Abstract

Recent research on adolescent smokers suggests that there are important differences in the types of nicotine dependence (ND) symptoms that emerge and different patterns of ND symptoms. The purpose of this study was to use data from the longitudinal Social and Emotional Contexts of Adolescent Smoking Patterns Study to identify latent subgroups of adolescent experimental and nondaily smokers varying in number and types of endorsed ND symptoms. Profiles were identified using baseline level of smoking, individual patterns of ND symptoms and other ND risk factors. Discrete time survival analysis was used to examine profile differences in probability of becoming daily smokers 48 months later. Four distinct subgroups of smokers with different patterns of smoking behavior, ND symptoms, and alcohol and other substance use emerged. Heavier smoking adolescents with high symptom endorsement, particularly the need to smoke in the morning, were most likely to become daily smokers 48 months later. A subgroup of social smokers had high smoking exposure and symptom endorsement (except need to smoke in the morning), and high levels of other substance use. Despite lower rates of smoking frequency and quantity compared to the heavier smoking class, 36% of these adolescents smoked daily by 48 months, with a steeper decline in survival rates compared to other lighter smoking classes. Morning smoking symptoms and symptoms prioritizing smoking (i.e., choosing to spend money on cigarettes instead of lunch or smoking when ill or where smoking is forbidden) might quickly identify adolescent non-daily smokers with more severe dependence and higher risk for daily smoking. A focus on skills for avoiding social situations involving use of alcohol and other drugs and reducing peer smoking influences may be an important focus for reducing smoking and other substance use among social smokers.

Keywords: nicotine dependence symptoms, latent profile analysis, adolescent, smoking exposure

1. Introduction

Despite the success of universal initiatives to prevent smoking, a significant minority of adolescents continue to initiate smoking. National monitoring surveys suggest that the prevalence of cigarette smoking remains high. At present, 20% of high school students in the US report smoking in the past 30 days (CDC, 2011) and 10.7% of high school seniors smoke daily (Johnston, O’Malley, Bachman, & Schulenberg, 2010). Many of these adolescents ultimately establish chronic, dependent smoking patterns.

Studies of adolescent smoking behavior have shown that there are different developmental trajectories for nicotine dependence (ND; Hu, Muthen, Schaffran, Griesler, & Kandel, 2008), and that, for some adolescents, ND symptoms emerge very soon after onset of smoking and well before the establishment of daily smoking patterns (Dierker et al., 2007; DiFranza et al., 2002; Gervais, O’Loughlin, Meshefedjian, Bancej, & Tremblay, 2006; O’Loughlin et al., 2003). Additional research indicates that nearly half of adolescents who smoke as few as 1–3 days per month report experiencing at least one ND symptom (Rose, Dierker, & Donny, 2010), and that there are qualitative differences in symptom profiles between dependent and nondependent adolescents (Goedeker & Tiffany, 2008). Furthermore, some, but not all, of these ND symptoms are significant predictors of future smoking behavior among recent onset smokers, independent of current smoking exposure (Dierker & Mermelstein, 2010). This suggests that smoking outcomes may differ for smokers with different patterns of ND symptoms.

Taken together, these studies suggest that there are important differences in the types of symptoms that emerge; that the onset of these symptoms can occur at very low levels of smoking exposure; that there are different patterns of ND symptom endorsement that may affect the future likelihood of sustained, heavier smoking; and that there are some important risk factors for the development of adolescent ND. Given the amount of variability in smoking exposure in adolescents and these early emerging symptoms, it is useful to determine whether there exist subgroups of adolescent smokers that vary in their amount of smoking and patterns of ND symptoms as well as other smoking risk factors, and how the likelihood of future smoking may differ among these subgroups.

Previous research investigating patterns of symptom endorsement in recent onset adolescent smokers (Storr, Zhou, Liang, & Anthony, 2004) and young adult smokers (Storr, Reboussin, & Anthony, 2005), has found reliable latent subgroups of smokers based on level of dependence severity with subgroups distinguished primarily by increasing probability of symptom endorsement. However, studies of adolescent ND profiles have found little in the way of qualitative differences in ND subgroups in terms of the types (not just number) of symptoms endorsed. This may be due in part to the selection of measures, which typically have been limited to dependence symptoms from the DSM-IV (APA, 1994) and Fagerstrom Test for Nicotine Dependence (FTND; Fagerstrom, 1978), each designed to assess core features of dependence that do not necessarily capture the lower levels of dependence severity found to be more typical of infrequent smokers (Rose & Dierker, 2010). A notable exception is recent research on identifying ND subtypes in adolescents from the Netherlands (Kleinjan et al., 2010). Similar to other studies, this research found subgroup differences in severity of symptoms drawn from both the modified Fagerstrom Tolerance Questionnaire (mFTQ; Prokhorov, Pallonen, Fava, Ding, & Niaura, 1996) and the Hooked on Nicotine Checklist (HONC; DiFranza et al., 2002), but also identified subgroups with different types of ND, particularly with respect to endorsement of craving and withdrawal symptoms. These subgroups differed on factors such as smoking by parents and friends and depressive mood and in smoking initiation and cessation one year later (Kleinjan et al., 2010).

Because increases in dependence symptom endorsement are naturally associated with increases in dependence severity, it is not surprising that much of the previous research has failed to identify qualitatively distinct subgroups. In addition, these studies have not investigated whether symptom profiles vary as a function of ND risk factors. There are numerous risk factor associated with cigarette smoking, many of which have also been linked to the development of ND. Use of other substances including alcohol and problems with alcohol (Leeman et al., 2010), as well as parent and peer smoking (Mei-Chen Hu, Davies, & Kandel, 2006; M-C Hu, Griesler, Schaffran, & Kandel, 2011; Kandel, Hu, Griesler, & Schaffran, 2007; Scherrer et al.) have been found to be among the most prominent risk factors for smoking and ND. For example, research suggests that there are adolescents who smoke primarily when drinking in social situations (Krukowski, Solomon, & Naud, 2005). What is not yet known is whether these risk factors are associated with particular patterns of symptom endorsement. Finally, adolescent dependence symptom subgroups identified in previous research mostly have been validated cross-sectionally, and none have investigated nondaily smoking survival rates for latent subgroups across a two-year span of adolescence.

The purpose of this study was to use data from the longitudinal Social and Emotional Contexts of Adolescent Smoking Patterns Study to 1) identify latent subgroups of adolescent experimental and nondaily smokers who vary in their number and types of endorsed ND symptoms using baseline level of smoking exposure, individual patterns of ND symptoms and other ND risk factors, and 2) to determine whether there are significant differences between these latent subgroups in their probability of becoming daily smokers in the future. Including a broader range of symptoms and risk factors associated with ND that might better capture qualitative differences in adolescent smokers could result in the identification of classes that vary not only in dependence severity, but also in smoking exposure and the types of symptoms endorsed. Although the nature of this research may be considered largely exploratory, we expected to find subgroups representing increasing severity of ND identified in previous studies (Storr et al., 2004). In addition, given that there is increasing evidence for ND symptom endorsement even at low levels of adolescent smoking, we expected to find a latent subgroup representing recent onset, low smoking exposure adolescents with elevated ND symptom endorsement, and that many of these adolescents will have become regular, daily smokers by the 48-month follow up.

2. Method

2.1 Participants

The sample was drawn from the Social and Emotional Contexts of Adolescent Smoking Patterns Study. The goal of sampling was to develop a cohort of adolescents that mirrored the racial and ethnic diversity of the greater Chicago metropolitan area and were at high risk for chronic smoking. All 9th and 10th grade students at 16 Chicago-area high schools completed a brief screener survey of smoking behavior (N = 12,970). All students who reported smoking in the past 90 days and had lifetime exposure of <100 cigarettes were invited to participate, as were all those who said that they smoked in the past 30 days and smoked >100 cigarettes in their lifetime. Additionally, random samples of youth reporting having never smoked or smoking <100 lifetime, but not in the past 90 days, were also invited to participate. Of the 3,654 students invited, 1,344 agreed to participate (36.8%). Of these, 1,263 (94.0%) completed the baseline assessment. Five additional waves of data were collected at 6 months, 15 months, 24 months, 33 months, and 48 months following baseline. Overall retention rates ranged from 92% at 6 months to 86.5% at 48 months. Participants and nonparticipants at 48 months did not differ by gender, race/ethnicity, or age. Non-completers reported higher 7-day smoking rates at baseline (M = 0.85 cigarettes per day, SD = 2.47 vs. M = 0.42, SD = 1.33), p = .025; a greater number of days smoked in the past 30 (M = 5.5 days, SD = 8.75 vs. M = 3.6, SD = 7.50), p = .007; and higher numbers of cigarettes smoked on days smoked in the past 30 (M = 1.37 cigarettes, SD = 3.05 vs. M = 0.82, SD = 1.74), p = .022.

The current sample consisted of N= 697 9th and 10th grade adolescents (mean age = 15.65; SD = .63) who were nondaily smokers that, at baseline, had either 1) smoked in the past 90 days, but had not smoked more than 100 cigarettes in their lifetime (N=594), or 2) who had smoked in the past 30 days and smoked more than 100 cigarettes in their lifetime, but had not yet become daily smokers (N=103). Of the total 3,654 invited to participate, 1,645 meeting the first selection criterion for this study (smoked in the past 90 days, but had not smoked more than 100 cigarettes in their lifetime) were invited to participate, of whom 628 (35%) agreed to participate and 594 (95%) of those who agreed completed the baseline assessment. Of the total 3,654 invited to participate, 456 meeting the second selection criterion (smoked in the past 30 days and smoked more than 100 cigarettes in their lifetime) were invited, of whom 167 (36%) agreed to participate and 152 (91%) of those who agreed completed the baseline assessment. Of the 152, N=49 were daily smokers at baseline. Because the goal of this study was to identify subgroups of, and evaluate daily smoking survival rates for, nondaily smokers at baseline, these baseline daily smokers were excluded from the analyses, leaving a final sample size of 103 meeting the second criterion. Follow up attrition rates for the 697 participants in this sample adolescents ranged from 84% at 48 months to 91% at 6 months.

Baseline sample characteristics are presented in Table 1. The sample was 55.2% female and mostly Caucasian (56.4%). Half smoked one day or less in the past 30 days (51.1%) and most (80.5%) smoked no more than 7 days in the past 30 days. Very few (6.7%) smoked between 21 and 29 days of the past 30 days. Most smoked no more than one cigarette per day (75.2%). About 85% had used alcohol in the past three months, and most (74.3%) reported lifetime other drug use. Of those reporting have used other drugs, most (88.8%) had used marijuana, 24.0% had used prescription drugs without a prescription, 17.4% had used inhalants, 12.8% had used amphetamines, 8.9% had used hallucinogens, and 6.4% had used cocaine.

Table 1.

Baseline sample characteristics (N = 697).

| Variable | N (%) for categorical data |

|---|---|

| M (SD) for continuous data | |

| Male | 312 (44.8%) |

| Age | 15.65 (.63) |

| Ethnicity | |

| White | 393 (56.4%) |

| Black | 106 (14.9%) |

| Hispanic | 140 (20.1%) |

| Other | 60 (8.6%) |

| Smoking Behaviors | |

| Smoked at least 100 cigarettes in lifetime | 133 (19.1%) |

| Mean # of years smoked | 3.15 (2.05) |

| Smoking Frequency (in the past month) | |

| None | 241 (34.6%) |

| 1 day | 115 (16.5%) |

| 2–7 days | 205 (29.4%) |

| 8–20 days | 88 (12.6%) |

| 21–29 days | 47 (6.7%) |

| Smoking Quantity (in the past month) | |

| None | 252 (36.2%) |

| <=1 cig per day | 272 (39.0%) |

| 2–5 cigs per day | 167 (24.0%) |

| > 5 cigs per day | 6 (0.9%) |

| At least one parent currently smokes | 303 (43.5%) |

| Mean # of 5 closest friends who currently smoke | 1.90 (1.55) |

| NDSS Dependence Symptoms | |

| Need to smoke more to be satisfied | 260 (37.3%) |

| Have increased how much smoked since started | 325 (46.6%) |

| Need to smoke to relieve restlessness and irritability | 303 (43.5%) |

| Need to smoke to keep from experiencing discomfort | 212 (30.4%) |

| Function much better in the morning after smoking | 77 (11.4%) |

| Experience craving whenever without a smoke for hours | 140 (21.1%) |

| Craving feels like in the grip of some uncontrollable unknown force | 139 (20.6%) |

| If no cigarettes at home, would still go out and find one regardless of bad weather | 107 (15.4%) |

| Worth it to go outside to smoke even in bad weather | 204 (29.3%) |

| If low on money, would buy cigarettes instead of lunch | 116 (16.6%) |

| mFTQ Dependence Symptoms | |

| Inhale | 432 (62.0%) |

| Smoke in the first 30 minutes after waking up | 19 (2.8%) |

| Hate to give up first cigarette in the morning | 37 (5.5%) |

| Difficult to refrain from smoking in places where it is forbidden | 60 (8.9%) |

| Smoke even when very ill and need to stay in bed | 17 (2.4%) |

| Smoke more during the first 2 hours in a day | 15 (2.2%) |

| Substance Use | |

| Frequency of Alcohol use in the past 3 months | |

| 0 time | 111 (15.9%) |

| 1 or less | 230 (33.0%) |

| >1 a month but <1 a week | 237 (34.0%) |

| 1+ a week | 119 (17.1%) |

| Mean # of alcohol problems | 1.56 (1.37) |

| Ever use any other drug, including marijuana | 517 (74.3%) |

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Latent Profile Analysis Variables

Baseline Smoking Exposure

Participants were asked how many days they smoked cigarettes in the past 30 days (frequency) and how many cigarettes they smoked on those days (quantity). Smoking frequency was categorized into five levels of smoking frequency (none, <=1 day, 2–7 days, 8–20 days, and 21–29 days). Smoking quantity consisted of four levels (none, <=1 cig, 2–5 cigs, and >5 cigs). In addition, number of years since smoking initiation was assessed by subtracting age at which they reported first trying a cigarette from age at baseline.

Ever Smoked 100 cigarettes

Participants were asked “how many cigarettes have you smoked in your entire life?” at baseline. Responses were dichotomized (0 = never smoked more than 100 cigarettes; 1= have smoked more than 100 cigarettes).

Baseline Nicotine Dependence Symptoms

ND symptoms were from a shortened version of Nicotine Dependence Syndrome Scale (NDSS (Shiffman, Waters, & Hickcox, 2004); modified for use with adolescents) and a modified Fagerstrom Tolerance Questionnaire (mFTQ; Fagerstrom, 1978) targeted for adolescents. Ten items were drawn from the full NDSS scale based on psychometric analyses conducted on an adolescent sample (Sterling et al., 2009), and demonstrated strong internal consistency with the current sample (coefficient alpha = .92). Original items were on a four-point Likert-type scale asking the extent to which each of the symptoms were “not at all true”, “not very true”, “fairly true” or “very true” of the adolescent. The majority of items were highly skewed with most responding “not at all true”. Consequently, the items were dichotomized to reflect symptom endorsement (No – not at all true vs. Yes – any of the three positive responses).

An additional six symptoms were drawn from the mFTQ (coefficient alpha=.77), excluding smoking quantity. Original items were scored on a four-point Likert-type scale, with the exception of the item “Do you smoke more during the first 2 hours than during the rest of the day?” which was binary (yes vs. no). Response options for the mFTQ symptoms were: 1=never to 4=always for “Do you inhale?” which was further dichotomized into “never” vs. any of the other 3 responses; 1=in the evening to 4=within the first 30 minutes for “How soon after you wake up do you smoke your first cigarette?” which was further dichotomized into “within the first 30 minutes” vs. any of the other 3 responses; 1= “Any other cigarette in the evening” vs. 4=” First cigarette in the morning” for “Which cigarette would you hate to give up?”, which was further dichotomized into “first cigarette in the morning” vs. any of the other 3 responses; 1= “not at all difficult” to 4= “very difficult” for “Do you find it difficult to refrain from smoking in places where it is forbidden?”, which was further dichotomized into “not at all difficult” vs. any of the other 3 responses; 1=”never” to 4=”always” for “Do you smoke if you are so ill that you are in bed most of the day?”, which was further dichotomized into “never” vs. any of the other 3 responses.

Alcohol Use and Problems

Participants indicated at baseline how often they drank in the past 3 months and drinking years was assessed by subtracting age at which they reported first trying a drink from age at baseline. Alcohol-use problems were assessed by a sum of 6 items with binary (yes vs. no) response options (e.g., had a problem, or complaints from, your family or friends in the past year as a result of drinking; KR20 = .59).

Other Drug Use

Other drug use at baseline was assessed by asking participants if they had ever used marijuana, cocaine, amphetamines, hallucinogenic drugs, inhalants, heroin, steroid drugs, or misused prescription medication. Any positive responses to the above eight aspects were defined as having ever used other drugs.

Parent and Peer Smoking

Participants were asked at baseline whether at least one parent smokes, and how many close friends (out of five) smoke cigarettes. Adolescents’ reports of parents’ smoking have been shown to be very reliable (Harakeh et al., 2006).

2.2.2. Survival Analysis Outcome

Daily Smoking

The same smoking frequency question was asked at baseline and each follow-up, and was used to assess progression to daily cigarette smoking at 6, 15, 24, 33, and 48-month follow-ups. Number of days smoked in the past 30 days was dichotomized into daily (smoked all days in the past 30 days) vs. non daily smoking (smoked 0–29 of the past 30 days).

2.3 Data Analysis

Latent profile analysis (LPA) and discrete survival analysis were used to identify latent subgroups of adolescent smokers and their survival rates from the 6 month to 48 month follow up with Mplus version 6 software (Muthen & Muthen, 1998–2010). LPA assumes that a heterogeneous population of individuals can be grouped into a finite number of homogenous subgroups from multivariate continuous and categorical data. LPA proceeds by testing a series of models, each specifying an increasing number of classes. The number of retained classes is based on a combination of parsimony and model fit statistics. Indices used to determine the optimal LPA solution included the sample size adjusted Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC), and the adjusted Lo Mendell Rubin likelihood ratio test for model fit (LMRT; Lo, Mendell, & Rubin, 2001) which tests the null hypothesis of no improvement in fit for the model under consideration compared to a model with one less class. The average posterior probability of class membership (the closer to 1, the better) and interpretability of the classes was also considered.

Once the optimal number of LPA classes was determined, a vector of latent class probabilities for each participant was used as an independent variable in a subsequent discrete-time survival analysis. This allowed us to identify the probability of surviving the event (onset of daily smoking) over time for each latent class. Because each participant was assigned to a certain latent class based on a vector of latent class probabilities rather than a fixed observed nominal variable, 20 independent class assignments were generated in R software to validate the survival results among latent classes obtained in Mplus. Finally, gender and age were included as covariates (not as LPA classification variables) to investigate gender and age differences in the identified latent profiles and their respective survival rates.

3. Results

3.1. Latent Profile Analysis

Latent profile models specifying 2–5 classes were fit using smoking exposure, ND symptoms, alcohol use and other substance use measures. The BICs decreased considerably for the 2–4 class models, but increased slightly for the 5-class model, providing support for a 4-class model (BICs = 25063, 24569, 24376 and 24393 for the 2–5 class models, respectively). In addition, a nonsignificant LMRT for a 5-class model (p=.20) suggested that a four-class model fit best. The 4-class average latent class probabilities for most likely latent class membership were .96, .96, .99, and .93 respectively; indicating good prediction of class membership.

3.2. Latent Profiles and Survival Rates

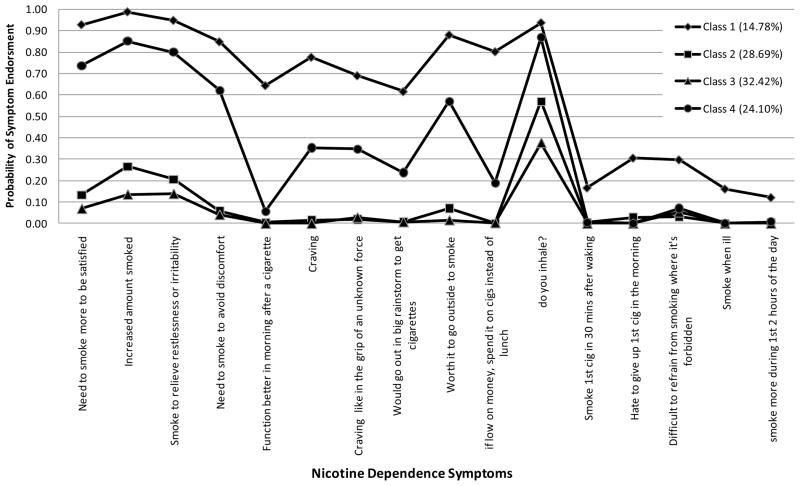

For ease of presentation, LPA estimated probabilities (for categorical LPA variables) and means (for continuous LPA variables) are shown separately in Table 2, which includes the LPA variables for smoking exposure and other risk factors, and Figure 1 which shows the estimated dependence symptom profiles from the LPA. There were no significant differences between classes for the age and gender covariates.

Table 2.

LPA estimated substance use probabilities or means for four classes (N = 697)

| Class 1 (n=103) | Class 2 (n=200) | Class 3 (n=226) | Class 4 (n=168) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| Prob | SE | Prob | SE | Prob | SE | Prob | SE | |

| Smoking Quantity | ||||||||

| None | .04 | .02 | .00 | .00 | .99 | .01 | .13 | .04 |

| <=1 cig per day | .20 | .05 | .85 | .03 | .01 | .01 | .49 | .05 |

| 2–5 cigs per day | .72 | .05 | .15 | .03 | .00 | .00 | .37 | .06 |

| > 5 cigs per day | .04 | .02 | .00 | .01 | .00 | .00 | .01 | .01 |

| Smoking Frequency | ||||||||

| None | .03 | .02 | .00 | .01 | .95 | .02 | .13 | .04 |

| 1 day | .03 | .03 | .45 | .04 | .05 | .02 | .08 | .02 |

| 2–7 days | .18 | .18 | .50 | .04 | .00 | .00 | .52 | .05 |

| 8–20 days | .34 | .34 | .05 | .02 | .00 | .00 | .26 | .05 |

| 21–29 days | .42 | .42 | .00 | .00 | .00 | .00 | .02 | .01 |

| Alcohol-use Frequency | ||||||||

| None | .13 | .13 | .15 | .03 | .28 | .03 | .04 | .03 |

| <= 1 month | .25 | .25 | .34 | .04 | .42 | .03 | .25 | .04 |

| > 1 month & < 1 week | .40 | .40 | .39 | .04 | .24 | .03 | .39 | .04 |

| 1+ per week | .23 | .23 | .13 | .03 | .06 | .02 | .33 | .04 |

| Other drug use | .91 | .03 | .75 | .03 | .58 | .04 | .86 | .03 |

| Had at least one parent who smoked | .56 | .06 | .40 | .04 | .39 | .03 | .47 | .05 |

| Had smoked 100 cigs before | .75 | .06 | .08 | .02 | .02 | .01 | .22 | .06 |

|

|

||||||||

| M | SE | M | SE | M | SE | M | SE | |

|

| ||||||||

| Years since smoking initiation | 3.91 | .22 | 2.94 | .15 | 2.87 | .15 | 3.23 | .17 |

| Years since drinking initiation | 4.26 | .31 | 3.02 | .16 | 3.28 | .17 | 3.35 | .18 |

| Alcohol-related problems | 2.26 | .17 | 1.41 | .10 | 0.94 | .08 | 2.12 | .13 |

| # of close friends who smoke | 3.22 | .18 | 1.71 | .10 | 1.06 | .09 | 2.41 | .15 |

Figure 1.

Estimated probabilities of nicotine dependence symptoms for the four classes of adolescent smokers.

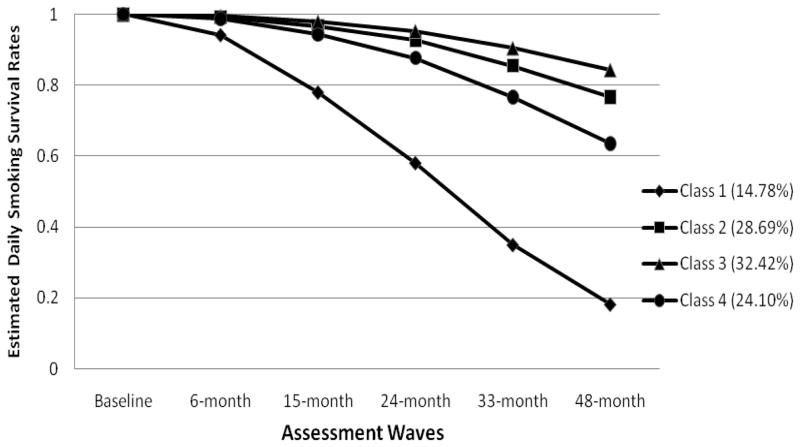

Adolescents in Class 1 (N=103, 15% of the sample; 49% female), with a mean age of 15.70 (SD = .59), had the highest probability of symptom endorsement across all 16 ND symptoms. Adolescents in Class 1 also reported higher smoking exposure at baseline in terms of quantity (e.g., 72% smoked 2–5 cigarettes per day) and frequency (e.g., approximately 42% smoked 21+ days out of the last month). The majority (75%) had smoked more than 100 cigarettes in their lifetime, 23% reported drinking at least once a week in the past 3 months and 91% had used other substances, including marijuana. The majority of adolescent smokers in this class had at least one smoking parent (56%) and an average of 3.22 (SE = .18) close friends who smoke. Estimated mean number of years since starting smoking and drinking and alcohol-related problems were 3.91 (SE = .22), 4.26 (SE = .31), and 2.26 (SE = .17), respectively. Estimated survival rates for daily smoking were .94, .78, .58, .35 and .18 at 6, 15, 24, 33, and 48 months, respectively.

Class 2 included 29% of the sample (N=200) of which 59% were female. The mean age was 15.66 (SD = .61). This class was characterized by low rates of ND symptom endorsement, with the exception of “inhale” which had an estimated 57% endorsement rate. An estimated 85% of adolescents in this class smoked less than one cigarette per day; 50% smoked 2–7 days in the past 30 days. A minority (8%) had smoked more than 100 cigarettes in their lifetime. The estimated mean number of years since starting smoking and drinking were 2.94 (SE = .15) and 3.01 (SE = .16), respectively. More than a third (40%) had at least one smoking parent, and the mean number of close friends who smoke was 1.71 (SE =.10). About 13% drank more than once per week in the past 3 months, had an average of 1.41 alcohol-related problems, and 25% had tried other drugs. Estimated survival rates for daily smoking were .99, .97, .93, .86, and .77 at 6, 15, 24, 33, and 48 months, respectively.

Class 3 (N=226, 32% of the sample; 53% were females), with a mean age of 15.62 (SE = .04) was characterized by the lowest level of smoking (95% did not smoke at all in the past month) and the lowest rate of ND symptom endorsement. The estimated prevalence rates for symptom endorsement were under 10%, with the exception of inhale (estimated 38% endorsement). This class had the lowest prevalence of parent smoking (39%) and the lowest number of friends who smoke (mean=1.06, SE= .09). The estimated mean number of years since starting smoking and drinking were 2.82 (SE =.15), and 3.28 years (SE = .17), respectively, and the mean number of alcohol-related problems was .94 (SE =.08). The majority (95%) did not smoke in the past month, and drank once or less per month in the past 3 months (42%). This class had the lowest levels of past month drinking (28% did not drink at all and 42% drank no more than once in the past month) and other drug use (58%). Estimated survival rates were 1.00, .98, .95, .91, and .84 at 6, 15, 24, 33, and 48 months, respectively.

Class 4 included 24% of the sample (N=168), 58.9% of which were females, and the average age was 15.59 (SD = .65). Adolescents in this class had the second highest level of smoking exposure with 28% reporting smoking on 8 or more days in the past month and 37% reporting smoking 2–5 cigarettes per day. This class was also characterized by its moderate to high rates of ND symptom endorsement, with the exception of the “function better in morning after a cigarette” and mFTQ symptoms of “smoke within 30 minutes of waking”, “hate to give up first cigarette in the morning”, “smoke when ill” and “smoke more during first 2 hours of the day”. Estimated endorsement rates for these symptoms were 3% or less. They reported first smoking and drinking approximately three years earlier (estimated M = 3.23 and 3.35; SE = .17 and .18, respectively), and had an estimated mean of 2.12 (SE=.13) alcohol-related problems. Nearly half (46.7%) had at least one smoking parent and a relatively high number of friends who smoke (M=2.41, SE =.15) friends who smoke. Class 4 also had relatively high rates of other drug use (86%), smoking >100 cigarettes in their life time (22%), and the highest rate of drinking at least once a week in the past 3 months (33%). Estimated survival rates for daily smokers were .99, .94, .88, .77, and .64 at 6, 15, 24, 33, and 48 months, respectively.

Chi-square tests were conducted to compare survival rates for each pair of classes across the 5 assessments, while controlling for effects of gender and age. Results showed that there were no statistically significant differences between class 2 and class 3 (χ2 = 1.85; p = .17), or class 2 and class 4 (χ2 = 2.19; p =.14) in terms of survival rate. All other comparisons between pairs of classes were significant with Benjamini-Hochberg procedure for Type I error rate adjustment for multiple tests (Benjamini & Hochberg, 1995). Similar findings were obtained using the alternative approach, which estimated survival rates from the aggregate of 20 randomized class assignments (see Table 3). Overall, Class 1 had the highest risk of progressing to daily smoking. Compared to class 1, Classes 2, 3, and 4 had a greater likelihood of survival at 48 months. Compared to class 3, class 4 had a lower 48 month survival rate. In addition, males had a significantly lower 48-month survival rate. There were no statistically significant age differences.

Table 3.

Estimated logistic regression coefficients for 48-month survival probability (N = 697)

| b | SD | Odds Ratio | 95%CI-lower | 95% CI-upper | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | −0.49* | 0.12 | 0.61 | 0.48 | 0.78 |

| Age | 0.12 | 0.09 | 1.13 | 0.94 | 1.36 |

| Class 2 vs. Class 1 | 1.14* | 0.18 | 3.12 | 2.19 | 4.45 |

| Class 3 vs. Class 1 | 1.41* | 0.19 | 4.11 | 2.84 | 5.95 |

| Class 4 vs. Class 1 | 0.84* | 0.18 | 2.31 | 1.63 | 3.27 |

| Class 2 vs. Class 4 | 0.30 | 0.18 | 1.35 | 0.95 | 1.92 |

| Class 3 vs. Class 4 | 0.58* | 0.18 | 1.79 | 1.26 | 2.54 |

| Class 3 vs. Class 2 | 0.28 | 0.18 | 1.32 | 0.93 | 1.87 |

significant using the Benjamini-Hochberg procedure for Type I error rate adjustment for multiple tests.

4. Discussion

The present study identified four latent subgroups of adolescent smokers that varied in their rates of smoking, patterns of ND symptom endorsement and use of alcohol and other substances. As expected, differences in these subgroups were related to quantitative increases in smoking exposure and symptom endorsement, and survival rates for daily smoking were lower for the classes with greater smoking exposure and symptom endorsement at baseline. There were two subgroups of adolescent smokers (Classes 2 and 3) who had very low smoking rates and a low probability of symptom endorsement. They were distinguished primarily by their rates of past month smoking. Most (95%) in Class 2 reported smoking at least 1 day in the past month, but only 5% of adolescents in Class 3 reported smoking in the past month. Although both subgroups reported having smoked an average of nearly 3 years, very few (8% of Class 2 and 2% of Class 3) reported smoking at least 100 cigarettes in their life. Compared to classes 1 and 4, they also had the lowest rates of parent and peer smoking and alcohol and other drug use, although adolescents in Class 2 tended to drink more frequently and to have more alcohol related problems compared to Class 3. It is notable that both of these classes showed elevated probabilities of endorsement of symptoms associated with tolerance and withdrawal, despite being infrequent, light smokers. In both subgroups, with the exception of the symptom assessing whether or not they inhale, symptoms with the highest probability of endorsement were “needing smoke more to be satisfied”, “increasing the amount smoked”, and “smoking to relieve restlessness and irritability”. This is consistent with the growing body of evidence that indicates that some ND symptoms, including tolerance and withdrawal symptoms, may be experienced by adolescents who smoke only a few cigarettes on occasion (O’Loughlin et al., 2003; Rose et al., 2010).

Despite some ND symptom endorsement, daily smoking survival rates were relatively high, with only 23% of adolescent in Class 2 and 16% of adolescents in Class 3 reporting having become daily smokers by the 48-month follow up. However, the finding that nearly 20% (N=82) of the adolescents in these two classes ultimately became daily smokers despite low rates of smoking at baseline also supports previous research indicating that ND symptoms are predictive of heavier smoking in the future regardless of smoking rate (Dierker & Mermelstein, 2010). The difference in 48-month survival rates between these classes was not significant, however. It would be interesting to see if these survival rates diverge more at later time points, which would suggest that the observed differences in the class profiles are more important for predicting future smoking behavior.

Classes 1 and 4 reported smoking more frequently and smoking more cigarettes during the times they smoked. Both of these subgroups had the highest probability of symptom endorsement compared to Classes 2 and 3. However, similar to Classes 2 and 3, the symptoms most likely to be endorsed by Classes 1 and 4, with the exception of the symptom assessing whether or not they inhale, were “needing smoke more to be satisfied”, “increasing the amount smoked”, and “smoking to relieve restlessness and irritability”. In addition, Classes 1 and 4 had the longest duration smoking (over three years), and the greatest likelihood of becoming daily smokers by the 48 month follow up. Duration of smoking may be an important factor in the progression to daily smoking. For example, Class 4 reported having smoked for nearly 4 years with 82% smoking daily by 48-months, whereas Class 3, which reported having smoking for less than 3 years, had 16% daily smokers by 48-months. Future research following Class 3 for a longer period of time may show an increase in the likelihood of daily smoking among those in this class who continue to smoke.

There were also striking qualitative differences in ND symptom endorsement between Classes 1 and 4 that suggest differences not only in the likelihood of symptom endorsement, but in the pattern of symptom endorsement. While Class 1 showed an elevated symptom profile across all symptoms, Class 4 showed an elevated symptom profile for a subset of symptoms. Specifically, smoking to function better in the morning and symptoms from the mFTQ tapping a need to smoke in the morning, when ill or in places where smoking is forbidden, as well as and choosing to spend money on cigarettes instead of lunch were much less likely to be endorsed in Class 4. Past research has shown these mFTQ symptoms, particularly time to first cigarette, to be associated most with more severe ND levels (Baker et al., 2007), suggesting that, despite relatively high rates of smoking exposure, adolescents in Class 4 may be considerably less dependent that adolescents in Class 1. In addition, their 48-month daily smoking survival rate was significantly higher at .64 than it was for Class 1 which had a daily smoking survival rate of only .18. Taken together these results suggest that, among adolescents, symptoms measuring a need to smoke in the morning or prioritizing smoking in certain situations may be particularly salient indicators of more severe dependence among heavier, yet non-daily, smokers at high risk for daily smoking.

Another notable difference between Classes 1 and 4 is that Class 4 had the highest frequency of weekly drinking (33% drank at least once a week). In addition, it had a high number of friends who smoke and a high rate of other drug use (86%). This could indicate that adolescents in Class 4 may be more social smokers who smoke primarily when they are drinking with friends. In fact, follow up analyses to better characterize smoking patterns for these two classes indicated that Class 4 adolescents smoked 1.7 days per week on average compared to 4.6 days per week for Class 1 adolescents, and smoked fewer cigarettes on those days (mean smoking quantity of 0.4 cigarettes compared to 2.1 cigarettes for Class 1 adolescents). The lack of endorsement of symptoms related to smoking in the morning also provides some support for this interpretation as smoking in the morning may be more likely to occur when the adolescent is alone and not drinking alcohol. The young social smoker who tends to smoke lightly, in the evening, and primarily when drinking has been identified in previous research (Krukowski, Solomon, & Naud, 2005), however, little is known about ND symptom profiles for this type of smoker. The results of the current study suggests that both the pattern of ND symptom endorsement and the likelihood of becoming a daily smoker differs for this type compared to other more frequent and heavier smokers. Consequently, adolescents who engage in a number of other risk behaviors, but tend to smoke primarily for social reasons may be less likely to develop more chronic daily smoking patterns. Nevertheless, 36% of these social smokers were likely to be daily smoker by 48-months, and their steeper decline in survival rates compared to other lighter smoking classes suggests that there may be significant risk for future chronic smoking in this group beyond the 48 month follow up. In addition, they may be at increased risk for problems associated with alcohol and other drug use. As a result, they remain important targets for interventions aimed at reducing smoking, alcohol and other drug use.

As with any study, there are some limitations that should be noted. First, although the classes appeared to show differences in predicting future daily smoking, we could not replicate the LPA in an independent sample. Replication could provide us with more confidence in the reliability of the profiles found in this study, and would be important to investigate in future research. Future research might also examine the stability of the profiles over time. Second, we did not have data investigating future smoking behavior into young adulthood when risk for chronic smoking and ND is still high. As a result we could not determine whether adolescents in the classes that had high nondaily survival rates, ultimately became daily smokers. Finally, the alcohol problems items had low reliability (KR20 = .59). Therefore some caution is warranted in the interpretation of results involving this measure.

In sum, this study identified four distinct subgroups of smokers with different patterns of smoking behavior, ND symptoms and other substance use. Quantitative differences in ND symptom endorsement showed that rates of symptom endorsement increased with greater smoking exposure and that heavier smoking adolescents with high symptom endorsement, particularly the need to smoke in the morning, were most likely to become daily smokers 48 months later. Qualitative differences revealed a subgroup of social smokers with relatively high levels of smoking exposure and symptom endorsement, with the exception of symptoms that suggest more severe ND, and high levels of alcohol and other substance use, but were considerable less likely to become daily smokers. In terms of assessment, morning smoking symptoms and symptoms that indicating smoking as a high priority potentially may be used to quickly identify adolescent non-daily smokers with more severe dependence and very high risk of daily smoking. It is sobering as well to note that the overwhelming majority of adolescents who smoked frequently at age 15–16 progressed to daily smoking. Thus, patterns of smoking during mid-adolescence are strong indicators of continued smoking through late adolescence. In terms of intervention, a focus on skills for avoiding social situations that involve the use of alcohol and other drugs and reducing peer smoking influences may be particularly effective for reducing smoking and other substance use among social smokers, while adolescents who already show more severe levels of dependence may benefit from additional pharmacological support to reduce dependence symptoms when attempting to quit.

Figure 2.

Estimated daily smoking survival curves for the four classes of adolescent smokers.

Highlights.

Identified latent adolescent smoking groups using nicotine dependence symptoms, risk factors.

Survival analysis was used to determine probability of future daily smoking among latent groups.

Four latent profiles were identified varying in smoking, risk factors and symptom patterns.

Heavier smokers with morning smoking symptoms were most likely to smoke daily at 48 months.

A social smoker subgroup that drank frequently was less likely to smoke daily at 48 months.

Acknowledgments

Role of Funding Sources

Funding for this research was provided by Award Number P01CA098262 from the National Cancer Institute, by grants R01 DA022313-01A2, R01 DA022313-02S1, R21DA024260 and R21 DA029834-01A1 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse, and by Center Grant P50 DA010075 awarded to Penn State University. Theses funding institutions had no role in the study design, collection, analysis or interpretation of the data, writing the manuscript, or the decision to submit the paper for publication.

The authors would like to thank Sui Chi Wong of the University of Illinois, Chicago for providing assistance with the data analysis.

Footnotes

Contributors

Jennifer Rose planned the core analyses, conducted the literature review and wrote the majority of the manuscript. Chien-Ti Lee conducted the analyses and contributed significantly to the writing of the Results section. Arielle Selya conducted the analyses to validate the survival results among latent classes and assisted with revisions to the earlier drafts of this manuscript. Lisa Dierker designed the study in conjunction with the Jennifer Rose, and provided revisions to the manuscript. Robin Mermelstein collected the data used in this study and provided revisions to the manuscript. All authors contributed to and have approved the final manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

All authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Jennifer S. Rose, Wesleyan University

Chien-Ti Lee, Wesleyan University.

Lisa C. Dierker, Wesleyan University

Arielle S. Selya, Wesleyan University

Robin J. Mermelstein, University of Illinois, Chicago

References

- APA. Diagnostic and statistical manual of the mental disorders - IV. Washington, D.C: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Baker TB, Piper ME, McCarthy DE, Bolt DM, Smith SS, Kim S-Y, et al. Time to first cigarette in the morning as an index of ability to quit smoking: Implications for nicotine dependence. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2007;9(Suppl 4):S555–S570. doi: 10.1080/14622200701673480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: A practical and powerful approach to multiple significance testing. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society. 1995;B57:289–300. [Google Scholar]

- CDC. Targeting tobacco use: The nation’s leading cause of preventable death 2007. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2009. Reteived from http://www.cdc.gov/NCCDPHP/publications/aag/osh.htm). Retrieved May 11, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Dierker L, Donny E, Tiffany S, Colby SM, Perrine N, Clayton RR. The association between cigarette smoking and DSM-IV nicotine dependence among first year college students. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2007;86:106–114. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.05.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dierker L, Mermelstein R. Early emerging nicotine dependence symptoms: A signal of propensity for chronic smoking behavior among experimental adolescent smokers. Journal of Pediatics. 2010;156(5):818–822. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2009.11.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiFranza JR, Savageau JA, Fletcher K, Ockene JK, Rigotti NA, McNeill AD, et al. Measuring the Loss of Autonomy Over Nicotine Use in Adolescents: The DANDY (Development and Assessment of Nicotine Dependence in Youths) Study. 2002;156(4):397–403. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.156.4.397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fagerstrom KO. Measuring the degree of physical dependency to tobacco smoking with reference to individualization of treatment. Addictive Behaviors. 1978;3:235–241. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(78)90024-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goedeker KC, Tiffany ST. On the Nature of Nicotine Addiction: A Taxometric Analysis. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2008;117(4):896–909. doi: 10.1037/a0013296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gervais A, O’Loughlin J, Meshefedjian G, Bancej C, Tremblay M. Milestones in the natural course of onset of cigarette use among adolescents. Canadian Medical Association Journal. 2006;175(3):255–261. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.051235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harakeh Z, Engels RC, Vries H, Scholte RH. Correspondence between proxy and self-reports on smoking in a full family study. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2006;84:40–47. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2005.11.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu MC, Davies M, Kandel DB. Epidemiology and Correlates of Daily Smoking and Nicotine Dependence Among Young Adults in the United States. American Journal of Public Health. 2006;96(2):299–308. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.057232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu MC, Griesler PC, Schaffran C, Kandel D. Risk and protective factors for nicotine dependence in adolescence. Journal of Child Psychology & Psychiatry. 2011;52:1063–1072. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2010.02362.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu MC, Muthen BO, Schaffran C, Griesler P, Kandel D. Developmental trajectories of criteria of nicotine dependence in adolescence. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2008;98:94–104. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.04.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE. Smoking stops declining and shows signs of increasing among younger teens. University of Michigan News Service; Ann Arbor, MI: 2010. Retrieved 08/08/2011 from http://www.monitoringthefuture.org. [Google Scholar]

- Kandel DB, Hu MC, Griesler PC, Schaffran C. On the development of nicotine dependence in adolescence. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2007;91(1):26–39. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.04.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleinjan M, Wanner B, Vitaro F, Van den Eijnden RJJM, Brug J, Engels RCME. Nicotine dependence subtypes among adolescent smokers: Examining the occurrence, development and validity of distinct symptom profiles. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2010;24(1):61–74. doi: 10.1037/a0018543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krukowski R, Solomon L, Naud S. Triggers of Heavier and Lighter Cigarette Smoking in College Students. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2005;28(4):335–345. doi: 10.1007/s10865-005-9003-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leeman RF, Schepis TS, Cavallo DA, McFetridge AK, Liss TB, Krishnan-Sarin S. Nicotine dependence severity as a cross-sectional predictor of alcohol-related problems in a sample of adolescent smokers. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2010;12(5):521–524. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntq024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lo YT, Mendell NR, Rubin DB. Testing the number of components in a normal mixture. Biometrika. 2001;88(3):767–778. [Google Scholar]

- Muthen LK, Muthen BO. Mplus user’s guide. 6. Los Angeles, CA: Muthen & Muthen; 1998–2010. [Google Scholar]

- O’Loughlin J, DiFranza J, Tyndale RF, Meshefedjian G, McMillan-Davey E, Clarke PBS, et al. Nicotine-dependence symptoms are associated with smoking frequency in adolescents. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2003;25(3):219–225. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(03)00198-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Loughlin J, DiFranza J, Tyndale RF, Meshefedjian G, McMillan-Davey E, Clarke P, et al. Nicotine-dependence symptoms are associated with smoking frequency in adolescents. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2003;25:219–225. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(03)00198-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prokhorov AV, Pallonen UE, Fava JL, Ding L, Niaura R. Measuring nicotine dependence among high-risk adolescent smokers. Addictive Behaviors. 1996;21:117–127. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(96)00048-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose J, Dierker L. DSM-IV Nicotine Dependence Symptom Characteristics for Recent Onset Smokers. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2010;12:278–286. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntp210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose J, Dierker L, Donny E. Nicotine dependence symptoms among recent onset adolescent smokers. Drug & Alcohol Dependence. 2010;106:126–132. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2009.08.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scherrer JF, Xian H, Pan H, Pergadia ML, Madden PAF, Grant JD, et al. Parent, sibling and peer influences on smoking initiation, regular smoking and nicotine dependence. Results from a genetically informative design. Addictive Behaviors. (0) doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2011.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiffman S, Waters AJ, Hickcox M. The nicotine dependnece syndrome scale: A multidimensional measure of nicotine dependence. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2004;6(2):327–348. doi: 10.1080/1462220042000202481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sterling KL, Mermelstein R, Turner L, Diviak K, Flay B, Shiffman S. Examinging the psychometric properties and predictive validity of a youth -specific version of the Nicotine Dependence Syndrome Scale (NDSS) among teens with varying levels of smoking. Addictive Behaviors. 2009;34:616–619. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2009.03.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Storr CL, Reboussin BA, Anthony JC. The Fagerstrom test for nicotine dependence: A comparison of standard scoring and latent class analysis approaches. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2005;80(2):241–250. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Storr CL, Zhou H, Liang K-Y, Anthony JC. Empirically derived latent classes of tobacco dependence syndromes observed in recent-onset tobacco smokers: Epidemiological evidence from a national probability sample survey. 2004;6(3):533–545. doi: 10.1080/14622200410001696493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]