Abstract

Lateral habenula (LHb) projections to the ventral midbrain, including the rostromedial tegmental nucleus (RMTg) conveys negative reward-related information, but the behavioral ramifications of selective activation of this pathway remain unexplored. We found that exposure to aversive stimuli in mice increased LHb excitatory drive onto RMTg neurons. Further, optogenetic activation of this pathway promoted active, passive, and conditioned behavioral avoidance. These data demonstrate that activity of LHb efferents to the midbrain is aversive, but can also serve to negatively reinforce behavioral responding.

Neural circuits mediating reward and aversion become disrupted in neuropsychiatric diseases such as drug addiction, anxiety disorders, and depression1,2. Ventral tegmental area (VTA) dopamine neurons show changes in firing patterns in response to both rewarding and aversive associated stimuli3,4. While dopamine neurons encode salient stimuli and predictive cues, the neural circuit elements that provide dopamine neurons with reward- and aversive-related information are not well defined. LHb neurons signal punishment and prediction errors5. The LHb sends excitatory projections to VTA and RMTg neurons6–8, which can inhibit dopamine neuron output9,10. While correlative evidence suggests that LHb neurons convey anti-reward and aversive information, the behavioral consequences of LHb-to-RMTg activation remains unexplored. Here, we used ex vivo and in vivo optogenetic strategies to investigate how aversive stimuli alters LHb-to-RMTg glutamatergic transmission, and how direct manipulation of this pathway affects behavior.

To selectively activate LHb efferents to the RMTg, we introduced channelrhodopsin-2 fused to an enhanced yellow fluorescent protein (ChR2-EYFP) in the LHb of mice using viral methods (Supplementary Fig. 1a–c). We observed LHb terminal expression of ChR2-EYFP in midbrain structures, including the VTA and RMTg (Fig. 1a,b, Supplementary Fig. 1d). Whole cell recordings from RMTg neurons in brain slices revealed that light pulses, to selectively stimulate LHb ChR2-expressing efferent fibers, resulted in inward currents that were blocked by the glutamatergic receptor antagonist DNQX (Supplementary Fig. 1e,f).

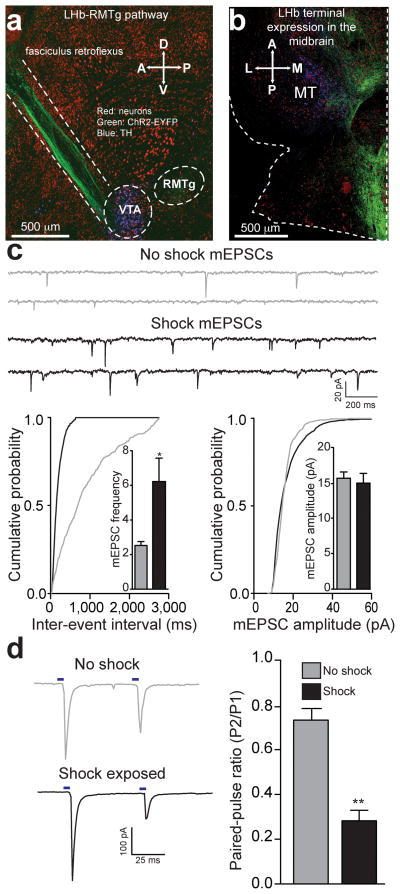

Figure 1. Acute unpredictable foot shock exposure enhances LHb-to-RMTg glutamate release.

(a) Sagittal confocal image showing expression of ChR2-EYFP (green) in the LHb-to-midbrain pathway via the fasciculus retroflexus fiber bundle following injection of the viral construct into the LHb. Midbrain TH+ dopamine neurons are shown in blue. A, Anterior; P, Posterior; D, Dorsal, V, Ventral. (b) Horizontal confocal image showing the distribution of LHb terminals in the midbrain. M, medial; L, lateral. (c) Top: representative mEPSC traces recorded from neurons from mice immediately following either 0 or 19 unpredictable foot shocks. Bottom Left: Representative cumulative mEPSC inter-event interval probability plot. Inset: Average mEPSC frequency was significantly increased in neurons from shock exposed mice (t(13) = 2.88, p = 0.01). Bottom Right: Representative cumulative mEPSC amplitude probability plot. Inset: Average mEPSC amplitude was not altered in RMTg neurons from shock exposed mice (t(13) = 0.12, p = 0.91). (d) Left: Representative optically evoked paired-pulse ratios from LHb efferents onto RMTg neurons. Right: Average paired-pulse ratios showing that paired-pulse ratios at LHb-to-RMTg synapses were significantly depressed from mice that received foot shocks (t(14) = 3.56, p = 0.003). n = 8 cells/group. All error bars for all figures correspond to the s.e.m. * indicates p < 0.05 and ** indicates p < 0.01 for all figures.

We then determined the anterior-posterior distribution of LHb-to-midbrain functional connectivity by recording from dopaminergic and non-dopaminergic neurons following optical stimulation of LHb efferents in th-ires-GFP transgenic mice. Fibers originating from the LHb were predominantly localized to the posterior VTA and RMTg and the majority of light-responsive neurons were non-dopamine neurons located in the RMTg and posterior VTA (Fig. 1b, Supplementary Fig. 1g,h).

Since neurotransmission by LHb neurons may encode information related to aversive stimuli processing11, we explored whether exposure to an aversive stimulus altered excitatory neurotransmission at LHb-to-RMTg synapses. We exposed mice expressing ChR2-EYFP in LHb-to-RMTg fibers to either 0 or 19 unpredictable foot shocks in a single 20-min session. One hour later, we performed whole-cell recordings from RMTg neurons in close proximity to LHb-to-RMTg ChR2-EYFP-positive fibers. Voltage clamp recordings from RMTg neurons from foot shock-exposed mice displayed an increase in the frequency of miniature excitatory postsynaptic currents (mEPSCs) compared to non-shocked controls (Fig. 1c). Furthermore, LHb-to-RMTg glutamate release probability was significantly enhanced following shock exposure, as indexed by a reduction in the optically-evoked paired pulse ratio (Fig. 1d). We observed no differences in mEPSC amplitude or optically-evoked AMPA/NMDA ratios, measurements of postsynaptic glutamate receptor number or function (Fig. 1c, Supplementary Fig. 2). These data suggest that aversive stimuli exposure enhances presynaptic transmission from LHb inputs to RMTg neurons.

To determine whether optogenetic stimulation of LHb-to-RMTg fibers has behavioral consequences, we optogenetically stimulated this pathway in behaving mice at 60-Hz as this was the mean light-evoked firing rate of LHb neurons in brain slices (Supplementary Fig. 1b,c and Supplementary Fig. 3). To determine if optogenetic stimulation of LHb-to-RMTg fibers resulted in passive avoidance behavior, we tested mice in a real-time place preference chamber. When an experimental mouse crossed over into a counter-balanced stimulated-designated, contextually indistinct side of an open field, light stimulation was constantly pulsed until the mouse crossed back into the non-stimulated designated side (Fig. 2a). Mice expressing EYFP spent equal times on both sides of the chamber, whereas mice expressing ChR2-EYFP spent significantly less time on the stimulated side (Fig. 2a, Supplementary Video 1) and made significantly more escape attempts (Supplementary Fig. 4a). There were no differences in total distance traveled or average velocity between ChR2-EYFP and EYFP mice across the entire session (Supplementary Fig. 4b,c). These data suggest that acute activation of LHb-to-RMTg fibers promotes location-specific passive avoidance behavior.

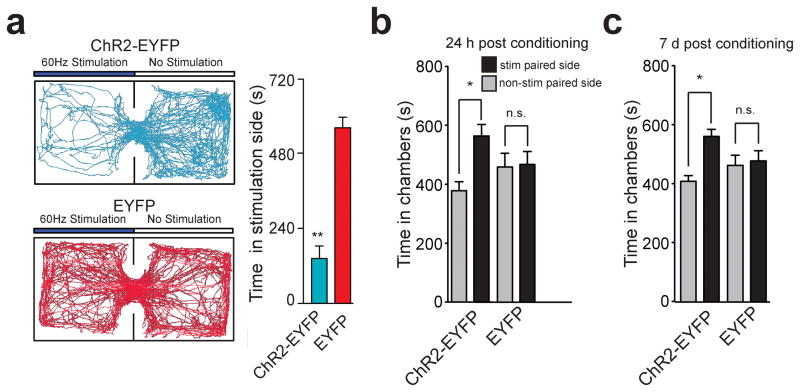

Figure 2. Activation of LHb inputs to the RMTg produces behavioral avoidance.

(a) Left: Real-time place preference location plots from two representative mice showing the animal’s position over the course of the 20-min session. Right: ChR2-EYFP-expressing mice spent significantly less time on the stimulated-paired side (t(10) = 7.90, p < 0.0001). n = 6 mice/group for real-time place preference. (b) ChR2-EYFP-expressing mice spent significantly less time in the stimulation-paired chamber compared to the non-stimulation-paired chamber 24 hrs after the last stimulation conditioning session (t(7) = 3.54, p = 0.01). EYFP-expressing did not show a preference (t(7) = 0.57, p = 0.58). (c) ChR2-EYFP-expressing mice spent significantly less time in the stimulation paired chamber compared to the non-stimulation-paired chamber 7 days after the last stimulation session (t(7) = 3.24, p = 0.01). EYFP-expressing mice did not show a preference (t(7) = 0.17, p = 0.86). n = 8 mice/group for conditioned place preference.

While activation of the LHb-to-RMTg pathway induced acute avoidance, we next determined if activation of this pathway produced conditioned avoidance using a standard nonbiased conditioned place preference paradigm. 24 hrs after the last conditioning session, where optogenetic stimulation was paired with a distinct context, ChR2-EYFP-expressing mice showed a significant conditioned place aversion for the stimulation-paired chamber, while the EYFP-expressing mice showed no preference or aversion (Fig. 2b). This conditioned place aversion was maintained in the ChR2-EYFP-expressing mice 7 days following the last conditioning session (Fig. 2c), demonstrating that activity in this pathway also promotes conditioned avoidance.

To determine if mice would perform an operant response to actively avoid activation of LHb-to-RMTg fibers, ChR2-EYFP or EYFP expressing mice were placed in chambers where they could nose-poke to terminate optogenetic stimulation of LHb-to-RMTg fibers (Supplementary Fig. 5a). ChR2-EYFP-expressing mice learned to nose-poke to terminate laser stimulation over 3 daily training sessions (Supplementary Fig. 6). Following training, ChR2-EYFP-expressing mice made significantly more active nose-pokes to terminate LHb-to-RMTg activation compared to EYFP-expressing mice (Fig. 3a–c), resulting in a significant increase in the percentange of time the stimulation was off (percent time stimulation was off: ChR2-EYFP: 47.5 ± 7.1 %; EYFP: 2.8 ± 0.9 %; t(10) = 6.28, p < 0.0001). These data demonstrate that LHb-to-RMTg activity can negatively reinforce behavioral responding.

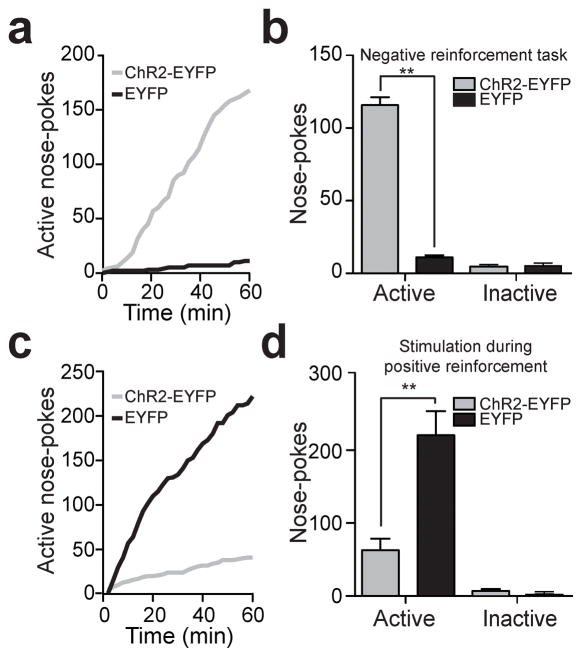

Figure 3. Activation of LHb inputs to the RMTg produces active behavioral avoidance and disrupts positive reinforcement.

(a) Example cumulative records of active nose-pokes made by a ChR2-EYFP and an EYFP-expressing mouse to terminate LHb-to-RMTg optical activation. (b) Average number of active nose-pokes from one behavioral session in following training (> 4 days; t(10) = 20.52, p < 0.0001). There was no difference in inactive nose-pokes between the two groups (t(10) = 0.29, p = 0.78). n = 6 mice per group. (c) Example cumulative records of active nose-pokes made by a ChR2-EYFP and an EYFP-expressing mouse when optical stimulation was paired with the nose-poke to receive a sucrose reward. (d) Average number of active and inactive nose-pokes during positive reinforcement (t(14) = 4.01, p < 0.01). There was no difference in inactive nose-pokes between the two groups (t(14) = 1.22, p = 0.24). n = 8 mice per group.

Next, we examined whether LHb-to-RMTg activation disrupted positive reinforcment. We trained a separate group of mice to nose-poke to earn liquid sucrose rewards. Following stable responding, nosepokes to earn sucrose in subsequent test sessions where paired with a 2s, 60-Hz LHb-to-RMTg stimulation (Supplementary Fig. 5b). ChR2-EYFP-expressing mice receiving stimuliations made significantly fewer nose-pokes compared to EYFP-expressing mice and took significantly longer to retrieve and consume the rewards (Fig. 3c,d; Supplementary Fig. 7, Supplementary Video 2). Importantly, there were no significant differences between the two groups in the session prior when nosepokes were not paired with LHb-to-RMTg stimulation (t(14) = 1.64, p = 0.12), suggesting that stimulation of this pathway time-locked to an operant response served as a punishment.

We found that activation of LHb terminals in the RMTg promotes active, passive, and conditioned behavioral avoidance, suggesting that endogenous activity of LHb glutamatergic inputs to the RMTg conveys information related to aversion. The data presented here suggest that the LHb’s connection with midbrain GABA neurons is crucial for promoting these behaviors. Consistent with this, direct excitation of VTA GABA neurons disrupts reward-related behaviors10 and stimulation of VTA GABA neurons or inhibition of VTA dopamine neurons promotes aversion12. Importantly, optogenetic stimulation of LHb terminals in the RMTg suppressed positive reinforcement and supported negative reinforcement, demonstrating this pathway can bidirectionally effect the same behavioral response (nose-poking) depending on the task. Dopamine signaling in the nucleus accumbens (NAc) promotes positive reinforcement2,3. Thus, motivated behavior to suppress activation of the LHb-to-RMTg pathway may also depend on dopamine signaling in the NAc. Although encoding negative consequences requires multiple neural circuits, activation of glutamatergic presynaptic inputs to the LHb13,14 or LHb inputs to the midbrain alone produces aversion. Since LHb projections are phylogenetically well-conserved15, neurotransmission in this pathway is likely essential for survival by promoting learning and subsequent behavior to avoid stimuli associated with negative consequence.

Online Methods

Experimental subjects and stereotaxic surgery

We grouped housed adult (25–30g) male C57BL/6J mice (Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME) until surgery. We anesthetized the mice with 150 mg/kg ketamine and 50 mg/kg xylazine and placed the mice in a stereotaxic frame (Kopf Instruments). We bilaterally microinjected 0.4 μL of purified and concentrated AAV (~1012 infections units/mL, packaged and titered by the UNC Vector Core Facility) into the LHb (coordinates from Bregma:−1.7 AP, ± 0.48 ML, −3.34 DV). LHb neurons were transduced with virus coding ChR2-EYFP or EYFP under the control of the human synapsin (hsyn) promoter. Following surgery, we individually housed the mice. For behavioral experiments, we also implanted mice with a unilateral chronic fiber directed above the RMTg (coordinates from Bregma: −3.9 AP, ± 0.3 ML, −4.8 DV). We performed all experiments 6–8 weeks following surgeries. We conducted all procedures in accordance with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, as adopted by NIH, and with approval of the UNC Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees.

Histology, immunohistochemistry, and microscopy

We anesthetized mice with pentobarbital and perfused with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) followed by 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS. We subjected 40 μm brain sections to immunohistochemical staining for neuronal cell bodies and/or tyrosine hydroxylase (TH: Pel Freeze, made in sheep; Neurotrace: Invitrogen, 640 nm excitation/660 nm emission or 435 nm excitation/455 nm emission) as previously described10. We mounted sections and captured Z-stack and tiled images on a Zeiss LSM Z10 confocal microscope using a 20x or 63x objective. For determination of optical fiber placements, we imaged tissue at 10x on an upright fluorescent microscope. We recorded optical stimulation sites as the location in tissue where visible optical fiber tracks terminated.

Slice preparation for patch-clamp electrophysiology

We prepared brain slices for patch-clamp electrophysiology as previously described10,16. Briefly, we anesthetized mice with pentobarbital and perfused transcardially with modified aCSF. We then rapidly removed the brains and placed them in the same solution used for perfusion, at ~0°C. We cut sagittal midbrain slices containing the RMTg (200μm) or horizontal midbrain slices containing the VTA and RMTg (200μm) on a vibratome (VT-1200, Leica Microsystems) and placed the slices in a holding chamber and allowed to recover for at least 30 min before recordings.

Patch-clamp electrophysiology

We made whole-cell voltage-clamp recordings of RMTg neurons as previously described16. Briefly, we back filled patch electrodes (3.0–5.0 MOmega;) for current clamp recordings, with a potassium-gluconate internal solution10. For voltage clamp recordings, we backfilled patch electrodes with a cesium methansulfonic acid internal solution17. For optical stimulation of EPSCs, we used light pulses from an LED coupled to a 40x microscope objective (1 ms pulses of 1–2 mW, 473 nm) to evoke presynaptic glutamate release from LHb projections to RMTg. For mEPSCs and optically evoked EPSCs, we voltage-clamped RMTg neurons at −70 mV. For AMPAR/NMDAR experiments the holding potential was +40 mV. We added picrotoxin (100 mM) to the external solution to block GABAA receptor-mediated IPSCs for all experiments. For mEPSCs, we added tetrodotoxin (TTX, 500 nM) to the external solution to suppress action potential driven release. We calculated the AMPA/NMDA ratio and paired pulse ratio as previously described18. We averaged 6 sweeps together to calculate both the AMPA/NMDA ratio and the paired pulse ratio. We collected mEPSCs for 5 minutes or until 300 mEPSCs were collected. To determine where, anterior-posterior, midbrain neurons were light responsive, we injected TH-IRES-GFP mice with hsyn-ChR2-EYFP into the LHb. We voltage-clamped (−70mV) GFP-positive (TH+) and GFP-negative (TH−) midbrain neurons and categorized the cells as light-responsive if a light pulse resulted in an average evoked current across 6 sweeps of > 20 pA.

Shock paradigm for patch-clamp electrophysiology

We placed mice expressing ChR2-EYFP in the LHb-to-RMTg pathway into standard mouse behavioral chambers (Med Associates) equipped with a metal grid floor capable of delivery foot shocks for 20 min. Mice received either 19 or 0 unpredictable foot shocks (0.75 mA, 500 ms). We presented shocks with a pseudo-random inter-stimulus interval of 30, 60, or 90 s. 1 hr following the end of the session, we anesthetized mice for patch-clamp electrophysiology (described above).

In vivo optogenetic excitation

For all behavioral experiments, we injected mice with a ChR2-EYFP or EYFP coding virus and also implanted with a chronic unilateral custom made optical fiber targeted to the RMTg as described previously19. 3 days prior to the experiment, we connected mice to a ‘dummy’ optical patch cable each day for 30–60 min to habituate them to the tethering procedure. Following the tethering procedure, we then ran mice in the behavioral paradigms (see below). We used a 10 mW laser with a stimulation frequency of 60 Hz and a 5 ms light pulse duration for all behavioral experiments.

Real time place-preference

We placed mice in a custom-made behavioral arena (50 × 50 × 25 cm black plexiglass) for 20 min. We assigned one counterbalanced side of the chamber as the stimulation side. We placed the mouse in the non-stimulated side at the onset of the experiment and each time the mouse crossed to the stimulation side of the chamber, we delivered a 60-Hz constant laser stimulation until the mouse crossed back into the non-stimulation side. We recorded behavioral data via a CCD camera interfaced with Ethovision software (Noldus Information Technologies). We defined an escape attempt as each time a mouse attempted to climb out of the apparatus. We only scored an attempt if no paws were on the ground.

Conditioned place preference

The CPP apparatus (Med Associates) consisted of a rectangular cage with a left black chamber (17 cm × 12.5 cm) with a vertical metal bar floor, a center gray chamber (15 cm × 9 cm) with a smooth gray floor, and a right white chamber (17 cm, × 12.5 cm) with a wire mesh floor grid. We monitored mouse location within the chamber using a computerized photo-beam system. The CPP test consisted of 4 days. Day 1 consisted of a preconditioning test that ensured that mice did not have a preference for one particular side20. On days 2 and 3, we placed the mice into either the black or white side of the chamber (counterbalanced across all mice) and we delivered either 0.5-s of 60-Hz stimulation with an interstimulus interval of 1 s for 20 mins, or no stimulation. Approximately 4 hrs later, we placed the mice into the other side of the chamber and the mice received the other treatment. 24 hrs after the last conditioning session, we placed the mice back into the chamber with all three chambers accessible, to assess preference for the stimulation and non-stimulation paired chamber. To assess long-term associations between the stimulation and context, we placed the mice back in the chambers 7 days later.

Negative and positive reinforcement procedures

Behavioral training and testing occurred in mouse operant chambers interfaced with optogenetic stimulation equipment as described previously1. For the negative reinforcement procedure, we placed mice into the chamber and delivered 500 ms of 60-Hz optical stimulation with an inter-stimulus interval of 1 s. We trained mice on a fixed ratio (FR1) training schedule, in which each nose-poke resulted in one 20-s period where the laser was shut off, and the LHb-to-RMTg pathway was not optogenetically activated. In addition, a tone and houselight cue turned on for the entire 20 seconds and turned off when the laser stimulation returned. For the positive reinforcement procedure, we food restricted a separate group of mice to 90% of their free-feeding bodyweight. We then trained mice for one session per day for 1 hr in the operant chambers on a FR1 schedule (in which each nose-poke resulted in 20 uL of a 15% sucrose solution). In addition, a tone and houselight cue turned on for 2 s. Once the mice reached stable behavioral responding (as determined by 3 days of over 100 active nose-pokes that did not vary by more than 20% from the first of the three days), mice received 2s of 60-Hz optical stimulation time locked to the cue following each active nose-poke. For both behaviors, we recorded inactive nose-pokes, but these had no programmed consequences. In addition, we collected and time-stamped the number of active and inactive nose-pokes.

Data analysis

We used t-tests and one or two-way analyses of variance (ANOVA) to analyze all behavioral and electrophysiological data when applicable. When we obtained significant main effects, we performed Tukey’s HSD post hoc tests for group comparison. For all behavioral experiments, we analyzed the data in Ethovision, Matlab, Excel, and Prism. We used 6 mice per group for the real time place preference and negative reinforcement experiments and 8 mice per group for the CPP and positive reinforcement experiments. We used no more than 2 neurons from a given animal for patch-clamp electrophysiology in the aversive stimuli exposure experiments.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Randall Ung and Dr. Vladimir Gukassyan and the UNC Neuroscience Center Microscopy Facility, and the Stuber lab for discussion. We thank Dr. Karl Deisseroth for opsin constructs, and UNC vector core for viral packaging. We thank Dr. Cameron Good for sagittal slice preparation advice. This study was supported by NARSAD, ABMRF, The Whitehall Foundation, The Foundation of Hope, NIDA (DA029325 and DA032750) (G.D.S.). A.M.S. was supported by the UNC Neurobiology Curriculum training grant (T32 NS007431).

Footnotes

Author contributions:

A.M.S. collected all data. A.M.S. and G.D.S. designed the experiments, analyzed data, and wrote the manuscript.

References

- 1.Shin LM, Liberzon I. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2010;35:169–191. doi: 10.1038/npp.2009.83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Koob GF, Volkow ND. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2010;35:217–238. doi: 10.1038/npp.2009.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schultz W, Dayan P, Montague PR. Science. 1997;275:1593–1599. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5306.1593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brischoux F, Chakraborty S, Brierley DI, Ungless MA. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:4894–4899. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0811507106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bromberg-Martin ES, Hikosaka O. Nat Neurosci. 2011;14:1209–1216. doi: 10.1038/nn.2902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jhou TC, Fields HL, Baxter MG, Saper CB, Holland PC. Neuron. 2009;61:786–800. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Perrotti LI, et al. Eur J Neurosci. 2005;21:2817–2824. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2005.04110.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Matsui A, Williams JT. J Neurosci. 2011;31:17729–17735. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4570-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ji H, Shepard PD. J Neurosci. 2007;27:6923–6930. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0958-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.van Zessen R, Phillips JL, Budygin EA, Stuber GD. Neuron. 2012;73:1184–1194. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.02.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Matsumoto M, Hikosaka O. Nat Neurosci. 2009;12:77–84. doi: 10.1038/nn.2233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tan KR, et al. Neuron. 2012;73:1173–1183. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.02.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li B, et al. Nature. 2011;470:535–539. doi: 10.1038/nature09742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shabel SJP, Trias CD, Murphy A, Malinow RT. Neuron. 2012;74:475–481. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.02.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stephenson-Jones M, Floros O, Robertson B, Grillner S. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:E164–173. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1119348109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stuber GD, et al. Nature. 2011;475:377–380. doi: 10.1038/nature10194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stuber GD, Hnasko TS, Britt JP, Edwards RH, Bonci A. J Neurosci. 2010;30:8229–8233. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1754-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stuber GD, et al. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2008;32:1714–1720. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2008.00749.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sparta DR, et al. Nat Protoc. 2012;7:12–23. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2011.413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cunningham CL, Gremel CM, Groblewski PA. Nat Protoc. 2006;1:1662–1670. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.