Background: Copper modulates the metabolism of the Alzheimer disease amyloid precursor protein (APP).

Results: Histidine residues 149 and 151 of APP copper binding domain modulate APP ER-to-Golgi trafficking.

Conclusion: Histidines residues 149 and 151 of APP are pivotal for APP proteolytic processing.

Significance: Elucidating the copper binding domain elements involved in APP stabilization and metabolism is crucial for understanding the physiological role of APP.

Keywords: Alzheimer Disease, Amyloid Precursor Protein, Copper, Secretases, Trafficking, Amyloid beta

Abstract

One of the key pathological hallmarks of Alzheimer disease (AD) is the accumulation of the APP-derived amyloid β peptide (Aβ) in the brain. Altered copper homeostasis has also been reported in AD patients and is thought to increase oxidative stress and to contribute to toxic Aβ accumulation and regulate APP metabolism. The potential involvement of the N-terminal APP copper binding domain (CuBD) in these events has not been investigated. Based on the tertiary structure of the APP CuBD, we examined the histidine residues of the copper binding site (His147, His149, and His151). We report that histidines 149 and 151 are crucial for CuBD stability and APP metabolism. Co-mutation of the APP CuBD His149 and His151 to asparagine decreased APP proteolytic processing, impaired APP endoplasmic reticulum-to-Golgi trafficking, and promoted aberrant APP oligomerization in HEK293 cells. Expression of the triple H147N/H149N/H151N-APP mutant led to up-regulation of the unfolded protein response. Using recombinant protein encompassing the APP CuBD, we found that insertion of asparagines at positions 149 and 151 altered the secondary structure of the domain. This study identifies two APP CuBD residues that are crucial for APP metabolism and suggests an additional role of this domain in APP folding and stability besides its previously identified copper binding activity. These findings are of major significance for the design of novel AD therapeutic drugs targeting this APP domain.

Introduction

The amyloid precursor protein (APP)6 is a type 1 transmembrane glycoprotein that has a central role in the pathogenesis of AD as the source of the neurotoxic amyloid β peptide (Aβ). During trafficking through the secretory pathway, APP undergoes various post-translational modifications, such as N- and O-glycosylation, phosphorylation, and tyrosine sulfation (1–3). The N-glycosylated only, immature APP is mainly found in the endoplasmic reticulum/cis-Golgi region, whereas the N-O-glycosylated, mature, APP mostly localizes in the trans-Golgi/plasma membrane zone (3). Upon reaching the plasma membrane, APP is rapidly cleaved by α-secretase to release the ectodomain or endocytosed as a full-length protein in early endosomes (4, 5). Following internalization, the majority of endocytosed APP is rapidly sorted to the lysosomal compartment for degradation, whereas a smaller portion is recycled back to the plasma membrane (4).

APP is proteolytically processed by two different pathways. During amyloidogenic processing, APP is first cleaved at its β-site, generating the sAPPβ ectodomain (6) and the membrane-bound C-terminal domain (C99) species (7). C99 can subsequently be processed by γ-secretase, giving rise to Aβ and the APP intracellular domain (8). Amyloidogenic processing of APP occurs physiologically (9–11); therefore, imbalances of this event are linked to AD pathology. As suggested by its name, the non-amyloidogenic pathway prevents Aβ formation by cleaving APP at the α-site located within the Aβ sequence (12, 13). This event results in the shedding of the sAPPα ectodomain and the generation of the 83-amino acid C-terminal fragment (C83) (3), which can be further processed by γ-secretase in a similar way as for C99, giving rise to the analogous APP intracellular domain and a small p3 (14) fragment instead of Aβ.

Several studies have demonstrated altered APP metabolism in AD patients with increased (15–17) or decreased (16, 18) APP expression as well as up- or down-regulated β- and α-secretase activity, respectively, supporting a mismetabolism of APP in AD. Altered copper levels in hippocampus, amygdala, neuropil, cerebrospinal fluid, and serum of AD patients have also been reported (19–23). Moreover, there is a negative correlation between copper levels and elevated amyloidogenic processing of APP in AD animal models (24, 25).

The APP CuBD is located in the N-terminal part of the protein, next to the growth factor domain. Its tertiary structure is composed by an α-helix (147–159) packed against three β-sheets (133–139, 162–167, and 181–188) and stabilized by three disulfide bridges (Cys133–Cys187, Cys144–Cys174, and Cys158–Cys186) and a small hydrophobic core (Leu136, Trp150, Val153, Ala154, Leu165, Met170, Val182, and Val185) (26, 27). Strand β3 is connected to strand β1 and to the helix via Cys133–Cys187 and Cys158–Cys186 bonds, respectively, and the Cys144–Cys174 bond links together two loops located at the end of the molecule. APP His147, His151, and Tyr168 appear to be the putative binding ligands for copper because all of them have been confirmed by NMR and crystallography studies to be bound to or to be in close proximity to copper. The role of Met170 remains unclear because the crystallography data excludes its involvement in copper binding. By employing a synthetic peptide encompassing APP residues 135–156, earlier studies demonstrated that the CuBD can reduce Cu(II) to Cu(I) (28). The mutation of His147 to asparagine in this peptide decreased copper reduction (28) while leaving copper binding unaffected (29).

Copper has been shown to regulate APP metabolism. In cellular models, increased intracellular copper levels up-regulated APP expression (30) and promoted the non-amyloidogenic processing of APP (31). Moreover, APP trafficked from the Golgi to the plasma membrane exhibited a decreased endocytosis in response to copper (32). Conversely, a decrease in intracellular copper levels led to decreased APP expression (33) and increased amyloidogenic processing of APP (34). In addition, APP is thought to modulate copper homeostasis by participating in copper efflux (32). Studies in both animal and cellular models demonstrated increased levels of copper when the APP gene was knocked out (35, 36). Because APP is a copper-binding protein, these effects are likely to be related to the ability of APP to bind copper; however, this link has not yet been elucidated.

In this study, we investigated the effect of mutating the putative copper coordinating residues of APP, His147 and His151, and a control histidine (His149) residue, to asparagine on APP cellular metabolism. We report that the presence of asparagine residues at positions 149 and 151 impairs APP maturation and APP ER-to-Golgi trafficking. We provide evidence that this effect is due to APP retention in the ER most likely caused by APP misfolding.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Antibodies and Reagents

The following antibodies and dilutions were used for Western blotting: WO2 at 1:1000 (37) and syntaxin 6, EEA1, BIP, IRE1α, Ero1Lα, PERK, CHOP, PDI, calnexin, GAPDH, and β-tubulin all at 1:1000 except for EEA1 and GAPDH at 1:2500 and 1:5000, respectively (all from Cell Signaling); secondary IgG anti-mouse conjugated to horseradish peroxidase at 1:10,000 and secondary IgG anti-rabbit conjugated to horseradish peroxidase at 1:10,000 (both from GE Healthcare). The following antibodies were used for immunocytochemistry: WO2 at 1:500 (37), anti-GRASP65 at 1:1000 (Abcam; kind gift from Fiona Houghton and Prof. Paul Gleeson, University of Melbourne), secondary IgG anti-mouse conjugated to AlexaFluor® 488 at 1:1000 (Invitrogen), and secondary IgG anti-rabbit conjugated to AlexaFluor® 594 at 1:1000 (Invitrogen). DAPI nucleic acid stain (Invitrogen) was used at 1:1000 to detect the cell nucleus. The FK2 antibody (Enzo Life Sciences; kind gift from Belinda Guo and A/Prof. Andrew Hill, University of Melbourne) was used for the immunoprecipitation of ubiquitinated proteins (0.7 μl/700 μl of lysate). Brefeldin A (Sigma) was employed at 1 μg/ml. Capture and detection antibodies used for the Aβ detection enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) were a kind gift from Dr. Lisa Muenter and Prof. Gerd Multhaup (Freie Universität Berlin, licensed by The Genetics Company).

Cell Culture

WT human embryonic kidney 293 (HEK293) (ATCC) cells were maintained at 37 °C in 5% CO2 in DMEM (Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% (v/v) fetal bovine serum (Invitrogen), 2 mm l-glutamine (Invitrogen), 100 units/ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin (Invitrogen). The same conditions and the same culture medium supplemented with 6 μg/ml Blasticidin (Invitrogen) or 500 μg/ml Geneticin (Invitrogen) were employed to maintain stably transduced HEK293 cells or WT 293FT producer cells.

Generation of APP-HEK293 Stable Cell Lines

The wild type APP695 cDNA was subcloned into the pLenti6/V5-D-TOPO vector (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, blunt-end APP695 was generated by amplification of APP695 cDNA and inserted into pLenti6/V5-D-TOPO vector by employing the TOPO cloning reaction. A STOP codon was included in the C-terminal primer to prevent fusion of APP with the V5 tag contained in the pLenti6/V5-D-TOPO vector. The WT-APP-pLenti construct was used as a template to introduce H147N, H149N, H151N, H147N/H149N, H147N/H151N, H149N/H151N, and H147N/H149N/H151N mutations by site-directed mutagenesis (QuikChange system, Stratagene). Lentivirus particles were generated by co-transfection of the 293FT producer cell line with the construct of interest, the packaging mix (Invitrogen), and the Lipofectamine 2000TM reagent according to manufacturer's instructions. HEK293 cells were transduced by overnight incubation with the lentivirus particles, and cells stably expressing APP were selected with Blasticidin (6 μg/ml).

Aβ Detection by Sandwich ELISA

Cells were plated in poly-d-lysine-precoated 6-well plates at 0.5 × 106 cells/well and cultured for 4 days. 96-well plates were coated overnight at 4 °C with mouse WO2 (0.55 μg/well) antibody diluted in carbonate buffer (100 mm, pH 9.6) and then blocked with Stabilcoat buffer (Surmodics) for 2 h at room temperature. Plates were washed three times for 3 min each with low salt PBS-T buffer (3.8 mm NaH2PO4, 16.2 mm Na2HPO4, 150 mm NaCl, 0.1% (v/v), pH 7.4), and then sample-binding buffer (80 mm PBS, pH 7.4, 1.5% BSA, 0.5% Tween 20, 0.1% thimerosal) was added together with cell culture medium to the 96-well plate and incubated overnight at 4 °C. The plates were again washed three times for 3 min each with low salt PBS-T buffer, and then 4G8-HRP-conjugated antibody (1:20,000 in sample-binding buffer) was added to the wells, and the plate was rocked at room temperature for 30 min. After five 3-min washes, 100 μl of 3,3′,5,5′-tetramethylbenzidine (TMB) substrate (One-Step Ultra TMB, Thermo Scientific) were added to each well, the plate was incubated at room temperature in the dark for 30 min, and the reaction was stopped by adding 3% HCl (50 μl/well). Absorbance was read at a wavelength of 450 nm (FLUOstar Omega microplate reader, BMG Labtech).

Iodixanol Fractionation

Cells were cultured in 175-cm2 flasks until they reached ∼90% confluence. On the day of the fractionation, cells were washed with PBS and homogenized in 1 ml of ice-cold homogenization buffer (20 mm Hepes/NaOH, pH 7.4, 1 mm EDTA, 1 mm EGTA, 0.25 m sucrose) containing complete protease inhibitor mixture (Roche Applied Science) by 15 passages through a 26-gauge needle and 30 strokes with a Dounce homogenizer in ice. The cell homogenate was centrifuged at 1000 × g for 10 min at 4 °C, the resulting postnuclear supernatant was collected, and its iodixanol concentration was adjusted to 25% with ice-cold 50% iodixanol (5 volumes of 60% iodixanol (Optiprep, Sigma-Aldrich) diluted with one volume of dilution buffer (120 mm Hepes/NaOH, pH 7.4, 6 mm EDTA, 6 mm EGTA, 0.25 m sucrose)) containing protease inhibitors. The sample was placed on the bottom of an ultracentrifugation tube, and fractions of 20, 18.5, 17, 15.5, 14, 12.5, 11, 9.5, 8, and 6% ice-cold iodixanol (50% iodixanol diluted with homogenization buffer) containing protease inhibitor were successively layered above it. After 20 h of centrifugation at 90,000 × g at 4 °C (SW41Ti rotor, Beckman), fractions of 0.5 ml were collected from the top of the tube, precipitated using acetone, resuspended in sample buffer, and boiled, and equal volume of each fraction was used for electrophoresis followed by immunoblot with WO2 (1:1000), BiP (1:1000), syntaxin 6 (1:1000), or EEA1 (1:1000) antibodies.

Immunocytochemistry

Cells were grown on poly-d-lysine-precoated 13-mm glass coverslips for 2 days. Only for the ER localization experiment, cells were transfected with a red fluorescent protein fused to an ER retention signal (CellLight ER-RFP BacMam 2.0, Invitrogen) before immunostaining according to the manufacturer's instructions. Following cell standard culture (Golgi localization experiment) or cell transfection (ER localization experiment), cells were fixed using 4% (w/v) paraformaldehyde (Acros Organics) in PBS for 20 min and permeabilized by incubation with 0.1% Triton X-100 (Ajax Finchem) in PBS for 3 min, and nonspecific sites were blocked in 2% (w/v) BSA (Sigma) in PBS (block buffer) for 1 h. WO2 (1:500 in block buffer) and anti-GRASP65 (1:1000 in block buffer) primary antibodies were used for immunocytochemistry. Primary antibodies were detected using secondary IgG antibodies conjugated to AlexaFluor® 488 or AlexaFluor® 594 fluorophores. Images were taken using a Leica TCS SP2 confocal microscope.

Immunoprecipitation

Cell lysate (1 ml) was precleared with Protein G-Sepharose beads (50 μl) for 1 h at 4 °C. Precleared lysate was split in three aliquots and incubated first with FK2 or WO2 (both 0.7 μl for 300 μl of lysate) or no antibody for 1 h at 4 °C and then with 20 μl of Protein G-Sepharose beads overnight (14–18 h) at 4 °C. All incubation steps were performed on a rotating wheel. Isolated beads where then washed three times with STEN buffer (50 mm Tris, pH 7.6, 150 mm NaCl, 2 mm EDTA, 1% Nonidet P-40, protease inhibitors), mixed with sample buffer, boiled, and centrifuged. Supernatant was collected and analyzed by electrophoresis and WO2 antibody immunoblot. All centrifugation steps for pelleting beads were performed at 3000 × g for 5 min at 4 °C.

Expression and Purification of Recombinant CuBD

The cloning and the expression of the APP CuBD encompassing residues 133–189 of human WT-APP has been described in detail elsewhere (38). Briefly, the protein was cloned into the pPIC-9 vector and expressed in Pichia pastoris. The protein was then concentrated using a centrifugal filter device (Amicon) with a molecular mass cut-off of 3 kDa, purified by size exclusion chromatography (Hiload 16/60 Superdex 75 prep grade column, GE Healthcare) by eluting the proteins with 10 mm sodium phosphate buffer, pH 7.4, followed by HPLC chromatography (VYDAC 208TP C8 reversed phase column, Grace) with Buffer A = 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid in water and Buffer B = 0.1% TFA in acetonitrile (15–50% Buffer B over a 30-min gradient). The peptides were then collected and lyophilized.

Circular Dichroism

The purified and lyophilized proteins were resuspended in 10 mm phosphate buffer, pH 7.4, prior to circular dichroism (CD) analysis. CD measurements were performed on a JASCO 815 CD spectrometer (Tokyo, Japan), using Jasco software. Far UV CD spectra were collected between 180 and 260 nm at 20 °C. Measurements were recorded at 50 nm/min with a bandwidth of 1 nm and a response time of 8 s by averaging three accumulation scans per measurement. All spectra were background-subtracted and smoothed with the default algorithm in the Jasco software. Deconvolution of the spectra was performed using the Dichroweb algorithm CDSSTR (39–42).

Graphic Simulation of Protein Three-dimensional Structure

Protein three-dimensional structures were displayed using the molecular graphic software MOLMOL (Reto Koradi, Institut für Molekularbiologie und Biophysik, Eidgenössische Technische Hochschule-Hönggerberg, CH-8093, Zurich, Switzerland) (43) and the 1OWT data from the Protein Data Bank.

RESULTS

His147, His149, and His151 Mutations Decrease Secreted Aβ Levels

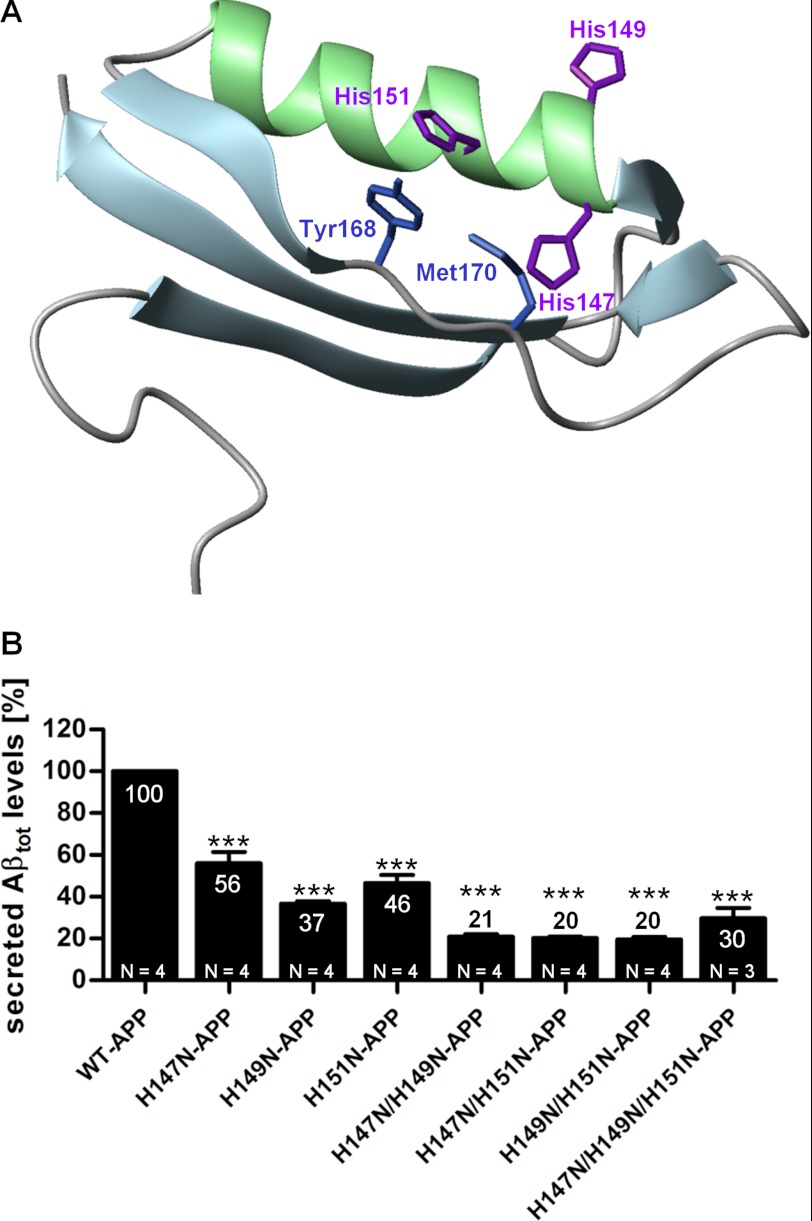

To assess whether the APP N-terminal CuBD is involved in regulating APP metabolism, we investigated the effect on Aβ secretion of mutating the putative copper-coordinating histidine residues, His147 and His151, and the non-coordinating His149 (Fig. 1A), to asparagine. The histidine-to-asparagine mutation is considered a moderately conservative mutation because it maintains steric characteristics although it decreases acid-base and hydrogen bonding properties (the histidine imidazole ring increases hydrogen transfer capabilities). We generated APP mutants bearing single mutations, double mutations, or the triple mutation and stably overexpressed them in HEK293 cells. Aβ levels were measured in conditioned cell culture medium by a sandwich ELISA using WO2 antibody, and values were normalized to total cellular protein concentration and total intracellular APP levels of the corresponding lysates (Fig. 1B). This allowed us to adjust for any variation in total expression levels between the mutants. Statistical analysis revealed that all mutations caused a significant decrease in Aβ levels. Compared with WT-APP, the H147N, H149N, and H151N single mutations decreased Aβ levels to ∼55, ∼35, and ∼45%, respectively, all of the double mutations (H147N/H149N, H147N/H151N, and H149N/H151N) to ∼20%, and the triple mutation (H147N/H149N/H151N) to ∼30%.

FIGURE 1.

Mutations of His147, His149, and His151 decrease secreted Aβ levels. A, APP CuBD three-dimensional structure indicating the mutated histidines (purple) and the other two residues putatively involved in copper binding, Tyr168 and Met170. B, HEK293 cells stably overexpressing WT-APP or APP mutants (single, double, and triple mutants) were cultured under standard conditions. Conditioned cell culture media were examined by sandwich ELISA using WO2 antibody, and values were normalized to total cellular protein concentration and total intracellular APP levels of the corresponding lysates and expressed as a percentage relative to that of WT-APP (100%). Data are expressed as mean ± S.E. (error bars) of four repeats (three repeats for H147N/H149N/H151N-APP) of the same experiments; statistical significance values were calculated with one-way ANOVA using Dunnett's post hoc test comparing each mutant with the WT-APP control. **, p < 0.01.

His149 is not part of the copper binding ligands (26, 27) and was initially employed as a control mutation. Its unexpected involvement in controlling APP metabolism suggested that mechanisms other than copper binding (or at least other than direct copper binding) might underlie the reduction in secreted Aβ levels caused by His147, His149, and His151 mutations.

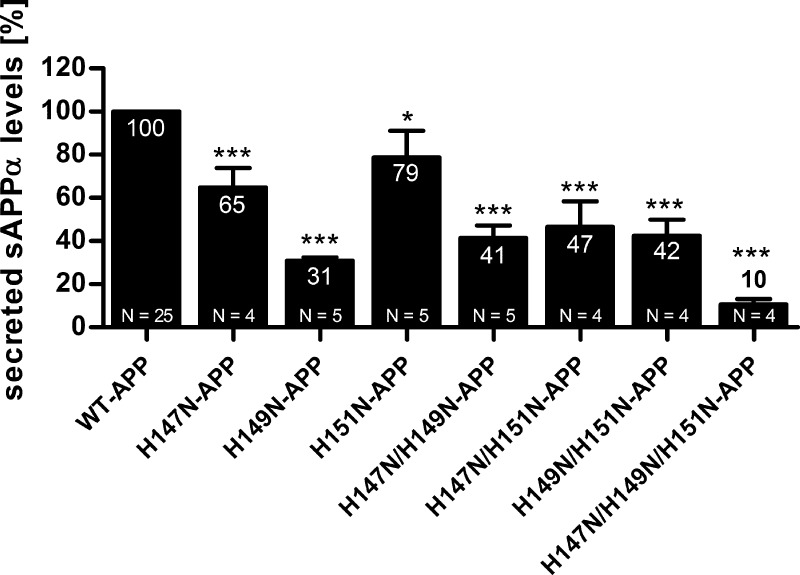

His147, His149, and His151 Mutations Decrease Secreted sAPPα Levels

To assess whether the non-amyloidogenic processing of APP was affected by the mutation of His147, His149, and His151, conditioned cell culture media were examined for sAPPα by quantitative Western blotting analysis using the WO2 antibody. As for Aβ, sAPPα levels were standardized to total intracellular APP levels of the corresponding lysates to adjust for any variation in total expression levels between the mutants. Compared with WT-APP-HEK, all of the APP mutant HEK cells exhibited significantly decreased levels of sAPPα (note that the graph represents sAPPα levels standardized to the respective levels of total cellular APP after densitometry and not the absolute sAPPα values) (Fig. 2). More precisely H147N, H149N, and H151N mutations reduced sAPPα levels to about 65, 30, and 80%, respectively. For the three double mutations, sAPPα levels were decreased to about 45%, and the triple mutant exhibited the strongest reduction, dropping sAPPα levels to only 10%.

FIGURE 2.

Mutations of His147, His149, and His151 decrease secreted sAPPα levels. HEK293 cells stably overexpressing WT-APP or APP mutants (single, double, and triple mutants) were cultured under standard conditions. Conditioned cell culture media were examined by Western blot technique using WO2 antibody to detect sAPPα metabolite. Densitometry values were normalized to intracellular APP levels of the corresponding lysates and expressed as a percentage relative to that of WT-APP (100%). Data are expressed as mean ± S.E. (error bars). N indicates the number of times the experiment was performed. Statistical significance values were calculated with one-way ANOVA using Dunnett's post hoc test comparing each mutant with the WT-APP control. **, p < 0.01.

Together with the reduction in secreted Aβ levels, these findings suggested a general decrease in APP processing (both amyloidogenic and non-amyloidogenic processing) for the APP histidine mutants. This general reduction in processing might indicate a reduced intracellular trafficking through the secretory pathway.

Specific Combinations of His147, His149, and His151 Mutations Decrease Secreted sAPPβ Levels

To further our understanding of the effect of the His147, His149, and His151 mutations on APP cellular metabolism, the secreted levels of sAPPβ were analyzed. Conditioned cell culture media were examined by Western blotting using an antibody specific to sAPPβ (not reacting with sAPPα or full-length APP), and the resulting densitometry values were standardized to total intracellular APP levels of the corresponding lysates (Fig. 3).

FIGURE 3.

Specific combinations of His147, His149, and His151 mutations decrease secreted sAPPβ levels. HEK293 cells stably overexpressing WT-APP or APP mutants (single, double, and triple mutants) were cultured under standard conditions. Conditioned cell culture media were examined by Western blot technique using an antibody specific to sAPPβ. Densitometry values were normalized to intracellular APP levels of the corresponding lysates and expressed as a percentage relative to that of WT-APP (100%). Data are expressed as mean ± S.E. (error bars). N indicates the number of times the experiment was performed. Statistical significance values were calculated with one-way ANOVA using Dunnett's post hoc test comparing each mutant with the WT-APP control. **, p < 0.01.

Secreted sAPPβ levels were reduced to ∼65% by H147N, H147N/H149N, and H149N/H151N mutations. A more pronounced decrease (∼40%) was observed for H149N and H147N/H149N/H151N mutations. Interestingly, H151N and H147N/H151N mutations did not affect secreted sAPPβ levels, despite exhibiting reduced levels of secreted Aβ.

When combined with the secreted Aβ and sAPPα data, these findings suggested that His147, His149, and His151 mutations can affect APP metabolism by various means, potentially altering different mechanisms related to APP metabolism, such as APP cellular trafficking, membrane APP endocytosis, and/or APP intrinsic ability to interact with the α-, β-, and γ-secretase.

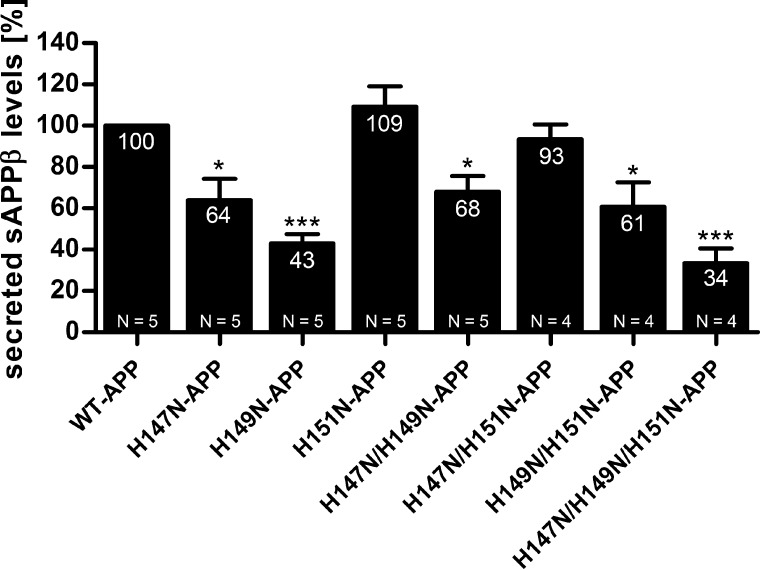

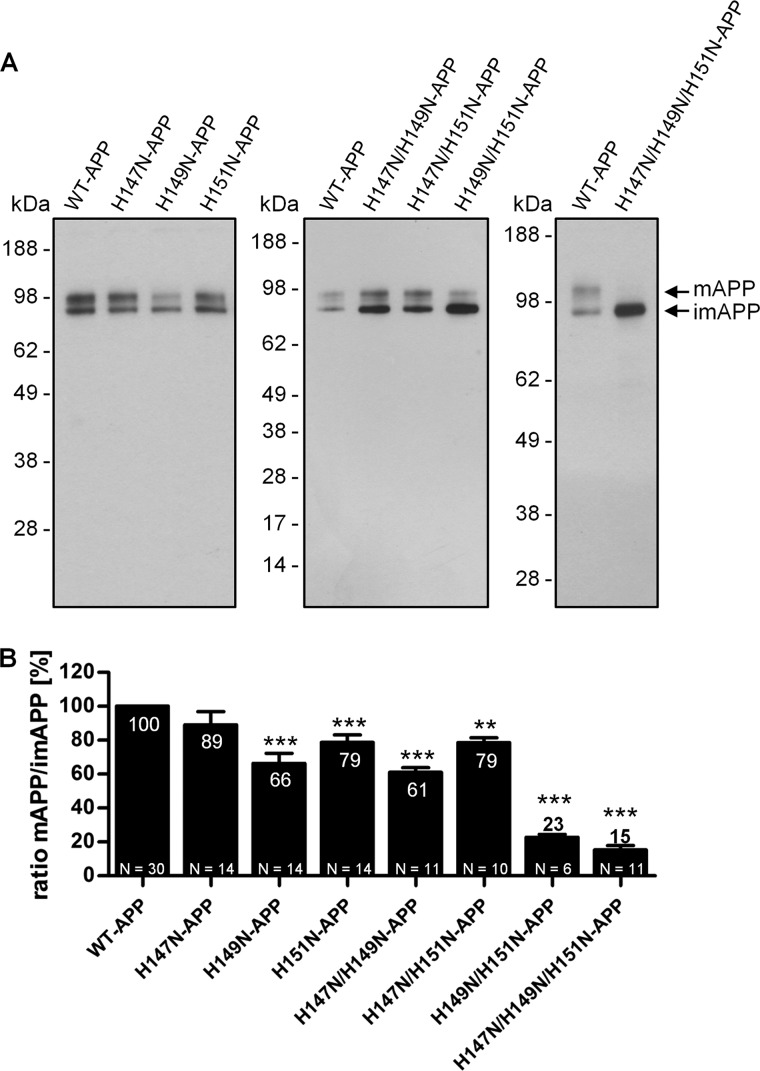

Mutating His149 and His151 to Asparagine Impairs APP Maturation in HEK293 Cells

We next investigated APP maturation, which constitutes the first step of APP cellular metabolism and includes O-glycosylation of N-glycosylated APP upon APP trafficking from the ER to the Golgi. Cell lysates were examined by quantitative Western blotting analysis using the WO2 antibody (Fig. 4A), and the ratio of mature APP to immature APP (m/imAPP) was calculated for each cell line (Fig. 4B). The single mutations H149N and H151N and the double mutations H147N/H149N and H147N/H151N significantly decreased the m/imAPP ratio in a similar manner (∼30%). This phenotype was strongly exacerbated by the H149N/H151N double mutation and the triple mutation (H147N/H149N/H151N), which both reduced the m/imAPP ratio by ∼80%. In contrast to all of the other mutations, the single mutation H147N did not affect the m/imAPP ratio.

FIGURE 4.

Mutations of APP His149 and His151 impair APP maturation. HEK293 cells stably overexpressing WT-APP or APP mutants (single, double, and triple mutants) were cultured under standard conditions. Cell lysates were normalized to total protein concentration levels before SDS-PAGE. A, the WO2 antibody was used to detect intracellular full-length APP in cell lysates. The arrows indicate bands corresponding to mAPP and imAPP. B, the ratio of the mature over the immature APP levels was calculated and expressed as a percentage relative to that of WT-APP (100%). Data are expressed as mean ± S.E. (error bars). N indicates the number of times the experiment was performed. Statistical significance values were calculated with one-way ANOVA using Tukey's post hoc test. **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001.

These data suggested two different degrees of impairment in APP maturation, a relatively mild impairment caused by mutating either His149 or His151 to asparagine and a strong impairment when both His149 and His151 are mutated to asparagines.

With the premise that the observed decreased APP maturation is due to impaired APP ER-to-Golgi trafficking (3), this phenomenon would reduce extracellular APP metabolite levels because less APP would go through the secretory pathway and reach the plasma membrane. Thus, the impairment in APP maturation observed for the His149 and His151 mutations was likely to underlie the decreased levels of secreted Aβ, sAPPβ, and sAPPα. Nevertheless, the differences in Aβ and sAPPα levels between the mutants with a similar extent of impairment in APP maturation and the normal levels of secreted sAPPβ for H151N- and H147N/H151N-APP mutants suggested the involvement of other events in addition to ER-to-Golgi trafficking.

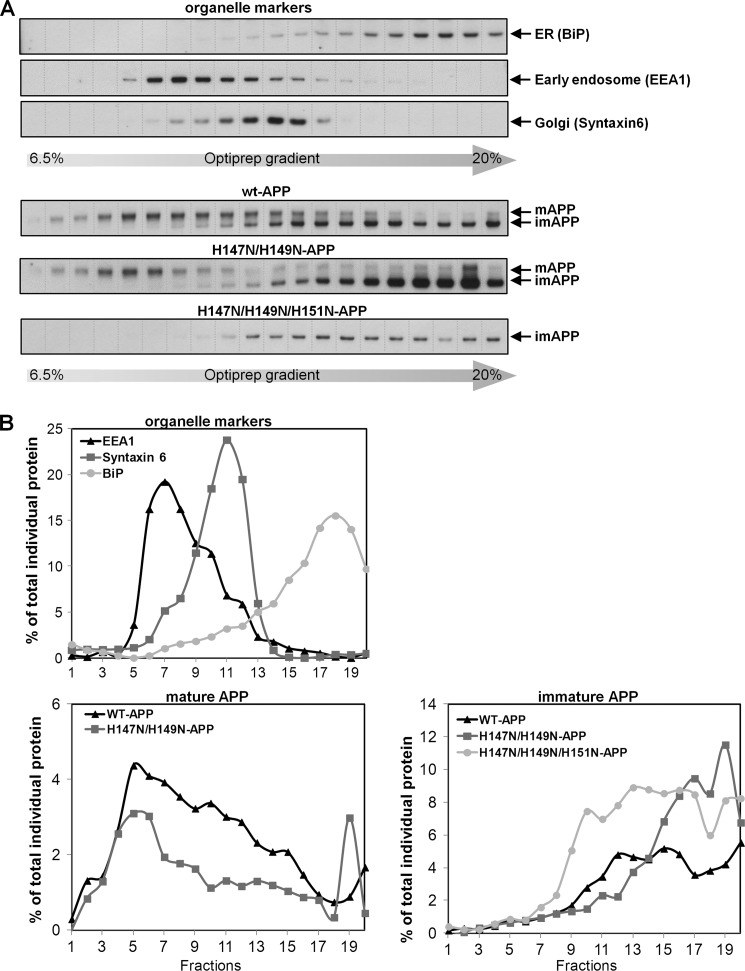

Mutating His149 and His151 to Asparagine Impairs APP ER-to-Golgi Trafficking

In WT cells, immature APP (N-glycosylated) is mainly localized in the ER/cis-Golgi region, whereas mature APP (N- and O-glycosylated) is in the trans-Golgi and post-Golgi subcellular compartments (3). With the premise that decreased APP maturation could be due to impaired APP ER-to-Golgi trafficking, we studied the subcellular APP localization of the H147N/H149N-APP and the H147N/H149N/H151N-APP mutants. These mutants were chosen because they represented mild and strong impairment of APP maturation, respectively. Analysis of APP subcellular distribution by iodixanol gradient fractionation revealed that wild type mAPP and imAPP colocalized in the early endosomes/Golgi and in the ER-containing fractions, respectively (Fig. 5A). H147N,H149N-mAPP was correctly localized in the early endosomes and Golgi; however, it constituted a smaller portion of total APP compared with WT-mAPP (Fig. 5B). H147N/H149N/H151N does not have any mature APP, so no APP was detected in the early endosome or Golgi of this mutant. Conversely, the immature APP form of the H147N/H149N and H147N/H149N/H151N mutants correctly localized in the ER (Fig. 5A); however, it constituted a higher percentage of total APP compared with WT-imAPP (Fig. 5B). These data suggested that the impairment of H147N/H149N-APP and H147N/H149N/H151N-APP maturation was due to a decrease in APP trafficking from the ER to the Golgi. These data also suggested that mild and severe impairment of APP maturation were due to different extents of APP retention in the ER.

FIGURE 5.

H147N/H149N- and H147N/H149N/H151N-APP mutations impair APP ER-to-Golgi trafficking. A, homogenates of HEK293 cells stably overexpressing WT-, H147N/H149N-, or H147N/H149N/H151N-APP were fractionated through an iodixanol step gradient. Western blot analysis showed the distribution of mAPP, imAPP, BiP (ER marker), syntaxin 6 (Golgi marker), and EEA1 (early endosome marker). B, quantification of mature APP distribution showed that the H147N/H149N-mAPP (no H147N/H149N/H151N-mAPP was detected) is found mainly in the Golgi and early endosome fractions, as for WT-APP; however, it constitutes a lower percentage of the total APP compared with WT-APP. H147N/H149N- and H147N/H149N/H151N-imAPP are found mainly in the ER fractions, as for WT-APP; however, they respectively constitute a higher percentage of the total APP compared with WT-APP, indicating a partial retention of these mutants of APP in the ER. Values are expressed as a percentage of the total specific protein (sum of all the fractions) except for mAPP and imAPP, which are expressed as a percentage of the total APP (sum of mAPP and imAPP in all fractions).

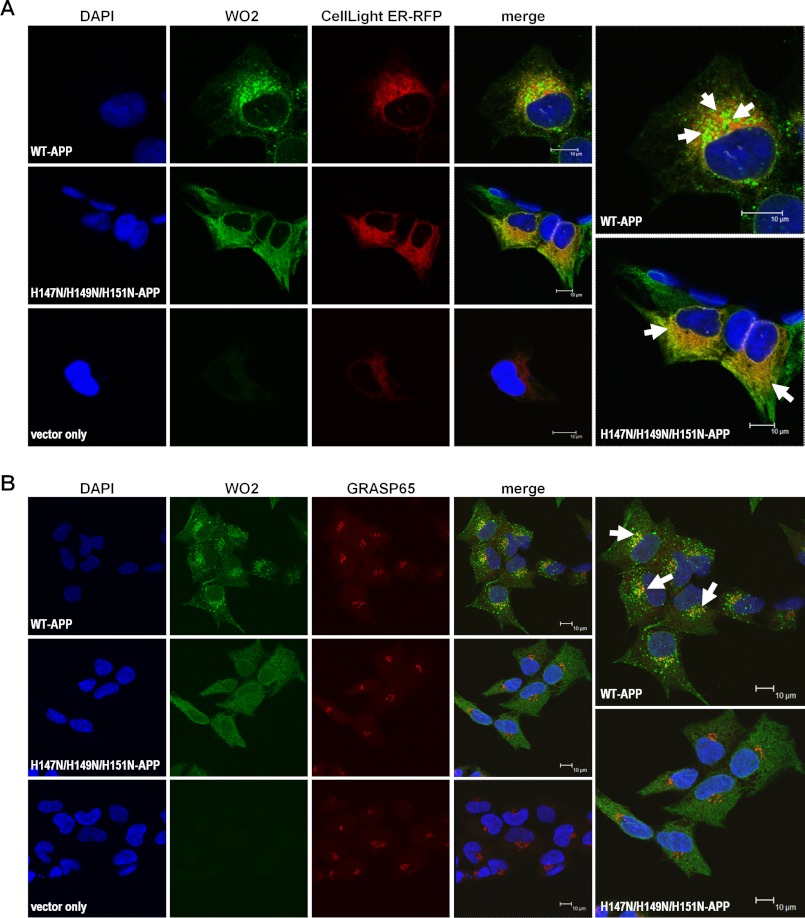

Impairment of H147N/H149N/H151N-APP trafficking from the ER to the Golgi was further confirmed using immunofluorescence confocal microscopy, which revealed perinuclear punctuated staining for WT-APP (WO2) partially colocalizing with the ER (Fig. 6A). Compared with WT-APP, the H147N/H149N/H151N-APP mutant exhibited a different staining pattern, less punctuated and more evenly spread, with qualitatively higher ER colocalization (Fig. 6A). HEK cells expressing the vector alone demonstrated a very weak APP signal, indicating that endogenous APP was contributing negligible fluorescence (Fig. 6A). Fluorescence confocal microscopy indicated partial colocalization of WT-APP to the Golgi, whereas there was no Golgi colocalization detectable for H147N/H149N/H151N-APP, in accordance with the absence of this mutant in the Golgi (Fig. 6B).

FIGURE 6.

Corroboration of H147N/H149N/H151N-APP impaired ER-to-Golgi trafficking. A, immunofluorescence confocal microscopy of WO2 antibody-stained WT-APP-, H147N/H149N/H151N-APP-, and vector-alone-HEK cells transiently expressing an ER-localized red fluorescence protein. Distinct APP distribution patterns were noticeable for WT- and H147N/H149N/H151N-APP, both showing a certain degree of colocalization with the ER, which appeared to be significantly higher for the latter. Cells expressing the vector alone exhibited minimal WO2 staining, suggesting negligible APP endogenous signal. B, images merging WO2 and anti-GRAPS65 (Golgi marker) signals showed partial colocalization of WT-APP in the Golgi, whereas no such characteristic was detectable for H147N/H149N/H151N-APP, indicating a lack of this mutant APP in the Golgi. Arrows, overlapped signal. For all images, the indicated scale bar corresponds to 10 μm.

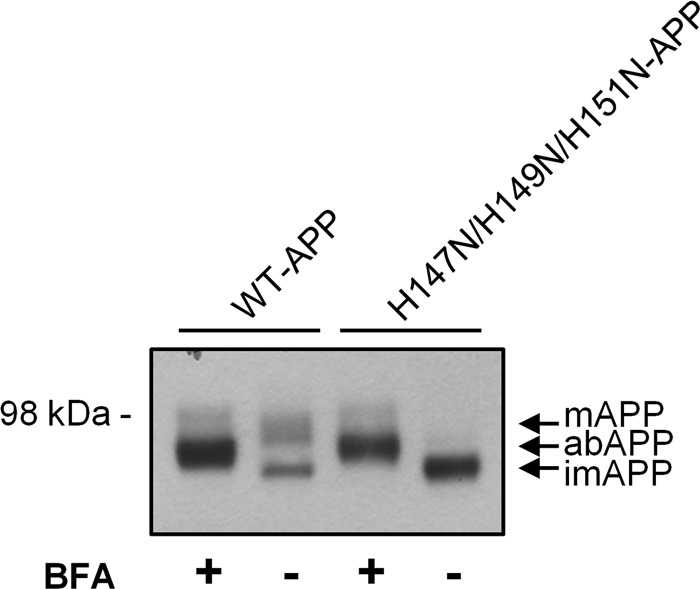

The subcellular localization data suggested that the impairment in APP maturation was due to hampered APP ER-to-Golgi trafficking rather than the inability of APP to be O-glycosylated when properly trafficked. To test the ability of H147N/H149N/H151N-APP to undergo O-glycosylation, when localized in the same compartment as the O-glycosylation enzymes, the cells were treated with Brefeldin A (BFA). BFA causes the fusion of Golgi membranes with the ER, leading to partial redistribution of Golgi enzymes into the ER (44), except for the trans-Golgi network enzymes (45, 46). BFA treatment is known to cause abnormal glycosylation of WT-APP, which results in an intermediate molecular weight band between the immature and mature APP species (47). Following BFA treatment, a new WT-APP species was detected with a molecular mass bigger than immature APP but smaller than mature APP (Fig. 7), as reported previously for BFA-treated cells (47). The same intermediate band was found when H147N/H149N/H151N-APP-HEK cells were exposed to BFA (Fig. 7), confirming the ability of this mutant to undergo O-glycosylation when it interacts with the appropriate enzymes.

FIGURE 7.

H147N/H149N/H151N-APP partially undergoes O-glycosylation under BFA treatment. HEK293 cells stably overexpressing WT- or H147N/H149N/H151N-APP-HEK cells were exposed to BFA (1 μg/ml) for 5 h. Western blot analysis of lysates showed the formation of a unique APP intermediate band (with respect to molecular weight) for both BFA-treated cell lines, indicating the ability of H147N/H149N/H151N-APP to undergo partial O-glycosylation when able to interact with the appropriate Golgi-residing enzymes. This aberrantly glycosylated APP (abAPP) had been previously observed and attributed to the partial redistribution of Golgi enzymes into the ER caused by BFA (44–47).

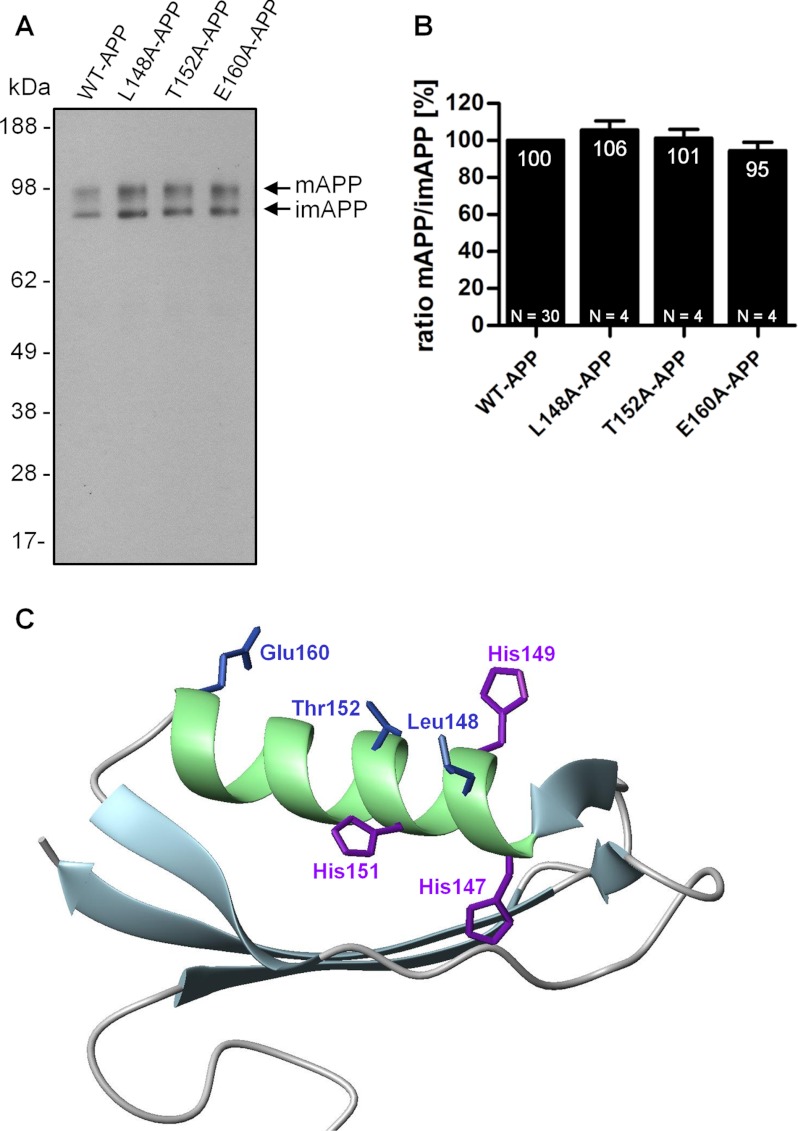

Impairment in APP Maturation Is Specific to H149N and H151N Mutation

The significant involvement of His149 in APP impaired maturation is interesting because the residue points in the opposite direction, away from the copper binding site (Figs. 1A and 8C). This led us to explore the existence of a surface patch of residues controlling APP maturation, possibly via intermolecular interactions. Based on the three-dimensional structure of the APP CuBD, we assessed whether other residues residing on the CuBD α-helix, as do His149 and His151, could play a role in modulating the m/imAPP ratio. Three residues (Leu148, Thr152, and Glu160) with side chains orientated between His149 and His151 and evenly distributed along the helix were identified (Fig. 8C) and tested (Fig. 8A). L148A, T152A, and E160A mutations did not affect the m/imAPP ratio (Fig. 8B), suggesting a specific involvement for His149 and His151 in modulating m/imAPP ratio as opposed to any other residues located on the CuBD α-helix and oriented in similar directions.

FIGURE 8.

Impairment in APP maturation is specific to H149N and H151N mutation. HEK293 cells stably overexpressing WT-APP or mutants of other non-histidine residues with side chains orientated between His149 and His151 along the helix were cultured under standard conditions. Cell lysates were normalized to total protein concentration levels before SDS-PAGE. A, the WO2 antibody was used to detect intracellular full-length APP in cell lysates. The arrows indicate bands corresponding to mAPP and imAPP. B, the ratio of the mature over the immature APP levels was calculated and expressed as a percentage relative to that of WT-APP (100%). Data are expressed as mean ± S.E. (error bars). N indicates the number of times the experiment was performed. Statistical significance values (p < 0.05) were calculated with one-way ANOVA using Tukey's post hoc test. C, APP CuBD three-dimensional structure, indicating His147, His149, and His151 residues (purple) and the three mutated non-histidine residues with side chains orientated between His149 and His151 along the helix (blue).

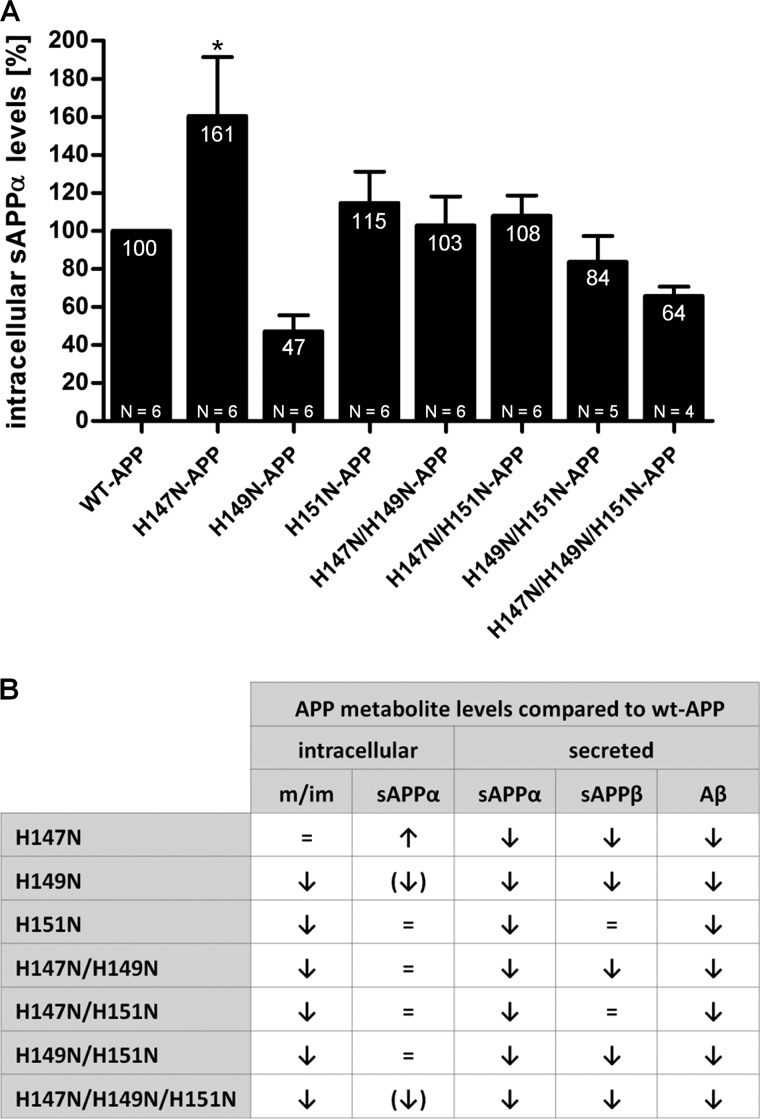

H147N Mutation Increases Intracellular Levels of sAPPα

The impairment in APP ER-to-Golgi trafficking caused by His149 and His151 led us to investigate the levels of intracellular APP metabolites. Cell lysates were examined by quantitative Western blotting analysis using an antibody specifically recognizing sAPPα (not cross-reacting with full-length APP or sAPPβ), and the resulting values were standardized to corresponding total intracellular APP levels (Fig. 9A).

FIGURE 9.

H147N mutation increases intracellular levels of sAPPα. A, HEK293 cells stably overexpressing WT-APP or APP mutants (single, double, and triple mutants) were cultured under standard conditions. Cell lysates were examined by Western blot technique using an antibody specific to sAPPα. Densitometry values were normalized to intracellular total APP levels of the corresponding lysates and expressed as a percentage relative to that of WT-APP (100%). Data are expressed as mean ± S.E. (error bars). N indicates the number of times the experiment was performed. Statistical significance values were calculated with one-way ANOVA using Dunnett's post hoc test comparing each mutant with the WT-APP control. **, p < 0.01. B, summary of the effects of His-147, His-149, and His-151 mutations on APP metabolite levels.

None of the His149- or His151-containing mutations had a significant effect on intracellular sAPPα levels compared with WT-APP; however, the H149N- and H147N/H149N/H151N-APP mutants exhibited a trend toward a decrease. These findings were consistent with the two same mutations causing the strongest reduction in secreted sAPPα (compared with the other mutations).

Interestingly, the H147N-APP mutant showed a significant increase of about 60% in intracellular sAPPα levels compared with the WT-APP. The respective increase and decrease of intracellular and secreted H147N-sAPPα, together with the decrease of other secreted H147N-APP metabolites (sAPPβ and Aβ), suggested a mechanism possibly involving decreased H147N-APP transport to the plasma membrane with potential retention in organelles where sAPPα can be generated (48) rather than an increase in the intrinsic propensity of H147N-APP to interact with α-secretase. We attempted to measure intracellular sAPPβ and Aβ levels; however, their signals were masked by nonspecific signal or were under the detection limits, respectively.

Despite all of the His149 and His151 mutations impairing APP maturation and decreasing secreted sAPPα levels, the modulation of intracellular sAPPα and secreted sAPPβ and Aβ levels was specific to the different mutants and indicated three distinct phenotypes (Fig. 9B). Of all of the His149 and His151 mutants, only H151N- and H147N/H151N-APP showed normal levels of intracellular sAPPα and secreted sAPPβ and Aβ. A second phenotype was shown by the H147N/H149N- and H149N/H151N-APP mutants, which exhibited decreased secreted sAPPα and Aβ levels, as well as a trend toward decreased secreted sAPPβ, with normal levels of intracellular sAPPα. The H149N- and H147N/H149N/H151N-APP mutants showed a third phenotype, where all of the measured APP metabolites, both intracellular and secreted, were significantly decreased compared with WT-APP.

In contrast to all of the other mutants, H147N-APP not only exhibited normal APP maturation but was the only mutant showing increased intracellular sAPPα levels (Fig. 9B). These findings, together with H147N-APP having decreased secreted sAPPα levels, suggested APP retention in post-ER organelles where α-secretase cleavage occurs (48).

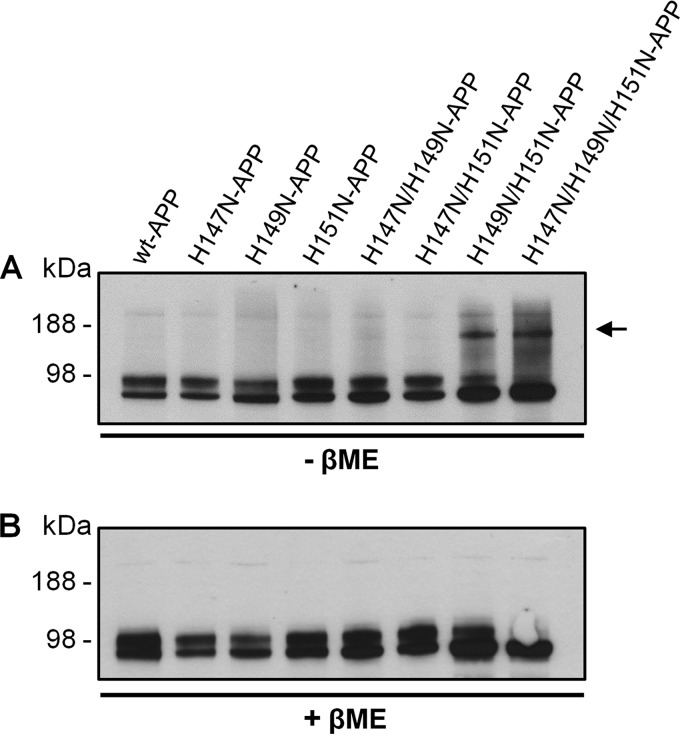

Co-mutation of His149 and His151 to Asparagine Promotes Aberrant APP SDS-resistant Oligomerization

The unlikely involvement of APP copper binding or intermolecular interactions driving the APP maturation impairment mediated by H149N and H151N mutations led us to explore other explanations for this phenomenon. A possible reason for a protein to be retained in the ER is its inability to achieve the proper tertiary and quaternary conformation. Because specific amino acids can be crucial for correct protein folding and oligomerization, substitution of these key residues can destabilize the final protein structure.

Thus, the retention of APP in the ER caused by H149N and H151N mutations could be due to misfolding and aggregation of the APP protein. To test if aberrant oligomerization had occurred, the reducing agent β-mercaptoethanol (βME) was omitted from the cell lysate. SDS-PAGE analysis detected a higher molecular weight species exclusively for the H149N/H151N-APP and H147N/H149N/H151N-APP mutants (Fig. 10A). This band migrated slightly below the 188 kDa marker, suggesting that it was either an APP homodimer (expected at ∼200 kDa) or APP bound to an unidentified protein. The persistence of this H149N/H151N- and H147N/H149N/H151N-APP oligomer in the presence of SDS, but not with βME (Fig. 10B), indicated that the oligomer subunits were linked together via disulfide bonds. The mutants that formed oligomers still had detectable levels of monomeric APP, indicating that only a portion of APP with these mutations formed disulfide-linked oligomers. Aberrant formation of disulfide-bonded oligomers of APP might arise from improper APP folding, which would preclude the formation of correct disulfide bridges, leaving free thiols available for erroneous interactions.

FIGURE 10.

Co-mutation of His149 and His151 promotes APP aberrant SDS-resistant oligomerization. A, immunoblot of cell lysates prepared with non-reducing sample buffer lacking βME revealed the presence of a higher molecular size band just below 188 kDa (arrow) besides the usual ∼98 kDa APP band(s) only for the two mutants, where His149 and His151 were simultaneously mutated (alone or with His147) when compared with WT-APP. B, analogous examination of the same cell lysates but under standard conditions (plus βME sample buffer) highlighted the absence of the ∼188 kDa bands for both H149N/H151N- and H147N/H149N/H151N-APP, indicating that these two mutants form disulfide-linked oligomers.

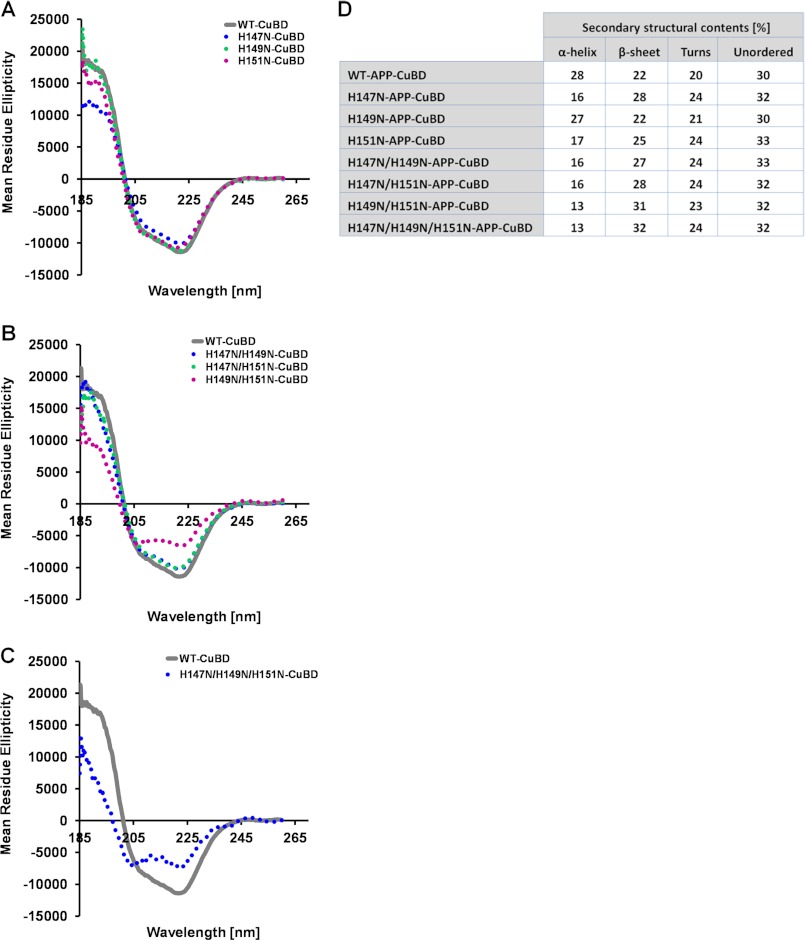

Co-mutation of His149 and His151 Causes APP CuBD Secondary Structure Changes

To determine if the histidine mutations could alter the APP structure, we analyzed the secondary structure of recombinantly expressed mutant APP CuBD 133–189. The far UV CD spectra of WT-CuBD indicated a mixture of α-helical and β-sheet conformations (Fig. 11, A–C) in line with the known structure (26, 27). Visual comparison with the WT-CuBD spectrum suggested that only H149N/H151N and H147N/H149N/H151N mutations caused a significant reduction in CuBD secondary structure elements, whereas the other mutations (H147N, H149N, H151N, H147/149N, and H147/151N) did not produce any discernable spectral changes (Fig. 11, A–C). However, deconvolution of the spectra indicated changes in α-helix and β-sheet structure for all of the mutants except H149N-CuBD (Fig. 11D). Deconvolution of CD spectra must be interpreted with caution because the deconvolution values can differ significantly from measured values. For instance, deconvolution of the WT-APP CD spectrum indicated 28 and 22% α-helical and β-sheet-like contributions (20% turns and 30% unordered) (Fig. 11D), which was discordant with the NMR and crystallography data showing 20% helical content and 32% β-sheet content (26, 27). Nevertheless, both visual inspection and deconvolution analysis suggested a significant change in secondary structure of H149N/H151N- and H147N/H149N/H151N-CuBD compared with WT-CuBD. These findings supported APP misfolding as the cause of the strong impairment in APP maturation and aberrant APP oligomerization observed when His149 and His151 were co-mutated and expressed in cell lines.

FIGURE 11.

Co-mutation of His149 and His151 causes APP CuBD secondary structure changes. Comparison of far-UV CD spectra of single (A), double (B), and triple (C) APP CuBD mutants to the WT-CuBD indicated a significant change in CuBD secondary structure caused by H149N/H151N and H147N/H149N/H151N mutations. D, table listing the secondary structure content of CuBD WT and mutants obtained by CD spectra deconvolution.

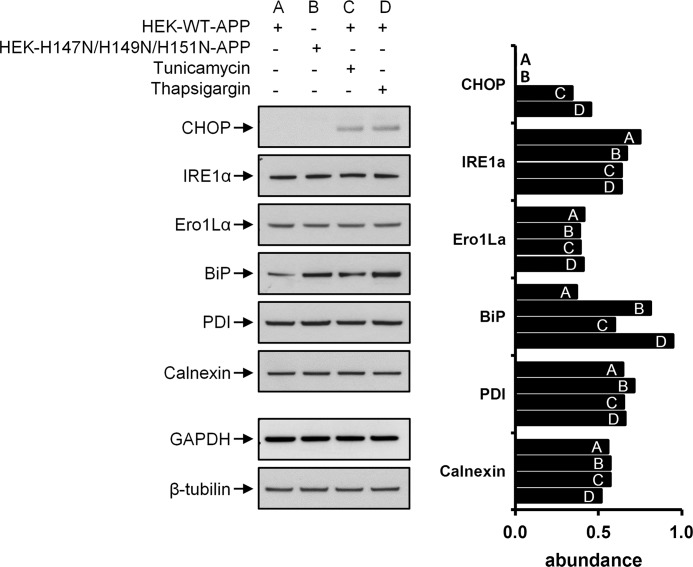

H147N/H149N/H151N-APP-HEK Cells Have Up-regulated Unfolded Protein Response

When the ER is stressed by accumulation of misfolded proteins, it activates the unfolded protein response (UPR) to restore normal homeostasis. To determine whether APP misfolding could be the cause of aberrant APP oligomerization, we analyzed the expression of calnexin, PDI, BiP, Ero1Lα, IRE1α and CHOP, components of the UPR (49). BiP and CHOP exhibited increased levels under the ER stress-induced conditions (Fig. 12), in accordance with the past literature (note that CHOP expression was not detectable under normal conditions, where its value was zero). The increase in BiP levels was more pronounced when thapsigargin was used instead of tunicamycin, possibly due to the different mode of action of these two ER stressors. BiP levels were higher in the H147N/H149N/H151N-APP-HEK compared with WT-APP-HEK, supporting the presence of misfolded and aberrantly oligomerized H147N/H149N/H151N-APP in the ER, causing ER stress. The H147N/H149N/H151N-APP-mediated ER stress might be milder compared with that induced by tunicamycin or thapsigargin and thus not activating the CHOP apoptosis pathway. Data showing similar viability levels between WT- and H147N/H149N/H151N-APP-HEK supported this hypothesis.

FIGURE 12.

UPR is partially up-regulated in H147N/H149N/H151N-APP-HEK cells. Immunoblot analysis of six ER stress and UPR markers and the corresponding densitometries indicated that CHOP and BiP abundances increased as a response of triggered ER stress in WT-APP-HEK (tunicamycin (1 μg/ml) or thapsigargin (300 nm) 5-h treatment). BiP abundance was also increased in untreated H147N/H149N/H151N-APP-HEK cells compared with WT-APP-HEK cells, supporting the putative presence of unfolded APPs and APP oligomers, both retained in the ER, upon this mutation. Values were standardized against a corresponding housekeeping gene (GAPDH for IRE1α, Ero1Lα, BiP, PDI, and calnexin and β-tubulin for CHOP).

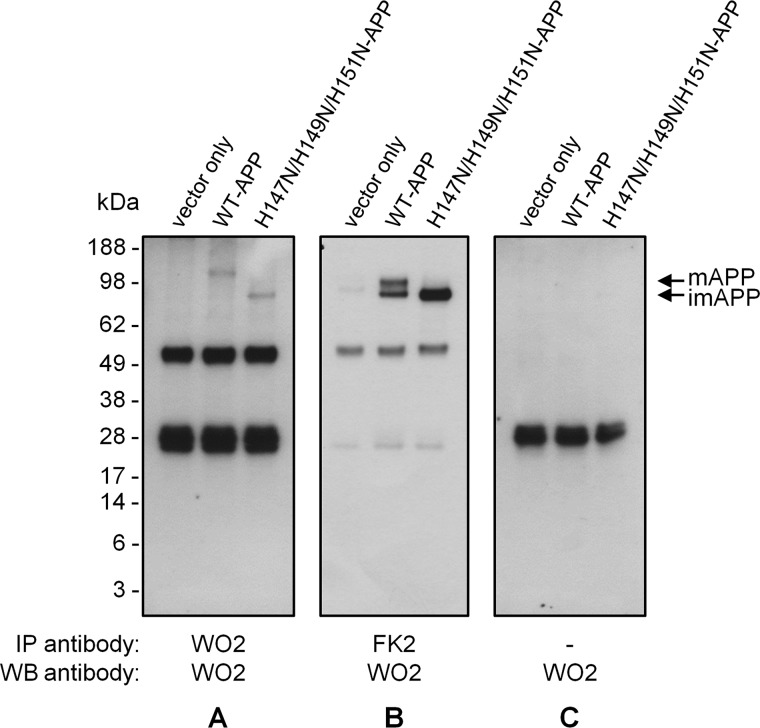

ER-associated degradation is also part of the UPR and involves recognizing of misfolded proteins, their retrotranslocation to the cytoplasm, and degradation by the proteasome following their ubiquitination. The H147N/H149N/H151N-APP ubiquitination state was examined by immunoprecipitation with the FK2 antibody, which recognizes ubiquitinylated proteins. Following Western blot analysis, a band corresponding to APP (i.e. around 98 kDa) was detected for WT-APP as well as for H147N/H149N/H151N-APP upon FK2 immunoprecipitation followed by WO2 immunoblotting (Fig. 13A). The former corresponded to mature APP, and the latter corresponded to imAPP, indicating that only imAPP bearing the H147N/H149N/H151N mutation, and not WT-imAPP, is ubiquitinated. These findings supported the theory that H147N/H149N/H151N mutation causes APP misfolding and shed some light on the fate of this non-functional APP mutant.

FIGURE 13.

H147N/H149N/H151N-imAPP is overubiquitinated compared with WT-imAPP. Cell lysates of HEK293 cells stably expressing WT- or H147N/H149N/H151N-APP or the vector alone were immunoprecipitated (IP) and immunoblotted (WB) with WO2 antibody. A, FK2 antibody (which recognizes polyubiquitin and monoubiquitin conjugates) immunoprecipitation showed that only imAPP bearing the H147N/H149N/H151N mutation (not WT-imAPP) is ubiquitinated. B, positive control. WO2 antibody immunoprecipitation showed the usual doublet for WT-APP and only one band for H147N/H149N/H151N-APP. C, negative control. Mock immunoprecipitation only showed nonspecific bands. Note that blots in A and C are a result of longer signal time collection than the blot in B.

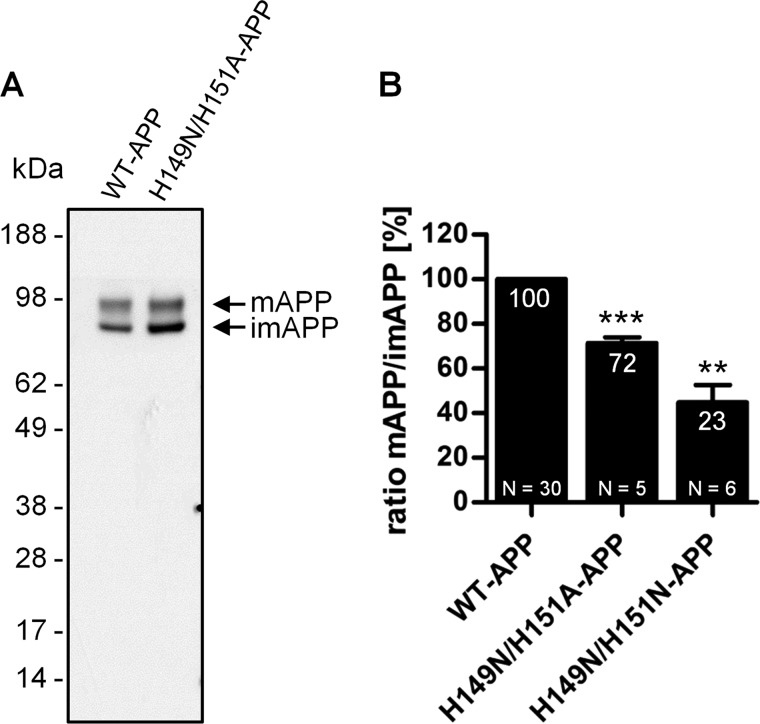

Co-mutating His149 and His151 to Alanine Only Mildly Impairs APP Maturation in HEK293 Cells

To assess whether the removal of the histidine residues or the specific incorporation of asparagine residues plays a role in destabilizing the APP structure, His149 and His151 were mutated to alanine, and APP maturation was investigated. Asparagine residues are infrequently found in helical structures and are considered a moderate α-helix breaker residue because their side chain disrupts the backbone hydrogen bonds that stabilize the helix (50). On the contrary, alanine occurs frequently in helix structures and is thought to promote helix formation (51–54). Similarly to asparagines, alanines have lower hydrogen bonding properties compared with histidine residues due to the lack of the imidazole ring. H149A/H151A-APP-HEK cells were analyzed by Western blot and densitometry as performed previously for the other histidine mutants (Fig. 14A). The H149A/H151A mutation decreased the m/imAPP ratio by ∼30% when compared with WT-APP, significantly less than the corresponding asparagine mutation (H149N/H151N), which reduced the ratio by ∼80% (Fig. 14B). These data suggested that replacement of His149 and His151 with asparagine residues might impair APP maturation through additive effects, possibly by hampering important intra- or intermolecular hydrogen bond formation and by disrupting the helix structure.

FIGURE 14.

Co-mutation of His149 and His151 to alanine only mildly impairs APP maturation in HEK293 cells. A, HEK293 cells stably overexpressing WT-APP or H149A/H151A-APP mutant were cultured under standard conditions. Cell lysates were normalized to total protein concentration levels before SDS-PAGE. The WO2 antibody was used to detect intracellular full-length APP, and the arrows indicate bands corresponding to mAPP and imAPP. B, the ratio of the mature over the immature APP levels was calculated and expressed as a percentage relative to that of WT-APP (100%). H149N/H151N-APP data from Fig. 3B were included for comparison. Data are expressed as mean ± S.E. (error bars). N indicates the number of times the experiment was performed. Statistical significance values were calculated with one-way ANOVA using Tukey's post hoc test. **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we discovered a role in APP metabolism for the two APP CuBD histidine residues located at positions 149 and 151. The secreted levels of Aβ and sAPPα were decreased in HEK293 cells overexpressing APP bearing substitutions of His147, His149, and His151 with asparagine. Mutation of His149 and His151, but not His147, decreased the m/imAPP ratio too. In particular, the impairment in mAPP maturation was notably stronger when these two residues were co-mutated. Subcellular fractionation and confocal immunofluorescence microscopy analysis suggested that ER-to-Golgi trafficking of APP bearing His149 and His151 mutations was hampered, accounting for the impairment of APP maturation. The co-mutation of His149 and His151, but not their individual mutations, led to aberrant APP oligomerization. Moreover, the secondary structure of the CuBD was altered by the co-mutation of His149 and His151, and HEK293 cells stably overexpressing the H147N/H149N/H151N-APP mutant exhibited abnormal up-regulated UPR. Our data suggest that His149 and His151 residues are important for APP folding because their co-mutation to asparagine causes APP misfolding and consequent aberrant APP oligomerization, resulting in APP retention in the ER and impaired APP maturation. The milder impairment of APP maturation when His149 and His151 were replaced with alanine (∼30%) compared with when mutated to asparagines (∼80%) suggested that both different hydrogen bonding properties and helix destabilizing characteristics of asparagine residues (compared with histidines) may contribute to the presumed APP misfolding. The single mutation of His149 or His151 did not cause any detectable aberrant APP oligomerization or significantly alter the secondary structure; however, it did impair APP maturation and ER to Golgi trafficking, indicating a mechanism similar to but milder than the one presumably underlying the His149 and His151 co-mutation phenotype.

His149 and His151 appear to have the same crucial role in stabilizing APP folding; however, this common function might be achieved through two different mechanisms for each residue, respectively. Protein-metal binding can promote and stabilize protein folding (55, 56); therefore, whereas conservation of His149 might promote and maintain the tertiary structure through hydrogen bonding and stabilization of the helix, His151 might contribute to APP folding stability via copper binding. Nevertheless, except for small changes in the position and orientation of the putative binding residues, no alteration in the CuBD structure was observed upon copper binding (26, 27), suggesting that metal interactions do not influence the overall folding of the domain. Structural studies employing the whole E1 domain of APP (including the CuBD and the growth factor domain) (57) do not provide any information on the influence of copper binding in E1 domain folding because they were performed with the apo form of the E1 domain.

His149 and His151 mutations not only impaired APP ER-to Golgi trafficking but, in some cases, also altered the levels of intracellular sAPPα and secreted sAPPα, sAPPβ, and Aβ. These changes were not specific to the extent of impairment in APP maturation, thus adding a further degree of complexity to the interpretation of the mechanisms of action of these mutations. Events other than APP ER-to-Golgi trafficking appear to cooperatively contribute to the generation of various intracellular and secreted APP metabolites.

Because the H147N mutation did not alter APP maturation, we assume that ER-to-Golgi trafficking of this mutant is unaffected. However, the reduction in secreted Aβ, sAPPα, and sAPPβ levels indicate that the transport of H147N-APP through the post-Golgi organelles might be hampered because this event would decrease plasma membrane APP levels and subsequently reduce secreted levels of APP metabolites. The raised intracellular sAPPα level is consistent with retention of H147N-APP within organelles where sAPPα is generated, such as the trans-Golgi network (48). An increase in the intrinsic propensity of H147N-APP to interact with α-secretase does not seem likely, due to the opposite alteration of intracellular versus secreted sAPPα levels.

Previous findings showed that copper increases APP cell surface localization (58) and promotes APP trafficking from the Golgi to intracellular compartments and to the cell surface (32). This supports H147N-APP decreased post-Golgi trafficking because His147 might be necessary for APP copper binding. Alternatively, His147 might be crucial in APP recognition for post-Golgi trafficking, and its mutations might decrease APP interactions to cofactors involved in APP post-Golgi transport, such as AP-4, sorLA, and Reelin (59–62). Finally, H147N mutation might affect copper reduction rather than copper binding, as demonstrated by earlier studies employing synthetic peptides encompassing APP residues 135–156 (28, 29), and lead to a modulation of APP metabolism. The potential inability of APP to reduce copper might in fact influence APP trafficking.

In summary, this study identified a novel cellular process whereby His149 and His151 residues in the APP CuBD regulate APP proteolytic processing by impairing APP ER to Golgi transport. This most likely occurs through promotion and stabilization of APP folding. The involvement of His149 in this modulation suggests a mechanism not involving copper binding; however, modulation of APP folding by His151 via APP binding to copper cannot be excluded. The findings of this study indicate a novel and additional role of the CuBD in APP folding and stability, besides the canonical function of copper binding, and contribute to the elucidation of the role of APP CuBD in modulating APP metabolism. Strategic APP misfolding and retention in the ER might be used therapeutically in order to reduce Aβ generation; however, this approach presents the caveat of suppressing potentially beneficial APP metabolites (such as sAPPα) and the accumulation of unfolded protein in the ER. Nevertheless, these findings contribute to understanding the normal physiological role of APP and might be useful in identifying crucial residues and interactions that should not be perturbed in the design of novel therapeutic strategies for AD that target the APP CuBD.

This work was supported by grants from the Australian Research Council and the National Health and Medical Research Council.

- APP

- amyloid precursor protein

- mAPP

- mature APP

- imAPP

- immature APP

- m/imAPP

- mature/immature APP ratio

- sAPP

- secreted APP

- Aβ

- amyloid β peptide

- ER

- endoplasmic reticulum

- CuBD

- copper binding domain

- HEK

- human embryonic kidney

- BFA

- brefeldin A

- βME

- β-mercaptoethanol

- UPR

- unfolded protein response

- ANOVA

- analysis of variance.

REFERENCES

- 1. Påhlsson P., Spitalnik S. L. (1996) The role of glycosylation in synthesis and secretion of β-amyloid precursor protein by Chinese hamster ovary cells. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 331, 177–186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Sodhi C. P., Perez R. G., Gottardi-Littell N. R. (2008) Phosphorylation of β-amyloid precursor protein (APP) cytoplasmic tail facilitates amyloidogenic processing during apoptosis. Brain Res. 1198, 204–212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Weidemann A., König G., Bunke D., Fischer P., Salbaum J. M., Masters C. L., Beyreuther K. (1989) Identification, biogenesis, and localization of precursors of Alzheimer disease A4 amyloid protein. Cell 57, 115–126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Koo E. H., Squazzo S. L., Selkoe D. J., Koo C. H. (1996) Trafficking of cell surface amyloid β-protein precursor. I. Secretion, endocytosis, and recycling as detected by labeled monoclonal antibody. J. Cell Sci. 109, 991–998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Lichtenthaler S. F. (2011) α-Secretase in Alzheimer disease. Molecular identity, regulation and therapeutic potential. J. Neurochem. 116, 10–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Seubert P., Oltersdorf T., Lee M. G., Barbour R., Blomquist C., Davis D. L., Bryant K., Fritz L. C., Galasko D., Thal L. J. (1993) Secretion of β-amyloid precursor protein cleaved at the amino terminus of the β-amyloid peptide. Nature 361, 260–263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Gabuzda D., Busciglio J., Chen L. B., Matsudaira P., Yankner B. A. (1994) Inhibition of energy metabolism alters the processing of amyloid precursor protein and induces a potentially amyloidogenic derivative. J. Biol. Chem. 269, 13623–13628 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Anderson J. P., Chen Y., Kim K. S., Robakis N. K. (1992) An alternative secretase cleavage produces soluble Alzheimer amyloid precursor protein containing a potentially amyloidogenic sequence. J. Neurochem. 59, 2328–2331 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Haass C., Schlossmacher M. G., Hung A. Y., Vigo-Pelfrey C., Mellon A., Ostaszewski B. L., Lieberburg I., Koo E. H., Schenk D., Teplow D. B. (1992) Amyloid β-peptide is produced by cultured cells during normal metabolism. Nature 359, 322–325 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Seubert P., Vigo-Pelfrey C., Esch F., Lee M., Dovey H., Davis D., Sinha S., Schlossmacher M., Whaley J., Swindlehurst C. (1992) Isolation and quantification of soluble Alzheimer β-peptide from biological fluids. Nature 359, 325–327 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Shoji M., Golde T. E., Ghiso J., Cheung T. T., Estus S., Shaffer L. M., Cai X. D., McKay D. M., Tintner R., Frangione B. (1992) Production of the Alzheimer amyloid β protein by normal proteolytic processing. Science 258, 126–129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Esch F. S., Keim P. S., Beattie E. C., Blacher R. W., Culwell A. R., Oltersdorf T., McClure D., Ward P. J. (1990) Cleavage of amyloid β peptide during constitutive processing of its precursor. Science 248, 1122–1124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Sisodia S. S. (1992) β-Amyloid precursor protein cleavage by a membrane-bound protease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 89, 6075–6079 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Haass C., Hung A. Y., Schlossmacher M. G., Teplow D. B., Selkoe D. J. (1993) β-Amyloid peptide and a 3-kDa fragment are derived by distinct cellular mechanisms. J. Biol. Chem. 268, 3021–3024 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Vitek M. P. (1989) Increasing amyloid peptide precursor production and its impact on Alzheimer disease. Neurobiol. Aging 10, 471–473; discussion 477–478 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Clark A. W., Parhad I. M. (1989) Expression of neuronal mRNAs in Alzheimer type degeneration of the nervous system. Can J. Neurol. Sci. 16, 477–482 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Cohen M. L., Golde T. E., Usiak M. F., Younkin L. H., Younkin S. G. (1988) In situ hybridization of nucleus basalis neurons shows increased β-amyloid mRNA in Alzheimer disease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 85, 1227–1231 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Preece P., Virley D. J., Costandi M., Coombes R., Moss S. J., Mudge A. W., Jazin E., Cairns N. J. (2004) Amyloid precursor protein mRNA levels in Alzheimer disease brain. Brain Res. Mol. Brain Res. 122, 1–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Basun H., Forssell L. G., Wetterberg L., Winblad B. (1991) Metals and trace elements in plasma and cerebrospinal fluid in normal aging and Alzheimer disease. J. Neural. Transm. Park Dis. Dement. Sect. 3, 231–258 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Deibel M. A., Ehmann W. D., Markesbery W. R. (1996) Copper, iron, and zinc imbalances in severely degenerated brain regions in Alzheimer disease. Possible relation to oxidative stress. J. Neurol. Sci. 143, 137–142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lovell M. A., Robertson J. D., Teesdale W. J., Campbell J. L., Markesbery W. R. (1998) Copper, iron, and zinc in Alzheimer disease senile plaques. J. Neurol. Sci. 158, 47–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Squitti R., Cassetta E., Dal Forno G., Lupoi D., Lippolis G., Pauri F., Vernieri F., Cappa A., Rossini P. M. (2004) Copper perturbation in two monozygotic twins discordant for degree of cognitive impairment. Arch. Neurol. 61, 738–743 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Squitti R., Lupoi D., Pasqualetti P., Dal Forno G., Vernieri F., Chiovenda P., Rossi L., Cortesi M., Cassetta E., Rossini P. M. (2002) Elevation of serum copper levels in Alzheimer disease. Neurology 59, 1153–1161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Bayer T. A., Schäfer S., Simons A., Kemmling A., Kamer T., Tepest R., Eckert A., Schüssel K., Eikenberg O., Sturchler-Pierrat C., Abramowski D., Staufenbiel M., Multhaup G. (2003) Dietary copper stabilizes brain superoxide dismutase 1 activity and reduces amyloid Aβ production in APP23 transgenic mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 100, 14187–14192 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Phinney A. L., Drisaldi B., Schmidt S. D., Lugowski S., Coronado V., Liang Y., Horne P., Yang J., Sekoulidis J., Coomaraswamy J., Chishti M. A., Cox D. W., Mathews P. M., Nixon R. A., Carlson G. A., St George-Hyslop P., Westaway D. (2003) In vivo reduction of amyloid β by a mutant copper transporter. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 100, 14193–14198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Barnham K. J., McKinstry W. J., Multhaup G., Galatis D., Morton C. J., Curtain C. C., Williamson N. A., White A. R., Hinds M. G., Norton R. S., Beyreuther K., Masters C. L., Parker M. W., Cappai R. (2003) Structure of the Alzheimer disease amyloid precursor protein copper binding domain. A regulator of neuronal copper homeostasis. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 17401–17407 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kong G. K., Adams J. J., Harris H. H., Boas J. F., Curtain C. C., Galatis D., Masters C. L., Barnham K. J., McKinstry W. J., Cappai R., Parker M. W. (2007) Structural studies of the Alzheimer amyloid precursor protein copper-binding domain reveal how it binds copper ions. J. Mol. Biol. 367, 148–161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Multhaup G., Schlicksupp A., Hesse L., Beher D., Ruppert T., Masters C. L., Beyreuther K. (1996) The amyloid precursor protein of Alzheimer disease in the reduction of Cu(II) to Cu(I) Science 271, 1406–1409 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Hesse L., Beher D., Masters C. L., Multhaup G. (1994) The β A4 amyloid precursor protein binding to copper. FEBS Lett. 349, 109–116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Armendariz A. D., Gonzalez M., Loguinov A. V., Vulpe C. D. (2004) Gene expression profiling in chronic copper overload reveals up-regulation of Prnp and App. Physiol. Genomics 20, 45–54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Borchardt T., Camakaris J., Cappai R., Masters C. L., Beyreuther K., Multhaup G. (1999) Copper inhibits β-amyloid production and stimulates the non-amyloidogenic pathway of amyloid precursor protein secretion. Biochem. J. 344, 461–467 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Acevedo K. M., Hung Y. H., Dalziel A. H., Li Q. X., Laughton K., Wikhe K., Rembach A., Roberts B., Masters C. L., Bush A. I., Camakaris J. (2011) Copper promotes the trafficking of the amyloid precursor protein. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 8252–8262 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Bellingham S. A., Lahiri D. K., Maloney B., La Fontaine S., Multhaup G., Camakaris J. (2004) Copper depletion down-regulates expression of the Alzheimer disease amyloid β precursor protein gene. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 20378–20386 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Cater M. A., McInnes K. T., Li Q. X., Volitakis I., La Fontaine S., Mercer J. F., Bush A. I. (2008) Intracellular copper deficiency increases amyloid β secretion by diverse mechanisms. Biochem. J. 412, 141–152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Bellingham S. A., Ciccotosto G. D., Needham B. E., Fodero L. R., White A. R., Masters C. L., Cappai R., Camakaris J. (2004) Gene knockout of amyloid precursor protein and amyloid precursor-like protein-2 increases cellular copper levels in primary mouse cortical neurons and embryonic fibroblasts. J. Neurochem. 91, 423–428 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. White A. R., Reyes R., Mercer J. F., Camakaris J., Zheng H., Bush A. I., Multhaup G., Beyreuther K., Masters C. L., Cappai R. (1999) Copper levels are increased in the cerebral cortex and liver of APP and APLP2 knockout mice. Brain Res. 842, 439–444 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Ida N., Hartmann T., Pantel J., Schröder J., Zerfass R., Förstl H., Sandbrink R., Masters C. L., Beyreuther K. (1996) Analysis of heterogeneous A4 peptides in human cerebrospinal fluid and blood by a newly developed sensitive Western blot assay. J. Biol. Chem. 271, 22908–22914 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Kong G. K., Galatis D., Barnham K. J., Polekhina G., Adams J. J., Masters C. L., Cappai R., Parker M. W., McKinstry W. J. (2005) Crystallization and preliminary crystallographic studies of the copper-binding domain of the amyloid precursor protein of Alzheimer disease. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. F Struct. Biol. Cryst. Commun. 61, 93–95 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Sreerama N., Woody R. W. (2000) Estimation of protein secondary structure from circular dichroism spectra: comparison of CONTIN, SELCON, and CDSSTR methods with an expanded reference set. Anal. Biochem. 287, 252–260 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Manavalan P., Johnson W. C., Jr. (1987) Variable selection method improves the prediction of protein secondary structure from circular dichroism spectra. Anal. Biochem. 167, 76–85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Compton L. A., Johnson W. C., Jr. (1986) Analysis of protein circular dichroism spectra for secondary structure using a simple matrix multiplication. Anal. Biochem. 155, 155–167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Whitmore L., Wallace B. A. (2008) Protein secondary structure analyses from circular dichroism spectroscopy. Methods and reference databases. Biopolymers 89, 392–400 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Koradi R., Billeter M., Wuthrich K. (1996) MOLMOL. A program for display and analysis of macromolecular structures. J. Mol. Graph. 14, 51–55, 29–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Sciaky N., Presley J., Smith C., Zaal K. J., Cole N., Moreira J. E., Terasaki M., Siggia E., Lippincott-Schwartz J. (1997) Golgi tubule traffic and the effects of brefeldin A visualized in living cells. J. Cell Biol. 139, 1137–1155 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Chege N. W., Pfeffer S. R. (1990) Compartmentation of the Golgi complex. Brefeldin-A distinguishes trans-Golgi cisternae from the trans-Golgi network. J. Cell Biol. 111, 893–899 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Ladinsky M. S., Howell K. E. (1992) The trans-Golgi network can be dissected structurally and functionally from the cisternae of the Golgi complex by brefeldin A. Eur. J. Cell Biol. 59, 92–105 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Caporaso G. L., Gandy S. E., Buxbaum J. D., Greengard P. (1992) Chloroquine inhibits intracellular degradation but not secretion of Alzheimer β/A4 amyloid precursor protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 89, 2252–2256 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Skovronsky D. M., Moore D. B., Milla M. E., Doms R. W., Lee V. M. (2000) Protein kinase C-dependent α-secretase competes with β-secretase for cleavage of amyloid-β precursor protein in the trans-Golgi network. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 2568–2575 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Kapoor A., Sanyal A. J. (2009) Endoplasmic reticulum stress and the unfolded protein response. Clin. Liver Dis. 13, 581–590 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Berg J. M., Stryer L., Tymocozko J. L. (2002) The amino acid sequence of a protein determines its three-dimensional structure. in Biochemistry, 5th Ed., pp. 64–70, W. H. Freeman and Co., New York [Google Scholar]

- 51. Marqusee S., Baldwin R. L. (1987) Helix stabilization by Glu− … Lys+ salt bridges in short peptides of de novo design. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 84, 8898–8902 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Merutka G., Stellwagen E. (1989) Analysis of peptides for helical prediction. Biochemistry 28, 352–357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Shoemaker K. R., Kim P. S., Brems D. N., Marqusee S., York E. J., Chaiken I. M., Stewart J. M., Baldwin R. L. (1985) Nature of the charged group effect on the stability of the C-peptide helix. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 82, 2349–2353 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Lyu P. C., Liff M. I., Marky L. A., Kallenbach N. R. (1990) Side chain contributions to the stability of α-helical structure in peptides. Science 250, 669–673 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Low L. Y., Hernández H., Robinson C. V., O'Brien R., Grossmann J. G., Ladbury J. E., Luisi B. (2002) Metal-dependent folding and stability of nuclear hormone receptor DNA-binding domains. J. Mol. Biol. 319, 87–106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Botelho H. M., Koch M., Fritz G., Gomes C. M. (2009) Metal ions modulate the folding and stability of the tumor suppressor protein S100A2. FEBS J. 276, 1776–1786 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Dahms S. O., Hoefgen S., Roeser D., Schlott B., Guhrs K. H., Than M. E. (2010) Structure and biochemical analysis of the heparin-induced E1 dimer of the amyloid precursor protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 5381–5386 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Hung Y. H., Robb E. L., Volitakis I., Ho M., Evin G., Li Q. X., Culvenor J. G., Masters C. L., Cherny R. A., Bush A. I. (2009) Paradoxical condensation of copper with elevated β-amyloid in lipid rafts under cellular copper deficiency conditions. Implications for Alzheimer disease. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 21899–21907 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Andersen O. M., Schmidt V., Spoelgen R., Gliemann J., Behlke J., Galatis D., McKinstry W. J., Parker M. W., Masters C. L., Hyman B. T., Cappai R., Willnow T. E. (2006) Molecular dissection of the interaction between amyloid precursor protein and its neuronal trafficking receptor SorLA/LR11. Biochemistry 45, 2618–2628 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Burgos P. V., Mardones G. A., Rojas A. L., daSilva L. L., Prabhu Y., Hurley J. H., Bonifacino J. S. (2010) Sorting of the Alzheimer disease amyloid precursor protein mediated by the AP-4 complex. Dev. Cell 18, 425–436 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Hoe H. S., Lee K. J., Carney R. S., Lee J., Markova A., Lee J. Y., Howell B. W., Hyman B. T., Pak D. T., Bu G., Rebeck G. W. (2009) Interaction of reelin with amyloid precursor protein promotes neurite outgrowth. J. Neurosci. 29, 7459–7473 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Spoelgen R., von Arnim C. A., Thomas A. V., Peltan I. D., Koker M., Deng A., Irizarry M. C., Andersen O. M., Willnow T. E., Hyman B. T. (2006) Interaction of the cytosolic domains of sorLA/LR11 with the amyloid precursor protein (APP) and β-secretase β-site APP-cleaving enzyme. J. Neurosci. 26, 418–428 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]