Abstract

Objective

Bladder pain syndrome or interstitial cystitis (BPS/IC) is associated with a high rate of mental health disorders, including depression. Little is known about suicide risk in patients with BPS/IC or the characteristics of patients with BPS/IC who endorse suicidal ideation (SI). We compared respondents who endorsed SI with respondents who denied SI within a national probability sample of women with BPS/IC symptoms.

Methods

Data were collected as part of the RAND Interstitial Cystitis Epidemiology (RICE) Study, which screened 146,246 U.S. households to identify adult women who met BPS/IC symptom criteria. In addition to estimating SI prevalence, women with and without recent SI were compared based on demographics, depression symptoms, BPS/IC symptoms, functioning, and treatment utilization.

Results

Of 1,019 women with BPS/IC symptoms asked about SI, 11.0% (95% CI: 8.73–13.25) reported SI in the past 2 weeks. Those with SI were more likely to be younger, unemployed, unmarried, uninsured, less educated, and of lower income. Women who endorsed SI reported worse mental health functioning, physical health functioning, and BPS/IC symptoms. Women with SI were more likely to have received mental health treatment, but did not differ on whether they had received BPS/IC treatment. Multivariate logistic regression analyses indicated that severity of BPS/IC symptoms did not independently predict likelihood of endorsing SI.

Conclusions

Results suggest that BPS/IC severity may not increase the likelihood of SI except via severity of depression symptoms. Additional work is needed to understand how to address the increased needs of women with both BPS/IC and SI.

Keywords: suicidal ideation, interstitial cystitis, bladder pain syndrome

Introduction

Bladder pain syndrome/interstitial cystitis (BPS/IC) is a chronic pain syndrome, characterized by bladder pain and voiding symptoms such as urinary urgency or frequency. Primarily affecting women, it is a condition of unknown etiology with no known cure. Treatment is directed at symptom management and pain control. Symptoms of BPS/IC can often be debilitating and can affect work, family, interpersonal relationships, sleep, and sexual activity11,17. Similar to other chronic pain syndromes such as fibromyalgia, chronic fatigue syndrome, and irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), BPS/IC symptoms are associated with an increased prevalence of mental health disorders including depression5. Given the chronic and debilitating nature of BPS/IC, concerns have been raised that the condition may be associated with significantly higher risk of suicide and hopelessness25. However, little is known about the population prevalence of suicidal ideation (SI) among patients with BPS/IC.

Individuals with both chronic pain and depression have more severe symptoms and a worse clinical prognosis for both disorders. Among patients being treated for pain conditions, depression is associated with more pain complaints, worse pain, longer duration of pain, and a greater likelihood of non-recovery1. Among patients with depression, pain is associated with a delay in diagnosis and treatment, more severe depression, functional limitations, and worse health-related quality of life1. Studies focused on BPS/IC patients have reported a wide range of prevalence estimates for depression (5 % to >50 %), although less is known about the prevalence in community populations with BPS/IC symptoms5,8,12,20.

In addition to an increased risk for depression, women with BPS/IC may be at increased risk for suicide. Suicidal ideation and attempts are among the most important risk factors for completed suicide2,16. One study of treatment seeking patients found that patients with BPS/IC are three to four times as likely to report SI as the general population9. Increased suicidality has been demonstrated in other chronic pain conditions. One review suggested that risk of death by suicide appeared to be at least doubled in chronic pain patients, with lifetime suicide attempts ranging between 5% and 14% and lifetime SI at approximately 20%23. While it is possible that the burden of BPS/IC may be associated with a greater prevalence of SI, estimates based on national representative samples have not yet been available. Further, identification of the characteristics associated with SI in these women may help practitioners identify and assist this higher risk group. In this population of women, it is also unclear whether SI is primarily accounted for by depression symptoms, or whether severity of BPS/IC symptoms is an independent predictor of SI.

This paper has three objectives. First, we describe the prevalence of SI among women with BPS/IC symptoms in a nationally representative sample. Second, we compare how women with SI differ from women without SI by demographics, mental health problem severity, bladder symptom severity, health and mental health functioning, and treatment utilization. Finally, we multivariately model correlates of SI among women with BPS/IC symptoms.

Materials and Methods

Participants and Recruitment

Data were collected as part of the RAND Interstitial Cystitis Epidemiology (RICE) Study, which was approved by the RAND Human Subjects Protection Committee (HSPC). As a first stage, the study screened 146,246 households with telephones over a one-year period to identify those with a female age 18 or over with bladder symptoms. A second stage of screening was used to identify women who met BPS/IC symptom criteria and did not meet exclusion criteria. The case definitions used in this study have been described previously and the screening and interviewing methods are described in detail elsewhere3,4. Households that were identified as having one or more women with IC/BPS symptoms then underwent a more intensive 90-minute telephone interview. The present analysis was limited to women who met criteria for the RICE high specificity case definition, which includes: (1) pain, pressure or discomfort in the pelvic area; (2) daytime urinary frequency 10+ times OR urgency due to pain, pressure, or discomfort (not fear of wetting); (3) pain worsens as bladder fills; (4) bladder symptoms did not resolve after treatment with antibiotics; and (5) no prior treatment with hormone injection therapy for endometriosis; and who were asked about the presence of SI (N=1,019)3. Participants interviewed prior to the development of an HSPC-approved protocol for responding to reports of suicidal ideation, or who were interviewed when no clinician was on call, were not asked about suicidal ideation.

Population weights were applied related to the first stage of screening. Non-response weights were created as the inverse of predicted probabilities from a logistic regression model in which the outcome was whether or not the household was successfully screened. Logistic regression found no differences (p>0.05 for all measures) between patients not asked about SI and those who were asked with respect to age, race/ethnicity, education, BPS/IC symptom/severity measures, and a variety of measures of depression and co-occurring anxiety disorders. Therefore, no additional weights were necessary to account for what appears to have been effectively random subselection into screening for SI.

Measures

Depression symptoms

We used the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ) to assess severity of depression symptoms. The PHQ-9 is a 9-item self-report measure that assesses the nine depression symptoms from the DSM-IV depression criteria13. It was developed from the depression module of the Primary Care Evaluation of Mental Disorders (PRIME-MD) and was validated for use in primary care settings. The PHQ-9 has been shown to have good reliability and validity in primary care populations. Subsequently it has been used in a wide variety of populations and settings13,21,22. Each item on the PHQ-9 is scored on a 4-point scale (0–3) and items are summed to create a total score, with higher scores indicating worse depression symptoms. The ninth item on the PHQ-9 assesses suicidal ideation (described below); therefore, we removed this item before computing a summary score. This version, referred to as the PHQ-8, has been used frequently when it is not practical to assess for suicidality14. Respondents were also asked whether they had “ever been diagnosed by a doctor” with depression.

Suicidal ideation

Women with suicidal ideation were identified based on their response to a single PHQ-9 item asking how often the respondent had been bothered by ‘thoughts that you would be better off dead, or of hurting yourself in some way’ over the past two weeks. Respondents who indicated ‘several days,’ ‘more than half of the days,’ or ‘nearly every day’ were considered to have reported suicidal ideation, while respondents who selected ‘not at all’ were not. For respondents who reported suicidal ideation, two additional follow-up items were administered to determine the respondent’s current level of risk and provide follow-up from a clinician if necessary. These items assessed whether the respondent was having suicidal ideation currently (‘is this how you feel right now’) and whether the respondent had a plan to attempt suicide (‘have you thought about it so much that you’ve planned a way to do it’). Items assessing ideation and intent were only asked of respondents when a clinician was available to conduct a follow-up assessment. Following the HSPC approved protocol, respondents who endorsed having suicidal ideation at the time of the call received a follow-up call from a licensed mental health professional (KAH; KEW) within 4 hours. The clinician assessed the level of risk, including whether the respondent was currently receiving treatment for a mental health condition, and whether additional assistance was necessary to ensure the safety of the respondent.

Co-occurring anxiety disorders

We used two brief screening measures developed for use in primary care to screen for possible current generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) and panic disorder. The two-item GAD scale has a sensitivity of 0.92 and a specificity of 0.74 for a diagnosis of GAD, while the two-item panic scale has a sensitivity of 0.92 and a specificity of 0.74 for a diagnosis of panic disorder15.

Bladder Pain Syndrome/interstitial cystitis

BPS/IC symptom severity was assessed with the Interstitial Cystitis Symptom Index (ICSI) and Problem Index (ICPI), tandem instruments that assess the presence and degree of IC symptoms (ICSI) and their associated distress (ICPI)19. We assessed pain by asking respondents about how much pain they experienced from their bladder symptoms “most of the time” on a 1–10 scale.

Functioning

We evaluated functional status using the Short Form-3624. This measure was used to create two composite measures reflecting mental health functioning and physical health functioning. Scores were generated using age and gender adjusted US population norms and range from 0 to 100, with higher scores indicating better functioning.

Treatment utilization

We assessed self-reported BPS/IC and mental health-related treatment utilization. Respondents were asked to report whether they received any BPS/IC care in the past 12 months, the number of BPS/IC-related visits in the past 12 months, and whether they have a regular doctor who provides care for their BPS/IC. Mental health-related utilization included whether they had received any mental health care in the past 12 months, the number of mental health-related visits in the past 12 months, and whether they were taking antidepressant medication.

Demographics

Demographic characteristics were also collected, including age, race/ethnicity, education level, marital status, employment status, annual income and uninsured status.

Statistical Analyses

All analyses employed weights to account for the sample design and non-response, and accounted for the design effects of such weights using the linearization method26. Descriptive statistics regarding the population prevalence, frequency, and intensity of suicidal ideation were computed. Women with and without suicidal ideation were compared based on demographics, severity of depression symptoms, severity of BPS/IC symptoms, physical and mental health functioning, and treatment utilization. Sample characteristics were compared using linear/logistic regression for continuous and categorical variables, respectively. We used multivariate logistic regression models predicting the presence of SI to evaluate whether severity of BPS/IC symptoms is an independent predictor of SI after accounting for depression severity. Predictors were entered in three stages aimed at evaluating the unique contribution of BPS/IC symptoms to SI. Depression symptoms were entered first (PHQ-8), followed by demographic characteristics (age, race/ethnicity, marital status, and educational level), followed by BPS/IC severity. Finally, we further explored the relationship between depression symptoms, BPS/IC symptoms, and SI by computing the prevalence of SI within four groups defined by cross-tabulations of BPS/IC severity and depression symptoms.

Results

As shown in Table 1, of 1,019 women with BPS/IC symptoms who were asked about suicidal ideation, 11.0% reported SI in the past 2 weeks. Approximately 3% of these women reported having SI more than half of the days in the past two weeks. Of those who endorsed SI in the past 2 weeks, nearly 26% reported feeling that way currently (2.9% of the population). Of these, 31% reported having a plan to commit suicide. Therefore, of the full sample, nearly 1% reported having current SI and a plan, suggesting they were currently at risk for attempting suicide.

Table 1.

Prevalence of suicidal ideation among women with BPS/IC symptoms (N = 1,019)

| % | 95% Confidence Intervals |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Any Suicidal Ideation | 11.0 | 8.7–13.3 | |

| Frequency of Suicidal Ideation | |||

| Not at all | 89.0 | 86.8–91.3 | |

| Several days | 8.0 | 6.0–9.9 | |

| More than half the days | 1.5 | 0.7–2.4 | |

| Nearly every day | 1.5 | 0.7–2.4 | |

| Currently feeling suicidal | 2.9 | 1.9–3.9 | |

| Have a plan to commit suicide | 0.9 | 0.3–1.5 | |

Note: Weighted results

Among women with BPS/IC symptoms, those with SI were more likely to be younger, unemployed, unmarried, uninsured, and have high school or less education and lower income (Table 2). Differences by race/ethnicity were also observed, with respondents in the “other” race/ethnicity group being more likely to endorse SI. As expected, women with SI also reported more depression symptoms and were more likely to have been told by a doctor that they have depression. Women with SI were also more likely to screen positive for GAD and panic disorder. Women with SI reported more severe BPS/IC problems and symptoms. In addition, women with SI reported worse physical and mental health functioning. There were no differences observed between the groups on receiving care for BPS/IC symptoms, including whether they had received treatment in the past year, number of visits for BPS/IC, or whether they were seeing a urologist or other physician for their BPS/IC care. Women with SI were more likely to have received treatment for a mental health concern and reported more visits to a mental health provider in the past year, and were more likely to be taking antidepressant medication.

Table 2.

Characteristics of women with and without suicidal ideation among women with BPS/IC symptoms

| No Suicidal Ideation (n=902) |

Suicidal Ideation (n=117) |

χ2 or t statistic |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | |||

| Age (mean) | 46.8 | 43.1 | t = 2.5* |

| Race/Ethnicity (%) | χ2 = 13.7** | ||

| Hispanic | 7.1 | 5.1 | |

| White | 80.5 | 76.9 | |

| Black | 8.0 | 9.2 | |

| Other | 4.5 | 8.8 | |

| Education (%) | χ2 = 35.2**** | ||

| High school or less | 32.0 | 48.5 | |

| Some college | 36.3 | 26.8 | |

| College graduate | 31.7 | 24.7 | |

| Employed in past month (%) | 55.7 | 40.6 | χ2 = 26.3**** |

| Married/Living as married (%) | 61.6 | 35.2 | χ2 = 82.2**** |

| Annual income (%) | χ2 = 19.0*** | ||

| < $10,000 | 15.8 | 30.0 | |

| $10,000 – $29,999 | 40.8 | 34.8 | |

| $30,000 – $49,999 | 26.3 | 25.7 | |

| $50,000 + yr | 17.2 | 9.4 | |

| Uninsured (%) | 12.0 | 17.7 | χ2 =8.5** |

| Mental Health | |||

| PHQ-8 (mean) | 7.4 | 16.1 | t = −15.8**** |

| Self-reported depression diagnosis (%) | 43.9 | 83.5 | χ2 = 179.5**** |

| Generalized Anxiety Disorder, positive screen (%) | 60.9 | 91.9 | χ2 = 120.3**** |

| Panic Disorder, positive screen (%) | 46.7 | 81.5 | χ2 = 138.8**** |

| Bladder Problem Severity | |||

| IC Symptom Index score (mean) | 11.5 | 12.7 | t = −3.6*** |

| IC Problem Index score (mean) | 14.1 | 15.3 | t = −3.5*** |

| Functioning | |||

| SF-36 MH composite score (age/gender adjusted mean) | 46.6 | 32.3 | t = 14.5**** |

| SF-36 PH composite score (age/gender adjusted mean) | 40.1 | 35.5 | t = 3.9*** |

| Treatment | |||

| Any treatment for bladder symptoms in past 12 mos (%) | 44.7 | 43.7 | Ns |

| Past yr # visits to MD for bladder symptoms (mean) | 1.5 | 1.4 | Ns |

| Have a regular treatment provider for IC (%) | Ns | ||

| Treatment with urologist | 9.0 | 5.6 | |

| Treatment with other MD | 31.6 | 33.2 | |

| Not in treatment | 59.4 | 61.2 | |

| Any treatment in past year with MH provider (%) | 23.0 | 49.3 | χ2 = 103.1**** |

| Past yr # visits for MH visits to MH provider (mean) | 3.1 | 7.1 | t = −3.5*** |

| Antidepressant meds in past 3 months (%) | 26.7 | 47.7 | χ2 = 61.4**** |

Note:

p = <.05;

p = <.01;

p =<.001;

Weighted results using survey procedures

As expected, multivariate logistic regression analyses confirmed that increased depression symptoms were associated with higher likelihood of endorsing SI (Table 3). Among the demographic variables included in the model, only marital status (being unmarried) significantly predicted higher likelihood of endorsing SI. Severity of BPS/IC symptoms was not multivariately associated with endorsing SI, suggesting that BPS/IC severity does not increase the likelihood of SI except possibly via severity of depression symptoms. This relationship was clarified by a modified multivariate model in which we removed depression symptoms (while retaining the other demographic variable from the original model). When depression symptoms were removed, BPS/IC severity was a significant predictor of SI (p<.01), similar to what was observed in the bivariate models.

Table 3.

Multivariate logistic regression analyses to predict suicidal ideation among women with IC symptoms (N=1017)

| Variable | OR (95% CI) | Significance |

|---|---|---|

| PHQ-8 (standardized) | 4.73 (3.57–6.27) | p = <0.001 |

| Age (per year) | 0.98 (0.96–1.00) | p = 0.0729 |

| Race/Ethnicity (compared with non-Hispanic White): | ||

| Hispanic | 0.60 (0.20–1.83) | p = 0.3717 |

| African-American | 0.72 (0.25–2.07) | p = 0.5434 |

| Other race | 0.95 (0.35–2.57) | p = 0.9173 |

| Not Married/Living as Married | 2.70 (1.54–4.73) | p = 0.0005 |

| Education (compared with college graduates): | ||

| No College | 0.83 (0.39–1.78) | p = 0.6374 |

| Some College | 0.49 (0.22–1.13) | p = 0.0932 |

| IC Symptom Index score (standardized) | 0.91 (0.68–1.22) | p = 0.5106 |

Note: Weighted results using survey procedures

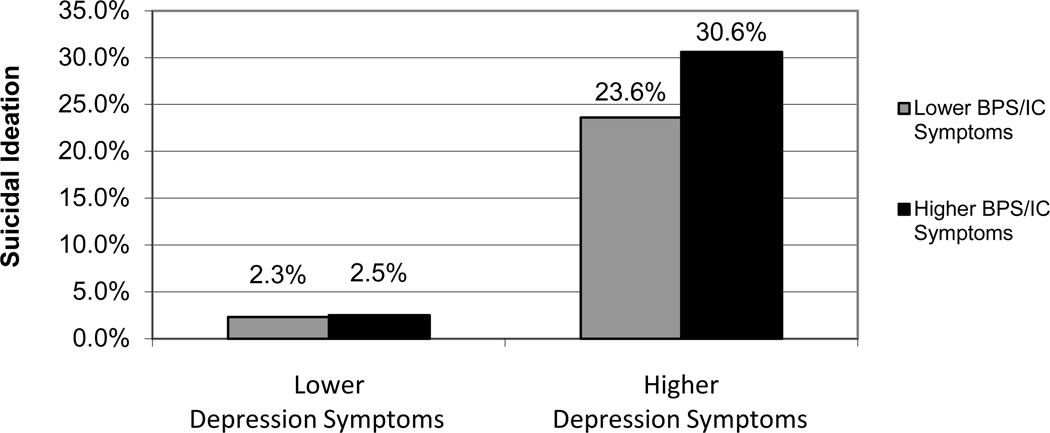

To further illustrate the relationship between depression, BPS/IC, and suicide, Figure 1 shows SI prevalence by subgroups of higher and lower depression symptoms (PHQ-8 >=10/<10) crossed with higher and lower BPS/IC symptoms (ICSI >=12/<12). This figure highlights that depression symptoms are much more strongly associated with SI than is BPS/IC severity, and that women with higher depression symptoms have higher incidence of SI at both higher and lower levels of BPS/IC symptoms.

Figure 1.

Prevalence of Suicidal Ideation by Depression and BPS/IC Symptoms

Note: Weighted % (unweighted n). Lower depression symptoms = PHQ-8 under 10; lower BPS/IC symptoms = ICSI Symptom Scores under 12.

Comment

The results of this study provide valuable and previously unavailable information about the prevalence and risk factors of suicidal ideation in women with BPS/IC symptoms. In this nationally representative sample, 11% of women with BPS/IC symptoms endorsed having ‘thoughts that you would be better off dead, or of hurting yourself in some way’ in the prior two weeks, a rate markedly higher than national estimates of past 12 month prevalence from the National Comorbidity Study (3.3%), although we do not have national prevalence estimates for a matched sample10. In our sample, 3% of women endorsed having these thoughts more than three days a week and nearly 1% of the total sample endorsed having both SI and a plan to commit suicide at the time of the call. We believe this is the first study to describe the population prevalence of SI among women with BPS/IC symptoms, and highlights the increased risk for suicide among women with BPS/IC symptoms compared to the general population.

Bivariate analyses of women who endorsed SI compared to women who did not highlighted that women with SI were more likely to be younger, unemployed, unmarried, uninsured, less educated, and of lower income. This pattern of risk factors is similar to what has been observed in non-treatment seeking community populations across multiple countries18. In addition, they were sicker across a variety of health and mental health domains. Among women with BPS/IC symptoms, those who endorsed SI reported worse mental health symptoms, including worse symptoms of depression and increased probability of having a diagnosis of depression, generalized anxiety disorder, and panic disorder diagnoses. Depression symptoms were moderately correlated with a positive screen for GAD (r = 0.46) and panic disorder (r = 0.41), which is consistent with the overlap between these symptoms observed in other populations6. Bivariate analyses also indicated that these women reported worse BPS/IC symptoms. Their physical and mental health functioning were significantly worse than women without SI. Given the increased severity of mental health symptoms, it is not surprising that women with SI also reported greater mental health treatment utilization and were more likely to be taking antidepressant medication. It is notable that these women did not show similar increased utilization of treatment for BPS/IC, particularly given the increased severity in BPS/IC symptoms.

In previous work, the relative contribution of depression and BPS/IC symptoms to increased risk of suicide has been unclear. Our results suggest that severity of depression symptoms is a significant predictor of the presence of SI. Further, after accounting for severity of depression symptoms, BPS/IC symptom severity was not a significant predictor of SI. This suggests that factors other than the IC/BPS symptoms may account for the SI in these respondents. We are unable to evaluate the possibility of an additional factor that might influence both depression and BPS/IC symptoms, or whether BPS/IC symptoms worsen depression, but the multivariate association of BCS/IC severity with SI in the absence of depression suggests a possible mechanism in which BCS/IC severity may increase SI risk via increased depression severity. Previous work suggests that pain-related coping strategies, specifically pain-related catastrophizing, predicts increased SI in chronic pain patients7. Such mechanisms merit further study.

Some limitations to this study should be noted. Our analyses focused primarily on recent SI and did not assess whether the women had any history of SI or suicide attempts. Further, we used a single, self-report item to identify women with SI. While there may be some error in relying on this approach, this screening method mirrors how clinicians conduct screening for suicide risk, and is common in studies of suicide in chronic pain23. We also relied on self-report to measure treatment utilization, which may be affected by recall bias. It is also important to note that a diagnosis of BPS/IC requires a clinical evaluation, which was not performed in this study. Therefore, while study subjects endorsed bladder symptoms consistent with a diagnosis of BPS/IC, we cannot state with certainty that all would have been diagnosed with the condition after a clinical evaluation. Finally, respondents were only asked about SI when a clinician was available to conduct clinical follow-up when necessary. However, we examined our data for evidence of selection bias and found none.

Conclusions

In summary, our study suggests that more than 1 in 10 women with BPS/IC symptoms have had recent thoughts of suicide, a rate markedly higher than in the overall US population. However, our results suggest that increased BPS/IC symptoms are not the primary or direct driver of SI in this population. Nonetheless, this does not minimize the importance for screening for depression symptoms across treatment settings (primary care, urology, mental health specialty) in a group with high SI risk. The presence of a chronic pain condition, such as BPS/IC, negatively affects the recognition and treatment of depression1. Patients who are diagnosed with BPS/IC should receive assessment for depression symptoms, including suicidal ideation. Additional work is needed to understand how to address the increased needs of women with both BPS/IC and SI.

Acknowledgements

Funding support was received from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; grant number is U01DK070234-05.

Footnotes

The authors report no conflicts of interest related to this work.

References

- 1.Bair MJ, Robinson RL, Katon W, et al. Depression and pain comorbidity: A literature review. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163(20):2433–2445. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.20.2433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beck AT, Weishaar ME. Suicide risk assessment and prediction. Crisis. 1990;11:22–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Berry SH, Bogart LM, Pham C, et al. Development, validation and testing of an epidemiologic case definition for interstitial cystitis/ painful bladder syndrome. J Urol. 2010;183:1848–1852. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2009.12.103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Berry SH, Elliott MN, Suttorp MJ, et al. Prevalence of symptoms of bladder pain syndrome/interstitial cystitis among adult females in the U.S. J Urol. 2011;186(2):540–544. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2011.03.132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Clemens JQ, Brown SO, Calhoun E. Mental health diagnoses in patients with interstitial cystitis/painful bladder syndrome and chronic prostatitis/chronic pain syndrome: A case study. J Urol. 2008;180(4):1378–1382. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2008.06.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dobson KS. The relationship between anxiety and depression. Clin Psychol Rev. 1985;5(4):307–324. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Edwards RR, Smith MT, Kudel I, et al. Pain-related catastrophizing as a risk factor for suicidal ideation in chronic pain. Pain. 2006;12615(1–3):272–279. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2006.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Goldstein HB, Safaeian P, Garrod K, et al. Depression, abuse and its relationship to interstitial cystitis. Int Urogynecol J. 2008;19(12):1683. doi: 10.1007/s00192-008-0712-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Held PJ, Hanno PM, Wein AJ, et al. Epidemiology of interstitial cystitis. In: Hanno PM, Staskin DR, Krane RJ, Wein AJ, editors. Interstitial cystitis. Vol. New York: Springer-Verlag; 1990. pp. 29–48. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kessler RC, Berglund P, Borges G, et al. Trends in suicide ideation, plans, gestures, and attempts in the united states 1990–1992 to 2001–2003. JAMA. 2005;293(20):2487–2495. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.20.2487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Koziol JA, Clark DC, Gittes RF, et al. The natural history of interstitial cystitis: A survey of 374 patients. J Urol. 1993;149(3):465–469. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)36120-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Koziol JA, Clark DC, Gittes RF, et al. The natural history of interstitial cystitis: A survey of 374 patients. J Urol. 1993;149:465–469. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)36120-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: Validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16:601–613. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kroenke K, Strine T, Spitzer R, et al. The PHQ-8 as a measure of current depression in the general population. J Affect Disord. 2008;114(1–3):163–173. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2008.06.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Means-Christensen AJ, Sherbourne CD, Byrne PP, et al. Using five questions for five common mental disorders in primary care: Diagnostic accuracy of the anxiety and depression detector. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2006;28:108–118. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2005.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Morgan HG, Stanton R. Suicide among psychiatric in-patients in a changing clinical scene. Suicidal ideation as a paramount index of short-term risk. Br J Psychiatry. 1997;171:561–563. doi: 10.1192/bjp.171.6.561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nickel JC, Tripp D, Teal V, et al. Sexual function is a determinant of poor quality of life for women with treatment refractory interstitial cystitis. J Urol. 2007;177:1832–1836. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2007.01.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nock MK, Borges G, Bromet EJ, et al. Cross-national prevalence and risk factors for suicidal ideation, plans and attempts. Br J Psychiatry. 2008;192:98–105. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.107.040113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.O'Leary MP, Sant GR, Fowler FJ, Jr, et al. The interstitial cystitis symptom index and problem index. Urology. 1997;49(5A Suppl):58–63. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(99)80333-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rothrock NE, Lutgendorf SK, Hoffman A, et al. Depressive symptoms and quality of life in patients with interstitial cystitis. J Urol. 2002;167:1763–1767. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB. Validation and utility of a self-report version of prime-MD: The PHQ primary care study. JAMA. 1999;282:1737–1744. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.18.1737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Spitzer RL, Williams JB, Kroenke K, et al. Validity and utility of the prime-MD patient health questionnaire in assessment of 3000 obstetric-gynecologic patients: The prime-md patient health questionnaire obstetrics-gynecology study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2000;183:759–769. doi: 10.1067/mob.2000.106580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tang N, Crane C. Suicidality in chronic pain: A review of the prevalence, risk factors, and psychological links. Psychol Med. 2006;36:575–586. doi: 10.1017/S0033291705006859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ware JE, Jr, Kosinksi M, Gandek B. Sf-36 health survey: Manual & interpretation guide. 1st edition. QualityMetric Inc., Lincoln, RI; 2005. pp. 1–231. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Webster DC, Brennan T. Self-care effectiveness and health outcomes in women with interstitial cystitis: Implications for mental health clinicians. Issues Ment Health Nurs. 1998;19:495–519. doi: 10.1080/016128498248926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wooldridge JM. Econometric analysis of cross section and panel data. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]