SUMMARY

The zinc-finger transcription factor, Mxr1 activates methanol utilization and peroxisome biogenesis genes in the methylotrophic yeast, P. pastoris. Expression of Mxr1-dependent genes is regulated in response to various carbon sources by an unknown mechanism. We show here that this mechanism involves the highly conserved 14-3-3 proteins. 14-3-3 proteins participate in many biological processes in different eukaryotes. We have characterized a putative 14-3-3-binding region at Mxr1 residues 212–225 and mapped the major activation domain of Mxr1 to residues 246–280, and showed that phenylalanine residues in this region are critical for its function. Furthermore, we report that an unique and previously uncharacterized 14-3-3 family protein in P. pastoris complements S. cerevisiae 14-3-3 functions and interacts with Mxr1 through its 14-3-3-binding region via phosphorylation of Ser215 in a carbon source-dependent manner. Indeed, our in vivo results suggest a carbon source-dependent regulation of expression of Mxr1-activated genes by 14-3-3 in P. pastoris. Interestingly, we observed 14-3-3-independent binding of Mxr1 to the promoters, suggesting a post-DNA binding function of 14-3-3 in regulating transcription. We provide the first molecular explanation of carbon source-mediated regulation of Mxr1 activity, whose mechanism involves a post-DNA binding role of 14-3-3.

Keywords: Gene regulation, transcription inhibition, transcription factor, protein-protein interaction, 14-3-3

INTRODUCTION

The methylotrophic yeast, Pichia pastoris is employed as a model system for studying peroxisome biogenesis as well as for the production of recombinant proteins (Cregg et al., 1989, Cregg et al., 2000, Cereghino & Cregg, 2000, Subramani et al., 2000, Hartner & Glieder, 2006). Genes responsible for methanol catabolism (AOX1, CAT and DHAS encoding alcohol oxidase 1, catalase and dihydroxyacetone synthase, Aox, Cat, and Dhas, respectively) and peroxisome biogenesis (PEX genes) are induced by methanol and oleic acid (Cregg et al., 1989, Hartner & Glieder, 2006). All three methanol utilizing enzymes are sequestered in peroxisomes where the initial reactions of methanol catabolism are compartmentalized, providing a rationale for the concurrent up-regulation of methanol-utilizing enzymes and peroxisomes during growth in methanol (Gould et al., 1992, Liu et al., 1992, Johnson et al., 1999, Stewart et al., 2001). At the first step of methanol catabolism Aox oxidizes methanol to formaldehyde and the toxic by-product hydrogen peroxide is decomposed to oxygen and water by the action of Cat. AOX1 expression is tightly regulated by carbon source being repressed by glucose, ethanol and glycerol and induced by methanol (Cregg et al., 1989, Koutz et al., 1989, Ellis et al., 1985). Due to its efficient induction and tight regulation, the methanol-inducible promoter of AOX1 (PAOX1) has been employed in most heterologous recombinant protein overexpression systems in P. pastoris (Cereghino & Cregg, 2000, Cregg et al., 2000, Sakai et al., 1995, Gellissen, 2000).

Expression of the MUT (methanol utilizing) enzymes is regulated mainly at the transcriptional level by a zinc-finger transcription factor Mxr1 (methanol expression regulator 1) (Cregg et al., 1989, Cregg & Madden, 1988, Tschopp et al., 1987, Lin-Cereghino et al., 2006). Functional disruption of Mxr1 causes a growth defect of P. pastoris in media containing methanol or oleic acid, and the expression of AOX1 and DHAS was dramatically decreased. The oleic acid-induced expression of peroxisome biogenesis genes (i.e., PEX5, PEX8, PEX14 and FLD1) was modestly affected and β-oxidation genes were affected hardly at all upon disruption of MXR1 (Lin-Cereghino et al., 2006). The binding sites for Mxr1 upstream of the MUT pathway and peroxisome biogenesis genes’ promoters have been well characterized (Lin-Cereghino et al., 2006, Hartner et al., 2008, Kranthi et al., 2010, Kranthi et al., 2009). A consensus sequence consisting of a core 5′ -CYCC- 3′ motif is recognized by Mxr1 (Kranthi et al., 2009). Despite the constitutive expression of Mxr1 in glucose grown cells its activity remains repressed, suggesting the existence of post-translation modification(s) that regulate its activity (Lin-Cereghino et al., 2006). However, any post-translation modification(s) that might regulate Mxr1 activity in response to glucose is unknown. Based on immunofluorescence studies of a Mxr1-GFP fusion protein it was proposed that decreased nuclear localization of Mxr1 in glucose grown cells might be an explanation for glucose repression of Mxr1-dependent AOX1 and other methanol-inducible genes (Lin-Cereghino et al., 2006). However, it is unknown why Mxr1 remains inactive in ethanol- and glycerol-grown cells despite its nuclear localization in those growth conditions (Lin-Cereghino et al., 2006).

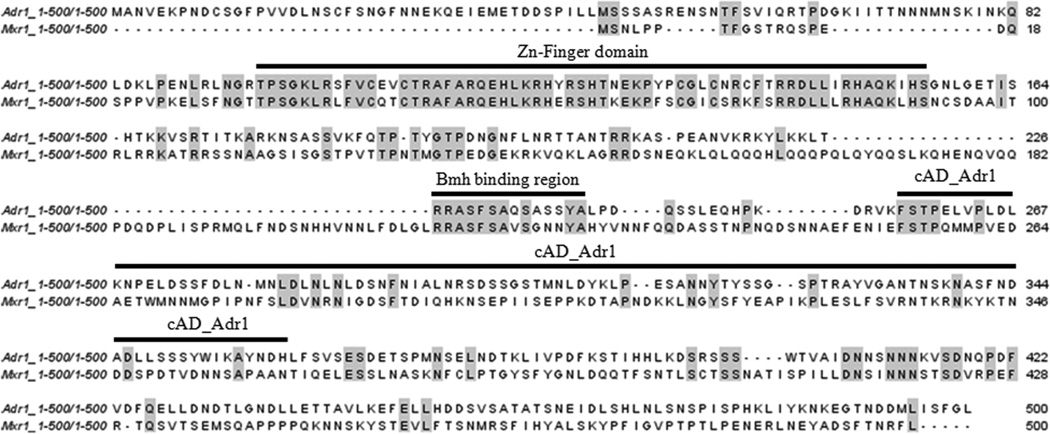

As observed by Lin-cereghino et al. 2006, the N-terminally located C2H2 zinc-finger DNA binding domain (residues 29–101) of Mxr1 shares ~70% sequence identity with the DNA binding domain (residues 95–156) of Saccharomyces cerevisiae Adr1 (alcohol dehydrogenase II synthesis regulator), a transcription factor regulating the expression of glucose-repressed genes involved in the metabolism of non-fermentable carbon sources such as glycerol, lactate, amino acids, ethanol and oleic acid (Denis et al., 1981, Hartshorne et al., 1986, Young et al., 2003, Simon et al., 1995, Simon et al., 1992, Ciriacy, 1979). Despite the high sequence similarities with the DNA binding region of Adr1, Mxr1 does not show any cross-reactivity for Adr1-binding UAS (upstream activator sequence) elements (Kranthi et al., 2009). Outside of their DNA binding regions, which share a similar location, Mxr1 and Adr1 share little homology, despite their similar size and analogous function in regulating the metabolism of non-fermentable substrates. The only other region of homology within Mxr1 is a short stretch of amino acids which shares approximately 70% sequence identity (Fig 1) with the core 14-3-3 (Bmh) binding region (Conserved region 1) (Parua et al., 2010) located within the regulatory domain of Adr1.

Fig 1.

Sequence alignment of Mxr1 and Adr1. The alignment was done using web server based alignment program, ClustalW2 (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/Tools/msa/clustalw2/) (Larkin et al., 2007) by taking 1–500 amino acids of both the proteins. cAD, cryptic activation domain and Zn-Finger, DNA binding domain.

14-3-3 proteins are ubiquitous, highly conserved, acidic and dimeric proteins that play important roles in controlling a wide variety of cellular processes, including cell cycle, metabolism, apoptosis and gene expression by binding to phosphoserine- or phosphothreonine-containing motifs in numerous target proteins (Jones et al., 1995, Xiao et al., 1995, Muslin et al., 1996, Yaffe et al., 1997, Fu et al., 2000, Ferl et al., 2002, Mackintosh, 2004, Wilker et al., 2005, Aitken, 2006, van Heusden & Steensma, 2006). The yeast S. cerevisiae has two genes encoding redundant 14-3-3 proteins, Bmh1 and Bmh2 (van Heusden et al., 1995, van Heusden & Steensma, 2006, Gelperin et al., 1995). Either Bmh protein can fulfill all of the essential functions in budding yeast. As in higher eukaryotes, yeast 14-3-3 proteins are involved in numerous signaling and cell differentiation pathways, including glucose repression. 14-3-3 proteins have not been reported in P. pastoris but their ubiquitous presence in other eukaryotes makes it likely that this yeast also contains at least one homolog which may have functional similarities to Bmh in S. cerevisiae.

Bmh in S. cerevisiae is involved in glucose repression at two levels. By binding to Reg1, the regulatory subunit of the Glc7 protein phosphatase, Bmh participates in the inactivation of the AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) Snf1 when cells are grown in glucose (Dombek et al., 2004, Mayordomo et al., 2003, Ichimura et al., 2004). Snf1 is essential for activation of Adr1, and thus Bmh indirectly inhibits the expression of Adr1 target genes. Recently we described a Reg1-independent role of Bmh in glucose repression that acts directly through binding to Adr1 (Parua et al., 2010). Bmh binds to the Ser230-phosphorylated regulatory domain of Adr1 and inhibits the activity of a nearby cryptic activating region.

Based on this observation, we investigated whether there is 14-3-3-dependent regulation of Mxr1 activity in P. pastoris. We show that Mxr1 contains a highly conserved yeast 14-3-3 binding motif and P. pastoris has a unique and previously uncharacterized 14-3-3 family protein that interacts with Mxr1 through its 14-3-3 motif. The interaction is necessary to differentially regulate the activity of Mxr1 depending on the available carbon source. We provide evidence that 14-3-3-mediated regulation of transcription occurs at a step after DNA-binding. We also demonstrate that the first 400 amino acids of Mxr1 are sufficient for carbon source-mediated repression and activation of Mxr1-regulated genes and map the major activation domain of Mxr1 to this region of the protein. The P. pastoris 14-3-3 is able to complement a budding yeast strain with defective Bmh genes, indicating that it can fulfill the essential functions of Bmh in S. cerevisiae.

RESULTS

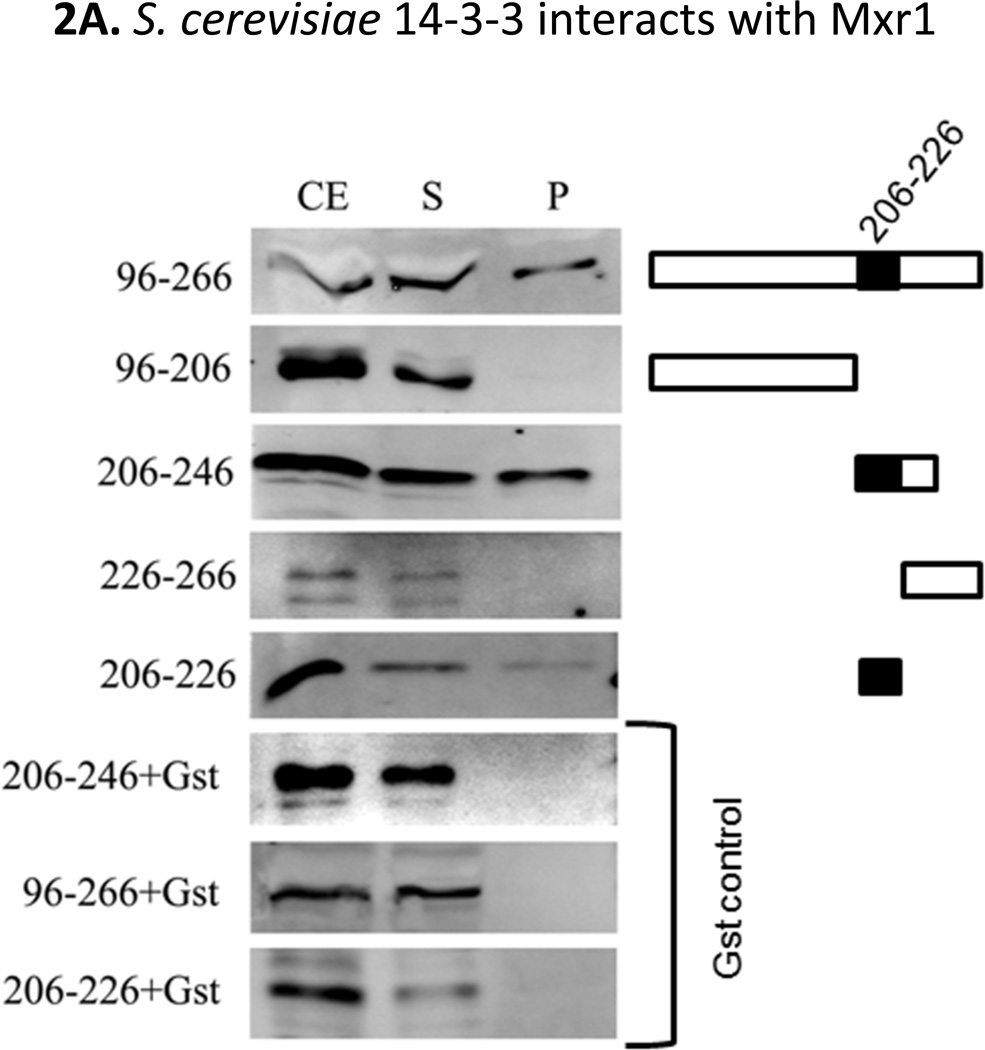

S. cerevisiae 14-3-3 interacts with Mxr1

Besides the closely-related C2H2 Zn-finger DNA binding domains (Lin-Cereghino et al., 2006), the sequence alignment (Fig 1) between residues 1–500 of both Mxr1 and Adr1 reveals the presence of only one other region of homology (~70% sequence identity) corresponding to the Bmh1/2 (S. cerevisiae 14-3-3 homologs)-binding region of Adr1, residues 226–240. This putative 14-3-3 binding site (-RRASFS------YA-) is located between amino acids 212–225 of Mxr1. Based on this sequence analysis we asked whether S. cerevisiae 14-3-3 proteins can interact with Mxr1 through the observed putative binding motif. To answer this question, five GBD (Gal4 DNA binding domain)-Mxr1 fusion proteins, encompassing different regions of Mxr1 were generated and tested in pulldown assays with Gst (Glutathione-S-transferase)-Bmh1. As shown in Fig 2A, GBD-Mxr1 proteins (encompassing amino acids 96–266, 206–246 and 206–226 of Mxr1) having the putative Bmh binding region were retained on glutathione sepharose 4B-immobilized Gst-Bmh1 resin. The fusion protein GBD-Mxr1 (206–226) showed low binding to the Gst-Bmh1 beads compared to the other two. A possible explanation is that the short 20-residues long peptide might not be fully accessible in the fusion protein. This indicates a physical interaction between Mxr1 and S. cerevisiae Bmh1. Fusion proteins having amino acids 96–206 or 226–266 of Mxr1 but lacking the putative Bmh binding region, did not exhibit any interaction with Gst-Bmh1. The empty Gst-control experiments further confirmed the specificity of the interaction between Bmh1 and Mxr1. Thus, Bmh interacts with Mxr1 and does so through the putative Bmh-binding region, amino acids 212–225.

Fig 2.

A. Interaction studies between Mxr1 and Bmh1. Gst-pulldown assays were done using Gst-Bmh1 or Gst, which was expressed in E.coli and immobilized on glutathione sepharose-4B column, followed by application of yeast extract containing overexpressed GBD (Gal4 DNA binding domain)-Mxr1 fusion protein. All fractions were electrophoresed in 12% SDS-PAGE and visualized by western blotting with anti-GBD antibody. Black shaded region (residues 206–226) represents the putative Bmh-binding region. B. Interaction studies of C4qzn3 with Pichia pastoris Mxr1 and S. cerevisiae Adr1. Gst-pulldown assays were done using Gst-Bmh1, Gst-C4qzn3. Yeast extracts containing either overexpressed GBD-Mxr1 or GBD-Adr1 variants was used in this study. All fractions were electrophoresed in 15% SDS-PAGE and visualized by western blotting with anti-GBD antibody or anti-pSer230 antibody. C. Gst-pull down in presence and absence of phosphatase. Gst-pulldown was done following the protocol as described before using Gst-C4qzn3 and yeast extract containing GBD-Mxr1 (210–226) fusion protein in presence and absence of 10U of calf intestinal phosphatase (CIP) at 30°C. Upper panel is the western blot profile of the pulldown fractions obtained by using anti-GBD antibody and lower panel represents the quantitative assays of the western blot results. CE: Cell extract, S: Supernatant and P: pellet fraction.

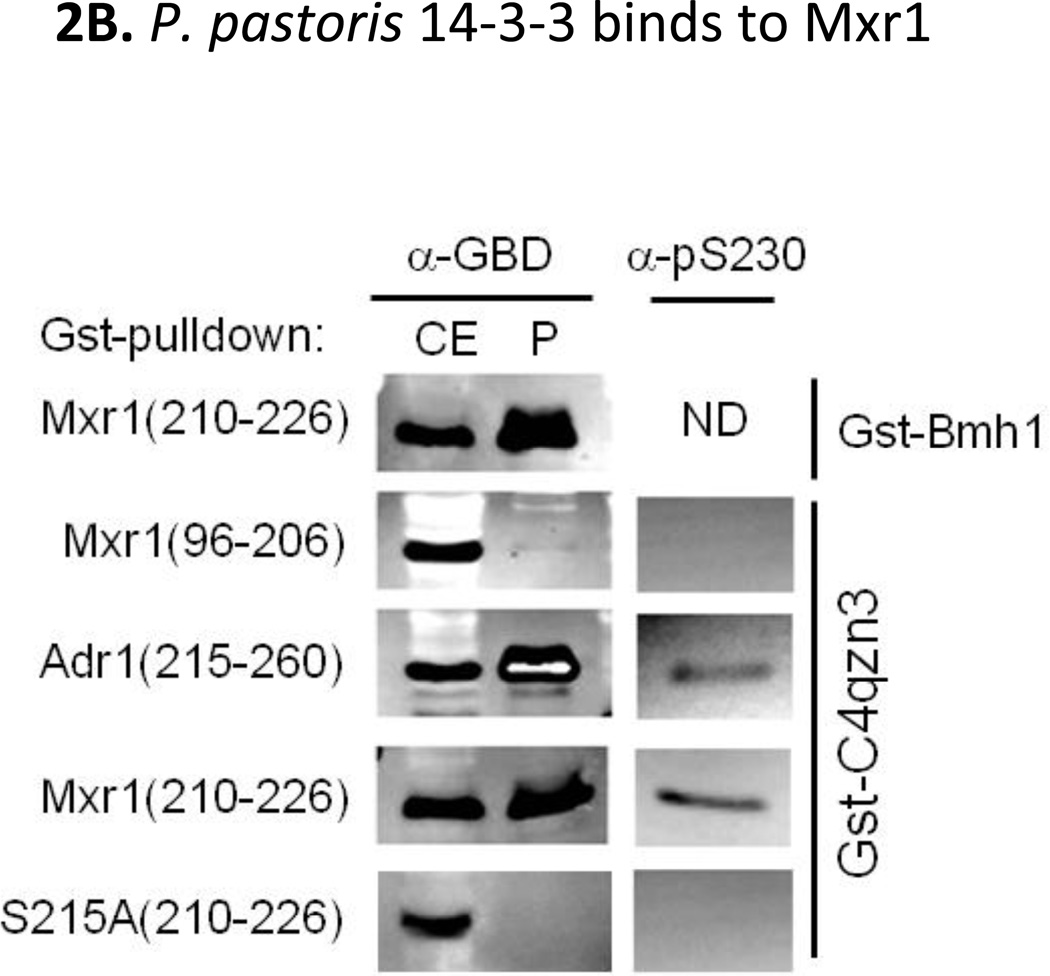

14-3-3 of Pichia pastoris binds to Mxr1

Genome-wide searching and sequence alignment analyses (Supplementary Fig. 1) indicate that P. pastoris has an uncharacterized 14-3-3 family protein, known as C4qzn3 (257 residues) located on chromosome 2. This putative 14-3-3 shares almost 90% sequence identity with 14-3-3 proteins from other eukaryotes, S. cerevisiae, S. pombe, C. albicans, D.†melanogaster, plants and human (Supplementary Fig. 1). Gst-pulldown experiments were performed using Gst-C4qzn3 or Gst-Bmh1 expressed in E. coli and yeast extracts containing GBD-Mxr1 or GBD-Adr1 fusion variants to assess their possible interaction. Comparable amounts of both GBD-Adr1 (215–260) and GBD-Mxr1 (210–226) were retained on Gst-C4qzn3-bound resin as observed for GBD-Mxr1 (210–226) on Gst-Bmh1-bound resin (Fig 2B). GBD-Mxr1 (96–206), lacking the Bmh-binding region was not pulled down with Gst-C4qzn3, suggesting that the interaction was specific for the presence of the Bmh-binding region (residues 212–225) in Mxr1. These results demonstrate that the putative Pichia pastoris 14-3-3 protein has the ability to interact with both transcription factors, P. pastoris Mxr1 and S. cerevisiae Adr1 at their respective Bmh-binding regions.

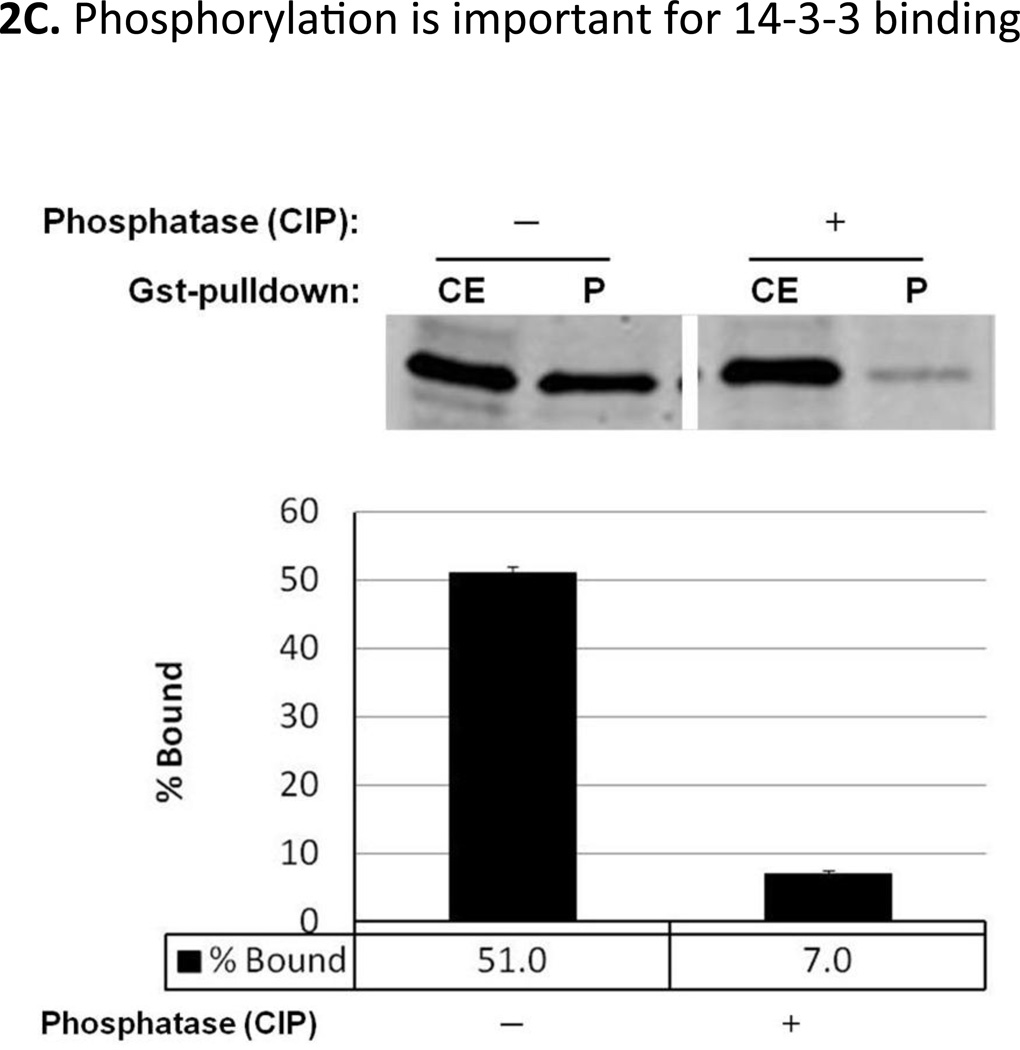

14-3-3 interacts with Mxr1 via phosphorylation of Ser215

14-3-3 proteins preferentially recognize Ser/Thr- phosphorylated targets and in our previous work we observed that Bmh interacts with Adr1 via phosphorylation of Ser230, which is located within the core Bmh-binding region (Parua et al., 2010). The sequence alignment in Fig 1 shows that Ser215 of Mxr1 is the residue corresponding to Ser230 of Adr1 which is known to be phosphorylated in a carbon-source regulated manner. To determine if the phosphorylation status of Ser215 plays a role in 14-3-3 binding to Mxr1, we first examined the phosphorylation status of Ser215 by performing immunoblotting experiments with anti-pSer230 antibody raised against the homologous phosphorylated Bmh1 binding motif of Adr1 (Ratnakumar et al., 2009). As shown in Fig 2B, the anti-pSer230 antibody reacted with the pulled-down fraction of GBD-Mxr1 (210–226) and GBD-Adr1 (215–260), and not with cell extract of GBD-Mxr1 (96–206), suggesting that Ser215 within the 14-3-3 motif is phosphorylated in S. cerevisiae. To determine the role of pSer215 in binding of 14-3-3 to Mxr1, Ser215 was substituted with Ala in GBD-Mxr1 (210–226) and Gst-pulldown assays were performed. As shown in Fig 2B the S215A mutant was neither pulled down nor recognized by the anti-pSer230 antibody suggesting that phosphorylation of Ser215 is essential for 14-3-3 binding. The phosphorylation-dependent interaction between 14-3-3 and Mxr1 was further confirmed by performing Gst-pulldown assays using Gst-immobilized P. pastoris 14-3-3 and yeast extract containing fusion protein GBD-Mxr1 (210–226) following the same protocol as described before in presence and absence of 10U of calf intestinal phosphatase (CIP; NEB) at 30°C. As shown in Fig. 2C, the phosphatase treatment significantly reduced the interaction, suggesting that the phosphorylation of Mxr1 is important for binding by 14-3-3 and most likely pSer215 is the target.

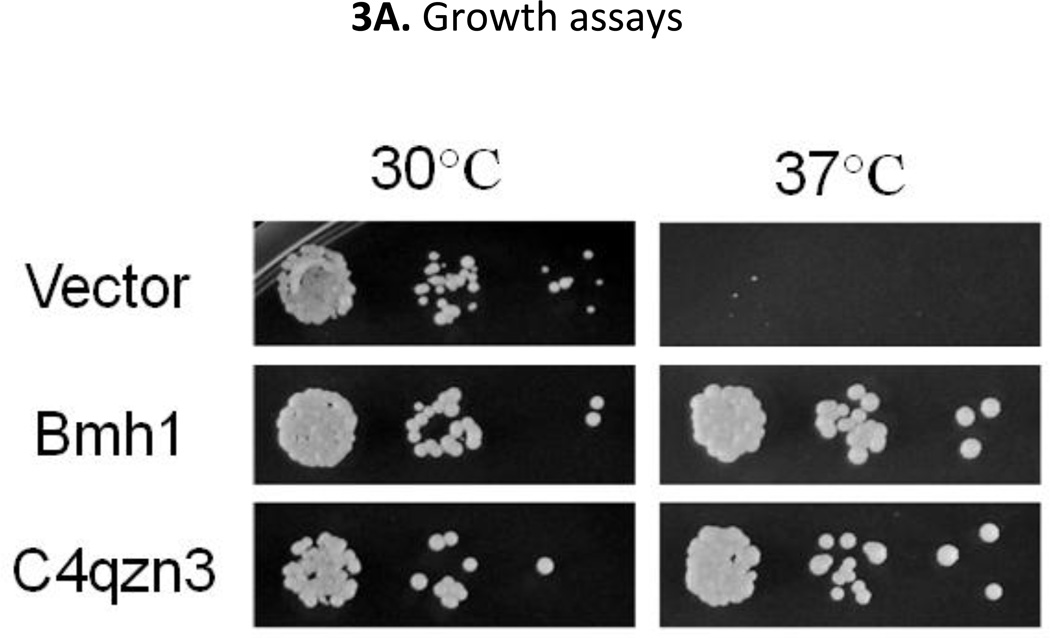

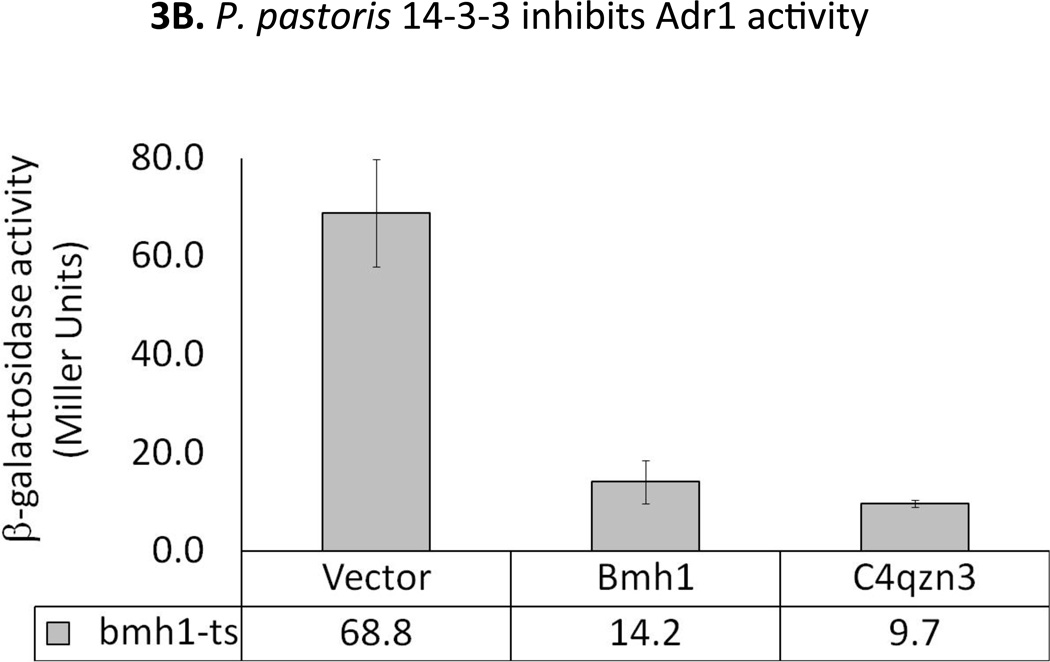

14-3-3 protein of Pichia pastoris complements Bmh function(s) in S. cerevisiae

The ability of the P. pastoris 14-3-3 protein to complement the loss of 14-3-3 function in S. cerevisiae would demonstrate that C4QZN3 encodes a functional homolog. First, the ability of N-terminally HA-tagged P. pastoris 14-3-3 (from pBF-C4QZN3) or Bmh1 (from pBF-BMH1) to complement the growth defect of a bmh2Δ bmh1-ts mutant strain at 37°C was examined. As shown in Fig 3A, expression of P. pastoris 14-3-3 rescued growth at 37°C as well as Bmh1, suggesting that P. pastoris 14-3-3 can perform all of the essential functions of the S. cerevisiae 14-3-3 proteins. Next, the regulatory effect of P. pastoris 14-3-3 protein on the transcriptional activity of Adr1 was tested. We evaluated the activity of endogenous Adr1 by assaying expression of the Adr1-dependent reporter gene, ADH2p-lacZ in bmh2Δ bmh1-ts (YLL1087) strain. The expression of the reporter is inhibited by Bmh due to its binding to the Adr1 regulatory region and consequent inhibition of Adr1 activity. Loss of Bmh activity results in a high level of reporter expression and thus high β-galactosidase activity. Restoration of Bmh function decreases this activity. P. pastoris 14-3-3 protein or Bmh1 expressed in S. cerevisiae bmh2Δ bmh1-ts cells gave rise to a 5-fold lower level of β-galactosidase activity compared to the same cells without a wild type 14-3-3 protein (Fig. 3B). This indicates that the P. pastoris 14-3-3 protein has the ability to inhibit Adr1 activity and suggests that it also might inhibit Mxr1 activity in P. pastoris.

Fig 3.

A. Growth test of bmh2Δ bmh1-ts mutant strain expressing either HA-tagged Pichia 14-3-3 (C4qzn3) or Bmh1 at 30°C and 37°C on Trp− plates. B. Evaluation of the activity of endogenous Adr1 by exploiting a reporter gene (ADH2p-lacZ) expression assays. S. cerevisiae bmh2Δbmh1-ts cells harboring a pair of plasmids, one expressing either P. pastoris 14-3-3 or Bmh1 or none (empty vector), another providing the reporter construct (pLG-ADH2-lacZ; lacZ under the control of ADH2 promoter) were used as host and grown at 30°C. The error bars represent the averages of the results for three transformants ± one standard deviation.

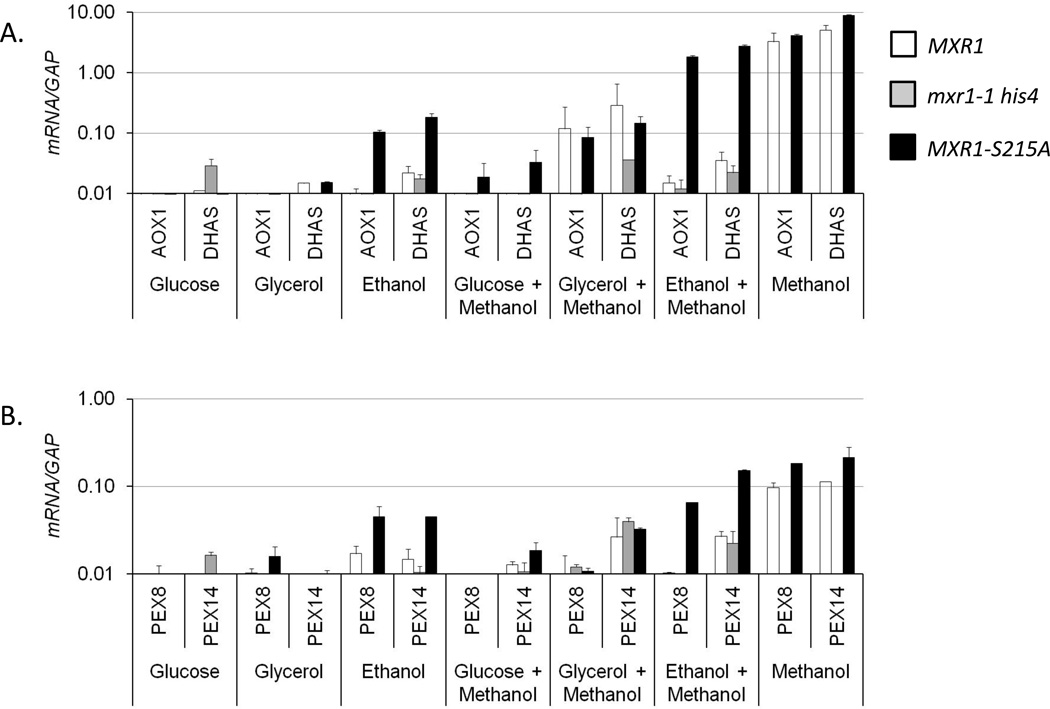

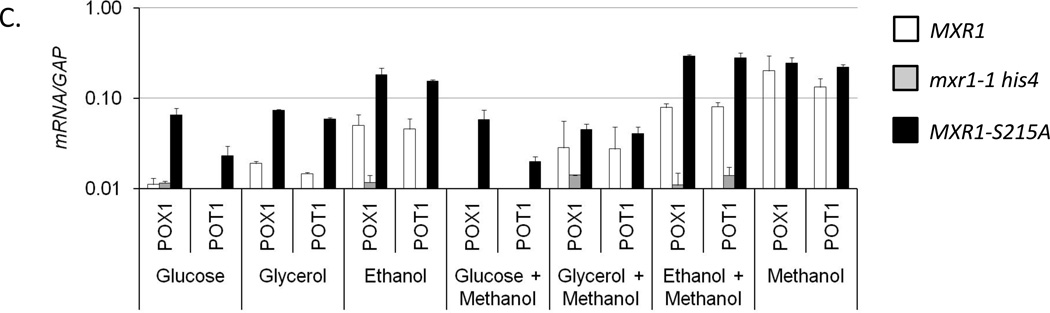

14-3-3-dependent regulation of Mxr1 activity in response to various carbon sources

To determine whether P. pastoris 14-3-3 inhibits Mxr1 activity, in its natural host a mutation that abrogates the in vitro interaction of 14-3-3 with Mxr1 (S215A) was introduced into a plasmid-borne copy of MXR1. The mutant protein was expressed after integration of the plasmid into the P. pastoris genome of a strain lacking endogenous MXR1 (JC132, Table 1). The activity of wild type and mutant protein was assayed by qRT-PCR analysis of mRNAs derived from Mxr1-regulated genes. Total RNA was extracted from strains lacking MXR1 (JC132), or containing either the wild type (JC100) or S215A mutant (PPP1) allele after growth in various repressing and inducing media. It has been reported that glucose, glycerol, and ethanol can each repress the expression of the solely Mxr1-dependent genes AOX1 and DHAS, which are involved in methanol assimilation. The expression of these two genes, as well as genes involved in peroxisome biogenesis (PEX8 and PEX14) and fatty acid oxidation (POT1, thiolase and POX1, oxidase) was quantified after growth in fully repressing medium containing either 0.5% glucose, or 0.5% glycerol or 0.5% ethanol; inducing medium containing 0.5% methanol; and repressing medium containing inducer, i.e. either 0.5% glucose or 0.5% glycerol or 0.5% ethanol supplemented with 0.5% methanol. As shown in Fig 4A–C, expression of all of the genes in the wild type Mxr1 strain was repressed in the presence of glucose as has been observed by others (Cregg et al., 1989, Ellis et al., 1985, Koutz et al., 1989, Lin-Cereghino et al., 2006). Moreover, glycerol-mediated repression of all of these genes was also observed in the wild type Mxr1 strain. This was surprising because the PEX and fatty acid oxidation genes of S. cerevisiae are derepressed when glycerol is the sole carbon source. MUT pathway genes and genes involved in peroxisome biogenesis were repressed significantly in wild type ethanol grown cells (Fig 4A and B). However, fatty acid oxidation genes were not repressed in ethanol (Fig 4C), which is analogous to Adr1-dependent derepression of the β-oxidation pathway genes in ethanol media in S. cerevisiae. Furthermore, their complete repression in the mxr1-1 null mutant strain suggests that expression of β-oxidation pathway genes is highly Mxr1-dependent.

Table 1.

Yeast strains

| Strain | Genotype | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| S. cerevisiae | ||

| PJ69-4a | MATa trp1-901 leu2-3,112 ura3-52 his3-200 gal4Δ gal80Δ LYS2:GAL1-HIS3 GAL2-ADE2 met2:GAL7-lacZ | (James et al., 1996) |

| YLL908 | W303 MATa bmh2Δ::kanmx | (Lottersberger et al., 2003) |

| YLL1087 | W303 MATa bmh2Δ::kanmx bmh1Δ::HIS3::YIpbmh1-170(LEU2). | (Lottersberger et al., 2003) |

| P. Pastoris | ||

| JC100 | Wild type | (Cregg et al., 1998) |

| JC132 | mxr1-1 his4 | (Johnson et al., 1999) |

| PPP1 | MXR1-S215A | This study |

| PPP2 | MXR1tm-S215A | This study |

| PPP3 | MXR1tm | This study |

Fig 4.

Studies on Mxr1-dependent expression of genes involved in methanol utilization (AOX1 and DHAS), peroxisome biogenesis (PEX8 and PEX14) and fatty acid oxidation (POT1 and POX1) in P. pastoris in response to different carbon sources. mRNA was extracted from strains JC100 (MXR1WT), JC132 (mxr1-1 his4), PPP1 (MXR1-S215A) both in repressed (0.5% Glucose, 0.5% Glycerol and 0.5% Ethanol) and induced (0.5% Methanol) as well as repressed plus methanol growth conditions. Quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR) was performed to determine the levels of mRNA. The mRNA levels were normalized to the levels of GAP mRNA in each sample. The error bars represent the mean of three biological replicates assayed in duplicate.

Interestingly there was derepression of the expression of fatty acid oxidation genes (~7- to 8- fold in glucose media and ~2- to 3-fold in glycerol media), methanol assimilation pathway genes (more than 10-fold in ethanol growth condition) and peroxisome biogenesis genes (~2- to 3-fold in ethanol media) in the strain carrying the S215A mutant allele, suggesting that disruption of the interaction with 14-3-3 reduces carbon source-inhibited transcriptional activation by Mxr1 (Fig 4). Addition of methanol into the ethanol growth media further increased the expression of the AOX1, DHAS and PEX14 in the S215A mutant strain to a level comparable to that observed in inducing condition (Fig 4A and B). This suggests the existence of at least two layers of control over the expression of MUT and PEX genes. All of the genes tested remained repressed after addition of methanol to the glucose media (Fig 4A–C). However modest induction was observed for MUT pathway and β-oxidation genes in the wild type strain upon addition of methanol to glycerol-containing medium (Fig 4A and C), suggesting that glucose and glycerol repress Mxr1 activity through distinct pathways. In the mxr1-1 null mutant none of the genes were expressed in any growth condition and all of them were significantly induced in MXR1 wild type and S215A mutant cells when methanol was the sole carbon source. In conclusion, a mutation that disrupts the interaction of 14-3-3 with Mxr1 allows significant methanol-independent expression of Mxr1-dependent genes.

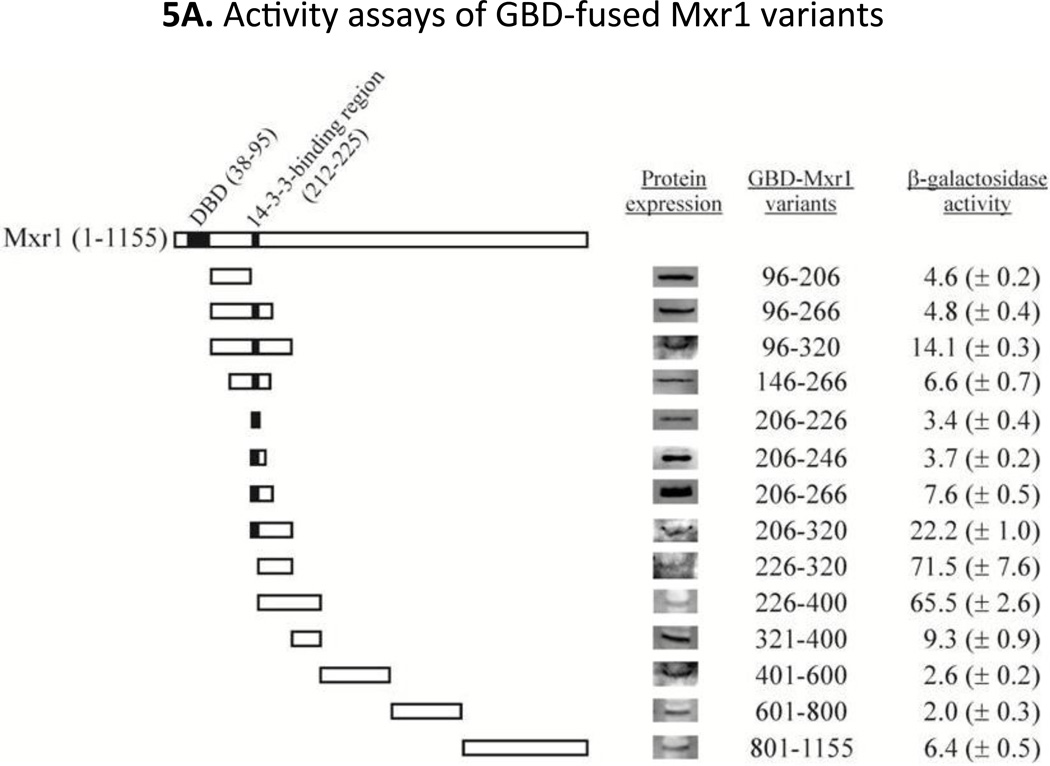

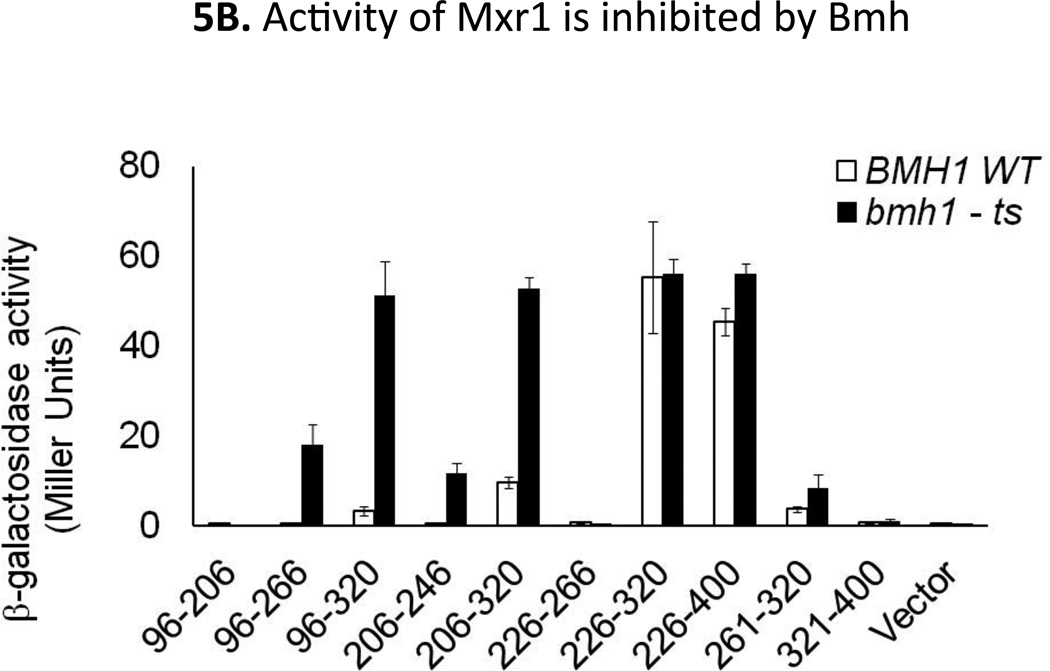

Mapping of activation domain(s) of Mxr1

Although Mxr1 is an important transcription factor for the expression of genes involved in methanol utilization, oleic acid metabolism and peroxisome biogenesis, the existence and location of activation region(s) of the protein have not been identified. Sequence comparison to Adr1 did not identify a region with significant homology to any of its activation domains. To identify and map potential activation domains of Mxr1 we employed yeast one-hybrid assays where GBD-fused variants of Mxr1 (Fig 5A) were expressed in S. cerevisiae strain PJ69-4a (Table 1) and their activity was assayed by evaluating the expression of three Gal4-dependent reporter genes, GAL2p-ADE2, GAL1p-HIS3 and GAL7p-lacZ. As shown in Fig 5A, the highest β-galactosidase activity was observed for the GBD-Mxr1 fusion proteins encompassing residues 226–320 and 226–400, suggesting that a major activation domain is located between residues 226–320. Despite the presence of residues 226–320 the fusion proteins with amino acids 96–320, and 206–320 showed approximately 3 to 5-times lower activity. Interestingly, both of the Mxr1 fusions contain the 14-3-3-binding region (residues 212–225), while fragments, 226–320 and 226–400 do not, suggesting that the 14-3-3-binding region acts to inhibit the function of this activation domain. Furthermore, as shown in Fig 5A, all of the GBD-Mxr1 fusion proteins were expressed significantly, suggesting that the observed activity was not a reflection of the level of expression and the stability of a peptide. The results of the β-galactosidase assays were confirmed by measuring the activity of the GAL1p-HIS3 and GAL2p-ADE2 reporter genes by observing the growth on Trp−, Trp−Ade− and Trp−His− plates (Supplementary Fig 2). Only cells expressing GBD-Mxr1 variants encompassing regions 226–320 or 226–400 showed substantial growth on both Trp−Ade− and Trp−His− plates, confirming the location of a strong activation domain at amino acids 226–320. Consistent with the observed low level of β-galactosidase activity, the fusion proteins encompassing residues, 96–320 and 96–400 showed reduced growth on Trp−His− and no growth on Trp−Ade− plates. As both of the above two fusion proteins contain the observed Bmh binding region (212–225 amino acids), supporting an inhibitory role of the 14-3-3-binding region on activation domain function. Moreover our results indicate the presence of a strong activation region(s) located in the vicinity of the N-terminus just downstream of the zinc-finger DNA binding domain.

Fig 5.

A. Activity assays of GBD-Mxr1 variants. Diagram represents the various Mxr1 fragments, which were generated as GBD (Gal4 DNA binding domain) fusion protein. DBD, DNA binding region and the conserved 14-3-3-binding region (residues 212-225) are highlighted by black shade. Activity was measured by exploiting the reporter gene (lacZ) expression assays, where S. cerevisiae PJ69-4a strain harboring plasmid, which expressed Mxr1 variants as GBD fusion proteins. The strain was also harboring a chromosomal copy of a GAL7p-lacZ reporter cassette. The values are the averages of the results for three transformants ± one standard deviation. Expression level of all GBD-fused Mxr1 peptides was also shown in the figure obtained by western blotting using anti-GBD antibody. B. Activity assays of GBD-Mxr1 proteins in BMH1 wild type (YLL908; bmh2Δ BMH1) and bmh1-ts (YLL1087: bmh2Δ bmh1-170) strain. Activity was assayed by measuring the activity of expressed β-galactosidase from lacZ gene, where cells harboring a pair of plasmids, one having GAL10p-CYC1-lacZ reporter cassette (pHZ18′) and another expressing Mxr1 variants as GBD fusion proteins were grown at 30°C. The error bars represent the averages of the results for three transformants ± one standard deviation.

Our hypothesis that the 14-3-3-binding region inhibits the major activation domain of Mxr1 was confirmed by evaluating the activity of selected GBD-fused Mxr1 variants in both BMH1 wild type (YLL908; bmh2Δ BMH1) and bmh1-ts mutant (YLL1087; bmh2Δ bmh1-170) strains using the GAL10p-CYC1-lacZ reporter gene at 30°C, a temperature sufficiently high to cause a bmh− phenotype (Parua et al., 2010). In both bmh2Δ BMH1 and bmh2Δ bmh1-ts mutant strains we observed comparable amounts of activity for the GBD-Mxr1 (226–320) and GBD-Mxr1 (226–400) fusion proteins, which lack the Bmh binding region (Fig 5B). Fusion proteins containing both the Bmh binding region and all or part of the activation region (96–266, 96–320, 206–246, and 206–320), were approximately 5- to 15-fold more active in the bmh2Δ bmh1-ts mutant than in the wild type strain (Fig 5B). All other fusion proteins tested had little or no activity in both strains. The absence of activity for the fusion protein encompassing residues 226–266 and the low activity of the 261–320 fragment suggests the critical role of the entire 226–320 region for the activity of Mxr1. Inactivation of Bmh or removal of the 14-3-3-binding region suppressed the inhibition of activation. This suggests that the binding of 14-3-3 to amino acids 212–225 of Mxr1 inhibits the activity of the major activation domain located at residues 226–320.

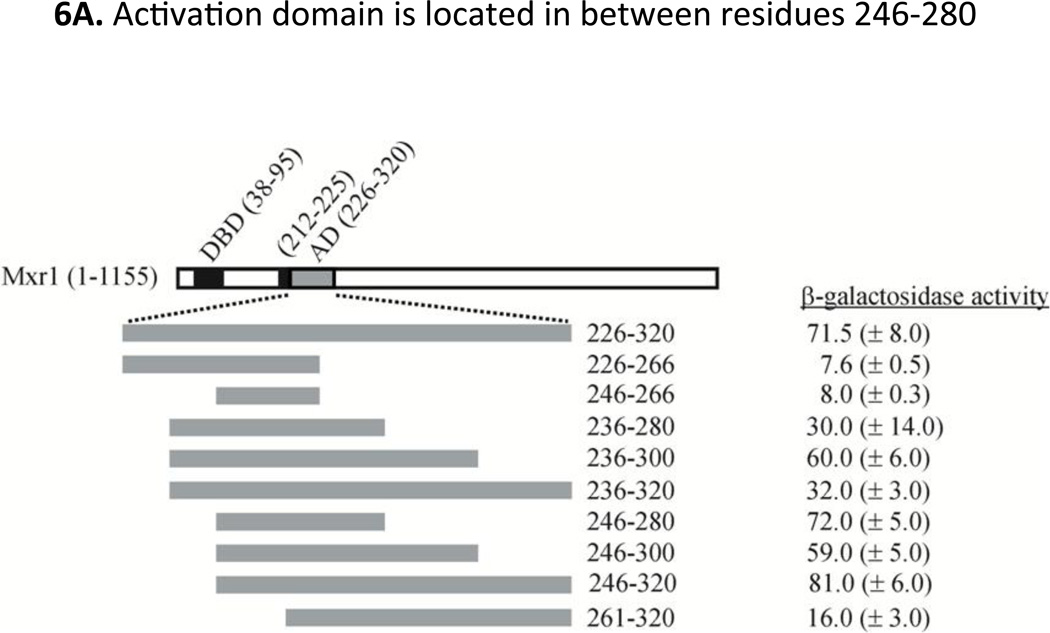

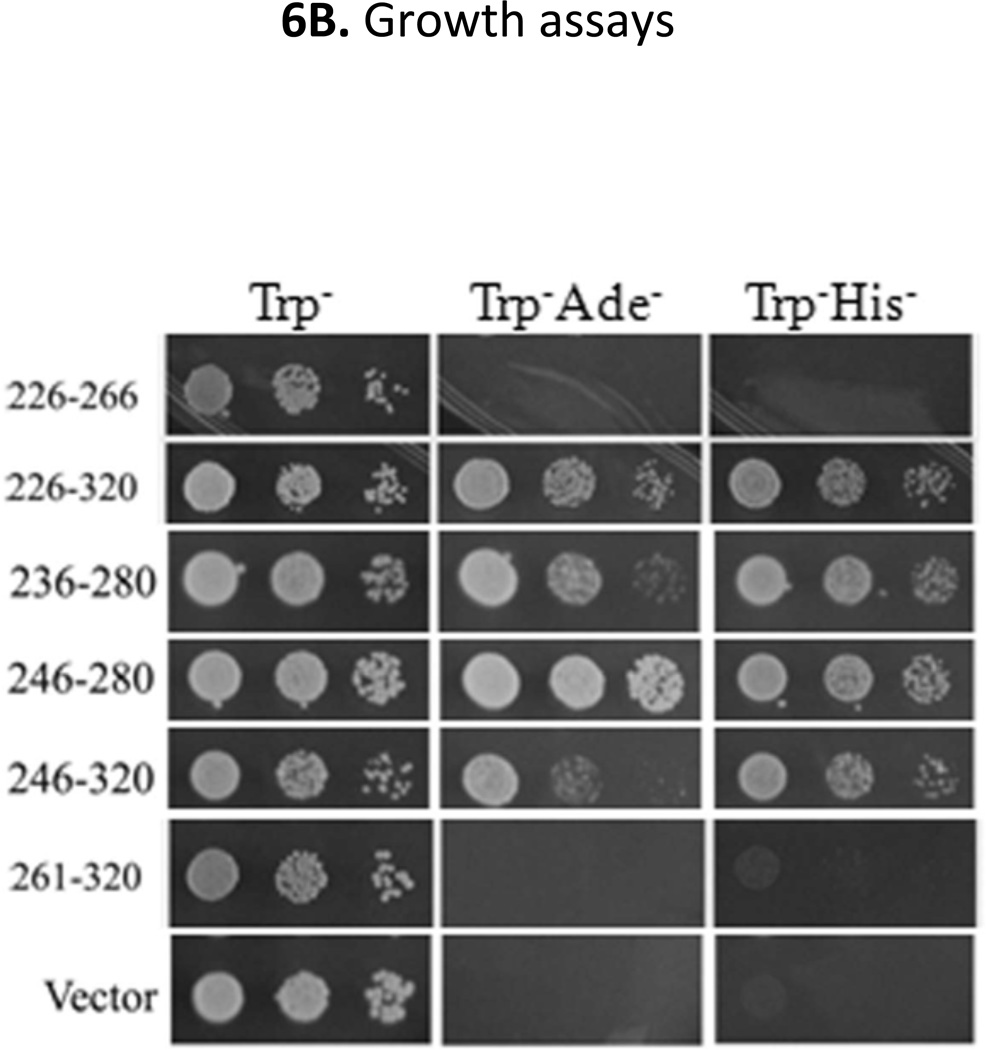

Characterization of the major activation domain of Mxr1

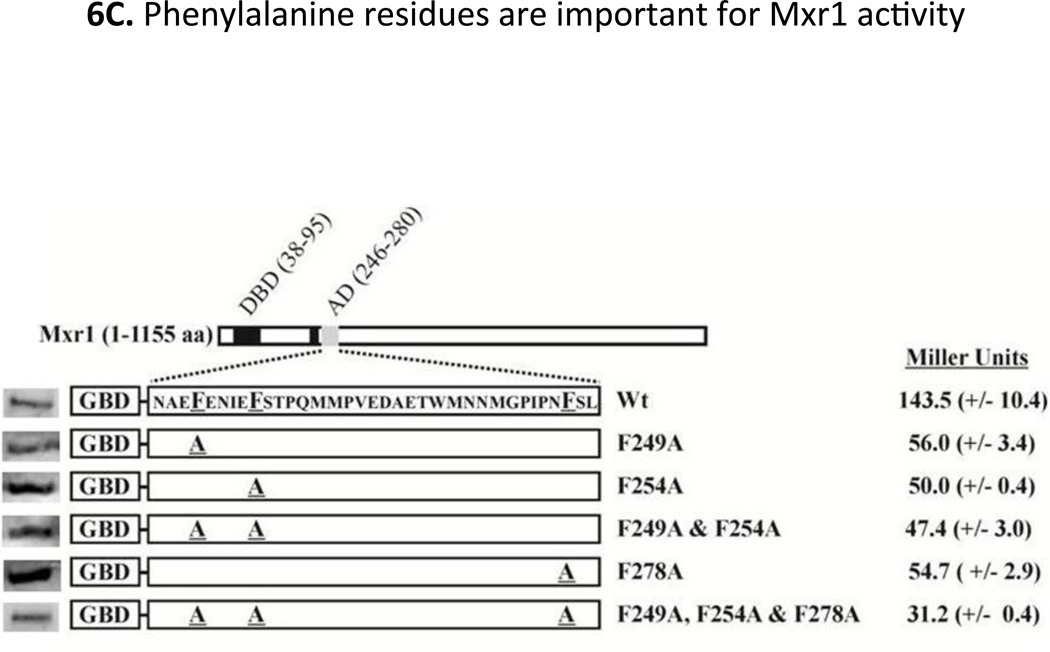

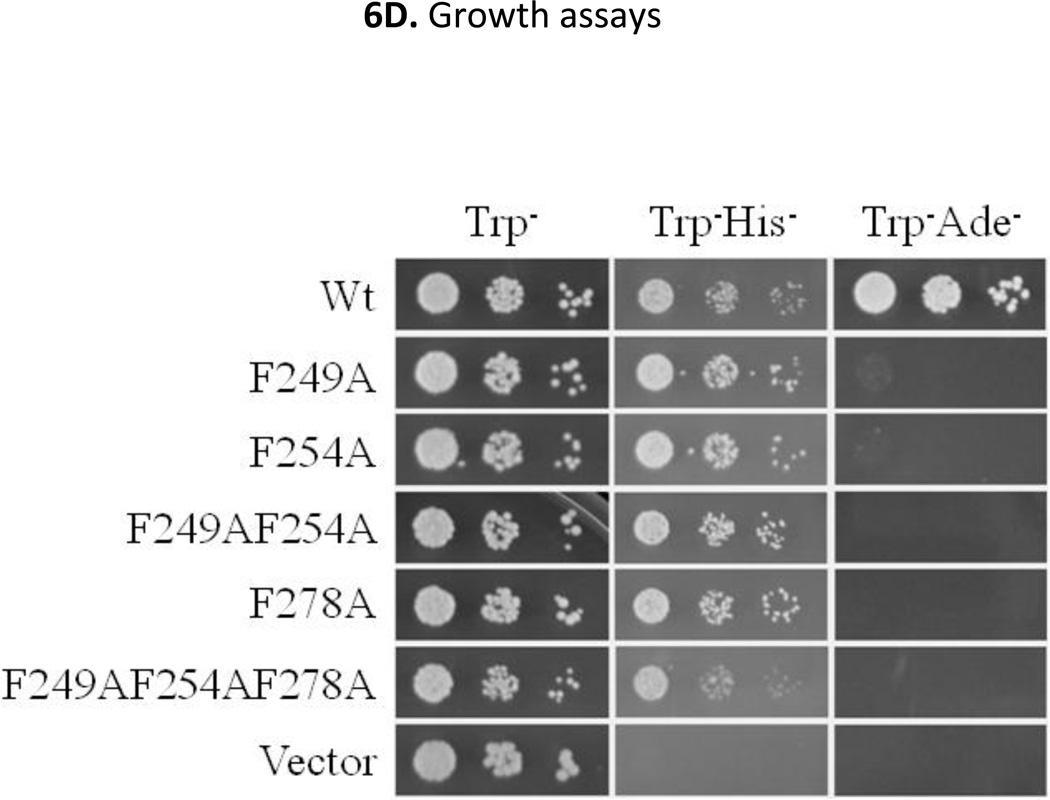

To map the activation domain more precisely we generated additional GBD-Mxr1 fusion proteins spanning residues 226–320 of Mxr1 and measured their activity in strain PJ69-4a. The results of the β-galactosidase (Fig 6A) and growth assays (Fig 6B) indicate that the shortest region capable of conferring activating function is located between amino acids 246 and 280.

Fig 6.

A. Indicated different Mxr1 fragments encompassing the 226–320 amino acids region, were expressed as GBD (Gal4 DNA binding domain) fusion protein in yeast two hybrid strain PJ69-4a. The activity was measured by monitoring lacZ expression from GAL7p promoter. The values are the averages of the results for three transformants ± one standard deviation. B. Growth test of PJ69-4a harboring different GBD-Mxr1 constructs at 30°C on selective amino acid (Trp− and Trp−His−) and/or amino acid-nucleotide (Trp−Ade−) deficient plates. C. Indicated Mxr1 fragments encompassing the 246–280 amino acids region having specific Phe to Ala mutation(s) were expressed as GBD (Gal4 DNA binding domain) fusion proteins and activity was measured as described before. Expression level of all of the fusions was also shown in the figure. The values are the averages of the results for three transformants ± one standard deviation. D. Growth test of PJ69-4a was performed at 30°C as described before.

Interestingly, the shortest functional region of Mxr1 (residues 246–280) is enriched in hydrophobic and acidic residues (See Fig 1), characteristics of canonical activation domains in which bulky hydrophobic residues are frequently important for activation domain function (Blair et al., 1994, Cress & Triezenberg, 1991, Drysdale et al., 1995, Folkers et al., 1995, Gill et al., 1994, Lin et al., 1994, Regier et al., 1993, Almlöf et al., 1997, Young et al., 1998). The importance of the three phenylalanine residues located within this region of Mxr1 at positions 249, 254 and 278 was tested by substituting them by Ala either individually or in combination. All of the mutants were expressed as GBD-fusion proteins in S. cerevisiae strain PJ69-4a and their activity was measured by means of β-galactosidase activity and growth assays as described above. A three-fold decrease in GAL7p-lacZ expression was observed when individual Phe residues were changed to Ala. Substitution of all three to Ala caused an approximately 5-fold decrease in expression compared to the wild type fusion protein (Fig 6C). Furthermore, the cells expressing either a single, double, or triple mutant protein were inviable on Trp−Ade− medium (Fig 6D). Western blot analysis of the GBD fusion proteins indicated that all the mutant proteins were expressed at a significant level (Fig 6C). These observations corroborate the importance of the hydrophobic Phe residues for the activity of the GBD-Mxr1 fusion protein and show that this region of Mxr1 functions as a canonical activation domain.

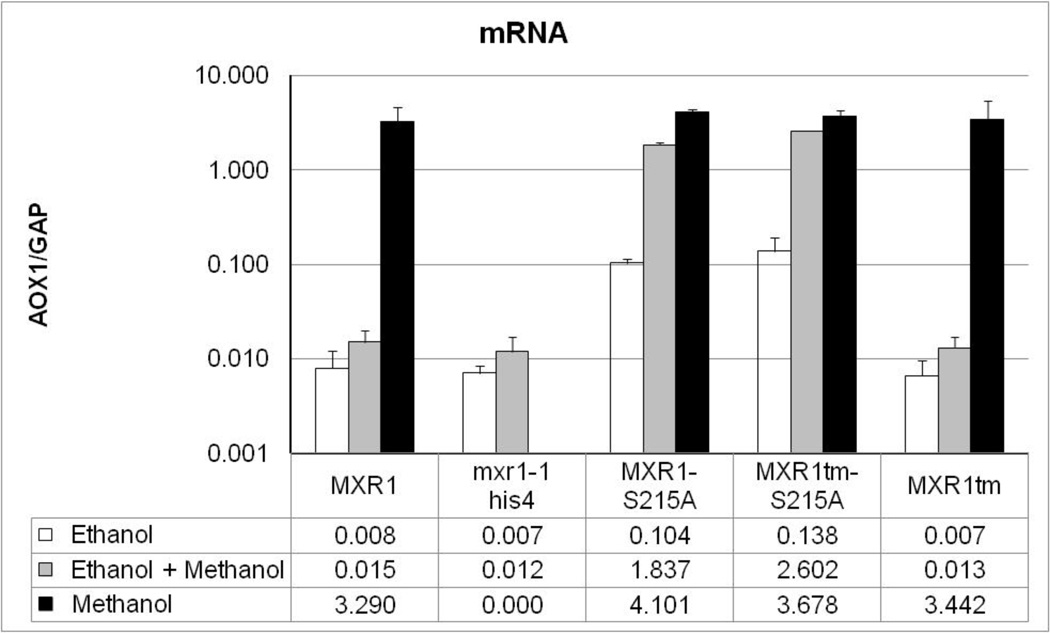

The N-terminal 400 amino acids of Mxr1 are sufficient for full transcriptional activity in P. pastoris

We have shown that the functions of Mxr1 required for activating transcription in S. cerevisiae are located within the N-terminal 400 amino acids of the protein. Because this region of Mxr1 also contains its DNA binding domain we could determine whether it is sufficient for activation of Mxr1 target genes in its natural host, P. pastoris. A plasmid carrying the MXR1 promoter followed by either the S215A mutant or wild type coding sequence truncated to amino acid 400 was introduced into the his4 gene of P. pastoris JC132 to create strain PPP2 (MXR1tm-S215A) and PPP3 (MXR1tm), respectively. These strains as well as a strain expressing the full-length wild type protein, JC100, a mxr1 null mutant strain, JC132, and a strain expressing the full-length Mxr1-S215A mutant protein, PPP1 were grown in repressing medium, 0.5% ethanol, inducing medium, 0.5% methanol, and repressing medium containing inducer, 0.5% ethanol and 0.5% methanol. Total RNA was isolated from each culture and AOX1 mRNA, as a measure of Mxr1 activity, was quantified using qRT-PCR. As shown in Fig 7, the truncated Mxr1 wild type (Mxr1tm-WT) and mutant (Mxr1tm-S215A) displayed a level of AOX1 expression comparable to that found in the full-length wild type and Mxr1-S215A mutant in inducing condition. Furthermore, both S215A mutants exhibited comparable levels of derepression of AOX1 expression in ethanol media upon disruption of the interaction with 14-3-3. These observations suggest that the N-terminal 400 amino acids of Mxr1 are sufficient to activate carbon source-dependent expression of Mxr1-dependent genes and provide in vivo evidence that the major activation domain identified in S. cerevisiae is functional in P. pastoris.

Fig 7.

Studies on expression of major Mxr1-dependent gene, AOX1 in P pastoris in response to different carbon sources. mRNA was extracted from strains JC100 (MXR1WT), JC132 (mxr1-1 his4), PPP1 (MXR1-S215A), PPP2 (MXR1tm-S215A) and PPP3 (MXR1tm) both in repressed (0.5% Ethanol) and induced (0.5% Methanol) as well as ethanol plus methanol growth conditions. Quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR) was performed to determine the levels of AOX1 mRNA. The mRNA levels were normalized to the levels of GAP mRNA in each sample. The error bars represent the mean of three biological replicates assayed in duplicate.

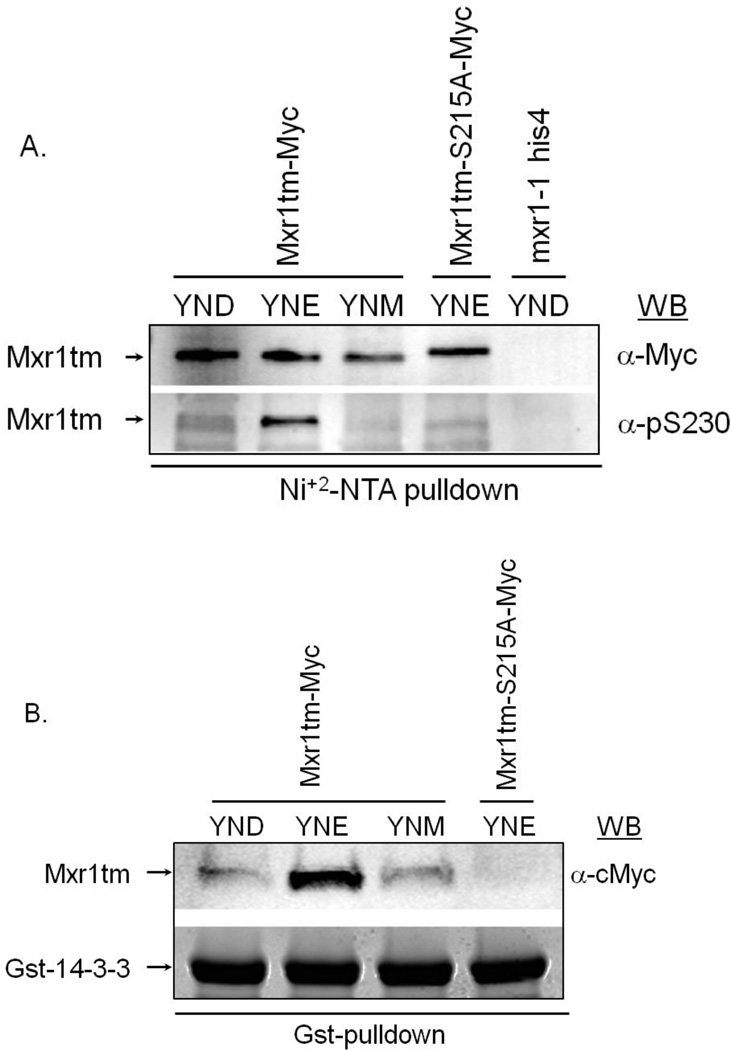

Carbon source-dependent phosphorylation of Ser215 and binding of 14-3-3 to Mxr1

The data just presented suggest that phosphorylation-dependent binding of 14-3-3 differentially regulates Mxr1 activity in response to various carbon sources. To examine whether phosphorylation of Ser215 and 14-3-3 binding are carbon source-regulated we performed Ni+2-NTA and Gst-pulldown assays using P. pastoris cell extracts containing C-terminal Myc-(His)6-tagged truncated Mxr1 (Mxr1tm, 1-400 amino acids) and E. coli expressed Gst-C4qzn3. We were unable to detect Mxr1 in the cell extracts either due to its very low level of expression or due to its highly unstable nature. To enrich the protein we performed Ni+2-pulldown using protein extracts from P. pastoris strain PPP3 (expressing Mxr1tm-Myc-His6) after growth in fully repressing medium containing either 0.5% glucose, or 0.5% ethanol; and inducing medium containing 0.5% methanol, PPP2 (expressing Mxr1tm-S215A-Myc-His6) after growth in 0.5% ethanol containing medium, and JC132, a mxr1-1 null mutant strain after growth in 0.5% glucose media. Pulldown fractions were immunoblotted with anti-Myc and anti-pSer230 antibody, as described before. As shown in Fig 8A Ser215-phosphorylation was diminished significantly in both glucose and methanol growth conditions compared to that observed in ethanol growth condition for wildtype protein. Phosphorylation of the Ser to Ala mutant was also significantly diminished. No protein band was observed corresponding to Mxr1tm for the mxr1-1 null mutant strain, confirming the specificity of the pulldown assay. A Gst-pulldown was done to test 14-3-3 binding to Mxr1 in different growth conditions using the same cell extracts (except the mxr1-1 null mutant extract). As shown in Fig 8B, 14-3-3 binding was also significantly impaired in glucose and methanol grown cells, and completely abolished due to the substitution of Ser to Ala even in ethanol growth media. These results are consistent with the phosphorylation data and together they suggest that Ser215-phosphorylation is regulated by the carbon source available for growth and this in turn regulates 14-3-3 binding to Mxr1. The result in glucose media was quite surprising and interesting. Despite the absence of 14-3-3 binding Mxr1-activated genes are completely repressed, suggesting the presence of a 14-3-3-independent pathway for the regulation of expression of Mxr1-dependent genes.

Fig 8.

A. Determination of phosphorylation of Mxr1-Ser215 in response to various carbon sources. Ni+2-pulldown was done using P. pastoris protein extract containing either truncated wildtype Mxr1(Mxr1tm-Myc-His6) prepared from cells grown in 0.5% glucose (YND), 0.5% ethanol (YNE) and 0.5% methanol (YNM) containing media, or truncated mutant Mxr1 (Mxr1tm-S215A-Myc-His6) prepared from cells grown in 0.5% ethanol (YNE) containing media, or extract prepared from mxr1-1 null mutant strain grown in 0.5% glucose containing media (YND). Pulldown fractions were electrophoresed in 4–20% SDS-PAGE and visualized by immunoblotting with anti-Myc and anti-pSer230 antibody. B. Interaction studies between Mxr1 and 14-3-3 in response to various carbon sources. Gst-pulldown was performed using the P. pastoris cell extracts and E. coli expressed Gst-C4qzn3 as described above. Pulldown fractions were electrophoresed in 4–20% SDS-PAGE and visualized by western blotting with anti-cMyc antibody.

14-3-3 acts at a post DNA binding step

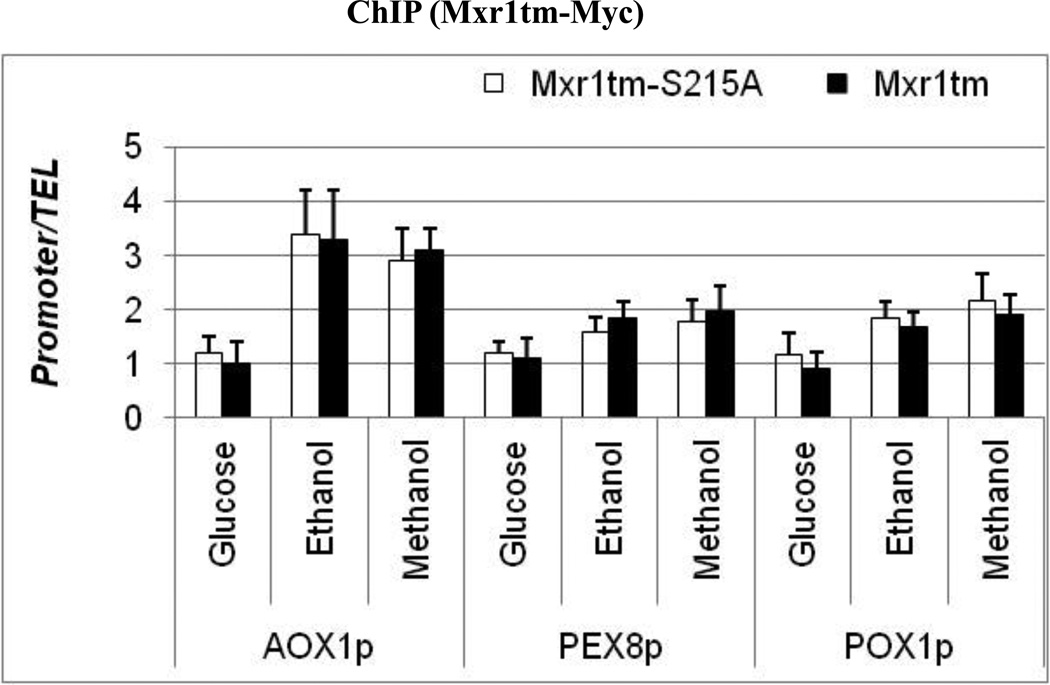

The ability of Mxr1 to activate transcription might be regulated at different steps in response to carbon source availability. These include nuclear localization, DNA-binding and post-DNA binding. 14-3-3 could regulate any of these steps. It has been reported that Mxr1 was mostly localized in the cytoplasm in glucose-grown cells and its nuclear localization was increased when cells were grown in ethanol, glycerol, and methanol containing media (Lin-Cereghino et al., 2006). Despite its localization in the nucleus Mxr1 activity remains repressed in glycerol and ethanol media and introduction of a mutation that disrupts its interaction with14-3-3- partially relieves the repression. These observations prompted us to test whether 14-3-3 inhibits DNA binding by Mxr1 in vivo. We performed chromatin immunoprecipitation using crosslinked protein extract containing either C-terminal Myc-tagged truncated wildtype (Mxr1tm) or S215A mutant variant (Mxr1tm-S215A). P. pastoris strains PPP2 (expressing Mxr1tm-S215A-Myc) and PPP3 (expressing Mxr1tm-Myc) were grown in 0.5% glucose, 0.5% ethanol, and 0.5% methanol-containing media. We tested carbon source-dependent Mxr1-binding to three Mxr1-activated gene promoters, AOX1prm, PEX8prm and POX1prm. As shown in Fig 9, binding of Mxr1 to these promoters was significantly increased both in ethanol- and methanol-grown cells compared to that observed in glucose grown cells, The binding of Mxr1 to these promoters was consistent with the expression level of the respective genes (Fig 4A–C). The low level of Mxr1 binding in the presence of glucose could be due to its reduced level of nuclear localization. Interestingly, there was a comparable level of binding of wildtype and mutant protein in both repressing (ethanol) and inducing (methanol) media, suggests that 14-3-3 does not act to regulate the DNA binding activity of Mxr1, indicating a post-DNA binding role of 14-3-3 in carbon source-dependent regulation of Mxr1 activity. Moreover our results also indicate that besides 14-3-3 other regulatory pathways, are also acting at a post-DNA binding step to regulate Mxr1-dependent gene expression in ethanol.

Fig 9.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation. Chromatin immunoprecipitation was done using crosslinked protein extract prepared either from strain PPP2 (MXR1tm-S215A) or PPP3 (MXR1tm) after growth in 0.5% glucose, 0.5% ethanol and 0.5% methanol containing media. Immunoprecipitaion was done using anti-cMyc antibody against C-terminal Myc-tagged truncated Mxr1 wildtype and mutant protein, Mxr1tm-Myc and Mxr1tm-S215A-Myc respectively. The data are expressed as binding (ChIP/input) for AOX1p, PEX8p and POX1p relative to ChIP/input at the TEL region used as a reference.

DISCUSSION

Expression of the methanol utilizing genes among methylotrophic yeasts (P. pastoris, H. polymorpha, C. boidinii and P. methanolica) is regulated differently in response to various carbon sources (Hartner & Glieder, 2006). Independent of the yeast species all of the MUT genes are strongly repressed either in the presence of glucose or ethanol and highly induced by methanol. Species-dependent regulation of their expression has been observed in growth media containing either glycerol or glycerol and methanol. The alcohol oxidase genes, AOX1 and AOX2 in P. pastoris are repressed in growth media containing either glycerol or glycerol and methanol whereas those genes in other methylotrophs are significantly derepressed by glycerol and induced to different levels upon addition of methanol. The differential response to mixed carbon sources suggests the existence of unknown species-specific regulatory machinery(s) for modulating their expression. The zinc-finger transcription factor, Mxr1 is essential for methanol utilization and peroxisome biogenesis in P. pastoris (Lin-Cereghino et al., 2006). The molecular mechanism(s) of carbon source-dependent inhibition and methanol-induced activation of Mxr1 is also unknown. Here we report that a P. pastoris 14-3-3 protein is involved in this carbon source-dependent regulation.

In the present study we have identified a highly conserved region of Mxr1, residues 212–225, which contains the core 14-3-3-binding region RRASFSA (Parua et al., 2010). As for Adr1, this putative 14-3-3-binding region of Mxr1 differs significantly from mammalian 14-3-3 motifs because it lacks the well-conserved Pro at the +2 position. We report here a previously uncharacterized 14-3-3 family protein in P. pastoris that has the ability to complement S. cerevisiae 14-3-3 functions and to interact with Mxr1 through the 14-3-3-binding motif at residues 212–225 via phosphorylation of Ser215, suggesting that 14-3-3 is a biologically relevant regulator of Mxr1 in P. pastoris. Consistent with this interpretation we have observed gene- and carbon source-specific regulation of Mxr1 activity in P. pastoris that was dependent on an intact, phosphorylatable 14-3-3 binding motif. Indeed we observed carbon source-dependent regulation of phosphorylation of Ser215 and consequent carbon source-dependent regulation of 14-3-3 binding to Mxr1, confirming the presence of 14-3-3-mediated regulation of Mxr1 activity in a carbon source-dependent way. Although we observed 14-3-3-mediated inhibition of expression of Mxr1-dependent genes involved in methanol assimilation pathways (AOX1 and DHAS) and peroxisome biogenesis (PEX8 and PEX14) in response to ethanol, there was no 14-3-3-dependent inhibition observed for the genes in glucose- and glycerol-containing media in P. pastoris. Ethanol and glucose have been shown to repress the MUT pathway genes via two distinct mechanisms (Parpinello et al., 1998, Sakai et al., 1987, Alamae & Liiv, 1998). Indeed our experimental observations suggest that there is a distinct 14-3-3-independent pathway in glucose-dependent regulation of Mxr1 activity, where nuclear localization could be the predominant pathway that might be regulated by a different mechanism. Based on our present observations we propose that 14-3-3 is a key factor in the mechanism of repression utilized by ethanol, but not by glucose. Chromatin immunoprecipitation results indicate that 14-3-3 might be functioning at a post-DNA binding step, where it could regulate either RNA polymerase II recruitment or pre-initiation complex formation, either by recruiting some repressor or by inhibiting the recruitment of some activating factors. Surprisingly, a different scenario was observed for β-oxidation pathway genes. They were expressed constitutively in ethanol medium essentially through an Mxr1-dependent pathway, although at lower levels than that observed in methanol. 14-3-3-mediated regulation of their expression was also observed in glucose and glycerol. This suggests that the Mxr1-dependent activation mechanism for expression of β-oxidation pathway genes is distinct from that of the MUT pathway genes. We propose that Mxr1 might be acting through and/or in conjunction with the Pip2/Oaf1 homologs of P. pastoris to regulate the expression of β-oxidation pathway genes as has been observed for Adr1 in S. cerevisiae (Biddick et al., 2008, Ratnakumar & Young, 2010, Gurvitz et al., 2000, Gurvitz et al., 2001).

We have mapped the location of the major activation domain of Mxr1 to residues 246–280. We have confirmed this mapping in P. pastoris by showing that full activity resides within the first 400 amino acids of Mxr1, which includes the N-terminally located DNA binding domain at residues 29–101. The amino acid sequence alignment in Figure 1 shows that the C-terminal end of the Mxr1 activation domain is in a position analogous to the location of the cryptic activation domain of Adr1 at residues 260–360 (Parua et al., 2010, Cook et al., 1994). Although the two amino acid sequences show no significant overall homology, they are both enriched in hydrophobic and acidic residues, a characteristic of canonical activation domains. Indeed, our mutational analyses indicate that the Phe residues at positions 249, 254 and 278 are important for Mxr1 activity. This is consistent with reports that hydrophobic residues are important for the activity of a number of other activation domains (Almlöf et al., 1997, Blair et al., 1994, Cress & Triezenberg, 1991, Drysdale et al., 1995, Folkers et al., 1995, Gill et al., 1994, Lin et al., 1994, Regier et al., 1993) including the major activation domain of Adr1 (Young et al., 1998) located at amino acids 420–462 (Cook et al., 1994, Young et al., 2002). The presence of the major activation domain of Mxr1 at a location analogous to the cryptic activation domain of Adr1 suggests that either Mxr1 has lost a second activation domain analogous to the Adr1 major activation domain or Adr1 has gained this domain.

Despite the presence of remarkable N-terminal sequence similarities between S. cerevisiae Adr1 and P. pastoris Mxr1, these proteins share no other regions of significant sequence similarity. Both proteins have similar but not identical regulatory features. Adr1 activates genes that are important for growth on non-fermentable carbon sources, for peroxisome biogenesis, and for β-oxidation of fatty acids (Ciriacy, 1979, Simon et al., 1992, Simon et al., 1995, Young et al., 2003, Sloan et al., 1999). Mxr1 activates genes responsible for methanol utilization, peroxisome biogenesis (Lin-Cereghino et al., 2006) and our present study suggests its involvement in the activation of β-oxidation pathway genes. A major difference in the gene regulation in which these factors participate is that distinct methanol-mediated induction and derepression mechanisms exist for Mxr1-regulated genes, while only derepression in the absence of induction has been reported for Adr1-dependent genes. The canonical Mxr1-regulated genes, AOX1 and DHAS, are repressed tightly by glucose, glycerol and ethanol, and highly induced by methanol in the absence of another carbon source (Cregg et al., 1989, Ellis et al., 1985, Koutz et al., 1989, Lin-Cereghino et al., 2006), while repression of the canonical Adr1-dependent gene, ADH2, is lifted by shifting the cells to growth on glycerol, ethanol or other non-fermentable carbon sources or upon glucose starvation (Ciriacy, 1975, Denis, 1987, Young et al., 2003).

Our studies suggest that phosphorylation-dependent 14-3-3 binding to a domain located between the DNA-binding domain and the major activation domain of Mxr1 and Adr1 plays an important role in regulating the activity of both transcription factors. This suggests that carbon source- and 14-3-3-dependent regulation of transcription factor activation domain function is conserved in fermentative yeast like S. cerevisiae and P. pastoris and may be present in other species containing analogous transcription factors. It will be interesting to determine whether 14-3-3 in the divergent yeasts regulates the activities of these transcription factors in a similar manner despite their lack of overall sequence conservation.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Yeast strains and growth of cultures

The S. cerevisiae strains used in this study are listed in Table 1. S. cerevisiae cultures were grown in either yeast extract peptone medium or in synthetic medium containing 2–5% glucose and lacking the appropriate amino acid or nucleotide for plasmid selection. To maintain selection for plasmids containing TRP1 and/or URA3 the synthetic selective medium contained 0.2% casamino acids rather than the standard dropout solution. All S. cerevisiae strains were grown at 30°C unless otherwise mentioned.

The P. pastoris strains used in this study are listed in Table 1. P. pastoris cells were cultured in either YPD medium (1.0% yeast extract, 2.0% peptone, 2.0% glucose) or minimal YNB medium (0.17% yeast nitrogen base without amino acids and 0.5% ammonium sulfate) supplemented with either 0.5% glucose (YND), 0.5% methanol (YNM), 0.5% glycerol (YNG), or 0.5% ethanol (YNE). Amino acids were added to 50 µg ml−1 when required. P. pastoris strains were grown at 30°C and transformations were done by using electro-transformation (Cregg & Russell, 1998).

Escherichia coli cells, mainly DH10β and BL21 (DE3) were cultured in Luria Bertani medium at 37°C for recombinant DNA techniques and protein overexpression.

Gene expression studies on different carbon sources

For gene expression studies in response to different carbon sources, cells were first grown in YND medium to an optical density at 600 nm (λ600) of approximately 0.5. These glucose-grown cells were centrifuged, washed with water and resuspended either in pre-warmed YNM, YNE, YNG, or YND supplemented with any other necessary ingredients. The cells were grown with vigorous shaking at 30°C for 8 to 10 hrs, and harvested by centrifugation and processed for RNA extraction.

Plasmid constructs

All MXR1 constructs were made by cloning the corresponding coding sequence into the TRP1-CEN4 vector, pOBD2 using gap repair methods(Orr-Weaver & Szostak, 1983, Szostak et al., 1983), where proteins were expressed as N-terminal GBD (Gal4 DNA binding domain)-fusion as described in Parua et al. (Parua et al., 2010). PCR fragments representing various regions of MXR1 were generated using forward and reverse primers that contained homology to the vector sequences flanking the polylinker region of pOBD2 as well as homology to MXR1. The NcoI and PvuII-digested pOBD2 plasmid (Uetz et al., 2000) and a PCR fragment were used to transform PJ69-4a to Trp+ prototrophy. Plasmid DNA from two or three Trp+ transformants was rescued and sequenced to confirm that recombination had produced the correct in-frame gene fusion using primers, OBDsF and OBDsR (See Supp. Table S1). Western analysis with an anti-Gal4 DBD monoclonal antibody (RK5C1, Santa Cruz Biotechnology) was used to confirm the synthesis of a fusion protein of the correct size. The primers used are listed in Supp. Table S1.

pGEX-3X-C4QZN3 and pBF-C4QZN3 were made by PCR amplifying C4qzn3 (Pichia pastoris 14-3-3) coding sequence from P. pastoris genomic DNA using C4QZN3_BamHI_F and C4QZN3_BamHI_R primers (See Supp. Table S1). BamHI-digested PCR fragment was then cloned into the BamHI site of pGEX-3X (GE Healthcare Life Sciences) to produce pGEX-3X-C4QZN3. pBF-C4QZN3 was generated by replacing BMH1 from pBF-BMH1 (a gift from S. Zheng; (Bertram et al., 1998)) with the above mentioned BamHI digested PCR product. Positive clones were checked by restriction digestion with BamHI and EcoRI and the sequence and directionality of the insert was tested by DNA sequencing analysis using sequencing primer GEX_sF for pGEX-3X-C4QZN3 and BF339_sF for pBF-C4QZN3 (Listed in Supp. Table S1).

All the plasmids used in this study are listed in Supp. Table S2.

Western blot

Western blot analyses were performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions for the Odyssey infrared imaging system (Licor Biosciences, Lincoln, NE), using 1:500 to 1:1,000 diluted monoclonal anti-GBD (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, RK5C1) or anti-Myc (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, 9E10) or polyclonal anti-Bmh2 (a gift from S. Lemmon) or anti-pSer230 (custom raised against Ser230-phosphorylated Adr1 sequence from BETHYL Laboratories, Inc.) antibody as primary antibodies and Licor λ800 secondary antibodies.

Preparation of protein extracts from yeast cells

Protein extracts from yeast cells were prepared following the procedure as described in Parua et al. (Parua et al., 2010). Typically 50–100 ml of yeast cell culture grown to an A600 of ~1 was used for protein extraction. Cells were collected by centrifugation at 1600 × g for 5†min at 4°C in a Sorvall RC3B-plus centrifuge, washed once with 15% glycerol containing 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF), and resuspended in an equal volume of ChIP (Chromatin immunoprecipitation) lysis buffer (50 mM HEPES-KOH, pH 7.5, 140 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1% Triton X-100, 0.1% sodium deoxycholate) containing protease (Sigma) and phosphatase inhibitors (Roche Applied Science). The cells were broken with glass beads in a Savant FP120 FastPrep machine with two disruption cycles of 45 sec at a speed setting of 4.0. The unbroken cells and debris were pelleted by centrifugation in a microcentrifuge at 13600 × g for 10 min. The clarified extract was collected in a fresh microcentrifuge tube containing 1mM PMSF and 1X phosphatase inhibitor and used in subsequent experiments.

GST-pulldown assays

The Gst-pulldown assays were done following the same protocol essentially as described in Parua et al. (Parua et al., 2010). GST-Bmh1 and P. pastoris Gst-14-3-3 fusion proteins were expressed from pGEX-3X-BMH1 and pGEX-3X-C4QZN3, respectively in E. coli BL21 (DE3). These fusion proteins were then immobilized on glutathione-sepharose 4B beads as described by the manufacturer (GE Healthcare Life Sciences). Pulldown assays were performed using 30–40 µg of sepharose 4B coupled Gst-fused proteins and yeast extract containing ~2 mg of total proteins in 1X PBST (Phosphate buffered saline containing 0.1 % Tween 40), 1X protease inhibitor and 1X phosphatase inhibitor. The suspension was incubated at 4°C for one hour with continuous nutation. The beads were then pelleted by centrifugation at 320 × g for 1 min, washed three times with 1XPBST and re-suspended in 60 µl of 2X LDS-NuPAGE sample buffer followed by boiling at 95°C for 5 min. Fractions collected at different steps of the pulldown assays were then analyzed by SDS-PAGE and western blotting.

Ni+2-NTA pulldown assays

Ni+2-NTA pulldown assays were done using P. pastoris cell extract expressing C-terminal His6-tagged truncated wildtype or S215A Mxr1 (encodes 1–400 amino acids) mutant. Yeast extract containing approximately 10 mg total protein was incubated with Ni+2-NTA beads at 4°C for one hour with continuous nutation in binding buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH. 8.0, 200 mM NaCl, 5% glycerol and 10 mM imidazole). The beads were then pelleted by centrifugation at 320 × g for 1 min, washed three times with wash buffer (same as binding buffer except 25 mM imidazole) and re-suspended in 2X LDS-NuPAGE sample buffer followed by boiling at 95°C for 5 min. Pulldown fractions collected were then analyzed by SDS-PAGE and western blotting.

mRNA isolation and qRT-PCR

mRNA was isolated from yeast strains grown in either repressing or inducing medium using the acid phenol method described in Collart and Oliviero, 2001 (Collart & Oliviero, 2001). Residual DNA in the RNA preparation was reduced by treatment with DNase I (Ambion) following the manufacturer’s recommendations. cDNA was synthesized using SuperScript III (Invitrogen) following the manufacturer’s protocol. Quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) was performed for measuring mRNA levels using diluted cDNA. A standard curve was generated with GAP primers and used to quantify the mRNA levels. Samples were prepared from biological triplicates and analyzed in duplicate.

β-galactosidase assays

β-galactosidase assays were performed as described by Guarente, 1983 (Guarente, 1983) after growing the cells at 30°C in selective medium containing 2–5% glucose to an A600 of approximately 1. The reported values in Miller units are the averages of three transformants.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP)

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) was performed as described in Biddick et al. (Biddick et al., 2008). In brief, cells from a 50 ml culture at an A600~1 were pelleted at 1600 × g at room temperature in a Sorvall RC3B-plus centrifuge and resuspended in 8.75 ml of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Ethylene glycol-bis (Succinimidylsuccinate) (EGS; Thermo Scientific; 21565) cross-linker dissolved in DMSO was added to a final concentration of 3 mM and the sample was swirled at room temperature for 45 min. The EGS cross-linked cells were pelleted at 1600 × g at room temperature and resuspended in 25 ml of 1X PBS supplemented with 1% formaldehyde. After shaking gently for 15 minutes at room temperature, 1.5 ml of 2.5 M glycine was added and the cells were pelleted. The cell pellet was washed once with 10 ml of tris-buffered saline (TBS) containing 125 mM glycine and once with 10 ml of TBS only. Protein extract was prepared as described above after resuspending the cells into ChIP lysis buffer containing protease and phosphatase inhibitor cocktail and the clarified extract was then used in subsequent immunopreciptation (IP) experiments. IP of ~6 mg of protein extract (Tachibana et al., 2007) was performed overnight with constant nutation at 4°C with anti-cMyc (9E10; Santa Cruz Sc40). After IP, 50 µl of Protein A-coated Mag Sepharose™ Xtra beads from GE Healthcare (Cat no. 28-9670-62) were added and nutation was continued for 1–2 hr at 4°C. After separating the beads, 10 µl of the supernatant was aliquot out and mixed with 140 µl of ChIP elution buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 1% SDS, 1 mM EDTA) for measuring the amount of input DNA. The beads were processed by washing twice with ChIP lysis buffer, twice with high salt ChIP lysis buffer (ChIP lysis buffer with 0.5 M NaCl), twice with ChIP wash buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 250 mM LiCl, 0.5% Noniodet-P40, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate), and twice with ChIP TE (10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 0.1 mM EDTA). The immunoprecipitated DNA bound to the beads was eluted at 65°C for 10 min with 150 µl elution buffer. The eluted and input DNA were incubated for 12–16 h at 65°C and then purified using a QIAquick PCR purification kit (QIAGEN) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The eluted and input DNA were diluted 20- and 100-fold, respectively, and quantification of specific sequences was performed by qPCR using Power SYBR Green master mix (Applied Biosystems) in a PTC-200 Thermocycler coupled to a Chromo 4 continuous fluorescence detector (MJ-Research). Opticon 3 software (MJ-Research) was used for the data analysis. Occupancy of a protein is expressed as fold-increase of the IP to input ratio of the amount of the specific amplicon for the gene sequence over the IP to input ratio corresponding to the amplicon for the telomeric sequence. Primers used for ChIP analysis are listed in Supp. Table S1.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health, GM26079 to ETY. We thank other members of the lab for stimulating discussions and especially Ken Dombek and Katherine Braun for significantly improving the manuscript, and Geoffrey P. Lin Cereghino for strains and plasmids and S. Zheng and S. Lemmon for plasmids and antibodies, respectively.

REFERENCES

- Aitken A. 14-3-3 proteins: a historic overview. Semin Cancer Biol. 2006;16:162–172. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2006.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alamae T, Liiv L. Glucose repression of maltase and methanol-oxidizing enzymes in the methylotrophic yeast Hansenula polymorpha: isolation and study of regulatory mutants. Folia Microbiol (Praha) 1998;43:443–452. doi: 10.1007/BF02820789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Almlöf T, Gustafsson JA, Wright AP. Role of hydrophobic amino acid clusters in the transactivation activity of the human glucocorticoid receptor. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1997;17:934–945. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.2.934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertram PG, Zeng C, Thorson J, Shaw AS, Zheng XF. The 14-3-3 proteins positively regulate rapamycin-sensitive signaling. Curr Biol. 1998;8:1259–1267. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(07)00535-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biddick RK, Law GL, Young ET. Adr1 and Cat8 mediate coactivator recruitment and chromatin remodeling at glucose-regulated genes. PLoS One. 2008;3:e1436. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blair WS, Bogerd HP, Madore SJ, Cullen BR. Mutational analysis of the transcription activation domain of RelA: identification of a highly synergistic minimal acidic activation module. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:7226–7234. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.11.7226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cereghino JL, Cregg JM. Heterologous protein expression in the methylotrophic yeast Pichia pastoris. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2000;24:45–66. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2000.tb00532.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciriacy M. Genetics of alcohol dehydrogenase in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. II. Two loci controlling synthesis of the glucose-repressible ADH II. Mol Gen Genet. 1975;138:157–164. doi: 10.1007/BF02428119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciriacy M. Isolation and characterization of further cis- and trans-acting regulatory elements involved in the synthesis of glucose-repressible alcohol dehydrogenase (ADHII) in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Gen Genet. 1979;176:427–431. doi: 10.1007/BF00333107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collart MA, Oliviero S. Preparation of yeast RNA. Curr Protoc Mol Biol. 2001;Chapter 13(Unit13):12. doi: 10.1002/0471142727.mb1312s23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook WJ, Chase D, Audino DC, Denis CL. Dissection of the ADR1 protein reveals multiple, functionally redundant activation domains interspersed with inhibitory regions: evidence for a repressor binding to the ADR1c region. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:629–640. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.1.629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cregg JM, Cereghino JL, Shi J, Higgins DR. Recombinant protein expression in Pichia pastoris. Mol Biotechnol. 2000;16:23–52. doi: 10.1385/MB:16:1:23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cregg JM, Madden KR. Development of the methylotrophic yeast, Pichia pastoris, as a host system for the production of foreign proteins. Dev. Ind. Microbiol. 1988;29:33–41. [Google Scholar]

- Cregg JM, Madden KR, Barringer KJ, Thill GP, Stillman CA. Functional characterization of the two alcohol oxidase genes from the yeast Pichia pastoris. Mol Cell Biol. 1989;9:1316–1323. doi: 10.1128/mcb.9.3.1316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cregg JM, Russell KA. Transformation. Methods Mol Biol. 1998;103:27–39. doi: 10.1385/0-89603-421-6:27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cregg JM, Shen S, Johnson M, Waterham HR. Classical genetic manipulation. Methods Mol Biol. 1998;103:17–26. doi: 10.1385/0-89603-421-6:17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cress WD, Triezenberg SJ. Critical structural elements of the VP16 transcriptional activation domain. Science. 1991;251:87–90. doi: 10.1126/science.1846049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denis CL. The effects of ADR1 and CCR1 gene dosage on the regulation of the glucose-repressible alcohol dehydrogenase from Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Gen Genet. 1987;208:101–106. doi: 10.1007/BF00330429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denis CL, Ciriacy M, Young ET. A positive regulatory gene is required for accumulation of the functional messenger RNA for the glucose-repressible alcohol dehydrogenase from Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Mol Biol. 1981;148:355–368. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(81)90181-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dombek KM, Kacherovsky N, Young ET. The Reg1-interacting proteins, Bmh1, Bmh2, Ssb1, and Ssb2, have roles in maintaining glucose repression in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:39165–39174. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M400433200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drysdale CM, Duenas E, Jackson BM, Reusser U, Braus GH, Hinnebusch AG. The transcriptional activator GCN4 contains multiple activation domains that are critically dependent on hydrophobic amino acids. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:1220–1233. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.3.1220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis SB, Brust PF, Koutz PJ, Waters AF, Harpold MM, Gingeras TR. Isolation of alcohol oxidase and two other methanol regulatable genes from the yeast Pichia pastoris. Mol Cell Biol. 1985;5:1111–1121. doi: 10.1128/mcb.5.5.1111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferl RJ, Manak MS, Reyes MF. The 14-3-3s. Genome Biol. 2002;3 doi: 10.1186/gb-2002-3-7-reviews3010. REVIEWS3301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folkers GE, van Heerde EC, van der Saag PT. Activation function 1 of retinoic acid receptor beta 2 is an acidic activator resembling VP16. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:23552–23559. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.40.23552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu H, Subramanian RR, Masters SC. 14-3-3 proteins: structure, function, and regulation. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2000;40:617–647. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.40.1.617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gellissen G. Heterologous protein production in methylotrophic yeasts. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2000;54:741–750. doi: 10.1007/s002530000464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gelperin D, Weigle J, Nelson K, Roseboom P, Irie K, Matsumoto K, Lemmon S. 14-3-3 proteins: potential roles in vesicular transport and Ras signaling in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92:11539–11543. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.25.11539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gill G, Pascal E, Tseng ZH, Tjian R. A glutamine-rich hydrophobic patch in transcription factor Sp1 contacts the dTAFII110 component of the Drosophila TFIID complex and mediates transcriptional activation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91:192–196. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.1.192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gould SJ, McCollum D, Spong AP, Heyman JA, Subramani S. Development of the yeast Pichia pastoris as a model organism for a genetic and molecular analysis of peroxisome assembly. Yeast. 1992;8:613–628. doi: 10.1002/yea.320080805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guarente L. Yeast promoters and lacZ fusions designed to study expression of cloned genes in yeast. Methods Enzymol. 1983;101:181–191. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(83)01013-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gurvitz A, Hiltunen JK, Erdmann R, Hamilton B, Hartig A, Ruis H, Rottensteiner H. Saccharomyces cerevisiae Adr1p governs fatty acid beta-oxidation and peroxisome proliferation by regulating POX1 and PEX11. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:31825–31830. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M105989200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gurvitz A, Wabnegger L, Rottensteiner H, Dawes IW, Hartig A, Ruis H, Hamilton B. Adr1p-dependent regulation of the oleic acid-inducible yeast gene SPS19 encoding the peroxisomal beta-oxidation auxiliary enzyme 2,4-dienoyl-CoA reductase. Mol Cell Biol Res Commun. 2000;4:81–89. doi: 10.1006/mcbr.2000.0261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartner FS, Glieder A. Regulation of methanol utilisation pathway genes in yeasts. Microb Cell Fact. 2006;5:39. doi: 10.1186/1475-2859-5-39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartner FS, Ruth C, Langenegger D, Johnson SN, Hyka P, Lin-Cereghino GP, Lin-Cereghino J, Kovar K, Cregg JM, Glieder A. Promoter library designed for fine-tuned gene expression in Pichia pastoris. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:e76. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartshorne TA, Blumberg H, Young ET. Sequence homology of the yeast regulatory protein ADR1 with Xenopus transcription factor TFIIIA. Nature. 1986;320:283–287. doi: 10.1038/320283a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ichimura T, Kubota H, Goma T, Mizushima N, Ohsumi Y, Iwago M, Kakiuchi K, Shekhar HU, Shinkawa T, Taoka M, Ito T, Isobe T. Transcriptomic and proteomic analysis of a 14-3-3-gene-deficient yeast. Biochemistry. 2004;43:6149–6158. doi: 10.1021/bi035421i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- James P, Halladay J, Craig EA. Genomic libraries and a host strain designed for highly efficient two-hybrid selection in yeast. Genetics. 1996;144:1425–1436. doi: 10.1093/genetics/144.4.1425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson MA, Waterham HR, Ksheminska GP, Fayura LR, Cereghino JL, Stasyk OV, Veenhuis M, Kulachkovsky AR, Sibirny AA, Cregg JM. Positive selection of novel peroxisome biogenesis-defective mutants of the yeast Pichia pastoris. Genetics. 1999;151:1379–1391. doi: 10.1093/genetics/151.4.1379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones DH, Ley S, Aitken A. Isoforms of 14-3-3 protein can form homo- and heterodimers in vivo and in vitro: implications for function as adapter proteins. FEBS Lett. 1995;368:55–58. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(95)00598-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koutz P, Davis GR, Stillman C, Barringer K, Cregg J, Thill G. Structural comparison of the Pichia pastoris alcohol oxidase genes. Yeast. 1989;5:167–177. doi: 10.1002/yea.320050306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kranthi BV, Kumar HR, Rangarajan PN. Identification of Mxr1p-binding sites in the promoters of genes encoding dihydroxyacetone synthase and peroxin 8 of the methylotrophic yeast Pichia pastoris. Yeast. 2010;27:705–711. doi: 10.1002/yea.1766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kranthi BV, Kumar R, Kumar NV, Rao DN, Rangarajan PN. Identification of key DNA elements involved in promoter recognition by Mxr1p, a master regulator of methanol utilization pathway in Pichia pastoris. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009;1789:460–468. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2009.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larkin MA, Blackshields G, Brown NP, Chenna R, McGettigan PA, McWilliam H, Valentin F, Wallace IM, Wilm A, Lopez R, Thompson JD, Gibson TJ, Higgins DG. Clustal W and Clustal X version 2.0. Bioinformatics. 2007;23:2947–2948. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin-Cereghino GP, Godfrey L, de la Cruz BJ, Johnson S, Khuongsathiene S, Tolstorukov I, Yan M, Lin-Cereghino J, Veenhuis M, Subramani S, Cregg JM. Mxr1p, a key regulator of the methanol utilization pathway and peroxisomal genes in Pichia pastoris. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26:883–897. doi: 10.1128/MCB.26.3.883-897.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin J, Chen J, Elenbaas B, Levine AJ. Several hydrophobic amino acids in the p53 amino-terminal domain are required for transcriptional activation, binding to mdm-2 and the adenovirus 5 E1B 55-kD protein. Genes Dev. 1994;8:1235–1246. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.10.1235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu H, Tan X, Veenhuis M, McCollum D, Cregg JM. An efficient screen for peroxisome-deficient mutants of Pichia pastoris. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:4943–4951. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.15.4943-4951.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lottersberger F, Rubert F, Baldo V, Lucchini G, Longhese MP. Functions of Saccharomyces cerevisiae 14-3-3 proteins in response to DNA damage and to DNA replication stress. Genetics. 2003;165:1717–1732. doi: 10.1093/genetics/165.4.1717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackintosh C. Dynamic interactions between 14-3-3 proteins and phosphoproteins regulate diverse cellular processes. Biochem J. 2004;381:329–342. doi: 10.1042/BJ20031332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayordomo I, Regelmann J, Horak J, Sanz P. Saccharomyces cerevisiae 14-3-3 proteins Bmh1 and Bmh2 participate in the process of catabolite inactivation of maltose permease. FEBS Lett. 2003;544:160–164. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(03)00498-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muslin AJ, Tanner JW, Allen PM, Shaw AS. Interaction of 14-3-3 with signaling proteins is mediated by the recognition of phosphoserine. Cell. 1996;84:889–897. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81067-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orr-Weaver TL, Szostak JW. Yeast recombination: the association between double-strand gap repair and crossing-over. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1983;80:4417–4421. doi: 10.1073/pnas.80.14.4417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parpinello G, Berardi E, Strabbioli R. A regulatory mutant of Hansenula polymorpha exhibiting methanol utilization metabolism and peroxisome proliferation in glucose. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:2958–2967. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.11.2958-2967.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parua PK, Ratnakumar S, Braun KA, Dombek KM, Arms E, Ryan PM, Young ET. 14-3-3 (Bmh) proteins inhibit transcription activation by Adr1 through direct binding to its regulatory domain. Mol Cell Biol. 2010;30:5273–5283. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00715-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ratnakumar S, Kacherovsky N, Arms E, Young ET. Snf1 controls the activity of adr1 through dephosphorylation of Ser230. Genetics. 2009;182:735–745. doi: 10.1534/genetics.109.103432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ratnakumar S, Young ET. Snf1 dependence of peroxisomal gene expression is mediated by Adr1. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:10703–10714. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.079848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Regier JL, Shen F, Triezenberg SJ. Pattern of aromatic and hydrophobic amino acids critical for one of two subdomains of the VP16 transcriptional activator. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90:883–887. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.3.883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakai Y, Rogi T, Takeuchi R, Kato N, Tani Y. Expression of Saccharomyces adenylate kinase gene in Candida boidinii under the regulation of its alcohol oxidase promoter. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 1995;42:860–864. doi: 10.1007/BF00191182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakai Y, Sawai T, Tani Y. Isolation and Characterization of a Catabolite Repression-Insensitive Mutant of a Methanol Yeast, Candida boidinii A5, Producing Alcohol Oxidase in Glucose-Containing Medium. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1987;53:1812–1818. doi: 10.1128/aem.53.8.1812-1818.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon M, Binder M, Adam G, Hartig A, Ruis H. Control of peroxisome proliferation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae by ADR1, SNF1 (CAT1, CCR1) and SNF4 (CAT3) Yeast. 1992;8:303–309. doi: 10.1002/yea.320080407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon MM, Pavlik P, Hartig A, Binder M, Ruis H, Cook WJ, Denis CL, Schanz B. A C-terminal region of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae transcription factor ADR1 plays an important role in the regulation of peroxisome proliferation by fatty acids. Mol Gen Genet. 1995;249:289–296. doi: 10.1007/BF00290529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sloan JS, Dombek KM, Young ET. Post-translational regulation of Adr1 activity is mediated by its DNA binding domain. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:37575–37582. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.53.37575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart MQ, Esposito RD, Gowani J, Goodman JM. Alcohol oxidase and dihydroxyacetone synthase, the abundant peroxisomal proteins of methylotrophic yeasts, assemble in different cellular compartments. J Cell Sci. 2001;114:2863–2868. doi: 10.1242/jcs.114.15.2863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Subramani S, Koller A, Snyder WB. Import of peroxisomal matrix and membrane proteins. Annu Rev Biochem. 2000;69:399–418. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.69.1.399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szostak JW, Orr-Weaver TL, Rothstein RJ, Stahl FW. The double-strand-break repair model for recombination. Cell. 1983;33:25–35. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(83)90331-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tachibana C, Biddick R, Law GL, Young ET. A poised initiation complex is activated by SNF1. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2007;282:37308–37315. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M707363200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tschopp JF, Brust PF, Cregg JM, Stillman CA, Gingeras TR. Expression of the lacZ gene from two methanol-regulated promoters in Pichia pastoris. Nucleic Acids Res. 1987;15:3859–3876. doi: 10.1093/nar/15.9.3859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uetz P, Giot L, Cagney G, Mansfield TA, Judson RS, Knight JR, Lockshon D, Narayan V, Srinivasan M, Pochart P, Qureshi-Emili A, Li Y, Godwin B, Conover D, Kalbfleisch T, Vijayadamodar G, Yang M, Johnston M, Fields S, Rothberg JM. A comprehensive analysis of protein-protein interactions in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Nature. 2000;403:623–627. doi: 10.1038/35001009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Heusden GP, Griffiths DJ, Ford JC, Chin AWTF, Schrader PA, Carr AM, Steensma HY. The 14-3-3 proteins encoded by the BMH1 and BMH2 genes are essential in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae and can be replaced by a plant homologue. Eur J Biochem. 1995;229:45–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Heusden GP, Steensma HY. Yeast 14-3-3 proteins. Yeast. 2006;23:159–171. doi: 10.1002/yea.1338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilker EW, Grant RA, Artim SC, Yaffe MB. A structural basis for 14-3-3sigma functional specificity. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:18891–18898. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M500982200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao B, Smerdon SJ, Jones DH, Dodson GG, Soneji Y, Aitken A, Gamblin SJ. Structure of a 14-3-3 protein and implications for coordination of multiple signalling pathways. Nature. 1995;376:188–191. doi: 10.1038/376188a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yaffe MB, Rittinger K, Volinia S, Caron PR, Aitken A, Leffers H, Gamblin SJ, Smerdon SJ, Cantley LC. The structural basis for 14-3-3:phosphopeptide binding specificity. Cell. 1997;91:961–971. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80487-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young ET, Dombek KM, Tachibana C, Ideker T. Multiple pathways are co-regulated by the protein kinase Snf1 and the transcription factors Adr1 and Cat8. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:26146–26158. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M301981200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young ET, Kacherovsky N, Van Riper K. Snf1 protein kinase regulates Adr1 binding to chromatin but not transcription activation. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:38095–38103. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M206158200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young ET, Saario J, Kacherovsky N, Chao A, Sloan JS, Dombek KM. Characterization of a p53-related activation domain in Adr1p that is sufficient for ADR1-dependent gene expression. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:32080–32087. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.48.32080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.