Abstract

Background

Cytotoxic T-Lymphocyte Antigen-4 (CTLA-4) is one of the critical inhibitory regulators of early stages of T cell activation and proliferation which opposes the actions of CD28-mediated co-stimulation. Anti-CTLA-4 therapy has been effective clinically in enhancing immunity and improving survival in patients with metastatic cancer. Sepsis is a lethal condition which shares many of the same mechanisms of immune suppression with cancer.

Objectives

Given the similarities in immune defects in cancer and sepsis, we examined the ability of anti-CTLA-4 antibody to block apoptosis, reverse the immunosuppression of sepsis, and improve survival in the cecal ligation and puncture (CLP) model.

Measurements

Mice underwent sham or CLP and spleens harvested at various time points after surgery. Expression of CTLA-4 on CD4, CD8, and regulatory T cells was quantitated. Anti-CTLA-4 was administrated 6 and 24hrs after surgery. Spleens were harvested at 48hrs post- surgery and apoptosis and cytokine production determined. Seven day survival studies were also conducted.

Results

Expression of CTLA-4 on CD4, CD8, and regulatory T cells increased during sepsis. Anti-CTLA-4 therapy decreased sepsis-induced apoptosis but had little effect on pro- or anti-inflammatory cytokines. There was a dose dependent effect of anti-CTLA-4 on survival. At high dose, anti-CTLA-4 worsened survival, but at lower doses, survival was significantly improved.

Conclusion

Survival in sepsis depends upon the proper balance between the pro- and anti-inflammatory/immunologic systems. Anti-CTLA-4 based immunotherapy offers promise in the treatment of sepsis but care must be used in the timing and dose of administration of the drug to prevent adverse effects.

Keywords: cell death, cytokines, lymphocytes, endotoxin, apoptosis

Introduction

Immunotherapy, i.e., pharmacologic modulation of the host immune system to combat disease is now rapidly advancing on a myriad of fronts (1–4). One of the most exciting approaches is modulation of lymphocyte function by regulating the positive and negative co-stimulatory molecules that are present on the cell surface. Lymphocyte activation is carefully balanced by positive and negative co-stimulatory molecules that prevent unbridled T cell function (5). CD28 is the classic positive co-stimulatory molecule that, in conjunction with stimulation through the T cell receptor, induces T cells to produce cytokines such as IL-2 and IFN-γ that have wide ranging effects on other cells. CTLA-4, also known as CD152, is a protein that plays an important negative regulatory role in the immune system (6–8). CTLA-4 is a member of the immunoglobulin superfamily which is expressed on the surface of T cells and transmits an inhibitory signal to CD4 and CD8 T cells (6, 8–10). CTLA-4 competes with CD28 for binding to CD80 and CD86 which are present on antigen-presenting cells. In contrast to CD28, CTLA-4 transmits an inhibitory signal to T cells that prevents their activation (6–8). Fusion proteins of CTLA-4 and antibodies (CTLA4-Ig), which function to activate the CTLA-4 inhibitory pathway, have been used in clinical trials to prevent transplant rejection and to ameliorate the symptoms of rheumatoid arthritis (5, 8–10). Conversely, there is increasing interest in the possible therapeutic benefits of blocking CTLA-4 as a means of inhibiting immune system tolerance to tumors and thereby providing a potentially useful immunotherapy strategy for patients with cancer (8, 9). Some significant success has occurred in patients with widely metastatic malignant melanoma who failed all previous therapies and who were treated with a CTLA-4 blocking antibody (3).

Another disease in which immunotherapy offers great promise is sepsis (4). Septic shock has traditionally been viewed as an excessive systemic inflammatory reaction to invasive microbial pathogens yet efforts to improve outcome in septic patients with inhibitors of pro-inflammatory cytokines and mediators have been unsuccessful. This has led investigators to reexamine the pathophysiology of sepsis (11–13). Occasional patients present with an overly exuberant immune response to highly virulent pathogens, e.g. meningococcemia, overwhelming post-splenectomy infection, and rapidly succumb from an exaggerated systemic inflammatory response. However, the vast majority of septic patients today survive their initial insult only to end up in the intensive care unit with sepsis-induced multi-organ dysfunction over the ensuing days to weeks. Sepsis-induced immunosuppression is increasingly recognized as the overriding immune dysfunction in these vulnerable patients (14–16).

Although there are a number of mechanisms responsible for or contributing to the immunosuppression of sepsis, one likely critical mechanism is increased expression of negative co-stimulatory molecules. Recent studies have shown that blockade of PD-1, a potent negative co-stimulatory molecule with actions similar to CTLA-4, can improve survival in sepsis (17, 18). Although not extensively investigated, studies of the role of CTLA-4 in chronic infections have demonstrated that CTLA-4 adversely affected pathogen clearance in Helicobacter pylori, Leishmania, and Trypanosoma infections of mice (19–22). Given these studies, our laboratory investigated the ability of anti-CTLA-4 to improve survival in a clinically relevant mouse model of sepsis, i.e., the cecal ligation and puncture (CLP) model. In addition, we tested anti-CTLA-4 therapy in a two-hit model of peritonitis followed later by fungal sepsis. This model has a much more protracted time course which reflects the clinical scenario that occurs in many patients. We also examined the expression of CTLA-4 on T regulatory cells. A high percentage of the potent immunosuppressor T regulatory cells (T regs) are known to express CTLA4 which is felt to be an important mechanism for their immunosuppressive effect. Therefore, the percentage of T regs expressing CTLA-4 was quantitated by flow cytometry at various time points following sham or CLP surgery

Materials and Methods

Mice

Male CD-1 (Charles River) or C57BL6 (Jackson Laboratory) male mice ~20 to 25 g body weight and 6–8 weeks of age were employed for all studies. Mice were housed for at least 1 week prior to use.

Antibodies

Antibodies were purchased from BD Pharmingen (San Diego, CA), Cell Signaling (Danvers, MA), eBiosciencs (San Jose, CA), or Jackson ImmunoResearch (West Grove PA).

BD Pharmingen

CD4-FITC (Cat. #553729), CD8-PECy5 (Cat. #553034); B220-PECy5 (a marker to identify B cells) (Cat. #553091); CD11c-FITC (Cat. #553801) and MHC2-PE (Cat. #557000) – these two antibodies were used to identify dendritic cells; and CD25-PE (Cat. # 553075); the apoptosis marker, cleaved caspase-3 (Cat. #9661). CD44-PE (Cat.#553134), CD62L-PECy5(Cat.#15-021-82).

eBioscience

DX5-FITC (a marker to identify NK cells) (Cat. # 11-5971-85). Foxp3-APC (a marker to identify regulatory T cells) (Cat. # 17-5773-82).

Jackson ImmunoResearch

A secondary PE-labeled donkey anti-rabbit IgG F(ab')2-fragment (Cat. #711-116-152).

Anti- CTLA-4 Antibody

An anti-mouse CTLA-4 monoclonal antibody, clone 63828 (Cat#MAB434) was purchased from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN) and was employed for all studies. The antibody was diluted in PBS to a total volume of 15 mls (5mg) and then aliquoted and frozen at minus 80 degrees C. 50 ug of the anti-CTLA-4 antibody in 150 ul of PBS was injected i.p. per mouse.

Cecal ligation and puncture (CLP) sepsis model

All animal studies were approved by the Washington University Animal Studies Committee. The CLP model as developed by Chaudry et al. (23) was used to induce intra-abdominal peritonitis, as described previously (24–26). Mice were anesthetized with isoflurane and a midline abdominal incision was made. The cecum was mobilized, ligated below the ileocecal valve, and punctured twice with a 25-gauge needle. The abdomen was closed in two layers and the mice were injected subcutaneously with 2.0 ml of PBS. Cohorts of mice used for acute studies mice were treated with anti-CTLA-4 or the PBS 6 and 24 hrs i.p. after sham or CLP surgery. For survival studies, mice underwent CLP as described above and anti-CTLA-4 or the PBS diluent was injected i.p. 6 and 24 hrs after the operation. A single dose of the broad spectrum antibiotic imipenem (25 mg/kg body wt) was administered subcutaneously 4–6 h post-operatively and survival was recorded for 7 days.

Two-Hit Model of CLP followed by Candida Albicans

In addition to the CLP model, we tested the ability of anti-CTLA-4 to improve survival in a two-hit model of CLP followed by Candida albicans. The two-hit model was developed because it produces a more prolonged form of sepsis that reproduces the depressed immunity that occurs in patients with protracted sepsis (manuscript in progress). In the two-hit Candida albicans model of sepsis, mice surviving at 4 days post-CLP were intravenously injected via tail vein with 60 μl of Candida albicans as a second infectious insult. The bacterial suspension of Candida albicans was optically registered at 0.5 A600 and corresponded to~ 1 × 109 CFU/ml. Three doses of anti-CTLA-4 (33 μg/mouse) were injected i.p. 2, 5 and 7 days after second hit. The control group was treated identically except that PBS was injected. Survival was recorded for 10 days following second hit.

FACS Analysis: cell phenotyping and quantitation of apoptosis

Spleens were harvested and splenocytes dissociated as previously described. Isolated splenocytes were prepared by gently pressing the organ through a 70-micron filter; cells were then washed and red blood cells lysed as previously described (24–26). Following red blood cell lysis, cells were washed and labeled using pretitrated antibodies to particular cell phenotypes, i.e., CD4, CD8, B, etc. were determined via flow cytometric analysis using a BD FACScan as described previously (24). T regulatory cells (T regs) were identified by intracellular staining for the transcription factor Foxp3 as recommended by the manufacturer. The degree of apoptosis was determined by staining for active caspase-3 as described previously (24–26).

Cytokine analysis

Approximately 48 h post-surgery, mice were anesthetized and spleens harvested. Equal numbers of viable splenocytes (10×106/ml) were stimulated overnight with anti-CD 3/28. Supernatant was obtained from culture media at 24 h after incubation. Cytokines from supernatants of in vitro culture assays and serum were quantitated using Bio-plex system (BIO RAD) per the manufacturer's recommendations as previously described. The lower limits of detection were IL-6 (5 pg/ml), TNF-α (7.3 pg/ml), IL-10 (17.5 pg/ml), and IFN-γ (2.5 pg/ml).

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed with the statistical software Prism (GraphPad, San Diego, USA). Data are reported as the mean ± SEM. One-way ANOVA with Tukey's multiple comparison tests was used to analyze data in which there were more than two groups. For survival studies, a log rank test was used. Significance was reported at p < 0.05.

Results

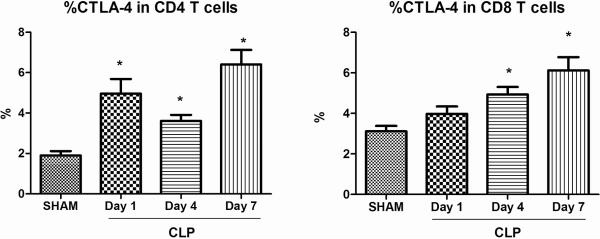

CTLA-4 expression on CD4 and CD8 T cells increases during sepsis

Splenocytes were harvested at various time-points after sham and CLP surgery and CTLA-4 expression on CD4 and CD8 T cells was measured on unfixed cells. The expression of CTLA-4 on cells from sham operated mice did not vary over time and is therefore presented as a combined graph for the single 24 hr time point following surgery. Compared to sham operated mice, the expression of CTLA-4 on CD4 T cells of CLP mice increased by ~ 2.5-fold, 1.9-fold and 3.4-fold respectively by day 1, day 4 and day 7 respectively (p<0.05). The expression of CTLA-4 on CD8 T cells of CLP mice was significantly higher at day 4 and day 7 (p<0.05) (Figure 1).

Figure 1. CTLA-4 expression temporally increases on CD4 and CD8 T cells in sepsis.

CTLA-4 expression was measured in isolated splenocytes via flow cytometry at various time-points. CTLA-4 expression increases on splenic CD4 T cells 1 day after sepsis when compared with sham and remains high at 4 days and 7 days. CTLA-4 expression increases on splenic CD8 T cells after sepsis at 4 days and remains elevated at 7 days. Number of mice for sham, n = 16; CLP, n = 10–20 (*, P < 0.05).

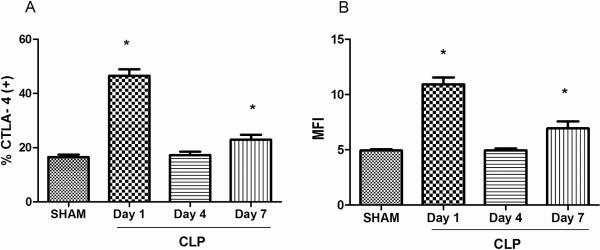

CTLA-4 expression on T regulatory cells increases during sepsis

A high percentage of the potent immunosuppressor T regulatory cells (T regs) are known to express CTLA4 which is felt to be an important mechanism for their immunosuppressive effect. Therefore, the percentage of T regs expressing CTLA-4 was quantitated by flow cytometry at various time points following sham or CLP surgery. Splenocytes were stained for CD4 and for CTLA-4 expression followed by intracellular staining for Foxp3 to identify T regs. In addition, the mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of CTLA-4 expression on CD4+ T regs was quantitated. The MFI is an indication of the number of surface receptors/cell and was calculated by subtraction of the non-specific fluorescence of the isotype control antibody from the fluorescence of the antibody specific to the Foxp3. Compared to sham, the expression of CTLA-4 on T regs of CLP mice was significantly higher at day 1 and day 7 (p<0.05). Similarly, the MFI of CTLA-4 on T regs was significantly higher in CLP mice at day 1 and day 7 after surgery compared to sham mice (p<0.05) (Figure 2).

Figure 2. CTLA-4 expression temporally increases on CD4+ CD25+ Foxp3+ regulatory T cells (Tregs) in sepsis.

CTLA-4 expression was measured in isolated splenocytes via flow cytometry at various time-points. CTLA-4 expression increases on Tregs 1 day after sepsis when compared with sham and remains high at 7 days. B MFI of CTLA-4 on Tregs increased at day 1 and 7 after CLP surgery. Number of mice for sham, n = 10; CLP, n = 5–10 (*, P < 0.05).

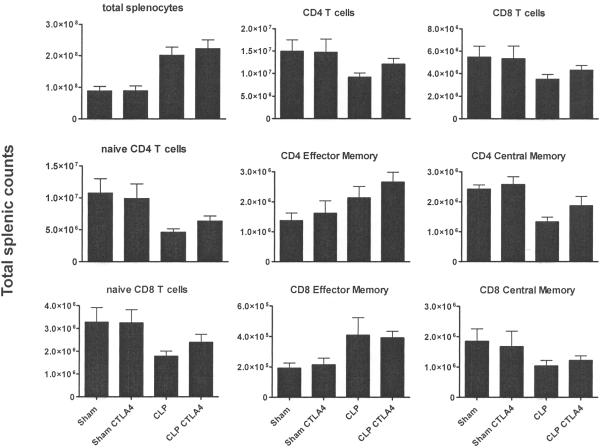

Effect of anti-CTLA-4 on naïve, central, and effector memory CD4 and CD8 T cells

The effect of anti-CTLA-4 on naïve (CD44lo/CD62Lhi), central memory (CD44hi/CD62Lhi), and effector memory (CD44hi/CD62Llo) CD4 and CD8 T cells in spleen were determined at 7 days after sham or sepsis surgery. Mice were treated with 50μg of anti-CTLA-4 per mouse at days 1,3, and 5 post surgery. Spleens were harvested at day 7 post surgery and immunophenotyping performed. The results demonstrated a trend toward an increase in CD4 and CD8 T cells but this did not reach statistical significance (Figure 3). Similarly, there was a trend toward an increase in naïve, effector memory, and central memory CD4 and CD8 T cells but this increase did not obtain significance.

Figure 3. Anti-CTLA-4 Effects on Total Splenocyte Counts and Naïve and Effector Cells.

Sham or septic CD1 mice were treated with 50 ug of anti-CTLA-4 per mouse at day 1, 3 and 5.Mice were sacrificed at day 7. Spleen was harvested, and central memory, naïve, and effector memory T cells subsets were assessed for CD4 and CD8 T cells via flow cytometry. Sham, n = 6; sham+anti-CTLA-4, n=6; CLP (CLP + PBS), n = 8; CLP + anti-CTLA-4, n = 8; results from two combined studies.

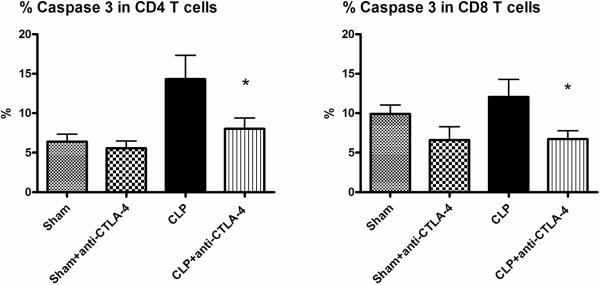

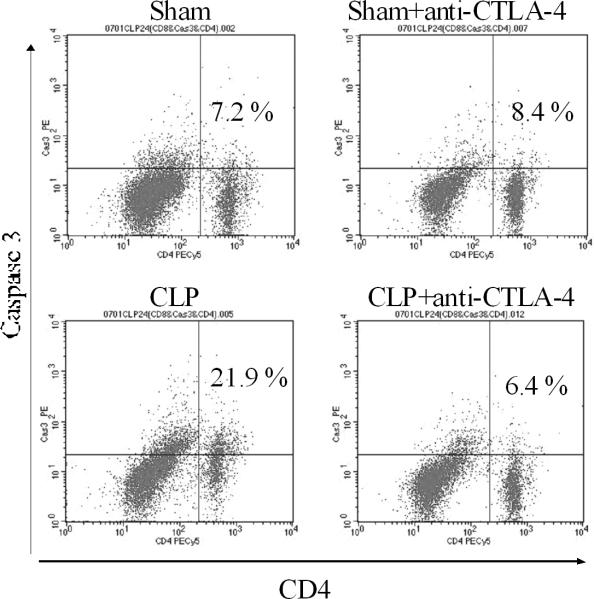

Anti-CTLA-4 prevented sepsis-induced lymphocyte apoptosis

Apoptosis was quantitated 48 hrs after surgery in sham and septic mice that were treated with anti-CTLA-4 antibody (50μg/mouse) or PBS 6 and 24 hrs after surgery. Compared with sham-operated mice, sepsis induced a marked increase in apoptosis (Figure 4). Mice treated with anti-CTLA-4 had an approximately 50% reduction in sepsis-induced apoptosis in CD4 and CD8 T cells. A typical example of the effect of anti-CTLA-4 to decrease sepsis-induced apoptosis as detected by the caspase 3 assay is presented in Figure 5.

Figure 4. CTLA-4 blockade inhibits splenic T cell apoptosis.

Mice underwent sham or CLP surgery and 6, 24 hrs later, had administration of anti-CTLA-4 antibody or PBS. At 48 h after surgery, splenocytes were harvested. Apoptosis was quantitated by active caspase-3. Compared with sham, CLP causes significant increases in apoptosis as evaluated by quantitation of active caspase-3, which was prevented by treatment with anti-CTLA-4 antibody. Each figure is an aggregate of two to three experiments; sham, n = 11; sham+anti-CTLA-4, n=11; CLP (CLP + PBS), n = 16; CLP + anti-CTLA-4, n = 16; (*, P < 0.05, for CLP+anti-CTLA-4 versus CLP + PBS).

Figure 5. Anti-CTLA-4 therapy inhibits splenic T cell apoptosis.

Flow cytometry dot plot showing the effect of anti-CTLA-4 antibody to decrease apoptosis, as indicated by the decrease in CD4 T cells positive for active caspase 3 (right upper quadrant of each dot plot). (n=one representative animal per group).

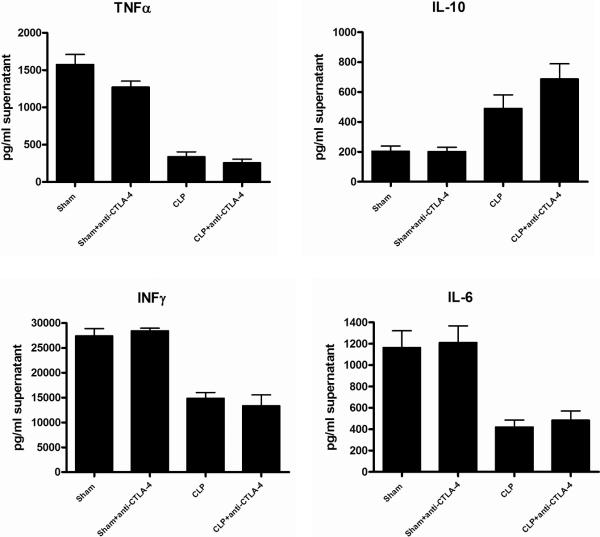

Anti-CTLA-4 treatment does not significantly alter cytokine production in sepsis

Analysis of cytokine levels from plasma taken 48 hrs after CLP did not reveal any differences between CLP mice that received anti-CTLA-4 or CLP controls (data not shown). In order to determine if stimulated cytokine production over 24 hrs might provide a better indicator of CTLA-4's possible effects on T cell function, isolated splenocytes (2 ×106) from sham, sham mice treated with anti-CTLA-4, CLP, and CLP mice treated with anti-CTLA-4 antibody were stimulated overnight with anti-CD3/anti-CD28. Viability was determined using a Beckman Vicell counter using trypan blue exclusion and was greater than 85% for sham and septic. Analysis of cytokines from splenocyte supernatants showed a reduction in CD3/CD28 stimulated cytokines in mice that had CLP versus sham. However, there was no difference in cytokines in CLP mice versus CLP mice treated with anti-CTLA-4 (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Effect of anti-CTLA-4 on splenocyte cytokine production.

Sham- or CLP-operated mice were treated with anti-CTLA-4 or PBS at 6 and 24 h after surgery. Mice were sacrificed 48h later and harvested splenocytes (2×106/well) were stimulated over night with anti-CD3/CD28. Supernatants were obtained and cytokines quantitated using a microbead Bioplex system. Each figure is an aggregate of two to three experiments; sham, n = 6; sham+anti-CTLA-4, n=6; CLP (CLP + PBS), n = 11; CLP + anti-CTLA-4, n = 9.

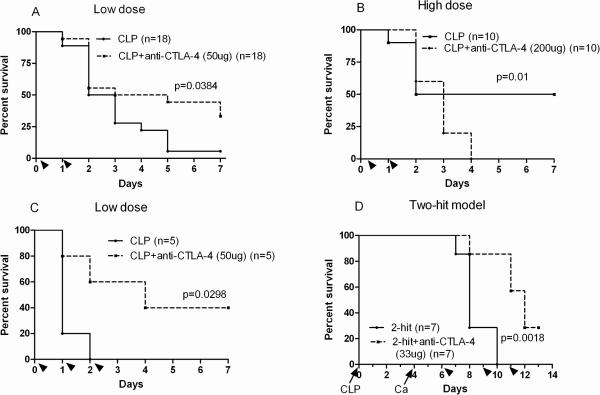

Anti-CTLA-4 improves survival in two models of sepsis

The efficacy of anti-CTLA-4 was tested in two models of sepsis with differing time courses and differing pathogenic mechanisms. CLP-operated CD-1 mice treated with 50μg/mouse of anti-CTLA-4 had a marked improvement in survival compared to controls, p = 0.038 (Figure 7A). It is important to note however that when larger doses of anti-CTLA-4 (200μg/mouse) were employed, the treatment was associated with worsened outcome (Figure 7B). In order to verify the protective effects of low dose anti-CTLA-4, it was tested in a second strain of mice, i.e., C57BL6. The C57BL6 mice differ from the CD-1 mice in that they are an inbred strain as opposed to CD-1 which is an outbred strain. Survival data from the C57BL/6 mice confirmed that CLP-operated mice treated with low dose anti-CTLA-4 had a significantly higher survival rate compared to controls, p = 0.0298 (Figure 7C). Anti-CTLA-4 was also tested in the two-hit model of CLP followed by intravenous Candida albicans. This two-hit model has a much more delayed time course thereby potentially allowing for further engagement of the adaptive immune system. A lower dose of 33 μg/mouse of anti-CTLA-4 antibody was used in the fungal studies. As demonstrated, anti-CTLA-4 did cause an improvement in survival compared to controls in the fungal sepsis model as well (Figure 7D).

Figure 7. Anti-CTLA-4 improves survival in two models of sepsis.

A. CD-1 mice underwent CLP and 1.5 hrs later, were injected with 50 μg of anti-CTLA-4 antibody or PBS per mouse. A second injection of the anti-CTLA-4 antibody or PBS was administered at 24 h after surgery. Survival was recorded for 7 days. CD-1 mice treated with blocking antibodies to CTLA-4 had an improved 7-day survival (33.3%) compared with mice treated with PBS (5.6%; P<0.05). B. When survival studies using higher doses of the anti-CTLA-4 antibody (200 μg/mouse) were used, sepsis survival was worsened. C. In order to confirm the beneficial effect of low dose anti-CTLA-4 antibody, survival studies were repeated in C57BL6 mice. The findings in the C57BL/6 mice confirmed the CLP-operated mice treated with low dose anti-CTLA-4 had a significantly higher survival rate (40%) compared to controls (0%; P<0.05). D. The effect of anti-CTLA-4 antibody in a more protracted model of sepsis consisting of CLP followed 4 days later by i.v. injection of Candida albicans was conducted. Mice treated with anti-CTLA-4 antibody had an improved survival compared to control mice. Three doses of (33 ug/mouse of anti-CTLA-4 antibody anti-CTLA-4 were injected i.p. 2, 5 and 7 days after Candida albicans. Arrow heads indicate time of injection of anti-CTLA-4 antibody. The arrows indicate time of CLP and Candida albicans.

Discussion

There are a number of significant implications from the present study. First, these results provide further support for the concept that late deaths in sepsis may be due to an impaired immune response. The work herein demonstrates a progressive increase in expression of the potent negative co-stimulatory molecule CTLA-4 in CD4 and CD8 T cells. Blocking CTLA-4 led to a decrease in sepsis-induced apoptosis and improved survival in both the CLP model and in a delayed two-hit model of fungal sepsis. These findings are consistent with earlier work on PD-1, another powerful negative co-stimulatory molecule, which showed improved survival in sepsis in animals that had inhibition of the PD-1/PD-L1 pathway (17, 18). However, it is also very important to note that at high doses, anti-CTLA-4 antibody worsened survival. Collectively, these results support the emerging concept that survival in sepsis is dependent upon the proper balance between the pro- and anti-inflammatory immunologic mediated responses (11–14). A number of new immune based sepsis therapies are being tested in sepsis and an important message of the present study is that timing of administration and proper dosing of the immune based therapy will be essential. A considerable effort is now underway to “immunophenotype” patients with sepsis in order to determine the stage of sepsis, i.e., the hyper-inflammatory or hypo-inflammatory phase of sepsis (12–14). These results suggest that quantitation of expression of CTLA-4, PD-1, and other co-stimulatory molecules on circulating T cells may be useful in this regard and these studies are currently underway in the laboratory (unpublished results).

Although few studies have examined the potential role of CTLA-4 in infectious diseases, published studies are consistent with the present work (19–22). Johanns et al. showed that CTLA-4 expressing T reg cells inhibited the ability of mice to eliminate infection due to a virulent Salmonella strain (20). Moreover, T reg expression of CTLA-4 directly paralleled changes in suppressive potency, and the beneficial effects of deletion of T reg cells on pathogen clearance could be largely recapitulated by CTLA-4 in vivo blockade. Together, these results suggest that it is CTLA-4 mediated T reg immunosuppression that is critical in preventing the host from eliminating certain invasive pathogens. The current results did demonstrate increased CTLA-4 expression in T regs (Figure 2). Martins et al. evaluated the importance of CTLA-4 to the immune response against the intracellular protozoan, Trypanosoma cruzi, the causative agent of Chagas' disease (21). These investigators observed a progressive increase in expression of CTLA-4 in spleen cells from infected mice and showed that blockade of CTLA-4 improved pathogen clearance. These two studies together with our finding of improved survival in sepsis in mice treated with anti-CTLA-4 provide strong support for future studies examining the role of inhibiting CTLA-4 in sepsis.

Additional evidence for the potential efficacy of anti-CTLA-4 in the therapy of sepsis is provided by encouraging results in cancer trials (3, 8, 9). There are many similarities between the immunosuppressive mechanisms seen in sepsis and in patients with cancer (4). For example, patients with cancer have increased T regulatory cells, increased myeloid derived suppressor cells, and increased expression of negative co-stimulatory molecules such as CTLA-4 and PD-1/PD-L1. Thus, positive results of anti-CTLA-4 based therapy in cancer lend support to its potential use in sepsis. A key study demonstrating the ability of blockade of CTLA4 to enhance immune function in patients with cancer was conducted by Hodi et al. (3). These investigators administered anti-CTLA4 to over 600 patients with unresectable malignant melanoma and survival was improved from 6 to 10 months. Importantly, a subset of patients had a durable response with a percentage of patients believed to be in long term remission. This is a remarkable outcome given the dismal long term survival in patients with stage 3 and stage 4 metastatic melanoma that were enrolled in this study. Anti-CTLA4 antibody based therapy is being investigated in a number of other cancers including bladder, prostate, and renal cancer and beneficial clinical responses are being recorded. In short, anti-CTLA4 is a highly promising immunomodulatory agent in cancer.

Although anti-CTLA4 improved survival at low dose, it worsened outcome at high dose. It is possible that high doses of anti-CTLA-4 led to excessive lymphocyte activation thereby resulting in additional deaths. Such an effect would be consistent with the adverse effects of anti-CTLA-4 noted in a subgroup of cancer patients who were treated with antibody to CTLA-4. In the study by Hodi and colleagues, 10–15 % of patients had a grade 3 or 4 adverse effect related to the autoimmunity including hypophysitis, thyroiditis, and colitis (3). In 7 of the 676 patients who were treated with anti-CTLA4, death was felt to be directly related to drug therapy. Although these side effects are worrisome, there are several reasons why we believe that this issue will be less likely in patients with sepsis. First, patients with sepsis are usually more immunosuppressed than most cancer patients. Given the reported significant increase in T regulatory cell to effector cell ratio and other immunosuppressive factors present in patients with sepsis (27), we believe that it will be difficult for these patients to develop a potent autoimmune response. In addition, patients with cancer received multiple doses of anti-CTLA4 while patients with sepsis could likely be treated with a single dose. It is also possible that a lower dose of anti-CTLA4 could be used in sepsis versus cancer. Once diagnostic tests are available to differentiate whether the patient is in the hyper- or hypo-inflammatory phase of sepsis, it will likely be possible to safely administer immune-activating therapies such as anti-CTLA-4 in a rationale and life saving manner.

An interesting observation was the ability of anti-CTLA-4 to prevent sepsis-induced apoptosis (Figure 3). Given that uptake of apoptotic cells are potently immunosuppressive, prevention of apoptosis may be one of the mechanisms by which blockade of CTLA-4 improves immune function. CTLA-4 activates protein phosphatase 2A (PP2A) which has an important role in regulation of phophatidylionositol-3 kinase signaling (28). This pathway also has effects on apoptosis of immune effector cells and this may be one of the means by which blockade of CTLA-4 prevents apoptosis of lymphocytes.

In conclusion, anti-CTLA-4 prevents two immunopathologic hallmarks of sepsis, i.e., apoptosis and immunosuppression, and represents a potentially novel therapy for sepsis. Caution will be necessary in its use in sepsis because it does have a potential to worsen outcome at higher doses.

Acknowledgement

This work was supported by NIH grants GM44118, GM55194, and by the Alan A. and Edith L. Wolff Foundation.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Lasaro MO, Ertl HC. Targeting inhibitory pathways in cancer immunotherapy. Curr Opin Immunol. 2010;22:385–390. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2010.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cheever MA. Twelve immunotherapy drugs that could cure cancers. Immunol Rev. 2008;222:357–368. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2008.00604.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hodi FS, O'Day SJ, McDermott DF, Weber RW, Sosman JA, Haanen JB, Gonzalez R, Robert C, Schadendorf D, Hassel JC, Akerley W, van den Eertwegh AJ, Lutzky J, Lorigan P, Vaubel JM, Linette GP, Hogg D, Ottensmeier CH, Lebbe C, Peschel C, Quirt I, Clark JI, Wolchok JD, Weber JS, Tian J, Yellin MJ, Nichol GM, Hoos A, Urba WJ. Improved survival with ipilimumab in patients with metastatic melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:711–723. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1003466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hotchkiss RS, Opal S. Immunotherapy for sepsis--a new approach against an ancient foe. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:87–89. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcibr1004371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Greenwald RJ, Freeman GJ, Sharpe AH. The B7 family revisited. Annu Rev Immunol. 2005;23:515–548. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.23.021704.115611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Linsley PS, Brady W, Urnes M, Grosmaire LS, Damle NK, Ledbetter JA. CTLA-4 is a second receptor for the B cell activation antigen B7. J Exp Med. 1991;174:561–569. doi: 10.1084/jem.174.3.561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Walunas TL, Lenschow DJ, Bakker CY, Linsley PS, Freeman GJ, Green JM, Thompson CB, Bluestone JA. CTLA-4 can function as a negative regulator of T cell activation. Immunity. 1994;1:405–413. doi: 10.1016/1074-7613(94)90071-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Leach DR, Krummel MF, Allison JP. Enhancement of antitumor immunity by CTLA-4 blockade. Science. 1996;271:1734–1736. doi: 10.1126/science.271.5256.1734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Quezada SA, Peggs KS, Curran MA, Allison JP. CTLA4 blockade and GM-CSF combination immunotherapy alters the intratumor balance of effector and regulatory T cells. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:1935–1945. doi: 10.1172/JCI27745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shrikant P, Khoruts A, Mescher MF. CTLA-4 blockade reverses CD8+ T cell tolerance to tumor by a CD4+ T cell- and IL-2-dependent mechanism. Immunity. 1999;11:483–493. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80123-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hotchkiss RS, Karl IE. The pathophysiology and treatment of sepsis. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:138–150. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra021333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Monneret G. How to identify systemic sepsis-induced immunoparalysis. Advances in Sepsis. 2005;4:42–49. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Adib-Conquy M, Cavaillon JM. Compensatory anti-inflammatory response syndrome. Thromb Haemost. 2009;101:36–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Docke WD, Randow F, Syrbe U, Krausch D, Asadullah K, Reinke P, Volk HD, Kox W. Monocyte deactiviation in septic patients: restoration by IFN-gamma treatment. Nat Med. 1997;3:678–681. doi: 10.1038/nm0697-678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ertel W, Kremer J-P, Kenney J, Steckholzer U, Jarrar D, Trentz O, Schildberg FW. Downregulation of proinflammatory cytokine release in whole blood from septic patients. Blood. 1995;85:1341–1347. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sinistro A, Almerighi C, Ciaprini C, Natoli S, Sussarello E, Di Fino S, Calo-Carducci F, Rocchi G, Bergamini A. Downregulation of CD40 ligand response in monocytes from sepsis patients. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2008;15:1851–1858. doi: 10.1128/CVI.00184-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Huang X, Venet F, Wang YL, Lepape A, Yuan Z, Chen Y, Swan R, Kherouf H, Monneret G, Chung CS, Ayala A. PD-1 expression by macrophages plays a pathologic role in altering microbial clearance and the innate inflammatory response to sepsis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:6303–6308. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0809422106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brahmamdam P, Inoue S, Unsinger J, Chang KC, McDunn JE, Hotchkiss RS. Delayed administration of anti-PD-1 antibody reverses immune dysfunction and improves survival duringZ sepsis. J Leukoc Biol. 2010;88:233–240. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0110037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Anderson KM, Czinn SJ, Redline RW, Blanchard TG. Induction of CTLA-4-mediated anergy contributes to persistent colonization in the murine model of gastric Helicobacter pylori infection. J Immunol. 2006;176:5306–5313. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.9.5306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Johanns TM, Ertelt JM, Rowe JH, Way SS. Regulatory T cell suppressive potency dictates the balance between bacterial proliferation and clearance during persistent Salmonella infection. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6 doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1001043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Martins GA, Tadokoro CE, Silva RB, Silva JS, Rizzo LV. CTLA-4 blockage increases resistance to infection with the intracellular protozoan Trypanosoma cruzi. J Immunol. 2004;172:4893–4901. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.8.4893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Graefe SE, Jacobs T, Wachter U, Broker BM, Fleischer B. CTLA-4 regulates the murine immune response to Trypanosoma cruzi infection. Parasite Immunol. 2004;26:19–28. doi: 10.1111/j.0141-9838.2004.00679.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chaudry IH, Wichterman KA, Baue AE. Effect of sepsis on tissue adenine nucleotide levels. Surgery. 1979;85:205–211. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Peck-Palmer OM, Unsinger J, Chang KC, McDonough JS, Perlman H, McDunn JE, Hotchkiss RS. Modulation of the Bcl-2 family blocks sepsis-induced depletion of dendritic cells and macrophages. Shock. 2009;31:359–366. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0b013e31818ba2a2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brahmamdam P, Watanabe E, Unsinger J, Chang KC, Schierding W, Hoekzema AS, Zhou TT, McDonough JS, Holemon H, Heidel JD, Coopersmith CM, McDunn JE, Hotchkiss RS. Targeted delivery of siRNA to cell death proteins in sepsis. Shock. 2009;32:131–139. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0b013e318194bcee. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schwulst SJ, Muenzer JT, Peck-Palmer OM, Chang KC, Davis CG, McDonough JS, Osborne DF, Walton AH, Unsinger J, McDunn JE, Hotchkiss RS. Bim siRNA decreases lymphocyte apoptosis and improves survival in sepsis. Shock. 2008;30:127–134. doi: 10.1097/shk.0b013e318162cf17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Venet F, Chung CS, Kherouf H, Geeraert A, Malcus C, Poitevin F, Bohe J, Lepape A, Ayala A, Monneret G. Increased circulating regulatory T cells (CD4(+)CD25 (+)CD127 (−)) contribute to lymphocyte anergy in septic shock patients. Intensive Care Med. 2009;35:678–686. doi: 10.1007/s00134-008-1337-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Riley JL. PD-1 signaling in primary T cells. Immunol Rev. 2009;229:114–125. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2009.00767.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]