Abstract

Activation of naïve cluster of differentiation (CD)8+ cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs) is a tightly regulated process, and specific dendritic cell (DC) subsets are typically required to activate naive CTLs. Potential pathways for antigen presentation leading to CD8+ T-cell priming include direct presentation, cross-presentation, and cross-dressing. To distinguish between these pathways, we designed single-chain trimer (SCT) peptide–MHC class I complexes that can be recognized as intact molecules but cannot deliver antigen to MHC through conventional antigen processing. We demonstrate that cross-dressing is a robust pathway of antigen presentation following vaccination, capable of efficiently activating both naïve and memory CD8+ T cells and requires CD8α+/CD103+ DCs. Significantly, immune responses induced exclusively by cross-dressing were as strong as those induced exclusively through cross-presentation. Thus, cross-dressing is an important pathway of antigen presentation, with important implications for the study of CD8+ T-cell responses to viral infection, tumors, and vaccines.

Professional antigen-presenting cells (APCs) are typically required to activate naïve cluster of differentiation (CD)8+ T cells, either by direct priming or cross-priming. In direct priming, infected (viral infection) or directly transfected (DNA vaccination) APCs synthesize the foreign antigen and use endogenous MHC class I pathways of antigen presentation to present antigen and prime CD8+ T cells. In cross-priming, APCs are able to capture, process, and present exogenous antigen onto MHC class I molecules through a process known as cross-presentation (1). Cross-priming has been shown to be an essential pathway for immunity to many viral infections and tumors. Although the pathways that lead to cross-presentation remain incompletely understood, increasing evidence suggests that only certain dendritic cell (DC) subsets are efficient in this process.

Cross-dressing involves the transfer of intact MHC class I/peptide complexes between cells without the requirement for further processing, representing an alternative pathway of indirect antigen presentation (2, 3). Although cross-dressed DCs can activate memory CD8+ T cells following viral infection in vivo (4), it remains unclear whether cross-dressing can prime naïve CD8+ T-cell responses, what DC subtypes are required to prime CD8+ T cells by cross-dressing, and how robust this pathway is compared with traditional pathways of indirect antigen presentation. These questions must be addressed before the physiologic relevance of cross-dressing can be evaluated in context.

To address these questions, we have taken advantage of Batf3-deficient mice and engineered MHC class I single chain trimer (SCT) constructs. Batf3−/− mice have a selective loss of CD8α+ and CD103+ DCs, without abnormalities in other hematopoietic cell types or architecture (5). DCs from Batf3−/− mice are deficient in cross-presentation, and cytotoxic T lymphocyte (CTL) responses to viral infection and syngeneic tumors are impaired in Batf3−/− mice. Thus, Batf3−/− mice represent a valuable model system to study cross-presentation, cross-dressing, and the role of CD8α+/CD103+ DCs following DNA or cellular vaccination. We have previously engineered completely assembled MHC class I SCT whereby all three components of the complex (heavy chain, β2m, and peptide) are attached by flexible linkers (6). Through progressive molecular engineering, even peptides with low binding affinities can be successfully anchored in the peptide binding groove by a disulfide trap between the first linker and the heavy chain (7–9). Using these experimental tools, we demonstrate that cross-dressing is a robust pathway of antigen presentation following DNA and cellular vaccination, capable of priming naïve and memory CD8+ T cells. In addition, we demonstrate that CD8α+/CD103+ DCs are required to prime CTLs by cross-dressing.

Results

CD8α+/CD103+ DCs Are Required to Prime CD8+ T Cells Following DNA Vaccination.

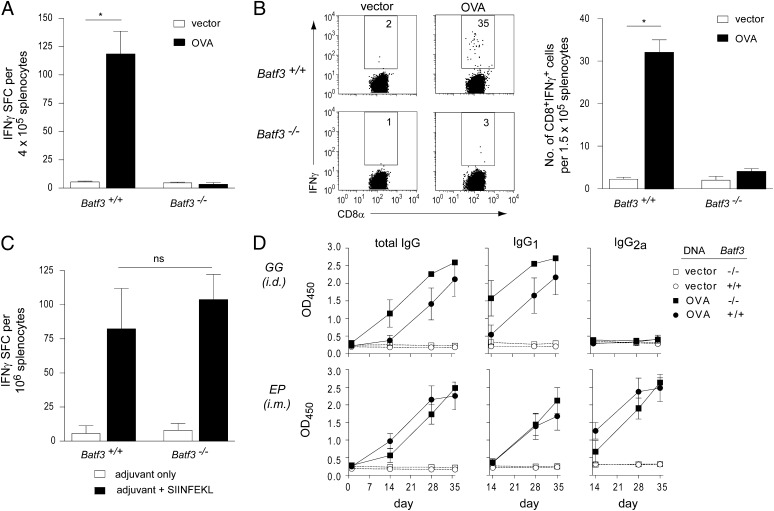

Recently, we identified Batf3 as a key transcription factor controlling the development of CD8α+ and CD103+ DCs (5). Batf3−/− mice lack CD8α+/CD103+ DC subsets and have reduced CD8+ T-cell responses to viral infection and syngeneic tumors, but their responses to cell-based or DNA vaccines and capacity for cross-dressing have not been examined. We first measured responses in Batf3−/− mice to a DNA vaccine expressing soluble chicken ovalbumin (OVA) protein. Batf3−/− mice showed markedly reduced CD8+ T-cell responses, as assessed by IFN-γ production relative to wild-type (WT) mice (Fig. 1 A and B), suggesting that conventional DNA vaccination proceeds via indirect antigen presentation. In response to immunization using the major OVA peptide epitope SIINFEKL, Batf3−/− mice showed a normal CD8+ T-cell response (Fig. 1C), indicating that defective responses of Batf3−/− mice was not caused by an intrinsic T-cell defect. Moreover, Batf3−/− mice developed normal isotype-switched OVA-specific antibody responses (Fig. 1D), suggesting no significant defect in CD4+ helper T-cell responses. Of note, Batf3−/− mice had normal cellular infiltrates at the immunization site (Fig. S1). Together, these results confirm a requirement for CD8α+/CD103+ DCs in priming CD8+ T cells in response to DNA vaccination but do not determine whether these DCs obtain antigen in this setting through conventional cross-presentation or by cross-dressing.

Fig. 1.

CD8+ T-cell priming is selectively ablated in Batf3−/− mice following DNA vaccination. (A and B) WT and Batf3−/- mice (n = 5 per group) were immunized with OVA plasmid DNA. CD8+ T-cell responses were measured by IFN-γ enzyme-linked immunosorbent spot assay (ELISPOT) and intracellular cytokine staining. The results are representative of at least three independent experiments. (C) WT and Batf3−/− mice were vaccinated with SIINFEKL peptide and adjuvant or adjuvant alone. CD8+ T-cell responses were measured by IFN-γ ELISPOT. (D) WT and Batf3−/− mice were vaccinated with OVA plasmid DNA. Sera were collected before and after vaccination. OVA-specific total IgG, IgG1, and IgG2a were measured by ELISA, and the levels were equivalent between WT and Batf3−/− mice. *P < 0.01; ns, not significant; SFC, spot forming cells.

MHC Class I SCTs Are Recognized as Intact Complexes.

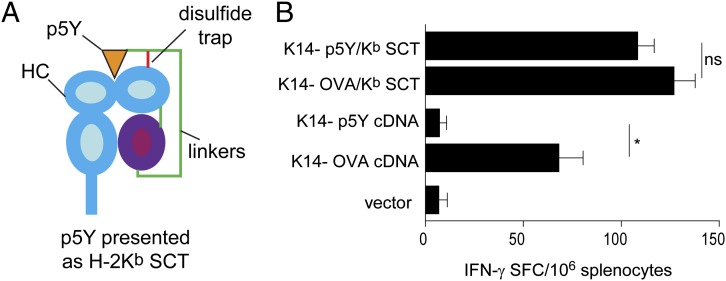

We previously generated SCT complexes by integrating the class I heavy chain, β2m, and peptide with flexible linkers into a single ORF (6). SCTs are recognized by T cells in a manner equivalent to peptide–MHC complexes generated by conventional antigen processing (10–12) and induce robust immune responses when used as DNA vaccines (7, 13). Importantly, SCTs allow peptides with very weak affinity for MHC to be anchored into the peptide binding groove through a disulfide bond between the linker and heavy chain (Fig. 2A) (7–9). Moreover, SCTs are recognized as intact molecules, because the D227K mutation in the α3 domain of the OVA/Kb SCT abrogates CD8 interaction (14) and induces diminished Kb-specific CD8+ T-cell responses when used in a DNA vaccine (Fig. S2A). Similarly, a chimeric A2Db/West Nile virus SCT showed increased responses in HHD II mice transgenic for the same chimeric A2Db class I MHC molecules (15) (Fig. S2B). Together, these data show that SCT constructs are recognized as intact complexes.

Fig. 2.

Molecular engineering of SCT peptide–MHC complexes precludes cross-presentation. (A) Schematic of the p5Y/Kb SCT, integrating the p5Y peptide, β2m, and H2-Kb heavy chain (HC). Of note, the disulfide bond (red line) formed between linker 1 and the α1 domain traps the low-affinity p5Y epitope in the peptide binding groove. (B) C57BL/6 mice (n = 4 per group) were vaccinated with the indicated DNA constructs. Kb/SIINFEKL-specific immune responses were measured by ELISPOT. Data are presented as means ± SEM. *P < 0.01; ns, not significant. Similar results were obtained in at least three independent experiments.

p5Y SCT Cannot Be Cross-Presented by Endogenous H-2Kb.

Previous studies did not exclude the possibility that the peptide in an SCT complex could additionally be cross-presented. We, therefore, generated an SCT, p5Y/Kb SCT (Fig. 2A), that contains an altered OVA peptide ligand SIINYEKL, which binds to Kb with a 1,000-fold lower affinity compared with the WT peptide SIINFEKL (Fig. S3) (16). To test whether this altered peptide from the SCT could be cross-presented, we immunized mice with DNA vaccines with the keratinocyte-specific K14 promoter (17) driving expression of cDNA or SCT constructs corresponding to either WT OVA or the mutant SIINYEKL sequence (Fig. 2B). Immunization using WT OVA cDNA induced strong CD8+ T-cell responses, but immunization with a cDNA encoding OVA with the altered SIINYEKL sequence failed to induce CD8+ T-cell responses. This result indicates that the altered epitope binds too weakly to allow presentation by endogenous H-2Kb MHC molecules via conventional processing pathways (16). Immunization with the SCT harboring either the WT SIINFEKL or the altered epitope SIINYEKL presented by Kb induced equally strong CD8+ T-cell responses. These results show that SCTs are recognized as an intact complex and can prime T-cell responses to peptide epitopes that cannot be conventionally cross-presented because of low affinity for MHC.

Cross-Dressed DCs Prime CD8+ T Cells in Vivo and in Vitro.

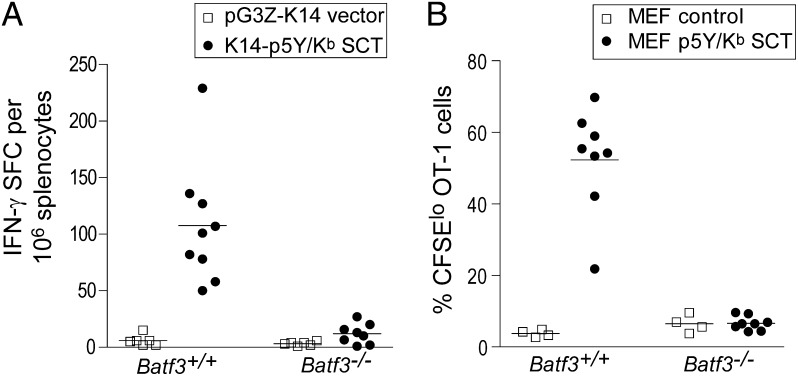

Efficient CD8+ T-cell priming after epicutaneous DNA immunization using the K14 promoter (17) suggests that SCTs are produced in keratinocytes but transferred to DCs. Alternately, T-cell priming could have resulted from direct recognition of SCTs expressed by keratinocytes and so could be independent of DCs. To test these hypotheses, we immunized WT and Batf3−/− mice with SCT DNA vaccines driven by the K14 promoter expressing the SIINYEKL epitope presented by Kb. This vaccination induced strong CD8+ T-cell responses in WT mice, but CD8+ T-cell responses were reduced to background in Batf3−/− mice (Fig. 3A). Thus, CD8+ T-cell priming by vaccination with DNA encoding an SCT requires the participation of CD8α+/CD103+ DCs.

Fig. 3.

Engineered SCT vaccines prime CD8+ T-cell responses in vivo by cross-dressing. (A) WT or Batf3−/− mice were vaccinated with K14-p5Y/Kb SCT DNA or control DNA by gene gun. CD8+ T-cell responses were measured by IFN-γ ELISPOT. (B) A total of 2 × 106 CFSE-labeled OT-1 cells were adoptively transferred into WT or Batf3−/− mice. Twenty-four hours later, 5 × 106 necrotic fibroblasts were injected (s.c.). Ninety hours later, draining lymph nodes were harvested, and OT-1 cell proliferation was determined by flow cytometry. The percentage of OT-1 cells (identified as CD8+CD45.1+) that divided at least once (CFSElo) is shown. The results are representative of three independent experiments. Each data point represents an individual animal. (Bars indicate mean values for each experimental group.)

Potentially, these DCs were directly transfected by the DNA vaccine to generate SCT complexes rather than obtaining these complexes from keratinocytes. To test this possibility, we stably expressed the p5Y/Kb SCT into mouse embryonic fibroblasts lacking endogenous Kb, Db, and β2m (3KO MEFs). We adoptively transferred carboxyfluorescein diacetate succinimidyl ester (CFSE)-labeled OT-1 T cells into C57BL/6 mice, and then vaccinated mice 24 h later with necrotic 3KO p5Y/Kb SCT MEFs or 3KO MEF parental control cells. After 90 h, draining lymph nodes were harvested and OT-1 proliferation was analyzed by flow cytometry. Vaccination of WT mice with 3KO p5Y/Kb SCT MEFs, but not control parental cells, induced strong proliferation of OT-1 T cells in vivo (Fig. 3B and Fig. S4A). However, this proliferation is absent in Batf3−/− mice (Fig. 3B), indicating that the in vivo proliferation was not attributable to direct recognition of the p5Y/Kb SCT on MEFs but required presentation of these complexes by Batf3-dependent CD8α+/CD103+ DCs. Vaccination with live 3KO p5Y/Kb SCT MEFs can also induce an endogenous Kb/SIINFEKL-specific immune response as measured by IFN-γ ELISPOT (Fig. S4B). This result suggests that the p5Y/Kb SCT expressed on MEFs was transferred to CD8α+/CD103+ DCs, which induced proliferation of CD8+ T cells.

To observe such transfer directly, 3KO p5Y/ Kb SCT MEFs were subjected to several freeze-thaw cycles to induce necrosis, cultured with DC2.4 DCs, and analyzed by FACS using the OVA/Kb-specific monoclonal antibody 25-D1.16 (Fig. S5A). A detectable increase in 25-D1.16 staining was observed on DC2.4 cells cultured with 3KO p5Y/ Kb SCT MEFs compared with DC2.4 cultured with control 3KO MEFs. Further, OT-1 T-cell proliferation was observed only when 3KO p5Y/Kb SCT MEFs and DC2.4 cells were present (Fig. S5A). In addition, we performed studies in vitro using the epitope-specific antibody 25.D1.16 and confocal microscopy. In these studies, we are able to demonstrate cross-dressing of intact p5Y/Kb SCT complexes from 3KO p5Y/Kb SCT MEFs to C57BL/B6 and transporter associated with antigen processing (TAP)−/− DCs (Fig. S5B). These results support the interpretation that p5Y/Kb SCT complexes are transferred from 3KO MEFs to DCs to activate OT-1 T cells.

Cross-Dressed DCs Activate both Naïve and Memory CD8+ T Cells.

Wakim and Bevan (4) reported that in a vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV) infection model, cross-dressed DCs activate memory, but not naïve, CD8+ T cells, whereas we find that with DNA and cellular vaccines, cross-dressed DCs efficiently activate naïve CD8+ T cells. To examine memory CD8+ T cells, we transferred in vitro–activated OT-1 cells into C57BL/6 mice and recovered memory phenotype cells after 30 d by negative selection (Fig. S6 A and B). Memory and naïve OT-1 cells were labeled with CFSE and transferred into WT and Batf3−/− mice, which were challenged after 24 h with necrotic 3KO p5Y/ Kb SCT MEFs. Lymph nodes and spleens were harvested 90 h later, and OT-1 proliferation was examined by FACS. Vaccination with 3KO p5Y/ Kb SCT MEFs induced proliferation of both naïve and memory OT-1 cells in WT mice but not in Batf3−/− mice (Fig. S6 C and D). This result suggests that at least with cell-based immunization, cross-dressed DCs are capable of inducing proliferation in both naïve and memory CD8+ T cells.

Cross-Dressing Is a Robust Antigen Presentation Pathway in Vivo.

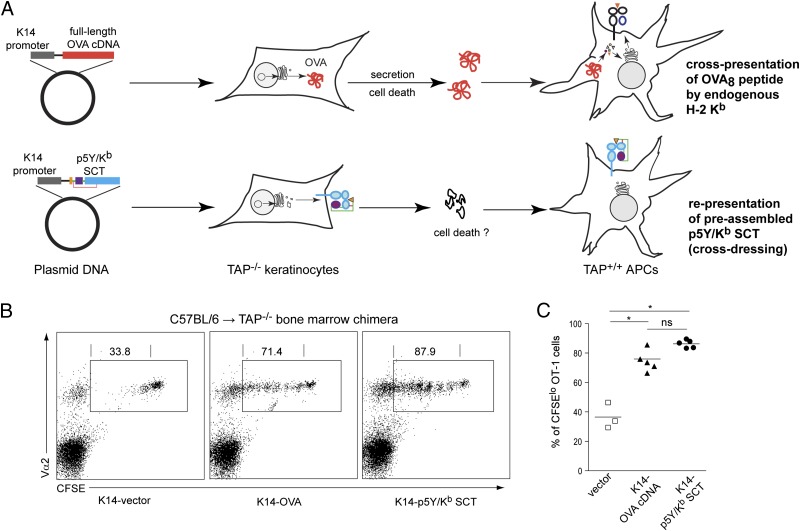

To define the relative contribution of cross-presentation vs. cross-dressing in the response to vaccination, we generated C57BL/6→TAP−/− bone marrow (BM) chimeras. In these chimeras, vaccination with the K14-OVA DNA vaccine cannot generate OVA/Kb complexes from TAP−/− keratinocytes, eliminating cross-dressing but allowing cross-presentation of OVA protein by donor DCs as a route to T-cell activation. After adoptive transfer of CFSE-labeled OT-1 cells, BM chimeras were vaccinated with either a K14-OVA DNA vaccine or a K14-p5Y/ Kb SCT DNA vaccine (Fig. 4A and Fig. S7). Both DNA vaccines induced robust proliferation of OT-1 cells in BM chimeras (Fig. 4 B and C), suggesting that CD8+ T-cell priming occurs by both cross-dressing and by cross-presentation in this model system.

Fig. 4.

Cross-dressing is a robust antigen-presentation pathway in vivo. CFSE-labeled OT-1 cells were adoptively transferred into the C57BL/6→TAP−/− BM chimeras, which were subsequently vaccinated with K14-OVA or K14-p5Y/Kb SCT. (A) This experimental model system results in CD8+ T-cell priming by two distinct, nonoverlapping antigen-presentation pathways. (B) Spleen cells from vaccinated mice were collected and analyzed by flow cytometry. Representative two-color dot plots show expression of CFSE and Vα2 by viable CD8+ T cells. Gated regions represent OT-1 cells (expressing CFSE, CD8, and Vα2). Numbers indicate the percentage of CFSElo OT-1 cells that had gone through at least one cell division. (C) Summary of data from individual animals (n = 3–5 per group). *P < 0.01; ns, not significant.

Discussion

The studies reported here provide important insights into the importance of cross-dressing as a pathway for activation of CTLs. Using engineered SCT vaccines and Batf3-deficient mice, we demonstrate that cross-dressing is a robust pathway of cross-presentation, with the ability to prime both naïve and memory CTLs. Not only do these studies have important implications for the rational design of DNA and cellular vaccines, but they also have broader implications for understanding other immune responses generally considered to be dependent on cross-priming, such as viral infection and malignancy.

Our findings differ with Wakim and Bevan (4) in two ways. First, our data suggest that cross-dressed DCs can activate both naïve T cells and memory CD8+ T cells. Following VSV infection, memory, but not naïve, CD8+ T cells were activated by cross-dressed DCs (4). Conceivably, cross-dressing is inefficient following VSV infection relative to DNA or cell-based vaccination, resulting in low levels of antigen expression. Second, our data indicate that CD8α+/CD103+ DCs are required to prime CD8+ T-cell responses by cross-dressing. Following lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus (LCMV) infection, cross-dressed CD8α− DCs are more efficient at stimulating a T-cell hybridoma ex vivo than cross-dressed CD8α+ DCs (4), but in vitro studies have suggested that both CD8α− DCs and CD8α+ DCs can acquire peptide–MHC complexes by cross-dressing (18). Anatomic location, cytokine production, or costimulatory receptors may also contribute to the in vivo capacity for CD8α+ DCs to prime CD8+ T-cell responses. It is possible that differences in experimental settings (viral infection vs. DNA vaccination vs. fibroblast injection) may explain the apparent conflict between our results and the results of Wakim and Bevan.

In addition, we have separately compared cross-presentation and cross-dressing in priming CD8+ T-cell responses. After reconstitution of TAP−/− mice with C57BL/6 BM, we compared two DNA vaccination strategies using the same keratinocyte-specific promoter and model antigen. Both cross-presentation and cross-dressing pathways were able to induce similarly robust priming of CD8+ T-cell responses, suggesting that cross-dressing can be an important route of antigen presentation following vaccination. These studies also provide some insight into where cross-dressing may be occurring. Following vaccination with the K14 promoter construct, p5Y/Kb SCT expression is restricted to the dermis. Thus, exchange of intact p5Y/Kb SCT must occur in the periphery. Our data do not exclude the possibility that there is a second cross-dressing event that occurs in the lymph node.

Cross-priming is an important mechanism for activation of CD8+ T cells that was first described over 25 y ago (19), and it is currently thought to proceed via cross-presentation rather than cross-dressing (4). Our results indicate otherwise, suggesting that cross-dressing can play an equally important role in CD8+ T-cell priming. In addition, our studies have direct clinical implications, as strategies to optimize DNA and/or cellular vaccination depend critically on the pathway(s) of antigen presentation and the specific DC subtypes involved.

Materials and Methods

Animals.

WT C57BL/6, 129SvEv, and TAP−/− mice were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory and Taconic, respectively. The generation of Batf3−/− mice on the 129SvEv background was described previously (5). For experiments involving OT-1 adoptive transfer, Batf3−/− backcrossed to C57BL/6 background for at least 10 generations were also used. HHD II mice (13, 15) are H-2Db−/− and β2m−/− double knockout but express HLA-A2/H-2Db chimeric heavy chain covalently linked to human β2m. OT-1 transgenic mice were originally purchased from The Jackson Laboratory and maintained as CD45.1 congenic by breeding to B6.SJL-PtprcaPepcb/BoyJ mice (The Jackson Laboratory). For some experiments, RAG2/OT-1 mice (Taconic) were used. All mice were bred and maintained in specific pathogen-free animal facilities according to institutional guidelines. Protocols were approved by the Animal Studies Committee at the Washington University School of Medicine. Generally, 8- to 12-wk-old sex and age-matched mice were used in the experiments.

DNA and Peptide Immunization.

Full-length OVA cDNA was cloned into the pcDNA3.1(+) vector (Invitrogen) using standard techniques and was confirmed by DNA sequencing. Construction and progressive engineering of SCT has been described previously (6, 7, 9, 20). Mutations were introduced to SCT by site-directed mutagenesis (QuikChange II kit; Stratagene). DNA was administered by Helios gene gun (Bio-Rad) at 3-d intervals for a total of three doses. A total of 4 μg of DNA was delivered to nonoverlapping depilated abdominal skin with discharge helium pressure set to 400 psi. Primary immune responses were examined 5 d after the final vaccination. For DNA vaccination via intramuscular electroporation (EP), the TriGrid Delivery System (Ichor Medical Systems) was used. A total of 10 μg of DNA (20 μL) was injected (i.m.), followed by the application of a preprogrammed electric current. For peptide vaccination, 40 μg of OVA8 peptide (AnaSpec) was mixed with the adjuvant TiterMax Gold (Sigma-Aldrich) and injected (s.c.) at the dorsal tail base.

Antibodies and Flow Cytometry.

Fluorophore-labeled monoclonal antibodies were purchased from BD Bioscience, eBioscience, BioLegend, Miltenyi Biotec, and Dendritics. Antibody staining was generally performed in the presence of Fc block (BD). All flow cytometric data were collected on FACSCalibur or FACS Canto II instruments (BD Bioscience) and analyzed using FlowJo software (TreeStar).

ELISPOT Assay.

IFN-γ ELISPOT assay was performed with reagents purchased from Mabtech unless otherwise noted. Briefly, 96-well PVDF filtration plates (Millipore) were coated overnight with 15 μg/mL capture antibody. Erythrocyte-free single-cell suspensions from the spleen were added in triplicate and incubated for 20 h with or without the presence of 1 μM OVA8 peptide (AnaSpec). After extensive washes, 1 μg/mL biotinylated detection antibody was added. Streptavidin-alkaline phosphatase (ALP) and 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl phosphate/nitro blue tetrazolium (BCIP/NBT) (Moss Substrates) were subsequently used for color development. Plates were scanned and analyzed on an ImmunoSpot reader (C.T.L.).

Anti-OVA ELISA.

Microtiter plates (96-well) (Corning) were coated with 150 μg/mL OVA (Sigma-Aldrich) and blocked. A total of 100 μL of immune sera (diluted 1:200) was added and incubated for 2 h. The plates were washed and HRP-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG, IgG1, or IgG2a (Southern Biotech, diluted 1:5,000) were added and incubated for 1.5 h. The amount of bound OVA-specific Ab was determined by measuring the absorbance at 450 nm with a microplate reader (Bio-Rad; Model 550) after colorimetric development using 3,3′,5,5′- tetramethylbenzidine (TMB) substrate solution (Moss Substrates).

OT-1 T-Cell Isolation, CFSE Labeling, and Adoptive Transfer.

Naïve OT-1 T cells were isolated from the spleens of transgenic mice using a CD8+ T-cell enrichment kit (BD). Cells were labeled with 5 μM CFSE (Molecular Probes) at a concentration of 10 × 106/mL for 8 min. After quenching and extensive washing, cells were adoptively transferred to recipient mice via retroorbital injection.

Cell Culture.

The 3KO MEFs were derived from a 16-d 3KO embryo (21) and maintained in DMEM with high glucose and l-glutamine (Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% (vol/vol) FBS (Atlanta Biologicals), Hepes, sodium pyruvate, nonessential amino acids, and antibiotic/antimycotic (all from Mediatech). Retroviruses encoding p5Y/Kb SCT were prepared (21) and used to transduce 3KO MEFs. Cells expressing high levels of SCT were selected and maintained in complete DMEM. DC2.4 (H-2b genotype) cells were cultured in complete DMEM.

C57BL/6→TAP−/− Bone Marrow Chimera.

BM cells were harvested from C57BL/6 mice. 15 × 106 cells were then injected i.v. into lethally irradiated (1,000 rad) recipient TAP−/− mice. Seven weeks later, CFSE-labeled OT-1 cells were adoptively transferred into the B6→TAP−/− BM chimeras, followed by DNA vaccination 24 h afterward.

Data Analysis.

Data were analyzed using Prism 5 (GraphPad Software). An unpaired, two-tailed Student’s t test was used to compare differences between groups, with P ≤ 0.05 considered significant. Figures were exported and prepared using Adobe Illustrator CS3 (Adobe Systems).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Michael Bevan (University of Washington) and Paul Allen (Washington University) for critical review of the manuscript. We also thank Ichor Medical Systems for providing the TriGrid Delivery System and Dr. Thomas Griffith (University of Minnesota) for providing the Ad5.CMV-Flt3L viruses. This work was supported by Susan G. Komen for the Cure Grant KG080476 (to W.E.G. and L.L.), Department of Defense Grant W81XWH-06-1-0677 (to W.E.G.), National Institutes of Health Grant AI055849 (to T.H.H.); and grants from The Howard Hughes Medical Institute (to K.M.M.) and Frank Cancer Research Fund awarded by The Barnes–Jewish Hospital Foundation (to P.G.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1203468109/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Kurts C, Robinson BW, Knolle PA. Cross-priming in health and disease. Nat Rev Immunol. 2010;10:403–414. doi: 10.1038/nri2780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dolan BP, Gibbs KD, Jr, Ostrand-Rosenberg S. Dendritic cells cross-dressed with peptide MHC class I complexes prime CD8+ T cells. J Immunol. 2006;177:6018–6024. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.9.6018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dolan BP, Gibbs KD, Jr, Ostrand-Rosenberg S. Tumor-specific CD4+ T cells are activated by “cross-dressed” dendritic cells presenting peptide-MHC class II complexes acquired from cell-based cancer vaccines. J Immunol. 2006;176:1447–1455. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.3.1447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wakim LM, Bevan MJ. Cross-dressed dendritic cells drive memory CD8+ T-cell activation after viral infection. Nature. 2011;471:629–632. doi: 10.1038/nature09863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hildner K, et al. Batf3 deficiency reveals a critical role for CD8alpha+ dendritic cells in cytotoxic T cell immunity. Science. 2008;322:1097–1100. doi: 10.1126/science.1164206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yu YY, Netuschil N, Lybarger L, Connolly JM, Hansen TH. Cutting edge: Single-chain trimers of MHC class I molecules form stable structures that potently stimulate antigen-specific T cells and B cells. J Immunol. 2002;168:3145–3149. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.7.3145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li L, et al. Engineering superior DNA vaccines: MHC class I single chain trimers bypass antigen processing and enhance the immune response to low affinity antigens. Vaccine. 2010;28:1911–1918. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2009.10.096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mitaksov V, et al. Structural engineering of pMHC reagents for T cell vaccines and diagnostics. Chem Biol. 2007;14:909–922. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2007.07.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Truscott SM, et al. Disulfide bond engineering to trap peptides in the MHC class I binding groove. J Immunol. 2007;178:6280–6289. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.10.6280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim S, et al. Licensing of natural killer cells by host major histocompatibility complex class I molecules. Nature. 2005;436:709–713. doi: 10.1038/nature03847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Choudhuri K, Wiseman D, Brown MH, Gould K, van der Merwe PA. T-cell receptor triggering is critically dependent on the dimensions of its peptide-MHC ligand. Nature. 2005;436:578–582. doi: 10.1038/nature03843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang B, et al. A single peptide-MHC complex positively selects a diverse and specific CD8 T cell repertoire. Science. 2009;326:871–874. doi: 10.1126/science.1177627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim S, et al. Single-chain HLA-A2 MHC trimers that incorporate an immundominant peptide elicit protective T cell immunity against lethal West Nile virus infection. J Immunol. 2010;184:4423–4430. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0903955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Connolly JM, Hansen TH, Ingold AL, Potter TA. Recognition by CD8 on cytotoxic T lymphocytes is ablated by several substitutions in the class I alpha 3 domain: CD8 and the T-cell receptor recognize the same class I molecule. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:2137–2141. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.6.2137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pascolo S, et al. HLA-A2.1-restricted education and cytolytic activity of CD8(+) T lymphocytes from beta2 microglobulin (beta2m) HLA-A2.1 monochain transgenic H-2Db beta2m double knockout mice. J Exp Med. 1997;185:2043–2051. doi: 10.1084/jem.185.12.2043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Howarth M, Williams A, Tolstrup AB, Elliott T. Tapasin enhances MHC class I peptide presentation according to peptide half-life. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:11737–11742. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0306294101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vassar R, Rosenberg M, Ross S, Tyner A, Fuchs E. Tissue-specific and differentiation-specific expression of a human K14 keratin gene in transgenic mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:1563–1567. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.5.1563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Smyth LA, et al. The relative efficiency of acquisition of MHC:peptide complexes and cross-presentation depends on dendritic cell type. J Immunol. 2008;181:3212–3220. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.5.3212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bevan MJ. Cross-priming for a secondary cytotoxic response to minor H antigens with H-2 congenic cells which do not cross-react in the cytotoxic assay. J Exp Med. 1976;143:1283–1288. doi: 10.1084/jem.143.5.1283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hansen T, Yu YY, Fremont DH. Preparation of stable single-chain trimers engineered with peptide, β2 microglobulin, and MHC heavy chain. Curr Protoc Immunol. 2009 doi: 10.1002/0471142735.im1705s87. 2009;Chapter 17:Unit17.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lybarger L, Wang X, Harris MR, Virgin HW, 4th, Hansen TH. Virus subversion of the MHC class I peptide-loading complex. Immunity. 2003;18:121–130. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(02)00509-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.