Trash-lined sidewalks in the Jamaica Plain neighborhood: Boston, MA, 2011.

Gutters in the Jamaica Plain neighborhood: Boston, MA, 2011.

A GROUP OF 60 PREDOMINANTLY Black and Latino students in Boston, Massachusetts, between the ages of 11 and 15 years, recognized trash and neighborhood squalor as a threat to their well-being and health. These youths were participants in Nuestro Futuro Saludable (NFS), an afterschool intervention designed to engage urban minority middle-school students in an exploration of the relationship between their living environments, health behaviors, and stress.1 A central component of the intervention required students to record visual impressions of their community, particularly elements of the neighborhood they believed contributed to or detracted from their health and well-being.

Students pointedly described the frequent piles of dog refuse on sidewalks as “nasty” and viewed them as a health hazard. One student reported,

I see a lot of garbage and dirt and other unhealthy stuff on the ground… . This makes people abandon this city ’cause of its filthiness.

Another student described trash as a community problem because,

most people can’t walk through the sidewalk because there’s trash in the way.

Students reported that

no one wants to be in a dirty environment and the neighborhood has trash all over the place, and it is unpleasant to live in.

The quantity of the student photographs focused on trash caught the adult members of the project team off guard. It was expected that youths would portray scenes of tobacco advertising, liquor stores, gang activity, and loitering, topics well documented in the literature.2,3 It was also suspected, incorrectly, that broken sidewalks and a lack of streetlights might emerge as concerns and be worthy of a photo.

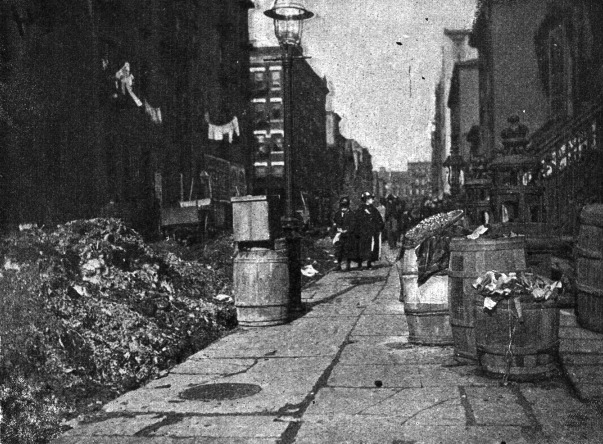

Trash-lined streets in New York City, 1895.

Source. Harper’s Weekly. June 22, 1895 (p586).

These expectations represent a disconnect between the adult researchers, facilitators, and program planners and the youths. This disconnect underscores the importance of engaging community residents, particularly youths, in the initial stages of developing research protocols and interventions. Local residents possess a unique understanding of community health priorities and contextual factors that may influence the crafting of research priorities as well as intervention uptake. Furthermore, youths may experience and interact with the community in a way that is different from that of adults and give voice to different views on priorities.

Sanitation-related concerns are nothing new for public health practitioners; well before John Snow’s iconic removal of the Broad Street Pump, the role of the built environment was recognized as an important factor in protecting community health.4,5 Early public health leaders emphasized the significance of sanitary urban environments even as newly arrived Americans poured into the teeming cities of the 19th century. More than a century and a half before NFS, the words of Lemuel Shattuck in his plan advocating for public health priorities in Massachusetts cut through the years:

Public health requires such laws and regulations, as will secure to man associated in society, the same sanitary enjoyments that he would have as an isolated individual.5(p9)

Trash filled gutters in Pittsburgh, PA, 1926.

Source. Oliver M. Kaufmann Photograph Collection of the Irene Kaufmann Settlement, 1912-1969; AIS.1978.12; Archives Service Center; University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA.

The findings among NFS youths today reinforce that Shattuck’s vision remains a daunting challenge. However, in developed countries recent dialog surrounding public health and sanitation has shifted to complex systems such as food safety and

“Youths may experience and interact with a community in a way that is different from that of adults and give voice to different views on priorities.” macroenvironmental exposures such as water quality. Trash and public health are no longer frequently discussed.

Nonetheless, as demonstrated by the students who participated in NFS, trash remains a concern for urban minority youths. The photographs (see images on previous page), which were taken by NFS students, parallel those taken long ago (see images on this page). The 1893 picture of New York City’s Varick Street that depicts a street lined with rubbish parallels the modern picture of a sidewalk in a Boston neighborhood overtaken by piles of trash. Similarly, the garbage-filled gutter of 1926 Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, is only slightly more filled with debris than the contemporary Boston gutter.

In the United States, racial and ethnic minorities along with new immigrants are more likely to live in impoverished neighborhoods with a fractured infrastructure and thus are more vulnerable to environmental insults that cumulatively may contribute to poor health outcomes.6,7 Although conditions have improved over the last century in urban areas such as Boston, these improvements are not the same for everyone. Local sanitation and hygiene in urban neighborhoods is a problem that may deserve more attention, especially if health disparities are to be effectively addressed.

Acknowledgments

This project is funded by the National Institute for Minority Health and Health Disparities (NIMHD; grant 1R24MD005095).

We are grateful for the guidance provided by the Nuestro Futuro Saludable (NFS) community advisory board and steering committee members. In addition, we would like to give special thanks to the NFS facilitators and the Mary Curley Middle School staff, families, and students. We would also like to thank Sophie Dover who assisted with the initial review of youth photographs.

Note. The contents of this article are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NIMHD.

Human Participant Protection

This Study was approved by the Tufts University Social, Behavioral, and Education Research institutional review board.

References

- 1.Sprague Martinez LS, Ndulue U, Peréa FC. Nuestro Furturo Saludable: A Partnership Approach for Connecting Public Health and Community Development to Build a Healthy Environment. J Commun Dev Soc. 2011;42(2):235–247 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Laws MB, Whitman J, Bowser DM, Krech L. Tobacco availability and point of sale marketing in demographically contrasting districts of Massachusetts. Tob Control. 2002;11(suppl 2):ii71–ii73 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jaycox LH, Stein BD, Kataoka SHet al. Violence exposure, posttraumatic stress disorder, and depressive symptoms among recent immigrant schoolchildren. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2002;41(9):1104–1110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Paneth N. Assessing the contributions of John Snow to epidemiology: 150 years after removal of the Broad Street pump handle. Epidemiology. 2004;15(5):514–516 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shattuck L. Report of the Sanitary Commission of Massachusetts, 1850. Cambridge: Harvard University Press; 1948 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Northridge ME, Stover GN, Rosenthal JE, Sherard D. Environmental equity and health: understanding complexity and moving forward. Am J Public Health. 2003;93(2):209–214 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schulz A, Northridge ME. Social determinants of health: implications for environmental health promotion. Health Educ Behav. 2004;31(4):455–471 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]