Summary

Introduction

This cross-sectional study was conducted to assess the relationship between iron levels in the plasma and sputum of cystic fibrosis (CF) patients. Methods: Demographic, clinical, and iron-related laboratory data were prospectively obtained from 25 patients with stable clinical features and 14 patientswith worsened clinical features since their most recent evaluations.

Results

Compared to patients with stable clinical features, those who experienced clinical deterioration demonstrated significantly worse lung function and were more frequently malnourished and diabetic. Members of the latter group were also significantly more hypoferremic and had higher sputum iron content than patients with stable clinical features. No significant correlation was found between plasma and sputum iron levels when the groups were analyzed together and separately.

Conclusions

Sputum iron content does not correlate with iron-related hematologic tests. Hypoferremia is common in CF and correlates with poor lung function and overall health.

Keywords: cystic fibrosis, iron, hypoferremia, serum, sputum, chelator

INTRODUCTION

Respiratory tract colonization with Pseudomonas aeruginosa (PA) remains an early and persistent phenomenon in cystic fibrosis (CF) despite aggressive antibiotic treatment.1,2 Therapy with systemic and inhaled antibiotics to treat PA is often transiently effective, but relapse is nearly inevitable with roughly 90% of mortality due to PA infection and its sequelae.3

Complex host–pathogen interactions underlie the morbidity imparted by PA infection. PA flourishes within the hypoxic microenvironments of bronchial mucus plugs that enhance the development of PA biofilms and in turn confer resistance to antibiotics.4 Recent experiments using a co-culture system of ΔF508-CFTR epithelial cells and PA have demonstrated that the ΔF508 mutation in CFTR enhances PA biofilm formation through increased iron availability in airway surface liquid.5,6 Moreover, the role of iron in promoting PA growth and drug-resistant biofilm formation in CF is supported by in vitro and clinical studies associating levels of iron in airway secretions with PA burden and disease acuity.7,8 These observations provide compelling evidence for a link between enhanced iron release into the CF airway and PA pathogenicity.

Despite reports of hypoferremia in CF9–11 and associations between elevated sputum iron content and lung function impairment,7,8,12 the relationship between circulatory and airway iron status is poorly understood. Thus, the present study was undertaken to compare these parameters and to assess whether they correlate with clinically relevant metrics.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study Enrollment and Definitions

This prospective, cross-sectional study was performed at a single CF center from February 2009 to December 2009. Confirmatory CFTR gene mutation analysis was available for 37 of 39 (95%) study participants. Designations of clinical stability and deterioration were based on the absence or presence, respectively, of one or more of the following features since a subject's most recent evaluation: increased cough frequency or severity, increased dyspnea, increased sputum expectoration, fever, diaphoresis, weight loss, or a >10% decrease in percent-predicted FEV1 (%FEV1). Iron deficiency was defined according to other studies of CF-related anemia10,12 as a plasma iron level <12 μmol/L. All sputum samples were spontaneously expectorated. No CF patient was assigned to more than one clinical category. Patients with gross hemoptysis were not considered for participation in the study.

As per the discretion of the treating physician, all study participants with clinical deterioration according to the preceding definition were admitted to the hospital for intravenous antibiotics and supportive care, which included chest physiotherapy and diabetes management if applicable. These patients underwent phlebotomy within 48 hr and provided sputum samples within 72 hr of admission. Intravenous antibiotic selection was based on the bacterial susceptibility profile of the most recently available sputum culture. %FEV1 readings for the group displaying clinical deterioration were obtained at urgent office visits that immediately preceded admission.

Patients in the clinically stable group had not experienced an exacerbation requiring oral or parenteral antibiotics during the preceding month. Spirometry and samples of blood and sputum were obtained at the recruitment visit.

The study protocol was approved by the Dartmouth Medical School institutional review board, and subjects provided informed consent before participating.

Laboratory Testing

Complete blood and reticulocyte counts were done using a Sysmex XE-2100 autoanalyzer (Sysmex America, Inc., Mundelein, IL). Plasma levels of iron, ferritin, interleukin-6 (IL-6), and erythropoietin (EPO) were quantified on a COBAS c311 autoanalyzer (Roche Diagnostics USA, Indianapolis, IN). Sputum samples for iron analysis were stored at −80°C until processed. Sputum iron was quantified by inductively coupled plasma-mass spectrometry following nitric acid digestion of organic material according to the method of Heck et al.13 and is expressed as milligrams of elemental iron per kilogram of untreated sample. There was no fractionation of sputum into soluble and insoluble components. Sputum was sent to the microbiology laboratory for routine culture. In vitro antibiotic sensitivities of bacterial isolates were ascertained by the Kirby–Bauer technique using Mueller–Hinton medium.14

Statistical Analyses

Data are expressed as medians and ranges. Because data were not normally distributed, the Mann–Whitney U-test was used to compare nominal data on the basis of cohort designation. The strength of association among nominal and categorical variables is designated by Spearman's correlation coefficient (ρ). Fisher's exact test was used to compare categorical variables. Linear regression calculations were performed on log-transformed data using backward exclusion of variables if F-test results were ≥0.10. A two-tailed P-value of <0.05 was considered to be statistically significant for all calculations. PASP Statistics 18 (SPSS, Chicago, IL) was used for calculations.

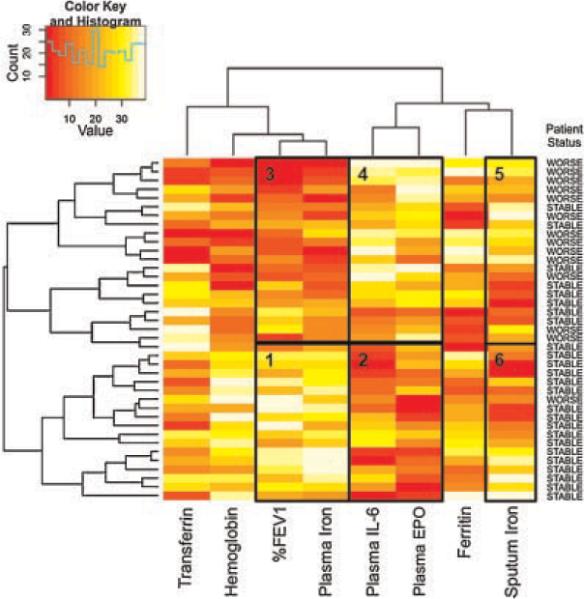

For the hierarchical cluster analysis (Fig. 1), relationships among the parameters shown in columns were objectified by calculating Pearson correlation coefficients. Complete clustering was then done using these coefficients as the measurement distance, which allowed for grouping of similar data according to rows and columns. The cohort assignment of each patient to whom a certain dataset belonged (rows) is given to the right of the heatmap. R version 2.10.1 (Open source, R Foundation for Statistical Computing) was employed for the cluster analysis.

Fig. 1.

Hierarchical cluster analysis of patient data. Shown is a heatmap of hematological measures, clinical data, and sputum iron levels for all patients in the study. Parameters are listed at the bottom of the panel. On the right side, patient status is listed (clinical stability: STABLE, clinical deterioration: WORSE). The data presented were transformed logarithmically from the raw data and ranked. Clustering was performed using complete clustering and Pearson correlation coefficients as the distance measure, which permitted grouping of data based on their similarity between adjacent columns or rows. The color key (top left) shows the color scale: red indicates relatively low values and yellow and white relatively high values (i.e., relative to the mean data). The histogram in the legend shows the number of cells achieving a particular rank. The black boxes labeled 1–6 are discussed in the text and highlight clustered sets of data.

RESULTS

CF Patients Experiencing Clinical Deterioration Have More Comorbid Conditions

Body mass index (BMI) and %FEV1 were considerably lower for those patients with interval clinical deterioration (Table 1). In order to ascertain whether %FEV1 readings for each patient at study recruitment were significantly different from readings obtained at his or her most recent evaluation, we reviewed spirometry records. The median interval between enrollment and the most recent spiro-metry for patients with clinical deterioration was 77 days (range: 28–292), and the median change in %FEV1 between these two time points was a modest −1.5% (range: −15 to +4). For the clinically stable cohort, the median duration between recruitment and the most recent spirometry was 91 days (range: 0–217), and the median change in %FEV1 between these two time points was −2.0% (range: −26 to +14). The changes in %FEV1 and duration between testing were not significantly different between groups. The prevalence of diabetes, however, was significantly higher among patients with clinical worsening, but the cohorts did not differ with respect to age or chronic disease management (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Patient Demographic and Clinical Characteristics

| Clinical stability (n = 25) | Clinical worsening (n = 14) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 27.5 (19–52) | 27.5 (22–45) |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 23.4 (17.1–34.0) | 19.3 (16.2–23.1)1 |

| Female gender | 11 (44%) | 6 (43%) |

| FEV1 (% predicted) | 56 (30–93) | 27 (16–72)1 |

| ΔF508 homozy gote | 7 (28%) | 6 (43%) |

| Inhaled tobramycin | 10 (40%) | 4 (29%) |

| Inhaled dornase alfa | 14 (56%) | 10 (71%) |

| Inhaled corticosteroid | 9 (36%) | 4 (29%) |

| Inhaled hypertonic saline | 12 (48%) | 5 (36%) |

| Routine chest physiotherapy | 18 (72%) | 12 (79%) |

| Sputum MDR PsA | 12 (48%) | 8 (57%) |

| CF-related diabetes | 8 (32%) | 12 (86%)1 |

| Iron-containing multivitamin | 5 (20%) | 2 (14%) |

MDR PsA, multi-drug resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa.

Values reported as median (range).

P < 0.05 for comparison to clinically stable patients.

Hypoferremia Is Common in CF Regardless of Clinical Stability

Iron deficiency affected 64% and 100% of clinically stable and clinically worsened patients, respectively, without any gender-specific predilection (Table 2). These data indicate that while both populations are hypoferremic, iron deficiency was more pronounced among those burdened by more comorbid states (Table 1). Few patients overall used iron-containing multivitamins, and this parameter was unassociated with plasma iron levels (Spearman ρ=0.1, P=0.4).

TABLE 2.

Summary of Iron-Related Measures

| Clinical stability (n = 25) | Clinical worsening (n = 14) | |

|---|---|---|

| Iron deficiency | 64% | 100%1 |

| Hematological measurements | ||

| Plasma iron (μmol/L) | 9.0 (4–25) | 3.6 (1–9)1 |

| Transferrin (pg/ml) | 259.0 (208–387) | 222.5 (128–322) |

| Hemoglobin (gm/dl) | 13.5 (9.3–15.4) | 11.3 (8.4–15.4)1 |

| Erythropoietin (mU/ml) | 13 (6–38) | 25 (6–62)1 |

| Plasma interleukin-6 (pg/ml) | 5.7 (2.2–19.8) | 11.1 (4.7–93.9)1 |

| Ferritin (ng/ml) | 27.0 (11–261) | 60.5 (16–215) |

| Reticulocyte count (%) | 1.0 (0.4–1.8) | 1.1 (0.3–1.5) |

| White blood count (103/μl) | 10.3 (4.4–17.1) | 11.1 (3.2–18.1) |

| Sputum measurements | ||

| Sputum iron (mg/kg) | 1.11 (0.09–4.01) | 2.22 (0.77–7.04)1 |

Values reported as median (range).

P < 0.05 for comparison to clinically stable patients.

Cluster Analysis Helps to Relate Lung Function, Iron Homeostasis, and Clinical Status

We next sought to determine if the CF populations could be distinguished based upon lung function, sputum iron levels, and selected iron-related blood tests. We performed hierarchical clustering to assess the relationships among these parameters and cohort designation (Fig. 1). Clustering places similar patients next to each other and also places similar clinical endpoints together, facilitating visual identification of common patterns.

The resulting analysis showed that most stable patients (17/25) cluster together based on relatively preserved lung function (%FEV1) and relatively high levels of plasma iron (Fig. 1, Box 1). The same group also showed comparatively low plasma IL-6 and EPO concentrations (Fig. 1, Box 2). In contrast, most patients with interval clinical deterioration (13/14) cluster together based on lower plasma iron and %FEV1 (Fig. 1, Box 3), as well as higher plasma EPO and IL-6 values (Fig. 1, Box 4). When sputum iron measurements for the two groups are qualitatively viewed on the heatmap, greater heterogeneity is apparent (Fig. 1, Boxes 5 and 6).

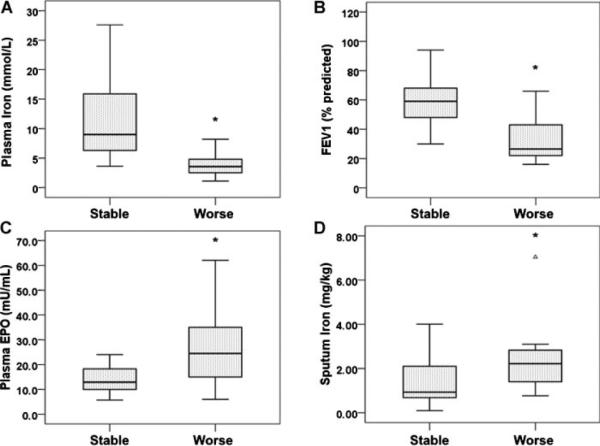

We next established the statistical significance of these observations based on the analysis shown in Figure 1. For patients with worsened clinical features, plasma iron and %FEV1 were significantly lower, and EPO levels were significantly higher, than those of stable patients (Fig. 2A–C and Table 2). Moreover, the former group had a statistically significant increase in sputum iron compared to the latter group (Fig. 2D and Table 2).

Fig. 2.

Patients with clinical deterioration display a characteristic profile of iron homeostasis and lung function. Patients were again divided into those with stable signs and symptoms (STABLE) and those with interval clinical worsening (WORSE) and analyzed for plasma iron (A), %FEV1 (B), plasma erythropoietin (C), and sputum iron (D). Patients with worsening clinical status displayed statistically significantly differences in all of these metrics. *P<0.05 for the comparison. In each figure the black horizontal line in the box is the median. The area inside the box shows the 25th–75th percentiles, and the vertical lines represent the minimum and maximum values.

Plasma But Not Sputum Iron Concentrations Correlate With Lung Function in CF

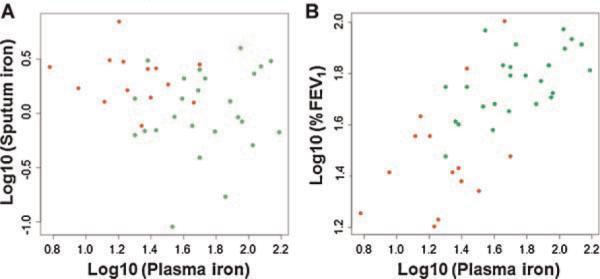

As described above, data in Figure 1 and Table 2 showed that as a group, those with interval clinical deterioration tended to have lower plasma iron readings and higher levels of sputum iron. We next examined the correlation between plasma and sputum iron on a patient-by-patient basis, in part based on the work of Reid et al.12 who suggested that iron loss into the airway might be the cause of increased sputum iron levels. That is, might the low levels of iron in the blood be explained by loss into sputum? However, as shown in Figure 3A for individual patients, blood and sputum iron content had no significant relationship to each other (Spearman ρ=−0.1, P=0.4).

Fig. 3.

Relationship of plasma iron to sputum iron and %FEV1. A: Log-transformed plasma iron values are plotted versus log-transformed sputum iron values. R2 was calculated as 0.03 (P=0.3), and thus did not indicate any significant correlation between blood and sputum iron levels on a patient-by-patient basis. B: Log-transformed plasma iron values are plotted versus log-transformed %FEV1 values. The relationship between these two parameters is significant (R2=0.48, P=1.0×10−6). For both plots, patients with worsened clinical features are shown in red and stable patients in green.

We next explored whether plasma iron was associated with any clinical measures. We noted a strong positive association between this parameter and %FEV1 when all 39 CF patients were considered (Fig. 3B; R2=0.48, P=1.0×10−6). Linear regression analysis of data from both CF groups revealed that hemoglobin was directly related to plasma iron (R2=0.43, P=6.3×10−6) and that plasma iron varied indirectly with plasma IL-6 and EPO concentrations (R2=0.35, P=6.8×10−5 for each comparison). Sputum iron was not correlated with %FEV1, hemoglobin, or bloodstream ferritin, IL-6, and EPO (P>0.05 for all comparisons).

DISCUSSION

The key objectives of this study were to gain an increased understanding of the iron status of CF patients as well as to explore the relationship between iron levels in the sputum and in the blood. The major novel observation of this work is that patients investigated during a period of clinical deterioration manifested a characteristic profile of impaired lung function, hypoferremia, ineffective erythropoiesis, and high sputum iron compared to stable patients (Figs. 1 and 2). Moreover, we also showed a strong positive correlation between plasma iron levels and %FEV1, which is congruent with the work of Reid et al.12 Although patients displaying clinical deterioration had lower plasma and higher sputum iron levels as a cohort, we did not identify any correlation between these measures on a patient-by-patient basis when all subjects were assessed. Therefore, we demonstrate for the first time that for individual patients, blood iron levels are not predictive of iron levels in the lung.

Results of this study should be interpreted with an understanding that the population at hand is clinically heterogeneous, which is exemplified by the wide ranges for various measurements.

A fundamental question raised by this work is whether the biochemical distinctions between CF cohorts derive from relatively acute physiologic changes of pulmonary exacerbation or baseline disease severity. Two observations support the latter estimation. First, we found no statistically significant difference in %FEV1 decline or spirometry interval between groups. Changes in lung function have shown variable utility in defining both exacerbation status and disease severity,15 so it is possible that the severity of %FEV1 impairment, rather than small interval changes that punctuate mild exacerbation, informed not only the worsened signs and symptoms of certain patients we studied but also their iron-related tests. Indeed, baseline disease severity among adult CF patients is felt to influence symptom perception.16 Second, diabetes is a longitudinal complication of this disease. The greater prevalence of diabetes in those who fulfilled our definition of clinical deterioration likely attests to advanced disease. Serial assessment of iron-specific biomarkers from the time of exacerbation onset to convalescence, rather than a cross-sectional analysis, would help to answer the question of whether alterations in iron homeostasis correlate with lung function trends.

Our study shows that the majority of CF patients are hypoferremic, a finding consistent with previous studies.9–11 Specifically, more severely ill patients displayed the greatest prevalence of iron deficiency. Khalid et al.10 have also demonstrated that CF patients undergoing acute exacerbation are more likely to be iron deficient than stable patients. We have extended these observations by showing that higher sputum iron levels are observed in more symptomatic patients. It is worth noting that the hypoferremia and anemia seen among sicker CF patients in the present study was observed in the context of increased plasma IL-6 and EPO levels. Higher EPO levels would be expected to cause a higher % reticulocyte count in the bloodstream of these patients, as EPO stimulates the bone marrow to release erythrocyte precursors;17 however, this was not seen. This biochemical profile is compatible with anemia of chronic disease in which iron sequestration and decreased enteric iron uptake mediated by cytokines like IL-6 negatively impact bone marrow production of red blood cells.18 We can find only one study showing that serum IL-6 is higher in CF patients than normal controls, but IL-6 and iron status were not addressed.19 Thus, we show that plasma iron and IL-6 are closely correlated in CF.

In our study, sputum iron was unrelated to traditional patient-related benchmarks of disease severity like %FEV1, diabetes, and anemia.20–22 Reid et al.12 have presented cross-sectional sputum iron data that differ from our investigation. These authors assessed the systemic (i.e., bloodstream) iron status of 30 clinically stable CF patients and quantified sputum iron in 13 of these patients. They showed that high sputum iron correlated with decreased lung function.12 We observed no such relationship in our study. The contradictory findings could be explained by the different circumstances under which testing was performed, as we considered data from stable and acutely ill subjects, while Reid et al.12 evaluated only stable patients. The clinical ramifications of excess airway iron in CF merit further study.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work is supported by National Institutes of Health grants R01-HL074175-04-06 and P20 RR-018787 (BAS), Cystic Fibrosis Foundation Research Development Program grant STANTO7R0 (BAS), and a pilot award from the Dartmouth Center for Clinical and Translational Science (AHG, HWP). The Dartmouth Trace Element Analysis Core is supported by NIH grant P42 ES007373.

Funding source: National Institutes of Health, Numbers R01-HL074175-04-06, P20 RR-018787

Footnotes

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

REFERENCES

- 1.Strausbaugh SD, Davis PB. Cystic fibrosis: a review of epidemiology and pathobiology. Clin Chest Med. 2007;28:279–288. doi: 10.1016/j.ccm.2007.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rosenfeld M, Ramsey BW, Gibson RL. Pseudomonas acquisition in young patients with cystic fibrosis: pathophysiology, diagnosis, and management. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2003;9:492–497. doi: 10.1097/00063198-200311000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Konstan MW, Morgan WJ, Butler SM, Pasta DJ, Craib ML, Silva SJ, Stokes DC, Wohl ME, Wagener JS, Regelmann WE, Johnson CA, the Scientific Advisory Group and the Investigators and Coordinators of the Epidemiologic Study of Cystic Fibrosis Risk factors for rate of decline in forced expiratory volume in one second in children and adolescents with cystic fibrosis. J Pediatr. 2007;151:134–139. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2007.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moreau-Marquis S, Stanton BA, O'Toole GA. Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm formation in the cystic fibrosis airway. Pulm Pharmacol Ther. 2008;21:595–599. doi: 10.1016/j.pupt.2007.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moreau-Marquis S, Bomberger JM, Anderson GG, Swiatecka-Urban A, Ye S, O'Toole GA, Stanton BA. The ΔF508-CFTR mutation results in increased biofilm formation by P. aeruginosa by increasing iron availability. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2008;295:L25–L37. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00391.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Moreau-Marquis S, O'Toole GA, Stanton BA. Tobramycin and FDA-approved iron chelators eliminate Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms on cystic fibrosis cells. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2009;41:305–313. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2008-0299OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reid DW, Carroll V, O'May C, Champion A, Kirov SM. Increased airway iron as a potential factor in the persistence of Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection in cystic fibrosis. Eur Respir J. 2007;30:286–292. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00154006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Reid DW, Lam QT, Schneider H, Walters EH. Airway iron and iron-regulatory cytokines in cystic fibrosis. Eur Respir J. 2004;24:286–291. doi: 10.1183/09031936.04.00104803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fischer R, Simmerlein R, Huber RM, Schiffl H, Lang SM. Lung disease severity, chronic inflammation, iron deficiency, and erythropoietin response in adults with cystic fibrosis. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2007;42:1193–1197. doi: 10.1002/ppul.20717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Khalid S, McGrowder D, Kemp M, Johnson P. The use of soluble transferrin receptor to assess iron deficiency in adults with cystic fibrosis. Clin Chim Acta. 2007;378:194–200. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2006.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pond MN, Morton AM, Conway SP. Functional iron deficiency in adults with cystic fibrosis. Respir Med. 1996;90:409–413. doi: 10.1016/s0954-6111(96)90114-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Reid DW, Withers NJ, Francis L, Wilson JW, Kotsimbos TC. Iron deficiency in cystic fibrosis: relationship to lung disease severity and chronic Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection. Chest. 2002;121:48–54. doi: 10.1378/chest.121.1.48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Heck JE, Andrew AS, Onega T, Rigas JR, Jackson BP, Karagas MR, Duell EJ. Lung cancer in a U.S. population with low to moderate arsenic exposure. Environ Health Perspect. 2009;117:1718–1723. doi: 10.1289/ehp.0900566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schoenknecht FD. The Kirby-Bauer technique in clinical medicine and its application to carbenicillin. J Infect Dis. 1973;127:111–115. doi: 10.1093/infdis/127.supplement_2.s111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hafen GM, Ranganathan SC, Robertson CF, Robinson PJ. Clinical scoring systems in cystic fibrosis. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2006;41:602–617. doi: 10.1002/ppul.20376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Abbott J, Holt A, Hart A, Morton AM, MacDougall L, Pogson M, Milne G, Rodgers HC, Conway SP. What defines a pulmonary exacerbation? The perceptions of adults with cystic fibrosis. J Cyst Fibros. 2009;8:356–359. doi: 10.1016/j.jcf.2009.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Casadevall N. Cellular mechanism of resistance to erythropoietin. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1995;10:27–30. doi: 10.1093/ndt/10.supp6.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Weiss G. Iron metabolism in the anemia of chronic disease. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009;1790:682–693. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2008.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nixon LS, Yung B, Bell SC, Elborn JS, Shale DJ. Circulating immunoreactive interleukin-6 in cystic fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1998;157:1764–1769. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.157.6.9704086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Costa M, Potvin S, Berthiaume Y, Gauthier L, Jeanneret A, Lavoie A, Levesque R, Chiasson J, Rabasa-Lhoret R. Diabetes: a major co-morbidity of cystic fibrosis. Diabetes Metab. 2005;31:221–232. doi: 10.1016/s1262-3636(07)70189-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.von Drygalski A, Biller J. Anemia in cystic fibrosis: incidence, mechanisms, and association with pulmonary function and vitamin deficiency. Nutr Clin Pract. 2008;23:557–563. doi: 10.1177/0884533608323426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mayer-Hamblett N, Rosenfeld M, Emerson J, Goss CH, Aitken ML. Developing cystic fibrosis lung transplant referral criteria using predictors of 2-year mortality. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;166:1550–1555. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200202-087OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]