Abstract

Background

Prior research has indicated that affiliation with delinquent peers activates genetic influences on delinquency during adolescence. However, because other studies have indicated that the socializing effects of delinquent peers vary dramatically across childhood and adolescence, it is unclear whether delinquent peer affiliation (DPA) also moderates genetic influences on delinquency during childhood.

Method

The current study sought to evaluate whether and how DPA moderated the etiology of delinquency in a sample of 726 child twins from the Michigan State University Twin Registry (MSUTR).

Results

The results robustly supported etiological moderation of childhood delinquency by DPA. However, this effect was observed for shared environmental, rather than genetic, influences. Shared environmental influences on delinquency were found to be several-fold larger in those with higher levels of DPA as compared to those with lower levels. This pattern of results persisted even when controlling for the overlap between delinquency and DPA.

Conclusions

Our findings bolster prior work in suggesting that, during childhood, the association between DPA and delinquency is largely (although not solely) attributable to the effects of socialization as compared to selection. They also suggest that the process of etiological moderation is not specific to genetic influences. Latent environmental influences are also amenable to moderation by measured environmental factors.

Keywords: Delinquency, delinquent peer affiliation, G × E, peer selection and socialization, shared environment

Introduction

Affiliation with delinquent peers is a strong predictor of future delinquency (Moffitt, 1993; Hektner et al. 2000; Deater-Deckard, 2001; Simonoff et al. 2004; Granic & Patterson, 2006; Kendler et al. 2008). Longitudinal studies (Simonoff et al. 2004), for example, have indicated that youth with delinquent peers are five times more likely than youth without delinquent peers to commit a crime during adolescence and emerging adulthood and are 10 times as likely to be diagnosed with antisocial personality disorder in adulthood. Similarly, treatment studies targeting reductions in delinquent peer affiliation (DPA), among other things, have been shown to successfully reduce delinquency (Curtis et al. 2004) and, moreover, have found that changes in DPA partially mediate the relationship between treatment adherence and delinquency outcomes (Huey et al. 2000). In short, DPA seems to play a ‘causal’ role in the development of youth delinquency.

The association between delinquent peers and delinquency is not entirely attributable to the socializing effects of delinquent peers, however. There is also strong evidence that selection partially underlies this association, such that children with delinquency seek out and/or attract peers who are prone to similar behaviors (Quinton et al. 1993; Granic & Patterson, 2006; Hill et al. 2008; Kendler et al. 2008; Beaver et al. 2009a, b). This process of peer selection probably reflects their shared interests in delinquent behaviors, particularly during adolescence, when the role of selection in peer group formation has been found to be especially strong (Hill et al. 2008; Kendler et al. 2008; Beaver et al. 2009a b; Burt et al. 2009). During childhood, the selection of delinquent peer groups also seems to be the result of rejection by non-delinquent peers, largely as a consequence of the youth’s disruptive behaviors (Hektner et al. 2000; Deater-Deckard, 2001).

Taken together, these findings suggest that both socialization and selection contribute to the association between DPA and child delinquency. What etiologic mechanisms might underlie these processes? Selection effects would be manifested as etiologic influences common to both DPA and delinquency. Common genetic influences, for example, would imply that some or all of the genes influencing delinquency also influence DPA. Findings of genetic mediation are typically interpreted as evidence of a gene–environment correlation (rGE) or non-random/genetically influenced exposure to particular ‘environmental’ experiences (Plomin et al. 1977; Scarr & McCartney, 1983). This rGE could be active, such that individuals at genetic risk for delinquency seek out friends with similar predilections, or evocative, such that individuals at genetic risk for delinquency are rejected by prosocial peers and thus have few alternatives. In either case, the association should manifest as genetic influences common to child delinquency and DPA. Alternately, the association between DPA and delinquency may be a function of common environmental influences, which could reflect either selection/mediational processes (e.g. the environmental factors increasing delinquency also increase affiliation with delinquent peer groups) or socialization processes (i.e. peer groups are directly influencing the presence of delinquency).

Perhaps more provocatively, DPA may exert its socializing influence on delinquency through etiological moderation, whereby exposure to delinquent peers serves to alter the etiological underpinnings of delinquency and, in this way, influences its expression. This possibility is quite exciting. Should exposure to delinquent peers modulate genetic or environmental risk for delinquency, it would highlight a dynamic mechanism that could be more specifically targeted in future interventions. To date, we know of only a few studies (Cleveland et al. 2005; Button et al. 2007; Harden et al. 2008; Beaver et al. 2009a; Hicks et al. 2009) examining whether DPA moderates the etiology of externalizing problems (i.e. antisocial personality disorder, conduct problems, and substance use and abuse). Results have uniformly revealed that, consistent with extant theories of gene–environment interactions (G × E; Shanahan & Hofer, 2005; Moffitt et al. 2006), genetic influences on externalizing problems were augmented by exposure to delinquent peers. Moreover, this pattern of moderation persisted over and above the effects of rGE/selection.

Importantly, however, all of the aforementioned G × E studies focused exclusively on externalizing problems during adolescence, a developmental period in which delinquency and substance use constitute more or less normative behaviors (Moffitt, 1993). As such, their results are likely to be specific to that particular developmental period, and may not generalize to periods of development (e.g. childhood) in which these behaviors are far less common. Indeed, a prominent theory of antisocial behavior posits that, whereas adolescent-onset antisocial behavior is thought to represent a milder and more normative occurrence, child-onset antisocial behavior is a more severe and persistent condition that often culminates in negative adult outcomes (Moffitt, 1993, 2003). The etiology of antisocial behavior also seems to differ by age of onset, such that child-onset antisocial behavior is significantly more heritable than is adolescent-onset antisocial behavior (Moffitt, 2003; Burt, 2009a). As this differential heritability could imply that gene–environment interplay also differs across child and adolescent delinquency (Moffitt et al. 2006), we would argue that G × E studies conducted on adolescent samples have little to say about etiological moderation during childhood.

Consistent with this argument, the psychological processes underlying affiliation with delinquent peers are also known to differ across childhood and adolescence. Although delinquent behaviors increase popularity with one’s peers during adolescence (Moffitt, 2003; Burt, 2009b), these same behaviors result in rejection by one’s peers during childhood (Hektner et al. 2000; Deater-Deckard, 2001). Moreover, a series of recent studies have concluded that, although selection is the primary mechanism underlying the association between DPA and delinquency during adolescence (Hill et al. 2008; Kendler et al. 2008; Burt et al. 2009), socialization is particularly important during childhood. Kendler et al. (2008), for example, examined retrospectively reported conduct disorder and DPA at ages 8–11, 12–14 and 15–17 years in 373 adult male twin pairs. Shared environmental influences on peer deviance (which were interpreted as evidence of socialization) influenced conduct disorder, but did so only during late childhood and mid-adolescence (rC = 0.92, 0.51 and 0.00 at ages 8–11, 12–14 and 15–18 years, respectively), thereby implying that socialization may be more influential during childhood than adolescence.

Given such findings, there is thus a need for a study evaluating whether and how DPA might moderate the etiology of delinquency during childhood in particular. The current study sought to do just this. Based on prior results (Kendler et al. 2008), we speculated that DPA may moderate shared environmental, rather than genetic, influences on delinquency.

Method

Participants

The Michigan State University Twin Registry (MSUTR) includes several independent twin projects (Klump & Burt, 2006). The 363 families included here were assessed as part of the ongoing Twin Study of Behavioral and Emotional Development in Children (TBED-C) within the MSUTR. Recruitment procedures, response rates and participation rates are detailed elsewhere (Klump & Burt, 2006). Ethnic group memberships in these data were endorsed at rates comparable to those of other area inhabitants (e.g. our sample: 85.1% Caucasian and 6.1% African-American; local census: 85.5% Caucasian and 6.3% African-American). Similarly, 14.4% of families in our sample lived below federal poverty guidelines, the exact same proportion seen for the state of Michigan more generally. Poverty rates in participants’ neighborhoods, as indicated by the 2005–2009 American Community Survey data, ranged from 0–76%, with an average of 10%.

Children gave informed assent, whereas parents gave informed consent for themselves and their children. The twins ranged in age from 6 to 11 years [mean (S.D.) = 8.3 (1.49) years] and 48% were female. Zygosity was established using a physical similarity questionnaire administered to the twins’ primary caregiver (Peeters et al. 1998). This questionnaire has accuracy rates of 95% or better (Peeters et al. 1998).

Measures

Delinquency

Mothers and fathers completed the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL; Achenbach & Rescorla, 2001) separately for each twin. Parents rated the extent to which a series of statements described each of their children’s behavior over the past 6 months using a three-point scale (from 0 = never to 2 = often/mostly true). We used the well-known rule-breaking (e.g. ‘cheat or lie’, ‘breaks rules’, ‘steals’; 17 items) scale, as prior research has linked peer influences specifically to non-aggressive delinquent behaviors (as opposed to physically aggressive behaviors, which may or may not be committed in the company of others; Moffitt, 1993, 2003; Burt, 2009b). Maternal informant reports were available for 99.7% twins; paternal informant reports were available on 86.0% of the twins. When only one informant report was available, that report was used. When both informant reports were available, data were averaged to create a composite of twin delinquency. The use of this combined informant approach is thought to allow for a more complete assessment of twin symptomatology than the use of either informant alone (Achenbach et al. 1987). There were no missing delinquency data following the creation of the composite. To adjust for positive skew, delinquency was log transformed prior to analysis (skews before and after transformation were 2.46 and 0.42, respectively).

DPA

Parents provided ratings for each of their twins’ entire peer groups using the Friends Inventory (Walden et al. 2004), with items scored using a four-choice response format (1 = none of my child’s friends are like that, 2 = just a few of my child’s friends are like that, 3 = most of my child’s friends are like that, and 4 = all of my child’s friends are like that). Items were summed to index DPA (five items, including ‘My child’s friends break the rules’ and ‘My child’s friends steal things from others’; α = 0.95 for both maternal and paternal informant reports). Maternal reports were available for 98.5% of twins; paternal reports were available on 84.8% of twins. When both informant reports were available, data were averaged across informant reports, creating a composite report of each twin’s DPA. When only one informant report was available, that report was used. Following the creation of the composite, peer data were available for 99.6% of twins.

One additional item, also administered as part of the Friends scale, was used to determine the extent to which the twins’ peer groups overlapped. In these data, 55% of pairs reportedly shared ‘all or nearly all’ of their friends, 37% shared ‘many but not all’ of their friends, 7% shared ‘a few’ friends, and 1% did not share any friends. Those twin pairs who shared all or nearly all of their friends were, not surprisingly, experiencing very similar levels of DPA (twin intraclass r = 0.74), whereas those who shared many or only a few friends were less similar in their DPA (twin intraclass r = 0.63 and 0.26 respectively).

Analyses

Twin studies make use of the difference in the proportion of genes shared between monozygotic (MZ; share all of their segregating genetic material) and dizygotic (DZ; share an average of 50% of their segregating genetic material) twins to estimate the relative contributions of additive genetic (a2), shared environmental (c2; environmental factors that make twins similar to each other) and non-shared environmental effects plus measurement error (e2; environmental factors that make twins different from each other) to the variance within observed behaviors or characteristics (phenotypes). More information on twin studies is provided elsewhere (Plomin et al. 2008).

Moderation analyses

We first evaluated whether and how DPA might moderate the etiology of child delinquency using a series of nested moderator models (Purcell, 2002). Twins are not required to be concordant on the value of the moderator. The first and least restrictive model allowed for both linear and nonlinear moderation of the genetic, shared and non-shared environmental contributions (i.e. a, c, e) to delinquency. Linear (i.e. A1, C1, E1) and nonlinear (i.e. A2, C2, E2) moderators were added to these paths using the following equation:

We then fitted a series of more restrictive moderator models, constraining the nonlinear and linear moderators to be zero and evaluating reductions in model fit.

Several steps of data preparation were necessary for these analyses. Purcell (2002) recommends that unstandardized estimates be presented for these models, as standardized estimates can obscure or distort absolute changes across levels of the moderator. We therefore standardized our log-transformed delinquency score to facilitate interpretation of the unstandardized values. Next, to permit the meaningful estimation of genetic and environmental parameter estimates at each level of the moderator (Purcell, 2002), we trichotomized our continuous DPA variable into low, moderate and high levels of DPA (coded 0, 1 and 2 respectively), thereby placing a minimum of 100 twin pairs at each level.

Because these interaction models effectively involve fitting a separate biometric model for each individual as a function of their DPA, they require the use of full-information maximum-likelihood (FIML) raw data techniques. Mx, a structural equation modeling program (Neale et al. 2003), was used to fit models to the transformed raw data. The minimized value of minus twice the log likelihood (−2lnL) for each model is then compared with the −2lnL obtained in the previous, less restrictive model to yield a likelihood ratio χ2 test for the significance of the moderator estimates. Non-significant changes in χ2 indicate that the more restrictive model (i.e. that model with fewer parameters and thus more degrees of freedom) provides a better fit to the data. As the χ2 test does not place any value on parsimony, however, and is thus sometimes considered overly conservative, we also made use of Akaike’s Information Criterion (AIC; Akaike, 1987) to determine the best-fitting model. The AIC balances model fit with parsimony, and is the most commonly used fit index within the field of behavioral genetics. The lowest AIC among a series of nested models is considered best.

Mediation analyses

We next sought to evaluate the origins of covariation between DPA and delinquency so as to ensure that any positive findings of moderation were not in fact a function of mediation or selection in disguise. To evaluate this possibility, we made use of a standard bivariate model in Mx (Neale et al. 2003), in which the variance within, and the covariance between, DPA and delinquency were decomposed into their genetic and environmental components. We also computed genetic and environmental correlations between delinquency and DPA so as to specify the proportions of etiological overlap. A shared environmental correlation of 1.0, for example, would indicate that all shared environmental influences are common to both phenotypes, whereas a correlation of zero would indicate no shared environmental overlap. Should the etiological sources of covariation differ from the sources of moderation, it would argue against the possibility that positive findings of moderation are in fact a function of mediation. Note that DPA was measured continuously for these analyses (the trichotomized variable was necessary only for the moderation analyses).

Results

Mean levels of delinquency varied significantly across sex (Cohen’s d effect size = 0.31, p < 0.05), such that boys [mean (S.D.) = 1.81 (1.93), 7.7% of which scored in the marginal to clinically significant range; Achenbach & Rescorla, 2001] evidenced significantly higher rates of delinquency than did girls [mean (S.D.) = 1.28 (1.51), 7.2% scored in the marginal to clinically significant range]. Mean levels of DPA similarly varied across sex (Cohen’s d effect size = 0.50, p < 0.05), such that boys [mean (S.D.) = 6.63 (1.17)] evidenced higher levels of DPA than did girls [mean (S.D.) = 6.06 (1.10)]. As such, sex was regressed out of the continuous data prior to analysis, in keeping with prior recommendations (McGue & Bouchard, 1984). As expected, childhood delinquency was significantly correlated with DPA (r = 0.33, p < 0.001).

Primary moderation analyses

Test statistics for our primary moderator model are reported in Table 1 (see model 1). As seen there, the nonlinear moderators could be fixed to zero without a significant decrease in fit, suggesting minimal nonlinear shifts in the etiology of delinquency with DPA. Additionally fixing the linear moderators to zero, however, significantly worsened the fit. These results indicate that the etiology of delinquency varies linearly with DPA.

Table 1.

Fit indices for all models

| Model | −2lnL | df | AIC | Δχ2 | Δdf | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Primary G×E model, allowing DPA to moderate child delinquency | ||||||

| (a) Linear and nonlinear moderation | 1819.42 | 709 | 401.42 | – | – | – |

| (b) Linear moderation | 1819.66 | 712 | 395.66 | 0.24 | 3 | 0.971 |

| (c) No moderation | 1829.88 | 715 | 399.88 | 10.22 | 3 | 0.017 |

| 2. Bivariate model | ||||||

| (a) Full ACE model | 3684.44 | 1438 | 808.44 | – | – | – |

| (b) AE model | 3713.57 | 1441 | 831.57 | 29.13 | 3 | <0.001 |

| (c) CE model | 3707.27 | 1441 | 825.27 | 22.83 | 3 | <0.001 |

| 3. Supplemental GrE model, allowing DPA (controlling for overlap with delinquency) to moderate child delinquency | ||||||

| (a) Linear and nonlinear moderation | 1864.19 | 709 | 446.19 | – | – | – |

| (b) Linear moderation | 1865.26 | 712 | 441.26 | 1.07 | 3 | 0.784 |

| (c) No moderation | 1874.46 | 715 | 444.46 | 9.20 | 3 | 0.027 |

| 4. Supplemental GrE in the presence of the rGE model | ||||||

| (a) Linear ACE moderation | 3653.04 | 1423 | 807.04 | – | – | – |

| (b) Linear A moderation only | 3658.51 | 1427 | 804.51 | 5.47 | 4 | 0.242 |

| (c) Linear C moderation only | 3655.16 | 1427 | 801.16 | 2.12 | 4 | 0.714 |

| (d) Linear E moderation only | 3664.46 | 1427 | 810.46 | 11.42 | 4 | 0.022 |

| (e) No moderation | 3665.04 | 1429 | 807.04 | 12.00 | 6 | 0.062 |

G×E, Gene–environment interactions; DPA, delinquent peer affiliation; rGE, gene–environment correlation; df, degrees of freedom; AIC, Akaike’s Information Criterion.

For models 1 and 3, the fit of each model is compared to that of the less restrictive model preceding it. For models 2 and 4, each model is compared to the first (and less restrictive) model (i.e. models 2a and 4a respectively). The best-fitting model in each case is indicated by the lowest AIC value and also by non-significant changes in χ2, and is highlighted in bold font.

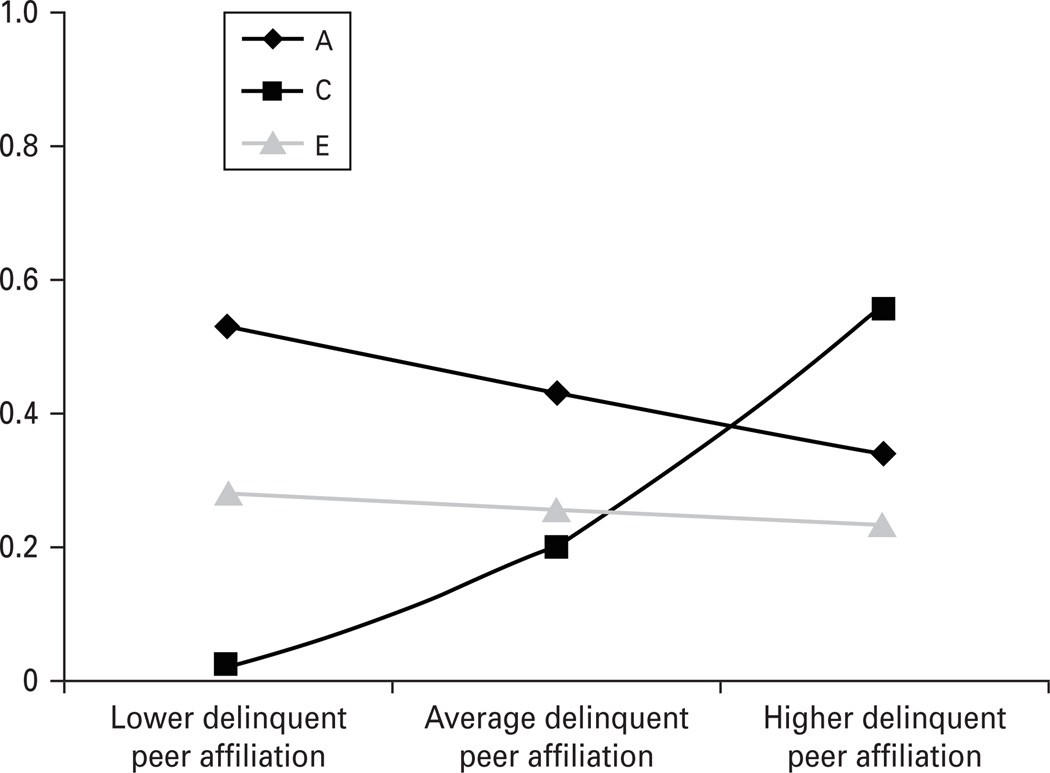

For our best-fitting primary model, we made use of the estimated paths and moderators (presented in Table 2) to calculate and plot (Fig. 1) the unstandardized genetic and environmental variance components at each level of DPA. As shown in Table 2, A and E influences on delinquency seemed to decrease somewhat with increasing levels of DPA, but these effects were not statistically significant. By contrast, shared environmental influences were observed to increase dramatically and significantly with increasing levels of DPA, such that shared environmental influences on delinquency were nearly fivefold larger for those experiencing higher as compared to lower levels of DPA†.

Table 2.

Unstandardized path and moderator estimates for the best-fitting linear moderation model (model 1b in Table 1)

| Paths | Linear | Quadratic | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a | c | e | A1 | C1 | E1 | A2 | C2 | E2 |

| 0.729* (0.545–0.847) |

0.149 (−0.212 to 0.441) |

0.527* (0.448 to 0.624) |

−0.073 (−0.244 to 0.078) |

0.298* (0.095 to 0.467) |

−0.022 (−0.102 to 0.060) |

– | – | – |

Paths and moderators are presented, with 95% confidence intervals in parentheses. A, C and E (both upper and lower case) represent genetic, shared and non-shared environmental parameters respectively. In the left portion of the table, the path estimates (i.e. a, c and e) are presented. Because low delinquent peer affiliation (DPA) was dummy coded as 0, these path estimates function as intercepts. The genetic and environmental variance components at lower levels of DPA can thus be obtained simply by squaring these path estimates. At each subsequent level, linear moderators (i.e. A1, C1, E1) are added to the paths using the following equation: Unstandardized variancetotal=[a + A1(delinquent peer)]2 + [c + C1(delinquent peer)]2 + [e + E1(delinquent peer)]2. Based on the model-fitting results (see model 1b in Table 1), quadratic moderators (i.e. A2, C2, E2) were not estimated. The variance component estimates calculated this way are presented in Fig. 1. An asterisk indicates that the estimate is significant at p<0.05.

Fig. 1.

Etiological moderation of child delinquency by delinquent peer affiliation (DPA). These are the results of model 1b in Table 1. A, C and E represent genetic, shared and non-shared environmental influences respectively. These estimates index the absolute (unstandardized) changes in genetic and environmental variance in child delinquency by DPA.

Mediation analyses

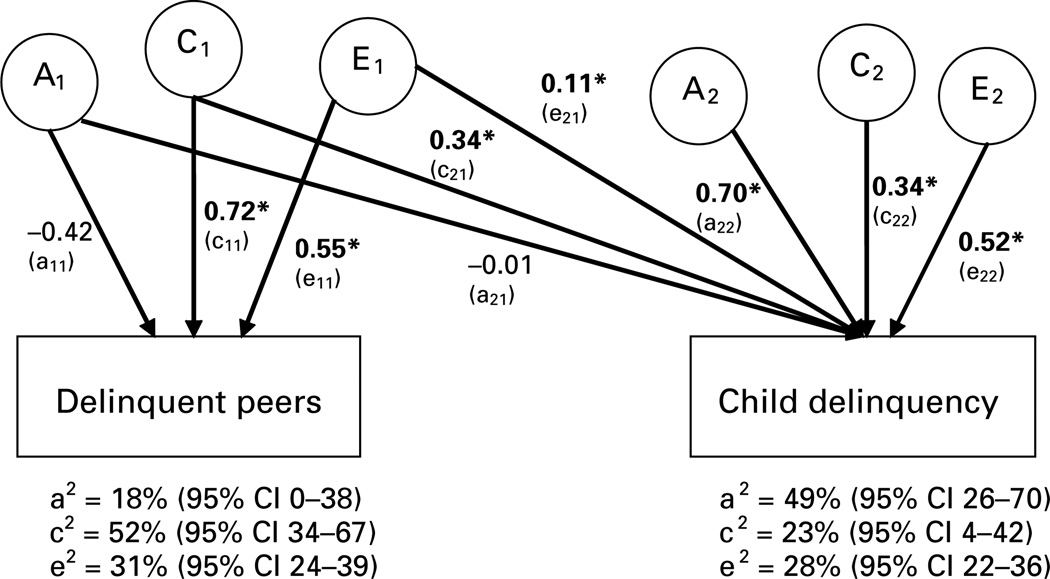

We next sought to confirm that the above findings of moderation were not a function of mediation (Purcell, 2002; Moffitt et al. 2006). The best-fitting model was the full ACE model (see model 2 in Table 1). The results are presented in Fig. 2. Only environmental influences were observed to overlap across the two phenotypes. In particular, 50% (rC = 0.71; 0.712 = 0.50) of the shared environmental influences on DPA overlapped with those on childhood delinquency.

Fig. 2.

Standardized estimates of additive genetic (A), shared environmental (C) and non-shared environmental (E) contributions to the association between delinquent peer affiliation (DPA) and child delinquency. These are the results of model 2a in Table 1. Path coefficients for DPA were squared to index the percentage of variance accounted for (as presented below, followed by their 95% confidence intervals in parentheses). Path coefficients for child delinquency were squared and then summed to index the proportion of variance accounted for (e.g. e21 and e22 were estimated to be 0.11 and 0.52 respectively; 0.112 + 0.522 = 0.28). An asterisk indicates that the path is significant at p < 0.05. Genetic, shared and non-shared correlations are not presented above but were estimated to be 0.02, 0.71 and 0.20 respectively (the latter two were significantly larger than zero at p < 0.05).

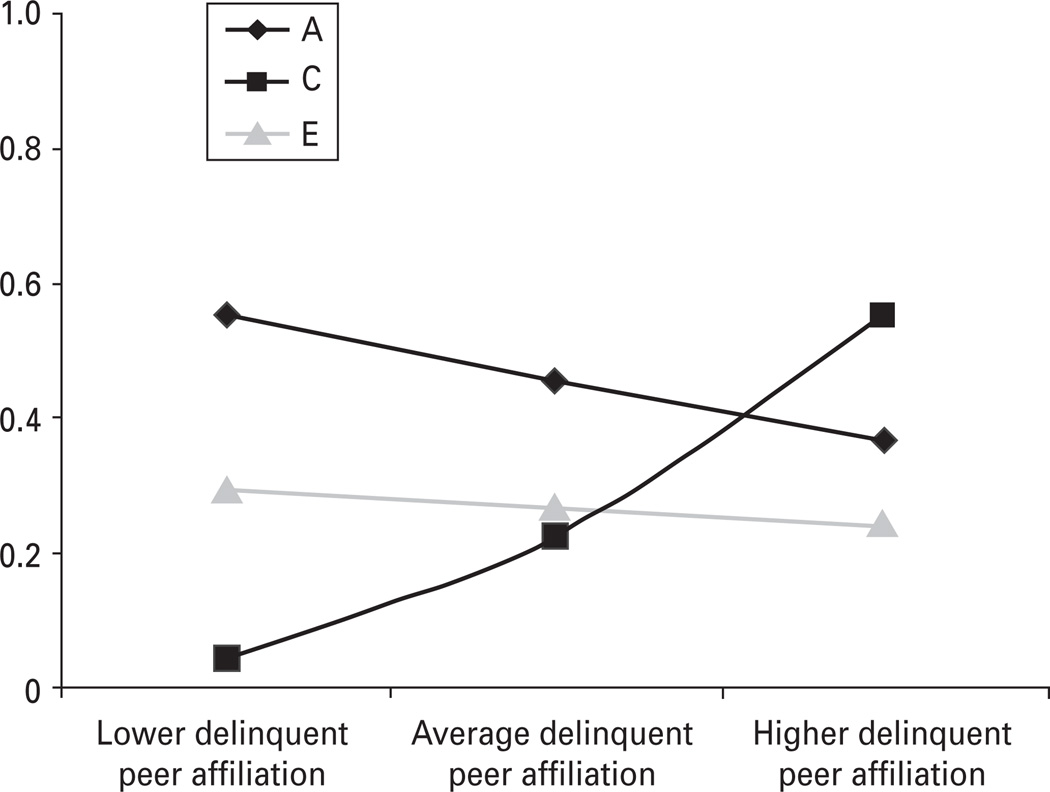

These results are clearly consistent with the possibility that the above moderation results are in fact a function of meditational processes. In other words, what seems to be the etiological moderation of delinquency by DPA may in fact be a function of common C. To evaluate this possibility empirically, we performed two supplemental analyses. We first reran our original moderation analyses using a residualized moderator (i.e. delinquency was regressed onto DPA; the DPA residual, which contains only that variance that does not overlap with delinquency, was then trichotomized and used as our moderator variable). As before, the nonlinear, but not the linear, moderators could be dropped without a significant decrement in fit (see model 3 in Table 1). The results of the linear model are presented in Fig. 3. As seen there, the A and E moderators were again small and not significant. The shared environmental moderator, by contrast, was moderate in magnitude and significantly larger than zero. There is thus little evidence that the moderation of C on delinquency by DPA is a function of mediation.

Fig. 3.

Etiological moderation of child delinquency by delinquent peer affiliation (DPA), controlling for the overlap between child delinquency and DPA. These are the results of model 3b in Table 1. A, C and E represent genetic, shared and non-shared environmental influences respectively. These estimates index the absolute (unstandardized) changes in genetic and environmental variance in child delinquency by DPA, controlling for the latter’s overlap with child delinquency. The shared environmental moderator was significantly greater than zero (estimate = 0.270, p < 0.05). The genetic and non-shared environmental moderators were not significantly greater than zero (estimates = −0.069 and −0.026 respectively).

To confirm these impressions, however, we also ran the ‘G × E in the presence of rGE’ model (Purcell, 2002). In this model, the common and unique paths in the bivariate decomposition model (i.e. c21 and c22 respectively; see Fig. 2) are each allowed to vary as a function of a moderator. Only moderation of the unique path is thought to represent true etiological moderation. Consistent with the above results, the best-fitting model (see model 4 in Table 1) allowed for moderation of C, but not A or E. Examination of the common and unique C moderators further indicated that the common shared environmental path (i.e. c21) was small and non-significant (−0.060). By contrast, the moderator of the unique shared environmental path (i.e. c22) was moderate in magnitude (0.283) and was significantly greater than zero. These results further bolster our conclusion that the moderation of shared environmental influences on delinquency by DPA represents true etiological moderation.

Discussion

The aim of the current study was to evaluate whether DPA moderated the etiology of childhood delinquency. Our results robustly support this possibility: shared environmental influences on delinquency were observed to be several-fold larger in those with higher levels of DPA as compared to those with lower levels. Moreover, this pattern of results persisted even when controlling for the overlap between delinquency and DPA. These findings collectively suggest that affiliation with delinquent peers serves to exacerbate shared environmental influences on childhood delinquency.

Despite the consistency of our results, there are several limitations that should be considered. First, given our sample size (n = 363 pairs, 48% female), analyses incorporating sex in a meaningful way would have been unwieldy and underpowered. Fortunately, prior meta-analyses (Burt, 2009a, c) have indicated that heritability estimates for delinquency do not vary significantly across sex. We also did not examine the effects of age in our analyses. As other work has suggested that the effects of socialization by delinquent peers may be more prominent during childhood than in adolescence (Kendler et al. 2008), the current results should not be applied to other developmental periods (i.e. adolescence). Similarly, although we did not consider the effects of age of onset, our use of a child sample implies that many of the delinquent youth examined here suffer from early-onset antisocial behavior (Moffitt, 1993).

Next, parents reported on their twins’ delinquency and DPA, resulting in possible confounding by shared informant effects. Although a thorough examination of informant effects is beyond the scope of the current study, we sought to preliminarily confirm that our results were not simply a function of shared informant effects. To do so, we reran our primary moderator analyses for each of the four informant–phenotype pairings (e.g. father report of delinquency and mother report of DPA, etc.). The linear moderation model provided the best fit to the data across three of the four pairings, and was generally suggestive of shared environmental mediation. When examining paternal-reported delinquency and maternal-reported DPA, for example, the A1, C1 and E1 moderator values were −0.12, 0.20 and 0.00 respectively. Similarly, when examining paternal reports of both delinquency and DPA, the A1, C1 and E1 moderator values were 0.03, 0.18 and −0.02 respectively. Our results thus seem to be more or less robust to informant issues.

Our study also relied in part on the ‘G × E in the presence of rGE’ model described by Purcell (2002). Unfortunately, subsequent work has found problems of identifiability with this model (Rathouz et al. 2008), such that several alternative models (closely related to Purcell’s model but not involving G × E) fitted their simulated data as well as the ‘G × E in the presence of rGE’ model. They therefore concluded that the exclusive use of Purcell’s ‘G × E in the presence of rGE’ model could lead to the spurious detection of moderation effects. Fortunately, our findings of moderation extended to the straight G × E model (which is not affected by these equivalence issues), and did so even when controlling for the overlap between DPA and delinquency through regression. As such, our conclusions are not likely to stem from the problems described by Rathouz et al. (2008).

Finally, the current findings of shared environmental moderation of childhood delinquency are specific to affiliation with delinquent peers, and do not extend to affiliation with other sorts of peers. Indeed, other analyses with these data (Burt & Klump, unpublished observations) have indicated that affiliation with prosocial peers serves to suppress genetic influences on delinquency. Although this finding may seem counterintuitive given the current results, delinquent and prosocial peer affiliation are correlated only −0.39. Moreover, when entered simultaneously into a regression equation, both delinquent and prosocial peer affiliation independently predicted delinquency. Their unique associations with delinquency thus leave ample room for differential moderation of its etiology.

Conclusions

The results of the current study have two broad implications. First, the current results bolster prior work in suggesting that, during childhood, the association between DPA and delinquency is largely (although not solely) attributable to the effects of socialization. Kendler et al. (2008), for example, found evidence that shared environmental influences on peer deviance influenced conduct disorder differentially across development, such that socialization effects were important in late childhood but not in late adolescence (rC = 0.92, 0.51 and 0.00 at ages 8–11, 12–14 and 15–18 years respectively). The current findings confirmed the presence of prominent shared environmental mediation during childhood (rC in the current study was estimated to be 0.71), and also extended prior work by revealing the moderation of shared environmental influences on delinquency by DPA. The socializing influences of delinquent peers on child delinquency thus seem to operate through both moderation and mediation (although the latter cannot be confirmed in this study given the cross-sectional nature of these data). Future research should build on the present findings by examining these associations as they develop from childhood through early adolescence.

Second, building on the above, the current findings highlight the dynamic nature of environmental influences over the course of development. Specifically, although much has been made of the moderation of genetic influences by measured aspects of the environment (see especially Hicks et al. 2009), the current study suggests that this process of etiological moderation is not specific to genetic influences. Indeed, latent environmental influences also seem to be amenable to moderation by measured environmental factors. Although the latter are somewhat less straightforward to interpret, they can provide crucial insights into the development of psychopathology. In the current study, for example, our results are consistent with (at least) two possibilities: first, shared environmental influences on delinquency may directly reflect the influence of delinquent peers on child delinquency, such that twins become more similar in their delinquency (regardless of their genetic similarity) as a function of their common affiliation with delinquent peers. This sort of direct influence might take place through deviancy training (Granic & Patterson, 2006), in which children receive positive reinforcement for delinquent behaviors in their interactions with delinquent peers. A second possibility (noted also by Kendler et al. 2008) is that delinquent peers may serve to indirectly shape delinquency through common associations with other shared environmental influences (e.g. neighborhood effects, exposure to conflictive parenting styles; Dishion et al. 1995; Burt et al. 2007). As an example, delinquent children typically befriend delinquent peers from their own neighborhoods (Dishion et al. 1995), a potentially crucial explanation for the presence of shared environmental influences given that twin siblings (both MZ and DZ) reside in the same neighborhoods. Future research should seek to clarify these possibilities.

Acknowledgements

This project was supported by R01-MH081813 from the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIMH or the National Institutes of Health. We thank all participating twins and their families for making this work possible.

Footnotes

The notes appear after the main text.

Declaration of Interest

None.

It is well known that MZ twins share friends more often than do DZ twins. In these data, for example, 71.4% of MZ twins shared all or nearly all of their friends versus 39.0% of DZ twins. Although it is unlikely that our finding of shared environmental moderation is influenced by the differential sharing of peers across zygosity (the increased similarity of peer groups should instead influence genetic estimates), it would be worth clarifying that our results are not influenced by the differential similarity of MZ and DZ peer groups. We thus repeated our primary moderation analyses omitting those pairs (45% of the sample) who did not share most or all of their friends. The model allowing for linear shared environmental moderation provided the best fit to the data (full ACE linear model: −2lnL = 976.97 on 382 df, AIC = 212.79; linear C moderation model: −2lnL = 977.46 on 384 df, AIC = 209.46; no moderation model: −2lnL = 980.15 on 385 df, AIC = 210.15). The differential levels of peer similarity seen for MZ and DZ twins thus do not seem to be influencing our primary conclusions.

References

- Achenbach TM, McConaughy SH, Howell CT. Child/adolescent behavioral and emotional problems: implications of cross-informant correlations for situational specificity. Psychological Bulletin. 1987;101:213–232. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Achenbach TM, Rescorla LA. Manual for ASEBA School-Age Forms and Profiles. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont, Research Center for Children, Youth, and Families; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Akaike H. Factor analysis and AIC. Psychometrika. 1987;52:317–332. [Google Scholar]

- Beaver KM, DeLisi M, Wright JP, Vaughn MG. Gene-environment interplay and delinquent involvement: evidence of direct, indirect, and interactive effects. Journal of Adolescent Research. 2009a;24:147–168. [Google Scholar]

- Beaver KM, Schutt JE, Boutwell BB, Ratchford M, Roberts K, Barnes JC. Genetic and environmental influences on levels of self-control and delinquent peer affiliation: results from a longitudinal sample of adolescent twins. Criminal Justice and Behavior. 2009b;36:41–60. [Google Scholar]

- Burt SA. Are there meaningful etiological differences within antisocial behavior? Results of a meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review. 2009a;29:163–178. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2008.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burt SA. A mechanistic explanation of popularity: genes, rule-breaking, and evocative gene-environment correlations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2009b;96:783–794. doi: 10.1037/a0013702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burt SA. Rethinking environmental contributions to child and adolescent psychopathology: a meta-analysis of shared environmental influences. Psychological Bulletin. 2009c;135:608–637. doi: 10.1037/a0015702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burt SA, McGue M, Iacono WG. Non-shared environmental mediation of the association between deviant peer affiliation and adolescent externalizing behaviors over time: results from a cross-lagged monozygotic twin differences design. Developmental Psychology. 2009;45:1752–1760. doi: 10.1037/a0016687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burt SA, McGue M, Krueger RF, Iacono WG. Environmental contributions to adolescent delinquency: a fresh look at the shared environment. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2007;35:787–800. doi: 10.1007/s10802-007-9135-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Button TMM, Corley RP, Rhee SH, Hewitt JK, Young SE, Stallings MC. Delinquent peer affiliation and conduct problems: a twin study. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2007;116:554–564. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.116.3.554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cleveland HH, Wiebe RP, Rowe DC. Sources of exposure to smoking and drinking friends among adolescents: a behavioral-genetic evaluation. Journal of Genetic Psychology. 2005;166:153–169. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtis NM, Ronan KR, Borduin CM. Mutisystemic treatment: a meta-analysis of outcome studies. Journal of Family Psychology. 2004;18:411–419. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.18.3.411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deater-Deckard K. Annotation: Recent research examining the role of peer relationships in the development of psychopathology. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2001;42:565–579. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dishion TJ, Andrews DW, Crosby L. Antisocial boys and their friends in early adolescence: relationship characteristics, quality, and interactional process. Child Development. 1995;66:139–151. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1995.tb00861.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Granic I, Patterson GR. Towards a comprehensive model of antisocial development: a dynamic systems approach. Psychological Bulletin. 2006;113:101–131. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.113.1.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harden PW, Hill JE, Turkheimer E, Emery RE. Gene-envrionment correlation and interaction on peer effects on adolescent alcohol and tobacco use. Behavior Genetics. 2008;38:339–347. doi: 10.1007/s10519-008-9202-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hektner JM, August GJ, Realmuta GM. Patterns and temporal changes in peer affiliation among aggressive and non-aggressive children particpating in a summer school program. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 2000;29:603–614. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP2904_12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hicks BM, South SC, DiRago AC, Iacono WG, McGue M. Environmental adversity and increasing genetic risk for externalizing disorders. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2009;66:640–648. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2008.554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill JE, Emery RE, Harden PW, Mendle J, Turkheimer E. Alcohol use in adolescent twins and affiliation with substance using peers. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2008;36:81–94. doi: 10.1007/s10802-007-9161-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huey SJ, Henggeler SW, Brondino MJ, Pickrel SG. Mechanisms of change in multisystemic therapy: reducing delinquent behavior through therapist adherence and improved family and peer functioning. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2000;68:451–467. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendler KS, Jacobson KC, Myers JM, Eaves LJ. A genetically informative developmental study of the relationship between conduct disorder and peer deviance in males. Psychological Medicine. 2008;38:1001–1011. doi: 10.1017/S0033291707001821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klump KL, Burt SA. The Michigan State University Twin Registry (MSUTR): genetic, environmental, and neurobiological influences on behavior across development. Twin Research and Human Genetics. 2006;9:971–977. doi: 10.1375/183242706779462868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGue M, Bouchard TJJ. Adjustment of twin data for the effects of age and sex. Behavior Genetics. 1984;14:325–343. doi: 10.1007/BF01080045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moffitt TE. Adolescence-limited and life-course-persistent antisocial behavior: a developmental taxonomy. Psychological Review. 1993;100:674–701. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moffitt TE. Life-course persistent and adolescence-limited antisocial behavior: a research review and a research agenda. In: Lahey T, Moffitt E, Caspi A, editors. The Causes of Conduct Disorder and Serious Juvenile Delinquency. New York: Guilford; 2003. pp. 49–75. [Google Scholar]

- Moffitt TE, Caspi A, Rutter M. Measured gene-environment interactions in psychopathology. Perspectives on Psychological Science. 2006;1:5–27. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-6916.2006.00002.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neale MC, Boker SM, Xie G, Maes HH. Mx: Statistical Modeling. 6th edn. Richmond, VA 23298: Department of Psychiatry, VCU Box 900126; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Peeters H, Van Gestel S, Vlietinck R, Derom C, Derom R. Validation of a telephone zygosity questionnaire in twins of known zygosity. Behavior Genetics. 1998;28:159–161. doi: 10.1023/a:1021416112215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plomin R, DeFries JC, Loehlin JC. Genotype-environment interaction and correlation in the analysis of human behavior. Psychological Bulletin. 1977;84:309–322. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plomin R, DeFries JC, McClearn GE, McGruffin P. Behavioral Genetics. 5th edn. New York: Worth Publishers; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Purcell S. Variance components model for gene-environment interaction in twin analysis. Twin Research. 2002;5:554–571. doi: 10.1375/136905202762342026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinton D, Pickles A, Maughan B, Rutter M. Partners, peers, and pathways: assortative pairing and continuities in conduct disorder. Development and Psychopathology. 1993;5:763–783. [Google Scholar]

- Rathouz PJ, Van Hulle CA, Rodgers JL, Waldman ID, Lahey BB. Specification, testing, and interpretation of gene-by-measured-environment interaction models in the presence of gene-environment correlation. Behavior Genetics. 2008;38:301–315. doi: 10.1007/s10519-008-9193-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scarr S, McCartney K. How people make their own environments: a theory of genotype-environment effects. Child Development. 1983;54:424–435. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1983.tb03884.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shanahan MJ, Hofer SM. Social context and gene-environment interactions: retrospect and prospect. Journals of Gerontology. Series B, Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 2005;60:65–76. doi: 10.1093/geronb/60.special_issue_1.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simonoff E, Elander J, Holmshow J, Pickles A, Murray R, Rutter M. Predictor of antisocial personality: continuities from childhood to adult life. British Journal of Psychiatry. 2004;184:118–127. doi: 10.1192/bjp.184.2.118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walden SB, McGue M, Iacono WG, Burt SA, Elkins I. Identifying shared environmental contributions to early substance use: the importance of peers and parents. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2004;113:440–450. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.113.3.440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]