Dear editor:

Pigmented purpuric dermatoses (PPDs) are a group of chronic and relapsing dermatoses which are morphologically different but histopathologically indistinguishable1. They are characterized by petechiae, pigmentation, and occasionally, telangiectasia, and typically localized to the lower limbs. The cause of PPDs is largely unknown. These dermatoses are histopathologically similar to perivascular lymphocyte infiltration, erythrocyte extravasation, and hemosiderin deposition. Although clinical subclassification attempts to account for clinical variations between PPDs, overlapping categories may make differentiation challenging. We describe 2 patients with PPD with extensive cutaneous involvement of both arms and legs, initially diagnosed as angioma serpiginosum.

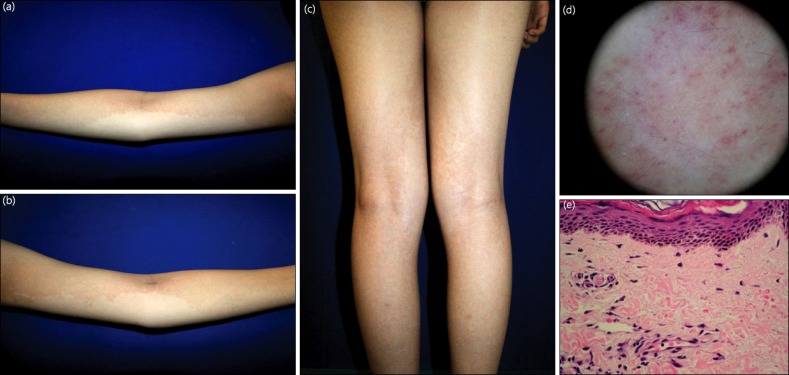

A 16-year-old female patient (case 1) presented with a 4-month history of asymptomatic red-brown hyperpigmented patches on the arms and legs. She had no history of a bleeding disorder, and her medical and family history was unremarkable. She reported no trauma to the area and denied intake of any medication. Upon clinical examination, well-demarcated, brownish pigmentation over the extremities, especially on the arms, was observed (Fig. 1a~c). Dermoscopy showed multiple small purpuric globules over an orange-brown background (Fig. 1d). No abnormalities were found on routine laboratory tests. A punch biopsy sample obtained from the left arm showed mild epidermal hyperkeratosis, orthokeratosis, and perivascular lymphocyte and histocyte infiltration in the papillary dermis with focal extravasations of erythrocytes (Fig. 1e), suggesting PPD. The patient was treated with pentoxifylline 400 mg bid for 1 month. In a follow-up visit, she showed significant improvement of the lesion.

Fig. 1.

(a~c) Brownish hyperpigmented patches on both arms and legs in case 1. (d) Dermoscopy showing multiple purpuric globules over an orange-brown background. (e) Histopathological analysis showing perivascular lymphocytic infiltrates with extravasation of erythrocytes in the papillary dermis (H&E, ×400).

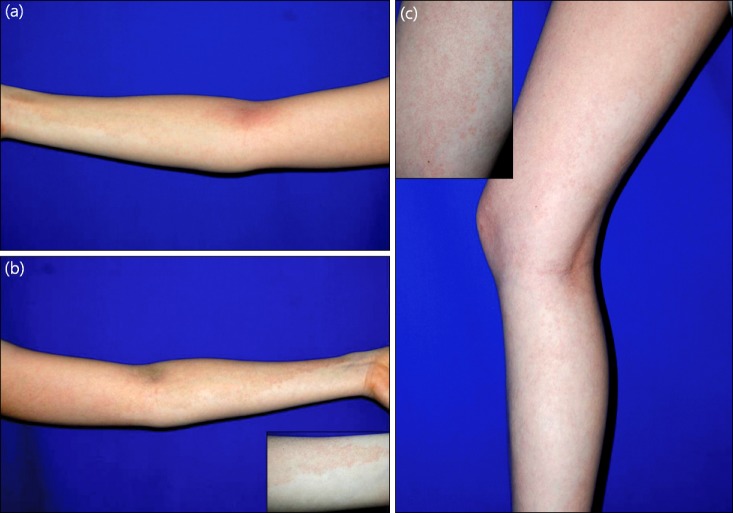

A 20-year-old female patient (case 2) had a 2-year history of red-brown hyperpigmented patches in a band-like pattern on the arms and legs without subjective symptoms. Clinical examination showed grouped pigmented, purpuric, and slightly erythematous lesions on the extremities (Fig. 2). The patient reported no history of infection, trauma, or medicine intake. Routine laboratory examination showed no abnormalities, and skin biopsy confirmed PPD. She was treated with pentoxifylline 400 mg bid. After 2 months of treatment, the lesion disappeared.

Fig. 2.

(a~c) Red-brown hyperpigmented patches on the extremities in case 2.

The present cases are good examples of the difficulties in the clinical subclassification of PPD. The well-demarcated, brownish to erythematous patches occurring in a band-like pattern clinically mimicked angioma serpiginosum, or unilateral nevoid telangiectasia (UNT), but the histopathologic examination confirmed PPD. Histopathologically, angioma serpiginosum shows solitary or widely grouped dilated capillaries in the papillary dermis, but there is no erythrocyte diapedesis or hemosiderin pigmentation2. UNT reveals numerous thin-walled dilated vessels in the upper and middle dermis, and to a lesser extent, in the deeper part of dermis3. Dermoscopy may provide additional clinical information for the differential diagnosis. Dermoscopic examination of PPD shows purpuric globules over a purpuric, and later, orange-brown background, as observed in our two patients4. Dermoscopic evaluation of angioma serpiginosum reveals numerous, small, relatively well-demarcated, round to oval red lagoons2. To our knowledge, dermoscopic features of UNT have not been described in the Korean or English literature. We think that multiple superficial telangiectatic vessels could be observed on dermoscopy as UNT is characterized by superficial telangiectatic lesions distributed along the dermatomes, usually on the upper body.

Because the clinical and histopathological differences between PPDs are minor and frequently overlap, differentiation is often difficult. One of the subtypes of PPD is Schamberg disease, and the lesions in this disease appear mostly on the lower legs. However, Schamberg lesions may occur anywhere on the body with pinhead-sized reddish puncta resembling grains of cayenne-pepper. The disease is generally asymptomatic and persistent1. Osment et al.5 suggested another subgroup called transitory PPD or Schamberg-like dermatitis. The major differences between Schamberg disease and transitory PPD are that transitory PPD is usually pruritic and has a more favorable prognosis in that it tends to clear within a few months after onset5. Abe et al.6 reported an interesting case of a 23-year-old female with a 4-month history of well-demarcated, brownish hyperpigmented, reticulated pigmentation over the bilateral forearm, thigh, and trunk. As with our first patient, the lesion mimicked angioma serpiginosum, and did not meet the typical characteristics of the established subtypes of PPD. They concluded that the diagnosis of transitory PPD was most compatible because the patient had slight pruritus and the lesion disappeared 17 months after the initial occurrence. We excluded the diagnosis of transitory PPD because the patient reported in this study did not have pruritus.

Unilateral linear capillaritis, also named quadrantic capillaropathy or unilateral pigmented purpuric eruption, is clinically characterized by an extensive linear or segmental distribution of pigmented purpuric macules and a favorable course7. To date, 12 cases of unilateral linear capillaritis have been reported8. The macules are frequently located on the lower extremities, but distribution on an upper extremity has also been reported8. However, as the names "unilateral linear capillaritis" or "quadrantic capillaropathy," suggest, the disease usually involves only 1 extremity. Our cases are unusual because all extremities were involved. There was no trauma, coagulation defect, or contact dermatitis.

The cause of PPD is unknown, but cell-mediated immunity might play a role9. The infiltrate in PPD consists of lymphocytes and histiocytes. This inflammatory infiltrate leads to vascular fragility and subsequent leakage of erythrocytes. Treatment of PPD often yields unsatisfactory outcomes, although preventive management of the suspected causes might help in some cases1. Topical corticosteroid therapy may be of some help, especially for pruritus, but as always prolonged use should be avoided. An encouraging effect of pentoxifylline, which is supposed to affect T-cell adherence to endothelial cells and keratinocytes, has been described10-14. The therapeutic effect of pentoxifylline was obvious in these two patients because the lesions in both disappeared within 1 and 2 months of treatment. During follow-up (5 months for case 1 and 2 years for case 2), recurrence was not observed. The present cases are notable for their extensive cutaneous involvement which showed good response to pentoxifylline. These cases illustrate that PPD should be considered in the differential diagnosis of a linear pigmentary disorder involving all extremities.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This study was supported by a grant of the Korean Heath Technology R&D Project, Ministry of Health and Welfare, Republic of Korea (A070001).

References

- 1.Sardana K, Sarkar R, Sehgal VN. Pigmented purpuric dermatoses: an overview. Int J Dermatol. 2004;43:482–488. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2004.02213.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ilknur T, Fetil E, Akarsu S, Altiner DD, Ulukuş C, Güneş AT. Angioma serpiginosum: dermoscopy for diagnosis, pulsed dye laser for treatment. J Dermatol. 2006;33:252–255. doi: 10.1111/j.1346-8138.2006.00061.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wilkin JK, Smith JG, Jr, Cullison DA, Peters GE, Rodriquez-Rigau LJ, Feucht CL. Unilateral dermatomal superficial telangiectasia. Nine new cases and a review of unilateral dermatomal superficial telangiectasia. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1983;8:468–477. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(83)70051-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vazquez-Lopez F, Garcíia-Garcíia B, Sanchez-Martin J, Argenziano G. Dermoscopic patterns of purpuric lesions. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:938. doi: 10.1001/archdermatol.2010.162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Osment LS, Noojin RO, Lewis RA, Lupton CH. Transitory pigmented purpuric eruption of the lower extremities. Arch Dermatol. 1960;81:591–598. doi: 10.1001/archderm.1960.03730040095017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Abe M, Syuto T, Ishibuchi H, Yokoyama Y, Ishikawa O. Transitory pigmented purpuric dermatoses in a young Japanese female. J Dermatol. 2008;35:525–528. doi: 10.1111/j.1346-8138.2008.00514.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mar A, Fergin P, Hogan P. Unilateral pigmented purpuric eruption. Australas J Dermatol. 1999;40:211–214. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-0960.1999.00364.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ma HJ, Zhao G, Liu W, Dang YP, Li DG. Unilateral linear capillaritis: two unusual Chinese cases. Eur J Dermatol. 2007;17:160–163. doi: 10.1684/ejd.2007.0132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tristani-Firouzi P, Meadows KP, Vanderhooft S. Pigmented purpuric eruptions of childhood: a series of cases and review of literature. Pediatr Dermatol. 2001;18:299–304. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1470.2001.01932.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wahba-Yahav AV. Schamberg's purpura: association with persistent hepatitis B surface antigenemia and treatment with pentoxifylline. Cutis. 1994;54:205–206. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kano Y, Hirayama K, Orihara M, Shiohara T. Successful treatment of Schamberg's disease with pentoxifylline. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997;36:827–830. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(97)70032-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Panda S, Malakar S, Lahiri K. Oral pentoxifylline vs topical betamethasone in Schamberg disease: a comparative randomized investigator-blinded parallel-group trial. Arch Dermatol. 2004;140:491–493. doi: 10.1001/archderm.140.4.491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Burkhart CG, Burkhart KM. Pentoxifylline for Schamberg's disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;39:298. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(98)70103-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Oh ST, Yoon SY, Lee SD, Park HJ, Lee JY, Cho BK. A case of pigmented purpuric lichenoid dermatitis of Gougerot-Blum treated by pentoxifylline. Korean J Dermatol. 2005;43:1544–1547. [Google Scholar]