Abstract

A substantial portion of the world's people have not made adequate progress toward overcoming hunger or achieving sustainable livelihoods. The classic approach to addressing chronic food insecurity has been a strategy of agricultural development, supplemented by humanitarian assistance in the event of a shock or crisis—an approach predicated on assumptions that do not fit the context of protracted crises. This article describes protracted crises and argues that they are sufficiently different to warrant special consideration, but there are unique constraints to engagement in protracted crises. The article explores the constraints promoting sustainable livelihoods in these contexts and proposes elements of an alternative approach. It evaluates the limited evidence available about such an approach and outlines important questions for further research.

Keywords: food security, chronic vulnerability, humanitarian response, transition

Context of Protracted Crises

A substantial portion of the world's poorest people have not made adequate progress toward overcoming hunger or achieving sustainable livelihoods. The classic approach to addressing chronic food insecurity has been a strategy of agricultural development to improve food availability and rural livelihoods, and humanitarian assistance in the event of sporadic shocks (1). Achieving sustainable livelihoods through improving smallholder production—the general theme of this edition—is a complex task in relatively stable countries that do not suffer recurrent crises. Protracted crises present special constraints that require new scientific thinking and a different approach from current models—and are often omitted from the current debate and efforts addressing hunger. This article describes protracted crises and argues that they are sufficiently different to warrant special consideration. It analyzes these constraints and explores attempts to promote sustainable livelihoods in these contexts. Finally, it suggests elements of an alternative approach and outlines several questions for further research.

Macrae and Harmer define protracted crises as “those environments in which a significant proportion of the population is acutely vulnerable to death, disease, and disruption of their livelihoods over a prolonged period of time” (ref. 2, p. 1). Once perhaps called “chronically vulnerable areas” (3), protracted crises are heterogeneous but are nevertheless defined by several characteristics. First, protracted crises are defined by both time duration and magnitude. Many have lasted 30 years or more and are characterized by extreme levels of food insecurity. Second, few protracted crises are traceable to a single, acute shock. Conflict is often one cause, but climatic, environmental, or economic factors may also be causes. Unsustainable livelihoods are both a consequence and cause of protracted crises (4). Third, intervention mechanisms are often weak. Development donors are often not willing to make significant investments in protracted crisis contexts, and private-sector engagement in protracted crises is often lacking or dominated by informal or illegal economic activities that extract wealth but do little to invest in sustainable improvements (5). Hence, market-led or technology-driven development is extremely difficult to sustain in protracted crises. Fourth, protracted crises remain on the humanitarian agenda in part because of poor food security or nutritional outcomes, and in part because humanitarian agencies are often the only available vehicle for intervention under the prevailing architecture of international assistance. Finally, protracted crises often occur in contexts in which states are incapable or unwilling to provide basic services or infrastructure, or are downright predatory toward the population. In short, protracted crises—and populations caught in them—fall between standard categories of intervention and are often forgotten.

The United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization used three criteria to identify countries in protracted crisis: first, the number of years in crisis, i.e., countries reporting a crisis requiring external assistance in at least 8 of the past 10 years (4); second, composition of external assistance, i.e., countries receiving 10% or more of official development assistance as humanitarian aid since 2000 (4); and third, basic economic and food security information, i.e., only low-income, food deficit countries were included (6). These criteria define the countries in Table 1.

Table 1.

Indicators of countries in protracted crisis: Food security, years in crisis, aid flows, stability, poverty, and agricultural growth

| Country | Population in millions (4) | Undernourished, millions (4) | Undernourished, % (4) | Global Hunger Index (7) | Years in crisis (4) | Humanitarian aid, % (4) | Political stability, percentile (8) | Human Development Index (9)† | Growth in average yield (10)‡ |

| Year | 2007 | 2005–07 | 2005–07 | 2009 | 1996–2010 | 2000–2008 | 2008 | 2009 | 1990–2005 |

| Afghanistan | NA | NA | NA | NA | 15 | 20 | 1 | 0.352 | NA |

| Angola | 17.1 | 7.1 | 41 | 25.3 | 12 | 30 | 30 | 0.564 | 5 |

| Burundi | 7.6 | 4.7 | 62 | 38.7 | 15 | 32 | 10 | 0.394 | 115 |

| CA Republic | 4.2 | 1.7 | 40 | 28.1 | 8 | 13 | 7 | 0.369 | 56 |

| Chad | 10.3 | 3.8 | 37 | 31.3 | 9 | 23 | 4 | 0.392 | 70 |

| Congo | 3.5 | 0.5 | 15 | 15.4 | 13 | 22 | 25 | 0.601 | 78 |

| Côte d'Ivoire | 19.7 | 2.8 | 14 | 14.5 | 9 | 15 | 5 | 0.484 | 4 |

| DPR Korea | 23.6 | 7.8 | 33 | 18.4 | 15 | 47 | 58 | NA | NA |

| DR Congo | 60.8 | 41.9 | 69 | 39.1 | 15 | 27 | 2 | 0.389 | 108 |

| Eritrea | 4.6 | 3.0 | 64 | 36.5 | 15 | 30 | 20 | 0.472 | 126 |

| Ethiopia | 76.6 | 31.6 | 41 | 30.8 | 15 | 21 | 6 | 0.414 | 77 |

| Guinea | 9.4 | 1.6 | 17 | 18.2 | 10 | 16 | 5 | 0.435 | 27 |

| Haiti | 9.6 | 5.5 | 57 | 28.2 | 15 | 11 | 11 | 0.532 | 122 |

| Iraq | NA | NA | NA | NA | 15 | 14 | 0 | NA | NA |

| Kenya | 36.8 | 11.2 | 31 | 20.2 | 12 | 14 | 12 | 0.541 | 111 |

| Liberia | 3.5 | 1.2 | 33 | 24.6 | 15 | 33 | 17 | 0.442 | NA |

| Sierra Leone | 5.3 | 1.8 | 35 | 33.8 | 15 | 19 | 35 | 0.365 | 110 |

| Somalia | NA | NA | NA | NA | 15 | 64 | 0 | NA | NA |

| Sudan | 39.6 | 8.8 | 22 | 19.6 | 15 | 62 | 2 | 0.531 | 81 |

| Tajikistan | 6.6 | 2.0 | 30 | 18.5 | 11 | 13 | 21 | 0.688 | 3 |

| Uganda | 29.7 | 6.1 | 21 | 14.8 | 14 | 10 | 19 | 0.514 | 95 |

| Zimbabwe | 12.5 | 3.7 | 30 | 21.0 | 10 | 31 | 9 | NA | 125 |

Reprinted with permission from the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. DPR, Democratic People's Republic; DR, Democratic Republic; NA, not available.

* Percentile score: Lowest means least stable.

†0 represents lowest; 1 represents highest.

‡Rank (against 126 other countries).

Several points should be noted about Table 1. First, protracted crises are rarely defined by national boundaries, but available data offer no better units of analysis for comparison. Elements of protracted crisis occur in countries not included in Table 1 (Niger, Sri Lanka, Timor-Leste) and, in some of countries listed, protracted crisis occurs only in some parts of the country (Kenya, Uganda, Ethiopia). Second, all have multiple causes to explain protracted crises: all countries listed have experienced human-made elements of crisis (usually conflict) and nearly all have suffered a natural disaster; most of the countries on the list have had both at the same time in recent years. Third, most protracted crises fall within “fragile” states. Countries in Table 1 are ranked low for political stability (8) and all are considered “fragile” or “failed” states (11). Fourth, all the countries in Table 1 have poor food security outcomes: the prevalence of undernourishment in the population ranges from a low of 14% to a high of 69% (4). For the most extreme cases of protracted crisis—Somalia, North Korea, Afghanistan—food security statistics are not even available, underlining the difficulty of research in these contexts. Fifth, only a small handful of countries in protracted crisis are ranked as high performers in agricultural growth during the past two decades. Agriculture accounts for 32% of gross domestic product in these countries, and is the livelihood of nearly two thirds of the population, yet receives less than 4% of external assistance funding received by these countries (4). The nature of crisis itself has become increasingly protracted. Two decades ago, many fewer countries would have fit these criteria. In 2010, short, acute crises are the exception, not the rule.

The impact of protracted crises is not a small problem or an outlier. The combined population of these countries is approximately 450 million, of whom approximately 160 million were undernourished in 2005 to 2007 (including conservative estimates for countries lacking data): approximately one sixth of the global total of food-insecure people, or approximately one third of the total if India and China are factored out. Nor is it simply the case that these populations are a little worse off. The mean prevalence of undernourishment in protracted crisis countries is 37%, compared with 15% in China and India combined, and 13% on average in the rest of the developing world (4). Multivariate analysis indicates that, in addition to income, education, and governance, the greater the number of years in crisis, the worse the food security outcome (Table 2).

Table 2.

Regression analysis: Food insecurity, poverty, governance, and protracted crises (4)

| Dependent variable: Undernourishment, % |

Dependent variable: Global Hunger Index |

|||

| Factor | Elasticity | Z (sig) | Elasticity | Z (sig) |

| Income | −0.76 | −2.85* | −0.72 | −4.58* |

| Education | 0.32 | 1.21 | −0.36 | −2.36† |

| Government effectiveness | −1.45 | −3.63* | −0.65 | −2.84* |

| Control of corruption | 1.05 | 2.79* | 0.48 | 2.14† |

| Years in crisis | 0.38 | 4.29* | 0.16 | 3.14* |

| Adjusted R2 (OLS) | — | 0.52* | — | 0.72* |

Source: Food and Agriculture Organization (4), p. 16. OLS, ordinary least squares.

*P < 0.01,

†P < 0.05.

Two points are important: the first is the overlap of a high prevalence of food insecurity, state fragility, poor agricultural performance, and the “protractedness” of crisis. The second is that, despite their significantly worse food security status, most of these countries are left out of major new global initiatives to address hunger. For example, of 22 countries targeted by the Obama administration's Feed the Future program, only six appear in Table 1 (12), and it is by no means clear that, even in these countries, protracted crisis areas are included. In these crises, a different approach to sustainable livelihoods is called for. However, many factors constrain such an approach; these are analyzed in the next section.

Limitations to Engaging in Protracted Crises

There are conceptual limitations and institutional constraints to working in protracted crises, limited growth potential from private sector investment, various constraints to public-sector or international programmatic interventions, and no consensus on operating principles or priorities.

Conceptual Limitations.

Conceptual limitations take several forms. First, there is a normative assumption that social change consists of steady improvement over time. Acute disasters may represent an occasional downward blip, but with “recovery,” the trajectory returns to one of improvement. These assumptions shape the way external intervention is organized. However, the observed reality is that, for the majority of populations in protracted crisis, the trajectory is erratic and often worsens over time (13). Second, disaster risk management programs have improved in recent years, but the focus is still mostly on covariate risk (risk that affects large proportions of the populations at once). Idiosyncratic risk (local or household-level hazards) is equally likely to constrain livelihoods (14). Preparing for and mitigating the impact of covariate risk almost by definition requires a functioning local government—a consideration often not met in protracted crises. Customary institutions may have been systematically undermined by protracted crisis, undermining resilience to both covariate and idiosyncratic risk. Also, risk management approaches have mostly not yet addressed conflict or political risk more generally. Rights-based approaches have begun to address this, but are not widely mainstreamed (15).

Institutional Constraints.

External institutional factors constraining livelihood change in protracted crises include the bifurcation of donor funding. Most donors have a funding window for “development” and another for “humanitarian” or “emergency” response (16). Activities such as livelihood protection or rehabilitation are often split between the two and are traditionally quite underfunded. “Reconstruction and rehabilitation” did not appear as an entry in official aid figures until 2004 (17). A recent study found three other significant funding issues (18). First, most funding for “transitions” is for short-term interventions only, despite the protracted nature of the task. Second, funding for transitions is substantially less than for either humanitarian or development programs. Third, “development” tends to be underfunded in protracted crises, resulting in the predominance of humanitarian assistance or no assistance at all (18).

Internal institutional constraints to livelihoods tend to be more location-specific, but include land and natural resource tenure, markets and infrastructure, and gender and social relations (19, 20). Where resource conflict is an issue, reform of tenure institutions and access is critical to the resolution of conflict, but the breakdown in governance, both formal and customary, is an impediment to resolving institutional constraints (21). On the contrary, where markets function well—such as in Somalia—market interventions can provide powerful incentives to increase production (4). However, poor infrastructure, weak institutions, and conflict all heighten the risks to private-sector investment, and often present a serious challenge to value chain interventions. Until these risks are reduced, it is unlikely that private sector-led development will be a driving force for sustainable growth in protracted crises (22). However, as already noted, risk management is to some extent dependent on functioning local administration. The power relations that underpin local institutions, including gender relations, lead to the “capture” of resources—both local and external—underlining the need for good stakeholder and political analysis as a part of intervention (23). Local civil society may expand and fulfill some of the roles of fragile states, but may be undermined or deliberately targeted in conflict (19).

Programming Constraints.

Several programming constraints limit external interventions: one is the limitation of the dominant programmatic framework; another includes practical elements of program management; a third is normative.

At one point in time, the “relief-to-development continuum” was accepted as both an analytical and a programming framework in crisis-prone contexts (24). It has been largely dropped as an analytical tool, but often remains the programmatic framework, albeit in somewhat altered forms. A variety of approaches have been suggested in the absence of an accepted programmatic framework. These include:

i) The “twin track” approach. The United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization suggests a twin track programmatic framework for promoting livelihoods sustainability in protracted crises, embracing both humanitarian interventions and livelihoods improvements in the same contexts at the same time, depending on needs (19). This is done through identifying local institutions and external actors that bring about lasting change in the absence of effective state structures (22).

ii) Linking relief, rehabilitation, and development. Promoted by the European Commission, this approach emphasizes the contiguous interaction of relief and development actors, rather than presuming a continuum that suggests normative movement in one direction (25).

iii) Early recovery. Promoted by the United Nations Development Program, early recovery is “a multidimensional process of recovery that begins in a humanitarian setting,” but “is guided by development principles that seek to build on humanitarian programmes and catalyze sustainable development opportunities” (ref. 26, p. 6). It has been described as a shared space between humanitarian and development actors to build the foundation for recovery and (perhaps more significantly) to reduce humanitarian assistance after a crisis.

iv) Developmental relief. Promoted by US donor agencies, this approach deliberately attempts to use humanitarian resources (most notably food aid) for developmental purposes. Described as an attempt to “integrate emergency and development programming and build community resilience to recurrent shocks” (ref. 27, p. 1), it tends to be restricted to natural disaster response.

All these approaches still tend to bifurcate programmatic responses into “relief” and “development” categories, and conflate “relief” with a short-term emphasis on addressing symptoms and “development” with a long-term emphasis on addressing causes. Also, all these approaches—although they note the need for a diversified strategy—do little in themselves to address other major programming constraints, including the limited ability to attract high-quality staff and high staff turnover, limited ability to conduct good analysis or monitoring, and, therefore, limited learning capacity.

There is no consensus on operating principles in protracted crises. Humanitarian agencies—often called upon to intervene—have a clearly defined, although contested, set of principles to protect life, enable access, and ensure fairness in acute emergencies and conflict. However, these principles are not intended to promote economic recovery, growth, or transformation. Central to humanitarian principles is the necessity to operate independently of belligerents in conflicts, including states. Developmental principles are less clearly defined, but are evident in, for example, the Paris Declaration on Aid Effectiveness (28), which emphasizes national ownership of development processes; alignment of external resources to national priorities; and effectiveness, accountability, transparency, and predictability. Other developmental principles would certainly include sustainability, empowerment, self-reliance, sex equity, and participation (3). All these necessarily presume some degree of a functioning state and local administration.

An Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development effort attempted to develop a set of “Principles for Good International Engagement in Fragile States” (29), reflecting a consensus among governments that fragile states require different responses. These principles emphasize the importance of context, ensuring that external interventions “do no harm.” They focus on state building as the central objective (overriding both humanitarian and developmental principles) and embrace the links among humanitarian political, security, and development objectives. Principles can probably be agreed by all stakeholders in clear postcrisis situations in which states are willing actors, but simply lack capacity. Humanitarian principles apply in acute conflict situations, but they remain problematic in low-grade conflict or situations in which economic growth, institution building, and stabilization objectives accompany humanitarian objectives—the situation pertaining to most protracted crises.

Adaptations for Engaging in Protracted Crises

Programming Framework.

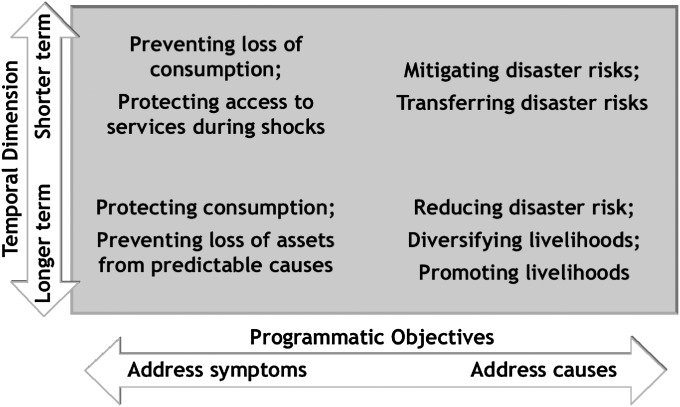

Fig. 1 outlines a different approach to programming analysis, separating the temporal dimension from the objectives of intervention—thus addressing the most obvious shortcoming of all of the other programming frameworks described earlier (30). This approach includes the provision of longer-term safety net support into the program framework, rather than seeing it as a standalone category as implied in relief-to-development frameworks. Mitigating and reducing risk adds significant scope to classic income and asset accumulation objectives in dealing with underlying causes of food insecurity. There has been more discussion of “mainstreaming” notions of risk reduction into both development and humanitarian programming since the introduction of the Hyogo Framework of Action (31), but so far no overarching programming framework has incorporated it. The key point arising from the framework in Fig. 1 is to link programming objectives, time frame, and context analysis. Given its emphasis on the provision of social protection and risk reduction, the framework in Fig. 1 implicitly recognizes the role of local government and the private sector.

Fig. 1.

Situating programmatic responses to food insecurity. Reproduced with permission from Maxwell et al. (30). (Copyright 2010, Elsevier.)

Interventions.

Some progress has been made in implementing elements of programming suggested in Fig. 1. In Ethiopia, for example, the Productive Safety Net Program (PSNP) has provided at-risk populations with guaranteed access to adequate food so they will not be forced to sell assets in bad years. The “programming hypothesis” is that this will enable at-risk populations to grow out of chronic food insecurity. The PSNP has indeed blunted the impact of several bad years on human populations, but the available means of growing out of chronic food insecurity—including production technology and greater market orientation—introduced new risks and made programming more complex. Although protection of consumption and assets has been the main objective of the PSNP, risk reduction and risk transfer are increasingly being incorporated into the overall approach. However, impact assessment is only beginning to capture the combined effects of the PSNP and risk management interventions (32, 33), so it is not yet possible to make any claims about this combined approach. Combined interventions that protect consumption and assets have been shown to be very effective in shocks that are of limited duration, but protecting assets in protracted crises remains a challenge. Risk transfer interventions, such as rainfall index insurance, have proven feasible on a small scale, but new risks have emerged—mostly financial and economic risks related to rapid price inflation or more idiosyncratic indebtedness processes (32). Much of this research has taken place in a context in which there is functioning local administration and conflict is not a significant hazard, so it addresses only some of the elements of protracted crisis.

In protracted crises more broadly, major changes have been made in the provision of food assistance—most notably the increased use of cash transfers. However, food aid remains the dominant food security response in protracted crises (34). More funding has been made available for local and regional purchase of food—offering the possibility of market-led efforts to improve smallholder incomes in countries of purchase—but in-kind donations of food aid still predominate. Tools have been developed and are being pilot-tested to guide decision-makers in the choice of cash, locally purchased food, or in-kind food aid from donors (35), meaning that a greater range of interventions can, in theory, be matched to the range of needs on the ground. These approaches have significantly reduced short-term mortality in crises, but the effects of these approaches on reducing food insecurity in the longer term constitutes another question for more in-depth research and impact assessment.

Understanding local changes and adaptations in livelihoods is crucial. Displacement and population movement are very prevalent in crises, and in protracted crises, displacement often becomes permanent as the displaced are often indistinguishable from other urban poor in cities or as temporary camps metamorphose into permanent settlements. Adaptations observed include much higher reliance on labor markets, remittances, and natural resource extraction, but often include unsustainable or “maladaptive” practices (4, 19). External support to agriculture is low in protracted crises, but a broad range of support to rural and urban livelihoods, such as cash transfers, is necessary. Reducing and managing risk is critical for private sector investment and market development if progress is to be made in getting beyond the provision of assistance or safety nets.

Local institutional innovation can be the result of protracted crisis as well: local institutions have evolved in the Democratic Republic of Congo (known as “chambre de paix”) to deal with local land conflict (19). Similar local institutions provide for social protection in the breakdown of traditional safety nets in Sierra Leone (4). Community-based approaches to the provision of animal health services have been piloted in the Horn of Africa (19). Interventions must recognize and build on these institutional innovations.

Unanswered Questions: The Research Agenda and the Need for New Thinking

Given the state of food insecurity in the context of protracted crises, external engagement is likely to continue to be critical. Although there is evidence of progress in some cases, major questions remain—calling not only for stepped-up engagement, but engagement that rigorously measures the impact of interventions. The ability to introduce interventions implied by the programming framework in Fig. 1 will require greater flexibility from donors, but assessing the impact of these interventions will require much better analytical capacity on the part of external actors. Support for local institutional innovation will be crucial if a local private sector is to play a significant role. These are major challenges, and the subject for further investigation. Another research question is the extent to which localized institutional adaptations can be generalized or scaled up.

The rationale for engagement in many protracted crises has shifted in recent years, away from hunger and toward more political and security concerns—particularly in fragile state contexts. The extent to which the rehabilitation of state and local governance takes priority over food security and livelihoods objectives in the medium term remains an open question—one which must be researched in context and with great caution. There is a clear need for greater engagement with local stakeholders including, at a minimum, local government, nonstate actors (which may be the local governing authority in protracted crises), local communities, local civil society organizations, and the private sector.

Finally, the question of the appropriate vehicle for external intervention remains very contentious. Humanitarian agencies have often been called upon, but as noted, their operating principles are not well adapted to protracted engagements, and the motivation for their engagement is often very different from those of donors. Increasingly, private contractors or civil/military partnerships are being used to engage populations in protracted crisis. Rethinking programming approaches and the modalities of intervention, and measuring the impact of interventions, are crucial to engaging in protracted crises if chronic food insecurity is to be reduced.

Methods

This article has presented an analytical review, building on major perspectives about the transformation of smallholder livelihoods. The approach has been to synthesize the characteristics of protracted crises and analyze the constraints to livelihoods transformation and food security in protracted crises. To do this, the article combines a synthesis of divergent literatures—on state fragility, humanitarian and developmental principles, and institutional constraints—with previous work on programmatic design and current assessment of programmatic impact in protracted crises. The report is not intended as a blueprint for action in protracted crises—indeed, were such a blueprint a significant operational possibility, there would be little need for further analysis. The very nature of protracted crisis calls for contextual learning and flexibility and makes operational blueprints unlikely and often distinctly not useful.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

References

- 1.Food and Agriculture Organization . How to Feed the World in 2050. Rome: FAO; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Macrae J, Harmer A. Beyond the continuum: Aid policy in protracted crises. HPG Report 18. London: Overseas Development Institute; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Maxwell D. Programmes in chronically vulnerable areas: Challenges and lessons learned. Disasters. 1999;23:373–384. doi: 10.1111/1467-7717.00126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Food and Agriculture Organization . The State of Food Insecurity in the World 2010: Addressing Food Insecurity in Protracted Crises. Rome: FAO; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Duffield M. Global Governance and the New Wars: The Merging of Development and Security. New York: Zed Books; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Food and Agriculture Organization . FAO Low-Income Food-Deficit Countries (LIFDC). List for 2010. Rome: FAO; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 7.International Food Policy Research Institute . The Challenge of Hunger 2007. Washington, DC: IFPRI; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 8.World Bank Institute . The Worldwide Governance Indicators. Washington, DC: World Bank; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 9.UN Development Program . Human Development Report 2007–2008. New York: UN Development Program; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 10.World Bank . Agriculture for Development. 2008 World Development Report. Washington, DC: International Bank for Reconstruction and Development; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 11.World Bank . Fragile States. The Fragile States List. Washington, DC: World Bank/International Development Association; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Feed the Future . Feed the Future Guide, May 2010. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Walker P. How to think about the future: history, climate change, and conflict. Prehosp Disaster Med. 2009b;24(suppl 2):s244–s246. doi: 10.1017/s1049023x0002166x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Carter M, Barrett C. The economics of poverty traps and persistent poverty: An asset-based approach. J Dev Stud. 2006;42:178–199. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sabates-Wheeler R, Devereux S. Social protection for transformation. IDS Bull. 2007;38:23–28. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Development Initiatives . Global Humanitarian Assistance 2009. Wells, UK: Development Initiatives; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development . Final ODA Flows in 2006. Paris: OECD/Development Assistance Committee; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Development Initiatives . Mapping the Transition: Financing Procedures and Mechanisms. Somerset, UK: Development Initiatives; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Alinovi L, Hemrich G, Russo L. Beyond Relief: Food Security in Protracted Crises. Rugby, UK: Practical Action Publishing; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Young H, et al. Darfur: Livelihoods Under Siege. Feinstein International Center Research Report. Medford, MA: Tufts Univ Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pantuliano S. Uncharted Territory: Land, Conflict and Humanitarian Action. Rugby, UK: Practical Action; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pingali P, Alinovi L, Sutton J. Food security in complex emergencies: enhancing food system resilience. Disasters. 2005;29(suppl 1):S5–S24. doi: 10.1111/j.0361-3666.2005.00282.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Archibald S, Richards P. Seeds and rights: new approaches to post-war agricultural rehabilitation in Sierra Leone. Disasters. 2002;26:356–367. doi: 10.1111/1467-7717.00212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Buchanan-Smith M, Maxwell S. Linking relief and development: An introduction and overview. IDS Bull. 1994;25:2–16. [Google Scholar]

- 25.European Commission Food Security and Linking Relief, Rehabilitation and Development in the European Commission. FAO International Workshop on Food Security in Complex Emergencies. 2003. Available at: ftp://ftp.fao.org/docrep/fao/meeting/009/ae504e.pdf. Accessed November 1, 2009.

- 26.UN Development Programme . Guidance Note on Early Recovery. UNDG-ECHA Working Group on Transition. Geneva: UNDP; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 27.TANGO International . Development Relief. Tucson, AZ: TANGO International; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development . The Paris Declaration on Aid Effectiveness. Paris: OECD; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development . Principles for Good International Engagement in Fragile States and Situations. Paris: OECD; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Maxwell D, Webb P, Coates J, Wirth J. Fit for purpose? Rethinking food security responses in humanitarian crises. Food Policy. 2010;35:91–97. [Google Scholar]

- 31.U.N. International Strategy for Disaster Reduction . The Hyogo Framework for Action 2005–2015: Building the Resilience of Nations and Communities to Disasters. Geneva: ISDR; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Maxwell D, et al. Participatory Impact Assessment: Africa Community Resilience Programme Tsaeda Amba Woreda, Eastern Tigray, Ethiopia. Feinstein International Center. Medford, MA: Tufts University; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gilligan D, Hoddinott J, Taffesse A. The impact of Ethiopia's productive safety net programme and its linkages. J Dev Stud. 2009;45:1684–1706. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Harvey P, et al. Food Aid and Food Assistance in Emergency and Transitional Contexts: A Review of Current Thinking. Humanitarian Policy Group. London: Overseas Development Institute; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Barrett C, Bell R, Lentz E, Maxwell D. Market information and food insecurity response analysis. Food Security. 2009;1:151–168. [Google Scholar]