Abstract

Increasing evidence points to an association between major depressive disorders (MDDs) and diverse types of GABAergic deficits. Here we summarize clinical and preclinical evidence supporting a central and causal role of GABAergic deficits in the etiology of depressive disorders. Studies of depressed patients indicate that MDDs are accompanied by reduced brain concentration of the inhibitory neurotransmitter γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) as well as alterations in the subunit composition of the principal receptors (GABAA receptors) mediating GABAergic inhibition. In addition, there is abundant evidence that GABA plays a prominent role in the brain control of stress, the most important vulnerability factor in mood disorders. Furthermore, preclinical evidence suggests that currently used antidepressant drugs designed to alter monoaminergic transmission as well as non-pharmacologic therapies may ultimately act to counteract GABAergic deficits. In particular, GABAergic transmission plays an important role in the control of hippocampal neurogenesis and neural maturation, which are now established as cellular substrates of most if not all antidepressant therapies. Lastly, comparatively modest deficits in GABAergic transmission in GABAA-receptor-deficient mice are sufficient to cause behavioral, cognitive, neuroanatomical, and neuroendocrine phenotypes as well as antidepressant drug response characteristics expected of an animal model of MDD. The GABAergic hypothesis of MDD suggests that alterations in GABAergic transmission represent fundamentally important aspects of the etiological sequelae of major depressive disorders that are reversed by monoaminergic antidepressant drug action.

Introduction

Major depressive disorder (MDD) represents a complex neuropsychiatric syndrome with a lifetime prevalence of approximately 17% of the population worldwide 1. It exhibits high comorbidity with anxiety disorders, with 50–60% of depressed patients reporting a lifetime history of anxiety disorders, and many anxiety disorder patients showing a history of treatment for depression 2–9. Antidepressant drug (AD) treatments currently in use for both anxiety and depressive disorders are designed to target monoaminergic neurotransmission, and they have set the foundation for the so-called catecholamine 10,11 and serotonin 12,13 hypotheses of affective disorders. Collectively, these hypotheses posit that antidepressants act by increasing the extracellular concentration and function of monoamine transmitters in the forebrain 14 and, by extension, that mood disorders are caused by altered production, release, turnover, or function of monoamine transmitters or altered function of their receptors. There is, however, a growing consensus that altered monoaminergic transmission is insufficient to explain the etiology of depressive disorders 15 and that currently used antidepressants instead are modulating other neurochemical systems that have a more fundamental role in MDD 16.

A more recent hypothesis suggests that depressive disorders represent stress disorders. It is supported by a large body of epidemiological evidence showing that stress is a major vulnerability factor for mood disorders 17–19. This evidence includes altered HPA axis function in patients 20,21, polymorphisms in the CRH1 (corticotropin releasing hormone 1) receptor gene that are associated with mood disorders 22, as well as data from rodents showing that central administration of stress-related hormones can produce pathologies reminiscent of MDD, which are reversed by antidepressant drug treatment 23,24. An extension of the stress hypothesis puts forward that depressive disorders are caused by inadequate trophic support of neurons and impaired neural plasticity 25–28. None of the current hypotheses, however, have identified a unified molecular framework that is broadly implicated in the etiology of mood disorders and antidepressant drug mechanisms.

Here we summarize older but underreported and recent or emerging evidence in support of a fourth hypothesis that posits that etiological origins of mood disorders converge on genetic, epigenetic or stress-induced deficits in GABAergic transmission as a principal cause of MDDs, and that the therapeutic effects of currently used monoaminergic antidepressants involve downstream alterations in GABAergic transmission.

GABA and its receptors

GABAA receptors vs. GABAB receptors

GABA is the principal neurotransmitter mediating neural inhibition in the brain. GABAergic neurons are present throughout all levels of the neuraxis, represent between 20 and 40% of all neurons depending on brain region, and are known to balance and fine tune excitatory neurotransmission of various neuronal systems including the monoaminergic and cholinergic projections to the forebrain. GABA exerts its effects by activation of two entirely different classes of receptors, the ionotropic GABAA receptors (GABAARs) and the metabotropic GABABRs. GABAARs are known as key control elements of anxiety state based on the potent anxiolytic activity of benzodiazepines (BZs) that act as positive allosteric modulators of a major subset of GABAARs. Accumulating evidence described below points to marked alterations in GABAAR signaling in both anxiety and mood disorders. GABABRs are members of the G-protein coupled receptor family and they have been recently implicated in affective disorders based on altered anxiety- and depression-related behavioral measures in mice subject to pharmacological and genetic manipulations of these receptors. GABAB(1) and GABAB(2)R KO mice show behavior indicative of increased anxiety combined with an antidepressant phenotype 29,30. Consistent with these genetic studies, positive GABABR modulators show potential as anxiolytics, whereas antagonists have antidepressant-like effects in animal experiments 29. However, given the strong evidence for comorbidity of anxiety and depressive disorders, opposing actions of GABAB-directed ligands on anxiety- and depression-related measures are likely to limit the potential of GABABR-directed therapeutic approaches. Therefore, in this review we will focus on GABA signaling through GABAARs, the receptors that mediate the vast majority of GABA function.

Structure of GABAARs

Subunit composition

Structurally, GABAARs represent heteropentameric GABA-gated chloride channels that are assembled from subunits encoded by 19 different genes (α1–6, β1–3, γ1–3, δ, ε, θ, π, and ρ1–3). Different combination of these subunits give rise to a large number of structurally, functionally and pharmacologically distinct receptor subtypes, of which about 25 have been either definitely or tentatively identified 31. These can be roughly subdivided into i) postsynaptic and ii) extra- or perisynaptic subtypes, although some neurons also contain GABAARs at axon terminals. The postsynaptic GABAAR subtypes include mainly the α1βγ2, α2βγ2, and α3βγ2 receptors whose β subunit remain ill defined; they tend to be concentrated at synapses where they mediate phasic inhibitory synaptic currents in response to synaptically released GABA. The latter consist of α4βδ and α5βγ2 receptors in forebrain and α6βδ in cerebellum. They are located on somatodendritic membrane compartments away from the synaptic cleft and tonically activated by low ambient concentrations of GABA or GABA spilled over from synapses 31,32.

Functional dissociation of different subtypes of BZ-sensitive GABAARs

BZs act as positive allosteric modulators of GABAARs composed of α1βγ2, α2βγ2, α3βγ2, or α5βγ2 subunits. Using a combined molecular genetic and behavioral pharmacologic strategy these GABAAR subtypes have been assigned to different diazepam-sensitive behaviors based on the specific type of α subunit present 33,34. In particular, it was found that the broadly expressed α1βγ2 receptor subtype mediates sedative, anterograde amnesic, addictive and most of the anticonvulsant effects of diazepam 35–38. In contrast, α2βγ2 receptors control the anxiolytic and anti-hyperalgesic properties 39,40, and α2βγ2, α3βγ2, and α5βγ2 receptors together mediate the myorelaxant effects of diazepam 41,42. The α5βγ2 receptors are further important for normal hippocampus-dependent associative memory functions and for the development of tolerance to the sedative functions of diazepam 42–45. The prevalent distribution of α2βγ2 receptors in the cerebral cortex, hippocampus, and amygdala 46 and the role of this receptor subtype in anxiolysis is consistent with the established role of corticolimbic brain regions in the control of emotional states 47,48. Moreover, the identification of α1βγ2 receptorsin interneurons of the ventral tegmental area (VTA) as substrates for the addictive properties of BZs 37 suggests that functional deficits of these receptors may contribute to anhedonia as seen in GABAAR γ2 subunit-deficient mice 49 (see below). Functional deficits in α1βγ2 receptors can be predicted to increase GABA release by VTA interneurons and to enhance GABAergic inhibition of nearby dopaminergic neurons, and thereby to contribute to anhedonia as a core symptom of major depressive disorder.

BZ insensitive GABAARs

In contrast to most postsynaptic γ2-containing GABAARs, the extrasynaptic receptor subtypes composed of α4βδ subunits in the forebrain and α6βδ subunits in the cerebellum are insensitive to the GABA-potentiating effects of BZs, and they conduct a prominent tonic form of inhibition. Nevertheless, they exhibit high affinity for the imidazo-BZ Ro15-4513 and flumazenil, as well as the iodinated flumazenil derivative [123I]iomazenil 50–52. These receptors therefore are included along with BZ-sensitive GABAARs in autoradiographic and nuclear tomographic measurements using these ligands. The α4βδ receptors are of increasing interest as they are dynamically regulated by stress and other hormonal stimuli implicated in mood disorders.

Brain imaging studies suggest a role for altered GABAergic transmission in anxiety and depressive disorders

GABA deficits in depression

The strongest evidence that GABAergic deficits may contribute to depressive disorders is based on reduced GABA levels in plasma 53,54 and cerebrospinal fluid 55 or resected cortical tissue 56 of depressed patients. While initial findings were controversial 57 or lacked statistical significance 58, more recent assessments of GABA deficits in brain using proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy show dramatic reductions of GABA in the occipital cortex 59,60 and lower but still significant reductions in the anterior cingulate and dorsomedial/dorsolateral prefrontal cortex 61,62 of MDD patients. This neurochemical phenotype is consistent with a selective loss of calbindin positive GABAergic interneurons observed in the dorsal prefrontal cortex of depressed patients 63. Interestingly, GABA deficits are most pronounced in melancholic and treatment-resistant subtypes of depression (−50%) 56,60,64, while reductions in depressed patients not meeting criteria of melancholia 60 and in bipolar patients 65 are less severe (−20%).

GABAAR deficits in anxiety disorders

Reduced abundance of GABAAR binding sites suggests a role for GABAergic deficits in anxiety disorders. Positron Emission Tomography (PET) scanning using the BZ site antagonist 11C-flumazenil shows global reductions in GABAAR binding sites in patients suffering from panic attacks, with the most robust changes in ventral basal ganglia, orbitofrontal and temporal cortex 66, which are thought to control the experience of anxiety 67,68. Moreover, while flumazenil has no behavioral effect in healthy people, it precipitates panic attacks during symptom free episodes in panic patients, suggesting unusual inverse agonist properties 69. Analyses by Single Photon Emission Computed Tomography (SPECT) with a similar ligand ([123I]iomazenil) show widespread reductions in GABAAR binding sites in the superior frontal, temporal, and parietal cortex 70, left hippocampus and precuneus 71 of panic patients. Similar analyses have revealed GABAAR deficits in the temporal lobe of patients with generalized anxiety disorder 72 and medial prefrontal cortex of patients suffering from posttraumatic stress disorder 73. Collectively, the data suggest that different anxiety disorders involve GABAAR deficits in different brain regions.

Gene expression changes associated with major depressive disorder suggest altered expression and subunit composition of GABAARs

In contrast to anxiety disorders, the density of GABAAR [123I]iomazenil binding sites in brain of depressed subjects is largely unchanged 74. A notable exception is a single patient suffering from severe treatment-resistant anxious depression with panic attacks linked to a silent point mutation in the GABAAR β1 subunit gene 75. However, there is abundant evidence for a role of GABAARs in major depression based on altered expression of GABAAR subunit transcripts (Table 1). A genome wide screen for changes in transcript levels in the frontopolar cortex [Brodmann area (BA)10] of suicide victims that had suffered from various forms of depressive disorders has revealed reductions in the abundance of α1, α3, α4 and δ subunit mRNAs 76. Evidence for similarly discoordinated expression of GABAAR subunit transcripts is also available for other brain areas implicated in mood disorders 77. These studies did not differentiate among changes linked to depression, suicide, or suicide-associated distress, and thus need to be confirmed in a more representative cohort of patients and controls. Interestingly, the reduced expression of the α1 mRNA was associated with increased DNA methylation of transcriptional control regions of the GABRA1 gene and with upregulated expression of the DNA methyltransferase DNMT-3B, suggesting that GABRA1 gene expression is subject to epigenetic control 78.

Table 1.

Depression related alterations in expression of GABAAR subunit genes.

| mRNA | Patient sample | Broadman Area(s) | Direction of change | Type of analysis | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| α1 | Depressed suicides | 10,24 | Down | Microarray, QPCR | 76,82,382 |

| α3 | Depressed suicides | 10 | Down | QPCR | 76 |

| α4 | Depressed suicides | 8,9,10 | Down | Microarray, QPCR | 76,82 |

| α5 | BPD | 9,24,46 | Up | ISHH | 80 |

| Depressed suicides | 20,46 | Up | Microarray | 79,82 | |

| β1 | Depressed suicides | 24 | Up | Microarray | 82,382 |

| 46 | Down 1) | 79,82 | |||

| β2 | MDD | 21 | Down | Microarray | 380 |

| β3 | MDD | 9,46 | Up | Microarray | 80 |

| Depressed suicides | 6,10,38 | Up | 82 | ||

| δ | MDD | 9,46 | Up | Microarray | 80 |

| Depressed suicides | 6,44,46 | Up | Microarray | 79,82 | |

| Depressed suicides | 10 | Down | QPCR | 76 | |

| γ1 | Depressed suicides | 21,46 | Down 1) | Microarray, QPCR | 79,82 |

| γ2 | MDD | 9,46 | Up | Microarray | 80 |

| Depressed suicides | 20,472) | 79,82 | |||

| ρ1 | Depressed suicides | 21,44 | Down | Microarray, QPCR | 79,82 |

| GABABR1 | BPD | 9,46 | Up | Microarray | 80 |

| GABABR2 | Depressed suicides | 44,461) | Up | Microarray | 79 |

compared to non-depressed suicides.

significant in microarray, not significant by QPCR.

BA4, motor cortex; BA6, supplementary motor area (medial) and premotor cortex (lateral); BA9/44/46, dorsolateral prefrontal cortex; BA10, frontopolar cortex; BA20, Inferior temporal gyrus; BA21 middle temporal area; BA24, anterior cingulate cortex; BA38 temporopolar area; BA47, ventrolateral prefrontal cortex.

A comparison of postmortem brains of depressed vs. non-depressed suicide victims has revealed increased expression of the α5, γ2, and δ subunit mRNAs in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (BA44/46) 79. This is consistent with an earlier report showing upregulation of β3, γ2 and δ subunit mRNAs in similar brain regions (BA9, 46) of depressed patients who died from more diverse causes 80. This latter study has further identified selective upregulation of α5 mRNA in the anterior cingulate cortex (BA24), a critical component of the corticolimbic pathway affected in major depression 81. A comprehensive screen for gene expression changes in 17 cortical and subcortical brain regions from depression-related suicides found that genes that are involved in GABAergic transmission are among the most consistently changed 82. Among a total of 27 GABAergic probe sets differentially expressed in the frontal cortex or hippocampus no fewer than 19 involve genes that encode GABAAR subunits. GABAAR subunit genes are mostly upregulated in depression-related suicides, perhaps as a compensatory mechanism for low GABA levels associated with depression. Low levels of GABAAR gene expression among suicides that lack a history of depression suggest that elevated expression in depression-related suicides may in fact be depression-specific 82. These increases in GABAAR subunit mRNAs seem to contradict the aforementioned unaltered levels of GABAAR binding sites 74 in suicide brains. However, altered subunit mRNA levels do not necessarily have to result in changes in GABAAR binding sites, neither of which are representative of functional receptors present at the plasma membrane or at synapses. Discoordinated expression of GABAAR subunits might give rise to functionally distinct GABAAR subtypes that nevertheless bind [123I]iomazenil. Lastly, GABAARs are subject to phosphorylation, palmitoylation and ubiquitination, all of which regulate the cell surface expression and accumulation of GABAARs at synapses, as well as inhibitory synaptogenesis 83,84. These posttranslational modifications allow for modulation of GABAAR cell surface expression by environmental and physiological cues implicated in mood disorders. Accordingly, mutations in trafficking proteins that regulate the portion of GABAARs at synapses affect anxiety and mood-related behavior in both patients 85 and animal models 86,87.

Genetic evidence in support of GABAergic deficits in mood disorders

There is growing evidence that genetic polymorphisms in GABAAR subunit genes are involved in affective disorders. The Wellcome Trust Case Control Consortium has identified a strong association between bipolar disorder (BPD) and polymorphism in the GABRB1 gene coding for the β1 subunit of GABAARs 88. A follow-up study has confirmed this finding and extended it to associations with nucleotide polymorphisms in the GABRA4, GABRB3, GABRA5 and GABRR1 subunit genes 89. Notably, GABRB1, GABRA4, and GABRR1 are part of the same gene cluster on chromosome 4p12, together with GABRA2, while GABRA5 and GABRB3 are part of a cluster at 15q11-q13, which had previously been implicated in BPD 90. Associations between nucleotide polymorphisms and BPD further exist for GABRA3 91 and GABRB2 92, with the latter implicated in alternative splicing of the β2 subunit mRNA 93. For MDD, genetic associations have been described for GABRA5 94 and the gene cluster encoding GABRA1 95,96, GABRA6 and GABRG2 96. Although not all studies have found this latter association 97, this same gene cluster is linked to depression-related behavior also in mice 98. Finally, there is recent evidence for a male-specific association between non-coding genetic polymorphisms of the GABRD gene and childhood-onset mood disorders 99. In summary, the data suggest that GABAergic deficit can lead to mood disorders but also demonstrate that genetic polymorphisms at the level of GABAAR subunit genes account for at most a small percentage of mood disorders, and that environmental and remote genetic triggers of GABAergic deficits may be more important.

Modulation of GABAARs by stress: a major risk factor of depressive disorders

Effects of early life stress

Stress represents the most important vulnerability factor for MDD and related neuropsychiatric disorders, both in the developing 100–104 and adult nervous system 105. There is a growing body of preclinical evidence that much of this vulnerability may be due to stress-induced impairment of GABAergic transmission. For example, maternal separation stress of rats during the first postnatal weeks leads to increased neophobia and acoustic startle responses in adulthood, and this phenotype is associated with reduced expression of BZ-sensitive GABAARs in the frontal cortex, amygdala, locus coeruleus and the n. tractus solitarius106. The level of maternal care measured in the form of pup licking in rodents is positively correlated with GABAAR mRNA expression and inversely related to behavioral stress reactivity in adulthood 107. Analyses of GABAAR γ2-deficient mice 49,108 (further discussed below) suggest that modest reductions in GABAAR function during development are not just correlated with anxiety- and depression-related behavior in adulthood, but that they can be causal.

Effects of stress in adulthood

In addition to early life stress effects on GABAAR expression in the mature brain, there is an extensive literature on stress-induced changes in the expression and function of GABAARs in the adult brain. The exact consequences of acute stress on GABAAR expression in rodents appear to depend on the type of stress protocol, sex and brain region(s) analyzed 109. Most relevant in the context of this review, however, are unpredictable chronic forms of stress that are suitable to model depressive-like symptoms in animal models 110,111. The prevalent effect of chronic stress in the cerebral cortex is reduced abundance and function of GABAARs 112. By contrast, the effects of chronic stress hormone exposure in the hippocampus are uneven and subunit- and layer-specific 113,114. In particular, expression of α4βδ receptors is subject to prominent chronic stress-induced augmentation in granule and pyramidal cell neurons of the hippocampus 115,116. This chronic effect is thought to alter sensitivity of the brain to acute stress-associated increases in neuroactive steroids, as discussed further below.

GABAergic control of HPA axis

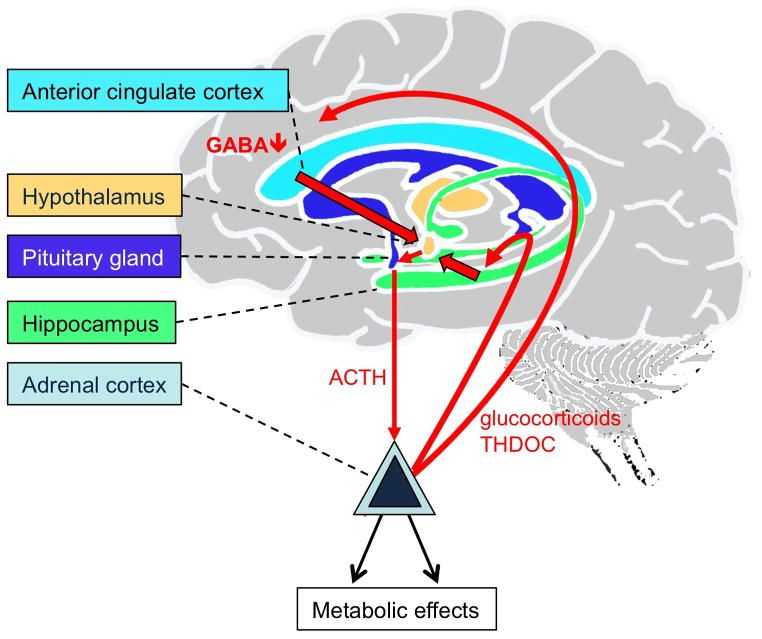

Increased secretion of glucocorticoids and aberrant function of the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis are well-replicated findings in a major subset of patients suffering from severe forms of depressive disorders, especially melancholic depression 19,21,117–120 (Figure 1). The paraventricular nucleus (PVN) of the hypothalamus, which is the source of corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) that dictates HPA axis responses to stress 121–123, is subject to GABAergic inhibitory control by frontal cortex 122,124 and ventral hippocampus 125. They are activated along with the PVN in response to acute emotional stress 126 and represent major sites of vulnerability to stress 127–130.

Figure 1. HPA axis hyperactivation by frontocortical and hippocampal deficits in GABAergic inhibition.

The GABAergic deficit hypothesis of MDD presented here suggests that local GABAergic deficits in hippocampus and frontal cortex due to reduced GABA release, uncoordinated GABAAR subunit gene expression or anomalous signaling mechanisms that affect GABAAR accumulation at the plasma membrane lead to local hyperexcitability, which is relayed by projections (In the case of frontal cortex through the BNST 144) to the PVN of the hypothalamus. In the hippocampus such local GABAergic deficits may involve loss of parvalbumin positive interneurons 131, reduced GABAergic synaptic inhibition 130 and reduced maturation and survival of adult-born granule cells 108, which is sufficient to activate the HPA axis 135. Cortical deficits in GABAergic inhibition include reduced GABA levels in patients 61,62. In addition, GABAergic deficits may be induced by chronic stress, which down-regulates the expression and function of GABAARs in the frontal cortex 112. Hyperexcitability of the cortex and hippocampus is relayed by projections to the PVN. Local GABAergic inhibition of PVN neurons may be independently compromised by a stress-induced shift in the neural Cl− reversal potential 147. The ensuing excessive release of CRH from the PVN results in increased release of ACTH from the anterior pituitary, which promotes the release of glucocorticoids, thereby closing a positive feedback loop that amplifies cortical and hippocampal GABAergic deficits. Adrenal neurosteroids normally potentiate GABA-mediated activation of GABAARs on dentate gyrus granule cells 168,381. Moreover THDOC upregulates the expression of α4βδ receptors in hippocampal granule cells 115. However, in CA1 pyramidal cells of the hippocampus the same neurosteroids facilitate GABA-induced desensitization of α4βδ receptors 153, which increases neural excitability 168.

In contrast to acute stress, which enhances GABAergic synaptic transmission in the ventral hippocampus 130, chronic stress causes reductions in GABAergic synaptic currents due to the selective loss of hippocampal parvalbumin-positive interneurons 131. This effect has been attributed to glucocorticoids acting on a membrane-bound, ill-defined receptor that evokes NO release from hippocampal pyramidal cells 131. Even modest chronic deficits in GABAergic transmission in GABAAR γ2+/− mice impair the survival of adult-born hippocampal neurons 108, an effect that may explain hippocampal volume reductions seen in chronically depressed patients 132–134 (see also below). Blocking hippocampal neurogenesis in turn is sufficient to increase HPA axis activity 135. Thus, projections from the ventral hippocampus via the lateral septum 128,136 to the hypothalamus link hippocampal neuropathology to hyperactivity of the HPA axis and aberrant stress reactivity, which may sustain or even amplify hippocampal neuropathology.

Similar to the hippocampus, the dorsomedial and dorsolateral prefrontal and the anterior and subgenual cingulate cortices represent substrates of stress-related psychiatric illness associated with cognitive and affective symptoms of MDD 81,129,137–139. The deficits in cortical GABA concentrations 61,62 and altered expression of GABAAR subunit genes (Table 1) indicate that this phenotype involves reduced GABAergic function. In addition, cortical GABAergic inhibition is impaired by stress-induced signaling pathways, as indicated by drastic CRH-induced, serotonin-mediated desensitization of GABAergic inhibitory synaptic currents recorded from cortical slices 140. Tracing experiments show that GABAergic neurons of the anterior bed nucleus of the stria terminalis (BNST) serve to relay inhibitory control by the medial prefrontal cortex to the PVN 141–144. Moreover, mice with genetically-induced cortex/hippocampus-restricted GABAAR deficits exhibit chronically elevated HPA axis activity 49. Thus, local cortical deficits in GABAergic inhibition and correspondingly increased neural excitability lead to increased activity of the PVN, even if the initially causal deficit is limited to extra-hypothalamic circuits (see also below).

In addition to remote inhibition of the hypothalamus by cortical and hippocampal GABAergic circuits, CRH-producing neurons of the PVN themselves are subject to local GABAergic inhibitory control that is regulated by stress 145. Chronic mild stress of rats results in a marked reduction of the frequency but unaltered amplitude of GABAergic inhibitory synaptic currents recorded from PVN neurons, suggesting presynaptic deficits in GABA release 146. However, postsynaptic GABAergic function of PVN neurons is also impaired, as indicated by stress-induced down-regulation of the K+-Cl− co-transporter KCC2. The ensuing depolarizing shift of the chloride reversal membrane potential renders GABA inputs ineffective, thereby leading to increased excitability of PVN neurons 147. Increased CRH release by PVN neurons leads to increased release of adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) by the anterior pituitary gland and systemically elevated basal cortisol levels (corticosterone in rodents) and other stress hormones, which are well-replicated findings in prominent subsets of patients suffering from severe forms of depressive disorders 19,117–120,148 (Figure 1).

GABAAR modulation by neurosteroids

Stress is known to affect GABAergic inhibition at least in part through stress-induced release of endogenous neuroactive steroids that act as allosteric modulators of GABAARs. In particular, 3α,5α-tetrahydroprogesterone (THP, also known as [allo]pregnanolone) and 3α,21-dihydroxy-5α-pregnan-20-one (THDOC, [allo]tetrahydrodeoxycorticosterone) are rapidly induced (4 – 20 fold) by stress 149 and known to act as high-affinity modulators of extrasynaptic α4βδ GABAARs 150–152. THP either increases (in dentate gyrus granule cells) or reduces (in CA1 pyramidal cells) α4βδ receptor-mediated tonic GABAergic inhibition, due to cell type-specific differences in chloride homeostasis and steroid-induced receptor desensitization, which depends on the direction of the chloride gradient 152,153. Preclinical and clinical data indicate that plasma concentrations of THP and THDOC are reduced and increased, respectively in depressed patients 154–157 and normalized by certain ADs (see below), which points to a role for neurosteroid synthesis in the pathology of depressive disorders. While THP is an endogenous metabolite of ovarian/adrenal progesterone and also produced in brain, THDOC is derived exclusively from adrenal sources 149,158,159. Normally, α4βδ receptors are readily detectable only in dentate gyrus granule cells, most of the thalamus, striatum, pons, and in the outer layers of cerebral cortex 160. However, prominent tonic inhibitory currents with a pharmacological profile of δ-containing GABAARs in PVN neurons 161 and attenuation of ACTH and corticosterone release by THP and THDOC 162,163 indicate that α4βδ receptors also contribute to the inhibitory control of HPA axis activity in the PVN.

The expression of α4βδ receptors is dynamically regulated

In CA1 pyramidal cells the accumulation of these receptors is strongly induced upon progesterone withdrawal 164–166, at puberty 167,168 and during pregnancy 166. In dentate granule cells the abundance of α4βδ receptors is subject to dynamic fluctuations across the ovarian cycle 169, during pregnancy 166,170,171, and induced by stress 115. Thus, aberrant homeostatic regulation of neurosteroid synthesis together with cell type-specific effects on expression and function of α4βδ receptors is implicated in the etiology of stress-associated mood disorders, premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMDD) and postpartum depression (PPD) 150,151,172,173 (see below).

Pharmacologic evidence in support of a role of GABAergictransmission in depressive disorders

Antidepressant efficacy of benzodiazepines

A possible role of GABAAR dysregulation in mood disorders has been controversial in part due to lack of a consensus about whether BZs are therapeutically effective for the treatment of depression 61. However, the limited use or efficacy of BZs in AD therapies should not be taken as evidence that GABAergic deficits are not involved in the etiology of MDD. Early studies concluded that standard tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) are overwhelmingly superior to BZs, although the two classes of drugs were initially prescribed for depression almost interchangeably 174. Indeed, some early studies reported antidepressant efficacy of BZs that was comparable to that of standard antidepressants 175–177, with some studies reporting more rapid therapeutic onset 178,179 or greater efficacy of BZs 180. More recent meta-analyses of clinical data have concluded that antidepressant efficacy of BZs is limited to the triazolo-BZ alprazolam, with classical BZs being ineffective beyond their established role as anxiolytics 181,182. Alprazolam has been rated as equivalent or superior to TCAs with respect to anxiety and sleep indices of depression, equivalent with respect to improving anergia, psychomotor retardation and anhedonia, but inferior in relieving depressed mood 181,182. The most obvious limitations to therapeutic efficacy of BZs are due to rapid development of tolerance, the high risk for developing dependence, the moderate abuse potential, and ultimately the danger of withdrawal symptoms 183,184. At the cellular level, BZs may limit the proliferation of progenitors of adult-born hippocampal neurons, which would limit the effect these drugs can have on immature neurons, which act as a substrate of antidepressant drug action (see below). Nevertheless, BZs are often used in combination with standard antidepressants, even today, both for initial treatment and maintenance therapy 185,186, which suggests beneficial effects. Encouragingly, the sedative hypnotic agent eszopiclone, which acts as a positive allosteric agonist similar to BZs but selectively on α2βγ2 and α3βγ2 subtypes of GABAARs, shows significant promise as an antidepressant in patients suffering from insomnia 187–189.

GABAergic mechanisms of monoaminergic antidepressants

With the exception of some BZs mentioned above, currently used antidepressants exclusively target monoamine transmitters. They are designed to block the reuptake of extracellular serotonin (selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, SSRIs), norepinephrine or, to a lesser extent, dopamine, or they unspecifically inhibit the intracellular degradation of monoamine transmitters. AD-induced increases in extracellular monoamines are thought to result in slow neurochemical, transcriptional, translational, posttranslational, and epigenetic adaptations that underlie therapeutically effective neural plasticity 28. However, the receptors that mediate the functionally relevant neural adaptations of drug-induced increases in monoamine transmitters and their cellular localization have not been conclusively determined. Indeed, there is evidence that antidepressants may activate G-protein signaling independently of increased monoamine transmitters 190,191. Even so, the antidepressant effects of serotonin in forebrain are thought to involve 5-HT1AR-mediated hyperpolarization of pyramidal cells 192 and 5-HT1B/5-HT2/5-HT3/5-HT4R-mediated excitation of GABAergic interneurons 193–197. In support of this conclusion, the 5-HTR trafficking factor P11/S100A10 interacts with and regulates the cell surface expression and function of 5-HT1B 198 and 5-HT4Rs 199. Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) and chronic treatment with imipramine result in upregulation of P11 mRNA and protein selectively in the forebrain 198. Moreover, P11 is required for normal antidepressant and neurogenic effects of fluoxetine 197. Importantly, P11 is selectively expressed in several classes of hippocampal GABAergic interneurons but absent in granule cell precursors 197. Thus, the effects of fluoxetine, imipramine and ECT may have in common that they involve increased excitability of GABAergic interneurons, which, in turn, can be predicted to increase GABAergic activation of hippocampal granule cell precursors 200,201. Whereas GABAergic input to mature neurons is mostly hyperpolarizing, the depolarizing action of GABA on immature granule cells is implicated in the mechanism of monoaminergic AD action (see below).

AD-induced potentiation of GABA release as a mechanism underlying AD effects is congruent with chronic SSRI-mediated increases in cortical GABA concentrations observed in patients 202 and healthy volunteers 203. However, these reports seem at odds with fluoxetine effects on GABA signaling in the visual cortex of rats 204. Chronic fluoxetine-induced reductions in cortical GABA concentrations and correspondingly reduced GABAergic inhibition have been shown to reactivate ocular dominance plasticity in the adult brain and to promote the recovery of visual functions in adult amblyopic animals 204. It remains to be seen whether such effects can be replicated with other antidepressants and whether they extend to brain areas implicated in mood disorders.

Similar to SSRIs, TCAs that increase the extracellular concentration of noradrenalin as well as 5-HT are likely to act in part by modulating GABAergic transmission. Noradrenergic innervation of GABAergic interneurons increases GABAergic transmission in diverse forebrain regions as shown for the frontal 205, sensorimotor 206 and entorhinal cortices 207, the CA1 hippocampus 208 and the basolateral amygdala 209. The selective norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor reboxetine has complex brain region-specific effects on expression of interneuronal glutamic acid decarboxylase 67 (GAD67), the principal enzyme involved in the synthesis of GABA 210. Immunostaining for GAD67 in brain of medication free depressed suicides is significantly reduced, whereas brain of a different cohort of depressed suicide victims who had been treated with SSRIs or TCAs showed normal levels of GAD67 211. Collectively, the data suggest that norepinephrine and serotonin reuptake inhibitors have in common that they potentiate GABAergic transmission.

Direct effects of ADs on GABAARs

In addition to their principal effects on monoamine transporters and receptors, many if not all antidepressants can directly act on other targets that contribute to therapeutic efficacy, undesirable side effects, or toxicity upon overdose. For example, fluoxetine (1–10 μM) has direct off-target effects at nicotinic acetylcholine 212,213 and 5-HT3 receptors 214–216 as well as diverse Cl− 217, voltage-gated Ca2+ and K+ channels 218–223. Importantly, therapeutically relevant concentrations of fluoxetine and its metabolite norfluoxetine act as potent positive allosteric modulators of GABAARs in vitro when tested on receptors expressed in heterologous cells 224 and in cultured neurons 225. This effect may not only contribute to antidepressant efficacy but also explain the unique anticonvulsant properties of fluoxetine in patients 226.

AD-induced potentiation of GABAergic transmission by neurosteroids

Low concentrations of chronically applied fluoxetine or its active metabolite norfluoxetine and their relatives (i.e. paroxetine, fluvoxamine, sertraline) have been shown to increase the plasma or cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) concentrations of THP 155–157,227–230. This effect is observed at concentrations fifty-times lower than the concentration that affects 5-HT uptake. Thus, THP appears to contribute to the anxiolytic function of SSRIs 231. The behavioral effects of THP are independent of an increase in serotonin but are attenuated by bicucullin 232, which shows that they involve potentiation of GABAARs. In vitro experiments with fluoxetine, sertraline, and paroxetine suggest that SSRI-induced increases in THP are due to direct drug effects on enzymes involved in THP synthesis 233. Hippocampal administration of THP in rats has anxiolytic and antidepressant-like behavioral effects and is associated with increased expression of the γ2 subunit mRNA of GABAARs 234. In addition to genomic effects, THP acts as a potent positive allosteric modulator of mainly α1/4/6βδ subtypes of GABAARs 153,235–239. These extrasynaptic GABAARs are of increasing interest in the context of mood disorders as they are subject to dynamic genomic and hormonal regulation during puberty 167,168, the ovarian cycle 169, pregnancy 170, as well as in response to stress 115,240.

The cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) and plasma concentrations of THP are reduced compared to normal controls in drug-free depressed patients 154–157, by social isolation stress in rats 241, and in the olfactory bulbectomy model of depression of rats 229. Moreover, SSRIs normalize THP deficits in patients 154–156 as well as in bulbectomized rats 150,229,242,243. Plasma levels of THP are also elevated following partial sleep deprivation 244, which has antidepressant effects 245. In contrast to THP, plasma concentrations of THDOC are increased in patients and reduced by fluoxetine 157. Unlike SSRIs or sleep deprivation, the TCA imipramine 227,233, repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation 246 and ECT 247 do not affect THP plasma concentrations, suggesting that THP is not universally involved in antidepressant mechanisms. These measurements, however, have yet to be repeated in brain to be conclusive.

In addition to drug therapies, cognitive behavioral therapy 248 and ECT 249 ameliorate cortical GABA deficits in patients. ECT is thought to further enhance GABAergic transmission through an increase in cortical expression of GABAARs 250. Lastly, noradrenergic and serotonergic neurons in the locus coeruleus and raphe nucleus, respectively, are subject to GABAergic control 251,252. In particular, reduced GABAergic inhibition of serotonergic neurons is a developmental risk factor for anxiety and mood disorders, as evidenced by anxiety-and depression-related behavior of mice in which the serotonin transporter was inactivated genetically (KO mice) 253–255 or pharmacologically 256 in early life. The collective information on the mechanisms of different antidepressant therapies and their effects on GABA release, neurosteroids synthesis and GABAAR expression and function indicate that enhancing GABAergic transmission lies at the core of both pharmacological and non-pharmacological antidepressant therapies.

GABAergic control of neurogenesis, a target of antidepressant drug treatment

Mechanisms that regulate the production, maturation and survival of adult-born granule cell in the hippocampus (dentate gyrus) have become a focus of research on mood disorders since it was shown in rodents that these processes are enhanced by ADs 257–260 and required for many of the AD-induced behavioral responses 259,261–266. Conversely, deficits in neurogenesis are a hallmark of genetic and stress-induced animal models of depression 108,133,267–269 and thought to underlie hippocampal atrophy observed in chronically depressed patients 24,26,27,105,139,270–277. The production of adult-born granule cells is unaffected by serotonin depletion 278,279. Moreover, noradrenaline is dispensable for normal maturation of these neurons, although it is required for normal proliferation of neural precursor cells 278,280. Lastly, we are unaware of any conclusive evidence that monoamine transmitter receptors are expressed on replicating neural progenitors or on immature neurons. The collective evidence suggests that deficits in monoaminergic neurotransmitter systems are unlikely to represent principal culprits of anxiety- and depression-related deficits in hippocampal neurogenesis. By contrast, GABAergic signaling through GABAARs has emerged as an essential mechanism that controls proliferation, maturation and survival not only of adult-born neurons in the hippocampus 200,201 but also for analogous processes in the postnatal subventricular zone of rodents that replenishes interneurons of the olfactory bulb 281,282 and for embryonic neural progenitors that give rise to neurons of the neocortex 283 [for review see 284,285].

GABAergic mechanisms that control adult hippocampal neurogenesis

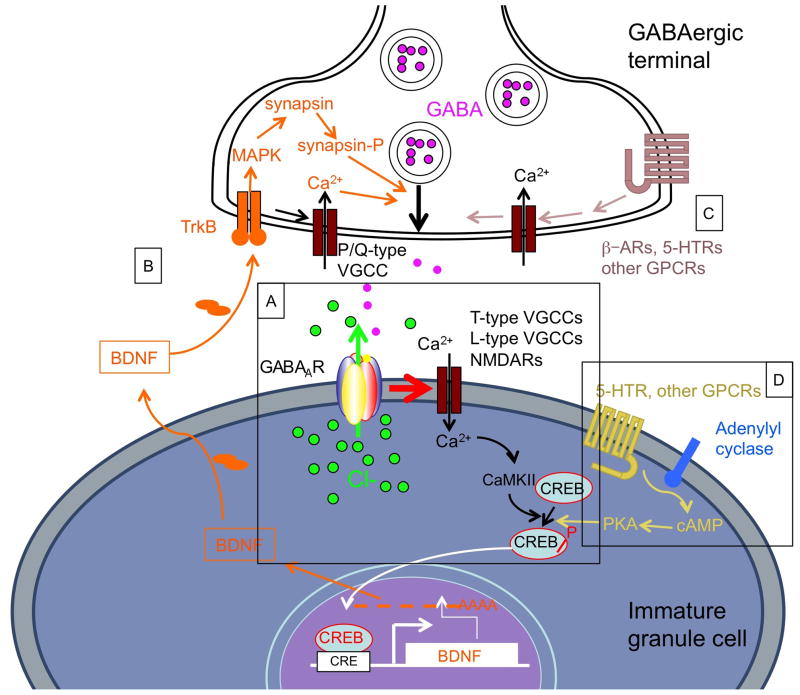

GABAARs have mainly hyperpolarizing effects on the membrane potential of mature neurons. By contrast, GABA-mediated activation of GABAARs is depolarizing and excitatory in proliferating neural progenitors and immature postmitotic neurons 281,283,285–288 (Figure 2). The transition from GABAAR-mediated depolarization to hyperpolarization during the maturation of neurons is triggered by a developmental switch in gene expression of the two Cl− transporters NKCC1 and KCC2, which leads to a gradual shift in the membrane reversal potential of chloride to more negative values. The negative shift of the Cl− reversal potential in turn changes the direction of GABAAR-mediated currents from depolarizing (inward) in neural progenitors and immature neurons to mostly hyperpolarizing (outward) in mature neurons. Importantly, this switch is essential for normal structural and functional maturation and network integration of adult-born granule cells201. Short-term enhancement of GABAAR function with barbiturates accelerates the differentiation of proliferating neural progenitor cells and thereby depletes the pool of dividing cells that represents the source of adult born neurons 200,281. In agreement with negative effects of GABAergic inputs on proliferation of new hippocampal neurons, co-administration of fluoxetine with the BZ diazepam negates the effect on proliferation observed with fluoxetine alone 289. In addition to these effects on proliferating progenitors, GABA-mediated excitation of postmitotic immature neurons results in activation of low threshold T-type Ca2+ channels 290, higher threshold L-type Ca2+-channels 291–294, and NMDARs 295. The ensuing increase in intracellular Ca2+ results in activation of diverse kinases 296 (e.g. CaMKII, PKC, PKA), all of which can phosphorylate Ser133 of the DNA-binding transcription factor CREB (cAMP response element binding protein) and promote the dendritic maturation and survival of these neurons 258,297–299 (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Mechanisms of AD action in immature neurons of the dentate gyrus involving GABAergic transmission.

A. GABAARs in immature neurons conduct an inward current (Cl ions moving out of the cell) due to the more positive Cl− reversal potential in these cells. The ensuing membrane depolarization facilitates Ca2+ entry through V-gated ion channels such as the T-type and L-type voltage gated Ca2+ channels, and in more mature neurons also NMDARs. The cytoplasmic increase in Ca2+ results in an increased activity of protein kinases (CaMKII, PKC, PKA, others) that phosphorylate CREB on Ser133. Phosphorylated CREB translocates to the nucleus where it activates a number of target genes including that encoding BDNF. B. Increased production and release of BDNF acts on GABAergic terminals and promotes the release of GABA by TrkB/MAPK-mediated phosphorylation of synapsin and mobilization of GABA-containing vesicles, and by activation of P/Q-type voltage-gated Ca2+ channels that activate the neurotransmitter release machinery. C, Monoamine transmitters, which are presumed to be elevated in the hippocampus upon AD treatment, act on presynaptic β-adrenergic and 5-HTRs that activate voltage-gated Ca2+ channels on terminals and soma of GABAergic interneurons. D, Some effects of monoamine transmitters may be mediated by GPCRs on granule cells. However, the expression of these receptors on neural progenitors and immature granule cells has not been documented.

CREB mediates GABAergic control of antidepressant-induced neurogenesis

CREB has a well-established role in learning- and memory-related synaptic plasticity 300 and is involved in hippocampus-mediated AD responses 27,301,302 and the production, maturation and survival of adult-born hippocampal neurons 258,297,299. Consistent with a role of CREB in MDD, CREB expression is down-regulated in brain of depressed (but not schizophrenic) patients studied at autopsy and increased as part of the AD response 303. All evidence suggests that the effects of ADs on CREB activation and maturation and survival of hippocampal neurons are indirect and downstream of increased GABA signaling via GABAARs 299 (Figure 1). Concurrent activation of CREB and increased hippocampal neurogenesis are hallmarks of all currently used antidepressants 257,304, suggesting that their mechanisms of action involve enhancement of GABAergic input to immature granule cells.

Among the transcriptional target genes of CREB, the brain derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) is of special interest 305–307. BDNF is reduced in serum of depressed 308,309 and bipolar patients 310,311 and in the dentate gyrus of chronically stressed rats 312. Conversely, BDNF is induced upon chronic treatment with diverse classes of ADs in the hippocampus of rats 313,314 and patients 315, and it is effective as an antidepressant upon central administration in rodents 316–319. BDNF and its receptor TrkB are essential for normal anxiety-related behavior and for AD behavioral effects in mice 264,320,321 as well as for normal neural maturation of hippocampal granule cells 322. Importantly, BDNF is not only a target downstream of excitatory GABAergic transmission but through activation of TrkB receptors on GABAergic terminals serves to promote GABA release 323,324 (Figure 2). Thus, BDNF enables a positive feedback loop that upregulates GABAergic signaling, which explains its essential role for normal neural maturation. A related BDNF- and GABA-mediated mechanism protects mature neurons from posttraumatic injury 325. Currently used AD therapies 314 and ECT all enhance the expression of BDNF 313, suggesting that these therapies might include enhancement of GABAergic transmission. However, the positive feedback relationship between GABAAR activation, BDNF expression and GABA release may be self-limited to immature neurons (and possibly other neurons with high intracellular Cl− concentrations) as BDNF also promotes the expression of KCC2, which diminishes and eventually eliminates GABAergic depolarization 326,327. Indeed, in contrast to chronic effects of BDNF in immature neurons, acute effects of BDNF at synapses of mature hippocampal pyramidal cells reduce GABAergic transmission 328–332 by acting at postsynaptic TrkB receptors that act through PKC and PI-3 kinase-dependent signaling pathways and reduce the surface stability of GABAARs 329,332. Moreover, unlike in immature neurons, GABAergic input to adult neurons reduces expression of BDNF 333.

The neural maturation deficit of dentate gyrus granule cells of BDNF-depleted mice 322 is reminiscent of similar cellular deficits in GABAAR γ2+/− mice (see below). However, unlike the depressive-like phenotype of γ2+/− mice detailed further below, mouse lines that are depleted in BDNF or TrkB, do not reliably show behavioral signs of depression, probably reflecting opposing functions of BDNF in the ventral tegmental area (VTA) and nucleus accumbens vs. hippocampus 264. Moreover, AD-mediated increases in BDNF do not correlate with behavioral effects induced by BDNF administered to different brain regions 334. Whereas BDNF deficits alone cannot explain the depressive-like phenotypes of GABAAR-deficient mice, a hypomorphic human allele of BDNF (BDNFVal66Met) is known to interact with environmental stress factors to increase the vulnerability for depression in people 335–337. Preclinical experiments discussed further below suggest that these stress factors involve GABAAR deficits.

The anxiolytic effects of BZs remain intact even when hippocampal neurogenesis has been blocked 263. This observation and the fact that BZs, unlike ADs, are effective as anxiolytics on acute treatment, indicate that the cellular substrate for anxiolytic effects of BZs is distinct from the one that mediates anxiolytic effects of ADs. Nevertheless, classical BZs are predicted to promote GABA/CREB/BDNF signaling and maturation of adult-born hippocampal neurons. However, drugs that potentiate the function of GABAARs do not only promote the maturation of immature neurons, they also seem to accelerate the cell cycle exit of proliferating neural progenitor cells, which delimits the pool of replicating cells and negatively affects neurogenesis 200,281. These putative antagonistic effects of BZs on the total pool of immature dentate gyrus granule cells may explain the limited efficacy of BZs as antidepressants. GABAAR subtype-specific ligands that act selectively on certain GABAAR subtypes might circumvent this limitation. For example, the sedative hypnotic eszopiclone has BZ-like effects mainly on α2βγ2 and α3βγ2 subtypes of GABAARs 338 and promotes the survival of adult born hippocampal granule cells in rats without affecting proliferation 339,340. In addition, eszopiclone has promise as a novel non-monoaminergic antidepressant in patients 187–189,341.

GABAAR-deficient mice as animal models of depression

GABAAR γ2 subunit deficient mice and the function of postsynaptic subtypes of GABAARs

GABAergic deficits cause depressive-like behavioral and cognitive deficits

The evidence for a role of GABAergic transmission summarized thus far does not prove a causal relationship between GABAergic deficits and depressive disorders. However, corresponding evidence is now available from mice engineered to model depressive disorders. In particular, mice rendered heterozygous for the γ2 subunit (γ2+/−) of GABAARs have been characterized as an animal model of anxious depression that includes anxious- and depressive-like emotional behaviors in eight different tests 49,108,342 (for a summary of phenotypes see Table 2). The γ2+/− model is based on a modest functional deficit in postsynaptic GABAARs, as evidenced by unaltered GABAAR numbers but reduced punctate immunofluorescent staining representative of postsynaptic GABAAR subtypes and loss of GABAAR BZ binding sites ranging from 6% (amygdala) to 35% (hippocampus) of GABAARs, depending on brain region 342. The magnitude of this deficit is comparable to GABAAR deficits observed in rodents that had been subjected to maternal deprivation stress 106,107, suggesting it is within the pathophysiological range triggered by adverse environments that are implicated in the etiology of mood disorders. The phenotype of γ2+/− mice includes heightened neophobia and behavioral inhibition to naturally aversive situations 342, reduced escape attempts under highly stressful conditions 108, as well as anhedonia-like effects 49 that mimic core symptoms of anxious melancholic depression. Lastly, γ2+/− mice exhibit selective cognitive deficits such as an attentional bias for threat cues and impaired ambiguous cue discrimination 342, which are reminiscent of cognitive impairments described in people at risk of or suffering from depression 343–348, and principally attributed to the hippocampus 349 and frontal and cingulate cortex 350,351.

Table 2.

Juxtaposition of phenotypes of Major Depressive Disorder and GABAAR γ2+/− mice.

| MDD patient phenotype | References | Phenotype of GABAAR γ2+/− mice | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| GABA deficits in anterior cingulate, dorsomedial, dorsolateral and occipital cortices | 56, 60–62, 64, 65, 74 | Structural and functional GABAAR deficits mainly in frontal cortex and hippocampus. Deficits in telencephalon are sufficient for depression-related behavior and HPA axis hyperactivity | 49, 108, 342 |

| Comorbidity with anxiety disorders, anxious personality traits | 3, 7–9 | Elevated anxiety as evidenced by heightened behavioral inhibition in response to diverse naturally aversive stimuli | 342 |

| Aversive/stressful early life events as etiological risk factors | 102–104, 383, 384 | Phenotype requires developmental GABAAR deficits in immature neurons | 108 |

| Impaired attentional set shifting in melancholic MDD; Response selection deficits in melancholic vs. non-melancholic unipolar major depression; Impaired attention and response inhibition in psychotic MDD | 343, 345, 346 | Impaired ambiguous cue discrimination, enhanced 1s trace conditioning, normal delay conditioning and unaltered spatial learning in the Morris maze | 342 |

| Despair, dysphoria, suicidality | 117 | Reduced escape behavior in response to highly stressful conditions | 49, 108 |

| Anhedonia | 117 | Reduced sucrose consumption | 49 |

| Hippocampal volume reduction as long-term consequence | 139, 270, 272, 275, 385 | Reduced numbers of adult generated mature neurons | 108 |

| Increased basal levels of serum cortisol and other forms of HPA axis dysfunction | 19, 117–119, 148 | Increased HPA axis basal activity | 49 |

| Increased responsiveness to AD treatment of severe vs. mildly depressed patients | 354 | Increased behavioral sensitivity to ADs | 49 |

| Increased therapeutic efficacy of TCAs vs. FLX | 356–358, 360–363 | Desipramine is anxiolytic and antidepressant, FLX is merely anxiolytic | 49 |

| HPA axis function normalized by TCAs but not FLX | 120, 364–366, 386 | HPA axis hyperactivity normalized by desipramine but not FLX | 49 |

| HPA axis normalization by AD treatment as a predictor of remission | 120, 148 | HPA axis normalization correlates with efficacy of AD treatment in depression related behavioral tests | 49 |

GABAergic deficits decrease the survival of adult born hippocampal neurons

Consistent with the hypotheses that depressive disorders represent chronic deficits in neurotrophic support 352 and that GABAergic signaling has trophic function 353, the γ2+/− model shows normal proliferation of neural precursor cells but reduced survival of adult-born hippocampal granule cells 108. The manifestation of this neurogenesis deficit in three different global and conditional γ2-deficient mouse lines is correlated with development of anxious depressive behavior 108, suggesting that altered neurogenesis and behavioral phenotypes are causally linked.

GABAergic deficits cause HPA axis hyperactivity and increases responsiveness to antidepressant drugs

The neuroendocrine phenotype of γ2+/− mice includes constitutively elevated serum corticosterone and increased behavioral and endocrine sensitivity to treatment with ADs compared to wild-type mice 49, which are known characteristics of severely depressed patients 119,354. Selective heterozygous inactivation of the γ2 gene in the developing telencephalic forebrain (including hippocampus and frontal cortex, induced around embryonic day10) is sufficient to induce HPA axis hyperactivity 49 and altered behavior 108, indicating that the causative GABAergic deficit in these mice is extra-hypothalamic (Figure 1). Glucocorticoids are known to reduce expression of GABAARs in the forebrain, particularly in the frontal cortex and ventral hippocampus 114,130,355. Moreover, recent evidence indicates that chronic but not acute stress results in loss of parvalbumin positive hippocampal interneurons 131. Corresponding losses of interneurons in γ2+/− mice might further enhance GABAergic deficits of γ2+/− mice and amplify the observed defects in hippocampal neurogenesis. Defects in hippocampal neurogenesis in turn are sufficient to cause HPA axis hyperactivity 135. Thus, GABAAR deficits in the telencephalon including especially the frontal cortex and hippocampus may be both a cause for, and a consequence of, HPA axis hyperactivity, a feature that may initiate a self-perpetuating feedback loop that amplifies GABAergic deficits, with HPA axis hyperactivity serving as a critical link 49 (Figure 1).

GABAergic deficits cause increased therapeutic efficacy of desipramine compared to fluoxetine

The selective norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor desipramine faithfully reverses both the anxious, depressive-like and anhedonia-like behavioral phenotypes, as well as the elevated serum corticosterone concentrations of γ2+/− mice 49. By contrast, fluoxetine shows merely anxiolytic-like activity and fails to normalize depression-related behavior and HPA axis function of γ2+/−mice. The qualitatively lesser response of γ2+/− mice to fluoxetine than desipramine is reminiscent of severe subtypes of anxious depressive disorders including melancholic depression, which tend to show greater responsiveness to TCAs than fluoxetine 356–363. Similar to the γ2+/− model, clinical evidence indicates that elevated basal activity of the HPA axis is linked to poor responsiveness to fluoxetine in patients 356,364,365, whereas normalization of HPA axis function by antidepressants is associated with remission from depression 120,366.

The γ2+/− model shows selective vulnerability to mood disorders during early life

GABAergic transmission acts as key regulator of brain development as indicated by its roles in neurogenesis 201, neural migration 367, maturation 108, and circuit formation 287,368,369. In order to delineate the developmental time course and brain regions responsible for the anxious depressive phenotype of γ2+/− mice, the behavioral and endocrine consequences of γ2 subunit deficits were analyzed in two different conditional mutant strains (Cre-loxP system) 49,108. Mice whose GABAAR deficit is initiated during embryogenesis but limited to the telencephalon were found to replicate the behavioral phenotype and HPA axis hyperactivity of global KO mice, showing that HPA axis hyperactivity can develop independently of primary GABAAR deficits in the hypothalamus 49. By contrast, delayed inactivation of the γ2 gene during adolescence leads to developmentally delayed HPA axis hyperactivity, which is not accompanied by anxiety or depression-related behaviors 49,108. These data suggest that the anxious depressive-like phenotype of γ2+/− mice is caused by a developmental GABAergic deficit, whose sequelae include inadequate neurotrophic support in the hippocampus and chronic HPA axis activation. This scenario is consistent with heightened vulnerability to anxiety and mood disorders in people during early life 100–104. In sum, the GABAAR γ2+/− mouse model includes behavioral, cognitive, cellular, neuroendocrine and developmental dimensions as well as antidepressant drug response characteristics expected of an animal model of melancholic depression and demonstrates that GABAAR deficits can be causative for all these phenotypes.

GABAAR δ subunit-deficient mice and the function of extrasynaptic subtypes of GABAARs

Pregnancy and parturition are associated with marked fluctuations in neuroactive steroids, which are linked to changes in mood and anxiety level and known to act mainly through δ subunit-containing, nonsynaptic GABAAR subtypes. Failures of this neuroendocrine system to adapt to rapid changes in ovarian and adrenal hormone level are implicated in postpartum depression (PPD) and postpartum psychosis as evidenced by studies in rodents. Increased brain concentrations of neuroactive steroids during pregnancy of the rat are followed by a sudden drop to control levels within two days of delivery 370. In rat cortex, late stage pregnancy shows decreased expression of the γ2 and α5 subunits of GABAARs and a corresponding reduction in GABAAR function, which rebounds after delivery 371. In dentate gyrus granule cells and CA1 pyramidal cells, pregnancy of rats is associated with gradually increased and decreased expression of the δ and γ2 subunits of GABAARs, respectively, and this effect is normalized within 7 days of delivery 166. Parturition is further associated with a rapid and transient increase in expression of the α4 subunit in the same cells 166. The change in GABAAR subunit composition during pregnancy is associated with increased tonic GABAergic inhibition compared to neurons analyzed during estrus and dependent on de novo neurosteroid synthesis 166.

Pregnancy in mice, unlike in rats, produces a significant downregulation of both the γ2 and δ subunits and corresponding reductions in phasic and tonic GABAergic currents recorded from hippocampal granule cell neurons 170. Reduced expression of GABAARs is thought to compensate for gonadal neurosteroid-mediated increases in GABAAR activity during pregnancy. Postpartum, the expression of GABAAR subunits and the phasic and tonic GABAergic currents recorded from granule cells rebound rapidly to levels found in virgin females. Interestingly, GABAAR δ subunit KO mice, which are unable to adjust expression of δ-containing GABAARs show drastic deficits in GABAergic tonic inhibition specifically postpartum, that is associated with anxiety and depression-related behavior as well as abnormal maternal behavior. The pathology of δ subunit KO mice thereby mirrors the symptoms of psychotic PPD 170.

Dynamic changes in neurosteroid synthesis and GABAAR subunit expression also occur during the estrus cycle, and alterations in these mechanisms are implicated in the etiology of premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMDD) 169,372. Elevated expression of α4βδ receptors in late diestrus (high-progesterone phase) of the mouse causes increased tonic inhibition of dentate gyrus granule cells along with reduced anxiety 169. Reduced expression of the δ subunit during estrus is paralleled by upregulation of γ2-containing GABAARs, which are comparatively insensitive to neurosteroids. Pharmacological blockade of neurosteroid synthesis from progesterone inhibits cyclic changes in GABAAR subunit expression and neural plasticity while the progesterone receptor antagonist RU486 has no effect, indicating that neurosteroid synthesis rather than nuclear progesterone receptor activation underlies hormone-mediated neural plasticity 115. Consistent with this interpretation, upregulation of α4βδ receptors and tonic inhibition in hippocampal granule cells can be induced by treatment with THDOC or by acute stress, a condition known to increase neurosteroid levels 115. Estrus cycle-associated changes in the expression of α4βδ receptors have also been shown in the periaqueductal gray matter of female rats 165, indicating that neurosteroid–induced plasticity is not limited to the dentate gyrus. In addition to the role of neurosteroids in regulating GABAAR subunit gene expression and as allosteric modulators of α4βδ receptors, neurosteroids have been shown to regulate protein kinase C (PKC)-mediated phosphorylation of GABAARs 373. PKC is known to regulate the cell surface accumulation of GABAARs and GABAergic inhibition 374. In sum, anomalous regulation of α4βδ receptors by neurosteroids at the level of gene expression, channel gating and/or receptor trafficking is implicated in the etiology of PPD and PMDD.

Conclusions, limitations, and outlook

The collective evidence summarized here indicates that reduced concentrations of GABA and altered expression of GABAARs are common abnormalities observed in MDDs. GABAergic transmission is vital for the control of stress and impaired by chronic stress, the most important vulnerability factor of MDD. Currently used antidepressants, which are designed to augment monoaminergic transmission, have in common that they ultimately serve to enhance GABAergic transmission. GABAergic excitation of immature neurons in the dentate gyrus has been identified as a key mechanism that provides trophic support and controls the dendritic maturation and survival of neurons, a process that serves as a molecular and cellular substrate of antidepressant drug action. Lastly, comparatively modest deficits in GABAergic transmission are sufficient to cause most of the cellular, behavioral, cognitive and pharmacological sequelae expected of an animal model of major depression. GABAergic transmission is further subject to dynamic regulation by estrus- and pregnancy-associated changes in steroid hormone synthesis and altered expression of extrasynaptic GABAARs that may contribute preferentially to female-specific risk factors of mood disorders and explain the increased prevalence of MDD in the female population. The behavioral phenotypes in GABAAR γ2+/− and δ subunit knockout mice suggest that deficits in both synaptic and nonsynaptic GABAergic transmission can contribute to depressive disorders.

Despite remarkable recent progress we are left with a number of significant gaps in understanding. GABAergic deficits are not unique to MDD but similarly implicated in a number of other neuropsychiatric disorders, especially schizophrenia 375,376. The question arises whether and how GABAergic deficits can help to differentiate between these different disorders. Moreover, the mechanisms that lead to initial GABAergic deficits remain poorly understood and they are so far not explained by mutations or functional polymorphisms in genes intimately involved in GABAergic transmission. We have listed a number of reasons that explain why currently available GABA potentiating drugs are ineffective as antidepressants, yet it remains to be established whether next generation GABAergic drugs that are more selective for GABAARs expressed in corticolimbic circuits affected in depression exhibit more convincing efficacy as antidepressants. Furthermore, a number of aspects of major depressive disorders are not know to involve GABAergic deficits. For example, there is increasing preclinical evidence that resilience to stress and stress-induced neuropsychiatric disorders including depression are subject to epigenetic mechanisms 377, yet there is little evidence for epigenetic regulation of GABAergic transmission. Transcriptional and immunohistochemical alterations in brain of depressed patients suggest links between depressive disorders and inflammation, apoptosis 378 and oligodendrocyte dysfunction 379,380, but none of these have been linked to GABAergic deficits. Future research should address these gaps in understanding and lead the path to improved antidepressant therapies that strive to correct the causal neurochemical imbalances rather than merely the symptoms of depression.

Acknowledgments

We thank Byron Jones, Pam Mitchell and Casey Kilpatrick for critical reading of the manuscript. Research in the Luscher laboratory is supported by grants MH62391, MH60989 and RC1MH089111 from the National Institutes of Mental Health (NIMH), and a grant from the Pennsylvania Department of Health using Tobacco Settlement Funds. The contents of this review are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the NIMH or the NIH. The Pennsylvania Department of Health specifically disclaims responsibility for any analyses, interpretations or conclusions.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest. The authors declare no conflict of interest

References

- 1.Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, Jin R, Koretz D, Merikangas KR, et al. The epidemiology of major depressive disorder: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R) JAMA. 2003;289:3095–3105. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.23.3095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kendler KS. Major depression and generalised anxiety disorder. Same genes, (partly)different environments--revisited. Br J Psychiatry Suppl. 1996:68–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kaufman J, Charney D. Comorbidity of mood and anxiety disorders. Depress Anxiety. 2000;12 (Suppl 1):69–76. doi: 10.1002/1520-6394(2000)12:1+<69::AID-DA9>3.0.CO;2-K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fava M, Kendler KS. Major depressive disorder. Neuron. 2000;28:335–341. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)00112-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vos T, Mathers CD. The burden of mental disorders: a comparison of methods between the Australian burden of disease studies and the Global Burden of Disease study. Bull World Health Organ. 2000;78:427–438. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eley TC, Bolton D, O'Connor TG, Perrin S, Smith P, Plomin R. A twin study of anxiety-related behaviours in pre-school children. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2003;44:945–960. doi: 10.1111/1469-7610.00179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Murphy JM, Horton NJ, Laird NM, Monson RR, Sobol AM, Leighton AH. Anxiety and depression: a 40-year perspective on relationships regarding prevalence, distribution, and comorbidity. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2004;109:355–375. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2003.00286.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kessler RC, Chiu WT, Demler O, Walters EE. Prevalence, severity, and comorbidity of 12-month DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62:617–627. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gamez W, Watson D, Doebbeling BN. Abnormal personality and the mood and anxiety disorders: Implications for structural models of anxiety and depression. J Anxiety Disord. 2006 doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2006.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schildkraut J. The catecholamine hypothesis of affective disorders: a review of supporting evidence. Amer J Psychiat. 1965;122:509–522. doi: 10.1176/ajp.122.5.509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bunney WE, Jr, Davis JM. Norepinephrine in depressive reactions. A review. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1965;13:483–494. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1965.01730060001001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Coppen A. The biochemistry of affective disorders. Br J Psychiatry. 1967;113:1237–1264. doi: 10.1192/bjp.113.504.1237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Matussek N. Die Catecholamin- und Serotoninhypothese der Depression. In: Hippius H, Seebach H, editors. Das Depressive Syndrom. Urban & Schwarzenberg, München; Berlin, Wien: 1969. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nutt DJ. The neuropharmacology of serotonin and noradrenaline in depression. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2002;17 (Suppl 1):S1–12. doi: 10.1097/00004850-200206001-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hirschfeld RM. History and evolution of the monoamine hypothesis of depression. J Clin Psychiatry. 2000;61 (Suppl 6):4–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Heninger GR, Delgado PL, Charney DS. The revised monoamine theory of depression: a modulatory role for monoamines, based on new findings from monoamine depletion experiments in humans. Pharmacopsychiatry. 1996;29:2–11. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-979535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kendler KS, Karkowski LM, Prescott CA. Causal relationship between stressful life events and the onset of major depression. Am J Psychiatry. 1999;156:837–841. doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.6.837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gilbertson MW, Shenton ME, Ciszewski A, Kasai K, Lasko NB, Orr SP, et al. Smaller hippocampal volume predicts pathologic vulnerability to psychological trauma. Nat Neurosci. 2002;5:1242–1247. doi: 10.1038/nn958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gold PW, Chrousos GP. Organization of the stress system and its dysregulation in melancholic and atypical depression: high vs low CRH/NE states. Mol Psychiatry. 2002;7:254–275. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Holsboer F. Stress, hypercortisolism and corticosteroid receptors in depression: implications for therapy. J Affect Disord. 2001;62:77–91. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(00)00352-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hatzinger M. Neuropeptides and the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenocortical (HPA) system: review of recent research strategies in depression. World J Biol Psychiatry. 2000;1:105–111. doi: 10.3109/15622970009150573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Binder EB, Nemeroff CB. The CRF system, stress, depression and anxiety insights from human genetic studies. Mol Psychiatry. 2010;15:574–588. doi: 10.1038/mp.2009.141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Warner-Schmidt JL, Duman RS. Hippocampal neurogenesis: opposing effects of stress and antidepressant treatment. Hippocampus. 2006;16:239–249. doi: 10.1002/hipo.20156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dranovsky A, Hen R. Hippocampal neurogenesis: regulation by stress and antidepressants. Biol Psychiatry. 2006;59:1136–1143. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.03.082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Manji HK, Drevets WC, Charney DS. The cellular neurobiology of depression. Nat Med. 2001;7:541–547. doi: 10.1038/87865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Duman RS, Monteggia LM. A neurotrophic model for stress-related mood disorders. Biol Psychiatry. 2006;59:1116–1127. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pittenger C, Duman RS. Stress, depression, and neuroplasticity: a convergence of mechanisms. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2008;33:88–109. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Krishnan V, Nestler EJ. The molecular neurobiology of depression. Nature. 2008;455:894–902. doi: 10.1038/nature07455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mombereau C, Kaupmann K, Froestl W, Sansig G, van der Putten H, Cryan JF. Genetic and pharmacological evidence of a role for GABA(B) receptors in the modulation of anxiety- and antidepressant-like behavior. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2004;29:1050–1062. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mombereau C, Kaupmann K, Gassmann M, Bettler B, van der Putten H, Cryan JF. Altered anxiety and depression-related behaviour in mice lacking GABAB(2) receptor subunits. Neuroreport. 2005;16:307–310. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200502280-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Olsen RW, Sieghart W. International Union of Pharmacology. LXX. Subtypes of gamma-aminobutyric acid(A) receptors: classification on the basis of subunit composition, pharmacology, and function. Update Pharmacol Rev. 2008;60:243–260. doi: 10.1124/pr.108.00505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Farrant M, Nusser Z. Variations on an inhibitory theme: phasic and tonic activation of GABA(A) receptors. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2005;6:215–229. doi: 10.1038/nrn1625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rudolph U, Mohler H. GABA-based therapeutic approaches: GABA(A) receptor subtype functions. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2006;6:18–23. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2005.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Whiting PJ. GABA(A) receptors: a viable target for novel anxiolytics? Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2006;6:24–29. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2005.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rudolph U, Crestani F, Benke D, Brünig I, Benson J, Fritschy JM, et al. Benzodiazepine actions mediated by specific γ-aminobutyric acidA receptor subtypes. Nature. 1999;401:796–800. doi: 10.1038/44579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.McKernan RM, Rosahl TW, Reynolds DS, Sur C, Wafford KA, Atack JR, et al. Sedative but not anxiolytic properties of benzodiazepines are mediated by the GABA(A) receptor alpha1 subtype. Nat Neurosci. 2000;3:587–592. doi: 10.1038/75761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tan KR, Brown M, Labouebe G, Yvon C, Creton C, Fritschy JM, et al. Neural bases for addictive properties of benzodiazepines. Nature. 2010;463:769–774. doi: 10.1038/nature08758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Crestani F, Martin JR, Mohler H, Rudolph U. Resolving differences in GABA(A) receptor mutant mouse studies. Nat Neurosci. 2000;3:1059. doi: 10.1038/80553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Knabl J, Witschi R, Hosl K, Reinold H, Zeilhofer UB, Ahmadi S, et al. Reversal of pathological pain through specific spinal GABA(A) receptor subtypes. Nature. 2008;451:330–334. doi: 10.1038/nature06493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Low K, Crestani F, Keist R, Benke D, Brunig I, Benson JA, et al. Molecular and neuronal substrate for the selective attenuation of anxiety. Science. 2000;290:131–134. doi: 10.1126/science.290.5489.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Crestani F, Low K, Keist R, Mandelli M, Mohler H, Rudolph U. Molecular targets for the myorelaxant action of diazepam. Mol Pharmacol. 2001;59:442–445. doi: 10.1124/mol.59.3.442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Crestani F, Keist R, Fritschy JM, Benke D, Vogt K, Prut L, et al. Trace fear conditioning involves hippocampal alpha5 GABA(A) receptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:8980–8985. doi: 10.1073/pnas.142288699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]