Abstract

Patients with extensive or complicated Crohn’s disease (CD) at diagnosis should be treated straightaway with immunosuppressive therapy according to the most recent guidelines. In patients with localized and uncomplicated CD at diagnosis, early use of immunosuppressive therapy is debated for preventing disease progression and limiting the disabling clinical impact. In this context, there is a need for predictors of benign or unfavourable subsequent clinical course, in order to avoid over-treating with risky drugs those patients who would have experienced spontaneous mid-term asymptomatic disease without progression towards irreversible intestinal lesions. At diagnosis, an age below 40 years, the presence of perianal lesions and the need for treating the first flare with steroids have been consistently associated with an unfavourable subsequent 5-year or 10-year clinical course. The positive predictive value of unfavourable course in patients with 2 or 3 predictors ranges between 0.75 and 0.95 in population-based and referral centre cohorts. Consequently, the use of these predictors can be integrated into the elements that influence individual decisions. In the CD postoperative context, keeping smoking and history of prior resection are the strongest predictors of disease symptomatic recurrence. However, these clinical predictors alone are not as reliable as severity of early postoperative endoscopic recurrence in clinical practice. In ulcerative colitis (UC), extensive colitis at diagnosis is associated with unfavourable clinical course in the first 5 to 10 years of the disease, and also with long-term colectomy and colorectal inflammation-associated colorectal cancer. In patients with extensive UC at diagnosis, a rapid step-up strategy aiming to achieve sustained deep remission should therefore be considered. At the moment, no reliable serological or genetic predictor of inflammatory bowel disease clinical course has been identified.

Keywords: Crohn’s disease, Ulcerative colitis, Inflammatory bowel diseases, Natural history, Predictors, Clinical practice

INTRODUCTION

The lifelong risk of developing inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) exceeds one percent in industrialized countries[1]. Such diseases are considered as chronic, with a small trend towards spontaneous long-term extinction in ulcerative colitis (UC)[2], but not in Crohn’s disease (CD)[3]. Despite an increasing use of immunosuppressive therapy, the long-term risk of intestinal resection and permanent ileostomy in CD is approximately 80% and 10%, respectively[1]. In UC, the actuarial risk of colectomy is about one percent per year in population-based cohorts of Northern Europe[4]. To reverse these unfavourable figures that have not significantly changed during the last five decades[5], the early use of aggressive therapy, such as the combination of thiopurines and anti-tumor necrosis factor (TNF) therapy[6], is considered both in CD and UC, with the aim of bringing patients into deep and sustained remission. However, some CD patients present at diagnosis with localized and uncomplicated (no perforation, no stricture) disease, and some UC patients present at diagnosis without disabling symptoms, biological abnormalities or severe endoscopic lesions. In those patients, the early and prolonged use of immunosuppressive therapy, with its associated risk of serious infections[7] and cancers[8,9], is questionable because the spontaneous evolution of the disease could have been benign. The risk of over-treating patients could be reduced in theory with the use of clinical, biological or endoscopic factors present at diagnosis and able to predict the subsequent course of IBD. In CD, there is also a need for predictors after complete resection of intestinal lesions when considering the postoperative preventive use of immunosuppressive therapy for limiting the risk of clinical recurrence. We review here the literature on clinical, serological and genetic predictors of IBD course, and discuss which predictors can be potentially useful in clinical practice.

CD

Clinical predictors of CD course

Prediction at diagnosis of unfavourable 5-year or 10-year clinical course: This question has been specifically studied in two referral centre cohorts[10,11] and two population-based cohorts[12-14], with fixed 5-year or 10-year study period and complete follow-up in most patients (Table 1). Markers of unfavourable CD course were either a single event (first clinical recurrence[14] or surgical operation[12,13]) or the presence of at least one element of a composite definition of disabling disease[10,11]. Whatever the definition, age below 40 years and presence of perianal disease at diagnosis were identified in most studies as predictors of subsequent unfavourable evolution. Need for steroids for treating the first flare and presence of upper gastrointestinal lesions were associated with a poor outcome in two studies. Finally, in two single studies, terminal ileal location and ileo-colonic lesions were predictive of first surgical operation and disabling disease, respectively. Of note, active smoking status, which is an established transient worsening factor of CD course[15,16], was not shown to be an independent predictor of unfavourable short and mid-term CD course in these studies.

Table 1.

Clinical predictors of unfavourable course of Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis

| Study | Cohort type | No. of patients | Definition or marker of unfavourable course | Independent predictors of unfavourable course, present at diagnosis |

| Crohn’s disease | ||||

| Within the first 5 yr after diagnosis | ||||

| Beaugerie et al[10], 2006 | Referral centre (Saint-Antoine) | 1188 | Disabling disease1 | Age < 40 yr Perianal disease Need for steroids for treating the first flare |

| Henriksen et al[12], 2007 | Population-based (IBSEN) | 200 | Intestinal resection within the study period | Upper gastrointestinal lesions |

| Loly et al[11], 2008 | Referral centre (Liège) | 361 | Disabling disease1 | Perianal disease Need for steroids for treating the first flare Ileo-colonic lesions |

| Within the first 10 yr after diagnosis | ||||

| Wolters et al[14], 2006 | Population-based (EC-IBD) | 358 | First recurrence | Upper gastrointestinal lesions Age < 40 yr |

| Solberg et al[13], 2007 | Population-based (IBSEN) | 197 | First surgical operation | Age < 40 yr Stricturing and penetrating behaviour2 (including perianal fistulas and abscesses) Terminal ileal location |

| Ulcerative colitis Within the first 5 yr after diagnosis | ||||

| Henriksen et al[12], 2007 | Population-based (IBSEN) | 454 | Relapse during the study period | Female gender Younger age |

| Within the first 10 yr after diagnosis | ||||

| Langholz et al[2], 1994 | Population-based (county of Copenhagen) | 1161 | Relapsing or chronic active course | Less systemic symptoms (fever, weight loss) |

| Colectomy | Extensive colitis High disease activity (including systemic symptoms) | |||

| Höie et al[56], 2007 | Population-based (EC-IBD) | 771 | Frequent relapse | Female gender Younger age Non-smoking status |

| Höie et al[57], 2007 | Population-based (EC-IBD) | 781 | Colectomy | Extensive colitis |

| Solberg et al[4], 2009 | Population-based (IBSEN) | 423 | Colectomy | Extensive colitis |

One or more of the following criteria: more than 2 steroid courses, steroid dependence, hospitalization for disease flare or complication, disabling chronic symptoms, need for immunosuppressive therapy, intestinal resection or surgical operation for surgical disease;

According to Vienna classification. IBSEN: A population-based inception cohort study; EC-IBD: European collaborative study group of inflammatory bowel disease.

Other studies: As a general feature, clinical predictors of unfavourable CD course identified in the above dedicated 5-year and 10-year studies have been confirmed in other studies with various design, follow-up time and endpoints. In the historical national cooperative CD study, perianal disease was an independent predictor of unfavourable outcome among 1084 patients[17]. In a Portuguese referral centre cohort testing CD outcome according to Vienna classification and other clinical markers, earlier age at diagnosis, penetrating lesions (including perianal fistulas and abscesses) and ileo-colonic location were associated with unfavourable outcome[18]. In the Olmstedt population-based study, young age was predictive of surgery, irrespective of smoking status[19]. In the Maastricht population-based cohort, young age, small bowel location and stricturing lesions were predictive of first surgery in 476 patients with a mean follow-up of 7 years[20]. In a referral centre population from Boston, early surgery (within 3 years of diagnosis) was associated with active smoking status, ileal location and need for early steroids in 345 patients followed for at least 3 years[21].

Whether childhood- and adult-onset CD courses differ in terms of severity has been recently questioned[22,23]. Patients with childhood-onset disease tend to have more extensive intestinal involvement, more active disease requiring more immunosuppressive therapy, and more rapid disease progression. By contrast, CD patients with a family history of IBD do not exhibit a more severe disease course in population-based studies[24] as well as in referral centre populations[12]. Finally, erythema nodosum and pyoderma gangrenosum, at diagnosis or later in the disease, are not predictive of more severe CD course[25].

Clinical predictors of long-term CD course: There are very scarce data on predictors of the long-term evolution of CD. In the Saint-Antoine cohort, predictors of 15-year CD course were characterized in 600 patients[1]. Non-severe evolution was defined as clinically inactive disease for greater than 12 years, less than one intestinal resection without permanent stoma and no death. Factors independently associated with a non-severe 15-year clinical course were non-smoking status, rectal sparing, high educational level, older age and longer disease duration.

Clinical predictors of postoperative recurrence: Literature on clinical predictors of postoperative recurrence is abundant and has been extensively reviewed recently[26-28]. In brief, postoperative active smoking status appears in most studies as a strong predictor of postoperative recurrence: the risk of clinical recurrence and re-operation is approximately doubled in smokers[29], with an increase in the risk according to the number of cigarettes smoked per day among smokers[30]. The other independent undisputed predictor of postoperative recurrence is a history of prior resection. The positive predictive value of penetrating disease behaviour, short disease duration prior to surgery, non-colonic disease location, long duration and extensive bowel resection has been evidenced less consistently. Finally, the roles of young age at onset and family history remain controversial.

Serological predictors of CD course

The search for serologic markers in IBD has led to the discovery of specific antibodies. Perinuclear anti-neutrophil antibody (pANCA) is associated with UC or UC-like CD whereas anti-Saccharomyces cerevisiae antibody (ASCA, glycan antibody) is mostly associated with CD[31,32]. Three other markers linked to immune response towards bacteria have been identified; antibodies to the Escherichia coli outer-membrane porin C (OmpC), the Pseudomonas fluorescens CD-related protein [anti-CD related bacterial sequence (I2)] and the CBir1 flagellin[33,34].

Many studies have been performed to assess the predictive value of these serological markers. Reactivity to ASCA, OmpC, anti-I2 and CBir1 has been associated with early disease onset CD, fibrostenosing and penetrating disease and need for early small bowel surgery[34-36]. In paediatric CD patients, baseline ASCA reactivity has been associated with earlier complications, relapsing disease and need for an additional surgery[37]. The frequency of disease complications increases with reactivity to increasing numbers of antigens (ASCA, anti-I2, anti-OmpC, and anti-CBir1)[38]. pANCA has been shown to be associated with less severe disease, UC-like disease and to be negatively associated with small bowel complication[36,39]. ASCA positivity has been associated with CD of the pouch after ileal pouch-anal anastomosis (IPAA)[40].

Genetic predictors of CD course

Before the era of genome-wide association studies, the role of genetic factors in IBD severity had been looked for by comparing familial and sporadic IBD. Although having a relative with IBD increases the risk for CD, the severity of CD is unaffected by family history[24]. A family history of CD increases the risk of subsequent CD after IPAA. Identifying genetic prognostic factors in IBD is a very attractive option as they are already present at the onset of the disease and actually even earlier. Their main advantage is their long-term stability, which is not the case for many other potential predictive factors such as clinical parameters or serologic markers. However, despite a growing number of identified susceptibility loci in both CD and UC[41], only very few have been associated with disease outcome. The presence of NOD2 polymorphism has been associated with a more aggressive clinical course of CD; i.e., higher risk of intestinal strictures, earlier need for first surgery and reduced postoperative disease-free interval[42-44]. Some studies have also tried to identify genetic factors associated with response to treatment. Polymorphisms in multi-drug resistant 1 (MDR1), TNF and migration inhibitory factor genes have been associated with corticosteroid refractoriness or sensitivity in CD and UC[45-47]. MDR1 polymorphism has also been associated with a higher risk of cyclosporine failure in patients with steroid-resistant UC[48]. The efficacy of infliximab is partly due to the induction of apoptosis in activated T lymphocytes. A research group in Leuven has analyzed infliximab-treated patients and found polymorphisms in apoptosis genes predicting response to infliximab therapy in luminal and fistulizing Crohn's disease[49]. Other studies suggest that genetic polymorphisms might be useful to predict anti-TNF therapeutic responsiveness in paediatric IBD[50].

Despite their attractiveness, genetic markers will probably never be able to fully predict IBD behaviour and complications, because of the major role of environmental factors in the disease pathogenesis. On the other hand, they could be associated with other factors, such as clinical or microbiological data, in order to build relevant composite predicting tools.

Relevance and potential use of predictors in CD

Saint-Antoine clinical predictors at diagnosis and early use of immunosuppressive therapy: In the Saint-Antoine cohort, patients were considered as having an unfavourable (“disabling”) clinical course in the first five years after diagnosis if they met at least one of the following criteria during the study period: more than 2 steroid courses, steroid dependence, hospitalization for disease flare or complication, disabling chronic symptoms, need for immunosuppressive therapy, intestinal resection or surgical operation for perianal disease. Among the 1123 patients studied, the rate of unfavourable course was 85%. By multivariate analysis, initial need for steroid use, age below 40 years and perianal disease at diagnosis were the three independent predictors of subsequent 5-year unfavourable course. The positive predictive value of unfavourable course in patients with two or three predictors was 0.91 and 0.93, respectively.

The Saint-Antoine clinical predictors are the only predictive factors that have been tested subsequently in independent population samples (Table 2). In a subsequent group of 302 patients from the Saint-Antoine centre, the positive predictive value of unfavourable course in patients with two or three predictors was 0.84 and 0.91, respectively[10]. The Saint-Antoine predictors were subsequently evaluated in two independent cohorts, using the same definition of unfavourable CD course as in the reference study. In the Liege referral population, the positive predictive value of unfavourable course in patients with two or three predictors was 0.67[11]. This rate was 0.74 in the Olmstedt population[51]. In conclusion, using the three Saint-Antoine predictors at diagnosis, the prediction of subsequent 5-year unfavourable CD course is accurate in more than two-thirds of patients from various populations. It is plausible that prediction accuracy holds true for the 5 to 10-year CD clinical course, since a strong homology has been demonstrated between the course pattern of CD in the first 3 years of the disease and the 7 subsequent years[3,52].

Table 2.

Validation of the positive predictive value of Saint-Antoine predictors

| Study | Cohort type | No. of patients | Prevalence of unfavourable course2 (%) | Positive predictive value of the presence of 2 or 3 predictors1 for predicting 5 yr unfavourable clinical course (%) |

| Reference study | ||||

| Beaugerie et al[10], 2006 | Saint-Antoine referral population | 1123 | 85.2 | 2 predictors: 91 3 predictors: 93 |

| Validating populations | ||||

| Beaugerie et al[10], 2006 | Independent subsequent sample of the Saint-Antoine referral population | 302 | 85.2 | 2 predictors: 84 3 predictors: 91 |

| Loly et al[11], 2008 | Liege referral population | 361 | 57.9 | 2 or 3 predictors: 67 |

| Beaugerie et al[62], 2009 | Population-based population (Olmstedt county) | 423 | 74.2 | 2 or 3 predictors: 74 |

Age < 40 years and perianal lesions at first presentation, need for steroids for treating the first flare;

Unfavourable clinical Crohn’s disease course (one or more of the following criteria: more than 2 steroid courses, steroid dependence, hospitalization for disease flare or complication, disabling chronic symptoms, need for immunosuppressive therapy, intestinal resection or surgical operation for surgical disease) within the 5 years following diagnosis.

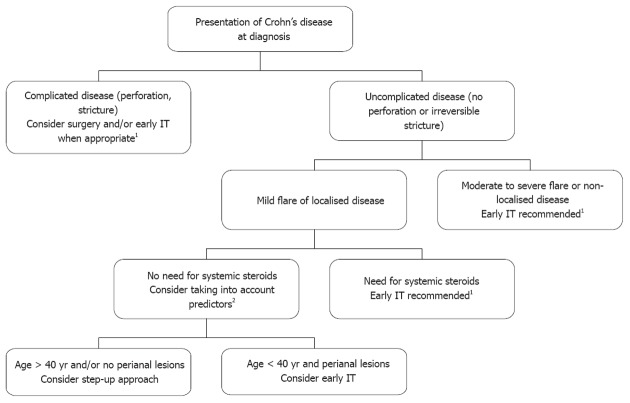

In the literature, the proportion of patients exhibiting unfavourable clinical course in the first 5 years of the disease, whatever the definition (disabling disease, frequent clinical relapses, chronic disabling symptoms, need for surgery, etc.) exceeds 50%, with an expected trend towards higher prevalence in referral centre cohorts than in population-based studies[53]. In clinical practice, patients presenting at diagnosis with irreversible penetrating or stricturing lesions, requiring (or not) immediate operation, can be considered as having complicated disease at diagnosis requiring early aggressive therapy (Figure 1). In the second recent European Crohn’s and Colitis Organisation (ECCO) CD consensus, patients with upper gastrointestinal lesions or extensive (> 100 cm) lesions at diagnosis are also considered as having severe disease at presentation which justifies immediate use of immunosuppressive therapy[54]. In the remaining patients, the need for treating moderate to severe flares with systemic steroids is increasingly considered as an indication for concurrent initiation of immunosuppressive therapy[54], taking into account, for instance, the high rate of recurrence within the year after steroid discontinuation[55]. Among the patients treated with systemic steroids from diagnosis, it must be noted that those who are younger than 40 years and/or have perianal lesions at diagnosis have ipso facto at least two predictors of unfavourable subsequent disease. Finally, patients with first disease flare not requiring systemic steroids often have localised[28] (< 30 cm) continuous intestinal disease with mild symptoms. In this context of true initial benign disease only, Saint-Antoine predictors may be helpful for the decision: in particular, young patients with perianal lesions could be considered for early immunosuppressive therapy, given the high risk of subsequent unfavourable course. However, if early immunosuppressive therapy is not decided on and if patients go rapidly into clinical remission, subclinical inflammatory lesions can now be monitored using blood C-reactive protein, magnetic resonance imaging and faecal calprotectin evaluations, limiting the risk of subclinical progression of intestinal lesions towards irreversible damage without appropriate change in maintenance treatment.

Figure 1.

Indication for early immunosuppressive therapy. Thiopurines and/or anti-tumor necrosis factor therapy, according to presentation of Crohn’s disease at diagnosis, 1European Crohn's and Colitis Organisation guidelines and 2Saint-Antoine predictors (2 or 3 of the following items at diagnosis are predictive for subsequent 5-year unfavourable course: Age < 40 years, need for systemic steroids and presence of perianal lesions). IT: Immunosuppressive therapy.

Clinical predictors at surgery of postoperative recurrence and choice of the postoperative maintenance treatment: After intestinal resection, all previous smokers are strongly encouraged to quit smoking. For guiding the choice of the immediate postoperative treatment, in the absence of a validated predictive index, the members of the ECCO consensus group have selected some of the predictors reported in the literature series[28]. In addition to the two undisputed predictors of early recurrence (keeping smoking and prior resection), penetrating disease behaviour, perianal disease and extensive small bowel resection have been proposed as risk factors. In patients with at least one risk factor, thiopurines are proposed as the drug of choice for preventing early recurrence. However, it is also recommended to perform during the first postoperative year an ileocolonoscopy in order to assess the presence and severity of endoscopic perianastomotic lesions. These endoscopic findings are unanimously considered as the gold standard predictor of subsequent clinical evolution[26,27], so that the definite choice of the postoperative prophylactic treatment should be based on the severity of endoscopic lesions[28]. As a consequence, the choice of immediate therapy based on (insufficiently) validated clinical predictors vs tailored treatment initiated according to endoscopic findings has a limited impact since, in all patients, the final choice of the mid-term prophylactic treatment is based on endoscopic findings.

UC

Clinical predictors of UC course

Prediction at diagnosis of unfavourable 5-year or 10-year clinical course: This question has been specifically studied in five population-based studies (Table 1)[2,4,12,56,57]. Young age at diagnosis and female gender were associated in two studies with a trend towards more frequent relapses[12,56]. Active smoking status was associated with reduced number of relapses within 10 years after diagnosis in one cohort only[56], but many other studies on the natural history have established the relationship between sustained non-smoking status and less active disease course[1], with reversion of this impact when resuming smoking[15]. However, of course, patients with UC are not encouraged to smoke. Finally, in the Danish cohort, a high level of systemic clinical symptoms at presentation (fever, weight loss) was associated at the same time with a trend towards infrequent relapses and chronic disease but higher risk of colectomy. Since proctocolectomy is no longer considered as the end of the medical problems in most operated patients, the risk of colectomy is a good marker of overall severity in patients with UC. Extensive colitis at presentation (defined as upper limit of macroscopic lesions proximal to the splenic flexure) has consistently been evidenced as an independent predictor of colectomy within the 10 years after diagnosis.

Serological and genetic predictors of UC course

Serological and genetic predictors have been far less studied in UC than in CD and only a few clinical settings have been investigated. As in CD, the severity of UC does not seem to be affected by family history of IBD[12,58]. In the pre-colectomy situation, high levels of pANCA have been associated with the risk of subsequent chronic pouchitis in UC patients undergoing IPAA[59]. pANCA might also be useful to predict response to anti-TNF therapy since negative status has been independently associated with early response to this treatment[60]. Some genetic factors might also be useful to predict response to treatment in the future. A recent study by a German group suggests that homozygous carriers of IBD risk-increasing IL23R variants are more likely to respond to infliximab than are homozygous carriers of IBD risk-decreasing IL23R variants[60]. It is also possible that a genetic scoring system taking into account several single nucleotide polymorphisms might be able to identify medically refractory UC patients[61]. As in CD, serological and genetic markers will probably be useful in future composite predicting tools.

Relevance and potential use of predictors in UC

Compared with CD, individual natural history of patients is harder to predict than in CD[1], and the clinical relevance of clinical predictors of 10-year UC severity has not been validated in independent cohorts. However, extensive colitis at diagnosis consistently appears as a predictor of subsequent colectomy. In addition, extensive colitis is strongly associated with the risk of long-term colorectal cancer[62,63], and persisting colonic mucosal inflammation (macroscopic[64] and microscopic[65]) also contribute independently to the risk. Finally, the IBSEN group also demonstrated that obtaining mucosal healing in the short-term in patients with UC is associated with a reduced risk of subsequent colectomy[66]. In this context, it is reasonable to suggest considering a more aggressive therapeutic strategy (for instance, faster step-up approach) in patients with extensive colitis at diagnosis.

In conclusion, at the moment no reliable genetic or serological predictor of IBD course can be used in clinical practice. Saint-Antoine clinical predictors of subsequent unfavourable CD course may be taken into account in the decision about early immunosuppressive therapy in selected patients, and extensive colitis at diagnosis should influence individual therapeutic strategy in UC. However, we are aiming now towards the primary therapeutic goal of obtaining sustained deep remission (including mucosal healing) rather than simple sustained clinical remission. Consequently, we will need to identify predictors at diagnosis of subsequent sustained deep remission. Given the growing research in genetics and pharmacogenomics, we can imagine that sensitive and reliable predictors will be available in the near future.

Footnotes

Peer reviewer: Dr. Akira Andoh, Internal Medicine, Shiga University of Medical Science, Seta Tukinowa, Otsu 520-2192, Japan

S- Editor Gou SX L- Editor Logan S E- Editor Li JY

References

- 1.Cosnes J, Gower-Rousseau C, Seksik P, Cortot A. Epidemiology and natural history of inflammatory bowel diseases. Gastroenterology. 2011;140:1785–1794. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.01.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Langholz E, Munkholm P, Davidsen M, Binder V. Course of ulcerative colitis: analysis of changes in disease activity over years. Gastroenterology. 1994;107:3–11. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(94)90054-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Munkholm P, Langholz E, Davidsen M, Binder V. Disease activity courses in a regional cohort of Crohn’s disease patients. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1995;30:699–706. doi: 10.3109/00365529509096316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Solberg IC, Lygren I, Jahnsen J, Aadland E, Høie O, Cvancarova M, Bernklev T, Henriksen M, Sauar J, Vatn MH, et al. Clinical course during the first 10 years of ulcerative colitis: results from a population-based inception cohort (IBSEN Study) Scand J Gastroenterol. 2009;44:431–440. doi: 10.1080/00365520802600961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jess T, Riis L, Vind I, Winther KV, Borg S, Binder V, Langholz E, Thomsen OØ, Munkholm P. Changes in clinical characteristics, course, and prognosis of inflammatory bowel disease during the last 5 decades: a population-based study from Copenhagen, Denmark. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2007;13:481–489. doi: 10.1002/ibd.20036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Colombel JF, Sandborn WJ, Reinisch W, Mantzaris GJ, Kornbluth A, Rachmilewitz D, Lichtiger S, D’Haens G, Diamond RH, Broussard DL, et al. Infliximab, azathioprine, or combination therapy for Crohn’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1383–1395. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0904492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lichtenstein GR, Feagan BG, Cohen RD, Salzberg BA, Diamond RH, Chen DM, Pritchard ML, Sandborn WJ. Serious infections and mortality in association with therapies for Crohn’s disease: TREAT registry. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;4:621–630. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2006.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Beaugerie L, Brousse N, Bouvier AM, Colombel JF, Lémann M, Cosnes J, Hébuterne X, Cortot A, Bouhnik Y, Gendre JP, et al. Lymphoproliferative disorders in patients receiving thiopurines for inflammatory bowel disease: a prospective observational cohort study. Lancet. 2009;374:1617–1625. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61302-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Peyrin-Biroulet L, Khosrotehrani K, Carrat F, Bouvier AM, Chevaux JB, Simon T, Carbonnel F, Colombel JF, Dupas JL, Godeberge P, et al. Increased risk for nonmelanoma skin cancers in patients who receive thiopurines for inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 2011;141:1621–1628.e1-5. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.06.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Beaugerie L, Seksik P, Nion-Larmurier I, Gendre JP, Cosnes J. Predictors of Crohn’s disease. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:650–656. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Loly C, Belaiche J, Louis E. Predictors of severe Crohn’s disease. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2008;43:948–954. doi: 10.1080/00365520801957149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Henriksen M, Jahnsen J, Lygren I, Vatn MH, Moum B. Are there any differences in phenotype or disease course between familial and sporadic cases of inflammatory bowel disease? Results of a population-based follow-up study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:1955–1963. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01368.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Solberg IC, Vatn MH, Høie O, Stray N, Sauar J, Jahnsen J, Moum B, Lygren I. Clinical course in Crohn’s disease: results of a Norwegian population-based ten-year follow-up study. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;5:1430–1438. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2007.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wolters FL, Russel MG, Sijbrandij J, Ambergen T, Odes S, Riis L, Langholz E, Politi P, Qasim A, Koutroubakis I, et al. Phenotype at diagnosis predicts recurrence rates in Crohn’s disease. Gut. 2006;55:1124–1130. doi: 10.1136/gut.2005.084061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Beaugerie L, Massot N, Carbonnel F, Cattan S, Gendre JP, Cosnes J. Impact of cessation of smoking on the course of ulcerative colitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:2113–2116. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.03944.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cosnes J, Carbonnel F, Beaugerie L, Le Quintrec Y, Gendre JP. Effects of cigarette smoking on the long-term course of Crohn’s disease. Gastroenterology. 1996;110:424–431. doi: 10.1053/gast.1996.v110.pm8566589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mekhjian HS, Switz DM, Melnyk CS, Rankin GB, Brooks RK. Clinical features and natural history of Crohn’s disease. Gastroenterology. 1979;77:898–906. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Veloso FT, Ferreira JT, Barros L, Almeida S. Clinical outcome of Crohn’s disease: analysis according to the vienna classification and clinical activity. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2001;7:306–313. doi: 10.1097/00054725-200111000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jess T, Loftus EV, Velayos FS, Winther KV, Tremaine WJ, Zinsmeister AR, Scott Harmsen W, Langholz E, Binder V, Munkholm P, et al. Risk factors for colorectal neoplasia in inflammatory bowel disease: a nested case-control study from Copenhagen county, Denmark and Olmsted county, Minnesota. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:829–836. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01070.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Romberg-Camps MJ, Dagnelie PC, Kester AD, Hesselink-van de Kruijs MA, Cilissen M, Engels LG, Van Deursen C, Hameeteman WH, Wolters FL, Russel MG, et al. Influence of phenotype at diagnosis and of other potential prognostic factors on the course of inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:371–383. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2008.38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sands BE, Arsenault JE, Rosen MJ, Alsahli M, Bailen L, Banks P, Bensen S, Bousvaros A, Cave D, Cooley JS, et al. Risk of early surgery for Crohn’s disease: implications for early treatment strategies. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:2712–2718. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2003.08674.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pigneur B, Seksik P, Viola S, Viala J, Beaugerie L, Girardet JP, Ruemmele FM, Cosnes J. Natural history of Crohn’s disease: comparison between childhood- and adult-onset disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2010;16:953–961. doi: 10.1002/ibd.21152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Van Limbergen J, Russell RK, Nimmo ER, Drummond HE, Smith L, Davies G, Anderson NH, Gillett PM, McGrogan P, Hassan K, et al. IL23R Arg381Gln is associated with childhood onset inflammatory bowel disease in Scotland. Gut. 2007;56:1173–1174. doi: 10.1136/gut.2007.122069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Carbonnel F, Macaigne G, Beaugerie L, Gendre JP, Cosnes J. Crohn’s disease severity in familial and sporadic cases. Gut. 1999;44:91–95. doi: 10.1136/gut.44.1.91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Farhi D, Cosnes J, Zizi N, Chosidow O, Seksik P, Beaugerie L, Aractingi S, Khosrotehrani K. Significance of erythema nodosum and pyoderma gangrenosum in inflammatory bowel diseases: a cohort study of 2402 patients. Medicine (Baltimore) 2008;87:281–293. doi: 10.1097/MD.0b013e318187cc9c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.De Cruz P, Kamm MA, Prideaux L, Allen PB, Desmond PV. Postoperative recurrent luminal Crohn’s disease: a systematic review. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2012;18:758–777. doi: 10.1002/ibd.21825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Spinelli A, Sacchi M, Fiorino G, Danese S, Montorsi M. Risk of postoperative recurrence and postoperative management of Crohn’s disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2011;17:3213–3219. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v17.i27.3213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Travis SP, Stange EF, Lémann M, Oresland T, Chowers Y, Forbes A, D’Haens G, Kitis G, Cortot A, Prantera C, et al. European evidence based consensus on the diagnosis and management of Crohn’s disease: current management. Gut. 2006;55 Suppl 1:i16–i35. doi: 10.1136/gut.2005.081950b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Faubion WA, Loftus EV, Sandborn WJ, Freese DK, Perrault J. Pediatric “PSC-IBD”: a descriptive report of associated inflammatory bowel disease among pediatric patients with psc. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2001;33:296–300. doi: 10.1097/00005176-200109000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yamamoto T, Keighley MR. Smoking and disease recurrence after operation for Crohn’s disease. Br J Surg. 2000;87:398–404. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2168.2000.01443.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Quinton JF, Sendid B, Reumaux D, Duthilleul P, Cortot A, Grandbastien B, Charrier G, Targan SR, Colombel JF, Poulain D. Anti-Saccharomyces cerevisiae mannan antibodies combined with antineutrophil cytoplasmic autoantibodies in inflammatory bowel disease: prevalence and diagnostic role. Gut. 1998;42:788–791. doi: 10.1136/gut.42.6.788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ruemmele FM, Targan SR, Levy G, Dubinsky M, Braun J, Seidman EG. Diagnostic accuracy of serological assays in pediatric inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 1998;115:822–829. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(98)70252-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Landers CJ, Cohavy O, Misra R, Yang H, Lin YC, Braun J, Targan SR. Selected loss of tolerance evidenced by Crohn’s disease-associated immune responses to auto- and microbial antigens. Gastroenterology. 2002;123:689–699. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.35379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Targan SR, Landers CJ, Yang H, Lodes MJ, Cong Y, Papadakis KA, Vasiliauskas E, Elson CO, Hershberg RM. Antibodies to CBir1 flagellin define a unique response that is associated independently with complicated Crohn’s disease. Gastroenterology. 2005;128:2020–2028. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.03.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Arnott ID, Landers CJ, Nimmo EJ, Drummond HE, Smith BK, Targan SR, Satsangi J. Sero-reactivity to microbial components in Crohn’s disease is associated with disease severity and progression, but not NOD2/CARD15 genotype. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:2376–2384. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2004.40417.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vasiliauskas EA, Kam LY, Karp LC, Gaiennie J, Yang H, Targan SR. Marker antibody expression stratifies Crohn’s disease into immunologically homogeneous subgroups with distinct clinical characteristics. Gut. 2000;47:487–496. doi: 10.1136/gut.47.4.487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Amre DK, Lambrette P, Law L, Krupoves A, Chotard V, Costea F, Grimard G, Israel D, Mack D, Seidman EG. Investigating the hygiene hypothesis as a risk factor in pediatric onset Crohn’s disease: a case-control study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:1005–1011. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00526.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dubinsky M. What is the role of serological markers in IBD? Pediatric and adult data. Dig Dis. 2009;27:259–268. doi: 10.1159/000228559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vasiliauskas EA, Plevy SE, Landers CJ, Binder SW, Ferguson DM, Yang H, Rotter JI, Vidrich A, Targan SR. Perinuclear antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies in patients with Crohn’s disease define a clinical subgroup. Gastroenterology. 1996;110:1810–1819. doi: 10.1053/gast.1996.v110.pm8964407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Melmed GY, Fleshner PR, Bardakcioglu O, Ippoliti A, Vasiliauskas EA, Papadakis KA, Dubinsky M, Landers C, Rotter JI, Targan SR. Family history and serology predict Crohn’s disease after ileal pouch-anal anastomosis for ulcerative colitis. Dis Colon Rectum. 2008;51:100–108. doi: 10.1007/s10350-007-9158-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Khor B, Gardet A, Xavier RJ. Genetics and pathogenesis of inflammatory bowel disease. Nature. 2011;474:307–317. doi: 10.1038/nature10209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Abreu MT, Taylor KD, Lin YC, Hang T, Gaiennie J, Landers CJ, Vasiliauskas EA, Kam LY, Rojany M, Papadakis KA, et al. Mutations in NOD2 are associated with fibrostenosing disease in patients with Crohn’s disease. Gastroenterology. 2002;123:679–688. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.35393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Alvarez-Lobos M, Arostegui JI, Sans M, Tassies D, Plaza S, Delgado S, Lacy AM, Pique JM, Yagüe J, Panés J. Crohn’s disease patients carrying Nod2/CARD15 gene variants have an increased and early need for first surgery due to stricturing disease and higher rate of surgical recurrence. Ann Surg. 2005;242:693–700. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000186173.14696.ea. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Renda MC, Cottone M. Prevalence of CARD15/NOD2 mutations in the Sicilian population. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:248–249. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01562_10.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cucchiara S, Latiano A, Palmieri O, Canani RB, D’Incà R, Guariso G, Vieni G, De Venuto D, Riegler G, De’Angelis GL, et al. Polymorphisms of tumor necrosis factor-alpha but not MDR1 influence response to medical therapy in pediatric-onset inflammatory bowel disease. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2007;44:171–179. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e31802c41f3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Farrell RJ, Kelleher D. Glucocorticoid resistance in inflammatory bowel disease. J Endocrinol. 2003;178:339–346. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.1780339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Potocnik U, Ferkolj I, Glavac D, Dean M. Polymorphisms in multidrug resistance 1 (MDR1) gene are associated with refractory Crohn disease and ulcerative colitis. Genes Immun. 2004;5:530–539. doi: 10.1038/sj.gene.6364123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Daniel F, Loriot MA, Seksik P, Cosnes J, Gornet JM, Lémann M, Fein F, Vernier-Massouille G, De Vos M, Boureille A, et al. Multidrug resistance gene-1 polymorphisms and resistance to cyclosporine A in patients with steroid resistant ulcerative colitis. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2007;13:19–23. doi: 10.1002/ibd.20046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hlavaty T, Pierik M, Henckaerts L, Ferrante M, Joossens S, van Schuerbeek N, Noman M, Rutgeerts P, Vermeire S. Polymorphisms in apoptosis genes predict response to infliximab therapy in luminal and fistulizing Crohn’s disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2005;22:613–626. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2005.02635.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Dubinsky MC, Mei L, Friedman M, Dhere T, Haritunians T, Hakonarson H, Kim C, Glessner J, Targan SR, McGovern DP, et al. Genome wide association (GWA) predictors of anti-TNFalpha therapeutic responsiveness in pediatric inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2010;16:1357–1366. doi: 10.1002/ibd.21174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Seksik P, Loftus EV, Beaugerie L, Harmsen WS, Zinsmeister AR, Cosnes J, Sandborn WJ. Validation of predictors of 5-year disabling CD in a population-based cohort from Olmsted County, Minnesota, 1983-1996. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:A17. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Beaugerie L, Le Quintrec Y, Paris JC, Godchaux JM, Saint-Raymond A, Schmitz J, Ricour C, Haddak M, Diday E. Testing for course patterns in Crohn’s disease using clustering analysis. Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 1989;13:1036–1041. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zankel E, Rogler G, Andus T, Reng CM, Schölmerich J, Timmer A. Crohn’s disease patient characteristics in a tertiary referral center: comparison with patients from a population-based cohort. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;17:395–401. doi: 10.1097/00042737-200504000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Dignass A, Van Assche G, Lindsay JO, Lémann M, Söderholm J, Colombel JF, Danese S, D’Hoore A, Gassull M, Gomollón F, et al. The second European evidence-based Consensus on the diagnosis and management of Crohn’s disease: Current management. J Crohns Colitis. 2010;4:28–62. doi: 10.1016/j.crohns.2009.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bouhnik Y, Lémann M, Mary JY, Scemama G, Taï R, Matuchansky C, Modigliani R, Rambaud JC. Long-term follow-up of patients with Crohn’s disease treated with azathioprine or 6-mercaptopurine. Lancet. 1996;347:215–219. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(96)90402-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Höie O, Wolters F, Riis L, Aamodt G, Solberg C, Bernklev T, Odes S, Mouzas IA, Beltrami M, Langholz E, et al. Ulcerative colitis: patient characteristics may predict 10-yr disease recurrence in a European-wide population-based cohort. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:1692–1701. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01265.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Höie O, Wolters FL, Riis L, Bernklev T, Aamodt G, Clofent J, Tsianos E, Beltrami M, Odes S, Munkholm P, et al. Low colectomy rates in ulcerative colitis in an unselected European cohort followed for 10 years. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:507–515. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Roth LS, Chande N, Ponich T, Roth ML, Gregor J. Predictors of disease severity in ulcerative colitis patients from Southwestern Ontario. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16:232–236. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v16.i2.232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Fleshner PR, Vasiliauskas EA, Kam LY, Fleshner NE, Gaiennie J, Abreu-Martin MT, Targan SR. High level perinuclear antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (pANCA) in ulcerative colitis patients before colectomy predicts the development of chronic pouchitis after ileal pouch-anal anastomosis. Gut. 2001;49:671–677. doi: 10.1136/gut.49.5.671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Jürgens M, Laubender RP, Hartl F, Weidinger M, Seiderer J, Wagner J, Wetzke M, Beigel F, Pfennig S, Stallhofer J, et al. Disease activity, ANCA, and IL23R genotype status determine early response to infliximab in patients with ulcerative colitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:1811–1819. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2010.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Haritunians T, Taylor KD, Targan SR, Dubinsky M, Ippoliti A, Kwon S, Guo X, Melmed GY, Berel D, Mengesha E, et al. Genetic predictors of medically refractory ulcerative colitis. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2010;16:1830–1840. doi: 10.1002/ibd.21293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Beaugerie L, Seksik P, Bouvier AM, Carbonnel F, Colombel JF, Faivre J. Thiopurine Therapy Is Associated with a Three-Fold Decrease in the Incidence of Advanced Colorectal Neoplasia in IBD Patients with Longstanding Extensive Colitis: Results from the CESAME Cohort. Gastroenterology. 2009;136:A–54. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ekbom A, Helmick C, Zack M, Adami HO. Ulcerative colitis and colorectal cancer. A population-based study. N Engl J Med. 1990;323:1228–1233. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199011013231802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Rutter MD, Saunders BP, Wilkinson KH, Rumbles S, Schofield G, Kamm MA, Williams CB, Price AB, Talbot IC, Forbes A. Thirty-year analysis of a colonoscopic surveillance program for neoplasia in ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:1030–1038. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.12.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Gupta N, Bostrom AG, Kirschner BS, Ferry GD, Winter HS, Baldassano RN, Gold BD, Abramson O, Smith T, Cohen SA, et al. Gender differences in presentation and course of disease in pediatric patients with Crohn disease. Pediatrics. 2007;120:e1418–e1425. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-0905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Frøslie KF, Jahnsen J, Moum BA, Vatn MH. Mucosal healing in inflammatory bowel disease: results from a Norwegian population-based cohort. Gastroenterology. 2007;133:412–422. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.05.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]