Abstract

Objective

To provide quantitative measurement and analysis of the frequency with which patients contact emergency primary healthcare services in Norway for psychiatric illness, including substance misuse. Characteristics of the patient group and their contact times were also addressed.

Design

Cross-sectional observational study.

Setting

Data were collected from one district-based and one city-based casualty clinic in Norway.

Subjects

Patients seeking medical care during the whole of 2006.

Main outcome measures

Patients’ diagnoses, age, gender, and time of contact.

Results

Diagnoses related to psychiatric illness were found in 2.7% of all events at the casualty clinics, but were relatively more frequent at night (5.6%) and for home visits and out-of-office emergency responses combined (8.4%). Prevalence was almost doubled during the July holiday month. Prevalence remained relatively constant between ages 15 and 59. The most frequently diagnosed subgroups were depression/suicidal behaviour, anxiety, and substance abuse (21.3%) of which 76.8% was alcohol-related. Gender and age differences within diagnostic subgroups were identified. For example, substance abuse was more prevalent for men, while anxiety was more prevalent for women.

Conclusion

Psychiatric illness and substance misuse have relatively low presentation rates at Norwegian casualty clinics, compared with established daytime attendance at general practitioners. However, the prevalence increases during periods with lowered availability of primary and specialist psychiatric healthcare. These data have implications for the allocation of resources to patient treatment and provide a foundation for future research into provision of emergency healthcare services for this group of patients.

Keywords: After-hours care, emergency medical services, family practice, physician's practice patterns, primary healthcare, psychiatry

Caring for patients with problems related to psychiatric diseases or substance abuse is a major challenge to health workers in emergency primary healthcare. The occurrence and the nature of the problems encountered in Norway are unknown.

Psychiatric and substance misuse-related problems are relatively seldom presented at casualty clinics in Norway, but their prevalence seems to increase at night-time.

Substance abuse, depression/suicidal behaviour, and anxiety were the most commonly used diagnoses, and they were mostly given to patients in the age groups 15–59 years.

Most events related to substance misuse are due to alcohol.

Patients with problems related to psychiatric diseases or substance abuse constitute a considerable proportion of frequent users of emergency medical services [1], [2]. In Norway, caring for patients with these types of problems is a major challenge to health workers in emergency care [3]. There is an ongoing discussion about how best to organize medical care to this patient group [4], [5]. However, casualty clinics and emergency departments are recognized as important places for health workers to meet in particular people with substance misuse disorders [6–8].

Norway has a two-level public healthcare system, with a marginal private sector. The municipalities of Norway are legally in charge of primary healthcare, including local emergency medical services for all inhabitants round the clock [9]. The emergency medical service is usually managed by the regular general practitioners’ (rGPs) surgeries during office hours and by municipality maintained out-of-hours duties by general practitioners (GPs) during evenings, nights, and weekends, often based in local casualty clinics [10]. The GPs act as gatekeepers for the specialist healthcare system, and patients are almost always assessed by a GP before they are admitted to any part of the specialist healthcare system, including psychiatric care.

In Norway there is a general belief that patients with psychiatric diseases or substance misuse relate poorly to their regular GPs and that they often attend casualty clinics for a variety of medical problems. GPs working out of hours are responsible for the majority of acute admissions to psychiatric wards [11], [12]. Prevalence studies have shown that 5–12% of GPs’ daytime consultations in Norway are related to psychiatry [13], [14]. A recent report states that for out-of-hours services the corresponding prevalence is 4% [15].

In this study we wanted to estimate the prevalence of contacts related to psychiatry and substance misuse compared with contacts due to other issues encountered within the emergency primary medical care system in Norway. We also wanted to study characteristics of this patient group and their time of attendance at casualty clinics.

Material and methods

Larvik and Lardal casualty clinic and Nordhordland casualty clinic were selected to participate in the study. Both clinics are open 24 hours/day throughout the week. In 2006 they used the same computer software (Infodoc) for patient recording. Larvik and Lardal casualty clinic is a joint venture between the city of Larvik and municipality of Lardal. The casualty clinic shares the same premises as the emergency department at the local hospital. In January 2006 Larvik had 41 211 and Lardal 2 445 inhabitants. Nordhordland casualty clinic is a large district-based general practice cooperative. The participating municipalities are Austrheim, Fedje, Lindås, Masfjorden, Meland, Modalen, and Radøy (range 354 to 13 285 inhabitants in 2006, total 29 021).

We used a tailor-made computer program that automatically searched the patient records for diagnoses filed in 2006. If a diagnosis was filed that year, the following information was extracted from the accompanying billing cards in the medical record's software system: date and time of day for initiating the billing card, the patient's gender and year of birth, the municipality, the two first diagnoses, and reimbursement codes.

No information that could identify the patient was recorded, but each patient was automatically assigned a unique code based on his/her personal identity number. This allowed us to retain anonymity whilst tracing whether the same person had been involved in several contacts during 2006. Billing cards issued for the same patient with less than a two-hour interval were considered to be duplicates. The billing card with the most complete information was then used. In cases where the duplicates had different diagnoses all billing cards were kept, and the contacts regarded as unique.

The type of contact could be identified from the reimbursement codes. We focused on consultations, home visits, and out-of-building emergency responses. In this article we refer to all chosen contacts between doctor and patient as “events”, and home visits and emergency responses as “out-of-office events”.

The International Classification of Primary Care-2 (ICPC-2) [16] was used for diagnoses by both clinics. Psychiatric problems and substance misuse are coded in chapter P of ICPC-2. This chapter consists of 26 codes for psychological symptoms and complaints and 17 codes for psychiatric diagnoses. Before bivariate analyses we grouped the codes in clusters in accordance with the type or group of symptoms they reflected (Table I).

Table I.

Subgroups of the P-chapter in ICPC-2.

| Subgroup | Code(s) |

| Depression/suicidal behaviour | P03, P76, P77 |

| Substance abuse | P15, P16, P17, P18, P19 |

| Anxiety | P01, P27, P74, P75, P79, P82 |

| Acute stress reaction | P02 |

| Unspecified P-diagnoses | P28, P29, P99 |

| Psychosis | P71, P72, P73, P98 |

| Sleep disturbance | P06 |

| Memory disturbance | P20, P70 |

| Others | P04, P05, P07, P08, P09, P10, P11, P12, P13, P22, P23, P24, P25, P78, P80, P81, P85, P86 |

The data were analysed using SPSS 15.0. Differences were tested with Pearson chi-squared tests. Statistically significance was accepted at p < 0.05.

The project was approved by the Regional Committee for Medical Research Ethics and the Norwegian Social Science Data Services. Permission to use patient information was given by the Norwegian Directorate for Health Affairs.

Results

Table II shows the main characteristics of the two participating casualty clinics. The districts were similar regarding age and gender distribution, and the rate of P-diagnoses used as first diagnosis. Hence the events from the two clinics were merged for further analyses.

Table II.

Population, age and gender distribution, consultations, and psychiatric diagnoses (ICPC P-diagnoses) of the two participating out-of-hours districts (casualty clinics), consisting of nine local municipalities.

| After-hours district/casualty clinics |

||

| Nordhordland | Larvik and Lardal | |

| Total number of inhabitants (1 January 2006) | 29 021 | 43 656 |

| Gender (% of men) | 50.4 | 49.2 |

| Age distribution (%) | ||

| 0–4 | 6.4 | 5.3 |

| 5–14 | 14.9 | 12.9 |

| 15–29 | 19.2 | 17.6 |

| 30–44 | 19.9 | 20.5 |

| 45–59 | 20.6 | 21.4 |

| 60 + | 19.0 | 22.3 |

| Events | ||

| Total (n) | 14 392 | 12 816 |

| Total (rate) | 496 | 294 |

| Consultations (n) | 14 030 | 12 485 |

| Consultations (rate) | 483 | 286 |

| Out-of-office events (n) | 362 | 331 |

| Out-of-office events (rate) | 12 | 27 |

| P-diagnoses as first diagnosis (n) | 315 | 413 |

| P-diagnoses as first diagnosis (rate) | 11 | 9 |

Note: Rate denotes events per 1 000 inhabitants per year.

A total of 27 208 events were registered, and 728 events had a P-diagnosis as first diagnosis (2.7%). Out-of-office events accounted for 8% of these cases (n = 58). Of all events given two diagnoses (n = 2 723), 6.6% had a second diagnosis from the chapter P (n = 180). Apart from the chapters covering problems related to pregnancy, and male and female genitals, diagnoses from all the other diagnostic chapters were used with a P-diagnosis second. Half (n = 87) concurred with a first P-diagnosis. Other prevalent combinations were P-diagnoses second to first diagnoses from the chapters covering neurological symptoms (n = 16) and general symptoms (n = 15). There was a considerable overlap between P-diagnoses used as first and second diagnosis. As our primary interest was the share of total events compared with other chapters, we focused on first diagnoses, yielding 728 events for further analysis.

Table III shows the events by age group. The age distribution among events given a P-diagnosis as first diagnosis differed from the age distribution in both the population and across all events. P-diagnoses were seldom used for the youngest patients, whilst the prevalence was relatively constant for ages between 15 and 59 years. Out-of -office events in general were mainly related to elderly people. Among out-of-office events with a P-diagnosis, a third occurred in the age group 15–29 years. The prevalence of P-diagnoses as first diagnosis was higher in out-of-office events (8.4%) than in consultations (2.5%) (p < 0.001).

Table III.

Distribution of age in the population (n =72 667) and among events (n = 27 202).

| Age group (years) |

||||||||||||||

| 0–4 |

5–14 |

15–29 |

30–44 |

45–59 |

60 + |

Total |

||||||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Population | 4 180 | 5.8 | 9 951 | 13.7 | 1 3230 | 18.2 | 14 706 | 20.2 | 15 325 | 21.1 | 15 286 | 21.0 | 72 677 | 100 |

| Events | ||||||||||||||

| Total | 4 071 | 15.0 | 3 330 | 12.2 | 5 621 | 20.7 | 4 834 | 17.8 | 4 036 | 14.8 | 5 310 | 19.5 | 2 7202 | 100 |

| Consultations | 4 053 | 15.3 | 3 310 | 12.5 | 5 542 | 20.9 | 4 784 | 18.0 | 3 950 | 14.9 | 4 870 | 18.4 | 26 509 | 100 |

| P-diagnoses as first diagnoses in consultations | 6 | 0.9 | 10 | 1.5 | 220 | 32.8 | 197 | 29.4 | 156 | 23.3 | 81 | 12.1 | 670 | 100 |

| Out-of-office events | 18 | 2.6 | 20 | 2.9 | 79 | 11.4 | 50 | 7.2 | 86 | 12.4 | 440 | 63.5 | 693 | 100 |

| P-diagnoses as first diagnoses in out-of-office events | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 1.5 | 19 | 32.8 | 8 | 13.8 | 12 | 20.7 | 18 | 31.0 | 58 | 100 |

Note: Six events are excluded due to unknown age.

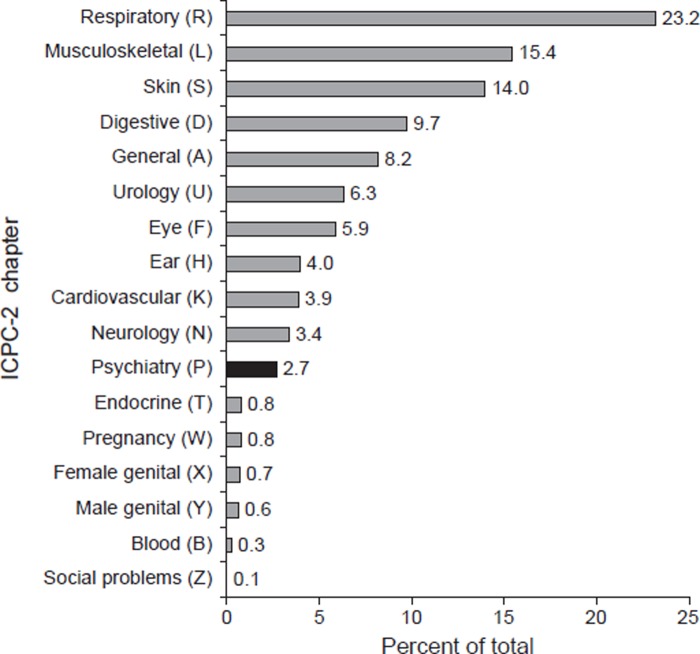

Figure 1 shows the distribution of first diagnoses by ICPC-2 chapters. Nearly a quarter of all events were related to the respiratory system, while musculoskeletal and skin problems ranked second and third. P-diagnoses were ranked eleventh (2.7%). However, the number of events given psychiatric diagnoses had approximately the same percentage as cardiovascular or neurological problems.

Figure 1.

Distribution (%) of ICPC-2 chapters of all first diagnoses used at the casualty clinics in 2006 (n = 27 208).

Table IV shows clusters of psychiatric diagnoses by gender and age. The most commonly used diagnoses were related to substance abuse, depression/suicidal behaviour, or anxiety. Substance abuse accounted for nearly a third of all events among men. Among women the events were more evenly distributed between diagnostic groups. Nevertheless, anxiety accounted for a quarter of the female cases (25.5%), with depression/suicidal behaviour second (21.4%). For men 66.4% of the events were in the group 15–44 years; for women it was 55.6%.

Table IV.

Total, age group, and gender distribution of the subgroups of psychiatric diagnosis (ICPC-2 P-diagnosis, n = 702).

| Total | Men |

Women |

|||||||||||||||||||||

| (n = 702) | Age groups (years) |

Age groups (years) |

|||||||||||||||||||||

| 0–14 |

15–29 |

30–44 |

45–59 |

60 + |

Total |

0–14 |

15–29 |

30–44 |

45–59 |

60 + |

Total |

||||||||||||

| % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | |

| Depression/suicidal behaviour | 20.4 | 1 | 1.3 | 23 | 30.7 | 22 | 29.3 | 23 | 30.7 | 6 | 8.0 | 75 | 1 | 1.5 | 20 | 29.4 | 16 | 23.5 | 21 | 30.9 | 10 | 14.7 | 68 |

| Substance abuse | 22.1 | 2 | 1.7 | 42 | 36.5 | 45 | 39.1 | 21 | 18.3 | 5 | 4.3 | 115 | 1 | 2.5 | 17 | 42.5 | 13 | 32.5 | 5 | 12.5 | 4 | 10.0 | 40 |

| Anxiety | 19.4 | 1 | 1.8 | 22 | 40.0 | 20 | 36.4 | 8 | 14.5 | 4 | 7.3 | 55 | 2 | 2.5 | 26 | 32.1 | 17 | 21.0 | 15 | 18.5 | 21 | 25.9 | 81 |

| Acute stress reaction | 7.5 | 0 | 0.0 | 7 | 29.2 | 13 | 54.2 | 3 | 12.5 | 1 | 4.2 | 24 | 0 | 0.0 | 15 | 51.7 | 6 | 20.7 | 7 | 24.1 | 1 | 3.4 | 29 |

| Unspesific P-diagnoses | 11.5 | 2 | 5.4 | 17 | 45.9 | 11 | 29.7 | 5 | 13.5 | 2 | 5.4 | 37 | 1 | 2.3 | 14 | 31.8 | 10 | 22.7 | 16 | 36.4 | 3 | 6.8 | 44 |

| Psychosis | 8.8 | 0 | 0.0 | 10 | 26.3 | 9 | 23.7 | 16 | 42.1 | 3 | 7.9 | 38 | 0 | 0.0 | 4 | 16.7 | 8 | 33.3 | 10 | 41.7 | 2 | 8.3 | 24 |

| Sleep disturbance | 3.6 | 2 | 15.4 | 6 | 46.2 | 1 | 7.7 | 2 | 15.4 | 2 | 15.4 | 13 | 1 | 8.3 | 4 | 33.3 | 2 | 16.7 | 2 | 16.7 | 3 | 25.0 | 12 |

| Memory disturbance | 4.1 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 2 | 12.5 | 14 | 87.5 | 16 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 7.7 | 12 | 92.3 | 13 |

| Others | 2.6 | 1 | 9.1 | 2 | 18.2 | 5 | 45.4 | 0 | 0.0 | 3 | 27.3 | 11 | 1 | 14.3 | 5 | 71.4 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 14.3 | 0 | 0.0 | 7 |

| Total | 100.0 | 9 | 2.3 | 129 | 33.6 | 126 | 32.8 | 80 | 20.8 | 40 | 10.4 | 384 | 7 | 2.2 | 105 | 33.0 | 72 | 22.6 | 78 | 24.5 | 56 | 17.6 | 318 |

Note: Cases with missing information on gender (n = 26) are excluded from the table.

The prevalence of P-diagnosis as first diagnosis varied over the year, with July (n = 102) and December (n = 81) as the months with the highest prevalence. Approximately half of the events (n = 362) occurred between 4 p.m. on Friday and 8 a.m. on Monday. Problems related to psychiatry or substance abuse were relatively more commonly presented during the night (p < 0.001). They accounted for 1.8% of total events during the daytime, 2.4% of events in the evening, and 5.6% of events during the night.

The subgroup of substance abuse (n = 155) differed from the other subgroups in many respects (data not shown). A third of total night-time events were related to substance abuse. Almost half of the events in this subgroup (n = 72) occurred between 4 p.m. on Friday and 8 a.m. on Sunday. Alcohol accounted for 76.8% of the total events in the subgroup (P15 and P16, n = 119).

Discussion

A first diagnosis related to psychiatry and substance abuse was found in 2.7% of all events at the casualty clinics, and the most frequent diagnoses were due to substance abuse, depression/suicidal behaviour, or anxiety. The prevalence of P-diagnoses was relatively constant throughout the ages 15–59 years and almost absent in patients younger than 15 years. The data were collected at two casualty clinics representing different organizational models. The total rate of events in the two clinics differed, possibly due to differences in availability of rGPs and daytime attendance at the casualty clinic. However, the findings from the clinics were similar regarding use of diagnoses from the chapter P of ICPC-2, suggesting that the results might be generalized to Norwegian casualty clinics. The main findings also compare well with numbers previously reported from out-of-hours services [15].

ICPC-2 is not unambiguous for classification of symptoms and diseases. We have probably missed some cases of deliberate self-harm, intoxication, and anxiety presented as physical symptoms, thus somewhat underestimating the actual prevalence. We focused on first diagnosis. By convention, the dominant problem reported by the patient is written first. Due to concurrence of P-diagnoses, to include the events with a P-diagnosis as second diagnosis would have been deceptive regarding age and gender distribution of the patient group. Adding P-diagnoses given as second diagnoses would also have overestimated the actual proportion of events given a diagnosis from the chapter P when compared with other chapters in ICPC-2.

The events were registered retrospectively by searching diagnoses filed in the billing cards in the computer software. The billing cards are usually written at the end of the patient–doctor contact. Hence, the time registered for initiating the billing card gives a good estimate for time of contact with the patient.

We found that psychiatric diagnoses are seldom given at casualty clinics, although they are more frequent in out-of-office events than in consultations. Other studies have shown that approximately 5% of home visits are caused by psychiatric problems [17], [18], figures comparable to our finding of 8.4% of all out-of-office events. Out-of-office events often have a higher priority grade due to higher urgency of the medical problem. The higher prevalence in out-of-office events may therefore indicate that out-of-hours services play an important role in emergency psychiatric care.

Even if the P-chapter was relatively seldom used, it was used approximately as much as the chapter covering cardiovascular problems. A study of Norwegian out-of-hours services found that the lowest priority grade was given in a minimum 65% of the encounters [9], of which a major proportion would receive respiratory and musculoskeletal diagnoses. Another study showed that acute psychiatry is among the emergency situations most commonly experienced by GPs participating in Norwegian out-of-hours services [19]. Nearly all GPs (92%) had experienced at least one emergency situation related to psychiatric illness during the last year. In addition, 69% had experienced an intoxication or overdose. This might imply that even if the P-diagnoses are seldom used, the urgency of the problems presented may be high.

The majority of out-of-office events with P-diagnoses appeared in the age group 15–29 years. This probably reflects the young adulthood onset of most psychiatric diseases. In addition, binge drinking and use of illegal drugs are more common among young people, and this may create a need for medical help and also indirectly contribute to the need for acute care by destabilizing well-managed psychiatric illness.

We found gender differences in the subgroups of substance abuse and anxiety. Men between 15 and 45 years accounted for 56% of the total number of patients receiving substance abuse-related diagnoses, probably reflecting the higher prevalence and more aggressive behaviour related to substance misuse among men. Diagnoses related to anxiety were more common among women than men, which might reflect both differences in prevalence of the disease and a possible higher tendency among men to report anxiety as a physical symptom.

The fact that events due to psychiatry are relatively more common during the night and particularly prevalent during July (a holiday month), might reflect the importance of the casualty clinics as a supplement when the regular GPs and professional psychiatric services are unavailable. Opening hours of psychiatric healthcare may also not be adapted to these patients’ needs, a viewpoint shared by psychiatric specialists [20].

In conclusion, psychiatric and substance misuse-related problems are relatively seldom presented at casualty clinics in Norway, but their prevalence seems to increase at times of decreased availability of primary and specialist psychiatric healthcare. Alcohol plays an important role as contributor to the contacts with casualty clinics, especially during the night and at weekends. Further research is needed to establish the appropriateness and quality of the services at casualty clinics.

Acknowledgements

The project was funded by the National Centre for Emergency Primary Health Care.

Conflict of interest

None.

References

- 1.Kennedy D, Ardagh M. Frequent attenders at Christchurch Hospital's Emergency Department: A 4-year study of attendance patterns. N Z Med J. 2004;117:U871. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kne T, Young R, Spillane L. Frequent ED users: Patterns of use over time. Am J Emerg Med. 1998;16:648–52. doi: 10.1016/s0735-6757(98)90166-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nore AK, Ommundsen OE, Steine S. Hvordan skille mellom sykdom, skade og rus på Legevakten? [How can we distinguish between illness, injury or intoxication in the emergency department? English summary] Tidsskr Nor Laegeforen. 2001;121:1055–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Neumann T, Neuner B, Weiss-Gerlach E, Tonnesen H, Gentilello LM, Wernecke KD, et al. The effect of computerized tailored brief advice on at-risk drinking in subcritically injured trauma patients. J Trauma. 2006;61:805–14. doi: 10.1097/01.ta.0000196399.29893.52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gråwe RW, Ruud T, Bjorngaard JH. Alternative akuttilbud i psykisk helsevern for voksne [Alternative acute interventions in mental health care. English summary] Tidsskr Nor Laegeforen. 2005;125:3265–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cherpitel CJ. Emergency room and primary care services utilization and associated alcohol and drug use in the United States general population. Alcohol Alcohol. 1999;34:581–9. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/34.4.581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cherpitel CJ. Drinking patterns and problems: A comparison of primary care with the emergency room. Subst Abus. 1999;20:85–95. doi: 10.1080/08897079909511397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Charalambous MP. Alcohol and the accident and emergency department: A current review. Alcohol Alcohol. 2002;37:307–12. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/37.4.307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hansen EH, Hunskaar S. Development, implementation, and pilot study of a sentinel network (“The Watchtowers”) for monitoring emergency primary health care activity in Norway. BMC Health Serv Res. 2008;8:62. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-8-62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nieber T, Hansen EH, Bondevik GT, Hunskaar S, Blinkenberg J, Thesen J, et al. Organisering av legevakt [Organization of Norwegian out-of-hours primary health care services. English version] Tidsskr Nor Laegeforen. 2007;127:1335–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ruud T. Gråwe RW. Hatling T. [Emergency psychiatric treatment in Norway – results from a multi center study]. Report No. A310. Supported by the Norwegian Directorate of Health. Oslo:: SINTEF; 2006. Akuttpsykiatrisk behandling i Norge – resultater fra en multisenterstudien. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tørrissen T. Tvangsinnleggelser i en akuttpsykiatrisk post [Involuntary admissions to an acute psychiatric ward. English version] Tidsskr Nor Laegeforen. 2007;127:2086–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grimsmo A, Hagman E, Faiko E, Matthiessen L, Njalsson T. Patients, diagnoses and processes in general practice in the Nordic countries: An attempt to make data from computerised medical records available for comparable statistics. Scand J Prim Health Care. 2001;19:76–82. doi: 10.1080/028134301750235277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Statistics Norway. Allmennlegetjenesten [The general practitioner services] Available at: http://www.ssb.no/alegetj/tab-2006-10-09-04.html.

- 15.Nossen JP. Oslo:: The Norwegian Labour and Welfare Administration; 2007. Hva foregår på legekontorene? Konsultasjonsstatistikk for 2006 [What happens at the GPs’ surgeries? Consultation statistics for 2006]. Report No. 4/2007. [Google Scholar]

- 16.ICPC. Available at: http://www.kith.no/templates/kith_WebPage____1186.aspx.

- 17.Iveland E, Straand J. 337 sykebesøk på dagtid fra Oslo Legevakt [337 home calls during daytime from the emergency medical center in Oslo. English summary] Tidsskr Nor Laegeforen. 2004;124:354–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Straand J, Sandvik H. Home visits in general practice – most often for elderly patients: A report from the Møre & Romsdal Prescription Study. Nor J Epidemiol. 1998;8:127–32. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zakariassen E, Sandvik H, Hunskaar S. Norwegian regular general practitioners’ experiences with out-of-hours emergency situations and procedures. Emerg Med J. 2008;25:528–33. doi: 10.1136/emj.2007.054338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Berg JE. Når på døgnet legges pasienter inn i en akuttpsykiatrisk avdeling? [When during the day are patients admitted to the emergency psychiatric department? Tidsskr Nor Laegeforen. 2007;127:590–1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]