Abstract

We present a model of training in evidence-based psychosocial treatments (EBTs). The ACCESS (assess and adapt, convey basics, consult, evaluate, study outcomes, sustain) model integrates principles and findings from adult education and training literatures, research, and practical suggestions based on a community-based clinician training program. Descriptions of the steps are provided as a means of guiding implementation efforts and facilitating training partnerships between public mental health agencies and practitioners of EBTs.

Keywords: evidence-based psychotherapies, training, consultation, implementation

In recent years, the fields of psychology and medicine have moved toward the provision of evidence-based practice (Norcross, Beutler, & Levant, 2006; Sackett, Rosenberg, Gray, Haynes, & Richardson, 1996). Community-based training initiatives in evidence-based psychosocial treatments (EBTs; Kazdin, 2008) have garnered increased support in light of evidence that some EBTs can be transported effectively into nonresearch and community-based settings (cf. Miranda, Azocar, Organista, Dwyer, Arean, 2003). Although many large systems such as the National Health Service in the United Kingdom (DH/Mental Health Programme, 2009; Holmes, Mizen & Jacobs, 2007), the United States Department of Veterans Affairs (Levin, 2009), and state mental health systems (Glisson & Schoenwald, 2005) have mandated the implementation of EBTs, the intensity and format of training varies considerably across initiatives. Some systems have provided manuals or one-time workshops to reach numerous providers with a limited budget (Jensen-Doss, Hawley, Lopez, & Osterberg, in press), whereas others have required more intensive, long-term training and supervision (DH/Mental Health Programme, 2008). Although workshops and one-time trainings may change therapist knowledge and behavior to some extent (Henggeler et al., 2008), direct observation of clinician behaviors indicates that clinicians who receive such brief training are unlikely to deliver the treatment at recommended levels of competence and fidelity (Miller, Yahne, Moyers, Pirritano, & Martinez, 2004; Sholomskas et al., 2005). These findings are troubling, as aspects of treatment integrity (Perepletchikova, Treat, & Kazdin, 2007) have been linked to clinical outcomes for numerous EBTs (e.g., Feeley, DeRubeis, & Gelfand, 1999; Schoenwald, Carter, Chapman, & Sheidow, 2008). Insufficient attention to treatment integrity during implementation may result in discontinuation or inconsistent treatment delivery. As an estimated 50% of implementation efforts result in failure (Klein & Knight, 2005), it is essential that implementation programs be conducted in a manner that maximizes the likelihood that consumers will actually receive competently delivered EBTs.

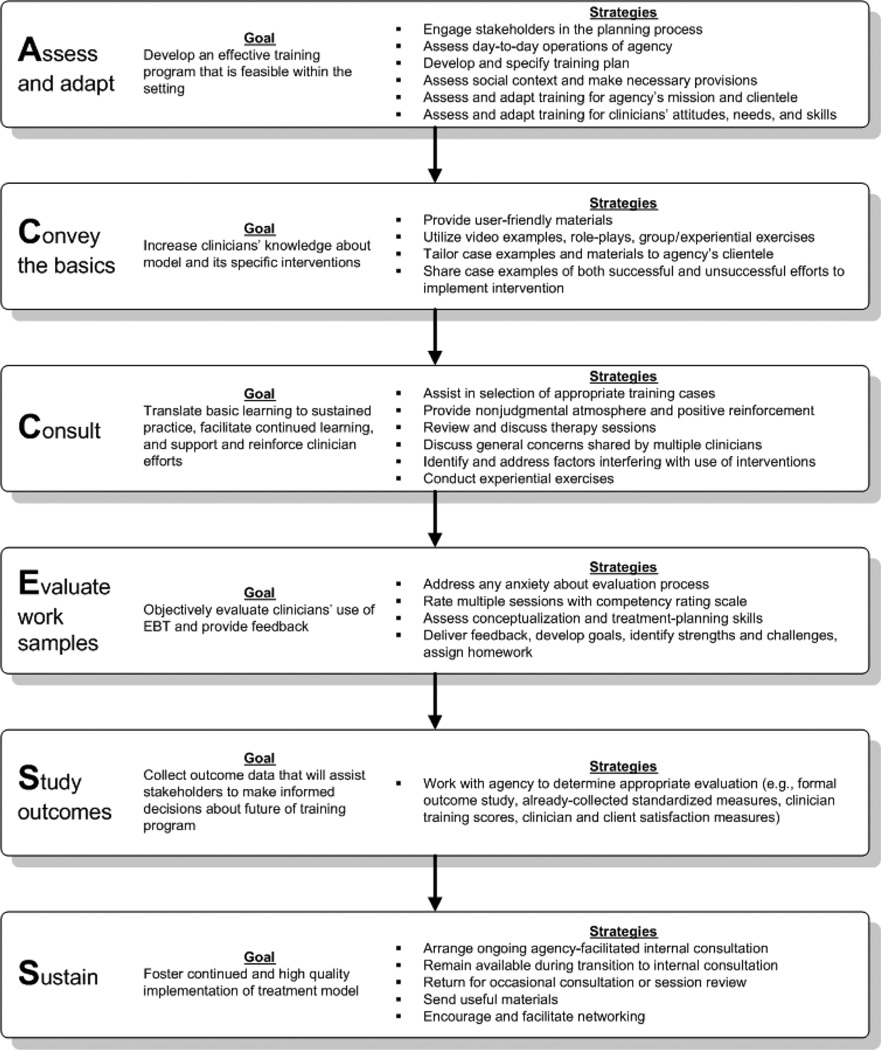

Much of the training and supervision literature within the field of clinical psychology does not address the unique challenges that arise in training in public mental health service settings. Therefore, we suggest a comprehensive model for providing training in EBTs that can inform local and larger scale implementation and facilitate training partnerships with publicly funded or community-based agencies and practitioners of EBTs. The ACCESS model (assess and adapt, convey basics, consult, evaluate, study outcomes, sustain; see Figure 1) integrates principles and findings from psychotherapy training and implementation research, adult education theory and research, and training guidelines of some of the larger ongoing implementation programs (cf. DH/Mental Health Programme/Improving Access to Psychological Therapies, 2008; Levin, 2009). In addition, the model was shaped through the development of a public–academic training partnership (Stirman, Buchhofer, McLaulin, Evans, & Beck, 2009) in cognitive therapy (CT). The ACCESS model augments the clinical trials model of supervision (Martino, Gallon, Ball, & Carroll, 2008) and existing models of training by emphasizing context-specific training and consultation, session review and feedback, and ongoing support to facilitate sustained use of the EBTs.

Figure 1.

The ACCESS Model (assess and adapt, convey basics, consult, evaluate, study outcomes, sustain) of training and consultation in evidence based treatments. EBT = evidence-based psychosocial treatment.

Description of the ACCESS Model

Assess and Adapt

Agency-level assessment and adaptation

Although the developers of some EBTs have opened institutes with set curriculum specifically for training clinicians (Fixsen, Naoom, Blase, Friedman, & Wallace, 2005), the time and costs related to enrollment and travel are often prohibitive for the community-based clinicians or mental health systems. Many training programs for clinicians in public mental health agencies occur in the form of a public–academic partnership, and instructors are asked to bring the training directly to the clinicians. It is essential to work closely with agency administration, consumers, and other key stakeholders when forming the training program to understand the realities of service delivery in public mental health settings, meet the needs of these stakeholders, and foster a spirit of partnership. The importance of commitment among agency administration to the success of such a training program cannot be overstated (cf. Chorpita et al., 2002; Rogers, 2002). Familiarity with strategies for developing public–academic collaborations can help the instructors anticipate and address barriers to successful training (cf. Chorpita & Mueller, 2008; Stirman, Crits-Christoph, & DeRubeis, 2004).

A good understanding of the day-to-day operations of the agency, the available resources, and the potential constraints (Lehman, Greener, & Simpson, 2002) is crucial to the success of a training program in a public mental health service setting. Such an assessment will assist instructors in developing a training program that is adequate, yet feasible given the constraints that are present in public mental health settings. Readiness for change, agency climate and culture, and turnover are associated with the adoption or discontinuation of EBTs (Glisson et al., 2008; Woltmann et al., 2008). Financial productivity requirements and staff shortages may also impact the program by limiting the time clinicians can spend in training. In some settings, additional provisions may be needed to ensure that adequate support and protected time are allocated, that the rate of turnover among trainees is minimized, and/or that those who are trained are open to trying a new approach. Organization-level interventions (Glisson & Schoenwald, 2005) or new procedures may also be necessary to facilitate the training program. For example, the introduction of efficient systems of documentation might free time for training and provide a means of tracking the use of the EBT.

The development of a plan detailing how the training will be accomplished should take these contextual factors into account and should involve key stakeholders. It is also important to come to an agreement on whether clinicians’ progress will be shared with their supervisors, and if so, whether there will be implications for the clinician if progress is not adequate (Knowles, 1980). Addressing these issues at the outset is essential to preventing instructors from being caught between their relationships with the clinicians whom they are training and any contractual obligations to the agency or, if applicable, funding source. Because the instructor is not an employee of the agency and may not meet the requirements necessary for formal supervision, it is important to specify the limits of the consultation relationship to the clinicians, consumers, and administration. Stakeholders should collaborate to develop a document that delineates what the program entails, including the necessary time and funding, requirements for successful completion, the limits of confidentiality, limits of the consultation relationship with the instructor, and the purpose of program-related audio- or videorecording. Throughout the training, regular meetings with key personnel are necessary to allow troubleshooting and promote communication.

An understanding of the specific mission and client population of the agency is another key factor in joining successfully with an agency for training. It is important to adapt language and case examples to fit within the norms of the agency and demonstrate an understanding of the agency’s clientele, values, and mission. For example, comorbidity and low socioeconomic status are common among community samples (Weaver et al., 2003). Instructors should be prepared to assist clinicians in maintaining a therapeutic focus with multiproblem clients, and to ensure that the EBT is delivered in a culturally competent manner. Hwang, Wood, Lin, and Cheung (2006) and Miranda and colleagues (2003) provided excellent examples of successful adaptation and use of EBTs with ethnic minorities and lower income clienteles.

Clinician-level assessment and engagement

As with any innovation, the success of a training program or implementation effort depends largely on the engagement and “buy-in” of the target audience (Rogers, 2002). Clinician engagement is related to implementation intention and can have an impact on the success of a training effort (Palinkas et al., 2008). Although some clinicians may welcome the specialized training, others may voice ambivalence or skepticism. Some may resent the imposition of protocols they view as either interfering with usual practices or devaluing of their own experience and expertise (Speck, 1996). Some clinicians may assume that EBTs require rigid adherence to structured intervention and that such manualized treatments would damage the therapeutic relationship and lead to early termination. Concerns may also stem from beliefs that treatment restricted to a mechanistic or superficial “cookbook” approach (Gluhoski, 1994) will not meet the complex needs of their clients. For other clinicians, key elements of the model may trigger discomfort (Palinkas et al., 2008), appear antithetical to their theoretical orientation, or seem too difficult to learn (Swenson, Torrey, & Koerner, 2002). The seriousness of these assumptions is further exacerbated if clinicians assume that the instructors do not have a good understanding of their views and experiences in practice (Knowles, 1980).

As ambassadors of the new training model, instructors should keep in mind that if clinicians have a positive experience with the instructors and the training, they are more likely to implement the model (Schmidt & Taylor, 2002). Pretraining group and individual meetings between the clinicians and the instructors allow each individual a much needed opportunity to ask questions and explore his or her own concerns. Throughout the training, instructors should create an open, nonjudgmental forum for clinicians to voice their opinions, doubts, or enthusiasm. Rather than automatically dismissing clinicians’ concerns as “resistance,” instructors should acknowledge that some degree of skepticism is normal (Ford, Ford, & D’Amelio, 2008). Initial steps in engaging clinicians may focus on conversations about the relevance of the training to clinicians’ experiences and goals (Knowles, 1980), concerns about training, and the degree to which clinicians are open to the training in the new treatment model. Opening the door to communication, and emphasizing commonalities and areas of agreement with clinicians demonstrates respect for them as professionals and partners, enhancing the collaborative process (Knowles, 1980). These conversations also provide valuable assessment information about clinicians’ baseline knowledge of and attitudes towards different theoretical models, including whether and how they can articulate their own theoretical orientation, doubts, and concerns.

To the extent possible within a specific EBT model, trainers should emphasize that the ideal use of treatment manuals can and must involve “flexibility within fidelity” (Kendall & Beidas, 2007). It is important to emphasize that the EBT has been shown to be effective when delivered with fidelity rather than integrated with other modalities (Fagan, Hanson, Hawkins, & Arthur, 2008). However, fidelity does not necessarily preclude the integration of a clinician’s own style into the model in a thoughtful manner, to the extent that it is not in contrast with the EBT. Furthermore, the content of the treatment manual can often be adapted to the needs of clients or to the constraints within the setting (Persons, 2006).

Although little data exist on characteristics that distinguish successful clinician trainees, research suggests that clinicians of different ages, theoretical orientations, employment histories, and training backgrounds can be trained successfully in EBTs (Crits-Christoph et al., 1998; James, Blackburn, Milne, & Reichfeldt, 2001). However, motivation, prior exposure to the therapy (James et al., 2001), and good basic therapeutic skills (Stein & Lambert, 1995) can expedite the learning process. Clinicians’ training background (Fixsen et al, 2005), attitudes (Aarons, 2004), and learning needs (James, Blackburn, Milne, & Armstrong, 2006) can impact their engagement and experience in training. Some may struggle to alter the way they conceptualize cases and use new interventions (Palinkas et al., 2008; Santa Ana et al., 2008; Swenson et al., 2002); thus program staffing must be adequate to provide individual support.

Convey the Basics

When training clinicians in a new practice, a key step is increasing knowledge about the model and interventions. An initial intensive training can provide the basics of the treatment model so that clinicians understand why, how, and when they might use particular interventions. Both intensive workshops and internet-based trainings have been shown to increase knowledge about EBTs (Cucciare, Weingardt, & Villafranca, 2008). An inherent challenge in training clinicians in public settings is finding the appropriate balance between providing sufficient information and overwhelming the clinicians with training materials in a compressed period of time. It is difficult for agencies to allocate large blocks of time for the workshops, but it is essential to allocate adequate time for instruction in the basics. Self-guided training programs such as internet- or technology-based programs have the advantage of allowing clinicians to work at their own pace and have been used with success in implementation projects (King & Lawler, 2003). If a face-to-face training is desirable or feasible, workshops can be broken into small blocks of time to allow information to be digested, and attend to the clinicians’ obligations to their clients. Clinicians appreciate receiving continuing education credits for these workshops, as the education requirements of their licensing organizations can be costly and time consuming.

Several considerations regarding training materials need to be taken into account in developing the training. First, clinicians typically carrying large caseloads may not have sufficient time to read large amounts of complicated material (Woltmann et al., 2008). Therefore, concise, self-directed, and user-friendly materials with recommendations for additional optional readings, or web-based trainings are likely to be more effective (Merriam, 2001; Sholomskas et al., 2005). Second, clinicians have indicated that they prefer materials that are focused, clearly describe theoretical rationales, include examples, and describe solutions to frequently encountered problems during treatment (Najavits, Weiss, Shaw, & Dierberger, 2000). Finally, the training literature suggests that a blended learning approach, which combines multiple-learning strategies, results in greater learning (Cucciare et al, 2008; Speck, 1996). For example, video examples of case material and demonstration role plays can be interspersed to illustrate the techniques discussed in a workshop.

Theories of adult learning suggest that small group interactions and experiential exercises are pivotal for promoting the integration of new skills into daily activities (Speck, 1996). Thus, training should allow some form of interaction among clinicians, and the group size and format should facilitate such interactions. Role plays can be conducted for the purpose of practicing interventions or for introducing the model to clients. Learning exercises should be consistent with interventions used within the theoretical framework (Swenson et al., 2002). For example, in a CT workshop, participants might complete a thought record or practice guided discovery.

During discussion at the initial training, instructors must strive to address concerns without engaging in a debate or an effort to convince the more vocal skeptics, which can detract from the goal of providing basic knowledge of the model. In our experience, case examples and training materials tailored to the types of clients typically seen in the setting in which training occurs are more persuasive. Instructors may also consider making reference to their own work with some of their more challenging clients to demonstrate an understanding of the issues faced by clinicians in real-world settings. The inclusion of examples of lessons learned from less successful efforts to implement a strategy can lend credibility to the training effort and demonstrate that instructors are not attempting to make unrealistic claims about its effectiveness. At the same time, clinicians should be encouraged to try using the interventions in their practice and participating in consultation before drawing conclusions.

Consult

As Speck (1996) noted, coaching and follow-up support are central to aspects in the transfer of learning into sustained practice. Without advice specific to the challenges they encounter when attempting to implement interventions, clinicians may stop using them in the face of setbacks. Studies on training in evidence-based psychotherapies have shown that participants in stand-alone workshops did not typically reach adequate skill levels, unlike those who received consultation (Miller et al., 2004; Sholomskas et al., 2005). Thus, supervision is considered to be an important element in training clinicians in EBTs (Chambless & Ollendick, 2001) and ensuring fidelity in clinical trials (Martino, Gallon, et al., 2008).

Consultation provides a forum for providing further didactic training on topics that have emerged as important after the initial training, and can increase clinician’s comfort and skill in delivering EBTs. Group consultation may take place in the form of in-person meetings when logistics allow, or in the form of group or web-based conference calls. These meetings are particularly useful for addressing administrative or training issues applying to all or most clinicians. Consultation typically includes detailed discussions about training cases and challenges in recent sessions as well as experiential exercises to reinforce clinicians’ own understanding of the model. Clinicians and instructors also have the opportunity to identify and explore factors such as their reluctance to implement particular interventions, or beliefs that their clients will not benefit from specific strategies. Typically, these issues are addressed in a manner consistent with the theoretical model (Martino, Gallon, et al., 2008). Consultation also offers opportunities for group members to offer one another suggestions and support and to provide reinforcement by acknowledging successes (Carter, Enyedy, Goodyear, Arcinue, & Puri, 2009).

The selection of training cases with the clinicians can have a great impact on the experience of the clinician throughout the training program (James et al., 2001). Ideally, clinicians would begin to work with a new client during consultation. However existing clients can be selected if starting with new clients is not feasible due to high attrition rates or full caseloads. Selecting clients who are already benefiting from standard treatment or for whom the required interventions are perceived as straightforward may not allow clinicians to observe the added value of using EBT. On the other hand, a clinician’s most challenging client is usually not the best choice for a first attempt at using an EBT. Before attempting to apply more advanced skills with challenging clients, clinicians should have the opportunity to see more immediate results and build confidence. Switching to more challenging training cases after basic skills are gained can help clinicians consolidate and generalize skills.

Evaluate Work Samples

If the goal of training is competence in or fidelity to a particular model, research indicates that supervised casework and feedback based on multiple-work samples is an important component (Martino, Ball, Nich, Frankforter, & Carroll 2008; Miller et al., 2004; Schoener, Madeja, Henderson, Ondersma, & Janisse 2006). Clinicians have been shown to overestimate their skill levels (Brosan, Reynolds, & Moore, 2008) and verbal reports about sessions from clinicians may omit important process variables or misrepresent what occurred in session (Martino, Gallon, et al., 2008; Perepletchikova et al., 2007). Research that has objectively measured competence and fidelity has suggested that supervised casework yields a larger or more sustained increase in skill (Miller et al., 2004; Sholomskas et al., 2005). The evaluation of work samples requires a substantial amount of time and resources, but the feasibility has been demonstrated in a community setting (Sheidow, Donohue, Hill, Ford, & Henggeler, 2008) and may be a crucial part of a training program. Recent research (Miller et al., 2004; Martino, Ball, et al., 2008) has indicated that clinician trainees who received feedback combined with coaching had clients who demonstrated in-session behaviors that were predictive of positive outcomes.

Clinicians often feel and report apprehension regarding this feature of the training model and some may resist close supervision (Perepletchikova, Hilt, Cheriji, & Kazdin, 2009). Clinicians may have worked as psychotherapists for many years and may experience discomfort with the level of scrutiny that work sample review entails (Palinkas et al., 2008). Others may be concerned that the consultation will reveal a lack of skill, and this concern may be particularly salient for clinicians if segments of sessions are reviewed in the context of group meetings rather than individual consultation. These concerns can be alleviated by normalization of their apprehension and reassurance that the reviews are intended to be used to facilitate and track their progress in implementing the EBT rather than to judge their therapeutic skills in general. Sharing anecdotes about instructors’ own experiences in receiving feedback on work samples can also help. Clinician anxiety about being recorded typically abates after they have experienced benefits from the feedback or discovered that their instructor is not overly judgmental. A second obstacle relates to concerns about confidentiality on the part of the client. Strategies for increasing clinicians’ and clients’ level of comfort include educating the client about the training program and emphasizing the potential benefits of expert consultation. In addition to requiring documentation of consent to record, instructors may provide clinicians with handouts for clients containing basic information about the program, the therapeutic model, and safeguards to confidentiality. Transferring digital recordings via a secure server that is compliant with legislative privacy guidelines is an efficient way to ensure timely feedback. Working with the agency to explain and develop the logistics of the session review before training begins will increase the likelihood that things run smoothly and that audible recordings are turned in regularly (Martino, Gallon, et al., 2008).

At the beginning of the training program, the clinicians should be given a list of core competencies in their theoretical model (cf. Roth & Pilling, 2008) and a baseline assessment (James et al., 2006) to assist them in understanding the criteria by which they will be assessed. Depending on the complexity of the model and their initial skill level, clinicians may need to receive feedback on 10 to 15 samples or more before they can consistently implement the model with competence. Instructors should work with the agency to establish a minimum number of work samples for successful completion of the program. The use of adherence measures and a competency rating scale is the “gold standard” in clinical trials (Martino, Gallon, et al., 2008). These scales facilitate the provision of feedback for work samples and allow instructors to monitor progress over time. Suggesting or requiring clinicians to periodically review and rate their own sessions before discussion with instructors can also facilitate the learning process. Instructors should emphasize the expectation that scores will be fairly low early in the training program and shape feedback in such a way that it will not discourage or overwhelm clinicians. For example, providing written feedback without attached scores in initial feedback sessions may provide the opportunity for learning without discouragement about “beginner” competency scores. Furthermore, it is important to focus on the conceptualization and the session itself rather than emphasizing the scores. In delivering feedback, one or two specific items at a time can be focused on to maximize the effectiveness of the interventions. Areas that should be prioritized in feedback include conceptualization and intervention skills, and the clinician’s ability to build and maintain a positive therapeutic relationship in the context of the EBT. At times individual feedback may also include exploration of beliefs or attitudes that may impede implementation.

A more cost-efficient alternative to individual review and feedback is a group “practicum” model, in which feedback is delivered in the context of expert-led group meetings. Although clinicians receive less feedback on their own individual cases or sessions than they would in an individual format, evidence from a variety of disciplines indicates that group training can produce results that are comparable or superior to individual training (Hampson, Schulte, & Ricks, 1983; Linehan, 1979). Hearing and participating in feedback on other clinicians’ sessions allows exposure to a broad range of clients and efforts to implement an intervention (Abbass, 2004). Further, group-level consultation can more easily be continued with an internal supervisor when expert instructors are no longer available than can individual review. Our experiences in implementing a practicum model have been well-received by clinicians, although to date, we have only used this model in settings in which the clinicians were open to the process and supportive of one another. Challenges in implementation may arise in settings in which clinicians do not feel sufficient psychological safety to receive feedback in group formats.

Study the Outcomes

Program evaluation or research on the impact of the training program allows the stakeholders to make informed decisions about the future of the program. The type of evaluation that is possible or desirable will depend on the goals of the training program and the participating agency, and should be discussed at the outset of a training effort. The use of local data and benchmarking or program evaluation strategies is often the most feasible means of assessing the impact of the program on client outcomes. Some agencies may be interested in partnering to conduct a more formal outcome study to assess the impact of the training on client outcomes, although it will be challenging to conduct a well-controlled study in many settings (Sieber, 2008). If the agency uses standardized measures to track clients’ progress, these measures may be used to examine the impact of the training program. Scores on competence or adherence measures may also be tracked throughout the course of the training program to determine whether the program has the desired impact, and whether particular trainee characteristics are associated with more positive outcomes. Clinician attitudes may also be tracked before, during, and after training. To date, limited data are available on modifications that may be required or even desirable in standard protocols for clients in nonresearch settings (Fagan et al., 2008). Similarly, although it is commonly understood that interventions are adapted by those who use them (Rogers, 2002), little is known regarding the types of adaptations that clinicians make in public settings, and whether these adaptations are beneficial (Schoenwald & Hoagwood, 2001). Training programs in the public sector offer opportunities to study these questions. Finally, clinician and client satisfaction measures may be collected to determine reactions to the EBT and further refine future training programs.

Sustain

Without ongoing support and access to information, even the most well-trained, well-intentioned clinicians may begin to struggle and drift from the model in which they received training (Palinkas et al., 2008). Introducing the means to receive support and information after the formal training is complete can increase the chances that clinicians will continue to feel equipped to implement the model (Swenson et al., 2002). Further, fidelity monitoring presented as supportive consultation after a training program has been associated with greater employee retention (Aarons, Sommerfeld, Hecht, Silovsky, & Chaffin, 2009).

Ongoing internal provisions such as regularly scheduled internal consultation sessions, led by clinicians within the agencies, should be put into place to support the efforts to implement the EBT after the training is complete. Toward the end of training, the instructor and the agency administration or trainee group can identify a skilled “internal supervisor” to lead these meetings. These supervisors may receive additional training in effectively reviewing sessions and providing feedback, structuring the consultation, and facilitating opportunities for group members to brainstorm and role play strategies for particular challenges. It is useful to continue presenting work samples for internal consultation, and clinicians should be reminded to discuss both challenges and successes.

Instructors should consider remaining available and offering to provide support during a transition to internal supervision to ensure that the focus of consultation does not drift away from the new treatment model. For the first few months, internal supervisors may find it helpful to record the group consultation sessions and receive feedback and suggestions from the instructors. Instructors may also schedule times to return for occasional consultation or session review and send materials that might be useful for their clientele to the agencies. Some agencies may also ask for help in developing a plan to train and include new clinicians in their consultation sessions. In larger training initiatives, opportunities for trained clinicians and agency directors to network can also be provided through periodic in-person, telephone, or web-based meetings. When training a larger number of clinicians, or clinicians from different agencies, it is also possible to set up an online practice community moderated by the instructors, to allow clinicians to ask questions and provide suggestions to one another (Koerner, 2008).

Implications and Applications

The ACCESS training model is based on the best available evidence for promoting both an understanding and an ability to practice EBTs with fidelity and competence. However, some components have greater empirical support than others, and more research is needed to examine factors such as the impact of group versus individual supervision and consultation, the value added by feedback over consultation alone, the cost effectiveness of community-based training models, and measures that can be used to sustain implementation. To date we have implemented the full model within nine community mental health agencies, providing 6 months of training in CT (Stirman et al., 2009). Our program evaluation indicates that 83% of the participating clinicians demonstrated competence in conducting the therapy by the end of the program. Nearly all of the remaining clinicians improved substantially and approached competence by the end. Preliminary analyses suggest that clinicians who turned in at least 15 sessions for feedback were more likely to achieve competence. A full report of training outcomes for the ACCESS model is currently being prepared.

We strongly encourage further discussion of training models in public sector settings and advocate the development of evidence-based standards and guidelines for training programs in EBTs. Although multifaceted and intensive training and consultation may be resource-intensive, we cannot transport EBTs to practice in the public sector unless we develop programs in which clinicians receive sufficient training to implement those treatments competently in their daily practice. We encourage others involved in similar efforts to conduct research on their training efforts and models, which will add to the knowledge of the best methods of disseminating EBTs to the public sector.

Acknowledgments

Preparation of this manuscript was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health (K99 MH080100, PI: Stirman; and P20 MH071905, PI: Beck) and by grants from the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention.

The authors wish to thank Arthur C. Evans, J. Bryce McLaulin, and Regina Buchhofer at the Philadelphia Department of Behavioral Health and Mental Retardation, and clinicians and administrators whose participation in research training and the Beck Initiative Program and valuable feedback allowed us to refine this model. Agencies that participated in the Beck Initiative at the time this article was written include the following: John F. Kennedy Community Mental Health Center and Horizon House, Inc. (Centers of Excellence), Sobriety Through Outpatient, Parkside Recovery, the Mazzoni Center, PATH, Inc., Wedge Medical Center, PMHCC Community Treatment Teams, and the Warren E. Smith Health Center (Frankford High School Clinic). In addition, clinicians at Consortium, Inc., COMHAR, and Hall Mercer participated in training to become research protocol clinicians.

Biographies

Shannon Wiltsey Stirman received her PhD at the University of Pennsylvania, where she also completed a postdoctoral fellowship and served as the program director for the Beck Initiative, a partnership between the University of Pennsylvania and the City of Philadelphia’s Department of Behavioral Health and Mental Retardation. She is currently a clinical research psychologist at the National Center for PTSD Women’s Health Sciences Division and an assistant professor at Boston University.

Sunil S. Bhar received his PhD in clinical psychology from the University of Melbourne. He is senior lecturer of psychology at Swinburne University of Technology. His research is focused on obsessive–compulsive disorder, suicide prevention in older adults, and treatment-related processes.

Megan Spokas received her PhD from Temple University. She served as a trainer and consultant in the Beck Initiative. She is now an assistant professor at La Salle University. Her research interests include cognitive–behavioral treatments for mood and anxiety disorders, suicide prevention, and the sequelae of traumatic events.

Gregory K. Brown received his PhD from Vanderbilt University. He is a research associate professor of clinical psychology in psychiatry at the University of Pennsylvania. His research interests include the effectiveness of cognitive therapy for community-based adult patients who recently attempted suicide, for adolescent patients with suicide ideation, for patients with substance abuse, and recent suicide behavior and for suicidal older men.

Torrey A. Creed received her PhD in clinical psychology from Temple University. She is a research associate in the Center for Family Intervention Science at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia and the lead trainer of the Child and Adolescent Arm of the Beck Initiative of the University of Pennsylvania. Her areas of research and practice include suicide and trauma in adolescence, cognitive therapy, treatment development, and treatment outcome.

Dimitri Perivoliotis received his PhD in clinical psychology from the University of California, San Diego. He is a postdoctoral fellow in the Psychopathology Research Unit at the Department of Psychiatry of the University of Pennsylvania. His areas of research and practice include psychosocial functioning in, and cognitive therapy for, schizophrenia.

Danielle T. Farabaugh received her PsyD in clinical psychology from La Salle University. She is employed as a psychologist and clinical researcher in the Inpatient Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Program at the Coatesville Veterans Affairs Medical Center, Pennsylvania. Her areas of research and practice include the cognitive affective processes of anxiety and trauma, therapeutic outcomes, and program evaluation.

Paul M. Grant received his PhD from the University of Pennsylvania, where he is on the faculty of the School of Medicine. His published work focuses on basic psychopathology (e.g., negative symptoms) and psychosocial treatment (e.g., cognitive therapy) of schizophrenia.

Aaron T. Beck, MD, professor of psychiatry, University of Pennsylvania, is a graduate of Brown University (1942) and Yale Medical School (1946). He received the 2007 Lasker Clinical Medical Science Award. His research interests include cognitive therapy for schizophrenia, suicide prevention, and other mental health disorders.

Contributor Information

Shannon Wiltsey Stirman, The National Center for PTSD, Boston University Medical Center and Boston University.

Megan Spokas, La Salle University.

Torrey A. Creed, The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia

Danielle T. Farabaugh, Coatesville Veterans Affairs Medical Center, Coatesville, Pennsylvania

Sunil S. Bhar, Swinbourne University of Technology

Gregory K. Brown, University of Pennsylvania

Dimitri Perivoliotis, University of Pennsylvania.

Paul M. Grant, University of Pennsylvania

Aaron T. Beck, University of Pennsylvania

References

- Aarons GA. Mental health provider attitudes toward adoption of evidence-based practice: The Evidence-Based Practice Attitude Scale. Mental Health Services Research. 2004;6:61–72. doi: 10.1023/b:mhsr.0000024351.12294.65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aarons GA, Sommerfeld DH, Hecht DB, Silovsky JF, Chaffin MJ. The impact of evidence-based practice implementation and fidelity monitoring on staff turnover: Evidence for a protective effect. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2009;77:270–280. doi: 10.1037/a0013223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abbass A. Small-group videotape training for psychotherapy skills development. Academic Psychiatry. 2004;28:151–155. doi: 10.1176/appi.ap.28.2.151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brosan L, Reynolds S, Moore RG. Self evaluation of cognitive therapy performance: Do therapists know how competent they are? Behavioural and Cognitive Therapy. 2008;36:581–587. [Google Scholar]

- Carter JW, Enyedy KC, Goodyear RG, Arcinue F, Puri NN. Concept mapping of the events supervisees find helpful in group supervision. Training and Education in Professional Psychology. 2009;3:1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Chambless DL, Ollendick TH. Empirically supported psychological interventions: Controversies and evidence. Annual Review of Psychology. 2001;52:685–716. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chorpita BF, Mueller CW. Toward new models for research, community, and consumer partnerships: Some guiding principles and an illustration. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 2008;15:144–148. [Google Scholar]

- Chorpita BF, Yim LM, Donkervoet JC, Amundsen MJ, Serrano A, Burns JA, Morelli P. Toward large-scale implementation of empirically supported treatments for children: A review and observations by the Hawaii empirical basis to services task force. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 2002;9(2):165–190. [Google Scholar]

- Crits-Christoph P, Siqueland L, Chittams J, Barber JP, Beck AT, Frank A, Woody G. Training in cognitive, supportive-expressive, and drug counseling therapies for cocaine dependence. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1998;66:484–492. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.66.3.484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cucciare MA, Weingardt KR, Villafranca S. Using blended learning to implement evidence-based psychotherapies. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 2008;15:299–307. [Google Scholar]

- DH/Mental Health Programme/Improving Access to Psychological Therapies. Improving Access to Psychological Therapies implementation plan: National guidelines for regional delivery. 2008 Retrieved from http://www.dh.gov.uk/en/Publicationsandstatistics/Publications/PublicationsPolicyAndGuidance/DH_083150.

- Fagan A, Hanson K, Hawkins J, Arthur M. Implementing effective community-based prevention programs in the community youth development study. Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice. 2008;6:256–278. [Google Scholar]

- Feeley M, DeRubeis R, Gelfand L. The temporal relation of adherence and alliance to symptom change in cognitive therapy for depression. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1999;67:578–582. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.67.4.578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fixsen DL, Naoom SF, Blase KA, Friedman RM, Wallace F. Implementation research: A synthesis of the literature. Tampa: University of South Florida, Louis de la Parte Florida Mental Health Institute, The National Implementation Research Network; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Ford J, Ford L, D’Amelio A. Resistance to change: The rest of the story. Academy of Management Review. 2008;33:362–377. [Google Scholar]

- Glisson C, Schoenwald S. The ARC organizational and community intervention strategy for implementing evidence-based children’s mental health treatments. Mental Health Services Research. 2005;7:243–259. doi: 10.1007/s11020-005-7456-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glisson C, Schoenwald SK, Kelleher K, Landsverk J, Hoagwood KE, Mayberg S, Green P. Therapist turnover and new program sustainability in mental health clinics as a function of organizational culture, climate, and service structure. Administration and Policy in Mental Health. 2008;35:124–133. doi: 10.1007/s10488-007-0152-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gluhoski V. Misconceptions of cognitive therapy. Psychotherapy. 1994;31:594–600. [Google Scholar]

- Hampson RB, Schulte MA, Ricks CC. Individual vs. group training for foster parents: Efficiency/effectiveness evaluations. Family Relations. 1983;32:191–201. [Google Scholar]

- Henggeler SW, Chapman JE, Rowland MD, Halliday-Boykins CA, Randall J, Shackelford J, Schoenwald SK. State-wide adoption and initial implementation of contingency management for substance abusing adolescents. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2008;76:556–567. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.76.4.556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes J, Mizen S, Jacobs C. Psychotherapy training for psychiatrists: UK and global perspectives. International Review of Psychiatry. 2007;19:93–100. doi: 10.1080/09540260601080888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang WC, Wood JJ, Lin KM, Cheung F. Cognitive-behavioral therapy with Chinese Americans: Research, theory, and clinical practice. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice. 2006;13:293–303. [Google Scholar]

- James I, Blackburn I, Milne D, Armstrong P. Conducting supervision: Novel elements towards an integrative approach. Behavioral and Cognitive Psychotherapy. 2006;35:191–200. [Google Scholar]

- James I, Blackburn I, Milne D, Reichfeldt J. Moderators of trainee competence in cognitive therapy. British Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2001;40:131–141. doi: 10.1348/014466501163580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen-Doss A, Hawley K, Lopez M, Osterberg L. Using evidence-based treatments: The experiences of youth providers working under a mandate. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice. 2009;40:417–424. [Google Scholar]

- Kazdin AE. Evidence-based treatment and practice: New opportunities to bridge clinical research and practice, enhance the knowledge base, and improve patient care. American Psychologist. 2008;63:146–159. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.63.3.146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendall PC, Beidas RS. Smoothing the trail of dissemination of evidence-based practices for youth: Flexibility within fidelity. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice. 2007;38:13–20. [Google Scholar]

- King KP, Lawler PA. Trends and issues in the professional development of teachers of adults. New Directions for Adult & Continuing Education. 2003;98:5–13. [Google Scholar]

- Klein KJ, Knight AP. Innovation implementation: Overcoming the challenge. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2005;14(5):243–246. [Google Scholar]

- Knowles MS. The modern practice of adult education: From pedagogy to andragogy. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall/Cambridge; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Koerner K. What if it were easy and fun? The use of online learning communities. In: Worrell M, editor. Who’s online now? New approaches to using the internet to help train and retrain therapists in cognitive and behavioral treatments; Symposium conducted at the 42nd annual meeting of the Association for Behavioral and Cognitive Therapy; Orlando, FL. 2008. Nov, (Chair) [Google Scholar]

- Lehman WEK, Greener JM, Simpson DD. Assessing organizational readiness for change. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2002;22:197–209. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(02)00233-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levin A. Evidence-based therapies encounter difficulty transitioning into practice. Psychiatric News. 2009;44:15–29. [Google Scholar]

- Linehan MM. Group versus individual assertion training. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1979;47:1000–1002. [Google Scholar]

- Martino S, Ball S, Nich C, Frankforter T, Carroll C. Community program therapist adherence and competence in motivational enhancement therapy. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2008;96:37–48. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.01.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martino S, Gallon R, Ball S, Carroll K. A step forward in teaching addiction counselors how to supervise motivational interviewing using a clinical trials training approach. Journal of Teaching in the Addictions. 2008;6:39–67. [Google Scholar]

- Merriam SB. Andragogy and self-directed learning: Pillars of adult learning theory. New Directions for Adult & Continuing Education. 2001;89:3–14. [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Yahne CE, Moyers TB, Pirritano M, Martinez J. A randomized trial of methods to help clinicians learn motivational interviewing. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2004;72:1050–1062. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.6.1050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miranda J, Azocar F, Organista K, Dwyer E, Arean P. Treatment of depression among impoverished primary care patients from ethnic minority groups. Psychiatric Services. 2003;54:219–225. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.54.2.219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Najavits LM, Weiss RD, Shaw SR, Dierberger AE. Psychotherapists’ views of treatment manuals. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice. 2000;31:404–408. [Google Scholar]

- Norcross JC, Beutler LE, Levant RF, editors. Evidence-based practices in mental health: Debate and dialogue on the fundamental questions. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Palinkas L, Schoenwald S, Hoagwood K, Landsverk J, Chorpita B, Weisz J. An ethnographic study of implementation of evidence-based treatments in child mental health: First steps. Psychiatric Services. 2008;59:738–746. doi: 10.1176/ps.2008.59.7.738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perepletchikova F, Hilt LM, Chereji E, Kazdin AE. Barriers to implementing treatment integrity procedures: Survey of treatment outcome researchers. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2009;77:212–218. doi: 10.1037/a0015232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perepletchikova F, Treat TA, Kazdin AE. Treatment integrity in psychotherapy research: Analysis of the studies and examination of the associated factors. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2007;75:829–841. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.75.6.829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Persons JB. Case formulation-driven psychotherapy. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 2006;13:167–170. [Google Scholar]

- Rogers E. Diffusion of preventive innovations. Addictive Behaviors. 2002;27:989–993. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(02)00300-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roth A, Pilling S. Using an evidence-based methodology to identify the competences required to deliver effective cognitive and behavioural therapy for depression and anxiety disorders. Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy. 2008;36:129–147. [Google Scholar]

- Sackett DL, Rosenberg W, Gray J, Haynes R, Richardson W. Evidence based medicine: What it is and what it isn’t. British Medical Journal. 1996;312:71–72. doi: 10.1136/bmj.312.7023.71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santa Ana EJ, Martino S, Ball SA, Nich C, Frankforter TL, Carroll KM. What is usual about “treatment-as-usual”? Data from two multisite effectiveness trials. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2008;35:369–379. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2008.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt F, Taylor TK. Putting empirically supported treatment into practice: Lessons learned in a children’s mental health center. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice. 2002;33:483–489. [Google Scholar]

- Schoener EP, Madeja CJ, Henderson MJ, Ondersma SJ, Janisse JJ. Effects of motivational interviewing training on mental health therapist behavior. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2006;82:269–275. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2005.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoenwald SK, Carter RE, Chapman JE, Sheidow AJ. Therapist adherence and organizational effects on change in youth behavior problems one year after multisystemic therapy. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research. 2008;35:379–394. doi: 10.1007/s10488-008-0181-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoenwald SK, Hoagwood K. Effectiveness, transportability, and dissemination of interventions: What matters when? Psychiatric Services. 2001;52:1190–1197. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.52.9.1190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheidow AJ, Donohue BC, Hill HH, Ford JD, Henggeler SW. Development of an audiotape review system for supporting adherence to an evidence-based treatment. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice. 2008;39:553–560. doi: 10.1037/0735-7028.39.5.553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sholomskas DE, Syracuse-Siewert G, Rounsaville BJ, Ball SA, Nuro KF, Carroll KM. We don’t train in vain: A dissemination trial of three strategies of training clinicians in cognitive-behavioral therapy. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2005;73:106–115. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.73.1.106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sieber J. When academicians collaborate with community agencies in effectiveness research. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 2008;15:137–143. [Google Scholar]

- Speck M. Best practice in professional development for sustained educational change. ERS Spectrum. 1996;14:33–41. [Google Scholar]

- Stein DM, Lambert MJ. Graduate training in psychotherapy: Are therapy outcomes enhanced? Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1995;63:182–196. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.63.2.182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stirman SW, Buchhofer R, McLaulin JB, Evans AC, Beck AT. The Beck Initiative: A public academic collaborative partnership to implement cognitive therapy in a community behavioral health system. Psychiatric Services. 2009;60:1302–1304. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.60.10.1302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stirman SW, Crits-Christoph P, DeRubeis RJ. Achieving successful dissemination of empirically supported psychotherapies: A synthesis of dissemination theory. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 2004;11:343–359. [Google Scholar]

- Swenson C, Torrey W, Koerner K. Implementing dialectical behavior therapy. Psychiatric Services. 2002;53:171–178. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.53.2.171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weaver T, Madden P, Charles V, Stimson G, Renton A, Tyrer P, Ford C. Comorbidity of substance misuse and mental illness in community mental health and substance misuse services. British Journal of Psychiatry. 2003;183:304–313. doi: 10.1192/bjp.183.4.304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woltmann EM, Whitley R, McHugo GJ, Brunette M, Torrey WC, Coots L, Drake R. The role of staff turnover in the implementation of evidence-based practices in mental health care. Psychiatric Services. 2008;59:732–737. doi: 10.1176/ps.2008.59.7.732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]