Abstract

Purpose

Few patients 75 years of age and older participate in clinical trials, thus whether adjuvant chemotherapy for stage III colon cancer (CC) benefits this group is unknown.

Methods

A total of 5,489 patients ≥ 75 years of age with resected stage III CC, diagnosed between 2004 and 2007, were selected from four data sets containing demographic, stage, treatment, and survival information. These data sets included SEER-Medicare, a linkage between the New York State Cancer Registry (NYSCR) and its Medicare programs, and prospective cohort studies Cancer Care Outcomes Research and Surveillance Consortium (CanCORS) and the National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Data sets were analyzed in parallel using covariate adjusted and propensity score (PS) matched proportional hazards models to evaluate the effect of treatment on survival. PS trimming was used to mitigate the effects of selection bias.

Results

Use of adjuvant therapy declined with age and comorbidity. Chemotherapy receipt was associated with a survival benefit of comparable magnitude to clinical trials results (SEER-Medicare PS-matched mortality, hazard ratio [HR], 0.60; 95% CI, 0.53 to 0.68). The incremental benefit of oxaliplatin over non–oxaliplatin-containing regimens was also of similar magnitude to clinical trial results (SEER-Medicare, HR, 0.84; 95% CI, 0.69 to 1.04; NYSCR-Medicare, HR, 0.82, 95% CI, 0.51 to 1.33) in two of three examined data sources. However, statistical significance was inconsistent. The beneficial effect of chemotherapy and oxaliplatin did not seem solely attributable to confounding.

Conclusion

The noninvestigational experience suggests patients with stage III CC ≥ 75 years of age may anticipate a survival benefit from adjuvant chemotherapy. Oxaliplatin offers no more than a small incremental benefit. Use of adjuvant chemotherapy after the age of 75 years merits consideration in discussions that weigh individual risks and preferences.

INTRODUCTION

Colorectal cancer is a disease of aging. Of the 141,000 people diagnosed with colorectal cancer in the United States in 2011,1 40% will be 75 years of age or older.2,3 Patients older than 75 years also account for half of colorectal cancer deaths.1 Despite this disproportionate burden, older patients are underrepresented in clinical trials of colorectal cancer chemotherapy. With scarce efficacy data, elderly patients and their physicians lack clear standards to guide treatment decisions.

For patients with stage III colon cancer, adjuvant chemotherapy after curative intent surgical resection improves the chance of cure. Adjuvant treatment options include fluorouracil with modulating leucovorin (FU), the oral FU prodrug capecitabine, or the combination of FU or capecitabine with oxaliplatin. FU significantly improves disease-free survival (DFS) and overall survival (OS) over surgery alone, with relative risk reductions of 30% and 26% respectively.4 The MOSAIC (Multicenter International Study of Oxaliplatin/5-Fluorouracil/Leucovorin in the Adjuvant Treatment of Colon Cancer) trial demonstrated that the addition of oxaliplatin to this FU backbone further improves DFS by 23% and OS by 20%, leading to a 4.2% absolute improvement in OS for the FU/oxaliplatin-treated patients with stage III colon cancer.5,6

However, the two major trials demonstrating the efficacy of adjuvant oxaliplatin enrolled only 25 (< 1%) and 131 (5%) patients ≥ 75 of age each (D.J. Sargent, personal communication, November 2009).5,7 In light of the small number of older patients in these trials, investigators have pooled data from multiple trials to increase the statistical power in the elderly subgroup. An analysis of patients older than 70 years treated with adjuvant FU found no evidence of diminishing effect of chemotherapy on cancer recurrences or deaths with increasing age, but this study predates the oxaliplatin era.8 An analysis of more contemporary trials found that the incremental benefit of oxaliplatin was less for patients older than 70 years than for younger patients.9 Thus the extent to which patients older than 75 years benefit from postsurgical chemotherapy remains a challenge that is frequently encountered in oncology practice. To shed light on actual practice patterns and outcomes, we evaluated the effectiveness of any adjuvant chemotherapy for patients older than 75 years with stage III colon cancer and whether the addition of oxaliplatin provides additional survival benefit.

METHODS

Data Sources

Four data sources were assembled: (1) the SEER program cancer registry linked to Medicare claims (SEER-Medicare), (2) the New York State Cancer Registry (NYSCR) linked to Medicare claims, (3) the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) Outcomes Database, and (4) the Cancer Care Outcomes Research & Surveillance Consortium (CanCORS). The National Cancer Institute's SEER program collects data on incident cancer diagnoses from registries covering 26% of the US population. SEER-Medicare links patients with cancer to their corresponding Medicare claims for investigation of treatment and outcomes.10,11 The NYSCR-Medicare data allow for similar investigation of treatment outcomes for patients diagnosed in New York State. Since 2005, the NCCN Outcomes Database has prospectively abstracted data on incident colorectal cancers from medical records at eight National Cancer Institute–designated Comprehensive Cancer Centers.12,13 CanCORS is a population- and health system–based cohort study of patients diagnosed with colorectal cancer between 2004 and 2007 from four geographical regions, five large health maintenance organizations, and 15 Veterans' Administration hospitals.14,15 In CanCORS, demographics were collected by patient survey. Tumor site, stage, and treatment were ascertained through medical record review.

Case Eligibility

All patients were ≥ 75 years of age at time of diagnosis, had histologically confirmed stage III adenocarcinoma of the colon resected ≤ 90 days from diagnosis, and survived ≥ 30 days after surgery (Fig 1). Exclusions were rectal cancer, prior history of colon cancer, and autopsy diagnoses. Patients in SEER-Medicare and NYSCR-Medicare were excluded if enrolled in a health maintenance organization or not continuously enrolled in both Medicare Parts A and B for 6 months from diagnosis to ensure all claims were available for analysis. Those diagnosed before 2004, the year of oxaliplatin's approval for this indication, were excluded.

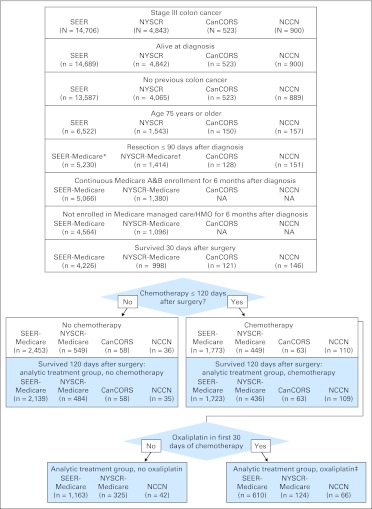

Fig 1.

Cohort assembly CONSORT diagram. (*) SEER cases and Medicare claims were linked at this step. (†) New York State Cancer Registry (NYSCR) cases and Medicare claims were linked at this step. (‡) Cancer Care Outcomes Research and Surveillance Consortium (CanCORS) cases were not included in the oxaliplatin versus nonoxaliplatin comparison because of small numbers of oxaliplatin-treated patients. In National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN), two patients were dropped because the chemotherapy regimen could not be determined. NA, not applicable.

Ascertainment of Treatment

This investigation included two main treatment comparisons: chemotherapy versus no chemotherapy and, for the subset treated with chemotherapy, oxaliplatin-containing versus non–oxaliplatin-containing treatment regimens. For the Medicare cohorts, treatment was ascertained based on the presence of billing codes for chemotherapy, including the presence of specific J codes for oxaliplatin. Medical records were the source of treatment information in NCCN and CanCORS.

The no chemotherapy group included patients with no claim or record for chemotherapy within 120 days of surgery; those with a claim/record within 120 days of surgery comprised the chemotherapy group. This chemotherapy group was divided into an oxaliplatin group—any claim/record of oxaliplatin within 30 days of the first chemotherapy dose—and a nonoxaliplatin group—patients without oxaliplatin claim/record, including those receiving oral, bolus, and infusional FU.16–19 Because of the small number of oxaliplatin-treated patients, chemotherapy regimens were not compared in CanCORS.

Statistical Methods

Covariates in effectiveness data sets.

Variables common to all four data sets included age, race, sex, marital status, year of diagnosis, tumor substage, and tumor grade. Income based on residence zip code or census tract was available for SEER-Medicare, NCCN, and NYSCR; CanCORS contains individual estimates. Comorbidity was measured by the Charlson Comorbidity Index in NCCN, the Deyo modification of the Charlson Comorbidity Index in NYSCR-Medicare, and the Deyo-Klabunde modification in SEER-Medicare.20–22 Comorbidity in CanCORS was measured using the Adult Comorbidity Evaluation–27 index.13,23 Given the presumed key contribution of comorbid conditions to treatment and outcomes in older patients, though measured differently in each sample, comorbidity was retained in all analyses.

OS.

The primary outcome of interest was OS, measured from 30 days after surgery until death from any cause. This was chosen as the anchor date because it could be reliably ascertained and consistently measured for all cohorts. Because the survival measure began 90 days before the chemotherapy exposure window ended, we explored the potential for immortal person-time bias whereby patients dying during the exposure window have a lower chance of receiving treatment, thus worsening the outcome of the no treatment group.24 In the no chemotherapy group, 12% of patients in SEER-Medicare and 13% in NYSCR died within 120 days of surgery compared with only 3% of patients in the chemotherapy group. Thus patients dying within 120 days of surgery were excluded from the survival comparison of chemotherapy versus no chemotherapy to minimize bias. Sensitivity analysis showed that anchoring survival at 120 days instead of 30 days had little effect on outcomes, thus 30 days was retained to better approximate clinical trials survival estimates.

Analysis.

Because of the heterogeneous methods of data ascertainment and measurement across cohorts as well as stipulations in data use agreements, data sets were not combined. Instead, we applied consistent inclusion criteria and covariate specifications across cohorts in parallel. Within each cohort, univariate and multivariate logistic regressions assessed associations between covariates, chemotherapy use, and oxaliplatin receipt. OS of treatment groups were compared descriptively by Kaplan-Meier survival estimates.

Because treatment effect estimates are likely confounded by factors related to treatment selection, we performed a propensity score (PS) matched analysis to compare the effect of treatment on survival among patients of similar risk profiles as assessed by measured, known confounders.25,26 To do so, we generated two PSs: one estimated the likelihood of chemotherapy receipt, and the other estimated the likelihood of oxaliplatin receipt in chemotherapy-treated patients. For each comparison, exposed patients (eg, chemotherapy, oxaliplatin) were matched to patients with the same PS from the unexposed treatment group. Patients for whom there was no match were excluded. In this way, we generated a PS-matched cohort balanced across treatment groups for measured confounders. OS survival was then compared in these PS-matched cohorts. PS matching was not performed with NCCN because of small sample and data use agreements. Instead, a Cox proportional hazards model adjusted for confounding.

To estimate the extent to which unmeasured confounding was responsible for the measured treatment effect, we conducted a sensitivity analysis whereby patients treated contrary to their PS prediction were trimmed from the sample.27 Because patients treated contrary to prediction are most likely to have unmeasured confounders determining their treatment selection (eg, frailty), omitting them increases the validity of the treatment effect estimate.27 If the observed treatment effect estimate is largely due to unmeasured confounding, with trimming the survival hazard ratio (HR) should more closely approach the null. Trimming was conducted in an asymmetric iterative fashion by percentiles at cut points of 1%/99%, 2.5%/97.5%, and 5%/95%.27 After each iteration, PS matching was again performed and a survival HR calculated for the trimmed, matched group.

RESULTS

A total of 5,489 patients ≥ 75 years of age with resected stage III colon cancer were included: 4,226 from SEER-Medicare, 998 from the NYSCR-Medicare, 121 from CanCORS, and 144 from NCCN (Table 1). Because of differences in cohort assembly, there were substantial differences in the distribution of important covariates, such as sex, race, and income, across cohorts.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Elderly Patients With Resected Stage III Colon Cancer

| Characteristic | SEER-Medicare (n = 4,226) |

NYSCR-Medicare (n = 998) |

CanCORS (n = 121) |

NCCN (n = 144) |

|||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No chemo (n = 2,453) |

Chemo (n = 1,773; 42%) |

No Chemo (n = 549) |

Chemo (n = 449; 45%) |

No Chemo (n = 58; 48%) |

Chemoa (n = 63; 52%) |

No Chemo (n = 36; 25%) |

Chemo (n = 108; 75%) |

||||||||||||||||

| FU (n = 1,163; 66%) |

Oxaliplatin (n = 610; 42%) |

FU (n = 325; 72%) |

Oxaliplatin (n = 124; 28%) |

FU (n = 42; 39%) |

Oxaliplatin (n = 66; 61%) |

||||||||||||||||||

| No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | ||

| Age, years | b | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Median | 84 | 80 | 78 | 83 | 80 | 78 | 79 | 80 | 78 | ||||||||||||||

| Range | 75-105 | 75-95 | 75-89 | 75-101 | 75-94 | 75-90 | 75-92 | 75-88 | 75-109 | ||||||||||||||

| 75-79 | 565 | 23 | 530 | 46 | 445 | 73 | 93 | 17 | 120 | 37 | 68 | 55 | c | 31 | 49 | 18 | 50 | 18 | 43 | 51 | 77 | ||

| 80-84 (CanCORS 80-81) | 823 | 34 | 466 | 40 | 152 | 25 | 190 | 35 | 140 | 43 | 41 | 33 | 23 | 40 | 13 | 21 | 18 | 50 | 24 | 57 | 15 | 23 | |

| 85+ (CanCORS ≥ 82) | 1,065 | 43 | 167 | 14 | 13 | 2 | 266 | 48 | 65 | 20 | 15 | 12 | 35 | 60 | 19 | 30 | c | c | c | ||||

| Sex | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Female | 1,631 | 66 | 693 | 60 | 330 | 54 | 361 | 66 | 190 | 58 | 67 | 54 | 31 | 53 | 28 | 44 | 22 | 61 | 16 | 38 | 35 | 53 | |

| Male | 822 | 34 | 470 | 40 | 280 | 46 | 188 | 34 | 135 | 42 | 57 | 46 | 27 | 47 | 35 | 56 | 14 | 39 | 26 | 62 | 31 | 47 | |

| Race | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| White | 2,081 | 85 | 979 | 84 | 524 | 86 | 494 | 90 | 287 | 88 | 117 | 94 | 43 | 74 | 46 | 73 | 30 | 83 | 34 | 81 | 58 | 88 | |

| Black | 211 | 9 | 64 | 6 | 39 | 6 | 42 | 8 | 20 | 6 | d | d | d | d | d | d | |||||||

| Asian | 87 | 4 | 62 | 5 | 27 | 4 | 13 | 2 | 18 | 6 | d | d | d | d | d | d | |||||||

| Other | 74 | 3 | 58 | 5 | 20 | 3 | c | c | 0 | 0 | d | d | d | d | d | ||||||||

| Latino | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Yes | 111 | 5 | 70 | 6 | 35 | 6 | 32 | 6 | 17 | 5 | d | e | — | d | d | d | |||||||

| No | 2,342 | 95 | 1,093 | 94 | 575 | 94 | 517 | 94 | 308 | 95 | > 90f | — | — | 32 | 89 | 37 | 88 | 58 | 88 | ||||

| Unknown | d | d | d | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Charlsong | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| 0 | 1,196 | 49 | 650 | 56 | 381 | 62 | 349 | 64 | 229 | 70 | 93 | 75 | NA | NA | 17 | 47 | 18 | 43 | 34 | 52 | |||

| 1 | 670 | 27 | 319 | 27 | 159 | 26 | 103 | 19 | 54 | 17 | 31 | 25 | 19 | 53 | 24 | 57 | 31 | 48 | |||||

| ≥ 2 | 587 | 24 | 194 | 17 | 70 | 11 | 97 | 18 | 13 | 42 | c | c | c | c | |||||||||

| ACE-27 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| None | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | c | c | NA | NA | NA | ||||||||||||

| Mild | 34 | 59 | 41 | 65 | |||||||||||||||||||

| Moderate | 24 | 41 | 22 | 35 | |||||||||||||||||||

| Severe | c | c | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Marital status | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Married | 865 | 35 | 591 | 51 | 351 | 58 | 154 | 28 | 146 | 45 | 54 | 44 | 24 | 41 | 35 | 56 | NA | NA | NA | ||||

| Single | 191 | 8 | 65 | 6 | 33 | 5 | 77 | 14 | 46 | 14 | 16 | 13 | e | e | |||||||||

| Widow/divorce | 1,302 | 53 | 471 | 40 | 196 | 36 | 318 | 58 | 133 | 41 | 54 | 44 | 33 | 56 | 28 | 44 | |||||||

| Other | 95 | 4 | 36 | 3 | 30 | 5 | c | c | c | c | c | ||||||||||||

| AJCC stage | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| IIIa | 232 | 9 | 119 | 10 | 47 | 8 | 56 | 10 | 40 | 12 | c | c | 13 | 21 | d | c | d | ||||||

| IIIb | 1,499 | 61 | 672 | 58 | 314 | 51 | 326 | 59 | 176 | 54 | 76 | 61 | 43 | 74 | 31 | 49 | 26 | 72 | 27 | 65 | 39 | 59 | |

| IIIc | 722 | 29 | 372 | 32 | 249 | 41 | 167 | 30 | 109 | 34 | 48 | 39 | 15 | 26 | 19 | 30 | d | 15 | 35 | 17 | 26 | ||

| IIINOS | c | c | 0 | 0 | c | c | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | d | ||||||||||||

| Tumor grade | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Well differentiated | 121 | 5 | 51 | 4 | 40 | 7 | 357 | 65 | 189 | 58 | 68 | 55 | d | d | 0 | 0 | d | c | |||||

| Moderately differentiated | 1,491 | 61 | 690 | 59 | 357 | 59 | 192 | 35 | 121 | 37 | 55 | 45 | 38 | 66 | 46 | 73 | 21 | 58 | 32 | 76 | 40 | 61 | |

| Un/poorly differentiated | 790 | 32 | 399 | 34 | 199 | 33 | c | 15 | 5 | c | 16 | 28 | d | 15 | 42 | c | 26 | 39 | |||||

| Unknown | 51 | 2 | 23 | 2 | 14 | 2 | d | d | c | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||||||||

| Median income | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Top quantile | 200,008 | 159,521 | 151,970 | 134,325 | 131,402 | 200,000 | h | — | 87,638 | 99,076 | 111,492 | ||||||||||||

| 3rd quantile | 45,665 | 46,214 | 51,199 | 58,803 | 62,569 | 63,379 | — | — | 54,677 | 64,787 | 67,226 | ||||||||||||

| 2nd quantile | 35,064 | 35,317 | 38,478 | 43,035 | 46,291 | 51,565 | — | — | 41,455 | 47,456 | 48,744 | ||||||||||||

| 1st quantile | 27,195 | 27,526 | 28,892 | 33,990 | 33,573 | 35,425 | — | — | 33,656 | 37,996 | 38,487 | ||||||||||||

| Bottom quantile | 7,344 | 8,544 | 10,076 | 14,896 | 14,271 | 20,582 | — | — | 17,529 | 18,968 | 20,334 | ||||||||||||

| Missing | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Year of diagnosis | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2004 | 624 | 25 | 390 | 34 | 82 | 13 | 190 | 35 | 144 | 44 | 28 | 23 | 58 | 100 | 51 | 81 | — | — | — | ||||

| 2005 | 647 | 26 | 336 | 29 | 165 | 27 | 189 | 34 | 101 | 31 | 38 | 31 | c | 12 | 19 | 16 (2005-2006) | 45 | 16 (2005-2006) | 38 | 24 (2005-2006) | 37 | ||

| 2006 | 591 | 24 | 208 | 18 | 167 | 27 | 170 | 31 | 80 | 25 | 58 | 47 | — | — | c | c | c | ||||||

| 2007 | 591 | 24 | 229 | 20 | 196 | 32 | — | — | — | — | — | 20 (2007-2009) | 55 | 26 (2007-2009) | 62 | 15 | 23 | ||||||

| 2008 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | c | c | 27 (2008-2009) | 40 | |||||||||||

| 2009 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | c | c | c | ||||||||||||

| Time from surgery to first chemo, days | NA | NA | NA | NA | |||||||||||||||||||

| Median | 47 | 47 | 48 | 46 | 43 | 51 | 51 | ||||||||||||||||

| Range | 0-119 | 10-120 | 5-120 | 17-115 | 20-116 | 25-116 | 22-117 | ||||||||||||||||

| F/U time, days | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Median | 740 | 1,109 | 1,053 | 552 | 772 | 601 | 1,260 | 1,260 | 780 | 984 | 823 | ||||||||||||

| Range | 0-2,153 | 17-2,154 | 29-2,133 | 0-1,422 | 30-1,430 | 39-1,397 | 131-1,260 | 147-1,260 | 38-1,930 | 275-1,874 | 100-1,872 | ||||||||||||

Abbreviations: ACE-27, Adult Comorbidity Evaluation–27; AJCC, American Joint Committee on Cancer; CanCORS, Cancer Care Outcomes Research and Surveillance Consortium; CCI, Charlson Comorbidity Index; Chemo, chemotherapy; F/U, follow-up; FU, fluorouracil with modulating leucovorin; NA, not applicable; NCCN, National Comprehensive Cancer Network; NOS, not otherwise specified; NYSCR, New York State Cancer Registry.

Only 10 patients in CanCORS received oxaliplatin; therefore, the chemo group is not subdivided to preserve patient confidentiality and because of the limitation of analysis of such a small sample.

Age was measured categorically in CanCORS, median is not available. Catergories are 75-79, 80-81, ≥ 82.

Collapsed with category above/below because of small numbers to preserve confidentiality.

Eleven or fewer patients; number omitted to preserve confidentiality.

Latino patients in CanCORS are combined with “Other” because of small numbers. Single patients were combined with “Other” because of small numbers.

The majority of oxaliplatin-treated patients in NYSCR-Medicare were non-Latino. The exact number is masked to preserve confidentiality of the Latino patients.

Comorbidity is measured with the CCI in NCCN, the Deyo-Klabunde modification in SEER-Medicare, and the Deyo modification in NYSCR-Medicare. Comorbidity is measured by the ACE-27 in CanCORS.

Income was measured categorically in CanCORS: > $60,000, $40,000-60,000, $20,000-40,000; < $20,000.

Three hundred sixty-four (9%) patients in SEER-Medicare and 78 patients (8%) in NYSCR-Medicare died within 120 days of colon resection. These patients who died within 120 days of surgery were substantially older than the surviving patients. Only 50 patients in SEER-Medicare and 13 patients in NYSCR-Medicare received any chemotherapy before dying 120 days after surgery, which is 3% of chemotherapy-treated patients in each cohort. Only one NCCN and no CanCORS chemotherapy-treated patients died within 120 days of surgery.

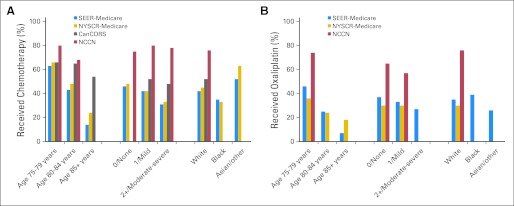

The use of any chemotherapy after resection of stage III cancer differed across cohorts: 42% in SEER-Medicare, 45% in NYSCR-Medicare, 52% in CanCORS, and 75% in NCCN. Among those receiving chemotherapy, a smaller proportion of patients received oxaliplatin as a component of their adjuvant therapy in SEER-Medicare (42%), and NYSCR-Medicare (28%), than at NCCN centers (61%). As expected, the use of both any chemotherapy and oxaliplatin-containing regimens dropped off quickly with advancing age. In multivariate models, age was the factor most strongly associated with both chemotherapy and oxaliplatin receipt (Fig 2; Appendix Tables A3 and A4, online only). Compared with 63% of patients 75 to 79 years of age, only 43% of patients 80 to 84 years of age (odds ratio [OR], 0.44; 95% CI, 0.38 to 0.51) and 14% of patients 85 years of age and older (OR, 0.10; 95% CI, 0.08 to 0.12) in SEER-Medicare received postoperative adjuvant chemotherapy. Of patients treated with chemotherapy, 46% of patients 75 to 79 years of age compared with 25% of patients 80 to 84 years of age (OR, 0.37; 95% CI, 0.29 to 0.46) and 7% of patients 85 years of age and older (OR, 0.08; 95% CI, 0.05 to 0.15) in SEER-Medicare received oxaliplatin. Black elderly patients seemed to be less likely to receive chemotherapy, and Asian patients seemed to be more likely to receive chemotherapy. Small sample sizes, however, limit interpretation about care patterns in these subgroups.

Fig 2.

Percentage of elderly patients with stage III colon cancer treated with chemotherapy. The percentage of patients treated with chemotherapy (A) or oxaliplatin (B) is shown broken down by strata of clinically relevant covariates. Bars representing 11 or fewer patients were omitted to preserve patient confidentiality. Comorbidity is measured with the Charlson Comorbidity Index in National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN), the Deyo-Klabunde modification in SEER-Medicare, the Deyo modification in New York State Cancer Registry (NYSCR) –Medicare, and the Adult Comorbidity Evaluation–27 in Cancer Care Outcomes Research and Surveillance Consortium (CanCORS).

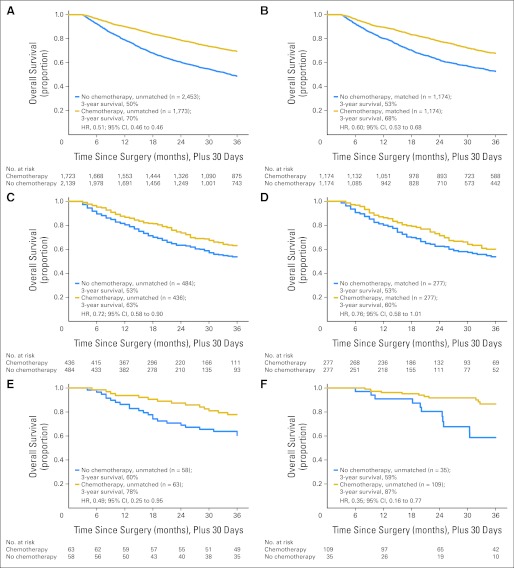

Survival of chemotherapy-treated patients was substantially better than survival of patients not receiving chemotherapy after resection of stage III colon cancer (Table 2; Fig 3). Chemotherapy use was associated with significantly lower mortality in the PS-matched SEER-Medicare cohort (HR, 0.60; 95% CI, 0.53 to 0.68), with a comparable effect in the PS-matched NYSCR-Medicare (HR, 0.76; 95% CI, 0.58 to 1.01) and CanCORS (HR, 0.48; 95% CI, 0.19 to 1.21) cohorts. The Cox proportional hazards–adjusted NCCN analysis also showed a reduction in mortality in chemotherapy-treated patients (HR, 0.42; 95% CI, 0.17 to 1.03). Sensitivity analysis showed no evidence of decreasing treatment effect with PS trimming, suggesting that the observed reduction in mortality stemmed from treatment and not simply from unmeasured confounding.27

Table 2.

Benefit of Adjuvant Chemotherapy Among Elderly Patients With Stage III Colon Cancer

| Patient Group and Survival | Chemotherapy v No Chemotherapy |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SEER-Medicare |

NYSCR-Medicare |

CanCORS |

NCCN |

|||||

| No Chemotherapy | Chemotherapy | No Chemotherapy | Chemotherapy | No Chemotherapy | Chemotherapy | No Chemotherapy | Chemotherapy | |

| Entire cohort | 2,453 | 1,773 | 549 | 449 | 58 | 63 | 36 | 110 |

| Restricted to patients surviving 120 days from surgery | 2,139 | 1,723 | 484 | 436 | 58 (100%) | 63 (100%) | 35 (97%) | 109 (99%) |

| PS-matched cohort | 1,174 | 1,174 | 277 | 277 | 33 | 33 | NA | NA |

| 3-year OS, unmatched cohort (120-day survivors only), % | 50 | 70 | 53 | 63 | 60 | 78 | 59 | 87 |

| 3-year OS, PS-matched cohort (120-day survivors only), % | 53 | 68 | 53 | 60 | 50 | 71 | NA | NA |

| Crude mortality unmatched | ||||||||

| HR | 1 | 0.51 | 1 | 0.72 | 1 | 0.49 | 1 | 0.35 |

| 95% CI | 0.46 to 0.56 | 0.58 to 0.90 | 0.25 to 0.95 | 0.16 to 0.77 | ||||

| PS matched mortality | * | |||||||

| HR | 1 | 0.60 | 1 | 0.76 | 1 | 0.48 | 1 | 0.42 |

| 95% CI | 0.53 to 0.68 | 0.58 to 1.01 | 0.19 to 1.21 | 0.17 to 1.03 | ||||

| Trimmed, PS matched mortality | NA | NA | ||||||

| HR | 1 | 0.62 | 1 | 0.72 | 1 | 0.31 | ||

| 95% CI | 0.54 to 0.71 | 0.53 to 0.97 | 0.10 to 0.96 | |||||

NOTE. Three-year OS and HR with 95% CI from an unadjusted Cox proportional hazards model and a PS-matched and trimmed analysis are shown according to the type of postoperative therapy delivered in patients surviving 120 days from surgical resection.

Abbreviations: CanCORS, Cancer Care Outcomes Research and Surveillance Consortium; HR, hazard ratio; NA, not applicable; NCCN, National Comprehensive Cancer Network; NYSCR, New York State Cancer Registry; OS, overall survival; PS, propensity score.

The PS analysis could not be performed in NCCN because of small sample size and data use agreements. An adjusted Cox proportional HR is shown for NCCN including age, sex, ethnicity, race, comorbidity, tumor substage, tumor grade, and income.

Fig 3.

Unadjusted and propensity score–matched Kaplan-Meier survival comparisons of chemotherapy versus no chemotherapy in elderly patients with stage III colon cancer surviving 120 days from surgery. (A) SEER-Medicare unmatched; (B) SEER-Medicare matched; (C) New York State Cancer Registry (NYSCR) –Medicare unmatched; (D) NYSCR-Medicare matched; (E) Cancer Care Outcomes Research and Surveillance Consortium unmatched; (F) National Comprehensive Cancer Network unmatched. HR, hazard ratio.

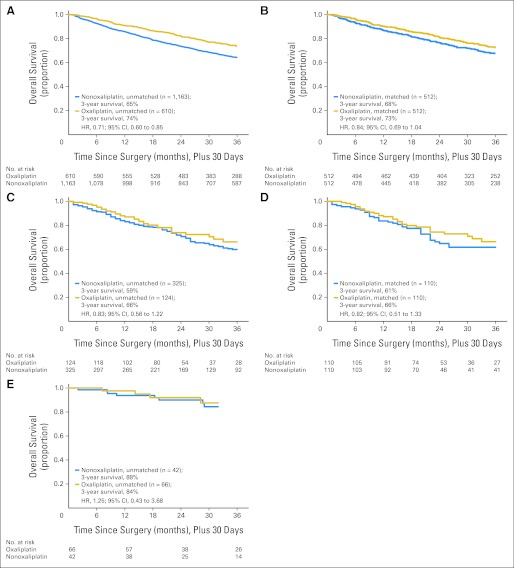

Oxaliplatin use was associated with a trend toward lower mortality among chemotherapy-treated elderly patients in SEER-Medicare (PS-matched HR, 0.84; 95% CI, 0.69 to 01.04) and in NYSCR-Medicare (PS-matched HR, 0.82; 95% CI, 0.51 to 1.33), both corresponding to a 5% absolute improvement in survival at 3 years in the PS-matched cohorts (Table 3; Fig 4). In sensitivity analysis, the effect of oxaliplatin was slightly attenuated by PS trimming in SEER-Medicare with a trimmed HR of 0.87 compared with 0.84, and in NYSCR with a trimmed HR of 0.88 compared with 0.82. Among the 108 chemotherapy-treated patients with age ≥ 75 years in NCCN, there was no apparent benefit associated with oxaliplatin receipt, with exceptionally high 3-year survival of 88% in non–oxaliplatin-treated and 84% in oxaliplatin-treated patients.

Table 3.

Benefit of Adjuvant Oxaliplatin Among Elderly Patients With Stage III Colon Cancer

| Patient Group and Survival | Oxaliplatin v Nonoxaliplatin Adjuvant Chemotherapy |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SEER-Medicare |

NYSCR-Medicare |

NCCN*

|

||||

| Nonoxaliplatin (n = 1,163) | Oxaliplatin (n = 610) | Nonoxaliplatin (n = 325) | Oxaliplatin (n = 124) | Nonoxaliplatin (n = 42) | Oxaliplatin (n = 66) | |

| PS matched | 512 | 512 | 110 | 110 | NA | NA |

| 3-year OS, unmatched cohort, % | 65 | 74 | 59 | 66 | 88 | 84 |

| 3-year OS, PS-matched cohort, % | 68 | 73 | 61 | 66 | NA | NA |

| Crude mortality unmatched | ||||||

| HR | 1 | 0.71 | 1 | 0.83 | 1 | 1.25 |

| 95% CI | 0.60 to 0.85 | 0.56 to 1.22 | 0.43 to 3.68 | |||

| PS matched mortality | * | |||||

| HR | 1 | 0.84 | 1 | 0.82 | 1 | 1.84 |

| 95% CI | 0.69 to 1.04 | 0.51 to 1.33 | 0.48 to 7.05 | |||

| Trimmed, PS matched mortality | NA | NA | ||||

| HR | 1 | 0.87 | 1 | 0.88 | ||

| 95% CI | 0.69 to 1.10 | 0.51 to 1.53 | ||||

NOTE. Three-year OS and HR with 95% CI from an unadjusted Cox proportional hazards model and a PS-matched and trimmed analysis are shown according to the type of postoperative chemotherapy delivered.

Abbreviations: HR, hazard ratio; NA, not applicable; NCCN, National Comprehensive Cancer Network; NYSCR, New York State Cancer Registry; OS, overall survival; PS, propensity score.

The PS analysis could not be performed in NCCN because of small sample size and data use agreements. An adjusted Cox proportional HR is shown for NCCN including age, sex, ethnicity, race, comorbidity, tumor substage, tumor grade, and income.

Fig 4.

Unadjusted and propensity score–matched Kaplan-Meier survival comparison of oxaliplatin and nonoxaliplatin adjuvant chemotherapy in elderly patients with stage III colon cancer. (A) SEER-Medicare unmatched; (B) SEER-Medicare matched; (C) New York State Cancer Registry (NYSCR) –Medicare unmatched; (D) NYSCR-Medicare matched; (E) National Comprehensive Cancer Network unmatched. HR, hazard ratio.

DISCUSSION

People ≥ 75 years of age comprise 40% of the colorectal cancer population.3 Although oxaliplatin increases cure rates for resectable stage III cancer in clinical trials, only 5% of patients enrolled to National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project Trial C07 and fewer than 1% of MOSAIC participants were 75 years of age or older, so the benefit demonstrated by those trials has not been established in the older population. Perhaps as a result of the lack of data in elderly patients, chemotherapy use decreases rapidly with age.15,28 Facing this gap in the clinical trials evidence, we sought to examine the use and comparative effectiveness of adjuvant chemotherapy, and more specifically adjuvant oxaliplatin, in patients 75 years of age and older with stage III colon cancer.

We found that among patients 75 years of age and older surviving 120 days from resection, those treated with adjuvant chemotherapy had a markedly lower risk of death than those who did not. Using effectiveness cohorts reflecting heterogeneous patient populations, the survival advantage associated with adjuvant chemotherapy was comparable to that demonstrated in clinical trials. In fact, the survival advantage was more substantial than has previously been measured in pooled trials data, where adjuvant FU resulted in a 24% reduction in the risk of death.8 Two SEER-Medicare analyses of patients treated for stage III colon cancer in the mid-1990s suggested similar treatment effect sizes (27% and 35% relative risk reductions).29,30 That we found greater association between adjuvant treatment and survival with the inclusion of more recent data may be attributable to the fact that 34% of patients received oxaliplatin. In sensitivity analysis, excluding oxaliplatin-treated patients decreased 3-year survival from 70% to 67% in SEER-Medicare, although this had little effect on the survival HR. If over time, given the emphasis on adjuvant treatment for stage III colon cancer as a quality metric, clinicians have become more comfortable treating older patients with adjuvant therapy, we would anticipate that patients in the no chemotherapy group would become more frail over time. The association between adjuvant treatment and survival could be increasing if such selection bias is operational. This bias likely underlies the large effect of chemotherapy measured in NCCN, where patients were more the most likely to get both chemotherapy and oxaliplatin. Although we used available methods to mitigate such selection, including PS-trimmed sensitivity analysis,27 no method can overcome all such bias in observational data.

The incremental decrease in mortality seen with the addition of oxaliplatin in elderly patients in the community was of comparable size as seen in the MOSAIC and the XELOX in Adjuvant Colon Cancer Treatment (XELOXA) trials, which reported 20% and 13% relative mortality reductions from oxaliplatin, respectively.6,31 In our effectiveness cohorts, relatively small sample sizes limited our ability to evaluate the association between oxaliplatin-containing adjuvant therapy and survival. With the oxaliplatin results considered in parallel, the consistency of the point estimates in the two Medicare cohorts is reassuring. However, with the modest attenuation of oxaliplatin effect in the PS-trimmed sensitivity analysis and the lack of benefit at the NCCN centers, the incremental survival associated with oxaliplatin in this oldest group of treated colon cancer patients seems to be very modest.

Reports of the effect of FU/oxaliplatin combination chemotherapy in patients older than 70 years in clinical trials do not clearly support its benefit over FU. In an analysis of infusional fluorouracil, leucovorin, and oxaliplatin using pooled data from three trials of metastatic colon cancer and one adjuvant trial (MOSIAC), improvements in progression-free survival, disease-free survival (DFS), and OS were similar among older patients compared with younger ones.32 However, the subgroup analysis of patients ≥ 65 years of age in MOSAIC found no survival benefit from oxaliplatin.6 In the XELOXA trial, oxaliplatin's effect on DFS in patients older than 70 years was less robust than in younger patients: DFS HR in patients younger than 70 years, 0.79; 95% CI, 0.66 to 0.94; DFS HR in patients ≥ age 70 years, 0.87; 95% CI, 0.63 to 1.18.33 No DFS or OS benefit was gained in National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project Trial C07 by adding oxaliplatin in patients older than 70 years.34 In addition, in a recent analysis of trials in which novel adjuvant chemotherapies (capecitabine, FU/irinotecan, and FU/oxaliplatin) were compared with an FU control, patients older than 70 years did not benefit from any newer regimen, even when younger patients did. In the case of oxaliplatin-based therapies, there was no survival benefit from oxaliplatin in patients older than 70 years (OS HR, 1.13; 95% CI, 0.96 to 1.32; DFS HR, 1.11; 95% CI, 0.97 to 1.28).9

It seems implausible that oxaliplatin is truly more effective in patients older than 75 years in the community than in patients older than 70 years in randomized trials. Therefore, although the general consistency of findings, including the PS-trimmed models, strengthens our confidence that both chemotherapy in general and oxaliplatin in particular improves outcomes of elderly patients with colon cancer, it seems likely that despite attempts to control for unmeasured confounding, the inherent differences between FU and oxaliplatin patients were not fully accounted for in our analyses. Ideally, clinical trials would recruit subjects whose characteristics mirror those of the affected population thereby strengthening our certainty with regard to the utility of oxaliplatin in the oldest patients with colon cancer. However, given that drug development studies must ask “How well can this treatment work?” trial populations will likely continue to under-represent the elderly. As such, efforts to examine effectiveness by leveraging best available data sources and most careful analytic techniques remain a priority.

This study suggests that patients older than 75 years of age with surgically resected colon cancer may experience a survival benefit from chemotherapy comparable to that previously demonstrated by younger populations in randomized and observational studies.4–6,35 From the perspective of a practicing clinician, these results suggest that consideration of adjuvant systemic therapy is absolutely warranted for patients older than 75 years. Because quality of life could not be measured in this analysis, how adjuvant therapy affects the quality of life of older patients with cancer remains a critical, unanswered question. Clearly, treatment decisions need to be made in the context of individual risk profiles and preferences, but the survival estimates from this work provide benchmarks for consideration and may inform discussions about prognosis. Future research examining additional or larger cohorts may further qualify this study's findings, for example, as they may be modulated by specific patient comorbidities, or as they pertain to a decision to use oxaliplatin versus alternative systemic therapy. In the meantime, this study helps fill the knowledge gap left by clinical trials and inform a prevailing bias away from adjuvant therapy among the oldest patients with colon cancer. The relative consistency of study findings suggests that patients of this age group and their physicians should consider adjuvant chemotherapy as a viable treatment option.

Acknowledgment

Comparative effectiveness research using multiple data sets requires the cooperation of a large number of investigators from different groups. This project could not have been possible without the generosity of multiple teams of investigators who agreed to share their data and who were willing to submit their data for scrutiny and comparison with other sources—without stipulation regarding how the data would be presented. Without the willingness to share data and provide assistance regarding the nuances of each data source, this study could not have been accomplished. We thank the following investigative teams for their critical contributions and highlight specific individuals within those teams: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality DEcIDE Cancer Consortium; Brigham and Women's Hospital/Dana-Farber members Li Ling, Kun Chen, and Jennifer Wind; University of North Carolina members Richard Goldberg, Joseph Galanko, Anne-Marie Meyer, Janet Freburger, Alice Fortune-Greeley, Sara Wobker, and Anne Jackman; the Cancer Care Outcomes Research and Surveillance Consortium (CanCORS); the entire leadership of the CanCORS consortium; the statistical coordinating center and the publications committee reviewers; the National Comprehensive Cancer Network; the Colorectal Cancer Outcomes Database Principal Investigators; statistical analyst Anna Ter Veer and project manager Dana Milne; New York State Cancer Registry (NYSCR) –Medicare and Medicaid; investigators from the NYSCR and New York State Medicaid Program including Patrick Roohan, Francis Boscoe, and Amber Sinclair; SEER-Medicare linked data. This study used the linked SEER-Medicare database. This resource has been made available to the research community through collaborative efforts of the National Cancer Institute (NCI) and Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS). We acknowledge the efforts of the Applied Research Program, NCI; the Office of Research, Development and Information, CMS; Information Management Services; and the SEER Program tumor registries in the creation of the SEER-Medicare database. Contributions from investigators and research staff too numerous to name but without whom this work could not have been accomplished are also recognized.

Appendix

Table A1.

Characteristics of PS-Matched Elderly Patients With Stage III Colon Cancer Who Survived 120 Days From Surgery

| Characteristic | SEER-Medicare |

NYSCR-Medicare |

CanCORS |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No Chemotherapy |

Any Chemotherapy |

No Chemotherapy |

Any Chemotherapy |

No Chemotherapy |

Any Chemotherapy |

|||||||

| No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | |

| Entire cohort | 2,453 | 1,773 | 549 | 449 | 58 | 63 | ||||||

| Restricted to patients surviving 120 days from surgery | 2,139 | 1,723 | 484 | 436 | 58 | 100 | 63 | 100 | ||||

| PS-matched cohort | 1,174 | 1,174 | 277 | 277 | 33 | 33 | ||||||

| Age, years* | ||||||||||||

| 75-79 | 477 | 41 | 483 | 41 | 76 | 27 | 71 | 26 | † | † | ||

| 80-84 (CanCORS 80-81) | 533 | 45 | 524 | 45 | 132 | 48 | 130 | 47 | 21 | 64 | 19 | 56 |

| 85+ (CanCORS ≥ 82) | 164 | 14 | 167 | 14 | 69 | 25 | 76 | 27 | 12 | 36 | 14 | 42 |

| Sex | ||||||||||||

| Female | 731 | 62 | 761 | 65 | 166 | 60 | 172 | 62 | 13 | 39 | 13 | 39 |

| Male | 443 | 38 | 413 | 35 | 111 | 40 | 105 | 38 | 20 | 61 | 20 | 61 |

| Race | ||||||||||||

| White | 997 | 85 | 1,008 | 86 | 256 | 92 | 251 | 91 | 23 | 70 | 25 | 76 |

| Black | 84 | 7 | 81 | 7 | 21 | 8 | 26 | 9 | ‡ | ‡ | ||

| Asian/other | 93 | 8 | 85 | 7 | † | † | ‡ | ‡ | ||||

| Latino | ||||||||||||

| Yes | 62 | 5 | 57 | 5 | 16 | 6 | 17 | 6 | § | § | ||

| No | 1,112 | 95 | 1,117 | 95 | 261 | 94 | 260 | 94 | — | — | ||

| Dual eligible | ||||||||||||

| Medicare only | — | — | 201 | 73 | 205 | 74 | — | — | ||||

| Medicare + Medicaid | — | — | 76 | 27 | 72 | 26 | — | — | ||||

| Charlson/ACE-27 | ||||||||||||

| 0/none | 647 | 55 | 673 | 57 | 191 | 69 | 192 | 69 | † | † | ||

| 1/mild | 316 | 27 | 300 | 26 | 42 | 15 | 42 | 15 | 20 | 61 | 123 | 70 |

| ≥ 2/moderate-severe | 211 | 18 | 201 | 17 | 44 | 16 | 43 | 16 | 13 | 39 | ‡ | |

| Specific comorbidities∥ | ||||||||||||

| Myocardial infarct | 110 | 9 | 105 | 9 | 18 | 6 | 20 | 7 | — | — | ||

| Congestive heart failure | 99 | 8 | 97 | 8 | 17 | 6 | ‡ | |||||

| Cerebrovascular disease | 69 | 6 | 80 | 7 | ‡ | ‡ | ||||||

| Chronic pulmonary disease | 142 | 12 | 132 | 11 | 26 | 9 | 14 | 5 | ||||

| Diabetes | 247 | 21 | 240 | 20 | 18 | 6 | 12 | 4 | ||||

| Marital status | ||||||||||||

| Married | 521 | 44 | 510 | 43 | 94 | 34 | 106 | 38 | 17 | 52 | 17 | 52 |

| Single | 78 | 7 | 79 | 7 | 40 | 14 | 42 | 15 | § | § | ||

| Widowed/divorced | 529 | 45 | 540 | 46 | 143 | 52 | 129 | 47 | 16 | 48 | 16 | 48 |

| Other | 46 | 4 | 45 | 4 | ‡ | ‡ | ‡ | ‡ | ||||

| AJCC stage | ||||||||||||

| IIIa | 124 | 11 | 119 | 10 | 32 | 12 | 34 | 12 | ‡ | ‡ | ||

| IIIb | 712 | 61 | 695 | 59 | 157 | 57 | 167 | 60 | 14 | 42 | 15 | 46 |

| IIIc | 338 | 29 | 360 | 31 | 88 | 32 | 76 | 27 | ‡ | ‡ | ||

| Tumor grade | ||||||||||||

| Well differentiated | 65 | 6 | 57 | 5 | 20 | 7 | 13 | 5 | ‡ | ‡ | ||

| Moderately differentiated | 711 | 61 | 713 | 61 | 162 | 58 | 164 | 59 | 22 | 67 | 24 | 73 |

| Un/poorly differentiated | 373 | 32 | 383 | 33 | 95 | 34 | 100 | 37 | ‡ | ‡ | ||

| Unknown | 25 | 2 | 21 | 2 | ‡ | ‡ | ‡ | ‡ | ||||

| Median income | ||||||||||||

| Top quantile | 281 | 24 | 283 | 24 | 43 | 16 | 58 | 21 | — | — | ||

| 3rd quantile | 288 | 25 | 298 | 25 | 64 | 23 | 55 | 20 | — | — | ||

| 2nd quantile | 293 | 25 | 296 | 25 | 90 | 32 | 91 | 33 | — | — | ||

| 1st quantile | 312 | 27 | 297 | 25 | 80 | 29 | 73 | 26 | — | — | ||

| Year of diagnosis | ||||||||||||

| 2004 | 293 | 25 | 300 | 26 | 96 | 35 | 101 | 36 | 33 | 100 | 33 | 100 |

| 2005 | 312 | 27 | 331 | 28 | 89 | 32 | 92 | 33 | ‡ | ‡ | ||

| 2006 | 273 | 23 | 267 | 23 | 92 | 33 | 84 | 30 | — | — | ||

| 2007 | 296 | 25 | 276 | 24 | — | — | — | — | ||||

NOTE. PS matching was not performed in National Comprehensive Cancer Network because of small number of untreated patients.

Abbreviations: ACE-27, Adult Comorbidity Evaluation–27; AJCC, American Joint Committee on Cancer; CanCORS, Cancer Care Outcomes Research and Surveillance Consortium; NYSCR, New York State Cancer Registry; PS, propensity score.

Age categories were predefined in CanCORS; continuous age is not available.

Collapsed with category above/below because of small numbers to preserve confidentiality.

For 11 or fewer patients, number omitted to preserve confidentiality.

Latino patients in CanCORS are combined with “Other” because of small numbers. Single patients were combined with “Other” because of small numbers.

All comorbidities that comprise the modified Charlson indices were used to generate the PS. Shown are comorbidities affecting 5% or more of any cohort.

Table A2.

Characteristics of PS-Matched Elderly Patients With Stage III Colon Cancer Treated With Chemotherapy

| Characteristic | SEER-Medicare |

NYSCR-Medicare |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nonoxaliplatin (n = 1,163) PS Matched (n = 512) |

Oxaliplatin (n = 610) PS Matched (n = 512) |

Nonoxaliplatin (n = 325) PS Matched (n = 110) |

Oxaliplatin (n = 124) PS Matched (n = 110) |

|||||

| No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | |

| Age, years | ||||||||

| 75-79 | 337 | 66 | 348 | 68 | 53 | 48 | 56 | 51 |

| 80-84 | 162 | 32 | 151 | 29 | 43 | 39 | 40 | 36 |

| 85+ | 13 | 3 | 13 | 3 | 14 | 13 | 14 | 13 |

| Sex | ||||||||

| Female | 285 | 56 | 285 | 56 | 58 | 53 | 60 | 55 |

| Male | 227 | 44 | 227 | 44 | 52 | 47 | 50 | 45 |

| Race | ||||||||

| White | 441 | 86 | 436 | 85 | 101 | 92 | 103 | 94 |

| Black | 27 | 5 | 31 | 6 | * | * | ||

| Asian/other | 44 | 9 | 45 | 9 | * | * | ||

| Latino | ||||||||

| Yes | 27 | 5 | 27 | 5 | * | * | ||

| No | 485 | 95 | 485 | 95 | >90† | >90† | ||

| Dual eligible | ||||||||

| Medicare only | — | — | 92 | 84 | 92 | 84 | ||

| Medicare + Medicaid | — | — | 18 | 16 | 18 | 16 | ||

| Charlson/ACE-27 | ||||||||

| 0/none | 312 | 61 | 323 | 63 | 79 | 72 | 80 | 73 |

| 1/mild | 130 | 25 | 126 | 25 | 31 | 28 | 30 | 27 |

| ≥ 2/moderate | 70 | 14 | 63 | 12 | ‡ | ‡ | ||

| Comorbidities§ | ||||||||

| Myocardial infarct | 45 | 9 | 48 | 9 | * | * | ||

| Cerebrovascular disease | 23 | 4 | 25 | 5 | 0 | * | ||

| Chronic pulmonary disease | 47 | 9 | 44 | 9 | * | * | ||

| Diabetes | 99 | 19 | 97 | 19 | * | * | ||

| Marital status | ||||||||

| Married | 293 | 57 | 292 | 57 | 44 | 40 | 53 | 48 |

| Single | 24 | 5 | 29 | 6 | 12 | 11 | 12 | 11 |

| Widowed/divorced | 172 | 34 | 172 | 34 | 54 | 49 | 45 | 41 |

| Other | 23 | 4 | 19 | 4 | ‡ | ‡ | ||

| AJCC stage | ||||||||

| IIIa | 37 | 7 | 45 | 9 | ‡ | ‡ | ||

| IIIb | 282 | 55 | 277 | 54 | 76 | 69 | 68 | 62 |

| IIIc | 193 | 38 | 190 | 37 | 34 | 31 | 42 | 38 |

| Tumor grade | ||||||||

| Well differentiated | 20 | 4 | 30 | 6 | ‡ | ‡ | ||

| Moderately differentiated | 307 | 60 | 301 | 59 | 64 | 59 | 60 | 55 |

| Un/poorly differentiated | 185 | 36 | 169 | 33 | 46 | 41 | 50 | 46 |

| Unknown | ‡ | 12 | 2 | ‡ | ‡ | |||

| Median income | ||||||||

| Top quantile | 155 | 30 | 152 | 30 | 24 | 22 | 26 | 24 |

| 3rd quantile | 127 | 25 | 129 | 25 | 35 | 32 | 33 | 30 |

| 2nd quantile | 115 | 22 | 117 | 23 | 26 | 24 | 26 | 24 |

| 1st quantile | 115 | 22 | 114 | 22 | 25 | 23 | 25 | 23 |

| Year of diagnosis | ||||||||

| 2004 | 73 | 14 | 82 | 16 | 30 | 27 | 28 | 25 |

| 2005 | 164 | 32 | 160 | 31 | 40 | 36 | 37 | 34 |

| 2006 | 132 | 26 | 121 | 24 | 40 | 36 | 45 | 41 |

| 2007 | 143 | 26 | 149 | 29 | — | — | ||

NOTE. PS matching was not performed in National Comprehensive Cancer Network and Cancer Care Outcomes Research and Surveillance Consortium because of small number of patients.

Abbreviations: ACE-27, Adult Comorbidity Evaluation–27; AJCC, American Joint Committee on Cancer; NYSCR, New York State Cancer Registry; PS, propensity score.

For 11 or fewer patients, number omitted to preserve confidentiality.

All comorbidities that comprise the modified Charlson indices were used to generate the PS. Shown are comorbidities affecting 5% or more of any cohort.

The majority of oxaliplatin-treated patients in NYSCR-Medicare were non-Latino. The exact number is masked to preserve confidentiality of the Latino patients.

Collapsed with category above/below because of small numbers to preserve confidentiality.

Table A3.

Likelihood of Chemotherapy Receipt Among Elderly Stage III Colon Cancer

| Characteristic | SEER-Medicare |

NYSCR-Medicare |

CanCORS |

NCCN |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adjusted* OR | 95% CI | Adjusted OR | 95% CI | Adjusted OR | 95% CI | Adjusted OR | 95% CI | |

| Received chemotherapy | ||||||||

| No. | 1773 | 449 | 63 | 110 | ||||

| % | 42 | 45 | 52 | 75 | ||||

| Age, years† | ||||||||

| 75-79 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| 80-84 (CanCORS 80-81) | 0.44 | 0.38 to 0.51 | 0.50 | 0.36 to 0.69 | 1.45 | 0.41 to 5.17 | 0.37 | 0.14 to 1.02 |

| 85+ (CanCORS ≥ 82) | 0.10 | 0.08 to 0.12 | 0.15 | 0.10 to 0.22 | 0.20 | 0.07 to 0.57 | 0.33 | 0.07 to 1.61 |

| Sex | ||||||||

| Female | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Male | 1.12 | 0.96 to 1.31 | 1.29 | 0.98 to 1.71 | 0.91 | 0.30 to 2.75 | 1.20 | 0.48 to 3.02 |

| Comorbidity‡ | ||||||||

| 0/None | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| 1/Mild | 0.78 | 0.66 to 0.91 | 0.82 | 0.57 to 1.18 | 0.34 | 0.07 to 1.71 | 1.82 | 0.64 to 5.17 |

| 2+/Moderate | 0.47 | 0.39 to 0.57 | 0.59 | 0.39 to 0.88 | 0.46 | 0.0.08 to 2.58 | 1.60 | 0.45 to 5.69 |

| Severe | 0.34 | 0.07 to 1.71 | ||||||

| Race | ||||||||

| White | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Black | 0.71 | 0.54 to 0.94 | 0.60 | 0.33 to 1.05 | 0.13 | 0.01 to 2.00 | 0.62 | 0.13 to 2.93 |

| Asian/other | 1.39 | 1.04 to 1.88 | 1.46 | 0.69 to 3.21 | 1.53 | 0.48 to 4.84 | 1.88 | 0.14 to 25.7 |

| Income | ||||||||

| Top quartile | 1.23 | 1.01 to 1.50 | 1.47 | 0.98 to 2.22 | * | 16.0 | 2.40 to 107.1 | |

| 3rd quartile | 1.08 | 0.88 to 1.31 | 0.94 | 0.64 to 1.39 | — | 2.45 | 0.62 to 9.58 | |

| 2rd quartile | 1.04 | 0.86 to 1.27 | 0.83 | 0.58 to 1.19 | — | 3.00 | 0.88 to 10.24 | |

| Bottom quartile | 1 | 1 | — | 1 | ||||

| Diagnosis year | ||||||||

| 2004 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||

| 2005 | 0.96 | 0.80 to 1.16 | 0.78 | 0.56 to 1.08 | 4.77 | 1.07 to 21.20 | 1 | |

| 2006 | 0.82 | 0.67 to 1.00 | 0.92 | 0.66 to 1.28 | — | 1.28 | 0.28 to 5.92 | |

| 2007 | 0.96 | 0.79 to 1.17 | — | — | 1.38 | 0.28 to 6.81 | ||

| 2008 | — | — | — | 3.22 | 0.56 to 18.5 | |||

| 2009 | — | — | 0.94 | 0.17 to 5.34 | ||||

Abbreviations: CanCORS, Cancer Care Outcomes Research and Surveillance Consortium; NCCN, National Comprehensive Cancer Network; NYSCR, New York State Cancer Registry; OR, odds ratio.

ORs are adjusted for all variables with the exception of CanCORS, for which income was omitted because of small sample size.

Age categories were predefined in CanCORS; continuous age is not available. Categories are 75 to 79, 80 to 81, and ≥ 82 years.

Comorbidity is measured with the Charlson Comorbidity Index in NCCN, the Deyo-Klabunde modification in SEER-Medicare, and the Deyo modification in NYSCR-Medicare. Comorbidity is measured by the Adult Comorbidity Evaluation–27 in CanCORS.

Table A4.

Likelihood of Oxaliplatin Receipt Among Elderly Patients With Stage III Colon Cancer Treated With Chemotherapy

| Characteristic | SEER-Medicare |

NYSCR-Medicare |

NCCN |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adjusted* OR | 95% CI | Adjusted OR | 95% CI | Adjusted OR | 95% CI | |

| Received oxaliplatin | ||||||

| No. | 610 | 124 | 66 | |||

| % | 34 | 28 | 46 | |||

| Age, years | ||||||

| 75-79 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| 80-84 | 0.37 | 0.29 to 0.46 | 0.51 | 0.31 to 0.83 | 0.07 | 0.02 to 0.27 |

| 85+ | 0.08 | 0.05 to 0.15 | 0.33 | 0.16 to 0.64 | 0.28 | 0.04 to 2.08 |

| Sex | ||||||

| Female | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Male | 1.12 | 0.89 to 1.42 | 1.04 | 0.66 to 1.64 | 2.49 | 0.81 to 7.67 |

| Comorbidity† | ||||||

| 0/None | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| 1/Mild | 0.87 | 0.68 to 1.12 | 1.21 | 0.67 to 2.16 | 0.61 | 0.18 to 2.08 |

| 2+/Moderate | 0.59 | 0.42 to 0.81 | 0.46 | 0.19 to 1.03 | 0.75 | 0.16 to 3.57 |

| Race | ||||||

| White | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Black | 1.31 | 0.82 to 2.07 | 0.28 | 0.04 to 1.06 | 0.03 | 0.001 to 0.77 |

| Asian/Other | 0.58 | 0.36 to 0.91 | 0.52 | 0.16 to 1.43 | 0.08 | 0.005 to 1.21 |

| Income | ||||||

| Top quartile | 1.36 | 1.00 to 1.87 | 1.16 | 0.61 to 2.22 | 1.75 | 0.30 to 10.2 |

| 3rd quartile | 1.03 | 0.75 to 1.42 | 2.18 | 1.17 to 4.14 | 1.66 | 0.26 to 10.5 |

| 2rd quartile | 0.83 | 0.60 to 1.15 | 0.89 | 0.48 to 1.66 | 2.19 | 0.40 to 12.1 |

| Bottom quartile | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Diagnosis Year | ||||||

| 2004 | 1 | 1 | — | |||

| 2005 | 2.23 | 1.62 to 3.06 | 1.89 | 1.07 to 3.37 | 1 | |

| 2006 | 4.19 | 3.00 to 5.85 | 4.43 | 2.55 to 7.88 | 0.18 | 0.02 to 1.48 |

| 2007 | 4.55 | 3.28 to 6.29 | — | 0.34 | 0.04 to 2.74 | |

| 2008 | — | — | 1.70 | 0.22 to 13.2 | ||

| 2009 | — | — | 0.23 | 0.03 to 1.97 | ||

Abbreviations: NCCN, National Comprehensive Cancer Network; NYSCR, New York State Cancer Registry; OR, odds ratio.

ORs are adjusted for all variables in the table.

Comorbidity is measured with the Charlson Comorbidity Index in NCCN, the Deyo- Klabunde modification in SEER-Medicare, and the Deyo modification in NYSCR-Medicare.

Footnotes

See accompanying editorial on page 2576; listen to the podcast by Dr Muss at www.jco.org/podcasts

Support information appears at the end of this article.

Authors' disclosures of potential conflicts of interest and author contributions are found at the end of this article.

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Although all authors completed the disclosure declaration, the following author(s) indicated a financial or other interest that is relevant to the subject matter under consideration in this article. Certain relationships marked with a “U” are those for which no compensation was received; those relationships marked with a “C” were compensated. For a detailed description of the disclosure categories, or for more information about ASCO's conflict of interest policy, please refer to the Author Disclosure Declaration and the Disclosures of Potential Conflicts of Interest section in Information for Contributors.

Employment or Leadership Position: None Consultant or Advisory Role: Til Stürmer, GlaxoSmithKline (U); Richard M. Goldberg, sanofi-aventis (C); Jeffrey A. Meyerhardt, Bayer Healthcare Pharmaceuticals (C), sanofi-aventis (C) Stock Ownership: None Honoraria: None Research Funding: Til Stürmer, Merck, sanofi-aventis; Richard M. Goldberg, sanofi-aventis; Jeffrey A. Meyerhardt, AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb Expert Testimony: None Other Remuneration: None

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: Hanna K. Sanoff, William R. Carpenter, Til Stürmer, Richard M. Goldberg, Christopher F. Martin, Jason P. Fine, Deborah Schrag

Financial support: William R. Carpenter, Deborah Schrag

Administrative support: William R. Carpenter, Til Stürmer, Joyce Niland, Maria J. Schymura, Deborah Schrag

Provision of study materials or patients: Katherine L. Kahn, Maria J. Schymura, Deborah Schrag

Collection and assembly of data: Christopher F. Martin, Joyce Niland, Katherine L. Kahn, Maria J. Schymura, Deborah Schrag

Data analysis and interpretation: Hanna K. Sanoff, William R. Carpenter, Til Stürmer, Richard M. Goldberg, Christopher F. Martin, Jason P. Fine, Nadine Jackson McCleary, Jeffrey A. Meyerhardt, Katherine L. Kahn, Maria J. Schymura, Deborah Schrag

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

Affiliations

Hanna K. Sanoff, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA; William R. Carpenter, Til Stürmer, Richard M. Goldberg, Christopher F. Martin, and Jason P. Fine, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, NC; Nadine Jackson McCleary, Jeffrey A. Meyerhardt, and Deborah Schrag, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Boston, MA; Joyce Niland, City of Hope Cancer Center and Data Coordinating Center for the National Comprehensive Cancer Center, Duarte; Katherine L. Kahn, RAND Corporation, Santa Monica; Katherine L. Kahn, David Geffen School of Medicine at University of California, Los Angeles, CA; and Maria J. Schymura, New York State Cancer Registry, New York State Department of Health, Albany, NY.

Support

Primary funding for this project was obtained from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), US Department of Health and Human Services as part of the Developing Evidence to Inform Decisions about Effectiveness program; contracts No. HSA290-2005-0016-I-TO7-WA1, 36-BWH-1, and HHSA290-2005-0040-I-TO4-WA1, 36-UNC. The authors of the report are responsible for its content. Statements in the report should not be construed as endorsement by the AHRQ or of any funding agencies that funded creation of data sets used in these analyses.

The project relied on existing data sources that were created from other funded grants. These sources include the National Cancer Institute (NCI; grant No. R01CA131847, D.S., principal investigator) funded work that facilitated creation of the New York State–Medicaid-Medicare data. The NCI also curates the SEER-Medicare data. The Cancer Care Outcomes Research and Surveillance Consortium (CanCORS) study was supported by grants from the National Cancer Institute to the CanCORS Statistical Coordinating Center and Primary Data Collection and Research Centers (grants No. U01 CA093344, U01 CA093332, U01 CA093324, U01 CA093348, U01 CA093329, U01 CA01013, and U01 CA093326), and by a grant from the Department of Veteran's Affairs to the Durham VA Medical Center (grants No. U01CDA093344, MOU, and HARO03-438MO-03). Also supported by the National Institute on Aging, (grant No. R01AG023178, T.S., principal investigator), the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (grant No. 2P30DK034987, R.S., principal investigator), and the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention through the Association of Schools of Public Health (grant No. S3888, M.J.S., principal investigator).

Funding sources and collaborating agencies were not directly involved with the design, analysis and interpretation, or writing of the manuscript. Final manuscript approval was provided by AHRQ, the CanCORS publication committee, the New York State Cancer Registry, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network publication committee, and SEER-Medicare.

REFERENCES

- 1.American Cancer Society: Colorectal cancer facts and figures, 2011. http://www.cancer.org/acs/groups/content/@epidemiologysurveilance/documents/document/acspc-028323.pdf.

- 2.Howlader N, Noone A, Krapcho M, et al. SEER cancer statistics review. 1975-2008, 2011. http://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2008/

- 3.SEER Program: Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute, Division of Cancer Control and Population Sciences, Surveillance Research Program, Cancer Statistics Branch; SEER*Stat Database: Incidence—SEER 17 Regs Research Data Hurricane Katrina Impacted Louisiana Cases, November 2010 Submission (1973-2008 varying)—Linked To County Attributes—Total U.S., 1969-2009 Counties. released April 2011, based on the November 2010 submission. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gill S, Loprinzi CL, Sargent DJ, et al. Pooled analysis of fluorouracil-based adjuvant therapy for stage II and III colon cancer: Who benefits and by how much? J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:1797–1806. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.09.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.André T, Boni C, Mounedji-Boudiaf L, et al. Oxaliplatin, fluorouracil, and leucovorin as adjuvant treatment for colon cancer. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:2343–2351. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa032709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.André T, Boni C, Navarro M, et al. Improved overall survival with oxaliplatin, fluorouracil, and leucovorin as adjuvant treatment in stage II or III colon cancer in the MOSAIC trial. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:3109–3116. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.6771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kuebler JP, Wieand HS, O'Connell MJ, et al. Oxaliplatin combined with weekly bolus fluorouracil and leucovorin as surgical adjuvant chemotherapy for stage II and III colon cancer: Results from NSABP C-07. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:2198–2204. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.08.2974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sargent DJ, Goldberg RM, Jacobson SD, et al. A pooled analysis of adjuvant chemotherapy for resected colon cancer in elderly patients. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:1091–1097. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa010957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McCleary NAJ, Meyerhardt J, Green E, et al. Impact of older age on the efficacy of newer adjuvant therapies in > 12,500 patients with stage II/III colon cancer: Findings from the ACCENT database. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(suppl):170s. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.49.6638. abstr 4010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Warren JL, Klabunde CN, Schrag D, et al. Overview of the SEER-Medicare data: Content, research applications, and generalizability to the United States elderly population. Med Care. 2002;40(suppl):IV-3-18. doi: 10.1097/01.MLR.0000020942.47004.03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.National Comprehensive Cancer Network: NCCN Oncology Outcomes Database. http://www.nccn.org/network/business_insights/outcomes_database/outcomes.asp.

- 12.Romanus D, Weiser MR, Skibber JM, et al. Concordance with NCCN Colorectal Cancer Guidelines and ASCO/NCCN Quality Measures: An NCCN institutional analysis. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2009;7:895–904. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2009.0059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Piccirillo JF, Tierney RM, Costas I, et al. Prognostic importance of comorbidity in a hospital-based cancer registry. JAMA. 2004;291:2441–2447. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.20.2441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ayanian JZ, Chrischilles EA, Fletcher RH, et al. Understanding cancer treatment and outcomes: The Cancer Care Outcomes Research and Surveillance Consortium. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:2992–2996. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kahn KL, Adams JL, Weeks JC, et al. Adjuvant chemotherapy use and adverse events among older patients with stage III colon cancer. JAMA. 2010;303:1037–1045. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Saltz LB, Niedzwiecki D, Hollis D, et al. Irinotecan fluorouracil plus leucovorin is not superior to fluorouracil plus leucovorin alone as adjuvant treatment for stage III colon cancer: Results of CALGB 89803. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:3456–3461. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.11.2144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Van Cutsem E, Labianca R, Bodoky G, et al. Randomized phase III trial comparing biweekly infusional fluorouracil/leucovorin alone or with irinotecan in the adjuvant treatment of stage III colon cancer: PETACC-3. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:3117–3125. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.21.6663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Goldberg RM, Sargent DJ, Thibodeau SN, et al. Adjuvant mFOLFOX6 plus or minus cetuximab in patients with KRAS mutant resected stage III colon cancer: NCCTG Intergroup phase III trial N0147. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(suppl):262s. abstr 3508. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Allegra CJ, Yothers G, O'Connell MJ, et al. Phase III trial assessing bevacizumab in stages II and III carcinoma of the colon: Results of NSABP protocol C-08. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:11–16. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.30.0855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, et al. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: Development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40:373–383. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Klabunde CN, Potosky AL, Legler JM, et al. Development of a comorbidity index using physician claims data. J Clin Epidemiol. 2000;53:1258–1267. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(00)00256-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Deyo RA, Cherkin DC, Ciol MA. Adapting a clinical comorbidity index for use with ICD-9-CM administrative databases. J Clin Epidemiol. 1992;45:613–619. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(92)90133-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bang D, Piccirillo J, Littenberg B, et al. The Adult Comorbidity Evaluation-27 Test–A new comorbidity index for patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2000;19(suppl):59s. abstr 1701. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Suissa S. Immortal time bias in pharmaco-epidemiology. Am J Epidemiol. 2008;167:492–499. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwm324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rubin DB. Estimating causal effects from large data sets using propensity scores. Ann Intern Med. 1997;127:757–763. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-127-8_part_2-199710151-00064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Parsons L. Reducing bias in a propensity score matched-pair sample using greedy matching techniques. http://www2.sas.com/proceedings/sugi26/p214-26.pdf.

- 27.Stürmer T, Rothman KJ, Avorn J, et al. Treatment effects in the presence of unmeasured confounding: Dealing with observations in the tails of the propensity score distribution—A simulation study. Am J Epidemiol. 2010;172:843–854. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwq198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schrag D, Cramer LD, Bach PB, et al. Age and adjuvant chemotherapy use after surgery for stage III colon cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2001;93:850–857. doi: 10.1093/jnci/93.11.850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Iwashyna TJ, Lamont EB. Effectiveness of adjuvant fluorouracil in clinical practice: A population-based cohort study of elderly patients with stage III colon cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:3992–3998. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.03.083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sundararajan V, Mitra N, Jacobson JS, et al. Survival associated with 5-fluorouracil-based adjuvant chemotherapy among elderly patients with node-positive colon cancer. Ann Intern Med. 2002;136:349–357. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-136-5-200203050-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Haller DG, Tabernero J, Maroun J, et al. Capecitabine plus oxaliplatin compared with fluorouracil and folinic acid as adjuvant therapy for stage III colon cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:1465–1471. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.33.6297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Goldberg RM, Tabah-Fisch I, Bleiberg H, et al. Pooled analysis of safety and efficacy of oxaliplatin plus fluorouracil/leucovorin administered bimonthly in elderly patients with colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:4085–4091. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.9039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Haller D, Cassidy J, Tabernero J, et al. Efficacy findings from a randomized phase III trial of capecitabine plus oxaliplatin verus bolus 5FU/LV for stage III colon cancer (NO16968): No impact of age on disease-free survival. Gastrointestinal Cancers Symposium; January 22-24, 2010; Orlando, FL. abstr 284. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yothers G, O'Connell MJ, Allegra CJ, et al. Oxaliplatin as adjuvant therapy for colon cancer: Updated results of NSABP C-07 trial, including survival and subset analyses. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:3768–3774. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.36.4539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sanoff HK, Carpenter WR, Martin CF, et al. Comparative effectiveness of oxaliplatin vs non–oxaliplatin-containing adjuvant chemotherapy for stage III colon cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2012;104:211–227. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djr524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]