Abstract

Among dopamine receptors, the expression and function of the D3 receptor subtype is not well understood. The receptor has the highest affinity for dopamine and many drugs that target dopamine receptors. In this paper, we examined, at the single cell level, the characteristics of D3 receptor-expressing cells isolated from different brain regions of male and female mice that were either 35 or 70 days old. The brain regions included nucleus accumbens, Islands of Calleja, olfactory tubercle, retrosplenial cortex, dorsal subiculum, mammillary body, amygdala and septum. The expression analysis was done in the drd3-enhanced green fluorescent protein transgenic mice that report the endogenous expression of D3 receptor mRNA. Using single cell reverse transcriptase PCR, we determined if the D3 receptor-expressing fluorescent cells in these mice were neurons or glia and if they were glutamatergic, GABAergic or catecholaminergic. Next, we determined if the fluorescent cells co-expressed the four other dopamine receptor subtypes, adenylate cyclase V (ACV) isoform, and three different isoforms of G protein-coupled inward rectifier potassium (GIRK) channels. The results suggest that D3 receptor is expressed in neurons, with region-specific expression in glutamatergic and GABAergic neurons. The D3 receptor primarily co-expressed with D1 and D2 dopamine receptors with regional, sex and age-dependent differences in the co-expression pattern. The percentage of cells co-expressing D3 receptor and ACV or GIRK channels varied significantly by brain region, sex and age. The molecular characterization of D3 receptor-expressing cells in mouse brain reported here will facilitate the characterization of D3 receptor function in physiology and pathophysiology.

Keywords: Expression, Structure and function, Working memory, Limbic, Reward, Addiction, Anxiety, Periadolescent

Introduction

The neurotransmitter dopamine controls a wide variety of physiological and behavioral functions in mammals via five major subtypes of dopamine receptors (Missale et al. 1998). They are broadly classified into the “D1-like” and “D2-like” dopamine receptors based on pharmacology and function. The former consists of D1 and D5 receptors, while the latter consists of D2, D3 and D4 receptors. In heterologous expression systems, the D2-like dopamine receptors couple to and modulate adenylyl cyclases, ion channels and protein kinases (Neve et al. 2004). In cell lines, activation of D3 receptors decreases cAMP levels specifically by the inhibition of the adenylyl cyclase V (ACV) isoform (Robinson and Caron 1997). Other D3 receptor-initiated signaling events have been reported, including phosphorylation of mitogen-activated proteins kinases (Cussac et al. 1999), regulation of Na+/H+ exchanger (Chio et al. 1994; Cox et al. 1995), mitogenesis in CHO cells (Chio et al. 1994), induction of c-Fos expression (Pilon et al. 1994), increased extracellular acidification (Cox et al. 1995) and melanocyte aggregation (Potenza et al. 1994). D2 and D3 dopamine receptors also modulate potassium and calcium channel function (Seabrook et al. 1994; Werner et al. 1996). We have shown that transfected D3 receptors can couple robustly to natively expressed G protein-coupled inward rectifier potassium (GIRK) channels and P/Q-type calcium channels, as well as inhibit firing of spontaneous action potentials and spontaneous secretory activity in the AtT-20 neuroendocrine cell line (Kuzhikandathil et al. 1998; Kuzhikandathil and Oxford 1999, 2000). While the signal transduction pathways of D3 dopamine receptor have been well described and characterized in heterologous expression system, its in vivo signaling function is less well understood (Ahlgren-Beckendorf and Levant 2004). Several factors have contributed to this deficit, including the lack of selective agonists that can distinguish the D3 receptor from the closely related D2 and D4 dopamine receptors, as well as its relatively limited expression pattern in the brain.

Previous dopamine receptor expression studies have been primarily done at the regional level in the brain using immunohistochemistry or in situ hybridization (Ariano 1997). Based on these methods, the expression of D3 receptors in the rodent brain is specifically distributed to limbic regions, determined by localizing its mRNA and correlating it with binding studies using putative D3 selective ligands and antibodies (Ariano and Sibley 1994; Larson and Ariano 1995). A high level of D3 receptor expression is seen in the ventromedial shell of the nucleus accumbens, the olfactory tubercle and the Islands of Calleja (Diaz et al. 1995). Lower levels of expression are observed in the ventral tegmental area, the molecular layer of the vestibulocerebellum, the cerebral cortex and the hippocampus (Bouthenet et al. 1991). In human brain, D3 receptor expression is observed in the nucleus accumbens and Islands of Calleja (Landwehrmeyer et al. 1993). Expression has also been reported in ventral putamen, ventral caudate and globus pallidus (Meador-Woodruff et al. 1996; Seeman et al. 2006). Receptor expression studies using in situ hybridization methods suggest that in addition to a highly localized pattern of expression, the D3 receptor is often co-expressed with other dopamine receptor subtypes (Le Moine and Bloch 1996).

The co-expression pattern of D3 receptor and other dopamine receptor subtypes and the relative expression level of the individual dopamine receptor subtypes and key signaling proteins at the single cell level in various brain regions are largely unknown. It is also not known if the D3 receptor is expressed in catecholaminergic, GABAergic or glutamatergic neurons, in various brain regions. Expression of genes also differ between sex and changes with age; sex- and age-dependent changes in co-expression patterns of D3 receptors and other dopamine receptor subtypes and signaling molecules have not been well studied. While studies have suggested that the D3 receptor is co-expressed with other dopamine receptors, the regional distribution of such co-expression has not been determined at the single cell level in various brain regions across age and sex. This, for example, is important for studies that examine the heteromultimerization of D3 receptor with other dopamine receptor subtypes in vivo. Studies in heterologous cell lines have demonstrated that the D3 receptor couples robustly to ACV and GIRK channels; however, coupling of D3 receptors to these signaling effectors and how other co-expressed dopamine receptor subtypes might modulate the coupling in vivo have not been unequivocally demonstrated. Determining the in vivo co-expression pattern of D3 receptors with other dopamine receptor subtypes, ACV and GIRKs would facilitate the characterization of D3 receptor signaling function in vivo.

To begin addressing these questions, we used a novel transgenic mice model developed by the Gene Expression Nervous System Atlas (GENSAT) project (Gong et al. 2003). These transgenic mice express the enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP) in cells natively expressing wild-type D3 dopamine receptors. These mice do not express a D3 receptor—EGFP fusion protein; rather, these mice have a transgene in which the EGFP reporter gene is under the control of the D3 receptor gene promoter. Thus, the EGFP fluorescent protein from the transgene construct is expressed in cells that natively express the D3 receptor mRNA, which facilitates the identification and characterization of its signaling function in vivo. The initial characterization of the drd3-EGFP transgenic mice using immunocytochemistry and in situ hybridization methods by the GENSAT project team suggests a good correlation between expression of native D3 receptors and EGFP expression in various brain regions (unpublished observations). However, the expression of D3 receptor signaling molecules and other dopamine receptor subtypes have not been determined in individual fluorescent cells isolated from these drd3-EGFP transgenic mice.

Here, we used single cell reverse transcriptase PCR (RT-PCR) to determine mRNA expression of D1, D2, D3, D4 and D5 dopamine receptors, tyrosine hydroxylase, glutamate decarboxylase (GAD), vesicular glutamate transporter (VGLUT1 and 2), glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP), neuron-specific enolase (NSE), AC V isoform and three different isoforms of GIRK channels in single fluorescent cells isolated from the drd3-EGFP mice. Acutely dissociated cells were obtained from the nucleus accumbens, Islands of Calleja, olfactory tubercle, retrosplenial cortex, dorsal subiculum, mammillary body, amygdala and septum. These brain regions were chosen as they had the highest density of fluorescent cells, making them amenable to single cell isolation and characterization. Analysis was done on single cells isolated from male and female drd3-EGFP mice that were either postnatal day 35 (P35; periadolescent) or postnatal day 70 (P70; adult). For this study, we performed ~11,000 single cell RT-PCRs, screening for the expression of 15 different genes in each cell of approximately 750 individual fluorescent cells isolated from the drd3-EGFP mice. We also used immunohistochemistry, where feasible, to confirm the expression of D3 receptor protein in the fluorescent cells. Comparison between periadolescent (P35) and adults (P70) were made as they represent very distinct developmental stages, which relate to sexual maturity and changes in behavior (Koshibu et al. 2004; O’Donnell 2010). In addition, the periadolescent stage is important for modeling addictive disorders in juveniles and adolescents (Cao et al. 2007; Zombeck et al. 2010). Similarly periadolescent animals are used in maternal infection models to evaluate behaviors relevant to schizophrenia and related disorders (Vuillermot et al. 2010). As the purpose of this study was to validate the drd3-EGFP mouse model for future studies, we also considered it important to compare the expression between males and females. Previous studies have shown distinct sex differences in dopaminergic system; however, the differences in dopamine receptor expression patterns have not been well characterized (Andersen and Teicher 2000; Teicher et al. 1995; Andersen et al. 1997).

The results of this study suggest that D3 receptor is expressed in neurons, with region-specific expression in glutamatergic and GABAergic neurons. The D3 receptor primarily co-expressed with D1 and D2 dopamine receptors with regional, sex and age-dependent differences in the co-expression pattern. The percentage of cells co-expressing D3 receptor and ACV or GIRK channels varied significantly by brain region, sex and age. The comprehensive single cell analysis of D3 receptor-expressing cells in mouse brain reported here will facilitate the characterization of D3 receptor function in physiology and pathophysiology. The expression studies also validate the drd3-EGFP mouse model for use in future biochemical and behavioral studies.

Materials and methods

drd3-EGFP animals

The drd3-EGFP hemizygous mice were kindly provided by Drs. Mary Beth Hatten and Nathaniel Heintz (GENSAT program, Rockefeller University). The original female hemizygous mice had a mixed Swiss Webster/FVB genetic background (personal communication). A local breeding colony was established at UMDNJ-New Jersey Medical School by breeding the hemizygous female mice with male FVB/N mice. The FVB/N mouse strain was originally derived from an outbred Swiss Webster mice colony at NIH and is known to have excellent reproductive characteristics and large litter sizes (Taketo et al. 1991). The progeny of the drd3-EGFP hemizygous female mice and male FVB/N mice were genotyped and those with the highest numbers of the bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC) drd3-EGFP transgene copies were inbred six to seven generations to establish a colony of mice that had a stable, high copy number of the BAC drd3-EGFP transgene. Given the breeding history, the drd3-EGFP mice used in this study should primarily have an FVB genetic background. The mice used in this study were obtained from locally bred animals kept in the transgenic barrier facility on a 12:12-h, light–dark schedule (lights on at 0800 hours) and provided ad libitum food and water. The animal protocols were approved by the IACUC committee at UMDNJ-New Jersey Medical School. The construction of the drd3-EGFP transgene present in these mice has been described previously (Gong et al. 2003). Briefly, the EGFP reporter gene was placed just 5′ of the ATG translation initiation codon of the drd3 gene and a polyA site was placed downstream of the EGFP open reading frame. Thus, the mRNA encoding the D3 receptor gene in the bacterial artificial chromosome construct was replaced by a fusion mRNA composed of the 5′ untranslated region of the drd3 gene fused to the EGFP coding sequence and an exogenous polyadenylation signal. Consequently, the expression of the EGFP reporter in the drd3-EGFP mice will not reflect posttranscriptional events regulating the abundance of D3 receptor mRNA or protein produced from the endogenous gene; instead, the EGFP reporter expression in the mice directly reflects the relative levels of D3 receptor gene transcription.

Preparation of acutely dissociated cells and single cell isolation

For the experiments, the mice were anesthetized with isofluorane (100 ml/kg, Piramal Healthcare) and decapitated. The brains were quickly removed and immersed in an ice-cold and oxygenated (95% O2, 5% CO2) high-sucrose solution containing the following (in mM): 200 sucrose, 28 NaHCO3, 2.5 KCl, 7 MgCl2, 1.25 NaH2PO4, 0.5 CaCl2, 1 L-ascorbate, 3 sodium pyruvate, and 8 D-glucose (pH 7.4). Coronal slices (300–400 μm thick) were cut on a Vibratome (series 1500, Bannockburn, IL). The various brain regions containing green fluorescent neurons were carefully dissected from the slices under a stereo dissection microscope (Olympus SZX16) with fluorescent light. Papain (Worthington Biochemicals) was used to digest the brain tissue at 30°C for 25 min. The acutely dissociated cells were visualized on an Olympus IX70 inverted fluorescence microscope, and a glass patch pipette (Warner instruments) filled with 12.5 ng/μl bovine serum albumin (Idaho technology) was used to pick and transfer single green fluorescent cells into individual RNAse- and DNAse-free microfuge tubes containing 1 μl (20 U) SUPERase·In™ RNAse inhibitor (Ambion). The cells were picked and transferred within 30 min of dissociation and rapidly frozen on dry ice. All single cell samples were stored at −80°C before RT reaction.

Brain slice imaging

Coronal and sagittal sections (150–200 μm thick) were cut and images captured using an Olympus IX70 inverted fluorescence microscope, the Retiga EX CCD camera and the IP lab image acquisition system (Spectra Services Inc., Ontario, NY). Several overlapping images of each section were obtained using 4×, 20× or 40× objectives and integrated using Image J (Abramoff et al. 2004) or Photoshop (Adobe Systems Inc. San Jose, CA).

Reverse transcriptase PCR

To each single cell sample,18 μl DNAse- and RNAse-free water, 1 μl random primers (150 ng/ul stock) and 1.5 μl dNTP (10 mM stock) were added and incubated at 65°C for 5 min and quick chilled on ice. After the addition of first-strand Superscript III reverse transcriptase buffer (Invitrogen), the denatured samples were annealed at room temperature for 10 min. To initiate cDNA synthesis, 10 mM dithiothreitol (DTT), 10U SUPERase·In™ (Ambion) and 100 U SuperScript™ III reverse transcriptase were added to a final volume of 30 μl and the reaction incubated at 45°C for 2 h. The reaction was stopped by heat inactivation at 70°C for 15 min and the samples were stored in −20°C. Real-time PCR was performed using the Light Cycler® (Roche) and using species- and gene-specific TaqMan® probes (Table 1) and TaqMan® PCR reagents (Applied Biosystems). For each PCR reaction, 2 μl of the 30 μl reverse transcriptase reaction was used. Two negative and one positive control were incorporated in each RT-PCR run. Negative control included a PCR reaction in which the template was substituted for water. For a second negative control, PCR was run with products from an RT reaction in which the reverse transcriptase enzyme was omitted. Mouse brain cDNA was used as a positive control in all PCR runs. The PCR results were analyzed as described previously using crossing point analysis (Pasuit et al. 2004). The ratio of D3 to other dopamine receptor subtypes (Dx) mRNA expression was calculated as 2^(DxCt − D3Ct). The data were analyzed using z-test to compare proportions or Mann–Whitney rank sum test as described in the figure legends. The cells were obtained from at least three animals for each sex and age group. P <0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Table 1.

List of TaqMan® probes used

| # | Name of probe | Species | Location on gene | Short name |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Mm01353211_m1 | M | Ex1–Ex2 (96) | mDrd1a-211 |

| 2 | Mm00438545_m1 | M | Ex7–Ex8 (1234) | mDrd2-545 |

| 3 | Mm00432887_m1 | M | Ex1–Ex2 (272) | mDrd3-887 |

| 4 | Mm00432893_m1 | M | Ex1–Ex2 (304) | mDrd4-893 |

| 5 | Mm00658653_s1 | M | Ex1–Ex1 (2667) | mDrd5-653 |

| 6 | Mm00469062_m1 | M | Ex7–Ex8 (749) | mNSE-062 |

| 7 | Mm01185008_m1 | M | Ex10–Ex11 (1268) | mEno2-008 |

| 8 | Mm01253034_m1 | M | Ex8–Ex9 (1325) | mGFAP-034 |

| 9 | Mm99999915_g1 | M | Ex2–EX3 (74) | mGAPDH-915 |

| 10 | Mm00434618_m1 | M | Ex2–EX3 (970) | mGIRK1-618 |

| 11 | Mm00440070_m1 | M | Ex1–Ex2 (508) | mGIRK2-070 |

| 12 | Mm00434622_m1 | M | Ex2–EX3 (230) | mGIRK3-622 |

| 13 | Mm00812886_m1 | M | Ex7–Ex8 (1026) | mVGLUT1-886 |

| 14 | Mm00499876_m1 | M | Ex8–Ex9 (1840) | mVGLUT2-876 |

| 15 | Mm00484623_m1 | M | Ex4–Ex5 (859) | mGAD65-623 |

| 16 | Mm00447557_m1 | M | Ex12–EX13 (1343) | mTH-557 |

| 17 | Mm00674122_m1 | M | Ex20–EX21 (4124) | mACV-122 |

Immunohistochemistry

Mice were anesthetized with 60 mg/kg (i.p.) Nembutal and transcardially perfused with phosphate-buffered saline and 1 U/ml heparin followed by 4% paraformaldehyde. The brains were dissected and stored in paraformaldehyde for 24 h before being transferred and incubated in 30% sucrose for 72 h. The brains were embedded in Tissue-Tek® OCT compound and frozen at −80°C. Coronal 20-μM sections were obtained from the frozen brains using a cryostat. The sections were permeabilized with 0.05% TWEEN 20 and 0.3% Triton X-100 for 10 min. After washing, the sections were blocked with 6.4% Superior™ blocking buffer dry blend in TBS (GBiosciences) in 4°C for 30 min. The sections were incubated in 1:100 dilution of D3 receptor polyclonal antibody (ab42114; Abcam) for 15 h at 4°C. After washing, the sections were incubated in 1:1,000 dilution of goat antirabbit AlexaFluor® 594 secondary antibody (Invitrogen) for 1 h at 25°C. The sections were mounted using Prolong® Gold antifade reagent with DAPI (Invitrogen) and visualized as above with appropriate filters. The optimal concentration of secondary antibody and optimal exposure time were determined by using a negative control in which we omitted the primary antibody and included only the secondary antibody.

Results

Regional localization of fluorescent cells in the drd3-EGFP mice

To determine the regional localization of EGFP-expressing fluorescent cells in drd3-EGFP transgenic mice, we obtained sagittal and coronal brain sections from P35 and P70 male and female mice. Figures 1 and 2 show representative live sagittal and coronal brain sections that are 150-μM thick; the highest density of fluorescent cells are found in the nucleus accumbens, Islands of Calleja, olfactory tubercle, dorsal subiculum, retrosplenial granular cortex and mammillary bodies. The sagittal section in Fig. 1 shows the fluorescent mammillothalamic tracts between the mammillary body and thalamus. Figure 2 shows 150-μM thick coronal sections that include the brain regions containing a high density of fluorescent cells. Figure 2 also shows thinner 20-μM sections of these brain regions indicating the presence of fluorescent cells and fluorescently labeled axons. In addition to the above-mentioned areas, significant numbers of fluorescent cells were found in the septum, amygdala, thalamus, dentate gyrus, CA1 hippocampus, subventricular zone, cingulate, entorhinal and piriform cortex (data not shown). Compared to these regions, the density and numbers of fluorescent cells in dopaminergic areas such as the substantia nigra and ventral tegmental areas were relatively low. We also did not observe any significant qualitative differences in regional localization of fluorescent cells between male and female or P35 and P70 animals. The results from this analysis lead us to focus on single cell characterization of fluorescent cells present in high-density areas such as nucleus accumbens, Islands of Calleja, olfactory tubercle, subiculum, retrosplenial granular cortex, mammillary bodies and amygdala. We also did limited single cell characterization of fluorescent cells from the septum.

Fig. 1.

Representative image of a sagittal section of brain obtained from an adult drd3-EGFP mouse. The fluorescence intensity indicates the density of fluorescent cells and EGFP-filled fibers in the various brain regions. The freshly cut live 150-μm sagittal section was placed on glass coverslips and visualized using an inverted fluorescence microscope and appropriate EGFP filters. Scale bar (yellow rectangles) in the panel is 300 μm

Fig. 2.

Representative images of coronal brain sections obtained from an adult drd3-EGFP mouse. The freshly cut live 150-μm coronal (a, c and e) sections were placed on glass coverslips and visualized using an inverted fluorescence microscope and appropriate EGFP filters. Scale bars (yellow rectangles) in the panels are 60 μm (a), 125 μm (c) and 250 μm (e). Brain regions with high density of EGFP-expressing cells include IC Islands of Calleja, OT olfactory tubercle, NA nucleus accumbens, RSG retrosplenial granular cortex, and MB mammillary body. To visualize cell bodies and fibers in these brain regions at a higher magnification, we used 20-μm coronal cryosections (b, d and f). Scale bars in these panels are 30 μm

Single cell RT-PCR workflow and optimization

The work plan adopted for the single cell RT-PCR analysis of fluorescent cells from the eight brain regions of male and female, P35 and P70 mice is shown in Fig. 3. The collected cells were first analyzed for the expression of the housekeeping gene, glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH), and only GAPDH-positive cells were analyzed further for the presence of D3 receptor mRNA. GAPDH-and D3 receptor-positive fluorescent cells were used for subsequent analysis. Neuronal and glial cell identities were determined using neuron-specific enolase (NSE) and glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) probes, respectively. Cells that were positive for NSE were not screened for GFAP. To determine if the cells were GABAergic, glutamatergic or catecholaminergic, we used probes that detected glutamic acid decarboxylase (GAD), vesicular glutamate transporters (VGLUT1 or 2) and tyrosine hydroxylase (TH), respectively. Cells that were positive for GAD were not screened for VGLUT and only those that were negative for both GAD and VGLUT1 were screened for VGLUT2. Finally, the cells were screened for all the other dopamine receptor subtypes and signaling effectors adenylate cyclase V (ACV) and three different isoforms of G protein-coupled inward rectifier potassium (GIRK1, 2 and 3) channels. As functional GIRK channels are composed of GIRK1 + 2, GIRK1 + 3, GIRK2 or GIRK3, for the analysis a cell was considered GIRK positive if it expressed any of the above combinations.

Fig. 3.

A flowchart depicting the experimental plan for the single cell RT-PCR analysis followed in this study

We optimized the condition for RT-PCR using the real-time Roche Light Cycler™ and TaqMan® probes and reagents. Figure 4a shows PCR amplification of a serially diluted D3 receptor cDNA. In Fig. 4b, the Ct values obtained from the PCR were plotted versus the concentration of the serially diluted D3 receptor cDNA to obtain a standard curve. To determine the sensitivity, linearity and reproducibility of the RT-PCR, we first isolated total mouse brain RNA and generated total mouse brain cDNA as described in “Methods”. Next, we serially diluted the total mouse brain cDNA sample 10,000-fold and performed PCR with TaqMan® probes for detecting D1, D5, D2, D3, and D4 dopamine receptors. The results in Fig. 4c show that the amplification was linear and reproducible for all dopamine receptor subtype probes. Moreover, by comparing the Ct values for D3 receptor amplification in Fig. 4c to the standard curve in Fig. 4b, we calculated that the RT-PCR conditions used can detect a single molecule of D3 receptor mRNA in a heterogeneous total mouse brain cDNA sample. Figure 4d is a representative example of a single fluorescent cell from the drd3-EGFP mouse brain, which expresses D3 receptor mRNA but not D1 or D2 receptor mRNA.

Fig. 4.

Sensitivity, linearity and reproducibility of the RT-PCR used in this study. a Raw traces from a representative real-time PCR detected using D3 receptor-specific TaqMan® probe shows the sensitivity of the amplification method to identify serially diluted D3 receptor cDNA. b Comparing the Ct values (cycle numbers) and D3 receptor cDNA concentration from the PCR in a shows a linear correlation across 107-fold dilution range. c Cumulative data showing a linear correlation between the Ct values (cycle numbers) and concentration of serially diluted total mouse brain cDNA that were amplified and detected using TaqMan® probes specific for D1 (diamond), D5 (square), D2 (upright triangle), D3 (circle) and D4 (inverted triangle) dopamine receptors. The data points represent mean (±SEM) of four independent RT-PCR reactions that were fitted with linear regression. d Representative raw traces from a single cell RT-PCR showing amplification of cDNA from a single fluorescent cell that expresses D3 but not D1 or D2 dopamine receptor mRNA. The dotted lines represent the amplification of the positive controls (total mouse brain cDNA). The solid lines represent the amplification of the cDNA from the single cell. The three TaqMan® probes used to detect D1, D2 and D3 dopamine receptors are indicated

General characteristics of fluorescent cells isolated from various brain regions of the drd3-EGFP mice

For this study, we performed single cell RT-PCR on approximately 750 fluorescent cells from eight brain regions, screening for the expression of 15 different genes in each cell. Table 2 summarizes the general expression characteristics of the fluorescent cells from the eight brain regions of the drd3-EGFP transgenic mice. Greater than 90% of GAPDH-positive fluorescent cells expressed D3 receptor mRNA in all brain regions studied. This suggests that in these drd3-EGFP transgenic mice, the reporter transgene faithfully reports the expression of the endogenous D3 receptor mRNA with a very low rate of ectopic expression. The results in Table 2 also show that D3 receptor expression is limited to neurons; none of the fluorescent cells examined co-expressed the astrocyte cell marker GFAP. Interestingly, in Islands of Calleja, and to a lesser extent in olfactory tubercle, the percentage of cells co-expressing NSE was significantly low. These NSE-negative cells were also GFAP-negative; however, further analysis using a different NSE probe and another mature neuronal marker, microtubule-associated protein 2 (MAP2), probe revealed that the NSE-negative cells were also neuronal. The results suggest that some fluorescent cells in Islands of Calleja and olfactory tubercle express an alternatively spliced isoform of NSE that is not detected by the mNSE-062 TaqMan® probe which spans exon 7 and 8 of the NSE mRNA.

Table 2.

Expression characteristics of fluorescent cells isolated from various brain regions of the drd3-EGFP mice

| Brain region | No. of cells screenedd | D3 (%) | NSE (%) | GFAP | GAD | VGLUT | TH |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nucleus accumbens | 110 | 98 | 95 | (–) | 75% | 10% | (–) |

| Islands of Calleja | 104 | 95 | 69a | (–) | 60% | (–) | (–) |

| Olfactory tubercle | 98 | 91 | 83 | (–) | 80% | (–) | (–) |

| Retrosplenial cortex | 105 | 96 | 99 | (–) | (–) | 100% | (–) |

| Subiculum | 104 | 92 | 97 | (–) | (–) | 100% | (–) |

| Mammillary body | 92 | 95 | 95 | (–) | (–) | 98%b | (–) |

| Amygdala | 96 | 96 | 100 | (–) | 66%c | 34%c | (–) |

| Septum | 43 | 98 | 100 | (–) | 85% | 10% | (–) |

(–) No detectable expression of the gene

D3-positive cells expressed a splice variant of neuron-specific enolase, which was not detected by the probe used. Subsequent analysis with different probes confirmed the neuronal identity

D3-positive cells express the VGLUT2 but not the VGLUT1 isoform

Percentage of cells co-expressing D3 and GAD versus D3 and VGLUT varies depending on age. See Fig. 13

Numbers represent fluorescent cells isolated from male and female drd3-EGFP mice at P35 and P70

None of the fluorescent cells examined in the eight brain regions co-expressed tyrosine hydroxylase, the rate-limiting enzyme for catecholamine synthesis. This suggests that D3 receptors are not pre-synaptically expressed in catecholaminergic neurons in the eight brain regions studied (Table 2). Expression of D3 receptors in GABAergic and glutamatergic neurons is brain region dependent. In nucleus accumbens, Islands of Calleja, olfactory tubercle and septum, the D3 receptor is expressed primarily in GABAergic neurons. In contrast, the D3 receptor is primarily expressed in glutamatergic neurons in retrosplenial cortex, dorsal subiculum and mammillary body. Interestingly, the results show that in mammillary bodies, unlike other brain regions, the D3 receptor-expressing glutamatergic neurons express the VGLUT2 but not VGLUT1 isoform. We also observed that in amygdala, there is a significant change in the number of D3 receptor-expressing GABAergic cells to D3 receptor-expressing glutamatergic cells as the animals matures from periadolescence to adult hood.

Co-expression of D3 receptors with other dopamine receptor subtypes, ACV and GIRK channels in nucleus accumbens

In the nucleus accumbens, the D3 receptor was significantly co-expressed with D1 and D2 receptors, but not D4 or D5 dopamine receptors. Less than 2% of the cells examined co-expressed D3 and D4 or D3 and D5 receptors. Figure 5a shows the percentage of cells co-expressing D3 and D1 receptors in male and female drd3-EGFP mice that were either P35 or P70. A significantly greater percentage of male mice co-expressed D1 and D3 receptors in the nucleus accumbens compared to female mice, regardless of age. Interestingly, while there was no change in the percentage of cells co-expressing D3 and D1 receptors between P35 and P70, the relative expression level of D3 to D1 receptor mRNA in each cell decreased with age (Fig. 5b). In both sexes, the expression of D3 receptor mRNA was significantly greater than D1 receptor mRNA in each cell at P35; however, at P70 each cell expressed significantly more D1 receptor mRNA than D3 receptor mRNA.

Fig. 5.

Co-expression of D3 dopamine receptor with other dopamine receptor subtypes, ACV and GIRK channels in the nucleus accumbens. Percentage of cells co-expressing D3 and D1 receptors (a), D2 receptors (b), adenylate cyclase V (ACV) isoform (e) and GIRK channels (f) in male or female drd3-EGFP mice at postnatal day 35 (P35) or 70 (P70). In a, c, e and f, groups that were compared and found to exhibit statistically significant differences (P <0.05) using a z-test are identified with common symbols (either *, #, +, or $). Number of cells screened in each group was 30 (P35 male), 26 (P70 male), 29 (P35 female) and 23 (P70 female). In cells co-expressing D3 and D1 (b) or D3 and D2 (d) dopamine receptors, the relative mRNA expression was determined using real-time RT-PCR and expressed as a ratio of D3 to D1 or D2 receptor mRNA. * P <0.05, Mann–Whitney rank sum test, significantly different from equal expression (ratio = 1, represented by dashed line). # P <0.05, Mann–Whitney rank sum test, significant difference exists between the P35 and P70 age groups, in both males and females. Error bars are ±SEM

Unlike D1 receptors, the percentage of cells co-expressing D3 and D2 receptors varies with both sex and age. Figure 5c shows that the percentage of cells co-expressing D3 and D2 receptors increases in P70 males and decreases in P70 females. P35 females have a significantly greater percentage of D3 and D2 receptor co-expressing cells than P35 males. In contrast, P70 females have a significantly lower percentage of D3 and D2 receptor co-expressing cells than P70 males. Examining the relative expression level of D3 and D2 receptors, male animals (P35 and P70) express equal levels of D3 and D2 receptor mRNA in each cell (Fig. 5d); however, female P35 mice express significantly higher levels of D3 to D2 receptor mRNA per cell. This ratio decreases significantly in female P70 mice which express significantly higher levels of D2 receptor mRNA per cell. Interestingly, this increase in D2 to D3 receptor mRNA expression per cell coincides with a reduction in percentage of cells co-expressing D3 and D2 receptors (Fig. 5c).

The percentage of cells co-expressing D3 receptor and ACV is relatively high in the nucleus accumbens; in the nucleus accumbens of male animals, 100 and 92% of cells co-express ACV at P35 and P70, respectively. Similarly, 90% of cells in female animals at P35 co-express D3 receptor and ACV. Significant reduction in percentage of cells co-expressing D3 receptor and ACV is only observed in female P70 mice (Fig. 5e). A relatively small percentage (10–20%) of the D3 receptor-expressing cells in the nucleus accumbens co-expressed GIRK channels (defined as GIRK1 + 2, GIRK1 + 3, GIRK2, or GIRK3), with no significant changes across age and sex (Fig. 5f).

Co-expression of D3 receptors with other dopamine receptor subtypes, ACV and GIRK channels in the Islands of Calleja

In the Islands of Calleja, the D3 receptor was significantly co-expressed with D1 and to a lesser extent with D2 receptors. Less than 1% of the cells examined co-expressed D3 and D4 and no cells co-expressed D3 and D5 receptors. Figure 6a shows the percentage of cells co-expressing D3 and D1 receptors in male and female drd3-EGFP mice that were either P35 or P70. Approximately, 13–33% of the cells co-expressed D1 and D3 receptors when compared across age and sex with no significant differences. The relative expression level of D3 to D1 receptor mRNA in each cell was equal across all age and sex, except for P35 male which expressed significantly higher levels of D3 to D1 receptor mRNA (Fig. 6b).

Fig. 6.

Co-expression of D3 dopamine receptor with other dopamine receptor subtypes, ACV and GIRK channels in the Islands of Calleja. Percentage of cells co-expressing D3 and D1 receptors (a), D2 receptors (b), adenylate cyclase V (ACV) isoform (e) and GIRK channels (f) in male or female drd3-EGFP mice at postnatal day 35 (P35) or 70 (P70). In a, c, e and f, groups that were compared and found to exhibit statistically significant differences (P <0.05) using a z-test are identified with common symbols (*). Number of cells screened in each group was 24 (P35 male), 18 (P70 male), 27 (P35 female) and 30 (P70 female). In cells co-expressing D3 and D1 (b) or D3 and D2 (d) dopamine receptors, the relative mRNA expression was determined using real-time RT-PCR and expressed as a ratio of D3 to D1 or D2 receptor mRNA. *P <0.05, Mann–Whitney rank sum test, significantly different from equal expression (ratio = 1, represented by dashed line). Error bars are ±SEM

Unlike D1 receptors, the percentage of cells co-expressing D3 and D2 receptors vary with both sex and age. Figure 6c shows that the percentage of cells co-expressing D3 and D2 receptors decreases in P70 males and increases in P70 females. Cells from P35 females and P70 males did not co-express D3 and D2 receptors. Examining the relative expression level of D3 and D2 receptors in the two groups with co-expression, male P35 mice express equal levels of D3 and D2 receptor mRNA in each cell (Fig. 6d); however, female P70 mice express significantly higher levels of D3 to D2 receptor mRNA per cell.

The percentage of cells co-expressing D3 receptor and ACV in the Islands of Calleja is less compared to that in the nucleus accumbens (Fig. 6e). There are no significant age-specific changes in either sex in the percentage of cells co-expressing D3 receptors and ACV; however, there is a significant reduction in the percentage of cells co-expressing D3 receptor and ACV in P70 females, compared to P70 males. Compared to nucleus accumbens, in the Islands of Calleja, a higher percentage of cells (~17–37%) co-express D3 receptors and GIRK channels (defined as GIRK1 + 2, GIRK1 + 3, GIRK2, or GIRK3), with no significant changes across age and sex (Fig. 6f).

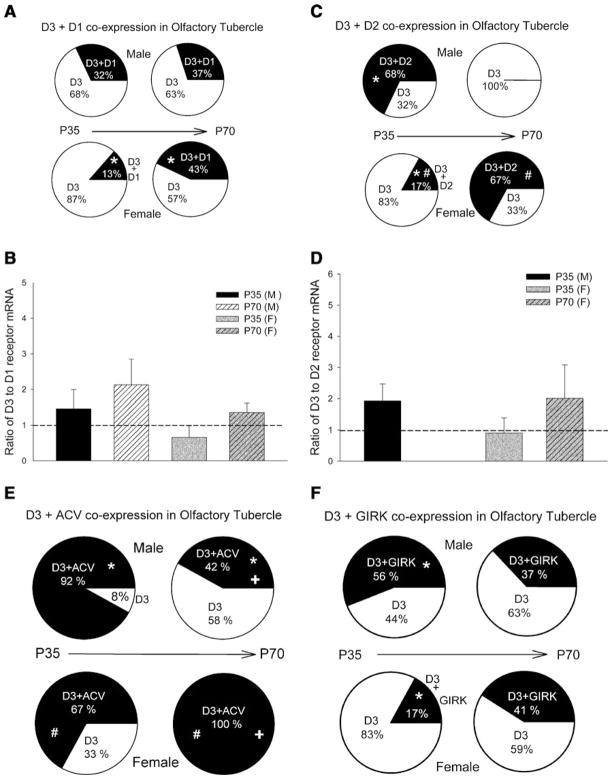

Co-expression of D3 receptors with other dopamine receptor subtypes, ACV and GIRK channels in the olfactory tubercle

In the olfactory tubercle, the D3 receptor was significantly co-expressed with D1 and D2 receptors. Less than 1% of the cells examined co-expressed D3 and D4 and no cells co-expressed D3 and D5 receptors. Figure 7a shows the percentage of cells co-expressing D3 and D1 receptors in male and female drd3-EGFP mice that were either P35 or P70. While no significant differences in the percentage of cells co-expressing D1 and D3 receptors were observed in P35 and P70 males, there was a significant increase in percentage of cells co-expressing D1 and D3 receptors in P70 female compared to P35 female. The relative expression level of D3 to D1 receptor mRNA in each cell was equal across all age and sex (Fig. 7b).

Fig. 7.

Co-expression of D3 dopamine receptor with other dopamine receptor subtypes, ACV and GIRK channels in the olfactory tubercle. Percentage of cells co-expressing D3 and D1 receptors (a), D2 receptors (b), adenylate cyclase V (ACV) isoform (e) and GIRK channels (f) in male or female drd3-EGFP mice at postnatal day 35 (P35) or 70 (P70). In a, c, e and f, groups that were compared and found to exhibit statistically significant differences (P <0.05) using a z-test are identified with common symbols (either *, +, or #). Number of cells screened in each group was 25 (P35 male), 19 (P70 male), 24 (P35 female) and 21 (P70 female). In cells co-expressing D3 and D1 (b) or D3 and D2 (d) dopamine receptors, the relative mRNA expression was determined using real-time RT-PCR and expressed as a ratio of D3 to D1 or D2 receptor mRNA. Ratio = 1 is represented by dashed line. Error bars are ±SEM

Unlike D1 receptors, the percentage of cells co-expressing D3 and D2 receptors in the olfactory tubercle varies with both sex and age. Figure 7c shows that there are no cells co-expressing D3 and D2 receptors in P70 males, which represents a significant decrease from P35 males. In contrast, the percentage of cells co-expressing D3 and D2 receptors increases significantly in P70 females, compared to P35 females. This pattern is similar to that observed in the Islands of Calleja (Fig. 6c). In the groups where there was co-expression of D3 and D2 receptors, the relative expression level of D3 to D2 receptor mRNA in each cell was equal across all age and sex (Fig. 7d).

The percentage of cells co-expressing D3 receptor and ACV in the olfactory tubercle is more compared to the Islands of Calleja and is similar to the nucleus accumbens (Fig. 7e). There are significant age-specific changes in both sexes in the percentage of cells co-expressing D3 receptors and ACV. There is a significant reduction in the percentage of cells co-expressing D3 receptor in P70 males compared to P35 males. In contrast, there is a significant increase in the percentage of cells co-expressing D3 receptor and ACV in P70 females compared to P35 females. With the exception of P35 females, in all other groups a high percentage of cells (~37–56%) co-express D3 receptors and GIRK channels (defined as GIRK1 + 2, GIRK1 + 3, GIRK2, or GIRK3). P35 females have a significantly reduced percentage of cells co-expressing D3 receptors and GIRKs when compared with P35 male (Fig. 7f).

Co-expression of D3 receptors with other dopamine receptor subtypes, ACV and GIRK channels in the retrosplenial cortex

Fluorescent cells are found in the molecular cell layers of the cortex of the drd3-EGFP mice with a localization pattern that is very different between the cingulate and retrosplenial cortex. Figure 8 shows that fluorescent cells are primarily found in layer VI in the cingulate cortex (Fig. 8a), but are found in multiple layers in the retrosplenial cortex (Fig. 8b). We performed single cell characterization of fluorescent cells isolated from the retrosplenial cortex region.

Fig. 8.

D3 receptor-expressing fluorescent cells are found in different molecular layers in cingulate and retrosplenial cortex. Representative images of 100-μm coronal sections obtained from an adult drd3-EGFP mouse shows D3 receptor-expressing cells primarily in molecular layer VI (small thin yellow arrow) in the cingulate cortex (a) and multiple layers (thick yellow arrow) in the retrosplenial cortex (b). Scale bars (yellow rectangles) in the panels are 120 μm

In the retrosplenial cortex, the D3 receptor was not co-expressed with D2 receptors in any group and only significantly co-expressed with D1 receptors in P70 females (Fig. 9a). Even in this group, the relative expression level of D3 to D1 receptor mRNA in each cell was more than 500-fold (Fig. 9b). Less than 2% of the cells examined co-expressed D3 with D4 and D5 receptors.

Fig. 9.

Co-expression of D3 dopamine receptor with other dopamine receptor subtypes, ACV and GIRK channels in the retrosplenial cortex. Percentage of cells co-expressing D3 and D1 receptors (a), adenylate cyclase V (ACV) isoform (c) and GIRK channels (d) in male or female drd3-EGFP mice at postnatal day 35 (P35) or 70 (P70). In panels a, c, and d, groups that were compared and found to exhibit statistically significant differences (P <0.05) using a z-test are identified with common symbols (either *, or #). Number of cells screened in each group was 15 (P35 male), 35 (P70 male), 25 (P35 female) and 25 (P70 female). In cells from P70 females which co-express D3 and D1 dopamine receptors, the relative mRNA expression was determined using real-time RT-PCR and expressed as a ratio of D3 to D1 receptor mRNA (b). *P <0.05, Mann–Whitney rank sum test, significantly different from equal expression (ratio = 1, represented by dashed line). Error bars are ±SEM

The percentage of cells co-expressing D3 receptor and ACV in the retrosplenial cortex is less (Fig. 9c) compared to the nucleus accumbens, Islands of Calleja and olfactory tubercle. The exception is P70 females where D3 receptor and ACV were co-expressed in all cells examined. There is also a significant age-specific increase in the number of cells co-expressing D3 receptors and ACV in females. P35 and P70 males have less percentage of cells co-expressing D3 receptor and ACV compared to females. Compared to the nucleus accumbens, Islands of Calleja and olfactory tubercle, a higher percentage of cells (~50%) co-express D3 receptors and GIRK channels (defined as GIRK1 + 2, GIRK1 + 3, GIRK2, or GIRK3), with no significant changes across age and sex (Fig. 9d).

Co-expression of D3 receptors with other dopamine receptor subtypes, ACV and GIRK channels in the dorsal subiculum

As in the retrosplenial cortex, in the dorsal subiculum the D3 receptor was not co-expressed with D2 receptors in any group. In contrast to the retrosplenial cortex, D3 was only significantly co-expressed with D1 receptors in P70 males (Fig. 10a). Also, unlike the retrosplenial cortex, the relative expression level of D3 to D1 receptor mRNA in each cell in the dorsal subiculum of P70 males was significantly less than one, suggesting a higher expression of D1 receptor mRNA compared to D3 receptor mRNA (Fig. 10b). Less than 2% of the cells examined co-expressed D3 with D4 and D5 receptors.

Fig. 10.

Co-expression of D3 dopamine receptor with other dopamine receptor subtypes, ACV and GIRK channels in the dorsal subiculum. Percentage of cells co-expressing D3 and D1 receptors (a), adenylate cyclase V (ACV) isoform (c) and GIRK channels (d) in male or female drd3-EGFP mice at postnatal day 35 (P35) or 70 (P70). In a, c, and d, groups that were compared and found to exhibit statistically significant differences (P <0.05) using a z-test are identified with common symbols (*). Number of cells screened in each group was 20 (P35 male), 20 (P70 male), 37 (P35 female) and 19 (P70 female). In cells from P70 males which co-express D3 and D1 dopamine receptors, the relative mRNA expression was determined using real-time RT-PCR and expressed as a ratio of D3 to D1 receptor mRNA (b). *P <0.05, Mann–Whitney rank sum test, significantly different from equal expression (ratio = 1, represented by dashed line). Error bars are ±SEM

The percentage of cells co-expressing D3 receptor and ACV in the subiculum was similar to retrosplenial cortex (Fig. 10c). Unlike the retrosplenial cortex, in the dorsal subiculum, males co-expressed D3 receptor and ACV in a higher percentage of cells with a significant increase in percentage of cells in P70 males compared to P35 males. Also, similar to retrosplenial cortex, a relatively high percentage of cells (~40–75%) co-express D3 receptors and GIRK channels (defined as GIRK1 + 2, GIRK1 + 3, GIRK2, or GIRK3), with no significant changes across age and sex (Fig. 10d).

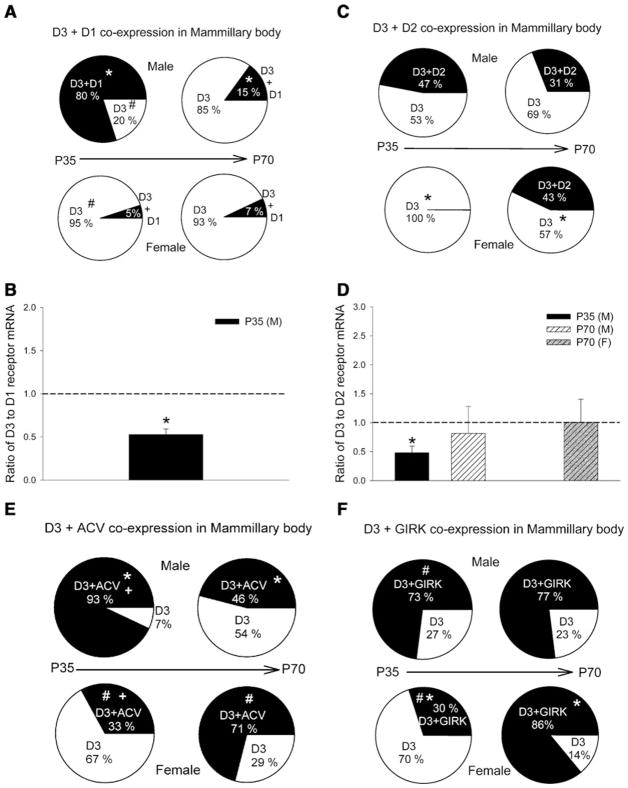

Co-expression of D3 receptors with other dopamine receptor subtypes, ACV and GIRK channels in the mammillary body

In the mammillary body, the D3 receptor was significantly co-expressed with D1 and D2 receptors. Less than 1% of the cells examined co-expressed D3 with D4 and D5 receptors. Figure 11a shows the percentage of cells co-expressing D3 and D1 receptors in male and female drd3-EGFP mice that were either P35 or P70. Significant percentage of D1 and D3 receptor co-expressing cells are found only in the P35 male group with a significant decrease in percentage of co-expressing cells with age in the P70 male group. The relative expression level of D3 to D1 receptor mRNA in each cell of the P35 male group was significantly less than 1, suggesting higher D1 receptor mRNA expression compared to D3 receptor mRNA (Fig. 11b). The percentage of cells co-expressing D3 and D1 receptors in the other three groups was too small and showed larger variation in relative levels of D3 and D1 receptor mRNA to be meaningful.

Fig. 11.

Co-expression of D3 dopamine receptor with other dopa-mine receptor subtypes, ACV and GIRK channels in the mammillary body. Percentage of cells co-expressing D3 and D1 receptors (a), D2 receptors (b), adenylate cyclase V (ACV) isoform (e) and GIRK channels (f) in male or female drd3-EGFP mice at postnatal day 35 (P35) or 70 (P70). In panels a, c, e and f, groups that were compared and found to exhibit statistically significant differences (P <0.05) using a z-test are identified with common symbols (either *, +, or #). Number of cells screened in each group was 15 (P35 male), 15 (P70 male), 40 (P35 female) and 17 (P70 female). In cells co-expressing D3 and D1 (b) or D3 and D2 (d) dopamine receptors, the relative mRNA expression was determined using real-time RT-PCR and expressed as a ratio of D3 to D1 or D2 receptor mRNA. *P <0.05, Mann–Whitney rank sum test, significantly different from equal expression (ratio = 1, represented by dashed line). Error bars are ±SEM

With the exception of the P35 female group, which did not show any D3 and D2 receptor co-expression, all other groups showed significant co-expression (~31–47%) of D3 and D2 receptors (Fig. 11c). There was a significant increase in percentage of cells expressing D3 and D2 receptors from P35 to P70 in females. In the groups where there was co-expression of D3 and D2 receptors, the relative expression level of D3 to D2 receptor mRNA in each cell was equal in P70 males and females (Fig. 11d). In P35 males which showed 47% of cells co-expressing D3 and D2 receptor mRNA, the relative expression level of D3 to D2 receptor mRNA in each cell was significantly less than one, suggesting that these mammillary body cells express a higher level of D2 receptor mRNA than D3 receptor mRNA.

The percentage of cells co-expressing D3 receptor and ACV in the mammillary body is similar to olfactory tubercle (Fig. 11e). There are significant age-specific changes in both sexes in the percentage of cells co-expressing D3 receptors and ACV. There is a significant reduction in the percentage of cells co-expressing D3 receptor in P70 males compared to P35 males. In contrast, there is a significant increase in percentage of cells co-expressing D3 receptor and ACV in P70 females compared to P35 females. With the exception of P35 females, in all other groups a high percentage of cells (~73–86%) co-express D3 receptors and GIRK channels (defined as GIRK1 + 2, GIRK1 + 3, GIRK2, or GIRK3). P35 females have a significantly reduced percentage of cells co-expressing D3 receptors and GIRKs when compared with P35 male and P70 female (Fig. 11f).

Co-expression of D3 receptors with other dopamine receptor subtypes, ACV and GIRK channels in the amygdala and septum

In the amygdala, the D3 receptor was significantly co-expressed with D1 and D2 receptors. Interestingly, unlike other brain regions examined, in the amygdala of P35 female mice, 3 and 12% of D3 receptor-expressing fluorescent cells co-expressed D4 and D5 dopamine receptors, respectively. In P70 female mice, none of the cells co-expressed D3 and D4 receptors, but the percentage of cells co-expressing D3 and D5 receptors increased to 22%. In P35 males, 27% of amygdala cells co-expressed D3 and D5 receptors, while none of the cells from the amygdala of P70 males co-expressed D3 and D5 receptor. No D3 and D4 receptor co-expression was observed in the male animals at P35 or P70.

Figure 12a shows the percentage of amygdala cells co-expressing D3 and D1 receptors in both sexes and at P35 and P70. There is a significant increase in percentage of D1 and D3 receptor co-expressing cells in the P70 female group when compared with P35 female. In contrast, there is a significant decrease in percentage of D1 and D3 receptor co-expressing cells in the P70 male group when compared with P35 male. At P70, females also have a higher percentage of cells co-expressing D3 and D1 receptors than males. The relative expression level of D3 to D1 receptor mRNA in each cell of the male groups was equal; however, in the two female age groups, the expression of D3 receptor mRNA in each cell was significantly greater than D1 receptor mRNA (Fig. 12b). Figure 12c shows the percentage of amygdala cells co-expressing D3 and D2 receptors. As observed with the D3 and D1 receptor co-expression in Fig. 12a, there is a significant increase in percentage of D2 and D3 receptor co-expressing cells in the P70 female group, while there is no significant difference in the males at P35 and P70. In general, females also have a higher percentage of D3 and D2 receptor co-expressing cells compared to males. However, unlike Fig. 12a results, the relative expression level of D3 to D2 receptor mRNA in each cell was equal in all groups examined except for the male P35 group where the expression of D3 receptors was significantly less than D2 receptors in each cell (Fig. 12d). The percentage of cells co-expressing D3 receptor and ACV in the amygdala is relatively high in all groups with no significant age-specific changes in both sexes (Fig. 12e). The amygdala also has relatively high percentage of cells co-expressing D3 receptor and GIRK channels (~44–90%). P35 males and P70 females have a significantly reduced percentage of cells co-expressing D3 receptors and GIRKs when compared with P35 females and P70 males (Fig. 12f).

Fig. 12.

Co-expression of D3 dopamine receptor with other dopamine receptor subtypes, ACV and GIRK channels in the amygdala. Percentage of cells co-expressing D3 and D1 receptors (a), D2 receptors (b), adenylate cyclase V (ACV) isoform (e) and GIRK channels (f) in male or female drd3-EGFP mice at postnatal day 35 (P35) or 70 (P70). In a, c, e and f, groups that were compared and found to exhibit statistically significant differences (P <0.05) using a z-test are identified with common symbols (either *, ψ, or #). Number of cells screened in each group was 30 (P35 male), 19 (P70 male), 32 (P35 female) and 9 (P70 female). In cells co-expressing D3 and D1 (b) or D3 and D2 (d) dopamine receptors, the relative mRNA expression was determined using real-time RT-PCR and expressed as a ratio of D3 to D1 or D2 receptor mRNA. *P <0.05, Mann–Whitney rank sum test, significantly different from equal expression (ratio = 1, represented by dashed line). Error bars are ±SEM

The results in Table 2 show that in the amygdala the D3 receptor is expressed in both GABAergic and glutamatergic cells. Surprisingly, the percentage of GAB-Aergic cells co-expressing D3 receptors significantly decreases in both sexes as the animal ages from P35 to P70 (Fig. 13). This decrease is complemented by a concomitant increase in the percentage of glutamatergic cells co-expressing D3 receptors from P35 to P70 in both sexes.

Fig. 13.

Co-expression of D3 dopamine receptor with GAD65 and VGLUT1 in the amygdala. Percentage of cells that co-express D3 receptors and GAD65 were compared to percentage of cells that co-express D3 receptors and VGLUT1. Comparisons were made between male and female drd3-EGFP mice at postnatal day 35 (P35) or 70 (P70) and found to exhibit statistically significant differences (P <0.05) using a z-test. The comparators are identified with common symbols (either *, ψ, or #). Number of cells screened in each group was 30 (P35 male), 19 (P70 male), 32 (P35 female) and 9 (P70 female)

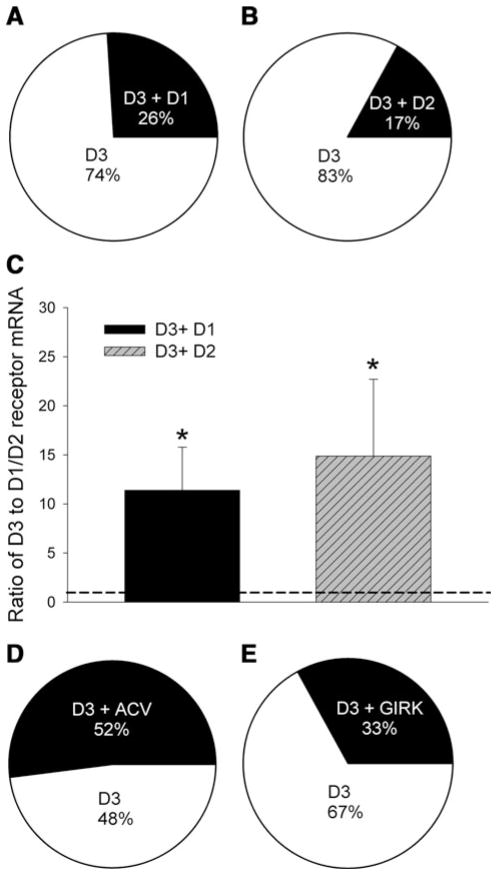

For this study, limited by the density and number of fluorescent cells in the septum region, we only performed single cell characterization of fluorescent cells from P35 male drd3-EGFP mice. In this age and sex, we observed that ~20% of the cells co-expressed D3 and D1 or D3 and D2 receptors (Fig. 14a, b). In both cell types, in each cell, the relative expression of D3 receptor mRNA was significantly greater than either the D1 or D2 receptor mRNA (Fig. 14c). Approximately, half the cells co-expressed D3 receptors and ACV (Fig. 14d) and 33% of the cells co-expressed D3 receptors and GIRK channels (Fig. 14e).

Fig. 14.

Co-expression of D3 dopamine receptor with other dopamine receptor subtypes, ACV and GIRK channels in the septum. Percentage of cells co-expressing D3 and D1 receptors (a), D2 receptors (b), adenylate cyclase V (ACV) isoform (e) and GIRK channels (f) in male drd3-EGFP mice at postnatal day 35 (P35). Number of cells screened was 42 (P35 male). In cells co-expressing D3 and D1 or D3 and D2 dopamine receptors, the relative mRNA expression was determined using real-time RT-PCR and expressed as a ratio of D3 to D1 or D2 receptor mRNA (c). *P <0.05, Mann–Whitney rank sum test, significantly different from equal expression (ratio = 1, represented by dashed line). Error bars are ±SEM

D3 receptor protein is expressed in fluorescent cells of drd3-EGFP mice

The single cell RT-PCR results obtained in this study provides information on the expression of D3 receptor mRNA in the various brain regions; however, it is not known if these regions also express the D3 receptor protein. Unfortunately, the ability to detect D3 receptor protein is limited due to the lack of high-quality commercially available antibodies. Among the various antibodies that were characterized, none were able to distinguish D3 from other D2-like receptors; however, we took advantage of the results in Figs. 9 and 10, which showed that the retrosplenial cortex and dorsal subiculum are two brain regions where there is no co-expression of D3 and D2 receptors. We performed immunohistochemistry on these brain regions to determine if the fluorescent cells from the drd3-EGFP mice co-labeled with an antibody for D3 receptor protein. The results in Fig. 15 show that majority of the cells expressing EGFP in the retrosplenial cortex and dorsal subiculum co-labeled with the D3 receptor antibody. As expected, the labeling also appeared to be limited to the cell membrane. Taken together, the results in Fig. 15 suggest that the D3 receptor protein is expressed in cells expressing D3 receptor mRNA in the dorsal subiculum and retrosplenial cortex.

Fig. 15.

D3 receptor-expressing fluorescent cells also express D3 receptor protein. Representative images of coronal sections obtained from an adult drd3-EGFP mouse shows D3 receptor-expressing fluorescent cells in dorsal subiculum (a–d) and retrosplenial cortex (e and f). The sections were stained with anti-D3 dopamine receptor antibody (c–f) and detected with the AlexaFluor® 594 secondary antibody (red). For each section, a separate image was captured using a CCD camera and filters that distinguish EGFP (green), AlexaFluor® 594 (red) and nuclear stain DAPI (blue). The images were a pseudo-colored and merged. a and c Images in which images obtained with all three filters were merged. b An image captured with a red filter of the section in a and is a negative control. In d–f the images were obtained by merging images captured using the green and red filters and demonstrate the overlap of D3 receptor mRNA and protein expression. Scale bars (yellow rectangles) in the panels are 30 μm (a, b, c and e) and 10 μm (d and f)

Discussion

Almost two decades after the cloning of D3 receptors, its in vivo function and signaling properties are not well understood (Ahlgren-Beckendorf and Levant 2004). Data from whole body D3 receptor knockout mice have suggested that the receptor plays a role in modulating locomotor activity, working memory and reward mechanisms (Pritchard et al. 2007; Glickstein et al. 2002; Narita et al. 2003). The expression of D3 receptors in various brain regions has been described in rodents, nonhuman primates and humans under normal physiological and pathological conditions (Ariano and Sibley 1994; Landwehrmeyer et al. 1993; Meador-Woodruff et al. 1996; Seeman et al. 2006). Changes in D3 receptor expression have been reported in various neurological and neuropsychiatric disorders (Gurevich et al. 1997; D’Souza et al. 1997; Segal et al. 1997). However, many of these studies typically lack single cell level resolution and do not compare differences across age and sex. Furthermore, these expression studies typically focus on the expression of D3 receptors and not what it is co-expressed with. Given the cross talk between different receptor signal transduction pathways, and the recent focus on receptor heteromultimerization, it becomes important to consider changes in expression of co-expressed receptors and signaling effectors in various disorders. To begin addressing these deficits, we undertook this project and studied the co-expression pattern of D3 receptor at the single cell level in various brain regions where the receptor is expressed at high levels. We also compared these co-expression patterns between male and female mice at the periadolescent (P35) and adult age (P70). Previous studies have shown differences in the dopaminergic system between sexes and the two age groups (Andersen and Teicher 2000; Teicher et al. 1995; Andersen et al. 1997).

High density of fluorescent cells were found in the olfactory tubercle, Islands of Calleja, shell region of nucleus accumbens, mammillary body, retrosplenial cortex and the dorsal but not ventral subiculum (Figs. 1, 2). The results confirmed the endogenous expression of D3 receptor mRNA in individual fluorescent cells isolated from various brain regions of the drd3-EGFP mice. There was a relatively low level of ectopic expression of the drd3-EGFP transgene in the brain regions examined, wherein a fluorescent cell that was positive for GAPDH was negative for D3 receptor mRNA expression. This is an important consideration, as the random nature of transgene integration often results in mouse lines with very different pattern of expression, which does not match the endogenous expression of the gene being studied. The results in Figs. 1 and 2 shows that the general pattern of EGFP expression in our drd3-EGFP line is consistent with the results of previous D3 receptor distribution studies in mouse brain (Diaz et al. 2000). This validation is important for the future use of these mice in experimental paradigms where the distribution and expression of D3 receptors will be compared between normal and diseased states. Examples include drd3-EGFP mouse models of Parkinson’s disease, psychosis and drug abuse.

The results suggest that in all brain regions examined, D3 receptor expression, in vivo, in post-weaned mice is limited to neurons. While our study showed that the D3 receptor is not expressed with the astrocytic marker GFAP, it has been reported that the D3 receptor expression is observed in oligodendrocyte precursors during development and in primary glial cultures (Bongarzone et al. 1998). Several studies suggest that D3 receptor is important for neurogenesis in adult rat and mice subventricular zone (Van Kampen et al. 2004; Kim et al. 2010) and we observed D3 receptor-expressing fluorescent cells in this region of the drd3-EGFP mice. Our results are also the first to comprehensively show regional differences in localization of the D3 receptor in GABAergic versus glutamatergic neurons. Given the inhibitory role of D3 receptors, excitatory glutamatergic neurons in the retrosplenial cortex, dorsal subiculum and mammillary body are likely to be inhibited by the activation of the D3 receptor, attenuating the excitatory output from these regions. In contrast, D3 receptor activation in the nucleus accumbens, Islands of Calleja, olfactory tubercle and septum is likely to inhibit the GABAergic neurons, enhancing the excitatory output of these regions. In both nucleus accumbens and CA1 pyramidal neurons, D3 receptor activation has been proposed to modulate GABAergic neurons by increasing GABAA receptor endocytosis (Chen et al. 2006; Swant et al. 2008).

In the amygdala, D3 receptor expression is observed in both the glutamatergic projection neurons and GABAergic interneurons. One of the most interesting observations in the amygdala was the switch in neurotransmitter phenotype of the D3 receptor-expressing cells. The percentage of D3 receptor-expressing GABAergic cells decreased and the percentage of D3 receptor-expressing glutamatergic cells increased from P35 to P70 (Fig. 13). Given the inhibitory function of D3 receptors, this postnatal developmental switch most likely plays an important role in the function of amygdala as the animal matures from periadolescence to adulthood. A previous study on rats has shown that there is a significant decrease in the number of neurons in the amygdala between adolescence and adulthood; however, the type of neurons that were lost was not determined (Rubinow and Juraska 2009). Our results lead us to speculate that in mice there might be a loss of D3 receptor-expressing GABAergic neurons and a gain of D3 receptor-expressing glutamatergic neurons in the amygdala from periadolescence to adulthood.

The absence of D3 receptor and tyrosine hydroxylase co-expression in any of the brain regions studies suggest that D3 receptors are not expressed in catecholaminergic neurons including both noradrenergic and dopaminergic neurons that are present in these brain regions (Devoto et al. 2001; Gonzalo-Ruiz et al. 1992). Previous studies have shown that the D3 receptor is expressed in the substantia nigra and ventral tegmental area (Diaz et al. 2000). While we observed a significant number of fluorescent cells in these brain regions, the density of fluorescent cells was low and not amenable to our acute dissociation and single cell analysis protocol.

The co-expression of D3 receptor with other dopamine receptor subtypes varied significantly based on region, sex and age. In all the brain regions examined, the co-expression of D3 receptors with other dopamine receptor subtypes was primarily limited to D1 and D2 dopamine receptors. The only exception was the amygdala where the D3 receptor was co-expressed with D5 dopamine receptors in ~25% of the cells in the P35 male and P70 female groups. We will discuss the D3–D1 receptor and D3–D2 receptor co-expression patterns in the different brain regions separately. In the nucleus accumbens, the percentage of cells co-expressing D3 and D1 receptors increased from periadolescence to adulthood in males but not in females. Across sex, the percentage of cells co-expressing D3 and D1 receptors in female mice was significantly less than males. However, in both sexes, the relative levels of D1 receptor mRNA increased from periadolescence to adulthood. The observed expression pattern is intriguing given the role of D1 and D3 receptors in the nucleus accumbens in addictive behavior. Periadolescent male mice, but not adult male mice, show cocaine- or amphetamine-induced upregulation of Δ-FosB in the nucleus accumbens (Ehrlich et al. 2002), perhaps reflecting the alteration in percentage of cells co-expressing D3 and D1 receptors or alterations in the relative level of D3 and D1 receptor mRNA in each cell (Fig. 5). With regard to sex differences, it has been reported that adult female mice consume more alcohol than adult male mice, a behavior associated with limbic reward pathways (Hungund et al. 2003). This sex difference correlates with the significant differences in the percentage of D3 and D1 co-expressing cells in nucleus accumbens of adult male and female mice (Fig. 5a). In the Islands of Calleja and the olfactory tubercle, the percentage of cells co-expressing D1 and D3 receptors ranges from 13 to 43% with no significant age or sex differences, with the exception of olfactory tubercle where there was a significant increase in the percentage of cells co-expressing D3 and D1 receptors between female periadolescents (P35) and female adults (P70). Recent studies suggest that the olfactory tubercle and Islands of Calleja are regions that integrates odor and sound processing pathways with reward and memory pathways in the ventral striatum and hippocampus (Wesson and Wilson 2010, 2011). Given the high expression of D3 receptor in the olfactory tubercle, Islands of Calleja, ventral striatum and dorsal subiculum, it is very likely that the D3 receptor plays an important role in the sensory integration process.

Unlike the ventral striatum, the co-expression of D3 and D1 receptors in the retrosplenial cortex and dorsal subiculum is limited to animals of a specific sex and age. In the retrosplenial cortex, the co-expression is limited to the P70 female group (Fig. 9a), and even in this group, the relative expression of D3 receptor mRNA is ~500-fold higher than D1 receptor mRNA in each cell (Fig. 9b); therefore, it is likely that there are minimal D3–D1 interactions at the single cell level in the retrosplenial cortex. Human and rodent studies suggest that the retrosplenial cortex is involved in learning, episodic memory and emotional behavior (Rosenbaum et al. 2004; Piefke et al. 2007; Haijima and Ichitani 2008; Aggleton 2010). Glutamatergic neurotransmission via NR2A subunit containing NMDA receptor has been implicated in these processes (Corcoran et al. 2011). The robust expression of D3 receptor in glutamatergic neurons of the retrosplenial cortex suggest that the receptor plays an important role in spatial learning and memory. Indeed, D3 receptor knockout mice have deficits in spatial working memory (Glickstein et al. 2002). As in the retrosplenial cortex, the co-expression of D3 and D1 receptors in the dorsal subiculum is limited to a specific age and sex; however, unlike the retrosplenial cortex, the co-expression is present in the P70 male group in the dorsal subiculum (Fig. 10a) and the relative expression of D1 receptor mRNA in each cell of this group is significantly greater than the D3 receptor mRNA (Fig. 10b). This might facilitate D3–D1 receptor interaction and signaling cross talk between the receptors in P70 male and differentially influence function compared to other groups. The dorsal subiculum has been implicated in processing spatial information, with compass cells for coding head position in space (Taube 2007). With its projections into the retrosplenial cortex, mammillary body and septal nucleus, the dorsal subiculum is involved in the orientation of movement, navigation and exploration (Fanselow and Dong 2010). In the mammillary body, the highest density of D3 receptor-expressing fluorescent cells was in the medial mammillary nuclei. Significant co-expression of D3 and D1 receptors in the mammillary body was found in the P35 male group, which reduced dramatically as the animal aged from periadolescence to adulthood (Fig. 11a). The high co-expression in the periadolescent male was also accompanied by a ~2-fold higher expression of D1 receptor mRNA compared to D3 receptor mRNA in each cell that co-expressed the two receptors (Fig. 11b). D3 and D1 receptor co-expressing cells were essentially absent in the female groups regardless of age. Interestingly, a previous study in periadolescent rats showed that spatial learning in males was significantly better than in females (Cimadevilla et al. 1999). The mammillary body is also involved in spatial working memory, and the medial mammillary nuclei, in particular, is considered a relay center for the theta rhythms generated in the hippocampus (Vann and Aggleton 2004). The high expression of D3 receptor in the medial mammillary nuclei suggests that the receptor might play a role in modulating the relaying of theta rhythm-encoded information. In our limited analysis of fluorescent cells from the amygdala and septum, we observed that in general ~30% of the cells in these regions co-express D3 and D1 receptors. The exception was the amygdala from P70 female where ~67% of the cells co-expressed D3 and D1 receptors.

Unlike D3–D1 receptor co-expression, the D3 and D2 receptor co-expression was more limited. While D3 and D1 receptors have different signaling function, D3 and D2 receptors have very similar signaling functions and couple to similar downstream effectors. However, we have previously reported that despite coupling to similar effectors, the properties of coupling are very different (Kuzhikandathil et al. 2004). The D3 but not D2 receptors exhibit tolerance and slow response termination (SRT) properties. The tolerance property of D3 receptor describes the progressive decrease in receptor signaling function upon repeated stimulation by classical agonists, including dopamine. The SRT property describes the prolongation of time taken to terminate the signaling function of the D3 receptor after removal of the agonist. The highest percentage of cells co-expressing D3 and D2 receptors was found in the nucleus accumbens (Fig. 5c) and olfactory tubercle (Fig. 7c). In the Islands of Calleja a relatively low percentage of cells co-expressed D3 and D2 receptors (Fig. 6c). In all three regions, the D3 and D2 receptor co-expression varied significantly with sex and age. Comparing the co-expression in all three regions also revealed an unusual expression pattern (Figs. 5c, 6c, 7c); the percentage of cells co-expressing D3 and D2 receptors was similar in periadolescent male (P35) and adult female (P70). Furthermore, the percentage of cells co-expressing D3 and D2 receptor was similar in periadolescent female (P35) and adult male (P70). The functional significance of this intriguing reciprocal D3–D2 receptor co-expression pattern is not clear, but it is not seen with other co-expressed genes that we studied. In addition, when we examined the relative expression level of D3 and D2 receptor mRNA in each cell from the three regions, this reciprocal expression pattern was not observed (Figs. 5d, 6d, 7d). In cells co-expressing D3 and D2 receptors, in all three regions, the mRNA levels were relatively equal except in female animals in the nucleus accumbens and Islands of Calleja.

Unlike the ventral striatum regions, fluorescent D3 receptor-expressing cells in the retrosplenial cortex and dorsal subiculum did not co-express D3 and D2 receptors. These regions represent an ideal in vivo location to characterize D3 receptor signaling function pharmacologically at the single cell level without the confounding effects of agonists binding to other D2-like receptors. D3 and D2 receptor co-expressing cells were present in the mammillary body, amygdala and septum. In both mammillary body and amygdala, there was a significant increase in D3–D2 receptor co-expressing cells in female P70 mice (Figs. 11c, 12c). In particular, 72% of the amygdala cells from P70 female co-expressed D3 and D2 receptors, the highest percentage of co-expression in all the brain regions studied here. Analyzing the D3–D2 receptor and D3–D1 receptor co-expression in the amygdala of adult female mice, we observed that D3 receptor-expressing cells in this group co-express both D1 and D2 receptors. The functional implication of co-expression of all three dopamine receptor subtypes in one cell will be interesting to decipher.

The in vivo signaling function of D3 receptor is not well understood as attempts to study its signal transduction pathways are confounded by lack of selective agonists that unequivocally distinguish D3 receptor from otherD2-like receptors. In heterologous expression systems, our group and others have shown robust coupling of the D3 receptor to ACV and GIRK channels. With the long-term goal of studying these two D3 receptor coupled signal transduction pathways in vivo, we focused on the co-expression of D3 receptor with ACV and GIRK channels in various brain regions and across age and sex. The co-expression of D3 receptor with ACV was relatively high in all brain regions studied and in each region the co-expression varied significantly with age and sex. The co-expression of D3 receptor with GIRK channels was more heterogeneous across the various brain regions. Relatively low percentage of cells co-expressed D3 receptor and GIRK channels in the nucleus accumbens, with moderate co-expression levels in the Islands of Calleja and olfactory tubercle. Retrosplenial cortex, subiculum, mammillary body and amygdala had a very high percentage of D3 receptor–GIRK co-expression (~50–90%). The percentage of cells co-expressing D3 receptor and GIRK channels varied less across age and sex when compared to D3 receptor–ACV co-expression. Taken together, the results suggest that the co-expression of D3 receptor and ACV is more susceptible to developmental and sex influence. The results also identified brain regions that express D3 receptors and signaling effectors such as ACV and GIRK channels, without other D2-like dopamine receptor subtypes. For example, D3 receptor-expressing fluorescent cells in the retrosplenial cortex and dorsal subiculum could be used for in vivo signal transduction studies to delineate D3 receptor signaling function, without the confounding effects of other D2-like receptors. Similarly, in other brain regions, choosing the appropriate age and sex that does not express other D2-like receptors would also facilitate the characterization of D3 receptor function at the cellular level.

In summary, this paper provides a detailed profile of D3 dopamine receptor mRNA expression at the single cell level in mice. These results will form the basis for future studies in which we will determine changes in expression of dopamine receptors in response to pharmacological treatments in various experimental paradigms that model dopaminergic disorders such as Parkinson’s disease, psychosis and drug addiction.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a National Institutes of Health Grant (MH082376) to EVK.

References

- Abramoff MD, Magalhaes PJ, Ram SJ. Image processing with ImageJ. Biophotonics Int. 2004;11(7):36–42. [Google Scholar]

- Aggleton JP. Understanding retrosplenial amnesia: insights from animal studies. Neuropsychologia. 2010;48(8):2328–2338. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2009.09.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahlgren-Beckendorf JA, Levant B. Signaling mechanisms of the D3 dopamine receptor. J Recept Signal Transduct Res. 2004;24(3):117–130. doi: 10.1081/rrs-200029953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersen SL, Teicher MH. Sex differences in dopamine receptors and their relevance to ADHD. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2000;24(1):137–141. doi: 10.1016/s0149-7634(99)00044-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersen SL, Rutstein M, Benzo JM, Hostetter JC, Teicher MH. Sex differences in dopamine receptor overproduction and elimination. Neuroreport. 1997;8(6):1495–1498. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199704140-00034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ariano MA. Distribution of dopamine receptors. In: Neve KA, Neve RL, editors. The dopamine receptors. Humana Press; Totowa: 1997. pp. 77–103. [Google Scholar]

- Ariano MA, Sibley DR. Dopamine receptor distribution in the rat CNS: elucidation using anti-peptide antisera directed against D1A and D3 subtypes. Brain Res. 1994;649(1–2):95–110. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(94)91052-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bongarzone ER, Howard SG, Schonmann V, Campagnoni AT. Identification of the dopamine D3 receptor in oligodendrocyte precursors: potential role in regulating differentiation and myelin formation. J Neurosci. 1998;18(14):5344–5353. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-14-05344.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouthenet ML, Souil E, Martres MP, Sokoloff P, Giros B, Schwartz JC. Localization of dopamine D3 receptor mRNA in the rat brain using in situ hybridization histochemistry: comparison with dopamine D2 receptor mRNA. Brain Res. 1991;564(2):203–219. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(91)91456-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao J, Lotfipour S, Loughlin SE, Leslie FM. Adolescent maturation of cocaine-sensitive neural mechanisms. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2007;32(11):2279–2289. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen G, Kittler JT, Moss SJ, Yan Z. Dopamine D3 receptors regulate GABAA receptor function through a phospho-dependent endocytosis mechanism in nucleus accumbens. J Neurosci. 2006;26(9):2513–2521. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4712-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chio CL, Lajiness ME, Huff RM. Activation of heterologously expressed D3 dopamine receptors: comparison with D2 dopamine receptors. Mol Pharmacol. 1994;45:51–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]