Abstract

Ionizing radiation (IR) produces direct two-ended DNA double-strand breaks (DSBs) primarily repaired by non-homologous end joining (NHEJ). It is, however, well established that homologous recombination (HR) is induced and required for repair of a subset of DSBs formed following IR. Here, we find that HR induced by IR is drastically reduced when post-DNA damage replication is inhibited in mammalian cells. Both IR-induced RAD51 foci and HR events in the hprt gene are reduced in the presence of replication polymerase inhibitor aphidicolin (APH). Interestingly, we also detect reduced IR-induced toxicity in HR deficient cells when inhibiting post-DNA damage replication. When studying DSB formation following IR exposure, we find that apart from the direct DSBs the treatment also triggers formation of secondary DSBs peaking at 7–9 h after exposure. These secondary DSBs are restricted to newly replicated DNA and abolished by inhibiting post-DNA damage replication. Further, we find that IR-induced RAD51 foci are decreased by APH only in cells replicating at the time of IR exposure, suggesting distinct differences between IR-induced HR in S- and G2-phases of the cell cycle. Altogether, our data indicate that secondary replication-associated DSBs formed following exposure to IR are major substrates for IR-induced HR repair.

INTRODUCTION

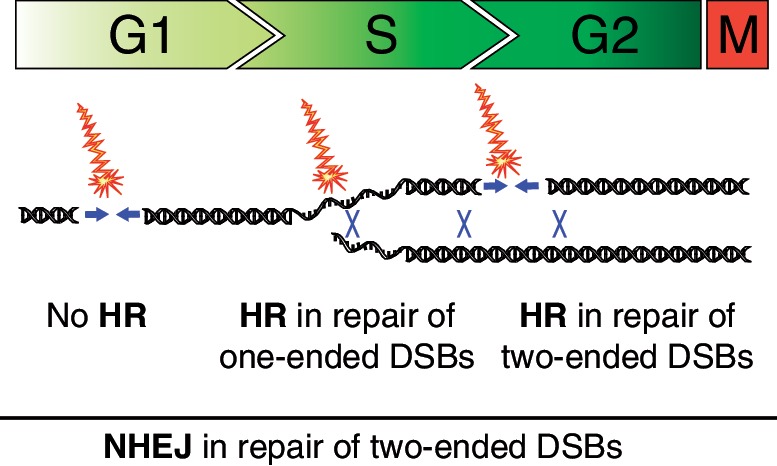

Ionizing radiation (IR) induces a broad range of DNA damage, including modifications on bases and sugars, interstrand crosslinks, DNA single-strand breaks (SSBs), clustered damage and direct DNA double-strand breaks (DSBs) (1). The direct DSB, with two free DNA ends, has been a focus for investigations for decades, since it is considered to be the most critical DNA lesion. If not repaired correctly, DSBs may lead to chromosomal rearrangements resulting in genomic instability or cell death (2). Apart from the direct DSB, the one-ended DSB has also been described and is formed as a result of stalled DNA replication and subsequent replication fork collapse (3).

Non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) and homologous recombination (HR) are two distinct pathways repairing DSBs. Cells deficient in either pathway exhibit increased sensitivity to IR (4–8) and extensive studies have attempted to determine under what circumstances either of the two pathways is favoured in the repair of DSBs. It is now well established that NHEJ represents the major pathway for repair of direct two-ended DSBs throughout the cell cycle (8,9). NHEJ performs rapid repair in a homology independent process involving factors such as DNA-PKcs/Ku70/Ku80 and DNA LigaseIV/XRCC4/XLF (10,11). HR has been shown to be involved in the repair of more complex and persisting two-ended DSBs (8), in particular repair of two-ended DSBs produced in heterochromatin regions in cells in the G2-phase of the cell cycle (12). A growing body of evidence also supports HR as the most important pathway for repair of replication-associated one-ended DSBs formed at collapsed replication forks (13–16). It has been demonstrated that the one-ended DSB is resected to produce 3′ ssDNA overhangs triggering RAD51-dependent HR repair that may result in sister chromatid exchange (SCE) (13,17,18).

The substrate for IR induced HR is still poorly defined and requires further investigation. In this study, we find that the induction of HR following exposure to IR decreases drastically when inhibiting post-DNA damage replication. When further investigating the formation of DSBs we find that, apart from the formation of direct DSBs, secondary replication-associated DSBs form ∼7–9 h after exposure. The formation of these DSBs is abolished by inhibiting post-DNA damage replication and they also exhibit prolonged repair time in HR deficient cells. Based on these findings, we propose secondary DSBs as an important substrate for IR-induced HR.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell lines and cell culture

AA8 is a Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cell line. U2OS is a human osteosarcoma cell line with wild-type p53 and RB protein (19,20). The V-C8 cell line, derived from the V79 Chinese hamster lung fibroblast cell line, has a mutation in the BRCA2 gene resulting in impaired HR (21). The restored cell line V-C8 + B2 is complimented with human BRCA2. AA8, U2OS, V-C8 and V-C8 + B2 cell lines were all cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) containing 9% foetal calf serum and penicillin-streptomycin (90 U/ml), at 37°C in and 5% CO2 atmosphere. The SPD8 cell line carries a mutation in the hprt gene and was cultured and used for determination of recombination frequencies as described in (22).

Ionizing radiation exposure

Cells were γ-irradiated in a Cs137 chamber with a dose rate of either 6.47 or 0.40 Gy/min.

Recombination in SPD8 cells

A total of 1 × 106 cells were inoculated into 100 mm dishes in medium 24 h before irradiation with gamma rays (137Cs irradiator). Immediately after irradiation, the cells were allowed to recover for 4 h in the presence or absence of 0.5 µM of aphidicolin (APH) (Sigma). After treatment, the cells were released by trypsinization and counted. HPRT+ revertants were selected by plating 3 × 105 cells per dish in the presence of HAsT (50 µM hypoxanthine, 10 µM l-azaserine and 5 µM dT). To determine cloning efficiency, two dishes were plated with 500 cells each. The colonies obtained were stained with methylene blue in methanol (4 g/l), after 7 (in the case of cloning efficiency) or 10 (for reversion) days of incubation.

Immunofluorescence

Cells were plated onto coverslips 24 h before irradiation. After irradiation, the cells were allowed to recover for 4 h or incubated in the presence of 0.5 µM APH for 4 h. In the case of labelling, cells were pulse labelled with EdU for 20 min. All cells were rinsed and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde at room temperature for 30 min. EdU staining was performed according to manufacturer’s protocol (CLICK-iT EdU 488, Invitrogen). Subsequently, coverslips were stained with a rabbit polyclonal antibody α-RAD51 (H-92, Santa Cruz), mouse monoclonal α-CENP-F (Abcam) or mouse monoclonal antibody α-γH2AX (Upstate), secondary fluorescent antibodies and counterstained with Topro. Cells with more than 10 foci were counted as positive. The threshold of 10 foci was used to minimize the background as control cells often displayed a low number of foci. Background levels of control cells displaying less than 10 foci were estimated to ∼20% for RAD51 and 25% for γH2AX. The frequencies of cells containing foci were determined in three separate experiments. At least 200 nuclei were counted on each slide.

Toxicity assay

V-C8 and V-C8 + B2 cells were plated in 25 cm2 flasks 24 h prior to irradiation with indicated doses. Immediately after irradiation, cells were treated with 0.5 µM of APH for 4 h or left to recover for 4 h at 37°C. Next, cells were trypsinized and seeded in different densities onto 100 mm dishes. Cells were grown for 10 days and then fixed and stained with methylene blue in methanol (4 g/l). Colonies of more than 50 cells were counted and the surviving fraction for each dose was calculated.

Pulsed-field gel electrophoresis

Flasks of 25 cm2 were inoculated with 106 cells 48 h prior to treatment with IR. In the case of homogeneous DNA labelling, cells were incubated with [14C]-thymidine (0.48 µM, 0.925 kBq/ml) in media for 24 h before treatment. For pulse labelling of the replication forks, cells were incubated with [14C]-thymidine (4.8 µM, 9.25 kBq/ml) in media 0.5 h prior to treatment. This was followed by irradiation with 50 Gy (137Cs, 7.1 Gy/min). Cells were harvested immediately after irradiation or after indicated incubation time, in 37°C, 5% CO2. Agarose plugs were prepared as previously described (23). Quantification was done in Image Gauge software (FLA-3000, FujiFilm). Three individual experiments were performed for each setup.

RESULTS

IR-induced homologous recombination is reduced by post-DNA damage replication inhibition

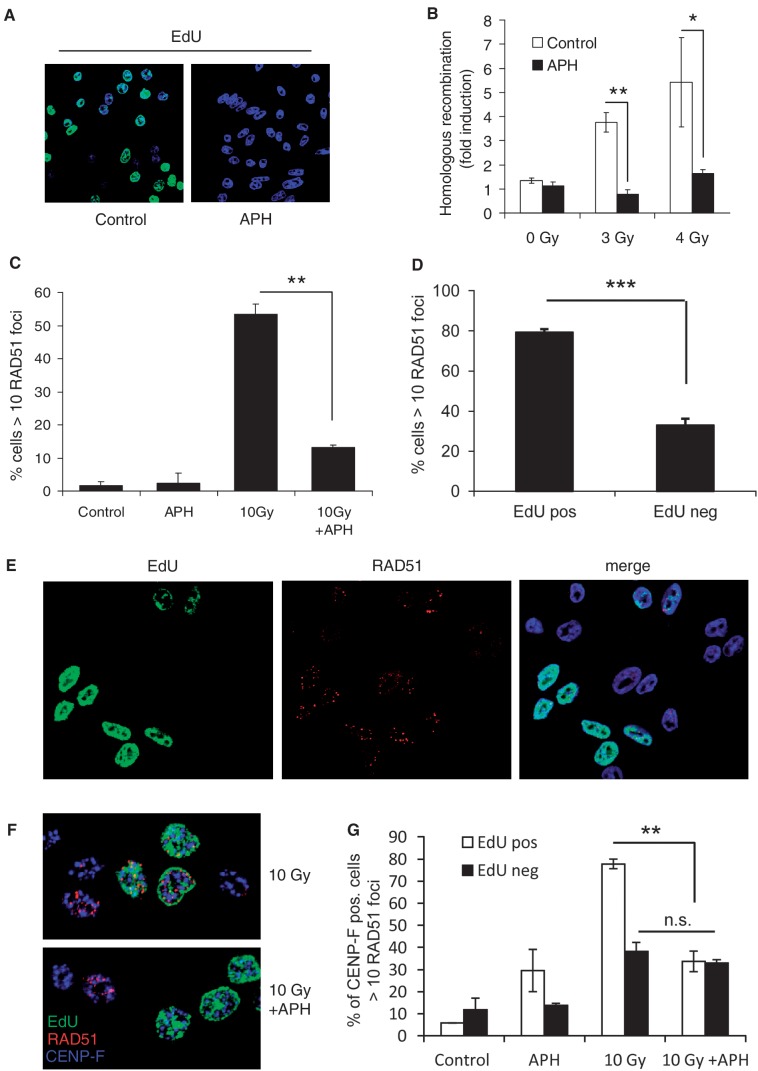

The well-documented link between HR repair and replication-associated lesions (13–16,24) urged us to investigate the relationship between IR-induced HR and replication. To study this, we started out by measuring IR-induced recombination with or without post-IR addition of APH, a DNA polymerase inhibitor that efficiently reduces DNA incorporation (Figure 1A). By adding APH, we prevent further elongation of replication forks active after IR treatment, i.e. post-DNA damage replication. We measured recombination frequencies in the hprt gene using the established HR-assay (22) involving the SPD8 cell line derived from the Chinese hamster cell line V79. In this assay, a functional hprt gene gives HAsT resistance, which may be selected for in a clonogenic survival assay. Cells were exposed to indicated doses of IR and thereafter allowed to recover for 4 h with or without the addition of APH inhibiting post-DNA damage replication. Interestingly, we found that the addition of APH following irradiation efficiently reduced IR-induced recombination frequencies (Figure 1B). To further investigate the HR response, we continued by fixing cells at 4 h following IR treatment and stained for the recombination protein RAD51. As expected, IR exposure efficiently induced RAD51 foci and increased the fraction of RAD51 positive cells (Figure 1C). However, when cells were incubated with APH during the 4-h recovery time after IR we found the treatment to cause a drastic decrease in the amount of RAD51 foci positive cells (Figure 1C). Treatment with a higher dose of APH for 4 h alone resulted in increased RAD51 foci formation, demonstrating that APH itself does not impair RAD51 recruitment (Supplementary Figure S1).

Figure 1.

Reduced IR-induced HR by replication inhibition with APH. (A) EdU incorporation (green) visualized by immunofluorescence in AA8 cells ±4-h treatment with replication inhibitor aphidicolin (APH). (B) HR frequencies induced in the hprt gene in SPD8 hamster cells by γ-radiation ±0.5 µM APH. (C) Quantification of RAD51 foci positive SPD8 cells 4 h following exposure to 10 Gy± 0.5 µM APH. (D) Quantification of RAD51 foci in EdU positive and negative AA8 cells 4 h following exposure to 10 Gy. (E) Representative image of anti-EdU (green) and anti-RAD51 (red) stained AA8 cells 4 h following exposure to 10 Gy. Merge with DNA (blue) in image furthest to the right. (F) Representative images of AA8 cells stained for EdU (green), RAD51 (red) and CENP-F (blue) exposed to either 10 Gy or 10 Gy+ 0.5 µM APH. (G) Quantification of RAD51 positive S-phase cells (EdU positive, CENP-F positive) and G2-cells (EdU negative, CENP-F positive) 4 h following exposure to 10 Gy± 0.5 µM APH. Averages of at least two independent experiments are represented, error bars show SE. Statistical significance was determined using Student’s t-test, n.s. = non-significant, **P < 0.01.

The above results lead us to further investigate the distribution of RAD51 foci in replicating cells following exposure to IR. For this, AA8 cells were labelled with a 20-min EdU pulse directly following IR exposure to visualize cells that were replicating at the time of the treatment. When quantifying RAD51 foci 4-h post-IR, we found that EdU-labelled cells were RAD51 positive to a very high degree. In contrast, EdU negative cells were only ∼30% RAD51 positive (Figure 1D and E) indicating that RAD51 foci primarily form in cells that are replicating at the time of IR exposure. The cells negative for EdU and positive for RAD51 foci likely represent cells being in the G2-phase of the cell cycle at the time of exposure. To determine whether the reduction of RAD51 foci by inhibition of post-damage replication is selective for replicating cells, we sorted cells according to being in S- or G2-phase at the time of the treatment. Firstly, cells were labelled with EdU, exposed to IR and then fixed following 4 h of incubation with or without APH. Cells were stained for RAD51 and the G2-marker CENP-F, a factor that associates with the kinetochore during the G2-phase of the cell cycle (25). Cells displaying EdU labelling and CENP-F staining were sorted as S-phase cells and cells showing only CENP-F staining were regarded as cells in G2. In agreement with our previous results, we found RAD51 foci to be highly induced in S-phase cells and this induction to be reduced by the presence of APH during post-IR incubation (Figure 1F and G). The level of RAD51 foci was also increased in G2-cells (statistically significant P = 0.03; Figure 1G), in line with the notion that HR is involved in repairing two-ended DSBs induced by IR in G2-cells (12). However, in contrast to what was found for S-phase cells, we could not detect any decrease of IR-induced RAD51 foci in G2-cells when inhibiting post-DNA damage replication with APH (Figure 1G). Altogether, our data indicate distinct differences between IR-induced HR in S- and G2-phases of the cell cycle.

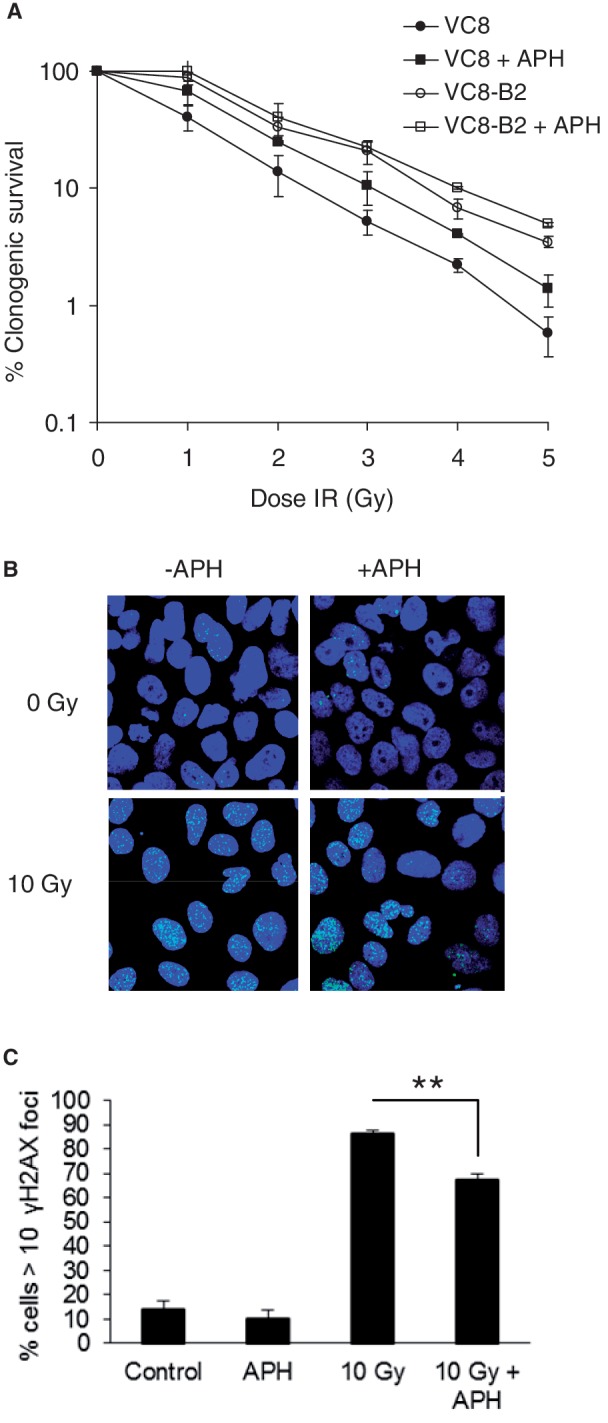

Post-DNA damage replication inhibition rescue IR-induced DNA damage and toxicity

We next set out to determine what effect the drastic drop in HR events following post-DNA damage replication inhibition represented. Cells deficient in HR exhibit increased sensitivity to IR when in S- or G2-phases of the cell cycle (8,26). To test what effect inhibition of post-DNA damage replication may have on survival following exposure to IR, we determined clonogenic survival of the HR deficient V-C8 cells (BRCA2mut) and BRCA2 restored V-C8 + B2 cells. Exponentially growing cells were exposed to increasing doses of IR and thereafter allowed to recover with or without the addition of APH during 4 h. For the restored cell line V-C8 + B2, expressing a functional BRCA2 gene, the addition of APH only marginally increased the survival following IR treatment. In contrast, we found that the increased toxicity to IR in HR deficient V-C8 cells could be partially reversed by the addition of APH (Figure 2A). The D37 (the dose where 37% of cells survive) increased by 50% in HR defective cells with the addition of APH, while the increase was only 6.5% in restored cells (Figure 2A).

Figure 2.

Replication inhibition reduces toxicity and DNA damage formation. (A) Survival in V-C8 and V-C8 + B2 cells after γ-radiation ±0.5 µM APH. (B) Representative images of anti-γH2AX stained U2OS cells 4 h after exposure to 10 Gy± 5 µM APH. (C) Quantification of γH2AX positive cells 4 h following exposure to 10 Gy± treatment with 5 µM APH. Cells with more than 10 γH2AX foci were scored as positive. Average of four individual experiments are represented, error bars show SE. Statistical significance was determined using Student’s t-test, **P < 0.01.

The reduced toxicity suggests that inhibition of post-DNA damage replication protects cells from certain damage following exposure to IR. We continued by determining formation of γH2AX foci that are known to form at sites of DNA damage and more specifically at DNA DSBs (27,28). For this experiment, the human osteosarcoma cell line U2OS was used because of the low background level of γH2AX in these cells. The cells were fixed at 4-h post-irradiation with 10 Gy, the time point previously used for measuring RAD51 foci. At this time point, we found most of the irradiated cells to be positive for γH2AX foci. When adding APH during the 4-h recovery time we found that the fraction of cells positive for γH2AX foci decreased (Figure 2B and C). The same effect by APH treatment was also observed in V-C8 cells determined by western blot detection of γH2AX (Supplementary Figure S1D). This indicates that the amount of DNA damage is lower at 4 h following irradiation when post-DNA damage replication is inhibited, possibly correlating to a decreased amount of DSBs formed.

Formation of secondary replication-associated DSBs in response to IR

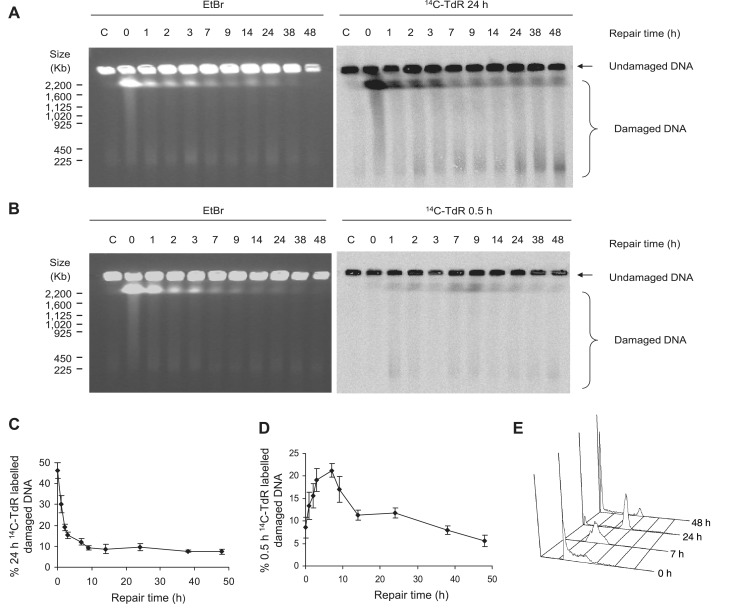

The collision of post-DNA damage replication forks with persisting DNA damage may give rise to replication-associated one-ended DSBs (3). Although such DSBs have not been demonstrated after IR-induced damage it has been speculated that these may form and constitute substrates for HR repair (29). Given the observed reduction in γH2AX foci we reasoned that post-DNA damage replication inhibition may prevent formation of a fraction of DSBs formed in association with replication. This prompted us to further investigate the DSB formation following IR with a modified pulsed field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) assay previously described for detection of hydroxyurea induced DSBs (23). Here, AA8 cells were incubated in media containing 14C-TdR for either 24 h to label DNA genome-wide or for 0.5 h to pulse label only nascent DNA at progressing replication forks. Cells were irradiated with 50 Gy, a relatively high dose that is required because of the low resolution of PFGE. Cells were allowed to repair and DSB formation was subsequently determined by PFGE at indicated time points (Figure 3A and B). We found that the majority of genome-wide DSBs, detected either by ethidium bromide (EtBr) staining or 24 h 14C-TdR autoradiography, were repaired within 3 h following IR (Figure 3A), which is in line with previous results (8,12). Interestingly, DSBs in nascent DNA was not detected directly following irradiation but appeared during the repair time and peaked ∼7–9 h after IR treatment (Figure 3B—right panel). This enrichment in DSBs could not be detected in 24-h labelled DNA and quantification of induction and repair patterns for genome-wide and replication associated DSBs show markedly different profiles (Figure 3C and D).

Figure 3.

Formation of secondary replication-associated DSBs. Detection of DSB formation by PFGE in AA8 cells allowed to repair for indicated time following 50 Gy γ-irradiation. (A) Gel displaying genome-wide DSB formation visualized by EtBr staining (left panel) and autoradiography of 24-h 14C-TdR-labelled DNA (right panel). (B) Gel displaying either genome-wide DSBs visualized by EtBr staining (left panel) or DSBs in nascent DNA visualized by autoradiography of 0.5-h 14C-TdR-labelled DNA (right panel). (C) Quantification of 14C detection in the damaged DNA fraction of 24-h labelled DNA from AA8 cells irradiated with 50 Gy. (D) Quantification of 14C detection in the damaged DNA fraction of 0.5-h-labelled DNA from AA8 cells irradiated with 50 Gy. Averages of three independent experiments are depicted, error bars show SE. (E) Representative image from FACS analysis of cell cycle progression in AA8 cells following exposure to 50 Gy.

IR induces checkpoint activation resulting in inhibition of origin firing and a prolonged S-phase (30–32). FACS analysis confirms that cells are blocked in S-phase at the 7-h time point (Figure 3E). However, replication forks are not subjected to checkpoint mediated inhibition as replication rates measured with the DNA fibre technique (Supplementary Methods) were unaffected by IR treatment (Supplementary Figure S4). As post-DNA damage replication forks continue to elongate, it is likely that they will encounter persisting DNA damage which may result in replication associated one-ended DSBs

A sub-G1 fraction was also detected with FACS analysis at the 24- and 48-h time point (Figure 3E). To rule out the possibility that apoptotic DNA fragmentation influenced the levels of DSBs visualized by PFGE, we quantified IR induced apoptosis. We could not find that cells were positive for apoptosis before the 24-h time point following irradiation (Supplementary Figure S2). Still, it cannot be excluded that DNA fragmentation contributes to the total amount of DSBs between 24 and 48 h. At these late time points, distinct low-molecular weight fragments appear clearly on the gel (Figure 3A, right panel) which is the likely result of apoptotic cleavage of DNA.

Formation of secondary replication-associated DSBs is dependent on post-DNA damage replication and accumulates in HR deficient cells

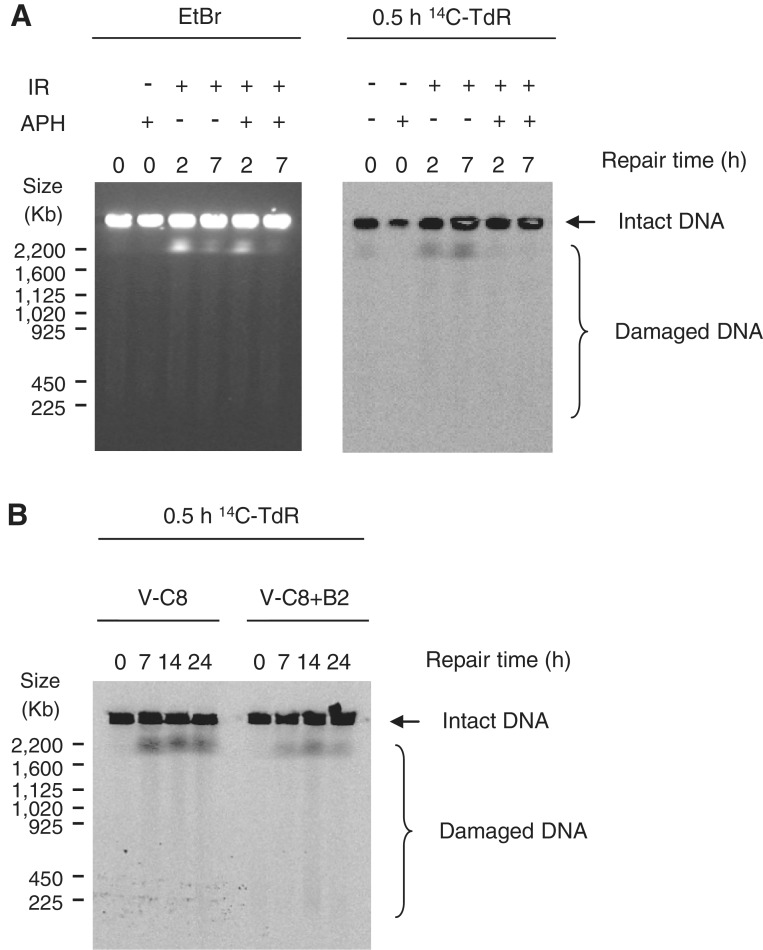

As the inhibition of post-DNA damage replication with APH highly reduces recombination frequencies and also affects γH2AX foci formation following IR, we wanted to study the effect of APH on the DSBs visualized on PFGE. We labelled AA8 cells with 14C-TdR for 0.5 h, after which they were γ-irradiated with 50 Gy. APH was added directly after irradiation and cells were harvested following 2 or 7 h of repair. Although APH did not markedly affect overall induction or repair of IR-induced DSBs, as observed by EtBr staining, it completely abolished the release of pulse 14C-TdR-labelled DNA fragments (Figure 4A), demonstrating that the formation of DSBs in nascent DNA following IR requires elongating replication forks (post-DNA damage replication).

Figure 4.

Secondary DSBs are dependent on replication and accumulate in HR deficient cells. (A) Detection of DSB formation by PFGE in AA8 cells following irradiation with 50 Gy± 5 µM APH at indicated time points. EtBr staining (left panel) and autoradiography of 0.5-h 14C-TdR-labelled DNA (right panel). (B) Autoradiography of 0.5-h 14C-TdR-labelled DNA visualizing DSBs in nascent DNA in V-C8 and V-C8 + B2 at indicated time points.

Because APH both abolish the secondary DSBs formed following IR and reduce the toxicity in HR deficient cells we were curious to find out if the secondary DSBs are in fact substrates for HR. We continued by investing the amount of DSBs in 0.5-h 14C-TdR-labelled DNA in V-C8 and V-C8 + B2 cells. We could detect an enhanced accumulation of DSBs in the HR deficient V-C8 cells compared to the restored V-C8 + B2 cells (Figure 4B) where the relative amount of DNA damage was significantly higher at the 14-h time point (Supplementary Figure S3A). This indicates a decreased repair capacity in the HR deficient cells for the secondary DSBs although any increased formation or reduced repair of genome-wide DSBs could not be detected in V-C8 cells (Supplementary Figure S3B).

In summary, the findings presented here point to a progressive formation of replication-associated secondary DSBs that is separate from the formation of direct DSBs following exposure to IR. These secondary DSBs are dependent on replication elongation for formation and require HR for efficient repair.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we investigate the substrate for IR-induced HR. The sensitivity of HR deficient cells following exposure to IR has previously been attributed to an inability of error-free repair of direct two-ended DSBs in the S- and G2-phases of the cell cycle. The evidence for HR repair of direct two-ended DSBs is derived from studies using the rare-cutting I-SceI endonuclease (33,34). Although IR-induced two-ended DSBs are a substrate for HR in mammalian cells in the G2-phase (12), it is not clear how common this substrate is for HR. Here, we report that the recombination response following IR is drastically reduced when post-DNA damage replication is inhibited, as both RAD51 foci formation and recombination frequencies following IR exposure were markedly decreased with the addition of replication polymerase inhibitor APH. Importantly, this is not a consequence of APH treatment itself, as an increased dose of APH triggered RAD51 foci (Supplementary Figure S1) and prolonged treatments with APH has been reported to induce HR (14,35). The decrease in RAD51 foci formation was observed specifically in cells present in S-phase at the time of IR treatment and could not be detected when studying G2-cells. This suggests that HR induced in the S-phase fraction of cells is distinct from HR induced in the G2-phase of the cell cycle. Furthermore, with PFGE we observe the release of nascent DNA fragments at 7–9 h after IR exposure, demonstrating formation of secondary DSBs. This formation is entirely dependent on post-damage replication elongation as it is prevented by APH treatment. These findings show that both formation of secondary replication-associated DSBs and HR is highly reduced when post-DNA damage replication is inhibited following IR exposure. Together, this suggests that the secondary DSBs are in fact a major substrate for IR-induced HR, which is in line with one-ended DSBs formed at replication forks commonly being repaired by HR (13–16). The secondary DSBs accumulate to a certain degree in HR deficient cells but are eventually repaired indicating a role for NHEJ in repair of one-ended DSBs as a possible back-up pathway. This is consistent with NHEJ deficient cells also being sensitive to the induction of one-ended DSBs by camptothecin (13).

The contribution of replication-associated DSBs to the total amount of DSBs formed following IR exposure has previously been discussed (29). IR induces a complex damage pattern with formation of SSBs, base lesions and clustered damage. Clustered damage, in particular, has been shown to persist and to be repair resistant (36). If DNA damage is not removed, it will inevitably be encountered by progressing replication forks during S-phase. DNA fibre experiments show that replication elongation speed is not broadly affected by exposure to IR (Supplementary Figure S4), which is in line with previous results (31). This indicates that blocking lesions are not frequently encountered following IR. However, the collapse of a few replication forks would not affect replication rates globally but could still have great impact on cell survival because of the severity of complex DSBs. In this study, we found that the addition of APH following IR reverses a major part of the increased IR toxicity in HR deficient cells. The fact that this effect can only be detected in HR deficient cells indicates that replication-associated DSBs are efficiently repaired by HR in proficient cells.

Large structures such as replication bubbles migrate poorly on PFGE (24) and we have therefore considered the possibility that the replication-associated DSBs detected here are merely IR-induced direct DSBs that become visible in PFGE after replication bubbles are cleared. There are, however, several observations suggesting that this is not the case. First, the majority of direct IR-induced DSBs will already be repaired at the 7- or 9-h time points after treatment, when a large portion of the nascent DNA is emerging in the damaged DNA. Secondly, the repair profile of nascent DNA shows a decrease in damaged DNA from 9- to 24-h time points that cannot be observed in the profile of the direct DSBs. Furthermore, we scored γH2AX foci, whose detection is not limited by replication bubbles and which are also identified at damaged replication forks (37). We found that the number of γH2AX foci present 4 h after IR treatment is reduced when inhibiting post-DNA damage replication with APH. Since we observe that APH does not affect DSB repair as such, these data suggest that the overall levels of induced DSBs are lower when secondary DSBs cannot be formed at progressing replication forks.

The reason for DSBs not to appear in nascent DNA at early time points may be because the formation of replication associated DSBs is delayed. Stalling of replication with hydroxyurea induces DSBs in a time dependent manner (14,37) indicating that DSB formation at replication forks may not be an instant process. Formation of DSBs at replication forks have been reported to require processing by endonucleases such as MUS81 (38,39). This processing may be time consuming and also be limited by only taking place in a specific stage of the cell cycle.

Altogether, this study shows that exposure to IR results in the formation of replication-associated secondary DSBs that provide important substrates for IR-induced HR. Here, we studied RAD51 foci formation both in replicating S-phase and non-replicating G2-cells, at the time of IR treatments. Although the same amount of IR-induced DNA damage is produced in all cells, inhibition of post-DNA damage replication prevented the formation of RAD51 foci in the replicating S-phase cells but not in G2-cells. This suggests that HR induced in the S-phase fraction of cells is separate from HR induced in the G2-phase of the cell cycle. Based on our findings, we propose a model where HR repair is involved in S-phase following conversion of IR-induced DNA damage on the replication template to one-ended DSBs, as well as in a distinct repair of two-ended DSBs in G2-phase (Figure 5). Furthermore, the toxicity of replication-associated damage following IR treatment in HR deficient cells reported here is an important aspect that may be explored to enhance the treatment of cancer.

Figure 5.

Model for DSB repair following IR during stages of the cell cycle. NHEJ is the major repair pathway for two-ended DSBs directly induced by IR and takes place throughout the cell cycle. HR is mostly active in S- and G2-phase when sister chromatids are present. During S-phase, progressing replication forks may encounter IR induced damage resulting in fork collapse and formation of one-ended DSBs that require HR repair. HR is likely also involved in the repair of a fraction of direct two-ended DSBs formed in S-phase when the sister chromatid is available as template. In the G2-phase, HR is involved in repair of a subset of two-ended DSBs utilizing the intact sister chromatid as template.

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Supplementary Data are available at NAR Online: Supplementary Figures 1–4, Supplementary Methods and Supplementary References [40,41].

FUNDING

Swedish Cancer Society; Swedish Children’s Cancer Foundation; Swedish Research Council; Swedish Pain Relief Foundation; Söderberg Foundation and Spanish Ministry of Education and Science (FPU Fellowship to M.L.O.). Funding for open access charge: Swedish Research Council.

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We wish to thank Dr Larry Thomson for providing materials and Evgenia Gubanova for assistance with the FACS analysis.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ward JF. DNA damage produced by ionizing radiation in mammalian cells: identities, mechanisms of formation, and reparability. Prog. Nucleic Acid Res. Mol. Biol. 1988;35:95–125. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6603(08)60611-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hoeijmakers JH. Genome maintenance mechanisms for preventing cancer. Nature. 2001;411:366–374. doi: 10.1038/35077232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Helleday T. Pathways for mitotic homologous recombination in mammalian cells. Mutat. Res. 2003;532:103–115. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2003.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kurimasa A, Kumano S, Boubnov NV, Story MD, Tung CS, Peterson SR, Chen DJ. Requirement for the kinase activity of human DNA-dependent protein kinase catalytic subunit in DNA strand break rejoining. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1999;19:3877–3884. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.5.3877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wachsberger PR, Li WH, Guo M, Chen D, Cheong N, Ling CC, Li G, Iliakis G. Rejoining of DNA double-strand breaks in Ku80-deficient mouse fibroblasts. Radiat. Res. 1999;151:398–407. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cheong N, Wang X, Wang Y, Iliakis G. Loss of S-phase-dependent radioresistance in irs-1 cells exposed to X-rays. Mutat. Res. 1994;314:77–85. doi: 10.1016/0921-8777(94)90063-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Takata M, Sasaki MS, Tachiiri S, Fukushima T, Sonoda E, Schild D, Thompson LH, Takeda S. Chromosome instability and defective recombinational repair in knockout mutants of the five Rad51 paralogs. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2001;21:2858–2866. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.8.2858-2866.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rothkamm K, Kruger I, Thompson LH, Lobrich M. Pathways of DNA double-strand break repair during the mammalian cell cycle. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2003;23:5706–5715. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.16.5706-5715.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hinz JM, Yamada NA, Salazar EP, Tebbs RS, Thompson LH. Influence of double-strand-break repair pathways on radiosensitivity throughout the cell cycle in CHO cells. DNA Repair. 2005;4:782–792. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2005.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nussenzweig A, Nussenzweig MC. A backup DNA repair pathway moves to the forefront. Cell. 2007;131:223–225. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.van Gent DC, van der Burg M. Non-homologous end-joining, a sticky affair. Oncogene. 2007;26:7731–7740. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Beucher A, Birraux J, Tchouandong L, Barton O, Shibata A, Conrad S, Goodarzi AA, Krempler A, Jeggo PA, Lobrich M. ATM and Artemis promote homologous recombination of radiation-induced DNA double-strand breaks in G2. EMBO J. 2009;28:3413–3427. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2009.276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Arnaudeau C, Lundin C, Helleday T. DNA double-strand breaks associated with replication forks are predominantly repaired by homologous recombination involving an exchange mechanism in mammalian cells. J. Mol. Biol. 2001;307:1235–1245. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.4564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Saintigny Y, Delacote F, Vares G, Petitot F, Lambert S, Averbeck D, Lopez BS. Characterization of homologous recombination induced by replication inhibition in mammalian cells. EMBO J. 2001;20:3861–3870. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.14.3861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Saleh-Gohari N, Bryant HE, Schultz N, Parker KM, Cassel TN, Helleday T. Spontaneous homologous recombination is induced by collapsed replication forks that are caused by endogenous DNA single-strand breaks. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2005;25:7158–7169. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.16.7158-7169.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Roseaulin L, Yamada Y, Tsutsui Y, Russell P, Iwasaki H, Arcangioli B. Mus81 is essential for sister chromatid recombination at broken replication forks. EMBO J. 2008;27:1378–1387. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2008.65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Haber JE. Lucky breaks: analysis of recombination in Saccharomyces. Mutat. Res. 2000;451:53–69. doi: 10.1016/s0027-5107(00)00040-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lundin C, Schultz N, Arnaudeau C, Mohindra A, Hansen LT, Helleday T. RAD51 is involved in repair of damage associated with DNA replication in mammalian cells. J. Mol. Biol. 2003;328:521–535. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(03)00313-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Craig C, Kim M, Ohri E, Wersto R, Katayose D, Li Z, Choi YH, Mudahar B, Srivastava S, Seth P, et al. Effects of adenovirus-mediated p16INK4A expression on cell cycle arrest are determined by endogenous p16 and Rb status in human cancer cells. Oncogene. 1998;16:265–272. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1201493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bartkova J, Horejsi Z, Koed K, Kramer A, Tort F, Zieger K, Guldberg P, Sehested M, Nesland JM, Lukas C, et al. DNA damage response as a candidate anti-cancer barrier in early human tumorigenesis. Nature. 2005;434:864–870. doi: 10.1038/nature03482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kraakman-van der Zwet M, Overkamp WJ, van Lange RE, Essers J, van Duijn-Goedhart A, Wiggers I, Swaminathan S, van Buul PP, Errami A, Tan RT, et al. Brca2 (XRCC11) deficiency results in radioresistant DNA synthesis and a higher frequency of spontaneous deletions. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2002;22:669–679. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.2.669-679.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Helleday T, Arnaudeau C, Jenssen D. A partial hprt gene duplication generated by non-homologous recombination in V79 Chinese hamster cells is eliminated by homologous recombination. J. Mol. Biol. 1998;279:687–694. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.1809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lundin C, North M, Erixon K, Walters K, Jenssen D, Goldman AS, Helleday T. Methyl methanesulfonate (MMS) produces heat-labile DNA damage but no detectable in vivo DNA double-strand breaks. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:3799–3811. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lundin C, Erixon K, Arnaudeau C, Schultz N, Jenssen D, Meuth M, Helleday T. Different roles for nonhomologous end joining and homologous recombination following replication arrest in mammalian cells. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2002;22:5869–5878. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.16.5869-5878.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liao H, Winkfein RJ, Mack G, Rattner JB, Yen TJ. CENP-F is a protein of the nuclear matrix that assembles onto kinetochores at late G2 and is rapidly degraded after mitosis. J. Cell Biol. 1995;130:507–518. doi: 10.1083/jcb.130.3.507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wilson PF, Hinz JM, Urbin SS, Nham PB, Thompson LH. Influence of homologous recombinational repair on cell survival and chromosomal aberration induction during the cell cycle in gamma-irradiated CHO cells. DNA Repair. 9:737–744. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2010.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rogakou EP, Pilch DR, Orr AH, Ivanova VS, Bonner WM. DNA double-stranded breaks induce histone H2AX phosphorylation on serine 139. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:5858–5868. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.10.5858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stucki M, Clapperton JA, Mohammad D, Yaffe MB, Smerdon SJ, Jackson SP. MDC1 directly binds phosphorylated histone H2AX to regulate cellular responses to DNA double-strand breaks. Cell. 2005;123:1213–1226. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.09.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Harper JV, Anderson JA, O’Neill P. Radiation induced DNA DSBs: contribution from stalled replication forks? DNA Repair. 2010;9:907–913. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2010.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jazayeri A, Falck J, Lukas C, Bartek J, Smith GC, Lukas J, Jackson SP. ATM- and cell cycle-dependent regulation of ATR in response to DNA double-strand breaks. Nat. Cell Biol. 2006;8:37–45. doi: 10.1038/ncb1337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Merrick CJ, Jackson D, Diffley JF. Visualization of altered replication dynamics after DNA damage in human cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:20067–20075. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M400022200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gatei M, Sloper K, Sorensen C, Syljuasen R, Falck J, Hobson K, Savage K, Lukas J, Zhou BB, Bartek J, et al. Ataxia-telangiectasia-mutated (ATM) and NBS1-dependent phosphorylation of Chk1 on Ser-317 in response to ionizing radiation. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:14806–14811. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M210862200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Johnson RD, Jasin M. Sister chromatid gene conversion is a prominent double-strand break repair pathway in mammalian cells. EMBO J. 2000;19:3398–3407. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.13.3398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Allen CK, Chan KC, Colestock PL, Crandall KR, Garnett RW, Gilpatrick JD, Lysenko W, Qiang J, Schneider JD, Schulze ME, et al. Beam-halo measurements in high-current proton beams. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2002;89:214802. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.89.214802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Arnaudeau C, Tenorio Miranda E, Jenssen D, Helleday T. Inhibition of DNA synthesis is a potent mechanism by which cytostatic drugs induce homologous recombination in mammalian cells. Mutat. Res. 2000;461:221–228. doi: 10.1016/s0921-8777(00)00052-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Eccles LJ, O’Neill P, Lomax ME. Delayed repair of radiation induced clustered DNA damage: friend or foe? Mutat. Res. 2010;711:134–141. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2010.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Petermann E, Orta ML, Issaeva N, Schultz N, Helleday T. Hydroxyurea-stalled replication forks become progressively inactivated and require two different RAD51-mediated pathways for restart and repair. Mol. Cell. 2010;37:492–502. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.01.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hanada K, Budzowska M, Modesti M, Maas A, Wyman C, Essers J, Kanaar R. The structure-specific endonuclease Mus81-Eme1 promotes conversion of interstrand DNA crosslinks into double-strands breaks. EMBO J. 2006;25:4921–4932. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Regairaz M, Zhang YW, Fu H, Agama KK, Tata N, Agrawal S, Aladjem MI, Pommier Y. Mus81-mediated DNA cleavage resolves replication forks stalled by topoisomerase I-DNA complexes. J. Cell Biol. 2011;195:739–749. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201104003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Groth P, Auslander S, Majumder MM, Schultz N, Johansson F, Petermann E, Helleday T. Methylated DNA causes a physical block to replication forks independently of damage signalling, O(6)-methylguanine or DNA single-strand breaks and results in DNA damage. J. Mol. Biol. 2010;402:70–82. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2010.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Henry-Mowatt J, Jackson D, Masson JY, Johnson PA, Clements PM, Benson FE, Thompson LH, Takeda S, West SC, Caldecott KW. XRCC3 and Rad51 modulate replication fork progression on damaged vertebrate chromosomes. Mol. Cell. 2003;11:1109–1117. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00132-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.