Abstract

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is an autoimmune disease with diverse clinical manifestations characterized by the development of pathogenic autoantibodies manifesting in inflammation of target organs such as the kidneys, skin and joints. Genome-wide association studies have identified genetic variants in the UBE2L3 region that are associated with SLE in subjects of European and Asian ancestry. UBE2L3 encodes an ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme, UBCH7, involved in cell proliferation and immune function. In this study, we sought to further characterize the genetic association in the region of UBE2L3 and use molecular methods to determine the functional effect of the risk haplotype. We identified significant associations between variants in the region of UBE2L3 and SLE in individuals of European and Asian ancestry that exceeded a Bonferroni corrected threshold (P < 1 × 10−4). A single risk haplotype was observed in all associated populations. Individuals harboring the risk haplotype display a significant increase in both UBE2L3 mRNA expression (P = 0.0004) and UBCH7 protein expression (P = 0.0068). The results suggest that variants carried on the SLE associated UBE2L3 risk haplotype influence autoimmunity by modulating UBCH7 expression.

Keywords: Systemic Lupus Erythematosus, UBE2L3, Multi Ethnic Association Study, UBCH7 Expression

INTRODUCTION

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is a chronic autoimmune disease characterized by self-reactive antibodies that form immune complexes leading to systemic inflammation and organ failure. SLE susceptibility is strongly influenced by both genetic and environmental factors. Recent candidate gene and genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have identified more than 30 susceptibility loci for SLE 1–8. Single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in the region of UBE2L3, which encodes the ubiquitin conjugating enzyme, UBCH7, demonstrate association with SLE in multiple independent SLE cohorts of European and African American ancestry 9,10 and correlate most significantly with patients developing anti-dsDNA antibodies 11. Variants in the region of UBE2L3 have also been reported to be associated with several other autoimmune disorders such as Crohn’s disease 12, 13, celiac disease 14 and rheumatoid arthritis 9, 14. Gene expression studies suggest that variants in the vicinity of UBE2L3 regulate UBE2L3 expression, thus providing a potential mechanism by which UBE2L3 influences susceptibility to autoimmune diseases 13.

Post-translational ubiquitination of proteins is an important process in eukaryotes that is responsible for the degradation of short-lived and abnormal cytosolic proteins and the regulation of cellular signaling pathways 15. Three classes of enzymes, ubiquitin-activating enzymes (E1s), ubiquitin-conjugating enzymes (E2s) and ubiquitin-protein ligases (E3s) constitute the system by which ubiquitin is transferred to target proteins. UBE2L3, located at chromosome 22q11.2, is a member of the E2 ubiquitin conjugating enzyme family and has been demonstrated to participate in the ubiquitination of p53 16, c-Fos, and the NF-κB precursor p105 in vitro 17, 18. Recent studies have further revealed that UBE2L3 is involved in cell proliferation 19.

In order to more thoroughly evaluate the UBE2L3 locus in SLE, we fine mapped and imputed SNPs in five diverse ethnic populations using a custom genotyping array, publicly available datasets of human variation and a targeted resequencing dataset enriched for subjects with SLE risk haplotypes. We identified a single 67kb risk haplotype associated with SLE and characterized the effect of the risk haplotype on gene expression by using quantitative-PCR and Western blotting. Our data demonstrate that both UBE2L3 mRNA transcripts and UBCH7 protein expression is increased by variants carried on the SLE risk haplotype, suggesting a mechanism by which variants in the region of UBE2L3 influence the pathogenesis of SLE.

RESULTS

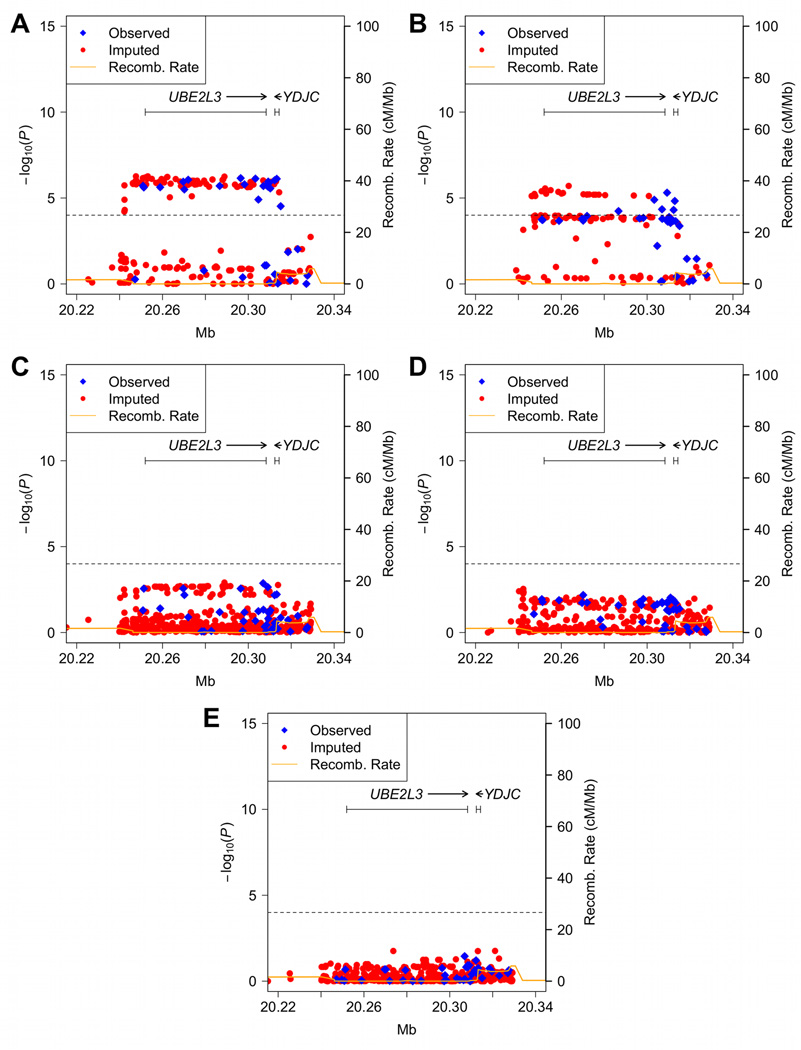

Genome-wide association studies have identified genetic association with variants in the vicinity of UBE2L3 and multiple autoimmune diseases. In an effort to identify the causal variants responsible for association with SLE, we genotyped 57 SNPs in and around UBE2L3 along with 347 ancestry-informative markers (AIMs) in 8922 independent SLE cases and 8077 independent controls across five ethnic populations (Table 1, Supplementary Figure 1, Supplementary Tables 1, 2 and 3). After applying a series of quality control filters, 55 genotyped SNPs and 262 AIMs were available for further analyses. To enrich our dataset for additional untyped SNPs, we imputed a minimum of 285 SNPs from the 1000 Genomes Project. Single-marker logistic regression analyses, adjusting for gender and global ancestry estimates, revealed significant associations between multiple SNPs and SLE surpassing a Bonferroni corrected P < 1 × 10−4. In individuals of European-ancestry the strongest signal was observed at rs131658 (P = 6.50 × 10−7, odds ratio [OR] = 1.24, 95% confidence interval [CI] = 1.14–1.35, Figure 1A). In the Asian population the strongest signal occurred at rs5754177 (P = 1.98 × 10−6, OR = 1.33, 95% CI = 1.18–1.50, Figure 1B). We also observed weaker evidence of association not exceeding the Bonferroni corrected threshold in other populations with the optimal signals at rs11089629 for African Americans (P = 1.23 × 10−3, OR = 1.18, 95% CI = 1.07–1.30, Figure 1C), rs390408 for Hispanics (P = 2.89 × 10−3, OR = 1.23, 95% CI = 1.07–1.42, Figure 1D) and rs11705317 for Gullah (P = 1.74 × 10−2, OR = 0.27, 95%CI = 0.09–0.79, Figure 1E). When all populations were combined in meta-analysis, rs7444 produced the most significant association (Pcombined = 2.21 × 10−14, Supplementary Table 4) with no evidence of heterogeneity (the Cochran’s Q test P = 0.672 and the inconsistency index I2 = 0%, see Methods).

Table 1.

Samples available for analysis following quality control adjustments.

| Population | Number of Samples |

Case | Control | Male | Female |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| African- American |

3338 | 1527 | 1811 | 695 | 2643 |

| Asian | 2525 | 1265 | 1260 | 253 | 2272 |

| European- ancestry |

7427 | 3936 | 3491 | 1495 | 5932 |

| AA-Gullah | 275 | 152 | 123 | 33 | 242 |

| Hispanic1 | 2299 | 1492 | 807 | 207 | 2092 |

| Total | 15864 | 8372 | 7492 | 2683 | 13181 |

enriched for Amerindian-European admixture

Figure 1.

SNPs in and around the UBE2L3 region associated with SLE. (A) European-ancestry, (B) Asian, (C) African American, (D) Hispanic and (E) African-American Gullah populations. The dashed line in each panel signifies the Bonferroni corrected level of significance (P = 1 × 10−4). The orange solid line denotes the recombination rate calculated from the combined HapMap CEU, YRI and CHB+JPT data.

To capture novel variants enriched on the UBE2L3 risk haplotype that were not genotyped or imputed with the 1000 Genomes Project reference panel, we resequenced 174 subjects of European-ancestry enriched for SLE risk haplotypes including UBE2L3. The phased haplotypes of these sequenced individuals were then imputed into the European-ancestry dataset. This procedure added 5 novel variants (3 SNPs and 2 deletion/insertion polymorphisms [DIPs]) that were not present in dbSNP 132 (Supplementary Table 5). Among these five variants, a single base insertion located in the 3’ UTR of UBE2L3 demonstrated significant association with SLE (P = 2.56 × 10−6, OR = 1.23, 95% CI = 1.13–1.33) and is in strong linkage disequilibrium with the most significant SNP in European-ancestry (rs131658, r2 = 0.99).

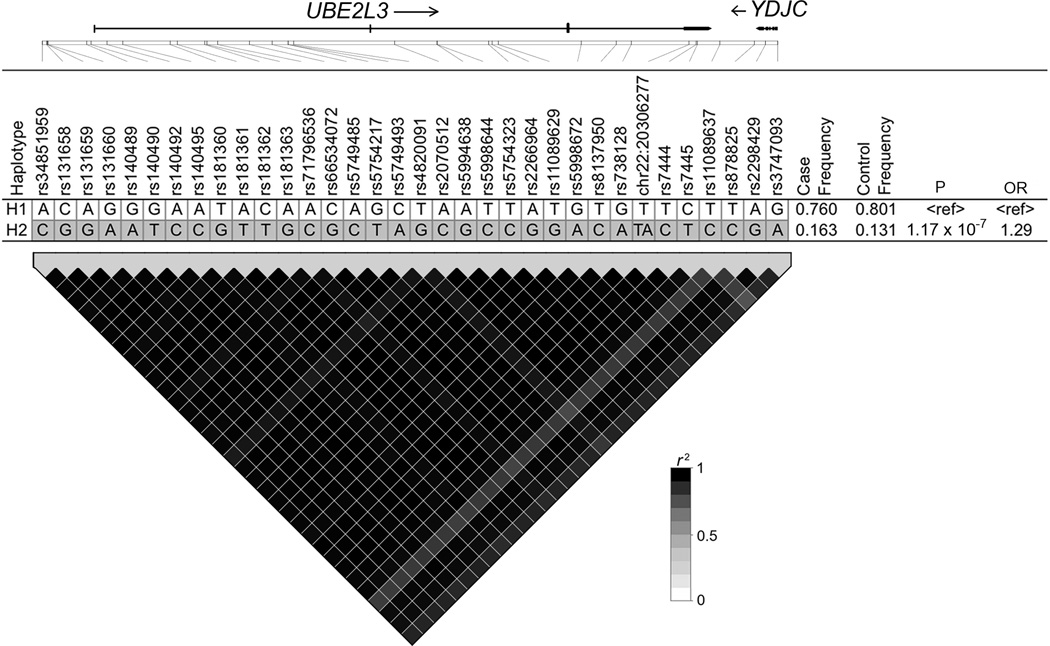

To determine if differences in the linkage disequilibrium patterns across populations (trans-population mapping) could help define a minimal risk segment, we performed haplotype analysis using the thirty-four variants with P < 1 × 10−4 defined in subjects of European-ancestry (Table 2). In the European-ancestry population we observed a single 67 kb risk haplotype (P = 1.17 × 10−7) spanning the UBE2L3 region (haplotype H2, Figure 2). Similarly, a single risk haplotype harboring the majority of alleles in the EA risk haplotype was also present in Asian (haplotype H2, Supplementary Figure 2A), African American (haplotypes H2, Supplementary Figure 2B), and Hispanic populations (haplotype H2, Supplementary Figure 2C). Strong linkage disequilibrium was observed on the risk haplotype in all four populations and limited the utility of trans-population mapping or conditional analysis to further isolate a minimal risk segment. These results suggest that a single risk effect common to these populations may be responsible for the association with SLE.

Table 2.

SNPs in the region of UBE2L3 associated with SLE.

| SNP | BP (hg18) | SNP Statusa |

Allelesb | European-ancestry |

Asian |

African-American |

Hispanic |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MAFc | ORd | Pe | MAFc | ORd | Pe | MAFc | ORd | Pe | MAFc | ORd | Pe | ||||

| rs34851959 | 20247239 | i-seq | A/C | 0.198 | 1.22(1.12–1.33) | 4.72E-06 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| rs131658 | 20247626 | i-1kGP | C/G | 0.204 | 1.24(1.14–1.35) | 6.50E-07 | 0.464 | 1.23(1.1–1.37) | 0.0002279 | 0.418 | 1.11(1–1.23) | 0.04387 | 0.422 | 1.18(1.04–1.35) | 0.01071 |

| rs131659 | 20247708 | i-1kGP | A/G | 0.205 | 1.23(1.13–1.34) | 1.41E-06 | 0.456 | 1.22(1.09–1.37) | 0.0004743 | 0.418 | 1.17(1.05–1.3) | 0.003587 | 0.420 | 1.17(1.03–1.33) | 0.01988 |

| rs131660 | 20247757 | i-1kGP | G/A | 0.204 | 1.24(1.14–1.35) | 9.46E-07 | 0.448 | 1.25(1.12–1.4) | 0.0001051 | 0.420 | 1.17(1.05–1.29) | 0.004152 | 0.422 | 1.17(1.03–1.33) | 0.01787 |

| rs140489 | 20251294 | g | G/A | 0.212 | 1.23(1.13–1.33) | 2.41E-06 | 0.470 | 1.24(1.11–1.38) | 0.0001899 | 0.451 | 1.17(1.05–1.29) | 0.002789 | 0.425 | 1.17(1.03–1.33) | 0.01682 |

| rs140490 | 20251686 | i-1kGP | G/T | 0.204 | 1.22(1.12–1.33) | 2.92E-06 | 0.468 | 1.24(1.11–1.39) | 0.0001357 | 0.451 | 1.17(1.06–1.29) | 0.002583 | 0.425 | 1.18(1.04–1.34) | 0.01292 |

| rs140492 | 20253144 | i-1kGP | A/C | 0.203 | 1.23(1.13–1.33) | 2.66E-06 | 0.468 | 1.24(1.11–1.39) | 0.0001321 | 0.451 | 1.17(1.05–1.29) | 0.002767 | 0.425 | 1.18(1.04–1.34) | 0.01307 |

| rs140495 | 20254589 | i-seq | A/C | 0.198 | 1.23(1.13–1.34) | 2.43E-06 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| rs181360 | 20258916 | g | T/G | 0.210 | 1.23(1.13–1.33) | 2.36E-06 | 0.470 | 1.23(1.1–1.38) | 0.0002145 | 0.136 | 1.17(1.01–1.36) | 0.03956 | 0.401 | 1.18(1.04–1.35) | 0.01308 |

| rs181361 | 20259566 | i-1kGP | A/T | 0.206 | 1.22(1.12–1.33) | 4.28E-06 | 0.453 | 1.24(1.11–1.39) | 0.0001672 | 0.451 | 1.17(1.06–1.29) | 0.002585 | 0.425 | 1.18(1.04–1.34) | 0.01324 |

| rs181362 | 20262068 | i-1kGP | C/T | 0.206 | 1.23(1.13–1.34) | 1.88E-06 | 0.467 | 1.24(1.11–1.39) | 0.0001435 | 0.451 | 1.17(1.05–1.29) | 0.002853 | 0.425 | 1.18(1.04–1.34) | 0.01269 |

| rs181363 | 20262264 | i-1kGP | A/G | 0.205 | 1.23(1.13–1.34) | 1.82E-06 | 0.467 | 1.24(1.11–1.39) | 0.0001453 | 0.471 | 1.16(1.04–1.28) | 0.005006 | 0.427 | 1.19(1.04–1.35) | 0.00928 |

| rs71796536 | 20263251 | i-seq | A/C | 0.195 | 1.23(1.12–1.33) | 3.80E-06 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| rs66534072 | 20266152 | i-1kGP | C/G | 0.207 | 1.23(1.13–1.34) | 0.467 | 1.24(1.11–1.39) | 0.0001438 | 0.451 | 1.17(1.05–1.29) | 0.002834 | 0.425 | 1.18(1.04–1.34) | 0.01249 | |

| rs5749485 | 20268224 | i-1kGP | A/C | 0.205 | 1.23(1.13–1.33) | 2.18E-06 | 0.467 | 1.24(1.11–1.38) | 0.0001458 | 0.439 | 1.18(1.06–1.3) | 0.001982 | 0.424 | 1.19(1.04–1.35) | 0.00949 |

| rs5754217 | 20269675 | g | G/T | 0.213 | 1.23(1.13–1.34) | 1.13E-06 | 0.468 | 1.24(1.11–1.38) | 0.0001626 | 0.452 | 1.17(1.06–1.29) | 0.002735 | 0.425 | 1.17(1.03–1.33) | 0.01885 |

| rs5749493 | 20269687 | i-1kGP | C/A | 0.207 | 1.23(1.13–1.34) | 1.70E-06 | 0.467 | 1.24(1.11–1.38) | 0.0001477 | 0.448 | 1.17(1.06–1.29) | 0.002355 | 0.425 | 1.17(1.03–1.34) | 0.01508 |

| rs4820091 | 20270189 | g | T/G | 0.198 | 1.23(1.13–1.34) | 3.17E-06 | 0.467 | 1.23(1.1–1.38) | 0.0002087 | 0.446 | 1.15(1.04–1.27) | 0.006538 | 0.411 | 1.2(1.05–1.37) | 0.00657 |

| rs2070512 | 20279411 | i-1kGP | A/C | 0.205 | 1.23(1.13–1.33) | 2.30E-06 | 0.467 | 1.24(1.11–1.38) | 0.0001648 | 0.451 | 1.17(1.05–1.29) | 0.002846 | 0.426 | 1.18(1.04–1.34) | 0.01191 |

| rs5994638 | 20283276 | i-1kGP | A/G | 0.206 | 1.23(1.13–1.34) | 1.80E-06 | 0.464 | 1.24(1.11–1.39) | 0.0001257 | 0.472 | 1.15(1.04–1.27) | 0.005997 | 0.428 | 1.18(1.03–1.34) | 0.01349 |

| rs5998644 | 20283288 | i-1kGP | T/C | 0.205 | 1.23(1.13–1.34) | 2.13E-06 | 0.464 | 1.24(1.11–1.39) | 0.0001257 | 0.472 | 1.15(1.04–1.27) | 0.005997 | 0.428 | 1.18(1.03–1.34) | 0.01349 |

| rs5754323 | 20287992 | i-1kGP | T/C | 0.207 | 1.23(1.13–1.34) | 1.68E-06 | 0.467 | 1.24(1.11–1.38) | 0.0001449 | 0.464 | 1.15(1.04–1.28) | 0.005267 | 0.427 | 1.19(1.04–1.35) | 0.00980 |

| rs2266964 | 20288304 | i-1kGP | A/G | 0.206 | 1.23(1.13–1.34) | 1.83E-06 | 0.467 | 1.24(1.11–1.38) | 0.0001449 | 0.451 | 1.17(1.06–1.29) | 0.002659 | 0.426 | 1.18(1.04–1.34) | 0.01161 |

| rs11089629 | 20288872 | i-1kGP | T/G | 0.206 | 1.23(1.13–1.34) | 1.16E-06 | 0.467 | 1.24(1.11–1.38) | 0.0001809 | 0.473 | 1.18(1.07–1.3) | 0.001234 | 0.428 | 1.18(1.04–1.34) | 0.01319 |

| rs5998672 | 20296442 | g | G/A | 0.214 | 1.24(1.14–1.34) | 7.01E-07 | 0.463 | 1.24(1.11–1.39) | 0.0001527 | 0.452 | 1.17(1.05–1.29) | 0.002772 | 0.426 | 1.17(1.03–1.33) | 0.01667 |

| rs8137950 | 20299640 | i-1kGP | T/C | 0.204 | 1.22(1.12–1.33) | 4.35E-06 | 0.460 | 1.22(1.09–1.37) | 0.0003816 | NA | NA | NA | 0.417 | 1.15(1.01–1.32) | 0.03141 |

| rs738128 | 20301010 | i-1kGP | G/A | 0.206 | 1.23(1.13–1.33) | 2.32E-06 | 0.464 | 1.24(1.11–1.39) | 0.0001217 | 0.451 | 1.16(1.05–1.29) | 0.002988 | 0.426 | 1.18(1.04–1.34) | 0.01195 |

| chr22:20306277 | 20306277 | i-seq | T/TA | 0.203 | 1.23(1.13–1.33) | 2.56E-06 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| rs7444 | 20306934 | i-1kGP | T/C | 0.206 | 1.23(1.13–1.34) | 1.37E-06 | 0.462 | 1.26(1.13–1.41) | 4.56E-05 | 0.496 | 1.18(1.07–1.3) | 0.001353 | 0.433 | 1.17(1.03–1.33) | 0.01698 |

| rs7445 | 20307047 | g | C/T | 0.211 | 1.23(1.13–1.33) | 2.00E-06 | 0.465 | 1.24(1.11–1.39) | 0.0001635 | 0.161 | 1.15(1–1.32) | 0.04677 | 0.403 | 1.17(1.03–1.33) | 0.01962 |

| rs11089637 | 20309096 | g | T/C | 0.178 | 1.24(1.14–1.36) | 2.16E-06 | 0.464 | 1.24(1.11–1.38) | 0.0001858 | 0.445 | 1.17(1.06–1.3) | 0.002278 | 0.411 | 1.17(1.03–1.34) | 0.01802 |

| rs878825 | 20312249 | g | T/C | 0.215 | 1.23(1.13–1.34) | 9.30E-07 | 0.470 | 1.23(1.1–1.38) | 0.0002118 | 0.488 | 1.15(1.04–1.27) | 0.006683 | 0.432 | 1.18(1.04–1.34) | 0.01276 |

| rs2298429 | 20313260 | g | A/G | 0.209 | 1.24(1.14–1.35) | 7.64E-07 | 0.471 | 1.23(1.1–1.38) | 0.0002233 | 0.469 | 1.15(1.04–1.27) | 0.006024 | 0.426 | 1.17(1.03–1.33) | 0.01845 |

| rs3747093 | 20314379 | i-1kGP | G/A | 0.212 | 1.19(1.09–1.29) | 4.68E-05 | 0.466 | 1.23(1.1–1.38) | 0.0003042 | NA | NA | NA | 0.433 | 1.16(1.02–1.32) | 0.02673 |

SNP Status: genotyped (g), imputed SNP from the 1000 Genomes Project (i-1kGP), or imputed SNP from sequencing data (i-seq).

Major/minor.

Minor allele frequency.

The odds ratio (OR) was calculated with respect to the minor allele.

Adjusted for sex and global ancestry estimates.

Figure 2.

Analyses of 34 associated SNPs present on UBE2L3 region in European-ancestry population. Top: UBE2L3 haplotype association analysis with haplotype frequencies > 5%. Alleles in white boxes represent the major alleles and those in gray boxes represent the minor allele for each haplotype. Bottom: the plot of the pairwise linkage disequilibrium (LD) of 34 associated SNPs with the intensity color for r2 superimposed.

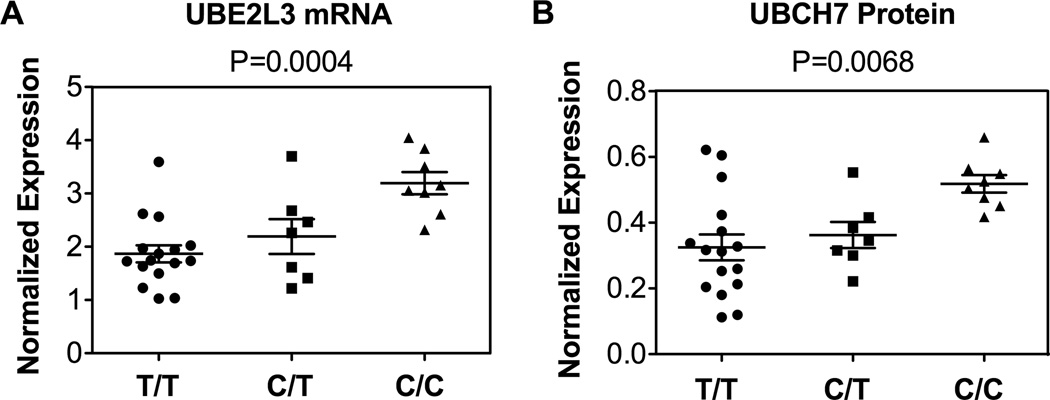

Previous studies have demonstrated that variants in the region of UBE2L3 influence UBE2L3 transcript expression 13, therefore, we evaluated whether the SLE associated risk haplotype produced a similar molecular phenotype. To evaluate UBE2L3 mRNA and UBCH7 protein expression, quantitative real-time PCR and western blotting was performed in an independent set of EBV-transformed B cell lines under resting conditions. Cell lines were selected based on whether they contained 0, 1, or 2 copies of the UBE2L3 risk haplotype as defined by the rs7444-C risk allele. Concordant with other published studies, we observed increased UBE2L3 mRNA expression and increased expression of UBCH7 protein as a function of the number of copies of the risk haplotype (P = 0.0004 and P = 0.0068, respectively (one-way ANOVA), Figures 3A, 3B and Supplementary Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Effect of the risk haplotype on UBE2L3 (A) mRNA and UBCH7 (B) protein expression. On the X-axis, the three different genotypes for SNP rs7444 are displayed corresponding to homozygote of risk haplotype (C/C), heterozygote (C/T), and homozygote of non-risk haplotype (T/T). On the Y-axis is the level of normalized expression for UBE2L3 for each assay. Each data point represents the expression level of UBE2L3 mRNA or UBCH7 protein for one individual.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we observed significant associations between variants in UBE2L3 and SLE in individuals of European, Asian, and African-American ancestry. Weaker association evidence was also observed in the Hispanic and Gullah populations due in part to the smaller samples sizes of these two groups (Table 1). Risk variants were carried on a 67 kb risk haplotype tagged by the proxy SNP rs7444, in all populations demonstrating association with SLE. Since the variants in this haplotype block were highly correlated across the different populations, we were unable to further narrow this SLE associated DNA segment using conditional analyses or trans-population mapping.

In line with data published in Crohn’s Disease, we observed higher levels of UBE2L3 mRNA and UBCH7 protein expression in EBV cell lines carrying the risk haplotype. This suggests that similar molecular mechanisms in UBE2L3 that influence susceptibility to autoimmunity are shared between SLE and CD. The precise mechanism by which causal variants on the UBE2L3 risk haplotype influence expression of UBE2L3 is not yet defined but we hypothesize that this could be due to the modification of mRNA stability and/or modification of the binding affinity of transcription factors to the UBE2L3 promoter. Further studies geared toward identification of the causal variant(s), which underlies the effect on gene and protein expression are required.

Ubiquitination is a critical post-translational protein modification for regulation of NF-κB signaling 20, however, little is known about how UBCH7 mediated ubiquitination might impact NF-κB signaling. In a cell free system, Orian et al. demonstrated that the NF-κB precursor protein, p105, was a substrate for UBCH7 mediated ubiquitination. At rest, p105, encoded by the gene, NF-κB1, undergoes constitutive proteosomal processing to yield the NF-κB subunit, p50 18. Unprocessed p105 functions as an inhibitor of NF-κB by retaining p50 homodimers in the cytoplasm using ankyrin repeats located in the C-terminal portion of the protein 21. Following cellular activation, p105 is phosphorylated and undergoes complete proteosomal degradation, allowing bound p50 homodimers to translocate to the nucleus. It is possible that UBCH7 mediated ubiquitination of p105 may result in increased proteosomal processing and/or degradation of p105, resulting in increased levels of free p50 homodimers.

UBCH7 has been demonstrated to function with the HECT (homologous to the E6-associated protein carboxy terminus) family E3 ubiquitin ligase, ITCH, in in vitro ubiquitination assays 22, 23. ITCH participates in regulation of NF-κB along with RNF11, TAX1BP1 and A20 as part of a protein complex known at the ubiquitin-editing complex 24. Recent data demonstrates that UBCH7 is restricted to HECT and RBR (RING-in-between-RING) type E3 ligases which underscores the possibility that UBCH7 and ITCH could function together to ubiquitinate substrate proteins, however, to our knowledge, a physical interaction between ITCH and UBCH7 has not yet been demonstrated in vivo.

In summary, our data support a role for variants in the UBE2L3 locus in the predisposition to SLE in multiple ethnic populations. The UBE2L3 locus demonstrates low haplotype diversity with a single risk haplotype associated with SLE. This risk haplotype carries causal variants that result in increased expression of UBE2L3 transcripts and UBCH7 protein. Future work will now focus on the isolation and characterization of the variants that result in this expression phenotype and on the role of UBCH7 function in immune cell signaling.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Subjects

In this study, the following independent case and control subjects were collected, respectively: African-American (1,569/1,893), Asian (1,328/1,348), European-ancestry (4,248/3,818), African-American Gullah (155/131) and Hispanic enriched for the Amerindian-European admixture (1,622/887) populations (Supplementary Table 1). SLE cases were determined by meeting at least four of the eleven 1997 ACR revised criteria for SLE. Case and control samples were obtained from multiple sites with the Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval from each institution and processed at the Oklahoma Medical Research Foundation (OMRF) under the OMRF IRB.

Genotyping and Quality Control

The Illumina iSelect platform at OMRF was employed to genotype 57 SNPs and 347 genome-wide ancestry-informative markers (AIMs) 25, 26. SNP quality control (QC) measures included well-defined cluster scatter plots, a call rate >90%, a minor allele frequency >0.001 and Hardy-Weinberg proportion test p-value in controls >0.001 for inclusion. For the AIMs, we removed AIMs with low call rates (<90%), low minor allele frequencies (<0.001), and that are in LD with each other (r2>0.2). We did not perform the Hardy-Weinberg proportion test for the AIM QC to avoid AIMs being inadvertently dropped due to monomophic states in one of the ethnic groups. Principal components 27 calculated using R and global ancestry estimated using ADMIXMAP 28, 29 (with ancestral allele frequencies from African, European, American, Indian, and East Asian population) were utilized to pinpoint population outliers (Supplementary Figure 1) and to adjust the logistic regression models for controlling population structure in our association analyses. A total of 1,135 samples were removed because they were duplicates (the proportion of alleles shared identity by descent (IBD) >0.4), sample heterozygosity outliers (>5 standard deviation from the mean), population outliers, low call rate (<90%), or gender discrepancies between reported gender and genetic data (Supplementary Table 3). The final dataset, following quality control exclusions comprised 55 SNPs and 262 AIMs and 15,864 samples (Table 1).

Association Analyses

Single marker association analyses were calculated using the logistic regression function in PLINK v1.07 30 under the additive model adjusting for gender and global ancestry estimates (African, European, and East Asian). Meta-analyses to combine p-values from different populations were performed using a weighted Z-score METAL 31. We used both the Cochran's Q test statistic and I2 index to test for heterogeneity in the meta-analysis. The Cochran’s Q test calculates the weighted sum of the squared deviations between individual study effects and the overall effect across studies 32 whereas the I2 index measures the degree or percentage of inconsistency across studies due to heterogeneity rather than by chance 33. LD between variants was estimated and probable haplotypes were calculated using Haploview 4.2 34 followed by haplotypic association for all haplotypes formed by the associated markers across the various populations. Constructing haplotypes using all variants yielded the same haplotypes as the analysis using only the associated SNPs (results not shown).

Imputation

IMPUTE2 software 35 was used to impute SNPs from 20.21 Mb to 20.34 Mb on chromosome 22 with genotype data as the source of observed genotypes and the 1000 Genomes Project from Phase I interim release (June 2011) for 1,094 individuals from Africa, Asia, Europe, and the Americas (Supplementary Table 6) as reference genotypes. Imputation using the sequence data from our European-ancestry samples along with the 1000 Genome Project haplotypes was also performed. IMPUTE2 calculates posterior probabilities for the three possible genotypes (i.e. AA, AB, and BB). These probabilities were converted to the most possible genotypes with a threshold of 0.8. Imputed SNPs with the information measure less than 0.4 were excluded.

Resequencing, Variant Detection and Quality Control

We resequenced 74 SLE cases and 100 controls of European-ancestry then included the sequenced haplotypes into the genotype imputation. For each sample 3–5 ug of whole genomic DNA were sheared and prepared using an Illumina Paired-End Genomic DNA Sample Prep Kit. The SureSelect Target Enrichment System was used to enrich targeted regions of interest from each sample by utilizing a custom designed bait pool. Resequencing was performed on an Illumina GAIIx platform using standard procedures with minimum average fold coverage of 25X. Illumina Pipeline software v.1.7 was the used to process post sequence data.

Duplicate reads were excluded using a custom script followed by alignment to the human reference genome build hg18 using BWA alignment software version 0.5.9 36. Realignment of reads around insertion/deletion sites and problematic areas, base quality score recalibration, and variation detection were processed using the Genome Analysis Tool Kit (GATK) software suite version 1.0 37, 38. Variants clustered within 10 base pairs were filtered out, as well as any variant with a quality score less than 30, a quality by depth score less than 5, inclusion within a homopolymer run of 5 or more bases, or a strand bias score of greater than −0.1. The program Beagle version 3.3 39 was utilized to determine variant phase. PLINK and IMPUTE2 format files were created using the vcftools software suite version 0.1.3 40.

In order to assess the quality of the sequence data, the sequence-based variant calls were compared with common SNPs previously genotyped with the Illumina iSelect platform. More than 99% concordance was observed suggesting high quality of our sequence data. Samples with more than 5% of variants inconsistent with genotype calls required a manual inspection of the assembled contig sequence to determine the sequence quality using the Integrative Genomics Viewer (IGV) program 41. The assembled contig sequence of each novel variant identified by our sequencing was also inspected using IGV.

Cell Culture

EBV-transformed B cell lines were requested from the Lupus Family Registry and Repository (LFRR) at OMRF with IRB approval. All cell lines in this study were EA samples and were stratified by rs7444 genotype, which is a proxy of the UBE2L3 risk haplotype. Cell lines are either homozygous (carry two copies) of non-risk haplotype, heterozygous (one copy of the risk haplotype and one copy of non risk haplotype), or homozygous (carry two copies) of risk haplotype. Cell lines were cultured in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, penicillin, streptomycin, L-glutamine, and 55µM beta-mercaptoethanol. Equal numbers of cells were harvested under basal culture condition in log-phase growth.

RNA Isolation and Quantitative RT-PCR

Total RNA was isolated using the Trizol total RNA isolation reagent (Invitrogen Inc., Carlsbad, CA). The concentrations of total RNA were determined by using nanodrop, and were diluted with 20ng/µL of MS2-RNA (Hoffmann-La Roche, Inc., Nutley NJ) to a final concentration of 0.5µg/µL. Total RNA was treated with DNase and cDNA was synthesized using the iScript cDNA Synthesis Kits purchased from Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc., Hercules, CA. Quantitative PCR was carried out using the SYBR Green method to determine the mRNA expression of UBE2L3. A pair of primers was designed and synthesized: sense, 5'-TTAGTGCCGAAAACTGGAAGC-3'; anti-sense, 5'-ATTCACCAGTGCTATGAGGGAC-3'. The PCR product corresponds to 346bp-416bp of UBE2L3 mRNA. Human HMBS gene was used in quantitative RT-PCR as a reference. The RT2 qPCR Primer Assay-SYBR Green Human HMBS Kit was purchased from SABiosciences Inc., Frederick, MD. mRNA expression of UBE2L3 was normalized to HMBS.

UBE2L3 Protein Expression

EBV-transformed B cells were harvested and lysed in Whole Cell Extraction Buffer (25mM Tris, 1% Triton X-100, 150mM NaCl, 1mM EDTA and protease inhibitors). Concentrations of protein in each cell line were determined using Quick Start Bradford Protein Assay Kits and were adjusted to a final protein concentration of 2mg/mL. Anti-UBE2L3 and Anti-GAPDH antibodies were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology, Inc., Danvers, MA, and were used to detect protein expression of UBCH7 and GAPDH, respectively. ECL Plus Western Blotting Detection System was purchased from GE Heathcare, Inc., Amersham, UK. The intensity of each band was analyzed using Image J (NIH) software. Protein expression of UBCH7 was normalized to GAPDH.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We would like to thank all individuals including the SLE patients and the controls that participated in this study. We are grateful to the research assistants, coordinators and physicians that helped in the recruitment of participants. We would like to express our gratitude the following individuals for contributing samples genotyped in this study: S. D'Alfonso (Italy), R. Scorza (Italy), P. Junker and H. Laustrup (Denmark), M. Bijl (Holland), E. Endreffy (Hungary), C. Vasconcelos and B.M. da Silva (Portugal), A. Suarez and C. Gutierrez (Spain), I. Rúa-Figueroa (Spain) and C. Garcilazo (Argentina). For the Asociación Andaluza de Enfermedades Autoimmunes (AADEA) collaboration: N. Ortego-Centeno (Spain), J. Jimenez-Alonso (Spain), E. de Ramon (Spain) and J. Sanchez-Roman (Spain). For the collaboration on Hispanic populations enriched for Amerindian-European admixture: M. Cardiel (Mexico), I.G. de la Torre (Mexico), M. Maradiaga (Mexico), J.F. Moctezuma (Mexico), E. Acevedo (Peru), C. Castel and M. Busajm (Argentina), and J. Musuruana (Argentina). Other participants from the Argentine Collaborative Group are: H.R. Scherbarth, P.C. Marino, E.L. Motta, S. Gamron, C. Drenkard, E. Menso, A. Allievi, G.A. Tate, J.L. Presas, S.A. Palatnik, M. Abdala, M. Bearzotti, A. Alvarellos, F. Caeiro, A. Bertoli, S. Paira, S. Roverano, C.E. Graf, E. Bertero, C. Guillerón, S. Grimaudo, J. Manni, L.J. Catoggio, E.R. Soriano, C.D. Santos, C. Prigione, F.A. Ramos, S.M. Navarro, G.A. Berbotto, M. Jorfen, E.J. Romero, M.A. Garcia, J.C. Marcos, A.I. Marcos, C.E. Perandones, A. Eimon and C.G. Battagliotti.

We would like to thank P.S. Ramos and S. Frank for their assistance in genotyping, quality control analyses and clinical data management and the staff of the Lupus Family Registry and Repository (LFRR) for collecting and maintaining SLE samples. Support for this work was obtained from the US National Institutes of Health grants: R01 AI063274, R01 AR056360, P20 GM103456 (P.M.G.); R01 AR043274 (K.L.M.); N01 AR62277 (K.L.M. and J.B.H.); R37 24717, R01 AR042460, P01 AI083194, R01 DE018209 (J.B.H.); P01 AR49084 (R.P.K., J.C.E. and E.E.B); 5UL1 RR025777 (J.C.E.); R01 AR33062 (R.P.K.); P30 AR48311 (E.E.B); K08 AI083790, LRP AI071651, UL1 RR024999 (T.B.N.); R01 CA141700, RC1 AR058621 (M.E.A.R.); R01 AR051545-01A2, ULI RR025014-02 (A.M.S.); U19 AI082714, RC1 AR058554, P30 RR031152, P30 AR053483, N01 AI50026 (J.A.J. and J.M.G.); R21 AI070304 (S.A.B.); R01 AR43814 (B.P.T.); P60 AR053308, M01 RR-00079 (L.A.C.); R01 AR043727, UL1 RR025005 (M.A.P.), K24 AR002138, P60 2 AR30692, P01 AR49084, UL1 RR025741 (R.R.G.), 1U54 RR23417-01 (J.D.R.), R01 AR043727, UL1 RR025005 (M.A.P.), P60 AR049459 and UL1 RR029882 (D.L.K.). Additional support was obtained from the Alliance for Lupus Research (K.L.M.); Merit Award from the US Department of Veterans Affairs (J.B.H. and G.S.G.); the Swedish Research Council for Medicine, Gustaf Vth-80th Jubilee Fund and Swedish Association Against Rheumatism, Instituto de Salud Carlos III, Oklahoma Center for Advancement of Science and Technology (OCAST) HR09-106 (M.E.A.R.); the European Science Foundation funds the BIOLUPUS network (M.E.A.R. coordinator); the Barrett Scholarship Fund Oklahoma Medical Research Foundation (OMRF) (C.J.L.); the Korea Healthcare Technology Research and Development Project, Ministry for Health and Welfare, Republic of Korea (A111218-11-GM01, S.C.B.); Lupus Research Institute (T.B.N.); The Alliance for Lupus Research (T.B.N., L.A.C. and C.O.J.); the Arthritis National Research Foundation Eng Tan Scholar Award (T.B.N.); Arthritis Foundation (P.M.G. and A.M.S.); the Lupus Foundation of Minnesota (P.M.G. and K.L.M.); the Wellcome Trust (T.J.V.); Arthritis Research UK (T.J.V.); Kirkland Scholar Award (L.A.C.); Wake Forest University Health Sciences Center for Public Health Genomics (C.D.L.); and the Federico Wilhelm Agricola Foundation Research grant (B.A.P.E.) . The work reported on in this publication has been in part financially supported by the ESF, in the framework of the Research Networking Programme European Science Foundation - The Identification of Novel Genes and Biomarkers for Systemic Lupus Erythematosus (BIOLUPUS)” 07-RNP-083.

Footnotes

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

P.M.G., C.G.M., K.L.M., C.J.L., J.A.K., K.M.K., C.D.L., and J.B.H. selected SNPs and were responsible for the study design. J.M.G., M.E.A.R., G.S.A., J.M.A., S.C.B., S.A.B., E.E.B., M.A.P., R.R.G., J.D.R., L.M.V., L.A.C., J.C.E., B.I.F., G.S.G., C.O.J., J.A.J., D.L.K., R.P.K., J.M., J.T.M., T.B.N., B.A.P.E., A.M.S., B.P.T., L.M.V., T.J.V., J.B.H., K.L.M., and P.M.G. assisted in the collection and characterization of the SLE cases and controls. A.A., K.M.K. and P.M.G. performed the genotyping. S.B.G., A.W., J.Z., M.E.C., M.M., J.A.K., K.M.K. and C.D.L. performed genotyping quality control. I.A., S.W., G.W., C.J.L., C.G.M. and P.M.G. performed association analyses and imputation. G.W., B.E.W., C.L., E.K.W., S.W. and P.M.G. performed sequencing. G.W., I.A., S.W., C.J.L., S.B.G., C.G.M. and P.M.G. performed sequencing data analysis. S.W. and P.M.G. performed functional studies. S.W., I.A., G.W., C.G.M., and P.M.G. prepared the manuscript and all authors approved the final draft.

COMPETING FINANCIAL INTERESTS

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Kozyrev SV, Abelson AK, Wojcik J, Zaghlool A, Linga Reddy MV, Sanchez E, et al. Functional variants in the B-cell gene BANK1 are associated with systemic lupus erythematosus. Nat Genet. 2008;40(2):211–216. doi: 10.1038/ng.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gateva V, Sandling JK, Hom G, Taylor KE, Chung SA, Sun X, et al. A large-scale replication study identifies TNIP1, PRDM1, JAZF1, UHRF1BP1 and IL10 as risk loci for systemic lupus erythematosus. Nat Genet. 2009;41(11):1228–1233. doi: 10.1038/ng.468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Han JW, Zheng HF, Cui Y, Sun LD, Ye DQ, Hu Z, et al. Genome-wide association study in a Chinese Han population identifies nine new susceptibility loci for systemic lupus erythematosus. Nat Genet. 2009;41(11):1234–1237. doi: 10.1038/ng.472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Harley JB, Alarcon-Riquelme ME, Criswell LA, Jacob CO, Kimberly RP, Moser KL, et al. Genome-wide association scan in women with systemic lupus erythematosus identifies susceptibility variants in ITGAM, PXK, KIAA1542 and other loci. Nat Genet. 2008;40(2):204–210. doi: 10.1038/ng.81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hom G, Graham RR, Modrek B, Taylor KE, Ortmann W, Garnier S, et al. Association of systemic lupus erythematosus with C8orf13-BLK and ITGAM-ITGAX. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(9):900–909. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0707865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Deng Y, Tsao BP. Genetic susceptibility to systemic lupus erythematosus in the genomic era. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2010;6(12):683–692. doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2010.176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Graham RR, Cotsapas C, Davies L, Hackett R, Lessard CJ, Leon JM, et al. Genetic variants near TNFAIP3 on 6q23 are associated with systemic lupus erythematosus. Nat Genet. 2008;40(9):1059–1061. doi: 10.1038/ng.200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Adrianto I, Wen F, Templeton A, Wiley G, King JB, Lessard CJ, et al. Association of a functional variant downstream of TNFAIP3 with systemic lupus erythematosus. Nat Genet. 2011;43(3):253–258. doi: 10.1038/ng.766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Orozco G, Eyre S, Hinks A, Bowes J, Morgan AW, Wilson AG, et al. Study of the common genetic background for rheumatoid arthritis and systemic lupus erythematosus. Annals of the rheumatic diseases. 2011;70(3):463–468. doi: 10.1136/ard.2010.137174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Agik S, Franek BS, Kumar AA, Kumabe M, Utset TO, Mikolaitis RA, et al. The autoimmune disease risk allele of UBE2L3 in African American patients with systemic lupus erythematosus: a recessive effect upon subphenotypes. J Rheumatol. 2012;39(1):73–78. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.110590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chung SA, Taylor KE, Graham RR, Nititham J, Lee AT, Ortmann WA, et al. Differential genetic associations for systemic lupus erythematosus based on anti-dsDNA autoantibody production. PLoS genetics. 2011;7(3):e1001323. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1001323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Franke A, McGovern DP, Barrett JC, Wang K, Radford-Smith GL, Ahmad T, et al. Genome-wide meta-analysis increases to 71 the number of confirmed Crohn's disease susceptibility loci. Nature genetics. 2010;42(12):1118–1125. doi: 10.1038/ng.717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fransen K, Visschedijk MC, van Sommeren S, Fu JY, Franke L, Festen EA, et al. Analysis of SNPs with an effect on gene expression identifies UBE2L3 and BCL3 as potential new risk genes for Crohn's disease. Hum Mol Genet. 2010;19(17):3482–3488. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddq264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhernakova A, Stahl EA, Trynka G, Raychaudhuri S, Festen EA, Franke L, et al. Meta-analysis of genome-wide association studies in celiac disease and rheumatoid arthritis identifies fourteen non-HLA shared loci. PLoS genetics. 2011;7(2):e1002004. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ciechanover A. The ubiquitin-proteasome pathway: on protein death and cell life. The EMBO journal. 1998;17(24):7151–7160. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.24.7151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ciechanover A, Shkedy D, Oren M, Bercovich B. Degradation of the tumor suppressor protein p53 by the ubiquitin-mediated proteolytic system requires a novel species of ubiquitin-carrier protein, E2. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1994;269(13):9582–9589. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moynihan TP, Ardley HC, Leek JP, Thompson J, Brindle NS, Markham AF, et al. Characterization of a human ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme gene UBE2L3. Mamm Genome. 1996;7(7):520–525. doi: 10.1007/s003359900155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Orian A, Whiteside S, Israel A, Stancovski I, Schwartz AL, Ciechanover A. Ubiquitin-mediated processing of NF-kappa B transcriptional activator precursor p105. Reconstitution of a cell-free system and identification of the ubiquitin-carrier protein, E2, and a novel ubiquitin-protein ligase, E3, involved in conjugation. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1995;270(37):21707–21714. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.37.21707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Whitcomb EA, Taylor A. Ubiquitin control of S phase: a new role for the ubiquitin conjugating enzyme, UbcH7. Cell Div. 2009;4:17. doi: 10.1186/1747-1028-4-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wertz IE, Dixit VM. Signaling to NF-kappaB: regulation by ubiquitination. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2010;2(3):a003350. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a003350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hayden MS, Ghosh S. Shared principles in NF-kappaB signaling. Cell. 2008;132(3):344–362. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Raimondo D, Giorgetti A, Bernassola F, Melino G, Tramontano A. Modelling and molecular dynamics of the interaction between the E3 ubiquitin ligase Itch and the E2 UbcH7. Biochem Pharmacol. 2008;76(11):1620–1627. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2008.08.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rossi M, De Laurenzi V, Munarriz E, Green DR, Liu YC, Vousden KH, et al. The ubiquitin-protein ligase Itch regulates p73 stability. The EMBO journal. 2005;24(4):836–848. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Markson G, Kiel C, Hyde R, Brown S, Charalabous P, Bremm A, et al. Analysis of the human E2 ubiquitin conjugating enzyme protein interaction network. Genome research. 2009;19(10):1905–1911. doi: 10.1101/gr.093963.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Smith MW, Patterson N, Lautenberger JA, Truelove AL, McDonald GJ, Waliszewska A, et al. A high-density admixture map for disease gene discovery in african americans. Am J Hum Genet. 2004;74(5):1001–1013. doi: 10.1086/420856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Halder I, Shriver M, Thomas M, Fernandez JR, Frudakis T. A panel of ancestry informative markers for estimating individual biogeographical ancestry and admixture from four continents: utility and applications. Hum Mutat. 2008;29(5):648–658. doi: 10.1002/humu.20695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Price AL, Patterson NJ, Plenge RM, Weinblatt ME, Shadick NA, Reich D. Principal components analysis corrects for stratification in genome-wide association studies. Nat.Genet. 2006;38(8):904–909. doi: 10.1038/ng1847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hoggart CJ, Parra EJ, Shriver MD, Bonilla C, Kittles RA, Clayton DG, et al. Control of confounding of genetic associations in stratified populations. Am J Hum Genet. 2003;72(6):1492–1504. doi: 10.1086/375613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hoggart CJ, Shriver MD, Kittles RA, Clayton DG, McKeigue PM. Design and analysis of admixture mapping studies. Am J Hum Genet. 2004;74(5):965–978. doi: 10.1086/420855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Purcell S, Neale B, Todd-Brown K, Thomas L, Ferreira MA, Bender D, et al. PLINK: a tool set for whole-genome association and population-based linkage analyses. Am J Hum Genet. 2007;81(3):559–575. doi: 10.1086/519795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Willer CJ, Li Y, Abecasis GR. METAL: fast and efficient meta-analysis of genomewide association scans. Bioinformatics. 2010;26(17):2190–2191. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cochran WG. The Combination of Estimates from Different Experiments. Biometrics. 1954;10(1):101–129. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327(7414):557–560. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Barrett JC, Fry B, Maller J, Daly MJ. Haploview: analysis and visualization of LD and haplotype maps. Bioinformatics. 2005;21(2):263–265. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bth457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Howie BN, Donnelly P, Marchini J. A flexible and accurate genotype imputation method for the next generation of genome-wide association studies. PLoS Genet. 2009;5(6):e1000529. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Li H, Durbin R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics. 2009;25(14):1754–1760. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.McKenna A, Hanna M, Banks E, Sivachenko A, Cibulskis K, Kernytsky A, et al. The Genome Analysis Toolkit: a MapReduce framework for analyzing next-generation DNA sequencing data. Genome Res. 2010;20(9):1297–1303. doi: 10.1101/gr.107524.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.DePristo MA, Banks E, Poplin R, Garimella KV, Maguire JR, Hartl C, et al. A framework for variation discovery and genotyping using next-generation DNA sequencing data. Nat Genet. 2011;43(5):491–498. doi: 10.1038/ng.806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Browning SR, Browning BL. Rapid and accurate haplotype phasing and missing-data inference for whole-genome association studies by use of localized haplotype clustering. Am J Hum Genet. 2007;81(5):1084–1097. doi: 10.1086/521987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Danecek P, Auton A, Abecasis G, Albers CA, Banks E, DePristo MA, et al. The variant call format and VCFtools. Bioinformatics. 2011;27(15):2156–2158. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Robinson JT, Thorvaldsdottir H, Winckler W, Guttman M, Lander ES, Getz G, et al. Integrative genomics viewer. Nature biotechnology. 2011;29(1):24–26. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.