Campbell for technical assistance; Yan Zou for wild-type and alg-1(gk214) RNA samples; and Jennifer Tucker for comments on the manuscript. We also thank Andy Fire for C. elegans vectors, Baris Tursun and Oliver Hobert (Columbia University Medical Center, NY) for the ceh-36p::TagRFP plasmid, the C. elegans Genetic Center for C. elegans strains, and the WormBase for readily accessible information.

Footnotes

The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

C-FC was funded by a Whitehall Foundation Research Award, an Alfred P. Sloan Research Fellowship, and NIH grant R01 GM098026. CC was funded by a Whitehall Foundation Research Award and March of Dimes Foundation. Y-WH was supported by an NIH Organogenesis Training Grant. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Johnston RJ, Jr, Otake Y, Sood P, Vogt N, Behnia R, et al. Interlocked feedforward loops control cell-type-specific Rhodopsin expression in the Drosophila eye. Cell. 2011;145:956–968. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jukam D, Desplan C. Binary fate decisions in differentiating neurons. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2010;20:6–13. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2009.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Johnston RJ, Jr, Desplan C. Stochastic neuronal cell fate choices. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2008;18:20–27. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2008.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hobert O. Neurogenesis in the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. WormBook. 2010:1–24. doi: 10.1895/wormbook.1.12.2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yoo AS, Greenwald I. LIN-12/Notch activation leads to microRNA-mediated down-regulation of Vav in C. elegans. Science. 2005;310:1330–1333. doi: 10.1126/science.1119481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grandbarbe L, Bouissac J, Rand M, Hrabe de Angelis M, Artavanis-Tsakonas S, et al. Delta-Notch signaling controls the generation of neurons/glia from neural stem cells in a stepwise process. Development. 2003;130:1391–1402. doi: 10.1242/dev.00374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.MacDonald HR, Wilson A, Radtke F. Notch1 and T-cell development: insights from conditional knockout mice. Trends Immunol. 2001;22:155–160. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4906(00)01828-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chang S, Johnston RJ, Jr, Frokjaer-Jensen C, Lockery S, Hobert O. MicroRNAs act sequentially and asymmetrically to control chemosensory laterality in the nematode. Nature. 2004;430:785–789. doi: 10.1038/nature02752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Johnston RJ, Hobert O. A microRNA controlling left/right neuronal asymmetry in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature. 2003;426:845–849. doi: 10.1038/nature02255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Johnston RJ, Jr, Hobert O. A novel C. elegans zinc finger transcription factor, lsy-2, required for the cell type-specific expression of the lsy-6 microRNA. Development. 2005;132:5451–5460. doi: 10.1242/dev.02163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Poole RJ, Hobert O. Early embryonic programming of neuronal left/right asymmetry in C. elegans. Curr Biol. 2006;16:2279–2292. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.09.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Troemel ER, Sagasti A, Bargmann CI. Lateral signaling mediated by axon contact and calcium entry regulates asymmetric odorant receptor expression in C. elegans. Cell. 1999;99:387–398. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81525-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bauer Huang SL, Saheki Y, VanHoven MK, Torayama I, Ishihara T, et al. Left-right olfactory asymmetry results from antagonistic functions of voltage-activated calcium channels and the Raw repeat protein OLRN-1 in C. elegans. Neural Dev. 2007;2:24. doi: 10.1186/1749-8104-2-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Colosimo ME, Brown A, Mukhopadhyay S, Gabel C, Lanjuin AE, et al. Identification of thermosensory and olfactory neuron-specific genes via expression profiling of single neuron types. Curr Biol. 2004;14:2245–2251. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.12.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wes PD, Bargmann CI. C. elegans odour discrimination requires asymmetric diversity in olfactory neurons. Nature. 2001;410:698–701. doi: 10.1038/35070581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chuang CF, Bargmann CI. A Toll-interleukin 1 repeat protein at the synapse specifies asymmetric odorant receptor expression via ASK1 MAPKKK signaling. Genes Dev. 2005;19:270–281. doi: 10.1101/gad.1276505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.White JG, Southgate E, Thomson JN, Brenner S. The structure of the nervous system of Caenorhabditis elegans. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 1986;314:1–340. doi: 10.1098/rstb.1986.0056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chuang CF, Vanhoven MK, Fetter RD, Verselis VK, Bargmann CI. An innexin-dependent cell network establishes left-right neuronal asymmetry in C. elegans. Cell. 2007;129:787–799. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.02.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.VanHoven MK, Bauer Huang SL, Albin SD, Bargmann CI. The claudin superfamily protein nsy-4 biases lateral signaling to generate left-right asymmetry in C. elegans olfactory neurons. Neuron. 2006;51:291–302. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.06.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lesch BJ, Bargmann CI. The homeodomain protein hmbx-1 maintains asymmetric gene expression in adult C. elegans olfactory neurons. Genes Dev. 2010;24:1802–1815. doi: 10.1101/gad.1932610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lesch BJ, Gehrke AR, Bulyk ML, Bargmann CI. Transcriptional regulation and stabilization of left-right neuronal identity in C. elegans. Genes Dev. 2009;23:345–358. doi: 10.1101/gad.1763509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chang C, Hsieh YW, Lesch BJ, Bargmann CI, Chuang CF. Microtubule-based localization of a synaptic calcium-signaling complex is required for left-right neuronal asymmetry in C. elegans. Development. 2011;138:3509–3518. doi: 10.1242/dev.069740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Taylor RW, Hsieh YW, Gamse JT, Chuang CF. Making a difference together: reciprocal interactions in C. elegans and zebrafish asymmetric neural development. Development. 2010;137:681–691. doi: 10.1242/dev.038695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Welker NC, Habig JW, Bass BL. Genes misregulated in C. elegans deficient in Dicer, RDE-4, or RDE-1 are enriched for innate immunity genes. Rna. 2007;13:1090–1102. doi: 10.1261/rna.542107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sagasti A, Hisamoto N, Hyodo J, Tanaka-Hino M, Matsumoto K, et al. The CaMKII UNC-43 activates the MAPKKK NSY-1 to execute a lateral signaling decision required for asymmetric olfactory neuron fates. Cell. 2001;105:221–232. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00313-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tanaka-Hino M, Sagasti A, Hisamoto N, Kawasaki M, Nakano S, et al. SEK-1 MAPKK mediates Ca2+ signaling to determine neuronal asymmetric development in Caenorhabditis elegans. EMBO Rep. 2002;3:56–62. doi: 10.1093/embo-reports/kvf001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bartel DP. MicroRNAs: genomics, biogenesis, mechanism, and function. Cell. 2004;116:281–297. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00045-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Grishok A, Pasquinelli AE, Conte D, Li N, Parrish S, et al. Genes and mechanisms related to RNA interference regulate expression of the small temporal RNAs that control C. elegans developmental timing. Cell. 2001;106:23–34. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00431-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bigelow HR, Wenick AS, Wong A, Hobert O. CisOrtho: a program pipeline for genome-wide identification of transcription factor target genes using phylogenetic footprinting. BMC Bioinformatics. 2004;5:27. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-5-27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kent WJ, Zahler AM. Conservation, regulation, synteny, and introns in a large-scale C. briggsae-C. elegans genomic alignment. Genome Res. 2000;10:1115–1125. doi: 10.1101/gr.10.8.1115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Enright AJ, John B, Gaul U, Tuschl T, Sander C, et al. MicroRNA targets in Drosophila. Genome Biol. 2003;5:R1. doi: 10.1186/gb-2003-5-1-r1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Griffiths-Jones S, Grocock RJ, van Dongen S, Bateman A, Enright AJ. miRBase: microRNA sequences, targets and gene nomenclature. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:D140–144. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkj112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Griffiths-Jones S, Saini HK, van Dongen S, Enright AJ. miRBase: tools for microRNA genomics. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:D154–158. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Grimson A, Farh KK, Johnston WK, Garrett-Engele P, Lim LP, et al. MicroRNA targeting specificity in mammals: determinants beyond seed pairing. Mol Cell. 2007;27:91–105. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.06.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lall S, Grun D, Krek A, Chen K, Wang YL, et al. A genome-wide map of conserved microRNA targets in C. elegans. Curr Biol. 2006;16:460–471. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.01.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hammell M, Long D, Zhang L, Lee A, Carmack CS, et al. mirWIP: microRNA target prediction based on microRNA-containing ribonucleoprotein-enriched transcripts. Nat Methods. 2008;5:813–819. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Abbott AL, Alvarez-Saavedra E, Miska EA, Lau NC, Bartel DP, et al. The let-7 MicroRNA family members mir-48, mir-84, and mir-241 function together to regulate developmental timing in Caenorhabditis elegans. Dev Cell. 2005;9:403–414. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2005.07.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Alvarez-Saavedra E, Horvitz HR. Many families of C. elegans microRNAs are not essential for development or viability. Curr Biol. 2010;20:367–373. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2009.12.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Brenner JL, Jasiewicz KL, Fahley AF, Kemp BJ, Abbott AL. Loss of individual microRNAs causes mutant phenotypes in sensitized genetic backgrounds in C. elegans. Curr Biol. 2010;20:1321–1325. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2010.05.062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Miska EA, Alvarez-Saavedra E, Abbott AL, Lau NC, Hellman AB, et al. Most Caenorhabditis elegans microRNAs are individually not essential for development or viability. PLoS Genet. 2007;3:e215. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0030215. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0030215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Roayaie K, Crump JG, Sagasti A, Bargmann CI. The G alpha protein ODR-3 mediates olfactory and nociceptive function and controls cilium morphogenesis in C. elegans olfactory neurons. Neuron. 1998;20:55–67. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80434-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Li X, Carthew RW. A microRNA mediates EGF receptor signaling and promotes photoreceptor differentiation in the Drosophila eye. Cell. 2005;123:1267–1277. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.10.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Han X, Gomes JE, Birmingham CL, Pintard L, Sugimoto A, et al. The role of protein phosphatase 4 in regulating microtubule severing in the Caenorhabditis elegans embryo. Genetics. 2009;181:933–943. doi: 10.1534/genetics.108.096016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chen J, Kastan MB. 5′-3′-UTR interactions regulate p53 mRNA translation and provide a target for modulating p53 induction after DNA damage. Genes & development. 2010;24:2146–2156. doi: 10.1101/gad.1968910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Franch T, Gultyaev AP, Gerdes K. Programmed cell death by hok/sok of plasmid R1: processing at the hok mRNA 3′-end triggers structural rearrangements that allow translation and antisense RNA binding. Journal of molecular biology. 1997;273:38–51. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1997.1294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Edgil D, Harris E. End-to-end communication in the modulation of translation by mammalian RNA viruses. Virus research. 2006;119:43–51. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2005.10.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Boulias K, Horvitz HR. The C. elegans microRNA mir-71 acts in neurons to promote germline-mediated longevity through regulation of DAF-16/FOXO. Cell metabolism. 2012;15:439–450. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2012.02.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Isik M, Korswagen HC, Berezikov E. Expression patterns of intronic microRNAs in Caenorhabditis elegans. Silence. 2010;1:5. doi: 10.1186/1758-907X-1-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Martinez NJ, Ow MC, Reece-Hoyes JS, Barrasa MI, Ambros VR, et al. Genome-scale spatiotemporal analysis of Caenorhabditis elegans microRNA promoter activity. Genome Res. 2008;18:2005–2015. doi: 10.1101/gr.083055.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kratsios P, Stolfi A, Levine M, Hobert O. Coordinated regulation of cholinergic motor neuron traits through a conserved terminal selector gene. Nat Neurosci. 2011 doi: 10.1038/nn.2989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lanjuin A, VanHoven MK, Bargmann CI, Thompson JK, Sengupta P. Otx/otd homeobox genes specify distinct sensory neuron identities in C. elegans. Dev Cell. 2003;5:621–633. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(03)00293-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhang S, Ma C, Chalfie M. Combinatorial marking of cells and organelles with reconstituted fluorescent proteins. Cell. 2004;119:137–144. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hammell CM, Lubin I, Boag PR, Blackwell TK, Ambros V. nhl-2 Modulates microRNA activity in Caenorhabditis elegans. Cell. 2009;136:926–938. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.01.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Chen C, Ridzon DA, Broomer AJ, Zhou Z, Lee DH, et al. Real-time quantification of microRNAs by stem-loop RT-PCR. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:e179. doi: 10.1093/nar/gni178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Johnston RJ, Jr, Chang S, Etchberger JF, Ortiz CO, Hobert O. MicroRNAs acting in a double-negative feedback loop to control a neuronal cell fate decision. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:12449–12454. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0505530102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.de Lencastre A, Pincus Z, Zhou K, Kato M, Lee SS, et al. MicroRNAs both promote and antagonize longevity in C. elegans. Curr Biol. 2010;20:2159–2168. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2010.11.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Pincus Z, Smith-Vikos T, Slack FJ. MicroRNA predictors of longevity in Caenorhabditis elegans. PLoS Genet. 2011;7:e1002306. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002306. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Karp X, Hammell M, Ow MC, Ambros V. Effect of life history on microRNA expression during C. elegans development. Rna. 2011;17:639–651. doi: 10.1261/rna.2310111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kato M, de Lencastre A, Pincus Z, Slack FJ. Dynamic expression of small non-coding RNAs, including novel microRNAs and piRNAs/21U-RNAs, during Caenorhabditis elegans development. Genome Biol. 2009;10:R54. doi: 10.1186/gb-2009-10-5-r54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zhang X, Zabinsky R, Teng Y, Cui M, Han M. microRNAs play critical roles in the survival and recovery of Caenorhabditis elegans from starvation-induced L1 diapause. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2011;108:17997–18002. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1105982108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Liberati NT, Fitzgerald KA, Kim DH, Feinbaum R, Golenbock DT, et al. Requirement for a conserved Toll/interleukin-1 resistance domain protein in the Caenorhabditis elegans immune response. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2004;101:6593–6598. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0308625101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bartel DP. MicroRNAs: target recognition and regulatory functions. Cell. 2009;136:215–233. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ambros V. The functions of animal microRNAs. Nature. 2004;431:350–355. doi: 10.1038/nature02871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Chen CZ, Li L, Lodish HF, Bartel DP. MicroRNAs modulate hematopoietic lineage differentiation. Science. 2004;303:83–86. doi: 10.1126/science.1091903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Zhao Z, Boyle TJ, Liu Z, Murray JI, Wood WB, et al. A negative regulatory loop between microRNA and Hox gene controls posterior identities in Caenorhabditis elegans. PLoS Genet. 2010;6:e1001089. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1001089. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1001089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ruby JG, Jan C, Player C, Axtell MJ, Lee W, et al. Large-scale sequencing reveals 21U-RNAs and additional microRNAs and endogenous siRNAs in C. elegans. Cell. 2006;127:1193–1207. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.10.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ibanez-Ventoso C, Vora M, Driscoll M. Sequence relationships among C. elegans, D. melanogaster and human microRNAs highlight the extensive conservation of microRNAs in biology. PLoS ONE. 2008;3:e2818. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002818. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Lagos-Quintana M, Rauhut R, Meyer J, Borkhardt A, Tuschl T. New microRNAs from mouse and human. RNA. 2003;9:175–179. doi: 10.1261/rna.2146903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]