Abstract

In rats, Pavlovian sign-tracking has been extensively evaluated as a model of compulsiveness in drug addiction and other addictive behaviors, but it remains unexplored in mice, a species with a wealth of genetically modified models, which makes it possible to examine gene-behavior relationships. In C57BL/6 mice, the most commonly used mouse strain for genetic studies, repeated pairings of lever conditioned stimulus (CS) with food unconditioned stimulus (US) induced Pavlovian conditioning of sign-tracking conditioned response (ST CR) performance of lever CS-directed approach, and Pavlovian conditioning of goal-tracking conditioned response (GT CR) performance of approach responses directed at the location of the food trough where the food US was delivered. The CS–US Paired group performed more ST CRs and more GT CRs during sessions 15–16 than did pseudoconditioning controls which received the lever CS and food US randomly with respect to one another. During sessions 15–16, all mice in the Paired group performed more GT CRs than ST CRs, and regression analysis revealed a positive relationship between an individual subject's tendency to perform ST CRs and GT CRs. The mice that performed more ST CRs during sessions 15–16 yielded higher plasma corticosterone levels. These data reveal stable and reliable acquisition and maintenance of ST CR performance and GT CR performance in mice; however, unlike in rats, ST CRs and GT CRs did not vary inversely within subjects. Corticosterone release, a pathophysiological marker of vulnerability to drug abuse, was positively related to ST CR performance.

Keywords: Sign-tracking, Goal-tracking, Corticosterone, Incentive salience, Pavlovian conditioned approach, Pseudoconditioning

1. Introduction

Addiction researchers have noted striking parallels between Pavlovian sign-tracking (also called autoshaping or Pavlovian conditioned approach) and drug addiction phenomena [1–6]. Pavlovian conditioned approach procedures consist of pairings of a small object, employed as the conditioned stimulus (CS), followed closely in time by the presentation of the rewarding unconditioned stimulus (US). Experience with repeated CS–US pairings leads to the acquisition of Pavlovian sign-tracking conditioned response (CR) performance, a complex sequence of CS-directed skeletal-motor responses. For example, in rats, the brief presentation of the retractable lever CS prior to the response-independent delivery of the food US may elicit, in some rats, lever CS-directed approach responses, often followed by grasping, gnawing, and chewing of the lever CS, which occur with greater frequency than in a pseudo-conditioning control group receiving presentations of lever CS and food US randomly with respect to one another [7]. Important to the understanding of sign-tracking, the CR develops even though the food US is delivered without regard to what the subject does. For example, the lever CS is typically located at a distance from the food trough, where the food US is delivered. Under these conditions, therefore, the performance of the sign-tracking CR actually requires the expenditure of physical effort that serves only to delay the opportunity to eat the food US.

Lever CS–food US pairings may also induce another form of conditioned responding, called goal-tracking. Insertion of the lever CS may induce the subject, prior to the delivery of the food US, to approach the location of the food trough [8]. Addiction researchers have reported that rats may be differentiated based on how they respond to the presentation of the lever CS that signals the impending delivery of the food US. Sign-trackers respond predominantly by approaching the location of the lever CS, while goal-trackers respond predominantly by approaching the location of the trough where the food US is delivered. Most significantly, the Sign-tracker phenotype, relative to the Goal-tracker phenotype, more readily self-administered cocaine [9–11], developed greater sensitization of psychomotor activation to repeated exposures to cocaine [12], and exhibited a profile of neurobiological markers related to elevated vulnerability to drug abuse [5]. Thus, the tendency to perform sign-tracking CRs may reveal the tendency to attribute incentive salience to reward-related stimuli, a behavioral trait that may predispose vulnerability to drug addiction [5,6,13–15]. Sign-tracking CR performance has also been related to elevated plasma corticosterone levels [16–19] which has also been proposed as a pathophysiological marker of vulnerability to drug abuse [20–22].

Sign-tracking CR performance has been reported in numerous species, including rats, monkeys, pigeons, and humans [7]. While most reports of sign-tracking CR performance in mice have included procedures providing for response-dependent presentations of the US [23–26], there are reports of Pavlovian sign-tracking CR performance in mice that provided for response-independent presentations of the US. For example, Papachristos and Gallistel [27] showed that mere pairings of a light CS with food pellet US induced C57BL/6 mice to nose-poke the location of the light CS. While there are ample demonstrations of sign-tracking CR performance in mice, there are no published studies of Pavlovian conditioned approach in mice that also evaluated goal-tracking CR performance, or studies providing controls assessing the levels of pseudoconditioning of CR-like responding, or studies evaluating plasma corticosterone levels.

The present study evaluated, in C57BL/6 mice, the effects of Pavlovian conditioned approach procedures, which consisted of the brief insertion of a lever CS followed by the response-independent presentation of the food US, on the development of lever CS-directed sign-tracking CR performance and food trough-directed goal-tracking CR performance. In addition, controls were provided with randomly related presentations of the lever CS and food US to assess pseudoconditioning. Finally, post-session trunk blood samples were obtained to assess group mean differences and individual subject differences in plasma corticosterone levels.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Subjects

Forty-five male C57/BL/6 mice, obtained from Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, ME), were approximately six weeks old and weighed approximately 25 g at the beginning of the study. The mice were housed individually in plastic shoebox cages, with free access to food and water, in a colony room maintained on a 12 h light–dark cycle (lights on at 06:00 h).

2.2. Apparatus

The apparatus consisted of eight testing chambers (Med Associates, St. Albans, VT) each equipped with a transparent inner cage (32 cm × 25 cm floor area, 30 cm high). Each testing chamber was equipped with an intelligence panel containing a retractable lever located 3 cm above the chamber floor, and a pellet dispenserwhich released a 20 mg food pellet into a food magazine trough located 8.5 cm to the right of the lever and 3 cm above the chamber floor. The insertion of the retractable lever into the chamber was accompanied by the illumination of a light emitting diode (LED), which was attached to the interior wall of the lever housing. The LED remained illuminated until the lever was removed from the chamber. All experimental events were controlled by Med Associates software.

Each chamber was equipped with two digital board cameras (Model VPC-790B, Pacific Corp, Tokyo, Japan). One camera was mounted on the ceiling of the chamber and video recorded the location of the mouse on the floor of the chamber during experimental sessions 6–7 and 15–16. The second camera was mounted near the floor level of the chamber and video recorded a panel of LED lights that signaled experimental events. One LED was illuminated when an experimental session was in progress, a second LED was illuminated when the lever was inserted into the chamber, and a third LED was illuminated when the pellet dispenser was operated. Video recordings of each experimental session were scored by Clever Systems software (Clever Sys Inc, Reston, VA).

A sign-tracking (ST) CR was scored when, following the insertion of the lever into the chamber and prior to the retraction of the lever from the chamber, the overhead camera video recorded the entry of the mouse into a region of the chamber floor immediately adjacent to the lever. The scoring software continuously marked the snout, neck, and body of the mouse, as well as all of the area of the chamber floor that was within 1.5 cm of the extended lever and all of the area of the chamber floor that was within 1.5 cm of the food trough. A ST CR was scored when the mouse performed a forward movement of the head and body such that the snout moved from outside the scoring target area to inside the scoring target area that was adjacent to the extended lever, and this movement occurred during the 5 s period of time that the lever was extended into the chamber. Backing into the target area adjacent to the lever was not scored as a ST CR. A goal-tracking (GT) CR was scored when, during the 5 s period of time that the lever was extended into the chamber the overhead camera video recorded a forward movement of the head and body such that the snout moved from outside the scoring target area to inside the scoring target area that was adjacent to the food trough where the food US pellets were delivered. Backing into the target area adjacent to the food trough was not scored as a GT CR.

2.3. Experimental procedures

Prior to the experiment all of the mice were trained to respond to the operation of the pellet dispenser by entering the area of the food magazine and eating the pellet of food in the trough. Following food magazine training, the 45 mice were randomly divided into two groups. Mice in the Paired group (n = 33) received Pavlovian conditioned approach procedures, wherein the lever CS was inserted into the chamber for 5 s and the retraction of the lever CS was followed immediately by the response-independent delivery of the food pellet US. Mice in the Random group (n = 12), served as pseudoconditioning controls and received training similar to that of the Paired group, except the food pellet US was delivered randomly with respect to the insertion of the lever CS. Each daily session was approximately 45 min in duration and consisted of 40 lever CS trials, separated by an average inter-trial interval of 60s, with the exact duration of each inter-trial interval randomized by Med Associates software. During the first 5 sessions, unsystematic observations revealed that few subjects performed any ST CRs. During sessions 6 and 7, and during sessions 15 and 16, the video camera mounted in the ceiling of each chamber was activated to record the movements of the subject during the experimental session. Clever Systems software was later used to score the number of ST CRs and GT CRs during each trial. Following the last daily session, subjects were sacrificed by rapid decapitation. Trunk blood samples were collected, centrifuged, and pipetted in duplicate, then frozen at −80 °C, until analyzed. Plasma corticosterone was assayed by radioimmunoassay (3H RIA kit, Product #07-120002, MP Biomedicals, Irvine, CA), using a tritium label for corticosterone and a specific corticosterone antiserum with a detection threshold of 0.1 (μg/100 ml. Corticosterone measurements did not vary by more than 10% between sample duplicates.

2.4. Statistical analysis

For each subject, the number of ST CRs (measure of ST CR Frequency) and the number of GT CRs (measure of GT CR Frequency) on each of the four video recorded sessions (6, 7, 15, and 16) was obtained. For each subject, the total number of CS presentation periods during a session (maximum = 40) containing at least one ST CR on each of 4 sessions (6, 7, 15, and 16) was obtained, then divided by 40, then multiplied by 100, to derive the percent of CS trials per session with at least one ST CR (measure of ST CR Probability). GT CR Probability was calculated in a similar manner. Thus, the CR Frequency measures are based on the total number of ST or GT responses performed during the entire session; whereas, the CR Probability measures are based on the percentage of trials during the session on which at least one ST or at least one GT response was recorded.

For each subject, the mean ST CR score and the mean GT CR score for each of two 2-session Blocks (sessions 6–7 and sessions 15–16) were calculated. Group differences in CR performance were evaluated using two-way repeated-measures 2 × 2 univariate analysis of variance, ANOVA (Systat Software, Richmond, VA), with two levels of Procedures and two levels of 2-session Blocks (6–7 vs 15–16). Based on an a priori hypothesis that the Paired group would exhibit more CR performance than the Random group, planned comparisons of group differences (Paired vs Random, Low ST Frequency vs Random) in CR performance on sessions 6–7 and on sessions 15–16 were evaluated using separate one-way univariate ANOVAs. Stability of group differences in CR performance and relationships between measures of CR Frequency and CR Probability were evaluated using one-way univariate ANOVA. Correlations between ST CR Frequency and GT CR Frequency were evaluated using simple linear regression.

Group mean plasma corticosterone levels are presented as mean nanograms per milliliter (±SEM). Group differences in mean plasma corticosterone levels were evaluated by one-way analysis of variance using ANOVA (Systat Software, Richmond, VA).

3. Results

3.1. Acquisition of Pavlovian CR performance

Pavlovian approach CR performance was determined by comparing ST CRs in the Paired group to ST CR-like responses in the Random group, and GT CRs in the Paired group to GT CR-like responses in the Random group, and total approach CRs (ST CRs + GT CRs) in the Paired group to total approach CR-like responses in the Random group.

3.1.1. Acquisition of Pavlovian sign-tracking (ST) CR performance

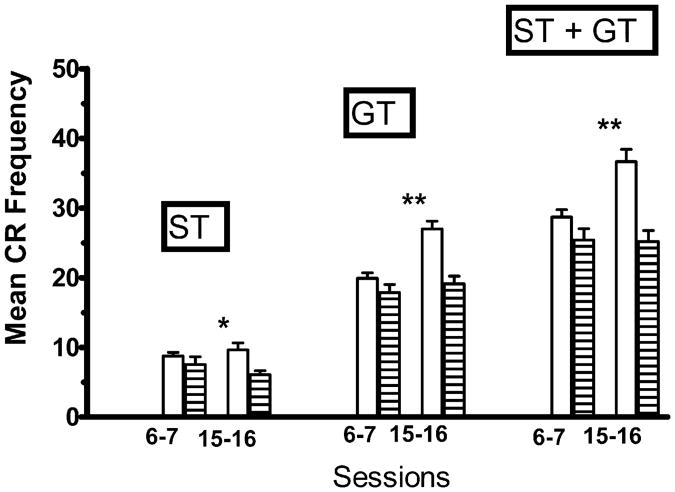

Mean number of ST CRs per session (Sign-Tracking CR Frequency) was significantly greater for the Paired group than the Random group on sessions 15–16 (see Fig. 1, left pair). Two-way, mixed-design, repeated-measures univariate ANOVA, with two levels of Procedures (Paired vs Random) and two levels of 2-session Blocks (6–7 vs 15–16) revealed a significant main effect of Procedures, F(1, 43) = 4.43, P<.05, no significant main effect of Blocks, F< 1, and no significant interaction effect between Procedures and Blocks, F(1, 43) = 1.74, P>.05. One-way ANOVA revealed that the observed difference between the means on sessions 6–7 was not significant, F< 1, but the observed difference between the means on sessions 15–16 was significant, F(1, 43) = 4.26, P<.05.

Fig. 1.

For the 33 subjects in the Paired group (open columns) and the 12 subjects in the Random group (striped columns), mean number of conditioned responses (CRs) per session during sessions 6–7 and during sessions 15–16. A ST CR (left pair) was recorded whenever the subject approached the lever CS during the 5 s period of time that the lever CS was inserted into the chamber. A GT CR (center pair) was recorded whenever the subject approached the location of the food trough during the 5 s period of time that the lever CS was inserted into the chamber, prior to the delivery of the food pellet US into the food trough on each trial. Mean number of total combined sign-tracking CRs + goal tracking CRs (ST + GT) CRs for the Paired and Random groups are presented as the right pair. The vertical bars represent the standard error of the mean. The single asterisk (*) indicates that the groups differed at the .05 level of significance. The double asterisk (**) indicates that the groups differed at the .01 level of significance.

3.1.2. Acquisition of Pavlovian goal-tracking (GT) CR performance

Mean number of GT CRs per session was significantly greater for the Paired group than the Random group on sessions 15–16 (see Fig. 1, center pair). Analysis revealed a significant main effect of Procedures, F(1, 43) = 15.22, P<.01, a significant main effect of Blocks, F(1, 43) = 12.83, P<.01, and a significant interaction effect between Procedures and Blocks, F(1, 43) = 6.29, P<.02. One-way ANOVA revealed that the observed difference between the means on sessions 6–7 was not significant, F(1, 43) = 1.93, P>.05, but the observed difference between the means on sessions 15–16 was significant, F(1, 43) = 16.43, P<.01. One-way repeated-measures ANOVA revealed that for the Paired group, GT CR Frequency was significantly higher during sessions 15–16 relative to sessions 6–7, F(1, 32) = 31.83, P<.01, but this was not the case for the Random group, F< 1.

3.1.3. Acquisition of total combined Pavlovian (sign-tracking+goal-tracking) CR performance

The mean number of total Pavlovian (ST + GT) CRs per session was significantly greater for the Paired group than the Random group on sessions 15–16 (see Fig. 1, right pair). Analysis revealed a significant main effect of Procedures, F(1, 43) = 12.38, P<.01, a significant main effect of Blocks, F(1, 43) = 6.21, P<.02, and a significant interaction effect between Procedures and Blocks, F(1, 43) = 6.89, P< .02. One-way ANOVA revealed that the observed difference between the means on sessions 6–7 was not significant, F(1, 43) = 2.72, P>.05, but the observed difference between the means on sessions 15–16 was significant, F(1,43) = 13.62, P< .01. One-way repeated-measures ANOVA revealed that for the Paired group, total Pavlovian (ST + GT) CRs per session was significantly higher during sessions 15–16 relative to sessions 6–7, F(1, 32) = 20.82, P<.01, but this was not the case for the Random group, F< 1.

Taken together, the above results suggest that, for ST CR, GT CR, and total combined Pavlovian CR performances, reliable acquisition did not occur during the early sessions (up through session 7), and more extended training (up to 16 sessions) was required to elevate mean lever CS-elicited responding in the Paired group to levels significantly above those observed in the Random control group.

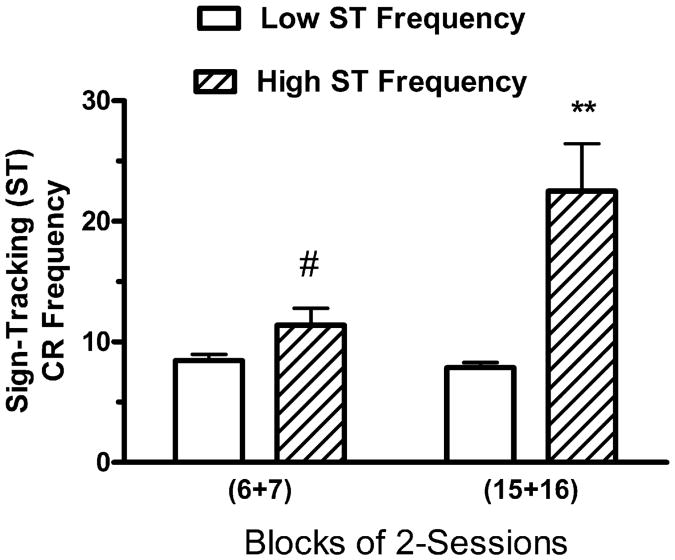

3.2. Stability of ST CR Frequency across sessions

There was considerable between-subjects variability in mean ST CR Frequency scores of the 33 Paired subjects during sessions 15–16 (mean = 9.64 ± 1.01, range = 3.5–30). A plot of the frequency of the 33 scores of the individual subjects revealed a unimodal distribution with a long and skewed tail, with a large break between the 2nd and 3rd highest scores and a smaller break between the 4th and 5th highest scores. To evaluate relationships between ST CR Frequency and other measures of CR performance, the 33 Paired subjects were divided into two groups for further analysis, based on their mean ST CR Frequency scores during sessions 15–16. The High ST Frequency group consisted of the 4 subjects (subjects 5,6,15, and 18) with the highest mean number of sign-tracking CRs during sessions 15–16 (mean = 22.50 ± 3.94), while the Low Sign-Tracking (GT) Frequency group consisted of the remaining 29 subjects (mean = 7.87 ± 0.42). Two-way ANOVA (see Fig. 2) with two levels of groups (High ST vs Low ST) and two levels of 2-session Blocks (6–7 and 15–16) revealed a significant main effect of Groups, F(1, 31) = 62.65, P<.01, a significant main effect of Blocks, F(1, 31) = 19.84, P< .01, and a significant interaction effect between Groups and Blocks, F(1, 31) = 24.24, P<.01. One-way ANOVA revealed that the group mean difference approached significance on sessions 6–7, F(1, 31) = 3.83, P< .06, and achieved significance on sessions 15–16, F(1, 31) = 70.83, P<.01. One-way repeated-measures ANOVA revealed that the increase in ST Frequency between the 2-session Blocks failed to achieve significance for the High ST group, F(1,3) = 6.66, .10>P>.05, or for the Low ST group, F< 1. Thus, the finding that for both groups, mean ST CR Frequency was not further elevated on sessions 15–16 relative to sessions 6–7, provides evidence of stability of ST CR Frequency at the level of the group means. It should be noted, on the other hand, that the low number of subjects in the High ST group may have reduced the chances of finding a significant difference between the two 2-session Blocks. The finding that the 4 Paired subjects that provided higher mean ST CRs during sessions 15–16 also provided marginally significantly higher mean ST CRs during sessions 6–7, provides evidence that the performance of high responders remains consistent across sessions.

Fig. 2.

Mean number of sign-tracking CRs per session during sessions 6–7 and during sessions 15–16 for the 4 subjects in the Paired group with the highest sign-tracking GT frequency scores and the 29 subjects in the Paired group with lower sign-tracking GT frequency scores during sessions 15–16. The vertical bars represent the standard error of the mean. The double asterisk (**) indicates that the groups differed at the .01 level of significance. The pound sign (#) indicates that the groups differed at the .06 level of significance.

The significant differences between the Paired and Random groups in ST, GT and Total CR performance on sessions 15–16 may have been largely due to the much higher scores contributed by the 4 subjects in the High ST group. Removing these 4 subjects from the Paired group had the effect of reducing the group means while at the same time reducing the SEMs of the remaining 29 subjects in the Paired group. Analyses revealed that the 29 subjects in the Low ST group differed significantly from the 12 subjects in the Random group on sessions 15–16 in ST CR Frequency, F(1,39) = 5.64, P< .03, in GT CR Frequency, F(1, 39) = 13.79, P<.01, and in Total (ST + GT) CR Frequency, F(1, 39) = 168.19, P<.01, indicating that on sessions 15–16 mean CR performances of the Low ST group were significantly elevated relative to the means of the CR-like performances of the pseudoconditioning control.

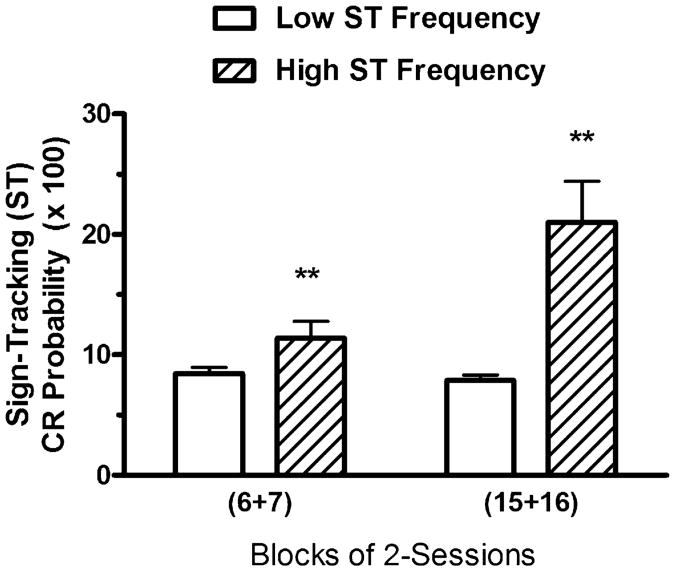

3.3. Relationship between ST CR Frequency and ST CR Probability

A subject's mean ST CR Frequency score may be elevated by performing many responses but only on a few trials, while providing no responses on the majority of trials. ST CR Probability, on the other hand, provides a measure of the percentage of trials on which the subject performs at least one ST CR. To determine if the subjects that performed more sign-tracking CRs also provided ST CRs on a higher percentage of the trials, the High ST (n = 4) and Low ST (n = 29) groups were evaluated for group mean differences in ST CR Probability. Two-way ANOVA (see Fig. 3) revealed a significant main effect of Groups, F(1, 31) = 56.57, P< .01, a significant main effect of Blocks, F(1, 31) = 14.72, P<.01, and a significant interaction effect between Groups and Blocks, F(1, 31) = 18.59, P<.01. One-way ANOVA revealed that the groups differed significantly on sessions 6–7, F(1, 31) = 7.22, P<.01, and on sessions 15–16, F(1, 31) = 18.71, P<.01. One-way repeated-measures ANOVA revealed that the increase in ST Probability between the 2-session Blocks was not significant for the High ST group, F(1, 3) = 5.39, P>.05, or for the Low ST group, F<1. The data suggest that the subjects that provided more ST CRs per session were also more likely to provide at least one ST CR on a higher percentage of the trials during each session, indicating substantial agreement between these two measures of ST CR performance.

Fig. 3.

Mean percent of trials per session with at least one sign-tracking ST CR per trial (ST CR Probability) during sessions 6–7 and during sessions 15–16 for the 4 subjects in the Paired group with the highest Sign-Tracking CR Frequency scores (“High ST Frequency”) and the 29 subjects in the Paired group with lower Sign-Tracking CR Frequency scores (“Low ST Frequency”) during sessions 15–16. There were 40 trials per session. The vertical bars represent the standard error of the mean. The double asterisk (**) indicates that the groups differed at the .01 level of significance.

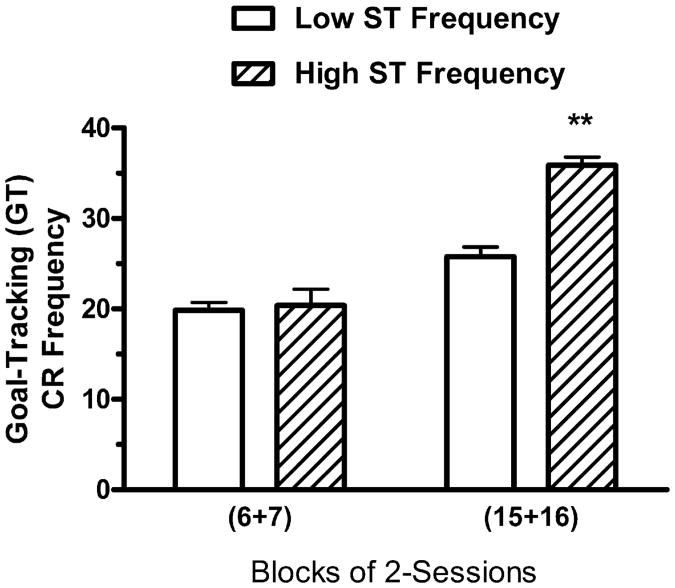

3.4. Relationship between ST CR Frequency and GT CR Frequency

To determine if the subjects that performed more sign-tracking CRs also performed more goal-tracking CRs, the High ST and Low ST groups were evaluated for differences in GT CR Frequency. Two-way ANOVA (see Fig. 4) revealed a significant main effect of Groups, F(1, 31) = 5.89, P<.03, a significant main effect of Blocks, F(1, 31) = 48.54, P<.01, and a significant interaction effect between Groups and Blocks, F(1,31) = 9.66, P < .01. One-way ANOVA revealed that the groups did not differ significantly on sessions 6–7, F< 1, but the groups did differ significantly on sessions 15–16, F(1,31) = 8.11, P<.01. The data suggest that, during sessions 15–16, the subjects that provided more ST CRs per session also provided more GT CRs per session, indicating that subjects that tended to respond to the insertion of the lever CS by approaching the location of the lever CS, were also more likely to respond to the insertion of the lever CS by approaching the location of the food trough where the food US was delivered.

Fig. 4.

Mean number of goal-tracking CRs per session during sessions 6–7 and during sessions 15–16 for the 4 subjects in the Paired group with the highest Sign-Tracking ST CR Frequency scores (“High ST Frequency”) and the 29 subjects in the Paired group with lower Sign-Tracking ST CR Frequency scores (“Low ST Frequency”) during sessions 15–16. The vertical bars represent the standard error of the mean. The double asterisk (**) indicates that the groups differed at the .01 level of significance.

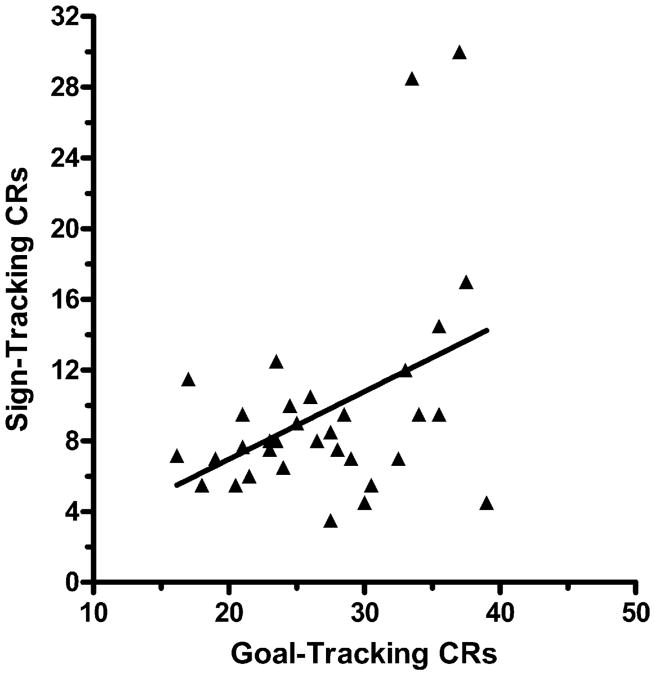

For the 33 subjects in the Paired group, there was a positive relationship between the mean number of sign-tracking CRs provided by a subject on sessions 15–16 and the mean number of goal-tracking CRs provided by that subject on sessions 15–16 (see Fig. 5). Pearson's product-moment correlation coefficient indicated that the observed positive relationship between these two forms of CR performance was significant, r(33) =+0.827, P<.01, r2 = .684, indicating that individual differences in the mean number of goal-tracking CRs on sessions 15–16 accounted for over two-thirds of the variance in the mean number of sign-tracking CRs on sessions 15–16. The significant correlation between ST CR Frequency and GT CR Frequency for the 33 subjects in the Paired group on sessions 15–16 may have been due to the much higher GT CR Frequency scores contributed by the 4 subjects in the High ST group. There is evidence that this may be the case, as Pearson's product-moment correlation coefficient on the scores of the 29 subjects in the Low ST group was not significant, r(29) =+0.211, P>.20, r2 = .045, indicating that individual differences in the mean number of goal-tracking CRs on sessions 15–16 for the Low ST group accounted for less than 5% of the variance in the mean number of sign-tracking CRs on sessions 15–16. These data reveal that the positive within-subjects covariation between ST CR Frequency and GT CR Frequency scores in the Paired group was due almost entirely to the scores provided by the 4 subjects who performed the most ST CRs. Thus, for the majority of the subjects in the Paired group, there was no evidence of a positive relationship between ST CR Frequency and GT CR Frequency.

Fig. 5.

Scatter-plot of the mean number of sign-tracking CRs and the mean number of goal-tracking CRs for all 33 subjects in the Paired group during sessions 15–16. Pearson's r = +0.827, P < .01.

Subjects were observed to perform the ST CR and the GT CR within the same trial. During sessions 15–16, for the Paired and Random groups, mean number of ST-GT sequences within a trial were 5.32 ±0.67 and 2.64 ±0.38 per session, respectively. During sessions 15–16, for the Paired and Random groups, mean number of GT-ST sequences within a trial were 2.92 ± 0.53 and 1.57 ±0.59 sequences per session. During sessions 15–16, for the Paired and Random groups, mean number of [total ST-GT sequences + GT-ST sequences] within a trial were 8.26 ± 1.12 and 4.21 ±0.87 sequences per session. One-way ANOVAs revealed that the Paired group performed more ST-GT sequences within a trial, F(1, 43) = 11.93, P<.01, more GT-ST sequences within a trial, F(1, 43) = 6.03, P<.03, and more [total ST-GT sequences + GT-ST sequences] within a trial, F(1, 43) = 9.31, P<.01, than did the Random group. For both the Paired and Random groups, the ST-GT within-trial sequence was performed approximately 40–45% more frequently than the GT-ST within-trial sequence. During sessions 15-16, for the 4 subjects (5, 6, 15, 18) in the High ST group and the 29 subjects in the Low ST group, mean number of [total ST-GT sequences + GT-ST sequences] within a trial were 21.50 and 5.29 per session, respectively, and this difference was significant, F(1, 31) = 9.31, P<.01. The elevated tendency to perform both types of CRs within a trial may contribute to the more highly positive relationship between ST CR Frequency and GT CR Frequency observed in the High ST group relative to the Low ST group.

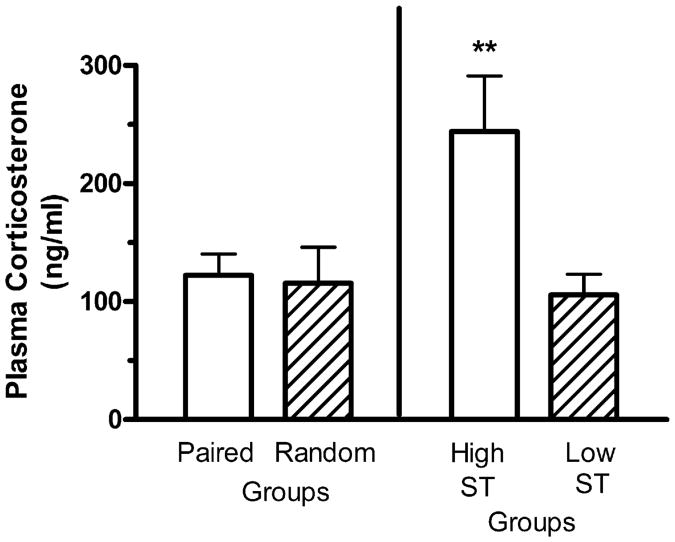

3.5. Plasma corticosterone level

Mean plasma corticosterone levels for the Paired and Random groups were 122.47 ± 17.91 ng/ml and 115.57 ± 30.54 ng/ml, respectively. Analysis revealed that this difference was not significant, F<1. Mean plasma corticosterone levels for the 4 subjects in the High ST CR Frequency group and for the 29 subjects in the Low ST CR Frequency group were 244.23 ± 46.77 ng/ml and 105.68 ± 17.37 ng/ml, respectively (see Fig. 6). One-way ANOVA revealed that this difference was significant, F(1, 31) = 7.71, P<.01.

Fig. 6.

Mean plasma corticosterone levels (ng/ml) for the Paired (n = 33) and Random (n = 12) groups, and for the two subgroupings of the Paired group, the High ST CR Frequency (n = 4) and the Low ST CR Frequency (n = 29) groups. The vertical bars represent the standard error of the mean. The double asterisk (**) indicates that the groups differed at the .01 level of significance.

4. Discussion

4.1. Sign-tracking (ST) CR performance

It should be noted that, on the majority of the trials, most of the mice in the Paired group did not physically contact or press the lever CS, thus it was necessary to employ video cameras to reliably detect ST CR performances, which were scored as lever CS-directed approach responses. These data provide the first report of lever CS-directed ST CR performance in mice induced by pairings of lever CS with food US. The finding that signaled food US presentations induced CS-directed Pavlovian ST CR performance is consistent with reports of Pavlovian ST of nose-poking CR performance in mice that were induced by pairings of light CS with food US [25,27]. Mean number of lever-directed ST CRs during sessions 15–16 was significantly elevated for the Paired group relative to the Random group (Fig. 1), indicating that acquisition of ST CR performance of lever CS-directed approach responding was induced in C57BL/6 mice by experience with pairings of lever CS with food US. That is, pseudoconditioning of ST CR-like responding due to experience with presentations of the lever CS perse or due to experience with presentations of the food US per se did not account for the acquisition of lever CS-directed approach performance of the Paired group. The present study is the first to assess pseudoconditioning of ST CR-like performance in mice; therefore, the present study provides the first report of evidence that the acquisition of ST CR performance of CS-directed approach responding in mice is due to experience with CS–US pairings [28].

The four Paired subjects that were high responders on sessions 15–16 also provided marginally significantly more ST CRs on sessions 6–7 (P<.06) relative to the 29 subjects that were low responders on sessions 15–16 (Fig. 2). These data are consistent with the hypothesis that the tendency for individual subjects to differ in the number of ST CRs performed during a session is stable across sessions. The stability of the ST CR Frequency measure across training sessions in individual subjects was reported in rats by Flagel et al. [5]. The present data are consistent with the earlier reports of this effect and extend the generality of the finding to ST CR performance in mice.

ST CR Frequency is a measure of the total number of ST CRs during a session. A single ST CR is recorded each time a subject approaches the location of the lever CS during the 5 s period that the lever CS is inserted into the chamber. A subject may, therefore, perform several ST CRs on a single trial, allowing the possibility that a High ST CR Frequency score may be obtained by a subject by responding with high frequency on relatively few trials. ST CR Probability is a measure of the percentage of trials on which the subject performs at least one ST CR. The 4 subjects that provided elevated mean ST CR Frequency during sessions 15–16 relative to the remaining 29 subjects, provided significantly elevated mean ST CR Probability during sessions 6–7 and during sessions 15–16 (Fig. 3), indicating that high responders on the ST CR Frequency measure were also high responders on the ST CR Probability measure, and this individual characteristic for High ST CR responders is stable across earlier (sessions 6–7) and later (sessions 15–16) stages of trials.

4.2. Goal-tracking (GT) CR performance

These data provide the first report showing that, in mice, GT CR performance is induced by Pavlovian conditioned approach procedures. Pairings of lever CS with food US induced the acquisition of food trough-directed GT CR performance during the CS–US inter-stimulus interval (i.e., the 5 s period of time between the insertion of the lever CS into the chamber and the delivery of the food US). The delivery of the food US coincided with the retraction of the lever from the chamber; thus, GT CR performance was measured only during the time that the lever CS was inserted into the chamber. Mean number of GT CRs during sessions 15–16 was significantly elevated for the Paired group relative to the Random group (Fig. 1), indicating that GT CR performance of food trough-directed approach responding was induced by experience with pairings of lever CS with food US. That is, pseudoconditioning of GT CR-like responding due to experience with presentations of the lever CS per se or due to experience with presentations of the food US perse did not account for the acquisition of food trough-directed approach performance of the Paired group. Previous studies of Pavlovian conditioned approach in mice did not assessed GT CR performance or pseudoconditioning of GT CR-like responding; therefore, the present study provides the first report of the acquisition of food trough-directed approach responding in mice induced by sign-tracking procedures, and, in addition, evidence that this responding is reliably induced by CS–US pairings.

The results also indicate that, for the Paired group, mean GT CR performance during sessions 15–16 was significantly elevated relative to sessions 6-7 (Fig. 1), indicating that the additional sessions of training further increased GT CR performance. On the other hand, for the Random group, the tendency to respond to the lever CS by approaching the vicinity of the food trough did not increase significantly between these 2-session Blocks (Fig. 1), indicating that the additional sessions of training did not further increase pseudoconditioning of GT CR-like responding. It should be noted that another method of evaluating the degree to which the increased GT CR performance observed during sessions 15–16 relative to sessions 6–7 maybe due to elevation of non-specific activity levels was employed in a sign-tracking study by Beckmann and Bardo [29]. These investigators measured general activity during the intertrial interval as well as during the trial and noted that the ratio of activity scores across sessions did not account for group differences in conditioned responding [29].

4.3. Total combined (ST+GT) CR performance

ST CRs and GT CRs are distinct forms of directed responding and both provide evidence of learning of the relationship between the lever CS and the food US. The acquisition of total combined (ST + GT) CR performance, therefore, provides an additional measure of the effects of associating the lever CS with the food US. The effects of total combined (ST + GT) CR performance may differ from the effects of either ST CR or GT CR performance because individual subjects may differ in their tendency to perform ST CRs or GT CRs [5] and, in addition, individual subjects may differ in their tendency to perform pseudoconditioning of ST CR-like responding or GT CR-like responding. Analysis revealed that C57BL/6 mice reliably acquired Pavlovian conditioning of lever CS-induced total combined (ST + GT) CR responding. Mean number of total combined (ST + GT) CRs during sessions 15–16 was significantly elevated for the Paired group relative to the Random group (Fig. 1), indicating that total combined (ST + GT) CR performance of directed responding was induced by experience with pairings of lever CS with food US. That is, pseudoconditioning of ST CR-like and GT CR-like responding due to experience with presentations of the lever CS per se or due to experience with presentations of the food US per se did not account for the acquisition of lever CS-induced directed responding observed in the Paired group.

The results also indicate that, for the Paired group, mean total combined (ST + GT) CR performance during sessions 15–16 was elevated relative to sessions 6–7 (Fig. 1), indicating that additional sessions of training induced further increases in total combined (ST + GT) CR performance. On the other hand, for the Random group, the tendency to respond to the lever CS by performing ST CR-like or GT CR-like responses did not increase significantly between sessions 6–7 and sessions 15–16 (Fig. 1), indicating that additional sessions of training did not further increase pseudoconditioning of ST CR-like and GT CR-like responding.

4.4. Relationship between ST CR Frequency and GT CR Frequency

It should be noted that the time spent during a trial performing either the ST CR or the GT CR would reduce the remaining time available during the trial to perform the other CR, and within-subjects, this displacement relationship between the two different CR forms would contribute to a negative relationship between them. To determine if subjects that performed more sign-tracking CRs also performed fewer goal-tracking CRs, the High ST (n = 4) and Low ST groups (n = 29) (see Table 1 for grouping based on ST) were evaluated for differences in GT CR Frequency. Analysis revealed that the High ST group provided significantly more GT CRs per session during sessions 15–16 than did the Low ST group (Fig. 4), indicating that the group of subjects that tended to respond more often to the insertion of the lever CS by approaching the location of the lever also tended to respond more often to the insertion of the lever CS by approaching the location of the food trough.

Table 1.

Rank ordering (highest to lowest) of the 33 subjects in the Paired group, based on the mean number of sign-tracking CRs during sessions 15 and 16. There was a natural break in the distribution of Sign-Tracking CR Frequency scores between the 4th and 5th ranked subjects (difference of 2.0), which was larger than the largest break in the distribution of Sign-Tracking CR Frequency scores for the lowest 29 subjects (difference of 1.0). The 4 higher ranked subjects (#6, 18, 5, and 15) were assigned to the High ST CR Frequency group, while the remaining 29 lower ranked subjects were assigned to the Low ST CR Frequency group.

| Rank | Subject number | Mean ST CR Frequency sessions 15–16 | Group |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 6 | 30 | High |

| 2 | 18 | 28.5 | High |

| 3 | 5 | 17 | High |

| 4 | 15 | 14.5 | High |

| 5 | 28 | 12.5 | Low |

| 6 | 24 | 12 | Low |

| 7 | 33 | 11.5 | Low |

| 8 | 22 | 10.5 | Low |

| 9 | 31 | 10 | Low |

| 10 | 2 | 9.5 | Low |

| 11 | 23 | 9.5 | Low |

| 12 | 29 | 9.5 | Low |

| 13 | 34 | 9.5 | Low |

| 14 | 4 | 9 | Low |

| 15 | 17 | 8.5 | Low |

| 16 | 12 | 8 | Low |

| 17 | 16 | 8 | Low |

| 18 | 25 | 8 | Low |

| 19 | 14 | 7.5 | Low |

| 20 | 9 | 7.5 | Low |

| 21 | 30 | 7.5 | Low |

| 22 | 13 | 7 | Low |

| 23 | 10 | 7 | Low |

| 24 | 26 | 7 | Low |

| 25 | 27 | 7 | Low |

| 26 | 3 | 6.5 | Low |

| 27 | 19 | 6 | Low |

| 28 | 1 | 5.5 | Low |

| 29 | 20 | 5.5 | Low |

| 30 | 32 | 5.5 | Low |

| 31 | 11 | 4.5 | Low |

| 32 | 21 | 4.5 | Low |

| 33 | 8 | 3.5 | Low |

To evaluate further the relationship between ST CR performance and GT CR performance, the ST CR Frequency score of each of the 33 mice was regressed against that subject's GT CR Frequency score. The significant positive correlation between these two measures of CR performance induced by pairings of the lever CS with the food US (Fig. 5) was consistent with the finding of a positive relationship between these measures that was observed in the between groups analysis (Fig. 4). Thus, the data suggest that if a mouse tended to respond to the insertion of the lever CS by performing many ST CRs, then that mouse was also likely to perform many GT CRs. On the other hand, if a mouse tended to respond to the insertion of the lever CS by performing fewer ST CRs, then that mouse was also likely to perform fewer GT CRs. This pattern of covariance between ST CRs and GT CRs within-subjects in mice is in contrast to the negative relationship between ST CRs and GT CRs that was observed in individual rats [5,6,15]. These investigators found that some rats that performed more ST CRs tended to perform fewer GT CRs (ST phenotype), and some rats that performed fewer ST CRs tended to perform more GT CRs (GT phenotype), and some rats performed comparable amounts of both ST and GT CRs. While these distinctive behavioral phenotypes in rats were not observed in the present study in mice, it should be noted that none of the mice in the Paired group consistently performed more ST CRs than GT CRs (see Fig. 5), and this maybe due to the specific aspects of the apparatus and procedures employed in the present study, which differ in many ways from those employed with rats. It should also be noted that this positive relationship between ST CR Frequency and GT Frequency was largely due to the 4 subjects in the High ST group, and that the effect was not significant in the 29 subjects in the Low ST group.

4.5. Plasma corticosterone

There was no significant difference in mean plasma corticosterone levels between the Paired and Random groups, and this is in contrast to several reports in rats showing elevated plasma corticosterone levels in Paired relative to Random groups [16–18]. On the other hand, for the Paired subjects, the High ST CR Frequency group provided significantly elevated plasma corticosterone levels relative to the Low ST CR Frequency group. The finding of a positive relationship between an individual subject's tendency for High ST CRs and an elevation of that subject's post-session plasma corticosterone level is consistent with reports in studies of Pavlovian conditioned approach employing rats [16,19]. It should be noted that ST CR performance has been proposed as an animal model of compulsive behavior in drug abuse [1–3,5,6,12], and, in rats, plasma corticosterone release has been proposed as a pathophysiological marker of vulnerability to alcohol abuse [21,22] and drug abuse [20]. The positive relationship between High ST CRs and elevated plasma corticosterone levels in mice is also consistent with the finding that individual rats predisposed to developing drug intake also exhibited greater sensitivity to the positive reinforcing effects of glucocorticoids [30].

The data reveal that at least some mice reacted to repeated lever CS–food US pairings by approaching the location of the lever CS. During operant reward training studies, mice trained to press a lever to obtain access to positive reinforcers (typically food or sweetened solutions), would experience repeated pairings of the lever with the reward [26,31–33]; therefore, Pavlovian ST CR performance may develop in some mice and thereby contribute to an increase in the probability of performing the operant lever-press response. In this way, Pavlovian sign-tracking CR performance may serve to increase the rate of operant lever-pressing in reward training procedures [34,35].

5. Conclusions

In C57BL/6 mice, Pavlovian pairings of lever CS with food US induced reliable acquisition of ST CR performance of lever CS-directed approach responses, and reliable acquisition of GT CR performance of food trough-directed approach responses. Paired procedures induced more ST CR performance and GT CR performance by sessions 15–16 than did Random procedures, indicating that the effects are not due to pseudoconditioning. In the Paired group, the subjects that performed more ST CRs also performed more GT CRs and expressed higher plasma corticosterone levels in trunk blood samples obtained following the last session, indicating a positive correlation between High ST CR vs GT CR and elevated plasma corticosterone. Such a relationship of positive covariance may reflect an influence on behavioral (Pavlovian CR performance) and physiological (stress hormone level) phenotypes from intrinsic factors, i.e., the underlying genetic contribution in mice.

Acknowledgments

We thank Nikyta Sharma for her technical assistance. This research was supported by NIH grants DA013471 and DA020555 and by funds from Rutgers University.

Abbreviations

- CS

conditioned stimulus

- US

unconditioned stimulus

- CR

conditioned response

- ST

sign-tracking

- GT

goal-tracking

References

- 1.Tomie A Cam. An animal learning model of excessive and compulsive implementassisted drug-taking in humans. Clin Psychol Rev. 1995;15:145–67. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tomie A. Locating reward cue at response manipulandum (CAM) induces symptoms of drug abuse. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 1996;20:505–35. doi: 10.1016/0149-7634(95)00023-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tomie A, Grimes KL, Pohorecky LA. Behavioral characteristics and neurobiological substrates shared by Pavlovian sign-tracking and drug abuse. Brain Res Rev. 2008;58:121–35. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2007.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Newlin DB. A comparison of drug conditioning and craving for alcohol and cocaine. Recent Dev Alcohol. 1992;10:147–64. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4899-1648-8_8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Flagel SB, Watson SJ, Robinson TE, Akil H. Individual differences in the propensity to approach signals vs goals promote different adaptations in the dopamine system of rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2007;191:599–607. doi: 10.1007/s00213-006-0535-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Flagel SB, Akil H, Robinson TE. Individual differences in the attribution of incentive salience to reward-related cues: Implications for addiction. Neuropharmacology. 2009;56(Suppl. 1):139–48. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2008.06.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tomie A, Brooks W, Zito B. Sign-tracking: the search for reward. In: Klein S, Mowrer R, editors. Contemporary learning theories: Pavlovian conditioning and the status of traditional learning theory. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1989. pp. 191–223. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boakes R. Performance on learning to associate a stimulus with positive reinforcement. In: Davis H, Hurwitz H, editors. Operant-Pavlovian interactions. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1977. pp. 67–92. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Flagel SB, Watson SJ, Robinson TE, Akil H. An animal model of individual differences in ‘conditionability’: relevance to psychopathology. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2006;31:S262–3. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Saunders BT, Robinson TE. Individual variation in the motivational properties of cocaine. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2011;36:1668–76. doi: 10.1038/npp.2011.48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Saunders BT, Robinson TE. A cocaine cue acts as an incentive stimulus in some but not others: implications for addiction. Biol Psychiatry. 2010;67:730–6. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.11.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Flagel SB, Watson SJ, Akil H, Robinson TE. Individual differences in the attribution of incentive salience to a reward-related cue: influence on cocaine sensitization. Behav Brain Res. 2008;186:48–56. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2007.07.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Robinson TE, Berridge KC. The neural basis of drug craving: an incentive-sensitization theory of addiction. Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 1993;18:247–91. doi: 10.1016/0165-0173(93)90013-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Berridge KC, Robinson TE. Parsing reward. Trends Neurosci. 2003;26:507–13. doi: 10.1016/S0166-2236(03)00233-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Flagel SB, Robinson TE, ClarkJJ, Clinton SM, Watson SJ, Seeman P, et al. An animal model of genetic vulnerability to behavioral disinhibition and responsiveness to reward-related cues: implications for addiction. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2010;35:388–400. doi: 10.1038/npp.2009.142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tomie A, SilbermanY, Williams K, Pohorecky LA. Pavlovianautoshaping procedures increase plasma corticosterone levels in rats. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2002;72:507–13. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(01)00781-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tomie A, Di Poce J, Aguado A, Janes A, Benjamin D, Pohorecky L. Effects of autoshaping procedures on3H-8-OH-DPAT-labeled 5-HT1a binding and 125I-LSD-labeled 5-HT2a binding in rat brain. Brain Res. 2003;975:167–78. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(03)02631-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tomie A, Tirado AD, Yu L, Pohorecky LA. Pavlovian autoshaping procedures increase plasma corticosterone and levels of norepinephrine and serotonin in prefrontal cortex in rats. Behav Brain Res. 2004;153:97–105. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2003.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tomie A, Aguado AS, Pohorecky LA, Benjamin D. Individual differences in Pavlovian autoshaping of lever pressing in rats predict stress-induced corticosterone release and mesolimbic levels of monoamines. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2000;65:509–17. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(99)00241-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Piazza PV, Le Moal ML. Pathophysiological basis of vulnerability to drug abuse: role of an interaction between stress, glucocorticoids, and dopaminergic neurons. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 1996;36:359–78. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pa.36.040196.002043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fahlke C, Engel JA, Eriksson CJ, Hård E, Söderpalm B. Involvement of corticosterone in the modulation of ethanol consumption in the rat. Alcohol. 1994;11:195–202. doi: 10.1016/0741-8329(94)90031-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fahlke C, Hård E, Thomasson R, Engel JA, Hansen S. Metyrapone-induced suppression of corticosterone synthesis reduces ethanol consumption in high-preferring rats. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1994;48:977–81. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(94)90208-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vanover KE, Barrett JE. An automated learning and memory model in mice: pharmacological and behavioral evaluation of an autoshaped response. Behav Pharmacol. 1998;9:273–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vanover KE, Harvey SC, Son T, Bradley SR, Kold H, Makhay M, et al. Pharmacological characterization of AC-90179 [2-(4-methoxyphenyl)-N-(4-methyl-benzyl)-N-(1-methyl-piperidin-4-yl)-acetamide hydrochloride]: a selective serotonin 2A receptor inverse agonist. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2004;310:943–51. doi: 10.1124/jpet.104.066688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Johnson JE, Pesek EF, Newland MC. High-rate operant behavior in two mouse strains: a response-bout analysis. Behav Processes. 2009;81:309–15. doi: 10.1016/j.beproc.2009.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pattij T, Broersen LM, Peter S, Olivier B. Impulsive-like behavior in differential-reinforcement-of-low-rate 36 s responding in mice depends on training history. Neurosci Lett. 2004;354:169–71. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2003.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Papachristos EB, Gallistel CR. Autoshaped head poking in the mouse: a quantitative analysis of the learning curve. J Exp Anal Behav. 2006;85:293–308. doi: 10.1901/jeab.2006.71-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rescorla RA. Pavlovian conditioning and its proper control procedures. Psychol Rev. 1967;74:71–80. doi: 10.1037/h0024109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Beckmann JS, Bardo MT. Environmental enrichment reduces attribution of incentive salience to a food-associated stimulus. Behav Brain Res. 2012;226:331–4. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2011.09.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Piazza PV, Le Moal M. Glucocorticoids as a biological substrate of reward: physiological and pathophysiological implications. Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 1997;25:359–72. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0173(97)00025-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McDonald MP, Wong R, Goldstein G, Weintraub B, Cheng SY, Crawley JN. Hyperactivity and learning deficits in transgenic mice bearing a human mutant thyroid hormone beta1 receptor gene. Learn Mem. 1998;5:289–301. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McKerchar TL, Zarcone TJ, Fowler SC. Differential acquisition of lever pressing in inbred and outbred mice: comparison of one-lever and two-lever procedures and correlation with differences in locomotor activity. J Exp Anal Behav. 2005;84:339–56. doi: 10.1901/jeab.2005.95-04. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shelton KL, Grant KA. Discriminative stimulus effects of ethanol in C57BL/6J and DBA/2J inbred mice. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2002;26:747–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hearst E, Jenkins HM. Monograph of the Psychonomic Society: Psychonomics. 1974. The stimulus-reinforcer relation and directed action. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schwartz B, Gamzu E. Pavlovian control of operant behavior: an analysis of autoshaping and its implications for operant conditioning. In: Honig WK, Staddon JER, editors. Handbook of operant behavior. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall; 1977. p. 53. [Google Scholar]