Abstract

Purpose

Dmp1 (dentin matrix protein1) null mice (Dmp1−/−) display hypophosphatemic rickets with a sharp increase in fibroblast growth factor 23 (FGF23). Disruption of Klotho (the obligatory co-receptor of FGF23) results in hyperphosphatemia with ectopic calcifications formed in blood vessels and kidneys. To determine the role of DMP1 in both a hyperphosphatemic environment and within the ectopic calcifications, we created Dmp1/Klotho compound deficient (Dmp1−/−kl/kl) mice.

Procedures

A combination of TUNEL, immunohistochemistry, TRAP, von Kossa, micro CT, bone histomorphometry, serum biochemistry and Scanning Electron Microscopy techniques were used to analyze the changes in blood vessels, kidney and bone for wild type control, Dmp1−/−, Klotho deficient (kl/kl) and Dmp1−/−kl/kl animals.

Findings

Interestingly, Dmp1−/−kl/kl mice show a dramatic improvement of rickets and an identical serum biochemical phenotype to kl/kl mice (extremely high FGF23, hyperphosphatemia and reduced parathyroid hormone (PTH) levels). Unexpectedly, Dmp1−/−kl/kl mice presented elevated levels of apoptosis in osteocytes, endothelial and vascular smooth muscle cells in small and large blood vessels, and within the kidney as well as dramatic increase in ectopic calcification in all these tissues, as compared to kl/kl.

Conclusion

These findings suggest that DMP1 has an anti-apoptotic role in hyperphosphatemia. Discovering this novel protective role of DMP1 may have clinical relevance in protecting the cells from apoptosis in high-phosphate environments as observed in chronic kidney disease (CKD).

Introduction

Physiologically, phosphate (Pi) is critical not only for the health of mineralized tissues such as bone and teeth, but is also essential for a variety of biological processes, including energy metabolism, cell signaling, nucleic acid synthesis, and membrane function [1]. Pathologically, low blood Pi levels lead to hypophosphatemic rickets [2], [3]; whereas high blood Pi levels, even in the upper-to-normal range, have been linked to increased mortality within populations of both general and chronic kidney disease (CKD) [4]. To maintain Pi homeostasis, parathyroid hormone (PTH) and 1, 25-dihydroxy vitamin D (1,25 (OH)2D3) play an important role via their regulation of phosphate absorption in the intestines and reabsorption in the kidney [5]. Recent findings suggest that FGF23 is a more specific and potent phosphaturic hormone [6], [7], [8]. FGF23, mainly expressed in bone, targets the kidney to remove phosphate with little effect on calcium homeostasis [9], [10]. Fgf23 null mice display increased renal phosphate reabsorption and increased serum 1,25 (OH)2D3 levels, which results in hyperphosphatemia, hypercalcemia, and vascular calcification [10].

DMP1, an extracellular matrix phosphoprotein highly expressed in hard tissues such as the skeleton and teeth, belongs to small integrin ligand N-linked glycoprotein family [11], [12]. Deletion of Dmp1 in mice or mutations in DMP1 in humans causes hypophosphatemic rickets with an elevated circulating level of FGF23, which is responsible for the impaired renal tubular reabsorption of phosphate [13], [14]. The abnormalities observed in Dmp1 null mice include decreased endochondral ossification, defects in bone lengthening and remodeling, increase in the width of the bone (flaring), and an increased metaphysis area [15], [16], [17], [18]. A number of these characteristics are related to the direct role of DMP1 as a regulator of osteocyte maturation [19], whereas other characteristics are secondary to impaired Pi homeostasis [8].

Klotho, a transmembrane protein predominantly expressed in the kidney, was initially identified as an anti-aging gene prior to µµ the discovery of FGF23 during which a loss-of-function study in mice showed a striking aging phenotype encompassing hair loss, infertility and emphysema [20]. Interestingly, Fgf23 null mice unexpectedly exhibited almost an identical aging phenotype as that of Klotho-deficient (kl/kl) mice [10]. On the other hand, kl/kl mice display high serum levels of phosphate, calcium, and vitamin D, which is very similar to that of the Fgf23 null phenotype [21]. Furthermore, mechanistic studies demonstrated that FGF23 requires not only the FGF receptors (FGFRs), but also Klotho, as FGF23 is able to bind to FGFRs with high affinity only in the presence of Klotho. This suggests that Klotho is an obligatory co-receptor of FGF23 [22]. One of the major complications in kl/kl mice is the high frequency of formation of ectopic calcifications in the blood vessels and kidney. This is assumed to be the consequence of either high serum phosphate levels [23], cell death that occurs in CKD patients [24], or the matrix vesicles released from the dead vascular smooth muscle cells [25].

As DMP1, a key regulator of FGF23 [13], [14], is also expressed in blood vessels and kidney tissues [26], [27], we explored the potential (beneficial or harmful) role of DMP1 in soft tissue calcification within Dmp1 −/− kl/kl compound mice lacking both Klotho and Dmp1. This model displayed high phosphate retention and increased FGF23 levels which resemble chronic kidney disease (CKD). We also attempted to test whether elevation of blood Pi levels due to Klotho deficiency would rescue the rickets phenotype in Dmp1−/− mice. Our data support a novel concept that DMP1 plays an important role in blocking ectopic calcification in Klotho deficient mice via its anti-apoptotic function within a high phosphate environment.

Materials and Methods

Ethical Approval

All mice were maintained under guidelines established by Baylor College of Dentistry Institution of Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC). IACUC has specifically given ethical approved for all the procedures in this study.

Animals

Klotho-deficient mice (kl/kl) and Dmp1 lacZ knock-in null mice (Dmp1−/−) were described previously [20], [28]. The kl/kl mouse was originally described as a severe hypomorph strain because extremely low levels of Klotho mRNA were detectable only by RT-PCR [20]. However, Klotho protein was undetectable in any tissues by immunoblot, immunoprecipitation, and immunohisotchemical analyses (data not shown). In addition, kl/kl mice were shown to exhibit the same phenotypes as Klotho−/− mice [29]. Thus, the kl/kl mouse is virtually equivalent to a null strain. All the mice were fed with tap water and autoclaved Purina rodent chow (5010, Rastlon Purina) containing calcium, 0.67% phosphorus and 4.4 international units of vitamin D/g.

Generation of Dmp1/Klotho Compound Deficient Mice

Both Dmp1 and Klotho genes in mice are located on chromosome 5 (qE5 and qG3 respectively). The generation of Dmp1/Klotho compound deficient mice (Dmp1−/−kl/kl) was based on the chance of cross-over between homologous chromosomes. First, we crossed Dmp1 −/− and Klotho-deficient heterozygous mice (kl/+). Their offspring will include male and female heterozygous mice for both Dmp1 and Klotho (Dmp1 +/− kl/+) which were set for litter-mating. In the first three generations, no cross-over occurred. After the third generation, Dmp1 null Klotho hetero animals (Dmp1 −/− kl/+) were born and used for mating with a one-in-four chance for producing compound homozygous mice (Dmp1−/−kl/kl). At the same time compound hetero mice (Dmp1+/− kl/+) were also continued mating to generate wild type (WT), Dmp1−/− and kl/kl animals; A few Dmp1−/−kl/kl mice were also born through this set of mating.

Genotyping

DNA was extracted from the toe of each mouse by standard protocol and subjected to PCR for genotyping. Dmp1+/− and Dmp1−/− were genotyped by PCR as reported previously [28]. For Dmp1, the PCR program consisted of 4 minutes initial denaturation at 94°C, amplification cycle including denaturation at 94°C for 1 minute, annealing at 55°C for 2 minutes, and extension for 3 minutes at 72°C, and final extension was performed at 72°C for 10 minutes. The expected product size for the targeted Dmp1 allele was 280 bp and the wild type allele was 410 bp. The Klotho genotyping protocol and the primers used have been previously mentioned [30]. Briefly for Klotho genotyping, Takara LA Taq and buffer were used and the protocol for PCR included 2 minutes initial denaturation at 94°C, amplification cycle consisting denaturation at 94°C for 30 seconds, annealing at 56°C for 30 seconds, and extension for 1.5 minute at 72°C, which was followed by final extension at 72°C for 10 minutes. The expected product size for WT Klotho was 458 bp and for mutant Klotho was 920 bp.

Serum Biochemistry

Blood was collected directly from the heart by using needle for WT, kl/kl, Dmp1−/− and Dmp1−/− kl/kl mice before they were sacrificed at 6 weeks of age. Serum was isolated and stored at -80°C. Serum phosphorous, calcium, PTH, vitamin D, and FGF23 levels were measured as described previously [8]. Briefly, the serum phosphorous level was measured by the phosphomolibdate-ascorbic acid method. Serum calcium Controlent analysis was performed using the colorimetric calcium kit (Stanbio laboratory). For measuring serum FGF23, we used full length FGF23 ELISA kit (Kainos Laboratories). PTH serum levels were measured using Mouse PTH 1-84 ELISA Kit (Immutopics, Inc. San Clemente, CA), and the level of 1, 25 hydroxyvitamin D (1, 25 (OH)2D3) was measured in serum of all four groups of mice using 1,25 Dihydroxy Vitamin D EIA kit (Immunodiagnostic System, Fountain Hills, AZ).

Histology, Immunohistochemistry and TUNEL Staining

The right tibias of 6 week old mice were collected, fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde in phosphate buffered saline (pH 7.4) for 48 hours, decalcified by microwave EDTA for 16 hours, dehydrated through graded alcohol and then embedded in paraffin. Sections were cut 4.5 µm thick and were mounted on slides and dried. Slides were used for Safranin O and TRAP staining as previously described [11]. Growth plate width was measured for at least 3 mice in each group for Safranin O staining. TRAP positive cells were counted in the area including 300 µm down the growth plate for 3 mice in each group, and the number of the cells was divided by the area for each slide. For immunohistochemistry, mouse anti-alpha rhFGF-23 antibody (Cell Essential) was used on tibias of four study groups including WT, Dmp1−/−, kl/kl, and Dmp1−/−kl/kl animals. To analyze apoptosis in tissues the TUNEL kit (Roche Diagnostics, IN, USA) was used and the number of apoptotic osteocytes in a 100×500 µm2 area was counted in each group. Kidney and aorta samples were fixed and embedded in paraffin without decalcification, and stained for Von Kossa (calcification) and TUNEL (for apoptosis). For undecalcified femurs, samples were embedded in methyl methycrylate, and cut by a Leica 2165 rotary microtome (Ernst Leitz Wetzlar) at a 6 µm thickness. Three samples in each group were stained by Goldner’s masson trichrome staining [8].

Microcomputed Tomography (µCT), Radiography, and Sacnning Electron Microscopy (SEM)

After the fixation, femurs were dissected and radiographs was taken using Faxitron radiographic inspection unit (Model 8050, Field Emission Corporation, Inc), with digital capture image capability.

Femur cortical and trabecular compartments were quantified using an X-ray microCT imaging system (µCT 35, Scanco Medical, Basserdorf, Switzerland). Serial tomographic imaging at an energy level of 55 kV and intensity of 145 µA for the femurs was performed. To analyze the trabecular region, we used 500 cross sectional slides in a constant area under the growth plate in all samples. The area was determined as 100 slides lower than the lowest part of growth plate. In addition, cortical thickness data was obtained at the midshaft of the bone. For this purpose, cortical bones from 100 cross sectional slices above the midshaft of the femur were analyzed. The threshold used for this analysis was 335 for trabecular bone and 283 for cortical bone. Micro CT imaging system was also used to evaluate and compare the calcification level in kidneys of all four groups of mice. Bone volume/total volume of each group was calculated and used for comparison.

To image the osteocyte lacunocanalicular system, SEM of resin casted bone samples was performed. Bone tissues were fixed in 70% ethanol and embedded in MMA (Buehler, Lake Bluff, IL, USA). The surface of the MMA-embedded bone was polished, followed by acid etching with 37% phosphoric acid for 2 to 10 seconds, 5% sodium hypochlorite for 5 minutes, and coating with gold and palladium. Samples were examined by an FEI/Philips XL30 field emission environmental SEM (Phillips, Hillsboro, OR, USA). For Backscattered Electron Microscopy imaging we used the method described previously [17].

Bone Histomorphometry

Using bioquant software, the analysis of osteoid and mineralized bone was performed on the cortical bone area of tibias of the four groups of mice. The identification of mineralized and osteoid area was based on their color in Goldner’s masson trichrome staining; orange to red represents osteoid, and blue represents well mineralized bone. The ratio of mineralized bone or osteoid on total volume of the bone is reported in percent.

Fluorochrome Labeling of the Mineralization Front

Compound fluorescence labeling was performed to visualize the bone mineralization rate in all four groups of WT, Dmp1−/−, kl/kl and Dmp1−/−kl/kl as described previously [31]. Briefly the first intraperitoneal injection was performed using calcein green (5 mg/kg), followed by injection of an alizarin red label (5 mg/kg i.p.; Sigma- Aldrich) 5 days later. Mice were sacrificed after 48 hours. The tibias were collected and fixed in 70% ethanol for 48 hours. Without decalcification the samples were dehydrated through a graded series of ethanol (70% to 100%) and embedded in methyl methacrylate. Then 15-mm sections were cut using a Leitz 1600 saw microtome (Ernst Leitz Wetzlar GmbH, Wetzlar, Germany). The unstained sections were viewed under epifluorescent illumination using a Nikon (Melville, NY, USA) E800 microscope.

Primary Cell Culture for Osteoblasts and Colorimetric TUNEL Assay

Calvarial cells, enriched for cells with an osteoblast phenotype, were isolated from 3 day old Dmp1−/− pups and age-matched control pups using procedures described previously [28]. Briefly, the first-passage cells were plated at density of 2×104 cells/well in 96-well tissue culture dishes (Costar, Corning, NY, USA). Cells were grown to confluence in α-MEM supplemented with 10% FBS. The medium then was changed to α-MEM supplemented with 10% FBS only (normal media), or supplemented with 1 or 5 mM of phosphate added to normal media. After 24 hours of incubation with the new media, cells were fixed in 4% PFA for 7 minutes and washed in PBS. To evaluate and compare apoptosis between the different groups, HT Titer TACS colorimetric assay kit (Trevigen, Gaithersburg, MD, USA) was used. Briefly cells were treated with Cytonin for 30 minutes and after wash with dH2O. After incubation with hydrogen peroxidase, TdT labeling buffer was used for 5 minutes. Then samples were incubated with stop buffer followed by adding Strep HRP solution was to samples for 10 minutes. Samples were washed and incubated by Saphire solution for 30 minutes in dark. Reaction stopped by 0.2 N HCl and absorbance measurement was done at 450 nm. For the cell proliferation assay, Cell Counting Kit-8 was used. Cell proliferation was assessed according to the instruction of the CCK-8 kit (BI Yuntian Co, China). In brief, after incubation with normal media for 24 hours, 10 µL WST-8 was added to each well, and the plates were incubated for an additional 4 hrs at 37°C to convert WST-8 into formazan. The absorbance of each plate was measured at 450 nm (absorbance) with spectrophotometer. The absorbance presents as OD450 nm represents a direct correlation with the cell number in the well.

RT-PCR and Real Time PCR (qPCR)

For real time PCR (qPCR), the total RNA was extracted from mouse tissues in both the kidney and humerus at 6 weeks of age. To evaluate the net expression of FGF23 mRNA in osteocytes, the osteoblastic layer on the surface and bone marrow were both removed. Total RNA was isolated from the kidneys, and cortical bone using TRI-reagent (Molecular Research Center, Cincinnati, OH, USA) as described previously [11]. First-strand cDNA was synthesized from the kidney RNAs using iScript cDNA Synthesis kit (SA Biosciences, Frederick, USA). The 20 µL reverse transcriptase reaction was based on 1 µg total RNA. The iCycler iQ Real-Time PCR Detection System and iQ SYBR Green Supermix (Agilent Technologies, USA) were used for real-time quantitative PCR analysis. The expression was normalized by glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) in the same sample and expressed as 100% of the control (WT). The forward primer sequence used for qPCR for the Dmp1 gene is 5 ′AGTGAGTCATCAGAAGAAAGTCAAGC 3′ and the reverse primer is 5′ CTATACTGGCCTCTGTCGTAGCC 3′.

Western Blot

Total protein from the kidney was extracted by 5ml extraction reagent (4M guanidine hydrochloride and 0.5 M EDTA) followed by centrifugation (20 min, 10000 rpm, 4°C). The supernatant protein solution was then collected and went through a buffer change procedure (to the final concentration at 0.1M NaCl/6M Urea). The urea-protein buffer was loaded to the Q-sephorose column in Fast Protein Liquid Chromatography (FPLC) for acidic proteins (such as DMP1) separation with a gradient buffer elution range at 0.1–0.8M NaCl/6 M urea. Next, Stains-All staining was used to profile DMP1 and other acidic proteins in all the chromatographic fractions. For Western immunoblotting, anti-DMP1-C-857 and osteocalcin [32] was used at 1∶1000 for one hour. Blots were washed three times in PBS containing 0.3% Tween 20, followed by incubation in the alkaline phosphate-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG (Sigma Aldrich; Louis, MO) at a dilution of 1∶5000. Finally, the blots were incubated with the chemiluminescent substrate CDP-Star (Ambion; Austin, TX) for 5 min and exposed to X-ray films [33].

Statistics

The differences were evaluated among groups by one way ANOVA, with Benferoni correction and P<0.05 was considered as statistical significance. The values are reported in mean ± SE. For statistical analysis we used SPSS software.

Results

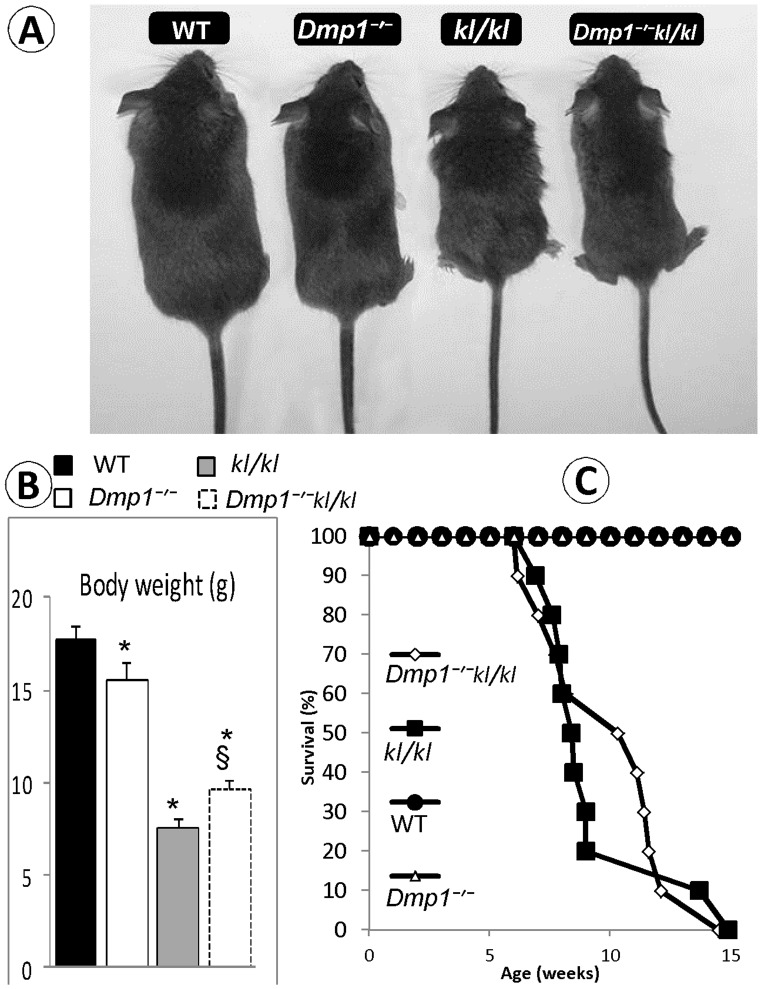

Compound Dmp1 Klotho Deficient Mice Display an Improvement in Growth Retardation

From a gross overview, there was no apparent difference between Dmp1 −/− and wild type (WT) control mice except for a mild reduction in body weight ( Fig. 1A–B ). The body weight of both the kl/kl and compound deficient mice was significantly lower than that of the WT mice. The body weight of the compound deficient mice was slightly improved compared to that of the kl/kl mice, likely due to an increase in skeleton length and ectopic ossification after a switch from hypophosphatemia to hyperphosphatemia. Consistent with previously reported literature [20], [21], [34] kl/kl mice showed a distinct premature aging phenotype, including emphysema, generalized atrophy of the skin, spleen, intestine, skeletal muscle, reproductive organs, and infertility, which was also evident in Dmp1−/−kl/kl animals (data not shown). However, none of these phenotypes were observed in Dmp1 −/− mice.

Figure 1. Macroscopic phenotype of Dmp1/Klotho compound deficient mice (Dmp1−/−kl/kl).

(A) Gross appearance of Wild Type (WT), Dmp1 null (Dmp1−/−), Klotho deficient (kl/kl), and compound deficient (Dmp1−/−kl/kl) mice at 6 weeks of age. (B) Body weights of 6 weeks old mice, showing a decrease in Dmp1−/− (13%), kl/kl (57%) and Dmp1−/−kl/kl (36%) mice compared to the age matched WT (P = 0.02; P<0.001, and P<0.001 respectively; n = 10 in each group). Note that the Dmp1−/−kl/kl body weight was ∼ 30% higher than that of the single kl/kl mice (P = 0.03). (C) Survival for WT, Dmp1−/−, kl/kl, and Dmp1−/−kl/kl mice (n = 10 in each group). Both kl/kl and Dmp1−/−kl/kl mice showed similar low survival rate compared to WT and Dmp1−/− groups. About 40% of Dmp1−/−kl/kl animals survived 3 weeks more than single kl/kl. Neither of the kl/kl nor Dmp1−/−kl/kl groups survived more than 15 weeks. None of WT and Dmp1−/− animals died in 30 weeks of observation period. These mice were of similar genetic backgrounds but not necessarily littermates. *P<0.05 compared to WT; § P<0.05 compared to kl/kl.

Compared to the age matched WT mice, both kl/kl and Dmp1−/−kl/kl mice survived for a shorter length of time than WT mice, and neither kl/kl nor Dmp1−/−kl/kl mice survived longer than 15 weeks ( Fig. 1C ). In contrast, there was no difference between the Dmp1 −/− and WT mice regarding their survival rate ( Fig. 1C ). Interestingly, about 80% of kl/kl mice died before the age of 9 weeks, while 60% of Dmp1−/−kl/kl mice survived longer than 12 weeks, suggesting that ablation of Dmp1 in kl/kl background improves the life span of kl/kl mice ( Fig. 1C ).

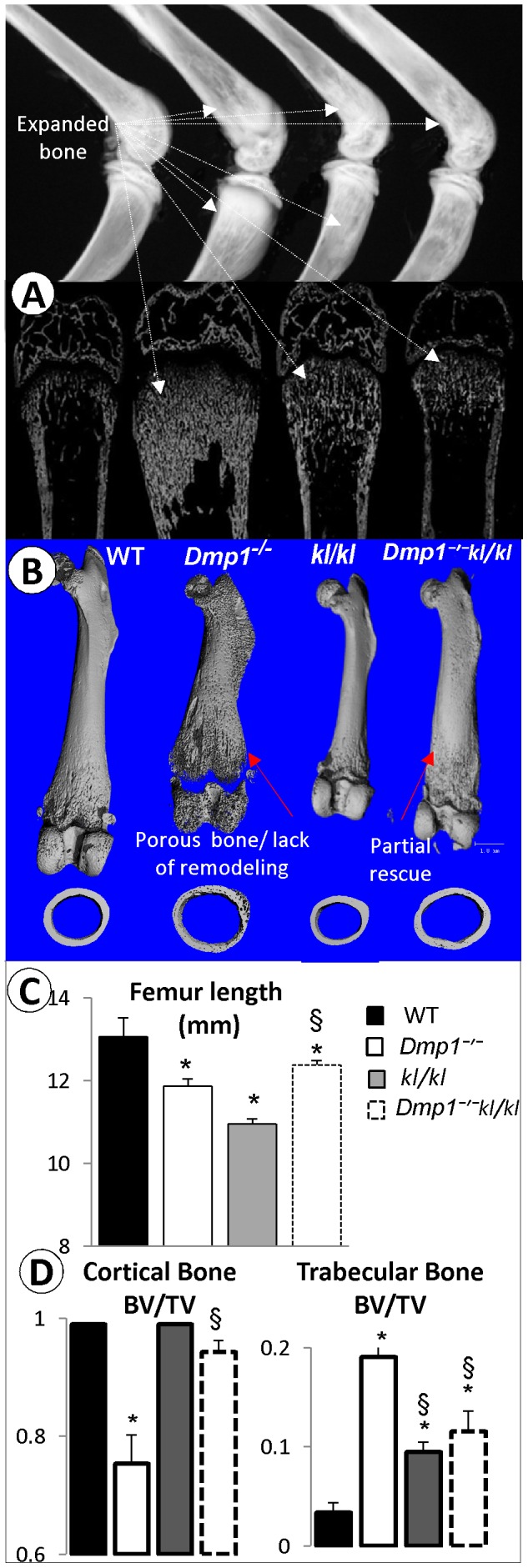

Ablation of Klotho Partially Rescued Rickets Features in Dmp1−/− Mice

The classical characteristics of the rickets phenotype in Dmp1−/− mice, including the expanded growth plate, enlarged diaphysis, and shorter long bone length have been previously reported [17], and it was proposed that both hypophosphatemia and the direct local role of DMP1 are responsible for these pathological changes [2], [8], [19]. Here we show a dramatic improvement of the osteomalacia and rickets phenotypes in Dmp1−/−kl/kl compared to Dmp1−/− mice at 6-weeks of age through the use of radiography, backscattered SEM ( Fig. 2A ) and µCT imaging ( Fig. 2B ). Quantitative data displayed a moderate but significant improvement in the Dmp1−/−kl/kl femur length when compared to the Dmp1−/− femur ( Fig. 2C ). Note that there was over a 25% reduction of bone volume/total volume (BV/TV) (reflecting relative changes in bone volume density) in the Dmp1−/− cortical bone compared to the age-matched control (P<0.01, Fig. 2D, left panel ), which was restored in the Dmp1−/−kl/kl cortical bone with no significant difference compared to the WT control (P = 0.125). Interestingly, there was a significant increase in the BV/TV in Dmp1−/− metaphysis (>80%) and kl/kl metaphysis which was also present in Dmp1−/−kl/kl. Taken together, our x-ray, backscattered SEM, and µCT data showed that there is a significant improvement of BV/TV in the compound long bone. This improvement, plus the restoration of the growth plate and bone length in Dmp1−/−kl/kl mice compared to Dmp1−/− mice was likely due to a switch from hypophosphatemia to hyperphosphatemia, although the probable local role of Klotho ablation in this phenotypic rescue should not be ignored.

Figure 2. The changes of bone volume/mineral content (reflected by BV/TV) and femur length in Dmp1−/−, Klotho deficient (kl/kl) and the compound deficient (Dmp1−/− kl/kl) at age of 6-weeks.

(A) Representative X-ray (upper panel) and backscattered SEM (lower panel) images of the hind limbs obtained from wild type (WT), Dmp1−/−, kl/kl and Dmp1−/− kl/kl mice. (B) Representative µCT images of the above four group femurs at the longitudinal front view (upper panel), and the midshaft cross section view (lower pane). (C) Quantitative µCT data shows moderate changes of femur length in Dmp1−/−, kl/kl and Dmp1−/−kl/kl mice compared to the age-matched WT control (P<0.001, P<0.001, and P = 0.03 respectively; n = 10). Note that the femur length difference between the Dmp1−/−kl/kl mice and kl/kl (P<0.001) or Dmp1−/− (*P<0.05) are significant. (D) The Quantitative µCT data show a sharp reduction of BV/TV in the Dmp1−/− cortical bone (P<0.01), and there is no significant change between WT and kl/kl or the Dmp1−/−kl/kl (left panel). In contrast, there is a significant increase in metaphysis BV/TV in Dmp1−/− (>80%, P<0.01) or in the kl/kl (>50%, P<0.01) or in the Dmp1−/−kl/kl mice (>60%, P<0.01) separately (right panel).

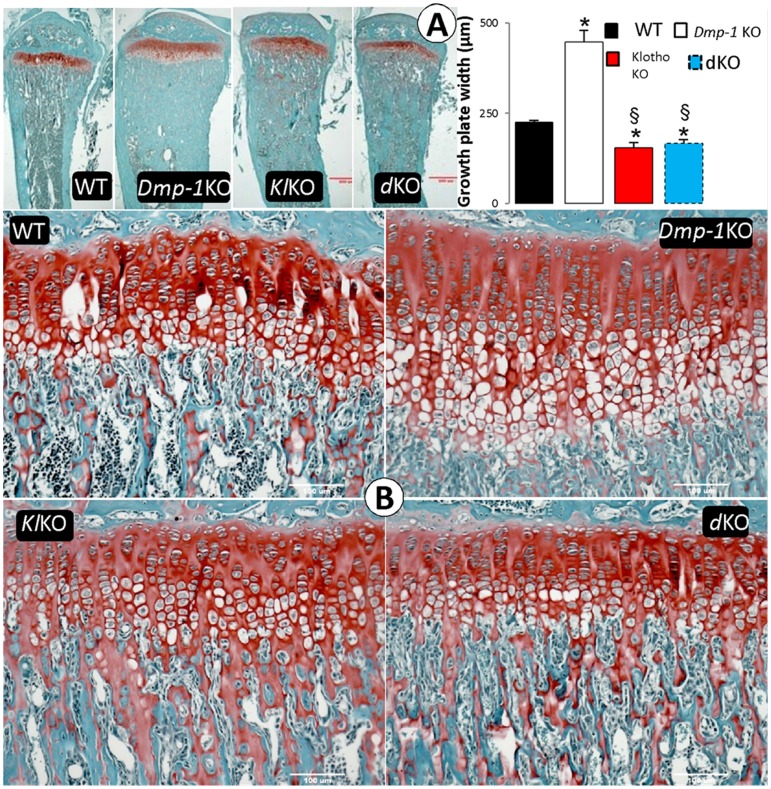

Removing Klotho in Dmp1−/− Background Improves Histological Abnormalities of the Growth Plate and Cortical Bone Mineralization

To determine the effect of Klotho deletion on Dmp1−/− phenotypes at the histological level, we first confirmed the previous reports [15] showing irregular and disorganized chondrocytes and expanded hypertrophic zone in the Dmp1 growth plate, which was rescued in Dmp1−/−kl/kl mice ( Fig. 3A–C ), although the quantitative data displayed a small but significant reduction of the growth plate width in kl/kl and Dmp1−/−kl/kl mice compared to the age matched control ( Fig. 3B ). All these changes (WT, 244±4.8 µm; Dmp1 −/−, 447±31.6 µm; kl/kl, 154.5±14.12 µm; and Dmp1−/−kl/kl, 166±9.6 µm) are statistically significant. It appears that the identical growth plate phenotype in kl/kl and Dmp1−/−kl/kl is a consequence of a change in Pi homeostasis (see Discussion for details).

Figure 3. The effect of deletion of Klotho on histological features of the Dmp1−/− growth plate and metaphysis area.

(A) Growth plates and metaphysis of proximal tibias obtained from WT, Dmp1−/−, kl/kl, and Dmp1−/kl/kl (Safranin O staining x200). Note that there is an expansion of metaphysis in the kl/kl, which is similar to that of the Dmp1−/− and Dmp1−/−kl/kl mice. (B) growth plate width comparison between all four groups of the mice shows increase of phosphate in both kl/kl and Dmp1−/−kl/kl mice resulted in decreased growth plate width compared to WT (P = 0.009 and 0.024 respectively). Values reported in mean ± SE from more than 3 mice in each group at 6 weeks of age. *P<0.05 compared to WT; § P<0.05 compared to Dmp1−/− group.

Next, we examined changes of mineralization in Dmp1−/−kl/kl mice using a fluorescent double label assay (alizarin red complexone and calcein). The diffuse fluorochrome labeling pattern commonly observed in Dmp1−/− mice was restored to a pattern similar to that in both control and single kl/kl mice with discrete lines of calcein and alizarin red labeling, suggesting a normal bone-formation rate ( Fig. 4A ). Bone mineralization quality, as reflected by an increase in osteoid area (Goldner stain), is very poor in the Dmp1−/− long bone, but appears fully rescued in the compound deficient mice as compared to WT and kl/kl mice using both qualitative and quantitative analyses ( Fig. 4B–D ).

Figure 4. Ablation of Klotho rescued bone formation rate and osteomalacia phenotype in the compound deficient (Dmp1−/− kl/kl) mice.

(A) Confocal microscope images of flurochrome labeling of 6 weeks old mice tibias (red: alizarin red, green: calcein). Note that in the Dmp1−/kl/kl mice the bone formation labeling pattern is similar to that of the control and the kl/kl mice. (B) Goldner’s stain showed the massive osteoid (red) areas commonly seen in the Dmp1−/− long bone, which was restored to normal in the Dmp1−/−kl/kl mice. (C, D), Quantitative bone histomorphometric analyses showed that the above changes of the osteoid area (C) and the mineralized area (blue in color) (D) were statistically significant. *P<0.05; **P<0.01 compared to the WT; (n = 3 in each group).

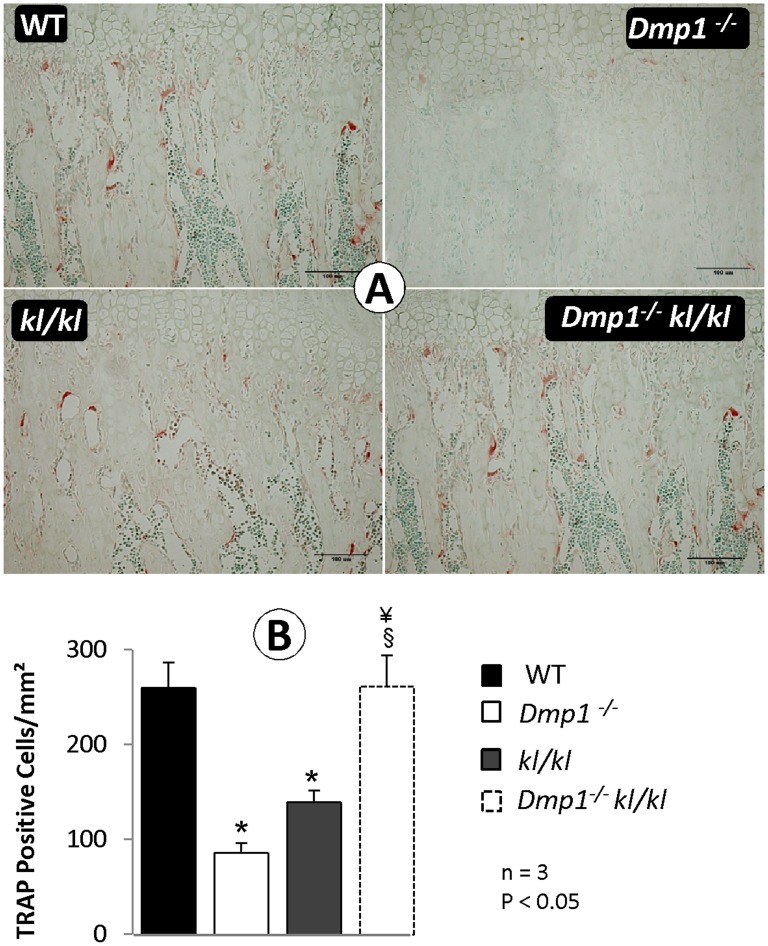

To address the effect of the Klotho deletion on the abnormal bone remodeling commonly observed in Dmp1−/− mice [19], we examined the number of TRAP (a marker for osteoclastic cells) positive cells, which was sharply reduced in both Dmp1−/− and kl/kl but not in the Dmp1−/−kl/kl metaphysis at 6 weeks of age ( Fig. 5A ). The above changes were statistically significant ( Fig. 5B , P<0.05; n = 3). The reduced osteoclast number in kl/kl mice may explain in part why there was an increase in the trabecular bone within the metaphysis area ( Fig. 2A ). Interestingly, in Dmp1−/−kl/kl, the osteoclast number was restored to levels seen in the WT control ( Fig. 5B ). This restoration likely contributed to the improved bone remodeling process in compound deficient mice ( Fig. 2 ).

Figure 5. The compound deficiency of Klotho and Dmp1 increases osteoclast number to the normal level (6 weeks old mice).

(A) TRAP-stained metaphysis of the proximal tibias obtained from WT, Dmp1−/−, kl/kl and compound deficient (Dmp1−/−kl/kl) mice. (B) Quantitative analyses of TRAP positive cells per mm2 in each group. Values reported in mean ± SE from 3 mice in each group. Osteoclast number in Dmp1−/− and kl/kl bones were significantly lower than WT (P<0.001 for both), while in the Dmp1−/−kl/kl group it were restored to the same level as of WT. *P<0.05 compared to WT; § P<0.05 compared to Dmp1−/−; ¥ P<0.05 compared to kl/kl.

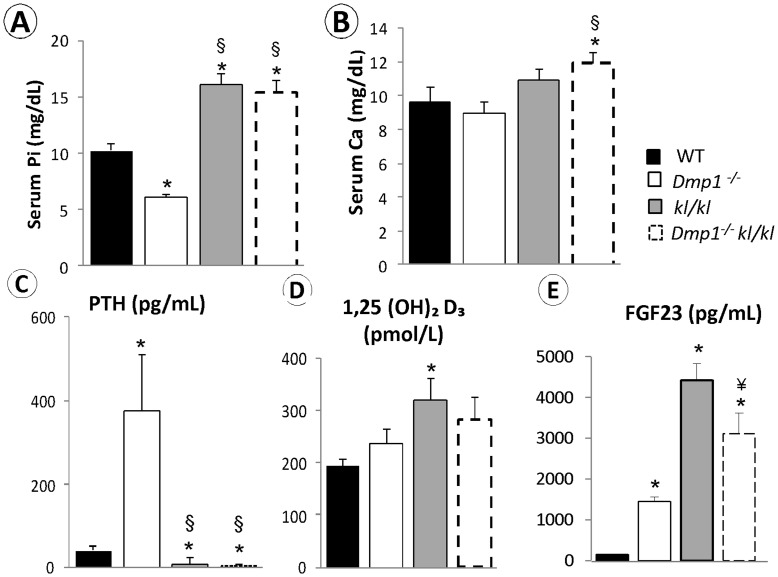

Dmp1−/−kl/kl Mice Displayed a Similar Serum Biochemical Profile as that in a Single kl/kl Mouse

One of the key differences between Dmp1−/− and kl/kl mice is the Pi level: the former shows hypophosphatemia due to an abnormal increase of FGF23 that leads to Pi waste [8] and the latter is associated with hyperphosphatemia, which is due to a failure of FGF23 to remove extra Pi in the absence of Klotho, the key co-receptor [20], [35]. In addition to its phosphaturic activity, FGF23 suppresses the synthesis of 1, 25 dihydroxyvitamin D3 (1,25(OH)2D3). As low 1,25(OH)2D3 stimulates PTH production and secretion, there is secondary hyperparathyroidism in Dmp1−/− mice [8] and PTH suppression in kl/kl mice [35]. To clarify whether bone morphological changes as described above are linked to serum biochemical profile changes in these animals, serum levels of Pi, Ca, FGF23, PTH, and 1,25(OH)2D3 were analyzed. Overall, both kl/kl and Dmp1−/−kl/kl animals shared a similar biochemical profile, including ∼30% increase in Pi, a moderate increase in Ca and 1,25(OH)2D3, and a suppression of PTH ( Fig. 6A–D ). Surprisingly, the FGF23 level in Dmp1−/−kl/kl mice was between the levels of Dmp1−/− and kl/kl mice ( Fig. 6E ).

Figure 6. Changes of serum biochemistry profiles in Dmp1−/−, kl/kl and the Dmp1−/− kl/kl mice.

(A) Serum Phosphate levels were significantly lower in Dmp1−/− mice (P<0.001), while there was a significant increase in kl/kl and the Dmp1−/−kl/kl groups (P<0.001) compared to WT (n = 7 in each group). (B) Serum calcium levels were statistically unchanged in Dmp1−/− and kl/kl mice. However, the calcium level was significantly higher in the Dmp1−/−kl/kl mice than that of the WT (P = 0.04). (C) Serum PTH level was over 10 fold increased in Dmp1−/− but significantly lower in both kl/kl and the Dmp1−/− kl/kl mice compared to WT (P = 0.025, and P = 0.002 respectively). (D) Serum 1,25(OH)2D3 levels were overall higher in all these deficient mice, although only kl/kl mice showed significant difference compared to the WT (P = 0.043). (E) Serum FGF23 levels were high in all three deficient mice with kl/kl the highest compared to the WT control. *P<0.05 compared to WT, § P<0.05 compared to Dmp1−/−, ¥ P<0.05 compared to kl/kl mice.

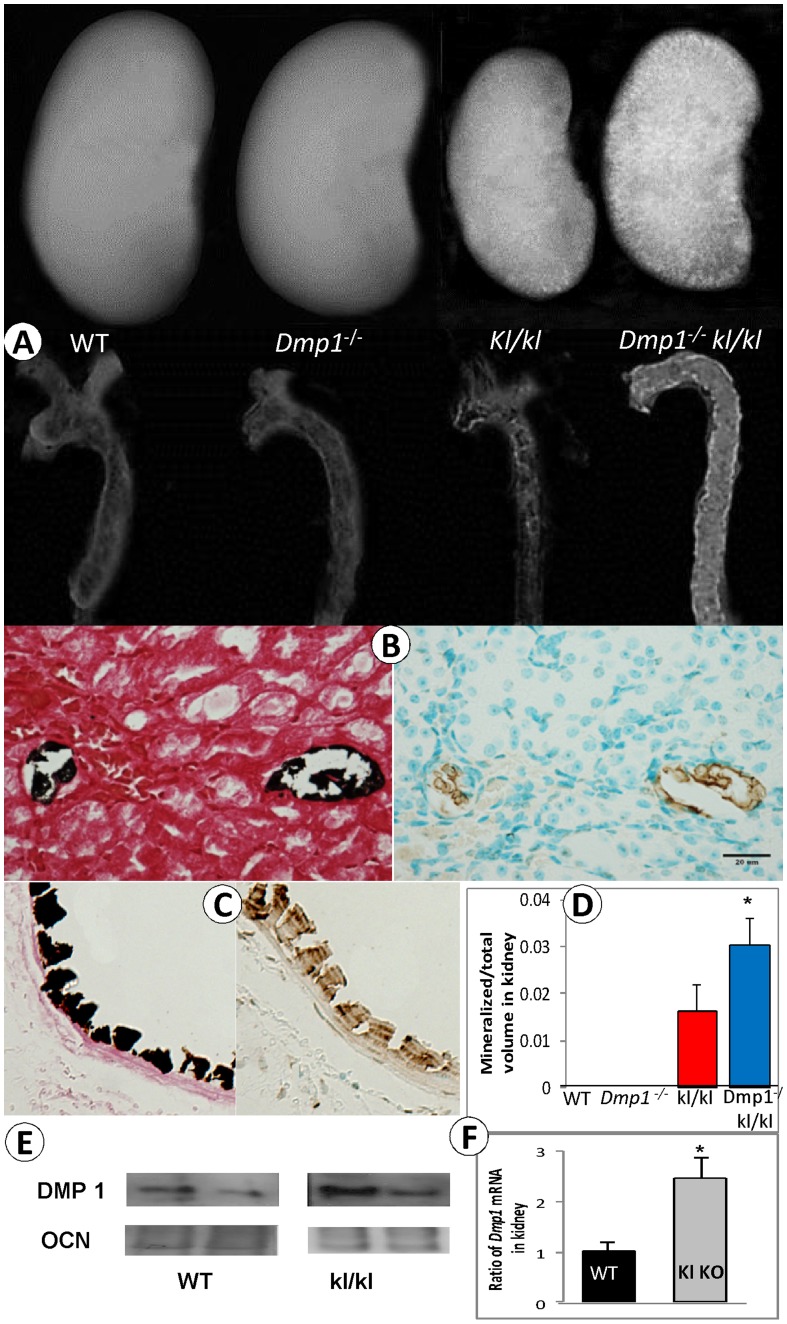

Dmp1−/−kl/kl Mice Display Massive Ectopic Calcifications and Apoptosis in the Aorta and Kidney

Klotho deficient mice (kl/kl) displayed increased serum levels of 1,25(OH)2D3 and widespread vascular and kidney calcifications [36], which was completely reversed when the 25-Hydroxyvitamin D3 1-alpha-hydroxylase (1α-hydroxylase, the enzyme which catalyzes the hydroxylation of calcidiol to calcitriol, the bioactive form of Vitamin D) was deleted [37]. It is also known that Pi is essential for the apoptosis of terminally differentiated hypertrophic chondrocytes in vivo [17], [38], and that high Pi led to apoptosis in osteoblasts [39] and in endothelial cells in vitro [40]. Furthermore, DMP1 was expressed in the blood vessels [26] and the kidneys [41]. To address whether DMP1 plays any role in the ectopic calcification in kl/kl mice we first confirmed DMP1-lacZ expression in the blood vessels and the kidney (Fig. S3–S4). Next, we examined the kidney and the aorta and observed exacerbated calcification by X-ray images ( Fig. 7A ) and by von Kossa staining ( Fig. 7B–C ). The TUNEL assay showed a close correlation between calcification and apoptosis in endothelial and vascular smooth muscle cells, and a very small number of renal tubules. Calcification and apoptosis in the kidney was observed primarily within small blood vessels in both kl/kl and Dmp1−/−kl/kl mice ( Fig. 7B–C ). Quantitative data further confirmed that the ectopic ossification in the Dmp1−/−kl/kl kidney was statistically significant ( Fig. 7D ). In contrast, neither WT nor Dmp1−/− mice displayed ectopic calcification or increased levels of apoptosis (data not shown). The increase in apoptotic cells in the Dmp1−/−kl/kl mice was confirmed by a Caspase 3 assay and H&E stained empty lacunae (Fig. S2). Furthermore, Western Blot and quantitative real time PCR (qPCR) data confirmed that within the kl/kl kidneys the expression of DMP1 is higher than that in the WT kidneys, which might be due to a compensatory mechanism protecting against the toxic effect of high Pi. The above data clearly suggests that DMP1 plays an important anti-apoptotic role in hyperphosphatemia, and that deletion of Dmp1 in kl/kl mice leads to exacerbated calcification in the kidney and the aorta.

Figure 7. Sharply increased ectopic calcification and apoptosis in the compound deficient (Dmp1−/− kl/kl) mice.

(A) Representative X-ray images of kidney and aorta in four groups show moderate ectopic calcifications in the kl/kl kidney and aorta, and massive ectopic calcification in the Dmp1−/−kl/kl kidney and aorta. (B) von-Kossa stain (left panel) and TUNEL assay (right panel) of the Dmp1−/−kl/kl kidney showing a close correlation between the calcified- and apoptotic cells. (C) A similar linkage between the ectopic calcification (von-Kossa stain; right panel) and the apoptosis (TUNEL assay; right panel) was observed in the adjacent Dmp1−/−kl/kl aorta. (D) The quantitative mineral content is sharply increased in both the kl/kl and the Dmp1−/−kl/kl kidney by µCT analysis with significantly higher in the Dmp1−/−kl/kl kidney than that of the single kl/kl kidney (P = 0.041). Values are means ± SEM of 3–5 kidneys. Note that there was no calcification in the WT and the Dmp1−/− mice. (E) Representative DMP1 Western blots with WT at left panel and kl/kl at right panel shows higher density of DMP1 in kl/kl. Osteocalcin (OCN) is the matrix protein which does not show difference between these two groups. (F) Quantitative kidney RT-PCR data showing over two fold-increases of Dmp1 mRANA in kl/kl compared to the WT control. n = 3, *P<0.05.

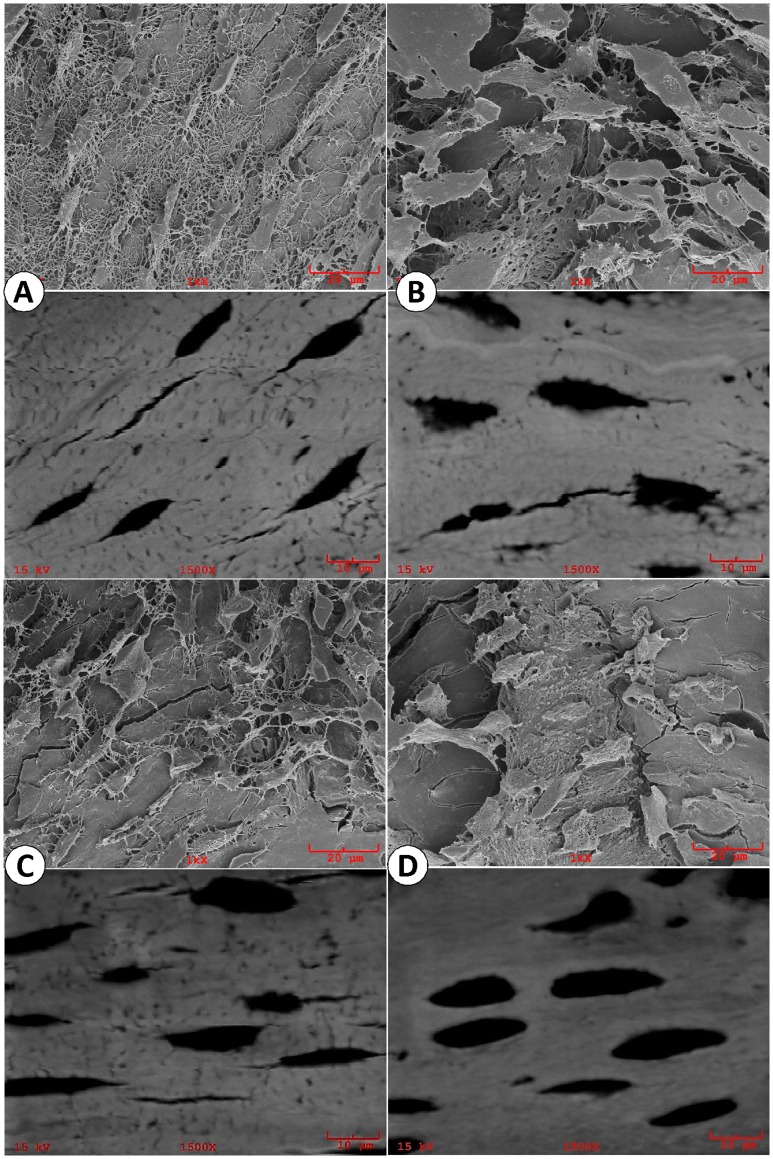

Deletion of Klotho in the Dmp1−/− Mice Greatly Accelerated Osteocyte Dendrite Loss

DMP1 is highly expressed in osteocytes, but Klotho is not. Using an acid-etched resin casting SEM technique, which revealed detail morphologies of WT osteocytes ( Fig. 8A ), we confirmed Dmp1−/− osteocyte abnormalities (including the presence of a rough membrane surface with a sharp reduction of dendrites, Fig. 8B ) [8], and showed minor changes in kl/kl osteocyte dendrite number ( Fig. 8C ). Unexpectedly, there was a much more dramatic change in osteocyte morphology with few osteocyte dendrites remaining ( Fig. 8D ) in Dmp1−/−kl/kl mice compared to the age matched control. The above data indicates that DMP1 is not only necessary for osteocyte maturation and differentiation as previously reported [8], but also plays a protective role in a high phosphate environment in maintaining a normal osteocyte morphology.

Figure 8. Acid-etched resin casting SEM (upper panels) and backscattered SEM (lower panels) images of osteocytes in four animal groups.

(A). Representative SEM images showed well organized WT osteocytes which were generally straight and run perpendicular to the long axis of the osteocyte with numerous dendrites; (B). The Dmp1−/− osteocyte appeared much larger in size, and the distribution of the osteocytes were less organized with a sharp reduction in the dendrite number; (C). The kl/kl osteocytes were less straight and more randomly oriented with moderate reduction in osteocyte dendrites; (D). The Dmp1−/−kl/kl osteocytes, much larger in size, showed absence of dendrites with poor organization in their cell distributions.

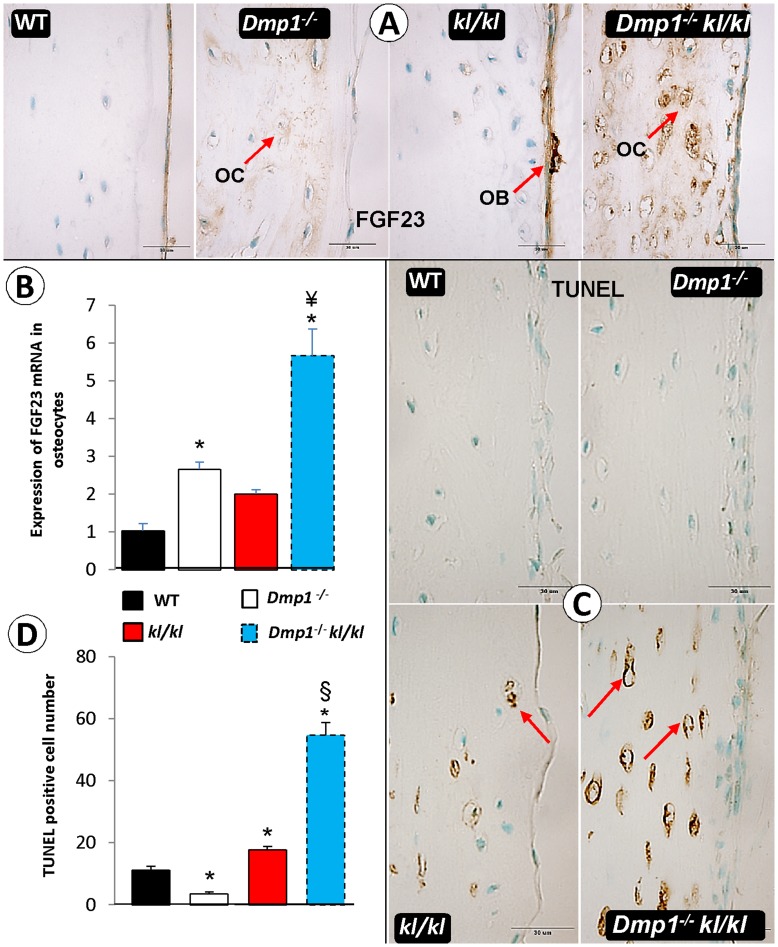

Unique FGF23 Expression Patterns in Dmp1−/−, kl/kl and Dmp1−/−kl/kl Bone Cells

Although FGF23 was sharply increased in Dmp1−/− and kl/kl mice, the causes are different in each mouse model: an increase of FGF23 in the former model is primary to Pi retention while the increase in the latter model is secondary to Pi retention. As the primary FGF23 source is osteoblast cells, we first compared FGF23 expression patterns in the four animal groups using an immunohistochemistry (IHC) assay. FGF23 was mainly expressed in WT osteoblast cells, which was consistent with data previously reported [8], [19]. There was a sharp increase in FGF23 expression in the Dmp1−/− osteocytes (with no FGF23 expression changes in the osteoblasts), a moderate increase in kl/kl osteocytes with a massive increase in kl/kl osteoblasts (which can be assumed as the main source for higher FGF23 serum level in kl/kl compared to all other groups), and a dramatic increase in Dmp1−/−kl/kl osteocytes ( Fig. 9A ). To better define the changes in FGF23 expression in osteocytes, fresh long bones (femurs) were collected, bone marrow cells were flushed out and the periosteum was removed. Real-time RT-PCR (qPCR) data confirmed a significant increase in Fgf23 mRNA in kl/kl, Dmp1−/− and Dmp1−/−kl/kl osteocytes with Dmp1−/−kl/kl having the highest (∼5-fold) increase ( Fig. 9B ). To address whether there was a potential linkage between the changes of FGF23 levels and apoptosis in these bones, we further examined apoptotic bone cells using the TUNEL assay. There were few detectable TUNEL positive bone cells in WT and Dmp1−/− femurs. In contrast, there was a moderate amount of apoptotic bone cells in kl/kl femurs and many apoptotic osteocytes in the Dmp1−/−kl/kl femurs ( Fig. 9C ). Performing quantitative analysis on osteocyte cell death showed that the apoptotic cell number in kl/kl mice was significantly higher than that of WT mice ( Fig. 9D ; P = 0.027), and the number of Dmp1−/− apoptotic cells was lower although with no significance (P = 0.056). The Dmp1−/−kl/kl apoptotic cells were the highest amongst all four groups (P<0.001, n = 3). Taken together, the above data showed 1) different FGF23 expression patterns in these three groups with a high level in kl/kl osteoblasts; 2) an anti-apoptotic role of DMP1 in a high phosphate environment; and 3) a possible correlation between a sharp up-regulation of FGF23 expression and an increase of apoptotic cell number in Dmp1−/−kl/kl osteocytes.

Figure 9. The effect of Ablation of Dmp1 in Klotho deficient background increases apoptosis and FGF23 expression in osteocytes.

(A) FGF23 immunostaining shows in Dmp1 −/− and in Dmp1−/−kl/kl animals the expression of FGF23 is detectable in both osteocytes (OC) and osteoblasts (OB), while in kl/kl mice it is mainly expressed in osteoblasts with much higher density compared to WT. (B) Quantitative real time PCR on bone after removal of osteoblast layer in Dmp1−/− shows increased FGF23 expression compared to WT (P = 0.016), but this expression was significantly higher in Dmp1−/−kl/kl osteocyte (P<0.001). (C) TUNEL staining on four groups of mice shows dramatic increase in double deficient mice (Dmp1−/−kl/kl) even compared to single kl/kl in osteocytes. (D) Counting apoptotic cells in 500 µm2 of slides shows Dmp1−/− has significantly lower rate of apoptosis compared to WT (P = 0.027), and this rate is higher in both kl/kl and the Dmp1−/−kl/kl mice (P = 0.05 and P<0.001 respectively). Ablation of Dmp1 in Dmp1−/−kl/kl mice increased apoptosis rate in osteocytes even compared to single kl/kl (P<0.001). (OC, osteocyte; OB, osteoblast).

Discussion

Although DMP1 is expressed in both hard and soft tissues, the phenotype in human DMP1 mutations or Dmp1 deficient mice was mainly identified in the skeleton and the teeth, likely caused by hypophosphatemia, and increased FGF23 levels [3], [8], [27], [28]. On the other hand, defects or mutations in Fgf23 or Klotho resulted in hyperphosphatemia, premature aging, and the formation of ectopic calcifications [20], [42]. To investigate the potential role of DMP1 in the Klotho deficient mice we generated and characterized compound deficient (Dmp1−/−kl/kl) mice using a combination of in vitro and in vivo approaches. Our studies revealed a novel anti-apoptotic function of DMP1 in a high phosphate environment (caused by Klotho ablation) (also see Figure S2), followed by severe ectopic calcifications within the Dmp1−/−kl/kl kidney and aorta. There is also a unique distribution of FGF23 within kl/kl, Dmp1 −/− and Dmp1−/−kl/kl bones. These findings may stimulate future studies of the roles of DMP1 in prevention of vascular calcification in hyperphosphatemic environments such as those within chronic kidney disease (CKD).

Almost all patients with cardiovascular disease have some degree of ectopic calcification in their blood vessels and kidneys [43], although the most-extensive vascular calcification occurs in CKD patients that is closely linked to hyperphosphatemia [44]. Recent studies suggest that two key factors are responsible for vascular calcification in hyperphosphatemia: 1) up regulation of osteogenic factors such as Osterix, Cbfa1, and several bone-associated proteins (Osteopontin, Bone Sialoprotein, Alkaline Phosphatase, and Type I Collagen) [44], [45] and 2) phosphate-induced apoptosis [24], [25]. Furthermore, the recombinant Klotho protein itself is able to attenuate cellular apoptosis and senescence through mitogen-activated kinase and extracellular signal-regulated kinase pathways [46]. Here, for the first time, we showed that DMP1 plays an anti-apoptotic function in a high phosphate environment, which makes it a critical factor for the attenuation of calcification in the aorta and the kidneys in a hyperphosphatemic environment such as within CKD disease ( Fig. 7 ). This anti-apoptotic role was also observed in bone ( Fig. 9C–D ), as well as in osteoblast cell culture (Fig. S1) when the phosphate level increased. It appears that this protection is important for maintaining osteocyte morphology in a high phosphate environment, as there was only a moderate loss of osteocyte dendrites in the kl/kl mice in contrast to dramatic loss of osteocyte dendrites in Dmp1−/−kl/kl mice ( Fig. 8 ).

It is well documented that FGF23 is mainly produced and secreted from bone cells. However, it was debatable whether FGF23 is secreted from osteocytes or osteoblasts [6], [8], [19], [47], [48]. Here, our immunohistochemical data showed that FGF23 was mainly expressed in the osteoblast cell layer with a low level of expression in the osteocytes in both WT and kl/kl mice, whereas FGF23 was mainly expressed in the osteocyte in both Dmp1 −/− and Dmp1−/−kl/kl mice ( Fig. 9A ). The qPCR data was in agreement with the above immunohistochemical data ( Fig. 9B ). Although we do not know the mechanistic details for such a difference in the sites of FGF23 expression among these animal models, the high level of FGF23 in the Dmp1−/− osteocytes was likely the consequence of the defect in the osteocyte maturation process [8], [19], [48]. In these studies, we showed that DMP1 is highly expressed in osteocytes with an extremely low level in the WT osteoblasts, and that Dmp1−/− mice displayed pathological changes in the osteocyte, including morphological changes in lacunocanalicular system, defects in matrix surrounding the osteocytes, up-regulation of many genes expressed in normal osteoblasts (such as type I collagen or BSP) or ectopically produced (such as FGF23 and osteocalcin). It appears that there was a close correlation between the high expression levels of FGF23 and the accelerated levels of apoptosis within the Dmp1−/−kl/kl osteocytes ( Fig. 9C–D and Fig. S2). Our future study seeks to understand why and how apoptotic osteocytes release more FGF23 in this animal model.

Dmp1 −/− mice, like hyp mice (a well-studied hypophosphatemic rickets animal model) [49], display abnormally high FGF23, low serum Pi, rickets and osteomalacia, which is a consequence of the defects in the osteocytes [2], [8], [19]. The administration of a high phosphate diet [8] or performing injections of FGF23 neutralizing antibody [19] can fully rescue the rickets phenotype but is only partially restored in osteomalacia. However, Dmp1−/−kl/kl mice display no sign of rickets or osteomalacia ( Fig. 4 ), as these mice were never exposed to hypophosphatemia. Regarding the similarity of FGF23 and 1,25(OH)2D3 in both Dmp1 −/− and Dmp1−/−kl/kl mice, this study does not support the direct roles of these two factors in Dmp1 −/− bones ( Fig. 3 ). Furthermore, the bone volume/total volume and osteoclast number/bone remodeling were greatly improved in the Dmp1−/−kl/kl mice, supporting the early beneficial role of Pi administration in restoring the local bone phenotype ( Figs. 2 and 5 ).

Interestingly, the serum Ca level in Dmp1−/− mice is relatively “normal” compared to the age matched WT control ( Fig. 4B ), although the Dmp1 −/− osteoclast cell number is reduced more than 50% ( Fig. 5 ). This “normal Ca level” in Dmp1 −/− mice is likely caused by an increase of renal Ca reabsorption, as the PTH level was up-regulated almost 10-fold ( Fig. 4C ).

Both Fgf23−/− and Klotho deficient mice share many similarities such as hyperphosphatemia, high 1,25(OH)2D3 levels, ectopic ossification in the soft tissues, and several lines of compelling evidence suggest that FGF23’s function in the regulation of systemic phosphate and vitamin D homeostasis is klotho-dependent [3], [21], [50]. However, there is a notable difference between these two types of mice: an increase in bone volume in the Klotho deficient tibial metaphysis ( Fig. 2 ) [51], but a reduction of bone volume in Fgf23−/− tibial metaphysis [11]. Liu et al. showed evidence of increased Wnt signaling in Klotho deficient mice, suggest a unique antagonistic role against Wnt by Klotho [52]. Furthermore, the apoptotic phenomenon has not been reported in Fgf23 −/− mice.

In conclusion, this study presented an increase of apoptosis in the Dmp1/klotho compound deficient mice, which is closely linked to substantial increase of ectopic ossification in the aorta and in the kidney. Discovering this novel anti-apoptotic role of DMP1 in a hyperphosphatemic environment may have important clinical relevance in uncovering a method to protect cells from apoptosis in high phosphate environments such as that which occurs in CKD patients. Our studies also showed improvement of the rickets/osteomalacia phenotype, and dramatically enhanced bone modeling in the compound deficient mice, suggesting that the low phosphate level plays a key pathological role in Dmp1−/− mice.

Supporting Information

Cell proliferation and apoptosis in osteoblasts. As a result of protective role of DMP1 in hyperphosphatemia, increase in phosphate level increases the apoptosis level significantly in Dmp1−/− cells while it has no significant effect on WT cells in vitro; Primary calvarial cells were isolated from control (WT) and Dmp1 −/− mice at age of 3-day after birth. Cells were grown in α-MEM supplemented with 10% FBS only (normal media), or added 1 or 5 mM of phosphate to the normal media. After 24 hours of incubation cells were fixed and analyzed for apoptosis or cell proliferation assay respectively. (A) TUNEL assay showed Dmp1−/− apoptotic cells in normal media are significantly lower than WT. Also increasing the phosphate level significantly increases the apoptosis level in Dmp1−/− cells compared to normal media. While increased phosphate level does not have any significant effect on WT cells apoptosis rate. (*P<0.05 compared to WT in normal media, §P<0.05 compared to Dmp1−/− in normal media). (B) Cell proliferation assay does not show any significant difference between Dmp1−/− cell proliferative activity by increasing phosphate level, confirming the protective role of DMP1 for osteoblasts in hyperphosphatemic environment. Increased phosphate level is toxic to the cells if they do not express DMP1, and increases apoptosis.

(TIF)

An increase of cell death in the compound deficient bone. (A) There is a dramatic increase of apoptotic cells in double deficient mice (Dmp1 −/− kl/kl) compared to the single kl/kl osteocytes and osteoblasts in the cortical bone of femur (6 weeks old). (B) Hematoxylin and Eosin stain of femur cortical bone of 6 weeks old animals shows numerous empty lacunae, which represent dead osteocytes, in Dmp1−/−kl/kl. (C) Quantitative data suggest that the high empty lacunae rate in Dmp1−/−kl/kl group is significant compared to other groups (P<0.001, n = 4). Both pieces of evidence support a protective role of DMP1 in hyperphosphatemic environment.

(TIF)

The Dmp1 lacZ knock-in transgene is expressed in blood vessels. Whole mount X-gal stain of a heterozygous Dmp1-lacZ knock-in uterus overnight shows blue stain blood vessel (6-mo old, left panel). A frozen section of this whole mount X-gal stained tissue was count stained with Eosin, displaying the blue stained cells in the blood vessel wall in small arteries, small veins and arterioles.

(TIF)

The Dmp1 lacZ knock-in transgene is expressed in Kidney. Whole mount X-gal stain of a heterozygous Dmp1-lacZ knock-in kidney overnight shows blue stain blood vessel (6-mo old). A frozen section of this whole mount X-gal stained kidney tissue was count stained with Eosin, displaying the blue stained cells in the kidney renal tubules (insert).

(TIF)

Funding Statement

This work was partly supported by NIH Grant DE018486 (to JQF) and DE005092 (to CQ). The funder had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1. Foster BL, Tompkins KA, Rutherford RB, Zhang H, Chu EY, et al. (2008) Phosphate: known and potential roles during development and regeneration of teeth and supporting structures. Birth Defects Res C Embryo Today 84: 281–314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Qin C, D’Souza R, Feng JQ (2007) Dentin matrix protein 1 (DMP1): new and important roles for biomineralization and phosphate homeostasis. J Dent Res 86: 1134–1141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Martin A, Liu S, David V, Li H, Karydis A, et al. (2011) Bone proteins PHEX and DMP1 regulate fibroblastic growth factor Fgf23 expression in osteocytes through a common pathway involving FGF receptor (FGFR) signaling. FASEB J 25: 2551–2562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kestenbaum B (2007) Phosphate metabolism in the setting of chronic kidney disease: significance and recommendations for treatment. Semin Dial 20: 286–294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Schiavi SC, Kumar R (2004) The phosphatonin pathway: new insights in phosphate homeostasis. Kidney Int 65: 1–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Liu S, Zhou J, Tang W, Jiang X, Rowe DW, et al. (2006) Pathogenic role of Fgf23 in Hyp mice. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 291: E38–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Sitara D, Razzaque MS, Hesse M, Yoganathan S, Taguchi T, et al. (2004) Homozygous ablation of fibroblast growth factor-23 results in hyperphosphatemia and impaired skeletogenesis, and reverses hypophosphatemia in Phex-deficient mice. Matrix Biol 23: 421–432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Feng JQ, Ward LM, Liu S, Lu Y, Xie Y, et al. (2006) Loss of DMP1 causes rickets and osteomalacia and identifies a role for osteocytes in mineral metabolism. Nat Genet 38: 1310–1315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Shimada T, Mizutani S, Muto T, Yoneya T, Hino R, et al. (2001) Cloning and characterization of FGF23 as a causative factor of tumor-induced osteomalacia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 98: 6500–6505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Shimada T, Kakitani M, Yamazaki Y, Hasegawa H, Takeuchi Y, et al. (2004) Targeted ablation of Fgf23 demonstrates an essential physiological role of FGF23 in phosphate and vitamin D metabolism. J Clin Invest 113: 561–568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Liu S, Zhou J, Tang W, Menard R, Feng JQ, et al. (2008) Pathogenic role of Fgf23 in Dmp1-null mice. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 295: E254–261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lorenz-Depiereux B, Bastepe M, Benet-Pages A, Amyere M, Wagenstaller J, et al. (2006) DMP1 mutations in autosomal recessive hypophosphatemia implicate a bone matrix protein in the regulation of phosphate homeostasis. Nat Genet 38: 1248–1250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Bai XY, Miao D, Goltzman D, Karaplis AC (2003) The autosomal dominant hypophosphatemic rickets R176Q mutation in fibroblast growth factor 23 resists proteolytic cleavage and enhances in vivo biological potency. Journal of Biological Chemistry 278: 9843–9849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. White KE, Carn G, Lorenz-Depiereux B, Benet-Pages A, Strom TM, et al. (2001) Autosomal-dominant hypophosphatemic rickets (ADHR) mutations stabilize FGF-23. Kidney International 60: 2079–2086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ye L, Mishina Y, Chen D, Huang H, Dallas SL, et al. (2005) Dmp1-deficient mice display severe defects in cartilage formation responsible for a chondrodysplasia-like phenotype. Journal of Biological Chemistry 280: 6197–6203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ye L, Zhang S, Ke H, Bonewald LF, Feng JQ (2008) Periodontal breakdown in the Dmp1 null mouse model of hypophosphatemic rickets. J Dent Res 87: 624–629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ye L, Mishina Y, Chen D, Huang H, Dallas SL, et al. (2005) Dmp1-deficient mice display severe defects in cartilage formation responsible for a chondrodysplasia-like phenotype. J Biol Chem 280: 6197–6203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ye L, MacDougall M, Zhang S, Xie Y, Zhang J, et al. (2004) Deletion of dentin matrix protein-1 leads to a partial failure of maturation of predentin into dentin, hypomineralization, and expanded cavities of pulp and root canal during postnatal tooth development. J Biol Chem 279: 19141–19148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Zhang R, Lu Y, Ye L, Yuan B, Yu S, et al. (2011) Unique roles of phosphorus in endochondral bone formation and osteocyte maturation. J Bone Miner Res 26: 1047–1056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kuro-o M, Matsumura Y, Aizawa H, Kawaguchi H, Suga T, et al. (1997) Mutation of the mouse klotho gene leads to a syndrome resembling ageing. Nature 390: 45–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Nakatani T, Sarraj B, Ohnishi M, Densmore MJ, Taguchi T, et al. (2009) In vivo genetic evidence for klotho-dependent, fibroblast growth factor 23 (Fgf23) -mediated regulation of systemic phosphate homeostasis. FASEB J 23: 433–441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kurosu H, Ogawa Y, Miyoshi M, Yamamoto M, Nandi A, et al. (2006) Regulation of fibroblast growth factor-23 signaling by klotho. J Biol Chem 281: 6120–6123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hu MC, Shi M, Zhang J, Quinones H, Griffith C, et al. (2011) Klotho deficiency causes vascular calcification in chronic kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol 22: 124–136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Shroff RC, McNair R, Skepper JN, Figg N, Schurgers LJ, et al. (2010) Chronic mineral dysregulation promotes vascular smooth muscle cell adaptation and extracellular matrix calcification. J Am Soc Nephrol 21: 103–112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Schlieper G, Aretz A, Verberckmoes SC, Kruger T, Behets GJ, et al. (2010) Ultrastructural analysis of vascular calcifications in uremia. J Am Soc Nephrol 21: 689–696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Lv K, Huang H, Lu Y, Qin C, Li Z, et al. (2010) Circling behavior developed in Dmp1 null mice is due to bone defects in the vestibular apparatus. Int J Biol Sci 6: 537–545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Terasawa M, Shimokawa R, Terashima T, Ohya K, Takagi Y, et al. (2004) Expression of dentin matrix protein 1 (DMP1) in nonmineralized tissues. J Bone Miner Metab 22: 430–438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Feng JQ, Huang H, Lu Y, Ye L, Xie Y, et al. (2003) The Dentin matrix protein 1 (Dmp1) is specifically expressed in mineralized, but not soft, tissues during development. J Dent Res 82: 776–780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Tsujikawa H, Kurotaki Y, Fujimori T, Fukuda K, Nabeshima Y (2003) Klotho, a gene related to a syndrome resembling human premature aging, functions in a negative regulatory circuit of vitamin D endocrine system. Mol Endocrinol 17: 2393–2403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Brownstein CA, Zhang J, Stillman A, Ellis B, Troiano N, et al. (2010) Increased bone volume and correction of HYP mouse hypophosphatemia in the Klotho/HYP mouse. Endocrinology 151: 492–501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Lu Y, Ye L, Yu S, Zhang S, Xie Y, et al. (2007) Rescue of odontogenesis in Dmp1-deficient mice by targeted re-expression of DMP1 reveals roles for DMP1 in early odontogenesis and dentin apposition in vivo. Dev Biol 303: 191–201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Maciejewska I, Cowan C, Svoboda K, Butler WT, D’Souza R, et al. (2009) The NH2-terminal and COOH-terminal fragments of dentin matrix protein 1 (DMP1) localize differently in the compartments of dentin and growth plate of bone. J Histochem Cytochem 57: 155–166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Prasad M, Zhu Q, Sun Y, Wang X, Kulkarni A, et al. (2011) Expression of dentin sialophosphoprotein in non-mineralized tissues. J Histochem Cytochem 59: 1009–1021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Ohnishi M, Razzaque MS (2010) Dietary and genetic evidence for phosphate toxicity accelerating mammalian aging. FASEB J 24: 3562–3571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Kuro-o M (2010) A potential link between phosphate and aging–lessons from Klotho-deficient mice. Mech Ageing Dev 131: 270–275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Memon F, El-Abbadi M, Nakatani T, Taguchi T, Lanske B, et al. (2008) Does Fgf23-klotho activity influence vascular and soft tissue calcification through regulating mineral ion metabolism? Kidney Int 74: 566–570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Ohnishi M, Nakatani T, Lanske B, Razzaque MS (2009) Reversal of mineral ion homeostasis and soft-tissue calcification of klotho knockout mice by deletion of vitamin D 1alpha-hydroxylase. Kidney Int 75: 1166–1172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Sabbagh Y, Carpenter TO, Demay MB (2005) Hypophosphatemia leads to rickets by impairing caspase-mediated apoptosis of hypertrophic chondrocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 102: 9637–9642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Meleti Z, Shapiro IM, Adams CS (2000) Inorganic phosphate induces apoptosis of osteoblast-like cells in culture. Bone 27: 359–366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Di Marco GS, Hausberg M, Hillebrand U, Rustemeyer P, Wittkowski W, et al. (2008) Increased inorganic phosphate induces human endothelial cell apoptosis in vitro. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 294: F1381–1387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Ogbureke KU, Fisher LW (2005) Renal expression of SIBLING proteins and their partner matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs). Kidney Int 68: 155–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Takeda E, Yamamoto H, Nashiki K, Sato T, Arai H, et al. (2004) Inorganic phosphate homeostasis and the role of dietary phosphorus. J Cell Mol Med 8: 191–200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. O’Rourke RA, Brundage BH, Froelicher VF, Greenland P, Grundy SM, et al. (2000) American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Expert Consensus Document on electron-beam computed tomography for the diagnosis and prognosis of coronary artery disease. J Am Coll Cardiol 36: 326–340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Moe SM, Chen NX (2004) Pathophysiology of vascular calcification in chronic kidney disease. Circ Res 95: 560–567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Mathew S, Tustison KS, Sugatani T, Chaudhary LR, Rifas L, et al. (2008) The mechanism of phosphorus as a cardiovascular risk factor in CKD. J Am Soc Nephrol 19: 1092–1105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Maekawa Y, Ohishi M, Ikushima M, Yamamoto K, Yasuda O, et al. (2011) Klotho protein diminishes endothelial apoptosis and senescence via a mitogen-activated kinase pathway. Geriatr Gerontol Int. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Sitara D, Razzaque MS, St-Arnaud R, Huang W, Taguchi T, et al. (2006) Genetic ablation of vitamin D activation pathway reverses biochemical and skeletal anomalies in Fgf-23-null animals. Am J Pathol 169: 2161–2170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Lu Y, Yuan B, Qin C, Cao Z, Xie Y, et al. (2011) The biological function of DMP-1 in osteocyte maturation is mediated by its 57-kDa C-terminal fragment. J Bone Miner Res 26: 331–340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Eicher EM, Southard JL, Scriver CR, Glorieux FH (1976) Hypophosphatemia: mouse model for human familial hypophosphatemic (vitamin D-resistant) rickets. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 73: 4667–4671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Martin A, David V, Quarles LD (2012) Regulation and function of the FGF23/klotho endocrine pathways. Physiol Rev 92: 131–155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Yamashita T, Nabeshima Y, Noda M (2000) High-resolution micro-computed tomography analyses of the abnormal trabecular bone structures in klotho gene mutant mice. J Endocrinol 164: 239–245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Liu H, Fergusson MM, Castilho RM, Liu J, Cao L, et al. (2007) Augmented Wnt signaling in a mammalian model of accelerated aging. Science 317: 803–806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Cell proliferation and apoptosis in osteoblasts. As a result of protective role of DMP1 in hyperphosphatemia, increase in phosphate level increases the apoptosis level significantly in Dmp1−/− cells while it has no significant effect on WT cells in vitro; Primary calvarial cells were isolated from control (WT) and Dmp1 −/− mice at age of 3-day after birth. Cells were grown in α-MEM supplemented with 10% FBS only (normal media), or added 1 or 5 mM of phosphate to the normal media. After 24 hours of incubation cells were fixed and analyzed for apoptosis or cell proliferation assay respectively. (A) TUNEL assay showed Dmp1−/− apoptotic cells in normal media are significantly lower than WT. Also increasing the phosphate level significantly increases the apoptosis level in Dmp1−/− cells compared to normal media. While increased phosphate level does not have any significant effect on WT cells apoptosis rate. (*P<0.05 compared to WT in normal media, §P<0.05 compared to Dmp1−/− in normal media). (B) Cell proliferation assay does not show any significant difference between Dmp1−/− cell proliferative activity by increasing phosphate level, confirming the protective role of DMP1 for osteoblasts in hyperphosphatemic environment. Increased phosphate level is toxic to the cells if they do not express DMP1, and increases apoptosis.

(TIF)

An increase of cell death in the compound deficient bone. (A) There is a dramatic increase of apoptotic cells in double deficient mice (Dmp1 −/− kl/kl) compared to the single kl/kl osteocytes and osteoblasts in the cortical bone of femur (6 weeks old). (B) Hematoxylin and Eosin stain of femur cortical bone of 6 weeks old animals shows numerous empty lacunae, which represent dead osteocytes, in Dmp1−/−kl/kl. (C) Quantitative data suggest that the high empty lacunae rate in Dmp1−/−kl/kl group is significant compared to other groups (P<0.001, n = 4). Both pieces of evidence support a protective role of DMP1 in hyperphosphatemic environment.

(TIF)

The Dmp1 lacZ knock-in transgene is expressed in blood vessels. Whole mount X-gal stain of a heterozygous Dmp1-lacZ knock-in uterus overnight shows blue stain blood vessel (6-mo old, left panel). A frozen section of this whole mount X-gal stained tissue was count stained with Eosin, displaying the blue stained cells in the blood vessel wall in small arteries, small veins and arterioles.

(TIF)

The Dmp1 lacZ knock-in transgene is expressed in Kidney. Whole mount X-gal stain of a heterozygous Dmp1-lacZ knock-in kidney overnight shows blue stain blood vessel (6-mo old). A frozen section of this whole mount X-gal stained kidney tissue was count stained with Eosin, displaying the blue stained cells in the kidney renal tubules (insert).

(TIF)