Background: Transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) plays crucial regulatory roles in the immune homeostasis.

Results: Leukocyte function-associated antigen-1 (LFA-1) stimulation induces a genetic signature in T-cells, resulting in their refractoriness to TGF-β signaling.

Conclusion: T-cells stimulated via LFA-1 are programmed to become refractory to TGF-β functions.

Significance: Findings are important for understanding local inflammatory response and in designing immunotherapies.

Keywords: Gene Regulation, Immunology, Integrin, Lymphocyte, Transforming Growth Factor Beta (TGFbeta)

Abstract

The immunesuppressive cytokine TGF-β plays crucial regulatory roles in the induction and maintenance of immunologic tolerance and prevention of immunopathologies. However, it remains unclear how circulating T-cells can escape from the quiescent state maintained by TGF-β. Here, we report that the T-cell integrin leukocyte function-associated antigen-1 (LFA-1) interaction with its ligand intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1) induces a genetic signature associated with reduced TGF-β responsiveness via up-regulation of SKI, E3 ubiquitin-protein ligase SMURF2, and SMAD7 (mothers against decapentaplegic homolog 7) genes and proteins. We confirmed that the expression of these TGF-β inhibitory molecules was dependent on STAT3 and/or JNK activation. Increased expression of SMAD7 and SMURF2 in LFA-1/ICAM-1 cross-linked T-cells resulted in impaired TGF-β-mediated phosphorylation of SMAD2 and suppression of IL-2 secretion. Expression of SKI caused resistance to TGF-β-mediated suppression of IL-2, but SMAD2 phosphorylation was unaffected. Blocking LFA-1 by neutralizing antibody or specific knockdown of TGF-β inhibitory molecules by siRNA substantially restored LFA-1/ICAM-1-mediated alteration in TGF-β signaling. LFA-1/ICAM-1-stimulated human and mouse T-cells were refractory to TGF-β-mediated induction of FOXP3+ (forkhead box P3) and RORγt+ (retinoic acid-related orphan nuclear receptor γt) Th17 differentiation. These mechanistic data suggest an important role for LFA-1/ICAM-1 interactions in immunoregulation concurrent with lymphocyte migration that may have implications at the level of local inflammatory response and for anti-LFA-1-based therapies.

Introduction

The multistep process of lymphocyte transmigration is crucial for an efficient immune response, and it is orchestrated by a multifunctional molecular array including integrin-mediated adhesions and chemokine signals (1). The leukocyte function-associated antigen-1 (LFA-1)3 integrin interacts with its ligand intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1), expressed on the surface of high endothelial venules and other cell types, and this interaction plays key signaling roles in the context of leukocyte adhesion, locomotion, and migration through endothelial junctions into the sites of inflammation (2). At the level of the immunological synapse, LFA-1 greatly increases the avidity of T-cells and antigen presenting cells (2, 3). At the point of transendothelial migration, lymphocytes are directed toward an ultimate effector phase of their expected activity at the site of inflammation downstream of the high endothelial venules. In this regard, LFA-1/ICAM-1 interactions can modulate the signal transduction pathways that control complex cell functions such as T-cell activation and differentiation, which require the regulation of gene expression.

We have previously shown that LFA-1 engagement in T-cells activates the transcription factor and adaptor protein STAT3 (4), whereas others have shown that such engagement activates c-Jun that forms the activator protein-1 (AP-1) transcriptional regulatory complex (3, 5, 6). In addition, STAT3 interacts with c-Jun and participates in cooperative transcriptional activation (7). These observations suggest that signaling through LFA-1 may affect downstream gene expression. Although extensive progress has been made in understanding the LFA-1 signaling at a post-translational level, detailed characterization of gene regulation by LFA-1/ICAM-1 interaction and its functional consequences in T-cells has not been explored to the similar extent. Moreover, the precise contribution of the LFA-1/ICAM-1 signaling to the enhanced extravasation capacity of effector T-cells at sites of inflammation has remained unclear.

A balance between pro- and anti-inflammatory mechanisms at the epithelial interfaces allows for efficient protection against pathogens yet preventing adverse inflammation. Central to the success of immune responses that restrain inflammation are regulatory cytokines, including a multifunctional cytokine TGF-β produced by immune and non-immune cells that controls a number of immunological functions, including T-cell development, homeostasis, proliferation, and differentiation (8–11). TGF-β signaling from the cell surface to the nucleus is mediated by the SMAD family of proteins that involves Ser/Thr phosphorylation of receptor-regulated SMAD2 and SMAD3 (12). This process is subject to many levels of positive and negative regulation by intracellular mediators. Among negative regulators of TGF-β signaling are SMAD7, SMURF2, SKI, and SnoN (12–14). The pleiotropic effects of TGF-β on various T-cell subsets are complex and context-dependent. TGF-β signaling prevents production of IL-2 by T-cells (15). Furthermore, TGF-β is a critical co-stimulatory factor in the differentiation of functional subsets of effector T helper 17 (Th17) cells as well as induced regulatory T-cells (iTregs) (8–11), which play pivotal roles in the control of immune homeostasis. Th17 cells are characterized by their expression of retinoic acid-related orphan receptor (RORγt) and production of proinflammatory cytokines, including IL-17, IL-6, and IL-21 (16). Th17 cells reside mainly at barrier surfaces, particularly the mucosa of the gut, where they function to protect the host from microorganisms that invade through the epithelium (16). The iTreg cells, which develop post-thymically are characterized by expression of the transcription factor FOXP3 (forkhead box protein P3), prevent tissue-specific autoimmunity and chronic inflammation (16, 17). The fact that the immunosuppressive cytokine TGF-β is expressed highly in lymphoid and extralymphoid organs and that constitutively active TGF-β signaling keeps circulating T-cells in a resting state brings about a fundamental question. How do circulating T-cells escape from the quiescent state maintained by TGF-β? In particular, it remains to be established whether LFA-1/ICAM-1-mediated signaling in T-cells has a functional involvement in these processes. Recent data from trials of monoclonal antibodies directed against LFA-1 in humans, as well as data from animal models, suggest that such therapies are associated not only with inhibition of migration but also with broad perturbations in T-cell functions, including activation, proliferation, and differentiation (18, 19).

The purpose of the current study was to determine whether there are changes in gene expression caused by LFA-1/ICAM-1 interactions, which could have an impact not only on the T-cell locomotory behavior but also in functional terms on the programming of the lymphocyte diapedesis through the high endothelial venules and ultimate effector function. To address these questions, we analyzed gene expression changes following the interaction of LFA-1 with ICAM-1 in T-cells using an Affymetrix microarray technique and a systems biology approach. We demonstrate that among the genes whose expression levels are altered predictably by LFA-1/ICAM-1 mediated signaling, several may have functions related to the turnover of molecules involved in the migration process. Additionally, however, a subset of genes associated with reduced TGF-β responsiveness is up-regulated which may have an impact on the overall T-cell effector programming. In this study, we specifically address the impact of such gene expression regulation by LFA-1/ICAM-1 interactions in T-cells, which results in their refractoriness to TGF-β in terms of effector functions.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Cells and Reagents

Human peripheral blood lymphocyte (PBL) T-cells from healthy volunteers purified by standard methods and the human T-cell line Hut78 (ATCC, Rockville, MI) were used. Human and mouse recombinant ICAM-1 and anti-human RORγt-APC antibody were from R&D Systems. LFA-1 blocking antibody, anti-CD4-FITC, and anti-FOXP3-PE were from BioLegend. Goat anti-human IgG (Fc-specific) and anti-α-tubulin antibodies were from Sigma. Rabbit anti-β-actin, HRP-conjugated anti-rabbit, and anti-mouse antibodies were from Cell Signaling Technology. Rabbit anti-SMAD7, anti-SMURF2, and anti-SKI were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. Cell-permeable AG490, STAT3-specific inhibitor peptide, and JNK inhibitor II SP600125 were from Merck Millipore.

LFA-1 Cross-linking with ICAM-1

T-cell LFA-1 cross-linking to the immobilized ICAM-1 was performed using our migration-triggering model system as described (20, 21). This well defined system allows LFA-1/ICAM-1 interactions to be examined in the absence of any other receptor-ligand interactions. Briefly, tissue culture plates (flat bottom, NuncTM) were pre-coated with goat anti-human Fc-specific IgG and subsequently with human recombinant ICAM-1 (1 μg/ml). Control plates were coated with 0.01% poly-l-lysine or 1% bovine serum albumin. Cells were loaded into the coated wells (60 × 104 cells/well in a six-well plate) and incubated in 5% CO2 at 37 °C.

Total RNA Extraction, DNA Microarray, and Data Analysis

Total RNA was isolated from the T-cell samples using a Nucleospin II kit (Macherey-Nagel) as per the manufacturer's instructions. For each sample, 10 μg of total RNA was in vitro-transcribed and biotin-labeled using the GeneChip 3′-IVT express kit (Affymetrix). Quality of cRNA was assessed using a 2100 Bioanalyser in combination with the RNA nano chips (Agilent Technologies). Biotin-labeled fragmented cRNA was hybridized to U133 plus arrays (version 2.0) for 16 h. The chips were then washed, stained, and scanned. Affymetrix arrays were run in duplicate. Data analysis was performed in GeneSpring GX (version 7.3.1; Agilent Technologies). CEL files containing the raw signal intensities for each probe set were imported into Genespring and were normalized using GeneChip Robust Multiarray Averaging. Genes were selected on the criteria that they had changed by >1.5 fold with a significant p value (<0.05) after multiple correction testing using Benjamin and Hochberg FDR test.

In Silico Analysis

Ingenuity Pathways Analysis (IPA) (Ingenuity Systems) was performed to better understand experimental data in relation to published research by identifying relationships, functions, and pathways of relevance. To generate biological networks, the final list of differentially expressed genes was uploaded into the IPA software as a tab-delimited text file of gene IDs. The network is displayed as nodes that represent genes and edges representing the interactions between genes. The “IPA Path Designer” was used to generate the final network. The transcription factor binding sites in the promoters of the identified genes was identified using Text Mining Application and UCSC Genome Browser from SABiosciences (22).

Quantitative Real-time PCR

DiRE (23) tool was used for promoter analysis and cDNA was generated using RETROscript qRT-PCR kit (Ambion). Real-time PCR was performed using 4.5 μl of diluted (1/50) reverse transcription reaction, TaqMan Universal PCR no AmpErase UNG master-mix, and specific gene primer set in a final volume of 10 μl in an ABI Prism 7700 thermocycler (Applied Biosystems). Relative quantification was performed using GAPDH as an internal control. Fold changes for each gene were calculated using the ΔΔCT method (24).

Cell Lysis and Western Immunoblotting

The cell lysis was performed as described previously (25). The protein content of the cell lysates was determined by Bradford assay. Sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis of the cellular lysates and subsequent Western immunoblotting were performed as described (25). Densitometric analyses of the Western blots were performed by using GeneTools software (Syngene). The relative values of the samples were determined by giving an arbitrary value of 1.0 to the respective control samples of each experiment (26).

Electroporation of T-cells

Hut78 T-cells were electroporated using BTX ECM830 electroporator as per our previously optimized protocol (27). Gene knockdown studies for the selected genes (human SMAD7, SMURF2, and SKI) were performed using SMARTpool® siRNA reagents (Dharmacon). For SMAD7 overexpression, cells were electroporated with an empty plasmid vector pcDNA3 or a construct FLAG-SMAD7 (a kind gift by professor Carl-Henrik Heldinm, Ludwig Institute for Cancer Research Ltd., Uppsala University, Uppsala, Sweden).

Human T-cell Differentiation and Functional Assay

Conversion of iTregs was performed as described (28) with minor modifications. Briefly, PBL T-cells were stimulated with anti-human CD3/CD28-coated beads at a bead-to-cell ratio of 1:5 in the presence of 20 ng/ml IL-2 ± 5 ng/ml TGF-β (both from Peprotech) for 5 days. For RORγt+ Th17 differentiation, PBL T-cells were stimulated with anti-CD3/CD28 in the presence of 40 ng/ml IL-6 (Peprotech) ± 5 ng/ml TGF-β for 4 days. For blocking IL-2 in Th17 cultures, anti-IL-2, anti-CD122, and anti-CD25 antibodies were added (10 ng/ml each). Anti-IFN-γ and anti-IL-4 antibodies were also added (10 ng/ml each) to block Th1 and Th2 differentiation, respectively. CD4+ cells expressing FOXP3 or RORγt were detected by corresponding immunostaining and a cell-based automated microscopy (IN Cell Analyzer 1000, GE Healthcare). The percentage of CD4+ cells expressing FOXP3 or RORγt was quantified using IN Cell Investigator software (GE Healthcare).

Mouse iTreg Differentiation and Analysis

Ex vivo induction of iTreg in mouse T-cells was performed using Foxp3-eGFP reporter mice on a C57BL/6J background (The Jackson Laboratory). All animal experiments were performed in compliance with Irish Department of Health and Children regulations and approved by the Trinity College Dublin's BioResources Ethical Review Board. A single cell suspension was prepared from spleens as described (29). CD4+ T-cells were purified using the CD4+ T-cell isolation kit (Miltenyi) and plated in 48-well plates at a concentration of 1.0 × 106 cells/ml with or without 3 μg/ml plate bound mouse recombinant ICAM-Fc. For induction of iTregs, cells were stimulated for 72 h with 1.0 μg/ml plate-bound anti-CD3, 5.0 μg/ml soluble anti-CD28, and 20 ng/ml IL-2 in the presence or absence of 5 ng/ml TGF-β1. Cells were stained with anti-CD4 Peridinin Chlorophyll Protein Comlex-conjugated mAb (BD Biosciences) and surface marker expression of eGFP-positive cells was assessed by the CyAn Flow Cytometer (Beckman Coulter) using FlowJo software (TreeStar). Dead cells were excluded on the basis of propidium iodide staining.

Cytokine Analysis

Secreted levels of IL-2 and IL-17 in T-cell culture supernatants were measured by human IL-2 DuoSet® ELISA (R&D Systems) and LEGEND MAXTM human IL-17A ELISA Kit (BioLegends) as per the manufacturer's instructions.

Statistical Analysis

The data are expressed as mean ± S.E. For comparison of two groups, p values were calculated by two-tailed unpaired student's t test. In all cases, p values < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

RESULTS

Analysis of Gene Regulation by LFA-1/ICAM-1-mediated Signaling in T-cells

We compared the effect of LFA-1/ICAM-1 triggering in T-cells by recording changes in transcription profiles by microarray analysis. Human T-cells were stimulated on the immobilized ICAM-1 for 1, 3, or 6 h, and total RNA was extracted. RNA samples from five independent biological replicates were analyzed by GeneChip Human Genome U133Plus2.0 Array (Affymetrix) with genome-wide coverage using ∼54,000 probe sets (>47,000 transcripts). Data analysis as described in “Experimental Procedures” was performed to identify differentially expressed genes, treatment clusters, and affected biological pathways. There were significant changes in the expression profile of a range of genes induced through the LFA-1/ICAM-1-mediated signal. We identified a total of 195 genes, of which 144 were significantly up-regulated, and 51 genes were repressed by the LFA-1 signal. The full list of differentially expressed genes with details on their molecular function is contained in supplemental Table 1. A list of significantly up- and down-regulated genes (top 40 genes in each category) is provided in Table 1 and Table 2, respectively.

TABLE 1.

The top 40 genes ranked by fold change identified as being up-regulated in T-cells following LFA-1/ICAM-1 interaction

| Probe ID | Symbol | Gene name | Fold change |

|---|---|---|---|

| 44783_s_at | HEY1 | Hairy/enhancer-of-split related with YRPW motif 1 | 56.82 |

| 222450_at | TMEPAI | Transmembrane, prostate, androgen-induced RNA | 48.92 |

| 217591_at | SKIL | SKI-like | 15.48 |

| 240156_at | RFX2 | Regulatory factor X, 2 | 13.84 |

| 235497_at | LOC643837 | Hypothetical protein LOC643837 | 13.55 |

| 229613_at | NKD1 | Naked cuticle 1 homolog (Drosophila) | 13.4 |

| 213506_at | F2RL1 | Coagulation factor II (thrombin) receptor-like 1 | 12.52 |

| 230820_at | SMURF2 | SMAD-specific E3 ubiquitin protein ligase 2 | 9.832 |

| 209574_s_at | C18orf1 | Chromosome 18 open reading frame 1 | 9.73 |

| 1560676_at | SIAH3 | Seven in absentia homolog 3 | 9.293 |

| 1556423_at | VASH1 | Vasohibin 1 | 9.273 |

| 212907_at | SLC30A1 | Solute carrier family 30 (zinc transporter), member 1 | 9.234 |

| 216297_at | BBIP1 | BBSome interacting protein 1 | 7.938 |

| 218793_s_at | SCML1 | Sex comb on mid leg-like protein 1 | 7.832 |

| 232081_at | ABCG1 | ATP-binding cassette, sub-family G (WHITE), member 1 | 7.69 |

| 212666_at | SMURF1 | SMAD-specific E3 ubiquitin protein ligase 1 | 6.71 |

| 209324_s_at | RGS16 | Regulator of G-protein signalling 16 | 6.355 |

| 204270_at | SKI | v-SKI sarcoma viral oncogene homolog (avian) | 6.186 |

| 204995_at | CDK5R1 | Cyclin-dependent kinase 5, regulatory subunit1 (p35) | 6.128 |

| 204790_at | SMAD7 | SMAD family member 7 | 5.911 |

| 225142_at | JHDM1D | Jumonji C domain containing histone demethylase 1 | 5.656 |

| 205977_s_at | EPHA1 | EPH receptor A1 | 5.258 |

| 212680_x_at | PPP1R14B | Protein phosphatase 1, regulatory (inhibitor) subunit 14B | 5.179 |

| 228067_at | C2orf55 | Chromosome 2 open reading frame 55 | 5.112 |

| 205016_at | TGFA | Transforming growth factor, α | 4.895 |

| 235851_s_at | GNAS | GNAS complex locus | 4.89 |

| 213629_x_at | MT1F | Metallothionein 1F (functional) | 4.877 |

| 220009_at | LONRF3 | LON peptidase N-terminal domain and ring finger 3 | 4.7 |

| 225481_at | FRMD6 | FERM domain containing 6 | 4.66 |

| 213060_s_at | CHI3L2 | Chitinase 3-like 2 | 4.64 |

| 216268_s_at | JAG1 | Jagged 1 | 4.51 |

| 1565525_a_at | TCP11L2 | t-Complex 11 (mouse)-like 2 | 4.464 |

| 213994_s_at | SPON1 | Spondin 1, extracellular matrix protein | 4.34 |

| 201389_at | ITGA5 | Integrin, α5 | 4.316 |

| 236241_at | MED31 | Mediator of RNA polymerase II transcription, subunit 31 | 4.225 |

| 203066_at | CHST15 | Carbohydrate sulfotransferase 15 | 4.199 |

| 223916_s_at | BCOR | BCL6 co-repressor | 4.141 |

| 231798_at | NOG | Noggin | 4.055 |

| 205899_at | CCNA1 | Cyclin A1 | 4.01 |

| 212582_at | OSBPL8 | Oxysterol binding protein-like 8 | 4 |

TABLE 2.

The top 40 genes ranked by fold change identified as being down-regulated in T-cells following LFA-1/ICAM-1 interaction

| Probe ID | Symbol | Gene name | Fold change |

|---|---|---|---|

| 205898_at | CX3CR1 | Chemokine (C-X3-C motif) receptor 1 | −17.92 |

| 1553681_a_at | PRF1 | Perforin1 (pore-forming protein) | −8.06 |

| 207651_at | GPR171 | G protein-coupled receptor 171 | −5.92 |

| 209840_s_at | LRRN3 | Leucine-rich repeat neuronal 3 | −5.81 |

| 1565566_a_at | STX7 | Syntaxin 7 | −5.41 |

| 207324_s_at | DSC1 | Desmocollin 1 | −5.03 |

| 207583_at | ABCD2 | ATP-binding cassette, subfamily D (ALD), member 2 | −4.93 |

| 206364_at | KIF14 | Kinesin family member 14 | −4.85 |

| 1569107_s_at | ZNF642 | Zinc finger protein 642 | −4.67 |

| 236226_at | BTLA | B and T lymphocyte-associated | −4.55 |

| 224414_s_at | CARD6 | Caspase recruitment domain family, member 6 | −4.48 |

| 202870_s_at | CDC20 | CDC20 cell division cycle 20 | −4.46 |

| 228057_at | DDIT4L | DNA damage-inducible transcript 4-like | −4.41 |

| 215894_at | PTGDR | Prostaglandin D2 receptor | −4.35 |

| 209773_s_at | RRM2 | Ribonucleotide reductase M2 polypeptide | −4.22 |

| 207761_s_at | METTL7A | Methyltransferase-like 7A | −4.18 |

| 244654_at | MYO1G | Myosin IG | −4.18 |

| 238581_at | GBP5 | Guanylate-binding protein 5 | −4.10 |

| 205467_at | CASP10 | Caspase-10, apoptosis-related cysteine peptidase | −4.08 |

| 202589_at | TYMS | Thymidylate synthetase | −4.00 |

| 218663_at | NCAP-G | Non-SMC condensin I complex, subunit G | −3.95 |

| 209714_s_at | CDKN3 | Cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 3 | −3.94 |

| 232375_at | STAT1 | Signal transducer and activator of transcription 1 | −3.70 |

| 201291_s_at | TOP2A | Topoisomerase (DNA) II α 170 kDa | −3.69 |

| 1563209_a_at | C20orf133 | Chromosome 20 open reading frame 133 | −3.57 |

| 226661_at | CDCA2 | Cell division cycle associated 2 | −3.55 |

| 208059_at | CCR8 | Chemokine (C-C motif) receptor 8 | −3.42 |

| 221969_at | PAX5 | Paired box gene5 (B-cell lineage-specific activator) | −3.41 |

| 224160_s_at | ACAD9 | Acyl-coenzyme A dehydrogenase family, member 9 | −3.33 |

| 202458_at | PRSS23 | Protease, serine, 23 | −3.29 |

| 228055_at | NAPSB | Napsin B aspartic peptidase | −3.27 |

| 219787_s_at | ECT2 | Epithelial cell transforming sequence 2 oncogene | −3.25 |

| 202269_x_at | GBP1 | Guanylate binding protein 1 | −3.11 |

| 215358_x_at | ZNF37B | Zinc finger protein 37b (KOX 21) | −3.11 |

| 205297_s_at | CD79B | CD79B antigen (immunoglobulin-associated β) | −2.81 |

| 220118_at | ZBTB32 | Zinc finger and BTB domain containing 32 | −2.77 |

| 235372_at | FCRLA | Fc receptor-like A | −2.75 |

| 226453_at | AYP1 | AYP1 protein | −2.7 |

| 226453_at | RNASEH2C | Ribonuclease H2, subunit C | −2.67 |

| 202531_at | IRF1 | Interferon regulatory factor 1 | −2.62 |

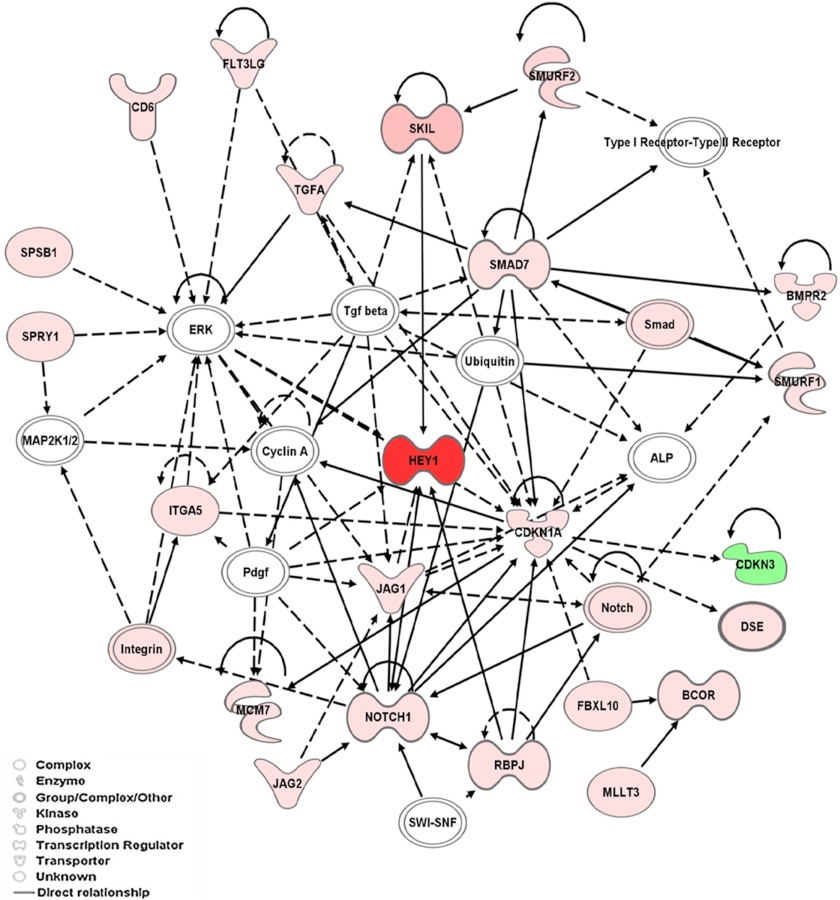

In silico analysis of the identified genes was performed to interrogate associated pathways and biological networks. We applied the Pathway-Express tool of Onto-Express (using the KEGG database) to identify cellular processes affected by the identified genes. Among the sets of genes involved in various pathways influenced by LFA-1/ICAM-1 interactions were those of the TGF-β pathway, along with the genes previously identified as being involved in axon guidance, ubiquitin-mediated proteolysis, and Notch signaling. Genes associated with TGF-β related pathways particularly induced by LFA-1/ICAM-1-mediated signal included SKIL (15.48-fold), SMURF2 (9.83-fold), SMURF1 (6.71-fold), and SMAD7 (5.91-fold) (Table 1). A biological network was generated by IPA using the Ingenuity Knowledge database that demonstrate a high level of interconnectivity among these genes in TGF-β-related pathways (Fig. 1). Moreover, molecules involved in Notch signaling, including NOTCH1, JAG1, JAG2, and HEY1, were connected directly or indirectly to the identified TGF-β pathway. Because TGF-β produced by both epithelial cells and regulatory T-cells plays crucial roles in modulating an effector T-cell program (8–11), we elected to focus on the TGF-β-related pathway for further verification and functional analysis.

FIGURE 1.

Network pathways analysis of molecules identified in T-cells that are involved in LFA-1/ICAM-1 signaling. Each network is displayed as nodes that represent genes, and edges represent the interactions between genes. The path designer mode was used to generate final network images. Molecules shaded in green indicate a 2-fold or greater decrease in abundance, molecules shaded in red correspond to a 2-fold or greater increase in T-cells following LFA-1/ICAM-1 interactions, and the color intensity corresponds to the degree of abundance. Molecules in white are those identified through the Ingenuity Pathway Knowledgebase. The shapes denote the molecular class of the gene products. A solid line indicates a direct molecular interaction, and a dashed line indicates an indirect molecular interaction.

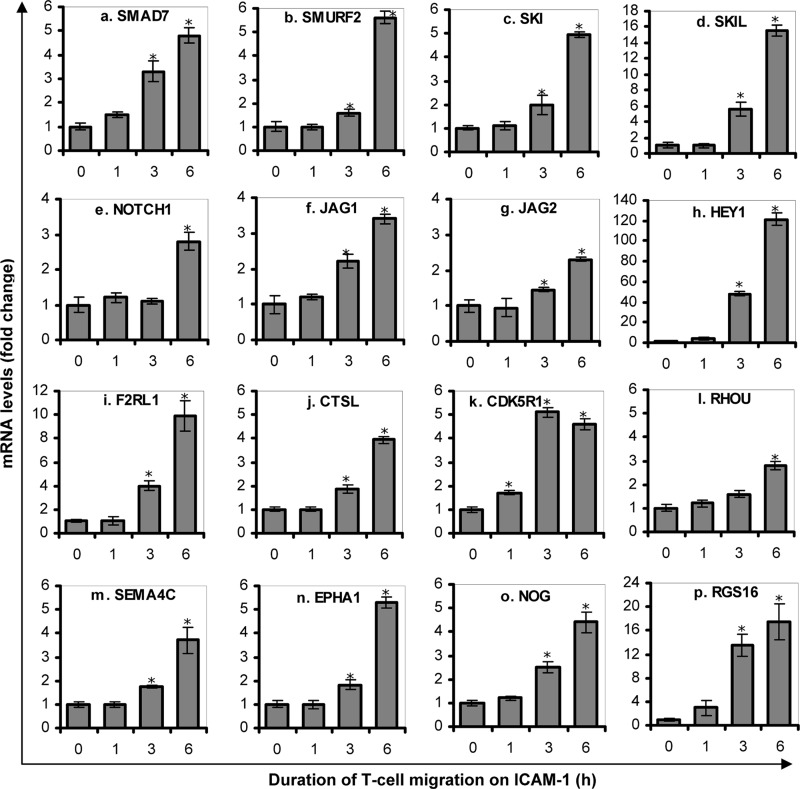

Confirmation of Microarray Data by qRT-PCR

To verify microarray data obtained from T-cells following LFA-1/ICAM-1 engagement, qRT-PCR analysis was conducted utilizing the same set of samples used for the microarray assay as well as RNA samples from independent experiments. Sixteen genes of interest (namely SMAD7, SMURF2, SKI, SKIL, NOTCH1, JAG1, JAG2, HEY1, F2RL1, CTSL, CDK5R1, RHOU, SEMA4C, EPHA1, NOG, and RGS16) with significant up-regulation were selected for qRT-PCR confirmation. Care was taken to include genes with weak (close to 2-fold) as well as strong changes (up to 50-fold) in RNA levels. qRT-PCR expression data (Fig. 2) were consistent with the results obtained by Affymetrix microarray (Table 1). Importantly, in accordance to microarray data, the mRNA levels of genes associated with the TGF-β pathway, namely SMAD7, SMURF2, SKI, and SKIL were up-regulated significantly by LFA-1/ICAM-1 signaling (Fig. 2, a–d). These results confirm a direct effect of LFA-1/ICAM-1-mediated signal on transcriptional regulation of genes involved in TGF-β signaling pathway.

FIGURE 2.

Validation of Affymatrix data for selected genes by qRT-PCR. PBL T-cells purified from healthy volunteers were incubated on ICAM-1-coated plates for 0 h (control), 1, 3, or 6 h. mRNA levels of SMAD7 (a), SMURF2 (b), SKI (c), SKIL (d), NOTCH1 (e), JAG1 (f), JAG2 (g), HEY1 (h), F2RL1 (i), CTSL (j), CDK5R1 (k), RHOU (l), SEMA4C (m), EPHA1 (n), NOG (o), and RGS16 (p) were measured by qRT-PCR. Data are fold change relative to GAPDH (mean ± S.E.) of three independent experiments. *, p < 0.05 with respect to corresponding controls.

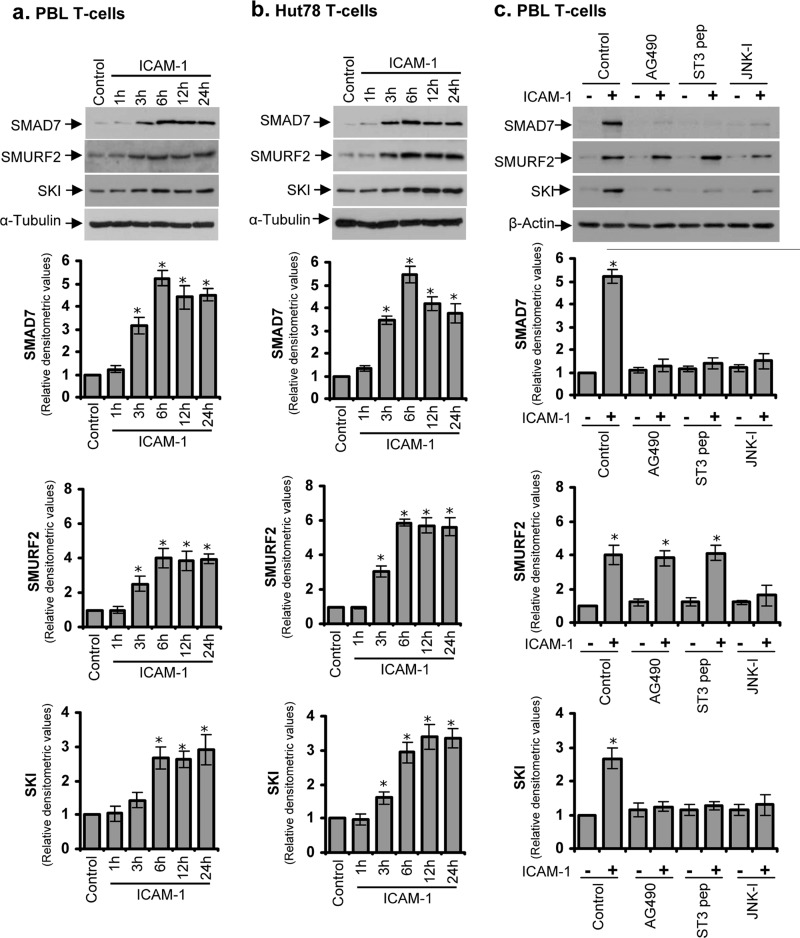

Up-regulation of TGF-β Signaling Proteins in LFA-1/ICAM-1-stimulated T-cells Is Mediated via STAT3 and/or JNK

Because SMAD7, SMURF2, and SKI proteins are known to play major roles in the TGF-β signal transduction pathway (12–14, 30–34), we chose to further validate their involvement in LFA-1/ICAM-1-mediated signaling. Western immunoblot analysis showed that expression levels of SMAD7, SMURF2, and SKI were significantly increased in PBL T-cells isolated from healthy volunteers (Fig. 3a) as well as in cultured human T-cell line Hut78 (Fig. 3b) following incubation with immobilized ICAM-1 over a time period of 24 h. The expression levels of these proteins reached a plateau at 6 h and remained stable from 12 to 24 h (Fig. 3, a and b). Therefore, we used the 6-h time point for further experiments. The induction of SMAD7, SMURF2, and SKI proteins was at levels consistent in relative terms with the results obtained in the Affymetrix array and qRT-PCR analysis (Fig. 2, a–c). The up-regulation of these molecules was independent of indigenous TGF-β, as no significant change in the levels of TGF-β was detected following incubation of T-cells with immobilized ICAM-1 over 6 h (data not shown).

FIGURE 3.

Western blot analysis of LFA-1/ICAM-1-mediated change in the expression levels of SMAD7, SMURF2, and SKI proteins. PBL T-cells purified from healthy volunteers (a) or Hut78 T-cells (b) were incubated on ICAM-1-coated plates for 1, 3, 6, 12, or 24 h and lysed. c, serum-starved PBL T-cells were pretreated with 10 μm AG490, 50 μm STAT3-specific inhibitory peptide (ST3 pep), or 10 μm JNK inhibitor SP600125 (JNK-I) for 1 h and then incubated on ICAM-1-coated plated for additional 6 h. Cell lysates (20 μg each) were Western blotted and probed with anti-SMAD7, anti-SMURF2, or anti-SKI. Blots were reprobed with anti-α-tubulin or anti-β-actin as a loading control. Relative densitometric analysis of the individual protein band is presented. Data are representative of three independent experiments (mean ± S.E.). *, p < 0.05 with respect to corresponding controls.

It has been shown previously that LFA-1 interacts with the transcriptional co-activator Jun-activation domain-binding protein 1 (JAB-1) and activates the transcription factor AP-1 through c-Jun phosphorylation (3, 5, 6), which is mediated by c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) (35, 36). Furthermore, we have demonstrated recently that LFA-1 stimulation in T-cells rapidly activates a transcription factor STAT3 by tyrosine phosphorylation and subsequent nuclear translocation (4). Using the Text Mining Application from SABiosciences and the UCSC Genome Browser, we identified six, three, and two binding sites for STAT3, c-Jun, and AP-1 in the promoter of SMAD7, one binding site each for c-Jun and AP-1 in SMURF2, and one binding site each for STAT3 and c-Jun in SKI, respectively. Therefore, we examined whether LFA-1/ICAM-1-mediated up-regulation of TGF-β signaling proteins was dependent on STAT3 and/or JNK activation. Although pretreatment of T-cells with a JNK-specific inhibitor partly diminished the expression of all the three TGF-β inhibitory proteins, AG490- or STAT3-specific inhibitory peptide inhibited LFA-1/ICAM-1-mediated expression of SMAD7 and SKI but not SMURF2 (Fig. 3c).

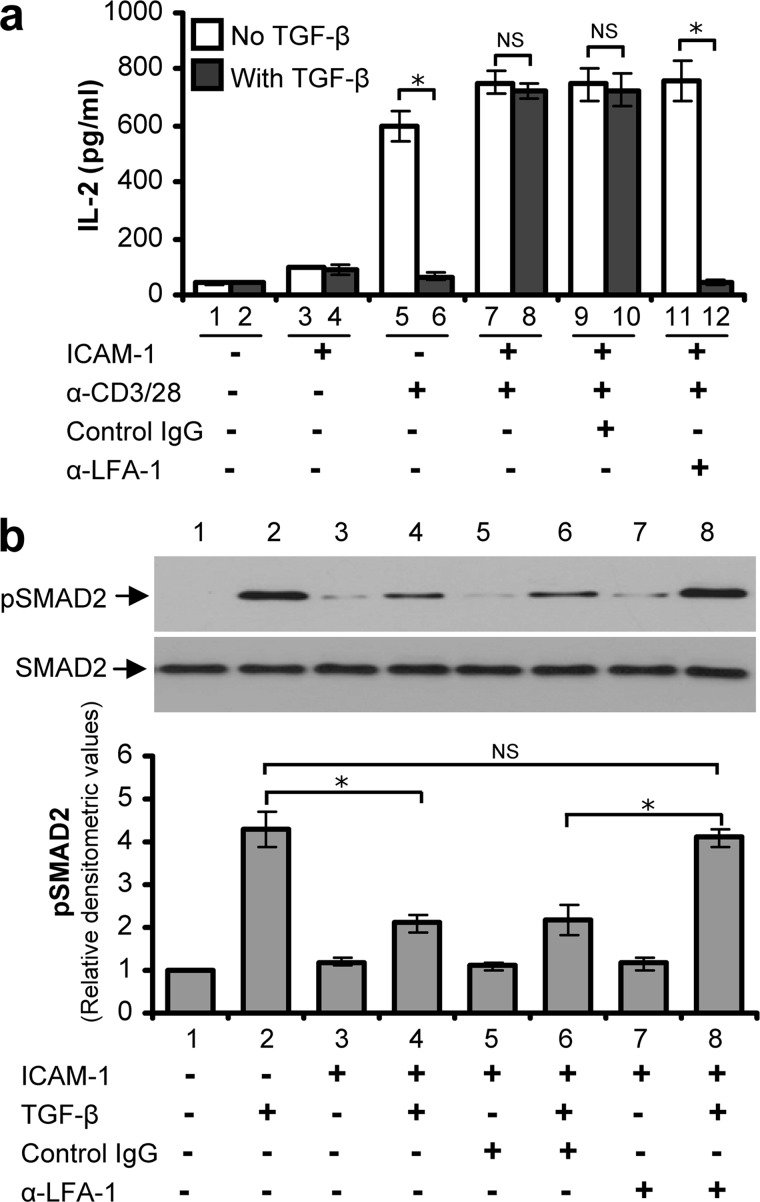

T-cells Become Refractory to TGF-β Signaling Following LFA-1/ICAM-1 Interactions

We next investigated whether LFA-1/ICAM-1-mediated changes in gene expression in T-cells, in particular those molecules that negatively regulate TGF-β signaling, is reflected in terms of TGF-β sensitivity. We first assayed TGF-β sensitivity of T-cells for their ability to produce IL-2. Both PBL and Hut78 T-cells secrete IL-2 following stimulation via CD3/CD28. TGF-β has been shown to suppress IL-2 production of T-cells (15), and as such has been proposed to be a major contributor to T-cell tolerance and immune suppression. We observed that TGF-β significantly reduced anti-CD3/CD28-stimulated IL-2 release in PBL (Fig. 4a, lane 5 versus 6) as well as in Hut78 T-cells (data not shown). However, TGF-β failed to suppress IL-2 secretion in T-cells that have been preincubated with ICAM-1 (Fig. 4a, lane 7 versus 8). Inhibiting LFA-1 signaling in T-cells by using a blocking antibody restored the ability of TGF-β to inhibit IL-2 secretion in the presence of ICAM-1 (Fig. 4a, lane 11 versus 12), which was otherwise impaired (Fig. 4a, lane 7 versus 8 and lane 9 versus 10).

FIGURE 4.

LFA-1/ICAM-1 stimulated T-cells are unresponsive to TGF-β. a, PBL T-cells purified from healthy volunteers were pre-treated with or without control IgG, or LFA-1 blocking antibody (α-LFA-1) for 30 min. These cells were stimulated with or without ICAM-1 for 6 h and then incubated with anti-CD3/CD28 (α-CD3/28) for an additional 24 h in the presence or absence of TGF-β. Conditioned medium was collected, and IL-2 secretion was measured by ELISA. b, PBL T-cells pre-treated with or without control IgG, or LFA-1 blocking antibody (α-LFA-1) were stimulated via LFA-1/ICAM-1 for 6 h or un-stimulated and then treated with or without 5 ng/ml TGF-β before lysis. Cell lysates (20 μg each) were Western blotted and probed with anti-pSMAD2 or anti-SMAD2. Relative densitometric analysis of the individual pSMAD2 protein band is presented. Data are representative of three independent experiments (mean ± S.E.). *, p < 0.05; NS, not significant.

To further validate our findings, we investigated additional functional components regulating TGF-β signaling in T-cells influenced by LFA-1/ICAM-1 interactions. We assayed LFA-1/ICAM-1 stimulated T-cells for TGF-β sensitivity in terms of its ability to induce SMAD2 phosphorylation, a marker of TGF-β receptor activity (12, 30). TGF-β treatment resulted in the increased phosphorylation of SMAD2 in both PBL (Fig. 4b, lane 2 versus 1) and in Hut78 T-cells (data not shown). However, LFA-1/ICAM-1 interactions caused inhibition of TGF-β-induced SMAD2 phosphorylation (Fig. 4b, lane 4 versus 2), indicating that T-cells became refractive to TGF-β signaling. When PBL T-cells were pretreated with LFA-1 blocking antibody, they remained sensitive to TGF-β in terms of SMAD2 phosphorylation even when incubated on immobilized ICAM-1(Fig. 4b, lane 8 versus 6).

LFA-1/ICAM-1-mediated Up-regulation of SMAD7, SMURF2, and SKI Impairs TGF-β Signaling in T-cells

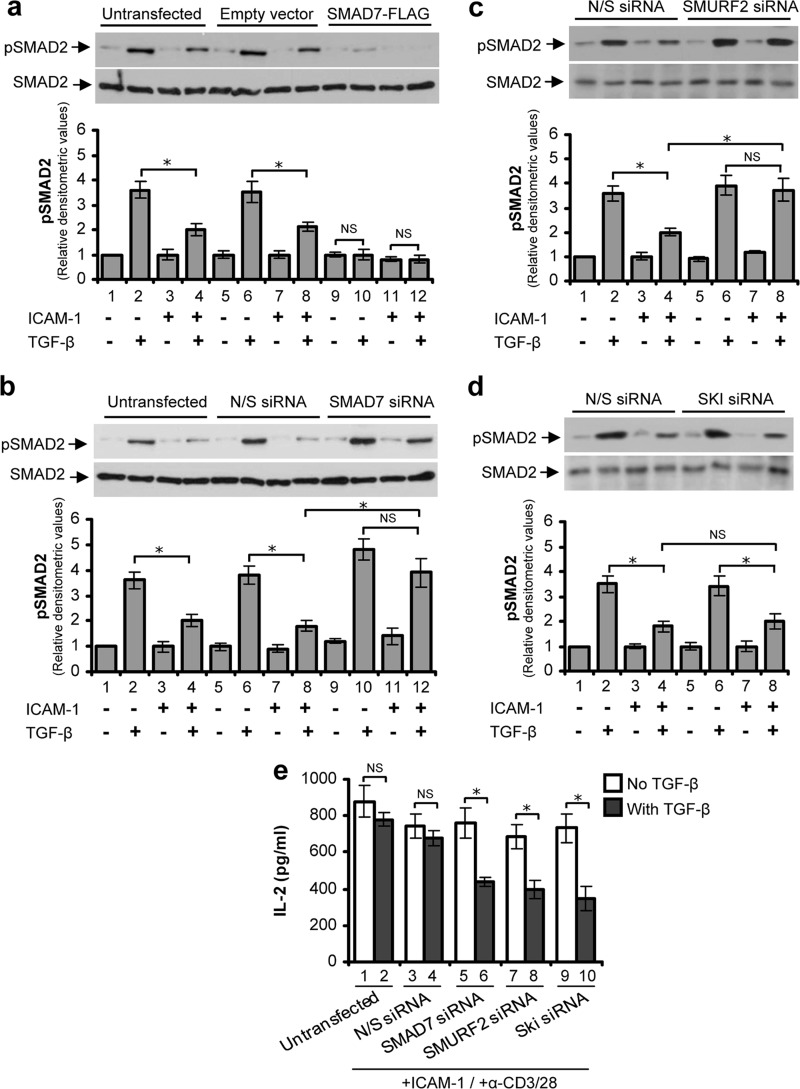

To investigate the specific role of the identified molecules in T-cell TGF-β signaling, we utilized the well characterized Hut78 cell culture model (4, 21, 25–27), which permitted the use of plasmid constructs or siRNA to modulate specific protein expression. Transfecting T-cells with a plasmid vector containing FLAG-SMAD7 gene construct increased (up to 3-fold) the expression of SMAD7 (data not shown). SMAD7-overexpressing T-cells were unresponsive to TGF-β in terms of SMAD2 phosphorylation (Fig. 5a). Conversely, following specific knockdown (>75%) of SMAD7 in T-cells by using an siRNA approach (data not shown), there was a substantial increase in TGF-β-induced SMAD2 phosphorylation (Fig. 5b). Furthermore, SMAD7-depleted T-cells showed TGF-β-induced phosphorylation of SMAD2 even after LFA-1/ICAM-1 stimulation (Fig. 5b). In a similar manner, cells that have been electroporated with SMURF2 siRNA and stimulated through LFA-1/ICAM-1 showed a significant increase in TGF-β-induced SMAD2 phosphorylation (Fig. 5c). However, we could not detect any changes in TGF-β-induced SMAD2 phosphorylation levels in T-cells transfected with SKI siRNA as compared with their respective controls (Fig. 5d). This may be because SKI regulates TGF-β signaling downstream to SMAD2 (14). Depletion of SMAD7, SMURF2, or SKI by siRNA in T-cells resulted in the restoration of their sensitivity to TGF-β (which was impaired by LFA-1/ICAM-1 mediated signaling) in terms of IL-2 secretion (Fig. 5e), indicating that SKI has similar functional effects albeit mediated potentially through a different mechanism.

FIGURE 5.

Specific alteration of SMAD7, SMURF2, or SKI expression modulates T-cell TGF-β responsiveness. Hut78 T-cells were electroporated with plasmid construct containing SMAD7-FLAG or vector alone (a); nonspecific siRNA (N/S) or specific siRNA against SMAD7 (b), SMURF2 (c), or SKI (d). After 48 h, cells were stimulated via LFA-1/ICAM-1 for 6 h or unstimulated and then treated with or without 5 ng/ml TGF-β for 30 min before lysis. Cell lysates (20 μg each) were Western blotted and probed with anti-pSMAD2 or anti-SMAD2. Relative densitometric analysis of the individual pSMAD2 protein band is presented. e, untransfected or siRNA (N/S, SMAD7, SMURF2, or SKI) transfected Hut78 T-cells were stimulated via LFA-1/ICAM-1 for 6 h and then incubated with anti-CD3/CD28 for additional 24 h in the presence or absence of TGF-β. Conditioned medium was collected, and IL-2 secretion was measured by ELISA. Data are representative of three independent experiments performed in triplicate (mean ± S.E.). *, p < 0.05; NS, not significant.

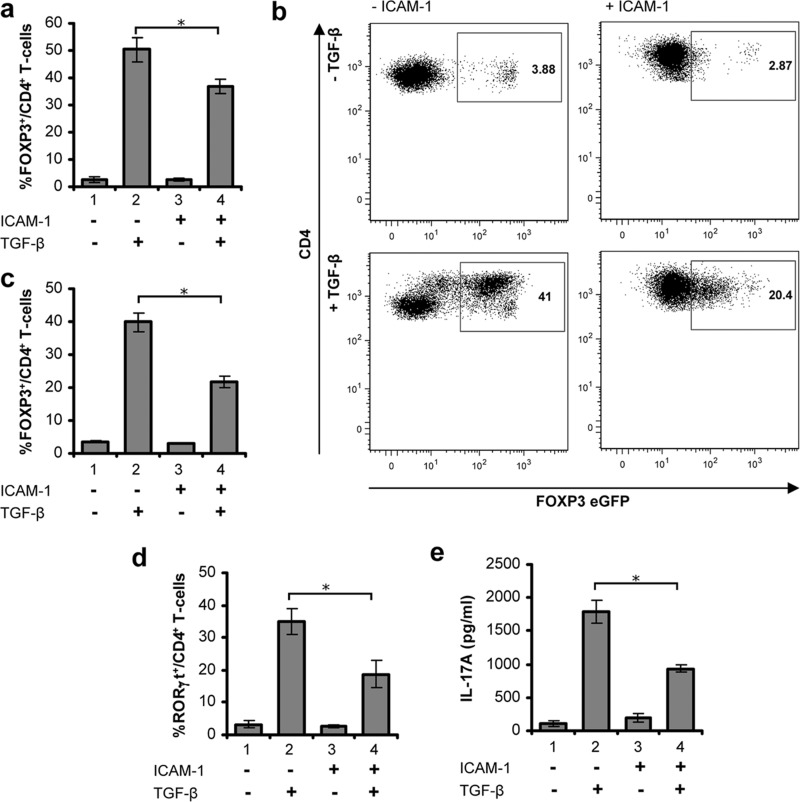

LFA-1/ICAM-1-stimulated T-cells Are Refractory to TGF-β-induced iTreg or Th17 Conversion

Given the crucial role of TGF-β signaling pathway in the T-cell differentiation program (8–11) and the above data indicating that LFA-1/ICAM-1-stimulated T-cells are refractory to TGF-β signaling, we examined the impact of ICAM-1/LFA-1 interactions in the development of RORγt+ Th17 or FOXP3+ regulatory T-cells. Previous studies have demonstrated that TGF-β in the presence of IL-2 can induce FOXP3 expression in human T-cell receptor activated CD4+ T-cells in vitro (9, 28), a process associated with the development of a phenotype that resembles iTreg. We compared TGF-β induced FOXP3 expression between unstimulated human T-cells and cells prestimulated through LFA-1/ICAM-1 by immunostaining and high content analysis. Induction of FOXP3 expression was observed in a substantial percentage (∼50%) of anti-CD3/CD28-primed CD4+ T-cells in the presence of TGF-β (Fig. 6a, lane 2). However, FOXP3+ cell numbers in the T-cells stimulated through LFA-1/ICAM-1 were significantly lower (∼20%) than those present in unstimulated T-cells (Fig. 6a, lane 2 versus 4). To further confirm these findings, CD4+ T-cells isolated from Foxp3-eGFP reporter mice were incubated under conditions for FOXP3+ cell development in the presence or absence of ICAM-1. Flow cytometry analysis demonstrated that the frequency of FOXP3+ CD4+ T-cells was significantly (p < 0.05) impaired in the presence of ICAM-1 (Fig. 6b). TGF-β was able to induce expression of FOXP3 in >40% of CD4+ T-cells. However, in the presence of ICAM-1, a significantly smaller number (∼20%) of CD4+ T-cells could be induced to express FOXP3 (Fig. 6c, lane 2 versus 4).

FIGURE 6.

LFA-1/ICAM-1-mediated signaling in T-cells suppresses TGF-β-induced FOXP3+ iTreg or RORγt+ Th17 differentiation. a, unstimulated or LFA-1/ICAM-1 stimulated human PBL T-cells were cultured with or without 5 ng/ml TGF-β under iTreg differentiation conditions for 5 days. Cells were stained for CD4 and FOXP3 followed by high content imaging and analysis. Percentage of FOXP3+ cells among CD4+ T-cells are presented. b, representative flow cytometry plots of Foxp3-eGFP expressing CD4+ T-cells from FOXP3-eGFP reporter mice. CD4+ cells were isolated and incubated with or without ICAM-1 under iTreg conditions for 72 h in the presence or absence of 5 ng/ml TGF-β. c, mean percentage of FOXP3-eGFP+ mouse CD4+ cells treated as indicated (data are mean ± S.E. from four to six individual mice). d, unstimulated or LFA-1/ICAM-1-stimulated human PBL T-cells were cultured with or without 5 ng/ml TGF-β under Th17 conditions for 4 days. Cells were stained for CD4 and RORγt, followed by high content imaging and analysis. Percentage of RORγt+ cells among CD4+ T-cells is presented. e, expression of IL-17, detected by ELISA, in supernatants from cells cultured as described in d. Data are representative of at least three independent experiments (mean ± S.E.). *, p < 0.05.

Recent studies have demonstrated that TGF-β in conjugation with the proinflammatory cytokine IL-6 initiates IL-17 producing RORγt+ Th17 cell development (10). When stimulated via CD3/CD28 in the presence of IL-6, anti-IFN-γ, and anti-IL-4 for 4 days, TGF-β induced differentiation of ∼40% CD4+ T-cells into RORγt+ cells as quantified by high content analysis (Fig. 6d, lane 2). However, pre-exposure to the LFA-1/ICAM-1 signal in T-cells substantially inhibited the induction of RORγt+ cells (Fig. 6d, lane 2 versus 4). LFA-1/ICAM-1 prestimulated T-cells that have been treated with TGF-β and IL-6 simultaneously in vitro secreted significantly less (∼50%) IL-17 as compared with unstimulated cells (Fig. 6e, lane 2 versus 4). These data suggest that T-cells stimulated through LFA-1/ICAM-1 are partially but significantly refractory to TGF-β-induced differentiation to RORγt+ Th-17 or FOXP3+ iTreg cells.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we addressed the role of LFA-1 signaling in the downstream regulation of gene expression in T-cells rendering them refractory to TGF-β function. We employed several strategies to investigate the functional impact of changes in gene expression induced by T-cell LFA-1/ICAM-1 interactions. Our data clearly demonstrate that LFA-1/ICAM-1 cross-linking in T-cells up-regulates a set of TGF-β inhibitory genes and proteins via activation of STAT3 and/or JNK, which results in refractoriness of T-cells to TGF-β signaling in terms of effector functions. The finding that the LFA-1/ICAM-1-mediated signaling had transcriptome level impact on the genes involved in T-cell immunoreactivity deserves special attention, in particular with regard to those genes participating in the regulation of TGF-β-mediated functions. We observed that the LFA-1/ICAM-1 interaction could trigger up-regulation of expression of SMAD7 and SMURF2 in addition to two other molecules, SKI and SKIL, all known regulators of TGF-β signaling.

TGF-β is capable of inhibiting proinflammatory cytokines, including IL-2, in activated T-lymphocytes and plays a critical role in the local control of inflammation (15), at least in part through the modulation and control of regulatory T-cell responses. In this study, we have demonstrated that LFA-1/ICAM-1-stimulated T-cells exhibit defective TGF-β signaling, as measured by phospho-SMAD2 immunoreactivity and are resistant to TGF-β-mediated suppression of IL-2 secretion. Specific modulation of SMAD7 expression in T-cells by overexpression or siRNA-mediated knockdown enabled them to resist or respond to TGF-β. In previous studies, the physiological consequences of defective TGF-β signaling due to SMAD7 deregulation has been seen in a number of pathological conditions, including chronic inflammatory diseases (11, 30, 37–43). For example, in vivo administration of Smad7 antisense oligonucleotides to colitic mice restored TGF-β signaling, ameliorated inflammation, and decreased the synthesis of inflammatory molecules and the extent of gut damage (38, 43). Thus, blocking SMAD7 could be a promising way to dampen chronic inflammation, particularly during active phases when expression levels of SMAD7 are high.

We also identified ubiquitination regulatory factors SMURF1 and SMURF2 to be up-regulated by LFA-1/ICAM-1 interaction in T-cells. SMURF1 and SMURF2 are members of the Hect family of E3 ubiquitin ligases that participate in the degradation of TGF-β receptors and other targets (31) and are involved in down-regulation of the TGF-β signaling pathway (32). SMURF2, synergistically with SMAD7 through direct interaction, interferes with the activation of receptor associated SMAD2 and SMAD3 and plays a role in their targeted degradation by ubiquitination (31, 32). A more recent study established a crucial role of ubiquitination process involving an E2 ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme Ubc13 in maintaining the in vivo immunosuppressive function of Treg cells and in preventing the conversion of Treg into Th1- or Th17-like effector T-cells (44). The SKI family of nuclear oncoproteins bind directly to the SMAD3/4 complex in the nucleus and negatively regulate TGF-β signaling (33, 34). Although the exact role of these molecules in LFA-1/ICAM-1-stimulated T-cells under in vivo conditions remain unclear, we believe that up-regulation of potent TGF-β signaling inhibitors in T-lymphocytes would generate TGF-β unresponsiveness.

TGF-β is a critical differentiation factor for the generation of both Th17 as well as iTreg cell subsets (9–11). Although implicated in antagonistic functions, both iTregs and Th17 effector cells play crucial roles in immunoregulation, host defense, and autoimmune pathogenesis. Although Tregs play a fundamental role in protection from autoimmunity, their differentiation is tightly linked to the development of Th17 cells, a highly pathogenic effector T-cell subset involved in inducing inflammation and autoimmune tissue injury (9, 10, 16). Recently, a subset of FOXP3+ peripheral Tregs that exhibit dual Treg and Th17 function depending on environmental factors under inflammatory conditions has also been identified (45). Utilizing multiple approaches, we showed that human PBL T-cells as well as CD4+ T-cells isolated from transgenic reporter mice stimulated through LFA-1/ICAM-1 were resistant to TGF-β-mediated FOXP3+ iTreg induction. In a similar manner, LFA-1/ICAM-1-stimulated T-cells were refractory to TGF-β-dependent development of RORγt+ IL-17 producing Th17 cells. Previous in vivo studies have shown that mice defective in TGF-β signaling lack Th17 cells and do not develop experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (46). The observed suppressive role of LFA-1/ICAM-1-mediated signaling on TGF-β-induced iTreg as well as Th17 cell differentiation leaves open the possibility that LFA-1/ICAM-1 interaction selectively triggers gene expression, which controls the development of both lineages and thereby modulates the associated downstream functions of T-cells.

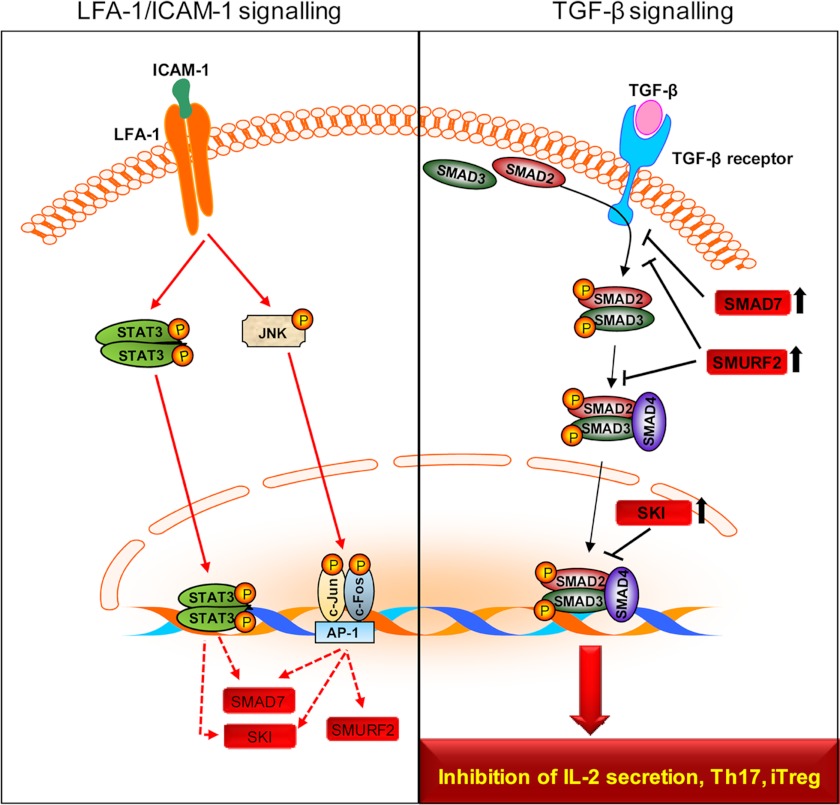

The present study thus elucidates key biochemical and molecular mechanisms by which LFA-1/ICAM-1 interactions render T-cells refractory to TGF-β signaling. Based on these data, we now propose a model for the molecular crosstalk between LFA-1 and TGF-β signaling pathways (Fig. 7). LFA-1/ICAM-1 interactions play a key role(s) in up-regulating several molecules, including SMAD7, SMURF2, and SKI protein expression via activation of transcriptional regulators such as STAT3 and/or JNK. These molecules, in turn, render T-cells refractory to TGF-β. LFA-1/ICAM-1-mediated signaling has a profound regulatory impact on the TGF-β responsiveness of T-cells with regard to IL-2 secretion and influences the relative development of both RORγt+ Th17 and FOXP3+ iTreg lineages, possibly depending on the co-stimulated cytokine milieu in distinct tissue. Our study also suggest that the behavior of iTreg cells may be influenced in an inflamed environment characterized by T-cell migration, which may be an important consideration as Treg-based immunotherapy is making its way from bench to bedside.

FIGURE 7.

A model for LFA-1/ICAM-1-mediated signal resulting in T-cells refractory to TGF-β signaling. The figure illustrates that LFA-1/ICAM-1 interaction induces up-regulation of SMAD7, SMURF2, and SKI protein expression in T-cells via STAT3 and/or JNK (left panel). The increased expression of SMAD7, SMURF2, and SKI proteins results in T-cells refractive to TGF-β signaling and interferes with TGF-β-mediated inhibition of IL-2 secretion and T-cell differentiation processes (right panel).

Recent in vitro, in vivo and preclinical studies in patients with stable psoriasis clearly indicate LFA-1 involvement in modulating T-cell functions, including activation and proliferation (18, 19). For example, in a murine transplant model, an increased frequency of FOXP3+ Tregs was observed in the peripheral lymph nodes following LFA-1 blockade by anti-LFA-1 (17). A humanized anti-LFA-1 antibody efalizumab (Raptiva®), developed for the treatment of psoriasis, was found to induce a unique state of T-cell hyporesponsiveness in terms of activation and proliferation (18, 47). LFA-1 deficiency was also suggested to dampen encephalomyelitis upon active induction of an autoimmune response (48). Unfortunately, despite encouraging results using LFA-1 blockade, further clinical trials have been hampered by several cases of the development of progressive multi-focal leukoencephalopathy in patients receiving long term courses of efalizumab (49). In the current study, interruption of LFA-1/ICAM-1 interaction by antibody blockade of LFA-1 prevented the development of TGF-β unresponsive phenotypes in T-cells. We therefore propose that signals emanating from LFA-1/ICAM-1 interaction fine-tune classical immune suppression by TGF-β, possibly facilitating the delivery of effector lymphocytes primed to respond at the site of inflammation. It can be speculated that drugs that target LFA-1 (such as efalizumab) could also generate some of their functional effects through increasing T-cell responsiveness to TGF-β and thus modulate the Treg phenotype in addition to effects on the immune synapse and on lymphocyte migration. Dissection of differential signaling for migration and for generation of TGF-β hyporesponsiveness might permit the development of more selective inhibitors of LFA-1 with less pronounced effects on immune responsiveness to viruses such as the JC-1 virus implicated in progressive multi-focal leukoencephalopathy. These findings indicate the need for judicious application of LFA-1 targeting and may have implications for designing of immunotherapies in the clinical settings.

Acknowledgments

We thank Prof. Carl-Henrik Heldinm (Ludwig Institute for Cancer Research Ltd., Uppsala University, Uppsala, Sweden) for providing the SMAD7 plasmid construct as a gift. We thank Dara Dunican and Michael Freeley for sharing experiences in experimentation and Anne Murphy for technical assistance.

This work was supported by grants from the Enterprise Ireland, Higher Education Authority of Ireland under the Program for Research in Third Level Institutions (PRTLI) Cycle 3, Science Foundation Ireland (SFI), and the Health Research Board (HRB) of Ireland.

This article contains supplemental Table 1.

- LFA-1

- leukocyte function-associated antigen-1

- ICAM-1

- intercellular adhesion molecule-1

- AP-1

- activator protein-1

- iTreg

- induced regulatory T-cell

- PBL

- peripheral blood lymphocyte

- qRT-PCR

- quantitative RT-PCR

- eGFP

- enhanced GFP.

REFERENCES

- 1. Ley K., Laudanna C., Cybulsky M. I., Nourshargh S. (2007) Getting to the site of inflammation: The leukocyte adhesion cascade updated. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 7, 678–689 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Hogg N., Laschinger M., Giles K., McDowall A. (2003) T-cell integrins: More than just sticking points. J. Cell Sci. 116, 4695–4705 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Shimizu Y. (2003) LFA-1: More than just T cell velcro. Nat. Immunol. 4, 1052–1054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Verma N. K., Dourlat J., Davies A. M., Long A., Liu W. Q., Garbay C., Kelleher D., Volkov Y. (2009) STAT3-stathmin interactions control microtubule dynamics in migrating T-cells. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 12349–12362 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Perez O. D., Mitchell D., Jager G. C., South S., Murriel C., McBride J., Herzenberg L. A., Kinoshita S., Nolan G. P. (2003) Leukocyte functional antigen 1 lowers T cell activation thresholds and signaling through cytohesin-1 and Jun-activating binding protein 1. Nat. Immunol. 4, 1083–1092 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bianchi E., Denti S., Granata A., Bossi G., Geginat J., Villa A., Rogge L., Pardi R. (2000) Integrin LFA-1 interacts with the transcriptional co-activator JAB1 to modulate AP-1 activity. Nature 404, 617–621 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Zhang X., Wrzeszczynska M. H., Horvath C. M., Darnell J. E., Jr. (1999) Interacting regions in Stat3 and c-Jun that participate in cooperative transcriptional activation. Mol. Cell Biol. 19, 7138–7146 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Rubtsov Y. P., Rudensky A. Y. (2007) TGFβ signaling in control of T-cell-mediated self-reactivity. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 7, 443–453 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Yamagiwa S., Gray J. D., Hashimoto S., Horwitz D. A. (2001) A role for TGF-β in the generation and expansion of CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells from human peripheral blood. J. Immunol. 166, 7282–7289 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Mangan P. R., Harrington L. E., O'Quinn D. B., Helms W. S., Bullard D. C., Elson C. O., Hatton R. D., Wahl S. M., Schoeb T. R., Weaver C. T. (2006) Transforming growth factor-β induces development of the TH17 lineage. Nature 441, 231–234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Li M. O., Sanjabi S., Flavell R. A. (2006) Transforming growth factor-β controls development, homeostasis, and tolerance of T cells by regulatory T cell-dependent and -independent mechanisms. Immunity 25, 455–471 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Moustakas A., Souchelnytskyi S., Heldin C. H. (2001) Smad regulation in TGF-β signal transduction. J. Cell Sci. 114, 4359–4369 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Nakao A., Afrakhte M., Morén A., Nakayama T., Christian J. L., Heuchel R., Itoh S., Kawabata M., Heldin N. E., Heldin C. H., ten Dijke P. (1997) Identification of Smad7, a TGFβ-inducible antagonist of TGF- β signaling. Nature 389, 631–635 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Deheuninck J., Luo K. (2009) Ski and SnoN, potent negative regulators of TGF-β signaling. Cell Res. 19, 47–57 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Das L., Levine A. D. (2008) TGF-β inhibits IL-2 production and promotes cell cycle arrest in TCR-activated effector/memory T cells in the presence of sustained TCR signal transduction. J. Immunol. 180, 1490–1498 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Weaver C. T., Hatton R. D. (2009) Interplay between the TH17 and TReg cell lineages: A (co-)evolutionary perspective. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 9, 883–889 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Josefowicz S. Z., Niec R. E., Kim H. Y., Treuting P., Chinen T., Zheng Y., Umetsu D. T., Rudensky A. Y. (2012) Extrathymically generated regulatory T cells control mucosal TH2 inflammation. Nature 482, 395–399 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Koszik F., Stary G., Selenko-Gebauer N., Stingl G. (2010) Efalizumab modulates T cell function both in vivo and in vitro. J. Dermatol. Sci. 60, 159–166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Reisman N. M., Floyd T. L., Wagener M. E., Kirk A. D., Larsen C. P., Ford M. L. (2011) LFA-1 blockade induces effector and regulatory T-cell enrichment in lymph nodes and synergizes with CTLA-4Ig to inhibit effector function. Blood 118, 5851–5861 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Volkov Y., Long A., McGrath S., Ni Eidhin D., Kelleher D. (2001) Crucial importance of PKC-β(I) in LFA-1-mediated locomotion of activated T cells. Nat. Immunol. 2, 508–514 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Volkov Y., Long A., Kelleher D. (1998) Inside the crawling T cell: Leukocyte function-asociated antigen-1 cross-linking is associated with microtubule-directed translocation of protein kinase C isozymes β(I) and δ. J. Immunol. 161, 6487–6495 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kent W. J., Sugnet C. W., Furey T. S., Roskin K. M., Pringle T. H., Zahler A. M., Haussler D. (2002) The human genome browser at UCSC. Genome Res. 12, 996–1006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Gotea V., Ovcharenko I. (2008) DiRE: Identifying distant regulatory elements of co-expressed genes. Nucleic Acids Res. 36, W133-W139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Heid C. A., Stevens J., Livak K. J., Williams P. M. (1996) Real time quantitative PCR. Genome. Res. 6, 986–994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Verma N. K., Dempsey E., Conroy J., Olwell P., Mcelligott A. M., Davies A. M., Kelleher D., Butini S., Campiani G., Williams D. C., Zisterer D. M., Lawler M., Volkov Y. (2008) A new microtubule-targeting compound PBOX-15 inhibits T-cell migration via post-translational modifications of tubulin. J. Mol. Med. 86, 457–469 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Verma N. K., Dempsey E., Freeley M., Botting C. H., Long A., Kelleher D., Volkov Y. (2011) Analysis of dynamic tyrosine phosphoproteome in LFA-1 triggered migrating T-cells. J. Cell Physiol. 226, 1489–1498 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Verma N. K., Davies A. M., Long A., Kelleher D., Volkov Y. (2010) STAT3 knockdown by siRNA induces apoptosis in human cutaneous T-cell lymphoma line Hut78 via down-regulation of Bcl-xl. Cell Mol. Biol. Lett. 15, 342–355 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Tran D. Q., Ramsey H., Shevach E. M. (2007) Induction of FOXP3 expression in naive human CD4+FOXP3− T cells by T-cell receptor stimulation is transforming growth factor-β-dependent but does not confer a regulatory phenotype. Blood 110, 2983–2990 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Amu S., Saunders S. P., Kronenberg M., Mangan N. E., Atzberger A., Fallon P. G. (2010) Regulatory B cells prevent and reverse allergic airway inflammation via FoxP3-positive T regulatory cells in a murine model. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 125, 1114–1124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Schmierer B., Hill C. S. (2007) TGFβ-SMAD signal transduction: Molecular specificity and functional flexibility. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 8, 970–982 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Lin X., Liang M., Feng X. H. (2000) Smurf2 is a ubiquitin E3 ligase mediating proteasome-dependent degradation of Smad2 in transforming growth factor-β signaling. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 36818–36822 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Kavsak P., Rasmussen R. K., Causing C. G., Bonni S., Zhu H., Thomsen G. H., Wrana J. L. (2000) Smad7 binds to Smurf2 to form an E3 ubiquitin ligase that targets the TGFβ receptor for degradation. Mol. Cell 6, 1365–1375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Sun Y., Liu X., Eaton E. N., Lane W. S., Lodish H. F., Weinberg R. A. (1999) Interaction of the Ski oncoprotein with Smad3 regulates TGF-β signaling. Mol. Cell 4, 499–509 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Wu J. W., Krawitz A. R., Chai J., Li W., Zhang F., Luo K., Shi Y. (2002) Structural mechanism of Smad4 recognition by the nuclear oncoprotein Ski: Insights on Ski-mediated repression of TGF-β signaling. Cell 111, 357–367 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Karin M. (1995) The regulation of AP-1 activity by mitogen-activated protein kinases. J. Biol. Chem. 270, 16483–16486 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Whitmarsh A. J., Davis R. J. (1996) Transcription factor AP-1 regulation by mitogen-activated protein kinase signal transduction pathways. J. Mol. Med. 74, 589–607 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Monteleone G., Kumberova A., Croft N. M., McKenzie C., Steer H. W., MacDonald T. T. (2001) Blocking Smad7 restores TGF-β1 signaling in chronic inflammatory bowel disease. J. Clin. Invest. 108, 601–609 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Monteleone G., Boirivant M., Pallone F., MacDonald T. T. (2008) TGF-β1 and Smad7 in the regulation of IBD. Mucosal Immunol. 1, S50–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Monteleone G., Pallone F., MacDonald T. T. (2004) Smad7 in TGF-β-mediated negative regulation of gut inflammation. Trends Immunol. 25, 513–517 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Nakao A., Okumura K., Ogawa H. (2002) Smad7: A new key player in TGF-β-associated disease. Trends Mol. Med. 8, 361–363 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Monteleone G., Del Vecchio Blanco G., Monteleone I., Fina D., Caruso R., Gioia V., Ballerini S., Federici G., Bernardini S., Pallone S., MacDonald T. T. (2005) Post-transcriptional regulation of Smad7 in the gut of patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterol. 129, 1420–1429 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Smart N. G., Apelqvist A. A., Gu X., Harmon E. B., Topper J. N., MacDonald R. J., Kim S. K. (2006) Conditional expression of Smad7 in pancreatic β cells disrupts TGF-β signaling and induces reversible diabetes mellitus. PLoS Biol. 4, e39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Boirivant M., Pallone F., Di Giacinto C., Fina D., Monteleone I., Marinaro M., Caruso R., Colantoni A., Palmieri G., Sanchez M., Strober W., MacDonald T. T., Monteleone G. (2006) Inhibition of Smad7 with a specific antisense oligonucleotide facilitates TGF-β1-mediated suppression of colitis. Gastroenterology 131, 1786–1798 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Chang J. H., Xiao Y., Hu H., Jin J., Yu J., Zhou X., Wu X., Johnson H. M., Akira S., Pasparakis M., Cheng X., Sun S. C. (2012) Ubc13 maintains the suppressive function of regulatory T cells and prevents their conversion into effector-like T cells. Nat. Immunol. 13, 481–490 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Voo K. S., Wang Y. H., Santori F. R., Boggiano C., Wang Y. H., Arima K., Bover L., Hanabuchi S., Khalili J., Marinova E., Zheng B., Littman D. R., Liu Y. J. (2009) Identification of IL-17-producing FOXP3+ regulatory T cells in humans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 4793–4798 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Veldhoen M., Hocking R. J., Flavell R. A., Stockinger B. (2006) Signals mediated by transforming growth factor-β initiate autoimmune encephalomyelitis, but chronic inflammation is needed to sustain disease. Nat. Immunol. 7, 1151–1156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Guttman-Yassky E., Vugmeyster Y., Lowes M. A., Chamian F., Kikuchi T., Kagen M., Gilleaudeau P., Lee E., Hunte B., Howell K., Dummer W., Bodary S. C., Krueger J. G. (2008) Blockade of CD11a by efalizumab in psoriasis patients induces a unique state of T-cell hyporesponsiveness. J. Invest. Dermatol. 128, 1182–1191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Wang Y., Kai H., Chang F., Shibata K., Tahara-Hanaoka S., Honda S., Shibuya A., Shibuya K. (2007) A critical role of LFA-1 in the development of Th17 cells and induction of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 353, 857–862 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Carson K. R., Focosi D., Major E. O., Petrini M., Richey E. A., West D. P., Bennett C. L. (2009) Monoclonal antibody-associated progressive multifocal leucoencephalopathy in patients treated with rituximab, natalizumab, and efalizumab: A review from the Research on Adverse Drug Events and Reports (RADAR) Project. Lancet Oncol. 10, 816–824 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]