Abstract

Background

Recent studies report the safety and feasibility of performing delayed anastomosis (DA) in patients undergoing damage control laparotomy (DCL) for destructive colon injuries (DCI). Despite accumulating experience in both civilian and military trauma, questions regarding how to best identify high risk patients and minimize the number of anastomosis-associated complications remain. Our current practice is to perform a definitive closure of the colon during DCL, unless there is persistent acidosis, bowel wall edema, or evidence of intra-abdominal abscess. In this study, we evaluated the safety of this approach by comparing outcomes of patients with DCI who underwent definitive closure of the colon during DCL versus patients managed with colostomy with or without DCL.

Methods

We performed a retrospective chart review of patients with penetrating DCI during 2003–2009. Severity of injury, surgical management, and clinical outcome were assessed.

Results

Sixty patients with severe gunshot wounds (GSW) and 3 patients with stab wounds were included in the analysis. DCL was required in 30 patients, all with GSW. Three patients died within the first 48 hours, 3 underwent colostomy, and 24 were managed with DA. Thirty-three patients were managed with standard laparotomy: 26 patients with primary anastomosis, and 7 with colostomy. Overall mortality rate was 9.5%. Three late deaths occurred in the DCL group, and only one death was associated with an anastomotic leak.

Conclusions

Performing a DA in DCI during DCL is a reliable and feasible approach as long as severe acidosis, bowel wall edema, and/or persistent intra-abdominal infections are not present.

Keywords: delayed anastomosis, damage control laparotomy, destructive colon injuries

Introduction

Primary repair of penetrating colon injuries is considered a safe procedure in the majority of patients, and in some cases, even safer and less morbid than a colostomy. To date, strong evidence supports the use of primary repair in patients sustaining this type of injury. A meta-analysis carried out by Nelson and Singer and published in the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews summarizes a comparison of the outcomes of primary repair with those of fecal diversion.1 This study, which included five randomized controlled trials and more than 700 patients, significantly favored primary repair as the treatment of choice for penetrating colon injuries, as it was associated with a significant reduction in morbidity, a similar mortality rate, and a decrease in procedure-related costs.

More recently, however, with the wide spread use of DCL in the treatment of patients with destructive colon injury (DCI), defined as a lesion that involves destruction or ischemia of more than 50% of the colon’s circumference and therefore requires resection of the affected colon segment, the surgeon often contemplates whether to perform DA or perform a diverting colostomy. In this instance, once the patient has been stabilized and the risk of developing hypothermia, acidosis, or coagulopathy has been controlled, during a subsequent relaparotomy, usually after approximately 48–72 hours, the decision of whether to perform a delayed anastomosis or a colostomy can be made. Both approaches are supported by the scientific literature. For example, war-related publications favor performing a colostomy but reports on civilian trauma support performing a delayed anastomosis.2–7 Unfortunately, at present there are no standardized guidelines to aid the surgeon in this decision-making process. The aim of this study was to assess the safety of performing a delayed anastomosis during DCL in patients with DCI.

Materials and Methods

Study design

We conducted a retrospective review of data obtained from the institutional prospective registry (DAMACON2) supplemented with information from medical charts, of patients who underwent DCL or standard laparotomy for DCI due to penetrating abdominal trauma between January 2003 and December 2009. The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee on Biomedical Research of the Fundación Valle del Lili (Cali, Colombia).

Selection criteria

Adults cases were included if the patients had been admitted to the Department of Surgery and Critical Care due to DCI secondary to penetrating abdominal trauma and underwent DCL with delayed anastomosis or standard laparotomy with either primary repair or colostomy.

Patient Data

Variables recorded in the appropriate case report forms included demographic data, severity scoring systems (namely, the Revised Trauma Score [RTS], Injury Severity Score [ISS], Abdominal Trauma Index [ATI], and Acute Physiology and Chronic Health II [APACHE II]), type of surgical procedure, surgical outcome, surgical complications (such as suture line leak, abdominal wall fasciitis, and intra-abdominal abscesses), number of laparotomies, time to anastomosis, assessment and monitoring of metabolic acidosis, estimated blood loss, transfusion of blood or blood products, wound packing, and length of Intensive Care Unit (ICU) and hospital stay. Finally, overall mortality and colon-related mortality were estimated.

Surgical management protocol

In our institution a protocol of damage control for trauma patients has been established. At the time of the index or initial laparotomy, DCL involving control of bleeding with packing is performed if the patients presents with hypothermia (defined as temperature <35 grades Celsius), base deficit > −8 mmol/L, hemoperitoneum greater than 1,500 cubic centimeters, and NISS >35.

The patients underwent immediate DCL, which involved control of bleeding with packing. To prevent contamination, the affected colon segment was resected and the proximal and distal colonic ends were temporarily left in discontinuity. The abdominal wall was closed using the vacuum-pack technique. Patients were transferred to the ICU for mechanical ventilation and hemodynamic monitoring. Planned relaparotomies were performed until control of postoperative bleeding and contamination had been achieved. Once the ‘triad of death’ (i.e. acidosis, hypothermia, and coagulopathy) had been controlled, intra-abdominal packing was removed, definitive repair of vascular injuries was performed, and delayed colonic anastomosis was carried out. For delayed anastomoses, either a side-to-side closure using a GIA-80 linear stapler or a continuous single-layer Vicryl® 3/0 suture was used; preferably during the first or second relaparotomy (within 48 to 72 hours of the index abdominal surgery).

If the patient showed persistent metabolic acidosis, intra-abdominal infections that could not be effectively treated in subsequent relaparotomies, or a severe bowel wall edema that prevented the anastomosis from being performed during the first or second relaparotomy, a colostomy was carried out. Definitive closure of the abdominal wall was performed once the risk of contamination and infection had been controlled, and once bowel wall edema had receded. In cases where a definitive closure of the fascia could not be performed, the skin was closed with an interrupted Prolene® 2/0 suture.

In patients with penetrating wounds and DCI who underwent standard laparotomy with closure of the fascia during the index laparotomy, resection of the affected segment of the colon and primary anastomosis was performed using the technique described above. In patients with rectosigmoid lesions, a colostomy was performed without a priori attempt of primary repair or delayed anastomosis. All patients were followed until hospital discharge.

Statistical analysis

Data were collected in a web-based platform (MySQL, Hughes Technologies, Australia), exported to a binary format, and later imported into STATA® 8 Software (StataCorp. 2003. Stata Statistical Software: Release 8. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP). Continuous variables are expressed as mean, median, and (±) standard deviation, and were compared using Student’s t test or Mann-Whitney U-test, as appropriate. Qualitative variables are expressed as percentages and were compared using chi-square.

Results

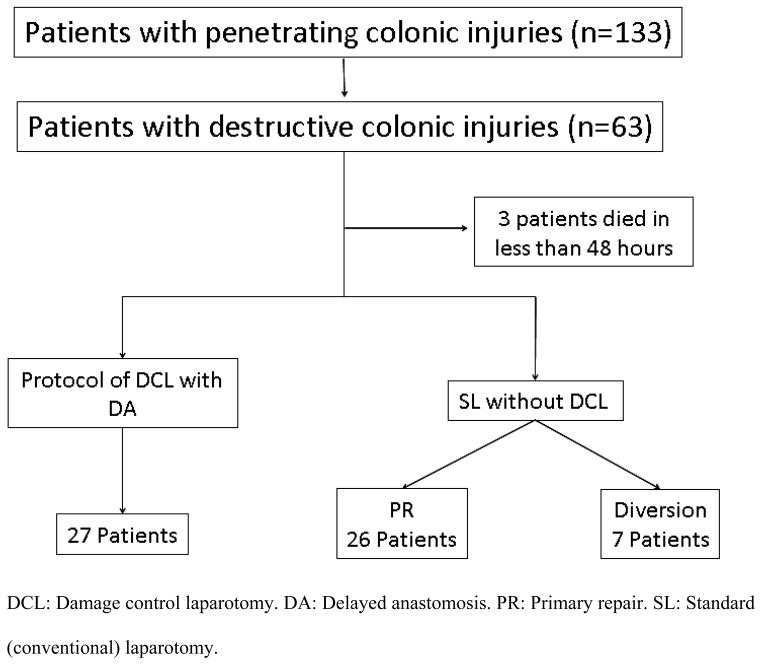

During a seven-year period, 133 patients with penetrating abdominal trauma were admitted to the hospital. Of these patients, 63 with DCI were included in the study. Of the 63 patients, three were excluded from data analysis because they died within 48 hours of the trauma. Overall, 60 patients who required colonic resection due to DCI were included in the analysis. Of them, 57 had sustained gunshot wounds and three had sustained stab wounds. Twenty-seven patients were treated with DCL and 33 were treated with standard (conventional) laparatomy (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Enrollment and allocation of study patients.

Baseline patient characteristics

Mean age was 31.4 ± 11.3 years, and 90% were men. Patients with the greatest systemic involvement and more severe injuries, as shown by data from severity scoring systems, physiological parameters during the first 24 hours, and need for blood products and amount of blood lost during the index laparotomy, underwent DCL. Bowel anastomosis using autosuture staples was performed in 77% of patients in the DCL group and 68% of patients in the standard laparotomy group. Delayed anastomoses were performed after a mean of 67 hours in the group undergoing DCL. The median number of relaparotomies per patient until the definitive closure of the abdominal wall was 4 in patients undergoing DCL, and 1 in patients undergoing standard laparotomy. ICU and hospital stays were significantly longer in patients who underwent DCL compared to patients who underwent conventional laparotomy with primary repair (Table 1).

Table 1.

Comparison of baseline characteristics between patients with destructive colon injuries (DCI) who underwent a damage control laparotomy with delayed anastomosis and patients with DCI who underwent standard laparotomy with primary repair.

| Characteristic | DCL with DA (n=27) | SL with PR (n=26) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD) | 30.0 (12.1) | 31.6 (9.2) | 0.246 |

| Sex, n (%) | |||

| Male | 27 (100.0) | 22 (84.6) | 0.034* |

| Female | 0 (0.0) | 4 (15.4) | |

| Mechanism of injury, n (%) | |||

| Gunshot wounds | 26 (96.3) | 25 (96.1) | 0.971 |

| Stab wounds | 1 (3.7) | 1 (3.8) | |

| Severity scores, mean (SD) | |||

| RTS | 6.3 (2.0) | 7.4 (1.9) | 0.014* |

| ISS | 25.9 (6.1) | 21.8 (7.1) | 0.038* |

| APACHE II | 20.7 (6.8) | 10.7 (6.4) | <0.001* |

| ATI | 41.2 (20.3) | 28.0 (10.2) | 0.013* |

| Physiologic parameters, mean (SD) | |||

| pH | 7.24 (0.08) | 7.28 (0.87) | 0.055 |

| Lactate | 4.7 (2.2) | 2.5 (1.51) | 0.038* |

| Base deficit | −9.4 (4.3) | −8.8 (3.4) | 0.484 |

| Transfusions, mean (SD) | |||

| RBC | 4.7 (3.5) | 1.0 (2.0) | <0.001* |

| Blood loss in surgery, mean, ml (SD) | 3,878.2 (2,484.9) | 1,100.0 (557.2) | <0.001* |

| Surgical parameters | |||

| Relaparotomies, median | 4 (3–5) | 1 (2–3) | 0.005* |

| Anastomosis (stapled), n (%) | 21 (77.3) | 18 (69.2) | 0.447 |

| Time to anastomosis (hrs), mean (SD) | 67 (12.2) | Index laparotomy | - |

| Length of stay, mean (SD) | |||

| ICU | 19.6 (15.9) | 4.2 (4.5) | <0.001* |

| Hospital | 47.7 (71.7) | 17.7 (18.9) | 0.003* |

Statistically significant (p<0.05).

ATI: Abdominal Trauma Index. APACHE: Acute Physiology and Chronic Health II. SL: Standard laparotomy. DA: Delayed anastomosis. DCL: Damage control laparotomy. ICU: Intensive Care Unit. ISS: Injury Severity Score. PR: Primary repair. RBC: Red blood cells. RTS: Revised Trauma Score. SD: Standard deviation.

Index surgery

Twenty-five of the 27 patients (92.6%) underwent DCL with packing to control bleeding. In addition to surgical repair of major vascular injuries, liver and retroperitoneal packing was performed in 50% and 70% of patients, respectively. To control the risk of contamination, the destructive injuries were resected and the bowel was left in discontinuity. This was performed in all patients undergoing DCL during the initial surgery.

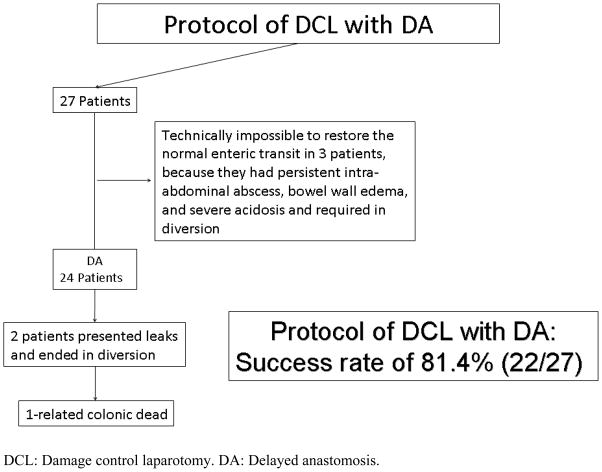

No primary anastomoses were carried out during the index laparotomy. Of the 27 patients in whom DCL was performed, 24 (88.8%) underwent delayed anastomosis, and three (11.1%) required a colostomy due to impossibility to perform an anastomosis because they had persistent intra-abdominal infections with severe colonic wall edema and inflammation, and acidosis. DCL with delayed anastomosis was ultimately performed in 22 out of 27 (81.4%) patients (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Treatment protocol in patients who underwent DCL with delayed anastomosis.

A median of 4 relaparotomies (range: 3–4) per patient were performed every 24–48 hours until definitive repairs were made to control bleeding, carry out abdominal cavity lavage to prevent contamination and infection, perform delayed anastomoses, control bowel and abdominal wall edema, and close the abdominal wall.

Delayed anastomoses were performed after a mean of 67 ± 12.2 hours (range: 48–72), corresponding either to the first (60.8% of procedures) or second (39.1% of procedures) relaparotomies. Of the procedures, 9 (37.5%) were colo-colonic and 15 (62.5%) were ileo-colonic anastomoses. In 77% of cases, the technique employed was the side-to-side closure with a GIA-80 linear stapler or with a hand-sewn single-layer continuous Vicryl® 3/0 suture if the stapler was not available or it was technically difficult to use. In all patients who underwent DCL, the open abdominal wound was temporarily closed using the vacuum-pack technique. Definitive and complete closure of the fascia was performed in 12 (45%) patients, and skin closure alone was performed in another 12 (45%) patients.

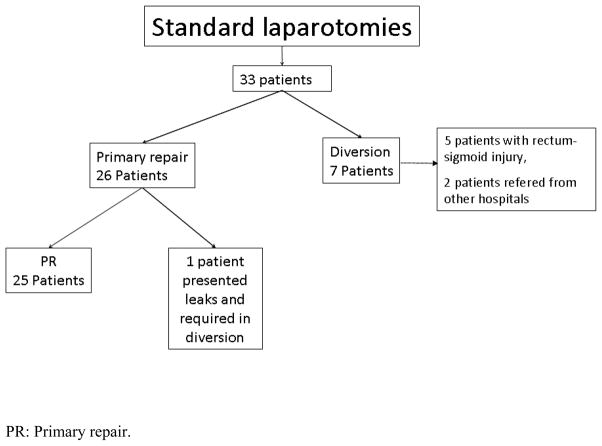

Standard laparotomy was performed in 33 patients with DCI. Of those, 24 patients underwent primary anastomosis during the index laparotomy, of which 12 (50%) were colocolonic and 12 (50%) were ileocolonic anastomosis. A colostomy was performed in seven out of 33 patients, due to a destructive injury of the rectosigmoid in five patients and prior colostomy performed at an outside hospital before arriving to our trauma center in two patients (Tables 1 and 2, Figure 3).

Table 2.

Comparison of baseline characteristics between patients with destructive colon injuries (DCI) who underwent a damage control laparotomy with delayed anastomosis and patients with DCI who underwent standard laparotomy with colostomy.

| Characteristic | DCL with DA (n=27) | SL with colostomy (n=7) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD) | 30.0 (12.1) | 36.3 (15.7) | 0.276 |

| Sex, n (%) | |||

| Male | 27 (100.0) | 6 (85.7) | 0.046* |

| Female | 0 (0.0) | 1 (14.3) | |

| Mechanism of injury, n (%) | |||

| Gunshot wounds | 26 (96.3) | 6 (85.7) | 0.280 |

| Stab wounds | 1 (3.7) | 1 (14.3) | |

| Severity scores, mean (SD) | |||

| RTS | 6.3 (2.0) | 6.3 (1.6) | 0.920 |

| ISS | 25.9 (6.1) | 18.8 (8.1) | 0.024* |

| APACHE II | 20.7 (6.8) | 9.0 (6.6) | 0.003* |

| ATI | 41.2 (20.3) | 29.3 (16.2) | 0.130 |

| Physiologic parameters, mean (SD) | |||

| pH | 7.24 (0.08) | 7.30 (0.09) | 0.336 |

| Lactate | 4.7 (2.2) | 2.9 (1.8) | 0.155 |

| Base deficit | −9.4 (4.3) | −8.3 (5.1) | 0.490 |

| Transfusions, mean (SD) | |||

| RBC | 4.7 (3.5) | 1.8 (1.7) | 0.080 |

| Blood loss in surgery, ml, mean (SD) | 3,878.2 (2,484.9) | 2,140 (630.8) | <0.001* |

| Surgical parameters | |||

| Relaparotomies, median | 4 (3–5) | 2 (3–5) | 0.03* |

| Length of stay, mean (SD) | |||

| ICU | 19.6 (15.9) | 8.4 (8.9) | <0.001* |

| Hospital | 47.7 (71.7) | 19.1 (13.6) | 0.003* |

Statistically significant (p<0.05).

ATI: Abdominal Trauma Index. APACHE: Acute Physiology and Chronic Health II. SL: Standard laparotomy. DA: Delayed anastomosis. DCL: Damage control laparotomy. ICU: Intensive Care Unit. ISS: Injury Severity Score. RBC: Red blood cells. RTS: Revised Trauma Score. SD: Standard deviation.

Figure 3.

Treatment protocol in patients undergoing standard laparotomy.

Complications

Two (7.7%) patients developed anastomotic leaks; one patient developed anastomotic leak in the right colon and the other patient developed the anastomotic leak in the left colon. The splenic flexure was not compromised in these patients. In addition, these two patients developed pancreatic complications, consisting of a pancreatic abscess in one patient, and a severe post-traumatic pancreatitis in the other.

Sixteen (54.2%) patients developed intra-abdominal abscesses associated with a positive culture and inflammatory response. These patients required a relaparotomy to control the infection. Three (12.5%) patients developed fasciitis of the abdominal that required debridement and antibiotic therapy. The three patients in whom a colostomy was performed developed persistent intra-abdominal abscesses with severe colonic wall edema and inflammation, and acidosis (Tables 3 and 4).

Table 3.

Comparison of outcomes between patients with destructive colon injuries (DCI) who underwent a damage control laparotomy with delayed anastomosis and patients with DCI who underwent standard laparotomy with primary repair.

| Outcome | DCL with DA (n=27) | SL with primary repair (n=26) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Complications, n (%) | |||

| Leaks | 2 (7.4) | 1 (3.8) | 0.157 |

| Intra-abdominal abscess | 16 (59.2) | 12 (46.2) | 0.34 |

| Fasciitis | 3 (11.1) | 3 (11.5) | 0.96 |

| Mortality, n (%) | 1 (3.7) | 0 (0.0) | 0.322 |

SL: Standard laparotomy. DA: Delayed anastomosis. DCL: Damage control laparotomy.

Table 4.

Comparison of outcomes between patients with destructive colon injuries (DCI) who underwent damage control laparotomy with delayed anastomosis and patients with DCI who underwent standard laparotomy with colostomy.

| Outcome | Protocol of DCL with DA (n=27) | SL with colostomy (n=7) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Complications, n (%) | |||

| Leaks | 2 (7.4) | 0 (0.0) | 0.458 |

| Intra-abdominal Abscess | 16 (59.2) | 3 (42.8) | 0.436 |

| Fasciitis | 3 (11.1) | 1 (14.3) | 0.816 |

| Mortality, n (%) | 1 (3.7) | 0 (0.0) | 0.605 |

SL: Standard laparotomy. DA: Delayed anastomosis. DCL: Damage control laparotomy.

In the group of patients who underwent standard laparotomy, one (3.8%) patient developed an anastomotic leak that required a colostomy. Twelve (46.2%) patients developed intra-abdominal abscesses, and three (11.5%) developed fasciitis of the abdominal wall. Three of the seven patients (42.8%) who underwent standard laparotomy with colostomy developed intra-abdominal abscesses, and one (33.3%) developed a fasciitis of the abdominal wall (Tables 3 and 4).

Mortality

Overall mortality was 9.5% (6 out of 63 patients). Three patients died within 48 hours of the trauma as a consequence of coagulopathy. These three patients were excluded from statistical analyses. Three late deaths occurred in the group of patients who underwent DCL, two of them unrelated to the colon injury, and one colon-related death secondary to a severe post-traumatic pancreatitis, followed by delayed anastomotic leakage with multiple intra-abdominal abscesses, erosion of the aorta, and massive bleeding.

Discussion

The results of this study demonstrate that performing a delayed anastomosis during DCL in patients with DCI requiring resection is a feasible approach, without the occurrence of more complications than those observed with conventional laparotomy and primary anastomosis and/or standard colostomy. The success rate obtained in the DCL plus DA group was 81.5%.

Over the last 60 years, clinical practice in the treatment of most civilian DCIs shifted from mandatory colostomy to primary anastomosis during standard laparotomy.8, 9 However, in the setting of extensive damage associated with vascular and visceral involvement, the surgical outcome depends on the trauma surgeon’s prompt decision to implement damage control strategies. Control of hemorrhage is achieved either with packing of the bleeding site or involved organ, or using common vascular repair techniques such as ligations, temporary diversions, and balloon tamponade catheters.10–12

Hollow-organ injury following penetrating trauma is temporarily managed with suture ligation, staples, or simple suturing of the proximal and distal ends of the organ, whereas anastomoses, reconstructions, and ostomies are deferred. The procedure is considered complete once bleeding and contamination have been controlled. Definitive repairs and reconstructions are performed later during a planned staged surgery.3–5

However, little information is available on colonic reconstruction with delayed anastomosis, and a significant amount of controversy about the use of this procedure persists. In the case of war-related injuries, the literature reports colostomy as the safest option.2, 6, 7

Small bowel or colonic perforations are repaired using a continuous single-layer suture. If the bowel requires resection and anastomosis, it must not be performed at that point. Instead, a temporary procedure involving resection of the affected segment, followed by ligation of the proximal and distal ends must be done thus leaving the bowel in discontinuity. This approach facilitates control of leakage of intestinal contents without prolonging surgical times or adding physiological stress. Furthermore, the use of this technique avoids the need for a formal resection and reconstruction with end-to end anastomosis, which requires even longer surgical times. In addition, the integrity of the anastomosis is threatened by the tissue hypoperfusion and hemodynamic instability is typically seen in these patients sustaining DCI. Even though management of the colon by means of a colostomy can be a relatively quick procedure, it is not considered a good option because during reanimation, the already edematous abdominal wall can swell even more, and the intestinal loop that was used to create the stoma might become necrotic due to lack of blood supply. In addition, it could substantially prolong surgical time. Ligating or stapling the colon is a much more viable, practical, and uncomplicated solution than performing any type of ostomy or anastomosis.3–5

Recent literature reports a small series of patients on whom DA was performed in the setting of DCI. In 2001, Johnson et al.3 successfully performed delayed anastomosis in seven patients after damage control surgery. In 2007, Miller et al.5 published research on the first series of patients to undergo colonic resection and delayed anastomosis after the index DCL. Kashuk et al.4 report that primary repair of colon injuries after DCL appears to be a safe procedure in most patients, and that an open abdomen allows time to decide whether to perform a colostomy or not at a later procedure. Burlew et al.13 recently reported a multi-institutional experience on 204 patients. In this series they had a total of 96 patients undergoing delayed anastomisis. They found that the majority of patients with leaks had a delayed anastomosis. The leak rate increased with fascial closure beyond day 5 and with left-sided colonic anastomoses.

According to Weinberg et al.,7 colon injuries in the setting of DCL are associated with a high complication rate and increased incidence of leakage. Cho et al.2 suggest that colostomy is a safer alternative for the treatment of war-related colon injuries in the setting of damage control. Vertress et al.6 conclude that a delayed anastomosis during damage control surgery is feasible once the patient stabilizes.

We believe that a delayed anastomosis should be performed in all patients with DCI undergoing DCL, but is not recommended in patients with recurrent intra-abdominal abscesses, severe bowel wall edema and inflammation, or persistent metabolic acidosis. In these patients, a colostomy should be performed.

Complications and mortality

Anastomotic leak is a serious and challenging complication. In our study, this complication occurred in two patients in the DCL group, and in one patient in the standard laparotomy group. The splenic flexure was not compromised in these patients and therefore we were not able to associate the occurrence of injuries in the splenic flexure with anastomotic leaks, as it has been described by other authors.14 Of note, the two patients in the DCL group who developed anastomotic leaks had concomitant pancreatic injury and developed complications secondary to this lesion; one patient developed a pancreatic abscess and the other a severe post-traumatic pancreatitis.

Intra-abdominal abscesses occurred in a large number of patients, with a similar distribution in all three groups. This complication developed as a consequence of the initial trauma and contamination, and not from the surgical technique used in the delayed anastomosis, primary anastomosis, or colostomy. Moreover, abscesses did not have an effect on mortality, as the infection was effectively controlled with peritoneal cavity lavage and open abdomen in subsequent relaparotomies in the group of DCL patients,15 and with relaparotomy on demand, or computer tomography-guided puncture in the group of standard laparotomy patients. Fasciitis of the abdominal wall occurred in a similar number of patients in the three treatment groups, and was controlled with thorough debridement and antibiotic therapy.

Two late deaths secondary to sepsis and multisystem organ failure (not related to the colon injury) occurred in the DCL group. One colon-related death occurred in the DCL group. The patient developed a severe post-traumatic pancreatitis followed by a delayed anastomotic leakage with multiple intra-abdominal abscesses, which eroded the aorta and produced massive bleeding, ultimately leading to his death. Although no colon-related deaths were documented in the group of patients who underwent standard laparotomy, no significant differences were observed among treatment groups.

Study limitations

The current practice regarding surgical treatment of patients with DCI is conditioned by the surgeons’ preferences and expertise. Bias selection resulting from the fact that the patients’ management was based on individual surgeon opinion cannot be completely ruled out. Because of the retrospective nature of this review, differences in management could not be determined. Also, it is possible that other differences might have occurred in addition to that of the surgical procedure.

Patients who underwent DCL were significantly more severely injured than patients who underwent SL. In addition, patients in the DCL group lost more blood during surgery and required more packed red blood cells and more days of hospitalization than patients in the SL groups. Therefore, the internal validity of this study relied on the fact that patients in the damage control group were seemingly sicker as defined by some of the initial severity scores, physiologic parameters, needs of transfusions, surgical parameters, and days of hospitalization than patients in the standard laparotomy group. Despite that, the complication and mortality rates were not significantly different.

Generalizability might be a concern in this study. Characteristics of our population may vary the incidence of the disease, mortality, and morbidity outcomes that we have evaluated. Applicability of the DCL with delayed anastomosis in our critically ill patients with destructive colon injuries might be valid and feasible. Nevertheless, reproducibility and validation of this data will be required in patients from other populations.

Conclusions

Delayed anastomosis during DCL in patients with DCI is a reliable and feasible technique, yielding a success rate of 81.4%, which could be considered as an option in patients with DCI, except in those presenting with recurrent intra-abdominal abscesses, severe bowel wall edema and inflammation, or persistent metabolic acidosis.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Ximena Alvira and Christine Heiner for their editorial assistance.

Funding:

This study was funded in part by the Fogarty International Center (NIH Grant D43 TW007560) and by the Fundación Valle del Lili, Cali, Colombia.

Footnotes

Meetings:

The results of this manuscirpt were presented as a podium paper at the 69th AAST annual meeting in Boston, MA, September 22–25, 2010.

Contributor Information

Carlos A Ordoñez, Email: ordonezcarlosa@gmail.com.

Luis F Pino, Email: ferpmd@gmail.com.

Marisol Badiel, Email: marisolbadiel@yahoo.com.mx.

Alvaro I Sánchez, Email: sanchezortiza@upmc.edu.

Jhon Loaiza, Email: jhonha1102@gmail.com.

Leonardo Ballestas, Email: leoballestas@yahoo.com.

Juan Carlos Puyana, Email: puyanajc@upmc.edu.

References

- 1.Nelson R, Singer M. Primary repair for penetrating colon injuries. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2003;(3):CD002247. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cho SD, Kiraly LN, Flaherty SF, Herzig DO, Lu KC, Schreiber MA. Management of colonic injuries in the combat theater. Dis Colon Rectum. 2010 May;53(5):728–734. doi: 10.1007/DCR.0b013e3181d326fd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Johnson JW, Gracias VH, Schwab CW, et al. Evolution in damage control for exsanguinating penetrating abdominal injury. J Trauma. 2001 Aug;51(2):261–269. doi: 10.1097/00005373-200108000-00007. discussion 269–271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kashuk JL, Cothren CC, Moore EE, Johnson JL, Biffl WL, Barnett CC. Primary repair of civilian colon injuries is safe in the damage control scenario. Surgery. 2009 Oct;146(4):663–668. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2009.06.042. discussion 668–670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Miller PR, Chang MC, Hoth JJ, Holmes JHt, Meredith JW. Colonic resection in the setting of damage control laparotomy: is delayed anastomosis safe? Am Surg. 2007 Jun;73(6):606–609. doi: 10.1177/000313480707300613. discussion 609–610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vertrees A, Wakefield M, Pickett C, et al. Outcomes of primary repair and primary anastomosis in war-related colon injuries. J Trauma. 2009 May;66(5):1286–1291. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e31819ea3fc. discussion 1291-1283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Weinberg JA, Griffin RL, Vandromme MJ, et al. Management of colon wounds in the setting of damage control laparotomy: a cautionary tale. J Trauma. 2009 Nov;67(5):929–935. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e3181991ab0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Demetriades D. Colon injuries: new perspectives. Injury. 2004 Mar;35(3):217–222. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2003.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Demetriades D, Murray JA, Chan L, et al. Penetrating colon injuries requiring resection: diversion or primary anastomosis? An AAST prospective multicenter study. J Trauma. 2001 May;50(5):765–775. doi: 10.1097/00005373-200105000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hirshberg A, Mattox KL, editors. Top Knife: The Art and Craft in Trauma Surgery. TFM Publishing Ltd; 2005. Section I. Tools of the Trade; pp. 3–5. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hirshberg A, Mattox KL, editors. Top Knife: The Art and Craft in Trauma Surgery. TFM Publishing Ltd; 2005. Chapter 1. The 3-D Trauma Surgeon; pp. 5–19. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rotondo MF, Schwab CW, McGonigal MD, et al. ‘Damage control’: an approach for improved survival in exsanguinating penetrating abdominal injury. J Trauma. 1993 Sep;35(3):375–382. discussion 382-373. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Burlew CC, Moore EE, Cuschieri J, et al. Sew it up! A Western Trauma Association multi-institutional study of enteric injury management in the postinjury open abdomen. J Trauma. 2011 Feb;70(2):273–277. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e3182050eb7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dente CJ, Patel A, Feliciano DV, et al. Suture line failure in intra-abdominal colonic trauma: is there an effect of segmental variations in blood supply on outcome? J Trauma. 2005 Aug;59(2):359–366. doi: 10.1097/01.ta.0000185034.64059.96. discussion 366-358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ordonez CA, Sanchez AI, Pineda JA, et al. Deferred primary anastomosis versus diversion in patients with severe secondary peritonitis managed with staged laparotomies. World J Surg. 2010 Jan;34(1):169–176. doi: 10.1007/s00268-009-0285-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]