Abstract

Serotonin is produced by pulmonary arterial endothelial cells (PAEC) via tryptophan hydroxylase-1 (Tph1). Pathologically, serotonin acts on underlying pulmonary arterial cells, contributing to vascular remodeling associated with pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH). The effects of hypoxia on PAEC-Tph1 activity are unknown. We investigated the potential of a gene therapy approach to PAH using selective inhibition of PAEC-Tph1 in vivo in a hypoxic model of PAH. We exposed cultured bovine pulmonary arterial smooth muscle cells (bPASMCs) to conditioned media from human PAECs (hPAECs) before and after hypoxic exposure. Serotonin levels were increased in hypoxic PAEC media. Conditioned media evoked bPASMC proliferation, which was greater with hypoxic PAEC media, via a serotonin-dependent mechanism. In vivo, adenoviral vectors targeted to PAECs (utilizing bispecific antibody to angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) as the selective targeting system) were used to deliver small hairpin Tph1 RNA sequences in rats. Hypoxic rats developed PAH and increased lung Tph1. PAEC-Tph1 expression and development of PAH were attenuated by our PAEC-Tph1 gene knockdown strategy. These results demonstrate that hypoxia induces Tph1 activity and selective knockdown of PAEC-Tph1 attenuates hypoxia-induced PAH in rats. Further investigation of pulmonary endothelial-specific Tph1 inhibition via gene interventions is warranted.

Introduction

Pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) is a fatal disease with a poor prognosis and is characterized by increased pulmonary arterial pressure, increased pulmonary vascular resistance, and remodeling of the pulmonary vascular bed leading to right ventricular failure.1 Endothelial cell dysfunction, through altered production of endothelial cell vasoactive mediators, plays an integral role in mediating the structural and functional changes in the pulmonary vasculature associated with PAH. Although mutations in the gene-encoding bone morphogenetic protein receptor type II have been identified in over 70% of patients with heritable PAH,2 only ~20% of individuals with a bone morphogenetic protein receptor type II mutation develop PAH. Additional genetic and environmental factors therefore likely contribute to the development of PAH. Many studies have implicated serotonin in the development of PAH. For example, the 5-HT1B receptor (5-HT1BR)3 the serotonin transporter (SERT),4 and de novo synthesized serotonin5,6 have all been associated with development of PAH. The 5-HT1BR mediates vasoconstriction7 and proliferation8 in human pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells (hPASMCs). hPASMCs derived from idiopathic PAH patients exhibit increased SERT expression and this accounts for the increased serotonin-induced proliferation observed in these cells.9,10 Serotonin can also transactivate the platelet-derived growth factor receptor β (PDGFRβ), via SERT, in PASMCs leading to smooth muscle cell proliferation and migration.11

There are two active isoforms of tryptophan hydroxylase (Tph1 and Tph2).12 Tph2 appears exclusively expressed in the central nervous system13 while Tph1 is the rate limiting enzyme in peripheral serotonin biosynthesis.12 Although peripheral serotonin is predominantly produced by enterochromaffin cells in the gastrointestinal tract, evidence exists for local serotonin synthesis in other peripheral organs/tissues.14 Importantly, human pulmonary arterial endothelial cells (hPAECs) and pulmonary capillaries express Tph16,15 and are a source of local serotonin synthesis in the pulmonary circulation. Additionally, expression of the Tph1 gene is increased in the lungs and the PAECs of remodeled pulmonary arteries from patients with idiopathic PAH.6

We and others have recently shown that hypoxia-induced PAH and pulmonary vascular remodeling is ablated in mice deficient in Tph1.5,16 Both hypoxia and mechanical stretch induce increased Tph1 expression and serotonin release in fetal rabbit lung pulmonary neuroendocrine cells.17 Others have demonstrated inhibition of hypoxia- and monocrotaline-induced PAH using the nonspecific inhibitor of Tph1 and Tph2, p-chlorophenylalanine (p-CPA).18 While it is known that PAECs can synthesize serotonin, to date the effects of hypoxia on Tph1 expression in PAECs either in vivo or in vitro have not been determined.

Therapeutically, selective endothelial Tph1 inhibition has major advantages over inhibition of total peripheral serotonin synthesis as serotonin is involved in vasoconstriction, hemostasis and the control of immune responses.19,20 Moreover, serotonin is a precursor for melatonin21 and Tph1 deficiency is also related to increased bone mass.22 Gene therapy in PAH is a challenge due to the difficulty in achieving selective delivery of biological agents to the pulmonary vasculature. We wished to investigate whether in vivo inhibition of pulmonary endothelial Tph1 could provide a new therapeutic strategy.

To achieve this, we used the monoclonal antibody (mAb) 9B9 that has high affinity to angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) and demonstrates selective accumulation in rat, hamster23 and primates, including human,24 lung tissue. We used this to retarget adenovirus (Ad) and address the effect of selective endothelial Tph1 inhibition (with short hairpin RNAs (shRNAs) against Tph1) on the development of hypoxia-induced PAH.25,26,27

Results

Effects of PAEC conditioned media on proliferation of bPASMCs

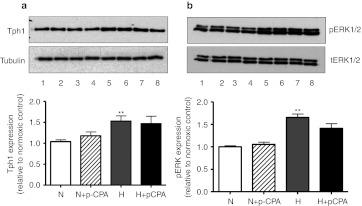

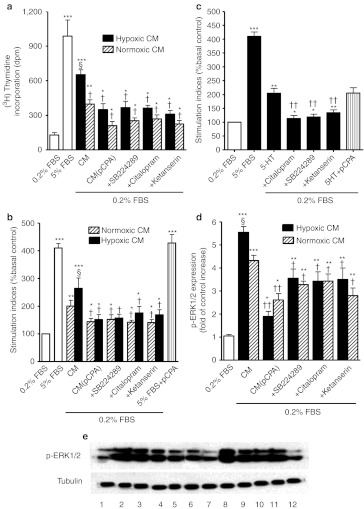

We first assessed the effect of hypoxia on Tph1 and phosphorylated extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 (p-ERK1/2) expression in vitro as dysregulated activation of ERK1/2 is important in the pathophysiology of PAH. hPAECs exposed to hypoxia demonstrated ~50% increase in Tph1 expression compared to normoxia (Figure 1a). This was accompanied by a concomitant increase in p-ERK1/2 (Figure 1b) and markedly increased serotonin levels (4.04 ± 0.83 ng/ml) in the medium of quiescent hypoxic hPAECs compared to normoxic hPAECs (1.23 ± 0.44 ng/ml; P < 0.05). The Tph inhibitor p-CPA did not affect the hypoxia-induced increase in Tph1 or p-ERK1/2 expression (Figure 1a,b). To analyze the contribution of endothelium-derived Tph1 in response to hypoxia on PASMC proliferation, we treated hPAECs with p-CPA under both normoxic and hypoxic conditions. We then exposed cultured bovine PASMCs to the conditioned media from the hPAECs. Conditioned media from normoxic and hypoxic hPAECs stimulated proliferation of the PASMCs with ~3.1-fold and ~5.1-fold increase, respectively in thymidine incorporation from control, basal levels (Figure 2a). This was reduced with media from hPAECs treated with the Tph inhibitor p-PCA (Figure 2a). The conditioned media (normoxic and hypoxic)-induced proliferation observed in the bovine pulmonary arterial smooth muscle cells (bPASMCs) was also significantly attenuated by citalopram (SERT inhibitor) by ~32% and ~44%, respectively, and by SB224289 (5-HT1BR antagonist) by ~36% and ~44%, respectively (Figure 2a,b). The 5-HT2A receptor antagonist ketanserin attenuated normoxic and hypoxic conditioned media-induced proliferation by ~44% and ~52%, respectively (Figure 2a,b). Exogenous serotonin induced a mitogenic effect in the bPASMCs, which was inhibited by pretreatment with citalopram, SB224289, and ketanserin (Figure 2c). p-CPA did not inhibit either fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Figure 2b) or serotonin-induced proliferation (Figure 2c), indicating a lack of nonspecific effects. We chose to use bovine PASMCs for these proof-of-concept studies as these readily proliferate in response to serotonin11 while primary cultures of human PASMCs only respond to serotonin if removed from human PAH patients. These therefore are very difficult to source and inconsistent in their responses.8 As activation of ERK1/2 is important in mediating serotonin-induced proliferation in bPASMCs and dysregulated activation of ERK1/2 is important in the pathophysiology of PAH, we investigated the effects of the hPAEC-conditioned media on the phosphorylation of ERK1/2 in bPASMCs using western blotting. Conditioned media from normoxic hPAECs induced an increase in ERK1/2 phosphorylation in bPASMCs by ~4.2-fold (Figure 2d,e) and ERK1/2 phosphorylation was further increased with conditioned media from hypoxic hPAECs. Selective inhibition of SERT, the 5-HT1BR and the 5-HT2AR with citalopram, SB224289, or ketanserin, respectively resulted in similar inhibitory effects on the phosphorylation of ERK1/2 with conditioned media from both normoxic and hypoxic hPAECs (Figure 2d,e). These results demonstrate that hypoxia induces Tph1 activity in PAECs, increasing serotonin levels. The de novo synthesized serotonin can increase PASMC proliferation via a mechanism dependent on SERT activity and activation of the 5-HT1BR and the 5-HT2AR in a p-ERK1/2-dependent manner. As serotonin can also transactivate the PDGFRβ via SERT in bPASMCs leading to proliferation, we investigated the effects of hPAEC-conditioned media on phosphorylation of PDGFRβ in bPASMCs using western blotting. Although the bPASMCs express PDGFRβ (Figure 3a,b) in agreement with previous studies11 conditioned media from normoxic and hPAECs did not induce PDGFRβ phosphorylation in these cells.

Figure 1.

Effect of hypoxia on expression of tryptophan hydroxylase-1 (Tph1) and phosphorylated extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 (pERK1/2) in human pulmonary artery endothelial cells (hPAECs). (a) Representative western blot and quantitative analysis of Tph1 and (b) representative western blot and quantitative analysis of phosphorylated extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 (p-ERK1/2) expression in hPAECs exposed to normoxic (N) and hypoxic [(H); 5%O2)] conditions in the presence or absence of the Tph inhibitor p-chlorophenylalanine (p-CPA) (10 µmol/l). Tph1 and p-ERK1/2 protein were detected using polyclonal anti-Tph1 and p-ERK1/2 antibodies, respectively, and antibody binding was visualized by a chemiluminescence detection kit. Immunoblot images were scanned and quantified using the TotalLab image analysis software. Tph2 could not be detected in any PAEC samples either under normoxia or hypoxia (data not shown). ***Value significantly greater than corresponding value under normoxic conditions (P < 0.001). Data shown as mean ± SEM of five experiments. Lane numbers on the blot images a and b represent hPAECs treated with the following: (1 and 2) normoxic, (3 and 4) normoxic + p-CPA, (5 and 6) hypoxic, (7 and 8) hypoxic + p-CPA. tERK1/2, total ERK1/2.

Figure 2.

Effect of hypoxia on human pulmonary artery endothelial cell (hPAEC) conditioned media-induced proliferation in bovine pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells (bPASMCs). (a) Quantification of [3H]-thymidine incorporation and (b) cell counts in response to conditioned media (CM) from hPAECs exposed to hypoxia in bPASMCs. Conditioned media was produced in either the absence (CM) or presence (CM(p-CPA)) of the Tph inhibitor p-Chlorophenylalanine (p-CPA) (10 µmol/l). The bPASMCs were stimulated with conditioned media in the absence or presence of the 5-HT1B receptor antagonist (+SB224289, 200 nmol/l), the serotonin transporter (SERT) inhibitor (+citalopram, 10 µmol/l) or the 5-HT2A receptor antagonist (+ketanserin, 1 µmol/l). (c) Cell counts in response to serotonin (1 µmol/l) in bPASMCs and the effect of ketanserin (1 µmol/l), SB224289 (200 nmol/l), citalopram (10 µmol/l), and p-CPA (10 µmol/l). The bPASMCs were treated with the conditioned medium from the hPAECs or serotonin for 48 hours. (d) Quantitative analysis and (e) representative western blot of phosphorylated extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 (p-ERK1/2) expression in bPASMCs in response to conditioned media from hPAECs exposed to normoxic and hypoxic (5%O2) conditions. The bPASMCs were treated with the conditioned medium from the hPAECs for 15 minutes. The increased phosphorylation of ERK1/2 in response to conditioned media was attenuated by p-CPA (10 µmol/l), SB224289 (200 nmol/l), citalopram (10 µmol/l), and ketanserin (1 µmol/l). p-ERK1/2 were detected using polyclonal anti-p-ERK1/2 antibodies and antibody binding was visualized by a chemiluminescence detection kit. Immunoblot images for p-ERK1/2 were scanned and quantified using the TotalLab image analysis software. Antagonists and inhibitors were added for 45 minutes before any treatment. Values are mean ± SEM of three to four experiments. Lane numbers on the image e represent bPASMCs treated with the following: (1) Untreated bPASMCs, (2) normoxic CM, (3) normoxic CM+citalopram, (4) normoxic CM+SB224289, (5) normoxic CM+ketanserin, (6) normoxic CM+p-CPA, (7) Un-treated bPASMCs, (8) hypoxic CM, (9) hypoxic CM+citalopram, (10) hypoxic CM+SB224289, (11) hypoxic CM+ketanserin and (12) hypoxic CM+p-CPA *Value significantly greater than corresponding value under basal conditions (0.2% FBS) (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001) §Value significantly greater than corresponding value in normoxic conditions (§P < 0.05). †Value significantly less than corresponding value in the absence of selective inhibitors and antagonists (†P < 0.05, ††P < 0.01). Data shown as mean ± SEM. FBS, fetal bovine serum.

Figure 3.

Effect of hypoxia on human pulmonary artery endothelial cell (hPAEC) conditioned media-induced phosphorylation of platelet derived growth factor receptor β (PDGFRβ) in bovine pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells (bPASMCs). (a) Quantitative analysis of platelet-derived growth factor receptor β (PDGFRβ) expression in bPASMCs in response to conditioned media (CM) from hPAECs exposed to normoxic and hypoxic (5%O2) conditions and (b) representative western blot. PDGFRβ proteins were detected using polyclonal anti-PDGFRβ antibodies respectively and antibody binding was visualized by a chemiluminescence detection kit. Immunoblot images for PDGFRβ were scanned and quantified using the TotalLab image analysis software. Antagonists and inhibitors were added for 45 minutes before any treatment. Values are mean ± SEM of three to four experiments. Lane numbers on the blot image represent bPASMCs treated with the following: (1 and 10) Untreated bPASMCs, (2) normoxic CM, (3) normoxic CM+p-CPA (4) normoxic CM+citalopram, (5) normoxic CM+p-CPA+ citalopram, (6) hypoxic CM, (7) hypoxic CM+p-CPA (8) hypoxic CM+citalopram, (9) hypoxic CM+citalopram+p-CPA. Data shown as mean ± SEM. CM, conditioned media; p-CPA, p-chlorophenylalanine.

In vivo inhibition of Tph1 using adenoviral vectors

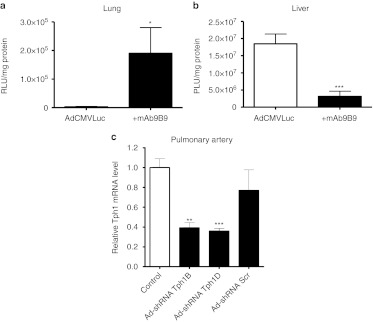

Validation of mAb9B9 pulmonary retargeting. mAb9B9 retargeting of Ad led to ~50-fold increase in pulmonary luciferase expression compared to nontargeted vector(Figure 4a). Concomitantly, luciferase expression in the liver of rats receiving the ACE-targeted Ad was significantly decreased (by ~87%) compared to the nontargeted vector (Figure 4b). Together these results show retargeting of Ad infection via ACE achieved selective gene delivery to the intended target, the lung, in vivo as expected. These results are consistent with previous studies.25,28

Figure 4.

In vivo validation for monoclonal antibody (mAb) 9B9 lung retargeting and for short hairpin RNA (shRNA) sequences against tryptophan hydroxylase-1 (Tph1). (a) In vivo assessment of mAb9B9 (+mAB9B) retargeting in rat lung and (b) in vivo assessment of mAb9B9 (+mAB9B) retargeting in rat liver compared to nontargeted vector (AdCMVLuc). AdCMVLuc alone or complexed to mA9B9 was injected into the tail vein of rats (n = 3 per group). Three days later rats were sacrificed, organs were harvested, and luciferase activity per milligram of protein was determined. (c) Quantitative analysis showing the effect of adenovirus vectors expressing shRNA sequences against Tph1 on the expression of Tph1 mRNA in the pulmonary arteries of normoxic rats 72 hours post-shRNA injection using reverse trancription (RT)-PCR. The Ad-shRNATph1D, Ad-shRNA Tph1B, scrambled sequence Ad-shRNAScr or saline vehicle were injected via the femoral vein under anesthesia. Total RNA was isolated from snap-frozen pulmonary arteries and quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) was performed with Tph1-specific primers; n = 3 per group. *Value significantly less than corresponding value in controls (**P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001). Data shown as mean ± SEM. Ad-shRNA Tph1B, adenoviral–mAb9B9 complex-containing shRNA sequence to Tph1; Ad-shRNA Tph1D, adenoviral–mAb9B9 complex-containing shRNA sequence to Tph1; Ad-shRNA Scr, adenoviral–mAb9B9 complex-containing scrambled sequence.

Validation of shRNA efficiency. Validation of the selectivity of the shRNA sequences is described in see Supplementary Materials and Methods and Supplementary Figure S1. We then determined the efficiency of the shRNA sequences at decreasing Tph1 expression in pulmonary arteries in vivo following cloning into the Ad vector. In vivo, both Ad-shRNATph1B and Ad-shRNATph1D caused a significant decrease (by ~61% and 63%, respectively) in Tph1 mRNA expression in isolated pulmonary arteries following systemic injection of pulmonary endothelium-targeted Ads (Figure 4c), indicating selective targeted knockdown in the pulmonary vasculature. Tph2 could not be detected in any pulmonary artery samples (data not shown). Based on the validation studies we continued the in vivo studies on Tph1 targeting using Ad-shRNATph1D and controls using the 9B9 targeting system.

Effect of Tph1knockdown on indices of PAH. We measured the indices of PAH in normoxic and hypoxic rats receiving Ad-shRNATph1D, saline vehicle, or scrambled sequence (Ad-shRNAScr) using ACE-targeted in vivo adenoviral vector delivery. Under normoxia, injection of shRNA against Tph1 had no effect on systolic right ventricular pressure (sRVP) (Figure 5a), pulmonary vascular remodeling (Figure 5b,d), or right ventricle (RV) hypertrophy (Figure 5c) in the rats when compared to Ad-shRNAScr (scrambled shRNA)-injected controls. Saline was also without effect. Rats receiving Ad-shRNAScr or saline and exposed to 7 days chronic hypoxia developed PAH with a marked increase in sRVP by approximately twofold (Figure 5a), pulmonary vascular remodeling by ~3.5-fold (Figure 5b,d) and RVH by ~0.4-fold (Figure 5c) compared to normoxic animals. In contrast, pretreatment with Ad-shRNATph1D reduced the development of PAH as demonstrated by a 20% decreased sRVP (Figure 5a), a 19% decrease in pulmonary vascular remodeling (Figure 5b,d) and a 12% decrease in RVH (Figure 5c). Systemic arterial pressure (see Supplementary Materials and Methods) was not significantly changed in any group (see Supplementary Table S2). Hypoxia and Tph1 shRNA had no effect on body weight or systemic hemodynamic parameters (see Supplementary Materials and Methods and Supplementary Table S2). These results demonstrate that selective Tph1 inhibition in vivo by targeted adenoviral vectors is effective at reducing hypoxia-induced PAH.

Figure 5.

Effects of tryptophan hydroxylase-1 (Tph1) short hairpin RNA (shRNA), scrambled sequence, and vehicle control on indices of pulmonary hypertension in the chronic hypoxic rat pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) model. At 7 days after exposure to chronic hypobaric hypoxia or normoxia, a hemodynamic study was performed in anesthetized rats to measure systolic right ventricular pressure (sRVP). The Ad-shRNATph1D, scrambled sequence Ad-shRNAScr, or saline vehicle were injected via the femoral vein under anesthesia and full recovery from surgery allowed before exposure to hypoxia/normoxia. Graphs show the effects of Ad-shRNA Tph1D, and the scrambled sequence Ad-shRHA Scr on (a) sRVP (n = 6–9 rats per group), (b) pulmonary vascular remodeling (n = 4–5 per group), and (c) right ventricular hypertrophy (RVH) in normoxic (open square) and 7-day hypoxic (closed square) rats (n = 6–9 rats). (d) Representative photomicrographs showing the effects of Ad-shRNA Tph1D and Ad-shRNA Scr on hypoxia-induced remodeling in small pulmonary arteries from normoxic and hypoxic rats. Note the readily identifiable double elastic lamina (black arrow) and newly formed smooth muscle layer (white asterisk) in the hypoxic group. Bars = 50 µm. *Value significantly greater than corresponding value in normoxic vehicle control rats (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001). †Value significantly less than corresponding value in vehicle-treated rats (†P < 0.05, ††P < 0.01). ‡Value significantly less than corresponding value in Ad-shRNAScr-treated rats (‡P < 0.05, ‡‡P < 0.01). Data shown as mean ± SEM. Ad-shRNA Tph1D, adenoviral–mAb9B9 complex-containing shRNA sequence to Tph1; Ad-shRNA Scr, adenoviral–mAb9B9 complex-containing scrambled sequence. mAb, monoclonal antibody.

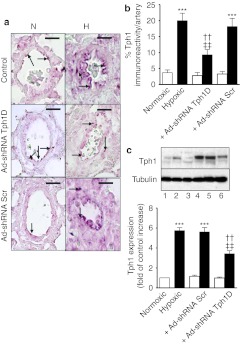

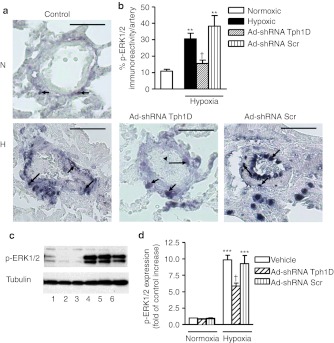

Effect of Tph1 knockdown on expression of Tph1, PCNA, and p-ERK1/2

Minimal Tph1 expression was observed in normoxic, control pulmonary arteries (Figure 6a,b) and lungs (Figure 6c). Seven days hypoxia markedly increased endothelial Tph1 expression in the pulmonary arteries (Figure 6a,b) and lungs (Figure 6c) with some Tph1 expression also observed in other pulmonary arterial cell types (Figure 6a). Ad-shRNATph1D significantly decreased Tph1 expression in hypoxia while Ad-shRNAScr was without effect (Figure 6a–c). We evaluated the effect of Tph1 knockdown on pulmonary vascular cell proliferation using immunohistochemistry and western blotting to detect the proliferating cell marker proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA). Normoxic rat lungs demonstrated minimal PCNA staining and expression (Figure 7a–d). Hypoxic exposure increased expression of PCNA ~3.5-fold in the pulmonary arteries where proliferating cells were detected throughout the pulmonary artery cell layers (Figure 7a,b) and in the lungs (Figure 7c,d). Ad-shRNATph1D, but not Ad-shRNAScr, significantly decreased PCNA expression by ~40%. We also investigated the effects of chronic hypoxia and Tph1 knockdown on p-ERK1/2 in the rat lungs. The pulmonary arteries of hypoxic vehicle-treated rats had significantly increased levels (by approximately threefold) of p-ERK1/2 (Figure 8a,b) compared to normoxic counterparts. Furthermore, Ad-shRNATph1D attenuated the hypoxia-induced increase in p-ERK1/2 by ~42% (Figure 8a,b). The lungs of hypoxic vehicle-treated rats also had significantly increased levels of p-ERK1/2 (Figure 8c,d), compared to normoxic counterparts, which were attenuated by Ad-shRNATph1D (Figure 8c,d). Neither chronic hypoxia nor Ad-shRNATph1D treatment had any effect on the Tph1 and p-ERK1/2 expression observed in rat aorta (see Supplementary Materials and Methods and Supplementary Figure S2a–c). PCNA expression was also unaffected by chronic hypoxia or Ad-shRNATph1D treatment (Supplementary Figure S2a,d). These results indicate that both selective targeted knockdown of Tph1 and the effects of chronic hypoxia were confined to the pulmonary vasculature.

Figure 6.

Evaluation of the efficiency of tryptophan hydroxylase-1 (Tph1) short hairpin RNA (shRNA) treatment in hypoxia-induced pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH). (a) Representative photomicrographs and (b) quantitative analysis showing the effects of chronic hypoxia, Tph1 shRNA and scrambled sequence on expression of Tph1 in the pulmonary arteries of 7-day hypoxic (H) rats (closed square; n = 4 rats) compared to normoxic (N) controls (open square; n = 3 rats). (c) Western blot and quantitative analysis showing the effects of chronic hypoxia, Tph1 shRNA and scrambled sequence on expression of Tph1 in the lungs of 7-day hypoxic rats compared to normoxic controls. Tph1 protein was detected using a polyclonal anti-Tph1 antibody, and antibody binding was visualized by a chemiluminescence detection kit. Immunoblot images were scanned and quantified using the TotalLab image analysis software. Immunohistochemistry image analysis was performed on images of lung tissue sections using Metamorph software. *Value significantly greater than corresponding value in normoxic vehicle control rats (***P < 0.001). †Value significantly less than corresponding value in vehicle-treated rats (††P < 0.01). ‡Value significantly less than corresponding value in Ad-shRNAScr-treated rats (‡‡P < 0.01). Data shown as mean ± SEM. Arrows highlight examples of expression of Tph1 in rat pulmonary arteries. Lane numbers on the blot in image c represent: (1) normoxic vehicle-treated, (2) normoxic Ad-shRNA Scr-treated, (3) normoxic Ad-shRNA Tph1D-treated (4) hypoxic vehicle-treated, (5) hypoxic Ad-shRNA Scr-treated, and (6) hypoxic Ad-shRNA Tph1D-treated rats. N, normoxia; H, hypoxia. Ad-shRNA Tph1D, adenoviral–mAb9B9 complex-containing shRNA sequence to Tph1; Ad-shRNA Scr, adenoviral–mAb9B9 complex-containing scrambled sequence; Tph1, tryptophan hydroxylase-1. Bars are 25 µm. mAb, monoclonal antibody.

Figure 7.

Effects of tryptophan hydroxylase-1 (Tph1) short hairpin RNA (shRNA), scrambled sequence, and vehicle control on proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA) expression in chronic hypoxic rat pulmonary arteries and lungs. (a) Representative photomicrograph and (b) quantitative analysis showing the effects of chronic hypoxia, Tph1 shRNA and scrambled sequence on expression of proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA) in rat small pulmonary arteries where expression of PNCA is shown as black staining. (c) western blot and (d) quantitative analysis showing the effects of chronic hypoxia, Tph1 shRNA and scrambled sequence on expression of PCNA in lungs from (n = 4–5) rats. PCNA protein was detected using a polyclonal anti-PCNA antibody, and antibody binding was visualized by a chemiluminescence detection kit. Immunoblot images were scanned and quantified using the TotalLab image analysis software. Immunohistochemistry image analysis was performed on images of lung tissue sections using Metamorph software. *Value significantly greater than corresponding value in normoxic rats (**P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001). †Value significantly less than corresponding value in vehicle-treated control rats (†P < 0.05). Data shown as mean ± SEM of 4–8 vessels analyzed. Arrows highlight examples of expression of PCNA. Lane numbers on the image c represent: (1) normoxic vehicle-treated, (2) normoxic Ad-shRNA Scr-treated, (3) normoxic Ad-shRNA Tph1D-treated (4) hypoxic vehicle-treated, (5) hypoxic Ad-shRNA Scr-treated, and (6) hypoxic Ad-shRNA Tph1D-treated rats. N = normoxia; H = hypoxia Ad-shRNATph1D, adenoviral–mAb9B9 complex-containing shRNA sequence to Tph1; Ad-shRNAScr, adenoviral–mAb9B9 complex-containing scrambled sequence. Bars are 50 µm. mAb, monoclonal antibody.

Figure 8.

Effects of tryptophan hydroxylase-1 (Tph1) short hairpin RNA (shRNA), scrambled sequence and vehicle control on phosphorylated extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 (p-ERK1/2) expression in chronic hypoxic rat lungs. (a) Representative photomicrograph and (b) quantitative analysis showing the effects of chronic hypoxia, Tph1 shRNA and scrambled sequence on expression of phosphorylated extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 (p-ERK1/2) in rat small pulmonary arteries where expression of p-ERK1/2 is shown as black staining. (c) Western blot and (d) quantitative analysis showing the effects of chronic hypoxia, Tph1 shRNA and scrambled sequence on expression of p-ERK1/2 in lungs from (n = 4–5) rats. p-ERK1/2 protein was detected using a polyclonal anti-p-ERK1/2 antibody, and antibody binding was visualized by a chemiluminescence detection kit. Immunoblot images were scanned and quantified using the TotalLab image analysis software. Immunohistochemistry image analysis was performed on images of lung tissue sections using Metamorph software *Value significantly greater than corresponding value in normoxic rats (**P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001). †Value significantly less than corresponding value in vehicle-treated control rats (†P < 0.05). Data shown as mean ± SEM of 4–8 vessels analyzed. Arrows highlight examples of expression of p-ERK1/2. Lane numbers on the image c represent: (1) normoxic vehicle-treated, (2) normoxic Ad-shRNA Scr-treated, (3) normoxic Ad-shRNA Tph1D-treated (4) hypoxic vehicle-treated, (5) hypoxic Ad-shRNA Scr-treated, and (6) hypoxic Ad-shRNA Tph1D-treated rats. N = normoxia; H = hypoxia Ad-shRNATph1D, adenoviral–mAb9B9 complex-containing shRNA sequence to Tph1; Ad-shRNAScr, adenoviral–mAb9B9 complex-containing scrambled sequence. Bars are 50 µm. mAb, monoclonal antibody.

Discussion

For the first time, we demonstrate that a targeted gene therapy approach to inhibit pulmonary Tph1 is effective at preventing hypoxia-induced PAH. Hypoxia can increase serotonin synthesis via Tph1 in PAECs both in vitro and in vivo and our results suggest this contributes to the development of hypoxia-induced PAH in rats.

The importance of serotonin in the pathobiology of PAH is well documented and, the 5-HT1BR3 the SERT,4 and de novo synthesized serotonin5,6 have all been associated with development of PAH. Pharmacological inhibition and genetic knockout of these targets have been investigated showing attenuation of the development of PAH. For example, previous studies using rat models of PAH have shown that inhibition of the 5-HT1BR either fails to attenuate PAH (monocrotaline rat)29 or attenuates chronic hypoxia-induced PAH to a modest degree (hypoxic rat).3 SERT inhibitors do not increase survival in patients with PAH.30 Experimentally, hypoxia-induced elevations in indices of PAH are modestly reduced in SERT knockout mice.31 Combined SERT and 5-HT1BR inhibition is more effective than SERT inhibition alone at both preventing and reversing the indices of PAH in mice,8 However, there is still room for improvement in therapeutic effect. Targeting serotonin synthesis “at source” in the microenvironment of the pulmonary vasculature is an attractive novel approach in this context. Nonselective inhibition of Tph (Tph1 and Tph2) has previously been shown to attenuate the development of PAH in rodents.16 The use of more selective inhibitors against Tph1, limiting inhibition of serotonin synthesis to the periphery by not crossing the blood–brain barrier, however, would be advantageous. Indeed, small molecule inhibitors with selectivity for Tph1, and minimal effect on brain serotonin levels are currently being investigated as potential therapies in the treatment of osteoporosis22 and irritable bowel syndrome.32 While Tph1 inhibitors are under development33 our targeted approach has many advantages over ubiquitous inhibition of Tph1. Serotonin is involved in vasoconstriction, haemostasis, and the control of immune responses.19,20 Moreover, serotonin is a precursor for melatonin21 and Tph1 deficiency is also related to increased bone mass.22 Our approach, being selective to local endothelial-derived serotonin would avoid the potential side effects that ubiquitous Tph1 inhibition would confer.

Pathologically, hPAECs express Tph16 and Tph1 gene expression is increased in the lungs and the PAECs of remodeled pulmonary arteries from patients with idiopathic PAH.6 However, the effects of hypoxia on PAEC-Tph1 activity have not been determined. Therefore, our first aim was to investigate the effects of hypoxia on serotonin synthesis and release by PAECs in vitro. To this end, we added serum-free media from hPAECs cultured in hypoxic and normoxic conditions to bPASMCs. Normoxic, quiescent, hPAEC media contained serotonin and stimulated bPASMC proliferation. This suggests that hPAECs can constitutively synthesize and release mitogenic factors including serotonin that can cause proliferation in pulmonary vascular cells. This is consistent with previous studies demonstrating proliferation of hPASMCs following application of PAEC conditioned media.6 In the present study, citalopram, SB224289, and ketanserin, inhibitors of the SERT, the 5-HT1BR and the 5-HT2AR, respectively, all attenuated the normoxic media-induced proliferation of bPASMCs by ~32, 36, and 44%, respectively. The hypoxic PAEC-conditioned media contained increased levels of serotonin. Collectively, this demonstrates that serotonin is being released by PAECs consistent with our hypothesis. Here, we demonstrate for the first time that hypoxia increases Tph1 levels in hPAECs, and that conditioned media from these hypoxic cells induced bPASMC proliferation to a greater extent than was observed with media from normoxic hPAECs. Hypoxia also increased hPAEC p-ERK1/2 expression, consistent with the role of the ERK pathway in activating Tph1 synthesis.34 Hypoxic hPAEC media-induced proliferation in bPASMCs was also significantly inhibited by citalopram, SB224289 and ketanserin, confirming serotonin as the mitogenic factor released. This is consistent with previous studies demonstrating the involvement of SERT, the 5-HT1BR and the 5-HT2AR in mediating serotonin-induced proliferation in bPASMCs.35,36 This is also confirmed by our demonstration that pretreatment of hPAEC with the selective Tph inhibitor p-CPA also reduced bPASMC proliferation to levels similar to those with media from normoxic hPAECs. P-CPA did not affect the hypoxia-induced increase in Tph1 and p-ERK expression in hPAECs, suggesting any subsequent effect on bPASMC proliferation was by inhibition of Tph activity. Neither selective SERT, 5-HT1BR and 5-HT2AR inhibition or Tph1 inhibition completely prevented the conditioned media-induced proliferation in the bPASMCs suggesting the co-involvement of other mitogenic factors, along with serotonin, released from the PAECs. Recent studies, for example, have implicated the involvement of fibroblast growth factor-2,37 reflecting the complex and multifactorial pathobiology of PAH.

As serotonin mediates proliferation of bPASMCs in an ERK1/2-dependent manner,35 we investigated the effects of conditioned media from hPAECs cultured in hypoxic and normoxic conditions on p-ERK1/2 expression in bPASMCs. Hypoxic and normoxic hPAEC media-induced phosphorylation of ERK1/2; this was significantly inhibited by citalopram, SB224289, and ketanserin. These results further confirm the involvement of serotonin as the mitogenic factor released from the PAECs. Previous studies have shown that serotonin (at µmol/l concentrations) can stimulate proliferation of bPASMCs through transactivation of the PDGFRβ through phosphorylation of PDGFRβ.11 However, as both hypoxic and normoxic hPAEC media contain only nmol/l amounts of serotonin, neither induced phosphorylation of PDGFRβ. It is unlikely that such low serotonin concentrations are able to transactivate the PDGFRβ.

We next wished to challenge our hypothesis that PAEC production of serotonin contributes to experimental hypoxia-induced PAH. To assess this we used lung-targeted delivery of Ad25 to selectively knockdown Tph1 by shRNA in the pulmonary vasculature. Using this very unique approach we disrupted the function of the serotonin synthesis enzyme by depleting endogenous Tph1 in PAECs in vivo. RNA expression studies confirmed that the Tph1 targeted shRNA sequences were successful in knocking down Tph1 in vitro in two rat cell lines expressing Tph1, including endothelial cells, and in vivo. As the indices of hypoxia-induced PAH were significantly attenuated in the rats receiving the shRNA against Tph1, this confirms that specific knockdown of Tph1 in rat PAECs was sufficient to reduce the development of hypoxia-induced PAH. Moreover, this confirms that chronic hypoxia mediates the development of PAH, in part, via serotonin synthesis within PAECs.

The profile of luciferase expression is consistent with previous studies25,28 showing that conjugating Ad with mAb9B9 resulted in marked retargeting of the Ad to the lungs. The detailed previous studies clearly show pulmonary retargeting using the mAb9B9 conjugate is dependent on the ACE-targeting properties of this reagent and the selectivity of ACE targeting for the pulmonary vascular bed.25 Furthermore, gene expression studies and immunohistochemistry confirmed selective localization to the pulmonary vascular endothelium.25

Immunohistochemistry and western blotting confirmed the level of Tph1 protein in pulmonary arteries and lungs was significantly elevated following 7 days of hypoxia and that this increase was attenuated in the group treated with shRNA against Tph1, thus validating our targeted gene therapy approach. Tph1 immunostaining is confined to pulmonary endothelial cells in patients with idiopathic PAH.6 However, in most species, perivascular mast cells and other parenchymal cells also contain serotonin.38 It is known that hypoxia can increase degranulation of mast cells.39 While Tph1 expression was most marked in PAECs, hypoxia also induced increased Tph1 expression in these perivascular cells. The PAEC-selective nature of our gene therapy targeting strategy will limit Tph1 knockdown to the PAECs. It is unclear to what extent serotonin released from perivascular cells would contribute to pulmonary vascular remodeling, however, our data support the concept that PAEC-Tph1-selective knockdown is still an effective strategy in attenuating the development of hypoxia-induced PAH. Other rat arteries including the aorta are known to express Tph1.14 In contrast to the pulmonary arteries, Tph1 protein expression in the aorta was unaffected by hypoxia and shRNA against Tph1. This confirms that specific knockdown of Tph1 was confined to the pulmonary vasculature. There was a pulmonary selective increase in PCNA-positive cells, which was attenuated in rats treated with shRNA against Tph1. This suggests that hypoxia-induced pulmonary vascular remodeling via serotonin-induced proliferation within the pulmonary vascular walls. This is consistent with our previous observation that hypoxia-induced PAH is ablated in Tph1 knockout mice.5 We observed a 20, 19 and 12% decrease in sRVP, pulmonary vascular remodeling and RVH, respectively. This was in the knowledge that the Ad targeting strategy achieved a 63% reduction in lung Tph1. Whilst this reduction is moderate, these experiments prove our concept and justify further research into the therapeutic potential of this approach especially as the prognosis in PAH remains extremely poor.

The incidence of PAH is higher in females, although mortality is greater in males.40 We have recently shown that 17β oestradiol can up regulate Tph141 and can facilitate the PAH phenotype observed in female mice overexpressing the SERT.41 Hence Tph1 activity may also play a role in the influence of gender in the development of PAH. One further limitation of our study was that it was a preventative study. Future studies should examine the effectiveness of this strategy in reversing PAH and also the effectiveness of the strategy in female rats.

This study shows for the first time that Tph1 knockdown inhibits hypoxia-induced p-ERK1/2 in vivo. Acute and chronic hypoxia increases ERK1/2 activation in rat pulmonary arteries.42 Activation of the Raf-1/mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase 1/2(MEK)/ERK1/2 signal transduction pathway leading to ERK1/2 phosphorylation plays an important role in the induction of PASMC proliferation by serotonin35 and hypoxia-induced p-ERK1/2 occurs in human PASMCs.42

Our in vivo studies support our hypothesis that hypoxia induces serotonin synthesis by PAECs, which then acts on underlying cells in a paracrine fashion.

One hurdle for the clinical application of gene/gene knockdown delivery-based approaches is achieving cell-specific targeting.43 ACE is highly expressed in PAECs compared to the vasculature of other organs of rats23 and humans.23 As ACE is upregulated in remodeled vessels of rat44 and human45 lung, it could be a useful target for therapeutic agents directed toward the PAECs in the context of established PAH. The mAb 9B9-anti-knob conjugate used has affinity for both ACE and the Ad capsid.25 Improved specificity and stability by developing antibody fragments of mAb 9B9 that specifically recognize rat, hamster, and human ACE is currently being investigated.46

In conclusion, we have shown for the first time that hypoxia induces Tph1 activity in PAECs and that this contributes to the development of hypoxia-induced PAH. With continued advances in in vivo cell-specific targeting and refinements in vector delivery technology, selectively targeting pulmonary endothelial synthesis of serotonin through inhibition of Tph1 in the pulmonary vascular endothelium may be an attractive therapeutic strategy for the treatment of PAH.

Materials and Methods

In vivo experiments. All animal studies conform with institutional regulations at the University of Glasgow, the United Kingdom Animal Procedures Act, 1986, and with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals published by the National Institutes of Health (NIH publication No. 85-23, revised 1996).

Effects of PAEC conditioned media on proliferation of bovine PASMCs

Culture of hPAECs. All human studies were approved by the research ethics board of the University of Glasgow and conform to the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. Human PAECs were cultured according to the manufacturer's instructions in Medium 200 (Invitrogen, Paisley, UK) supplemented with low serum growth supplement (Invitrogen) until 60–70% confluent then incubated in serum-free medium for 24 hours. Cells were then incubated for a further 24 hours in either normoxic or hypoxic (5% O2) conditions in serum-free media in the presence/absence of the Tph inhibitor p-CPA (10 µmol/l; Tocris, Bristol, UK). The resultant “conditioned media” was then collected for proliferation studies in bovine PASMCs and for measurement of serotonin concentration.

Measurement of serotonin production by hPAECs. Serotonin concentration was measured in the hPAEC culture conditioned medium using a serotonin ELISA kit (Genway Biotech, San Diego, CA) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Proliferation of bPASMCs

Culture of bovine PASMCs. Bovine PASMCs were used. PASMCs play an important role in pulmonary vascular remodeling associated with PAH,1 and respond consistently to serotonin11 whereas normal hPASMCs do not.8 Furthermore, PASMCs are in the direct environs of the PAECs and subject to direct influence of vasoactive factors released from the PAECs in hypoxia and/or PAH. Freshly excised bovine lung was obtained from the local abattoir. Lobar pulmonary arteries were dissected free and rinsed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (37 °C) containing antibiotics penicillin/streptomycin (200 IU/ml and 200 µg/ml; Invitrogen) and cut open longitudinally on a sterile Petri dish. The luminal side of the vessel was scraped with a scalpel to remove endothelial cells and PASMCs were prepared as previously described,47 with some modifications after removal of muscular tissue by gentle abrasion. bPASMCs were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (Sigma, Dorset, UK) containing 10% FBS (Sigma) supplemented with penicillin/streptomycin (200 IU/ml/200 µg/ml; Invitrogen) and L-glutamine (27 mg/ml; Invitrogen) and used between passages 3 to 10.

bPASMC proliferation assessment by [3H-]thymidine incorporation. bPASMCs in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium supplemented with 10% FBS were seeded in 24 well plates at a density of 2 × 104 cells/well and allowed to adhere and grow to ~60% confluency. The cells were subjected to 48 hours of growth arrest in 0.2% FBS medium, and then treated with 1 ml of conditioned medium from the hPAECs for 48 hours. In conjunction, we also examined the effect of exogenous serotonin (1 µmol/l; Sigma), as well as conditioned media, on bPASMC proliferation in the presence/absence of 1′-methyl-5-[[2′-methyl-4′-(5-methyl-1,2,4-oxadiazol-3-yl)biphenyl-4-yl]carbonyl]-2,3,6,7-tetrahydrospiro[furo[2,3-f]indole-3,4′-piperidine hydrochloride [SB224289 (200 nmol/l; selective 5-HT1B antagonist; Tocris], citalopram (10 µmol/l; SERT inhibitor; Tocris), and ketanserin (1 µmol/l; 5-HT2A antagonist, Tocris). Under each condition, [3H]-thymidine (0.5 µCi/ml; Perkin Elmer, Cambridge, UK) was added to each well 24 hours before the end of each experiment. Cells were washed with cold PBS twice, washed a third time with cold 5% trichloroacetic acid, and lysed with 0.5 mol/l NaOH. The radioactivity was measured in a liquid scintillation counter. Counts were measured in disintegrations per minute.

bPASMC proliferation assessment by cell counts. bPASMCs were grown to 60% confluency in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium as above. The cells were subjected to 48 hours of growth arrest in 0.2% FBS medium. The effect of exogenous serotonin on bPASMC proliferation in the presence/absence of selective serotonin receptor antagonists and SERT inhibitor was examined as above. Cell counts were performed in a blinded fashion using ahaemocytometer (n = 3–4 for each experiment and performed in duplicate).

hPAEC-conditioned media effect on the phosphorylation of ERK1/2 and PDGFRβ. As activation of ERK1/2 is important in mediating serotonin-induced proliferation in bPASMCs and dysregulated activation of ERK1/2 is important in the pathophysiology of PAH, and as serotonin can transactivate the PDGFRβ, via SERT we investigated the effects of the hPAEC-conditioned media on the phosphorylation of ERK1/2 and PDGFRβ, in bPASMCs using western blotting.

In vivo inhibition of Tph1 using adenoviral (Ad) vectors

Cloning strategy. Overlapping oligonucleotides encoding for a shRNA against Tph1 or a scramble sequence (see Supplementary Table S1 for sequences used) and containing a Mlu1 site at the 5′ and a Cla1 site at the 3′ were annealed and cloned into the unique Mlu1 and Cla1 sites in pLVTHM in order to express the transgenic sequences under the H1 promoter and to generate pLVTHM-shTph1 (LV-shRNA Tph1B and LV-shRNA Tph1D) and pLVTHM-scramble (LV-shRNA Scr) vectors, respectively. Clones were verified by sequence analysis.

LV vectors production, infection, and in vitro validation. Lentiviral (LV) vectors were produced by triple transient transfection of HEK293T cells with a packaging plasmid (pCMVΔ8.74), a plasmid encoding the envelope of vesicular stomatitis virus (Plasmid Factory, Bielefeld, Germany) and PLVTHM-shTPH1 or PLVTHM-scramble, as previously described.48 For infection, 2 × 104 RBL-2H3 cells (rat basophilic leukemic cell line which expresses both Tph1 and Tph2)49 and RGE cells (rat renal endothelial cell line which expresses Tph1) were transduced with lentivirus vectors expressing Tph1 specific shRNA (B and D) or a scrambled control (Scr) with a multiplicity of infection ratio (MOI) of 50. Cells were incubated in complete media (Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium) containing heat-inactivated FBS (15%), (Invitrogen) containing LV particles and 4 µg/ml Polybrene (Sigma) for 3 hours at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2. LV particles were removed and media was replaced with fresh complete media for an additional 72 hours to permit cell recovery and the expression of the transgenic sequence. After 72 hours total RNA was extracted for assessing Tph1 expression.

Total RNA extraction from cells. Total RNA from cells was obtained using the RNeasy kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) following the manufacturer's instructions treated with the DNAse 1, amplification grade (Sigma, St Louis, MO), to eliminate the genome DNA contamination and quantified using the NanoDrop ND-1000 Spectrophotometer (Nano-Drop Technologies, Wilmington, DE). Absorbance of the RNA samples was quantified at 260 and 280 nm, and the 260/280 ratio was calculated. The samples showed a 260/280 ratio ≥1.9, which was assumed as an indicator of RNA purity. cDNA was synthesized from total RNA using the SuperScript II Reverse Transcriptase (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Each reaction contained 1 mg of extracted total RNA, 4 µl of 5X SuperScript II buffer, 200 U of SuperScript II RT, 3 µg of random hexamer primers (Invitrogen), 20 U of RNase inhibitor (Promega, Madison, WI) and 1 µl of deoxyribonucleotide triphosphates mixture (10 mmol/l). The 20 µl reactions were incubated in a 96-well plate for 10 minutes at 25 °C, 30 minutes at 48 °C, 5 minutes at 95 °C and then stored at –20 °C.

Production of adenoviral (Ad) vectors. The three shRNA sequences [sequences B, D, Scr (see Supplementary Table S1 for shRNA against Tph1 and scrambled sequences)] were cloned into pAdEasy (Agilent Technologies, Böblingen, Germany) plasmid and recombinant E1/E3 deleted replication-deficient Ad5 vectors were produced in HEK293 cells. A recombinant E1-, E3-deleted Ad vector expressing firefly luciferase under the control of the cytomegalovirus (CMV) promoter [AdCMVLuc] was produced and also propagated in HEK293 cells. Viruses were purified by CsCl gradient centrifugation. Particle and infectious titers were calculated and silver staining was performed for quality control as described.50

In vivo inhibition of Tph1 using adenoviral vectors

Validation of mAb 9B9 pulmonary retargeting in rats. Following systemic injection, mAb 9B9 with high affinity to ACE demonstrates selective accumulation in rat, hamster,23 and primates, including human,24 lung tissue. mAb 9B9 can target therapeutic agents/genes to the pulmonary vascular endothelium following systemic administration creating a pulmonary endothelium-targeted therapeutic gene delivery system.25 Therefore to target the Ad to the lung endothelium we used the bispecific mAb9B9 antibody-anti-knob conjugate, which binds to the fibre protein in the Ad capsid and to the pulmonary endothelial marker ACE.25,26 To assess pulmonary retargeting of Ad, AdCMVLuc was complexed with mAb9B9 for 30 minutes at room temperature, then total volume was brought to 200 µl with sterile normal saline. Rats were injected (tail vein), then sacrificed 3 days later. Lungs and liver were harvested and snap frozen in ethanol/dry ice. For luciferase assay, lungs and liver were ground to powder and cooled in an ethanol/dry ice bath. One hundred milligrams of organ powder were weighed and placed in a 1.5-ml polypropylene tube. Processing for luciferase activity was performed (Promega luciferase assay system kit). Tissue powders were lysed in cell lysis buffer and subjected to multiple freeze thaw cycles to ensure complete lysis. Tubes were centrifuged and supernatant analyzed for luciferase activity according to the manufacturer's instructions. The protein concentration of lysate was determined using a Bio-Rad protein assay kit, according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Validation of shRNA efficiency in producing Tph1 knockdown in lungs from normoxic rats. To assess the effect of shRNA targeting Tph1 in vivo, under 2.5% isoflurane anesthesia, male Wistar rats (7 weeks old; n = 3 rats per group) were injected intravenously (femoral vein) with the adenoviral mAb9B9-anti-knob complex containing either Ad-shRNA sequences to Tph1 (Ad-shRNA Tph1B and Ad-shRNA Tph1D) or the scrambled sequence (Ad-shRNA Scr). Animals received 4 × 1011vp/kg (~1 × 1011vp/rat) of Ad5-expressing shRNA preincubated with 9B9 antibody (5 µg/1 × 1011 vp Ad). A control group was infused with vehicle (PBS (Sigma)). Animals were sacrificed 72 hours after injection, pulmonary arteries were removed, the RNA extracted, and the Tph1 and Tph2 mRNA levels assayed using quantitative real-time PCR. mRNA levels were normalized to β-actin expression.

TaqMan quantitative real-time PCR analysis of Tph1 mRNA expression. For the q-PCR, reactions were incubated in a 386-well optical plate at 95 °C for 10 minutes; following by 40 cycles of 95 °C for 15 seconds and 60 °C for 1 minute. Results were normalized to GAPDH (cells) or β-actin expression (pulmonary arteries). The fold change for Tph1 expression was obtained. The samples were run in triplicate and results were presented as the mean ± SD. To assess the statistical significance of intergroup differences, a Student's t-test was performed.

Adenoviral-antibody complex infusion. Under 2.5% isoflurane anesthesia, male Wistar rats (7 weeks old; n = 9 rats per group) were injected with the adenoviral-mAb9B9-anti-knob complex containing either Ad-shRNA Tph1D or the scrambled sequence (Ad-shRNA Scr) as above. The rats were allowed to fully recover for wound healing prior to exposure to chronic hypoxia or normoxia for 7 days.

Exposure to hypoxia. Rats receiving either adenoviral vector or vehicle were subsequently maintained in normoxic conditions or hypobaric/hypoxic conditions for 7 days as previously described.5 The hypobaric chamber was depressurized over the course of 2 days to 550 mbar (equivalent to 10% O2). Temperature was maintained at 21 °C to 22 °C, and the chamber was ventilated with air at 45 l/min.

Characterization of PAH

Pressure measurements. The RV was catheterized through the right external jugular vein and right atria using a 3-French catheter.3 The catheter position within the RV was confirmed by the morphology of the pressure trace. Basal sRVP and systemic blood pressures were made after a period of stabilization using a Biopac pressure transducer (BIOPAC Systems, Goleta, CA) connected to an MP35 data acquisition system (BIOPAC Systems). Systemic blood pressure was monitored through a cannula inserted into the ascending aorta via the right carotid artery. Heart rate was derived from the pressure traces. Results were analyzed using the built-in software package.

Indices of pulmonary hypertension. The ratio of right ventricular weight to left ventricular weight plus septum (RV/[LV + S]) was used as an index of right ventricular hypertrophy (RVH).5 Sagittal sections were obtained from left lungs, stained with Elastica Van Gieson stain and microscopically assessed for muscularization of pulmonary arteries (<80-µm external diameter). The percentage of remodeled vessels (<80 µm in diameter) was assessed by measuring vessels with a double elastic lamina and expressing this as a percentage of vessels examined.5 Lung sections from four rats from each group were studied.

Immunohistochemistry. To determine cell proliferation in the pulmonary arteries, lung sections were stained for PCNA, an antigen that is expressed in cell nuclei during the DNA synthesis phase of the cell cycle. Immunohistochemistry was performed in each group to identify any changes in expression of Tph1, PCNA and the Raf-1/mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) kinase 1/2 (MEK1/2)/extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 (ERK1/2), (Raf-1/MEK/ERK1/2) signaling element p-ERK1/2 in response to chronic hypoxia and knockdown of Tph1. Paraffin sections (5-µm thickness) were mounted on poly-L-lysine slides. Slides were dewaxed in Histoclear, and sections were rehydrated by ethanol immersion (100, 95, and 70%) and then in distilled water. Antigen retrieval was carried out by microwaving in 10 mmol/l citric acid buffer, pH 6.0. Endogenous peroxidase activity was blocked using 3% H2O2 in methanol for 30 minutes. After two washes in PBS, the sections were preincubated in PBS supplemented with 0.5% bovine serum albumin, 10% normal horse serum for 1 hour. Sections were incubated overnight with rabbit polyclonal anti-Tph1 (Millipore, Waterford, UK), anti-phospho-ERK1/2 (New England Biolabs, Hitchin, UK) or anti-PCNA (Abcam, Cambridge, UK) antibodies which were diluted 1:200, 1:50, or 1:100, respectively in PBS containing 10% bovine serum albumin, 15% normal goat serum. The sections were exposed for 1 hour to horse radish peroxidase-polymer secondary antibodies (Vector Laboratories, Peterborough, UK). Peroxidase staining was carried out using Vector 3′3′-diaminobenzidine tetrahydrochloride dihydrate substrate staining kits (Vector Laboratories) with enhanced nickel staining for PCNA and p-ERK1/2 staining. This is the optimum staining technique for visualising PCNA and p-ERK1/2 expression in lung sections, areas of PCNA and p-ERK1/2 staining appearing as a black coloration. For optimal visualization of Tph1 staining, peroxidase staining was carried out using a Vector VIP substrate kit (Vector Laboratories) with areas of Tph1 staining appearing as a purple/pink coloration. Immunohistochemistry image analysis was performed on ×40 magnification images of lung tissue sections using Metamorph software (version 6.1; Molecular Devices, Downington, PA). The average pixel intensity of each image correlated to a grey scale range of 0 (black) to 255 (white), with intermediate intensities being assigned an appropriate grey level. The vessel wall of small pulmonary arteries within the lung sections was selected and specifically analyzed. In order to determine Tph1, PCNA, and p-ERK1/2 immunoreactivity the color threshold was set to detect pixel intensity between 0–125, 0–137, and 0–150, respectively. The percentage threshold area detected was then expressed as the percentage of Tph1, PCNA, or p-ERK1/2 immunoreactivity within the vessel. 3–4 sections per experimental group were analyzed and the results expressed as mean ± SEM.

Western blotting. Tph1 expression was evaluated in RBL2H3 cells; Tph1 and p-ERK1/2 expression was evaluated in hPAECs, PDGFRβ, p-PDGFRβ, and p-ERK1/2 expression was evaluated in bPASMCs, and Tph1, PCNA and p-ERK1/2 expression was evaluated in rat lung and aorta by western blot analysis on equal amounts of protein extracts resolved by fractionation by gel electrophoresis on 4–12% (wt/vol) Nupage Novex Bis–Tris resolving gels (Invitrogen). Immunoblot images were scanned and quantified using the TotalLab (Nonlinear Dynamics, Newcastle-Upon-Tyne, UK) software program and samples were adjusted for loading errors, using the α-tubulin loading control band densitometry to standardize, prior to protein phosphorylation being normalized relative to control values.

Data analysis and statistical methods. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. Individual comparisons were made using Student's unpaired t-test, as appropriate. Multiple comparisons were made using one-way ANOVA, followed by Neuman Keuls post hoc test; or Dunnetts post-test for comparing experimental data with control data where appropriate. GraphPad Prism (version 4; GraphPad Prism, La Jolla, CA) was used to perform all statistical analyses and values of P < 0.05 were considered to be significant.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL Figure S1. In vitro validation for shRNA sequences against Tph1. Figure S2. Effects of Tph1 shRNA, scrambled sequence and vehicle control on Tph1, PCNA, and p-ERK1/2 expression in chronic hypoxic rat aorta. Table S1. Sequences for shRNAs against Tph1. Table S2. Body weight and systemic hemodynamic data in rats: effect of chronic hypoxia and Tph1 knockdown. Supplementary Materials and Methods.

Acknowledgments

I.M. was supported by a Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council Industrial Partnership Award with Novartis Respiratory Diseases. K.W. was supported by Medical Research Council. P.C. was supported by the British Heart Foundation. A.H.B. is supported by a British Heart Foundation Personal Chair. The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Supplementary Material

In vitro validation for shRNA sequences against Tph1.

Effects of Tph1 shRNA, scrambled sequence and vehicle control on Tph1, PCNA, and p-ERK1/2 expression in chronic hypoxic rat aorta.

Sequences for shRNAs against Tph1.

Body weight and systemic hemodynamic data in rats: effect of chronic hypoxia and Tph1 knockdown.

REFERENCES

- Chin KM., and, Rubin LJ. Pulmonary arterial hypertension. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;51:1527–1538. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.01.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lane KB, Machado RD, Pauciulo MW, Thomson JR, Phillips JA 3rd, Loyd JE, International PPH Consortium et al. Heterozygous germline mutations in BMPR2, encoding a TGF-beta receptor, cause familial primary pulmonary hypertension. Nat Genet. 2000;26:81–84. doi: 10.1038/79226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keegan A, Morecroft I, Smillie D, Hicks MN., and, MacLean MR. Contribution of the 5-HT(1B) receptor to hypoxia-induced pulmonary hypertension: converging evidence using 5-HT(1B)-receptor knockout mice and the 5-HT(1B/1D)-receptor antagonist GR127935. Circ Res. 2001;89:1231–1239. doi: 10.1161/hh2401.100426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guignabert C, Izikki M, Tu LI, Li Z, Zadigue P, Barlier-Mur AM.et al. (2006Transgenic mice overexpressing the 5-hydroxytryptamine transporter gene in smooth muscle develop pulmonary hypertension Circ Res 981323–1330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morecroft I, Dempsie Y, Bader M, Walther DJ, Kotnik K, Loughlin L.et al. (2007Effect of tryptophan hydroxylase 1 deficiency on the development of hypoxia-induced pulmonary hypertension Hypertension 49232–236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eddahibi S, Guignabert C, Barlier-Mur AM, Dewachter L, Fadel E, Dartevelle P.et al. (2006Cross talk between endothelial and smooth muscle cells in pulmonary hypertension: critical role for serotonin-induced smooth muscle hyperplasia Circulation 1131857–1864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morecroft I, Heeley RP, Prentice HM, Kirk A., and, MacLean MR. 5-hydroxytryptamine receptors mediating contraction in human small muscular pulmonary arteries: importance of the 5-HT1B receptor. Br J Pharmacol. 1999;128:730–734. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0702841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morecroft I, Pang L, Baranowska M, Nilsen M, Loughlin L, Dempsie Y.et al. (2010In vivo effects of a combined 5-HT1B receptor/SERT antagonist in experimental pulmonary hypertension Cardiovasc Res 85593–603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eddahibi S, Humbert M, Fadel E, Raffestin B, Darmon M, Capron F.et al. (2001Serotonin transporter overexpression is responsible for pulmonary artery smooth muscle hyperplasia in primary pulmonary hypertension J Clin Invest 1081141–1150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcos E, Fadel E, Sanchez O, Humbert M, Dartevelle P, Simonneau G.et al. (2004Serotonin-induced smooth muscle hyperplasia in various forms of human pulmonary hypertension Circ Res 941263–1270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Li M, Warburton RR, Hill NS., and, Fanburg BL. The 5-HT transporter transactivates the PDGFbeta receptor in pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells. FASEB J. 2007;21:2725–2734. doi: 10.1096/fj.06-8058com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walther DJ, Peter JU, Bashammakh S, Hörtnagl H, Voits M, Fink H.et al. (2003Synthesis of serotonin by a second tryptophan hydroxylase isoform Science 29976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakowski SA, Geddes TJ, Thomas DM, Levi E, Hatfield JS., and, Kuhn DM. Differential tissue distribution of tryptophan hydroxylase isoforms 1 and 2 as revealed with monospecific antibodies. Brain Res. 2006;1085:11–18. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2006.02.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ni W, Geddes TJ, Priestley JR, Szasz T, Kuhn DM., and, Watts SW. The existence of a local 5-hydroxytryptaminergic system in peripheral arteries. Br J Pharmacol. 2008;154:663–674. doi: 10.1038/bjp.2008.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metzger R, Franke FE, Bohle RM, Alhenc-Gelas F., and, Danilov SM. Heterogeneous distribution of angiotensin I-converting enzyme (CD143) in the human and rat vascular systems: vessel, organ and species specificity. Microvasc Res. 2011;81:206–215. doi: 10.1016/j.mvr.2010.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Izikki M, Hanoun N, Marcos E, Savale L, Barlier-Mur AM, Saurini F.et al. (2007Tryptophan hydroxylase 1 knockout and tryptophan hydroxylase 2 polymorphism: effects on hypoxic pulmonary hypertension in mice Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 293L1045–L1052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan J, Copland I, Post M, Yeger H., and, Cutz E. Mechanical stretch-induced serotonin release from pulmonary neuroendocrine cells: implications for lung development. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2006;290:L185–L193. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00167.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kay JM, Keane PM., and, Suyama KL. Pulmonary hypertension induced in rats by monocrotaline and chronic hypoxia is reduced by p-chlorophenylalanine. Respiration. 1985;47:48–56. doi: 10.1159/000194748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villalón CM., and, Centurión D. Cardiovascular responses produced by 5-hydroxytriptamine:a pharmacological update on the receptors/mechanisms involved and therapeutic implications. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 2007;376:45–63. doi: 10.1007/s00210-007-0179-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li N, Wallén NH, Ladjevardi M., and, Hjemdahl P. Effects of serotonin on platelet activation in whole blood. Blood Coagul Fibrinolysis. 1997;8:517–523. doi: 10.1097/00001721-199711000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hickman AB, Klein DC., and, Dyda F. Melatonin biosynthesis: the structure of serotonin N-acetyltransferase at 2.5 A resolution suggests a catalytic mechanism. Mol Cell. 1999;3:23–32. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80171-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yadav VK, Balaji S, Suresh PS, Liu XS, Lu X, Li Z.et al. (2010Pharmacological inhibition of gut-derived serotonin synthesis is a potential bone anabolic treatment for osteoporosis Nat Med 16308–312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danilov SM, Gavrilyuk VD, Franke FE, Pauls K, Harshaw DW, McDonald TD.et al. (2001Lung uptake of antibodies to endothelial antigens: key determinants of vascular immunotargeting Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 280L1335–L1347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balyasnikova IV, Yeomans DC, McDonald TB., and, Danilov SM. Antibody-mediated lung endothelium targeting: in vivo model on primates. Gene Ther. 2002;9:282–290. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3301657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds PN, Zinn KR, Gavrilyuk VD, Balyasnikova IV, Rogers BE, Buchsbaum DJ.et al. (2000A targetable, injectable adenoviral vector for selective gene delivery to pulmonary endothelium in vivo Mol Ther 2562–578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller WH, Brosnan MJ, Graham D, Nicol CG, Morecroft I, Channon KM.et al. (2005Targeting endothelial cells with adenovirus expressing nitric oxide synthase prevents elevation of blood pressure in stroke-prone spontaneously hypertensive rats Mol Ther 12321–327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds AM, Xia W, Holmes MD, Hodge SJ, Danilov S, Curiel DT.et al. (2007Bone morphogenetic protein type 2 receptor gene therapy attenuates hypoxic pulmonary hypertension Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 292L1182–L1192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds PN, Nicklin SA, Kaliberova L, Boatman BG, Grizzle WE, Balyasnikova IV.et al. (2001Combined transductional and transcriptional targeting improves the specificity of transgene expression in vivo Nat Biotechnol 19838–842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guignabert C, Raffestin B, Benferhat R, Raoul W, Zadigue P, Rideau D.et al. (2005Serotonin transporter inhibition prevents and reverses monocrotaline-induced pulmonary hypertension in rats Circulation 1112812–2819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawut SM, Horn EM, Berekashvili KK, Lederer DJ, Widlitz AC, Rosenzweig EB.et al. (2006Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor use and outcomes in pulmonary arterial hypertension Pulm Pharmacol Ther 19370–374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eddahibi S, Hanoun N, Lanfumey L, Lesch KP, Raffestin B, Hamon M.et al. (2000Attenuated hypoxic pulmonary hypertension in mice lacking the 5-hydroxytryptamine transporter gene J Clin Invest 1051555–1562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camilleri M. LX-1031, a tryptophan 5-hydroxylase inhibitor that reduces 5-HT levels for the potential treatment of irritable bowel syndrome. IDrugs. 2010;13:921–928. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin H, Cianchetta G, Devasagayaraj A, Gu K, Marinelli B, Samala L.et al. (2009Substituted 3-(4-(1,3,5-triazin-2-yl)-phenyl)-2-aminopropanoic acids as novel tryptophan hydroxylase inhibitors Bioorg Med Chem Lett 195229–5232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chin A, Svejda B, Gustafsson BI, Granlund AB, Sandvik AK, Timberlake A.et al. (2012The role of mechanical forces and adenosine in the regulation of intestinal enterochromaffin cell serotonin secretion Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 302G397–G405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Suzuki YJ, Day RM., and, Fanburg BL. Rho kinase-induced nuclear translocation of ERK1/ERK2 in smooth muscle cell mitogenesis caused by serotonin. Circ Res. 2004;95:579–586. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000141428.53262.a4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y., and, Fanburg BL. Serotonin-induced growth of pulmonary artery smooth muscle requires activation of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/serine-threonine protein kinase B/mammalian target of rapamycin/p70 ribosomal S6 kinase 1. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2006;34:182–191. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2005-0163OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Izikki M, Guignabert C, Fadel E, Humbert M, Tu L, Zadigue P.et al. (2009Endothelial-derived FGF2 contributes to the progression of pulmonary hypertension in humans and rodents J Clin Invest 119512–523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fishman AP. Hypoxia on the pulmonary circulation. How and where it acts. Circ Res. 1976;38:221–231. doi: 10.1161/01.res.38.4.221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haas F., and, Bergofsky EH. Role of the mast cell in the pulmonary pressor response to hypoxia. J Clin Invest. 1972;51:3154–3162. doi: 10.1172/JCI107142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humbert M, Sitbon O, Chaouat A, Bertocchi M, Habib G, Gressin V.et al. (2010Survival in patients with idiopathic, familial, and anorexigen-associated pulmonary arterial hypertension in the modern management era Circulation 122156–163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White K, Dempsie Y, Nilsen M, Wright AF, Loughlin L., and, MacLean MR. The serotonin transporter, gender, and 17ß oestradiol in the development of pulmonary arterial hypertension. Cardiovasc Res. 2011;90:373–382. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvq408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray F, MacLean MR., and, Pyne NJ. An assessment of the role of the inhibitory gamma subunit of the retinal cyclic GMP phosphodiesterase and its effect on the p42/p44 mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway in animal and cellular models of pulmonary hypertension. Br J Pharmacol. 2003;138:1313–1319. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0705190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds PN. Gene therapy for pulmonary hypertension: prospects and challenges. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2011;11:133–143. doi: 10.1517/14712598.2011.542139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrell NW, Atochina EN, Morris KG, Danilov SM., and, Stenmark KR. Angiotensin converting enzyme expression is increased in small pulmonary arteries of rats with hypoxia-induced pulmonary hypertension. J Clin Invest. 1995;96:1823–1833. doi: 10.1172/JCI118228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orte C, Polak JM, Haworth SG, Yacoub MH., and, Morrell NW. Expression of pulmonary vascular angiotensin-converting enzyme in primary and secondary plexiform pulmonary hypertension. J Pathol. 2000;192:379–384. doi: 10.1002/1096-9896(2000)9999:9999<::AID-PATH715>3.0.CO;2-Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balyasnikova IV, Berestetskaya JV, Visintine DJ, Nesterovitch AB, Adamian L., and, Danilov SM. Cloning and characterization of a single-chain fragment of monoclonal antibody to ACE suitable for lung endothelial targeting. Microvasc Res. 2010;80:355–364. doi: 10.1016/j.mvr.2010.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SL, Wang WW, Moore BJ., and, Fanburg BL. Dual effect of serotonin on growth of bovine pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells in culture. Circ Res. 1991;68:1362–1368. doi: 10.1161/01.res.68.5.1362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Follenzi A, Sabatino G, Lombardo A, Boccaccio C., and, Naldini L. Efficient gene delivery and targeted expression to hepatocytes in vivo by improved lentiviral vectors. Hum Gene Ther. 2002;13:243–260. doi: 10.1089/10430340252769770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iida Y, Sawabe K, Kojima M, Oguro K, Nakanishi N., and, Hasegawa H. Proteasome-driven turnover of tryptophan hydroxylase is triggered by phosphorylation in RBL2H3 cells, a serotonin producing mast cell line. Eur J Biochem. 2002;269:4780–4788. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1033.2002.03188.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alba R, Bradshaw AC, Coughlan L, Denby L, McDonald RA, Waddington SN.et al. (2010Biodistribution and retargeting of FX-binding ablated adenovirus serotype 5 vectors Blood 1162656–2664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

In vitro validation for shRNA sequences against Tph1.

Effects of Tph1 shRNA, scrambled sequence and vehicle control on Tph1, PCNA, and p-ERK1/2 expression in chronic hypoxic rat aorta.

Sequences for shRNAs against Tph1.

Body weight and systemic hemodynamic data in rats: effect of chronic hypoxia and Tph1 knockdown.