Abstract

OBJECTIVE

To describe novel severity indices with which to quantify severity of trigonocephaly malformation in children diagnosed with isolated metopic synostosis.

METHODS

Computed tomographic scans of the cranium were obtained from 38 infants diagnosed with isolated metopic synostosis and 53 age-matched control patients. Volumetric reformations of the cranium were used to trace two-dimensional planes defined by the cranium-base plane and well-defined brain landmarks. For each patient, novel trigonocephaly severity indices (TSI) were computed from outline cranium shapes on each of these planes. The metopic severity index based on measurements of interlandmark distances was also computed and a receiver operating characteristic analysis used to compare the accuracy of classification based on TSIs versus that based on the metopic severity index.

RESULTS

The proposed TSIs are a sensitive measure of trigonocephaly malformation that can provide a classification accuracy of 96% with a specificity of 95%, in contrast with 82% of the metopic severity index at the same specificity level.

CONCLUSIONS

We completed exploratory analysis of outline-based severity measurements computed from computed tomographic image planes of the cranium. These TSIs enable quantitative analysis of cranium features in isolated metopic synostosis that may not be accurately detected by analytic tools derived from a sparse set of traditional interlandmark and semilandmark distances.

Keywords: Metopic synostosis, Severity indices, Shape analysis, Single-suture craniosynostosis, Trigonocephaly

Craniosynostosis refers to the premature fusion of one or more cranial sutures (metopic, sagittal, right or left coronal, or right or left lambdoid) that normally separate the bony plates of the cranium. In typically developing infants, open sutures allow the cranium to expand as the brain grows, producing relatively normal head shape. If one or more sutures are prematurely fused, there is restricted growth perpendicular to the fused sutures and compensatory growth in the cranium’s patent sutures, producing abnormal head shape (5). Surgery to release the fused suture is usually performed within the first year of life (17).

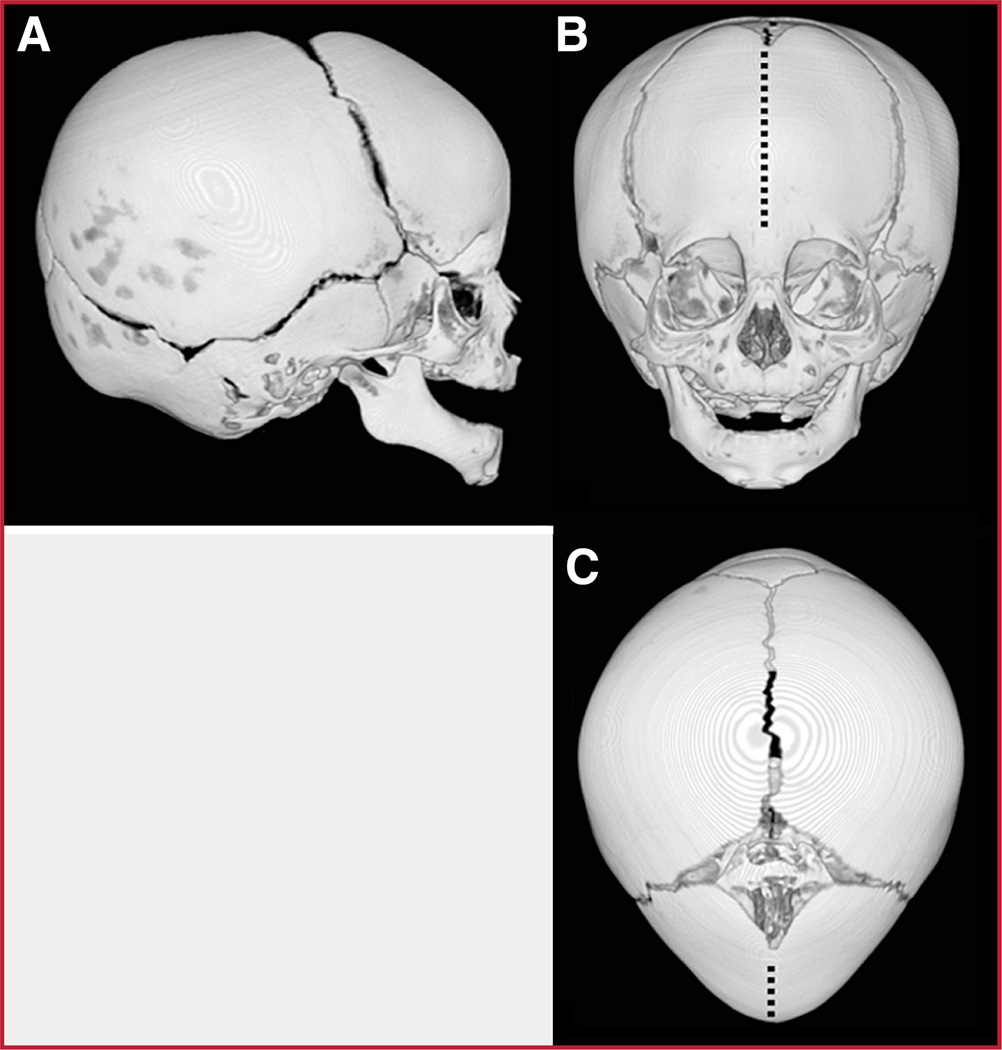

Single-suture (or “isolated”) synostosis is the most common form of craniosynostosis, with the prevalence of any single fused suture being approximately one in 2500 live births (28, 29). Among the isolated synostoses, fusions of the sagittal, coronal, and metopic sutures are most common. Metopic synostosis results in a triangular head shape, called trigonocephaly, which features a midline forehead ridge, frontotemporal narrowing, and an increased biparietal diameter (Fig. 1) (20).

FIGURE 1.

Volumetric reformations of the cranium of a patient affected with isolated metopic synostosis.

Imaging assessments, such as computed tomographic (CT) scans, are typically used to confirm the fused suture and to describe its impact on cranial morphology. In clinical practice, this assessment is largely descriptive and qualitative, based on visual inspection and categorization of images. Research often requires more precise measurements, however, which has motivated the development of various indices with which to quantify cranial dysmorphology. Such indices have thus far been used to quantify the severity of preoperative malformation (3, 12, 27, 32), to predict postsurgical outcomes (23), and to examine associations between cranial dysmorphology and neurodevelopmental functioning (3, 26).

Nearly all of these quantitative methods have been based on the calculation of linear distances between selected anatomic landmarks. For example, we developed a set of novel scaphocephaly shape indices for sagittal synostosis using ratios of head width and length based on distinct internal landmarks (27). Similarly, we developed landmark-based indices to characterize head shapes associated with metopic and unilateral coronal synostosis (16). Other investigators of metopic synostosis have defined severity ratings and predicted outcome based on measurements of the interparietal and intercoronal distance ratio (3), intercoronal and interorbital linear distances (23), and the intercanthal distance-to-midfacial width ratio (21). Apotentially more informative alternative to distance-based indices is the quantification of shape outlines. Because they can be used to precisely encode the geometry of complex objects, outlines are commonly used in medical image analyses to represent anatomic shapes (24). An outline-based approach may be particularly useful in quantifying the complex head shape associated with metopic synostosis. For example, in metopic synostosis, an outline-based method could be used to model the fit of an isosceles triangle to outlines of trigonocephalic craniums. Although trigonocephalic crania are not strictly triangular, their degree of approximation to this geometric form should reflect their severity of malformation caused by premature fusion of the metopic suture.

The goal of the present study was to develop and test trigonocephaly severity, computed from two-dimensional outline shapes of the calvaria. We tested the hypothesis that an isosceles triangle would more closely fit the outline shapes of cases with metopic synostosis than it would the shapes of normal, nonsynostotic craniums. We also performed an exploratory analysis to determine whether outline-based severity indices could provide a better characterization of trigonocephaly malformation of the cranium than indices based on linear distance measurements. In particular, we compared outline-based indices with the linear distance-based severity index of metopic synostosis recently described in Lin et al. (16).

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Participants

The participants of this study were 38 infants with metopic synostosis who were enrolled in a larger investigation called the Infant Learning Project (ILP). The ILP is a prospective, multicenter study in which we are investigating the neurobehavioral outcomes and genetic status of children with single-suture craniosynostoses, including metopic, sagittal, and unilateral coronal synostosis. This research has been described previously (10) and is in full compliance with Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act standards. Each of four participating centers (Children’s Hospital and Regional Medical Center in Seattle; Northwestern University in Chicago, Children’s Heath Care of Atlanta, and St. Louis Children’s Hospital) obtained independent institutional approval.

Cases

Infants were eligible if they had single-suture metopic synostosis, confirmed by CT scan; had not yet had reconstructive surgery; and were 30 months of age or younger at the time of recruitment. Exclusion criteria included the following: 1) premature birth (before 34 weeks’ gestation); 2) presence of major medical or neurological conditions (e.g., cardiac defects, seizure disorders, cerebral palsy, significant health conditions requiring surgical correction); 3) presence of three or more extracranial minor malformations, as defined in Leppig et al. (15); or 4) presence of major malformations. Twins were eligible to participate in the study when one or both had single-suture craniosynostosis. As of May 1, 2006, cases enrolled in the ILP constituted 86% of those eligible. Reasons for nonparticipation were primarily attributable to distance or time constraints, and a small number of cases could not be enrolled before cranial surgery. The 38 participants in the current study were all those having CT scans as of April 2006. Infants were referred to the ILP at the time of diagnosis by their treating surgeon or pediatrician. Diagnosis was confirmed intraoperatively. CT scans were obtained at each participating center, and de-identified imaging data were sent to Seattle for further analysis.

Controls

The control group consisted of 53 patients (34 boys and 19 girls) for whom CT scans of the cranium were obtained at Children’s Hospital Regional Medical Center for non-head shape-related indications (e.g., head trauma) and who were determined to have a normal head shape by an experienced pediatric radiologist (RWS). The median age was 12.3 months. Excluded patients included those whose indication for CT study was a suspected head shape malformation and whose cranial CT scans were assessed to be abnormal (mainly because of posterior deformational plagiocephaly).

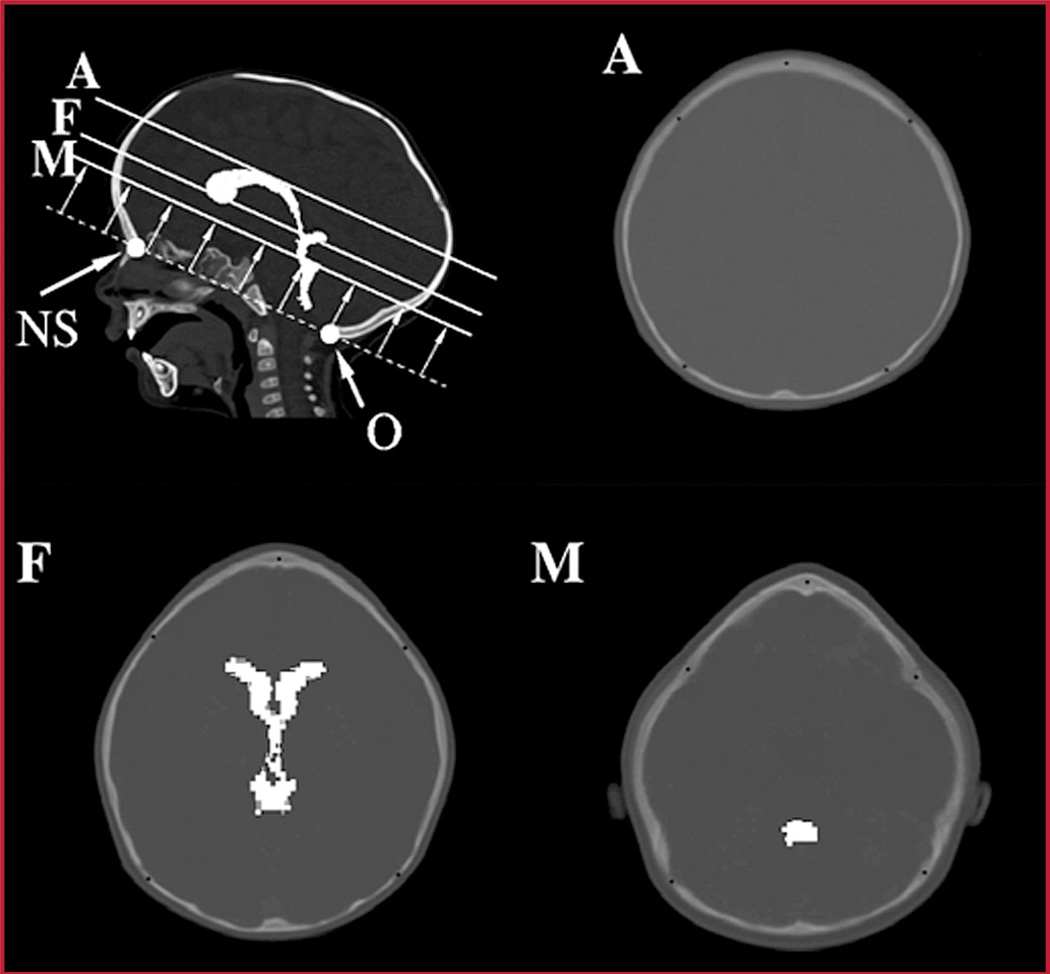

Linear Distance-based Metopic Severity Index

The metopic severity index (MSI) has been described previously as the product of three ratios (RA, RF, and RM), which are computed at three measurement planes defined by internal brain landmarks (Fig. 2) (16). The planes are parallel to the cranium base plane, which is defined by using the frontal nasal suture anteriorly and opisthion posteriorly. The A plane is at the top of the lateral ventricle, the F plane is at the foramina of Munro, and the M plane is at the level of the maximal dimension of the fourth ventricle. Each of the ratios is computed (at a given image plane) as the product (A/C) × (B/C). A is the bifrontal diameter measured at half the distance from the coronal sutures to the anteriormost portion of the frontal bones; B is the bifrontal diameter measured at the level of the coronal sutures; and C is the greatest biparietal diameter (Fig. 3). Measurement C is used as a normalization factor for cranium size. The bifrontal diameters A and B account for the region of the frontal bone that are most deformed by metopic synostosis, and it was hypothesized (16) that the normalized product of bifrontal diameters was, on average, much smaller for metopic cranium shapes than for normal controls on each of the imaged planes. Alternative normalization constants such as the perimeter or the area surrounded by the outline were considered. However, we found that the use of the greatest biparietal diameter resulted in more discriminative severity indices.

FIGURE 2.

Image analysis planes (A, F, and M). Trigonocephaly severity measures are computed from computed tomographic (CT) image slices located at three different image planes. The A plane is at the top of the lateral ventricle, the F plane is at the foramina of Munro, and the M plane is at the level of the maximal dimension of the fourth ventricle. Computer enhancement of ventricles is provided for illustration purposes. NS, nasa suture; O, opisthion.

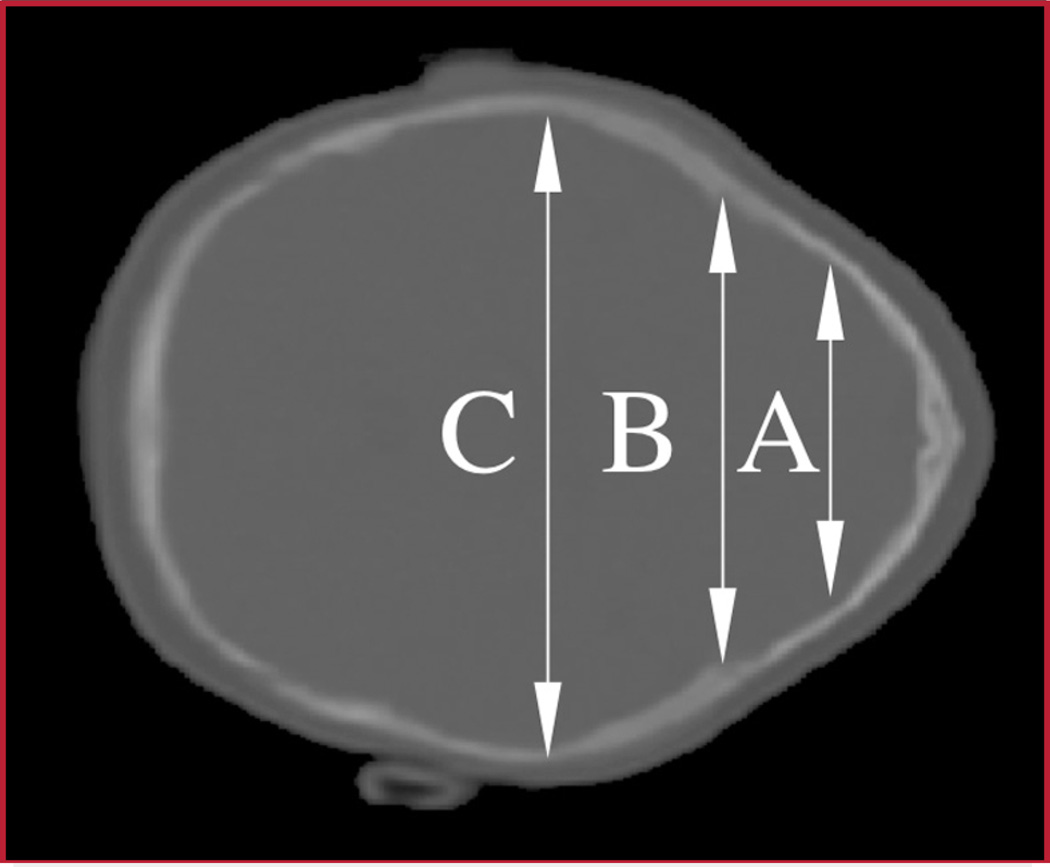

FIGURE 3.

CT image of a patient affected with metopic synostosis that shows the linear distances used to compute the metopic severity index. The distances are as follows: the bifrontal diameter at the level of the coronal sutures (B), the bifrontal diameter at half the distance from the coronal sutures to the anteriormost portion of the frontal bones (A), and the biparietal diameter (C).

Outline-based Trigonocephaly Severity Indices

After shape outlines were extracted from CT scans using standard image processing techniques (8), the computation of outline-based trigonocephaly severity indices (TSI) took place in three stages, described below: 1) calculation of coordinates representing shape outlines; 2) normalization of outline coordinates; and 3) fitting isosceles triangles to the normalized coordinates.

Calculation of Coordinates

Polar coordinates were used to represent the points that constitute an outline (Fig. 4). The origin of the polar coordinate system was set at the centroid of the outline (point O in Fig. 4B), which was computed by using a semiautomated algorithm consisting of the following steps for each CT image: 1) a principal component analysis algorithm was used to find the orientation of the principal axes of the segmented shape and the centroid; 2) the orientation of the axes was verified by an experienced pediatric radiologist (RWS); and 3) the location of the metopic suture R was computed by a simple algorithm that found the intersection between one of the principal axes and the segmented bone outline shape.

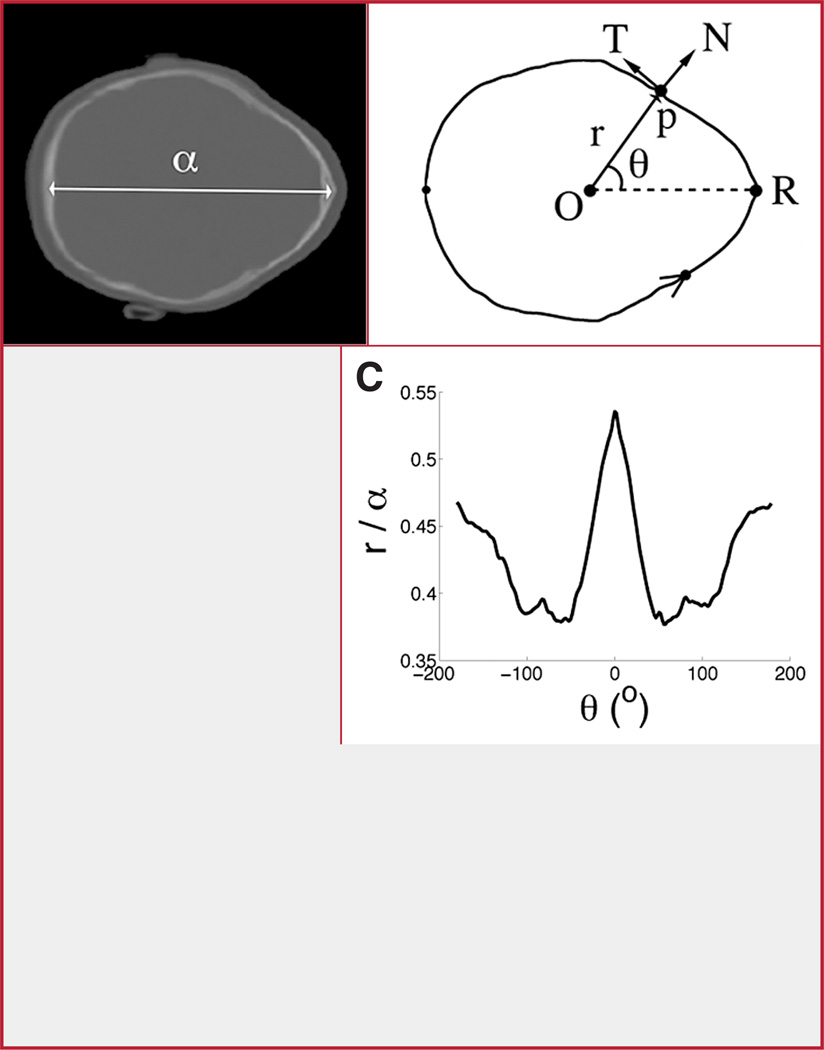

FIGURE 4.

Standard image processing techniques can be used to segment a bone CT image (A) to compute an outline (B) whose origin is defined by its corresponding centroid (O). The outline is represented in polar coordinates (r, θ). The coordinate r is the axial distance from the origin to the p (the length of the line segment Op). The coordinate θ is the angle that makes the line segment Op with the polar axis OR. The orientation of p is defined by the direction of its corresponding tangent (T) and normal (N) vectors. The normalized (ρ, θ) coordinates (with ρ = r/α) can be represented in a scatterplot of θ versus ρ (C) to produce normalized polar representation (NPR). This representation of outline shape enables the computation of severity indices that are scale invariant. The normalization constant α is defined as the head length measured in A.

Normalization of Outline Coordinates

Severity indices were computed from a normalized polar representation (NPR) of outline shape (i.e., a plot of the polar coordinates corresponding to the points along the outline), with r plotted versus θ (Fig. 4C). The polar representation was normalized to produce a scale invariant severity index (25) and to vertically shift the polar coordinates so that the minimum value of the curve had a y ordinate equal to 0 (compare the scatter plots in Figs. 4C and 5, B and D). The shift allowed for defining the proposed severity indices as a measure of trigonocephaly.

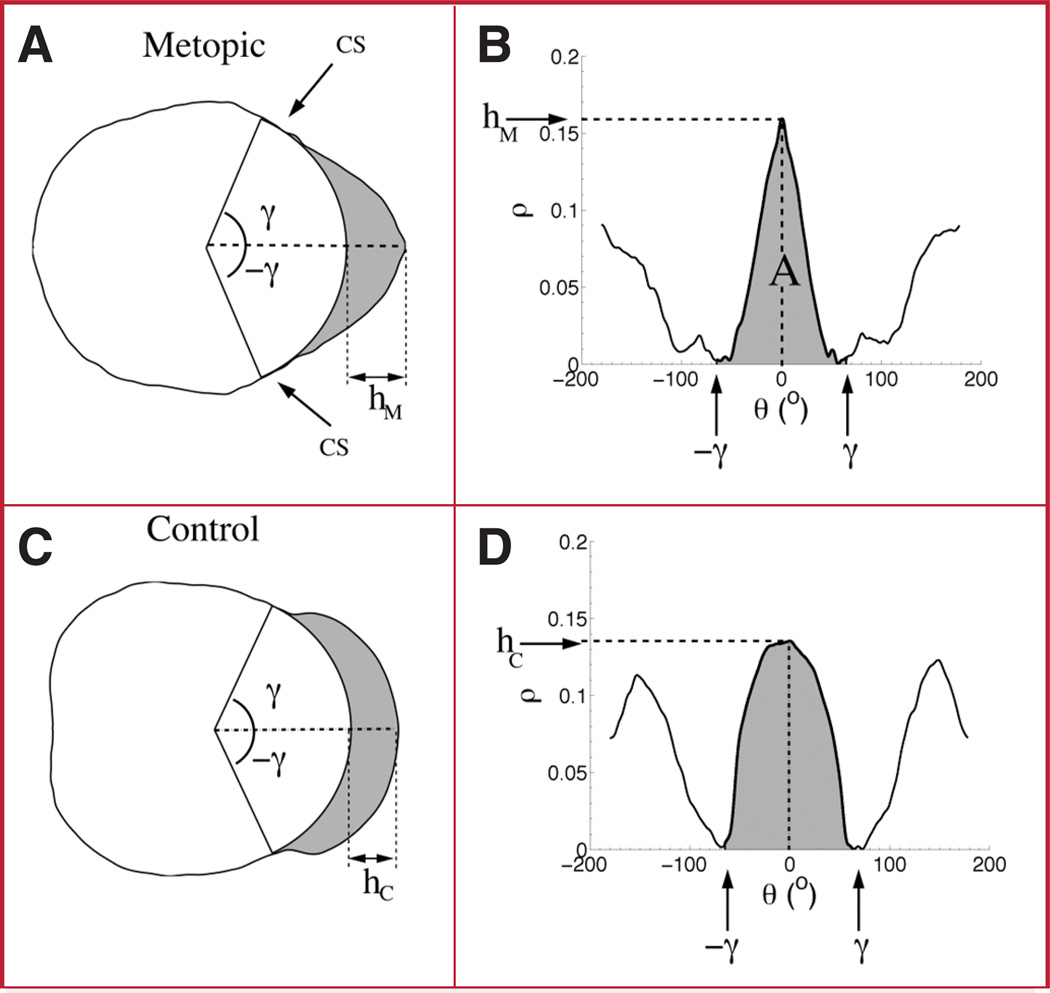

FIGURE 5.

Trigonocephaly severity indices (TSI) are calculated from NPRs (B and D), which are derived from outline cranium shapes (A and C). A and B show the outline shape and NPR of a patient affected with isolated metopic synostosis. C and D show the same plots of a nonsynostotic control. Note that the NPR corresponding to the affected patient (B) resembles an isosceles triangle, unlike the shape shown in the NPR of the control (D). The angle γ and the ordinates hM and hC are parameters that are used in the computation of the TSIs (see Fitting Isosceles Triangles to the Normalized Coordinates under Patients and Methods). The arrows labeled CS in A indicate the approximate location of the coronal sutures.

Fitting Isosceles Triangles to the Normalized Coordinates

Measuring the TSI essentially involves fitting an isosceles triangle to the NPR of a cranium outline and measuring how well the triangle fits the outline. To fit an isosceles triangle to the NPR, we defined A in Figure 6B as the value of the area of the triangle fit under the main peak of the NPR of the outline shape. The area of the main peak is specified in terms of the interval [−γ, γ], where γ was set to 67 degrees. This value of γ was selected to maximize the performance of a classification function (to be described in the next section) that discriminates between metopic and normal control head shapes. This value of γ also corresponds to the average location (polar angle) of the coronal sutures measured across the population of metopic shapes (Fig. 5, B and D). The height of the triangle, hM, corresponds to the value of the curve at the abscissa θ = 0 (i.e., the corresponding location of the metopic suture on the outline).

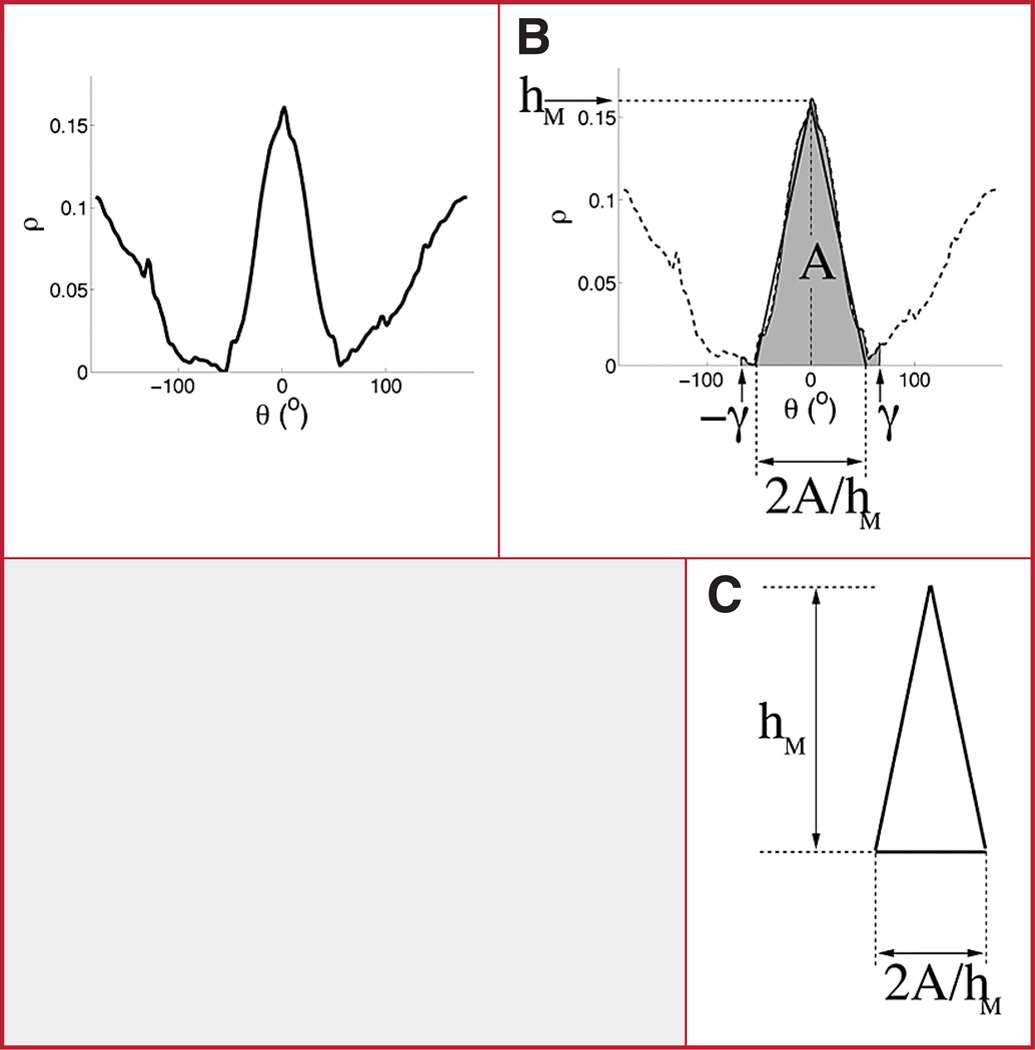

FIGURE 6.

A, NPR of an outline shape. B, TSI is computed as the base of an isosceles triangle that approximates the profile of the NPR’s main section (curve above shaded area), which encodes the shape information for the frontal bones. The base is computed as 2A/(180)hM, where 180 is a normalization factor that ensures that the TSI takes values between 0 and 1. C, triangle fitted to the outline representation.

Using the formula for calculating the area of a triangle (i.e., half the product of the length of the base and the height of the triangle), the area of the fitted triangle is defined as A = bMhM/2, where bM is the base of the triangle. Although bM will not be observed directly, it can be calculated from A and hM as bM = 2a/hM.

That is, we assume that A and hM are the given, and we use them to compute the base bM. By computing bM in terms of A and hM, we are implicitly fitting a triangle to the main peak of the cranium NPR representation. The TSI is equal to the bM, normalized by dividing by 180, that is: TSI = Base of the fitted triangle/180 = (2a/hM)/180.

Normalization ensures that the TSI takes values between 0 and 1, as bM ranges in the interval [0,180] degrees in the NPR plot (Fig. 6). A TSI value close to 0 suggests a very narrow triangular shape, whereas a value close to 1 suggests a wider shape.

Data Analysis

Receiver Operating Characteristic Curves

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis (18) was used to measure the accuracy of the TSIs and MSIs to distinguish the outline shapes of metopic cases versus control group participants. With continuous shape measurements such as the TSI or MSI, one needs to choose a threshold value above which a cranium shape would be classified as being malformed and below which the cranium shape would be classified as unaffected. The sensitivity is defined as the proportion of abnormal cranium shapes that are indeed abnormal (i.e., test above some threshold value). The specificity is defined as the proportion of unaffected cranium shapes that are indeed unaffected (i.e., test below some threshold value). The ROC curve is a plot of sensitivity versus (1 − specificity) for all possible threshold values. An overall measure of accuracy can be calculated by computing the area under the resulting curve (AUC). Specifically, the average classification error can be computed as E = (1 − AUC) × 100%.

The best possible accuracy, or a perfect “test,” corresponds to an AUC of 1. We studied the error rate and sensitivity as a function of the specificity to compare the performance of the various proposed trigonocephaly shape descriptors.

Confidence Intervals for ROC Curves

We computed bootstrap confidence intervals for ROC curves and their corresponding AUCs. The bootstrap is a nonparametric technique for assigning measures of accuracy to statistical estimates; that is, the resampling method does not rely on assumptions about the underlying distributions among affected and unaffected individuals (4). We computed descriptive statistics (Table 1) and ROC curves for the proposed severity indices at each of the image planes (Fig. 7, A and B).

TABLE 1.

Descriptive statistics for the trigonocephaly severity index and metopic severity index computed at the A, F, and M image planesa

| Patient group |

Severity index |

Level | Mean | Standard deviation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Metopic synostosis | TSI | A | 0.39 | 0.08 |

| F | 0.35 | 0.05 | ||

| M | 0.32 | 0.04 | ||

| MSIb | 0.07 | 0.03 | ||

| Nonsynostotic control | TSI | A | 0.50 | 0.17 |

| F | 0.51 | 0.06 | ||

| M | 0.52 | 0.06 | ||

| MSIb | 0.19 | 0.05 | ||

TSI, trigonocephaly severity index; MSI, metopic severity index.

MSI incorporates data extracted from all three image planes: A, F, and M.

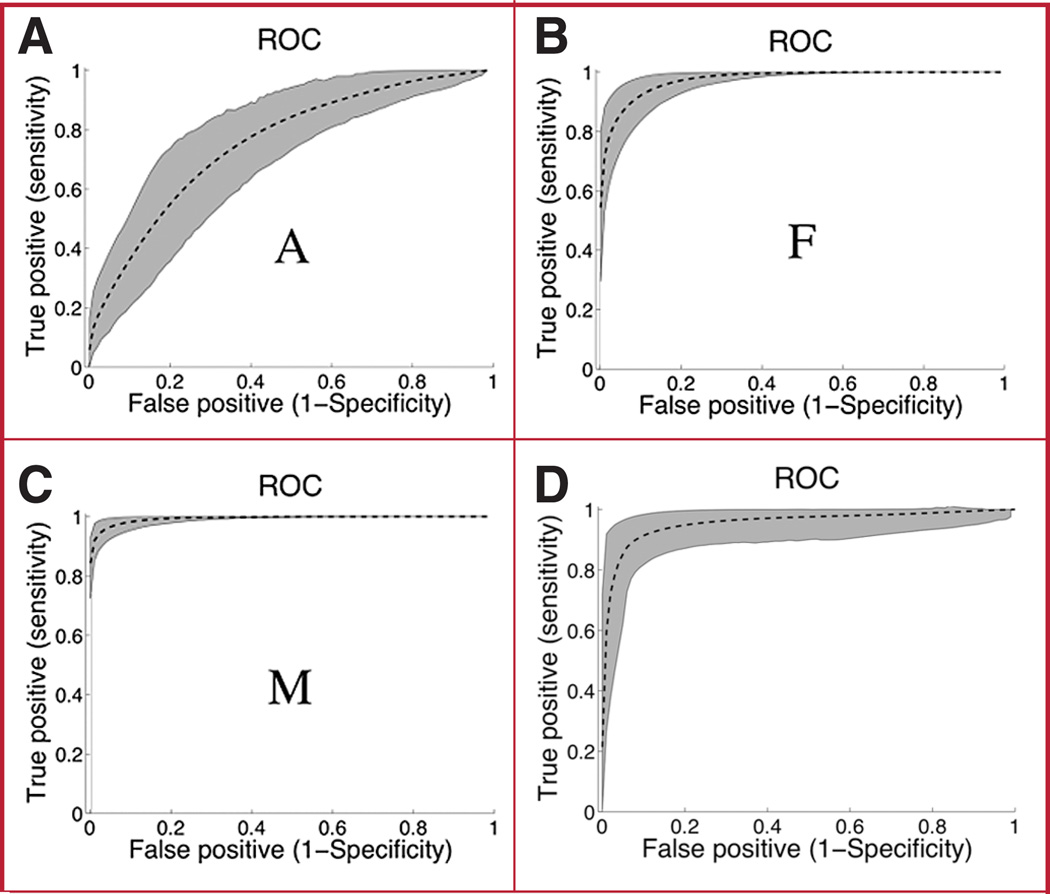

FIGURE 7.

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves for classification of metopic synostosis versus nonsynostotic cranium outlines by using the TSIs (TSI-A, -F, and -M) and the metopic severity index.

RESULTS

Descriptive Statistics

The distribution of the TSI scores for patients affected by metopic synostosis was similar in the three planes, ranging from 0.32 to 0.39, with a standard deviation on the order of 0.08 (Table 1). For control patients, the distribution of TSI scores ranged from 0.5 to 0.52, with a standard deviation on the order of 0.17. The observed differences between populations (at a given plane) were significant in all cases (P < 0.001). The distribution of MSI scores was 0.07 ± 0.03 for affected patients and 0.19 ± 0.05 for controls. The differences in MSI between populations were also significant.

Accuracy Analysis

Accuracy of classification of metopic synostosis of the TSIs and the MSI, measured by the AUC, ranged from 0.74 to 0.98 for the various indices and for different image planes (Table 2). Severity indices computed at the F and M image levels are more accurate than those computed at the A level (Fig. 7A). At this level, the error rate is roughly 26%. On average, TSIs at the M level performed better than the MSI.

TABLE 2.

Area under the curve calculated from receiver operating characteristic curves and their corresponding 95% confidence intervals computed from the receiver operating characteristic curves for all trigonocephaly severity indicesa

| Severity index | Level | AUC | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|

| TSI | A | 0.74 | 0.65–0.82 |

| F | 0.97 | 0.95–0.98 | |

| M | 0.98 | 0.98–0.99 | |

| MSIb | 0.96 | 0.90–0.99 | |

AUC, area under the curve; CI, confidence interval; TSI, trigonocephaly severity index; MSI, metopic severity index.

MSI incorporates data extracted from all three image planes: A, F, and M.

Sensitivity and Specificity

Indices for the A plane were computed, but error rates were on the order of 30% (data not shown). The TSIs measured on the M plane had lower error rates than the other severity indices and other measurement planes (Table 3); it provided sensitivity of 97 and 95% for specificity of 95 and 97.5%, respectively, compared with those of the MSI (83 and 76%, respectively).

TABLE 3.

Sensitivity and the corresponding 95% confidence interval for trigonocephaly severity indices computed at the F and M image planesa

| Severity Index | Level | Sensitivity | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|

| Specificity = 0.95 | |||

| TSI | F | 0.86 | 0.74–0.96 |

| M | 0.97 | 0.93–0.99 | |

| MSIb | 0.83 | 0.59–0.94 | |

| Specificity = 0.975 | |||

| TSI | F | 0.79 | 0.61–0.92 |

| M | 0.95 | 0.89–0.99 | |

| MSIb | 0.76 | 0.45–0.93 | |

CI, confidence interval; TSI, trigonocephaly severity index; MSI, metopic severity index.

MSI incorporates data extracted from both image planes: F and M.

DISCUSSION

We compared the accuracy of a linear distance-based (MSI) and outline shape-based (TSI) severity indices for classifying metopic synostotic cranium shapes. The TSIs appeared more accurate than the MSI. To the extent that this difference is because the MSI is based on linear distances between landmarks, we would also expect the TSIs to outperform the other previously proposed approaches also based on interlandmark or semilandmark distances (33). Such descriptors may lack sensitivity because they incorporate very limited sampling over the whole cranium. In contrast, the TSIs take into consideration global information regarding an outline shape that cannot be captured with a sparse set of distance measurements. Although we did not compare our approaches to those developed by other groups, at least one other group has reported classification error rates (14). Their approach based on distances between landmarks led to relatively large classification error rates, in the range of 18 to 28%; analysis of the sensitivity and specificity of the proposed classifiers was not provided in the study. We cannot directly compare our proposed methods to volume-based approaches (1, 22) or to approaches that only use qualitative assessments of shape (2, 7, 30–32).

In principle, our TSIs can be computed from outlines that cover the entire cranium volume. However, the computation of severity indices on every single slice of a CT volume may not be necessary. We found that measurement at the widest portion of the fourth ventricle (M image level) produced the most discriminative TSI. These results differ from a similar analysis of scaphocephaly shape descriptors for classifying isolated sagittal synostosis, in which we found that the descriptors measured at the top of the lateral ventricle (A image level) were the most accurate descriptors (27). These differences likely represent true differences in how scaphocephalic and trigonocephalic cranium outline shapes change across different cranium planes.

To date, shape analysis of metopic synostosis has been used in clinical and research settings to predict the outcome of reconstructive procedures (2, 3, 6, 10, 11, 19, 21–23). There are many other practical applications for which our proposed severity indices would be useful. For instance, these quantitative shape descriptors may facilitate surgical decision making; more rigorous studies of the natural history of metopic ridging and synostosis; the study of surgical outcomes; and studies of the association between cranium shapes and patient characteristics such as neurocognitive development or genotype.

Reproducibility of TSI Values in Clinical Settings

Although there are technical complexities in the calculation of the proposed severity indices, the practical implementation of the algorithm is straightforward. We have implemented a multiplatform user interface (e.g., Windows, Linux, Mac, and Sun) that enables the computation of hundreds of severity indices from CT images in a few seconds. The most time-consuming step involves extraction of the CT images by an experienced pediatric radiologist. Overall, the manual extraction process takes 3 minutes on average per patient. Once this step is completed, however, the computation of the indices takes a few milliseconds on a standard laptop computer running at 2 GHz. We are currently testing standard machine vision techniques to automate the entire process and believe that our proposed methods could be used efficiently in routine clinical and research applications requiring a measure of metopic synostosis severity. The exponential growth of computer power observed in recent years could enable a cost-effective implementation of our technology in the very near future.

Future Applications

Patients with metopic synostosis usually have a component of orbital hypotelorism (5), which is a significant part of the deformity. Untreated hypotelorism can result in poor outcome of surgery. Although beyond the scope of this project, it would be of value to determine the degree of association between our proposed indices and the decreased intraorbital distance in affected patients. Equally valuable would be the study of a possible association between the severity of the trigonocephaly malformation and the outcome of surgery. These tasks could be accomplished by means of standard correlation or regression analyses.

Trigonocephaly caused by metopic synostosis is often accompanied by compensatory changes accommodating the decreased volume of the anterior cranium by means of secondary increases in height or width of the posterior cranium (5). Although our TSIs quantify the degree of frontal deformation, they also encode information about the overall cranium shape. This is because our indices are computed from outline shapes at different cranium levels. For instance, severity indices computed at the F and M levels are constructed from outline shapes that consider both frontal and posterior regions of the cranium. However, we concede that it would be interesting to determine whether there is shape information related to compensatory changes in the posterior part of the cranium that is not captured by our TSI but that may be relevant in the quantitative description of metopic cranium malformation. Future studies of cranium morphology in metopic synostosis will determine the degree to which posterior cranium changes are associated with the trigonocephaly malformation and whether such association may imply a causal relationship. Finally, we note that patients with posterior symmetric positional plagiocephaly may also have a triangular head shape, and it would be useful to study whether the proposed TSI can separate these patients from true metopic synostosis.

CONCLUSION

We have presented an approach for quantifying the severity of trigonocephaly resulting from metopic craniosynostosis. We performed an exploratory analysis and showed that the TSIs, which are novel severity indices based on cranium outline shapes, better characterize trigonocephaly malformation than the MSI, which is based on linear distances. Our results would be strengthened in the future by direct comparison with other previously proposed approaches and by applications beyond classification. Nevertheless, this exploratory analysis suggests that the TSI will be useful for quantifying the degree of trigonocephaly and could therefore be a useful tool in the study of metopic synostosis.

Acknowledgments

Disclosures

This research was supported by grant R01-DE 13813 from the National Institute of Craniofacial and Dental Research to the principal investigator (MLS) and in part by the Laurel Foundation Center for Craniofacial Research and the Jean Renny Craniofacial Endowment (MLC).

ABBREVIATIONS

- AUC

area under the curve

- CT

computed tomographic

- ILP

Infant Learning Project

- MSI

metopic severity index

- NPR

normalized polar representation

- ROC

receiver operating characteristic

- TSI

trigonocephaly severity index

Contributor Information

Salvador Ruiz-Correa, Department of Computer Science, Center for Mathematical Investigations, Guanajuato, Mexico, and Department of Diagnostic Imaging and Radiology, Children’s National Medical Center, Washington, D.C.

Jacqueline R. Starr, Departments of Pediatrics and Epidemiology, University of Washington, and Children’s Craniofacial Center, Seattle, Washington

H. Jill Lin, Stanford Molecular Imaging Scholars Program, Stanford University, Stanford, California

Kathleen A. Kapp-Simon, Department of Surgery, Northwestern University, and Cleft-Craniofacial Clinic, Shriners Hospitals for Children, Chicago, Illinois

Raymond W. Sze, Department of Diagnostic Imaging and Radiology, Children’s National Medical Center, Washington, D.C.

Richard G. Ellenbogen, Department of Neurosurgery, University of Washington, and Children’s Craniofacial Center, Seattle, Washington

Matthew L. Speltz, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Science, University of Washington, and Children’s Craniofacial Center, Seattle, Washington

Michael L. Cunningham, Department of Pediatrics, University of Washington, and Children’s Craniofacial Center, Seattle, Washington

REFERENCES

- 1.Anderson PJ, Netherway DJ, Abbott A, David DJ. Intracranial volume measurement of metopic craniosynostosis. J Craniofac Surg. 2004;15:1014–1018. doi: 10.1097/00001665-200411000-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aryan HE, Jandial R, Ozgur BM, Hughes SA, Meltzer HS, Park MS, Levy ML. Surgical correction of metopic synostosis. Childs Nerv Syst. 2005;21:392–398. doi: 10.1007/s00381-004-1108-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bottero L, Lajeunie E, Arnaud E, Marchac D, Renier D. Functional outcome after surgery for trigonocephaly. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1998;102:952–960. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bradley E, Tibshirani RJ. An Introduction to the Bootstrap. New York: CRC Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cohen MM, MacLean MC. Craniosynostosis: Diagnosis, Evaluation, and Management. ed 2. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cohen SR, Maher H, Wagner JD, Dauser RC, Newman MH, Muraszko KM. Metopic synostosis: Evaluation of aesthetic results. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1994;94:759–767. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Greenberg BM, Schneider SJ. Trigonocephaly: Surgical considerations and long term evaluation. J Craniofac Surg. 2006;17:528–535. doi: 10.1097/00001665-200605000-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Haralick RM, Shapiro LG. Computer and Robot Vision. New York: Addison-Wesley; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Deleted in proof.

- 10.Kapp-Simon KA, Figueroa A, Jocher CA, Schafer M. Longitudinal assessment of mental development in infants with nonsyndromic craniosynostosis with and without cranial release and reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1993;92:831–841. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kocabalkan O, Owman-Moll P, Sugawara Y, Friede H, Lauritzen C. Evaluation of a surgical technique for trigonocephaly. Scand J Plast Reconstr Surg Hand Surg. 2000;34:33–42. doi: 10.1080/02844310050160150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kolar JC, Salter EM. Preoperative anthropometric dysmorphology in metopic synostosis. Am J Phys Anthropol. 1997;103:341–351. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-8644(199707)103:3<341::AID-AJPA4>3.0.CO;2-T. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Deleted in proof.

- 14.Lele SR, Richtsmeier JT. An Invariant Approach to the Statistical Analysis of Shapes. New York: Chapman & Hall/CRC; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Leppig KA, Werler MM, Cann CI, Cook CA, Holmes LB. Predictive value of minor anomalies: I. Association with major malformations. J Pediatr. 1987;110:531–537. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(87)80543-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lin HJ, Ruiz-Correa S, Starr JR, Speltz ML. New severity indices for quantifying unicoronal and metopic synostosis. Presented at the 64th Annual Meeting of the American Clef Palate-Craniofacial Association Annual Meeting; April 23–28, 2007; Broomfield, Colorado. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Marsh JL, Jenny A, Galic M, Picker S, Vannier MW. Surgical management of sagittal synostosis: A quantitative evaluation of two techniques. Neurosurg Clin N Am. 1991;2:629–640. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mason SJ, Graham NE. Areas beneath the relative operating characteristics (ROC) and relative operating levels (ROL) curves: Statistical significance and interpretation. QJR Meteorol Soc. 2002;128:2145–2166. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moriyama E, Beck H, Iseda K, Saitoh N, Sakurai M, Matsumoto Y. Surgical correction of trigonocephaly: Theoretical basis and operative procedures. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo) 1998;38:110–115. doi: 10.2176/nmc.38.110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Oi S, Matsumoto S. Trigonocephaly (metopic synostosis): Clinical, surgical and anatomical concepts. Childs Nerv Syst. 1987;3:259–265. doi: 10.1007/BF00271819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Paige KT, Cohen SR, Simms C, Burstein FD, Hudgins R, Boydston W. Predicting the risk of reoperation in metopic synostosis: A quantitative CT scan analysis. Ann Plast Surg. 2003;51:167–172. doi: 10.1097/01.SAP.0000058498.64113.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Posnick JC, Armstrong D, Bite U. Metopic and sagittal synostosis: Intracranial volume measurements prior to and after cranio-orbital reshaping in childhood. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1995;96:299–315. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Posnick JC, Lin KY, Chen P, Armstrong D. Metopic synostosis: Quantitative assessment of presenting deformity and surgical results based on CT scans. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1994;93:16–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rangayyan MR. Biomedical Image Analysis. New York: CRC Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Richtsmeier JT, Deleon VB, Lele SR. The promise of geometric morphometrics. Am J Phys Anthropol. 2002;35:63–91. doi: 10.1002/ajpa.10174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ruiz-Correa S, Starr JR, Lin HJ, Kapp-Simon KA, Cunningham ML, Speltz ML. Severity of skull malformation is unrelated to neurobehavioral dysfunction in infants with sagittal synostosis. Cleft Palate Craniofac J. 2007;44:548–554. doi: 10.1597/06-190.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ruiz-Correa S, Sze RW, Starr JR, Lin HT, Speltz ML, Cunningham ML, Hing AV. New scaphocephaly severity indices of sagittal craniosynostosis: A comparative study with cranial index quantifications. Cleft Palate Craniofac J. 2006;43:211–221. doi: 10.1597/04-208.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shuper A, Merlob P, Grunebaum M, Reisner SH. The incidence of isolated craniosynostosis in the newborn infant. Am J Dis Child. 1985;139:85–86. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1985.02140030091038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Singer S, Bower C, Southall P, Goldblatt J. Craniosynostosis in Western Australia, 1908–1994: A population-based study. Am J Med Genet. 1999;83:382–387. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-8628(19990423)83:5<382::aid-ajmg8>3.0.co;2-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sullivan PK, Melsen B, Mulliken JB. Calvarial sutural abnormalities: Metopic synostosis and coronal deformation. An anatomic, three-dimensional radiographic, and pathologic study. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1990;86:1072–1077. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Warschausky S, Angobaldo J, Kewman D, Buchman S, Muraszko K, Azengart A. Early development of infants with unrelated metopic craniosynostosis. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2005;115:1518–1523. doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0000160270.27558.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Weinzweig J, Kirschner RE, Farley A, Reiss P, Hunter J, Whitaker LA, Bartlett SP. Metopic synostosis: Defining the temporal sequence of normal suture fusion and differentiating it from synostosis on the basis of computed tomography images. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2003;112:1211–1218. doi: 10.1097/01.PRS.0000080729.28749.A3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zumpano MP, Carson BS, Marsh JL, Vanderkolk CA, Richtsmeier JT. Three-dimensional morphological analysis of isolated metopic synostosis. Anat Rec. 1999;256:177–188. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0185(19991001)256:2<177::AID-AR8>3.0.CO;2-Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]