Background: Calmodulin inhibits the proteolysis of L-selectin's extracellular domains through an unknown mechanism.

Results: Calmodulin binds the juxtamembrane and predicted membrane-spanning regions of L-selectin in a calcium-dependent manner.

Conclusion: Binding of calmodulin to the cytoplasmic/transmembrane domain of L-selectin enacts a conformational change in the extracellular domains preventing cleavage.

Significance: Elucidating the mechanisms of L-selectin shedding is critical to understanding leukocyte trafficking.

Keywords: Biophysics, Calcium-binding Proteins, Calmodulin, Calorimetry, NMR, L-selectin, Calmodulin-Peptide Complex, Inside-out Signaling, Leukocyte Trafficking, Methyl Labeling

Abstract

The L-selectin glycoprotein receptor mediates the initial steps of leukocyte migration into secondary lymphoid organs and sites of inflammation. Following cell activation through the engagement of G-protein-coupled receptors or immunoreceptors, the extracellular domains of L-selectin are rapidly shed, a process negatively controlled via the binding of the ubiquitous eukaryotic calcium-binding protein calmodulin to the cytoplasmic tail of L-selectin. Here we present the solution structure of calcium-calmodulin bound to a peptide encompassing the cytoplasmic tail and part of the transmembrane domain of L-selectin. The structure and accompanying biophysical study highlight the importance of both calcium and the transmembrane segment of L-selectin in the interaction between these two proteins, suggesting that by binding this region, calmodulin regulates in an “inside-out” fashion the ectodomain shedding of the receptor. Our structure provides the first molecular insight into the emerging new role for calmodulin as a transmembrane signaling partner.

Introduction

Cell adhesion molecules expressed on leukocytes and endothelial cells intricately coordinate both the transit of granulocytes and monocytes from the bloodstream to inflamed tissue and the homing of naive lymphocytes to peripheral lymphoid organs (1, 2). Described by the adhesion cascade, several adhesion molecule families act to sequentially recruit and tether leukocytes to the vessel wall and then provide firm adhesion to and subsequent migration through the endothelial cell layer. The selectins are a three-member family of adhesion molecules expressed by leukocytes (L-selectin), platelets (P-selectin), and endothelial cells (E- and P-selectin), which in collaboration with their carbohydrate-presenting ligands execute leukocyte tethering and rolling along the luminal surface of venules that surround peripheral lymphoid organs and sites of inflammation (3).

The three selectins share analogous extracellular domains, including an N-terminal carbohydrate-binding lectin domain known to facilitate the observed rolling behavior of leukocytes despite the hydrodynamic shear force of the bloodstream (Fig. 1A). In contrast, the intracellular tails of these proteins are not conserved, a fact that suggests different modes of regulation and intracellular binding partners for each of the selectins. Although only 17 amino acids long, the cytoplasmic tail of L-selectin has been implicated in concentrating the protein to the tips of microvilli through its interaction with membrane-cytoskeleton cross-linking proteins α-actinin and the ezrin/radixin/moesin (ERM)3 family (4). The tail is phosphorylated by protein kinase C isozymes as well as Src-tyrosine kinase p56lck (5, 6) and has a key role in the down-regulation of L-selectin by mediating ectodomain shedding (7).

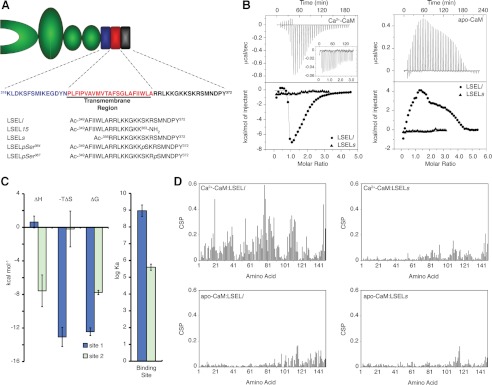

FIGURE 1.

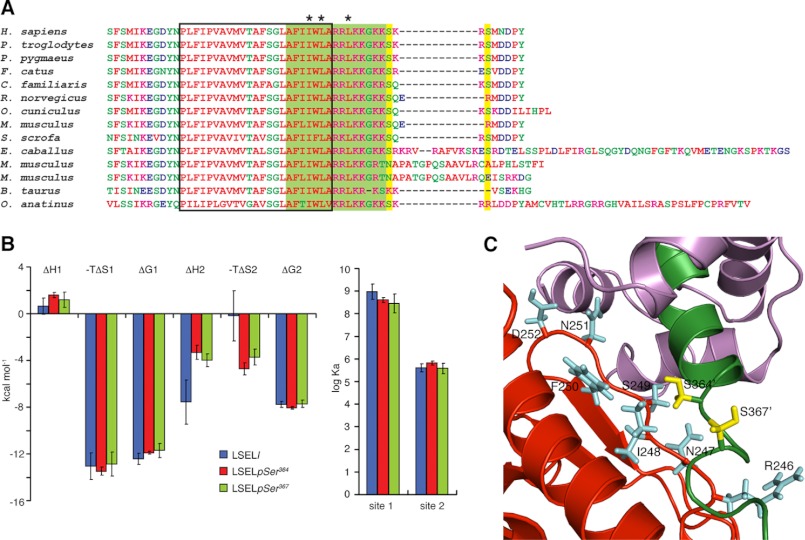

Ca2+ dependence and role of the transmembrane helix in the interaction between CaM and L-selectin. A, schematic of L-selectin with the membrane-proximal, transmembrane, and cytoplasmic domains highlighted. The four extracellular domains are shown in green and include (from left to right) a carbohydrate-binding lectin domain, an epidermal growth factor domain, and two short consensus repeat domains. The extracellular membrane-proximal region is indicated in blue, the single transmembrane helix is in red, and the cytoplasmic region is in black. The peptide sequences used in this study are placed at the bottom. B, calorimetric titration of Ca2+-CaM or apo-CaM with LSELl and LSELs peptides. Top panels, base line-corrected raw ITC titration of LSELl or LSELs (inset) into either Ca2+-CaM or apo-CaM. Bottom panels, overlay of the derived binding isotherms for the titration of LSELl and LSELs into either Ca2+-CaM or apo-CaM. C, thermodynamic parameters of the calorimetric titration of Ca2+-CaM with LSELl displayed as bars. Error bars, S.E. for three independent experiments. Apparent are the different energetic driving factors and the significant difference in affinity between the two peptide binding events. D, backbone HN and N CSPs induced upon binding of either LSELl or LSELs to Ca2+- or apo-CaM are plotted as a function of CaM amino acid residue.

Upon leukocyte activation through the engagement of G-protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) in vivo by cytokines and in vitro by phorbol esters, the extracellular domains of L-selectin are rapidly cleaved at a membrane-proximal cut site by tumor necrosis factor α-converting enzyme (TACE) (also known as A disintegrin and metalloprotease-17 (ADAM-17)) (8). This regulatory mode is unique in the selectin family to L-selectin. Once cleaved, the extracellular domains remain attached to their ligands or circulate as a soluble fraction in the plasma, whereas the cytoplasmic and transmembrane domains and 11 amino acid residues of the extracellular portion remain attached to the cell. A key player in the shedding response to leukocyte activation is the ubiquitous calcium (Ca2+)-binding protein calmodulin (CaM). Known to regulate numerous effectors involved in growth, proliferation, and movement (9, 10), CaM appears to associate constitutively with the L-selectin tail in resting leukocytes and thereby protects the extracellular domains from proteolytic cleavage (11, 12). Artificial activation of leukocytes with phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate induces the release of CaM from L-selectin and the shedding of the extracellular domains. It has been proposed that CaM exerts its effects by inducing a conformational change in the extracellular domains that renders the cleavage site resistant to proteolysis, a hypothesis supported by the relaxed sequence specificity but length prerequisite displayed by the cleavage site (13, 14).

To further understand the function of CaM in regulating L-selectin ectodomain shedding, we have examined the interaction between these two proteins at the structural level, in turn studying the requirement for Ca2+ as well as the role of the transmembrane domain and juxtamembrane region. We have found that both Ca2+ and a limited region of the L-selectin cytoplasmic domain, including a portion of the predicted membrane-spanning region and critical hydrophobic residues therein, are required for tight binding between CaM and L-selectin. A solution-based NMR structure explains the molecular details of this interaction.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Sample Preparation

Unlabeled and isotopically enriched CaM was recombinantly expressed in Escherichia coli BL21(DE3) cells containing the pET30b(+) expression vector as described previously (15). For isotope labeling, minimal medium containing 15N and either 1H,12C- or 1H,13C-labeled glucose in H2O or [2H,12C]glucose in 99.9% 2H2O was used. To create (1H/13C-methyl-Met)/2H/15N-labeled CaM, 100 mg/liter 1H-α,ϵ-13C-ϵ-2H-labeled methionine was added to the culture 1 h prior to induction with isopropyl β-d-1-thiogalactopyranoside (15). CaM samples were purified to homogeneity by Ca2+-dependent phenyl-Sepharose chromatography. All peptides were commercially synthesized (GeneScript) and determined to be more than 95% pure by matrix-assisted laser desportion/ionization mass spectroscopy and high pressure liquid chromatography. The concentration of CaM was determined using the equation, ϵ276 nm = 2900 m−1 cm−1.

Isothermal Titration Calorimetry

All ITC experiments were performed on a MicroCal VP-ITC microcalorimeter. CaM and peptide samples were dissolved in 20 mm HEPES (pH 7.3), 100 or 300 mm KCl, and either 1 mm CaCl2 or 3 mm EGTA and contained 262–889 μm peptide or 20 μm CaM. Data were fitted using the “two sets of sites” model in the MicroCal Origin software to determine the apparent stoichiometry (N), association constant (Ka), and the enthalpy change (ΔH) associated with binding. The ΔH and Ka values were then used to calculate the entropy of binding (TΔS) through the relationships ΔG = −RTlnKa and ΔG = ΔH − TΔS. The fitted Ka values were converted to Kd values using the relationship Kd = 1/Ka. The reported values represent the average and S.D. of three independent titrations performed at 30 °C.

NMR Spectroscopy

NMR experiments were performed on a Bruker Avance 500-MHz NMR spectrometer equipped with a triple resonance, inverse cryogenic probe with a single axis z gradient. Resonance assignments of the backbone and side chain atoms for CaM in complex with LSELl (L-selectin long peptide) were obtained using through-bond heteronuclear scalar couplings with the standard pulse sequences (15). For assignment of the side chain methyl group of the methionines, three-dimensional HMBC and LRCH experiments that record the long range correlations between the Hϵ/Cϵ and Hγ/Cγ atoms were used (16). Resonance assignments as well as intrapeptide NOEs for LSEL15 (L-selectin 15-mer peptide) in complex with 2H/15N-labeled CaM were obtained using two-dimensional COSY and two-dimensional F2-isotope-filtered NOESY spectra. Intermolecular NOEs for the (1H/13C-methyl-Met)/2H/15N-labeled CaM·LSEL15 complex were obtained from three-dimensional 13C-edited NOESY-HSQC spectra. A mixing time of 100 ms was employed for all NOESY spectra. 1DNH RDCs were measured using an IPAP-HSQC (17). NMR samples contained 0.2–0.8 mm 15N-, 13C/15N-, 2H/15N-, or (1H/13C-methyl-Met)/2H/15N-labeled CaM in 20 mm BisTris (pH 6.8), 100 mm KCl, 0.03% NaN3, 0.5 mm 2,2-dimethyl-2-silapentane-5-sulfonate, 90% H2O plus 10% 2H2O or 99.9% 2H2O, and either 4 mm CaCl2 or 5 mm EGTA. Samples for RDC measurements contained an extra 200 mm KCl and 16 mg/ml filamentous phage PF1 (Asla Biotech Ltd.) to achieve partial alignment. The increased KCl concentration is required to prevent CaM-phage interactions (15, 18) and did not have an effect on the binding affinity of LSELl for Ca2+-CaM (supplemental Table S1). To avoid the peak broadening that characterizes NMR spectra of the 1:2 interaction, samples of the 1:1 complex between labeled CaM and unlabeled LSELl or LSEL15 were created through careful titration monitored through 15N or 13C HSQC spectra: 0.1 molar increments of peptide were added to CaM until the cross-peaks of free Ca2+-CaM were replaced with those of the 1:1 spectra. For resonance assignment of the bound peptide, a 0.7:1 molar ratio of peptide to CaM was employed to ensure peptide saturation. 1H, 13C, and 15N chemical shifts in all spectra were referenced using 2,2-dimethyl-2-silapentane 5-sulfonate. Spectra were processed with the NMRPipe package (19) and analyzed using NMRView (20). Chemical shift perturbations (CSPs) in the 15N HSQC spectra of Ca2+-bound and apo-CaM complexed in turn with either the LSELl or LSELs (L-selectin short peptide) peptides were calculated as the weighted average chemical shift difference of the 1H and 15N resonances according to Equation 1 (21).

|

Structure Calculation

To determine the structure of the 1:1 Ca2+-CaM·LSEL15 complex, a protocol analogous to that published by Gifford et al. (15) was employed. Briefly, the PALES software was used to determine the domain orientation of CaM in the complex by fitting 109 measured HN-N RDCs to those back-calculated from CaM-peptide crystal structures deposited in the Protein Data Bank (22). Following the procedure outlined by Ikura and co-workers (18), only RDCs from structured regions of CaM (as defined by backbone chemical shifts) were chosen for analysis: residues 6–72 from the N-terminal domain and 85–144 from the C-terminal domain (18, 23). The structure of bound LSEL15 was solved using CYANA (version 2.0) (24) and subsequently used to derive upper distance limit restraints as well as hydrogen bonding and backbone dihedral angle restraints. CaM-specific information included HN-N RDCs, hydrogen bond restraints based on chemical shift index-derived secondary structure prediction, backbone dihedral angle restraints both obtained from the RDC-selected starting model and calculated from chemical shifts using TALOS (25), and Ca2+ ligand restraints. Distances between CaM and LSEL15 were provided by intermolecular NOEs between the methionine methyl groups of CaM and amino acid side chains of the bound peptide. Due to the lack of a suitable internal standard through which to calibrate these spectra, peak overlap, and the non-linear intensity of potential methyl-methyl NOEs, the intermolecular NOE distance restraints were binned into one distance class of 1.8–6.0 Å.

The structure calculation of the Ca2+-CaM·LSEL15 complex was performed using a previously established two-step, low temperature torsion angle simulated annealing protocol in the program Xplor-NIH (version 2.24) (15, 26, 27). Briefly, in the first step, the starting model built from the homologous crystal structure underwent Powell energy minimization and torsion angle dynamics at 200 K followed by simulated annealing in which the temperature was decreased from 200 to 20 K in ΔT = 10 K steps. The lowest energy structure was selected as the starting model for step 2. In the second step, the structure from step 1 underwent torsion angle dynamics at 20 K followed by simulated annealing in which the temperature was decreased from 20 to 1 K in ΔT = 1 K steps. 100 structures were generated in step 2, and the lowest energy structure was selected for further analysis. The structures were validated by the program PROCHECK (28). Molecular graphics were created using the program MOLMOL (29) or PyMOL (version 1.3).

Molecular Modeling of the CaM·L-selectin·ERM Complex

A model of this heterotrimer was built by overlapping L-selectin residues Arg356–Lys363 shared between the CaM·LSEL15 complex structure presented here and a pre-existing model of the L-selectin cytoplasmic tail bound to the N-terminal domain of moesin (also known as the FERM (band four-point one, ezrin, radixin, moesin homology) domain) and the C-terminal lobe of CaM (30). The overlay produced an ∼1-Å backbone root mean square deviation (RMSD) between the shared residues (supplemental Fig. S1). The resulting heterotrimeric complex was energy-minimized for steric clashes using discrete molecular dynamics in the program Chiron (31).

RESULTS

Identification of the L-selectin CaM Binding Site and Ca2+ Specificity of the Interaction

To characterize the interaction between L-selectin and CaM at the molecular level, the roles of Ca2+ as well as the juxta- and transmembrane regions of L-selectin were examined. ITC was used to determine binding affinities as well as other thermodynamic parameters for the interactions between both Ca2+-free and Ca2+-bound CaM and two peptides: one encompassing solely the cytoplasmic tail of L-selectin (LSELs) and the second the cytoplasmic tail plus a segment of L-selectin thought to reside in the transmembrane domain (LSELl) (Fig. 1A). Four different titrations were performed: LSELl or LSELs into Ca2+-CaM and LSELl or LSELs into apo-CaM (Fig. 1B). From these titrations, the requirement for Ca2+ as well as a portion of L-selectin predicted to be in the membrane-spanning region becomes apparent. The binding curve of LSELl with Ca2+-CaM is characterized by a two-step process, similar to that reported for other CaM-binding peptides (32, 33). The first, which describes the binding of the first peptide to CaM, has a dissociation constant (Kd) on the order of 10−9 m and is driven predominantly by entropic factors (Fig. 1C and supplemental Table S1). The second step, corresponding to the binding of a second LSELl peptide to Ca2+-CaM, has a Kd on the order of 10−6 m, indicating a significantly weaker affinity, and is an enthalpically favorable event. Interestingly, despite different energetic driving factors and affinities, both LSELl binding sites on Ca2+-CaM are insensitive to an increased salt concentration, suggesting that these interactions are predominantly hydrophobic and are not driven by charge-charge interactions (supplemental Table S1). The occurrence of two binding events is supported by surface plasmon resonance experiments (data not shown). The titration of LSELl into apo-CaM produced a complex endothermic binding curve with multiple LSELl peptides interacting with CaM. Unlike the titration with the Ca2+-bound protein, however, the number and identity of the thermodynamic interactions are not clear. Modeling of these data was largely unsuccessful, although a dissociation constant on the order of 10−6 m obtained for the first binding event is not unreasonable (data not shown). The results for LSELl are contrasted with those for LSELs. No significant amount of heat was released or absorbed from the titration of either Ca2+-bound or -free CaM with this peptide that represents solely the cytoplasmic tail of L-selectin.

A similar outcome was seen when the interactions of both Ca2+-bound and apo-CaM with the L-selectin peptides were examined through 15N HSQC titrations, a technique that provides information on ligand-induced global conformational shifts as well as chemical exchange. A 15N HSQC titration again points to two independent LSELl binding sites on Ca2+-CaM that differ significantly in affinity (supplemental Fig. S2A). Up until the 1:1 stoichiometric ratio, this titration is characterized by slow chemical exchange as the 1H(N) backbone resonances corresponding to free Ca2+-CaM disappear and those for complexed CaM appear. In contrast, the binding of the second LSELl peptide to Ca2+-CaM leads to broadening of the 1H(N) resonances often to the point of disappearance. This effect is characteristic of intermediate chemical exchange on the NMR time scale and indicates a significantly weaker equilibrium constant for this interaction. Because slow exchange typically corresponds to an intermolecular dissociation constant on the order of 10−7 m or less and intermediate exchange often occurs when Kd is ∼10−6 m, the type of chemical exchange observed for each of the binding events corresponds with the Ca2+-CaM·LSELl affinities obtained through calorimetry. Spectra characteristic of an intermolecular interaction in fast exchange on the NMR time scale were produced with the titration of LSELl into apo-CaM as well as LSELs into either Ca2+- or apo-CaM; the observed backbone 1H(N) resonances are an average of the free CaM and complexed CaM chemical shifts (supplemental Fig. S2, B–D). Fast chemical exchange is typically observed for intermolecular interactions with a dissociation constant on the order of 10−5 m or higher. Surface plasmon resonance experiments support an affinity of this magnitude for the binding of LSELs to Ca2+-CaM (data not shown).

Next, backbone CSPs were measured to characterize the regions of both apo- and Ca2+-CaM affected by the addition of either LSELl or LSELs to the sample. The CSPs were then plotted as a function of residue number for the various CaM and peptide combinations (Fig. 1D). In agreement with the ITC results, the degree and extent of the CSPs observed was the most significant for the complex between Ca2+-CaM and LSELl. This combination exhibited significant chemical shift changes throughout CaM with the greatest extent observed in the central linker, a trend seen in other Ca2+-CaM complexes (34). In contrast, the other combinations produced CSPs of a much smaller magnitude and located predominantly in the C-terminal lobe of CaM. Unlike the CSPs measured for Ca2+-CaM·LSELl, which represent the 1:1 complex, the CSPs for Ca2+-CaM·LSELs, apo-CaM·LSELl, and apo-CaM·LSELs were derived from peptide-saturated complexes.

Taken together, the biophysical data for this interaction highlight the roles of Ca2+ and a portion of L-selectin's predicted membrane-spanning region in creating a significant interaction between CaM and this protein. Although binding between CaM and L-selectin was detected in the absence of Ca2+ or with solely the cytoplasmic tail (using apo-CaM or LSELs, respectively) these interactions are in fast exchange on the NMR time scale, produce small and localized CSPs in the CaM backbone 1H(N) resonances, and either release/absorb very little heat as detected by ITC or suggest nonspecific binding. These observations are characteristic of significantly weaker interactions that are electrostatically driven. As such, we suspect that the interaction between Ca2+-CaM and LSELl is the functionally important form of this complex.

Structure Determination of Ca2+-CaM Complexed 1:1 with L-selectin

To understand the interaction between CaM and L-selectin at the molecular level, a solution NMR-based structure determination of Ca2+-CaM bound 1:1 with LSELl was carried out. Standard NMR-based structure determination of protein complexes proceeds via a series of experiments that first assign the resonances of CaM and the bound peptide and then independently determine the secondary and tertiary structures of CaM and the peptide through NOE-based distance restraints and finally solve the complex through the collection and analysis of intermolecular NOEs between CaM and the peptide. However, due to peak broadening observed even for the 1:1 complex between Ca2+-CaM and LSELl, this method was not viable. Instead, a reduced structure determination protocol was employed, in which the importance of methionine and the role that it plays in Ca2+-CaM·target interactions is exploited and combined with the use of backbone RDCs to solve the structure of the CaM·L-selectin complex (15).

A comparison of solved CaM·target peptide structures reveals that it is through variation in domain orientation and not in backbone conformation that CaM binds its numerous targets (23). Consequently, RDC analysis can be used to determine the orientation of the two lobes of CaM when bound to LSELl and provide a homologous starting model for the structure of CaM in the complex (18, 35). Because RDCs are a function of bond vector orientation in relation to the external magnetic field, they are particularly useful for orienting two domains of a protein with respect to each other (36). Here, the correlations between measured HN-N RDCs for CaM bound to LSELl and theoretical RDCs back-calculated from crystal structures deposited in the Protein Data Bank were determined (supplemental Table S2). The closest agreement obtained was to those back-calculated from the CaM·Ca(v)1.2 Ca2+ channel (Protein Data Bank code 2F3Y) (37). This published structure was subsequently used as the starting model for CaM in complex with L-selectin.

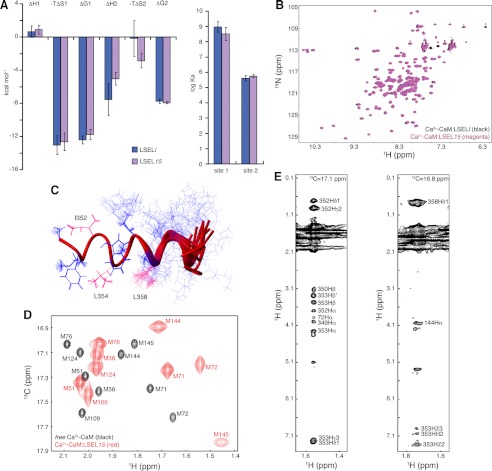

To facilitate the collection of NOE-based distance restraints required to determine the tertiary structure of the complex, the synthetic peptide employed was shortened from a 24-mer to a 15-mer. This peptide, LSEL15, bound to CaM in the same manner as LSELl (Fig. 2, A and B, and supplemental Table S1) (results not shown) and produced spectra with narrower line widths, easing the process of resonance assignment. In total, 189 non-degenerate intrapeptide NOEs provided the distance restraints for calculation of the bound LSEL15 structure by the automatic assignment and structure calculation program CYANA (version 2.0). The 20 lowest structures have a backbone RMSD of 0.71 Å (Fig. 2C). From the lowest energy structure, 171 distance restraints were supplied for the full complex structure calculation (Table 1).

FIGURE 2.

NMR-based structure determination of 1:1 Ca2+-CaM·L-selectin complex. A, bar graph comparing the determined thermodynamic parameters for the calorimetric titration of Ca2+-CaM with LSELl or LSEL15. Data are represented as mean ± S.E. (error bars) for three independent experiments. B, overlays of 15N HSQC spectra of Ca2+-CaM complexed 1:1 with LSELl and LSEL15. C, NOE-based solution structure of LSEL15 when bound to Ca2+-CaM. The final 20 structures generated by CYANA (version 2.0) are aligned over residues 350–356. LSEL15 is an α-helix from Phe350 to Arg356 in all 20 structures and from Phe350 to Lys362 in the lowest energy structure. The anchor residues of Ile352, Leu354, and Leu358 are indicated in hot pink. D, 13C HSQC spectrum of Ca2+-bound (1H/13C-methyl-Met)/2H/15N-labeled CaM either peptide-free or complexed 1:1 with LSEL15. Due to the selective labeling scheme, only the methyl groups of the CaM methionines are detected. Eight of the nine methionine amino acid residues of CaM line the hydrophobic binding pockets of CaM, and changes in both line width and chemical shift of the methyl group of these residues point to the involvement of both lobes in the interaction with LSEL15. E, representative strip plots from 13C-edited NOESY-HSQC spectra of the 1:1 complex of (1H/13C-methyl-Met)/2H/15N-labeled CaM and LSEL15. The intermolecular NOEs between the methyl groups of Met-72 (left) and Met-144 (right) and identified protons on LSEL15 are indicated. Also seen are intramethionine NOEs between the Hϵ and Hα protons.

TABLE 1.

Experimental restraints and structural statistics of the lowest energy structure of Ca2+-CaM·LSEL15

| Parameters | Values |

|---|---|

| No. of experimental restraints | |

| Distance restraints from NOEs | |

| CYANA-derived intrapeptide upper distance restraints | 171 |

| CaM intermethionine NOEs | 6 |

| Intermolecular NOEs | 69 |

| HN-N RDC restraints | 109 |

| Backbone dihedral angle restraints | |

| CaMa | 288 |

| LSEL15b | 28 |

| Hydrogen bonding restraints | |

| CaMc | 116 |

| LSEL15d | 6 |

| Ca2+ chelation restraints | 24 |

| Average RMSD values from experimental data | |

| Distance restraint violation (Å) | 0.082 |

| Dihedral angle restraint violation (degrees) | 2.341 |

| RDC restraint violation (Hz) | 0.092 |

| Average RMSD values from idealized covalent geometry | |

| Bonds (Å) | 0.003 |

| Angles (degrees) | 0.422 |

| Impropers (degrees) | 0.345 |

| Ramachandran analysis of Ca2+-CaM·LSEL15e | |

| Residues in favored regions (%) | 94.8 |

| Residues in additionally allowed regions (%) | 5.2 |

| Residues in generously allowed regions (%) | 0 |

| Residues in disallowed regions (%) | 0 |

a Predicted from TALOS (25).

b Obtained from the lowest-energy bound LSEL15 structure calculated by CYANA-2.0.

c Based on CSI-defined secondary structure.

d Based on secondary structural elements common to the 20 lowest energy structures of bound LSEL15 calculated by CYANA-2.0.

e Performed using PROCHECK on structure regions 6–144 and 350–362.

The standard experiments used to assign the key aliphatic side chain methyls and collect intermolecular NOEs (a NOESY-13C-1H-HSQC and its F1-13C,15N isotope-filtered version, respectively) produced ambiguous resonance assignments and difficulties in assigning NOE cross-peaks. Unambiguous intermolecular NOEs are required to tie the complex together, providing distance restraints as well as domain translational information not supplied by RDCs. To solve this problem, a labeling scheme analogous to that of methyl-labeling isoleucine, leucine, and valine against a perdeuterated background was employed (38). Using CaM 1H/13C-labeled on the methyl groups of methionine but otherwise isotopically 2H and 12C ((1H/13C-methyl-Met)/2H/15N-labeled CaM), the high number of methionine residues in CaM (9 of 148 amino acid residues) and their location in the hydrophobic pockets were exploited to collect intermolecular NOEs between CaM and the bound peptide (15, 39). Altogether, 69 intermolecular NOEs between CaM and LSEL15 as well as six intermethionine NOEs were measured (Fig. 2, D and E, and Table 1).

The solution structure of the 1:1 interaction between Ca2+-CaM and LSEL15 was calculated using a two-step, low temperature torsion angle simulated annealing protocol (15, 26). In this protocol, the RDC-selected homologous CaM starting structure was refined using backbone HN-N RDCs and experimentally determined dihedral angle restraints, peptide-specific CYANA-derived distance and dihedral angle restraints, hydrogen bonding restraints for both molecules, and intermolecular NOEs (Table 1). The 30 lowest energy structures calculated in this manner have a backbone and heavy atom RMSD in the folded regions of 0.318 and 0.378 Å, respectively.

Solution Structure of Ca2+-CaM Complexed 1:1 with the LSEL15 Peptide and Comparison with Other Complexes

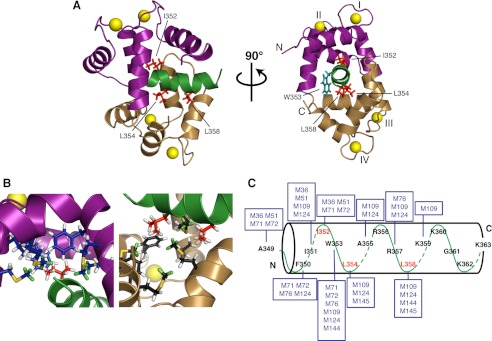

The lowest energy solution structure of the 1:1 complex of Ca2+-CaM·LSEL15 is presented in Fig. 3A. The bound peptide is α-helical over almost its entire length (Phe350–Lys362), retaining the conformation calculated by CYANA (Fig. 2C). The N- and C-terminal lobes of CaM interact with the N- and C-terminal portions of the LSEL15 peptide, respectively, to form a complex in parallel orientation relative to the bound peptide. The aliphatic side chain of LSEL15 residue Ile352 projects into the methionine-lined hydrophobic pocket of the N-lobe of CaM, anchoring the N-terminal portion of the peptide to this lobe of CaM (Fig. 3, B and C). In an analogous manner, the side chains of both Leu354 and Leu358 point into the hydrophobic pocket of the C-terminal lobe of CaM, anchoring the C-terminal portion of the peptide through a “double-anchor” motif (40). For all three key residues, a significant number of NOEs were collected between their side chains and the methionine probes that line the hydrophobic pockets of CaM. The basic residues downstream from Leu358 interact with the exit channel of the C-terminal lobe of CaM. This channel is more negatively charged than the entrance channel formed by the CaM N-terminal lobe; thus, the parallel orientation observed is energetically favorable because the more hydrophobic or more positively charged halves of the peptide interact with the corresponding lobes of CaM. The combination of hydrophobic and electrostatic interactions between CaM and LSEL15 probably explains the apparent insensitivity of this complex to increased salt concentration (supplemental Table S1).

FIGURE 3.

Structural basis for the 1:1 interaction of Ca2+-CaM with L-selectin. A, ribbon representation of the lowest energy structure of the complex. The N- and C-terminal lobes of CaM are shown in purple and gold, respectively, and the LSEL15 peptide is indicated in green. The side chains of LSEL15 amino acid residues Ile352, Leu354, and Leu358 are highlighted in red. Together, these three side chains anchor the LSEL15 peptide to CaM with a “1–3/7 motif.” The side chain of Trp353 is in teal. The four Ca2+ ions are indicated as yellow spheres. B, closer view of the interface between CaM and the anchoring amino acid side chains of LSEL15. Right, interaction of the CaM N-lobe with Ile352 of LSEL15; left, the CaM C-lobe with Leu354 and Leu358 of LSEL15. In each panel, the helices and side chain carbons are colored purple/navy, gold/black, or green/red for the N- or C-lobe of CaM or LSEL15, respectively. Methionine methyl group protons that serve as probes for intermolecular NOEs between CaM and LSEL15 are colored green. C, schematic showing the observed intermolecular NOEs between the methionine methyl groups of CaM (boxed) and the LSEL15 peptide. Key interacting residues Ile352, Leu354, and Leu358 of LSEL15 are indicated in red.

Due to the spacing of the peptide anchors, the LSEL15 peptide binds Ca2+-CaM with a “1–3/7” motif. Although this particular spacing is novel, the motif is a hybrid of the 1–3 and 1–7 anchor positions seen in the MARCKS and NMDA receptor Ca2+-CaM complexes, respectively (Protein Data Bank codes 1IWQ and 2HQW). Counterintuitively, the side chain of Trp353 does not seem to serve as an anchor residue for either lobe of CaM and instead resides between them near the central linker (Fig. 3A), a position supported by fluorescence spectroscopy studies using selenomethionine-substituted CaMs (results not shown) (41). In comparison with the canonical 1–14 spacing seen for CaM bound to the myosin light chain kinase peptides, this 1–3/7 anchor spacing is much tighter, the consequence of which is seen in the close proximity of the two lobes of CaM. If this proximity is measured as the distance between the centers of mass for each lobe, the LSEL15 complex is more compact not just compared with myosin light chain kinase or the other kinase complexes, but also more compact than the NMDA receptor or MARCKS complexes (19.7 Å versus 20.6 and 21.1 Å, respectively) (supplemental Table S3). The entire backbone RMSD of Ca2+-CaM·LSEL15 is quite large when compared with other known structures; however, on a domain by domain basis, this difference is much smaller, and the tertiary structure is in quite good agreement, reflecting the versatility of the flexible linker in accommodating widely different CaM-binding domains.

Molecular Model for the Simultaneous, Non-competitive Binding of CaM and Ezrin/Moesin FERM Domain to the Tail of L-selectin

In addition to and concurrent with CaM, members of the ERM family of membrane-cytoskeleton cross-linkers bind the cytoplasmic tail of L-selectin. By linking L-selectin's cytoplasmic tail with the actin cytoskeleton, the ERM family is thought to distribute L-selectin to the tips of microvilli, facilitating leukocyte tethering under flow, and play a role in phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate-induced shedding (42, 43). The binding sites for CaM and the FERM domain of ezrin/moesin are thought to overlap, and both in vitro and in vivo evidence suggests that FERM and CaM are able to bind to non-competing regions of the same tail, forming a 1:1:1 heterotrimeric complex in the unactivated cell (30). Due to the “tight quarters” in this juxtamembrane region, the compact nature of the CaM domain orientation in our 1:1 Ca2+-CaM·LSEL15 structure would help facilitate the binding of an ERM family member to L-selectin. Indeed, several C-terminal residues of LSEL15 remain exposed to the solvent, including Arg357 and Lys362, which have been identified as critical for the interaction with moesin-FERM (Fig. 4A) (42, 44).

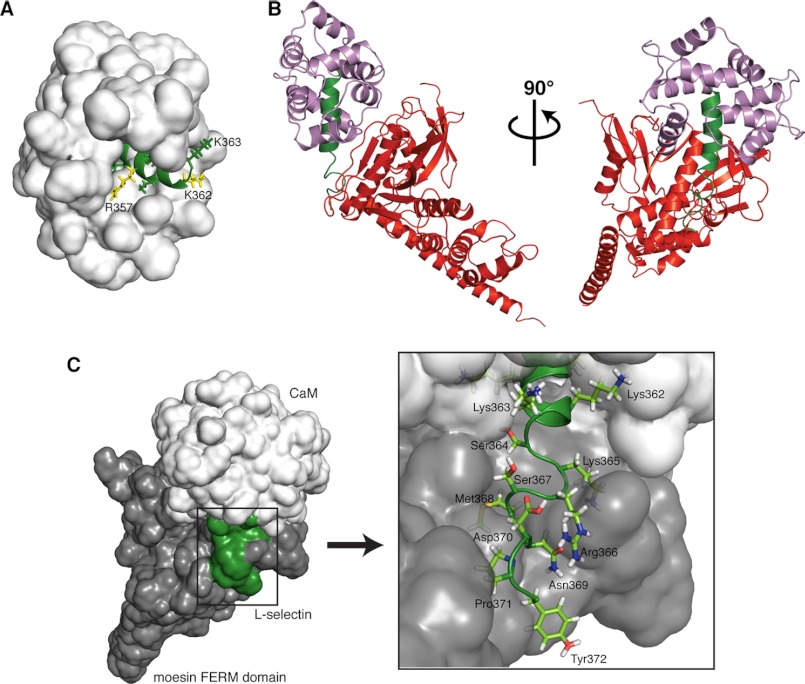

FIGURE 4.

Structural model of the CaM·L-selectin·ERM heterotrimeric complex. A, the close positioning of the two lobes of CaM when bound to LSEL15 enables the C-terminal residues of LSEL15 implicated in the interaction with FERM to be solvent-exposed. The solvent-accessible surface area of CaM is shown in a white surface representation; bound LSEL15 is shown as a green ribbon, and the solvent-exposed side chains of L-selectin are shown in green, with those thought to be involved in the interaction with FERM highlighted in yellow. B, heterotrimeric complex of CaM·L-selectin·ERM with the secondary structural elements colored as follows: CaM (purple), L-selectin (green), and moesin FERM (red). C, despite forming interactions with both CaM (white) and FERM (gray), a significant portion of the C-terminal region of L-selectin's tail (green) remains solvent-exposed. The solvent-accessible surface area of all three components is shown with atomistic detail of L-selectin's exposed C-terminal residues indicated (box).

Using our determined solution structure of the CaM·L-selectin interaction, we have been able to build upon an existing model of the heterotrimeric complex (30) (Fig. 4B and supplemental Fig. S1). Because the molecular model created by Killock et al. (30) had undergone extensive energy minimization and dynamics cycles, the atomic positions of moesin FERM and amino acid residues Ser364 to Tyr372 of L-selectin from this model were combined with those of CaM and L-selectin residues Ala349 to Lys363 from the CaM·LSEL15 complex and aligned using the L-selectin residues common to both structures (Arg356–Lys363) to orientate the individual components. The generated model produces a clearer picture of the heterotrimeric interaction because the structure of L-selectin bound to CaM as well as the positioning of CaM in relation to L-selectin is experimentally determined rather than modeled. Not only does this model provide a visual representation of how CaM and ERM could both bind non-competitively to the cytoplasmic tail of L-selectin, but because a significant amount of the C-terminal region of the tail remains solvent-exposed (Fig. 4C), it also provides structural plausibility for the binding of additional cytoplasmic partners, such as α-actinin and PKC isozymes. In the model, the C-terminal L-selectin amino acid residues that extend beyond those represented by the LSEL15 peptide and thus without an experimentally determined position (Ser364–Tyr372) are represented as a random coil, a secondary structure supported by NMR-based experiments using the bound LSELl peptide (results not shown).

Phosphorylation of the L-selectin Tail Does Not Directly Regulate the Interaction with CaM

It has been proposed that for L-selectin, as for many other proteins, the PKC phosphorylation and CaM-binding sites overlap and that phosphorylation of serine residues in L-selectin's cytoplasmic tail by PKC leads to disassociation of CaM and thus shedding of the extracellular domains (11, 12). GPCR stimulation activates PKC pathways, and in phorbol ester- or chemoattractant-activated leukocytes, PKC isozymes have been found interacting with the L-selectin tail, and this sequence is phosphorylated on evolutionarily conserved serine residues (Ser364 or Ser367) (Fig. 5A) (5). However, binding studies performed through both ITC and 15N HSQC titrations indicate that phosphorylation on these residues does not impede the ability of CaM to bind L-selectin (Fig. 5B, supplemental Fig. S3, and supplemental Table S1). This observed insensitivity to phosphorylation agrees with our presented structural data on the 1:1 CaM·L-selectin complex because both Ser364 and Ser367 are outside of L-selectin's CaM-binding domain. Instead, our model of the heterotrimeric complex suggests that phosphorylation could affect the interaction between L-selectin and the N-terminal domain of ezrin/moesin. Both Ser364 and Ser367 are close to and involved in the interaction with moesin (Fig. 5C), and phosphorylation on either residue could lead to a change in the ability of ezrin/moesin to bind L-selectin and indirectly influence CaM binding.

FIGURE 5.

Phosphorylation of the L-selectin tail does not induce CaM dissociation. A, sequence alignment of the membrane-proximal, transmembrane, and cytoplasmic domains of mammalian L-selectins performed using ClustalW (74). The predicted transmembrane domain, region encompassed by the LSEL15 peptide, and predicated PKC phosphorylation sites are delineated by a black box, filled green box, and filled yellow boxes, respectively. *, LSEL15 anchor residues for the interaction with Ca2+-CaM. B, thermodynamic parameters of the calorimetric titration of Ca2+-CaM with LSELl, LSELpSer364, or LSELpSer367 displayed as bars. Data are represented as mean ± S.E. (error bars) for three independent experiments. Apparent is the insensitivity of CaM to the phosphorylation state of L-selectin. C, close-up view of the interface of L-selectin and moesin FERM with the same secondary structure coloring scheme as in Fig. 4B. The side chains of L-selectin residues Ser364 and Ser367 are indicated in yellow, whereas side chains of moesin residues at the interface are indicated in light blue. Both serines are close to the binding interface, in particular Ser364, which appears to interact with Ile248 of moesin.

Structural Characterization of the 1:2 Ca2+-CaM·LSEL15 Interaction

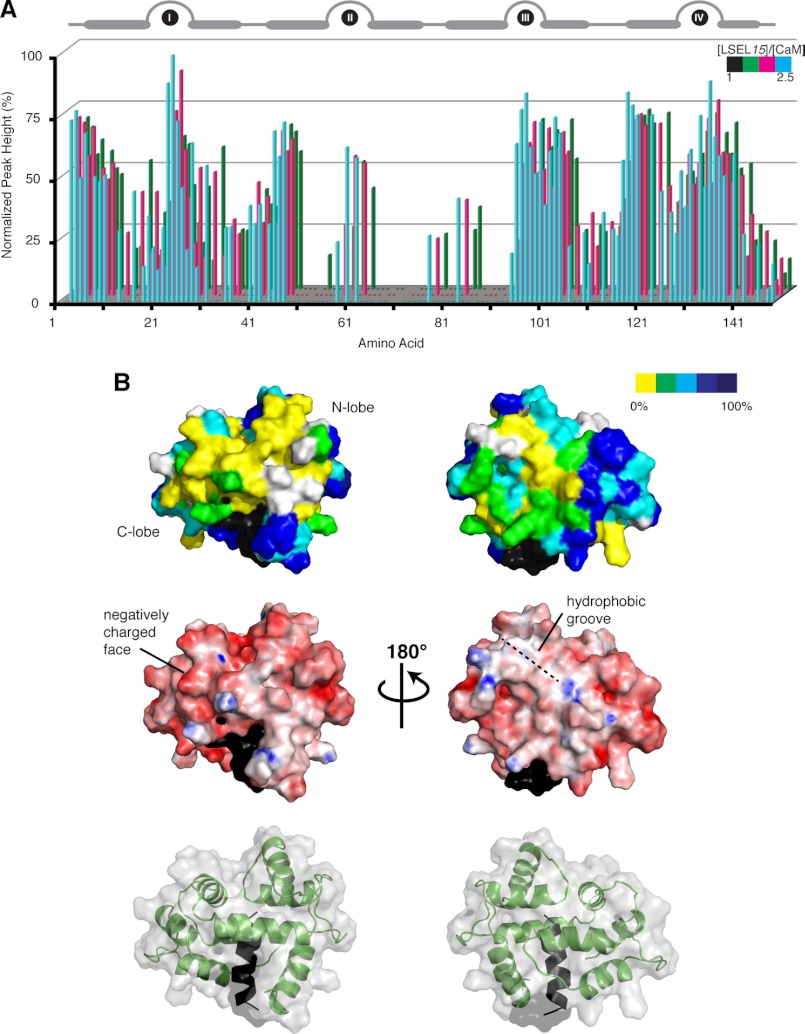

Due to significant peak broadening observed upon the addition of a second molar equivalent of LSELl or LSEL15 to Ca2+-CaM (supplemental Fig. S2), the 1:2 complex is not amenable to NMR-based structure determination. However, on the basis of observed signal broadening in 15N HSQC spectra, we have determined regions of Ca2+-CaM affected by the interaction with the second LSELl/15 peptide. The broadening of backbone cross-peak signals in 15N HSQC spectra of peptide-saturated Ca2+-CaM (a 1:2.5 molar ratio) is not uniform, and analysis of normalized peak height (peak height as it compares to that in the 1:1 spectra) can quantify the degree of signal loss on a per residue basis (Fig. 6A and supplemental Fig. S2A). Many 15N HSQC cross-peaks originating from backbone resonances in the second and third EF-hands as well as the central linker are broadened to the extent that they have disappeared (0% normalized peak height). As mentioned earlier, this observation is characteristic of an intermediate exchange regime and suggests that these residues are participating in a medium strength interaction. When the degree of signal loss is mapped onto the 1:1 structure of Ca2+-CaM·LSEL15, those residues most affected by the binding of the second peptide suggest a secondary interface on the top of the CaM molecule away from the Ca2+-binding EF-loops (Fig. 6B). This secondary interface is made up of a negatively charged face on the CaM C-lobe and a hydrophobic groove found on the back of the N-lobe. It is conceivable that the more hydrophobic portion of LSEL15 or LSELl could bind to the groove while the positively charge sequences of these peptides bind the negative face. Although this second binding site involves both lobes of CaM, it is distinct from the hydrophobic pockets that create the “classical” Ca2+-CaM binding site through which the first LSELl/15 peptide interacts.

FIGURE 6.

Mapping the binding interface of the second LSEL15 peptide on the 1:1 Ca2+-CaM·LSEL15 complex. A, NMR titration analysis of unlabeled LSEL15 binding to 15N-labeled Ca2+-CaM. 15N HSQC spectra of 15N-labeled CaM were collected at titration steps corresponding to [LSEL15]/[CaM] molar ratios of 1 (black, 100% peak height not shown), 1.5 (green), 2 (magenta), and 2.5 (cyan). Normalized peak heights of 15N-labeled CaM from the HSQC spectra are plotted against CaM residues. The position of the four EF-hands of CaM is indicated at the top of the diagram. B, surface representations of the 1:1 Ca2+-CaM·LSEL15 complex. Top, residues are colored according to their height in 15N HSQC spectra of the 2.5:1 [LSEL15]/[CaM] molar ratio, normalized against peak height in spectra of the 1:1 molar ratio. Yellow, missing; green, <30%; cyan, between 30 and 60%; blue, between 60 and 90%; navy, >90%. Residues not included in the analysis due to peak overlap are colored white, whereas those that correspond to that of the first LSEL15 peptide are colored black. The addition of a second LSEL15 peptide maps predominantly to the “top” of the CaM molecule. Middle, charged surface structure highlighting the acidic and basic side chains of CaM. The negatively charged face and hydrophobic groove thought to support the binding of the second LSEL15 peptide are shown. Bottom, ribbon structure displayed together with surface structure indicating the orientation of the 1:1 Ca2+-CaM·LSEL15 complex presented in the other two panels.

DISCUSSION

The presented study examines at a biophysical and structural level the interaction between CaM and L-selectin. We have determined the solution structure of Ca2+-CaM bound 1:1 to a synthetic peptide representing the cytoplasmic/transmembrane domain of L-selectin. Due to broad and missing signals, particularly from critical side chain methyl groups, initial attempts to determine a high resolution structure of this complex through a traditional NOE-based strategy were unsuccessful. Therefore, a novel structure determination protocol was employed in which backbone HN-N RDCs were used to determine the domain orientation of the two lobes of CaM, and intermolecular NOEs between the CaM methionine methyl groups and the protonated peptide defined how the orientated domains bind the peptide. This structure explains the requirement for both Ca2+ and the putative transmembrane region of L-selectin in forming a strong interaction between these two proteins, as suggested by both ITC and CSPs (Fig. 1). It is through the hydrophobic patches exposed in the Ca2+-replete state that the two lobes of CaM bind the hydrophobic side chain anchors of L-selectin (Fig. 3). Two of these anchors, Ile352 and Leu354, are located in the predicted membrane-spanning region of L-selectin (the third, Leu358, is in the established cytoplasmic tail), indicating that CaM must either pull this region out of the membrane, perturb the membrane bilayer structure, or do a combination of both to bind L-selectin (discussed below).

At the physiological level, the requirement for Ca2+ is a bit unexpected. The interaction between CaM and L-selectin is thought to exist in resting leukocytes, a state in which the cytoplasmic Ca2+ concentration is 10−7 m and CaM is in either an apo or partially Ca2+-bound form. However, both the absence of the coimmunoprecipitation of CaM with L-selectin in the presence of the Ca2+-chelator EDTA (12) and the directly induced shedding of L-selectin from both neutrophils and lymphocytes upon the addition of pharmacological Ca2+-CaM inhibitors (11) point to the in vivo Ca2+ requirement of this interaction. The contemporary belief in spatial/temporal aspects of Ca2+ signaling, conceptualized by microdomains, could help to explain this discrepancy. As Ca2+ enters the cytoplasm, it produces a local plume, a restricted domain of increased Ca2+ concentration that on its own or in combination to produce larger microdomains can regulate specific cellular processes in different regions of the cell (45). The time scale of the Ca2+ influx is also critical because brief transients lead to a more restricted increase influencing effectors solely in the nearby environment, contrasting with the global concentration change and universal effector activation that results from a sustained influx. The engagement of ligands by L-selectin's lectin domain has been shown to cause an internal store-derived increase in cytosolic Ca2+ through a pathway independent of heterotrimeric G-proteins (46). However, the magnitude and duration of this Ca2+ influx is smaller and shorter than that seen with GPCR engagement. The Ca2+ “puffs” produced could lead to a concentration high enough to allow Ca2+-CaM to bind L-selectin but localized and of a duration short enough to distinguish the effects from GPCR- or immunoreceptor-based cell activation characterized by a global Ca2+ increase that lasts for hours and triggers L-selectin ectodomain shedding (47, 48). Furthermore, CaM, like other members of the EF-hand superfamily, exhibits a strong increase in affinity for Ca2+ in the presence of a target protein (49). Therefore, it is reasonable to expect that in the presence of L-selectin, a significant portion of CaM may be Ca2+-bound even at 100 nm Ca2+, interacting with L-selectin in its Ca2+-bound state in the resting cell.

The solution structure highlights the role of L-selectin's juxtamembrane region in the interaction between L-selectin and CaM; the C-lobe of CaM binds predominantly to this sequence that includes the anchor residue Leu358. This finding is supported by both in vitro and in vivo experiments. Coimmunoprecipitation studies with either mapping antibodies or truncation mutants indicate that the eight C-terminal amino acids of the tail are not required for binding (11, 12), a fact mirrored in the similar CaM-binding abilities of the LSELl and LSEL15 peptides (Fig. 2 and supplemental Table S1). In vitro peptide binding array and in vivo mutant-based shedding studies as well as L-selectin splice variants found in mice further define cytoplasmic amino acid residues 356RRLKKG361 as critical to CaM binding (Fig. 5A) (12, 13, 50, 51). Coimmunoprecipitation experiments on transfected L-selectin mutants support the role of Leu358 and Lys359 in anchoring the C-lobe of CaM and forming favorable interactions with this lobe's negatively charged exit channel, respectively (11).

Due to large degrees of error associated with the derived constants and related to the small magnitude of the observed enthalpy change (the data are significantly scattered off the smooth theoretical curve), we did not report curve fitting of the ITC data for the binding of LSELs to CaM (Fig. 1B); however, an affinity on the order of 10−5 m was obtained using surface plasmon resonance (data not shown). A recent publication by Deng et al. reported a dissociation constant on the order of 10−6 m for the interaction between CaM and the cytoplasmic tail of L-selectin (52). This value, similar for both Ca2+- and apo-CaM, was determined using ITC and a peptide representing the cytoplasmic domain plus one amino acid of the putative transmembrane helix (L-selectin residues Ala355–Tyr372). Both the peptide studied by Deng et al. (52) and LSELs exhibit an exothermic enthalpy change of similar magnitude upon binding CaM; however, differences in chemical exchange behavior suggest that the peptide studied by Deng et al. binds CaM with higher affinity than our peptide LSELs; the binding between LSELs and CaM occurs in fast chemical exchange on the NMR time scale (supplemental Fig. S2), whereas the peptide studied by Deng et al. (52) bound in intermediate exchange. The addition of hydrophobic Ala355 to the cytoplasmic domain peptide most likely explains the difference in affinity and exchange behavior of the two peptides.

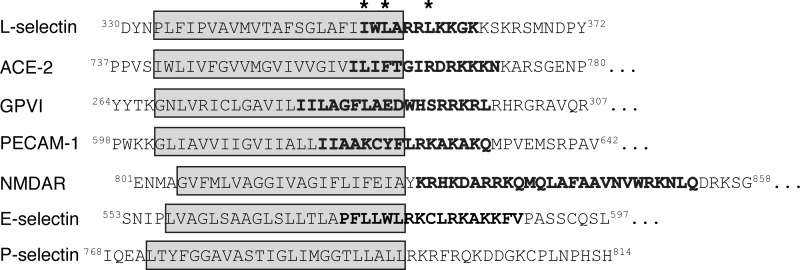

Despite significant research focused on the ability of L-selectin's cytoplasmic juxtamembrane region to bind CaM, the predicted membrane-spanning region has largely been ignored, and yet the presented study provides structural evidence that this sequence is critical for the interaction of these two proteins. Amino acid residues Ile352 and Leu354 that serve to anchor the N- and C-lobes of CaM originate in the first turn of the proposed transmembrane helix, and the neighboring bulky, hydrophobic amino acid residues found in this sequence of L-selectin form favorable interactions with the hydrophobic patches exposed in Ca2+-CaM. It is likely that these hydrophobic patches create an environment of characteristics similar to those found in the membrane, a fact highlighted by the lipid binding abilities of CaM (23). In vitro support for this structure is provided by Deng et al. (52), who observed FRET between a fluorescence probe attached to CaM and Trp353 when a peptide representing the external cleavage site, transmembrane helix, and cytoplasmic domain of L-selectin was reconstituted in a phosphatidylcholine bilayer. The interaction of CaM with a sequence predicted to extend by ∼6 amino acids into L-selectin's putative membrane-spanning region is not a unique occurrence. Ca2+- and integrin-binding protein 1 binds the cytoplasmic tail of the αIIb subunit of the platelet integrin αIIbβ3 through a sequence both juxtamembrane to and extending by six amino acids into the predicted membrane-spanning region (53–58). Furthermore, bioinformatic analysis presented here indicates that several other transmembrane receptors down-regulated through Ca2+/CaM-dependent ectodomain shedding have CaM-binding motifs that extend into the transmembrane domain (Fig. 7) (59–61). This suggests a common mode of CaM-mediated regulation that, to date, has yet to be studied in vivo.

FIGURE 7.

Other transmembrane receptors down-regulated through Ca2+-dependent ectodomain shedding have CaM-binding motifs extending into the transmembrane domain. Analysis of L-selectin, angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE-2), platelet glycoprotein VI (GPVI), and platelet endothelial cell adhesion molecule 1 (PECAM-1) reveals the presence of CaM binding motifs proximal to and extending into the predicted membrane-spanning region (see the Cellular Calcium Information Server Web site) (75, 76). In contrast, the C0 CaM-binding domain from the NR1 subunit of N-methyl-d-aspartate receptor is located solely in the cytoplasmic domain. Like L-selectin, the cytoplasmic domain of E-selectin contains a putative CaM-binding domain, but whether or not CaM associates with this molecule is not well defined. P-selectin does not contain a putative CaM-binding domain. For each sequence, the transmembrane domain is boxed in gray, and the high scoring predicted CaM-binding region is indicated in boldface type. *, LSEL15 anchor residues for the interaction with Ca2+-CaM. Interestingly, ACE-2 could bind CaM with the same 1–3/7 spacing of L-selectin through amino acid residues Ile759, Ile761, and Ile765.

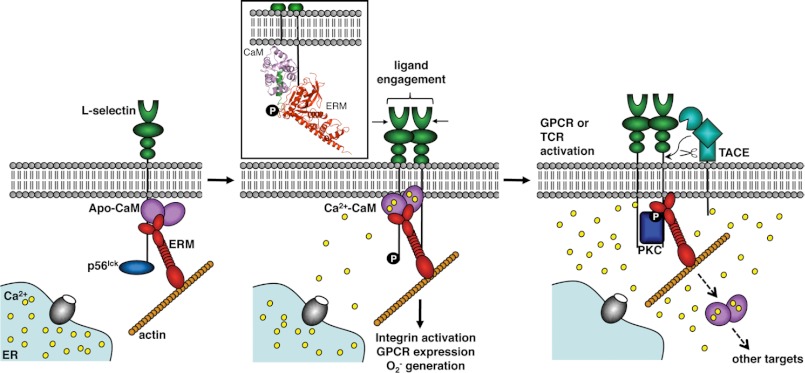

The CaM·L-selectin solution structure provides insight into a mechanism through which CaM regulates L-selectin ectodomain shedding. The interaction between the C-lobe of CaM and the cytoplasmic tail is driven through electrostatic forces, as suggested by the ITC and NMR titration data and by the fact that both apo- and Ca2+-CaM bind this region (Fig. 1D) (11, 30, 52). CaM would be electrostatically attracted to this part of L-selectin dangling down from the plasma membrane, and in the Ca2+-bound state, it would bind both the positive charges and Leu358 found in the juxtamembrane region. The importance of this event is seen by the fact that CaM does not coimmunoprecipitate with L-selectin 358LKK360/358EEE360 cytoplasmic or Arg356 truncation mutants (12). Once bound, due to the dynamic nature of the lipid membrane, CaM would “sense” anchor residues Ile352 and Leu354 present in the first helical turn of L-selectin's proposed membrane-spanning region. By binding these residues and their neighboring hydrophobic amino acids, CaM could effect a conformational change on the extracellular side of the membrane, preventing proteolytic cleavage. Upon cell activation, CaM disassociation would release this portion of L-selectin enacting a structural rearrangement, exposing the TACE cleavage site (Fig. 8).

FIGURE 8.

Schematic of CaM-regulated L-selectin ectodomain shedding. Pictured are suspected binding partners of the cytoplasmic tail of L-selectin in both the resting and activated leukocyte cell. In the resting cell, apo-CaM binds to the juxtamembrane region of L-selectin, a member of the ERM family connects L-selectin to the actin cytoskeleton, and p56lck, an Src-tyrosine kinase, associates with the C-terminal end of the tail. Ligand engagement by L-selectin's lectin-binding domain induces clustering of the receptor, phosphorylation of Tyr372 by p56lck, and the release of Ca2+ “puffs” from internal stores. The local increase in Ca2+ concentration enables CaM to bind L-selectin's anchor residues found both in the juxtamembrane region (Leu358) and in the first turn of the proposed membrane-spanning domain (Ile352 and Leu354). By potentially pulling this region out of the membrane, this binding interaction enacts a conformation change on the extracellular side of the plasma membrane that prevents the TACE protease from accessing the cleavage site. In the activated cell, a sustained, global increase in cytoplasmic Ca2+ concentration leads to CaM dissociation for other targets, such as calcineurin or the CaM-kinases, an act that releases the tail and exposes the cleavage site on the extracellular side of the membrane. Members of the ERM family continue to connect L-selectin to the actin cytoskeleton in the activated cell, potentially facilitating the co-localization of L-selectin with TACE to the cell's uropod. L-selectin is also phosphorylated by PKC isozymes, which may affect interaction with the ERM family or enable the interaction of additional binding partners.

This inside-out signaling hypothesis is supported by both in vivo and in vitro evidence. First, the sequence of L-selectin's transmembrane domain and juxtamembrane region is conserved throughout evolution (Fig. 5A). Second, considerably less CaM is associated with the 6-kDa trunk of L-selectin retained in the membrane following cleavage, pointing to its dissociation as a regulatory mechanism (12). Third, cytoplasmic mutations that abrogate the interaction with CaM affect the binding of an antibody against L-selectin's extracellular membrane-proximal cleavage site (11). This antibody can bind when CaM is bound to the cytoplasmic tail, suggesting that interacting partners of the cytoplasmic portion of L-selectin affect the conformation of its extracellular sequence. Finally, studies on L-selectin's membrane-proximal cut site point to the relaxed sequence specificity but length and conformational requirement of the TACE protease because both truncations as well as proline substitutions prevented proteolysis (51). It appears that a membrane-proximal stalk of sufficient length is required to permit TACE access to the substrate, and the binding of CaM to the cytoplasmic tail could cause a conformational change on the extracellular side of the membrane that shortens the amount of stalk available, preventing cleavage.

A key unanswered component of this proposed mechanism is the cause of CaM dissociation from the cytoplasmic tail of L-selectin. Our results suggest that the cause is neither a Ca2+-induced conformational change in CaM nor, as has been widely speculated, phosphorylation of serine residues found in the cytoplasmic tail of L-selectin (Fig. 5, supplemental Fig. S3, and supplemental Table S1). Although ITC experiments indicate that L-selectin binds Ca2+-CaM with an initial dissociation constant on the order of 10−9 m (supplemental Table S1), it is possible that the in vivo affinity is not as high due to other energetic considerations, such as potential membrane interactions and the presence of other proteins bound concurrently to the cytoplasmic tail. As a result, the sustained Ca2+ influx and resulting global concentration increase mediated by CRAC (calcium release-activated calcium) channels upon GPCR or immunoreceptor engagement may expose more abundant and higher affinity CaM binding sites, such as calcineurin and the CaM kinases, two families of proteins up-regulated upon cell activation. Alternatively, the induced close proximity of phosphatidylserine or phosphorylated phosphatidylinositols has been suggested to play a role in CaM disassociation (52).

Treatment of leukocytes with lineage-specific activating stimuli induces PKC-dependent phosphorylation of Ser364 and/or Ser367 in the cytoplasmic domain of L-selectin. The result of this phosphorylation is 2-fold. First, an increase in L-selectin's ligand binding activity is observed (62, 63). This response is immediate and preludes the ectodomain shedding of L-selectin that occurs minutes following cell activation. Second, mutagenesis-based studies have shown serine phosphorylation to be key to cell activation-linked ectodomain shedding (43). The introduction of one or two highly negatively charged groups significantly alters the local surface characteristics of that region of the protein, typically inducing or preventing intra- or intermolecular interactions. Because serine phosphorylation does not directly affect the ability of CaM to bind L-selectin (Fig. 5B, supplemental Fig. S3, and supplemental Table S1), it probably plays a role in the regulation of L-selectin's other cytoplasmic binding partners. Through both in vitro binding experiments and in vivo fluorescence lifetime imaging microscopy, members of the ERM family of cytoskeleton-membrane cross-linkers have been found to co-localize with CaM to the cytoplasmic domain of L-selectin (Fig. 4B) (30) and play a significant role in both tethering of the adhesion receptor to its ligands as well as in PKC-dependent shedding (64, 65). The side chains of both Ser364 and Ser367 (although to a lesser extent) are at the interface of the FERM domain of ezrin/moesin and L-selectin, and it is likely that their phosphorylation would affect this binding interaction (Figs. 4C and 5C). PKC-dependent phosphorylation could mediate the exchange of ezrin for moesin once the cell is activated (of particular importance if their roles do not overlap), induce a conformational rearrangement in the CaM·L-selectin·ERM heterotrimeric complex triggering CaM dissociation, or affect the binding of additional partners to the cytoplasmic domain of L-selectin. Whether or not CaM must dissociate for phosphorylation to occur remains to be determined.

A second, weaker binding site on CaM was observed for L-selectin (Figs. 1 and 6). This site maps to the “top” of the CaM molecule and could play a role in the clustering of L-selectin observed during leukocyte rolling in vivo or following triggering by antibodies or glycomimetics in vitro (66). By linking the cytoplasmic tails of two L-selectin receptors in cis, CaM could help to create a signaling platform that leads from the phosphorylation of L-selectin amino acid residue Tyr372 by the Src-tyrosine kinase p56lck to the activation of Ras signaling pathways and the production of O2˙̄ (30, 67). This clustering pathway occurs prior to L-selectin ectodomain shedding in response to cell activation (6) and is thought to promote outside-in signals that lead to integrin activation and chemokine receptor activation and eventually leukocyte arrest.

L-selectin's rapid ectodomain shedding in response to cell activation is an anti-adhesive process that has an immediate influence on the accumulation of leukocytes along the vasculature wall and is required for neutrophil transendothelial migration into inflamed tissue (68, 69). Furthermore, shedding prevents antigen-activated T-cells from re-entering peripheral lymph nodes (70), and the released domains hinder leukocyte recruitment by reducing ligand availability, thus diminishing inflammation (71). Underscoring the physiological consequences of shedding, there are numerous clinical settings in which this phenomenon may either serve as a protective feedback mechanism or exacerbate existing pathologies (72, 73). By better understanding the cellular and molecular mechanisms of this process, including the role of CaM in activation-induced cleavage, it may be possible to produce therapies that manipulate shedding of the extracellular domains of L-selectin. The NMR solution structure presented here provides the first molecular details for a mechanism through which CaM negatively regulates the shedding of the extracellular domains of L-selectin. Furthermore, it highlights the role of calcium-signaling pathways in the observed shedding response to GPCR- or immunoreceptor-based cell activation.

Acknowledgments

We thank Deane D. McIntyre for the synthesis of (1H-α,ϵ-13C-ϵ-2H-labeled methionine) as well as for tireless spectrometer maintenance.

This work was supported by an operating grant from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research.

This article contains supplemental Figs. S1–S3 and Tables S1–S3.

The atomic coordinates and structure factors (code 2LGF) have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank, Research Collaboratory for Structural Bioinformatics, Rutgers University, New Brunswick, NJ (http://www.rcsb.org/).

Resonance assignments for the bound peptide as well as calmodulin have been deposited in the BMRB database under accession number BMRB-17807.

- ERM

- ezrin/radixin/moesin

- CaM

- calmodulin

- CSP

- chemical shift perturbation

- GPCR

- G-protein-coupled receptor

- HSQC

- heteronuclear single quantum coherence

- ITC

- isothermal titration calorimetry

- RDC

- residual dipolar coupling

- RMSD

- root mean square deviation

- TACE

- tumor necrosis factor α-converting enzyme

- BisTris

- 2-[bis(2-hydroxyethyl)amino]-2-(hydroxymethyl)propane-1,3-diol

- MARCKS

- myristoylated alanine-rich C kinase substrate.

REFERENCES

- 1. Ley K., Kansas G. S. (2004) Selectins in T-cell recruitment to non-lymphoid tissues and sites of inflammation. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 4, 325–335 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Niggli V. (2003) Signaling to migration in neutrophils. Importance of localized pathways. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 35, 1619–1638 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ley K., Laudanna C., Cybulsky M. I., Nourshargh S. (2007) Getting to the site of inflammation. The leukocyte adhesion cascade updated. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 7, 678–689 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ivetic A., Ridley A. J. (2004) The telling tail of L-selectin. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 32, 1118–1121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Wedepohl S., Beceren-Braun F., Riese S., Buscher K., Enders S., Bernhard G., Kilian K., Blanchard V., Dernedde J., Tauber R. (2012) L-selectin. A dynamic regulator of leukocyte migration. Eur. J. Cell Biol. 91, 257–264 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Xu T., Chen L., Shang X., Cui L., Luo J., Chen C., Ba X., Zeng X. (2008) Critical role of Lck in L-selectin signaling induced by sulfatide engagement. J. Leukoc. Biol. 84, 1192–1201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Smalley D. M., Ley K. (2005) L-selectin. Mechanisms and physiological significance of ectodomain cleavage. J. Cell Mol. Med. 9, 255–266 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Peschon J. J., Slack J. L., Reddy P., Stocking K. L., Sunnarborg S. W., Lee D. C., Russell W. E., Castner B. J., Johnson R. S., Fitzner J. N., Boyce R. W., Nelson N., Kozlosky C. J., Wolfson M. F., Rauch C. T., Cerretti D. P., Paxton R. J., March C. J., Black R. A. (1998) An essential role for ectodomain shedding in mammalian development. Science 282, 1281–1284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Chin D., Means A. R. (2000) Calmodulin. A prototypical calcium sensor. Trends Cell Biol. 10, 322–328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Yamniuk A. P., Vogel H. J. (2004) Calmodulin's flexibility allows for promiscuity in its interactions with target proteins and peptides. Mol. Biotechnol. 27, 33–57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kahn J., Walcheck B., Migaki G. I., Jutila M. A., Kishimoto T. K. (1998) Calmodulin regulates L-selectin adhesion molecule expression and function through a protease-dependent mechanism. Cell 92, 809–818 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Matala E., Alexander S. R., Kishimoto T. K., Walcheck B. (2001) The cytoplasmic domain of L-selectin participates in regulating L-selectin endoproteolysis. J. Immunol. 167, 1617–1623 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Chen A., Engel P., Tedder T. F. (1995) Structural requirements regulate endoproteolytic release of the L-selectin (CD62L) adhesion receptor from the cell surface of leukocytes. J. Exp. Med. 182, 519–530 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Migaki G. I., Kahn J., Kishimoto T. K. (1995) Mutational analysis of the membrane-proximal cleavage site of L-selectin. Relaxed sequence specificity surrounding the cleavage site. J. Exp. Med. 182, 549–557 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Gifford J. L., Ishida H., Vogel H. J. (2011) Fast methionine-based solution structure determination of calcium-calmodulin complexes. J. Biomol. NMR 50, 71–81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bax A., Delaglio F., Grzesiek S., Vuister G. W. (1994) Resonance assignment of methionine methyl groups and χ3 angular information from long-range proton-carbon and carbon-carbon J correlation in a calmodulin-peptide complex. J. Biomol. NMR 4, 787–797 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ottiger M., Delaglio F., Bax A. (1998) Measurement of J and dipolar couplings from simplified two-dimensional NMR spectra. J. Magn. Reson. 131, 373–378 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Mal T. K., Skrynnikov N. R., Yap K. L., Kay L. E., Ikura M. (2002) Detecting protein kinase recognition modes of calmodulin by residual dipolar couplings in solution NMR. Biochemistry 41, 12899–12906 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Delaglio F., Grzesiek S., Vuister G. W., Zhu G., Pfeifer J., Bax A. (1995) NMRPipe. A multidimensional spectral processing system based on UNIX pipes. J. Biomol. NMR 6, 277–293 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Johnson B. A., Blevins R. A. (1994) NMR View. A computer program for the visualization and analysis of NMR data. J. Biomol. NMR 4, 603–614 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Grzesiek S., Bax A., Clore G. M., Gronenborn A. M., Hu J. S., Kaufman J., Palmer I., Stahl S. J., Wingfield P. T. (1996) The solution structure of HIV-1 Nef reveals an unexpected fold and permits delineation of the binding surface for the SH3 domain of Hck tyrosine protein kinase. Nat. Struct. Biol. 3, 340–345 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Zweckstetter M., Bax A. (2000) Prediction of sterically induced alignment in a dilute liquid crystalline phase. Aid to protein structure determination by NMR. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 122, 3791–3792 [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ishida H., Vogel H. J. (2006) Protein-peptide interaction studies demonstrate the versatility of calmodulin target protein binding. Protein Pept. Lett. 13, 455–465 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Guntert P. (2003) Automated NMR protein structure calculation. Prog. Nucl. Magn. Reson. Spectrosc. 43, 105–125 [Google Scholar]

- 25. Cornilescu G., Delaglio F., Bax A. (1999) Protein backbone angle restraints from searching a database for chemical shift and sequence homology. J. Biomol. NMR 13, 289–302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Chou J. J., Li S., Bax A. (2000) Study of conformational rearrangement and refinement of structural homology models by the use of heteronuclear dipolar couplings. J. Biomol. NMR 18, 217–227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Huang H., Ishida H., Yamniuk A. P., Vogel H. J. (2011) Solution structures of Ca2+-CIB1 and Mg2+-CIB1 and their interactions with the platelet integrin αIIb cytoplasmic domain. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 17181–17192 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Morris A. L., MacArthur M. W., Hutchinson E. G., Thornton J. M. (1992) Stereochemical quality of protein structure coordinates. Proteins 12, 345–364 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Koradi R., Billeter M., Wüthrich K. (1996) MOLMOL. A program for display and analysis of macromolecular structures. J. Mol. Graph. 14, 51–55, 29–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Killock D. J., Parsons M., Zarrouk M., Ameer-Beg S. M., Ridley A. J., Haskard D. O., Zvelebil M., Ivetic A. (2009) In vitro and in vivo characterization of molecular interactions between calmodulin, ezrin/radixin/moesin, and L-selectin. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 8833–8845 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Ramachandran S., Kota P., Ding F., Dokholyan N. V. (2011) Automated minimization of steric clashes in protein structures. Proteins 79, 261–270 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Yamniuk A. P., Burling H., Vogel H. J. (2009) Thermodynamic characterization of the interactions between the immunoregulatory proteins osteopontin and lactoferrin. Mol. Immunol. 46, 2395–2402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Rainaldi M., Yamniuk A. P., Murase T., Vogel H. J. (2007) Calcium-dependent and -independent binding of soybean calmodulin isoforms to the calmodulin binding domain of tobacco MAPK phosphatase-1. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 6031–6042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Ikura M., Kay L. E., Krinks M., Bax A. (1991) Triple-resonance multidimensional NMR study of calmodulin complexed with the binding domain of skeletal muscle myosin light-chain kinase. Indication of a conformational change in the central helix. Biochemistry 30, 5498–5504 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Contessa G. M., Orsale M., Melino S., Torre V., Paci M., Desideri A., Cicero D. O. (2005) Structure of calmodulin complexed with an olfactory CNG channel fragment and role of the central linker. Residual dipolar couplings to evaluate calmodulin binding modes outside the kinase family. J. Biomol. NMR 31, 185–199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Lipsitz R. S., Tjandra N. (2004) Residual dipolar couplings in NMR structure analysis. Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biomol. Struct. 33, 387–413 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Fallon J. L., Halling D. B., Hamilton S. L., Quiocho F. A. (2005). Structure of calmodulin bound to the hydrophobic IQ domain of the cardiac Ca(v)1.2 calcium channel. Structure 13, 1881–1886 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Ruschak A. M., Kay L. E. (2010) Methyl groups as probes of supramolecular structure, dynamics, and function. J. Biomol. NMR 46, 75–87 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Yamniuk A. P., Ishida H., Lippert D., Vogel H. J. (2009) Thermodynamic effects of noncoded and coded methionine substitutions in calmodulin. Biophys. J. 96, 1495–1507 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Ishida H., Rainaldi M., Vogel H. J. (2009) Structural studies of soybean calmodulin isoform 4 bound to the calmodulin-binding domain of tobacco mitogen-activated protein kinase phosphatase-1 provide insights into a sequential target binding mode. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 28292–28305 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Yuan T., Weljie A. M., Vogel H. J. (1998) Tryptophan fluorescence quenching by methionine and selenomethionine residues of calmodulin. Orientation of peptide and protein binding. Biochemistry 37, 3187–3195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Ivetic A., Florey O., Deka J., Haskard D. O., Ager A., Ridley A. J. (2004) Mutagenesis of the ezrin-radixin-moesin binding domain of L-selectin tail affects shedding, microvillar positioning, and leukocyte tethering. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 33263–33272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Killock D. J., Ivetić A. (2010) The cytoplasmic domains of TNFalpha-converting enzyme (TACE/ADAM17) and L-selectin are regulated differently by p38 MAPK and PKC to promote ectodomain shedding. Biochem. J. 428, 293–304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Ivetic A., Deka J., Ridley A., Ager A. (2002) The cytoplasmic tail of L-selectin interacts with members of the ezrin-radixin-moesin (ERM) family of proteins. Cell activation-dependent binding of Moesin but not Ezrin. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 2321–2329 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Berridge M. J. (2006) Calcium microdomains. Organization and function. Cell Calcium 40, 405–412 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Laudanna C., Constantin G., Baron P., Scarpini E., Scarlato G., Cabrini G., Dechecchi C., Rossi F., Cassatella M. A., Berton G. (1994) Sulfatides trigger increase of cytosolic free calcium and enhanced expression of tumor necrosis factor-α and interleukin-8 mRNA in human neutrophils. Evidence for a role of L-selectin as a signaling molecule. J. Biol. Chem. 269, 4021–4026 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Krummel M. F., Cahalan M. D. (2010) The immunological synapse. A dynamic platform for local signaling. J. Clin. Immunol. 30, 364–372 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Vig M., Kinet J. P. (2009) Calcium signaling in immune cells. Nat. Immunol. 10, 21–27 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Gifford J. L., Walsh M. P., Vogel H. J. (2007) Structures and metal ion-binding properties of the Ca2+-binding helix-loop-helix EF-hand motifs. Biochem. J. 405, 199–221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Furukawa Y., Umemoto E., Jang M. H., Tohya K., Miyasaka M., Hirata T. (2008) Identification of novel isoforms of mouse L-selectin with different carboxyl-terminal tails. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 12112–12119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Zhao L., Shey M., Farnsworth M., Dailey M. O. (2001) Regulation of membrane metalloproteolytic cleavage of L-selectin (CD62l) by the epidermal growth factor domain. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 30631–30640 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Deng W., Srinivasan S., Zheng X., Putkey J. A., Li R. (2011) Interaction of calmodulin with L-selectin at the membrane interface. Implication in the regulation of L-selectin shedding. J. Mol. Biol. 411, 220–233 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Barry W. T., Boudignon-Proudhon C., Shock D. D., McFadden A., Weiss J. M., Sondek J., Parise L. V. (2002) Molecular basis of CIB binding to the integrin αIIb cytoplasmic domain. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 28877–28883 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Denofrio J. C., Yuan W., Temple B. R., Gentry H. R., Parise L. V. (2008) Characterization of calcium- and integrin-binding protein 1 (CIB1) knockout platelets. Potential compensation by CIB family members. Thromb. Haemost. 100, 847–856 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Huang H., Vogel H. J. (2012) Structural basis for the activation of platelet integrin αIIbβ3 by calcium- and integrin-binding protein 1. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 134, 3864–3872 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Naik U. P., Naik M. U. (2003) Association of CIB with GPIIb/IIIa during outside-in signaling is required for platelet spreading on fibrinogen. Blood 102, 1355–1362 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Yamniuk A. P., Ishida H., Vogel H. J. (2006) The interaction between calcium- and integrin-binding protein 1 and the αIIb integrin cytoplasmic domain involves a novel C-terminal displacement mechanism. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 26455–26464 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Yuan W., Leisner T. M., McFadden A. W., Wang Z., Larson M. K., Clark S., Boudignon-Proudhon C., Lam S. C., Parise L. V. (2006) CIB1 is an endogenous inhibitor of agonist-induced integrin αIIbβ3 activation. J. Cell Biol. 172, 169–175 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Lai Z. W., Lew R. A., Yarski M. A., Mu F. T., Andrews R. K., Smith A. I. (2009) The identification of a calmodulin-binding domain within the cytoplasmic tail of angiotensin-converting enzyme-2. Endocrinology 150, 2376–2381 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Locke D., Liu C., Peng X., Chen H., Kahn M. L. (2003) FcRγ-independent signaling by the platelet collagen receptor glycoprotein VI. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 15441–15448 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Wong M. X., Harbour S. N., Wee J. L., Lau L. M., Andrews R. K., Jackson D. E. (2004) Proteolytic cleavage of platelet endothelial cell adhesion molecule-1 (PECAM-1/CD31) is regulated by a calmodulin-binding motif. FEBS Lett. 568, 70–78 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Haribabu B., Steeber D. A., Ali H., Richardson R. M., Snyderman R., Tedder T. F. (1997) Chemoattractant receptor-induced phosphorylation of L-selectin. J. Biol. Chem. 272, 13961–13965 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Kilian K., Dernedde J., Mueller E. C., Bahr I., Tauber R. (2004) The interaction of protein kinase C isozymes α, ι, and θ with the cytoplasmic domain of L-selectin is modulated by phosphorylation of the receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 34472–34480 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Mattila P. E., Green C. E., Schaff U., Simon S. I., Walcheck B. (2005) Cytoskeletal interactions regulate inducible L-selectin clustering. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 289, C323–C332 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]