Abstract

Background

Skeletal muscle structure and function are dependent on intact Richard Butler, Ph.D. innervation. Prolonged muscle denervation results in irreversible muscle fiber James R. Bain, M.D. atrophy, connective tissue hyperplasia, and deterioration of muscle spindles, Margaret Fahnestock, Ph.D. specialized sensory receptors necessary for proper skeletal muscle function. The protective effect of temporary sensory innervation on denervated muscle, before motor nerve repair, has been shown in the rat. Sensory-protected muscles exhibit less fiber atrophy and connective tissue hyperplasia and maintain greater functional capacity than denervated muscles. The purpose of this study was to determine whether temporary sensory innervation also protects muscle spindles from degeneration.

Methods

Rat tibial nerve was transected and repaired with either the saphenous or the original transected nerve. Negative controls remained denervated. After 3 to 6 months, the electrophysiologic response of the nerve to stretch in the rat gastrocnemius muscle was measured (n = 3 per group). After the animals were euthanized, the gastrocnemius muscle was removed, sectioned, stained, and examined for spindle number (n = 3 per group) and morphology (one rat per group). Immunohistochemical assessment of muscle spindle innervation was examined in four additional animals.

Results

Significant deterioration of muscle spindles was seen in denervated muscle, whereas in muscle reinnervated with the tibial or the saphenous nerve, spindle number and morphology were improved. Histologic and functional evidence of spindle reinnervation by the sensory nerve was obtained.

Conclusion

These findings add to the known means by which motor or sensory nerves exert protective effects on denervated muscle, and further promote the use of sensory protection for improving the outcome after peripheral nerve injury.

Skeletal muscle function and structural integrity are dependent on intact innervation. Major peripheral injury can sever nerves and result in muscle denervation, causing an immediate loss of muscle function and progressive muscle atrophy. Microsurgical repair within 2 months of injury can essentially reverse the loss of muscle mass and result in full functional recovery.1– 4 However, chronic denervation results in irreversible structural damage, including extrafusal fiber necrosis, connective tissue hyperplasia, and deterioration of the muscle spindles, leading to poor reinnervation and functional recovery.1,4,5 Muscle spindles, specialized sensory receptors having both motor efferent and sensory afferent innervation, function in detecting and transmitting information regarding the overall amount of muscle stretch and stretch velocity during limb movement, which is essential for proper skeletal muscle function.6 Sensory afferent innervation plays the predominant role in the assembly and differentiation of intrafusal fibers in the rat during development, as deefferented (sensory but not motor innervation is maintained) newborn rat spindles develop the full complement of differentiated intrafusal fibers.7,8 Denervation of the mature muscle spindle results in shrinkage of intrafusal fibers and disappearance of intracapsular space in the equatorial region of the spindle. In long-term–denervated muscle, most of the muscle spindles atrophy and eventually disappear.9

Over time, denervated muscles become increasingly less receptive to regenerated motor axons that reach the muscle because of a significant loss of viable muscle cells resulting from the combined effects of increasing fiber necrosis, connective tissue hyperplasia, and exhaustion of satellite cell regeneration.1,5,10 The loss of neural input, including neurotransmitters, neurotrophic factors, and other signals, promotes muscle fiber atrophy and thus reduces receptivity to regenerated axons.5 The deterioration of muscle spindles may also contribute to poor functional recovery following prolonged denervation.

We and others have shown that a sensory nerve grafted to a denervated muscle helps to maintain the structural and functional integrity of muscle awaiting successful motor reinnervation.2,4,5,11,12 This strategy, called “sensory protection,” uses a readily available sensory nerve to temporarily innervate a denervated muscle until the injured motor nerves regenerate and become available for surgical reconstruction. We have shown that temporary sensory innervation improves functional recovery of denervated skeletal muscle following reinnervation.2,4 We have also shown that sensory-protected muscles exhibit a significant preservation of muscle structure in comparison with unprotected denervated controls.5 Sensory protection minimizes two of the three major structural consequences of chronic denervation: fiber necrosis and connective tissue hyperplasia. The goal of this study was to determine whether temporary sensory protection can also protect muscle spindles from deterioration and therefore to further investigate the efficacy of this strategy in improving the clinical outcome for peripheral nerve injury.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals

The experiments were performed on 25 adult Lewis rats (Charles River, Sherbrooke Quebec, Canada) weighing 200 to 250 g. Of these rats, nine were used for histologic assessment of the gastrocnemius muscle, four were used for immunohistochemical assessment, and the remaining 12 were used for electrophysiologic assessment. Housing, surgical procedures, administration of analgesics, and assessments were performed according to the Canadian Council on Animal Care Guidelines. Animal use protocols were approved by the Animal Care Committee at McMaster University.

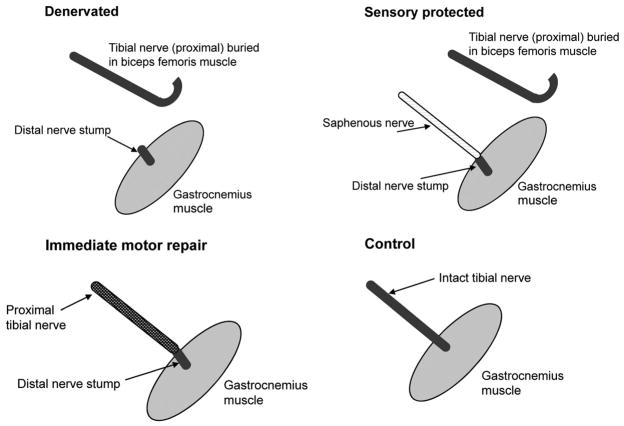

Rats were assigned randomly to one of three types of surgical intervention (Fig. 1): (1) unilateral transection of the tibial nerve (motor and sensory) from the gastrocnemius muscle (denervated group); (2) unilateral transection of the tibial nerve innervating the gastrocnemius muscle, with immediate microsurgical repair of the tibial nerve (motor and sensory) (immediate repair group) to control for the surgical transection and repair; and (3) unilateral transection of the tibial nerve from the gastrocnemius muscle, with surgical transfer of the saphenous nerve (sensory) to the tibial nerve stump (sensory-protected group). The unoperated contralateral gastrocnemius muscles served as controls.

Fig. 1.

Drawings depicting the experimental groups. The first group of animals (above, left) was denervated and not repaired; the second group (above, right) had sensory protection with saphenous nerve transfer from its normal target, the skin, to the distal stump of the tibial nerve; the third group (below, left) had immediate division and microsuture of the tibial nerve. (Above, left and above, right) The tibial nerve was sutured to the biceps femoris muscle to prevent reinnervation of the gastrocnemius muscle. The contralateral, unoperated leg served as a control in each experimental cohort (below, right).

Surgical Procedures

All operations were performed under sterile conditions using a Zeiss operating microscope (Carl Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany). Anesthesia was induced using 5% isoflurane gas and maintained with inhalation isoflurane at 2 to 3%. In all groups, the tibial nerve in the posterior thigh was exposed using sterile microsurgical technique and transected approximately 13 mm from the point of nerve entry into the lateral head of the gastrocnemius. The free nerve end (proximal stump) was then sutured onto the surface of the biceps femoris muscle to avoid spontaneous reinnervation of tibial nerve axons into the gastrocnemius muscle.4

In group 1 rats (denervated), no further surgery was performed. In group 2 rats (immediate repair), the tibial nerve was transected and sutured immediately. In group 3 rats (sensory-protected), the ipsilateral saphenous nerve was freed from the saphenous vein in the medial aspect of the thigh and then guided through an opening in the medial thigh muscles until it lay in the popliteal fossa adjacent to the distal tibial nerve stump, to which it was then sutured.

Postoperatively, 5 cc of saline was administered subcutaneously to replenish fluid loss, analgesia (buprenorphine 0.03 mg/kg) was administered subcutaneously, and animals were kept warm with a heating pad. All efforts were made to minimize animal suffering.

At 3 months postoperatively, functional electrophysiologic assessment was conducted on 12 animals (three animals per group, including three animals in a control, unoperated group) to measure tibial and saphenous nerve discharge in response to muscle stretch. At 6 months postoperatively, a separate set of nine animals (three animals per group, with contralateral limbs serving as unoperated controls) were perfused with 4% paraformaldehyde solution in 0.1 M phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) for histologic assessment. For immunohistochemical assessment, muscles from a different set of four rats (one per group) were excised without perfusion and frozen at − 80°C.

Histologic Assessment of Muscle Spindle Number and Morphology

After perfusion, lateral gastrocnemius muscles were postfixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin solution (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, Mo.) for approximately 48 hours at room temperature. Each muscle was then cut transversely into 6-mm-thick segments. The number of segments per muscle varied from three to eight. Each segment was placed individually in a cassette (TRU-FLOW Tissue Cassettes; Fisher Scientific, Markham, Ontario, Canada) with the left transverse face up so that all segments were kept in the same orientation and again immersed in 10% neutral buffered formalin for a period of 1 to 2 days. Muscles were then dehydrated through graded ethanol and embedded in paraffin, and 10-μm transverse serial sections were mounted on Aptex-coated slides (Goldline microscope slides; VWR International, Mississauga, Ontario, Canada).

Every tenth section was deparaffinized, cleared in xylenes, and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (Sigma-Aldrich). Coverslipped sections were examined under 20× magnification using an Axio-vision 3.1 microscope, camera, and software (Carl Zeiss). The criteria used to identify spindles included (1) the presence of a connective tissue capsule and (2) a cluster of encapsulated intrafusal fibers smaller than the extrafusal fibers of skeletal muscle. Images of representative spindles from each of the four groups of muscles were taken. Muscle spindle diameter and length were measured manually, and the total number of spindles was counted in each muscle. Muscle spindle location and length were recorded to ensure that muscle spindles were counted only once.

Immunohistochemical Assessment of Muscle Spindle Innervation

Frozen lateral gastrocnemius muscles were sectioned using a Leica CM3050 S cryostat (Leica Microsystems, Inc., Bannockburn, Ill.) at a thickness of 10 μm for transverse sections and a thickness of 20 μm for longitudinal sections. Immunohistochemistry was performed by first blocking sections for 1 hour in 5% normal goat serum. Sections were then incubated with a mixture of two primary antibodies for 1 hour at room temperature: a rabbit polyclonal antibody that recognizes the major neurofilament subunit NF-H (Chemicon International, Inc., Temecula, Calif.), and monoclonal antibody S4613 that recognizes slow myosin heavy chain expressed in intrafusal bag fibers of muscle spindles (a gift from Dr. Douglas Wright, University of Kansas). Sections were then incubated with a mixture of two secondary antibodies for 1 hour at room temperature: a fluorescein isothiocyanate– conjugated goat anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, Inc., West Grove, Pa.; diluted 1:200 in phosphate-buffered saline) and a Texas Red dye– conjugated goat anti-mouse immunoglobulin G (Jackson ImmunoResearch; diluted 1:100 in phosphate-buffered saline). Muscle sections were viewed and photographed using a Zeiss Axiovert 100M confocal microscope and LSM 510 META software.

Functional Electrophysiologic Assessment of Nerve Response to Stretch

Anesthesia was induced using 5% isoflurane gas and maintained at 2 to 3%. Under isothermic conditions, the gastrocnemius muscle was exposed, as were the saphenous and sciatic nerves. Hooked needle recording electrodes were placed around the tibial and/or the saphenous nerve approximately 1.5 cm proximal to the repair site. Peroneal and sural nerve branches were divided. The tibia was stabilized and the maximum foot dorsiflexion blocked; then, a rapid dorsal deflection of the paw was administered manually to a maximum of 90 degrees using a protractor and endplate to ensure that a standardized muscle stretch was administered. The resulting nerve action potential was recorded from the tibial nerve (control, immediate repair, and denervated groups) postoperatively. For the sensory protection group, the recording electrodes were placed around the saphenous nerve. Control recordings were also obtained from the saphenous nerve from three naive animals and on the unoperated contralateral side for three animals, and no recordable action potentials arose from the nerve as a result of muscle stretch. The previously severed and buried tibial nerve in the denervated group of animals was also tested for a response to stretch, and no action potentials were detectable. Five nerve action potentials were captured, recorded, and averaged from each animal (NeuroMax; Excel-Tech, Oakville, Ontario, Canada). After completion of the studies, the nerves were divided and retested, and no action potentials were recorded after the division.

Statistical Analysis

A one-way analysis of variance with a post hoc Dunnett T3 test was performed to determine the significance of any differences between group means for spindle number and diameter. Significance was defined as p < 0.05. A one-way analysis of variance with post hoc t test was performed to determine the significance of any differences between group means for electrophysiologic stretch responses.

RESULTS

The number of muscle spindles in each muscle was counted by analyzing every tenth section so that each muscle was surveyed for spindles throughout its entire length. The mean number of muscle spindles in lateral gastrocnemius muscles from each experimental group was determined (Table 1). Three muscles per group were analyzed. Sensory-protected muscles exhibited a significantly greater number of spindles than denervated muscles and were not significantly different from muscles repaired immediately or control muscles.

Table 1.

Number of Muscle Spindles and Spindle Diameter in the Adult Rat Gastrocnemius Muscle 6 Months after Denervation and Various Treatments*

| Control | Immediate Repair | Sensory-Protected | Denervated | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of muscle spindles* | 23.67 ± 2.52 | 20.33 ± 2.52 | 18.67 ± 3.22 | 6.67 ± 2.08† |

| Spindle diameter (mean ± SEM), μm | 42.29 ± 3.04 | 36.50 ± 3.16 | 16.53 ± 1.96‡ | 10.00 ± 1.29§ |

| No. of spindles measured | 24 | 16 | 15 | 6 |

Spindle numbers were counted 6 months after surgery; n = 3 rats per group.

p < 0.05 for denervated compared with control, immediate repair, and sensory protected groups. There were no differences among the other groups.

p < 0.001 compared with control and with immediate repair groups.

p < 0.05 compared with control, immediate repair, and sensory-protected groups. Spindles were measured in one rat per group.

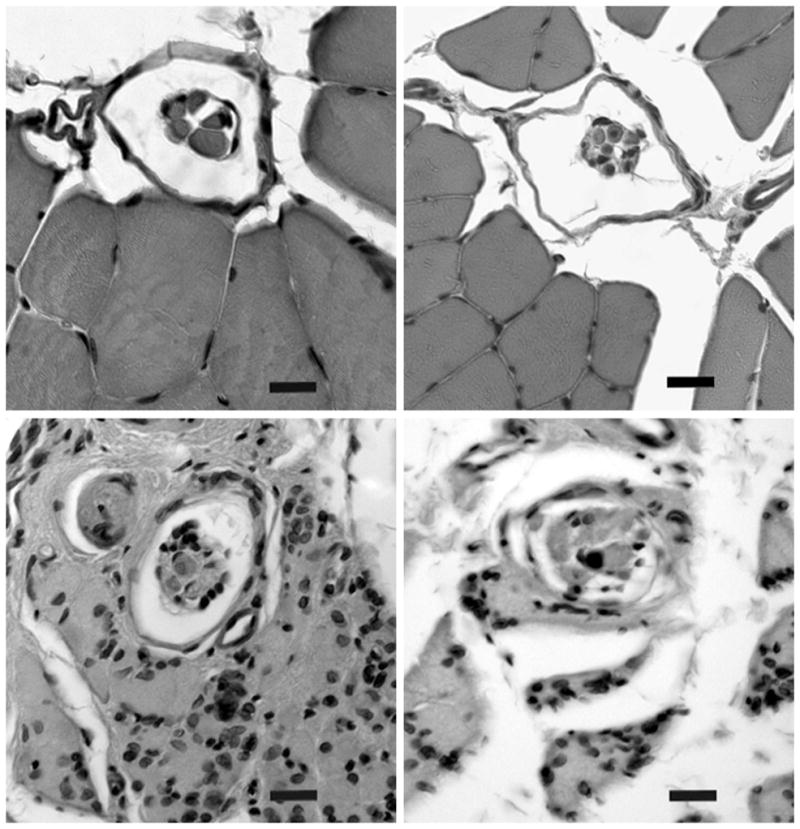

Representative cross-sections of spindles from each group are shown in Figure 2. Normal spindles had a clearly defined capsule and capsular space and clearly defined intrafusal fibers (Fig. 2, above, left). Muscle spindles from the immediate repair muscles (Fig. 2, above, right) appeared similar in size and shape, although they tended to have somewhat distorted capsules. Compared with normal control spindles, there was less of a gap at the equator between the capsule and the intrafusal fibers, which appeared normal. Sensory-protected muscle spindles (Fig. 2, below, left) had a narrower intracapsular space at the equator and were smaller than control and immediate repair spindles. Although they also had less space between the capsule and intrafusal fibers, the appearance was of intact connective tissue capsules and clearly defined intrafusal fibers. Denervated spindles (Fig. 2, below, right) were considerably smaller than control and immediate repair spindles and smaller than sensory-protected spindles. The connective tissue capsule of these spindles was less well defined than in other groups, and the intrafusal fibers were quite small and difficult to distinguish. Overall, the denervated spindles appeared to be in the process of disintegration as defined by the disappearance of discernible intrafusal fibers.

Fig. 2.

Micrographs of representative muscle spindles. Unoperated control (above, left), immediate repair (above, right), sensory-protected (below, left), and denervated (below, right) sections. These 10-μm transverse serial sections through the equatorial region were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (original magnification, ×400). Scale bar = 10 μm.

The extrafusal fiber nuclei of normal and immediate repair muscles were located in the muscle cell periphery and appeared flattened, indicating the presence of condensed chromatin. The nuclei in denervated and sensory-protected muscles were dispersed throughout the extrafusal fibers and were rounder, suggestive of nuclear activity. Similar nuclear changes have been observed in skeletal muscle denervated for 2 weeks to 1 month.14

Muscle spindle diameter was measured at the equatorial region, the thickest portion of this fusiform-shaped receptor. The connective tissue capsule that surrounds muscle spindles does not span the entire length of a muscle spindle but surrounds only the equatorial and juxtaequatorial regions. Sensory-protected spindles were significantly smaller in equatorial diameter than normal control and immediate repair spindles. However, sensory-protected spindles were significantly larger in diameter when compared with denervated muscle spindles (Table 1).

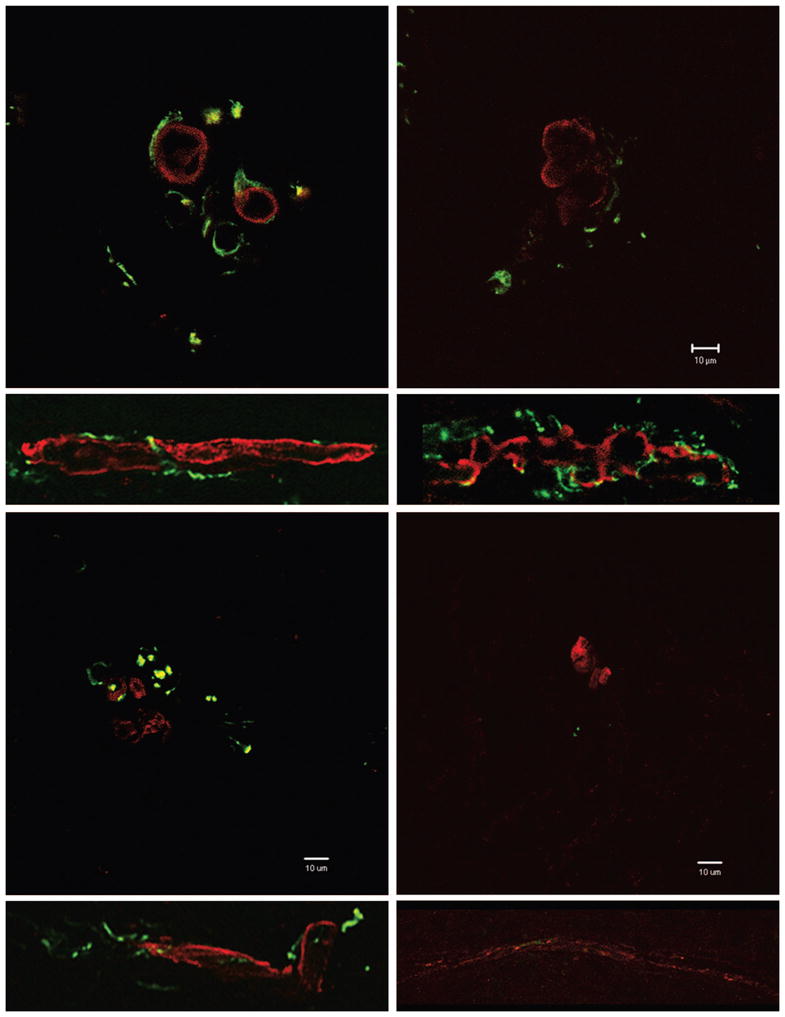

Double-label immunohistochemistry against the major neurofilament subunit NF-H expressed in neuronal tissue and the slow myosin heavy chain expressed in intrafusal bag fibers was used to examine the reinnervation of muscle spindles. In control, unoperated animals, tibial sensory afferents make annulospiral endings on bag fibers (Fig. 3, above, left). Chain fibers are not labeled by this antibody and were not visualized. Representative cross-sections and longitudinal sections of spindles in each group show that sensory afferents of both the tibial (Fig. 3, above, right) and saphenous (Fig. 3, below, left) nerves regenerate into the gastrocnemius muscle and make physical contact with intrafusal bag fibers. Denervated spindles consist of deteriorating intrafusal fibers devoid of innervation (Fig. 3, below, right).

Fig. 3.

Muscle spindle innervation in unoperated control (above, left), immediate repair (above, right), sensory-protected (below, left), and denervated (below, right) groups. Ten-micron transverse and 20-μm longitudinal sections of muscle spindles from the lateral gastrocnemius muscle were stained with antibodies against slow-tonic myosin heavy chain (red). Nerve afferents were identified using antisera against neuro-filament heavy chain (green). Transverse sections, original magnification, ×630; scale bar = 10 μm. Longitudinal sections, original magnification, ×200; not shown to scale.

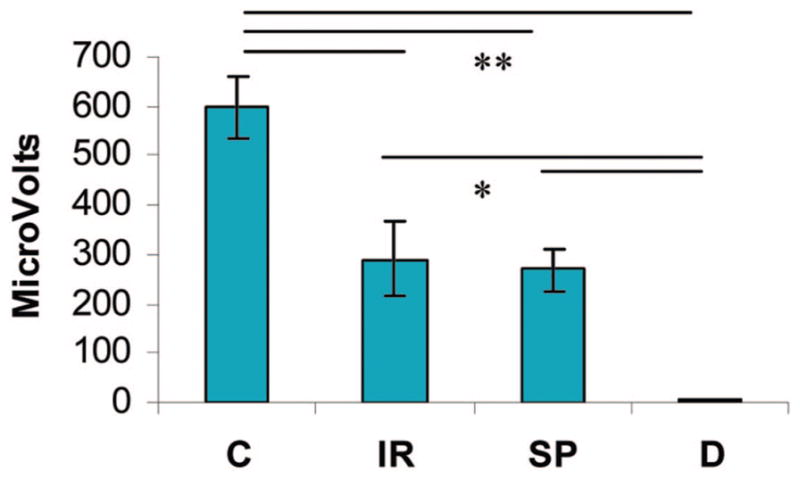

Nerve conduction was measured across groups following a standardized gastrocnemius muscle stretch stimulation. The response to stretch of the gastrocnemius muscle was recorded from the tibial nerve in six control animals and three immediate repair animals, from the saphenous nerve in three sensory-protected animals, and from the transected buried tibial nerve in three denervated animals (Fig. 4). A one-way analysis of variance with post hoc t test demonstrated significant differences between groups (p < 0.001). The amplitude of the action potentials was significantly greater in control, unoperated animals than in immediate repair and sensory-protected animals. There was no significant difference between immediate repair and sensory-protected animals, and both were significantly greater than denervated animals. Very small action potentials were measurable from two of the denervated animals. No responses were recordable from the contralateral control saphenous nerve following ankle dorsiflexion or from the ipsilateral nerves following transection.

Fig. 4.

Electrophysiologic response of the nerve to stretch in the rat gastrocnemius muscle 3 months after denervation and various treatments. Mean amplitude of the response (in microvolts) ± SEM; n = 3 per group except n = 6 for the control group. C, control; IR, immediate repair; SP, sensory-protected; D, denervated. Significant differences between denervated and all other groups and between control and all other groups, but no differences between immediate repair and sensory-protected groups (analysis of variance followed by post hoc t test; *p < 0.05; **p < 0.005).

DISCUSSION

The model of sensory protection in the present study used the lateral gastrocnemius muscle because it has been previously reported that, in rabbits and rats, sprouts of transposed motor nerve form new neuromuscular junctions in the aneural lateral head of denervated gastrocnemius muscle.15 Therefore, this region of the gastrocnemius muscle can be used to demonstrate the potential of peripheral nerve reinnervation and recovery following injury. The response of the gastrocnemius muscle to denervation and sensory protection has also been well characterized,4,5 and this muscle is large and thus provides ample tissue for analysis.

No previous studies have counted the number of muscle spindles in adult rat lateral gastrocnemius muscle. In 1992, Kucera and Walro calculated an average of 19 spindles in the medial gastrocnemius muscle of newborn rats.16 Our average of 24 spindles in normal adult lateral gastrocnemius muscles is consistent with these data, despite the difference in age between the two sample populations. With increasing age, not only does the number of spindles remain constant but their distribution pattern also stays relatively fixed.17 Therefore, although adult rats were chosen for this study, rats at any developmental stage could have been used to assess the impact of sensory protection on the muscle spindle.

It is important to note that the normal control muscles were obtained from the unoperated hind limbs of the rats contralateral to the operated hind limb. Having had surgery on one hind limb may have caused the animals to rely more heavily on the other, unoperated hind limb; however, there is currently no evidence to suggest that exercise can alter muscle spindle number or size in skeletal muscle in the normal animal. As mentioned above, the numbers and distribution of spindles remains fixed.17 The immediate repair group, in which the mixed motor and sensory tibial nerve was repaired immediately, was included to control for the effects of denervation and surgical repair. Thus, the question we asked was whether repair with a sensory nerve is as effective as repair with a mixed motor nerve.

We found a significant difference in spindle number across the four experimental groups. Denervated muscle exhibited a dramatically reduced number of muscle spindles 6 months following denervation, consistent with previous reports.9 In contrast, the number of spindles in sensory-protected muscle, although less than in the control group, was much greater than in denervated muscle and was not significantly different from the number of spindles in the immediate repaired tibial nerve group, suggesting that sensory nerve is sufficient and motor innervation is not required to protect muscle spindles against atrophy and degeneration.

Denervated spindles were significantly atrophied as indicated by reduced diameter compared with control spindles, and their intrafusal fibers were small and difficult to distinguish. By contrast, sensory-protected spindles consisted of clearly defined, intact intrafusal fibers with considerable intracapsular space. The equatorial diameter of the connective tissue capsule of sensory-protected spindles was greater than the equatorial diameter of denervated spindles, although the diameter of sensory-protected spindles remained significantly less than normal and was intermediate between denervated and immediate repair. This intermediate condition is similar to that found in the functional reinnervation of sensory-protected muscle: better than denervated but not as effective as immediate motor repair.4 Thus, sensory protection improves spindle number, intrafusal fiber definition, and capsule diameter following prolonged denervation.

Intrafusal fibers of sensory-protected muscle spindles remained intact despite slight atrophy of the extrafusal muscle fibers, whereas both intrafusal and extrafusal fibers of denervated muscle appeared to be in the process of deterioration. We have previously found that in denervated muscle there is a substantial shift in extrafusal fiber-type distribution toward slow-twitch properties, with sparing of fast-twitch fibers in sensory-protected muscle.5 Together, these findings suggest that sensory axons target intrafusal spindle fibers and fast-twitch extrafusal fibers, preventing their loss during denervation.

Previous studies have reported that sensory fibers of a skeletal muscle’s original nerve can regenerate and reinnervate spindles after nerve crush and nerve section, albeit with an abnormal annulospiral innervation pattern, with few reinnervated sensory fibers responding to stretch normally.18 –23 In contrast to previously published work, this study investigated sensory reinnervation of skeletal muscle spindles by the saphenous nerve, a foreign, cutaneous nerve. Our results suggest that cutaneous sensory fibers, like the native sensory nerve, are capable of regenerating into gastrocnemius muscle to make physical connections with intrafusal spindle fibers. We show that saphenous fibers are capable of reinnervating intrafusal spindle fibers in an annulospiral-like manner. Furthermore, our data suggest that the connection between saphenous nerve and spindle is functional, as there is an obvious response to stretch (and therefore muscle spindle reinnervation) from the saphenous nerve in sensory-protected muscle. It has yet to be determined whether it is this functional contact between saphenous afferents and intrafusal fibers, or other signals provided by sensory neurons, that maintains muscle spindle integrity in sensory-protected skeletal muscle.

Neurotrophin-3 mRNA is expressed by muscle spindles but decreases on denervation.9 We have verified that spindle-derived neurotrophin-3 protein levels decrease following our manipulations (data not shown). Neurotrophin-3 likely does not, therefore, play a role in muscle protection. To our knowledge, no other trophic factors are known to be released by muscle spindles.

The reinnervation target during sensory protection has been a subject of investigation since early work describing functional improvements in reinnervation after sensory-to-motor nerve transfer.4,12 Patients have reported a perception of muscle tension (stretch) with muscle activity during sensory protection and improved function (walking) resulting from improvement in ankle position even before significant changes in motor recovery of the targets.24 The molecular and cellular mechanisms responsible for the functional extrafusal fiber recovery are under investigation. The data presented here suggest that muscle spindles represent one reinnervation target of the sensory nerve and support the use of sensory protection to preserve skeletal muscle structure and function, including prevention of muscle spindle degeneration, during prolonged denervation following injury.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grant no. MOP-64270 from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (to M.F. and J.R.B.) and a Canadian Institutes of Health Research summer scholarship (to A.E.).

Footnotes

Disclosure: None of the authors has a financial interest in any of the products, devices, or drugs mentioned in this article.

Presented at the 16th Annual Scientific Meeting of the American Society for Peripheral Nerve, in Beverly Hills, California, January 11 through 13, 2008.

References

- 1.Fu SY, Gordon T. Contributing factors to poor functional recovery after delayed nerve repair: Prolonged denervation. J Neurosci. 1995;15:3886–3895. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-05-03886.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hynes NM, Bain JR, Thoma A, Veltri K, Maguire JA. Preservation of denervated muscle by sensory protection in rats. J Reconstr Microsurg. 1997;13:337–343. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1006413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kobayashi J, Mackinnon SE, Watanabe O, et al. The effect of duration of muscle denervation on functional recovery in the rat model. Muscle Nerve. 1997;20:858–866. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4598(199707)20:7<858::aid-mus10>3.0.co;2-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bain JR, Veltri KL, Chamberlain D, Fahnestock M. Improved functional recovery of denervated skeletal muscle after temporary sensory nerve innervation. Neuroscience. 2001;103:503–510. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(00)00577-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Veltri K, Kwiecien JM, Minet W, Fahnestock M, Bain JR. Contribution of the distal nerve sheath to nerve and muscle preservation following denervation and sensory protection. J Reconstr Microsurg. 2005;21:57–70. doi: 10.1055/s-2005-862783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Matthews PBC. Mammalian Muscle Receptors and their Central Actions. London: Edward Arnold; 1972. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zelena J, Soukup T. The differentiation of intrafusal fiber types in rat muscle spindles after motor denervation. Cell Tissue Res. 1974;153:115–136. doi: 10.1007/BF00225450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Milburn A. Stages in the development of cat muscle spindles. J Embryol. 1984;82:177–216. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Copray JC, Brouwer N. Neurotrophin-3 mRNA expression in rat intrafusal muscle fibres after denervation and reinnervation. Neurosci Lett. 1997;236:41–44. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(97)00747-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Irintchev A, Draguhn A, Wernig A. Reinnervation and recovery of mouse soleus muscle after long-term denervation. Neuroscience. 1990;39:231–243. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(90)90236-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang H, Gu Y, Xu J, Shen L, Li J. Comparative study of different surgical procedures using sensory nerves or neurons for delaying atrophy of denervated skeletal muscle. J Hand Surg (Am) 2001;26:326–331. doi: 10.1053/jhsu.2001.22522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Papakonstantinou KC, Kamin E, Terzis JK. Muscle preservation by prolonged sensory protection. J Reconstr Microsurg. 2002;18:173–182. doi: 10.1055/s-2002-28469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wright DE, Williams JM, McDonald JT, Carlsten JA, Taylor MD. Muscle-derived neurotrophin-3 reduces injury-induced proprioceptive degeneration in neonatal mice. J Neurobiol. 2002;50:198–208. doi: 10.1002/neu.10024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tower S. The reaction of muscle to denervation. Physiol Rev. 1939;19:1–48. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brunelli G. Direct neurotization of severely damaged muscles. J Hand Surg (Am) 1982;7:572–579. doi: 10.1016/s0363-5023(82)80106-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kucera J, Walro J. Formation of muscle spindles in the absence of motor innervation. Neurosci Lett. 1992;145:47–50. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(92)90200-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Butler R. The organization of muscle spindles in the tenuissimus muscle of the cat during late development. Dev Biol. 1980;77:191–212. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(80)90466-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thulin CA. Bioelectrical characteristics of regenerated fibers in the feline spinal cord. Exp Neurol. 1960;2:533–546. doi: 10.1016/0014-4886(60)90030-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bessou P, Laporte Y, Pages B. Observations on the reinnervation of neuromuscular spindles in cats (in French) C R Seances Soc Biol Fil. 1966;160:408–411. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ip MC, Vrbová G, Westbury DR. The sensory reinnervation of hind limb muscles of the cat following denervation and de-efferentation. Neuroscience. 1977;2:423–434. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(77)90007-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brown MC, Butler RG. An investigation into the site of termination of static gamma fibres within muscle spindles of the cat peroneus longus muscle. J Physiol. 1975;247:131–143. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1975.sp010924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Banks RW, Barker D. Specificities of afferents reinnervating cat muscle spindles after nerve section. J Physiol. 1989;408:345–372. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1989.sp017463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.DeSantis M, Norman WP. Location and completeness of reinnervation by two types of neurons at a single target: The feline muscle spindle. J Comp Neurol. 1993;336:66–76. doi: 10.1002/cne.903360106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bain JR, Hason Y, Veltri KL, Fahnestock M, Quartly C. Clinical application of sensory protection of denervated muscle: Case report. J Neurosurg. 2008;109:955–961. doi: 10.3171/JNS/2008/109/11/0955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]