Abstract

Low health-related quality of life among morbidly obese subjects is well-known. However, the relationship may not be simple. We aim to examine the association between pre-operative expectations and health-related quality of life and long-term changes in health-related quality of life after gastric banding. The questionnaires were answered twice: before and five years after gastric banding. Short Form-36 assessed health-related quality of life. Obesity specific questions were used to assess the subjects' attribution of impairment to morbid obesity and their expectations to changes as a result of weight loss. The subjects attribute morbid obesity as a major reason for their impairments in state of health, physical activity, pain and work capacity. As a result of weight loss, the subjects expect improvements even within fields which they did not consider to be impaired due to morbid obesity. We found an inverse association between high expectations and mental component summary score at baseline. At follow-up having expectations fully fulfilled was associated with a higher mental component summary score than having expectations fulfilled only to a fair extension and not having expectations fulfilled. Physical component summary was statistically significant improved at follow-up Morbidly obese subjects' attributions of low general well-being combined with their expectations may be a central part of understanding the mechanisms involved in the association between morbid obesity and low health-related quality of life. Furthermore the impact of morbid obesity on health-related quality of life may be reduced if healthprofessionals bridge the gap between morbidly obese subjects' expectations and their experience.

Keywords: Causal attributions, Expectations, Health-related quality of life, Morbid obesity, Gastric banding

Introduction

Morbid obesity is associated with morbidities and premature mortality (Brown et al. 2009; Lavie et al. 2009) at considerable cost to both patients and society (Brown et al. 2009; Muller-Riemenschneider et al. 2008). At present, the only method that ensures permanent weight loss is bariatric surgery (Padwal et al. 2011; Sjostrom et al. 2007); a modality that continues to grow world wide (Buchwald and Oien 2009). Besides the medical consequences they suffer from social stigmatisation and low health-related quality of life (Choban et al. 1999; Dixon et al. 2001; Larsson et al. 2002). Morbidly obese subjects seek bariatric surgery to improve their health-related quality of life and to control their current medical problems (Kaly et al. 2008; Munoz et al. 2007). Long-term follow-up studies show statistically significant improvements in health-related quality of life after weight loss (Helmio et al. 2011; Karlsson et al. 2007).

There is an ongoing discussion about the meaning of quality of life and what issues are of fundamental importance to patients’ well-being. The quality of life concept is multifaceted and can be approached from diverse perspectives (Sirgy 2001). The proposed theoretical models for quality of life include among others the needs model and the expectations model. The needs model involves a dimension of hierarchical goals and define quality of life in terms of the ability and capacity of patients to satisfy needs; this implies that lower-order biological and safety-related goals are more predominant than higher-order psychological goals. The greater the need satisfaction the greater the quality of life (Sirgy 1986). The expectations model propose quality of life to measure “the difference, or the gap, at a particular period of time between the hopes and expectations of the individual and that individual’s present experiences “(Calman 1984); this suggests that a narrowing of the gap between subjects’ hopes and expectations and what is obtainable is a key aim of medical care.

Overall the term health-related quality of life indicates that the focus is on aspects of quality of life which are related to health, disease or treatment. However the relationship between medical conditions and health-related quality of life is neither simple nor direct. In other words different people may have different expectations and furthermore different people may be at different points on their illness trajectory at the time when their health-related quality of life is measured. Finally the reference value of expectations may change over time (Carr et al. 2001). Concerning the relationship between morbid obesity and low health-related quality of life, an inverse causal relationship may be present, which is in contrast to several medical conditions. For instance low health-related quality of life may give cause for morbid obesity in some subjects whilst low health-related quality of life may be conditional on morbid obesity in other subjects. In other words low physical, mental or social function may result in weight gain, and conversely weight gain may lead to low physical, mental or social function. Thus, morbidly obese subjects’ perceptions of causal attributions for impairments in general well-being may lie at the heart of our understanding of the complexity of the mechanisms involved in the association between morbid obesity and low health-related quality of life. In addition the multi-factorial nature of health-related quality of life implies that several factors may potentially influence the outcome of interest whereby the patient’s expectations may disclose relevant details. Understanding the determinants of health-related quality of life may highlight ways in which it can be improved. By testing the following hypotheses we aim to contribute to the applied research in health-related quality of life in a setting with gastric banding patients.

Having high expectations is associated with low health-related quality of life at baseline

Fulfilment of expectations to changes in general well-being as a result of weight loss is associated with health-related quality of life

Health-related quality of life is improved 5 years after gastric banding

Materials and Methods

Subjects

The study was conducted as a prospective cohort study of morbidly obese subjects with follow-up 5 years after gastric banding. All subjects who underwent gastric banding at Aalborg Hospital in 2003 were invited to participate in the study. The criteria for surgery were age between 20 and 60 years, BMI ≥ 40 kg/m2 or ≥ 35 kg/m2 with obesity-related morbidities, and no serious illness, former alcohol or drug abuse or active psychosis. Subjects were excluded from follow-up if they had a cancer diagnosis or had the band removed during follow-up.

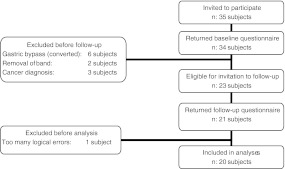

An explanatory letter was mailed to the subjects and the first questionnaire was filled in at the medical examination before surgery. At 5 years follow-up the questionnaire was mailed to the subjects. Subjects who did not return the questionnaire were contacted by phone. Inclusion and exclusion are illustrated in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Inclusion and exclusion

Operative Procedure

All operative procedures were performed by one experienced surgeon working with the same medical team of endocrinologists, gastroenterologists, dieticians and nurses. Laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding is a restrictive procedure. An adjustable silicone band is placed around the stomach near by the cardia. A small pouch of 20 ml is created, thus limiting the food intake. A subcutaneous inflatable reservoir is used to adjust the volume of the band in that way the passage of food from the pouch to the rest of the stomach is adjustable (Belachew et al. 2002; De Jong et al. 2009). Some of the consequences due to gastric banding are perioperative thromboembolism and infection (Livingston 2005). Due to the restrictive procedure the effect of the band can be expressed by vomiting and pain (Freeman et al. 2011). Side effects include band slippage and erosion (Eid et al. 2011; Elder and Wolfe 2007; Singhal et al. 2010). Due to the above listed effects and side effects removal of the band or conversion to gastric bypass can be necessary.

Measures

Anthropometric Measures

Information on weight and height was obtained from the medical record. Height was measured to the nearest 0.5 cm without shoes. Weight was measured to the nearest 100 g with light clothing,

Short Form 36

The generic questionnaire Short Form 36 (SF-36) was used to assess health-related quality of life at baseline and at 5 years follow-up. SF-36 consists of 36 questions addressing eight health concepts. Each of the eight health concepts range from 0 to 100; with higher scores indicating better health-related quality of life (Bjorner and Damsgaard 1997a). The two summary scores, physical component score and mental component score, were adjusted to achieve a community mean value of 50 with a standard deviation of 10 based on U.S. data as recommended by the developers (Bjorner and Damsgaard 1997b). National reference samples are available for the Danish population, and can advantageously be used in comparison with clinical data. The Danish version of SF-36 has been widely validated (Bjorner et al. 1998a; Bjorner et al. 1998c; Bjørner and Damsgaard 1997). In this study the term health-related quality of life designates to measures assessed by SF-36.

Obesity Specific Questions

The obesity specific questions from baseline are shown in Table 1. For each of the six aspects of general well-being the subjects answered questions about their attribution of impairments to morbid obesity and expectations to changes as a result of weight loss.

Table 1.

Obesity specific questions at baseline and follow-up

| Baseline | |

| Aspects of general wellbeing | Attributions of impairments to morbid obesity |

| I) State of health | a) The overweight is the only reason for impairment |

| II) Physical activity | b) The overweight is the main reason for impairment |

| III) Emotional problems | c) The overweight is a possible reason for impairment |

| IV) Pain | d) The overweight is presumably not the reason for impairment |

| V) Social or familial problems | e) The overweight is not the reason for impairment |

| VI) Work capacity | |

| Expectations to changes in aspects of general well-being as a result of weight loss | |

| a) Much better | |

| b) Somewhat better | |

| c) Unchanged | |

| d) Somewhat worse | |

| e) Much worse | |

| Follow-up | |

| Are your expectations to changes in general well-being fulfilled as a result of weight loss | a) Yes |

| b) Somewhat | |

| c) No | |

At follow-up the subjects were asked if their expectations were fulfilled, Table 1.

For analysis, having high expectations was defined as expecting improvements in emotional problems as a result of weight loss, and at the same time not attribute the impairments to morbid obesity. In this study the term general well-being will be used when referring to the obesity specific questions.

Content Validity of the Obesity Specific Questions

To evaluate the face validity of the obesity specific questions an expert panel, consisting of medical doctors, surgeons, nurses and dieticians, was asked to rate the relevance of the questions. Questions which were considered to be very relevant were given four points. Questions which were considered to be somewhat relevant were given three points. Questions which were considered to be rarely relevant were given two points and finally one point was given to questions without relevance. All questions had an average score of at least 3.3 (Data not presented).

Repeatability Reliability of the Obesity Specific Questions

We evaluated the repeatability reliability of the questions by running a test-retest on 16 pre-surgical subjects. The subjects were asked to answer the questions two times with an interval of 2 weeks. Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient of the test-retest showed a linear relationship between the repeated answers.

Attributions of impairments to morbid obesity as regards: state of health (r = 0.72); physical activity (r = 0.52); emotional problems (r = 0.91); pain (r = 0.86); social or familial problems (r = 0.68) and work capacity (r = 0.69).

Expectations to changes as a result of weight loss as regards: state of health (r = 0.69); physical activity (r = 0.75); emotional problems (r = 0.60); pain (r = 0.65); social or familial problems (r = 0.47) and work capacity (r = 0.63).

Statistics

T-test was used to compare continuous variables. Pearson’s correlation coefficient was used to assess the relationship between data from the test-retest. Due to the ordinal nature of data Spearman’s rank correlation was also performed (data not presented). Fishers’ exact test was used to compare proportions. Multiple linear regression was used to assess the association between high expectations and physical component summary and mental component summary. P-values below 5% were considered statistically significant. Analyses were performed using STATA Statistical Software v. 9.2.

Results

Participants from the Follow-up Study

A total of 35 subjects had the gastric band inserted at Aalborg Hospital in 2003. In total 34 subjects (97%) answered the questionnaire before surgery.

At 5-years follow-up three subjects had a cancer diagnosis and were excluded. Eight subjects had the band removed, six of whom had undergone conversion to gastric bypass. 21 subjects answered the questionnaire. Due to logical errors one questionnaire was excluded from analysis, Fig. 1. Characteristics of participants and non-participants are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Baseline characteristics of participants and non-participants

| Participants at follow up | Non-participants at follow-up | |

|---|---|---|

| n | 20 | 14 |

| Age, mean (95% CI), years | 41 (36;45) | 44 (39;50) |

| Gender,male/female | 13/7 | 5/9 |

| Excess weight, mean (95% CI), kga | 78 (67;88) | 91 (78;105) |

| BMI, mean (95% CI), kg/m2 | 50 (47;53) | 55 (51;60)# |

| PCS, mean (95% CI) | 34 (29;40) | 29 (24;34) |

| MCS, mean (95% CI) | 48 (44;53) | 46 (39;54) |

aweight—weight when BMI = 25 kg/m2

# P = 0.04

PCS: physical component summary score at baseline

MCS: mental component summary score at baseline

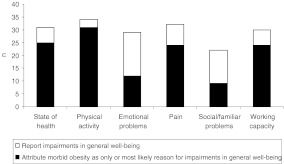

Attributions of Low General Well-being to Morbid Obesity

The subjects’ attributions of impairments to morbid obesity are presented in Fig. 2. The majority of the subjects ascribed their limitations on state of health, physical activity, pain and working capacity to morbid obesity.

Fig. 2.

Subjects’ attributions of impaired general well-being to morbid obesity

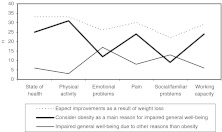

Baseline-Expectations to Changes in General Well-being as a Result of Weight Loss

The vast majority of the subjects expected improvements in several aspects of general well-being as a result of weight loss. Expectations to improvements due to weight loss were also seen among subjects who did not ascribe their limitations to morbid obesity. Expecting improvements as a result of weight loss, even though the bodyweight is not the main course of impaired general well-being, was especially present regarding emotional problems and social problems, Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

Expectations to improvements in general well-being as a result of weight loss

Table 3 shows the estimates of the association between high expectations and mental component summary score at baseline.

Table 3.

| Crude | Adjusteda | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate | (95% CI) | Estimate | (95% CI) | |

| High expectations to changes in general well-being as a result of weight loss | ||||

| No | Ref | – | Ref | – |

| Yes | −8.61 | (−16.25; −0.97) | −8.48 | (−16.72; −0.23) |

aAdjusted for age, gender and BMI at follow-up

Having high expectations to improvements in emotional problems was inversely associated with mental component summary score −8.48 (−16.42; −0.23).

Association Between Fulfilled Expectations and Health-Related Quality of Life at Follow-up

There was no significant association between physical component summary score and having fulfilled expectations, Table 4a; however having expectations fulfilled were associated with higher mental component summary score, Table 4b.

Table 4.

Association between fulfilled expectations and health-related quality of life

| Physical component summary score | Mental component summary score | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crude | Adjusteda | Crude | Adjusteda | |||||||||

| Estimate | (95% CI) | P | Estimate | (95% CI) | P | Estimate | (95% CI) | P | Estimate | (95% CI) | P | |

| Expectations to change in general well-being fulfilled as a result of weight loss | ||||||||||||

| Yes | Ref | – | – | Ref | – | – | Ref | – | – | Ref | – | – |

| Somewhat | −2.44 | (−22.31; 17.43) | 0.799 | −7.87 | (−28.67; 12.93) | 0.431 | −24.63 | (−42.80; −6.45) | 0.011 | −23.90 | (−44.96; −2.85) | 0.029 |

| No | −8.48 | (−21.49; 4.53) | 0.187 | −6.95 | (−20.98; 7.08) | 0.306 | −15.89 | (−27.78; −3.99) | 0.012 | −18.18 | (−32.38; −3.98) | 0.016 |

aAdjusted for age, gender and BMI at follow-up

Health-Related Quality of Life

At baseline the morbidly obese subjects reported low physical component summary score when compared with Danish norm data. At follow-up statistically significant improvements were seen, however the score was still low compared with national norm data.

There was no statistically significant difference between mental component summary score at baseline and follow-up. The mental component summary score was statistically significant low among study participants when compared with national norm data, Table 5.

Table 5.

Health-related quality of life

| Baseline n: 19 | Follow-up n: 19 | National norm n: 784 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | (SD) | Mean | (SD) | Mean | (SD) | |

| PCS | 34.45* | (11.17) | 41.56* # | (11.25) | 52.63 | (7.29) |

| MCS | 48.38** | (9.83) | 45.98 * | (10.73) | 53.55 | (8.29) |

* P < 0.0001 compared to national norm data

** P < 0.05 compared to national norm data

# P < 0.05 compared to baseline

PCS: physical component summary score

MCS: mental component summary score

Discussion

The data support our hypothesis that expectations are inversely associated with health-related quality of life as regards the mental part at baseline. In the statistical model we found evidence to reject the hypothesis of no statistical association between expectations and the mental component summary, P < 0.05.

Furthermore the fulfilment of expectations was associated with better mental health-related quality of life as compared to subjects who reported to have their expectations fulfilled to a lesser extend 5 years after gastric banding. Provided that H0 implies no association between fulfilment of expectations and the mental component summary, we found evidence to reject the hypothesis of no statistical association between fulfilment of expectations and the mental component summary at follow-up.

Finally, we found that physical health-related quality of life is improved 5 years after gastric banding, as stated in the third hypothesis, P < 0.05.

Our data support Calmans’ theory of an association between expectations and health-related quality of life (Calman 1984). Originally the hypothesis was applied in a setting with cancer patients. Though adverse patient groups may differ in aspects related to health-related quality of life, for example satisfaction of needs, reintegration to normal living and medical history we found the hypothesis applicable among morbidly obese subjects. In the present study morbid obesity was considered as the most likely reason for impaired function in physical activity, state of health, working capacity and pain. Obesity has previously been associated with limitations in these aspects of general well-being (Alavinia et al. 2009; Andersen et al. 2003; Bond et al. 2010; Gariepy et al. 2010; Heim et al. 2008; Jinks et al. 2006; King et al. 2008; Neovius et al. 2008; Rodbard et al. 2009). In agreement with previous studies we found a greater impairment in the physical part than the mental part of health-related quality of life among morbidly obese subjects (Adams et al. 2009; Dixon et al. 2001). In previous studies physical health-related quality of life was found to deteriorate with increasing degree of overweight (Dixon et al. 2001; Doll et al. 2000; Huang et al. 2006; Larsson et al. 2002). The present study also demonstrated this association (data not presented). In previous studies of the association between morbid obesity and health-related quality of life, focus has predominantly been on the association between weight loss and subsequent physical improvements, leaving uncertainty about which factors influence the mental part of health-related quality of life. Interestingly, the vast majority of the subjects in our study expected improvements in both emotional and social problems due to weight loss even tough only less than half of the subjects ascribed morbid obesity as the most likely reason for the low emotional or social well-being. Unrealistic expectations to weight loss were previously described among candidates for bariatric surgery (Kaly et al. 2008; Wee et al. 2006); thus, leading to disappointment if the expectations were not fulfilled—despite an outcome that approximated the expected weight (Foster et al. 2001). Our findings indicate that beyond unrealistic expectations to weight loss, the subjects had high expectations to improvements in emotional aspects of general well-being, whereby Calman’s theory remains relevant several decades after he considered high expectations to be of concern when trying to improve quality of life (Calman 1984). Our results indicate that low health-related quality of life among morbidly obese subjects is influenced by various aspects and not merely the degree of obesity. The present results unfold our knowledge about the complexity of health-related quality of life among morbidly obese subjects by suggesting that the context might be influenced by preoperative expectations.

Our study has methodological strengths and limitations which need to be considered. One of the main limitations is the small study population, which implies that the estimates may be subject to random error. In addition our cohort may not represent morbidly obese subjects overall. At baseline all eligible subjects except one agreed to participate in the study. At follow-up some subjects were excluded due to cancer and others since they had the band removed or converted to gastric bypass. However not all of those who were invited to return the questionnaire participated at follow-up. Furthermore, Adams et al. have shown statistically significant differences in health-related quality of life among morbidly obese subjects seeking bariatric surgery and morbidly obese subjects who were not seeking surgery (Adams et al. 2009) consequently the cohort may not represent morbidly obese subjects overall. Furthermore we chose our cohort of gastric banding patients from 2003 to enable a long follow-up time. In Denmark laparoscopic gastric banding was the preferred bariatric operation until about 2005 when laparoscopic gastric bypass was introduced. We can not rule out the possibility that laparoscopic gastric bypass patients might differ from the cohort in the present study.

We think there is little reason to suppose that the estimates are erroneous due to assessment of health-related quality of life since SF-36 is a widely validated questionnaire (Bjorner et al. 1997; Bjorner et al. 1998b; Bjorner et al. 1998a; Bjorner et al. 1998c). The obesity specific questions were evaluated to be highly relevant by a panel of experts. The test-retest produced consistent measurements, whereby repeatable and reproducible results may be provided by the use of the obesity specific questions, when applied repeatedly to subjects in a stable condition. We adjusted our analyses for predefined putative confounders; age, gender and BMI. Including the covariates had no notable effects on the direction of the associations; however the proportion of explained variation was increased in the adjusted models. Even though we adjusted our analyses we can not rule out the possibility that unmeasured confounders explain the observed associations.

In conclusion our study results in three main findings; candidates for gastric banding report morbid obesity as the main reason for impaired physical aspects of general well-being. Some of the subjects expect weight loss to improve emotional parts of their general well-being even though they do not ascribe these problems to morbid obesity. Having high expectations to changes in general well-being as a result of weight loss is associated with low mental health-related quality of life at baseline.

Subjects who reported to have their expectations fulfilled had a better mental health-related quality of life 5 years after gastric banding as compared to their counterparts with unmet expectations.

Finally, the physical part of health-related quality of life was significantly improved 5 years after gastric banding.. These findings suggest that the impact of morbid obesity on the mental aspects of health-related quality of life may be minimised if the subjects adjust their expectations and adapt to their current health status. Hopefully, interventions to counteract unrealistic expectations may help to narrow the gap between hopes and what is obtainable whereby mental health-related quality of life may be improved.

Acknowledgements

We wish to acknowledge the financial support kindly provided by Region Nordjylland; Hertha Christens Foundation; A.P. Moeller and Wife Chastine McKinney Moeller Foundation; The Danish Research Initiative.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

References

- Adams TD, Pendleton RC, Strong MB, Kolotkin RL, Walker JM, Litwin E, et al. Health Outcomes of Gastric Bypass Patients Compared to Nonsurgical, Nonintervened Severely Obese. Obesity. 2009;18(1):121–130. doi: 10.1038/oby.2009.178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alavinia SM, van den Berg TIJ, van Duivenbooden C, Elders LAM, Burdorf A. Impact of work-related factors, lifestyle, and work ability on sickness absence among Dutch construction workers. Scandinavian Journal of Work, Environment & Health. 2009;35(5):325–333. doi: 10.5271/sjweh.1340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersen RE, Crespo CJ, Bartlett SJ, Bathon JM, Fontaine KR. Relationship between body weight gain and significant knee, hip, and back pain in older Americans. Obesity. 2003;11(10):1159–1162. doi: 10.1038/oby.2003.159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belachew M, Belva PH, Desaive C. Long-term results of laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding for the treatment of morbid obesity. Obesity Surgery. 2002;12(4):564–568. doi: 10.1381/096089202762252352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bjorner JB, Damsgaard MT. Design af undersøgelsen. In: Bjørner JB, Bech P, editors. Dansk manual til SF-36. Copenhagen: Lif; 1997. pp. 13–23. [Google Scholar]

- Bjorner JB, Damsgaard MT. Nyudvikling og fremtidsperspektiver. Dansk manual til SF-36. Copenhagen: Lif; 1997. pp. 78–99. [Google Scholar]

- Bjørner JB, Damsgaard MT. Validitet og fortolkning af data. In: Bjørner JB, Bech P, editors. Dansk manual til SF-36. Copenhagen: Lif; 1997. pp. 54–68. [Google Scholar]

- Bjorner JB, Damsgaard MT, Watt T. Reliability and quality of data. In: Bjørner JB, Bech P, editors. Dansk manual til SF-36. Copenhagen: Lif; 1997. pp. 47–53. [Google Scholar]

- Bjorner JB, Damsgaard MT, Watt T, Groenvold M. Tests of data quality, scaling assumptions, and reliability of the Danish SF-36. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 1998;51(11):1001–1011. doi: 10.1016/S0895-4356(98)00092-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bjorner JB, Kreiner S, Ware JE, Damsgaard MT, Bech P. Differential item functioning in the Danish translation of the SF-36. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 1998;51(11):1189–1202. doi: 10.1016/S0895-4356(98)00111-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bjorner JB, Thunedborg K, Kristensen TS, Modvig J, Bech P. The Danish SF-36 health survey: translation and preliminary validity studies. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 1998;51(11):991–999. doi: 10.1016/S0895-4356(98)00091-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bond DS, Jakicic JM, Vithiananthan S, Thomas JG, Leahey TM, Sax HC, et al. Objective quantification of physical activity in bariatric surgery candidates and normal-weight controls. Surgery for Obesity and Related Diseases. 2010;6(1):72–78. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2009.08.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown WV, Fujioka K, Wilson PW, Woodworth KA. Obesity: why be concerned? American Journal of Medicine. 2009;4(Suppl 1):4–11. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2009.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchwald H, Oien DM. Metabolic/Bariatric Surgery Worldwide 2008. Obesity Surgery. 2009;19(12):1605–1611. doi: 10.1007/s11695-009-0014-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calman KC. Quality of life in cancer patients - an hypothesis. Journal of Medical Ethics. 1984;10(3):124–127. doi: 10.1136/jme.10.3.124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carr AJ, Gibson B, Robinson PG. Is quality of life determined by expectations or experience? BMJ (Clinical research ed.) 2001;322(7296):1240–1243. doi: 10.1136/bmj.322.7296.1240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choban PS, Onyejekwe J, Burge JC, Flancbaum L. A health status assessment of the impact of weight loss following Roux-en-Y gastric bypass for clinically severe obesity. Journal of the American College of Surgeons. 1999;188(5):491–497. doi: 10.1016/S1072-7515(99)00030-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Jong JR, van Ramshorst B, Gooszen HG, Smout AJPM, Tiel-Van Buul MMC. Weight loss after laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding is not caused by altered gastric emptying. Obesity Surgery. 2009;19(3):287–292. doi: 10.1007/s11695-008-9746-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixon JB, Dixon ME, O’Brien PE. Quality of life after lap-band placement: influence of time, weight loss, and comorbidities. Obesity Research. 2001;9(11):713–721. doi: 10.1038/oby.2001.96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doll HA, Petersen SE, Stewart-Brown SL. Obesity and physical and emotional well-being: associations between body mass index, chronic illness, and the physical and mental components of the SF-36 questionnaire. Obesity Research. 2000;8(2):160–170. doi: 10.1038/oby.2000.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eid I, Birch DW, Sharma AM, Sherman V, Karmali S. Complications associated with adjustable gastric banding for morbid obesity: a surgeon’s guides. Canadian Journal of Surgery. 2011;54(1):61–66. doi: 10.1503/cjs.015709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elder KA, Wolfe BM. Bariatric surgery: a review of procedures and outcomes. Gastroenterology. 2007;132(6):2253–2271. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.03.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foster GD, Wadden TA, Phelan S, Sarwer DB, Sanderson RS. Obese patients’ perceptions of treatment outcomes and the factors that influence them. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2001;161(17):2133–2139. doi: 10.1001/archinte.161.17.2133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman L, Brown WA, Korin A, Pilgrim CH, Smith A, Nottle P. An approach to the assessment and management of the laparoscopic adjustable gastric band patient in the emergency department. Emergency Medicine Australasia. 2011;23(2):186–194. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-6723.2011.01396.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gariepy G, Wang J, Lesage A, Schmitz N. The interaction of obesity and psychological distress on disability. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. 2010;45(5):531–540. doi: 10.1007/s00127-009-0090-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heim N, Snijder MB, Deeg DJH, Seidell JC, Visser M. Obesity in older adults is associated with an increased prevalence and incidence of pain. Obesity. 2008;16(11):2510–2517. doi: 10.1038/oby.2008.407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helmio, M., Salminen, P., Sintonen, H., Ovaska, J., & Victorzon, M. (2011). A 5-year prospective quality of life analysis following laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding for morbid obesity. Obesity Surgery. doi:10.1007/s11695-011-0425-y. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Huang IC, Frangakis C, Wu AW. The relationship of excess body weight and health-related quality of life: evidence from a population study in Taiwan. International Journal of Obesity. 2006;30(8):1250–1259. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0803250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jinks, C., Jordan, K., & Croft, P. (2006). Disabling knee pain–another consequence of obesity: results from a prospective cohort study. BMC Public Health. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-6-258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Kaly P, Orellana S, Torrella T, Takagishi C, Saff-Koche L, Murr MM. Unrealistic weight loss expectations in candidates for bariatric surgery. Surgery for obesity and related diseases : official journal of the American Society for Bariatric Surgery. 2008;4(1):6–10. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2007.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karlsson J, Taft C, Ryden A, Sjostrom L, Sullivan M. Ten-year trends in health-related quality of life after surgical and conventional treatment for severe obesity: the SOS intervention study. International Journal of Obesity. 2007;31(8):1248–1261. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0803573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King WC, Belle SH, Eid GM, Dakin GF, Inabnet WB, Mitchell JE, et al. Physical activity levels of patients undergoing bariatric surgery in the longitudinal assessment of bariatric surgery study. Surgery for Obesity and Related Diseases. 2008;4(6):721–728. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2008.08.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsson U, Karlsson J, Sullivan M. Impact of overweight and obesity on health-related quality of life - a Swedish population study. International journal of obesity and related metabolic disorders : journal of the International Association for the Study of Obesity. 2002;26(3):417–424. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0801919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavie CJ, Milani RV, Ventura HO. Obesity and cardiovascular disease: risk factor, paradox, and impact of weight loss. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2009;53(21):1925–1932. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.12.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livingston EH. Complications of bariatric surgery. The Surgical Clinics of North America. 2005;85(4):853–68. doi: 10.1016/j.suc.2005.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller-Riemenschneider F, Reinhold T, Berghofer A, Willich SN. Health-economic burden of obesity in Europe. European Journal of Epidemiology. 2008;23(8):499–509. doi: 10.1007/s10654-008-9239-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munoz DJ, Lal M, Chen EY, Mansour M, Fischer S, Roehrig M, et al. Why patients seek bariatric surgery: a qualitative and quantitative analysis of patient motivation. Obesity Surgery. 2007;17(11):1487–1491. doi: 10.1007/s11695-008-9427-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neovius K, Johansson K, Rössner S, Neovius M. Disability pension, employment and obesity status: a systematic review. Obesity Reviews. 2008;9(6):572–581. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2008.00502.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Padwal R, Klarenbach S, Wiebe N, Birch D, Karmali S, Manns B, et al. Bariatric surgery: a systematic review and network meta-analysis of randomized trials. Obesity Reviews. 2011;12(8):602–621. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2011.00866.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodbard HW, Fox KM, Grandy S. Impact of Obesity on Work Productivity and Role Disability in Individuals With and at Risk for Diabetes Mellitus. American Journal of Health Promotion. 2009;23(5):353–360. doi: 10.4278/ajhp.081010-QUAN-243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singhal R, Bryant C, Kitchen M, Khan KS, Deeks J, Guo B, et al. Band slippage and erosion after laparoscopic gastric banding: a meta-analysis. Surgical Endoscopy. 2010;24(12):2980–2986. doi: 10.1007/s00464-010-1250-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sirgy MJ. A Quality of Life Theory Derived from Maslow’s Developmental Perspective. American Journal of Economics and Sociology. 1986;45(3):329–342. doi: 10.1111/j.1536-7150.1986.tb02394.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sirgy MJ. Handbook of quality-of-life research: An ethical marketing perspective. Netherlands: Springer; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Sjostrom L, Narbro K, Sjostrom CD, Karason K, Larsson B, Wedel H, et al. Effects of bariatric surgery on mortality in Swedish obese subjects. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2007;357(8):741–752. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa066254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wee CC, Jones DB, Davis RB, Bourland AC, Hamel MB. Understanding patients’ value of weight loss and expectations for bariatric surgery. Obesity Surgery. 2006;16(4):496–500. doi: 10.1381/096089206776327260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]